Abstract

In this article, we seek to explore the different normative claims made around commons organizing and how the advent of the digital commons introduces new ethical questions. We do so by unpacking and categorizing the specific ethical dimensions that differentiate the commons from other forms of organizing and by discussing them in the light of debates around the governance of participative organizations, the cornerstone of commons organizing (Ostrom in Governing the commons: the evolution of institutions for collective action. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1990). Rather than contesting commons organizing or endorsing it blindly, our goal is to critically reflect on its deontological and instrumental assumptions, and analyze the arguments upholding that it possesses ethical qualities that render it fairer, more equitable and sustainable than other centralized or hierarchical models—as well as any forms of privatization. We conclude by assessing the definitional dislocation of the digital commons where, unlike traditional commons, extractability can be endless and generate unintended consequences such as commodification or alienation. Taking stock of recent debates around the digital commons, we open the debate for future possible research avenues on normative claims, particularly under rapidly changing technological conditions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The commons as a way of organizing have received increasing attention from management scholars (Hartman, 1994; King, 1995; Fuchs, 2020; Barnett & King, 2008; O’Mahony, 2003; Fournier, 2013). Three reasons could explain this. First and foremost is the decision to award the Economics Nobel Prize in 2009 to Elinor Ostrom, which immediately put the topic firmly within mainstream scholarship. According to De Angelis and Harvie (2014), the shift signalled by this award was as significant as that of Hayek’s in 1974, which symbolized the move from Keynesian to neoliberal policies. The second reason is the severe multi-faceted ecological crisis that has been intensifying since the 1960s. Commons organizing is posited as an example of sustainability and resilience, particularly amid global warming, depletion of natural resources and biodiversity loss in the new era of the Anthropocene. Thirdly, the emergence of the digital commons has expanded the paradigm of commons organizing (Fuchs, 2020; Nagle, 2018), opening the meaning of the concept to new possibilities and, as we will discuss, new ethical and socio-political dilemmas.

Ethical issues are explicit in the very definitions of the commons and commons organizing. For example, the commons has been defined as ‘a resource shared by a group where the resource is vulnerable to enclosure, overuse and social dilemmas’ (Hess, 2008, p. 37); and commons organizing ‘as the processes by which communities of people work in common experimenting with new organizational designs that promote common goods production, distribution, governance and ownership in the pursuit of the common good’ (Albareda & Sison, 2020, p. 778). Another view sees commons organizing as common pool resources (CPRs) intertwined with a community and with the rules and norms for managing them (Bollier, 2014). In other words, the commons become a distinctive way of organizing when a community takes care of managing a resource in a participative and sustainable way, as it has been traditionally applied to the management of forests, pastures, canals, irrigation systems, fisheries, mills, and bridges. In the literature, it is not unusual to find implicit or explicit claims that commons organizing is preferable or normatively superior to others, at least in certain circumstances. Yet, despite recent interest in the normative underpinnings of commons organizing (Albareda & Sison, 2020; Peredo et al., 2020), the literature on business ethics and organizational studies has not yet fully analysed and categorized the ethical claims, concerns, or challenges associated with them, nor shown how they would apply to the digital commons or what new issues these bring about. In this paper, we specify and organize the often-implicit ethical claims and concerns we have found scattered in the commons literature to offer a first attempt of categorization. Our goal is neither to question nor to endorse uncritically this alternative form of organizing, but to unpack the normative language used by scholars and practitioners when they talk about its benefits, to offer a more nuanced reflection, and advance the discussion beyond indiscriminate enthusiasm or blatant rejection.

In what follows, rather than trying to apply a pre-established ethical framework on the commons, we start with what authors have claimed about this form of organizing, this is, its advantages and limitations from multiple perspectives. Implicitly or explicitly, such claims involve different ideals, normative concerns, assumptions, or challenges. We claim that they can be subsumed under more general discussions on the normative aspects of the governance of participative organizations (Collier, 1998; Collier & Esteban, 1999) which, we argue, remain at the heart of commons organizing (De Angelis & Harvie, 2014; Ostrom, 1990). Thus, in this article, after reviewing how the commons are defined and used in the management literature, we put forward a categorization of ethical claims and concerns in and around the commons that include debates around exclusion, subtraction, type of usage, polycentricity and subsidiarity, engagement, community building, moral virtues, and environmental stewardship. As we will show, such normative debates correspond to similar ones around governance: (i) governance as a mechanism for coordination, control, and regulation; and (b) governance as a form of organizing participation within a firm or organization. Hence, in this article, we reveal how when discussing the ethical claims of commons organizing, normativity, and governance become necessarily interconnected.

In addition, since the discussion on the commons has expanded beyond the traditional ‘big five’ topics—forests, fisheries, irrigation, water, and rangeland (Van Laerhoven et al., 2020)—we explore the new types of ethical debates that have emerged in the digital setting. These debates can be divided into three issues: new forms of alienation, new forms of commodification, and anonymous engagement. When we take the traditional and the digital commons together, we can enrich the discussions posed by the commons way of organizing as it presents itself both as an alternative to mainstream capitalism and to statism. Furthermore, we claim that in both cases the central element becomes participation in the resources’ governance. Thus, in this article, we articulate the existing ethical debates around the different claims made upon governance as a form of coordination, control, and regulation, on one side, and participation, on the other. As we do this, we also identify new avenues for future research, with special emphasis on the future of the commons in an increasingly digitalized world, as well as their role as a reference for sustainability and resilience in a challenged ecosystem.

The Commons: A Fuzzy Term

In the canonical literature, CPRs refer to natural resources such as lakes, rivers, or pastures (Hardin, 1968; Lloyd, 1833; Olson, 1965) that are large enough that excluding someone from their use is costly, but limited enough that subtraction from them affects other users. Even though these commons are available for exploitation, usually they cannot be acquired as a whole. Yet, their availability makes it possible for them to be ‘subtractable’ in a way that may leave the CPRs decimated or even exhausted. The commoners, who either create or administrate the commons, do not privately own them. This has led to using the concept of ‘commons’ often as a blanket term for anything not private or anything that can be accessed openly. As noted by Peredo et al. (2020), this confusion is one of the main difficulties affecting the literature on the commons. Digitalization and the internet have added complexity to the definitional conundrum, moving it away from natural resources. In this regard, the CPRs may include things like language, music, and software, bundled together with people around the framework that organizes ‘how the common resources should be created, shared, maintained and developed further’ (Wittel, 2013, p. 320).

Since natural CPRs are vulnerable to overuse and can lead to social dilemmas between short-term personal interests and the long-term general interest, Peredo and colleagues warn that ethical issues are ‘built into’ the organizing of the commons (Peredo et al., 2020, p. 664). It is this ‘commons organizing’ and not the CPRs themselves that constitute the focus of this article, following what is by now the most widely used definition of the commons: a system of organization, including a governance regime and a community management, that applies to resources to ensure their long-term sustainability (McGinnis, 2019; Frischmann et al., 2014). As Bollier puts it, ‘commons = a resource + a community + a set of social protocols’ (Bollier, 2014, p. 15). Thus, rather than being an essential attribute of natural or human-made objects and systems, the commons are a socially constructed way to frame organizing; often with contested boundaries (Ansari et al., 2013).

Even though it may be too broad of a concept, the commons are as broad as other often-used concepts in the social sciences, such as democracy or capitalism. A point could be made that, in fact, this broadness or fuzziness is a reflection of the healthy diversity of the commons and the ways in which they are managed. In a highly cited article, Hess (2008) expands the concept to a myriad of new sectors and circumstances that encapsulate the so-called ‘new commons’ which include global finance stability, neighbourhood commons, knowledge, libraries, or security amongst others. This is a turn that further increases the normative debates made in and around commons organizing but that, as we will argue, present specific challenges in the more specific literature made around the digital commons.

