Abstract

At a time when firms signal their commitment to CSR through online communication, news sources may convey conflicting information, causing stakeholders to perceive firm hypocrisy. Here, we test the effects of conflicting CSR information that conveys inconsistent outcomes (results-based hypocrisy) and ulterior motives (motive-based hypocrisy) on hypocrisy perceptions expressed in social media posts, which we conceptualize as countersignals that reach a broad audience of stakeholders. Across six studies, we find that (1) conflicting CSR information from internal (firm) and external (news) sources elicits hypocrisy perceptions regardless of whether the CSR information reflects inconsistencies in results or motives, (2) individuals respond to conflicting CSR information with countersignals accusing firms of hypocrisy expressed in social media posts, (3) hypocrisy perceptions are linked to other damaging stakeholder consequences, including behavior (divestment, boycotting, lower employment interest), affect (moral outrage), and cognition (moral condemnation), and (4) firms with higher credibility are more likely to experience adverse effects of conflicting CSR information. These findings advance theory regarding the effects of conflicting CSR information as it relates to the role of credibility and different forms of hypocrisy. Importantly, damaging social media posts and stakeholder backlash can arise from hypocrisy perceptions associated with inconsistent CSR results as well as inconsistent motives, and strong firm credibility only makes a firm more vulnerable to this backlash.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In the information age, firms can signal their commitment to corporate social responsibility (CSR) by disseminating their performance online (Saxton et al., 2019), and these signals can be echoed by social media users, who spread this information to their own networks. Social media is particularly effective for promoting communication among a large number of stakeholders and makes activism easier as it allows for the widespread expressions of support for firms (Earl & Kimport, 2011; Ma & Bentley, 2022). Social media also can be used for admonishment (Lewin & Warren, 2023; Ryoo & Kim, 2023). For example, a social media user recently posted a negative message highlighting the conflict between luxury brand Coach’s practice of slashing unsold inventory so it cannot be reused (Kurutz, 2022) and Coach’s policy of repairing damaged purses, which is part of their commitment to reduce the firm’s impact on the environment (Coach|Our Planet n.d.). The social media user’s post on conflicting CSR information spread internationally after multiple news outlets covered the story (Avery, 2021; BBC 2021; Kurutz, 2022; Noyen, 2021; Ritschel, 2021). Thus, one social media post countersignaled Coach’s commitment to CSR and the messaging was amplified by international news sources.

Hypocrisy perceptions caused by conflicting CSR information are only damaging, however, if the organizational audience responds negatively to such claims. ‘Tolerable hypocrisy,’ is theorized to be inconsistencies between CSR results or motives that stakeholders excuse or justify and “has limited, if any, effect on trust, as such hypocrisy is expected” by the organizational audience (Kougiannou & O’Meara Wallis, 2020, p.355). To understand when hypocrisy is tolerated or creates stakeholder backlash, we turn to the literature which differentiates types of hypocrisy. Some scholars theorize that the type of hypocrisy that arises from inconsistent actions which suggest ulterior motives (e.g., pledging a commitment to address climate change while lobbying against environmental regulation) will be judged more harshly than hypocrisy that arises from inconsistent or insufficient firm outcomes (e.g., falling short of a CSR goal) (Wagner et al., 2020). These distinctions have been regarded as motive- and results-based hypocrisy (Lauriano et al., 2022) and are expected to elicit varying levels of punishment from the organizational audience (Effron et al., 2018; Wagner et al., 2020).

Across six experiments, we find that conflicting CSR information regarding poor or inconsistent results (results-based) as well as actions conveying contradictory motives (motive-based) both cause hypocrisy perceptions, which then elicit harsh social media posts and stakeholder backlash, including moral condemnation. The fact that hypocrisy perceptions mediate the relationship between conflicting CSR information and damaging outcomes is important for two reasons. First, it suggests that even when firms with seemingly genuine motives do not meet CSR goals or report CSR results that conflict with information from external channels, firms can still be labeled hypocrites and suffer a penalty. Second, it demonstrates that individuals punish firms due to perceived hypocrisy and not just because they received negative CSR information from an external source.

In our final experiment, we test whether firm credibility can diminish hypocrisy perceptions when CSR information conflicts, and we find the opposite to be true. While a firm with a weak reputation suffers harsher stakeholder baseline evaluations, the introduction of conflicting CSR information affects a firm with high credibility more than a firm with low credibility. Importantly, the firm with the high credibility suffers more when CSR information conflicts, regardless of whether the hypocrisy is results- or motive-based.

Our paper contributes to the existing literature in several important ways. First, our study findings contribute to the literature on firm signaling related to CSR. We find that when firms signal their values through CSR reporting, social media users will countersignal with claims of hypocrisy in response to conflicting CSR information from external sources. These countersignals on social media correspond to other important stakeholder outcomes including lower interest in purchasing, investing, and employment as well as negative moral judgments in relation to the firm. Importantly, we identify hypocrisy perceptions as a mediating mechanism that explains these negative stakeholder outcomes, which suggests that stakeholder backlash does not simply occur in response to negative CSR information, but that perceptions of hypocrisy stemming from conflicting CSR information lead to stakeholder backlash. Furthermore, researchers have theorized that hypocrisy conveying ulterior motives (motive-based) elicits stronger backlash than hypocrisy conveying poor results (results-based). In contrast to this theory, we find that conflicting CSR information that elicits motive-based as well as results-based hypocrisy perceptions causes not only harsh social media posts but also damaging stakeholder consequences, including moral condemnation. These findings linking both forms of hypocrisy to moral judgments provide evidence that both motive-based and results-based hypocrisy are infused with moral meaning, which has been an area of debate (Effron et al., 2018; Lauriano et al., 2022). We also contribute to the literature on firm credibility by finding that firms with high credibility are met with stronger hypocrisy perceptions and greater stakeholder backlash than those with low credibility. Furthermore, we find corporate credibility amplifies the effects of conflicting CSR on social media and stakeholder backlash, which suggests that firms with high credibility suffer more than firms with low credibility when CSR information conflicts. In contrast to past research, our findings suggest firm credibility serves as a penalty, not a buffer, when CSR information conflicts.

To begin, our first study explores reactions to conflicting and congruent CSR information, which points to hypocrisy concerns and informs the design of the subsequent five experimental studies. Next, we examine the causal links between conflicting CSR information and hypocrisy using study designs that employ both real and fictitious firms, different types of conflicting CSR information (results- and motive-based), and multiple stakeholder behaviors. Since past literature suggests that stakeholders may react differently to different types of corporate hypocrisy, and not all hypocrisy is expected to elicit moral condemnation (Effron et al., 2018; Wagner et al., 2020), our studies include two primary forms of hypocrisy. The first form of hypocrisy, which appears in Studies 2, 5, and 6, is elicited from conflicting CSR information which conveys ulterior or questionable motives and aligns with Lauriano and colleagues’ (2023) concept of motive-based hypocrisy. In Studies 3, 4, and 6, we examine a second form of hypocrisy stemming from information conveying inconsistent or poor results, which aligns with Lauriano and colleagues’ (2023) concept of results-based hypocrisy. Ultimately, we find that both forms of hypocrisy result in harsh social media posts and stakeholder backlash, including moral condemnation. To start, we focus upon the dissemination of CSR information and the signaling it provides.

CSR Information and Signaling

Research on signaling theory has shown that firms communicate information, including information about CSR, to address informational asymmetries that prevent the public from differentiating firms on important dimensions (Berrone et al., 2017; Jakob et al., 2022; Saxton et al., 2019; Turban & Greening, 1997). For example, job seekers, in the early stages of recruitment, cannot gather enough information about a job’s attributes before investing time and energy in pursuing a position, so they look to firms’ reputations as signals about working conditions or other attributes about the job (Cable & Turban, 2003). Relatedly, research also suggests that firms issue CSR reports and engage in other CSR communications, such as social media postings, to signal their values to stakeholders (Turban & Greening, 1997). Firms also use advertisements to signal commitments to social responsibility, such as promoting female empowerment (Sterbenk et al., 2022).

