Abstract

This study investigates the differential roles of corporate social responsibility (CSR) in the context of negative events. By categorizing CSR and negative events by their respective stakeholder groups, primary and secondary stakeholders, we theorize and test differential impacts of CSR and their interaction effects with different types of negative events. We propose that, while CSR toward secondary stakeholders offers the monotonous risk-tempering effect, CSR toward primary stakeholders has heterogeneous effects when facing negative events. Specifically, the effect of CSR toward primary stakeholders varies with the type of negative events. When negative events are associated with secondary stakeholders in the domain of morality, CSR toward primary stakeholders presents a risk-amplifying effect. When the negative events are associated with primary stakeholders in the domain of capability, however, CSR toward primary stakeholders does not present a significant risk-amplifying effect. In contrast, CSR toward secondary stakeholders presents the risk-tempering effect regardless of the type of negative events. We find general support for these arguments when we analyze the market responses to the news events of RepRisk, which provides data of various corporate negative events covered by the media.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Many firms find themselves, often unexpectedly, involved in negative events related to environment, social, and government (ESG) issues during the course of their business operations (Schrempf-Stirling et al., 2016). The 2010 Deepwater Horizon oil spill by British Petroleum (BP) and labor issues of Foxconn in China and its spillover effects on Apple in the form of a boycott in 2012 are examples of these negative events. Such negative events can have detrimental effects on firms’ stock performance and even long-term survival. For example, following the oil spill, BP stock lost half of its value within a single month, and BP bonds were downgraded almost to junk bond status.

In this globalized and well-connected society, it seems that it is not a matter of if, but of when, a firm will face unexpected negative events. Accordingly, the role of CSR has received substantial attention from both industry and academic communities due to its potential insurance effects against negative events (Godfrey et al., 2009). Several studies argue for an insurance effect of CSR, suggesting that CSR assists a firm to build goodwill, which allows stakeholders to give the firm the benefit of withholding doubt when negative events occur, thereby attenuating the punishment that the firm might receive from the negative event (Choi & Wang, 2009; Godfrey, 2005; Schnietz & Epstein, 2005).

On the other hand, extant literature also provides counter arguments, raising doubts about the insurance effect of CSR. These studies suggest that, under certain conditions, CSR might become a burden, rather than a buffer against negative events (Rhee & Haunschild, 2006; Wade et al., 2006). For example, Wernicke (2016) found that firms with a high performance in CSR would face more negative media coverage with the occurrence of a negative event. Furthermore, some firms might decide not to publicize the award of a prominent certification of certain CSR domains in order to avoid a potential reputational threat (Carlos & Lewis, 2018). These studies indicate that CSR might not be able to provide insurance-like protection, in case of real or potential negative events.

Mixed arguments and inconsistent evidence on the roles played by CSR in the context of negative events call for new research to reconcile the seemingly contradicting arguments (Wang et al., 2020). As a step toward reconciliation, this paper recognizes that the role of CSR may vary across different types of CSR; in addition, the role played by the same type of CSR may also vary when facing different types of negative events. Prior studies, however, mostly focus on the role played by the aggregate level of CSR or a type of CSR in the context of a specific type of negative event (Carlos & Lewis, 2018; Janney & Gove, 2011; Wernicke, 2016). There has been no comprehensive study, to the best of our knowledge, that investigates the differential roles played by various types of CSR and how the roles are further influenced by various types of negative events.

We categorize CSR and negative events based on their respective target stakeholder groups (primary vs. secondary stakeholders; Godfrey et al., 2009; Mattingly & Berman, 2006). The instrumental nature of the CSR toward primary stakeholders makes analytical information-processing mode, as opposed to affective information-processing mode, dominate stakeholders’ interpretation of a negative event (Epstein, 1994; Pfarrer et al., 2010; Shiffrin & Schneider, 1977). Under such an analytical information-processing mode, stakeholders’ response would likely be more negative and vary with the nature of the negative event.

In contrast, CSR toward secondary stakeholders has an affective nature that stimulates an affective information-processing mode (Slovic et al., 2004; Wei et al., 2017). Unlike the analytical information-processing mode, the affective information-processing mode reduces the need for evaluators to engage in deliberate analysis, but encourages the use of mental shortcuts. Consequently, when negative events occur, a strong CSR performance towards secondary stakeholders is more likely to prompt stakeholders to rely on pre-existing perceptions of the firm, with less attention given to the negative events. This process results in confirmatory bias, inducing stakeholders to discount or dismiss the new information associated with the negative events and withhold their doubt about the firm, regardless of the nature of negative events (Dowling, 2004; Rabin & Schrag, 1999).

To test these arguments, we used a dataset provided by RepRisk AG, which is available at Wharton Research Data Services (WRDS). RepRisk is a business intelligence provider that specializes in reputational risk based on media coverage of environment, social, and government (ESG)-related socially irresponsible events. We combined RepRisk datasets with the KLD dataset for corporate social performance, as well as Compustat for financial data, for the sample period over 2007–2018. Our empirical results provide supporting evidence for our theoretical arguments. We find that CSR toward primary stakeholders has a risk-amplifying effect when negative events are associated with secondary stakeholders. However, the negative effect is negligible when the events are associated with primary stakeholders. In contrast, the risk-insurance effects of CSR toward secondary stakeholders have almost the same magnitude, irrespective of whether the negative event is associated with primary stakeholders or secondary stakeholders.

Our study provides a resolution for the mixed arguments with regard to the role of CSR in the context of negative events. Previous literature often treats CSR as single dimensional construct, and thus it overlooks the differential role served by different types of CSR in the context of negative events (Hetze, 2016; Miller et al., 2020; Minor & Morgan, 2011). Accordingly, these studies often delineate only one perspective of CSR, either a positive insurance effect or a negative reputational threat (Godfrey et al., 2009; Liu et al., 2020; Shiu & Yang, 2017). Departing from such a unidirectional approach, we showed that a high performance in CSR not only provides an insurance effect but, under certain conditions, also induces reputational threat (i.e., an amplifying effect). By examining differential roles served by different types of CSR simultaneously, our study contributes to the identification of the underlying pathways by which CSR protects firm value or amplifies risk.

The rest of the paper is organized in the following manner. First, we discuss how different types of information-processing modes shape the interpretation of social evaluators regarding negative events differently. Then, we develop a set of hypotheses on how different types of CSR trigger distinct information-processing modes for stakeholders facing negative events and further influence their judgment. Next, we describe the data, how they were gathered, and the statistical models used to test the hypotheses. Finally, we provide results on the role of CSR and corresponding implications.

Theory and Hypothesis Development

In this paper, a negative event is defined as “an unexpected, publicly known, and harmful event that has high levels of initial uncertainty, interferes with the normal operations of an organization, and generates widespread, intuitive, and negative perceptions among evaluators” (Bundy & Pfarrer, 2015: 345). When a negative event occurs, unless individual evaluators find satisfying explanations within their current frame of perceptions, they need to modify or reconstruct their perceptions of the environment and the focal firm (Martinko, 1995). As a consequence, a key issue regarding the role played by CSR in the context of negative events is how the CSR performance built by past CSR activities influences firm stakeholders’ interpretation of negative events.

Mode of Information-Processing

In face of the outbreak of negative events, social evaluators or stakeholders’ interpretation of negative events is largely shaped by the mode of information-processing regarding the events (Heider, 1958; Lord & Smith, 1983). In the psychology literature, the original terms of the two modes are the rational and the experiential system (Epstein et al., 1996). We use the terms analytical and affective, respectively, inspired by original explanations of the two systems. “The rational system operates primarily at the conscious level and is intentional, analytic, primarily verbal, and relatively affect-free. The experiential system is assumed to be automatic, preconscious, holistic, associationistic, primarily nonverbal, and intimately associated with affect.” (Epstein et al., 1996: 391). In an affective mode with a low level of effort in information-processing, social evaluators tend to reach a quick resolution by adhering to already established patterns. In an analytical information-processing mode, on the other hand, social evaluators are more likely to engage in effortful and deliberate sense-making processes (Epstein, 1994; Shiffrin & Schneider, 1977).