Premises, Features and Debates in the Commons Literature

One of the main criticisms levelled against Hardin’s, 1968 classic essay ‘The Tragedy of the Commons’ is the lack of distinction among different kinds of commons (Peredo et al., 2020) and different types of property regimes beyond private property (Peredo et al., 2018); hence, its incapacity to find hope in the places Elinor Ostrom did—by studying multiple examples of self-governing institutions that succeeded in sharing and preserving local CPRs from resource degradation. It is true that these institutions have not always been able to fully solve the commons’ challenges; yet ‘neither have Hardin’s preferred alternatives of private or state ownership’ (Dietz et al., 2003, p. 1907). The systems of self-governance studied by Ostrom and colleagues can be ‘suboptimal in the short run but prove wiser in the long run’ (Dietz et al., 2003, p. 1909) because they can adapt to complexity and allow for change. Hence, they are more resilient. Such complexity and uncertainty are due to the interaction between ecological and social systems, but can be managed better by addressing local problems applying the subsidiarity principle (Van Laerhoven & Ostrom, 2007), rather than through centralization, either public or private.

One of the reasons the outcome of commons organizing is tragic for Hardin is that his model, like Olson’s (1965) logic of collective action, assumes people to be self-interested and opportunistic maximisers of short-term goals. The same assumptions are used by traditional advocates of enclosure and, more recently, by neoliberal proponents to turn commons into private property, dismissing the commoners’ capacity to communicate and establish rules that can prevent the destruction of CPRs (Wittel, 2013). As De Angelis and Harvie (2014) point out, Ostrom (1990) criticized Hardin for mistaking an open access system with the ‘commons’ and applying a simple version of the prisoner’s dilemma logic, in which completely rational individuals decide not to cooperate even if it is in their best interest to do so.

According to the eight principles explained by Ostrom in her 1990 book Governing the Commons rationality and self-interest do not necessarily have to lead to tragedy, especially if there is effective communication and adaptability. Communication and cooperation are based on trust and reciprocity (Ostrom, 2003), and trust is built on reputation, which is distilled from past actions. Behind this perspective, we find a different model of collective action and accountability that is neither the ‘panacea’ of the market nor of the Leviathan state.

Nonetheless, according to some, the tragic narrative and its ethical implications might still be valid for large-scale commons, ‘given the rate of deterioration and replenishment of these large-scale commons and the rate at which competing interest groups have been unable to device effective and robust governance mechanisms to solve wicked collective action problems associated with them’ (Araral, 2014, p. 17). The semantics of the ‘commons’ are key here: Are these large-scale natural resources (the atmosphere, biodiversity, etc.) CPRs or open access? Can one use Ostrom’s influential design principles to redefine open access resources as CPRs, so that they are administered in a way that would last over time and is preferable for both nature and society? It is true that since Hardin’s article (1968) global communication and surveillance systems have improved substantially (both in the analogic and digital world), along with the sense of global vulnerability and interdependence. The answers to these questions need to escape essentialist accounts about the possibility or impossibility of applying the notion of commons to large-scale ecosystems and transnational CPRs (Ansari et al., 2013). It is up to the different actors involved in the issue to try to persuade others, make agreements, and devise mechanisms to manage resources in a sustainable way.

Commons in Organization and Management Studies

Turning specifically to business ethics and organization studies, multiple authors have discussed the benefits of commons organizing as a way of preserving resources and making them accessible to people in a more just way. The applications of the commons framework to the management literature have varied so widely that it has included, for instance, industry reputation, understood as a kind of common resource that is a shared and mutually constructed value (Barnett & King, 2008). According to Barnett and King’s study, error or wrongdoing at firm level may negatively affect other firms in the same industry, but the creation of a self-regulatory institution can help reduce the magnitude of the harm for the whole. This analysis is aligned with Ostrom’s views because it shows how actors can self-regulate to avoid the destruction of a commons, in this case an intangible good such as reputation. This idea of reputation as a common good may not only apply to industries, but to professions as well.

Similarly, Hartman (1994) claims that an organization is in itself a commons, and that this way of understanding it is ostensibly better ‘than a snake-pit where only a fool or a martyr would act otherwise than on narrow self-interest’ (Hartman, 1994, p. 261). In an organization, a person’s contribution only pays off if other people also contribute; but it is difficult to enforce contribution, and a system of rewards and punishments might not be sufficient or the best way to avoid free riding (Hartman, 1994). Therefore, according to this view, a corporate culture that incentivizes loyalty and contribution is necessary in order to maintain the organization, metaphorically, as a commons.

In the critical management literature, a crucial normative concern is the commodification of CPRs formerly administered at a communal level. It could be said that commodification is always looming over the shared resources, be it in a global or a local scale. This echoes Polanyi’s (2001) perception that capitalism depends on the continuous enclosure and privatization of CPRs, a questionable practice that, with time, becomes uncritically accepted. To this, Peredo et al. (2020) add that: ‘Enclosure commodifies resources, turning them into commodities with exchange-value and the loss of use-value and is a means by which communities are dispossessed of common-pool resources’ (Peredo et al., 2020, p. 666). Fournier (2013) makes a similar argument giving further examples: neoliberalism has expanded enclosure to areas such as publicly funded medical knowledge or DNA of plants, animals, and humans. For example, pharmaceutical companies can collect information from native tribes, patent it, and then sell the new medicine, even to the natives they took it from. In other words, ‘[a] great deal of capitalist production therefore relies on material and immaterial wealth created in common, but which is then appropriated as the private property of capitalists’ (Fournier, 2013, p. 438). This critique claims that the preservation of the commons requires ‘commoning’ as a way of organizing. Now, this way of organizing is not seen merely as a means to protect the commons, but it is also seen as an intrinsic good. Thus, under this perspective, what requires preservation is not only the shared resource, but a form of social organization.

A different approach to the commons in the management literature adopts an institutional perspective, as for example, in Ansari et al. (2013), who emphasize the social construction of the commons. A resource, environmental or social, is ‘elevated’ to CPR when it is defined as vulnerable by a community: just as oceans were perceived differently in different epochs throughout history, the perception of the earth’s climate has also evolved from a kind of commodity to a common good (or CPR) that needs to be preserved, creating a sense of ‘ecological interdependence’ that cuts across humanity (Ansari et al., 2013, p. 1027). This approach takes the commons as the result of a negotiated process by a community, but does not take sides regarding whether there, this form of organizing is an intrinsic good.

