Abstract

It has been argued that organizational structures (the way tasks are defined, allocated, and coordinated) can influence moral agency in organizations. In particular, low values on different structural parameters (functional concentration, specialization, separation, and formalization) are said to foster an organizational context (allowing for relating to the goals and output of the organization, moral deliberation, and social connectedness) that is conducive to moral agency. In this paper, we investigate the relation between the organizational structure and moral agency in the case of a.s.r. (a large Dutch insurance company). While our empirical results fit the thesis that low values on structural parameters positively relate to moral agency, they also refine our understanding of the influence of structural parameters. In particular, our data suggest that the influence of functional concentration not only depends on whether it is low, but also on the type of criterion used for identifying business units; they suggest that the specific organizational context may put a limit to lowering design parameters and points at several non-structural factors that have an influence on the relation between structure and moral agency. In all, the paper contributes to a more detailed understanding of the conditions conducive to moral agency in organizations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

A growing number of authors have approached moral agency in organizations from a virtue ethics point of view (e.g., Beadle & Knight, 2012; Hartman, 2008; Mion et al., 2023; Moore, 2005a, 2005b; Nicholson et al., 2020; Sison et al., 2018; Solomon, 1992, 2004; 2012; Vriens et al., 2018; or Weaver, 2006). A key aspect of this approach is that moral agency in organizations relies on the development and exercise of the moral character of organizational members (Weaver, 2006): i.e., based on their moral character, organizational members may understand and deal with moral issues related to their work and further develop their moral character (Vriens et al., 2018). Against this background, several authors have argued that organizational structures (i.e., the way tasks are defined, related, and coordinated, cf. Mintzberg, 1983) influence the development and exercise of organizational members’ moral character. In particular, it has been argued that some types of structures are problematic for, while others are supportive of developing and exercising one’s moral character in organizations. MacIntyre (1985), for instance, famously attacks bureaucracies as highly unsupportive structures that severely undermine virtuous action in organizations (see also Jos, 1988; Luban et al., 1992). Other authors have proposed characteristics of supportive structures (cf. Vriens et al., 2018 for a review). For instance, Moore (2005a, 2005b) proposed that employees should be “able to exercise self-control and self-direction” in their jobs (p. 251). Likewise, Bernacchio and Couch (2015) stressed that structures should enable ‘participatory governance,’ and Schwartz (2011) argued that ‘virtuous agency’ requires a low degree of formalization. Beadle and Knight (2012) proposed designing ‘meaningful jobs’ and Breen (2007, 2012) argued that jobs should contain “complex and coherent tasks” and allow workers “to have an overview of the entire work” (Breen, 2012, p. 621).

Building on and extending the suggestions of the above authors, Vriens et al. (2018), combine virtue ethics and organizational design theory into a detailed model describing supportive structural arrangements for moral agency. These ‘virtuous structures’ (Nicholson et al., 2020; Vriens et al., 2018) require that so-called structural ‘design parameters,’ like unit grouping, specialization, centralization, and formalization, should have ‘low’ values. The main argument is that structures having low values on these parameters help to install three relevant contexts for developing and exercising the moral character of organizational members. That is, such structures help to provide (1) a ‘teleological context’ enabling organizational members to be in touch with the organization’s goals and output, (2) a ‘deliberative context’ allowing organizational members to think about and act on the moral aspect of their work, and (3) a ‘social context’ serving as a background for moral agency, and in which organizational members jointly discuss and reflect on the moral aspect related to organizational goals and output and their own task-related contribution to them (Vriens et al., 2018, p. 676).

While Vriens et al. (2018) draw together much of the existing literature into a conceptual model on how structures might support moral agency, their work as well as those of other related authors (e.g., Beadle & Knight, 2012; Breen, 2012; or Moore, 2005a, 2005b) has been largely theoretical. Empirical research showing that and how certain structures are indeed supportive of ‘virtuous’ moral agency is rare (a thought shared by Nicholson et al., 2020). Given this lacuna, the contribution of this paper is to present and discuss the case of a large Dutch insurance company (a.s.r.) with the aim of empirically assessing the main thesis that certain structural arrangements are conducive to moral agency in organizations (as specified by the framework reflecting current thought on conducive structures, discussed by Vriens et al. 2018). As we will discuss, our empirical data allow us to illustrate and support, to supplement, as well as to indicate limitations of the framework. And, as a result, we contribute to the discussion about the (structural) conditions needed to support the exercise and development of the moral character of moral agents in organizations, a relevant question in the application of virtue ethics to business (cf. Moore & Beadle, 2006). To realize our contribution, we proceed as follows. First (section "Structural Conditions for ‘Virtuous’ Moral Agency."), we discuss the thesis that certain structural arrangements are conducive to moral agency. Next, in section "Methodological Considerations and Case Organization," we will introduce the case organization, discuss why a qualitative single case study seems appropriate, and present our methodological approach. As it will turn out, our case organization, the Dutch insurance company a.s.r., seems to be suitable for at least two reasons: (1) the company aims to deliver a responsible contribution to society by means of its insurance products and investment policies and explicitly encourages individual moral agency to realize this contribution, and (2) it has implemented measures aimed at creating a conducive (infra)structure that explicitly encourages individual moral agency as we will detail further below. In section "Results," we present our findings on whether and how the structural arrangements found in the company support moral agency. Finally (section "Discussion and Conclusion"), we discuss the empirical findings: i.e., we discuss how they support the main thesis, toward which limitations of the framework by Vriens et al. they point, and how they can be used to propose alterations to this framework.

Structural Conditions for ‘Virtuous’ Moral Agency

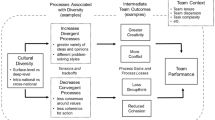

As it is the goal of this paper to empirically assess the thesis that the structure of an organization may condition ‘virtuous moral agency,’ we need to explain what we mean by this type of agency, organizational structures, and how structures may (co-)condition virtuous agency. In this section, we briefly go into these three issues. As the model by Vriens et al. (2018) is based on and incorporates extant literature to elaborate the above thesis, and as it seems to be the most detailed model elaborating the thesis, we will use their model as a point of departure. In Fig. 1, we depict the influence of structures on moral agency, and below we will briefly discuss the models’ three elements and relations.

How structures may affect moral agency (based on Vriens et al., 2018)

Virtuous Moral Agency in Organizations

Virtuous moral agency (approached from an (Aristotelian) virtue ethics point of view) is described as developing and exercising our moral character in the context of living a fulfilled life (Aristotle/Barnes 1984). An Aristotelian approach to virtuous moral agency revolves around the concept of ‘eudaimonia,’ i.e., living a fulfilled life as a human being. In virtue ethics, living a fulfilled life means that we, as human beings, should strive to perfect ‘our most characteristically human capacities’ (i.e., our capacity for reason and related to that, our capacity for desire) in the best possible way; into virtues as Aristotle conceptualizes it (Aristotle/Barnes, 1984). Perfecting these capacities is seen as the goal of our life as humans; making virtue ethics a teleological ethical theory. Two virtues are particularly relevant for discussing ethical conduct: moral virtues and practical wisdom. Moral virtues dispose us to desire to perform the ‘right’ (re)action, (the mean—a proper reaction relative to some over- and under-reaction, Aristotle/Barnes, 1984) in specific situations with respect to emotional and desiderative dimensions. Moreover, well-developed moral virtues dispose us to desire a proper reaction for its own sake. Practical wisdom is about knowing what it means to live a fulfilled life in general, and enables us to construct, choose, and act in an ‘appropriate’ (morally good) way in particular circumstances. Practical wisdom and moral virtues constitute our ‘moral character’ (e.g., Sherman, 1989) and “…come together in making choices about how to live a fulfilled life in particular circumstances, guiding our everyday moral life by providing us with a desire to do the right thing and the capacity to act in accordance with this desire” (Vriens et al. 2018, p. 674). To summarize—an agent with a well-developed moral character desires to do the right thing—for its own sake (based on the agent’s moral virtues) and knows what it means to realize this desire here-and-now, in particular circumstances (based on the agent’s practical wisdom).

