Abstract

The majority of workplace incivility research has focused on implications of such acts for victims and observers. We extend this work in meaningful ways by proposing that, due to its norm-violating nature, incivility may have important implications for perpetrators as well. Integrating social norms theory and research on guilt with the behavioral concordance model, we take an actor-centric approach to argue that enacted incivility will lead to feelings of guilt, particularly for prosocially-motivated employees. In addition, given the interpersonally burdensome as well as the reparative nature of guilt, we submit that incivility-induced guilt will be associated with complex behavioral outcomes for the actor across both home and work domains. Through an experience sampling study (Study 1) and two experiments (Studies 2a and 2b), we found that enacting incivility led to increased feelings of guilt, especially for those higher in prosocial motivation (Studies 1 and 2a). In addition, supporting our expectations, Study 1 revealed that enacted incivility—via guilt—led to increased venting to one’s spouse that evening at home, increased performance the next day at work, as well as decreased enacted incivility the next day at work. Our findings demonstrate that enacted incivility has complex effects for actors that span the home and work domains. We discuss the theoretical and practical implications of our results.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Although used in tandem with similar self-conscious emotions such as regret and shame (Breugelmans et al., 2014; Lindsay-Hartz et al., 1995; Tangney & Dearing, 2003), guilt is uniquely relevant in the context of enacted incivility. Guilt captures feelings of distress resulting from interpersonal harm (e.g., My behavior caused harm to others), whereas regret captures broader emotions that encompasses both interpersonal as well as intrapersonal harm (e.g., My behavior caused harm to myself; Breugelmans et al., 2014). In addition, whereas guilt is a behavior-specific emotion (e.g., I committed a bad behavior), and is therefore more relevant in the context of daily incivility, shame is a person-specific emotion that captures reflections of unchangeable aspects of the self (e.g., I am a bad person) (Baumeister et al., 1994; Tangney & Dearing, 2003; Tracy et al., 2007). Thus, given that incivility is conceptualized as a behavior that fluctuates from day-to-day as opposed to an enduring tendency (e.g., Rosen et al., 2016), reflections on such behaviors may be more likely to elicit feelings of guilt rather than shame.

Across all studies we used two-tailed tests to examine our hypotheses.

Data reported in this study were collected as part of a larger data-collection effort. No variables in this model overlap with variables in any other manuscript. Please refer to Appendix A for a data transparency table that outlines the additional variables we measured as a part of this data collection effort.

In our final sample, most participants were recruited from either University A (77) or University B (13). The remaining participants (17) worked at various companies in the area.

Participants in our study could earn up to $70. Completion of the initial signup survey was worth $5. From there, as this was part of a larger data collection effort, participants completed 3 surveys per day for 15 days (45 total surveys). We paid participants $1 for each of the first 25 surveys they completed and $2 for each of the next 20 surveys. As participants were paid on a per-survey basis, they could cease participating in the study at any time and still receive payment for the surveys they completed to that point. Participants were paid via an Amazon gift card based on the number of surveys completed.

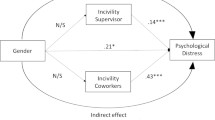

In response to an anonymous reviewer’s comment, we examined whether our findings were robust when accounting for gender. To do so, in Study 1, we first controlled for gender’s main effects on our outcomes at the between-person level, and results indicated that our hypothesized results remained consistent. We then tested a model in which we examined gender as a moderator of the relationship between enacted incivility and guilt as well as the relationship between guilt and downstream behaviors to examine whether these effects may differ based on gender. We found that gender moderated the relationship between enacted incivility and guilt (γ = 0.18, SE = 0.09, p = 0.036), such that this relationship was positive and significant for females (γ = 0.14, SE = 0.05, p = 0.002), but non-significant for males (γ = − 0.04, SE = 0.07, p = 0.528). In addition, in examining gender as a second-stage moderator of the relationship between guilt and downstream behavioral outcomes, we found that gender moderated the relationship between guilt and venting at home (γ = 0.60, SE = 0.16, p < 0.001), such that the positive relationship between guilt and venting at home was positive and significant for females (γ = 0.56, SE = 0.13, p < 0.001) but non-significant for males (γ = − 0.04, SE = 0.13, p = 0.777). However, gender did not moderate the relationship between guilt and subsequent performance at work (γ = − 0.22, SE = 0.25, p = 0.378), nor the relationship between guilt and subsequent enacted incivility at work (γ = − 0.08, SE = 0.08, p = 0.354). That said, given that this sample is skewed female (79% of the sample is female), these gender effects may be sample-specific. In fact, we did not find gender effects in our more gender balanced Studies 2a and 2b. We invite future research to examine gender as a potential moderator for the effects we find in our studies with larger and more representative samples.

Although we modelled venting as a parallel outcome to next-day performance and next-day incivility based on theoretical arguments surrounding the complex (both burdensome and reparative) nature of incivility-induced guilt (Baumeister et al., 1994), an anonymous reviewer asked whether venting may also be a sequential mediator linking feelings of guilt with reparative behaviors the next-day at work. Accordingly, we further test and discuss this possibility in Appendix B.

An anonymous reviewer asked whether perpetrators of incivility may reduce incivility the next day as a result of guilt, but then revert back to their pattern of uncivil behaviors the day after. To test for this possibility, we ran a model in which we also regressed enacted incivility from day t + 2 on guilt and incivility measured on the focal day (e.g., Wang et al., 2013). Results indicated that these reparatory effects were found to be more short-lived, as the relationship between day t guilt and day t + 2 incivility was non-significant (γ = 0.003, SE = 0.03, p = 0.924), as was the indirect effect of day t incivility on day t + 2 incivility via day t guilt (estimate = 0.000; 95% CI [− 0.0181, 0.0203]).

Five individuals stated that they had never enacted incivility at work, and an additional three provided responses that were not related to an incident in which they had enacted incivility.

We provided participants with the following examples: “e.g., you put this person down or acted condescendingly toward him/her, paid little attention to his/her statements or showed little interest in his/her opinion, and/or ignored or excluded him/her from professional camaraderie”.

Sample written responses from the incivility condition are listed in Appendix C.