Internal and External Communication Channels

While the valence of CSR information (positive or negative) matters to stakeholders (Lewin & Warren, 2023; Wagner et al., 2009), the source of information (internal or external communication channels) is also likely to affect stakeholder reactions. Perego and Kolk (2012) argue that third-party assurance of firms’ internal CSR reporting improves credibility for stakeholders. Because many consumers may not notice, attend to, or assess harm based on limited negative CSR information (Barnett, 2014), additional information from an external source would likely focus stakeholder attention even more strongly on internal CSR reporting. Thus, information or assurances from external channels are expected to bolster the information from internal channels. This literature, however, focuses on congruent information. We expect conflicting information to have the opposite effect in that conflicting information is likely to draw attention and augment concerns related to the trustworthiness of information received. Therefore, CSR information from external channels that conflicts with internal channels could pose a risk to firm signaling. As a first step in understanding the effects of conflicting CSR information from different channels, we conducted an exploratory study that presented two possible options, conflicting or congruent CSR information, from two sources and probed preferences.

Study 1

Research Design and Participants

338 participants from a Northeastern US university (53% female; mean age = 20.7 years) were asked to evaluate two scenarios involving firm and news reporting of CSR information for a fictitious firm, Nova Inc.

Procedure

Participants were presented with two scenarios regarding a company’s CSR information. In Scenario A, the company issues a positive internal CSR report, including improvements in community investment, carbon footprint, and human rights protection, and a news organization publishes negative information about the company’s decline in the same areas. In Scenario B, both the company and the external source publish negative CSR information related to the same areas of performance. Participants were asked about their preferences for each scenario and then asked to explain their decisions.

Measures

Preference

Participants were asked, “Which scenario is better?” on a 7-point scale from “Scenario A is better” (1) to “Scenario B is better” (7).

Negative feelings

Participants were asked, “Which scenario creates more negative feelings?” On a 7-point scale ranging from “Scenario A creates more negative feelings,” to “Scenario B creates more negative feelings.”

Explanations

Participants were asked to “Explain your thinking when considering which scenario is better or worse.”

Analysis

Using a one-sample t-test, we found that study participants preferred congruent negative information (M = 5.01, SD = 2.14) compared to the scale midpoint (4), which reflected no preference for either scenario, t(337) = 8.7, p < 0.001.

We also found that participants reported stronger negative feelings when receiving conflicting information (M = 2.83, SD = 2.17) compared to the scale midpoint (4), which reflected no difference in feelings for the two scenarios, t(337) = − 9.95, p < 0.001.

To better understand these choices, we analyzed study participants’ explanations of preferences for types of information by coding the most frequently occurring terms in their responses. Study participants preferred the congruent, all-negative information to conflicting information because they felt the firm was trustworthy (31/227, 14%), honest (64/227, 28%), and not lying (74/227, 32%). See Table 1 for illustrations. Those who preferred conflicting information to congruent, all-negative information indicated that it was better to have some sign of improvement than no indication of improvement (42/86, 49%).

When information from both sources aligned, a study participant indicated that “Nova isn’t pretending to be something it’s not” and the firm is signaling they are “honest and have a credible source to prove that they aren’t lying or misleading shareholders.” Likewise, another respondent indicated when the information conflicts, “Nova is issuing a false report and a trusted and respected magazine calling them out would be horrible for the company’s image…” and “Nova is straight out lying or that there is some contradiction within reports, which ruins their reputation and questions Nova’s reliability.” Another respondent noted, “…Nova is being outed as hypocritical…” when the information conflicts. The strong reactions of the study participants suggest that the subject matter of corporate social responsibility itself is morally charged. For example, one respondent indicated, “By lying about doing something good and not doing it shows no integrity which emphasizes no credibility.”

The study respondents’ negative reactions to conflicting CSR information align with conceptualizations of hypocrisy in the academic literature. In our remaining studies, we experimentally examine the relationship between conflicting CSR information on perceptions of hypocrisy, especially when it leads to social media posts, which can reach a broad range of stakeholders.

Hypocrisy

A growing body of recent research has focused on firm hypocrisy, “the belief that a firm claims to be something that it is not” (Wagner et al., 2009, p. 79), and many scholars have sought to categorize hypocrisy into subtypes or patterns which reflect the circumstances in which the perception of hypocrisy arises. Hypocrisy has been described as word-deed misalignment (Effron et al., 2018; Wagner et al., 2009), an inconsistency between CSR messaging and CSR actions (Andersen & Høvring, 2020), a lack of sincere motives (Shim & Yang, 2016), a lack of integrity (Babu et al., 2020), deceptive practices (Higgins et al., 2020; Lauriano et al., 2022; Wagner et al., 2020), and appearing moral without paying the costs (Gillani et al., 2021). Previous research has suggested that when firms overclaim CSR, stakeholders will respond skeptically, doubting the firm’s credibility (Morsing & Schultz, 2006).

Within these, categorizations of hypocrisy are either implicit or explicit associations with morality. Jordan and colleagues (2017) assert that “Hypocrites are disliked because they falsely signal that they behave morally” (Jordan et al., 2017, p. 366). Researchers have attempted to distinguish between inconsistencies that connote a moral deficiency and those that do not. For example, Wagner (2020) discusses distinctions between ‘behavioral hypocrisy,’ which indicates word-deed misalignment, and ‘moral hypocrisy,’ which indicates deceptive practices. Other researchers differentiate between ‘deliberate deception’ and ‘organized’ hypocrisy, which are unavoidable cases when organizational norms and practices conflict with one another (Higgins et al., 2020, p.395), or intentional and unintentional hypocrisy (Snelson-Powell et al., 2020). Relatedly, Kougiannou and O’Meara Wallis (2020) make a distinction between tolerable and intolerable hypocrisy, such that tolerable hypocrisy consists of acts that stakeholders excuse, justify, or otherwise fail to affect stakeholder trust.

Lauriano and colleagues (2022) found moral judgments were concretely tied to hypocrisy perceptions in a qualitative study of employees working for a cosmetics company. The authors identified multiple forms of hypocrisy. The first involved inferring bad motives by the firm (motive-based) while the second entailed insufficient results (results-based). The authors regard moral judgments of the first form as deontological and of the second form as consequential.

Many well-known firms such as General Electric, DuPont, Dow Chemical, General Motors (Ioannou et al., 2023), British Petroleum (Christensen et al., 2020; Hawn & Ioannou, 2016; Wagner et al., 2020), Volkswagen (Higgins et al., 2020; Wagner et al., 2020), Shell, and Nike (Christensen et al., 2020) have experienced clashes in CSR information leading to claims of hypocrisy. Volkswagen’s emissions scandal exemplifies motive-based hypocrisy because the firm claimed a strong commitment to environmental responsibility while systematically cheating on their automobile emissions testing (Wagner et al., 2020). In some cases, results-based hypocrisy can occur despite a firm’s best intentions. TOMS pledged to donate shoes to people in need for every pair bought; however, failure to meet this promise, along with criticism that the donations actually harmed those it claimed to benefit (Hessekiel, 2021), caused hypocrisy perceptions (Short, 2013).

The types of hypocrisy identified by Lauriano et al. (2022) align with the two antecedents, deceptive practices and behavioral inconsistencies, described in Wagner and colleagues’ (2020) conceptual framework of corporate hypocrisy. In work regarding individual reactions to CSR, Wagner and colleagues (2009) presented study participants with either consistent or inconsistent information regarding a firm’s CSR messaging and behavior. The authors find that study participants who receive inconsistent messaging are more likely to perceive corporate hypocrisy (Wagner et al., 2009). While this research does not distinguish between results- and motive-based hypocrisy, or consider social media behaviors, it provides experimental evidence linking inconsistent CSR information and hypocrisy perceptions.

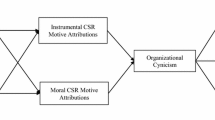

Building on previous work (Lauriano et al., 2022; Wagner et al., 2009, 2020), we theorize that conflicting CSR information leads to hypocrisy perceptions (see Fig. 1 for all hypothesized relationships).

