Abstract

Based on a qualitative study of Copenhagen 2021 WorldPride, this article explores collaboration between the local organiser and its corporate partners, focusing on the tensions involved in this collaboration, which emerge from and uphold relations between the extremes of unethical pinkwashing, on the one hand, and ethical purity, on the other. Here, pinkwashing is understood as a looming risk, and purity as an unrealizable ideal. As such, corporate sponsorships of Pride are conceptualized as inherently impure—and productive because of their very impurity rather than despite it. Analytically, we identify and explore three productive tensions where the first involves emergent normativities for what constitutes good, right, or proper corporate engagement in Pride, the second revolves around queer(ed) practices and products that open normativities, and the third centres on the role of internal LGBTI+ employee-driven networks whose activism pushes organisations to become further involved in Pride, developing aspirational solidarity. Reading across literatures on corporate activism and queer organisation, we introduce Alexis Shotwell’s notion of constitutive impurity to suggest that the potential for ethical corporate Pride partnerships arises when accepting the risk of pinkwashing rather than seeking to overcome it.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

On 14 July 2021, less than a month ahead of Copenhagen 2021 WorldPride, Denmark’s leading business newspaper published an article, which stated that ‘pinkwashing is the new business sin’ (Eisenberg, 2021). In the article, spokesperson for Copenhagen Pride Lars Henriksen is cited for saying that it is problematic if businesses only support Pride to buy indulgences, labelling such lip service to Pride as pinkwashing. Thus, Henriksen positions pinkwashing as yet another potential instance of corporate hypocrisy, adding the social movement for LGBTI+ rights to the list of progressive causes with which corporations seek attachment without necessarily taking any further actions (see Vredenburg et al., 2020).

Critical studies of corporate social responsibility and corporate activism are sceptical of the claim that corporations can contribute to the progress of society, arguing that corporations’ social initiatives are but means of maintaining the exploitative relations of capitalist society (Banerjee, 2018; Ehrnström-Fuentes & Böhm, 2023; Nyberg, 2021). Rhodes (2022) coins the term ‘woke capitalism’ for the societal formation that emerges when corporations latch on to progressive causes. Woke capitalism, as Rhodes defines it, is not just another instance of capitalism’s tendency to incorporate critique in order to profit from it (see Chiapello, 2013). Rather, Rhodes worries that woke capitalism poses a threat to democracy, as it seeks to justify the corporate takeover of societal functions hitherto reserved for political actors. “At best,” Rhodes argues in a recent interview (Christensen et al., 2024), “they [corporations] are responding to public sentiment coming from their employees or customers by doing a few benign things to help others. At worst, they’re playing hardball by working to seize political power from the institutions of democracy” (n.pag.).

Following this argument, corporate support for LGBTI+ rights is not just one more way for capitalist organisations to maximise their profits (Burchiellaro, 2023; Tyler & Vachhani, 2021), but may also indicate the degree to which progressive causes and corporate interests are aligned (Christensen et al., 2024). As such, pinkwashing, defined as various strategies of harnessing association with the LGBTI+ movement, generally, and Pride (including but not limited to parades), more specifically, for corporate purposes, is an enactment of woke capitalism.

Interestingly, the labelling of a corporate strategy as ‘washing’, be it green, blue, pink, rainbow, or woke, taints that strategy, indicating its failure to pay anything bit lip service to the evoked social, economic, and/or environmental cause(s) (Berliner & Prakash, 2015; Bernardino, 2021; Sobande, 2019; Szabo & Webster, 2021; Vredenburg et al., 2020). Beyond the critique of corporate engagement with progressive causes, however, some organisation and management scholars have explored the ethical potentials of corporate activism (Christensen et al., 2021; Gond & Nyberg, 2017; Gulbrandsen et al., 2022). Recognising that no corporation is perfect, these scholars argue, should not bar us from studying corporate claims to responsibility and activism as genuinely aspirational, i.e., as actual attempts at improving the environmental, societal, and/or governance imprint of the corporation. Indeed, hypocrisy may be constitutive of corporations and a prerequisite of individual, organizational, and societal change (Brunsson, 1986; Christensen et al., 2020; Santana, 2024). Further, entanglements of the interests of private business and public life may be problematic, but they are not new. To the contrary, corporations have always been politically influential within capitalist societies (Herman, 1981), and rather than upholding an untenable ideal of the separation of corporate and state powers, we might gain more of a chance at changing things for the better by presupposing their interdependence and focusing our attention on how business and society interrelates.

To maintain a critical stance whilst approaching the relationships between business and society constructively, we begin from the assumption that such relationships are ‘constitutively impure’ (Shotwell, 2016). In fact, as Shotwell (2016) points out, we cannot change anything if we simply reject it for its imperfection. “Often,” she argues, “there is an implicit or explicit idea that in order to live authentically or ethically we ought to avoid potentially reprehensible results in our actions. Since it is not possible to avoid complicity, we do better to start from an assumption that everyone is implicated in situations we (at least in some way) repudiate” (p. 5).

When understood as ‘forms of disturbance’ (Shotwell, 2016, p. 9), tensions between capitalist practices and progressive aims may hold potential for social change. That is, we may call out the hypocrisy of corporate practices of ‘washing’, but only in so far as corporations claim a purity they will never obtain. If and when the imperfection of corporate activist relationships is explicated, this very imperfection can become ethically productive. Seeking to contribute to business ethics research on corporate activism, we develop the relational perspective of constitutive impurity in the context of corporate Pride partnerships. To this end, we ask: What are the risks and potentials of corporate Pride partnerships? What are the productive tensions of these partnerships? And how do corporate Pride partners practice a relational ethics of constitutive impurity?

In seeking empirical answers to these questions, we turn to an in-depth study of corporate Pride partnerships at Copenhagen 2021 WorldPride. Based on interviews with corporate partners and Pride organisers as well as observations of partnership events, the analysis focuses on the corporations’ rationales for engaging with Pride as well as the ways in which the partnerships were articulated and enacted: What do the partners say, what do they do, and what do they say they do? Here, it should be clarified that whilst Copenhagen Pride, the local organiser of the global mega event, is not uncritical of its partners, as indicated by our opening quote, the organisation’s official policy is to engage with rather than reject corporations, seeing corporate partnerships as occasions for constructive engagement. Hence, Copenhagen Pride assumes that not all corporate Pride relations are illegitimate and that not all corporate association with Pride is pinkwashing.

We share this assumption, arguing that critique of ‘corporate Pride’ as an inherently illegitimate practice of woke capitalism leads to a critical dead-end. Accepting that corporate involvement in Pride will never be ‘pure’ (i.e., free of corporate self-interest), we suggest, may enable us to see the potentials of such involvement without losing sight of the ethical tensions it incurs. Beginning from the analysis of corporate Pride partnerships, we seek to advance the study of ethical corporate involvement in progressive causes by suggesting that such involvement can—and should—take relational forms of productive tension, a concept that we develop for the study of constitutive impurity in practice.

In what follows, we first establish the theoretical basis for our empirical study by positioning our work in the context of business ethics research on corporate activism, suggesting how queer organising is not only a relevant empirical field for the study of corporate engagement with social movements but may also inform this study theoretically. At this juncture, we introduce Shotwell’s (2016) notion of constitutive impurity, arguing that the productive potential of ethical corporate Pride partnerships only emerges when accepting the concomitant risk of pinkwashing. We then present our case study of corporate Pride partnerships in the context of Copenhagen 2021 WorldPride, detailing our methods of data collection and analysis. The analysis identifies the tensions of corporate Pride partnerships, leading to our discussion of the productive potentials of these tensions as well as the conceptual implications of our findings.