We conducted a post-hoc manipulation check following the procedures outlined in Foulk et al. (2018). We randomly selected 50 responses from each condition (incivility and control) and recruited two independent coders who were unaware of the study purpose and the manipulation conditions. Raters read each response and responded to the question “To what extent is this person describing an instance in which they were uncivil, rude, or disrespectful toward someone else?” The scale ranged from 1 = “None at All” to 5 = “A Great Deal,” and results revealed good agreement between raters (ICC[1] = 0.85, ICC[2] = 0.92; LeBreton & Senter, 2008). Therefore, we aggregated their ratings to form a single variable and ran a one-way ANOVA with the study condition as the factor. These analyses showed that responses in the incivility condition were rated as being significantly more reflective of incivility than responses in the control condition (MIncivility = 3.11, SDIncivility = 1.03; Mcontrol = 1.06, SDcontrol = 0.16; F(1, 98) = 192.58, p < 0.001), suggesting that the manipulation had the intended effect.

In response to an anonymous reviewer’s comment, we additionally tested whether the target of enacted incivility may strengthen or weaken the implications for subsequent feelings of guilt. Previous research indicates that one’s hierarchical position may play an important role in the incivility process, as lateral incivility has been found to hold differing implications from top-down incivility (Caza & Cortina, 2007; Oore et al., 2010). We therefore investigated whether the hierarchical position of the target of incivility impacted the perpetrator’s subsequent feelings of guilt. Enacting incivility toward a supervisor may hold larger repercussions compared to doing so toward a coworker, while engaging in uncivil behavior toward a subordinate may also entail higher or lower levels of guilt, as such behavior may be perceived as non-leader-like or abusive given that one has more power over subordinates. Accordingly, in this study, we coded participants written responses by target type (subordinate vs. coworker vs. supervisor) and ran a one-way ANOVA in SPSS with the target type as the factor and subsequent feelings of guilt as the dependent variable. We found that there were 10 responses in which the target was a subordinate, 51 in which the target was a coworker, and 5 in which the target was a supervisor. Results indicated that there was no significant difference between the three conditions in terms of feelings of guilt (Msubordinate = 3.18, SDsubordinate = 1.16, Mcoworker = 2.78, SDcoworker = 1.05, Msupervisor = 3.65, SDsupervisor = 0.88; F(2, 63) = 1.92, p = 0.155). To provide more information, Bonferroni pairwise comparisons revealed that feelings of guilt were marginally higher when the target was a supervisor as compared to when the target was a coworker (p = 0.084), while there was no significant difference between other conditions.

As we did in Study 1, in this study we also examined whether our findings were robust when accounting for gender. We first controlled for gender in our analyses and found that our hypothesized results remained consistent. We then examined gender as a moderator of the relationship between enacted incivility and guilt, and we ran a regression analysis in which we entered the manipulation variable (1 = enacted incivility; 0 = control) and the gender variable (1 = male; 0 = female), both of which were mean centered, as well as the interaction term of these two centered variables as predictors of guilt. Results indicated that gender did not have a significant moderating effect on the relationship between enacted incivility and guilt (B = 0.10, SE = 0.31, p = 0.755).

Sample written responses from the incivility condition are listed in Appendix C.

As we did in Study 2a, we also examined whether the target of enacted incivility would differentially impact subsequent feelings of guilt. In this study, we directly asked participants to report whether the target of incivility was a subordinate, coworker, or supervisor, and similarly ran a one-way ANOVA in SPSS with the target type as the factor and subsequent feelings of guilt as the dependent variable. 18 of the responses had a subordinate as a target, 96 had a coworker as a target, and 5 had a supervisor as a target. We found that there was once again no significant difference between the three conditions (Msubordinate = 2.57, SDsubordinate = 0.90, Mcoworker = 2.51, SDcoworker = 1.18, Msupervisor = 2.75, SDsupervisor = 1.24; F(2, 116) = 0.12, p = 0.886).

Consistent with the first two studies, we also examined whether our findings were robust when considering gender. We controlled for gender in our analyses and found that our hypothesized results remained consistent. In examining gender as a moderator of the relationship between enacted incivility and guilt, we followed the same method used in Study 2a, and found that gender did not have a significant moderating effect on the relationship between enacted incivility and guilt (B = 0.20, SE = 0.23, p = 0.377).

References

Alicke, M. D., Braun, J. C., Glor, J. E., Klotz, M. L., Magee, J., Sederhoim, H., & Siegel, R. (1992). Complaining behavior in social interaction. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 18(3), 286–295. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167292183004

Amodio, D. M., Devine, P. G., & Harmon-Jones, E. (2007). A dynamic model of guilt: Implications for motivation and self-regulation in the context of prejudice. Psychological Science, 18(6), 524–530. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.2007.01933.x

Andersson, L. M., & Pearson, C. M. (1999). Tit for tat? The spiraling effect of incivility in the workplace. Academy of Management Review, 24(3), 452–471. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1999.2202131

Baer, M. D., Rodell, J. B., Dhensa-Kahlon, R. K., Colquitt, J. A., Zipay, K. P., Burgess, R., & Outlaw, R. (2018). Pacification or aggravation? The effects of talking about supervisor unfairness. Academy of Management Journal, 61(5), 1764–1788. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2016.0630

Barclay, L. J., & Skarlicki, D. P. (2009). Healing the wounds of organizational injustice: Examining the benefits of expressive writing. Journal of Applied Psychology, 94(2), 511–523. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0013451

Bastian, B., Jetten, J., & Fasoli, F. (2011). Cleansing the soul by hurting the flesh: The guilt-reducing effect of pain. Psychological Science, 22(3), 334–335. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797610397058

Baumeister, R. F., Reis, H. T., & Delespaul, P. A. E. G. (1995). Subjective and experiential correlates of guilt in daily life. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 21, 1256–1268. https://doi.org/10.1177/01461672952112002

Baumeister, R. F., Stillwell, A. M., & Heatherton, T. F. (1994). Guilt: An interpersonal approach. Psychological Bulletin, 115(2), 243–267. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.115.2.243