Hypothesis 1: Conflicting CSR information related to firm results or motives causes hypocrisy perceptions.

Countersignaling and Social Media

Signaling theory suggests receivers of firm communications may be inclined to countersignal, or provide feedback to the firm, in an attempt to improve the effectiveness of signaling (Connelly et al., 2011; Dunn & Harness, 2019; Kim & Xu, 2019). Research on this topic has primarily focused on the assumption that signalers ought to attend to countersignals so they know how their signals are being interpreted and, therefore, how to improve them (Connelly et al., 2011).

The signaling literature primarily focuses on signals from a single source, such as the firm, but conflicting reporting on CSR performance, such as news stories, can create competing signals. Stakeholders can perceive conflicting communication negatively (Nyilasy et al., 2013) and respond with their own countersignals sent via social media. As previous research establishes, inconsistency between CSR communications can cause stakeholders to perceive hypocrisy (Wagner et al., 2020), and with social media posts, individuals are able to express these perceptions via countersignals such as calling on other stakeholders to take action, including boycotting an irresponsible firm (Lewin & Warren, 2023). Sharing, liking, and commenting on social media all indicate public perceptions, and serve as countersignals that affect a firm’s CSR-related reputation (Saxton et al., 2019).

Even though behavioral ethics research suggests judgments may not translate into action (DeTienne et al., 2021) and some hypocrisy may be regarded as tolerable (Kougiannou & O’Meara Wallis, 2020), we reflect upon Study 1 findings and assert that when inconsistent CSR information is received by the public, social media users are more inclined to countersignal on social media than those who do not receive conflicting information.

Hypothesis 2: Conflicting CSR information causes social media posts expressing hypocrisy.

In the next study, we consider how conflicting information that signals inconsistent motives affects hypocrisy perceptions as well as behavior on social media, specifically claims of hypocrisy.

Study 2

Our first study revealed that individuals prefer consistent over conflicting information even when the congruent information is negative, and that conflicting information elicits perceptions that align with hypocrisy. Here, we examine this pattern more closely using an experimental design involving a real firm to understand how conflicting information affects social media behavior.

Research Design and Participants

300 participants living in the United States and registered with the Amazon Mechanical Turk program (40% female; mean age = 34.7 years; mean full-time work experience = 12.6 years) were randomly assigned to one of two conditions designed to examine differences in social media response to varying information regarding Caterpillar, Inc (CAT), a US-based manufacturer of construction and mining equipment, diesel and natural gas engines, industrial gas turbines and diesel-electric locomotives (Caterpillar | Company | About Caterpillar., n.d.).

Procedure

All participants viewed a portion of a page from CAT’s online sustainability report, which includes a mission to “provide solutions to support communities and protect the planet” (Caterpillar, 2017). In the external information condition, participants then viewed an edited portion of a real news article reporting that CAT spent over $16 million on political lobbying and almost $1 million in political contributions primarily to block climate action rather than on pro-environmental policies (Goldberg, 2012). Participants in the control condition did not receive a comparable article. All participants then viewed an image of a tweet from Caterpillar’s official Twitter account claiming, “Our solutions help our customers build a better world,” with a link to a video (the link was not active in our study) and were asked how they would respond. Respondents were asked to imagine that they use Twitter and to please indicate how they would respond to Caterpillar Inc. using Twitter. Participants were told, “The tweet above was recently posted by the official Caterpillar Inc. Twitter account. Participants were told that Twitter users had the five options to [1] reply publicly with a message of their own, [2] retweet the post from their own account, with the option to include a public message, [3] mark the tweet with a "like," [4] send a direct (private) message to the writer that cannot be viewed by other Twitter users or [5] take no action. After choosing their response to the information, participants responded to hypocrisy questions and demographic items.

Measures

Initial Attitude

Because Caterpillar is a well-known company, we controlled for initial attitudes by measuring participants’ response to the prompt, “How would you evaluate your attitude toward Caterpillar Inc. (a company that primarily manufactures construction equipment)?” on a 7-point scale (1 = extremely negative to 7 = extremely positive). This prompt occurred before any other information relating to Caterpillar was presented.

Hypocrisy

This was measured on a six-item scale adapted from Wagner and colleagues (2009). Participants responded to statements on a 7-point scale (1 = strongly disagree; 7 = strongly agree) such as, “Caterpillar acts hypocritically,” “Caterpillar puts its words into action,” and “Caterpillar keeps its promises” (reverse coded). For this scale, Cronbach’s alpha was 0.94.

Social Media Post

For retweet, reply, or private message, the study participants were also given the opportunity to write a message. We measured the study participants’ choices to write a message with a dichotomous variable (0 = no, 1 = yes).

The option to write a message is available when participants choose to retweet, reply, or send a private message. Two coders, blind to the experimental conditions, independently coded each tweet message dichotomously for whether it contained a sentiment accusing the company of hypocrisy based upon the items in Wagner and colleagues’ (2009) scale. Interrater agreement was 92% (see Table 2 for illustrations).

Results

An ANOVA, F (1, 299) = 236.02, p < 0.001, demonstrates a difference in perceived hypocrisy between those who received the newspaper article (M = 5.27, SD = 1.39) and those who did not (M = 3.03, SD = 1.11). When we control for initial attitude toward the firm, a statistically significant effect for reading the newspaper article still exists, F (1, 297) = 235, p < 0.001. This provides support for Hypothesis 1, that conflicting CSR information causes hypocrisy perceptions.

Binary logistic regression indicated that individuals who received the newspaper article were 22.4 times more likely to write a message than those who did not, B = 3.11, SE = 0.57, Wald X = 27.74, p < 0.001. The effect remains significant when controlling for initial attitude. Binary logistic regression also shows that participants who only received positive internal information were 2.3 times more likely to mark the tweet with a “like” than to take no action, compared to participants who read the conflicting information, B = 0.85, S.E. = 0.28, X2 = 9.61, p = 0.002.

A second binary logistic regression demonstrates that individuals who receive the newspaper article are 162 times more likely to write a message containing an accusation of hypocrisy compared to writing a tweet message that does not, B = 5.09, SE = 1.27, Wald X = 15.97, p < 0.001. Initial attitude had no effect. This provides support for Hypothesis 2, which predicts conflicting information causes social media posts with expressions of hypocrisy.

Discussion

Our study demonstrates that individuals countersignal on social media with messaging indicating the firm is hypocritical when they receive conflicting CSR information that alludes to ulterior motives. In this study design, we gave study participants the opportunity to do nothing—the least effortful action—in response to positive CSR information as well as conflicting CSR information. These individuals also received the option to privately message the firm. Interestingly, when individuals receive positive CSR information, they choose to publicly ‘like’ the information rather than take no action, and when they receive conflicting CSR information, they take the extra time and effort to write an online, negative public message. In both cases, individuals skip the easier, least effortful step of ‘do nothing,’ and choose to publicly, not privately, direct their comments to the firm. These findings provide important experimental evidence of the desire to countersignal publicly on social media, especially when users perceive hypocrisy.

In the next study, we test our theory in a different context which involves results-based rather than motive-based hypocrisy. We also vary whether the negative or positive CSR information comes from the firm or the news and use a fictitious firm to gain precision in understanding the effects of conflicting information on perceptions of the firm.

Study 3

The purpose of this study is to understand if conflicting information that signals inconsistent results affects hypocrisy perceptions and social media posts when we vary the valence and source of the information. The CSR information includes multiple dimensions of CSR performance (environmental, community-based, and employee-focused) and we use a fictitious firm because past research suggests a firm’s previous reputation or performance can affect the interpretation of CSR information, including hypocrisy perceptions (Ioannou et al., 2023; Mishina et al., 2012; Park & Rogan, 2019).

Research Design and Participants

261 responses from adults living in the United States were collected on the Mturk platform (34.9% female, 239 currently employed, 35.7 mean age, 11.6 mean years of work experience). We tested internal CSR information provided by the company (positive, negative) and CSR information from a news source (positive, negative, no news).