Therefore, with the affective information-processing mode, social evaluators treat negative events as inconsistent pieces of information. To reduce cognitive dissonance rapidly, they simply weigh unequal values on different pieces of information and pay more attention to information that is consistent with previously held beliefs, i.e., confirmatory bias (Festinger, 1957; Harmon-Jones & Mills, 1999; Slovic et al., 2004). Stakeholders are more likely to rely on their existing stereotypes towards the firms for a quick resolution (Bodenhausen & Lichtenstein, 1987). Consequently, they tend to attribute negative events to situational factors, as opposed to intentional factors, which would otherwise dispute their prior beliefs (Martinko, 1995). In sum, evaluators under affective information-processing mode find their current frame of perceptions more satisfactory.

With the analytical mode on, in contrast, stakeholders are more likely to treat negative events as a violation of expectation and to analyze the crisis deliberately, leading to an effortful sense-making process (Coombs, 2007; Roese & Sherman, 2007). It is worth noting that even in such a relatively rational mode of information-processing, stakeholders are not free from cognitive biases due to bounded rationality, which is an innate characteristic of human beings (Cyert & March, 1963; Simon, 1957).

When a negative event occurs in the domain of morality, stakeholders’ evaluation is more likely to be negatively biased. Extensive research suggested that in the morality domain, the integration of both positive and negative information often results in negativity bias (Reeder & Brewer, 1979; Skowronski & Carlston, 1987; Wojciszke et al., 1993). Specifically, the negative violation of expectation is thought to be more demonstrative about what a firm is really like (Burgoon & LePoire, 1993; Sohn & Lariscy, 2012). The underlying logic is that even firms that are morally flawed can act hypocritically and pretend to be moral. Consequently, acting morally does not lead to evaluators’ solid conclusion that the firm is indeed moral. However, firms engaged in ethically dubious activities are those which do not even bother to pretend to be moral. These amoral behaviors are enough to reveal the firms’ true selves (Mishina et al., 2012). As a result, a negativity bias, i.e., a significant asymmetry between responses to positive events and those to negative events, is often observed (Baumeister et al., 2001; Fiske & Taylor, 2013; Kanouse, 1984). Therefore, when a negative event occurs in the domain of morality, stakeholders with an analytical mode consider the negative event as an intentional fault and amplify their reactions to the negative event.

In the case of negative events in the domain of competence, however, stakeholders’ evaluation is more likely to be positively biased. Such tendency is well documented in previous literature suggesting that, in the domain of competence, information with mixed directionality makes evaluators place greater weight on positive information (Reeder & Brewer, 1979; Skowronski & Carlston, 1987; Wojciszke et al., 1993). Wojciszke et al., (1993: 327) reported that “competent performances occur only among highly competent persons, whereas even highly competent persons may sometimes fail because of obstacles, fatigue, or lack of motivation. In the competence domain, positive behaviors are therefore more diagnostic than negative ones.” In our context, firms that are not competent cannot simply pretend to be so. In other words, competence is value-neutral and not swayed by the intention of firms.

It is critical to note that analytical and affective information-processing modes are parallel and interactive, but one can dominate the other (Cerni et al., 2010: 52). Then, the remaining question is what makes one mode dominant over the other. Prior literature has shown that the nature of the stimulus is the key. For example, Thompson and Hamilton’s experiment (2006) successfully manipulated evaluators’ dominant information- processing mode by providing them with a corresponding stimulus. As an extension of Thompson and Hamilton (2006), our central argument is that the nature of CSR as the stimulus either toward primary or secondary stakeholders determines the dominant information-processing mode, either analytical or affective.

Corporate Social Responsibility

The definition of CSR varies across studies. Carroll (1979) provides an encompassing definition, stating that CSR involves four components: economic responsibility to investors and consumers; legal responsibility to the government or the law; ethical responsibility to society; and discretionary responsibility to the community. McWilliams and Siegel (2001), however, present a focused definition of CSR as “corporate actions, not required by law, that attempt to further some social good and extend beyond the explicit transactional interests of the firm.” Although CSR activities often go beyond the transactional interests of firms, the line of demarcation is not always clear. For example, providing high quality or innovative products might not constitute a form of CSR beyond transactional interests of the firm. However, when there is a massive recall regarding product quality, most stakeholders perceive this type of event as a CSR-related event.Footnote 1 Despite, and due to, the complex nature of CSR toward primary stakeholders, this dimension has been commonly included in CSR measures, especially based on CSR’s broader definition (Rhee & Haunschild, 2006). Therefore, to avoid potential confusion and to align with the research questions of this paper that investigate boundary conditions for CSR-driven effects in the context of negative events, we follow Carroll’s (1979) broader definition in this study.

To examine the varying roles of different types of CSR performance at the outbreak of negative events, we categorized CSR activities into two types based on the stakeholder groups that they are serving, in accordance with prior literature (Godfrey et al., 2009). The first type is CSR geared toward primary stakeholders who can directly influence firm operations (Su & Tsang, 2015). The second type is CSR geared toward secondary stakeholders, who are organizations or groups of people that are indirectly involved in a firm’s operations and actions (Baron, 1995; Clarkson, 1995; Mitchell et al., 1997; Suchman, 1995).

CSR Toward Primary Stakeholders and Market Response to Negative Events

A high performance in the domain of CSR toward primary stakeholders is built upon the success of previous interactions between focal firms and their primary stakeholders, for example, product innovativeness. With good CSR toward primary stakeholders, firms are likely to have greater accessibility to resources that are critical to value generation in the long run (Deephouse, 2000; Pfarrer et al., 2010). This type of CSR tends to be mutually beneficial to the focal firms and the primary stakeholders.

Therefore, the instrumental nature of this type of CSR renders the analytical information-processing mode a dominant one at the outbreak of negative events. When a negative event occurs to a firm, under the analytical mode of information-processing, stakeholders go through an effortful sense-making process aimed at explaining the discrepancy between their expectations on role-related performance built by reputational signal and reality (Burgoon & LePoire, 1993). Consequently, stakeholders would react context-specifically instead of taking a mental shortcut and giving universal reactions. In other words, stakeholders’ evaluation of negative events is not only determined by the domain of CSR engagement (i.e., whether toward primary or secondary stakeholders), but is also influenced by that of the negative event itself (i.e., whether the event is associated with primary or secondary stakeholders) (Carlos & Lewis, 2018; Godfrey et al., 2009; Wernicke, 2016).

If the focal negative event happens in the domain of morality (i.e., a negative event associated with secondary stakeholders), it calls a firm’s trustworthiness into question. As a result, CSR toward primary stakeholders is more likely to generate the risk-amplifying effect. Even though a firm has verified capability and efficiency in delivering specific outcomes in the past, the negative events in the domain of morality induce stakeholders to question whether the company will continue to be responsible for stakeholders (Mishina et al., 2012: 461). As mentioned previously, firms engaged in ethically dubious activities are enough for evaluators to conclude that these firms are truly amoral, and they do not even bother to pretend to be good (Mishina et al., 2012). After their delineated evaluation, stakeholders likely perceive high risk and vulnerability, which may come from the premium price paid by customers due to prior beliefs toward the firms’ reliability. Given the presence of negativity bias, primary stakeholders would take quite drastic steps to protect their invested financial, social, and attentional capital from additional opportunistic behavior by the firm as signaled by the outbreak of negative events.

However, the situation would be different if a negative event is associated with primary stakeholders (i.e., the negative event is in the domain of competence). Such evidence driven by an occasion would be given little weight in the stakeholders’ interpretation of the event if a firm has historically proven accomplishments in a consistent manner. Once a firm has proven its ability to perform at a high level, evaluators will believe that a negative event may not be sufficient to fully dispute a firm’s underlying competence (e.g., Anderson & Butzin, 1974; Surber, 1984), and that the firm would be able to deliver superior outcomes again in the future.