Ethics and Organizing: Normative Hurdles and the Lens of Governance

One fruitful avenue to engage in the normative discussions in and around organizing is by situating this debate at the level of governance. This approach, which reflects on the norms, processes, ways of controlling and coordinating, and goals set by organizations, can not only help us categorize moral debates but it also allows us to avoid adopting a single moral framework or normative perspective. Usually, attempts at categorizing normative approaches in the field of business ethics rely on classical ethical theories (e.g. Fisher & Lovell, 2009, pp. 100–144) where teleological and deontological approaches to business practices get confronted and discussed. Similarly, utilitarian and consequentialist theories, or deontological approaches have been used to discuss normativity in corporations (Macdonald & Beck-Dudley, 1994). In addition to these two main paradigms, other ethical approaches such as virtue ethics (Whetstone, 2001), social contract theory (Donaldson & Dunfee, 1999), or even libertarian ethics (Zwolinski, 2007) have been used to make sense of the normative underpinnings of organizing. More recently, other articles have started using feminist ethics to assess the ethicality of commons organizing specifically (Mandalaki & Fotaki, 2020). All these different attempts to categorize and apply ethical theories are always confronted with the problem of incommensurability: the lack of shared measures when analysing different normative paradigms (Collier, 1998), and the difficulty of achieving comprehensiveness and comparability in descriptive ethical decision-making theories (Schwartz, 2016). In contrast to this, governance can be a relevant locus to discuss the ethicality of the commons since it allows us to move away from the abovementioned theoretical puzzles by situating existing normative debates at a specific level of the organization (Collier, 1998; Collier & Esteban, 1999). This is an approach that encompasses the vertical dimension (hierarchy, regulations, command, and control mechanisms) and the horizontal dimension (which emphasizes participation) implied in the governing of an organization (Collier & Esteban, 1999). In our analysis, then, the different ethical issues that emerged with commons organizing will be discussed in the light of debates around governance understood as an instrumental tool for coordination, control, and regulation; or as a form of organizing an intrinsic good such as participation.

According to Collier (1998), governance refers both to the being and the doing of the firm, which leads to question the normative value of the undertaken actions; the purpose, judgement, and conscience behind these; and even the understandings of human life and the notion of good, purpose, and community (p. 634). Our task below will be that of signalling the normative assumptions, goals, and outcomes of specific practices that refer to commons organizing, their understanding of human agency, and their contextualization in time and place. Hence, in the next section, we organize current normative debates in commons organizing as a conversation with the ideal, suggested or performed, forms of governance, and classify these according to the hierarchical and participatory dimensions.

Ethical Aspects in and Around Commons Organizing

Decades ago, Hardin pointed out that the ancient ethical frameworks that are still used today as inspiration to govern societies are too normative and inflexible to govern an increasingly crowded world in constant flux and growth. According to him, historically, codifiers of ethics have not realized that morality is ‘system-sensitive’ (Hardin, 1968, p. 1245). Following Hardin on this point, and given the problem of incommensurability already mentioned, in this article we do not apply pre-established ethical frameworks. Instead, we start with the claims made by those who defend the commons way of organizing. For example, Bollier claims that the core values of the commons are ‘participation, cooperation, inclusiveness, fairness, bottom-up innovation and accountability’ (Bollier, 2014, p. 172). The suitability of the task has already been mentioned in recent work in the field of business ethics: Peredo et al. (2020) have urged scholars to think ‘about ethical concerns and hopes connected with (the) commons’ (p. 660). Our categorization in the next sub-sections aims to convey the complexity and variety of issues surrounding the commons while also situating these debates at the governance level. We argue that challenges corresponding to each category can be connected to one of the two governance dimensions (instrumental and intrinsic), rather than conforming to more abstract theoretical approaches.

We do not intend to answer these concerns, but rather show important themes that are embedded in the commons literature and that have yet to receive proper treatment in the fields of business ethics and organization studies. Ultimately, to have better arguments for the normative superiority of commons organizing, or discuss in which conditions there is such superiority, these questions would need to be addressed.

Excluding

One common argument in favour of commons organizing claims that if a resource could equally be preserved with privatization or as a CPR, the second should be preferred because it can give access to more users with better conditions: ‘Where a common property arrangement means a wider range of people might benefit from a resource instead of a limited few, that would be a prima facie ethical argument in favour of instituting that arrangement and maintaining it when it exists’ (Peredo et al., 2020, p. 664). Yet, as has been argued, even if the commons are a more open form of ownership, it is not the opposite of private property; neither is the commons the same as open access, free-for-all, or a no-man’s land (Bollier, 2014). In other words, commons organizing often excludes some people and usages, and sets boundaries to prevent outsiders’ appropriation.

Thus, an important first normative issue emerges concerning who should be excluded and included in its use, which is different from the question about the difficulty to exclude others from use (often called excludability). A first answer is that exclusion should be determined by the CPR’s capacity: when involving a larger number of users leads to depletion of the resource, the number of users and their usage should be limited. But business ethicists could pose questions that speak directly to the governance of the commons: Who is entitled to draw this limit and exclude anyone from a CPR? And with what criteria?

As Peredo et al. (2018) remind us, property is not divisible in the case of the commons; thus, members cannot be distinguished, nor can they sell their share of rights to whomever they please. Instead, members of the commons have a bundle of rights, which includes the right of a distinguishable group to exclude others from access to the resource or from other aspects of stewardship in relation to it (Ostrom, 2000). Yet, how do members acquire these rights? Usually, from seniority, which may make the commons look like private property owned collectively (though not divisibly) by a limited number of people who just happened to be at the right place at the right time or are direct descendants of those who were there then. All of these are accidental circumstances which might not settle the matter in a conclusive way. Even if one accepted the seniority argument, it would not apply to the moment of the formation of the commons, especially if more people were interested in participating than allowed by the capacity of the resource. The strength of the arguments used for inclusion and exclusion, and who decides on these matters are paramount ethical concerns in the governance of the commons.

Exclusion from the commons can also take place when one commoner repeatedly abuses the resource, after graduated sanctions have been applied (according to Ostrom’s principles). In practice, infractions tend to be rare because the commoners usually solve their problems through face-to-face communication before they become too big or someone must be expelled (De Moor, 2011), which explains the commons’ extraordinary resilience and sustainability over generations. Yet, seniority and acquaintance due to physical proximity might also make exclusion more difficult to implement even if necessary for the preservation of the resource. It is worth to continue studying whether tight, long-lasting community relationships and the capacity for exclusion required for commons organizing enter in tension or reinforce each other. Furthermore, in some cases, commons organizing could have some exclusivist traits that go against some of the ethical principles espoused by commons organizing, such as inclusiveness and fairness.

And yet, although the seniority argument could be challenged in the commons, this very same aspect can be questioned regarding private property (inheritance being a case in point). In both instances, there is a privilege which can be seen as potentially unfair. At any rate, even if the question of moral legitimacy or entitlement in commons organizing comes to surface when we dig into the notion of exclusion, practices of exclusion are usually presented as morally justifiable (instrumentally) since they serve the superior good of preserving the resource.

Subtracting

The question of exclusion is closely dependent on that of subtractability: the degree to which one person's use of a resource diminishes others’ capacity to use it. Public goods like lighthouses and national defence are not subtractable (also explained as there being no rivalry with one individuals’ usage and another’s), while some subtractable resources are renewable (low subtractability), and others are not (high subtractability). Furthermore, the rate of renewability can also vary from one case to another, which affects the need to exclude others and the limits of the subtractable amount. When subtractability is high, the question of exclusion becomes central. In some cases, even if subtractability is low, congestion can occur, so criteria are also needed to establish not just when one can use the resource, but also how much of it at different periods. Here, we would return to the previous questions about who decides and with what criteria to limit subtraction and whether the customary seniority argument is convincing.

As Peredo et al. (2020) observed, following McKean’s (2000) study, ethical issues about subtractability (as well as excludability) can change with advances in technology. These changes affect how much participants in the commons are allowed to subtract from the resource while still enabling others do the same—not just in the present, but also for the future (including the descendants of the current commoners). The new digital technologies made some commons like Wikipedia possible with no subtractability, bringing them closer to a public good than to the CPRs first studied by Ostrom and colleagues. Nonetheless, even in the case of some non-rivalrous goods (e.g. many forms of knowledge), there are attempts to exclude others from using them (e.g. through copyrights and patents). The pending ethical discussion would then be about what grounds there are to exclude others in cases when no one is harmed by other people’s use, and for how long it is justified to prevent others engaging in this subtraction.