Procedure

For the two internal information conditions, we provided images of several pages of a CSR report for Nova Inc., a fictitious company. Study participants were told the CSR report was published by the company. The report included text descriptions of Nova’s social responsibility initiatives along with graphical representations of social performance in the areas of environment (carbon footprint and hazardous waste), employee engagement, and social investment (charitable giving). In the internal-positive condition, social performance graphs showed positive trends over five years (i.e., carbon footprint and hazardous waste decreased while charitable giving and employee engagement increased). In the internal-negative condition, graphs showed negative trends over five years.

For the external positive condition, participants received an image of a tweet from Forbes magazine claiming that Nova Inc. was on its annual list of the most socially responsible companies. For the external-negative condition, the tweet from Forbes claimed that Nova Inc. was on the list of the most socially irresponsible companies. In the control condition, there was no tweet image.

Firm and news CSR information were presented in random order. After reviewing the material, participants were asked, “Imagine that Nova Inc. is opening a new facility near your home. Please indicate what you would post about #NovaInc on social media….” Respondents typed their responses into a text box. If study participants did not provide a tweet or entered non-codable responses (e.g., copying and pasting the survey directions), they were not included in the analyses. This reduced our sample to n = 185. Next, participants responded to a series of scale measures, attention check questions, and demographic items.

Measures

Hypocrisy

Measured using the same scale as Study 2 (α = 0.82).

Social Media Post

Two independent coders blind to the experimental conditions coded the social media postings for expressions of hypocrisy using the same criteria as Study 2 and reached 97.3% agreement (see Table 2 for illustrations).

Results

To test our hypotheses, the information manipulations were collapsed into two broad categories, conflicting and not conflicting CSR information. An ANOVA indicates that conflicting information affects the level of perceived hypocrisy, F(1, 184) = 4.29, p = 0.04, such that individuals who receive conflicting information perceive the company to be more hypocritical (M = 4.34, SD = 1.56) than those who receive congruent information (M = 3.81, SD = 1.59), providing support for Hypothesis 1.

Using logistic regression, we find that receiving conflicting (versus congruent) information affects decisions to write comments on social media which include expressions of hypocrisy. When participants receive conflicting information, they are 43 times more likely to write a posting that contains accusations of hypocrisy than when they receive congruent information from internal and external channels, B = 2.00, SE = 0.70, Wald X = 8.23, p < 0.001, providing support for Hypothesis 2.

Discussion

Using a study design that involves conflicting CSR information for a fictitious firm from both internal and external information channels, we find that conflicting information leads to greater hypocrisy perceptions as well as expressions of hypocrisy on social media. Similar to Study 2, these findings support the theory that conflicting information elicits strong negative reactions on social media due to hypocrisy perceptions. In contrast to Study 2, this study focuses on results-based hypocrisy instead of motive-based hypocrisy and the findings support the same relationships.

Next, we consider how hypocrisy perceptions relate to stakeholder consequences, specifically moral outcomes, and decisions to purchase, invest, and seek employment. The goal is to understand whether these hypocrisy perceptions and social media posts coincide with damaging stakeholder consequences including moral condemnation.

Stakeholder Consequences

Wagner and colleagues (2020) present a conceptual framework that integrates research involving a range of hypocrisy conceptualizations, including those which arise from behavioral inconsistency or deceptive practices. While they do not propose directional hypotheses, they theorize that different types of hypocrisy perceptions (moral, behavioral) will cause varying stakeholder consequences (behavioral, affective, cognitive) and that moral hypocrisy will cause more damaging outcomes for firms. Here, we expand upon their framework by testing the linkages between different types of hypocrisy and stakeholder consequences that include moral outcomes to make progress in understanding if hypocrisy is infused with moral meaning.

Behavioral Consequences

In Studies 2 and 3, results- and motive-based hypocrisy predicted social media behavior, but this may not correspond to other forms of stakeholder behavior. For example, past research on ‘slacktivism’ suggests that a symbolic action posted to social media on behalf of a cause does not always correspond to additional, more substantive behavior to affect a cause (e.g., Kristofferson et al., 2014). Here, we theorize about stakeholder consequences caused by hypocrisy perceptions arising from conflicting CSR information.

To understand the behavioral linkages between conflicting firm information and stakeholder reactions, we turn to the greenwashing literature which offers a large body of empirical findings. While related research on greenwashing does not specifically address conflicting CSR information, it demonstrates that when firm reporting exaggerates or misrepresents actual performance, individuals lose trust in a firm, reduce purchasing intentions, hold less favorable brand attitudes, and decrease perceptions of corporate credibility (Gosselt et al., 2019; Torelli et al., 2020).

In related research, Babu et al. (2020) found that hypocrisy perceptions reduce employees’ voluntary participation in their firms’ social responsibility programs. In experimental studies, Lewin and Warren (2023) found negative CSR information affected stakeholder intentions to buy, invest, or seek employment with a firm. While past research does not explicitly capture the role of conflicting CSR information from internal and external channels on stakeholder decisions, past findings suggest that conflicting CSR information would negatively affect stakeholder behavior.

Affective Consequences

In line with Wagner and colleagues’ (2020) framework, we expect hypocrisy to elicit affective responses, especially those grounded in moral emotions.

Jordan and colleagues (2017: 357) explain, “…hypocrites inspire moral outrage because they dishonestly signal their moral goodness—that is, their condemnation of immoral behavior signals that they are morally upright, but they fail to act in accordance with these signals.” Wagner et al. (2020) also assert that hypocrisy perceptions relate to a range of “negative emotional reactions such as anger, contempt, and disgust…because moral hypocrisy and hypocrisy attributions involve the moral character of the firm” (Wagner et al., 2020, p. 390). In support of this assertion, Laurent and colleagues (2014) experimentally tested the role of hypocrisy on desire to punish criminals and found hypocritical criminals received harsher punishments and that moral emotions (anger and disgust) mediated the relationship. We expect conflicting CSR information to elicit moral outrage toward the firm, due to increased perceptions of hypocrisy.

Cognitive Consequences

Conflicting CSR information is expected to cause hypocrisy perceptions that also tie to negative cognitions toward the firm. Several empirical studies suggest negative cognitions arise from perceptions of greenwashing and hypocrisy (Lauriano et al., 2022; Scheidler et al., 2023; Wagner et al., 2009). Within cognitive consequences, we expect harsh moral judgments to be important cognitions affected by hypocrisy perceptions arising from conflicting CSR information. As discussed previously, several scholars within the hypocrisy literature assert that hypocrisy is infused with moral meaning (Effron et al., 2018; Lauriano et al., 2022) because hypocrisy connotes a false signal related to morality (Jordan et al., 2017). While past researchers differentiate results-based from motive-based hypocrisy and expect results-based hypocrisy to fall outside the realm of moral judgment or condemnation, our results from Study 3 suggest that even results-based hypocrisy elicits strong reactions on social media, which suggests that both forms of hypocrisy elicit negative moral evaluations.

Taken together, substantial findings from related literatures suggest conflicting CSR information will cause stakeholder backlash, and we predict hypocrisy will explain the effect.

Hypothesis 3: Hypocrisy perceptions mediate the relationship between conflicting CSR information and stakeholder consequences (behavioral, affective, cognitive) such that the greater the hypocrisy perceptions arising from conflicting CSR information, the harsher the stakeholder consequences (behavioral, affective, cognitive).

In the next three studies, we broaden the scope of effects from conflicting CSR information to consider not only social media posts but also other stakeholder behaviors (investment, purchasing, employment), affect (moral outrage), and cognition (moral judgments). We examine these relationships in the context of hypocrisy stemming from inconsistencies in results (Study 4) and motives (Study 5). In Study 6, we combine both forms of hypocrisy and consider the role of firm credibility.

Study 4

Using a study design that captures inconsistencies in results, we empirically test the relationship between conflicting CSR information, hypocrisy perceptions, as well as stakeholder outcomes.

Research Design and Participants

107 responses from English-speaking adults were collected on the Prolific platform (73% United Kingdom, 11% Canada, 5% United States; 65% female, 70% currently employed, 33.4 mean age, 11.3 mean years of work experience).