Queering Woke Capitalism

As the LGBTI+ movement has become integral to many societal contexts, corporations have taken an interest in supporting the movement and become increasingly visible at Pride events, raising the question of whether or not the articulation of corporate support is backed by concerted action. The suspicion that corporations are hypocritically purifying their dirty politics with fake queer credentials is often articulated under the label of pinkwashing.

Here, it is important to point out that the notion of pinkwashing is sometimes used in relation to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict where it refers to Israel’s practice of championing LGBTI+ rights as a way of covering up its discrimination against Palestinians (Anderson, 2019). As such, pinkwashing is closely related to Puar’s (2007) notion of homonationalism that problematises how, in many Western societies, a pro-LGBTI+ nationalist ideology is used to legitimise intolerance of other minority groups, especially Muslims, and, thus, to build and sustain a racist, xenophobic political stance against immigrants. Further, and in an entirely different vein, pinkwashing is sometimes used to call out fraudulent and deceptive cause marketing in relation to breast cancer (Blackmer, 2019).

We delimit our use of the term to corporate involvement with LGBTI+ issues, as exemplified by corporate Pride partnerships. Beyond the risk that corporations are waving the rainbow flag publicly without taking any further action to ensure support of LGBTI+ people in their own daily operations or that of their subsidiaries, suppliers, and other central stakeholders, we focus on the ethical consequences of more concerted corporate engagement with Pride. Thus, we begin from the assumption that whilst corporate Pride partnerships can be problematic deflections of exploitative corporate practices, they can also be occasions for changing those practices for the better.

The study of pinkwashing, we suggest, not only extends existing critiques of corporate activism, but may also contribute conceptually to our understanding of the ethics of corporate involvement in progressive causes. As such, the underlying ideology of woke capitalism should, indeed, be queried, but organisational practices of corporate activism may also benefit from being queered (Gibson-Graham, 1996; see also Christensen, 2021). Meaning, we may address corporate Pride partnerships critically and reparatively, productively destabilising currently dominant norms and practices through identification of their relational tensions (Christensen, 2020, 2021). To this end, we offer a conceptual framework for studying corporate Pride partnerships as constitutively impure relations that may become ethically productive in and through the tensions that arise when the social ideals of diversity and inclusion of the LGBTI+ movement meet the logic of profit maximisation of corporate partners. Before establishing our alternative, we detail the critique of woke capitalism, then turn to queer organisation studies, ending this section with the introduction of the relational ethics of constitutive impurity.

The Critique of Woke Capitalism

Whilst corporations are often associated with conservatism, they and their leading representatives are increasingly taking active positions on the pressing issues of our time. The activism of CEOs is, as Branicki et al. (2021) show, almost always directed toward progressive socio-political causes (see also Feix & Wernicke, 2024). And it is becoming more and more common for businesses to (seek to) align their interests with progressive platforms of, e.g., social justice and climate activism (Gulbrandsen et al., 2022; Skoglund & Böhm, 2022). Whilst such alignment may be celebrated as key to positive societal change (Sarkar & Kotler, 2018), scholars more commonly take a critical stance towards purportedly activist practices that regard corporations’ commercial interests as the boundary of intelligibility for activism (Branicki et al., 2021; Girschik et al., 2022; Nyberg, 2021). Although ‘CSR washing’ in its various forms may not be as common as the discourse about it indicates (Pope & Wæraas, 2016), suspicions of corporate hypocrisy continue to define scholarly engagement with corporate activism (Chen et al., 2020; Lee et al., 2024). Thus, the question of how to understand and evaluate ‘woke capitalism’ in the context of business ethics remains unresolved (Warren, 2022).

Weighing in on this question, Rhodes (2022) suggests that woke capitalism holds no ethical potential, arguing that corporate actors not only mine societal causes for profit, but also erode the established checks and balances of democratic societies when claiming activist credentials or ‘wokeness’. This strong critique, however, offers no viable alternatives, and we propose that accepting ‘organisational hypocrisy’ may be a precondition for change (Brunsson, 2019). Thus, exploring the relational tensions of corporate interests and progressive causes (Hoffmann, 2018) may be more productive than simply rejecting their potential.

The Potential of Queer Alternatives

We understand corporate Pride partnerships as particularly relevant sites for the study of the relational tensions of corporate activism. Meaning, corporate support for the LGBTI+ community is by no means exempt from charges of hypocritical ‘washing’, but engagement with Pride holds unique potential for destabilising corporate interests. Agreeing with Rhodes that corporate influence on democratic institutions is questionable, we argue that corporate partnerships with progressive organisations, e.g., Pride organisers, do not leave the partnering corporations unaffected. Or rather, that the relationship between ‘progressiveness’ and ‘capitalism’, as established in and through corporate Pride partnerships and other forms of corporate activism, is not an antithetical dialectic, but one of relational interdependence. As such, corporate involvement with LGBTI+ issues holds unique potential because of the integration of queer activist practices and queer theories of organisation, which invite an ethics of relationality.

Turning to the establishment of queer alternatives in theory and practice, we must begin by emphasizing that the idea(l) of inclusive or ‘LGBTI+ -friendly’ organisations is, as Burchiellaro (2020, 2023) demonstrates, not unproblematic. As already indicated, LGBTI+ inclusion is not exempt from the risk of hypocritical corporate harnessing (see also Calvard et al., 2020; Tyler & Vachhani, 2021), Hence, corporate claims of LGBTI+ activism should not be taken at face value but call for critical scrutiny of rainbow-chasing organisations (Adamson et al., 2021).

Noting the risks of co-optation involved in any corporate embrace of progressive causes (Vredenburg et al., 2020) as well as the specific manifestations of these risks around LGBTI+ issues, it may, nonetheless, prove particularly difficult to contain support for LGBTI+ rights within a narrow frame of corporate self-interest (Branicki et al., 2021; Peterson et al., 2018). Thus, we suggest that corporate involvement with Pride may offer greater potential for fostering productive tensions of relational interdependence than is the case with other instantiations of woke capitalism. This potential lies in the conceptual affinities between the political agenda of the LGBTI+ movement and the academic agenda of queer theory.

As such, the introduction of queer perspectives to organisation studies both enables critique of corporate norms and practices and offers means of opening up corporations to alternatives to currently dominant organisational forms (Parker, 2002, 2016; Rumens, 2017). This is true at the organisational level as well as at the level of corporate ideology, i.e., capitalism. As the feminist-Marxist writer collective Gibson-Graham (1996) note, adopting a queer perspective entices us to ask critical questions of current realities and to actively build alternatives. They suggest that it is possible to both query and queer the organisation of capitalism, identifying oppressive practices and thinking them anew through an open-ended process of questioning normativities, including one’s own (Christensen, 2018; Parker, 2016; Rumens et al., 2019). Applying this perspective to the ideology and strategies of woke capitalism, we begin by identifying its dominant norms and prevailing practices, calling out their repressive uses and seeking out their progressive potentials.

Whilst the association between queer theory and queer activism does not automatically protect the LGBTI+ movement from corporate misuse, it does present a heightened awareness of the risks of misuse, and it offers a conceptual starting point for destabilising corporate activist relationships. In what follows, we detail the strains and tensions of corporate Pride partnerships. Noting how those tensions make for inherently unfinished, imperfect or ‘impure’ relationships, we then introduce Shotwell’s concept of constitutive impurity to establish a framework that ‘stays with’ the tensions, supporting the productive potentials of entanglements between corporate interests and progressive causes rather than aiming to supersede them.

