Abstract

Objective

Blue-collar workers are difficult to reach and less likely to successfully quit smoking. The objective of this study was to test a training site-based smoking cessation intervention.

Methods

This study is a randomized-controlled trial of a smoking cessation intervention that integrated occupational health concerns and was delivered in collaboration with unions to apprentices at 10 sites (n = 1,213). We evaluated smoking cessation at 1 and 6 months post-intervention.

Results

The baseline prevalence of smoking was 41%. We observed significantly higher quit rates in the intervention versus control group (26% vs. 16.8%; p = 0.014) 1 month after the intervention. However, the effects diminished over time so that the difference in quit rate was not significant at 6 month post-intervention (9% vs. 7.2%; p = 0.48). Intervention group members nevertheless reported a significant decrease in smoking intensity (OR = 3.13; 95% CI: 1.55–6.31) at 6 months post-intervention, compared to controls.

Conclusion

The study demonstrates the feasibility of delivering an intervention through union apprentice programs. Furthermore, the notably better 1-month quit rate results among intervention members and the greater decrease in smoking intensity among intervention members who continued to smoke underscore the need to develop strategies to help reduce relapse among blue-collar workers who quit smoking.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Despite the well-documented harmful effects of cigarette smoking [1, 2], an estimated 20%, 31%, and 35% of white-collar, service, and blue-collar workers, respectively, still smoke cigarettes, compared to a prevalence of 20% in the general population [3, 4]. Blue-collar workers have the highest prevalence of smoking compared to other workers; a disparity that has persisted since 1956 and continues to widen with time [3, 5–10]. One of the chief sources of this widening disparity is the higher rate of smoking cessation by white-collar workers compared to other workers [10, 11]. Whereas there are no disparities in attempts at quitting smoking by occupational class, disparities exist in success with smoking cessation with white-collar workers being more successful than blue-collar workers [3, 6, 9, 10].

The need to address these disparities is imperative given that blue-collar workers are also more likely to be exposed to work-related carcinogens [12–15] and other substances, such as dusts and fumes, which can compound the hazards of cigarette smoking. In addition, they are more likely to report that they started smoking at an earlier age and that they smoke more cigarettes daily compared to other workers [6, 16]. Additionally, they are usually underrepresented in worksite interventions and are less likely to report behavior change after worksite-based health promotion interventions [17, 18].

Given the limited success of smoking cessation interventions targeting blue-collar workers [19–21], redressing disparities in smoking behavior and cessation by occupational class require exploration into the unique needs of blue-collar workers. Worksites have been cited as an effective medium through which smoking cessation interventions can be delivered to blue-collar workers [19, 22]. However, the nature of most blue-collar work, especially construction work, is that workers are scattered in short-term assignments across a range of construction employers; thus, making it difficult to reach them through worksite health promotion. Union apprenticeship programs can serve as a vehicle for the delivery of interventions. Apprentice training programs are typically located in union halls, entail 3–4 years of classroom-based and on-the-job training, and are jointly funded by labor and management [23]. The programs have the unique feature of structured classes that provide access to large groups of apprentices and have a curriculum that devotes class time to health and safety issues. The unions have physical space and communication infrastructures (e.g., member lists, newsletter), which facilitate the dissemination of intervention components.

The social contextual framework advocates addressing occupational safety and health conditions as mediators in smoking cessation interventions designed for blue-collar workers [24]. Using this framework, the Wellworks 2 study by Sorensen et al. demonstrated a doubling of smoking cessation among blue-collar workers in manufacturing worksites that were randomly assigned to an intervention that entailed health promotion plus occupational health protection, compared to blue-collar workers that received a health promotion-only intervention [25].

In this study, we present findings on the effectiveness of a smoking cessation intervention for building trade apprentices in Massachusetts, tested in a group randomized study. The design and implementation of the study was conducted in collaboration with the Massachusetts Building Trades Council; which is a collection of unions, each of which runs apprenticeship training programs for individuals wishing to become unionized boilermakers, bricklayers, electricians, hoisting and portable engineers, ironworkers, painters, plumbers, pipefitters, sprinklerfitters, or refrigeration workers.