Procedure

All participants received several graphs from a CSR report for Nova Inc., a fictitious company. Study participants were told the CSR report was published by the company. The graphs represented improved social performance over a four-year period in the areas of community investment in education, promoting international human rights, and reducing carbon impact. After viewing positive CSR information from an internal channel, approximately half of the participants were randomly assigned to receive several graphs from Forbes magazine’s Sustainability Report for Nova. These graphs, though fictitious, were labeled with names of real government and non-profit organizations as sources of information (e.g., ClimateAccountabilityInstitute.org) and showed year-over-year declining social performance in corresponding categories (Investment in Local Communities, Corporate Human Rights Benchmark Score, and Carbon Footprint).

Participants were then asked to indicate what they would post about the company on social media and responded to three stakeholder behavior measures described below. To diminish the likelihood that respondents would provide uniform responses across these dependent variables, stakeholder behavior questions used different response formats. For example, the investor question focused upon choosing a percentage of retirement funds to invest in a company rather than a scale. Participants also completed scale items on hypocrisy and moral outrage.

Measures

Social Media Post

Two independent coders blind to the experimental conditions coded the social media postings for expressions of hypocrisy using the same criteria as previous studies and reached 90% agreement. The disagreements were resolved by a third independent coder. (see Table 2 for illustrations).

Moral Judgment

The social media posts were also coded for expressions of negative moral judgments against the firm. Two coders agreed on 93% of cases and disagreements were resolved by a third coder.

Hypocrisy

Measured using the same scale as Studies 2 and 3 (α = 0.96).

Investment

Study participants were presented with the following scenario: “Imagine your employer offers a retirement savings plan and you are allowed to divide your retirement savings among several company stocks. Please indicate the percentage of your savings that you are willing to invest in each of the following companies. You are allowed to give a specific company 0% but remember, your percentages must add to 100%. Nova Inc. was listed among a group of six other companies, specifically Johnson & Johnson, Microsoft, Patagonia, IBM, Wal-Mart and Kraft. Although participants responded to this prompt for seven firms, interest in Nova served as the primary measure for investor behavior.

Employment

Study participants were asked, “Imagine you are looking for a new job. How interested are you in employment with Nova Inc.? (1 = Not at all interested to 7 = Very interested).

Consumption

Study participants were asked, “If you had the opportunity, how likely would you be to purchase or boycott products from Nova Inc.?” Participants expressed their interest in purchasing from the target firm using a 7-point scale item (1 = Boycott to 7 = Buy).

Moral Outrage

Following De Kwaadsteniet and colleagues (2013), six scale items were used to measure negative, anger-related, moral emotions (i.e., angry, frustrated, irritated, indignant, agitated, and hostile). Participants responded to the prompt, “To what extent did you experience the following emotions toward Nova Inc.?” on a seven-point scale (1 = Not at all; 7 = A great deal). For this scale, the Cronbach’s alpha was 0.96.

Results

We conducted three separate mediation analyses using the Process Macro in SPSS (Hayes, 2017, model 4) to examine whether hypocrisy mediates the relationship between the type of information and stakeholder behaviors. Participants receiving the conflicting information perceived greater hypocrisy compared to the control group who received only internal information, b = 7.72, p < 0.001, which provides support for Hypothesis 1. There is also an indirect effect of information type on investment (b = 7.8, 95% CI [3.77 – 13.21]), employment interest (b = 1.37, 95% CI [0.69 – 2.12]), consumption interest (b = 1.10, 95% CI [0.52 – 1.78]), moral outrage (b = 0.76, 95% CI [0.28 – 1.28]), moral judgment (b = − 1.12, 95% CI [− 2.9 – -0.16]), and social media posts (b = − 1.05, 95% CI [− 3.10 – 0.01]) through the mediator, hypocrisy perceptions, providing support for Hypothesis 2 (social media posts) and Hypothesis 3 (stakeholder consequences).

Discussion

This study demonstrates that hypocrisy elicits not only countersignaling through social media posts, which include claims of hypocrisy, but also negative moral judgments (cognitive), moral outrage (affective), and stakeholder backlash in terms of lower interest in consumption, purchasing and investment (behavioral). These stakeholder consequences provide empirical support for Wagner and colleagues’ (2020) framework by establishing a broad range of backlash. Importantly, this study suggests even results-based hypocrisy is infused with moral meaning and is not tolerated.

Because the effectiveness of signaling and countersignaling may relate to credibility of the channel of information (Gosselt et al., 2019; Lee et al., 2017; O’Neil & Eisenmann, 2017), we gauge credibility of the firm and news outlet as sources of information in the next study as well as stakeholder backlash in relation to motive-based hypocrisy.

Study 5

In this study, we examine whether conflicting CSR information signaling inconsistent motives affects hypocrisy perceptions, social media posts, and subsequent stakeholder consequences. In order to disentangle information credibility from source credibility, we measured credibility of the firm and news outlets as sources of information at the start of the experiment. This allowed us to control for initial impressions of the firm and news as credible sources of information prior to receiving the CSR information.

Research Design and Participants

156 adults living in the United Kingdom (68.6% female, mean age = 38.3 years, mean full-time work experience = 17.5 years) participated in a Qualtrics survey on the Prolific platform where they were randomly assigned to one of two conditions.

Procedure

Participants read about a fictitious company called Antrapod Inc., which was identified as a global manufacturer of construction equipment and were asked about the credibility of its reporting as well as the credibility of Forbes Magazine. Participants then received a page reportedly from Antrapod’s 2020 Sustainability Report showing sustainability goals such as increasing water management strategies and decreasing operations waste (based on Caterpillar in Study 2). Approximately half of participants also received a page from a fictitious Forbes article accusing Antrapod of political spending to block action on climate change. Participants then viewed an Instagram post allegedly from Antrapod and were asked for their response. Participants were given the option to “Leave a comment,” “Share with one or more members of my social network and include the following message” or “Other (If you choose this option, you must explain your choice in the next question).” Participants were then asked questions regarding hypocrisy perceptions, moral outrage, stakeholder behaviors (consumption, investment, employment), and moral judgments.

Measures

Internal Source Credibility

We measured source credibility of the firm by asking, “How credible would you find the information in this company’s sustainability report?” and provided a 7-point scale (1 = Extremely non-credible to 7 = Extremely credible). This prompt occurred before any other information related to Antrapod was presented.

External Source Credibility

We measured source credibility of the external information by asking, “How credible would you find the information in Forbes Magazine?” and provided a 7-point scale (1 = Extremely non-credible to 7 = Extremely credible). This prompt occurred before any other information from Forbes was presented.

Social Media Post

Responses for both “leave a comment” and “share” were coded by two independent coders using the same criteria as Study 2. Interrater agreement was 89.8%, and a third coder reconciled differences between coders. (See Table 2 for illustrations.)

Hypocrisy

Measured using the same scale as Studies 2 – 4 (α = 0.95).

Moral Outrage

Measured using the same scale as Study 4 (α = 0.96).

Purchasing

Study participants were asked, “How likely are you to purchase products from Antrapod?” 1 = Extremely unlikely, 7 = Extremely likely).

Investment

Study participants were asked, “How likely are you to invest in Antrapod stock?” (1 = Extremely unlikely to 7 = Extremely likely).

Employment

Study participants were asked, “How likely are you to seek employment with Antrapod?” (1 = Extremely unlikely to 7 = Extremely likely).

Moral Judgments

To measure moral evaluations of the firm, we adapted a measure from Hafenbrädl and Waeger (2021) and asked for study participants’ agreement (1 = Strongly disagree, 7 = Strongly agree) with statements such as “Antrapod exhibits moral behavior.” and “Antrapod is an ethical company.” (α = 0.96.)

Results

For all six dependent variables, we conducted mediation analysis in SPSS using the Process macro (Hayes, 2017, model 4) to examine whether hypocrisy mediates the relationship between conflicting CSR information, social media posts, and stakeholder backlash. Controlling for perceived firm credibility and external information credibility, these effects remained statistically significant.