Beal, D. J. (2015). ESM 2.0: State of the art and future potential of experience sampling methods in organizational research. Annual Review Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 2(1), 383–407. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-032414-111335

Beal, D. J., & Ghandour, L. (2011). Stability, change, and the stability of change in daily workplace affect. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 32(4), 526–546. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.713

Behfar, K. J., Cronin, M. A., & McCarthy, K. (2020). Realizing the upside of venting: The role of the “challenger listener.” Academy of Management Discoveries, 6(4), 609–630. https://doi.org/10.5465/amd.2018.0066

Blasi, A. (1983). Moral cognition and moral action: A theoretical perspective. Developmental Review, 3(2), 178–210. https://doi.org/10.1016/0273-2297(83)90029-1

Bolino, M. C., & Grant, A. M. (2016). The bright side of being prosocial at work, and the dark side, too: A review and agenda for research on other-oriented motives, behavior, and impact in organizations. Academy of Management Annals, 10(1), 599–670. https://doi.org/10.5465/19416520.2016.1153260

Bowling, N. A., & Beehr, T. A. (2006). Workplace harassment from the victim’s perspective: A theoretical model and meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 91(5), 998–1012. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.91.5.998

Boyd, R. L., Ashokkumar, A., Seraj, S., & Pennebaker, J. W. (2022). The development and psychometric properties of LIWC-22. University of Texas at Austin.

Breugelmans, S. M., Zeelenberg, M., Gilovich, T., Huang, W.-H., & Shani, Y. (2014). Generality and cultural variation in the experience of regret. Emotion, 14(6), 1037–1048. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0038221

Brown, S. P., Westbrook, R. A., & Challagalla, G. (2005). Good cope, bad cope: Adaptive and maladaptive coping strategies following a critical negative work event. Journal of Applied Psychology, 90(4), 792–798. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.90.4.792

Bryk, A. S., & Raudenbush, S. W. (1992). Hierarchical linear models: Applications and data analysis methods. Sage Publications Inc.

Carpini, J. A., Parker, S. K., & Griffin, M. A. (2017). A look back and a leap forward: A review and synthesis of the individual work performance literature. Academy of Management Annals, 11(2), 825–885. https://doi.org/10.5465/annals.2015.0151

Caza, B. B., & Cortina, L. M. (2007). From insult to injury: Explaining the impact of incivility. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 29(4), 335–350. https://doi.org/10.1080/01973530701665108

Cohen, J., Cohen, P., West, S. G., & Aiken, L. S. (2013). Applied multiple regression/correlation analysis for the behavioral sciences. Routledge.

Cortina, L. M., Kabat-Farr, D., Magley, V. J., & Nelson, K. (2017). Researching rudeness: The past, present, and future of the science of incivility. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 22(3), 299–313. https://doi.org/10.1037/ocp0000089

Cortina, L. M., Magley, V. J., Williams, J. H., & Langhout, R. D. (2001). Incivility in the workplace: Incidence and impact. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 6(1), 64–80. https://doi.org/10.1037/1076-8998.6.1.64

Cortina, L. M., Sandy Hershcovis, M., & Clancy, K. B. H. (2022). The Embodiment of insult: A theory of biobehavioral response to workplace incivility. Journal of Management, 48(3), 738–763. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206321989798

De Dreu, C. K. W. (2006). Rational self-interest and other orientation in organizational behavior: A critical appraisal and extension of Meglino and Korsgaard (2004). Journal of Applied Psychology, 91(6), 1245–1252. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.91.6.1245

Diefendorff, J. M., & Croyle, M. H. (2008). Antecedents of emotional display rule commitment. Human Performance, 21(3), 310–332. https://doi.org/10.1080/08959280802137911

Enders, C. K., & Tofighi, D. (2007). Centering predictor variables in cross-sectional multilevel models: A new look at an old issue. Psychological Methods, 12(2), 121–138. https://doi.org/10.1037/1082-989X.12.2.121

Farley, S., Wu, D. W., Song, L. J., Pieniazek, R., & Unsworth, K. (2022). Coping with workplace incivility in hospital teams: How does team mindfulness influence prevention-and promotion-focused emotional coping? International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(23), 16209. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192316209

Flynn, F. J., & Schaumberg, R. L. (2012). When feeling bad leads to feeling good: Guilt-proneness and affective organizational commitment. Journal of Applied Psychology, 97(1), 124–133. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0024166

Foulk, T. A., Lanaj, K., Tu, M. H., Erez, A., & Archambeau, L. (2018). Heavy is the head that wears the crown: An actor-centric approach to daily psychological power, abusive leader behavior, and perceived incivility. Academy of Management Journal, 61(2), 661–684. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2015.1061

Foulk, T. A., Woolum, A., & Erez, A. (2016). Catching rudeness is like catching a cold: The contagion effects of low-intensity negative behaviors. Journal of Applied Psychology, 101(1), 50–67. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000037

Fu, S. Q., Greco, L. M., Lennard, A. C., & Dimotakis, N. (2021). Anxiety responses to the unfolding COVID-19 crisis: Patterns of change in the experience of prolonged exposure to stressors. Journal of Applied Psychology, 106(1), 48–61. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000855

Gabriel, A. S., Koopman, J., Rosen, C. C., & Johnson, R. E. (2018). Helping others or helping oneself? An episodic examination of the behavioral consequences of helping at work. Personnel Psychology, 71(1), 85–107. https://doi.org/10.1111/peps.12229

Gabriel, A. S., Lanaj, K., & Jennings, R. E. (2021). Is one the loneliest number? A within-person examination of the adaptive and maladaptive consequences of leader loneliness at work. Journal of Applied Psychology, 106(10), 1517–1538. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000838

Gabriel, A. S., Podsakoff, N. P., Beal, D. J., Scott, B. A., Sonnentag, S., Trougakos, J. P., & Butts, M. M. (2019). Experience sampling methods: A discussion of critical trends and considerations for scholarly advancement. Organizational Research Methods, 22(4), 969–1006. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428118802626

Gloor, J. L., Cooper, C. D., Bowes-Sperry, L., & Chawla, N. (2022). Risqué business? Interpersonal anxiety and humor in the #MeToo era. Journal of Applied Psychology, 107(6), 932–950. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000937