Methods

Study design

Study population

With the support of the president of the Massachusetts Building Trades Council, the study team introduced the study at a meeting for the 28 training program directors. Later, we mailed each director a recruitment packet that explained the study and its requirements, and made follow-up phone calls to assess willingness to participate, then scheduled an in-person meeting as appropriate.

To be eligible for the study, training programs had to: (1) be located within 1 h of the study base (DFCI), (2) enroll a minimum of 40 apprentices, (3) agree to random assignment as to start date of intervention, (4) allow for survey administration to take place during class time in the union hall, and (5) allow for each of the intervention components to take place at the union hall. Of the 20 programs that initially met eligibility criteria, 10 refused to participate because they could not accommodate the length of the intervention (n = 6) or had an existing smoking cessation program (n = 4). Ten eligible sites agreed to be part of the study and were size matched and randomly assigned to four intervention sites (n = 1,044 trainees) and six control sites (n = 897 trainees). All apprentices at the intervention sites were eligible to participate in the study.

Data collection

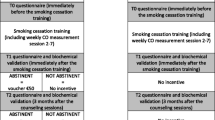

The Dana-Farber Cancer Institute institutional review board approved all the methods and materials used in the study. We obtained survey data at all sites through written questionnaires that we administered at baseline (time 1), followed by a 4-month intervention period in the intervention sites. Follow-up surveys were administered 1 month (time 2) and at least 6 months (time 3) after the intervention. All surveys were administered during regularly scheduled meetings or class times at the union halls. At each study period, study staff surveyed all apprentices who were present. Questionnaires were left with apprenticeship program coordinators who then handed or mailed these questionnaires (with stamped return envelope) to apprentices who were absent at survey times.

At baseline (time 1), 1,817 apprentices (93.6% response rate) filled out the study questionnaire. After the intervention, we were able to match 1,502 apprentices (82.6% response rate) at time 2 and 1,362 apprentices (80.7% response rate) at time 3 to baseline surveys. The sample for the present analyses is restricted to the embedded cohort of 1,213 apprentices for whom we had survey data for all three time points of the study. Data collection at time 3 occurred at least 6 months and up to 9 months after the intervention due to the rigidity of the training schedules for the apprentices which prevented data collection at scheduled times. Two intervention sites had data collection at 8 and 9 months after the intervention.

Intervention study conditions

Intervention condition

The apprentices in the intervention sites received a multi-pronged intervention, which followed the social contextual framework by integrating occupational concerns into intervention activities. The intervention was based on the US Public Health Service treatment guidelines for tobacco use and dependence [26]. Also, we drew from materials and approaches of Building Trades United to Ignite Less Tobacco (BUILT)—a project of the Labor Occupational Health Program at the University of California, Berkeley and the state building and construction trades council of California [27].

The intervention components were also pilot-tested to confirm their feasibility and to establish estimates for likely effect sizes [28]. Qualitative research conducted as part of the pilot study indicated that apprentices were well aware of the harmful health effects of smoking, and uninterested in hearing this generic message. In contrast, as apprentices learning their new trades, they expressed great interest in new and more personally relevant information, such as how the new substances and processes they were learning would affect their health, especially if they continued to smoke. Guided by the social contextual framework, a key goal of the intervention curriculum was to increase the apprentices’ awareness of the potential additive and synergistic effects of exposure to job-related hazards combined with smoking. In essence, the apprenticeship period constituted a new ‘teachable’ moment for smoking cessation.

The multi-pronged intervention was conducted over 4 months and consisted of the following components.