Conflicting information has an indirect effect on posting to social media with accusations of hypocrisy through the mediator, hypocrisy perceptions, b = 1.88, 95% CI [1.01 – 4.34], providing support for Hypothesis 2, that conflicting information causes social media posts that call a firm out for hypocrisy. Conflicting information affects hypocrisy perceptions, compared to the control group, b = 1.31, p < 0.01, providing support for Hypothesis 1, which predicts that conflicting information elicits hypocrisy perceptions. Conflicting information has an indirect effect on moral judgments (b = − 0.1.26, 95%CI [− 1.62 – − 0.91]), moral outrage (b = 1.2, 95% CI [0.80 – 1.65]), employment interest (b = − 0.85, 95% CI [− 1.24 – − 0.50], investment (b = − 0.71, 95% CI [− 1.13 – − 0.38]), and purchase interest (b = − 0.92, 95% CI [− 1.30 – − 0.61]), all through the mediator, hypocrisy perceptions. Collectively, these six sets of mediation analyses also provide support for Hypothesis 3, which predicted hypocrisy perceptions mediate the relationship between conflicting information and stakeholder consequences (behavioral, affective, cognitive).

Discussion

In this study, we find conflicting CSR information conveying motive-based hypocrisy causes harsh social media posts and stakeholder backlash, including moral outrage, moral judgments, and lower interest in investments, purchasing, and employment. We disentangled the role of credibility of information channels from hypocrisy perceptions by controlling for the credibility of the firm and news outlet as sources of information and found that the credibility of these channels did not affect the proposed relationships.

In the next study we shift our focus to the effect of firm credibility on hypocrisy perceptions stemming from the conflicting CSR information. We also test the two forms of hypocrisy in the same study to determine if motive-based hypocrisy causes stronger backlash than results-based hypocrisy.

Firm Credibility

As discussed earlier, firms communicate CSR information to address informational asymmetries and signal commitment to CSR. Past research indicates that the corporation’s longstanding reputation serves as a lens for interpreting this CSR information, especially when conflicting information is received by the organizational audience (Invernizzi et al., 2022; Ioannou et al., 2023; Lauriano et al., 2022; Wagner et al., 2009). More specifically, a firm’s credibility, which is grounded in firm reputation, is a predictor of how stakeholders such as customers (Ioannou et al., 2023; Wagner et al., 2009), shareholders (Invernizzi et al., 2022), and employees (Lauriano et al., 2022) respond to inconsistent CSR information which conveys hypocrisy.

At the individual level, Effron and colleagues (2018, p. 63) describe how possessing a reputation grounded in moral status can establish “moral credentials,” which provide a reputational buffer against morally questionable behavior in future. Similarly, organizational theorists consider the role of past firm reputation in the interpretation of adverse firm events. Credibility increases corporate reputation (Eberle et al., 2013), which can buffer the effects of an adverse event (Shim & Yang, 2016). More specifically, a firm with a reputation for strong character, which entails a sense of integrity or trustworthiness, will provide a filter for understanding negative events such that the negative events will be shaped or influenced by the firm’s reputation (Mishina et al., 2012). Firms with a favorable reputation for character are expected to better cope with adverse events, especially those related to morality, than firms with unfavorable character reputations (Ioannou et al., 2023; Mishina et al., 2012; Park & Rogan, 2019). For instance, Ioannou et al. (2023) examined hypocrisy reflecting firms’ green product innovation and US customer satisfaction and found that a strong firm capability reputation, measured using Fortune’s Most Admired Corporations, can mitigate the negative effect of greenwashing on customer satisfaction.

While some nuances exist in the nature of the adverse event (uncontrollable events elicit different reactions than controllable events), the social psychology and organization theory literatures view reputation as a favorable attribute that should dampen the ill effects of hypocrisy arising from conflicting CSR information.

Hypothesis 4: Corporate credibility moderates the relationship between conflicting CSR information and hypocrisy perceptions such that low firm credibility augments the negative effects of conflicting CSR information on hypocrisy perceptions, which leads to harsher social media posts and stronger stakeholder backlash when compared to a firm with high credibility.

Study 6

Using a study design that uses real firms, we empirically test the relationship between firm credibility, types of hypocrisy, hypocrisy perceptions, and stakeholder consequences, including moral emotion, moral judgment, negative social media posts, and interest in purchasing, investing, and employment.

Research Design and Participants

450 responses from English-speaking adults were collected on the Prolific platform (94% United Kingdom, 4% United States; 50% female, 42.9 mean age, 21.1 mean years of work experience).

Procedure

Study 6 is a 2 (low/high firm credibility) by 3 (motive-based/results-based/no conflicting information) experimental design. Participants viewed materials for a high-credibility firm (Clorox) or a low credibility firm (Monsanto). These firms were chosen as they represented #1 and #98, respectively, on the 2000 Axios Harris Poll of 100 firm reputation rankings and share the SIC classification of Industrial Applications and Service. While some previous research has used Fortune America’s Most Admired Corporations list to proxy firm reputation (e.g., Ioannou et al., 2023), the Axios Harris Poll includes rankings on specific areas of reputation including affinity, ethics, citizenship, and culture, which are particularly relevant to corporate social responsibility. A pre-test with 313 business school students (mean age = 19.7 years, mean work experience = 2.7 years) indicated a significant difference in credibility perceptions of these two firms.

First, participants read, “Several years ago, {The Clorox Company/Monsanto} was ranked as {Excellent/Very Poor} in the following areas on the Axios Harris Poll Reputation Rankings, a national poll about the reputations of American companies: Affinity, Ethics, Citizenship, Culture.” Participants were asked whether their target firm was credible. Participants then viewed fictitious graphs from the target firm’s CSR report (the same graphs used in Study 4) representing improved social performance over a four-year period. After viewing positive CSR information from the firm, approximately one-third of the participants were randomly assigned to the motive-based hypocrisy condition, and read, “Forbes Magazine, an independent, US business magazine, recently added {Clorox/Monsanto} to its annual list of America's most socially irresponsible companies because their investigation found that the company has spent over $3 million lobbying government officials to fight new laws regulating carbon emissions, despite their widely publicized corporate social responsibility goals.” Another one-third of participants were randomly assigned to the results-based hypocrisy condition and read, “Forbes Magazine, an independent, US business magazine, recently added {Clorox/Monsanto} to its annual list of America's most socially irresponsible companies because their investigation found that the company has failed to make any progress on its widely publicized corporate social responsibility goals.” The final one-third of participants received no external information, and this served as the control condition. Participants then responded to dependent variable items, mediating variable items and demographic items.

Measures

Social Media Post

While viewing the fictitious charts from the CSR report, the study participants were asked, “Suppose {Clorox/Monsanto} decided to post the following charts on INSTAGRAM. What comment would you post in response to the firm's INSTAGRAM?”.

Two independent coders blind to the experimental conditions coded these responses for accusations of hypocrisy (0 = no hypocrisy, 1 = presence of hypocrisy) and agreed on 84% of cases. The disagreements were resolved by a third independent coder.

Hypocrisy

Measured using the same scale as Studies 2 through 5 (α = 0.96).

Moral Outrage

Measured using the same scale as Studies 4 and 5 (α = 0.97).

Moral Judgments

Measured using the same scale as Study 5 (α = 0.96).

Investment

Study participants were presented with the following scenario: “Imagine your employer offers a retirement savings plan and you are allowed to divide your retirement savings among several company stocks. How much would you invest in {Clorox/Monsanto}?” (1 = None of my savings to 7 = A lot of my savings).

Employment

Study participants were asked, “Imagine you are looking for a new job. How likely are you to seek employment with {Clorox/Monsanto}?” (1 = Extremely unlikely to 7 = Extremely likely).

Consumer interest

Study participants were asked, “If you had the opportunity, how likely would you be to purchase or boycott products from {Clorox/Monsanto}?” Participants expressed their interest in purchasing from the target firm using a 7-point scale item (1 = Extremely unlikely to 7 = Extremely likely).