Grant, A. M. (2008). Does intrinsic motivation fuel the prosocial fire? Motivational synergy in predicting persistence, performance, and productivity. Journal of Applied Psychology, 93(1), 48–58. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.93.1.48

Grant, A. M., & Berry, J. W. (2011). The necessity of others is the mother of invention: Intrinsic and prosocial motivations, perspective taking, and creativity. Academy of Management Journal, 54(1), 73–96. https://doi.org/10.5465/AMJ.2011.59215085

Grant, A. M., & Wrzesniewski, A. (2010). I won’t let you down… or will I? Core self-evaluations, other-orientation, anticipated guilt and gratitude, and job performance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 95(1), 108–121. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0017974

Greenaway, K. H., Kalokerinos, E. K., & Williams, L. A. (2018). Context is everything (in emotion research). Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 12(6), e12393. https://doi.org/10.1111/spc3.12393

Griffin, M. A., Neal, A., & Parker, S. K. (2007). A new model of work role performance: Positive behavior in uncertain and interdependent contexts. Academy of Management Journal, 50(2), 327–347. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2007.24634438

Gross, J. J. (1998). The emerging field of emotion regulation: An integrative review. Review of General Psychology, 2(3), 271–299. https://doi.org/10.1037/1089-2680.2.3.271

Gross, J. J., & Vostroknutov, A. (2022). Why do people follow social norms? Current Opinion in Psychology, 44, 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2021.08.016

Haran, U. (2019). May the best man lose: Guilt inhibits competitive motivation. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 154, 15–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.obhdp.2019.07.003

Hülsheger, U. R., van Gils, S., & Walkowiak, A. (2021). The regulating role of mindfulness in enacted workplace incivility: An experience sampling study. Journal of Applied Psychology, 106(8), 1250–1265. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000824

Ilies, R., Keeney, J., & Scott, B. A. (2011). Work–family interpersonal capitalization: Sharing positive work events at home. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 114(2), 115–126. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.obhdp.2010.10.008

Ilies, R., Peng, A. C., Savani, K., & Dimotakis, N. (2013). Guilty and helpful: An emotion-based reparatory model of voluntary work behavior. Journal of Applied Psychology, 98(6), 1051–1059. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0034162

Ilies, R., Schwind, K. M., Wagner, D. T., Johnson, M. D., DeRue, D. S., & Ilgen, D. R. (2007). When can employees have a family life? The effects of daily workload and affect on work-family conflict and social behaviors at home. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92(5), 1368–1379. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.92.5.1368

Jennings, R. E., Lanaj, K., Koopman, J., & McNamara, G. (2022). Reflecting on one’s best possible self as a leader: Implications for professional employees at work. Personnel Psychology, 75, 69–90. https://doi.org/10.1111/peps.12447

Kim, S., Thibodeau, R., & Jorgensen, R. S. (2011). Shame, guilt, and depressive symptoms: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 137(1), 68–96. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0021466

Klass, E. T. (1978). Psychological effects of immoral actions: The experimental evidence. Psychological Bulletin, 85(4), 756–771. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.85.4.756

Koopman, J., Conway, J. M., Dimotakis, N., Tepper, B. J., Lee, Y. E., Rogelberg, S. G., & Lount, R. B., Jr. (2021). Does CWB repair negative affective states, or generate them? Examining the moderating role of trait empathy. Journal of Applied Psychology, 106(10), 1493–1516. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000837

Lanaj, K., Kim, P. H., Koopman, J., & Matta, F. K. (2018). Daily mistrust: A resource perspective and its implications for work and home. Personnel Psychology, 71(4), 545–570. https://doi.org/10.1111/peps.12268

Lang, P. J., Kozak, M. J., Miller, G. A., Levin, D. N., & McLean, A., Jr. (1980). Emotional imagery: Conceptual structure and pattern of Somato-visceral response. Psychophysiology, 17(2), 179–192. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8986.1980.tb00133.x

LeBreton, J. M., & Senter, J. L. (2008). Answers to 20 questions about interrater reliability and interrater agreement. Organizational Research Methods, 11(4), 815–852. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428106296642

Lee, Y. E., Simon, L. S., Koopman, J., Rosen, C. C., Gabriel, A. S., & Yoon, S. (2022). When, why, and for whom is receiving help actually helpful? Differential effects of receiving empowering and nonempowering help based on recipient gender. Journal of Applied Psychology, 108, 773.

Lewis, H. B. (1971). Shame and guilt in neurosis. Psychoanalytic Review, 58(3), 419–438.

Liao, H., Su, R., Ptashnik, T., & Nielsen, J. (2022). Feeling good, doing good, and getting ahead: A meta-analytic investigation of the outcomes of prosocial motivation at work. Psychological Bulletin, 148(3–4), 158–198. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000362

Liao, Z., Yam, K. C., Johnson, R. E., Liu, W., & Song, Z. (2018). Cleansing my abuse: A reparative response model of perpetrating abusive supervisor behavior. Journal of Applied Psychology, 103(9), 1039–1056. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000319

Lim, S., Ilies, R., Koopman, J., Christoforou, P., & Arvey, R. D. (2018). Emotional mechanisms linking incivility at work to aggression and withdrawal at home: An experience-sampling study. Journal of Management, 44(7), 2888–2908. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206316654544

Lin, K. J., Savani, K., & Ilies, R. (2019). Doing good, feeling good? The roles of helping motivation and citizenship pressure. Journal of Applied Psychology, 104(8), 1020–1035. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000392

Lin, S. H. J., Ma, J., & Johnson, R. E. (2016). When ethical leader behavior breaks bad: How ethical leader behavior can turn abusive via ego depletion and moral licensing. Journal of Applied Psychology, 101(6), 815–830. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000098

Lindsay-Hartz, J. (1984). Contrasting experiences of shame and guilt. American Behavioral Scientist, 27(6), 689–704. https://doi.org/10.1177/000276484027006003

Lindsay-Hartz, J., de Rivera, J., & Mascolo, M. F. (1995). Differentiating guilt and shame and their effects on motivation. In J. P. Tangney & K. W. Fischer (Eds.), Self-conscious emotions: The psychology of shame, guilt, embarrassment, and pride (pp. 274–300). Guilford Press.