Toxics and tobacco curriculum We supplemented the curriculum of the apprenticeship programs to include two 1-h modules that focused on job hazards encountered in the building trades, stressing the potential additive and synergistic effects of these exposures, and cigarette smoking. During a class session, the apprentices were shown a video, made by the California BUILT project, which reinforced these messages and used humor and sarcasm that resonated with the occupational culture of building trades workers. And, study staff let the apprentices know that the team would be offering smoking cessation ‘classes,’ i.e., group-based behavioral counseling, at their union halls in the coming weeks.

Group-based behavioral counseling State certified tobacco treatment specialists trained in motivational interviewing techniques led 8-weekly group counseling sessions at each intervention site. Groups ranged in size from 3 to 12 participants. Topics covered included pros and cons of tobacco use and quitting, potential barriers and triggers, reasons to quit, coping techniques, preparing for withdrawal, proper use of over-the-counter nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) and options for prescription medications to assist with quitting, stress management, and how to stay quit.

Nicotine replacement therapy Smoking cessation counselors made NRT patches (21 mg—Step 1, 14 mg—Step 2 and 7 mg—Step 3) available free of charge to smokers at the intervention sites regardless of their level of participation in the behavioral therapy group sessions as long as they were deemed by one of the project’s smoking cessation counselors to have no contraindications for NRT.

Do it yourself quit kit These kits, which contained smoking cessation guide, were available to all apprentices.

Environmental cues for smoking cessation The study team created and displayed in apprenticeship classrooms and common areas a series of five posters that reinforced key concepts in the Toxics and Tobacco curriculum modules and that included photos and quotes from apprentices who had recently quit smoking about why and how they quit. In addition, written materials, which addressed how co-workers, friends and family members can support quit attempts, were provided to apprentices at intervention sites.

Apprentices who chose to attend the cessation classes were given early release from apprenticeship classes and meals were provided at the sessions. Apprentices who completed at least seven of eight counseling sessions were eligible to participate in a raffle drawing for a cash prize. Also, we provided incentives in the form of $10 store gift cards for completion of surveys.

Control condition

The control sites participated in all surveys but did not receive any intervention components. We delivered the intervention to these sites after we had collected all study data.

Measures

Apprentices who reported smoking at least 100 cigarettes in their lifetimes and smoking in the last 30 days were classified as current smokers at baseline. We collected several measures of smoking cessation as recommended by a Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco workgroup on measures of smoking abstinence [29]. We measured prolonged abstinence from smoking for at least 6 months from the time of data collection at time 3 (primary study outcome). Also, we measured 7-day point prevalence abstinence at 1-month post-intervention (time 2; Question: Have you smoked a cigarette, even a puff, in the last 7 days). We assessed intention to quit in the next 30 days and next 6 months, smoking decisional balance [30], self efficacy [31], smoking intensity (number of cigarettes smoked per day in the last 30 days), smoking frequency (number of days smoked in the last 30 days), and confidence in staying quit (options: have not quit, extremely confident, very confident, somewhat confident, slightly confident, and not confident). Based on answers at times 2 and 3, we created new variables that summarized changes in smoking intensity, smoking frequency, decisional balance and confidence in staying quit as either increase, decrease, or no change.

Apprentices self-reported their race/ethnicity, age, educational attainment, gender, and income in the baseline survey. We collapsed race/ethnicity into Hispanic, Black, White, and Other. Likewise, educational attainment was collapsed from seven categories into four (less than high school, high school or GED, some college or 2 year degree, or 4 years or more). The less than high school and high school or GED categories were further collapsed into one category during data analysis because only four people reported having less than high school education. We also collapsed household income from seven $10,000 increments of income from under $10,000 to $75,000 or more into four categories (<$25,000, $25,000–49,999, $50,000–74,999, and ≥$75,000).

We assessed smoking behaviors via self-report on surveys, and opted not to conduct biochemical verification. Drug testing is routine in the study sites, and union leaders advised us that any biological tests would likely be misinterpreted by workers as a drug test, and would likely lead to deep mistrust of study staff. To ensure accurate reporting of smoking status, survey assistants stressed the importance of truthful reporting of smoking status to the ability of the team to develop effective smoking cessation interventions. They also reminded participants that confidentiality of results would be maintained.