Results

We conducted six separate moderated mediation analyses using the Process Macro in SPSS (Hayes, 2017, model 7) to examine whether hypocrisy mediates the relationship between the type of information and stakeholder behaviors, and whether firm credibility moderates the effect of conflicting information on hypocrisy perceptions. All results maintain 95% levels of confidence when we control for initial attitude toward the target firm.

For all six models, results-based hypocritical information interacts with firm credibility to affect hypocrisy perceptions, compared to the control group, b = 0.65, p = 0.02, and motive-based hypocritical information interacts with firm credibility to affect hypocrisy perceptions, compared to the control group, b = 0.85, p < 0.01, providing support for Hypothesis 1, that conflicting information predicts hypocrisy perceptions. There were no findings of statistically significant differences in hypocrisy perceptions when comparing results-based to motive-based information.

Results-based hypocrisy (compared to the control group) has an indirect effect, through the mediator, hypocrisy perceptions, on posting an accusation of hypocrisy to social media (b = 0.67, 95% CI [0.17 – 1.26]), moral judgments (b = − 0.67, 95% CI [− 1.19 – − 0.15]), moral outrage (b = 0.52, 95% CI [0.14 – 0.93]), employment interest (b = − 0.62, 95% CI [− 1.09 – − 0.15]), investment (b = − 0.48, 95% CI [− 0.84 – − 0.12]), and boycotting (b = 0.65, 95% CI [0.16 – 1.15]). Similarly, motive-based hypocrisy (compared to the control group) has an indirect effect on social media posts (b = 0.88, 95% CI [0.34 – 1.51]), moral judgments (b = − 0.88, 95% CI [− 1.43 – − 0.33]), moral outrage (b = 0.69, 95% CI [0.25 – 1.13]), employment interest (b = − 0.82, 95% CI [− 1.32 – − 0.31]), investment (b = − 0.66, 95% CI [− 1.03 – − 0.27]), and boycotting (b = 0.85, 95% CI [0.31 – 1.4]). These analyses provide support for Hypothesis 2, which predicted conflicting information causes accusations of hypocrisy in social media posts, and Hypothesis 3, which predicted hypocrisy perceptions mediate the relationship between conflicting information and stakeholder consequences (behavioral, affective, cognitive).

Hypothesis 4 predicted that firm credibility moderates the relationship between conflicting information and hypocrisy perceptions such that hypocrisy perceptions would be stronger for a low credibility firm; however, our results show the opposite. As described above, the model shows a statistically significant interaction effect on stakeholder backlash, through the mediator, hypocrisy perceptions, for firm credibility and conflicting information for both results- (b = 0.65, p = 0.02) and motive-based (b = 0.85, p < 0.01), compared to the control group. Test results also show the effects of the conflicting information on the mediator, hypocrisy perceptions, at both levels of firm credibility: The conditional effect of results-based information (compared to the control group) on hypocrisy perceptions for the low credibility firm, b = 0.62, is notably smaller than the conditional effect at the high-credibility firm, b = 1.3. Similarly, the effect of motive-based information on hypocrisy perceptions is smaller for the low credibility firm, b = 0.52, than the high-credibility firm, b = 1.27.

Discussion

The findings suggest that both forms of conflicting information (results- and motive-based) elicit damaging responses from stakeholders, which is important for understanding differences in hypocrisy perceptions. Across all six stakeholder consequence dependent variables—moral outrage (affective), moral judgments (cognitive), social media, employment, investment and boycotting (behavioral)—we find a moderated mediation effect, such that when CSR information conflicts, participants react with increased hypocrisy perceptions, which in turn cause social media posts claiming hypocrisy, more negative moral judgments, higher moral outrage, lower employment interest, investment decisions and increased intention to boycott. According to our findings, a credible firm is more adversely affected by conflicting CSR information than a firm with low credibility. That is, for the higher credibility firm, conflicting CSR information causes a bigger difference in stakeholder consequences compared to the lower credibility firm.

General Discussion

Firms communicate their CSR performance in order to address informational asymmetries, but contradictory information from external channels can elicit perceptions of firm hypocrisy. When this occurs, countersignaling through social media can amplify claims of hypocrisy. Here we examine when hypocrisy perceptions cause countersignaling on social media and how this behavior aligns with other forms of stakeholder backlash (behavioral, affective, cognitive) including moral condemnation. Past research has differentiated between types of firm hypocrisy and theorized about the probable effects on the organizational audience. Some argue hypocrisy that arises from seemingly deceptive actions will be judged more harshly than hypocrisy that arises from insufficient or inconsistent firm performance (Higgins et al., 2020; Snelson-Powell et al., 2020; Wagner et al., 2020). These distinctions have been regarded as motive- and results-based hypocrisy (Lauriano et al., 2022) and are expected to elicit varying levels of punishment from the organizational audience. Across six experiments, we find both results- and motive-based hypocrisy elicit harsh social media posts, and other stakeholder backlash, including moral condemnation. Across all studies, we consistently find that study participants are not simply punishing firms for negative CSR information received through external channels but that the conflict in CSR information gives rise to hypocrisy perceptions that we link to harsh social media posts and negative stakeholder outcomes. Importantly, our experiments suggest that even when firms with seemingly sincere motives do not meet CSR goals, they can still be perceived as hypocrites and are punished. In our final experiment, we tested whether firm credibility can buffer the negative effects of conflicting CSR information and we find the opposite to be true. While a firm with low credibility possesses lower baseline stakeholder evaluations, conflicting CSR information affects firms with low credibility less than firms with high credibility. Firms with high credibility suffer more when CSR information conflicts, regardless of whether the hypocrisy stems from results or motives. These findings suggest support for the theory that firm credibility acts as a penalty, not a buffer, for conflicting CSR information. In the remainder of this section, we consider these results in the context of past theory and propose directions for future research.

Hypocrisy & Morality

While researchers have theorized substantially regarding different types of hypocrisy, such as motive-based versus results-based (Lauriano et al., 2022), behavioral versus moral (Wagner et al., 2020), deliberate deception versus organized hypocrisy (Higgins et al., 2020), unintentional versus intentional hypocrisy (Snelson-Powell et al., 2020), and tolerable versus intolerable hypocrisy (Kougiannou & O’Meara Wallis, 2020), our research suggests hypocrisy stemming from either conflicting results or motives both cause harsh social media posts and stakeholder backlash. One reason for distinguishing between types of hypocrisy is to better understand how hypocrisy relates to moral evaluations. Some scholars explicitly align hypocrisy with specific philosophic traditions. For example, Lauriano et al. (2022) tied hypocrisy perceptions to ethical theories by aligning moral judgments in response to motive-based hypocrisy with deontology and moral judgments regarding results-based hypocrisy to consequentialism. Wagner et al. (2020) distinguish between types of hypocrisy as ‘moral’ or ‘behavioral’ and suggest stronger stakeholder backlash in response to the moral form of hypocrisy.

Disentangling the relationship between moral evaluation and hypocrisy is important to academic and practitioner audiences because the organizational audience may possess unrealistic expectations regarding firm consistency and treat all forms of hypocrisy the same. To demonstrate the gap and its implications, we turn to a study by Carlos and Lewis (2018), which suggests firms do not always publicize third-party environmental certification for fear of stakeholder backlash if the firm were to experience a misstep that contradicted the certification. Relatedly, Hafenbrädl and Waeger (2021) found hypocrisy perceptions are higher when a firm claims to perform CSR activities for moral reasons, as opposed to performing CSR activities for instrumental reasons. In both cases, the firms are choosing to engage in socially minded actions, beyond those that are legally mandated, but fear harsher stakeholder reactions than if they did not have certification or were purely motivated by instrumental reasons. It is important to the CSR movement that organizational audiences distinguish between firms that voluntarily engage in social activities with good motives and those that have bad motives, or do not engage in such activities at all. Future research should consider interventions that reorient the organizational audience’s expectations related to CSR such that well-intentioned firms that fall short of expectations do not elicit the same punishment as those with ulterior motives.