Moral agency entails that, during our lives, we ‘exercise’ our moral character (dealing with the everyday moral issues we encounter) and further ‘develop’ it (by socially and individually learning about the consequences and appropriateness of our moral behavior).

Discussing moral agency in the context of ‘doing a job’ requires explaining what exercising and developing our moral character as organizational members entails. Here, Vriens et al. (2018) refer to Solomon (2004), who holds that we are members of two communities at once: the organizational community and society. It is proposed that we, as members of the ‘organizational community’ (Solomon, 2004, p. 1025) exercise and develop our moral character “with respect to other members of the organizational community” and, as members of society we exercise and develop our moral character “with respect to the organization’s environment—the society an organization contributes to” (Vriens et al., 2018, p. 675). So, virtuous moral agency in the context of doing one’s job entails desiring and doing the right thing for other organizational members and for members of society.

It might be worth adding that, as several authors (Koehn, 2020; Kristjánsson, 2022; Mion et al., 2023) point out, virtue ethics has become a relevant ethical theory for approaching moral agency in organizations, and has “equalled or even surpassed deontology and utilitarianism as the theory of choice within academic business ethics” (Kristjánsson, 2022, p. 43). Koehn (2020) explains that it is “a well-worked out account of choice and ethical judgement […] that relates choice to principles, perception, life goals/commitment, deliberation and character, and to the larger context in which human agents act” (Koehn, 2020, p. 243). As Vriens et al. (2018) note, business ethicists using a virtue ethics approach value the development and exercise of agents’ moral character in specific contexts (which entails making such choices and ethical judgments and learning from them) over the mere compliance to rules (cf. Hartman, 2008). Given the rise of virtue ethics in approaching moral agency in organizations, understanding the organizational conditions (among which the organizational structure) that are conducive to the virtue ethics informed development and exercise of agents’ moral character have also gained in importance (cf. Moore & Beadle, 2006).

Three Conducive Contexts for Virtuous Moral Agency

To be able to exercise and develop one’s moral character in organizations, several authors have turned to organizational conditions enabling work (e.g., Bernacchio & Couch, 2015; Breen, 2012; Moore & Beadle, 2006; Weaver, 2006). Building on these authors, Vriens et al. (2018) distinguish the following three organizational contexts that are relevant for supporting the exercise and development of one’s moral character and agency in organizations: a teleological, deliberative, and social context.

Teleological Context

The teleological context refers to organizational conditions that enable organizational members to be (a) aware of “the goals and output of the organization in relation to its societal contribution” (Vriens et al., 2018, p. 676), and (b) aware of “how their [own] tasks relate to this contribution” (ibid, p. 676). The authors argue that organizational conditions creating this awareness are relevant for moral agency in organizations. Knowledge about the actual goals and output of the organization helps organizational members to see whether they (as organizational members) are contributing to “just or doubtful goals,” valuable or invaluable products or services, or “to unintended harmful or positive side effects” (Vriens, 2018, p. 676), to reflect on them and judge whether these goals and outputs are worth pursuing. Moreover, knowledge about the connection of one’s own specific job to realizing the organization’s goals and output serves as a background for context-specific moral agency. It helps to direct one’s actions to realize just ends, valuable products and services, or positive side effects, or to do something to correct unjust goals, invaluable output, or harmful side effects. As Vriens et al. argue, organizational moral agency requires ‘being in touch with goals and output’ for “if organizational goals [and actual output] aren’t clear to organizational members, they don’t know what they are contributing to – and they necessarily remain clueless about whether their [own jobs’] contribution makes a difference to society” (ibid, p. 676). The observation that organizational moral agency requires an awareness of the organization’s goals and output has been acknowledged (e.g., Breen, 2012; Grant, 2007; MacIntyre, 1985; Moore, 2005b; Vriens et al., 2018). In all, the teleological context refers to organizational conditions that help organizational members to be(come) aware of organizational goals and output (e.g., in terms of products and services and of (un)intended side effects) and of the connection of their own task to this in a trustworthy way.

Deliberative Context

The ‘deliberative context’ refers to organizational conditions that allow organizational members to deliberate about and implement job-related actions. This entails that organizational conditions should support their job-related decision-making and action, which involves that they can reflect on their job-related actions, understand and see the possible and actual consequences of their actions. It also entails that they can devise job-related actions, can make informed choices about performing an action can implement and adjust actions as they see fit, that they see the actual consequences of their actions so that they can learn about proper actions in similar (future) situations. Several authors point out that this deliberative context is relevant for organizational moral agency. For instance, Vriens et al. (2018) point out that besides knowledge about organizational goals and output, and knowing that one can contribute to them by means of one’s job, moral agency in organizations also requires that organizational members reflect on, devise, implement, and learn about ‘appropriate’ moral actions in specific work-related circumstances. This entails that they can reflect on the potential moral consequences of several possible actions in a specific work-related context, and based on that devise and implement a morally appropriate action. It also entails that they become aware of and can reflect on the actual moral consequences of their actions, so as to be able to adjust them, if needed, and to learn and further develop their moral character (cf. Vriens et al., 2018, p. 677, also Grant, 2007; Luban et al., 1992; Nicholson et al., 2020; Solomon, 2004). These requirements for context-specific moral deliberation and action are described as the ‘deliberative context’ for moral agency (Vriens et al., 2018, p. 677). It is worth noting the difference between the teleological and deliberative context: while the teleological context provides organizational members with an awareness of the goals and output of the organization and an awareness of how one’s job is connected to that, the deliberative context allows organizational members to actually device and carry out ‘appropriate moral actions’ in specific job-related situations, and to learn from them. Nevertheless, deliberation about (and implementation of) ‘appropriate’ actions in organizations depends, of course, on knowledge about goals and output of the organization, as such actions are meant to contribute to them.

Social Context

The social context in organizations refers to organizational conditions that provide members “with the opportunity to be an active part of a social network” (p. 678) serving as a background for moral development, deliberation, and action. The relevance of being a part of a social network for virtuous moral agency is central to virtue ethics. Indeed, as a social being; as a ‘zoon politicon’ as Aristotle puts it (Aristotle/Barnes, 1984), developing and exercising a moral character is not possible without being in contact with others (Aristotle/Barnes, 1984, MacIntyre, 1985, 2009; Solomon, 2004). The social context serves as a background in several ways. First, as MacIntyre (1985, 2009) emphasizes, the moral development of individual agents is always placed in a particular social and historical context, with its own “debts, inheritances, rightful expectations and obligations [that] constitute the given of [one’s] life, [one’s] moral starting point” (MacIntyre, 1985, p. 220). Not only are we part of a specific social setting with its own moral particularities, we also develop our moral character against this social background that provides us with examples of proper and improper conduct, and in which our own conduct is corrected or reinforced by praise and blame. This is not only relevant in the process of our ‘overall’ moral development, but also holds for the specific practices or organizations (with their specific moral particularities) we are part of. Second, as our moral behavior revolves around the consequences for others, it is itself inherently social. As MacIntyre (1999) puts it: a social setting is crucial for moral agency as “[…] accountability to others, participation in critical practical enquiry and acknowledgment of the individuality both of others and of oneself” (p. 317) depend on it. Being in touch with others, then, enables us to become aware of and acknowledge these consequences. It can also help us to reflectively discuss the relevant moral values in particular situations with others and to jointly discuss proper actions.