Data analysis

In this study, apprentice sites were the unit of randomization and intervention while individual apprentices were the unit of measurement. Our analysis involved the apprentices who met our baseline criteria for smoking. Using the intention to treat principle, we classified all apprentices in the intervention sites as part of the intervention group regardless of their level of participation and compliance. Due to the potential within-cluster (site) correlation, all multivariate analyses were conducted using SAS GLIMMIX with sites being modeled as random effect terms [32].

Data analysis began with univariate descriptive analyses using chi-square statistics for categorical and t-test for normal continuous variables. For the primary outcome, we first evaluated smoking cessation rates between the intervention and control groups using two-by-two contingency tables. We modeled multivariate odds of smoking cessation at times 2 and 3 comparing the intervention to control group controlling for demographic variables. To assess increase, decrease, or no change in secondary variables, we constructed multivariate multinomial logistic regression models using SAS GLIMMIX controlling for demographic variables. For those who did not report their ages (n = 48), we assigned them the median age at their union site. To account for those missing income (n = 185), race (n = 74), education (n = 62), and gender (n = 29), we used the Amelia II program, a bootstrapping-based algorithm that “multiply imputes” missing data in a cross-sectional or longitudinal setting (freely available from http://gking.harvard.edu/amelia/), to impute data for those missing these variables [33]. We used the MIANALYZE procedure in SAS to combine the results of the multivariate regressions from 10 imputations.

Results

Characteristics of the study sample

The baseline characteristics, prior to imputing missing covariates, of the apprentices who completed all three surveys are presented in Table 1. Randomization was generally effective in creating comparable groups. However, there were statistically significant differences between the control and the intervention sites based on gender, race, and income. The study population was predominantly male; and in one intervention site, our cohort included only men. Similarly, the difference in race by intervention group arose because 50% of the apprentices who were not White, Hispanic, or Black were at one site, which was an intervention site. Apprentices who made less than $25,000 were less likely to be in the intervention group compared to apprentices who made equal to or greater than $75,000. Here again, 45% of those who made equal to or greater than $75,000 came from one intervention site. The control and intervention sites did not have significant baseline differences among apprentices who smoke in smoking prevalence, intention to quit in 30 days and 6 months, smoking intensity, nicotine addiction, smoking decisional balance, and smoking temptation/self efficacy.

Primary outcome

At baseline, 41% of apprentices (n = 490) met our definition of current smoking. Of these, 56.6% reported at baseline that they had stopped smoking for at least 1 day or longer in the last year because they were trying to quit smoking and 45% reported that they were seriously thinking of quitting in the next 30 days. Thirty days after the intervention (time 2), there were significant differences in smoking cessation rates with the intervention group having higher quit rates (26% vs. 16.8%; p = 0.014; Fig. 1). These differences diminished over time so that the difference in quit rates was not statistically significant at 6-month post-intervention (9% vs. 7.2%; p = 0.48). The results remained stable in multivariate analyses that accounted for clustering by worksite and controlled for age, gender, race and education. Apprentices in the intervention sites had 1.62 times higher odds of quitting smoking 30 days after the intervention (OR = 1.62; 95% CI: 1.02–2.59) compared to apprentices in the control sites. The intervention effect diminished 6 months after the intervention (OR = 1.10; 95% CI: 0.58–2.08).

Secondary outcomes

In addition, we evaluated differences in quit attempts that lasted more than 1 day, smoking intensity (amount of cigarettes), smoking decisional balance, and smoking frequency (number of days smoke) between intervention and control group members. Generally, apprentices from the intervention sites reported better secondary smoking cessation outcomes compared to apprentices at control sites at both 30 days and 6 months after the intervention. Six months after the intervention, apprentices in the intervention sites were three times more likely to report a decrease of at least half a pack in the amount of cigarettes they smoke daily (OR = 3.13; 95% CI: 1.55–6.31). In addition, they were also somewhat more likely to report increases in attempted smoking cessation that lasted at least 1 day (OR = 1.31; 95% CI: 0.88–1.96), decisional balance that supports smoking cessation (OR = 1.29; 95% CI: 0.74–2.27), and decrease in number of days they smoke (OR = 1.18; 95% CI: 0.62–2.25); although these differences were not statistically significant.