The organizational crisis literature could provide guidance on how to reorient organizational audiences in response to adverse events and provide communication strategies for firms that experience hypocrisy due to falling short of expectations or goals. Situational crisis communication theory (SCCT) suggests that the type of crisis, the firm’s relevant history, and previous reputation predict how stakeholders will respond to the crisis and the best strategy to protect organizational reputation in the future (Coombs & Holladay, 1996). Research on self-disclosure of negative information indicates consumers respond more favorably when firms self-disclose negative events if the firm has a weak reputation (Fennis & Stroebe, 2014). This finding aligns with research on ‘honest hypocrites’ (Jordan et al., 2017), whereby hypocritical behavior does not elicit moral condemnation when individuals self-disclose their hypocrisy. By self-disclosing socially irresponsible behavior, a firm may be able to generate greater stakeholder trust. Future research should test these tactics in response to conflicting CSR information to determine if self-disclosure can mitigate hypocrisy perceptions and the effects on social media and other stakeholder reactions.

Credibility

Through our investigation, we find evidence that not only extends, but also counters, past findings on corporate credibility. While we find that firms with low credibility incur harsh social media posts and stakeholder backlash, these firms are also less affected by conflicting CSR information than firms with high credibility. Unlike past studies which suggest that high credibility will buffer the damaging effects of conflicting CSR information, we find that the highly credible firm is more negatively affected by conflicting CSR information. Our finding aligns with research which has noted, “a good reputation could have a boomerang effect in a company’s bad times….” (Shim & Yang, 2016, p.69). Ultimately, the organizational audience may believe the information shared by a credible firm while disregarding CSR information from a low credibility firm.

The effect of credibility on hypocrisy may also reflect the controllability of CSR activities. Adverse events can be categorized into those that are controllable by a firm and those that are uncontrollable (Park & Rogan, 2019). Whether a firm’s credibility will mitigate the effects of an adverse event is affected by the degree to which the firm could have prevented the event by engaging in better practices (Park & Rogan, 2019). “If an adverse event was caused by factors within the firm’s control, such as inadequate maintenance, the buffering effects of character reputation diminish” (Park & Rogan, 2019, p. 572). In the realm of CSR, the clash of information may be regarded as a controllable event, which would explain why a good reputation harmed, rather than helped, the firm. Our studies involve an external source reporting on a firm’s CSR activities in a negative light, which to some extent could be regarded as an adverse event that is perceived to be controllable by the firm.

Controllability may inform the difference between the present findings and those of Ioannou et al. (2023), who examined firms’ green product innovation and US customer satisfaction and found that firm credibility mitigated hypocrisy related to green product innovation. Their study used large datasets, which allowed for the examination of relationships across a wide range of firms. The methodology, however, prevented causal inferences, and their follow-up experiment, which measured perceived hypocrisy, did not account for firm reputation. In contrast, our approach allows for experimental manipulation of conditions, which allows for causal inferences, but lacks a broad range of firms and forms of CSR information. Ideally, future research will combine methodologies to better understand how firm credibility and CSR reporting interact and combine to influence hypocrisy perceptions, especially with an appreciation for the controllability of CSR information and signaling.

Limitations

One of the main limitations of our experimental design is that it only involves two sources of CSR information, while a real social media environment entails information from many different sources, often at the same time. Our experimental design, however, allows us to control other factors so that we can confirm the basic understanding of how conflicting information affects hypocrisy perceptions and, in turn, likely stakeholder outcomes.

It is possible that even though our studies addressed two forms of hypocrisy (results- and motive-based), all of our studies may have entailed ‘intolerable’ hypocrisy (Kougiannou & O’Meara Wallis, 2020), which is why all types of hypocrisy caused stakeholder backlash. Future research should test how much inconsistency in CSR information, if any, the organizational audience will accept before reacting negatively to the firm.

Conclusion

Across six studies, we find that firms are likely to be accused of hypocrisy through social media posts when internal and external CSR information conflicts and that these social media posts align with other stakeholder backlash (lower purchasing, investing, and employment interest), including moral outrage and negative moral judgments. Importantly, stakeholder backlash occurred when conflicting CSR information demonstrates either results- or motive-based hypocrisy, and was more severe when firm credibility was high. These findings suggest support for the theory that firm credibility acts as a penalty rather than a buffer for certain adverse events.

References

Andersen, S. E., & Høvring, C. M. (2020). CSR stakeholder dialogue in disguise: Hypocrisy in story performances. Journal of Business Research, 114, 421–435. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.08.030

Avery, T. (2021). Coach to stop destroying damaged returns after TikTok video of slashed purses goes viral. USA Today. https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/nation/2021/10/14/coach-stop-destroying-merchandise-after-viral-tiktok-video/8453093002/

Babu, N., De Roeck, K., & Raineri, N. (2020). Hypocritical organizations: Implications for employee social responsibility. Journal of Business Research, 114, 376–384. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.07.034

Barnett, M. L. (2014). Why stakeholders ignore firm misconduct: A cognitive view. Journal of Management, 40(3), 676–702.

Berrone, P., Fosfuri, A., & Gelabert, L. (2017). Does greenwashing pay off? Understanding the relationship between environmental actions and environmental legitimacy. Journal of Business Ethics, 144(2), 363–379. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-015-2816-9

Cable, D. M., & Turban, D. B. (2003). The value of organizational reputation in the recruitment context: A brand-equity perspective. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 33(11), 2244–2266.

Carlos, W. C., & Lewis, B. W. (2018). Strategic silence: Withholding certification status as a hypocrisy avoidance tactic. Administrative Science Quarterly, 63(1), 130–169. https://doi.org/10.1177/0001839217695089

Caterpillar | Company | About Caterpillar. (n.d.). https://www.caterpillar.com/en/company.html. Accessed 17 February 2023

Caterpillar 2017 Sustainability Report. (2017). http://reports.caterpillar.com/sr/report/strategy.php. Accessed 7 July 2018

Christensen, L. T., Morsing, M., & Thyssen, O. (2020). Timely hypocrisy? Hypocrisy temporalities in CSR communication. Journal of Business Research, 114, 327–335. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.07.020

Coach: Designer brand admits destroying its own bags. (2021). BBC. https://www.bbc.co.uk/newsround/58846711

Coach. (n.d.). Coach|Our Planet. https://www.coachoutlet.com/coach-responsibility-planet.html. Accessed 7 July 2023

Connelly, B. L., Certo, S. T., Ireland, R. D., & Reutzel, C. R. (2011). Signaling theory: A review and assessment. Journal of Management, 37(1), 39–67. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206310388419

Coombs, W. T. (2007). Protecting organization reputations during a crisis: The development and application of situational crisis communication theory. Corporate Reputation Review, 10(3), 163–176. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.crr.1550049

Coombs, W. T., & Holladay, S. J. (1996). Communication and attributions in a crisis: An experimental study in crisis communication. Journal of Public Relations Research, 8(4), 279–295. https://doi.org/10.1207/s1532754xjprr0804_04

De Kwaadsteniet, E. W., Rijkhoff, S. A. M., & Dijk, E. V. (2013). Equality as a benchmark for third-party punishment and reward: The moderating role of uncertainty in social dilemmas. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 120(2), 251–259. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.obhdp.2012.06.007

DeTienne, K. B., Ellertson, C. F., Ingerson, M. C., & Dudley, W. R. (2021). Moral development in business ethics: An examination and critique. Journal of Business Ethics, 170(3), 429–448. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-019-04351-0

Dunn, K., & Harness, D. (2019). Whose voice is heard? The influence of user-generated versus company-generated content on consumer scepticism towards CSR. Journal of Marketing Management, 35(9–10), 886–915. https://doi.org/10.1080/0267257X.2019.1605401

Earl, J., & Kimport, K. (2011). Digitally enabled social change: Activism in the internet age. New Media & Society, (5).

Eberle, D., Berens, G., & Li, T. (2013). The impact of interactive corporate social responsibility communication on corporate reputation. Journal of Business Ethics, 118(4), 731–746. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-013-1957-y

Effron, D. A., O’Connor, K., Leroy, H., & Lucas, B. J. (2018). From inconsistency to hypocrisy: When does “saying one thing but doing another” invite condemnation? Research in Organizational Behavior, 38, 61–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.riob.2018.10.003