In all these debates referring to exclusion and subtraction, the normative aspects exposed are closely connected with an instrumental approach to governance, where governance is basically seen as a form of coordination, control, and regulation, which is a means for another end that has intrinsic value, e.g. the preservation of the CPR and the access to a greater number of people across generations. The alleged superiority of commons organizing have thus a vertical hierarchical dimension that says little about the value of participation itself.

Type of Usage

A different kind of discussion around commons organizing refers to whether there should be restrictions to the type of usage of the resource subtracted from the commons, even if this usage does not preclude others from benefitting from it. In the typical examples of natural CPRs, once subtracted by commoners, the resource can be privately used—for example, timber and fish can be sold, and the rest of the commoners would have no say in this. But in some other cases, commoners can put conditions on the use of the resource, setting specific limitations to the autonomy of participants. For example, the communes studied by Fournier (2013) require that spaces be used collectively, not individually; or that it not be used with a for-profit motive (e.g. subletting a room).

Similarly, studies about public spaces or social centres understood as commons show that Ostrom’s initial allocation and appropriation ideas do not necessarily apply. In these cases, use and production cannot be distinguished from one another because it is the common use in itself that produces the ‘commons’. In other words, commons ‘are not just about organizing in common the private appropriation of resources, but organizing in common for the commons, that is, for common use’ (Fournier, 2013, p. 449). The goal of commons generation is an implicit normative a priori that conditions the discussion on the purpose of commons organizing. This type of understanding uses ethical arguments to declare some usage desirable or undesirable, particularly regarding commercial usage.

Ultimately this discussion revolves around the question of whether the commons (both as a resource and as an organizing system) should remain outside of the market system. Similarly, one can consider the relationship of the commons with the State. Some approaches want to keep the commons as independent as possible from markets and State, in order to preserve a real alternative to enclosure, commodification and consumerism, as well as from any top-down authority and external regulation; while other views acknowledge that the commons are intrinsically dependent on or can benefit from interactions with the State and the market in all sorts of direct and indirect ways, such as government regulation, funding and support, as well as selling to companies or forming commons-based for-profit companies. Hence, these debates are not merely instrumental but intertwined with moral considerations about the purpose of commons organizing, insofar as commons organizing becomes part of a political agenda to recover goods from the hands of both government and markets.

Polycentricity and Subsidiarity

An ethical argument used to support commons organizing is that its governance is closer to the final beneficiaries or those most immediately affected by the resource. In other words, this way of organizing follows the subsidiarity principle, which considers desirable and fairer that the local community (or most immediate level) is able to determine, modify, and enforce the rules by which the resource is governed, rather than putting this in the hands of a centralized distant authority. One version of this argument is that self-governance is functional or instrumental in helping preserve the CPRs, or that it is more effective, works for a longer term, or benefits more people than a private organization or the State would. To support this argument, it is claimed that locally designed mechanisms can outperform centralized ones in managing natural resources (Armitage, 2005). Another version of the argument would claim that even if this were not true (or not clearly true in the short term), self-governance should be considered an intrinsic value, as we will see below, insofar as it empowers individuals and communities, enhancing human autonomy and dignity.

As part of the instrumental version of the argument, one reason given as to why it is desirable to maintain the decisions at the local level is that ‘[e]ach commons is special because each has evolved in relationship to a specific resource, landscape, local history and set of traditions’ (Bollier, 2014, p. 12) taking to the fore the contextual dependency of the different forms of organizing (Collier, 1998). Since there is no standard formula or design, the governance should be kept at the level closest to the resource, which would lead to multiple centres of authority. These diverse local centres of governance can be nested within higher levels of governance, an idea captured by the concept of ‘polycentricity’ proposed by Vincent Ostrom (1999 [1972]). Polycentric governance requires mutual adjustment among the centres of decision-making in order to attain a set of shared goals, in a non-hierarchical and inclusive way. It is believed that this would increase the variety of solutions and choices from which different communities can learn to self-manage their resources (Van Zeben, 2019).

Unsurprisingly, controversies emerge regarding whether some overarching authority is needed to monitor a general system of rules, and when and where such an authority has the right to interfere. Although some coordination is necessary, different views are likely to arise about what is best left to the local level and what needs to be treated at a higher level, since actions that are beneficial locally could have a negative impact globally. Furthermore, a collection of resilient local environments might be necessary, but still insufficient for general environmental preservation, renewal, or stability. Hence, while polycentricity puts forward an alternative to top-down approaches, leading to a complex nested system, it also opens questions about the role of hierarchy in governing the commons, about the appropriate level of decision-making, and about how consensus emerges when it comes to treat a resource as a commons. For example, as mentioned earlier, Ansari et al. (2013) have studied the disagreements about whether one can consider the climate as a commons and about what is the appropriate level of decision-making. In this regard, advocates of the commons admit that ‘[s]uch global commons are indeed a departure from the classic notion of the commons’ (Bollier, 2014, p. 144).

In sum, existing debates on polycentricity and subsidiarity interconnect vertical, instrumental discussions on the functionality of commons organizing (i.e. the importance of immediacy and a grounded approach to the specific time-place of organizing) with other normative statements about the purpose of participating in commons organizing as a path towards the moral development of individuals. This tension is present in debates around the so-called ‘new commons’ (Hess, 2008), where we can problematize the need for a hierarchy if there is an ulterior good to be protected. For example, when one considers climate or industry reputation as commons, would polycentricity or subsidiarity be the best way to protect them? Should we impose limits on polycentricity and subsidiarity if we were to enrich the human condition of participants? These debates lie on the instrumental side of governance, insofar as they emphasize the commons as a tool for another pragmatic goal rather than a form of enriching the human condition of participants (Collier & Esteban, 1999).

Individual Engagement

One of the main appeals of commons organizing is that it is a form of self-government, which requires the individual engagement of users in decision-making, in devising the basic rules of subtraction, exclusion/inclusion, and the system of graduated sanctions, as well as their participation in monitoring, implementing sanctions, and conflict resolution. Decentralization and polycentricity also go in the direction of enhancing the possibility of more people participating in the affairs of the commons. Following a classic Tocquevillian argument, it can be argued that participation has ethical value in itself, since it gets individuals accustomed to exercising their freedom and autonomy (Collier & Esteban, 1999, 184). Thus, from this perspective, the ethical superiority of commons organizing comes from involving citizens in a horizontal type of governance, which is a learning tool for democratic political engagement—an argument that could be used even in cases in which some efficiency is lost.

From an instrumental perspective, such participation is seen as good for transparent information flows and deliberation (De Angelis, 2017), which can provide flexibility and adaptability in front of threats (like depletion of a resource); thus, increasing the resilience of the commons. Another instrumental argument is that individual engagement in governance mechanisms is oftentimes thought to contribute to trust and legitimacy of institutions, which helps their long-term sustainability and development. Expanding on an argument already advanced by Ostrom (2003), Albareda and Sison (2020) point out that the interpersonal relationships that spin from participation promote a shared sense of identity and an understanding of the problems, as well as of the norms and values operating in each scenario (see also Collier & Esteban, 1999). Individual engagement, then, takes an educational dimension that is important for the maintenance of the commons, instrumentally, in addition to being an intrinsic value.