For organizational members, this implies that their moral reflection, action, and learning are always embedded in a specific (organizational) social setting with its own moral particularities, having a specific set of values and mechanisms for the social dissemination and stabilization of values and acceptable conduct (such as examples of ‘proper conduct,’ or formal or informal systems of praise and blame—cf. Weaver, 2006, or Bernacchio, 2018, for similar mechanisms). Moreover, for virtuous moral agency, the organizational social context requires that organizational members are in touch with each other so as to be able to see the consequences of their own conduct, and to jointly reflect on and discuss values and actions. As Vriens et al. (2018) write, providing organizational members with a social context enables them to discuss, socially reflect on, and judge appropriate moral values related to being an organizational member, the moral appropriateness of actual and intended organizational goals and output, as well as their moral understanding of specific work-related situations and actions. This social network thus “serves as a background for our moral awareness, and our moral deliberation, judgment, and reflection as we deal with moral issues” (p. 678) while performing our jobs.

In sum, it has been argued that ensuring the realization of a teleological, deliberative, and social context may help to support organizational members to exercise and develop their moral character while performing their jobs. It is relevant to note that the three contexts are separate, yet related in their support for moral agency; they each provide necessary but by themselves insufficient organizational conditions for moral agency. Moreover, they are three separate, yet related parts of a constellation of preconditions for moral agency (cf. Moore & Beadle, 2006). Moore and Beadle (2006) identify three preconditions for moral agency in organizations: virtuous agents, a conducive mode of institutionalization, and a conducive environment. The three contexts further specify the conducive mode of institutionalization, in that they specify organizational requirements for moral agency in organizations.

Although the contexts are geared toward different necessary aspects of organizational moral agency, all three are needed for ‘complete’ moral agency. Deliberation and implementation of ‘morally sound organizational actions’ require knowledge about goals and output (as morally sound organizational actions should be geared at realizing morally just organizational goals and output). Moreover, we learn about, we discuss, and we reflect on the appropriateness of organizational values, goals, and output and of our own actions, with other members of our organizational network. Being embedded in this social network enables us to refine our moral character by learning about shared values and appropriate actions. Hence, the three contexts amplify each other to support moral agency. So, what we want of organizations is that they install all three contexts. However, different organizational infrastructural arrangements can be implemented that help to improve the three different contexts to a different extent. For instance, ICT applications in a bureaucratic organization can help to inform organizational members about organizational goals, but these applications may not empower members to deliberate on or adjust their own actions to better realize these goals, nor may they foster a social community in which one reflects on goals and output. In a similar vein, organizational members working in a team in a highly specialized process, i.e., who perform only a fraction of the complete process, may be given some regulatory authority to device and adjust their actions. This may improve the deliberative context up to some point: members of the team may for instance decide to stop doing their own work to help other team members. This may foster team-internal moral behavior (helping others) but may come at the cost of realizing final services to clients if they are not aware of how stopping the work relates to the output of the organization. Similarly, one may hope to install a social context, by allowing members more time and a better space to have lunch together. However, if they are not aware of organizational goals and output, and if they are not allowed to device and implement actions (differing from their normal activities), this social context does not help to reflect on goals and output, or on devising or implementing certain actions.

So, organizations may implement infrastructural arrangements that realize the three contexts to a different extent. In fact, Vriens et al. (2018) argue that different structures may contribute to do so. Indeed, their main idea—which is the basis of this study, is that different structures vary in realizing the three contexts and that only certain structures contribute to realizing all three contexts to a considerable extent. We will turn to this issue in the next section. As a last remark, we must add that structures are not the only factor facilitating (or hindering) the realization of organizational contexts for moral agency. Leadership, culture, reward systems to name a few other factors (see also many reviews, like Treviño et al., 2006, 2014; Treviño & Nelson, 2017) may also contribute to installing these contexts—yet structure is the focal aspect of this study.

Structural Arrangements Influencing Moral Agency in Organizations

Summarizing much of the extant literature, Vriens et al. (2018) argue that organizational structures may facilitate or hinder the realization of the three contexts for moral agency described above. In particular, it is argued that structures with low values on four so-called structural design parameters (job-specialization, functional concentration, separation, and formalization) facilitate the realization of these contexts, while structures with high values on these parameters hinder their realization. In this section, we will briefly introduce the design parameters, and in section "Effects of Structural Parameters on the Required Organizational Contexts for Moral Agency," we will summarize the influence of high and low values of the design parameters on the three conducive contexts.

Job-Specialization

In line with other authors (e.g., Mintzberg, 1983; de Sitter, 1994), Vriens et al. (2018) define the design parameter job-specialization as the degree to which tasks are split up into smaller sub-tasks. This can refer to operational and to regulatory tasks. If specialization of operational tasks is high, the primary process consists of many small sub-tasks with a short cycle time that together produce the output of the primary process. A prototypical example of much specialization in operational work is a conveyor belt structure where a product has to pass many different workstations that only perform a very small part of the complete transformation process. Specialization can also refer to regulatory tasks: i.e., to tasks with a small regulatory scope (e.g., a regulator responsible for a small part of the primary process). So, there are actually two versions of this parameter: operational and regulatory specialization (cf. Mintzberg, 1983). If the value of job-specialization with respect to operational tasks is low, operational jobs cover a large part of the production process—ideally, they are tied to a product or service from beginning to end (cf. Nadler & Tushman, 1997). If the value of job-specialization related to regulatory tasks is low, regulatory tasks have a broad scope (e.g., covering a large part of the production process).

Functional Concentration

Building on others (cf. Nadler & Tushman, 1997; de Sitter, 1994; de Sitter & den Hertog, 1997), Vriens et al. (2018) understand functional concentration as the relation between operational activities and ‘order-types’ (an order-type is defined as the demand for a particular type of product or service). If functional concentration has a high value, operational activities are related to potentially all order-types (e.g., a nurse seeing all types of patients, or someone in a furniture factory carrying out one task (e.g., sawing wood) for all types of furniture). If it has a low value, operational activities are only related to a subset of (or even one) order-type(s), for instance, a nurse who sees only a few (types of) patients or a worker in a furniture factory only performing operational activities for one type of chair. High functional concentration (and high operational job-specialization) can often be found in organizations having many departmental units (‘silos’) in which tasks are clustered based on the same type of activity, skill, or knowledge (cf. Mintzberg’s (1983) idea of functional grouping) and in which the members of these departments see many different order-types. Organizations with low functional concentration often have ‘parallel production units’ (production flows or teams) dedicated to a few order-types, in which workers have broad tasks.