The stock market is likely to respond to the negative events in line with stakeholders’ interpretations. First, investors are a part of firm stakeholders (Freeman, 2010; Parmar et al., 2010) who claim the economic profits generated by firms, but may also have preference in investing in firms in which they are able to trust (Barney, 2018). To the extent that the outbreak of negative events might directly affect shareholders’ perceptions of the firm, it induces them to adjust their exposure to the investment in the firm accordingly. In addition, how other stakeholders (e.g., customers, employees, and suppliers) respond to the firm in view of a negative event affects the firm’s financial outcomes. In particular, when these other stakeholders’ perceptions of a firm become negative, they may take subsequent corrective actions, such as reducing the level of cooperation with and support for the firm, which hinders the firm’s financial performance. Therefore, investors further incorporate the influences of such subsequent corrective actions taken by primary stakeholders concordantly.

Therefore, we generate the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1a

The adverse effect of CSR toward primary stakeholders on the stock-market reaction to negative events varies with the type of negative events.

Hypothesis 1b

The adverse effect of CSR toward primary stakeholders on the stock-market reaction to negative events is more salient when the negative events are associated with secondary stakeholders than with primary stakeholders.

CSR Toward Secondary Stakeholders and Market Response to Negative Events

A high performance in the domain of CSR toward secondary stakeholders is built upon firms’ social activities beyond role-based prescriptions for economic value maximization (Godfrey et al., 2009). For example, such activities may include a firm’s substantial effort to make charitable contributions or its strong volunteer program for local communities. Stakeholders do not have prior expectancy toward such extra-role behaviors. Through CSR toward secondary stakeholders, i.e., something that is socially desirable but is not part of their formal requirements or responsibility, firms are able to induce positive feelings and attitudes of the general public even without their direct transactions with the focal firms (Orlitzky & Swanson, 2012), further enhancing corporate image and social recognition. Such positive intangible assets generated for CSR toward secondary stakeholders is what Godfrey (2005) termed as moral capital.

The affective nature of moral capital makes the affective information-processing mode a dominant one. Affection based on emotional bonding leads evaluators to make moral judgements based on prior beliefs instead of sense-making processes. Stakeholders’ affinity toward the firms induces them to discount or dismiss negative information related to the crisis (Dowling, 2004; Rabin & Schrag, 1999), i.e., confirmatory bias, thereby resulting in the biased attribution of a negative event to situational factors rather than to the firms (Zavyalova et al., 2012). Zajonc (1980) stated that, “Affect often persists after a complete invalidation of its original cognitive basis” (1980: 157). For example, stakeholders toward a firm with strong moral capital would more likely question the credibility of media delivering bad news rather than adjust their impressions of the firm. As a consequence, the transgression of the firm is mitigated in advance or discounted completely (Zajonc, 1980). Positive affect induces individuals or even experts to perceive less risk (Hsee & Kunreuther, 2000), and thus take higher risks (Seo et al., 2010). In our research context, positive affect built on moral capital causes firm stakeholders to perceive a lower level of vulnerability even at the outbreak of negative events, and to keep absorbing risk by withholding doubt. Therefore, the following hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 2

The higher is a firm’s CSR performance toward secondary stakeholders, the less negative is the stock-market reaction to negative events.

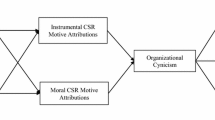

Earlier, we have argued that the risk-amplifying effect of CSR toward primary stakeholders varies with the type of stakeholders to which the negative event is associated. Basically, analytical information-processing induces evaluators to go through a deliberate sense-making process, leading to a context-specific response. In the case of CSR toward secondary stakeholders, however, given the nature of affective information-processing, social evaluators would not pay much attention to the specific context of negative events. Stakeholders would take a mental short-cut, instead of engaging in deliberate sense-making, as a natural response. Moreover, different from analytical reactions based on rational calculations, which make continuous adaptations in response to changes in decisions (e.g., optimization or risk/return matrix) (Fama, 1980; Friedman, 1953), an affective reaction changes its directionality only when the impact of new information is sufficiently significant to go beyond a threshold. Within a boundary, an affective reaction is expected to be stable in terms of its directionality and magnitude (Kahneman & Tversky, 1979). Therefore, we expect to identify an insurance effect even when the negative events are directly associated with secondary stakeholders. Therefore, the following hypothesis is proposed (Fig. 1):

Differential roles served by heterogeneous types of CSR in the context of negative events. a Primary stakeholders are those who can directly influence firm operations (Su & Tsang, 2015). Examples include employees, suppliers, and customers. b Secondary stakeholders are organizations or groups of people that are indirectly involved in a firm’s operations and actions (Baron, 1995; Clarkson, 1995; Mitchel et al., 1997; Suchman, 1995). Examples include the general public and communities. c In terms of empirical measurements, the scope of CSR toward primary stakeholders is restricted to product dimension in the KLD database. As for CSR toward secondary stakeholders, the study’s attention is focused on community and diversity dimensions in KLD database. Moreover, incidents that have a negative impact on community or government fall under the category of negative events within the moral domain. Conversely, negative events within the competence domain refer to those circumstances associated with products

Hypothesis 3

The risk-tempering effect of CSR toward secondary stakeholders is still present even for negative events associated with secondary stakeholders.

Data and Methodology

To test our hypotheses, we combined a dataset containing corporate negative events provided by RepRisk AG with a dataset by KLD (Kinder, Lydenburg, and Domini) on CSR scores. RepRisk AG is a business intelligence provider specializing in environmental, social, and governance (ESG) risk analytics and metrics. RepRisk compiles a database of negative news items that criticize companies. The data are gathered through search algorithms that filter out news articles from more than 100,000 publicly available worldwide sources, including international and local newspapers, online newswires, government agencies, nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), blogs, and social media. In addition to collecting news items, RepRisk provides a systematic assessment of the reach of the source (high/medium/low), the severity (high/medium/low), and the novelty (high/low) of each news item. The RepRisk database covers more than 180,000 worldwide public and private firms. Consequently, we limit our analysis to news items issued for U.S. public firms that are covered by the KLD database and Compustat. The RepRisk dataset offers three major advantages in elucidating the role of CSR during negative events. First, the news release dates contained in RepRisk allow us to examine the change in shareholder value, as represented by stock price, around the news release. Second, in investigating the role of CSR, identification of negative events is conducted in an unbiased manner, independent of a researcher’s intention (Kölbel et al., 2017; Lange & Washburn, 2012) because data collection is performed by an independent institution (i.e., RepRisk). Third, unlike previous studies on the insurance effects of CSR using a specific negative event type, such as litigation or WTO failure (Schnietz & Epstein, 2005), or a specific media, such as the Wall Street Journal (Shiu & Yang, 2017), the RepRisk dataset incorporates various types of negative events covered by diverse media. Utilizing the richness of the data, we are able to test the interaction effects between the domains of CSR performance and the domains of negative events. Finally, using RepRisk’s assessment of the characteristics of negative events, we are able to control for the severity and novelty of negative events, as well as the impact of the journal covering the events. Utilizing these advantages of the RepRisk dataset, we intend to improve the generalizability and objectivity of our findings in the CSR literature.

We use the KLD 400 Social Index Dataset (KLD) to obtain information on the CSR performance of a firm. This dataset assesses corporate social performance under several dimensions relating to community, human rights, diversity, employee relations, and products. Prior studies on CSR adopt this database to measure CSR engagement (Godfrey et al., 2009; Schnietz & Epstein, 2005). KLD is an independent rating agency that provides social performance assessment for extensive lists of U.S. firms. In addition to a direct survey of firms, it incorporates inputs from other firms’ stakeholder groups regarding their perceptions of a firm’s performance for social activities (Godfrey et al., 2009). In addition, the KLD dataset, as a public source, is known to most interested market participants. It is a widely-used and commonly-accepted source of data for corporate social performance (Fombrun, 1996).