Lively, K. J., & Powell, B. (2006). Emotional expression at work and at home: Domain, status, or individual characteristics? Social Psychology Quarterly, 69(1), 17–38. https://doi.org/10.1177/019027250606900103

MacKinnon, A., Jorm, A. F., Christensen, H., Korten, A. E., Jacomb, P. A., & Rodgers, B. (1999). A short form of the positive and negative affect schedule: Evaluation of factorial validity and invariance across demographic variables in a community sample. Personality and Individual Differences, 27(3), 405–416. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0191-8869(98)00251-7

Marschall, D., Sanftner, J., & Tangney, J. P. (1994). The state shame and guilt scale. George Mason University.

Matthews, M., Webb, T. L., Shafir, R., Snow, M., & Sheppes, G. (2021). Identifying the determinants of emotion regulation choice: A systematic review with meta-analysis. Cognition and Emotion, 35(6), 1056–1084. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699931.2021.1945538

McClean, S. T., Courtright, S. H., Yim, J., & Smith, T. A. (2021). Making nice or faking nice? Exploring supervisors’ two-faced response to their past abusive behavior. Personnel Psychology, 74(4), 693–719. https://doi.org/10.1111/peps.12424

McGraw, K. M. (1987). Guilt following transgression: An attribution of responsibility approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 53(2), 247–256. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.53.2.247

Meier, L. L., & Gross, S. (2015). Episodes of incivility between subordinates and supervisors: Examining the role of self-control and time with an interaction-record diary study. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 36(8), 1096–1113. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.2013

Mitchell, M. S., Vogel, R. M., & Folger, R. (2015). Third parties’ reactions to the abusive supervision of coworkers. Journal of Applied Psychology, 100(4), 1040–1055. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000002

Moran, C. M., Diefendorff, J. M., & Greguras, G. J. (2013). Understanding emotional display rules at work and outside of work: The effects of country and gender. Motivation and Emotion, 37(2), 323–334. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-012-9301-x

Moskowitz, D. S., & Coté, S. (1995). Do interpersonal traits predict affect? A comparison of three models. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 69(5), 915–924. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.69.5.915

Murphy, P. R., & Jackson, S. E. (1999). Managing work role performance: Challenges for twenty-first century organizations and their employees. The changing nature of performance: Implications for staffing, motivation and development. DR Ilgen et DP Pulakos, dir (pp. 325–365). Jossey-Bass.

Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. O. (1998). Mplus user’s guide. Muthén & Muthén.

Oore, G. D., Leblanc, D., Day, A., Leiter, M. P., Spence Laschinger, H. K., Price, S. L., & Latimer, M. (2010). When respect deteriorates: Incivility as a moderator of the stressor–strain relationship among hospital workers. Journal of Nursing Management, 18(8), 878–888. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2834.2010.01139.x

Park, L. S., & Martinez, L. R. (2022). An “I” for an “I”: A systematic review and meta-analysis of instigated and reciprocal incivility. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 27(1), 7–21. https://doi.org/10.1037/ocp0000293

Parlamis, J. D. (2012). Venting as emotion regulation: The influence of venting responses and respondent identity on anger and emotional tone. International Journal of Conflict Management, 23(1), 77–96. https://doi.org/10.1108/10444061211199322

Pearson, C. M., Andersson, L. M., & Porath, C. L. (2005). Workplace incivility. In S. Fox & P. E. Spector (Eds.), Counterproductive work behavior: Investigations of actors and targets (pp. 177–200). American Psychological Association.

Pearson, C. M., Andersson, L. M., & Wegner, J. W. (2001). When workers flout convention: A study of workplace incivility. Human Relations, 54(11), 1387–1419. https://doi.org/10.1177/00187267015411001

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–903. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879

Porath, C. L., & Erez, A. (2009). Overlooked but not untouched: How rudeness reduces onlookers’ performance on routine and creative tasks. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 109(1), 29–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.obhdp.2009.01.003

Porath, C. L., & Pearson, C. M. (2012). Emotional and behavioral responses to workplace incivility and the impact of hierarchical status. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 42, E326–E357. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.2012.01020.x

Porath, C. L., & Pearson, C. M. (2013). The price of incivility. Harvard Business Review, 91(1–2), 114–121.

Preacher, K. J., Curran, P. J., & Bauer, D. J. (2006). Computational tools for probing interactions in multiple linear regression, multilevel modeling, and latent curve analysis. Journal of Educational and Behavioral Statistics, 31(4), 437–448. https://doi.org/10.3102/10769986031004437

Preacher, K. J., Zyphur, M. J., & Zhang, Z. (2010). A general multilevel SEM framework for assessing multilevel mediation. Psychological Methods, 15(3), 209–233. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0020141

Rimé, B., Philippot, P., Boca, S., & Mesquita, B. (1992). Long-lasting cognitive and social consequences of emotion: Social sharing and rumination. European Review of Social Psychology, 3(1), 225–258. https://doi.org/10.1080/14792779243000078

Robinson, M. D., & Clore, G. L. (2001). Simulation, scenarios, and emotional appraisal: Testing the convergence of real and imagined reactions to emotional stimuli. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 27(11), 1520–1532. https://doi.org/10.1177/01461672012711012

Rosen, C. C., Dimotakis, N., Cole, M. S., Taylor, S. G., Simon, L. S., Smith, T. A., & Reina, C. S. (2020). When challenges hinder: An investigation of when and how challenge stressors impact employee outcomes. Journal of Applied Psychology, 105(10), 1181–1206. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000483

Rosen, C. C., Gabriel, A. S., Lee, H. W., Koopman, J., & Johnson, R. E. (2021). When lending an ear turns into mistreatment: An episodic examination of leader mistreatment in response to venting at work. Personnel Psychology, 74(1), 175–195. https://doi.org/10.1111/peps.12418

Rosen, C. C., Koopman, J., Gabriel, A. S., & Johnson, R. E. (2016). Who strikes back? A daily investigation of when and why incivility begets incivility. Journal of Applied Psychology, 101(11), 1620–1634. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000140

