Abstract

To call attention to and motivate action on ethical issues in business or society, messengers often criticize groups for wrongdoing and ask these groups to change their behavior. When criticizing target groups, messengers frequently identify and express concern about harm caused to a victim group, and in the process address a target group by criticizing them for causing this harm and imploring them to change. However, we find that when messengers criticize a target group for causing harm to a victim group in this way—expressing singular concern for the victim group—members of the target group infer, often incorrectly, that the messenger views the target group as less moral and unworthy of concern. This inferred lack of moral concern reduces criticism acceptance and prompts backlash from the target group. To address this problem, we introduce dual concern messaging—messages that simultaneously communicate that a target group causes harm to a victim group and express concern for the target group. A series of several experiments demonstrate that dual concern messages reduce inferences that a critical messenger lacks moral concern for the criticized target group, increase the persuasiveness of the criticism among members of the target group, and reduce backlash from consumers against a corporate messenger. When pursuing justice for victims of a target group, dual concern messages that communicate concern for the victim group as well as the target group are more effective in fostering openness toward criticism, rather than defensiveness, in a target group, thus setting the stage for change.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Expressing Dual Concern in Criticism for Wrongdoing: The Persuasive Power of Criticizing with Care

Participants in focus groups are often unfair to companies. Participants often take surveys too quickly and, at times, invest too little effort in their work. This needs to change.

I like participants in focus groups. I think they are good people. But participants in focus groups are often unfair to companies. Participants often take surveys too quickly and, at times, invest too little effort in their work. This needs to change.

Participants in focus groups are often unfair to companies. Participants often take surveys too quickly and, at times, invest too little effort in their work. This needs to change. But companies are also unfair to participants in focus groups. They often provide confusing instructions on tasks and sometimes do not even thank participants for their efforts. This also needs to change.

Each example above conveys the same criticism of participants in focus groups in the spirit of improving work. We suggest, however, that the various criticisms will likely result in divergent responses from the group which the criticism targets, in this case, the participants in focus groups. Research on group-directed criticism (e.g., Hornsey, 2005; Hornsey et al., 2004, 2007; Sutton et al., 2006) illustrates that whether individuals consider or reject criticism of their group depends on inferences about the messenger. If group members infer that a critical messenger has negative motivations for issuing criticism, then criticism is processed defensively.

Our research proposes that a frequent, and yet often mistaken, negative inference made when a messenger criticizes a target group is that the messenger lacks moral concern for the target group (i.e., views the target group as immoral and unworthy of concern). We suggest that messages which prevent this negative inference about messenger moral concern are more effective in promoting acceptance of criticism of one’s group. Indeed, recognizing that relatively direct, singular criticisms such as the one conveyed in the first example often fail to persuade target groups to change (Esposo et al., 2013; Rösler et al., 2021) and worse yet, often result in backlash against messengers, scholars have sought ways to increase the persuasiveness of critical messages. A common strategy involves the inclusion of positive statements about the target of the criticism, as can be seen in the second example above. However, we suggest that this strategy fails to address certain negative inferences about the moral concern that a messenger has for the criticized target, and thus fails to promote openness toward the criticism.

Our research thus introduces dual concern messaging, illustrated by the third example, which simultaneously criticizes and expresses concern for a target group. We suggest that dual concern messaging—because it involves criticizing with care—promotes the perception that a messenger has moral concern for the target group the messenger criticizes, and thus is more effective at persuading criticized target groups than alternatives such as including positive statements into criticisms (as in the second example). Further, we suggest that dual concern can be expressed effectively in at least two ways. First, dual concern can be expressed dyadically, for instance, by sharing concern about a harm done to the target group by the victim group—A harms B, but B also harms A. Second, dual concern can be expressed exo-dyadically by sharing concern about a harm done to the target group by a third party external to the target-victim dyad (for example, A harms B, but C also harms A).Footnote 1 Exo-dyadic expressions avoid potentially implicating a victim group in causing harm, as doing so may be untrue or otherwise problematic in certain situations.