Separation

A third design parameter, as Vriens et al. (2018) explain, is ‘separation’ (de Sitter, 1994; a related idea by Mintzberg is centralization)—the degree to which the regulation of some job or process is separated from (is not part of) performing that job or process. Separation leads to assigning the regulatory aspect of a task to a separate task. For example, if an operational manager is responsible for dealing with problems in some operational job (e.g., readjusting a machine because it is no longer working properly), the regulatory task ‘dealing with operational problems’ is not part of the job of those operating the machine, but assigned to the manager. Separation not only holds for operational jobs but can also apply to regulatory jobs—leading to a hierarchy of managers. So, a high degree of separation introduces a hierarchy of managers whose job it is to regulate other jobs (in the end, this hierarchy regulates the primary processes). A low degree of separation, by contrast, leads to tasks in which operational activities are performed and that also have the regulatory potential with respect to these operational activities. Organizations with a low degree of separation may have ‘self-contained teams’ (cf. de Sitter, 1994; Galbraith, 1974; Nadler & Tushman, 1997) which are responsible for carrying out operational processes realizing some product or service and also have the regulatory potential to deal with disturbances themselves, can participate in adjusting the infrastructure needed for their work (regulation by design) and can, to some extent, reset goals with respect to their output.

Formalization

The fourth design parameter, formalization, is defined as “the degree to which jobs must follow specified rules or procedures” (Vriens et al., 2018, p. 684). In organizations with a high level of formalization ‘‘[…] a codified body of rules, procedures or behavior descriptions is developed to handle decision and work processing’’ (Pierce & Delbecq, 1977, p. 31), which are also, typically, strictly enforced. Organizations with a low level of formalization often have less rules and procedures governing work and see less to strict enforcement of rules and procedures. High formalization is often related to compliance-induced moral decision making, while lower formalization is more related to moral decision-making based on ‘integrity’ (cf. Sharp-Paine, 1994; Treviño & Weaver, 2001). It should be remarked that ‘low formalization’ does not mean that an organization has no rules or procedures related to performing one’s work. Indeed, in many contexts, rules and procedures may help guide one’s work. Formalization becomes too high if rules and procedures become too restrictive; i.e., come at the cost of discretionary decision making and action, and impose a framework of discipline and compliance (cf. Foucault, 1977; MacIntyre, 1985; or O’Neill, 2002), in which doing the right thing means following rules.

Effects of Structural Parameters on the Required Organizational Contexts for Moral Agency

In their article, Vriens et al. (2018) discuss how high values of the four design parameters may hinder the realization of the three required contexts for moral agency, while low values offer opportunities for their realization. In Table 1, we provide an overview of how they conceptualize the effect of parameters on the three contexts.

The main argumentation, summarized in Table 1, is that high values on parameters limit the potential for moral agency, while low values may install the contextual conditions for organizational members to exercise their moral agency. In fact, to facilitate the discussion, the authors discuss two prototypical structures (with ‘extreme’ constellations of parameter values): a bureaucratic or Tayloristic organization (high values on all parameters) and a ‘horizontal organization’ (low values), but their main argument is that structures with low values on the design parameters better enable moral agency. The authors also warn that it is important to note that this does not imply that high values exclude moral agency, nor that low values guarantee it. Rather, by creating organizational structures with low parameter values, organizations create conditions for moral character development by co-providing the three contexts.

A high value on specialization and functional concentration (see first and second row Table 1), for example, reduces organizational members’ opportunity and capability to see how their own small tasks are related to the broader organizational output and goals, i.e., the teleological context. Workers performing only jobs with a short cycle time related to many different products or services; or chefs controlling only a tiny part of the production process have a hard time seeing beyond their small jobs and hence appreciating the organizational goals and output—let alone understanding how their job relates to them (cf. Breen, 2012; MacIntyre, 1985). A restricted overview of how one’s own task relates to the overall organizational output and goals, also limits the capability to see and reflect on the consequences of one’s own actions (deliberative context). When a high level of separation and formalization exists on top of this, not only organizational members’ chance and capability to reflect on moral actions in their work is restricted but also their possibility to devise and implement ‘appropriate moral actions’ (and to choose to select other actions, if required). Additionally, by imposing a regime of discipline and obedience to the rules and procedures, formalization may not only hinder discretionary moral decision making and action, it may also install the ‘bureaucratic self.’ MacIntyre (1985) warns us about, for whom doing the right thing means following the rules. For the social context, a high value on specialization and functional concentration implies that organizational members often have little “opportunity to be an active part of a social network” (Vriens et al., 2018, p. 678). They are thus little enabled to discuss and socially reflect on their moral values and their moral understanding of situations; with high values on separation and formalization, not only the reflection as such is restricted but also the potential to come up with and implement proper actions.

In contrast, following Beadle and Knight (2012), Bernacchio and Couch, (2015), Breen (2012), Moore (2005a, 2005b), and Vriens et al. (2018), it can be argued that organizations that have, for example, a low level of specialization and functional concentration (see first and second row Table 1), provide jobs and tasks that cover broader parts of organizational processes, allowing them to be more in touch with goals and outputs of an organization (teleological context). This comes along with an improved opportunity for organizational members to reflect and deliberate on context-specific moral issues (deliberative context). Organizational members are facilitated in becoming aware of the potential moral consequences of alternative courses of action in specific circumstances and reflect upon them. With low parameter values on separation and formalization, they can also devise, select, and implement a ‘morally appropriate’ action—i.e., one bringing about the desired moral consequences. A low level on specialization (as well as on the other parameters) also affects the social context: they offer better opportunities for being an active part of a social network. Such organizations often have ‘self-contained’ teams of workers responsible for broad operational tasks (covering a large part of the order process; low specialization) and often team members have overlapping tasks (low specialization). Besides, they have the decision authority to deal with many problems themselves (low separation) as they see fit—i.e., not bound by many formal rules and procedures (low formalization). Again, low formalization does not mean that there are no rules or procedures. Rather, it means that on the one hand rules and procedures may act as a background guiding moral agency, and at the same time offer the freedom for discretionary moral agency and reflection about the rules and procedures themselves (cf. O’Neill, 2002, for a similar interpretation of a ‘proper’ level of formalization in the context of professional conduct). As many team members have overlapping tasks and work together on the same order, communication about anything connected to these orders is much easier than when everybody has specialized activities. Developing and exercising one’s moral character can thus become a socially embedded endeavor.

By explicating the link between structural parameters and the required organizational contexts for moral agency, Vriens et al. (2018) use organization design theory to provide a detailed account of the proposition that structures may enhance or hinder moral agency in organizations. However, as we noted in the introduction, this framework remains mainly conceptual: an empirical assessment of (the relations stated in) the model is lacking. In fact—as Moore (2012) states, empirical studies assessing conceptual frameworks related to ‘virtues in business’ in general are sparse, and the same holds for empirical studies probing into the relation between structures and virtuous moral agency (Mion et al., 2023; Nicholson, et al., 2020). Given this lack of empirical grounding of the relation between structures and moral agency, we set out to conduct a case study and find out whether and how findings do or do not support the framework, or give rise to alterations.

Methodological Considerations and Case Organization

To answer the call for more empirical research on how organizational structures may (co-) condition virtuous moral agency (Nicholson, et al., 2020; Vriens et al., 2018;), we present (mainly) qualitative empirical data on the case of the Dutch insurance company a.s.r.. Before we explain how the case study was designed and conducted (section "Method"), we address our choice to employ a qualitative single case study to research a more-or-less developed framework (section "Why a Qualitative Single Case Study?"; inspired by Moore (2012)), and provide information about the specific case organization and its selection for our study (section "Why Select a.s.r. as Case Organization?").