Satorra, A., & Bentler, P. M. (2001). A scaled difference chi-square test statistic for moment structure analysis. Psychometrika, 66(4), 507–514. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02296192

Schilpzand, P., De Pater, I. E., & Erez, A. (2016). Workplace incivility: A review of the literature and agenda for future research. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 37, S57–S88. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.1976

Schmader, T., & Lickel, B. (2006). The approach and avoidance function of guilt and shame emotions: Comparing reactions to self-caused and other-caused wrongdoing. Motivation and Emotion, 30(1), 42–55. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-006-9006-0

Scott, B. A., & Barnes, C. M. (2011). A multilevel field investigation of emotional labor, affect, work withdrawal, and gender. Academy of Management Journal, 54(1), 116–136. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2011.59215086

Scott, B. A., Colquitt, J. A., Paddock, E. L., & Judge, T. A. (2010). A daily investigation of the role of manager empathy on employee well-being. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 113(2), 127–140. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.obhdp.2010.08.001

Scott, K. L., Restubog, S. L. D., & Zagenczyk, T. J. (2013). A social exchange-based model of the antecedents of workplace exclusion. Journal of Applied Psychology, 98(1), 37–48. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0030135

Sheehy, K., Noureen, A., Khaliq, A., Dhingra, K., Husain, N., Pontin, E. E., Cawley, R., & Taylor, P. J. (2019). An examination of the relationship between shame, guilt and self-harm: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 73, 101779. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2019.101779

Smart, T. (2024). Remote work has radically changed the economy—and it’s here to stay. US News. https://www.usnews.com/news/economy/articles/2024-01-25/remote-work-has-radically-changed-the-economy-and-its-here-to-stay. Retrieved 25 January 2024

Song, Y., Liu, Y., Wang, M., Lanaj, K., Johnson, R. E., & Shi, J. (2018). A social mindfulness approach to understanding experienced customer mistreatment: A within-person field experiment. Academy of Management Journal, 61(3), 994–1020. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2016.0448

Spector, P. E., & Fox, S. (2002). An emotion-centered model of voluntary work behavior: Some parallels between counterproductive work behavior and organizational citizenship behavior. Human Resource Management Review, 12(2), 269–292. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1053-4822(02)00049-9

Su, S., Taylor, S. G., & Jex, S. M. (2022). Change of heart, change of mind, or change of willpower? Explaining the dynamic relationship between experienced and perpetrated incivility change. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 27(1), 22–36. https://doi.org/10.1037/ocp0000299

Tangney, J. P. (1991). Moral affect: The good, the bad, and the ugly. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 61(4), 598–607. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.61.4.598

Tangney, J. P., & Dearing, R. L. (2003). Shame and guilt. Guilford Press.

Tangney, J. P., Stuewig, J., & Mashek, D. J. (2007). Moral emotions and moral behavior. Annual Review of Psychology, 58, 345–372. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.56.091103.070145

Tangney, J. P., Wagner, P. E., Hill-Barlow, D., Marschall, D. E., & Gramzow, R. (1996). Relation of shame and guilt to constructive versus destructive responses to anger across the lifespan. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 70(4), 797–809. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.70.4.797

Taylor, S. G., Locklear, L. R., Kluemper, D. H., & Lu, X. (2022). Beyond targets and instigators: Examining workplace incivility in dyads and the moderating role of perceived incivility norms. Journal of Applied Psychology, 107(8), 1288–1302. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000910

Ten Brummelhuis, L. L., & Bakker, A. B. (2012). A resource perspective on the work–home interface: The work–home resources model. American Psychologist, 67(7), 545–556. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0027974

Tepper, B. J., Dimotakis, N., Lambert, L. S., Koopman, J., Matta, F. K., Man Park, H., & Goo, W. (2018). Examining follower responses to transformational leadership from a dynamic, person–environment fit perspective. Academy of Management Journal, 61(4), 1343–1368. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2014.0163

Tice, D. M., & Bratslavsky, E. (2000). Giving in to feel good: The place of emotion regulation in the context of general self-control. Psychological Inquiry, 11(3), 149–159. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327965PLI1103_03

Tignor, S. M., & Colvin, C. R. (2019). The meaning of guilt: Reconciling the past to inform the future. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 116(6), 989–1010. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspp0000216

Tracy, J. L., Robins, R. W., & Tangney, J. P. (2007). The self-conscious emotions: Theory and research. Guilford Press.

Tremmel, S., & Sonnentag, S. (2018). A sorrow halved? A daily diary study on talking about experienced workplace incivility and next-morning negative affect. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 23(4), 568–583. https://doi.org/10.1037/ocp0000100

Van Jaarsveld, D. D., Walker, D. D., & Skarlicki, D. P. (2010). The role of job demands and emotional exhaustion in the relationship between customer and employee incivility. Journal of Management, 36(6), 1486–1504. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206310368998

Van Kleef, G. A., Gelfand, M. J., & Jetten, J. (2019). The dynamic nature of social norms: New perspectives on norm development, impact, violation, and enforcement. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 84, 103814. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2019.05.002

Van Kleef, G. A., Wanders, F., Stamkou, E., & Homan, A. C. (2015). The social dynamics of breaking the rules: Antecedents and consequences of norm-violating behavior. Current Opinion in Psychology, 6, 25–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2015.03.013

Volkema, R. J., Farquhar, K., & Bergmann, T. J. (1996). Third-party sensemaking in interpersonal conflicts at work: A theoretical framework. Human Relations, 49(11), 1437–1454. https://doi.org/10.1177/001872679604901104

Wang, M., Liu, S., Liao, H., Gong, Y., Kammeyer-Mueller, J., & Shi, J. (2013). Can’t get it out of my mind: Employee rumination after customer mistreatment and negative mood in the next morning. Journal of Applied Psychology, 98(6), 989–1004. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0033656

Weiss, H. M., & Cropanzano, R. (1996). Affective events theory: A theoretical discussion of the structure, causes and consequences of affective experiences at work. In B. M. Staw & L. L. Cummings (Eds.), Research in organizational behavior: An annual series of analytical essays and critical reviews (pp. 1–74). Elsevier Science/JAI Press.