Criticizing others for the harm they cause is increasingly common in business. Messengers from within organizations, such as internal whistleblowers, and journalists acting as watchdogs from outside of organizations frequently criticize target groups by calling attention to unfair practices or other actions which harm victim groups (Dworkin & Baucus, 1998; Park et al., 2020; Smaili & Arroyo, 2019). In addition, businesses and their representatives are increasingly weighing in on debates on sociopolitical issues (Branicki et al., 2021), criticizing target groups for the harm they cause to victim groups. For example, Ben & Jerry’s issued a statement criticizing the police for racism and brutality (Ben & Jerry’s 2020) and companies including Amazon, BlackRock, and Google criticized Republicans for enacting restrictive new voting laws (Gelles & Sorkin, 2021). Apple’s CEO Tim Cook criticized Conservatives for legislation allowing businesses to refuse to serve customers for religious reasons (Cook, 2015), and Whole Foods’ CEO John Mackey criticized Liberals for endorsing healthcare policies that took away certain freedoms from businesses (Keller, 2013). At a societal level, criticism-based activism can help to raise awareness about important problems and pressure organizations and lawmakers to enact change (Eilert & Nappier Cherup, 2020).

As messengers across various spheres of society encourage change by raising their voices to criticize target groups for harming victim groups, it is important to understand how target groups respond to this criticism. In particular, it is vital to understand when target groups will embrace or reject a call for change, as acceptance of criticism sets the stage for positive change (Hornsey et al., 2004). Before a problematic status quo can be overturned, group members must be open to legitimate criticism of their group. Thus, as messengers speak out on ethical issues, it is crucial to understand how they can increase the persuasiveness of criticism, particularly by avoiding defensiveness from criticized groups. Formally, we ask:

-

1.

Why do messages that criticize target groups for harm done to victim groups fail to persuade target groups?

-

2.

How can messengers increase the persuasiveness of their criticism among the target groups they are criticizing?

-

3.

In business contexts, how can messengers reduce consumer backlash from the target groups they are criticizing?

We draw on theories of group-directed criticism (Hornsey et al., 2007) and dyadic morality (Gray et al., 2014) to identify reasons why criticism for wrongdoing often backfires and propose a solution. First, we theorize that criticizing a target group fosters the (often false) assumption that the messenger has little moral concern for members of the target group. This assumption causes the targeted group to reject the criticism and further, in business contexts, can cause backlash from consumers. Second, we propose that messengers can mitigate these effects by communicating dual concern. By expressing dual concern, messengers can levy strong criticism of a target group while avoiding an appearance of indifference to the welfare of the criticized target group, thus preventing problems of criticism rejection and consumer backlash. A series of experiments supports these propositions.

Our research contributes to scholarship on business ethics in several ways. First, we add to the literature on group-directed criticism (Hornsey, 2005; Hornsey et al., 2004, 2007; Rösler et al., 2021; Sutton et al., 2006) by documenting dual concern as a strategy that encourages people to accept criticism of their group. We show that this strategy can be utilized even by outgroup members to effectively criticize target groups, which is notable as outgroup members face increased obstacles in getting target groups to accept their criticism (Hornsey & Imani, 2004; Hornsey et al., 2002). Second, we add to the literatures on corporate social responsibility and sociopolitical activism in organizations (Branicki et al., 2021; Groza et al., 2011) by delineating dual concern as a promising strategy even in tense, ideologically-motivated contexts. We identify message content, namely singular versus dual concern, which shapes whether company communications cause backlash. Finally, by introducing a strategy that can effectively persuade target groups to accept criticism of their problematic behavior, our research complements calls from scholars of business ethics to consider persuasion as a necessary force for creating an increasingly moral world of business (Brenkert, 2019).

Inferences About Messengers in Group-Directed Criticism

Many critical messages fail to sway the audiences they target, instead eliciting defensiveness. Theories of group-directed criticism (e.g., Hornsey, 2005) suggest that targets’ inferences about a messenger’s attitudes and intentions (e.g., the messenger’s motivation for issuing criticism of a group) shape whether defensiveness occurs. Essentially, when criticism is levied at a group, group members ask, “Why would the messenger say this?” The answer to this question influences whether criticism is rejected or taken to heart.