Discussion

Using a randomized-controlled study design, we found that a smoking cessation intervention for blue-collar apprentices delivered in a unionized apprenticeship setting, and that incorporated messages about the dual risks of smoking and occupational hazards, produced significantly higher quit rates in the intervention versus control conditions 30 days after the intervention. The difference in quit rates was not maintained 6 months later, however, suggesting that many who had quit subsequently relapsed. Additionally, we found that baseline smokers in the intervention group who had not quit smoking 6 months after the intervention were three times more likely to report that they decreased the amount of cigarettes they smoke by at least half a pack. We also observed a high prevalence of smoking among the apprentices in the study compared to the general population (41% vs. 20.2%). This high prevalence of smoking among workers in the building trades has recently been reported by a national study [34].

The rates of smoking cessation reported by the apprentices in the control group is unusually high given that the median unaided prolonged abstinence rates in the general U.S. population is about 5% [35]. However, the prevalence of smoking in this population is almost twice the prevalence in the general population. Also, expressed interest in smoking cessation and attempts is higher in our population than in the general population. Compared to 42.5% in the general population [36], 56.6% of the apprentices reported at baseline that they had stopped smoking for at least 1 day or longer in the last year because they were trying to quit smoking. Likewise, 45% of smokers in our study reported that they were seriously thinking of quitting in the next 30 days at baseline. As expected, the 6-month prolonged abstinence quit rates were closer to the national average.

Before discussing the meaning and implication of our findings, it is useful to consider study limitations. Biochemical validation of smoking status was not feasible. In addition, we could not employ other means of testing smoking cessation, such as testing expired breath for carbon monoxide, because the apprentices are regularly exposed to occupational hazards that elevate carbon monoxide levels. Therefore, the study relied on self-report of smoking status. The need for validation of smoking cessation in population-based studies has been questioned [37]. We anticipated that apprentices in the intervention group might be less likely to report that they are still smoking if survey data were being collected by the same program staff who implemented the intervention. Therefore, we had one group of staff members implement the intervention components, while a different group collected survey data.

Even though we separated the union training sites into intervention and control groups, it is still possible that there was contamination in this study because it was possible for apprentices in the control and intervention apprentice sites to work together at the same worksites. Such contamination is expected to make the intervention and control groups more alike and bias our results toward the null. Also, we were unable to collect the 6-month survey at the same timeframe for all the sites. We used the same study survey for all sites. This means that the question about smoking at time 3 means different length of time from the intervention for different sites. For the last two intervention sites surveyed, it actually meant that we were assessing whether they maintained their smoking cessation 8 and 9 months after the intervention and not for 6 months as was the case for the other two intervention groups and all the control sites. Our analyses show that smoking cessation rates in these two sites were not significantly different from smoking cessation in the other intervention sites. This limitation speaks to the reality of working with a group that has a fixed academic calendar in which they needed to cover certain material. Thus, they were unwilling at times to accommodate our study schedule and we had to reschedule our data collection to fit their schedule.

Although we had a high response rate for each time period (range 80.7–93.6%), we analyzed data from 1,213 apprentices (67% of baseline) who had information for all time periods of our survey thus making selection bias possible. We conducted sensitivity analyses comparing our embedded cohort of apprentices who had information for all time periods to all apprentices at each time of data collection. There were no significant differences in the demographic characteristics of our embedded cohort and the entire population. In addition, we evaluated cross-sectional smoking cessation rates at each of the study time points (baseline, immediate post-intervention, and 6-month post-intervention) for all the apprentices in the study who met the criteria to be classified as a smoker at baseline and who had contributed to either or both follow-up assessments. Our results show that the shape of the cessation in the cross-sectional group mirror smoking cessation in the embedded cohort of those with data for all time points (Fig. 2).