Despite the advantages of the KLD dataset, it is not free from criticism. One main criticism lies in the approaches of using KLD. For instance, Entine (2003) contended that researchers on social investment aggregate multiple dimensions within KLD into a single monolithic construct without a theoretical rationale or agreed-upon standards. Given this criticism, following prior literature (Godfrey et al., 2009), we categorized CSR scores into two domains, i.e., CSR toward primary and secondary stakeholders. Godfrey et al. (2009) explain how the two domains in CSR are theoretically distinct from each other in their roles. In addition, this categorization is supported empirically. Mattingly and Berman (2006) identified a pattern in the data, which is similar to this distinction in their exploratory factor analysis on the KLD dataset. In terms of construct validity, the measures developed by KLD have demonstrated robustness in several investigations.

Finally, we excluded firms in utility and finance industries from our sample,Footnote 2 as their operations are heavily regulated by government regulations and their profitability and valuation are not comparable to those in other industries, which may bias our results (Claessens et al., 2002; Dewenter & Warther, 1998). For example, Claessens et al. (2002) argue that “for financial firms, profitability and valuation data are difficult to calculate and to compare with firms in other sectors. For regulated utilities, profitability and valuation can be strongly influenced by government regulations.”

We obtain security price data from the Center for Research in Securities Prices (CRSP) and other financial variables from Compustat. After the removal of observations with missing key variables and firms in the finance and utility industries, our final sample consists of 28,716 news events released from 2007 to 2018 for 1,040 unique U.S. firms.

Measures of Variables and Models

Measures of Variables

Dependent Variable—Cumulative Abnormal Return (CAR)

We apply an event study methodology to examine the stock market’s reaction to negative news events, and our dependent variable is a market-adjusted CAR surrounding a news announcement. Determining the market reaction involves measuring daily abnormal returns (the difference between actual and expected returns). To control for the effects of market-wide fluctuations, we first estimate the following market model for each firm:

where Ri,t is return for firm i on day t; αi is the intercept; βi is the market beta for firm i; Rm,t is return on CRSP value-weighted return on day t; and εi,t is the error term.

We apply the market model to estimate expected returns over the period from 260 days before through 10 days before the news event. We use the CRSP value-weighted return to proxy for the market return. To minimize contamination of the event window, we conclude the estimation period at day 10. The returns are inclusive of dividends. Furthermore, it is possible that our normal return estimation can be biased by prior negative events during the estimation window. To alleviate this concern, we followed a prior study (Moenninghoff, 2018) and estimated expected returns excluding (−1, +1) days around negative events from the (− 260, − 10) normal return estimation window, if any negative events occurred within the normal return estimation window. Then, the abnormal return (AR) on day t is the difference between the actual return and the expected return derived from the market model, as follows:

Then, the market reaction to the news event (CAR) is the cumulative abnormal returns over a three-day window from one day before to one day after the news event day. Including day −1 is to ensure that early news leakage is captured, and including day + 1 is to ensure that the price impact of any news release after the market closed is captured. As the window becomes longer, more noise will be introduced. As a sensitivity test, when CAR was measured over an alternative three-day window of (0, + 2), the overall result was consistent.

CSR Toward Primary or Secondary Stakeholders

We include two independent variables to capture CSR toward primary stakeholders and CSR toward secondary stakeholders (Godfrey et al., 2009). KLD provides the social performance of each firm in the following dimensions: community; human rights; diversity; employee relations; and products. Each dimension involves a number of strengths and concerns in the KLD index. To represent CSR towards primary stakeholders, we aggregate the strength scores specifically for the product dimension and denote the sum score for the dimension as PCSR. We contend that the quality and innovation of products serve as a suitable proxy for a firm’s competence and directly influence primary stakeholders’ experiences and satisfaction. By focusing on the product dimension, we can effectively capture CSR efforts that directly benefit primary stakeholders. Regarding the employee relations dimension, although it directly relates to primary stakeholder groups, it provides limited insights into a company’s competence, which we argue is a crucial stimulus for triggering analytical information processing mode. Including both dimensions would make it challenging to discern which mechanism is influencing the observed outcomes. Thus, to maintain analytical clarity, we exclude the employee relations dimension from our analysis for CSR toward primary stakeholders.

Similarly, we calculate CSR towards secondary stakeholders by summing the strength scores for the community and diversity dimensions, defining the resulting sum score as SCSR. Secondary stakeholders, including local communities and advocacy groups, are particularly concerned with broader social and environmental impacts. Therefore, the community and diversity dimensions are highly relevant in assessing CSR towards these stakeholders. By engaging in community involvement and implementing diversity initiatives, companies demonstrate their commitment to addressing broader social issues and promoting inclusivity, both of which are key considerations for secondary stakeholders. Additionally, we exclude the human rights dimension from our analysis. This decision aligns with the approach taken by Godfrey et al. (2009). The human rights dimension encompasses considerations that relate to both primary and secondary stakeholders, particularly pertaining to a company’s respect for indigenous peoples’ intellectual property. Given the broader scope of this dimension, it is more appropriate to exclude it rather than isolating it within the primary or secondary stakeholder categories.

By carefully selecting and justifying the dimensions included in our study, we ensure the validity and relevance of our CSR measurement framework. We acknowledge, however, that alternative approaches with additional dimensions may warrant consideration for future research to further enhance the understanding of CSR towards both primary and secondary stakeholders.

Type of Negative Events

RepRisk collects news items according to 28 pre-defined issues. When an event is associated with products, we classify it as an event associated with primary stakeholders. When an event is associated with community or government, we classify it as an event associated with secondary stakeholders. The details of the classification are available upon request.

Some negative events are associated with both primary and secondary stakeholders. To avoid potential confounding effects, we exclude such events from our tests. Therefore, when we test the interaction effects between the types of negative events and the amplifying/insurance effects of CSR, we select events that are associated only with primary stakeholders or only with secondary stakeholders. We find that our results are robust when we perform tests with events associated with both primary and secondary stakeholders in the robustness analysis section.

Control Variables

When examining the stock market’s reaction to the report of negative news, we include several control variables in the models. First, we follow previous studies (Godfrey et al., 2009; Shiu & Yang, 2017) and include firm size and market-to-book ratio as controls. Firm size is measured as the natural logarithm of total assets, and the normalized market value of equity divided by the book value of equity is used as the market-to-book ratio.

Second, we control for several event characteristics, including the reach of the source, the novelty of events, and the severity of events. RepRisk determines the reach of the source by the readership/circulation of news sources. Low-influence sources include local media, small NGOs, local governmental bodies, blogs, and Internet sites. Medium-influence sources include most national and regional media, international NGOs, and state, national, and international governmental bodies. High-influence sources are a few international media, including the Financial Times, the New York Times, and the BBC. The novelty of events in RepRisk data is determined by the newness and originality of news, and by whether the firm had similar incidents in the past. For example, if a firm had many workplace injuries in the past, new workplace injuries would not be considered as novel incidents. Negative events in RepRisk are categorized into three levels in terms of severity: high, medium, and low severity. The severity level of each event is determined based on three equally-weighted sub-dimensions: the consequences of the risk incident (e.g., injury or death); the extent of the risk incident (e.g., the number of injuries or deaths); and the degree of deliberateness (e.g., by negligence, intent, or in a systematic way).

Estimation Models

When examining the stock market’s reaction to the report of negative news, we employ an event study methodology, which has been well established in the management (e.g., Kumar et al., 2015; Reuer, 2001) and financial economics (e.g., Peterson, 1989) literature. In our research context, the event study approach is a systematic procedure that captures fluctuations in stock prices, thereby reflecting the cognitive process of diverse stakeholders directly and indirectly. As mentioned previously, shareholders themselves are a type of stakeholder (Freeman et al., 2004). Furthermore, they consider perceptions and expected behavior of other stakeholders in terms of how they affect firm value. Prior studies on the role of CSR in the context of negative events commonly employed the event study approach based on these rationales (Schnietz & Epstein, 2005; Shiu & Yang, 2017).