For example, Hornsey et al. (2004) illustrated that when members of criticized target groups believed that messengers were psychologically invested in the criticized group, members of the criticized target group attributed more constructive motives to the messenger (i.e., the messenger is critical because they want to improve the group). This attribution of more constructive motives, in turn, led members of criticized target groups to agree more with the messenger’s critical comments (see also Sutton et al., 2006). Thus, when deciding whether to accept group-directed criticism, a critical factor is what target group members believe about the messenger’s intentions toward the criticized target group. Essentially, when posing the question “Does the critic care about us?”, criticized target group members must answer “Yes” (Hornsey et al., 2008).

Indeed, the literature on group-directed criticism illustrates how critical it is to address potential negative inferences that can be made about a messenger and their motives. For example, Hornsey and Imani (2004) showed that whether critical messengers were attributed constructive motives for their comments was even more influential in shaping criticism acceptance than more ostensibly rational considerations such as a critical messenger’s expertise. If a messenger is perceived as having a group’s best interests at heart, the target group is more open to the messenger’s comments and their critical messages are more persuasive (Hornsey et al., 2007). Accordingly, research has explored communication strategies that foster positive inferences about a messenger’s intentions, such as “sweetening” criticism by accompanying it with positive feedback or acknowledging the failures of one’s own group while criticizing another (Hornsey et al., 2008).

Drawing on the insights from this literature, we suggest that one key inference made about a critical messenger is whether this messenger has moral concern for the target group. When considering the question “Does the critic care about us?”, we suggest that inferences about moral concern are critical as to whether target group members will answer “yes” or “no.” Perceptions of a group’s morality are particularly influential in the process of impression formation, driving individuals’ responses to groups (Goodwin, 2015). Thus, it may be expected that a messenger’s perceptions of a group’s morality are a major force in shaping the messenger’s reactions toward that group; if a messenger perceives a group as immoral, they are unlikely to respond positively. Further, research has found that when messengers criticize a target group for their moral failures (vs. failures related to competence), this kind of criticism is particularly likely to foster negative inferences about a messenger (e.g., that they do not have the group’s best interests at heart) and thus undermines the motivation to change for the better (Rösler et al., 2021). This is why levying criticism that risks implying immorality is particularly challenging. Answering the question “Does the critic think my group is moral?” is thus particularly critical, perhaps even more so than questions like “Does the critic like my group?” Thus, we suggest that if a messenger is perceived as lacking moral concern for a target group, their criticism will be rejected even if their messages may include some other favorable content toward the target group.

In sum, members of criticized target groups make inferences about a messenger and their motives for issuing criticism, and, “these inferences are crucial in determining whether criticisms will be received in an open-minded or defensive fashion” (Hornsey et al., 2004, p. 500). Research has considered how inferences are shaped by the messenger’s relationship to the criticized group (e.g., in-group vs. outgroup; Hornsey & Imani, 2004; Hornsey et al., 2002, 2004; Moreland & McMinn, 1999; Sutton et al., 2006) and whether the criticism is related to competence or morality (Rösler et al., 2021). Prior research has tested how such factors lead to inferences about a messenger’s psychological investment in a group (Hornsey et al., 2004, 2007) and bolster perceptions of constructive motives that promote criticism acceptance (Hornsey & Imani, 2004; Hornsey et al., 2007; Rösler et al., 2021; Sutton et al., 2006). In the current research, we examine a new factor related to the specific content of a message (i.e., whether it involves singular or dual concern) and test how this factor influences inferences about a messenger’s moral concern for members of the target group, as a critical inference that we suggest will determine how criticism is processed.

Singular Concern vs. Dual Concern in Critical Messages

Singular Concern

Criticism is almost inevitable when messengers attempt to persuade a target group to change their harmful behavior. Such statements indicate, either directly or indirectly, that a target group’s behavior is unacceptable, immoral, or negative. Critical messengers often express singular concern, accusing a target group of causing harm to a victim group and appealing to the target group to change. Singular concern focuses all explicit concern on the victim group.

Messengers may favor singular concern for many reasons. Intuitively, singular-concern messages are simple, clear, and potentially powerful. They also avoid drawing focus away from the sympathy one may want to show towards the victim group (Lerner & Simmons, 1966; Reich et al., 2020). Further, singular-concern messages may be more likely to resonate with people who already agree with the criticism of the target group, rallying ideologically-minded individuals to apply pressure to the offending group and motivate change (Biggs & Andrews, 2015).