The Constitutive Impurity of Corporate Pride Partnerships: Conceptual Framework

Pride parades and associated events for and by LGBTI+ communities are sites of ritualised protest (Markwell & Waitt, 2009), used by these communities (and their organised representatives) as occasions for resisting marginalisation and exclusion whilst gaining visibility in and support from broader society (Vorobjovas-Pinta & Hardy, 2021). As support for LGBTI+ rights has gained traction in (some parts of) Western societies, corporate participation in Pride parades has become the norm rather than the exception, with corporations organising floats and encouraging their employees to join the parades, offering sponsorships, and otherwise partnering with Pride organisers. Such developments have led to recurrent concerns that Pride parades are becoming too mainstream (Conway, 2022; Holmes, 2022). Still, as shown in a quantitative study of Pride parades across six European countries (Peterson et al., 2018), Pride participants are not representative of the general populace—and this is not just a matter of their sexual orientation. To wit, Pride participants are overwhelmingly “from the middle strata, highly educated, young, and are politically left oriented” (Peterson et al., 2018, p. 1163).

In tandem with the critique of mainstreaming, often raised from within the LGBTI+ communities, the sincerity of corporate involvement in Pride is questioned (McDermott, 2020). In this context, debates over pinkwashing have become largely detached from the specific realities of queerness in Israel/Palestine, with which the concept was first associated (Ritchie, 2015). Instead, pinkwashing refers to the corporatisation of queer space in the neoliberal city: “[D]ebates over pinkwashing in Western gay metropolises have less to do with actual instances of pinkwashing than with struggles over the nature of queerness in the context of neoliberalism” (Ritchie, 2015, p. 620). Whilst such debates continue to be highly contentious, they also point to the productive potential of corporate Pride partnerships, indicating that the very entanglements between the social movement for LGBTI+ rights and corporate interests may alter both.

To appreciate, let alone analyse this potential, however, requires a shift in focus from outcomes of partnerships to the processes of partnering; a shift towards thinking of the partnerships as open-ended and imperfect relationships, which, we suggest, is enabled by thinking of corporate Pride partnerships as constitutively impure (Shotwell, 2016). Critiques of pinkwashing assume a dialectic of the pure and the impure, suggesting that corporations are, indeed, in need of purification, but also—and somewhat ironically—that ‘washing’ is not the right approach to corporate cleansing. Corporations, the argument goes, cannot ‘wash away’ their sins through superfluous association with the LGBTI+ agenda (or any other progressive cause for that matter), but might become pure through deeper association. We reject this dialectic and argue that impurity is the constitutive condition of possibility for corporate Pride partnerships, which cannot overcome tensions between the real risk of unethical pinkwashing and the unattainable ideal of ethically pure relationships but are, instead, configured relationally by these very tensions.

Shanahan (2024) has recently suggested a similar relationship for alternative organising, which, she argues, is constituted by the very risk of co-optation into the mainstream to which it is alternative. Whilst Shanahan is inspired by Butler in suggesting a framework of ‘impure critical performativity’ to explain the alternative’s precarious condition of possibility, we centre Shotwell’s (2016) notion of constitutive impurity, which builds a relational ethics around the presumption that purity is neither feasible nor desirable. Seeking purity, Shotwell (2016) argues, “…is a bad approach because it shuts down precisely the field of possibility that might allow us to take better collective action against the destruction of the world in all its strange, delightful, impure frolic” (pp. 8–9). In offering an ethical stance ‘against purity’, Shotwell’s project is very much aligned with the queer critical-reparative approach to organisational norms and practices, which begins from the vantage point of existing imperfections in order to discover productive potentials. The ethics of constitutive impurity, then, attends to “how we conceive of and practice our relation to a world and a self suffused with otherness” (Shotwell, 2016, p. 10), thereby offering a conceptual starting point for studying social relationships without privileging one side or the other, but, instead, recognizing how all participants in a social setting are constituted by their very relationality in and to that setting.

To unpack the productive potentials of constitutive impurity, we must begin with a critique of current practices of purification, or what Shotwell (2016, p. 14) terms purity moves: the parsing, cleansing, and delineation of the pure and the impure. However, we must also understand that each purity move carries its own ‘dirt’ within. The inherent relational tensions between the pure and the impure are productive of both aspiration and reality. Focusing on these tensions, in turn, invites open normativities, “collectively crafted ways of being that shape subjectivities oriented toward widespread future flourishing” (Shotwell, 2016, p. 18). Saying no to purity, Shotwell (2016) poignantly demonstrates, opens up space for many impure ‘yesses’; it creates room for aspirational solidarity (p. 12), a way of being in the world that recognises current inequalities and injustices, not (just) as impediments to change but (also) as occasions for imagining and enacting change, for criticising that which is and imaging alternatives to it. Consequently, purity moves, open normativities, and aspirational solidarity form the basis of our study of corporate Pride partnerships, enabling us to identify ways in which tensions of constitutive impurity may become productive for Pride organisers and corporate partners alike.

In sum, we posit pinkwashing as integral to corporate Pride partnerships but argue that this does not render them intrinsically illegitimate. Rather, accepting constitutive impurity opens up the possibility that productive tensions can lead to corporate Pride partnerships that are ethical precisely because they recognize their interdependencies and their imperfections. In the discussion, we will return to this claim, assessing its empirical purview and considering its conceptual implications for corporate Pride partnerships, specifically, and woke capitalism, generally. For now, let us note how it enables us to understand corporate Pride partnerships as unfinished and, at times, unintentional processes that are produced by and productive of ethical tensions, where the negotiation of purity moves enables the emergence of new normativities and the enactment of aspirational solidarity. In other words, we study and conceptualise corporate involvement in Pride as inherently impure relations that may become productive through the tensions involved in two-way partnerships, where the commercialisation of Pride is ‘collateral damage’ of the possibility to influence corporations. To prepare for this study and the further discussion of its conceptual implications, we now turn to the presentation of our methods of data collection and analysis.

A Case Study of Corporate Pride Partnerships at Copenhagen 2021: Methodological Considerations

Copenhagen 2021 is the brand name of a mega event, combining WorldPride and EuroGames, that took place in the capital of Denmark in August of 2021. Under the tagline #YouAreIncluded, Copenhagen Pride (which celebrated its 25th anniversary in 2021) and Pan Idræt (a Danish LGBTI+ sports club) joined forces and formed the organisation Happy Copenhagen to deliver the combined event that also offered an expansive arts and culture programme as well as an LGBTI+ human rights forum, part of which took place in the Swedish city of Malmö, thereby spanning the ‘Øresund’ region (Taylor, 2021). The event was substantially impacted by Covid-19 as was our study of it.

Data and Methods

Part of a larger project, this article draws on our concerted engagement with the organisation of Copenhagen 2021, throughout which we were particularly attentive to the collaboration between the Pride organisation and its corporate partners and sponsors. Thus, we joined several pre-Pride partner events, interviewed partners and sponsors, and upheld a continuous dialogue with Pride organisers concerning their thoughts about and feelings towards corporate partnerships. The present study is based on this material, focusing on interviews with corporate partners as well as Pride organisers and supplemented with observations of their collaboration.

On the Copenhagen 2021 website, a total of 90 partners and sponsors are listed and categorised according to different types of engagement, ranging from ‘Main Official Partners’ (10) through ‘Official Partners’ (9), and ‘Sponsors’ (25) through ‘Media Partners’ (8) and ‘Product Partners’ (14) to ‘Institutional Supporters’ (9) and ‘Community Supporters’ (15). All these organisations went through a vetting process and had to pass a minimum threshold for conduct, as set by the Pride organiser’s ethics policy, before becoming officially affiliated (Taylor, 2021, p. 139). We contacted all corporate partners and sponsors (except for LGBTI+ businesses such as gay bars) and 26 consented to an interview, representing all types of engagement from ‘Main Official Partner’ to ‘Product Partner’. We also interviewed five corporate actors that were engaged in Pride, yet not officially affiliated with Copenhagen 2021 WorldPride as partner or sponsor. Further, our material comprises 19 interviews with representatives of the Pride organiser and associated organisations. Most of these interviews (14) were conducted with employees and/or volunteers in Copenhagen 2021. The remaining five interviews are with different community actors (see Table 1 for an overview and Appendix 1 for further information).