The strengths of the study are worth noting. We were able to randomly assign apprentice sites to intervention and control conditions in the study thereby increasing the internal validity and limiting selection bias, which could occur if sites with workers who are more motivated to quit self selected themselves into the intervention group. Also, the randomized-controlled design allowed us to compare pre- and post-intervention changes in the intervention group with changes in a control group. The longitudinal design of the study allowed us to assess the prolonged effect of the intervention to see if the smoking cessation we observed after the intervention was maintained for at least 6 months. The longitudinal design, ultimately, revealed that the effect of the intervention diminished at time 3 such that there were no statistically significant differences between the intervention and the control groups. The initial success of the intervention suggests that the need to develop strategies to help apprentices who quit smoking stay quit. Potentially, the length of the intervention could be extended and a system set in place to provide support to smokers who quit.

We based our study on empirical evidence from worksite-based smoking cessation programs. However, further studies are needed to ascertain what works in apprentice-based smoking cessation versus worksite-based smoking cessation programs. Perhaps, redressing disparities in smoking cessation entails complementary efforts in both apprenticeship programs and worksites. This is especially important for construction workers. According to National Health Interview Survey data from 1997 to 2004, occupations with smoking rates above 30% were all blue-collar, with construction workers having the highest prevalence of smoking at 38.8% [34]. Workplace smoking bans can decrease cigarette smoking [19]. However, blue-collar workplaces have been slow to implement bans [22] and many blue-collar workers work outside where they can easily smoke (e.g., construction sites).

This study’s findings have implications for future research and practice on smoking cessation among blue-collar workers. To our knowledge, our study is the first randomized-controlled study to intervene on smoking cessation among blue-collar workers at their training sites in collaboration with their unions. Unions represent many workers in blue-collar occupations and can be another channel through which interventionists can reach blue-collar workers, who, otherwise would be scattered across several worksites [38]. We have not found other reported smoking cessation interventions that targeted this untapped area of worksite health promotion. However, the study also underscores a need to find ways to provide continued assistance with maintenance of smoking cessation to apprentices who quit smoking.

In conclusion, this study demonstrated the feasibility of integrating smoking cessation programs into training programs for apprentices in the building trades. The dissemination of such programs could occur through labor-management health and welfare funds, which provide insurance to some 10 million union members and their dependents, largely employed in the building trades [39]. An insurance-funded program that is delivered annually in apprenticeship programs, and that includes evidence-based behavioral counseling coupled with NRT, would be sustainable and may help with relapse prevention. Additionally, the toxics and tobacco curriculum is readily available through the BUILT project in California, which developed materials using state funds. Public health advocates ought to urge these labor-management health and welfare funds to provide training and worksite-based programs such as MassBUILT, as part of comprehensive wellness programming. Such programs could lead to long-term savings for jointly sponsored labor-management insurance funds.

References

CDC (2008) Targeting tobacco use: the nation’s leading cause of death. National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. http://www.cdc.gov/nccdphp/publications/aag/pdf/osh.pdf

WHO. Why is tobacco a public health priority

Barbeau EM, Krieger N, Soobader MJ (2004) Working class matters: socioeconomic disadvantage, race/ethnicity, gender, and smoking in NHIS 2000. Am J Public Health 94(2):269–278. doi:10.2105/AJPH.94.2.269

CDC (2007) State-specific prevalence of cigarette smoking among adults and quitting among persons aged 18–35 years—United States, 2006. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 56(38):993–996

Haenszel W, Shimkin M, Miller H (1956) Tobacco smoking patterns in the United States. Public Health Monogr 45:1–111

Giovino G, Pederson L, Trosclair A (2000) The prevalence of selected cigarette smoking behaviors by occupational class in the United States. Center for Disease Control and Prevention, Washington DC. June Report No.: 2002-148