However, critical messages often elicit defensive reactions from criticized target groups (Hornsey, 2005). People desire to view their selves as moral, rational, and caring, and thus tend to reject information that paints them or a valued social group unfavorably (Pronin et al., 2004). People are so motivated to defend a valued group against threats that they choose to expend their energy objecting to criticism over engaging in more enjoyable activities (Thürmer et al., 2019). Defensiveness may lead those whom a messenger is trying to persuade to reject the critical message, especially when criticism implies that a person’s group is immoral (Rösler et al., 2021). Thus, if one goal of critical messages is to encourage groups to see the error of their ways, and not just to appeal to those who already approve of the messenger’s stance (Stephan et al., 2016), singular concern messages are likely inadequate. Aspiring change-makers require strategies to criticize target groups without prompting defensiveness.

Dual Concern

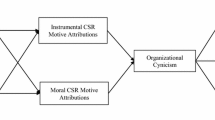

To overcome this barrier, we propose a novel persuasion strategy: dual concern. While singular-concern messages solely criticize a target group for harming a victim group, a dual concern message retains the firm and full criticism of the target group but pairs this criticism with an expression of concern for the criticized target group. See Fig. 1 for examples.

Critically, dual concern does not seek to minimize the original accusation of the target group (Reich et al., 2020). Rather, dual concern messages include an expression of moral concern for a target group alongside the firm criticism of the target group. Dual concern thus entails a messenger criticizing a target group and highlighting the need for change, while showing that the messenger still cares about the criticized target group’s welfare.

Perceptions of Messengers Who Criticize a Target Group

Why might dual concern messages be more effective than singular-concern messages? Research suggests that when singular concern is expressed, people infer that messengers have little concern for the criticized target group.

The theory of dyadic morality (Gray et al., 2014) states that people have a cognitive template for moral transgressions. This template includes two parties: an agent that acts upon another and causes harm and a patient, or victim, capable of being acted upon and experiencing harm. Thus, people are attuned to completing a moral dyad by identifying a causal agent to explain an observed harm. Further, agents elicit less sympathy than do patients (Schein & Gray, 2018). When a messenger criticizes a target group, the theory of dyadic morality suggests that the message places the target group in the role of an agent causing harm to the victim group. Thus, people may readily assume that messengers who place the target group in the role of an agent causing harm view this group as having lower moral standing and being less deserving of concern than others.

Relatedly, research on moral reproach suggests that people are quick to assume that individuals whom they perceive as being morally superior are judgmental of others who fall short. For example, meat eaters believe, often incorrectly, that vegetarians view meat eaters as immoral and that they regard themselves as morally superior to meat eaters (Minson & Monin, 2012). Further, people believe that consumers who purchase products for moral reasons harshly judge other consumers for making different choices (Zane et al., 2016). Thus, those who criticize a target group may readily be assumed to view that group as especially immoral. Further, given that individuals are sensitive to even small and indirect cues of being negatively judged (Howe & Monin, 2017), people may infer that a messenger views a criticized target group as immoral even when the messenger’s criticism of that group is not explicit. Criticizing target groups may thus place a messenger in a position of perceived moral superiority, leading the target groups to react negatively and lash out at the messenger (Monin et al., 2008; O’Connor & Monin, 2016).

Dual concern messages may help to minimize inferences of a lack of moral concern for a target group. Dual concern serves to break up the moral dyad template, such that the target group is identified as both an agent and a patient (i.e., victim). Placing the target group in this dual role of agent and patient may mitigate the assumption that a messenger views the target group as immoral. In sum, we propose:

-

H1:

When a messenger criticizes a target group for harming a victim group, target group members infer that the messenger has more moral concern for the target group when the messenger expresses dual concern compared to singular concern.

Reactions to Dual Concern Criticism

We have proposed that expressing dual concern will increase perceptions of a messenger’s moral concern for a target group, and that singular concern reduces these perceptions. If this is indeed the case, we suggest that when messengers express singular concern, target groups will be particularly likely to react defensively and refute the criticism that their group has harmed another group.