We have fully anonymised all representatives of corporations by referring to them only with a pseudonymised name of their corporations. However, it is not possible to anonymise the organisation of Copenhagen 2021, and we have permission to use its name, but we safeguard individual identities by only referring to the organisation.

Interviews were conducted and recorded via Microsoft Teams. This was initially due to restrictions in connection with Covid-19, whether from authorities or self-imposed by organisations, but we continued this practice, as all parties had become familiar with the virtual format during lockdowns. For the interviewee, it allowed for an immediate experience of presence from the interviewer who, in return, had the flexibility of taking notes whilst keeping eye contact. Questions were open-ended and largely the same across interviews, exploring three overall themes: (1) the interviewee’s role and relation to Pride, personally as well as professionally, (2) the organisation represented by the interviewee, its values, conduct, and engagement in Pride, and (3) reflections on criticism of corporate Pride. All interviewees that represented sponsors and partners were also asked to explain any connections between their business and Pride as they saw it, including what they and the Pride organiser, respectively, gained from the collaboration (see Appendix 2 for a sample interview guide).

Some adjustments were made for each interview, enabling us to inquire about claims made by the particular sponsor or partner based on their public self-presentation vis-à-vis Pride engagement. This was done to take the conversation from the abstract level of ideas to a concrete level of unpacking platitudes (e.g., wishing employees to be able to be their ‘true, authentic selves’ at work) to learn what such statements meant in the specific organisational context—especially in terms of actions taken to render them more than aspirational.

Similarly, interviewed representatives of Copenhagen 2021 and community actors were asked about their role and relationship with Pride, their views on and ways of involving businesses as well as how they handled the queer community’s diverse stances and feelings about the crossing of commercial interests with human rights causes.

Besides formal interviews, the empirical material also consists of written notes and collective reflections from ethnographic fieldwork in the form of both participatory and non-participatory observation (see Table 1). The first author, who also conducted all interviews, engaged in an organisational ethnography of Copenhagen 2021 WorldPride, visiting and working from the main office on a regular basis from Spring 2021 (when Danish authorities lifted most corona-related restrictions, allowing for the return to workplaces) until the organisation was closed down in the aftermath of the Pride event. Additionally, all authors observed during the 11 days of WorldPride, attending different events to cover as many aspects as possible.

Of specific interest to this article is the first author’s participation in four business-to-business partner events, three of which took place before WorldPride, that aimed to facilitate informal networking and provide partners and sponsors with a chance to inspire each other with their different approaches to partnership and sponsorship activation. The partner events were also used as occasions for negotiating access and making appointments with interviewees. In making such contacts as well as during observations and interviews, the first author actively used his insider status as an out LGBTI+ person to ‘go native’, creating mutual trust by demonstrating understanding of the empirical context. Several years of experience with organising Pride participation and partnership on behalf of our home institution also proved useful to all authors when raising awareness of our own pre-understandings during discussions of the findings.

In the field, we zoomed in on corporate Pride partnerships by means of ‘awkward ethnography’ (Sløk-Andersen & Persson, 2021), a method for acquiring knowledge about phenomena that are otherwise silenced or camouflaged due to the risk of ridicule, a sense of discomfort, or feeling like a failure. An example of such awkwardness, which we unpack in another part of the larger project, arose when one sponsorship had to be retracted within 24 hours of the announcement of the sponsor, due to (social media) backlash from queer community members (Just et al., 2023). Another example is how the existence of a counter Pride challenges the ‘mainstreaming’ of Copenhagen Pride, charging Pride organisers and corporate partners alike to reflect upon the legitimacy of their collaboration (Burø et al., 2024). Thus, we paid particular attention to tensions that arose around corporate involvement in Pride, using semantic awkwardness concerning the meaning of certain events (as in the examples above) as well as bodily signs of awkwardness (shifting, itching, coughing, self-correcting, etc.) in the case of observations and interviews as indicators of potentially productive tensions around norms and normative assumptions in relation to corporate Pride partnerships (see also Christensen, 2020).

Foregrounding awkward moments of tension, we took our cue from the first meet-up for partners, which was hosted online due to corona restrictions. To comply with authorities’ restrictions on assemblies, and with roughly three months left until WorldPride, Copenhagen 2021 had decided to replace the planned large parade with six comparatively smaller marches of around 1000 participants each. As the change was presented to the partners, the word ‘protest’, which is usually not used in the context of corporate Pride partnerships, appeared on a slide, describing the marches as ‘protest walks’. This created an awkward moment as participants immediately voiced their concern with the choice of words, some by unmuting themselves, others by writing in the chat, asking if the walk could be for rather than against something (e.g., for diversity and inclusion, for human rights, for love). Arguably, the tension, which could be felt even through a laptop screen, had to do with a tacitly shared understanding amongst partners and sponsors that has since been confirmed across interviews—namely, that their involvement cannot take the form of protest aimed at political ends, but must rather be seen as a celebration of sociocultural achievements. Having to explicate this was, clearly, awkward for some but nevertheless deemed necessary for upholding corporate Pride partnerships.

As participants self-selected into our study, we cannot rule out that the organisations who chose to participate believe themselves to be spearheading the process of corporate involvement in Pride. Rather, that is quite likely the case, as, conversely, some of the partners and sponsors who declined our invitation explained they were not ‘far enough’ with their LGBTI+ inclusion to qualify. Whilst the organisational self-selection does skew our data, we accept this as a prerequisite for our study, inspiring us to engage with the corporate partners from the perspective of constitutive impurity. If the organisations we study are more confident about their involvement in Pride than others, what is the basis for such confidence and what uncertainties might it conceal? I.e., what impurities exist within claims of pureness? And how may moments of awkwardness help us draw them out? Thus, we explore productive tensions in the corporate Pride partnerships of those who might perceive themselves to be doing well—suggesting that it is precisely recognition of those tensions that creates the potential for doing better.

Analytical Strategy

Using our own pre-understandings as ‘interpretation-enhancer’ and ‘horizon-expander’ (Alvesson & Sandberg, 2021), we activated and challenged our presuppositions about the reality of corporate collaboration around Pride throughout the research process. At the beginning of each interview, we shared our view that the Pride movement—compared to its rioting roots (Armstrong & Crage, 2006)—has become mainstream, asking informants to reflect on how this mainstreaming allows for the inclusion of businesses, thereby also raising the issues of commercialisation and pinkwashing. To paraphrase Becker (1967), we had to constantly ask ourselves whose side, exactly, we were on, just as we invited informants to reflect on their positions. Such reflection became the starting point for identifying productive tensions.

Beyond raising the issue throughout our data collection process, we have continued the discussion of positionality and potentiality with informants and other relevant stakeholders by presenting preliminary results of our study at various events, organised by Copenhagen Pride and other organisations that constructively interrogate corporate Pride partnerships. Thus, we have learned from the involved organisations and offered them opportunities to challenge and qualify our learnings—and to learn from their involvement in Pride as well as their dialogue with us.

Besides benefitting from recursive interaction with ‘the field’, our notes and interview transcripts have undergone several rounds of coding for which we are inspired by established practices of achieving rigour in qualitative research (Gioia et al., 2013; Grodal et al., 2021). We began by coding the material inductively to minimise the risk of excluding empirically emerging themes of relevance based on preconceived notions of corporate Pride partnerships. The initial coding was done in the context of our larger project, and for this particular study we zoomed in on material that explicitly related to pinkwashing, sorting this part of the data into three broad categories: First, a category of practices and articulations that suggest corporate Pride partnerships can move ‘beyond’ pinkwash, and second, a category of instances that refute this suggestion. Finally, we included a residual or open category of ‘other’ instances that caught our attention, thereby leaving room for complexities and alternative interpretations that do not unequivocally belong to either of the opposed categories, but which nevertheless point to awkward and/or productive relations.