Community

Associated with the benefits of individual engagement, another benefit of the commons as a social system, at least in the traditional commons, is that it provides cohesion within communities and reinforces a ‘cultural identity’ and ‘a way of life’ that is rooted in a particular territory, preserving its customs and idiosyncrasies. This is why the defence of the commons is considered a ‘vernacular movement’ (Bollier, 2014, p. 34), meaning that it is local and embedded in a place. Against the atomistic perspective underlying human interactions in markets, advocates of the commons think that communities can advance in terms of welfare and address social needs by sharing common property (Peredo et al., 2018). For the model of the commons is not just understood as an economic or an ecological model; it also promotes the community itself, its solidarity, and general wellbeing, as it generates the ‘conditions for the long-term resilience of community self-organization’ (Albareda & Sison, 2020, p. 731).

Other authors have taken these ideas further by claiming that organizing the commons is not only about producing, using, or preserving a resource, but that the community itself is a product of such form of organizing. In this view, the verb ‘commoning’ refers to creating a community, which is both preserved and enhanced through commons organizing (Fournier, 2013). Scholars who study public spaces as commons particularly emphasize this point (Brandtner et al., 2023). For example, in the process of turning a space or a resource into a commons, the residents, users, or commoners telling stories about it form a narrative that is essential for its maintenance and in turn (re)produces the community (Fournier, 2013). The question of whether a community needs to pre-exist or is created in the process of ‘commoning’ is not necessarily binary. An incipient community may be needed in commons organizing, at least to connect people, just as it is needed in any other type of social and economic activity.

Furthermore, from this perspective, commons organizing has a positive impact even beyond the users or direct participants, since others also benefit from living in a place where there is a vibrant community. Because of this, in some cases, Ostrom’s key organizational principles, ‘such as the clear distinction between users and non-users or the definition of how much each can use, lose some of their relevance’ (Fournier, 2013, p. 444). Yet, these positive impacts might in other cases clash with the exclusivist traits of commons organizing discussed above.

Now, the relation between community and commons organizing can also raise some questions. For example, in his study of organizations as commons, Hartman (1994) argued that agreements and a strong culture are necessary to avoid free riding. This might suggest that to preserve the commons a certain level of homogeneity among participants is convenient, since the stronger the commoners’ belief in the organization, the less need there is of formal control. Business ethicists and organization scholars could raise the question of how commons organizing can combine the strong culture and staunch loyalty that it seems to require with the respect for the autonomy and capacity to dissent of individuals. As with individual engagement, the community spirit with its emphasis on solidarity, cohesion, and cultural embeddedness of participants might be simultaneously a requirement (or a means) for commons organizing, or a goal—and an organizational purpose. Thus, the discussion around the role of communities in commons organizing affects not only the rules of engagement for proper commons organizing but also the creation of communities of purpose and practice as an intrinsic good.

Human Character

Another ethical argument that has been proposed is that individual engagement in the commons is prone to generating certain valuable characteristics in individuals, such as empathy, care, and reciprocity. In other words, commons organizing would lead to developing certain virtues. Scholars adopting a virtue ethics approach (Albareda & Sison, 2020) maintain that there is a similarity between commoners participating in commons organizing, citizens sharing an ideal of the common good of society, and people working for the common good of the firm; all these cases allow human beings ‘to develop technical or artistic skills and intellectual and moral virtues’ (Sison & Fontrodona, 2012, p. 212). This is in line with the claims of supporters of the commons such as David Bollier (2014): ‘the commons sets forth a very different vision of human fulfilment and ethics’ (p. 5), suggesting ‘new models of human morality’ (p. 6), which contrast with the view of the self-interested individual portrayed by homo economicus.

This normative ethical approach also emphasizes the idea that certain contexts facilitate the development of individual virtues such as justice, courage, honesty, and friendship (Melé, 2009) that are essential for human flourishing and human dignity (Frémeaux & Michelson, 2017). Ostrom’s principles of self-government, graduated sanctions, and monitoring could be said to create a context that facilitates truthfulness and accountability, which in turn makes people behave in more virtuous ways in the long-term, escape narrow self-interest, and adopt more pro-social attitudes. Future research could explore empirically whether moral virtues and attitudes (and which ones in particular) are indeed a result of commons organizing. Organization scholars could counter-argue that some pro-social attitudes and virtues are necessary to get together and develop commons organizing in the first place. As in the previous sub-section, the answer might not be binary: both could develop hand-by-hand. But, at any rate, the question about the relationship between human character and participation in the governance of the commons is yet to be fully explored, particularly the problematic tensions between moral virtues and anonymous participation, as we will discuss below.

There are other alleged virtues associated with commons organizing, such as austerity or frugality, as opposed to maximizing gains, opulence, excess, and waste: ‘The commons, properly understood, is about the practice and ethics of sufficiency’ and ‘providing for one’s household’s needs’ (Bollier, 2014, p. 32). These virtues are seen as reinforcing the notion of environmental stewardship (see below) and question ‘the claims made by contemporary economists that humans are essentially materialist individuals of unlimited appetites, and that these traits are universal’ (Bollier, 2014, p. 81). Again, the question emerges: Which one is the dependent variable in this relationship between virtues and commons organizing?

Finally, according to its apologists, the commons are also linked to the idea that certain rights are inalienable or not for sale (Bollier, 2014, p. 104), and to the idea of advancing human dignity (Albareda & Sison, 2020). Yet, the concepts of rights and dignity might require a particular type of liberal regime, which emphasizes individual autonomy, and might be at odds with communitarian views—which often emphasize tradition, give priority to the community over the individual, and are not necessarily committed to the moral equality of individuals. A solution to this classical tension in political philosophy might not be fully achievable but should be recognized and incorporated in studies on commons organizing.

Environmental Stewardship

Probably the strongest claim coming from Ostrom’s perspective (1990) is that common ownership is equally effective (if not more so) than the alternatives when it comes to organizing and preserving certain CPRs. Amongst authors endorsing the superiority of commons organizing, Andrew King (1995) argued that ecological surprises, including the collapse of an ecosystem, can be better dealt with, prevented, or avoided by managing natural resources as community property. Even if it may seem at first a slightly inefficient way of managing, commons organizing averts overcontrolling the ecosystems and is better at providing adaptability and ecological resilience (King, 1995). King also observed that commons organizing involves a socioeconomic fabric which has been defined as a ‘moral economy’ and incorporates a commonly shared goal of local stability (King, 1995, p. 970).

The interweaving of social and environmental aspects is clear in this argument. Sustaining the commons is sustaining one’s community and one’s own identity, since this way of organizing is ‘more likely to care about the long-term sustainability of a resource than a market, because the very identities and cultures of commoners are wrapped up in the management of the resource’ (Bollier, 2014, p. 110). Thus, commons organizing leads to both communal and environmental resilience in front of potential ecological disasters. This explains why the commons are associated with stewardship ethics (Bollier, 2014), which, interestingly, Collier and Esteban (1999, p.175) see as falling within the hierarchical view of governance and which, in our classification, would have an instrumental dimension, insofar as it is a means to a higher end (which could be achieved also through other means). A system of stewardship is different from that of ownership since the key is to ensure that a resource has the capacity to protect and reproduce itself, in such a manner that it can be used and enjoyed through time (even generations), rather than consumed entirely to satisfy unlimited human appetites. The logic of use is different from that of consumption. Stewardship means ‘beginning to act as if we have inalienable stakes in the world into which we were born’ (Bollier, 2014, p. 150–1).