Why a Qualitative Single Case Study?

Moore (2012) explains that qualitative research using thick descriptions is often appropriate for studying virtues in organizations. It opens up the possibility to explore the moral decisions made in organizations along with their accompanying in situ context-dependent deliberation, motivations, and conditions. Given the context dependency, which is also a characteristic of case study research (Yin, 1994), Moore (2012) goes on to note that “the case study method emerges as perhaps the most appropriate approach for exploring virtue in business organizations” (p. 368). In our study, we wanted to find out whether the way employees made moral decisions was supported by certain structural characteristics, as proposed by the framework. As part of this endeavor tracing actual moral decisions to structural conditions required an in-depth understanding of the specific decisions they made and probing into the way these decisions were related to the organizational context. Given the context-specific nature of the decisions and their conditions, a qualitative case study seems appropriate (cf. Yin, 1994).

We explore how certain structures may support moral agency by using the single case of a.s.r.. Drawing on others, Moore defends selecting a single case when it provides one with “opportunities for unusual research access” (Eisenhardt and Graebner, 2007; in Moore, 2012, p. 678) or if it allows one “to gain insights that other organizations would not be able to provide” (Siggelkow, 2007; in Moore, 2012, p. 678). These reasons also apply to our study: because other organizations having the same favorable characteristics (see below for an elaboration of these characteristics) for our purposes are hard to find, and as a.s.r. was willing to provide us access, selecting a.s.r. as a (single) case seemed warranted.

We use a case study to research a framework that has already been (more-or-less) established. Case studies are often employed in inductive research and if one already has a reasonably robust theoretical framework other methods may seem more appropriate (Moore, 2012). In dealing with this issue, we could, following Moore, point at the fact that the framework used is “at an early stage of development with [no] empirical testing already carried out and so case study research is important in exploring and illustrating concepts more fully in an attempt … to begin to confirm, refute or modify the theory” (Moore, 2012, p. 679). Indeed, this reason for selecting a case study fits our goal well. It also fits the idea of paradigm-driven qualitative research, one possible route for employing qualitative research in business ethics as Reinecke et al. (2016) discern.

As indicated above, we approach our research question (empirically exploring the relation between the organizational structure and moral agency, informed by an already developed framework) by means of a qualitative case study. Yet, as we will discuss below, our assessment of the relation between structure and moral agency is complemented by quantitative material, providing us with additional information on structures and the three contexts in the case of a.s.r..

Why select a.s.r. as Case Organization?

To gain an empirical understanding of whether and how structures might affect moral agency, it is helpful to select an organization in which moral agency is explicitly encouraged and which already has a structure with low parameter values. Such an organization would logically provide a suitable context for studying the framework’s main thesis that moral agency is supported by specific (low parameter) structural conditions. Such organizations are, unfortunately, difficult to find; especially the combination of an organization explicitly encouraging moral agency and having a ‘proper’ structure. The Dutch insurance company a.s.r. seems to fulfill this combination of demands, and access to the case company therefore provided us with a rare opportunity.

The specific case company seems appropriate, as it is explicitly encouraging moral agency as a means for delivering its societal contribution. After having been involved, with other insurance companies, in the so-called ‘profiteering policy’-scandal (De Telegraaf, 2016; Dekker, 2017; Vereniging Woekerpolis.nl, n.d.) in the early years of 2000, a.s.r. now stresses its ‘responsible’ contribution to society and has built up a considerable reputation as a company paying attention to moral behavior and social responsibility. The organization aims to be a “valuable member of society” and it declares that it “has a public duty to act as a responsible insurer and investor” (company website). Company documents indicate (see Table 2), for example, that a.s.r. sets out to realize a positive impact on society (e.g., by highlighting specific financial products such as mortgages for starters on the housing market, by initiatives aimed at the prevention of diseases and integration of the unemployed) and to reduce negative impacts on society (e.g., by a specific investment-policy favoring sustainable business). The company has reframed its societal goal from selling insurances to “helping clients to share risks and build up capital,” and although the cynical observer may have doubts about such slogans as mere window-dressing, several company-independent sources (see first row Table 2) such as its very high ranking on the Fair Finance Guide seem to suggest that the company is indeed paying attention to its societal impact.

a.s.r. regards the promise of serving clients in a proper way by making sure that it only sells products that clients really need (instead of just ‘pushing’ products), as key to sustainable viability in the insurance market. The CEO explained that the business model now revolves around “really making sure that our services are in the best interest of the client”—in the sense that they truly help clients to share risks and build up capital and the sense that they are societally (socially and environmentally) sound. This promise has provided a.s.r. a competitive edge and is seen as key to both economic and societally responsible survival. To deliver this promise, a.s.r. has launched nationwide campaigns (in which it explains its responsible focus—campaigns that besides reputation-building also open up a ‘window of vulnerability’ as every breach of this promise may immediately run counter to the advocated responsible business model), and it has built up an infrastructure around the promise (see Table 2 for examples). In all, a.s.r. seems to be an insurance company highlighting responsible behavior as a core aspect of its societal contribution, prompts its employees to ‘do the right thing’ for its clients, and has installed several means to ensure that it lives up to its promise of being a responsible player in the insurance business.

What is of special interest for selecting a.s.r. as a case company is that it also seemed to have installed a structure supporting employees to develop their moral dedication and engage in associated behavior. Although we will discuss this structure in some more detail below, we may already note that a.s.r. has several relatively autonomous business lines dedicated to types of products and or clients; it has a relatively low level of formalization, it has organized its work in teams and it added potential for operational regulation to tasks in order to allow employees to reflect on the moral dimensions of their actions and alter decisions when deemed necessary. Hence, the structural characteristics of a.s.r. are in line with those of the Vriens et al. framework and seem to further warrant the choice of a.s.r. as a case organization.

The case of a.s.r. seems to provide a suitable context for relating organizational moral agency to the organizational structure, as it explicitly encourages moral agency and has a supportive structure. However, it should be noted, though, that at a.s.r. moral agency is promoted by several mechanisms—besides the structure. For instance, as we will discuss below, leadership, the organizational culture, or the installed reward systems also impact moral agency at a.s.r.. This is, however, no reason for not selecting a.s.r., as long as the structure can be reasonably identified as a mechanism co-supporting moral agency. Our strategy to do so was as follows: we first explored whether and how a.s.r. seeks to promote moral agency (thus uncovering both the relevance of moral agency and mechanisms for it). This first inductive step affirmed that moral agency at a.s.r. is encouraged and that the structure along with other mechanisms is employed for this encouragement. In a second step, we focused on the structure as a supportive mechanism. Informed by theory relating structures to moral agency, we first set out to tie the structure of a.s.r. to the three contexts conducive to moral agency. Next, we tried to trace dealing with several moral issues to the structure of a.s.r. In doing so, we hope to provide an argumentation tying moral agency to the structure of a.s.r.—even though moral agency is promoted by other factors as well. In the method section below, we will discuss our research approach in more detail.