This proposition is supported by research on group-directed criticism, which as described above, has shown that the inference that a messenger does not have good intentions for making their criticism leads members of the criticized group to react defensively and disregard the criticism (e.g., Hornsey et al., 2004, 2007, 2008; Rösler et al., 2021). Believing that a messenger does not see a group as worthy of moral concern may be a strong signal that a messenger does not have a group’s best interests at heart when making critical comments. After all, if a group is viewed as immoral, why should a person give any consideration or energy to promoting positive outcomes for them? Thus, we suggest that perceptions of a messenger’s moral concern for a group will be a particularly important consideration to audiences weighing criticism of their group, and that criticisms which foster the inference that a messenger does not view a group as worthy of moral concern will be dismissed. In line with this thinking, research suggests that accusations of group immorality are particularly likely to lead to defensive reactions among groups (Rösler et al., 2021).

We anticipate that dual concern messages, by affirming that the messenger cares about the target group’s outcomes, will reduce negative inferences about a messenger’s moral concern for a target group. As a result, the target group members will have less reason to process criticism in a defensive manner and will be more likely to agree with the criticism of their group. Thus, we propose:

-

H2:

When a messenger criticizes a target group for harming a victim group, members of the target group are more likely to agree with the criticism when the messenger expresses dual rather than singular concern.

-

H3:

The increased acceptance of criticism prompted by dual versus singular concern is mediated by perceptions of increased moral concern for the target group.

For businesses, speaking out on important sociopolitical issues can garner support from consumers and stakeholders who support the company’s stance (Chatterji & Toffel, 2019; Hambrick & Wowak, 2021). As consumers have increasingly come to expect companies to act in ethically and socially responsible ways, companies could even face backlash for remaining silent on prominent sociopolitical issues (Bhagwat et al., 2020; Hoppner & Vadakkepatt, 2019; Minkes et al., 1999). Yet in business contexts, issuing criticism of groups is risky because it may alienate consumers who feel targeted by the criticism. For instance, consumers who disagree with a CEO’s ideological criticism have weaker purchase intentions at the CEO’s company (Chatterji & Toffel, 2019). This may happen because individuals infer that the messenger does not view their group as worthy of moral concern. By avoiding such an impression, dual concern messages may allow a company or corporate representative to criticize a group for harm done without prompting consumer backlash. Thus, we propose:

-

H4:

When a corporate messenger criticizes a target group for harming a victim group, members of the target group have higher purchase intentions at the messenger’s company when the messenger expresses dual versus singular concern.

-

H5:

The increased purchase intentions prompted by dual concern are mediated by perceptions of increased moral concern for the target group.

See Fig. 2 for our full conceptual model.

Distinguishing Dual Concern from Other Messaging

Dual concern messages are distinct from, and may often be advantageous over, other related persuasive strategies that risk being problematic when used in the context of criticizing a target group for harm. For example, dual concern messages preserve the full criticism (i.e., its severity) while providing additional information that reduces negative inferences about the messenger. This feature of dual concern messages distinguishes them from concessions (Cialdini et al., 1975) or the act of softening critical messages to reduce defensiveness. Making concessions may minimize the message’s urgency or the severity of a group’s transgressions and could thus fail to facilitate change. Such concessions may even antagonize a victim group which feels that the harm it faces is not being taken seriously.

Dual concern messages are also distinct from two-sided arguments, which are arguments that present positive and negative information (Eisend, 2006). Dual concern, more specifically dyadic dual concern, could be considered akin to a specific kind of two-sided argument, namely, one that presents harm caused by both parties to each other. However, we build on the literature on two-sided arguments in two ways: by documenting a specific mechanism through which dual concern functions, that is, by addressing inferences about moral concern; and by examining expressions of exo-dyadic concern that do not offer positive and negative information about both parties as does a two-sided argument, but rather specify the harm caused to two parties. Exo-dyadic dual concern avoids presenting both positive and negative information about a victim group, which could risk being perceived as victim blaming (Johnson et al., 2002).

Overview of Experiments

First, we document that individuals underestimate the degree to which a critical messenger truly has concern for members of a target group that they criticize for wrongdoing (see section Pilot Studies: Underestimation of Dual Concern). Then, we show that expressing dual concern, relative to singular concern, reduces the inference that a messenger has lower moral concern for the criticized target group (Studies 1–5), increases acceptance of the messenger’s criticism (Studies 1–5) and reduces backlash, bolstering purchase intentions at a critical messenger’s company (Study 3). Further, we demonstrate that dual concern is more effective at increasing criticism acceptance than pairing criticism with positive statements, highlighting the need to address inferences about moral concern specifically (Studies 1–2), that dual concern can be expressed exo-dyadically as well as dyadically (Study 4), and that dual concern has the same positive effects even when criticism of a target group is implicit rather than explicit (Study 5). See the supplemental Web Appendix for materials and detailed methods from all studies.