Yet, whether stewardship is possible depends in many ways on scale. Ostrom’s classical studies tend to focus on small-scale and locally governed CPRs, such as high mountain meadows, forests, or irrigation institutions. The generalizability of these studies is questioned since they might only hold in relatively insulated small groups with face-to-face communication, which facilitates agreements and the creation of shared norms as well as a system of reciprocity (Araral, 2014, p. 15–17). Thus, there are some doubts about the application to a larger scale, including the transnational global level. Whether technology and a sense of interconnectedness can change that narrative is uncertain. As we shall see below, this is not a problem in the digital commons, where the finitude of resources is partially unlocked (O’Mahony, 2003, p. 1182).

Debates about environmental stewardship tend to privilege the instrumental value of commons organizing insofar they focus on how flexible and adaptable a governance model provides the right social fabric for the protection of an environmental resource. The intrinsic value of participative governance comes to the fore via the moral superiority of the promotion of individual engagement and sense of community, and the reduction of consumerism which are moral goods prone to make virtuous, sustainability-conscious, citizens.

The eight themes we have presented include the implicit or explicit ethical ideals, concerns, and challenges emerging from the literature on the commons that talk to the different dimensions (i.e. vertical and horizontal) of governance (Collier & Esteban, 1999). Table 1 summarizes these themes, including the embedded normative questions yet to be addressed for each theme, together with references to the main authors that have touched upon them so far in the business ethics literature.

New Debates on Commons Organizing in the Digital Economy

If some of the themes discussed above can be found in other commons beyond the traditional ones (e.g. urban commons as in Feinberg et al., 2021), the disruptive capacity of the digital world, and the tensions associated to it are set to impact commons organizing on a different scale. It has been said that the digital world opened possibilities for sharing and cooperation, while there is no history of enclosure; hence ‘there are no legacy institutions to displace’ (Bollier, 2014, p. 139). This has led to a new surge of the academic debates around the commons, particularly focussing on Creative Commons licensing, as well as initiatives such as Wikipedia, blockchain and crypto currencies (Aaltonen & Lanzara, 2015; Benkler & Nissenbaum, 2006; Davidson et al., 2018; Poux et al., 2020).

In addition to deepening and expanding some of the previous normative debates such initiatives pose new ones. While some studies have built on Ostrom’s institutional design principles (Rozas et al., 2021; Van Laerhoven et al., 2020), others have emphasized the difference in terms of excludability and subtractability in cases in which resources are nonmaterial and human-created, as in the digital commons (Dallyn & Frenzel, 2021; De Angelis & Harvie, 2014; Fuchs, 2020; Pazaitis et al., 2017; Peredo et al., 2020; Wittel, 2013).

For example, Rozas et al. (2021) have explored the compatibility between blockchain technology and Ostrom’s eight principles, and how this applies specifically to the governance of digital commons. Alternatively, De Angelis and Harvie (2014) observed that digital resources such as software or databases have no physical limits that jeopardize their sustainability, since they are non-rivalrous goods. Similarly, Wittel (2013) reasoned that the digital commons are free from the problems outlined by Hardin, making the need for enclosure or privatization apparently obsolete, since allegedly ‘there is no conflict between the interests of individual commoners and the interest of the community of all commoners’ (p. 321). Further, Dallyn and Frenzel (2021) propose the notion of a ‘more sustainable and scalable postcapitalist commons’ (862) proposing a revision of Ostrom’s first design principle of commons boundaries and the right to withdraw resources.

Thus, at least apparently, the resources being shared in the digital dimension fall into a different category than the material things that the ‘traditional commons’ literature has hitherto dealt with. Material things become reduced when they are used and shared, whereas digital ones are multiplied through use and sharing. This may require less or no monitoring in terms of exclusion and subtraction, but might still require governance. An immediate question is whether the new commons still fall under the category of the commons discussed above. Hess’s definition of the commons (mentioned in the introduction of this article) is broad enough to include the new commons: ‘a resource shared by a group where the resource is vulnerable to enclosure, overuse and social dilemmas. Unlike a public good, it requires management and protection in order to sustain it’ (Hess, 2008, p. 37). Yet, the answer is not so evident, even if at this point we can highlight the commonality of requiring a specific form of surveillance or governance. Below we explore the new questions which have been dealt with in the literature that specifically discuss the digital commons, which add new normative debates to our previous categorization.

Fighting New Forms of Alienation

Through Creative Commons licensing any given user can have free access and reuse digital content such as images, videos, music, texts, and many others (to different degrees, copyleft being the most permissive). The same largely happens with content being uploaded on social media. Such content can be seen as a commons, which others can use; and the creators of content made available in these spaces can be seen as commoners, contributing with their work to a commons. Yet, what is at stake here is that they generate a resource they may not be fully aware of. Fuchs (2020), who has examined the ethical underpinnings of the digital commons, concludes that ‘[d]igital corporations such as Facebook, Google, and for-profit open access publishers, practice a sort of communism of capital: they advance the production of particularistic types of commons that are subsumed under the logic of capital’ (Fuchs, 2020, p. 114). Capital is accumulated through the free labour of users, who inadvertently produce the data and content of platforms. Using a Marxian lens, what is produced, shared, or given freely and voluntarily becomes alienated through loss of control of the product of one’s labour and estrangement from one’s contributions to society. An alternative to this would lead to a normative discussion about participation in the commons and its governance structures.

The reverse is also true. While the digital world presents new possibilities of alienation that go against the ethical ideals of the commons, new possibilities to fight alienation emerge too (Kleiner, 2010), supported by new forms of collaboration and governance. After his criticism, Fuchs (2020) presents a positive ideal of what a digital society based on the commons would look like, avoiding current forms of digital capitalism. The questions that business ethicists and organization scholars could further inquire are how commons organizing can indeed help prevent the appropriation of data by for-profit companies, fight alienation, and fulfil the ideals of participation, individual engagement and sense of community mentioned above, as well as inquiring which obstacles these efforts face. In this regard, the issue is not only the functionality of commons organizing in the digital commons, but also the nature of that participation, and whether it contributes to the preservation of the commons as a third entity separated from the State or the market; or whether it is finally subsumed into capitalism itself.

Fighting New Forms of Commodification

As a follow-up from the previous debate, according to the commons perspective, the logic of the capitalist market turns gifts into commodities by swallowing areas that have not yet been regulated by monetary exchange (Wittel, 2013), a process which makes capitalism dependent on the relentless enclosure and commodification of the commons (Caffentzis, 2010). To resist such effects, commodification must be avoided. This recurrent dynamic becomes particularly clear with the digital commons. Even if free labour in the digital world could be considered less alienating than wage labour (in principle it is unconstrained and, quite often, enjoyable), it is also more easily exploitable and commodified (Wittel, 2013).

In this regard, some have seen the digital commons as part of a gift economy logic. As pointed out by Wittel (2013), the gifts of the digital commons are nonspecific, since it is not clear who will receive them and no return is expected, like blood donations, which can be understood as gifts to abstract individuals, communities, or to humanity. Interestingly, not only individuals but also software companies indirectly finance open-source code like Linux, and universities indirectly support Wikipedia through the contributions of their employees. Even if oftentimes the free contributions to the digital commons are later commodified, it is the participation in the governance of the digital commons that opens possibilities for counter-commodification. Data cooperatives aiming to democratize and take control of health research could be an example (Rodon, 2019).

Future inquiry could extract lessons from successful or failed experiences of resistance to commodification in the digital world. For this, a governance of the digital commons needs to develop. Now, the engagement of the commoners in the governance of digital commons does not only need to preserve the autonomy or the creativity of labour, but it promotes the intrinsic value of participative governance (Collier & Esteban, 1999). Once again, the interaction of these experiences with the market and the State become problematic since the digital commons are embedded in a symbiotic relation with the other two.