Hasenfratz M, Michel C, Nil R, Battig K (1989) Can smoking increase attention in rapid information processing during noise? Electrocortical, physiological and behavioral effects. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 98(1):75–80. doi:10.1007/BF00442009

Leigh JP (1996) Occupations, cigarette smoking, and lung cancer in the epidemiological follow-up to the NHANES I and the California occupational mortality study. Bull N Y Acad Med 73(2):370–397

Nelson DE, Emont SL, Brackbill RM, Cameron LL, Peddicord J, Fiore MC (1994) Cigarette smoking prevalence by occupation in the United States. A comparison between 1978 to 1980 and 1987 to 1990. J Occup Med 36(5):516–525

Sterling TD, Weinkam JJ (1976) Smoking characteristics by type of employment. J Occup Med 18(11):743–754. doi:10.1097/00043764-197611000-00011

Sterling TD, Weinkam J (1990) The confounding of occupation and smoking and its consequences. Soc Sci Med 30(4):457–467. doi:10.1016/0277-9536(90)90348-V

Meeker JD, Susi P, Pellegrino A (2006) Comparison of occupational exposures among painters using three alternative blasting abrasives. J Occup Environ Hyg 3(9):D80–D84. doi:10.1080/15459620600854292

Oliver LC, Miracle-McMahill H (2006) Airway disease in highway and tunnel construction workers exposed to silica. Am J Ind Med 49(12):983–996. doi:10.1002/ajim.20406

Rappaport SM, Goldberg M, Susi P, Herrick RF (2003) Excessive exposure to silica in the US construction industry. Ann Occup Hyg 47(2):111–122. doi:10.1093/annhyg/meg025

Sorensen G, Stoddard A, Hammond SK, Hebert JR, Avrunin JS, Ockene JK (1996) Double jeopardy: workplace hazards and behavioral risks for craftspersons and laborers. Am J Health Promot 10(5):355–363

Sorensen G (2001) Worksite tobacco control programs: the role of occupational health. Respir Physiol 128(1):89–102. doi:10.1016/S0034-5687(01)00268-7

Murray LR (2003) Sick and tired of being sick and tired: scientific evidence, methods, and research implications for racial and ethnic disparities in occupational health. Am J Public Health 93(2):221–226. doi:10.2105/AJPH.93.2.221

Grosch JW, Alterman T, Petersen MR, Murphy LR (1998) Worksite health promotion programs in the U.S.: factors associated with availability and participation. Am J Health Promot 13(1):36–45

Moher M, Hey K, Lancaster T (2005) Workplace interventions for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev (2):CD003440

Campbell MK, Tessaro I, DeVellis B, Benedict S, Kelsey K, Belton L et al (2002) Effects of a tailored health promotion program for female blue-collar workers: health works for women. Prev Med 34(3):313–323. doi:10.1006/pmed.2001.0988

Willemsen MC, de Vries H, van Breukelen G, Genders R (1998) Long-term effectiveness of two Dutch work site smoking cessation programs. Health Educ Behav 25(4):418–435. doi:10.1177/109019819802500402

US-DHHS (2006) In: Services DoHaH (ed) Control of secondhand smoke exposure. Office on Smoking and Health, pp 569–665

Bilginsoy C (2003) The hazards of training: attrition and retention in construction industry apprenticeship programs. Ind Labor Relat Rev 57(1):54–66. doi:10.2307/3590981

Sorensen G, Barbeau E, Hunt M, Emmons K (2004) Reducing social disparities in tobacco use: a social contextual model for reducing tobacco use among blue collar workers. Am J Public Health 94(2):230–239. doi:10.2105/AJPH.94.2.230

Sorensen G, Stoddard AM, LaMontagne AD, Emmons K, Hunt MK, Youngstrom R et al (2002) A comprehensive worksite cancer prevention intervention: behavior change results from a randomized controlled trial (United States). Cancer Causes Control 13(6):493–502. doi:10.1023/A:1016385001695