In our estimation, we cannot rule out the possibility that multiple types of endogeneity might coexist. First, negative events in RepRisk may not occur randomly. For instance, it is possible that some social movement activists target large firms that enjoy the best reputation in CSR in order to grow the movements’ influence (King & Pearce, 2010). If the negative events in RepRisk are more likely to occur for large, reputable firms, our results based on the sample of negative events covered by RepRisk could be subject to sample selection bias. Second, our estimation is likely subject to other concerns of endogeneity, such as omitted variables and simultaneity, as well as endogenous selection of treatment variables. For example, certain firm attributes that are not controlled in the model may influence both CSR scores and CAR, possibly leading to a spurious correlation between them. In addition, firms may not select the level of their CSR engagement at random. This endogenous selection could affect CAR at the same time.

Prior studies mostly address the first endogeneity issue (i.e., sample selection bias) by implementing the Heckman (1979) two-stage regression approach, and the second endogeneity issue by performing two-stage least squares (2SLS) regression analyses using valid instrumental variables for the CSR scores. Since our estimation is possibly subject to both types of endogeneity issues, we follow prior studies (Liu et al., 2021; Wooldridge, 2010) and apply the Heckman-2SLS approach to mitigate both types of endogeneity concerns. The Heckman-2SLS approach combines the Heckman selection model with a 2SLS estimator that can solve the sample selection bias in the selection model, while simultaneously correcting for endogeneity problems resultant from omitted variables and endogenous selection of variables. To apply the the Heckman-2SLS model methodology, we first run a probit model to estimate the likelihood of the occurrence of RepRisk negative events with one exclusion restriction correlated with the selection equations and two instruments for the endogenous variables. We then compute the inverse Mills ratio (Lambda) from the first stage probit model estimates and incorporate it into the 2SLS structural equation where the endogenous test variables are replaced with their predicted values from their respective first stage models.

Specifically, in the first stage of Heckman selection, we apply a probit model to estimate the likelihood of the occurrence of RepRisk negative events using the entire firm-year observations in the KLD database as the sample, including both firms that have negative events captured by RepRisk in a given year and firms that do not. We use board independence as the exclusion restriction because it may affect the possibility for firms to engage in activities generating negative events (Kassinis & Vafeas, 2002), while its correlation with firm stock response to a specific negative event (i.e., CAR) is not significant (Klein, 1998).

In implementing a 2SLS approach to address the second type of endogeneity concern, valid instruments for the two endogenous variables, i.e., CSR strength score toward primary stakeholders (PCSR) and CSR strength score toward secondary stakeholders (SCSR), must meet two conditions: the relevance condition and the exclusion restriction. The relevance condition requires a nonzero correlation between the endogenous variable and the instrument. The exclusion restriction requires that the instrument is only indirectly related to the outcome variable (i.e., CAR) through its effect on the endogenous variable. We employ two geographic-based instruments for each endogenous variable because prior studies demonstrated robust evidence that the degree of CSR of a given firm in a particular area is influenced by the CSR of geographically proximate firms (Awaysheh et al., 2020; Husted et al., 2016), satisfying the relevance condition. In addition, these instruments plausibly meet the exclusion requirement because the geographic-based instruments are unlikely to be related to a firm’s current market valuation because the location of headquarters is mostly determined at the birth of the firm (Awaysheh et al., 2020).

Specifically, we choose CSRratio and CSRmean as plausible instrument variables for both PCSR and SCSR. CSRratio captures the concentration of local firms that are best-in-class (top 10%) for overall CSR performance (PCSR + SCSR). For each firm-year, we identify all firms headquartered within a 100-mile radius of each sample firm based on the firm’s headquarters zip code. Consistent with Awaysheh et al. (2020), we exclude any firms in the same industry classification as the focal firm and firms that are located in a different state. Then, CSRratio is measured by the number of firms that are best-in-class in overall CSR performance (top 10%) within their respective industries scaled by the total number of local firms. CSRmean indicates the average within-industry-year percentile total CSR score for all other firms (excluding the focal firm) headquartered in the same state as the focal firm. We include these instrumental variables in the first stage model of the Heckman approach, as well, following the guideline of Wooldridge (2010) in implementing the Heckman-2SLS approach. We note two important points for our instruments. First, our instrumental variables include industry information, but they are not industry averages. Rather, they are geographic-based instruments. Second, Larcker and Rusticus (2010) argue that industry-averages of endogenous variables are unlikely to be adequate instruments because a focal firm’s endogenous characteristics are likely related to the industry in which the firm operates. Since we exclude the focal firms and their industry peers when we construct our instruments, the instruments are unlikely to be influenced by the focal firm’s industry common effect.

Based on the discussion above, using the entire firm-year observations in the KLD database as the sample, the first stage model of the Heckman regression is constructed as follows:

where Event is coded as 1 if the firm has a negative event captured by RepRisk in year t, and 0 otherwise; BDInd is a dummy variable indicating whether or not the majority of directors in the nomination committee are outside, independent directors; Instruments is the vector of instrumental variables that are used in the 2SLS; and firm size (Atsize) and market-to-book ratio (MTB) are control variables.

From the first stage Heckman model above, we calculate the inverse Mills ratio (Lambda) and include it as a control variable in 2SLS, where we examine the relationship between CAR and PCSR or SCSR. The first and second stage 2SLS regression models are constructed as follows:

where Eq. (2) is the first stage regression of the Heckman-2SLS approach, in which PCSR (SCSR) is regressed on two instruments (CSRratio and CSRmean) and all controls used in Eq. (3); PCSR (SCSR) is a continuous variable that reflects the firm’s strength of CSR toward primary stakeholders (CSR toward secondary stakeholders) depending on the hypothesis that we are testing; Eq. (3) is the second stage regression of the Heckman-2SLS approach where the endogenous variables (PCSR or SCSR) are replaced with their predicted values (PCSRpredicted or SCSRpredicted) estimated from Eq. (2); CAR represents the cumulative abnormal return surrounding negative events; Lambda is the inverse Mills ratio to correct for potential sample selection bias; Atsize and MTB are control variables that are consistent with those used in the first stage; and Novelty, Source_ reach, and Severity are control variables describing the characteristics of negative events that are available for firms covered in the RepRisk database.

Results

Table 1 presents descriptive statistics, including the mean and standard deviation, of the variables used in our models and their pairwise correlations. Among the news characteristics provided by RepRisk, we find that Source_reach (i.e., the influence level of media delivering negative news) exhibits significant negative correlations with cumulative abnormal returns around negative events (CAR), Severity positively correlates with CAR, and Novelty does not show significant correlations with CAR. Table 2 provides the mean values of CAR (over the window − 1 to 1 days) and CAR2 (over the window 0–2 days) in each of the three news characteristics variables, Severity, Novelty, and Source_reach. It is found that as the level of Source_reach is higher, the mean values of both CAR and CAR2 are more negative. We find a similar pattern for Novelty. As Novelty increases from level 1 to level 2, the market response is more negative. As Severity increases from level 1 to level 2, however, the market response is less negative, but in level 3, the market response is the most negative. Significant correlations among the three variables—Severity, Source_reach, and Novelty—shown in Table 1 indicate possible interactions among the three variables.

The First Stage Regression of the Heckman Approach

Table 3 reports the results for the first stage regression of the standard Heckman approach, i.e., Eq. (1), where each probit model estimates the likelihood of occurrence of RepRisk negative events. Model 1 estimates inverse Mills ratio (Lambda) for the second stage regressions of the Heckman-2SLS approach, given that PCSR or SCSR might be endogenous. Models 2 and 3 are the first stage regressions of the standard Heckman approach to estimate another set of inverse Mills ratio (Lambda 1 and Lambda 2). We additionally estimate these two models because we find that the endogeneity of PCSR and SCSR in the second stage regressions of the Hechman-2SLS approach is not statistically significant, as explained later.