Method

In our empirical research, we first focused on exploring whether and how a.s.r. seeks to stimulate moral agency. This inductive exploration was meant to provide general information about moral agency at a.s.r. and the (structural) conditions it implemented to support it, in part to affirm that a.s.r. was indeed a suitable case organization. In the second step, we changed to a more deductive approach, explicitly based on the Vriens et al. (2018) model to guide our research. By doing so, our focus shifted from ‘what does a.s.r. do to stimulate moral agency?’ to the question ’what can we learn about the relation between structure, contexts and moral agency at a.s.r.?’. Table 3 provides an overview of these two phases, our sources, and their role in our research.

Interviews and Analysis

The most relevant source of data is 22 in-depth semi-structured interviews, allowing for rich data gathering on individuals’ thoughts and behavior, which, as we indicated above, seems suitable in studies on complex issues (Boyce & Neale, 2006; Justesen & Mik-Meyer, 2012) such as ethical behavior. All interviews were recorded with the consent of respondents and transcribed; respondents received the transcripts for member check. These interviews, lasting between 45-60 minutes, were conducted in two phases.

In the first round of interviews (seven in total), information was gathered in a primarily inductive way, including several semi-structured questions inviting respondents to discuss and reflect on (1) morally responsible behavior of and within a.s.r. and (2) organizational factors influencing this behavior (see for both Table 2). Besides general questions about these two issues, several questions related to specific influencing factors (leadership, culture, structure and reward-systems cf. Stead et al., 1990, Treviño et al. 2006, 2014) were asked. The goal of these interviews was to learn more about (expectations about) moral agency of a.s.r. employees and about the organizational conditions (among which the structure) to promote it. As we indicated, this information was used to affirm that a.s.r. was indeed a proper case organization. To learn about moral agency and organizational conditions promoting it, we started with an interview with the CEO (who was responsible for the transition leading up to an organization with changed values, attitudes and behavior), followed by interviews with staff-managers representing a specific focus on both topics. Although this has been in part achieved (due to availability), it turned out that all (including the CEO) had information about expectations about moral behavior and facilitating conditions. Finally, we interviewed operational managers, in the hope that they could provide us with information about how moral agency came about in their line of business and what they thought about the implemented conditions for moral agency.

We employed a thematic analysis of the transcripts (cf. Braun & Clark, 2006; Nowell et al., 2017), using six initial codes: ‘ethical/responsible behavior,’ ‘conditions for ethical behavior,’ and four different types of conditions: leadership, culture, structure, and reward-systems. We selected the first two codes as they would represent the two main themes that relate to our goal for these interviews. We used the four types of conditions as codes, given their prevalence in several studies on organizational conditions for moral behavior (e.g., Stead et al., 1990; Treviño et al., 2006, 2014; Treviño & Nelson, 2017). Further thematic coding expanded the chosen codes, and yielded several sub-themes, with the exception of reward systems, which was regarded as a subtheme of the theme HR-policies (which also comprised recruitment, selection, and training). These interviews provided insights into the current structure of a.s.r., the role and value of a.s.r.’s claim ‘to help clients,’ and how the company seeks to ensure that employees live up to the company values. These interviews convinced us that a.s.r. could indeed be an appropriate case for further empirically exploring the thesis that certain structures are supportive of virtuous moral agency (Nicholson et al., 2020; Vriens, et al., 2018).

The second round of interviews (15 in total; see Table 2) was more deductive in nature as the pre-defined open questions were aimed at the relevant concepts, i.e., the exercise and development of a moral character, the three supportive contexts, and the four structural parameters outlined above. Besides open questions about moral behavior, a vignette was used to portray moral agency from a virtue ethics point of view, and respondents were asked how their own work-related behavior related to the vignette. Moreover, respondents were asked about key elements related to the three contexts (e.g., regarding the teleological context they were asked about the goal of a.s.r., and about how their own work related to that goal) and they were explicitly asked about structural parameters with the aid of drawings (e.g., regarding the parameter functional concentration they were presented with a drawing of an insurance company with functional departments in which many types of insurance-related products were processed by employees versus a drawing in which dedicated production flows handled a subset of products). Next, they were asked which drawing was a more accurate representation of the actual a.s.r. structure, and they were asked for an explanation. Besides these ‘drawing related’ questions, respondents were asked about indicators of the parameters (e.g., again for functional concentration, the question ‘how many different products or services do you come across in your daily work?’ was asked). In these interviews, respondents were also asked to elaborate on moral issues they encountered and to explain how they dealt with them. The second round of interviews thus not only provided specific information on the organizational structure and the three contexts, but also about work-related moral agency. Finally, by discussing specific moral issues, the interviews enabled us to ‘trace’ dealing with these issues in relation to the three contexts and structure (see also Table 2). This second set of interviews was more aimed at finding out how structures and moral agency were related, and we selected respondents that had different types of jobs—both managerial (five staff members and two managers of sales departments), and operational (eight members of product units)—as moral issues and structural characteristics of these jobs may differ in these different types of jobs. For these interviews, we used the model by Vriens et al. (2018) to translate (1) moral behavior, (2) the three conducive contexts, and (3) structure/design parameters into interview topics and semi-structured questions. To analyze these interviews, we coded the transcripts using a template analysis (cf. King, 2012) in which a-priori template themes were taken from the Vriens et al. model. As King (2012) explains, template analysis is suitable for a deductive, theory-driven analysis of qualitative data. After several rounds of coding, a final template was arrived at.

Finally, we used all 22 interviews to trace how dealing with moral issues was related to the contexts and structure. To do so, we used an additional theme (‘dealing with a moral issue’) to code all interviews. Moreover, we used the final template for coding the second round of interviews (see above) to relate contexts and structures to ‘dealing with moral issues.’ In this way, we were able to identify specific moral issues, how employees dealt with them, and dealing with them was related to the three contexts and structure at a.s.r..

Documents

Before, during, and after the two rounds of interviews, we consulted a range of company documents (see Table 3). These documents offered a better understanding of the organizational structure (organogram, company-web-site), the CSR-strategy (annual reports, company web-site), the financial as well as non-financial achievements (annual reports, annual magazine, company website).

The Denison Culture Survey

The company also provided us access to results of the Dension Culture Survey, also called ‘Denison-scan.’ This (validated) scan sets out to measure organizational culture referring to four traits (‘involvement,’ ‘consistency,’ ‘adaptability,’ and ‘mission’), which are divided into several trait-components and operationalized into a set of Likert-scale items (cf. Denison et al., 2014; Gillespie et al., 2008). Each item contained a statement to which a reaction on a seven-point likert-scale could be given, and approximately, 3460 employees of a.s.r. filled out this scan in 2021. The results of this scan are presented in terms of percentile scores on each statement regarding the organization, compared to more than 1000 companies that have also filled out the scan (www.denisonconsultancy.com).

Although not all items of this scan are relevant for the purpose of this paper, some were especially valuable for understanding a.s.r.-related structural aspects and characteristics related to the three conducive contexts and will be referred to in the result section (see Table 4 for the statements used).

Results

In this section, we present our findings on whether and how moral agency at a.s.r. is supported (or not) by a.s.r.’s structural arrangement and the conditioning contexts (co-depending on this arrangement). We do so in two steps: first, we describe and assess a.s.r.’s structural arrangements and conditioning contexts (next two sections). Second, we present our findings on how moral agency at a.s.r. is affected by its structure and contexts (section "Relating Moral Agency in a.s.r. to the Organization’s Structure and Conditioning Contexts").

The Structure of a.s.r.