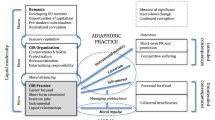

During the initial categorization, we became aware of tensions within and between the categories, as risks (i.e., pinkwashing) and potentials (i.e., progressive change) of corporate Pride partnerships were articulated in relation to each other. This realization inspired us to consider whether and how to approach pinkwashing critically and productively (i.e., with the aim of querying and queering current practices). Noting how the articulated tensions often revolved around issues of (im)purity, we introduced Shotwell’s relational ethics of constitutive impurity as our aggregate dimension and established the three second order themes of purity moves, open normativities, and aspirational solidarity in an abductive dialogue between emerging empirical tensions and Shotwell’s conceptual framework. Thus, we specified inductively identified productive tensions of corporate Pride relationships along Shotwell’s conceptual lines. First, as purity moves, i.e., relations of in- and exclusion that establish the normative context within which corporate Pride sponsorships currently operate. Second, as open normativities, relations of contestation that enable change from within. Third, and finally, as relations of aspirational solidarity that prefigure the productivity of future relationships (for an overview of the data structure in its final form, see Fig. 1).

Productive Tensions of Corporate Pride Partnerships: Findings

We structure the report on our findings according to the final round of coding, identifying three productive tensions. First, those involving corporate partners’ and Pride organisers’ purity moves that establish an emergent normativity of corporate Pride relations; what constitutes right, good, or proper partnerships? Second, tensions revolving around contestation of the emergent norms, focusing on the ways in which some of the partners question their own purity when encountering and/or promoting queer practices and products, leading to (more) open normativities. Finally, we examine how some organisations are pushed by internal LGBTI+ employee-driven networks whose activism encourages these organisations to engage with tensions of aspirational solidarity, becoming further involved in Pride and developing corporate advocacy of LGBTI+ rights and issues. The analysis leads directly to our concluding discussion, in which we reflect upon the constitutive impurity of corporate Pride partnerships and suggest how our findings may contribute to the establishment of a relational ethics of corporate involvement with progressive causes.

Purity Moves: The Emergent Normativity of Corporate Pride Sponsorships

“I’m wearing some partner products, partner products are on display over there, and we’re even drinking partner products.” [Everybody laughs] The words stem from a partner event and are uttered by a leading organiser of Copenhagen 2021. Just a week before the official kick-off of WorldPride, the partner event takes place in a cosy courtyard of a hotel that is itself amongst the sponsors of WorldPride. In his speech, the organiser brings a toast, wishing everyone a happy Pride, after which he, with a nod to the Pride products on display in the bar, encourages the participants to take turns sharing activation plans for their partnership or sponsorship. Many participants eagerly and passionately talk about their engagement in Pride, indicating why it is important to them. A representative from GreenEn, a renewable energy company who is an official partner of Pride, speaks enthusiastically about their plans for lighting up three of their wind turbines in rainbow colours during WorldPride. And the idea, the speaker ads, comes from a gay employee who works as a blade engineer in the organisation. [Applause and cheers] Then a representative from the product partner WatchMe steps to the fore, showing on his wrist the watch with a rainbow strap that his company contributes. He does not, however, stick to arguing how the values of his company are aligned with those of Pride, but also uses the occasion to criticise a competitor that has also produced a Pride edition watch—without being an official product partner. This, the WatchMe representative states, is not the correct way for a company to engage in Pride. What the competitor does, he continues in a scornful tone, is pinkwashing. (Fieldnote, 05.08.2021)

Whilst accusations of corporate pinkwashing usually stem from the LGBTI+ community, in the observation note above a company representative uses the term to criticise another company for taking advantage of Pride in what is perceived as an incorrect manner. This example is illustrative of an emergent normativity of corporate Pride partnerships, which is enacted through a purity move of in- and exclusion. Perhaps not surprisingly, considering their status as partners and sponsors, our corporate informants all accept and reinforce the norm of making an economic contribution to Pride and/or other LGBTI+ organisations. Similarly, representatives of the Pride organiser distinguish between legitimate corporate associations with Pride and illegitimate pinkwashing, using economic support as the line of demarcation between pure and impure relations. As one interviewee explained:

Well, I think it, you know, it is pinkwashing, or sorry, it can be pinkwashing, and it can be window dressing if they are, if the business is not being authentic and if Pride is not being careful about who they partner with. You know, there is a difference between, you know, I’m trying to think of a…so [name of coffee shop], for example, are sponsoring Copenhagen 2021. So, [name of coffee shop] will probably have their usual window full of rainbows. The local franchise has gone through the vetting process and meets the ethical standard for Copenhagen 2021. You might find, and I don’t know that this happens, but let’s say [name of other coffee shop], you might find that there’s rainbow flags all over their windows. Well, they’re not sponsoring. As far as we know, they’re not doing anything. They’re just putting rainbow flags up. Now, question is, are they putting rainbow flags up to be inclusive and to be a part of Pride, or are they just cashing in on Pride? (Copenhagen 2021)

Thus, a proper corporate Pride relationship involves a flow of money from corporations to Pride. In fact, donations are taken for granted to such an extent that the practice has become normalised—and remains unchallenged. Consequently, several partners and sponsors no longer see it as sufficient to hand over money, which is perceived as buying indulgences:

If you just adorn yourself with borrowed plumes and hand over a check. That’s just cheap. (Beanz)

That we see this kind of event as worth investing a significant amount both of money, but also organisational time, like a lot of people spent a lot of time making it the success that it was, you know. It was quite a commitment for us as an organisation. That wasn’t even really questioned in the way it might have been a couple of years ago. (GreenEn)

Similarly, an informant from an LGBTI+ organisation explicitly uses the notion of ‘indulgences’ to suggest that companies must do more than pay up to avoid charges of pinkwashing:

Well, I’d say it’s indulgences if you just give your LGBT-employees that party once a year, but the rest of the year you don’t think about them […] And I’d say if you walk that day [in the parade] and donate money to an LGBT-organisation or something, then to me that’s still just indulgences. If you don’t commit to working consciously with this [LGBTI+ inclusion], then to me it’s pinkwashing. (Dk Inclusion)

Another interviewee describes how her company’s Pride partnership has changed her attitude towards other companies that may think they are supporting Pride by using rainbow colours, but do not donate to the LGBTI+ community:

I guess I have been extremely naïve back then [before the company became a Pride partner] and thought: “Hey cool, look at all those businesses raising the rainbow flag!” So, I guess you can call it a work injury when I now think to myself every time I see some business, say a small coffee truck in [name of department store] during Pride week: “I wonder whether they have even paid back [to the LGBTI+ community] or know that they should?” (ChoCo)

To this interviewee, the visibility in flying the rainbow flag and decorating shops in rainbow colours has, over the years, come to appear insufficient—too easy, too little. Impure.

Reflecting further on the issue, the same interviewee explains how the organisation’s collaboration with Pride has raised awareness around correct forms of corporate engagement. This reflection leads her to admit past ignorance; she now realises how the company, before becoming a partner, likely was guilty of supporting only symbolically—doing what she, today, thinks is inadequate:

I’m probably digging my own grave here, because some five years ago, without being able to say exactly what we did, I’m pretty sure we did something Pride-related with our chocolate bars. And we didn’t give much thought to supporting beyond posting a picture [on social media]. But that [the critique of others] is, naturally, because we’ve become extremely enlightened after initiating our partnership with Copenhagen Pride. (ChoCo)

As economic support becomes the norm, it becomes self-evident; a bare minimum of what can be expected, leading corporations to search for other meaningful ways of contributing. The normative corporate Pride relationship, then, is not just pecuniary; rather, the flow of money from corporations to the Pride organisation is supplemented with a flow of insights from Pride to corporations who are willing to learn from the relationship.