As expected, the coefficient on BdInd, which is included for the exclusion restriction, is positive and significant in all three models, indicating that the likelihood of occurrence of RepRisk negative events increases with the proportion of independent directors on the nomination committee. To evaluate the strength of our exclusion restriction, we examine the absolute value of correlation between the inverse Mills ratio and the independent variable of interest in the second stage, x, as well as the pseudo-R2 associated with the first stage model, following Certo et al. (2016). When compared to the criteria for exclusion restriction in Table 2 of Certo et al. (2016), our correlations (which are reported in the last row of Table 3) and pseudo-R2 (which are reported in the second-to-last row of Table 3) both exceed the benchmark for the strongest restriction case (IV). These results demonstrate that our exclusion restriction offered by BdInd is likely to be sufficient.

Tests for Validity of Instruments and Presence of Endogeneity

To provide support for our choice of instruments (either CSRratio or CSRmean), in each of the Heckman-2SLS regressions, we perform the following two tests: (1) the Cragg and Donald test to confirm the relevance of the instrumental variables (i.e., high correlations between the instrumental variables and PCSR or SCSR); and (2) the Sargan overidentification test to examine the exogeneity of the instrumental variables (i.e., no significant correlations between the instrumental variables and the error terms in the second stage regressions of the Heckman-2SLS models). The results are reported in the bottom section of Table 4, where the results for the second stage regressions for testing H1a, H1b, and H2 are provided. In each model of Table 4, the Cragg and Donald F-statistic (99.71 and 113.24) is much higher than the threshold value for relevance, 19.93 at 10% (Stock & Yogo, 2005), rejecting the null hypothesis that the instruments are weak. The p-values of the Sargan overidentifying restriction tests in all models are all greater than 0.1, indicating that our instrumental variables pass the exogeneity test. Therefore, we conclude that our models are unlikely to suffer from weak or invalid instrument concerns.

We next conduct tests for the presence of endogeneity in our primary analyses. The Durbin–Wu–Hausman test is performed to determine whether endogeneity exists in each model (Davidson & MacKinnon, 1993), and the results are reported in the bottom row of Table 4. We find that the p-value of the Durbin–Wu–Hausman test for both models is greater than 0.1, suggesting that endogeneity is not present in either Model 1 or 2.

Therefore, we test our hypotheses based on the results from the standard Heckman approach because prior studies indicate that endogeneity remediation in its absence yields less efficient estimates (Semadeni et al., 2014), and thus instrumenting for PCSR and SCSR is likely to lead to a loss of efficiency. The results from the second stage regressions of the standard Heckman approach are reported in Table 5. As previously discussed, for these second stage regressions, we include inverse Mills ratios estimated from Models 2 and 3 of Table 3, where the first stage probit regressions include confirmed-to-be-exogenous PCSR or SCSR as one of the regressors.

CSR Towards Primary Stakeholders (H1a and H1b)

Models 1 and 2 of Table 5 report the results for the second stage regression of the standard Heckman approach after the adjustment for sample selection bias by including Lambda 1 estimated from Model 2 of Table 3. The result of Model 1 shows that the coefficient on PCSR is negative (-0.0023) and significant (p < 0.01), suggesting that firms with good CSR toward primary stakeholders on average exhibit a risk-amplifying effect when negative events (without considering their contexts) occur. The result of Model 2 provides testing for H1a and H1b. As mentioned earlier, for the type of event variable, Issue_secondary_only (Issue_primary_only) is defined as 1 if a negative event is associated with secondary (primary) stakeholders but not associated with primary (secondary) stakeholders, and 0 otherwise. It is worth noting that we exclude mixed events, which affect both primary and secondary stakeholders. The result shows that while the coefficient of CSR toward primary stakeholders (PCSR) is statistically insignificant, the coefficient of the interaction between PCSR and the type of events associated with secondary stakeholders only (Issue_secondary_only) is negative (-0.0037) and significant (p < 0.01). This provides supporting evidence for our argument in H1a that CSR toward primary stakeholders is context-sensitive. Specifically, CSR toward primary stakeholders in the context of negative events provides a differential effect, depending on the nature of negative events.

In the simple slope analysis (Fig. 2a), we find that when negative events are associated with primary stakeholders, the line of CSR towards primary stakeholders is almost flat; whereas, when negative events are associated with secondary stakeholders, the line is downward. These patterns suggest that while CSR toward primary stakeholders has a risk-amplifying effect only when the negative events are associated with secondary stakeholders (in the domain of morality), the effect is negligible when the events are associated with primary stakeholders (in the domain of competence). These results support H1b, that the higher is a firm’s CSR performance toward primary stakeholders, the more negative is the market reaction to the negative events when the negative events are associated with secondary stakeholders than when the negative events are associated with primary stakeholders.

CSR Towards Secondary Stakeholders (H2 and H3)

Model 3 of Table 5 reports the results of the second stage regression of the standard Heckman approach for testing H2 where the sample selection is adjusted by Lambda 2 estimated from Model 3 of Table 3. We find a positive and statistically significant parameter (p < 0.01) for SCSR, providing support for H2: negative events result in a risk-tempering effect for firms with good CSR toward secondary stakeholders.

In Model 4 of Table 5, the coefficient of interaction between CSR toward secondary stakeholders (SCSR) and the type of events associated with secondary stakeholders only (Issue_secondary_only) is not significant, providing support for our prediction that the risk-tempering effect of CSR toward secondary stakeholders is less sensitive to the nature of events (H3). As anticipated, CSR toward secondary stakeholders provides an insurance effect even when the negative events are directly related to secondary stakeholders. In the simple slope analysis (Fig. 2b), we find that the risk-insurance effects have almost the same magnitude, irrespective of whether the negative event is associated with primary or secondary stakeholders. This is in accordance with an established theory that an affective reaction is likely to be stable in its directionality and magnitude (Kahneman & Tversky, 1979).

Robustness Analysis

We conduct some additional analyses to determine the robustness of our findings.

First, we perform tests for the interaction effects with hybrid events (i.e., those associated with both primary and secondary stakeholders). An insignificant impact of those events may inform us that the capital market participants do not agree about which factor should dominate. A one-sided response may reveal what the market participants consider material and what they do not.Footnote 3 To perform these tests, we create a new variable, Issue_hybrid, which is 1 if a negative event is related to both primary and secondary stakeholders. Issue_hybrid is coded 0 if a negative event is related to only secondary stakeholders. Then, we interact Issue_hybrid with PCSR and SCSR, respectively, to test how sensitive PCSR and SCSR are to the type of events. Table 6 reports the results of these tests. We find that the interaction between PCSR and Issue_hybrid is positive and significant in Model 2, while the coefficient of PSCR alone is negative and significant, suggesting that PSCR presents mixed effects when facing different types of negative events. When the events are associated with secondary stakeholders, PCSR has a stronger risk-amplifying effect. These results provide evidence supporting H1a and H1b, even when events are related to both primary and secondary stakeholders. The results from Model 4 also provide evidence supporting H3. We observe that the interaction between SCSR and Issue_hybrid is positive and insignificant (p > 0.1), while the coefficient of SCSR alone is positive and significant. These results suggest that SCSR provides an insurance effect, regardless of whether the event is related to both primary and secondary stakeholders or it is related only to secondary stakeholders.

Second, we repeat analyses after measuring CAR from a different window (denoted as CAR2), where CAR2 is the cumulative abnormal returns over a window from 0 to +2 days from the event day. Table 7 presents the results. Again, we test H1 to H3 using the standard Heckman approach. Overall, the results continue to provide evidence supporting H1-H3. The risk-amplifying effect of CSR toward primary stakeholders is context-sensitive and is stronger against negative events associated with secondary stakeholders only, thereby supporting H1a and H1b (see the result of Model 2). The CSR toward secondary stakeholders provides risk-tempering effects regardless of the type of stakeholders with which negative events are associated (see the result of Models 3 and 4). These results are in accordance with H2 and H3.