Wharton, A. S., & Erickson, R. I. (1993). Managing emotions on the job and at home: Understanding the consequences of multiple emotional roles. Academy of Management Review, 18(3), 457–486. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1993.9309035147

Whetten, D. A. (1989). What constitutes a theoretical contribution? Academy of Management Review, 14(4), 490–495. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1989.4308371

Wicker, F. W., Payne, G. C., & Morgan, R. D. (1983). Participant descriptions of guilt and shame. Motivation and Emotion, 7(1), 25–39. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00992963

Williams, L. J., & Anderson, S. E. (1991). Job satisfaction and organizational commitment as predictors of organizational citizenship and in-role behaviors. Journal of Management, 17, 601–617. https://doi.org/10.1177/014920639101700305

Woolum, A., Foulk, T., & Erez, A. (2024). A review of the short-term implications of discrete, episodic incivility. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 18(1), e12918. https://doi.org/10.1111/spc3.12918

Yao, J., Lim, S., Guo, C. Y., Ou, A. Y., & Ng, J. W. X. (2022). Experienced incivility in the workplace: A meta-analytical review of its construct validity and nomological network. Journal of Applied Psychology, 107(2), 193–220. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000870

Yuan, Z., Barnes, C. M., & Li, Y. (2018). Bad behavior keeps you up at night: Counterproductive work behaviors and insomnia. Journal of Applied Psychology, 103(4), 383–398. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000268

Zhong, R., & Robinson, S. L. (2021). What happens to bad actors in organizations? A review of actor-centric outcomes of negative behavior. Journal of Management, 47(6), 1430–1467. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206320976808

Funding

No funding was received for conducting this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors have no competing interests to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

Ethical Approval

This study was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Study 1 was approved by the University of Florida Institutional Review Board (202002477). Study 2 was approved by University of Cincinnati Institutional Review Board (2016–0563).

Consent to Participate

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix A: Data Transparency Table

Variables in the dataset | This MS (Study 2) | Other MS (Study 1) |

|---|---|---|

(STATUS = current) | (STATUS = in-press) | |

Other orientation | X | |

Self-concern | C | |

Political correctness | X | |

Cognitive resource depletion | X | |

Negative affect | C (Supplemental) | |

Moral licensing | C (Supplemental) | |

Angry marital behavior (spouse rated) | X | |

Withdrawn marital behavior (spouse rated) | X | |

Positive base support (spouse rated) | Supplemental | |

Negative base support (spouse rated) | Supplemental | |

Spousal support (spouse rated) | Supplemental | |

Extraversion | Supplemental | |

Enacted incivility | X | |

Guilt | X | |

Shame | C | |

Performance | X | |

Venting | X | |

Prosocial motivation | X | |

Positive affect | C | |

Negative affect | C |

Appendix B: Supplemental Analyses

It is possible that venting may act as a mediator between incivility-induced guilt and next-day task performance and incivility. We did not hypothesize venting as a mediator because we felt that our theoretical paradigm made clearer predictions about venting as an outcome rather than as a mediator of guilt. That is, research on guilt proposes simultaneous burdensome as well as reparative effects for guilt (Baumeister et al., 1994), but does not speak to mediating links between guilt and subsequent reparative behaviors. Indeed, most empirical research on guilt identifies direct relationships between guilt and subsequent reparative effects (Baumeister et al., 1995; Liao et al., 2018), and thus we make similar arguments based on theory.

In addition, the literature on venting is divided, with some arguing that venting may be helpful in diffusing emotions and allowing individuals to deal with their emotions more effectively (Barclay & Skarlicki, 2009; Behfar et al., 2020; Volkema et al., 1996), and others arguing that venting may actually aggravate negative emotions and result in maladaptive behaviors (Baer et al., 2018; Rosen et al., 2021). Accordingly, it is unclear if and how venting may mediate the effects of incivility-induced guilt on subsequent reparative behaviors. For these reasons, we felt that theory is much clearer in positioning venting as an outcome of incivility-induced guilt rather than as a mediator. However, we ran exploratory supplementary analyses by adding venting as a mediator to our full model in Study 1 (our experience sampling study), and we provide the results below (Table 8 shows results of multilevel path analyses and Table 9 summarizes results of indirect and conditional indirect effects). We modeled the path from enacted incivility to guilt as a free slope because we test the cross-level moderation effect of prosocial motivation on this path, and to allow for model convergence, we modeled all other paths as fixed slopes (Beal, 2015). All of our hypothesized effects remain unchanged when modeling venting as a mediator.

In these analyses, we found that venting was positively related to job performance the next day (γ = 0.06, SE = 0.03, p = 0.020), and there was a positive and significant indirect effect of enacted incivility (day t) on employees’ next-day job performance (day t + 1) via increased feelings of guilt (day t) and venting (day t) (estimate = 0.002; 95% CI [0.0003, 0.0069]). At the same time, we found that venting was positively associated with enacted incivility the next day (γ = 0.04, SE = 0.02, p = 0.010), and there was a positive and significant indirect effect of enacted incivility (day t) on employees’ next-day enacted incivility (day t + 1) via increased feelings of guilt (day t) and venting (day t) (estimate = 0.002; 95% CI [0.0003, 0.0049]).

These mixed findings reflect the current state of the literature on venting, which has suggested that venting may be helpful as well as harmful to individuals’ subsequent reactions (Baer et al., 2018; Rosen et al., 2021). It would be interesting for future research to explore when cathartic acts such as venting may help or hurt (e.g., Koopman et al., 2021), as well as whether there are differing implications for task-based versus interpersonal outcomes of venting, as we find in these supplementary analyses (increased performance as well as heightened subsequent incivility). Relatedly, future research may also consider examining how focal employees and their spouses subsequently deal with such venting behaviors in the home domain, which may hold implications for their subsequent behaviors at work the next day.