Many partners and sponsors state that they want to do more than simply support economically, as in the case of the chocolate producer whose royalty agreement with the Pride organiser becomes a reminder that the risk of criticising commercial interests is always present:

That’s because even as we support Pride economically through our sales of chocolate bars it’s still hugely commercial. The collaboration is commercial. And again, cynical voices will say that we do this only to profit from the values and target groups of Pride. (ChoCo)

The risk of backlash remains, as Pride organisers are also aware and careful to inform corporate partners about:

And we, I always talk through any potential new partner, through the potential backlash that they might get, because I think tell them from the start that this is not, you know, don’t expect to just come in and give money and everything’s going to be totally…and the whole community could go ‘wonderful’ and then suddenly buy you a beer. You will get backlash. And let’s kind of be proactive. Think about what that might be. Obviously, try and mitigate it as much as possible, but you can’t always do that, but expect it and just be prepared to answer. Be prepared to say we’re on a journey and yeah, we’re listening. (Copenhagen 2021)

The commercial nature of the collaboration, then, must not exclude the possibility for corporate Pride relationships to evolve. And, again, the norm is for corporations to learn from—and be influenced by—the partnership. As expressed by other interviewees:

You also begin to read up on the history of it all, to learn what Pride is and why it is the way it is. And then you start seeing, oh [swearing], there’s more to it than just the party. There’s also the protest, right? And being proud of who you are, right? (Beanz)

Besides some brand-related spill over, I think what is interesting for us is that we can get insight into, how to say, what matters for a movement like this one. If we as a company want to push an agenda—and we’re far from champions when it comes to diversity and inclusion, and that we know. But we get to establish a fantastic collaboration with an organisation that can help us define how to go about this agenda. I let Copenhagen 2021 know that we’d like their assistance with developing a diversity policy […] and just like that we obtain knowledge from a group of people that we otherwise perhaps wouldn’t have easy access to. (All Colours)

Not only do corporations have to pay for the party; they should also learn from the movement—and relations that are not constituted along these lines are excluded.

Even amongst those who are included, however, the emergent norms of proper and pure corporate involvement in Pride may, in some instances, turn restrictive. Since all partners want to appear progressive by saying and doing all the right things, or at least not making any blatant mistakes, a representative of one of the main sponsors sensed discomfort at the partner events:

I think, you know, I was a little bit surprised that you can read between the lines that there is a sense of, you know, people are uncomfortable, and they tried to not put their foot in the piano and how they speak and engage about it. So, there’s a huge respect for doing the right thing. But in that almost a little bit of paralysing, you know, being concerned. So, it’s almost like a first date where you don’t, you know, you’re cautious of every word that comes out and so on. (Sporty)

Whilst corporate partners may become, as this informant says, ‘paralysed’ in the attempt to be inclusive, the notion of inclusivity also gives Pride organisers reason to reflect. The official WorldPride slogan #YouAreIncluded may suggest absolute and achieved openness, but inclusion continues to incur tension, as indicated by the awkwardness that shines through in one Pride organiser’s appraisal of the slogan:

So yeah, it’s, it’s about our values, I think as an organisation and what we aim to achieve and through everything that we do and it’s about, I think it’s, it’s a brilliant kind of slogan, hashtag, because it’s, it’s so all-encompassing, it doesn’t kind of single out any, any element that says, well this is what we’re saying, everything you, all of you are included. So, I think it’s a very powerful statement to say that. And it’s also a powerful kind of…quite a lofty ambition to say that’s what we’re going to do. We are going to include everyone is quite an ambitious statement. But I think it’s, it’s what we should be aiming for. (Copenhagen 2021)

As emergent normativities define acceptable practice, they also establish boundaries for legitimate forms of involvement, which for most partners and sponsors is a matter of finding meaningful connections and synergies between what they do—that is, what products and services they sell—and the needs of the Pride organiser. For instance, a tech company contributed with the digital platform for streaming online events globally:

We want to be involved in a meaningful way, and we don’t just want to, you know, you don’t see a BigTech rainbow logo, and we call it a day, right? Like, I think it’s for us, it’s less about, you know, just sort of being part of the programme and more about how could we leverage that platform to help us internally become more inclusive, but also leverage our own platforms to help externally? (BigTech)

This final purity move signals that involvement should not be random. Beyond contributing money and learning from Pride, corporate partners must find means of aligning their services and products with Pride in meaningful ways.

Thus, we identify an emergent normativity for corporate Pride: Companies not only ought to ‘give something back’, economically speaking, but must also engage beyond the economic transaction to appear authentic and genuine in their Pride participation, finding ways of learning from Pride and of activating the partnership meaningfully. This becomes the entry-level commitment but also a point of tension and contention, as organisations remain doubtful of what might be ‘enough’ and grapple with how to keep becoming ‘better’, just as the issue of what inclusion might incur for Pride remains contentious. The next round of analysis focuses on what partners and sponsors do to keep improving themselves, highlighting tensions around the continued negotiation of the norms of corporate Pride partnerships.

Open Normativities: Queering Corporate Pride Partnerships

At the beginning of an interview with a representative from one of the corporate partners, the interviewee included a statement on his personal pronouns as part of the initial presentation—a practice that he explained he had picked up from the human rights conference that took place during WorldPride. Whilst admitting imperfection in that it is not in all situations that he remembers to share pronouns, it is nevertheless an example of how a practice that emanates from the LGBTI+ community is transferred to the corporate setting. The interviewee said he never experiences being misgendered himself, but shares his pronouns to make it easier for others to do the same:

It’s the right thing to do. It’s helpful for people who don’t necessarily know what your pronouns are, and also shows that I’m not assuming that you know what my pronouns are. And for me, whilst I am cis, you know, and it’s never been something that’s preoccupied me, I know for a lot of people, being clear about gender identity is really important. So, if they see other people sending a signal that they’re sharing their pronouns and they do it themselves, yeah, and it sends a signal that ‘hey, we know this is something that is a part of your identity’. (GreenEn)

Similarly, the interviewee from a recruitment company, whose main contribution was to help Copenhagen 2021 with outplacement of its employees as the event of WorldPride came to its conclusion, reflected upon how the organisation benefitted from interacting with candidates that they would not normally meet:

In return, we get, we definitely get a heightened consciousness about how, amongst other things, it is like to be a minority on the labour market, right? I mean, how we can learn to communicate differently, for example in our ads, how we can learn to become even better at meeting people … I mean, I’ve got people in here that, you know, people that define themselves as men and arrive in dresses, wearing long nails and such, right? And that’s rare. It’s truly a rare sight because we more often see white shirts and such, right? So, we’re prompted to remember to consider: how do we also include this type of people in our processes? Not that we don’t do it already, but perhaps there’s something in our language, our communication, that keeps these people from approaching us. (JobNow)

ReadMe, a medium-sized book publisher, describes its involvement in WorldPride as an ‘eye opener’. ReadMe is a product partner, contributing a guidebook, which features 111 attractions for (LGBTI+) travellers in Copenhagen. The publisher’s involvement in Pride is limited to the one product wherefrom a financial contribution for every copy sold is donated to Copenhagen 2021. In our interview, the company representative repeatedly stressed that besides the travel guide ReadMe does not engage in Pride. This was important for her to emphasise because the publisher does not want to ‘strut in borrowed plumes’, as she put it. This reluctance to ‘oversell’ ReadMe’s partnership with Copenhagen 2021, however, does not keep the collaboration from impacting the organisation. The revised guidebook comes with 26 added places, focused on LGBTI+ history and culture in Copenhagen but also on including other marginalized experiences:

I think our work with the book has been, well, it’s been an eye opener. I remember [name of new co-author of the book] came by, went through the original book, and the first thing he said was that it’s ‘very white’. And now when I think about it, I can see that he was right. What [name of colleague] and I had initially picked out were things we had found interesting from arts and culture, history, and architecture. And that’s been based on the places we frequent in our everyday lives. We don’t give much thought to what’s going on at different LGBT bars. I think it was super nice to get [new co-author] onboard because not only did he add an LGBT-focus, he also made sure, as he said, ‘now, remember, there’s that new Queen Mary statue next to Vestindisk Pakhus’ [for explanation, see below]. Basically, we need to remember to include minority perspectives and histories of oppression that don’t necessarily relate to LGBT but relate to other groups than us white people living here in Denmark. (ReadMe)

The collaboration on the new version of the guidebook, in other words, helped ReadMe learn about and include intersectional histories and perspectives that had been excluded from previous versions. A concrete example is the inclusion of the ‘I Am Queen Mary’ statue, which is the first public statue of a woman of colour, and the first monument to Danish (ongoing) colonial history, in Copenhagen.

In the case of the guidebook, then, the corporate Pride relationship seems to position LGBTI+ communities as the driving forces behind companies’ Pride-related activities. And all corporate partners stress how they are learning from Pride, which is also what the Pride organisers are expecting the partners to do (and is part of the emergent normativity, as identified above). As one organiser who works specifically on partnerships with the culture industry said:

So, there is a lot of educating, and we’re very open to, we always say it’s progress, not perfection. We don’t expect all of the culture institutions that we work with to be perfect when we engage with them. But what we do demand is that they are open to and know that being engaged with Copenhagen 2021 also presupposes that we think they will work with Copenhagen Pride in 2022. And that also means that they over the years need to become better, you know, unlearn some things, open their own minds, gain insights into what it means to be an LGBTI+ person in not only Denmark, but for us specifically what it means to be an LGBTI+ artist, what it means for an LGBTI+ artist when they are only ever booked for exhibitions or events centering in on LGBTI+ art. And trying to open their minds there, that there is art that is on par with quality to any other art. (Copenhagen 2021)

Whilst this may be seen as a purity move (if you do not learn from Pride, you are not a legitimate partner), the articulated tension also opens up corporations to new normativities. And it opens up corporate Pride relationships to further negotiation of the norms of in- and exclusion as well as of the specific forms that partnerships may take. The emerging tension, here, is whom to include how and how much credit to take for what has been done. In the third and final section, we unpack the productivity of this tension to explore whether and how corporate Pride holds potential for aspirational solidarity.

Aspirational Solidarity: Workplace Activism and Corporate Advocacy

As already indicated in the fieldnote that opens the first round of analysis, an openly gay member of the organisation was responsible for one of GreenEn’s more spectacular displays of support for Copenhagen 2021, as he persuaded the organisation to light up three wind turbines in rainbow colours during the event. Such internal activism, one might argue, lends legitimacy to corporate initiatives. Thus, several of the corporate interviewees professed a bottom-up approach to Pride engagement, and the Pride organiser also noted the active involvement of corporate partners’ employees:

And a lot of these...you tend to find that most of the involvement comes from their HR people, their employees, and the resource groups wanting to get involved, which is always encouraging because this is actually the employee telling their employer, we want you to go and partner and that we can kind of, yeah, get through. We can take positive action within the organisation. So, it does, it does usually come from a good place. (Copenhagen 2021)

As a case in point, a diversity and inclusion project manager in a pharmaceutical company repeatedly referred to himself as being part of an LGBTI+ movement within the workplace due to his dual role as a professional, working with issues of inclusion, and as a volunteer, heading the company’s LGBTI+ network. The network, which is for LGBTI+ people and allies, is used as an employee resource group that advises management on how to become better at including organisational members who identify as LGBTI+. An example of a concrete outcome, produced through this relationship, is the introduction of a company-wide right to a minimum of eight weeks paid leave for all non-birthing parents, regardless of gender:

The parental leave for non-birthing parents is something that’s very concrete that will benefit our LGBTQ colleagues. Now management is asking: ‘Well, what’s next? What’s the next policy or guideline that the LGBTQ community would want to show that the company supports?’ So, we’re also asking ourselves in the LGBTQ group ‘Hey, what do we want?’ Maybe we want a transgender guideline with paid hospital leave for someone who just had gender reassignment surgery. Management is listening, and they want to find out from us, what we want from them. The parental leave was a big hit, but we’re kind of like, well, we need something else for next year because, you know, we cannot fly that rainbow flag again without saying that ‘Hey, during the past 12 months, this is the concrete, tangible things that we did for the community’. (BigPharma)

The policy on leave for all non-birthing parents serves as an example of how diversity and inclusion work is and can be done with the groups of people that are to benefit from it—but the example also indicates that the active involvement of the company’s LGBTI+ network is a necessary precursor to becoming aware of needs in the first place. The function of the annual Pride event becomes that of an occasion for taking stock and recommitting since BigPharma will need to have something ‘to show for it’. This is congruent with our previous analytical points around emergent normativities, but it also pushes beyond claims to purity in a perpetual aspirational move. As the interviewee continues to explain, the risk of appearing to pinkwash in the public eye might come from a position of not knowing the internal workings of the organisation. Yet, the risk of potential pinkwashing allegations can be used productively when committing to action through external communication of the gradual progress made.

Home4All, a furniture company, takes the effort to grant equal rights to parental leave a step further by advocating a change in national legislation, as the company believes it would otherwise indirectly contribute to creating labour market inequalities:

I was working on solutions for parental leave, wanting to add diversity to our personnel handbook, so it also accounted for the possibility of being a ‘co-mother’ and not just mom and dad. I wanted for all employees to feel represented and close the loophole that existed legally for homosexual men who were practically cut off from 14 weeks’ leave, because the weeks were bound to the mother. The change was approved in Home4All, and an employee immediately claimed the benefit, so it cost us money from day one and still the policy change was adopted. Then, through our partnership with Dk Inclusion, I pushed the ministry [of equality] to look into how the legislation could be changed accordingly. Otherwise, as I see it, Home4All would produce inequalities as employees working for us enjoy better conditions compared to working for the hairdresser on the corner or any other local shop. (Home4All)

For both Home4All and BigPharma, the Pride event is an annually recurring occasion for taking stock of progress and a lever for re-committing to LGBTI+ inclusion.

One difference between the two, however, is that Home4All has actively decided not to be officially associated with Pride as partner or sponsor. Instead of spending money on joining the parade, which the interviewee problematises as a party for the few, Home4All works together with the organisation Dk Inclusion to develop and distribute resources that can inspire workplace inclusion, thus widening the circles of aspirational solidarity:

…We have also worked on some material about pronoun use, soon to be launched (…) but it is always from a position of ‘let’s do it even better’ and never ‘see how great Home4All is’. (Home4All)

Arguably, Home4All does benefit commercially from relating to LGBTI+ issues, but the company chooses to partner with a more community-oriented organisation and to steer surplus from rainbow-themed products in the direction of specific projects that may benefit the LGBTI+ community, generally, as well as LGBTI+ employees at Home4All, specifically.