In general, we assess the structure of a.s.r. as flat with relatively independent business units (they use the term ‘business lines’) that are mostly dedicated to a subset of products. In these business lines, teams operate with a relatively high degree of autonomy (which is bounded, however, by the financial impact of decisions and also by the core values and norms that are set for the entire organization). The interaction with clients by means of which both providing financial advice and the actual purchase of most insurance products take place is mostly outsourced to independent intermediaries, so informing intermediaries about products is crucial. Moreover, a.s.r. still independently assesses whether a product is suitable for the client. Even though many sales activities are outsourced to intermediaries, interaction with clients relating to products is still relevant, e.g., answering questions and providing information about products clients want to purchase; providing information about product-updates, communication related to invoicing, and about processing claims. Most departments have a front-office (for intake and simple issues) and a back-office in which ‘specialists’ further handle client demands which cannot be dealt with by the front-office. These back-office specialists mostly deal with the client from beginning (after referral by the front-office) to end and are part of a team which discusses cases and which can make joint decisions about how to deal with difficult issues. Furthermore, many business lines have their own dedicated staff-units (e.g., HR, finance). Finally, staff-units at the company level exist (e.g., corporate communication, corporate finance, corporate compliance, HR, etc.) as well as a general corporate management, supporting the business lines and formulating a company strategy. Below, we will briefly detail the structure of a.s.r. in terms of the four design parameters.

Functional Concentration

As noted above, a.s.r. has organized many of its activities in relatively independent units (‘business lines’) which are mainly product oriented. So, separate business lines concerning different types of products (e.g., life insurances, health insurances, income insurance, etc.) house employees that mainly focus on the products in that business line. Sometimes other criteria were applied for further identifying ‘separate’ product/market units within the business lines, like type of clients (companies or private) or regional criteria (e.g., postal code). In all these instances, employees performed activities dedicated to a subset of the output (i.e., type of product/type of client/region). The business lines have dedicated operational activities (sales, handling claims, dealing with client questions, etc.) and have some staff-functions dedicated to them (e.g., finance). Hence, the structure of a.s.r. can be characterized as having a relatively low degree of functional concentration (operational units in which employees only performed activities with respect to a subset of the output). This is in line with how respondents described their unit during the interviews. R6 noted, for example, that he/she experienced his/her unit as quite independent: our business line almost operates as a separate business. However, not all a.s.r. activities take place in dedicated business lines. Many staff-functions (e.g., compliance, corporate communication, HR, etc.) are organized independently of the business lines and oversee the whole organization.

Job-Specialization

We assess the degree of specialization to be relatively low—although two factors contributed to some operational specialization. First, a.s.r. chose to sell products by intermediary agents. Sales activities, therefore, are directed at these agents (not to the end-customers) and entail informing agents about (new) products and about the values these products (and a.s.r.) stand for. Moreover, a.s.r. checks whether an intermediary has asked the right questions to a client and checks whether a product is offered that a client really needs. This means that sales representatives of a.s.r. do not have direct contact with end-customers.Footnote 1

Second, many business lines have implemented a front/back-office structure, introducing another form of specialization. However, to minimize the negative effect of this type of specialization, e.g., to ensure that clients don’t have to wait too long and that they have, as much as possible, one contact person for relevant or difficult issues, the front-office often processes simple, routine issues and forwards more complex issues directly to ‘back-office specialists.’ In one business line they even installed so-called ‘floor-walkers,’ specialists that were present at the front-office who immediately responded to a difficult issue, once it was noted by a front-office employee. Front-office employees could deal with simple client issues themselves, from beginning to end; and once clients with non-routine/difficult issues were related to back-office specialists, they, too, dealt with the client for the whole issue.

The specialization of staff-functions was low—as staff-functions covered (a large part of) the complete process. Many of the employees having (corporate) staff-functions thought their work was not split up, but instead covered processes from beginning to end.

Separation

Separation is about the degree to which decision authority or regulation of some job or process is separated from (is not part of) performing that job or process. A high level of separation leads to a hierarchy of regulators. Our data indicate that the level of separation of a.s.r. is relatively low. That is, as many respondents remarked, employees felt that they had ample decision authority to make relevant decisions regarding their own work. Respondents operating in the primary process, for instance, said that operational and regulatory activities were highly integrated (R19) and one respondent remarked: I can work very independently. And if I come across something, I try to find a solution, I don’t need my supervisor for that (R20).

This is also supported by scores from the Denison scan on two combined statements: (1) “decisions are made at the level where the relevant information is available.” Here, a.s.r. achieves the percentile score 90 (out of 1000 + companies); and (2) “to get the work done we rely more on team-work than on the hierarchy” (score 95)—see also Table 4. Which structural arrangements helped employees to make relevant decisions themselves or discuss them in their team/or their manager, will be further illustrated below (4.2).

Formalization

Although many rules and procedures regarding insurances exist (like the law or the rules set in insurance contracts), no respondent felt restricted by the rules and procedures set by a.s.r. for doing their work. They indicated that the current procedural frameworks provided clear and helpful guidelines for doing their work and did not restrict decision-making. And, as it comes to rules for moral behavior, it was remarked that the existing code of conduct was helpful as it made employees aware of what is and what isn’t—in general—expected in certain situations. However, it was also remarked that it was, in the end, not the set of stated rules that is referred to when making a morally laden decision: In all honesty, employees will not process something based on rules in a moral situation […] rather they discuss moral cases to find out what is the right thing to do (R16). The opportunity to use the code as a background for moral decision-making and make final decisions based on moral discussions fits a more ‘integrity’-based approach to moral agency (cf. Sharp-Pain, 1994). In all, we assess the degree of formalization to be relatively low: many rules and regulations exist, but they do not dictate the way work should be done.

The Three Conditioning Contexts at a.s.r.

Teleological Context

The teleological context of an employee’s work entails that the employee knows what the goals and output of the organization are, that the employee can see the actual output and the degree to which goals are realized, and that employees know how their own work contributes to realizing the organizational goals and output.

As we noted earlier, a.s.r. has radically changed its goals which now highlight being a ‘responsible insurance company.’ As the CEO put it: It is our goal to help people share risks they can’t bear themselves and to build up assets […] ‘Helping by doing’ is the essence. We should always try to find out how we can best help a client, a colleague or stakeholder. He further explained that this ‘helping by doing’ is based on several core values: always be approachable and listen carefully, always be focused on providing solutions based on experience, knowledge, empathy, and a keen sense of the needs of a client.

From the interviews with those in the operating core of the company, as well as from the results of the Denison scan, it appears that employees are quite aware of the new goals and core values that should guide their work. The following items from the Denison scan also indicate this: “There is a clear and consistent set of core values that determine how we work” (score: 83), “There is a broad consensus about the goals we need to attain” (91), “Goals have been clearly communicated by management” (86), and “There is a clear mission directing our work” (81)—see also Table 4.

Quotes from two salespersons further illustrate the awareness of the goals and values:

“What appeals to me is that since a couple of years a.s.r. tries to be an exemplary organization when it comes to CSR […] it tries to be a good company for employees, customers and stockholders” (R6).

“Everything we do, should be done in the interest of the client. […] So, we should make sure that the products we sell are products our clients are waiting for” (R2).