Pilot Studies: Underestimation of Dual Concern

To set the stage for our research, we conducted pilot studies examining whether messengers who are critical of a target group truly have lower moral concern for these target groups, or alternatively, whether people underestimate the actual level of concern that critical messengers have for the target group. Two pilot studies compared people’s estimates of the number of critical messengers who have concern for the target group they criticize with the actual number of critical messengers who expressed concern for members of a target group (see Web Appendix). Results reveal that members of target groups who are criticized believe that their critics have less concern for them than these critical messengers actually do.

Pilot Study 1: Estimating Concern Among Liberals and Conservatives

To assess the actual level of concern that critical messengers have for a criticized target group, we asked 160 Liberal participants on Amazon Mechanical Turk (MTurk) whether they agree that Conservatives are “hurting America and hurting many different groups in America.” A total of 150 (93.8%) responded “yes” and then were asked to choose which of two statements about Conservatives they agreed with more. One statement indicated concern for the criticized group: “Conservatives, like anyone, deserve a voice, and their concerns should be heard. We should care for Conservatives.” The second statement indicated no concern for the criticized group: “Conservatives do not deserve a voice, and their concerns should not be heard. We should not worry about caring for Conservatives.” The vast majority of Liberals (N = 131) showed concern for Conservatives by choosing the first statement (87.33%, CI = [81.95%, 92.72%]).

Likewise, 112 Conservative participants on MTurk indicated whether they agree that Liberals are “hurting America and hurting many different groups in America”. A total of 87 (77.7%) responded “yes” and then were asked the same questions as above, but about Liberals. The vast majority of Conservatives (N = 73) showed concern for Liberals (83.91%, CI = [76.03%, 91.79%]).

Then, to assess people’s estimated levels of concern among critical messengers, we recruited 79 Liberal participants and 52 Conservative participants on MTurk. We asked Liberals to estimate, of the Conservatives who criticized Liberals for harm, what percentage also showed concern for Liberals by selecting the concern (versus the non-concern) statement. Likewise, we asked Conservatives to estimate, of the Liberals who criticized Conservatives for harm, what percentage also showed concern for Conservatives by selecting the concern (versus the non-concern) statement.

Both Liberals and Conservatives predicted that only a minority of critical messengers would have concern for the criticized ideological group. Conservatives estimated on average that 40.78% of Liberal critical messengers would have concern for Conservatives (95% CI = [33.39%, 48.17%]). Liberals estimated on average that 35.34% of Conservative critical messengers would have concern for Liberals (95% CI = [29.62%, 41.07%]). These estimates are equivalent to less than half of the true level of concern that Conservatives and Liberals held for their ideological opponents.

Pilot Study 2: Estimating Concern Among Criticizers of Police Discrimination

We asked 265 participants on MTurk whether they agree that police discrimination against Black Americans is one of the “most important issues” in the United States. To assess the actual level of concern that critical messengers have for a criticized target group, participants who said “yes” to this statement (N = 172, 64.9%) were then asked to choose “yes” or “no” as to whether they agreed with a statement about how police officers are victims of “many unfair and harmful policies” and should receive more benefits and support. The majority of criticizers of the police (N = 96) showed concern for the police by choosing that they agreed with the statement (55.81%, CI = [43.32%, 63.31%]).

To assess people’s estimated levels of concern among critical messengers, we then asked the participants on MTurk who had said “no” to the statement that police discrimination against Black Americans is one of the most important issues in the U.S. (N = 93, 35.1%) to estimate, among the people who agreed that police discrimination against Black Americans is one of the most important issues in the U.S., the percentage who chose that they agreed with the statement that the police are victims of “many unfair and harmful policies.” These participants again predicted that only a minority of those who criticize the police would show concern for the police, estimating that 28.95% (95% CI = [23.62%, 34.27%]) of critical messengers would express concern for the police. As demonstrated in Fig. 3, the true level of concern among those who criticized the police was almost double this number.