Fighting the Lack of Accountability

As pointed out above, a tension might exist between anonymous participation and the moral virtues associated with individual engagement in the commons such as empathy, care, reciprocity, trustworthiness, and accountability. For example, blockchain technology poses new questions to be added to our previous categorization of ethical claims and concerns on commons organizing. This technology is presented as trustless, not in the sense that trust is eliminated, but that trust is distributed among many anonymous participants who verify the ledger, so that there is no need to rely on a third party, such as an institution or an authority. It is a form of collaboration without intermediaries that creates a new commons.

Authors like Meyer and Hudon (2019) have suggested that monetary systems based on blockchain technology like crypto currencies (CC) may contribute to the common good by creating new communities and new collective wealth. CC have been portrayed as more democratic than fiat currencies because they open up spaces for collective action, they are decentralized, and their way of operating is somewhat spontaneous, which could be seen as aligned with the principles of polycentricity and subsidiarity mentioned above. However, the ethical status of digital currencies is sometimes critically understood as part of a ‘libertarian project for contesting banks and state control of monetary movements, as well as seek for privacy and anonymity’ (Meyer & Hudon, 2019, p. 283).

On the one hand, the digital commons facilitate what Benkler and Nissenbaum (2006) call ‘commons-based peer production’ (e.g. Wikipedia), in which a common goal motivates a heterogeneous mass of people to work without financial compensation. But, on the other hand, such high ideals are contested in practice in many CC where speculation and unsustainable use of energy are added to previous ethical concerns, thus further problematizing a participation that can create more global evil than good.

Poux et al. (2020) argue that blockchain technology can make the commons governance mechanisms of monitoring and sanctioning obsolete, being particularly useful in cases ‘where monitoring and sanctioning is either too hard or costly, and in cases where the lack of confidence and trust in governance has led to the poor management of CPRs’ (p. 12). The definitional conundrum exposed above becomes even more acute now when, apparently, we can retrieve agency from the governance of the commons which would become—sort of—automated. In short, we are being confronted by an individual participation that ceases to be an intrinsic good and simply becomes an instrumental requirement for the sustainability of the commons over time.

Along the same lines, De Filippi et al. (2020) argue that, rather than being a ‘trustless’ technology, blockchain is a ‘confidence machine’, meaning that it produces confidence based on a procedural and rule-based functioning, that takes into consideration past performance. In this regard, the governance of the infrastructure remains crucial but is devoid of any non-instrumental purpose. Regarding bitcoin, De Filippi and Loveluck (2016) observe how it seeks to eliminate the need for trusted authorities, but simultaneously creates a highly technocratic power structure made by those with the right skills to understand the complexities of the infrastructure, introducing market-based incentives that ‘distort the underlying motivations of people, who are ultimately brought to compete with each other’ (De Filippi, 2019).

In sum, following Meyer and Hudon (2019), even if CC are sometimes presented as more transparent and democratic than traditional currencies, CC also aim to protect anonymity; and this has been associated with social ills as tax evasion, money laundering and, more generally, illegal, and unethical transactions. This comes straight at odds with the ethical status envisioned in much of the commons’ literature analysed above and particularly with the moral qualities attributed to participative governance (Collier & Esteban, 1999).

For CC to have a positive contribution they should be understood as an asset to promote participation, community building and human virtues, along the lines of the different non-instrumental debates exposed in Table 1. Whether and how this is achieved are still open questions. To iterate, one should ask if the engagement through digital anonymity can be in line with the values of commons organizing; or whether participation and community building in the digital sphere require any personal accountability whatsoever.

Table 2 encapsulates the ethical themes and questions that emerge surrounding the digital commons, with the underpinning normative questions and the main papers of reference.

Discussion

Our analysis has unpacked and categorized the ethical claims and concerns embedded in the discussion of the commons and of the digital commons. We did this by delving into the literature of this field of study and focussing on the definition of a concept that remains ambiguous and problematic, which is critical when it comes to clarifying its ethical claims (Araral, 2014; Peredo et al., 2020). As we have argued, to overcome the limitation of the incommensurability of traditional ethical theories, the perspective of governance (Collier, 1998; Collier & Esteban, 1999) provides a fruitful avenue to explore the normative underpinnings around the alleged superiority of the commons.

In the management literature, instrumental concerns around the protection of the environment remain one of the main dimensions in which commons organizing is seen as having a positive impact, particularly in relation to crisis management (Ansari et al., 2013; Barnett & King, 2008). The operative issue about the sustainability of the resource over time leads to questions of exclusion and subtraction, which are key not only in terms of defining the commons, but also in terms of who is to decide about access to the CPR, the level and type of subtraction, and with what criteria this decision is made. As already observed, one of the main fallacies at the inception of this discussion is that Hardin described the commons as a tragedy, when in fact he was talking about the tragedy of open access (Bromley, 1992).

In Ostrom’s canonical understanding, CPRs need some shared rules of institutional design in their management; otherwise, they might not qualify as ‘commons’. Polycentricity and subsidiarity are two important features that point to the value of self-governance, but they also raise questions about the issue of scale and the role of hierarchy. This dimension is complemented by the claims about the intrinsic good achieved by individual engagement in the governance of the commons (Albareda & Sison, 2020; Araral, 2014; Ostrom, 1990). Connected to self-governance, it has been argued that commons organizing at a local level can generate benefits such as democratic participation, community building, and improvement of human character, which make it a superior alternative to other forms of organizing. Thus, the positive impacts of commons organizing occur at the macro (planet, system), meso (community), and micro (individual) level. Yet, as we have pointed out, rather than taking the ethical claims at face value, in each of the themes analysed there are remaining ethical concerns which deserve to be studied in greater depth in the future.

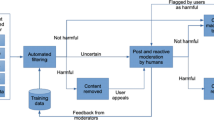

An interesting avenue for further research is the study of the interactions and tensions among the principles and features of the commons we have analysed, rather than treating them separately. To advance this discussion, we propose a model of commons organizing (depicted in Fig. 1) that, mirroring Collier and Esteban (1999)’s framework discussing the governance of participative organisations, has two main dimensions: (i) the instrumental one which leads to the preservation of the resource and echoes pragmatic concerns about how governance is structured and coordination achieved; and (ii) the participatory one, which includes intrinsic values about the community and the individual generated through commons organizing. Our figure puts the participatory dimension of governance, which echoes ethical and political concerns, at the centre. It also includes the challenges surrounding the digital commons (at the right side of the figure) as affecting and potentially being addressed through participatory mechanisms.

On the instrumental side (left side in the figure), governance leads to decisions on norms and protocols concerning exclusion and subtracting, and types of usage, which will affect stewardship. As argued above, these are first and foremost instrumental aspects of commons organizing since the end goal of the reflections that feed the academic debate on these issues is the preservation of the resource (they are not ends in themselves; in other words, if there were a better way to preserve the resource, that would be preferable). Yet, this has an impact on, and is impacted by, the participatory dimension of governance, which raises questions about who decides (and on which basis) about exclusion, subtraction, and type of usage (these interactions are symbolized in Fig. 1 with two thick horizontal arrows going in opposite directions). For example, if this community is intertwined and interdependent in relation to a resource, this would reinforce the sense of stewardship towards that resource. Furthermore, the type of usage given to the commons implies a normative a priori about the kind of society the commons seek to create, and the purpose of participation—in Collier and Esteban’s categorization.