Finally, we test our hypotheses after controlling for another variable, CSR disclosure score. When a negative event occurs, stakeholders’ perceptions towards negative events are shaped significantly by their perceptions of the company. These perceptions are driven considerably by the company’s history of CSR/sustainability and its associated profile. Unlike in financial reporting, where strict rules determine the content, CSR reporting that lacks standardization gives the company management considerable leeway in terms of how the content is presented, and thus room for manipulating public perception. Therefore, we control for the perception of a firm’s CSR by including Bloomberg ESG disclosure scores of our sample firms which proxy for their CSR disclosure performance (Bernardi & Stark, 2018). We find that a substantial number of our sample firms have missing values of the disclosure score. To deal with missing values of the disclosure score, we followed previous literature and replaced missing values with the variable’s mean by year and industry. For example, Choudhury et al. (2021) state that “as a solution, missing values can be imputed. Missing numerical values can simply be replaced with the variable’s mean or median value and missing categorical values can be replaced with the mode.” As reported in Table 8, after this additional variable is controlled for in our model, our hypotheses are still all supported. The Bloomberg ESG disclosure score is the weighted overall disclosure score of social, environment, and governance dimensions. As an additional check, we tried to control for three individual dimension scores of firms instead of their overall score and continue to find that our inferences remain unchanged.

Discussion

This study theorizes that two types of CSR, in terms of whether they are targeted toward primary vs. secondary stakeholders, trigger different stakeholder information-processing modes, either analytic or affective, resulting in differential stakeholder reactions to outbreaks of negative events. We tested these arguments by examining the effects of CSR toward primary vs. secondary stakeholders on stock-market reaction to negative events and find supporting evidence for our predictions. CSR toward secondary stakeholders provides an insurance effect regardless of the type of negative events, while CSR toward primary stakeholders is sensitive to the nature of negative events. CSR toward primary stakeholders shows a salient amplifying effect when the negative event is associated with secondary stakeholders and becomes trivial when the negative event is associated with primary stakeholders only.

This study contributes to the extant literature mainly in three ways. First, it identifies the conditions under which there is a risk-amplifying effect of CSR, in that good CSR becomes a burden for a firm rather than a source of benefits. Prior literature has not systematically examined such a risk-amplifying effect. Even in the literature which theorizes a potential burden by high CSR performance, it highlights how it might affect particular behaviors of firms or media, rather than identifying the risk-amplifying effect itself and the underlying conditions. For example, Carlos and Lewis (2018) reported that some firms might hide their CSR-related award due to potential reputational threat. Wernicke (2016) showed that there is more media coverage of negative events by firms with a high reputation in CSR. This paper makes contributions to the literature by demonstrating that the risk-amplifying effect of CSR can be driven by a specific type of CSR (CSR toward primary stakeholders), and a specific negative event condition that triggers such an effect.

Second, CSR activities targeting secondary stakeholders are generally considered a liability due to their weak link to the value-generation process (Friedman, 1970; Hillman & Keim, 2001). Indeed, some earlier scholars, from the perspectives of shareholder capitalism and agency theory, criticized CSR activities, especially when they are targeted toward secondary stakeholders, such as social issue participation and philanthropy (Friedman, 1970; Godfrey, 2005; Hillman & Keim, 2001). Our study shows, however, that during negative events CSR toward secondary stakeholders may function more effectively as a safety asset, providing insulation from the shock of negative events. In contrast, CSR toward primary stakeholders may become a liability and under certain conditions amplifies the negative impact of the shock. In these ways, this study contributes to the literature by providing a more holistic understanding of the roles played by different CSR domains through value generation and value protection mechanisms.

Finally, our findings on the interaction between types of CSR and the nature of negative events shed light on the complex roles of different dimensions of CSR, and how they link to different information-processing modes. Our results provide evidence consistent with our argument that CSR toward secondary stakeholders forms moral capital, triggering the affective information-processing mode, and therefore functions as a safety asset regardless of the type of negative event. In contrast, CSR toward primary stakeholders triggers the analytical information-processing mode, and thus may become a burden following negative events (Rhee & Haunschild, 2006), especially when the negative events directly contradict stakeholders’ prior beliefs toward firms’ morality, instead of competence.

Limitations and Future Research

Similar to other empirical studies, this study possesses several limitations. First, in examining the effects of negative events on firms, we focused on stock returns, i.e., the reaction of stock-market participants to the negative event, with the assumption that stock-market participants incorporate the responses of other stakeholder groups. However, we are not able to directly examine the responses of specific stakeholder groups to the negative event. Future research may consider contexts that allow direct observations of the reactions of a particular group or multiple stakeholder groups, which would improve our understanding of this issue, as well as potential interactions between shareholders and other firm stakeholders. Furthermore, not all primary stakeholder groups have the same reaction to a certain negative event. For example, an employee may not react in the same way as a customer does to a negative event associated with a labour issue. Further study may consider more refined categorizations of stakeholders and negative events, which would contribute to an improved understanding of the underlying mechanism of the risk-tempering and risk-amplifying effect of CSR. Thirdly, while focusing on the role of good CSR, this study does not cover the role of bad CSR or firm irresponsible social actions toward primary and secondary stakeholders in the face of negative events. While it is beyond the scope of this study, this constitutes another interesting research topic that is worthy of future research. Moreover, we do not take into account contingencies where the boundary between secondary and primary stakeholders can be unclear. For example, in the utility industry, it is difficult to draw a clear line between direct customers (primary stakeholders) and the general public (secondary stakeholders), because in the modern world, we cannot live without electricity or water provided by utility firms. Even though our exclusion of utility and finance industries can alleviate the problem to some degree, we call for more accurate separation in future research. Finally, we admit that a more direct measurement of cognitive bias from the individual level would help to better illustrate our stakeholders’ information-processing mechanism. We call for future research to provide more first-hand data.

Managerial Implications

This study also offers some important implications for managers. It provides guidance to firms and their managers regarding the construction of CSR activities. The arguments and findings in this paper suggest that it is important to maintain a strategic balance between CSR towards primary and secondary stakeholders. If a firm was distinctive only in the dimension of CSR toward primary stakeholders, the firm would be penalized heavily without protection when a severe moral-related negative event occurs to the firm. However, if a firm was distinctive only in the dimension of CSR toward secondary stakeholders, the firm might end up paying too high a premium without sufficient value generation through cooperation with primary stakeholders.

Notes

We can also think about employment relations, which conceptually also constitutes CSR towards primary stakeholders. Long-term employment provided by the firm would contribute to accumulating the firm’s pure goodwill but may also be consistent with the firm’s transactional interests. However, such CSR endeavor is an indication of the firm’s goodwill, but not so much its competence.

Our main results remain qualitatively unchanged if we do not exclude these firms from our sample.

We are grateful to an anonymous reviewer for providing this point.

References

Anderson, N. H., & Butzin, C. A. (1974). Performance= motivation× ability: An integration-theoretical analysis. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 30(5), 598.

Awaysheh, A., Heron, R. A., Perry, T., & Wilson, J. I. (2020). On the relation between corporate social responsibility and financial performance. Strategic Management Journal, 41(6), 965–987.

Barney, J. B. (2018). Why resource-based theory’s model of profit appropriation must incorporate a stakeholder perspective. Strategic Management Journal, 39(13), 3305–3325.

Baron, D. P. (1995). Integrated strategy: Market and nonmarket components. California Management Review, 37(2), 47–65.

Baumeister, R. F., Bratslavsky, E., Finkenauer, C., & Vohs, K. D. (2001). Bad is stronger than good. Review of General Psychology, 5(4), 323.

Bernardi, C., & Stark, A. W. (2018). Environmental, social and governance disclosure, integrated reporting, and the accuracy of analyst forecasts. The British Accounting Review, 50(1), 16–31.