Fiore M, Bailey W, Cohen S (2000) Treating tobacco use and dependence. Clinical practice guideline. DHHS, Rockville

BUILT [database on the Internet] (2006) State building & construction trades council of California. http://www.sbctc.org/built/. Cited 31 Oct 2007

Barbeau EM, Li Y, Calderon P, Hartman C, Quinn M, Markkanen P et al (2006) Results of a union-based smoking cessation intervention for apprentice iron workers (United States). Cancer Causes Control 17(1):53–61. doi:10.1007/s10552-005-0271-0

Hughes JR, Keely JP, Niaura RS, Ossip-Klein DJ, Richmond RL, Swan GE (2003) Measures of abstinence in clinical trials: issues and recommendations. Nicotine Tob Res 5(1):13–25

Velicer WF, DiClemente CC, Prochaska JO, Brandenburg N (1985) Decisional balance measure for assessing and predicting smoking status. J Pers Soc Psychol 48(5):1279–1289. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.48.5.1279

Velicer WF, Diclemente CC, Rossi JS, Prochaska JO (1990) Relapse situations and self-efficacy: an integrative model. Addict Behav 15(3):271–283. doi:10.1016/0306-4603(90)90070-E

SAS (2005) The GLIMMIX procedure. SAS, Cary, NC. http://support.sas.com/rnd/app/papers/glimmix.pdf. November

King G, Honaker J, Joseph A, Scheve K (2001) Analyzing incomplete political science data: an alternative algorithm for multiple imputation. Am Polit Sci Rev 95(1):49–69

Lee DJ, Fleming LE, Arheart KL, LeBlanc WG, Caban AJ, Chung-Bridges K et al (2007) Smoking rate trends in U.S. occupational groups: the 1987 to 2004 national health interview survey. J Occup Environ Med 49(1):75–81. doi:10.1097/JOM.0b013e31802ec68c

Hughes JR, Keely J, Naud S (2004) Shape of the relapse curve and long-term abstinence among untreated smokers. Addiction 99(1):29–38. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00540.x

CDC (2006) Tobacco use among adults—United States, 2005. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 55(42):1145–1148

Velicer WF, Fava JL, Prochaska JO, Abrams DB, Emmons KM, Pierce JP (1995) Distribution of smokers by stage in three representative samples. Prev Med 24(4):401–411. doi:10.1006/pmed.1995.1065

Barbeau EM, Goldman R, Roelofs C, Gagne J, Harden E, Conlan K et al (2005) A new channel for health promotion: building trade unions. Am J Health Promot 19(4):297–303

Ringen K, Anderson N, McAfee T, Zbikowski SM, Fales D (2002) Smoking cessation in a blue-collar population: results from an evidence-based pilot program. Am J Ind Med 42(5):367–377. doi:10.1002/ajim.10129

Acknowledgments

The research was supported by grant 1R01 DP000097-01 from the National Institutes of Occupational Safety and Health (PI. Dr. Barbeau). C. A. Okechukwu is supported by Robert Wood Johnson Health and Society Scholars program. We would like to thank the president, program directors, staff, and apprentices affiliated with the Massachusetts Building Trades Council for their participation in this study, the Massachusetts Coalition of Occupational Safety and Health (MassCOSH) for assisting us with delivering the Toxics and Tobacco Curriculum and for leading behavioral therapy groups. We gratefully acknowledge the contributions of project staff, including Michael Ostler, Cathy Hartman, Ruth Lederman, David Wilson, Jennifer Kelly, Janice Perates, and Mary Ellen Chambers.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Okechukwu, C.A., Krieger, N., Sorensen, G. et al. MassBuilt: effectiveness of an apprenticeship site-based smoking cessation intervention for unionized building trades workers. Cancer Causes Control 20, 887–894 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10552-009-9324-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10552-009-9324-0