Appendix C: Sample Written Responses for Enacted Incivility conditons

Study # | Sample responses | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Example 1 | Example 2 | Example 3 | Example 4 | Example 5 | |

Study 2a | “Before the quarantine, one of my coworkers had caught me on an especially bad day. I had deadlines coming up, had very little sleep, and was overall just rather stressed. I wanted some peace and quiet while doing my work so I could work more efficiently. During lunch, which I spent doing more work, he came up to me and tried to start a conversation, not at all disrespectfully. I respectfully told him that I couldn’t talk right now but he kept going so I ended up raising my voice at him which I felt awful about afterwards.” | “When Jen walked into the room (our workplace/office) I ignored her, and she made some kind of funny quip about why she was late to work to me, but I ignored that as well, since she was lying. Our other coworkers noticed me ignore her, as usually I was the only friendly person towards her, but they also were ignoring her. Then when she asked me questions about employees, clearly just to get me to talk to her, I gave her the bare minimum of an acceptable response. She commented, ‘well, nobody seems to be in a good mood this morning.’” | “I was annoyed with my coworker who was fairly new yet not listening to me, a senior staff member. I pointed out the way she was copying information into the spreadsheet was inefficient and not how we’re supposed to do it. I was impatient since I’d already mentioned it before, so I wasn’t very nice in asking her to do it correctly. She also brushed me off rather than accepting that I knew the better way to do it from my experience.” | “I was getting very annoyed with a colleague who would not stop asking me for help. At first, I didn’t mind it, but he didn’t seem to be able to do anything on his own and just wanted me to do it for him. It got to the point where anytime he would talk to me, I would tense up. I started trying to respond to his questions and statements as little as possible and not offer help or feedback. When I saw him at work, I generally tried not to make eye contact and ignored him.” | “Lee is someone that I do not particularly get along with. Our personalities clash and I do my best to spend as little time as possible with him. One day, a bunch of us were talking about food, and he said something that two of us thought inaccurate. In sync, we both corrected him. He then proceeded to "well actually" us in a way that was very annoying. I ignored him the rest of the day, even when he was asking for help.” |

Study 2b | “My immediate coworker asked me for help with her PC. She is a sweet, kind person. I like her very much. I was in a terrible mood and had just started taking a medication that was making me feel angry. I responded by snapping at my coworker and implying that she was stupid. I felt terrible but I never apologized.” | “One day about a week ago I was having a pretty frustrating day. I think clients were being demanding and rude, and I was tired. One of my coworkers kept making mistakes that I had to correct. It was so annoying and I was short with her even though I know she is sensitive to criticism. I just could not figure out why she was doing such a bad job and I didn’t have the energy to hide my annoyance.” | “Recently, I had a heated disagreement with a coworker during a team meeting. I was feeling overwhelmed with my workload and my colleague made a suggestion that I perceived as criticism. I responded with a harsh tone and dismissive attitude towards their idea. After I realized that my actions were rude, uncivil and disrespectful attitude.” | “Recently, I encountered a coworker that was working really, really slowly. I became a little bit impatient and I yelled at him. It wasn’t personal, but I really had a lot of stress due to work. I regretted it right after and I apologized.” | “When I was annoyed with a coworker because she wouldn’t help me with a project I ignored her when she tried to talk to me. She kept trying to tell me that she was very busy and could not help me. My other coworkers tried to get me to talk to her but I refused and told them I was right to ask her to help me. I was a little bit rude to her and felt bad the next day because she really was busy.” |

Appendix D: LIWC-22 Analyses for Written Manipulations

To further examine the efficacy of the written manipulations used in Studies 2a and 2b, we utilized the linguistic inquiry and word count (LIWC-22) software (Boyd et al., 2022) and conducted an exploratory investigation to see whether there were differences in the language used by our participants in the two conditions (incivility and control). LIWC-22 uses validated dictionaries to evaluate the tones and themes in a given text, and it provides an objective way to analyze participants’ written responses. Although there is no dictionary in the LIWC-22 software that directly assesses whether a given text reflects instances of incivility, the literature depicts enacted incivility as a generally negative experiences that consist of negative behaviors and emotions (Cortina et al., 2017; Schilpzand et al., 2016). For this reason, we analyzed the degree to which the written responses in Studies 2a and 2b (a) adopted a negative tone and (b) expressed negative emotions. Similarly, acting with incivility suggests that one may have overlooked a desire to affiliate to the target during the event (e.g., Cortina et al., 2022), and therefore, we also looked at whether participants’ depictions of incivility (vs. control) reflected reduced affiliation.

To test these possibilities, we ran several one-way ANOVAs with the manipulation condition as the factor and the respective categories (negative tone, negative emotions, and affiliation) as the dependent variables. The results indicated that responses in the incivility condition adopted a more negative tone than responses in the control condition for both Study 2a (MIncivility = 3.45, SDIncivility = 2.70; Mcontrol = 1.21, SDcontrol = 1.84; F(1, 137) = 33.17, p < 0.001) as well as Study 2b (MIncivility = 3.18, SDIncivility = 2.56; Mcontrol = 0.78, SDcontrol = 1.43; F(1, 263) = 92.06, p < 0.001). Similarly, responses in the incivility condition reflected more negative emotions than responses in the control condition for both Study 2a (MIncivility = 1.92, SDIncivility = 1.94; Mcontrol = 0.56, SDcontrol = 1.16; F(1, 137) = 25.82, p < 0.001) as well as Study 2b (MIncivility = 1.66, SDIncivility = 1.55; Mcontrol = 0.38, SDcontrol = 0.81; F(1, 263) = 74.39, p < 0.001). In addition, responses in the incivility condition reflected reduced affiliation compared to the control condition (Study 2a: MIncivility = 2.58, SDIncivility = 2.29; Mcontrol = 5.59, SDcontrol = 3.72; F(1, 137) = 32.28, p < 0.001; Study 2b: MIncivility = 2.89, SDIncivility = 2.48; Mcontrol = 7.21, SDcontrol = 4.35; F(1, 263) = 92.37, p < 0.001). Put together, and in line with the additional manipulation checks that we conducted, these exploratory results provide support that the incivility manipulation worked in the way that we had expected.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Kim, D., Lanaj, K. & Koopman, J. Incivility Affects Actors Too: The Complex Effects of Incivility on Perpetrators’ Work and Home Behaviors. J Bus Ethics (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-024-05714-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-024-05714-y