Bodenhausen, G. V., & Lichtenstein, M. (1987). Social stereotypes and information-processing strategies: The impact of task complexity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 52(5), 871.

Bundy, J., & Pfarrer, M. D. (2015). A burden of responsibility: The role of social approval at the onset of a crisis. Academy of Management Review, 40(3), 345–369.

Burgoon, J. K., & Hale, J. L. (1988). Nonverbal expectancy violations: Model elaboration and application to immediacy behaviors. Communications Monographs, 55(1), 58–79.

Burgoon, J. K., & LePoire, B. A. (1993). Effects of communication expectancies, actual communication, and expectancy disconfirmation on evaluations of communicators and their communication behavior. Human Communication Research, 20, 67–96.

Carlos, W. C., & Lewis, B. W. (2018). Strategic silence: Withholding certification status as a hypocrisy avoidance tactic. Administrative Science Quarterly, 63(1), 130–169.

Carroll, A. B. (1979). A three-dimensional conceptual model of corporate performance. Academy of Management Review, 4(4), 497–505.

Cerni, T., Curtis, G. J., & Colmar, S. (2010). Increasing transformational leadership by developing leaders’ information-processing systems. Journal of Leadership Studies, 4(3), 51–65.

Certo, S. T., Busenbark, J. R., Woo, H. S., & Semadeni, M. (2016). Sample selection bias and Heckman models in strategic management research. Strategic Management Journal, 37(13), 2639–2657.

Choi, J., & Wang, H. L. (2009). Stakeholder relations and the persistence of corporate financial performance. Strategic Management Journal, 30(8), 895–907.

Choudhury, P., Foroughi, C., & Larson, B. (2021). Work-from-anywhere: The productivity effects of geographic flexibility. Strategic Management Journal, 42(4), 655–683.

Claessens, S., Djankov, S., Fan, J. P., & Lang, L. H. (2002). Disentangling the incentive and entrenchment effects of large shareholdings. The Journal of Finance, 57(6), 2741–2771.

Clarkson, M. E. (1995). A stakeholder framework for analyzing and evaluating corporate social performance. Academy of Management Review, 20(1), 92–117.

Coombs, W. T. (2007). Attribution theory as a guide for post-crisis communication research. Public Relations Review, 33(2), 135–139.

Cyert, R. M., & March, J. G. (1963). A behavioral theory of the firm. Prentice Hall.

Davidson, R., & MacKinnon, J. G. (1993). Estimation and inference in econometrics. Oxford University Press.

Deephouse, D. L. (2000). Media reputation as a strategic resource: An integration of mass communication and resource-based theories. Journal of Management, 26(6), 1091–1112.

Dewenter, K. L., & Warther, V. A. (1998). Dividends, asymmetric information, and agency conflicts: Evidence from a comparison of the dividend policies of Japanese and US firms. The Journal of Finance, 53(3), 879–904.

Dowling, G. R. (2004). Corporate reputations: Should you compete on yours? California Management Review, 46(3), 19–36.

Entine, J. (2003). The myth of social investing: A critique of its practice and consequences for corporate social performance research. Organization and Environment, 16(3), 352–368.

Epstein, S. (1994). Integration of the cognitive and the psychodynamic unconscious. American Psychologist, 49(8), 709.

Epstein, S., Pacini, R., Denes-Raj, V., & Heier, H. (1996). Individual differences in intuitive–experiential and analytical–rational thinking styles. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 71(2), 390.

Fama, E. F. (1980). Agency problems and the theory of the firm. Journal of Political Economy, 88(2), 288–307.

Festinger, L. (1957). A theory of cognitive dissonance (Vol. 2). Stanford University Press.

Fiske, S. T., & Taylor, S. E. (2013). Social cognition: From brains to culture. Sage.

Fombrun, C. J. (1996). Reputation: Realizing value from the corporate image. Harvard Business School Press.

Freeman, R. E. (2010). Strategic management: A stakeholder approach. Cambridge University Press.

Freeman, R. E., Wicks, A. C., & Parmar, B. (2004). Stakeholder theory and “the corporate objective revisited.” Organization Science, 15(3), 364–369.

Friedman, M. (1970). A theoretical framework for monetary analysis. Journal of Political Economy, 78(2), 193–238.

Friedman, M. (1953). The methodology of positive economics. University Chicago Press.

Godfrey, P. C. (2005). The relationship between corporate philanthropy and shareholder wealth: A risk management perspective. Academy of Management Review, 30(4), 777–798.

Godfrey, P. C., Merrill, C. B., & Hansen, J. M. (2009). The relationship between corporate social responsibility and shareholder value: An empirical test of the risk management hypothesis. Strategic Management Journal, 30(4), 425–445.

Harmon-Jones, E., & Mills, J. (Eds.). (1999). Cognitive dissonance: Progress on a pivotal theory in social psychology. American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/10318-000

Heckman, J. J. (1979). Sample selection bias as a specification error. Econometrica, 47(1), 153–162.

Heider, F. (1958). The naive analysis of action. Psychology Press.

Hetze, K. (2016). Effects on the (CSR) reputation: CSR reporting discussed in the light of signalling and stakeholder perception theories. Corporate Reputation Review, 19(3), 281–296.

Hillman, A. J., & Keim, G. D. (2001). Shareholder value, stakeholder management, and social issues: What’s the bottom line? Strategic Management Journal, 22(2), 125–139.

Hsee, C. K., & Kunreuther, H. C. (2000). The affection effect in insurance decisions. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 20(2), 141–159.

Husted, B. W., Jamali, D., & Saffar, W. (2016). Near and dear? The role of location in CSR engagement. Strategic Management Journal, 37(10), 2050–2070.

Janney, J. J., & Gove, S. (2011). Reputation and corporate social responsibility aberrations, trends, and hypocrisy: Reactions to firm choices in the stock option backdating scandal. Journal of Management Studies, 48(7), 1562–1585.

Kahneman, D., & Tversky, A. (1979). Prospect theory: An analysis of decision under risk. Econometrica, 47(2), 263–291.

Kanouse, D. E. (1984). Explaining negativity biases in evaluation and choice behavior: Theory and research. ACR North American Advances.

Kassinis, G., & Vafeas, N. (2002). Corporate boards and outside stakeholders as determinants of environmental litigation. Strategic Management Journal, 23(5), 399–415.

King, B., & Pearce, N. (2010). The contentiousness of markets: Politics, social movements, and institutional change in markets. Annual Review of Sociology, 36, 249–267.

Klein, A. (1998). Firm performance and board committee structure. The Journal of Law and Economics, 41(1), 275–304.

Kölbel, J. F., Busch, T., & Jancso, L. M. (2017). How media coverage of corporate social irresponsibility increases financial risk. Strategic Management Journal, 38(11), 2266–2284.

Kumar, M. V., Shyam, D. J., & Francis, B. (2015). The impact of prior stock market reactions on risk taking in acquisitions. Strategic Management Journal, 36(13), 2111–2121.

Lange, D., & Washburn, N. T. (2012). Understanding attributions of corporate social irresponsibility. Academy of Management Review, 37(2), 300–326.

Larcker, D. F., & Rusticus, T. O. (2010). On the use of instrumental variables in accounting research. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 49(3), 186–205.

Liu, A. Z., Liu, A. X., Wang, R., & Xu, S. X. (2020). Too much of a good thing? The boomerang effect of firms’ investments on corporate social responsibility during product recalls. Journal of Management Studies, 57(8), 1437–1472.

Liu, W., Shao, X., De Sisto, M., & Li, W. H. (2021). A new approach for addressing endogeneity issues in the relationship between corporate social responsibility and corporate financial performance. Finance Research Letters, 39, 101623.

Lord, R. G., & Smith, J. E. (1983). Theoretical, information-processing, and situational factors affecting attribution theory models of organizational behavior. Academy of Management Review, 8(1), 50–60.

Martinko, M.J. (1995). The nature and function of attribution theory within the orgnizational sciences. Attribution Theory, 7–14.