The Denison scan and interviews also made apparent that employees know what their contribution to the goals and output is. This is explicitly covered in the item “Every employee understands which contribution to make to the business line goals or overall goals of a.s.r. “ (score: 96). Moreover, the statement “Ignoring our core values is unacceptable” (score 96) clearly indicates that core values are very important guidelines. Furthermore, the statement “Setting and monitoring goals is a continuous process involving everybody to a certain degree” (score 92) seems to indicate that monitoring goals is part of all employees’ jobs. One of the respondents (R10) provided us with an insight into the teleological context concerning the issue of employees knowing how their jobs contributed to the goals and output of a.s.r. As he/she explained;

“If you had asked me what the core business of processing declarations was, about 1,5 years ago, my team and I would have answered: making sure that declarations and questions about declarations are processed without errors as quickly as possible – to the satisfaction of clients. […] However, we came to realize that helping clients as part of our work doesn’t just mean processing declarations, but that clients want above all that we take the time to provide them with the best possible advice if they have any questions or concerns. So, we invested in the digitalization of processing declarations and are now using the time we won to deal with these questions and concerns. And to help them in the best possible way, we are training our employees to learn more about the specific healthcare context and they pay visits to healthcare providers.”

In this case, the goals (helping clients) and output (in this case: processing declarations and providing clients with advice) have become thoroughly embedded in the work of this team.

During the interviews, some respondents also voiced concerns about not being able to be in touch with the output. They pointed out that this depended on the type of job—in operational jobs it was easier to be connected to the output (as the example above illustrates) than in general staff-functions. That is, although some holding such positions said that their function was to provide conditions for the operational core to ‘help clients in the best possible way’ and hence were aware of their indirect contribution, others had more difficulty seeing this contribution. As one respondent (R1) remarked:

“Well, seeing the connection between my job and the organization’s contribution to society is a difficult one for me – I mean, what can someone really contribute if one is not in a business line?”

In all, the Denison scan results and interviews seem to point out that most employees are in touch with the (new) goals and values that are supposed to guide their work, and most of them also see how their own work is connected to delivering the a.s.r. contribution—although the degree to which one feels to be in touch with goals and output may depend on the type of job.

Deliberative Context

As discussed, the deliberative context of one’s work should enable organizational members to reflect on, devise, implement, and learn about ‘appropriate’ moral actions in the context of their work. Employees should be enabled to acknowledge and understand work-related moral issues, and based on context-specific deliberation (including an assessment of the moral consequences of possible actions) devise and implement a morally appropriate action. The deliberative context should also enable them to reflect on the actual consequences of their actions so as to enable further developing their moral character.

The CEO explained that the changed goals and values entail that employees are supposed to help clients to the best of their ability. This means that they are supposed to try to understand the clients’ ‘real needs’ and respond to these needs in an honest and appropriate way. Helping clients this way requires empathy, integrity, and the conditions to find a suitable solution. In this way, potentially every client-related interaction can be understood as having a moral component.

To realize this way of dealing with clients’ needs requires a deliberative context as described, enabling employees to understand the ‘real’ client issues and to reflect on and devise possible actions doing justice to these issues. The scores on the Denison items also provided some evidence of the availability of the deliberative context. For instance, as far as the a.s.r. outcome relates to ‘helping clients in the best possible way’ (as many respondents in the interviews claimed) the high score (89) on the statement “everybody believes that (s)he can have a positive influence on outcomes” provides some indication that employees believe that they are enabled to help clients. In a similar vein, the statement “decision authority is low in the organization, so that employees can show initiative” (71), as well as the statement “Decisions are made at the level where the relevant information is” (90) seem to indicate the availability of conditions for employees to devise relevant actions to deal with client issues themselves.

The interviews provided more information on the deliberative context as respondents stated that they were supposed to find out the ‘real’ needs of the clients and to try to respond to these needs in the best possible way—which entailed providing a response ‘within’ and ‘beyond’ product. Moreover, they also stated that they found that the organization provided the conditions for coming up with such responses.

A respondent working in the healthcare insurance business line (R17) explained what this entails. He/she stressed that clients contacting his/her department often have delicate health issues. Dealing with clients hence requires really taking the time for a client. He/she also stated that helping vulnerable clients meant that we need to be a guide for clients. He/she explained that in talking and listening to clients, he/she seeks to understand the context of his/her clients’ needs. And if that becomes clear, he/she first tries to help the client in the context of the insurance contract the client has (e.g., see whether the insurance covers the issues raised in the conversation with the client) and if that is not the case, he/she tries to find other solutions for a client: if we can’t help a client based on the rules or conditions of the contract, we help the client by actively searching for other solutions. In such cases, the team the respondent was part of, reflected on such solutions and decided on a way of helping the client (which could range from paying a client even though the insurance didn’t cover it to actively looking—with the client—for other institutions who could be of help). Based on how the solution worked out, the team also jointly reflected on such cases with the aim to learn. This example illustrates how the deliberative context—i.e., organizational conditions supporting the opportunity to reflect on, devise, implement and learn about ‘appropriate’ moral actions—is implemented. It also illustrates how such deliberation is socially embedded—see the social context.

However, even though most respondents agreed to the availability of the deliberative context, some respondents mentioned that workload and individual differences might have a negative effect on the deliberative context. High workload was said to impair taking the time to understand and deal with clients’ needs and it was said to come at the expense of deliberation, reflection, and learning and could hence frustrate the realization of the deliberative context. One respondent explained that sometimes my colleagues have so many files to process, that they can’t ask [clients] how to help them, let alone to offer help (R20). Another respondent added that reflection is also impaired by work pressure: … to be honest work is quite hectic […] you continuously need to move on, which is ok, but reflection is also needed. And I think I’m not doing that sufficiently (R19).

Respondents also pointed at individual differences and mentioned that not everybody in the organization was equally motivated to deliberate on helping the clients in the best possible way, as they said that this required a certain attitude that may not fit one’s personality. For some respondent, the opportunity to ‘really listen to and deal with clients’ concerns’ was one of the reasons why working at a.s.r. was worthwhile (R20), while others remarked that this way of responding to clients’ needs is something that should fit ‘one’s personality’ which may not always be the case (R1, R2, R4 and R8). Indeed, it requires, as a respondent (R4) remarked quite some life- and work experience which needs to be built up, and which not everybody has. It has led to a form of ‘self-selection’ (e.g., employees leaving the company) and to a kind of ‘agency dodging’—i.e., trying to avoid difficult cases. As one respondent (R4) said: Most workers I know try to help the client themselves to the best of their abilities – but there are also those who think ‘who can I forward this case to?’

Social Context

As discussed, the social context for moral agency in organizations refers to actively being involved in a social network which serves as a background for moral awareness, moral deliberation, and action. The organizational social network serves as a background for disseminating and stabilizing values and ideas about ‘proper conduct’ and it enables organizational members to jointly reflect on the relevant moral values that are at stake in their work in general, and in particular work-related contexts. It also enables them to jointly discuss and devise actions when dealing with moral issues, and to jointly learn about the outcomes of these actions. In the a.s.r. organization, the social context of operational insurance work refers to two levels: the organization as a whole (serving as a background for the socialization of certain values and attitudes, e.g., the relevance of the integrity of employees) and the teams employees are part of. Besides facilitating the further socialization of values and attitudes, these teams serve as a background for joint reflection on work-related moral issues, for joint deliberation on values and actions in specific contexts, and for joint learning about the appropriateness of the actions performed in these contexts.