On the participatory side of commons organizing, four interconnected themes have emerged: polycentricity and subsidiarity, community building, individual engagement, and human character. For example, individual engagement reinforces, and is reinforced, by a sense of community: individuals are more willing to participate in commons organizing if they feel part of the community and, conversely, individuals feel more part of the community if they can engage in its affairs. What comes to the fore here is a normative dimension of commons organizing that defends it because of the kind of society and the sort of individuals it produces. In this regard, individual engagement in self-governance through commons organizing is seen also as promoting a specific individual character. Similarly, a sense of community and the development of moral virtues are often seen as reinforcing each other. Moreover, the principles of polycentricity and subsidiarity reinforce and are reinforced by the sense of community and by individual engagement in participatory governance. All these debates involve values as ends in themselves, and, as in Aristotle’s Politics, contain a discussion about the type of polis humans should strive to create.

In short, while discussions on the commons usually include many instrumental and intrinsic claims, these are seldom organized, and connections are left undefined. We argue that this analysis is necessary and, if it were further pursued, the different elements of participatory governance would turn out to be the basic dimension of commons organizing, as depicted in the model we propose, encompassing different ethical and political themes, and connecting with the instrumental side of governance. Nonetheless, it is worth exploring whether this complex set of relationships also includes tensions that might be neglected and deserve greater attention. To name only two possible tensions (represented in Fig. 1 with dashed arrows), a community might put its interests as separate from, and in contraposition to, the stewardship of the natural resource, and can suffocate the individual engagement that allow the development of individual character. In other words, not all communities encourage equal participation in self-governance, due to power differences or to pragmatic or instrumental reasons.

Finally, in this article, we also analysed the ethical challenges surrounding the emergence of the digital commons in terms of alienation, commodification, and personal accountability, and how using the axis of participative governance sheds light onto new dilemmas in the digital domain. In this regard, important debates emerge concerning the value of ‘involuntary’ work done in the digital arena, or the value of data being produced either consciously or inadvertently—data easily commodifiable despite the user’s obliviousness. Several questions remain unanswered: What new forms does alienation take in the digital world? Can they be avoided? Can work be de-commodified (e.g. through platform cooperativism), as a way of fighting exploitation? Does the emergence and consolidation of commons organizing in the digital world require State support through laws to limit business practices of commodification?

The degree of interdependence between the participatory dimension of governance and the challenges of the digital commons remains unsettled (as symbolized in Fig. 1 with a question mark next to the horizontal arrows). Stemming from our previous categorization, what seems clear to us is that these affect mainly the normative (non-instrumental) reflections related to the political, societal, and individual impacts that are central to commons organizing. The new forms of alienation and commodification might be resisted or avoided thanks to participatory governance, if this becomes a requisite to form ‘digital commons’. Additionally, anonymous engagement brings in a new channel of participation that was not there in the traditional commons. However, there are tensions here as well, which would need to be further studied; for example (as symbolized in Fig. 1 with a dashed arrow), it is not always clear that anonymous engagement in the digital sphere can sustain participation while simultaneously building a sense of community.

Conclusion, Limitations, and Notes for Further Research

In this paper, we have performed a critical reading of the commons organizing in relation to its main ethical ideals, attributes, and concerns, putting special emphasis on the participative governance of the commons. Rather than applying classical, pre-established ethical frameworks, our article has highlighted the normative reasons found in the commons literature that justify that the commons can be seen as a superior alternative way of organizing for human beings, and the planet. Our analysis has also recognized some of the major normative controversies, which remain unsolved and deserve more attention than they usually receive. As we argue, one way to clarify these debates would be to differentiate the underpinning instrumental aspects and the intrinsic values associated to commons organizing, while also trying to see their interconnections, and which dimensions play a more central role. We also consider that the advent of the digital commons adds complexity to these debates but can also underline the importance of participation in self-governance as a crucial dimension for the analysis of the commons.

Our categorization highlighted the main normative debates around commons organizing and its specific form of governance presented mainly and mostly in the management literature, but ours is not an exhaustive one. Alternative typologies could be built incorporating intrinsic vs extrinsic justifications around commons organizing and its corresponding moral terminology. To this we must argue that the centrality given to participative governance in our categorization works for a purpose. Can we still talk about commons governance in organizations with loose rules, fuzzy membership, no rule enforcement and trustless or trustfree systems that require support from the state to guarantee their survival?

Even if we raise some of these concerns in the paper, addressing these points in detail would demand a separate conceptual paper. What seems evident to us is that the fuzzy boundaries of commons organizing in the literature reflect no more than the social, political, and axiological struggles around a coveted term. Struggles that reflect once more the irresistible pulsion by market forces and governments to enclose the commons even if now at a conceptual level (Tréguer & De Rosnay, 2020). The risk of escalating the terminological debate into different forms of ‘commonswashing’ or semantic appropriation (De Rosnay, 2019) seems evident to us and should be given further critical consideration.

References

Aaltonen, A., & Lanzara, G. F. (2015). Building governance capability in online social production: Insights from Wikipedia. Organization Studies, 36(12), 1649–1673.

Albareda, L., & Sison, A. J. G. (2020). Commons organizing: Embedding common good and institutions for collective action. Insights from ethics and economics. Journal of Business Ethics, 166(4), 727–743.

Ansari, S., Wijen, F., & Gray, B. (2013). Constructing a climate change logic: An institutional perspective on the ‘tragedy of the commons.’ Organization Science, 24(4), 1014–1040.

Araral, E. (2014). Ostrom, Hardin and the commons: A critical appreciation and a revisionist view. Environmental Science & Policy, 36, 11–23.

Armitage, D. (2005). Adaptive capacity and community-based natural resource management. Environmental Management, 35(6), 703–715.

Barnett, M. L., & King, A. A. (2008). Good fences make good neighbors: A longitudinal analysis of an industry self-regulatory institution. Academy of Management Journal, 51(6), 1150–1170.

Benkler, Y., & Nissenbaum, H. (2006). Commons-based peer production and virtue. Journal of Political Philosophy, 14(4), 394–419.

Bollier, D. (2014). Think like a commoner: A short introduction to the life of the commons. New Society Publishers.

Brandtner, C., Douglas, G. C., & Kornberger, M. (2023). Where relational commons take place: The city and its social infrastructure as sites of commoning. Journal of Business Ethics, 184(4), 917–932.

Bromley, D. W. (1992). The commons, common property, and environmental policy. Environmental and Resource Economics, 2(1), 1–17.

Caffentzis, G. (2010). The future of “the commons”: Neoliberalism’s plan B’ or the original disaccumulation of capital? New Formations, 69(69), 23–41.

Collier, J. (1998). Theorising the ethical organization. Business Ethics Quarterly, 8(4), 621–654.

Collier, J., & Esteban, R. (1999). Governance in the participative organisation: Freedom, creativity and ethics. Journal of Business Ethics, 21, 173–188.

Dallyn, S., & Frenzel, F. (2021). The challenge of building a scalable postcapitalist commons: The limits of FairCoin as a commons-based cryptocurrency. Antipode, 53(3), 859–883.

Davidson, S., De Filippi, P., & Potts, J. (2018). Blockchains and the economic institutions of capitalism. Journal of Institutional Economics, 14(4), 639–658.

De Angelis, M. (2017). Omnia sunt communia: On the commons and the transformation to postcapitalism. Zed Books Ltd.

De Angelis, M., & Harvie, D. (2014). The commons. In The Routledge companion to alternative organization (pp. 304–318). Routledge.

De Filippi, P. (2019). Blockchain Technology and Decentralized Governance: The pitfalls of a trustless dream. Decentralized thriving: Governance and community on the web, 3. hal-02445179.