Pride organisers also note how corporations may sometimes lead societal change but point out the dilemma of persuading members of the LGBTI+ community to let corporate actors fight for them. Corporations, then, may have political clout, but their social legitimacy remains contested; meaning, Pride organisers who partner with corporations must defend the value of such partnerships to the communities they represent. As the interviewee from International Inclusion, the organiser of the human rights programme at WorldPride, recounted:

… [When working to improve LGBTI+ rights internationally] we pull in companies to help tell the story of LGBTI inclusion in that specific society. And Singapore is probably the best example of that. We actually had our conference…again, homosexuality is criminalised in Singapore still. We actually had our conference, though, in the IBM head office in downtown Singapore and through the invitation of their global manager for the APAC region, Asia Pacific region, she sent out an invitation together with me to 15 CEOs of other companies, member organizations of International Inclusion, and even some that were non-members, to sit around a table and discuss the topic of LGBTI inclusion in the Asia Pacific region and specifically in Singapore. And so that was so powerful. These are decision-makers, senior decision-makers, sitting around a table in a business environment, talking about LGBTI inclusion. […] And that is exactly the dynamic I’m talking about. So, there’s an incredible amount of power. And I’ll be frank with you, it’s sometimes hard to convince civil society organisations of this dynamic, because they’ve just seen capitalism as such a bad thing. I mean, there’s good things as well, of course, but they see it as such a bad thing. But if we work with them, which is what we’ve been doing for 15 years now, you can really make it benefit the community. That’s, that’s what we always try to do. (International Inclusion)

In sum, the issue is not how to create pure corporate Pride partnerships, but how to continue activating tensions of the inherently impure relationships between corporate interests and social progress—how to challenge purity moves and keep opening up normativities, thereby enabling aspirational solidarity.

Against Purity, for an Ethics of Relationality: Concluding Discussion

Even as they work to separate the ‘pure’ from the ‘dirty’, purity moves are inherently relational, always already implicated in that from which they seek separation. By the logic of purity, any crossing of boundaries, as when corporate Pride partners cross from the corporate domain to that of activism, produces dirt—or, we might say, taints the ideals and practices of one domain with those of another. In the case of corporate Pride partnerships, such impurity may spell failure; corporate Pride will never become identical with the ideals and values of the LGBTI+ movement in their ‘pure’ form. Thus, one may argue that corporate involvement is inherently bad for this social movement, just as corporate involvement is bad for democratic society (Christensen et al., 2024; Rhodes, 2022). By the same logic, however, corporate Pride partnerships will never serve ‘pure’ capitalist ends either; meaning, it is bad for business as well. Whether positioned on the corporate or activist side, then, one may argue for the maintenance of boundaries.

By the logic of constitutive impurity, however, maintaining boundaries obstructs any potential for change. Drawing inspiration from Tsing’s notion of ‘disturbance regimes’, Shotwell (2016, p. 9) argues, that it is the very interruption of purity that produces agential potential. And more fundamentally, it is the very relations between the pure and the impure that produce both; as social actors, we are nothing if not disturbed. Thus, purity moves may be designed to form one-directional relationships of in- and exclusion, pushing out the dirt, as it were. Yet they contain within them the possibility of disturbing the norms on which they build, opening them up to the production of alternative normativities and aspirational solidarities. Rather than terminating impure relationships, then, maintaining them may lead to progress—when accepting the inherent mutuality of relationships, everyone is susceptible to the influence of the other. As such, constitutive impurity may serve as a first principle for the development of a relational business ethics.

As most of our interviewees were keenly aware, no matter what a corporation does in relation to Pride it risks criticism: If the corporation does not show support of LGBTI+ rights, it can be criticised for that, and if it gets actively involved in Pride, it risks criticism of doing so for commercial purposes only, for not doing enough, and/or not offering the right kind of support. For Pride and other social movements, the risk of corporate relationships is that corporations influence the social causes negatively, harnessing them for capitalist purposes. Meaning, Pride organisers may benefit economically from the partnerships, but risk critique of ‘selling out’, of becoming too mainstream by corporate implication.

As we discuss below, our findings emphasise the productive tensions of corporate Pride relations, as participants perceive the progressive potentials of involvement as outweighing the risks it incurs. However, it is important to recognise that pinkwashing remains a real problem whenever corporate actors enter the field of LGBTI+ activism. As the metaphor of ‘washing’ implies, corporations may claim a purity they do not possess, whilst Pride organisations, and the LGBTI+ movement more broadly, may become tainted from the encounter. Along these lines, it is worth noting that the ostensibly purifying relation of ‘washing’ is, in our material, deemed impure and, hence, excluded. Thus, the purity moves employed by corporate partners delineate proper from improper types of engagement, thereby establishing emergent normativities of donating money to Pride, learning from Pride organisers, and connecting meaningfully with Pride (i.e., through the corporations’ own products and services, making a material as well as pecuniary contribution to the Pride event).

The correct or proper corporate Pride relationship, as established in our material, is not just an exchange of money (from corporations to Pride) but also of values (from Pride to corporations), but this does not mean that the relationship has become pure, that it has moved ‘beyond’ the risk of pinkwashing. To the contrary, several of the corporate partners of WorldPride have been directly accused of pinkwashing, if not in the sense of profiting off Pride without ‘giving back’, then in the sense of not committing strongly enough to internal changes and/or covering up other misdemeanours with their LGBTI+ activism. And, similarly, Pride is accused of having sold out and gone mainstream, of losing its purity from the very association with corporations (Just et al., 2023). The baseline, however, is that no matter how imperfect the partnering corporations may continue to be, they have quite clearly improved their relationship with the Pride organisation and, in some cases, other parts of the social movement for LGBTI+ rights—just as the Pride organisers/the LGBTI+ community benefit, at least economically, from the relationships.

As we have shown, the tensions between pinkwash and purity are productive in several ways. One is the establishment—and constant negotiation—of new norms for what is deemed ‘good’ organisational practice in relation to Pride. Here, the Pride organiser, as representative of an activist community, seeks to influence societal norms beyond the target (partner and sponsor) organisations, “such that the changes they seek become taken for granted across a wider field or society” (Briscoe & Gupta, 2016, p. 672).

Another potential for change arises from the queering of products, services, practices, and/or norms of corporate partners; whether by changing an individual habit, as in the case of the GreenEn representative who now mentions his pronouns when introducing himself, or by changing a product to render visible the history and culture of LGBTI+ people, as the publisher ReadMe did when updating the travel guide to Copenhagen. In each of these cases, a specific relationship with Pride opens up normativities—within the involved organisations and/or in relation to society.

Finally, growing recognition of and support for the rights and resources of internal LGBTI+ (activist) employee networks indicates that commercialism does not necessarily exclude activism. Enabled by the companies’ Pride participation, activist employee resource groups may use their insider-knowledge about the structures, cultures, and practices of the organisation to which they belong to persuade and educate management (Briscoe & Gupta, 2016; Skoglund & Böhm, 2020), seizing the opportunity for change and pushing current boundaries of aspirational solidarity. In its extreme, this push leads corporate partners to intervene directly in political processes to, for instance, advocate changes in legislation. This may be seen as exactly the kind of corporate activism Rhodes (2022) equates with woke capitalism, but it is noteworthy that the most directly political corporations in our study engage in public deliberations about regulatory initiatives, intervening on the side of more concertedly progressive regulation. We turn to conceptualizing this point shortly, but first unpack the implications of our findings at the level of corporate Pride partnerships.

Having shown how relational tensions can be productive, it is important to reiterate that they are so, precisely because they are not unproblematic. Thus, the development of new norms of interaction may be celebrated for their queer potentials but should immediately be queried for their normalising tendencies. Normativity is often—in queer theory, in LGBTI+ communities, and in the Pride movement—equated with oppression, cisheteropatriarchy being the socially dominant and taken for granted norm from which queer scholars and activists seek liberation (Mauldin, 2023; Rumens et al., 2019). Therefore, the ideal of much queer organising is to somehow move beyond the realm of the normative, to live without norms. However, defining queer as non-normative is, according to Shotwell (2016), in itself a problematic purity move; living without norms is not a state of freedom, but a life without recognition, an impossible life (see also Butler, 2004, p. 115).