Pilot Studies: Critical messengers’ actual level of concern for target group versus estimates of critical messengers’ concern. Note. Actual messenger concern is the percentage of critical messengers who agreed with a statement of concern for a target group that they had criticized for causing harm. Estimated messenger concern is the estimates of target group members of the percentage of critical messengers that agreed with a statement of concern for the target group they had criticized for causing harm. Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals

Discussion of Pilot Studies

We find that the majority of critical messengers of a target group also agreed with a statement of concern for the target group. Yet, messengers’ concern for target groups was underestimated. Thus, explicitly expressing dual concern in critical messages may be a way for messengers to honestly and meaningfully rectify the often-mistaken assumption that those who criticize do not care about the target of their criticism.

Study 1: Dual Concern in a Workplace Context

Our pilot studies established a problem: members of a criticized target group underestimate the extent to which critical messengers have moral concern for the target group. Given this finding, we next tested in Study 1 whether it may be beneficial for a critical messenger to explicitly express dual concern for a criticized target group. In the context of calling for change in harmful behavior in a workplace setting, we examined whether the expression of dual concern by a critical messenger, relative to singular concern, increases perceptions of moral concern (Hypothesis 1) and increases target group agreement with messenger criticism (Hypotheses 2 and 3). Further, to test whether these effects are unique to a messenger expressing dual concern and operate through specific inferences about moral concern rather than, for instance, general liking or general credibility, we compared dual concern messages with a singular-concern message that included a statement of positive regard for the target group such as “I like this group”, but not a statement of moral concern. We therefore tested whether dual concern messages have a stronger effect on persuasion than singular-concern messages that include a positive statement.

Method

Two hundred and nineteen participants (131 female, 86 male, Mage = 35.29) completed a study via MTurk described as being about MTurk. This study leverages the environment of MTurk and actual existing tensions between Requesters and Workers in the context of proposed organizational changes. All participants in this and subsequent studies passed an attention check (see Web Appendix).

Participants were first reminded: “On the platform you are called a ‘Worker’, and an organization that posts hits and pays Workers is called a ‘Requester’.” They were then randomly assigned to one of three conditions—singular concern, singular concern + positive statement, or dual concern—and read a statement from a supposed tech industry professional. In all conditions, the tech professional indicated that MTurk should be improved for Requesters (the victim group) and criticized Workers, or the target group, for harming Requesters, stating: “Workers often take surveys quicker than they should and do bad work. Workers’ work should be regulated more tightly.” In the singular concern + positive statement condition only, beginning and concluding positive phrases about Workers such as “I like Workers” and “I like Workers a lot” were added to the message. In the dual concern condition only, the statement also mentioned that the situation should be improved for Workers and that Requesters were doing some unfair things to Workers. Specifically, the following lines were added: “I am concerned for Workers. Requesters often create confusing assignments. Many Requesters do not even thank Workers. Requesters often have a dismissive attitude toward Workers and Workers’ concerns,” and the statement concluded by acknowledging the harm done by each party: “Both of these things need to change.”

Next, participants indicated their agreement with the criticism of their group by indicating agreement with two items on a scale from 1 = “strongly disagree” to 7 = “strongly agree” that was aggregated into a single measure (r = 0.450, p < 0.001). The statements were pulled directly from the stimuli read by the participants: “Workers are often unfair to Requesters” and “Workers’ work should be regulated more tightly.”

Participants then made inferences about the tech professional’s moral concern for the Workers on a two-item moral concern measure based on items used by Minson and Monin (2012). The two statements read: “The person from the statement you read generally believes Requesters are __________ morally superior to Workers” and “When taking action to help Requesters, the person from the statement would ____________ about any negative impacts for Workers,” with 7-point scales anchored, respectively, from 1 = “not at all” to 7 = “very much” and from 1 = “not be concerned at all” to 7 = “be very concerned” (r = 0.389, p < 0.001).

Results

To test H1, we conducted a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with the variable indicating condition (3 levels) predicting perceived moral concern for the target group. This analysis revealed a significant effect of condition, F(2,216) = 31.386, p < 0.001. Inferences of moral concern were higher when the messenger used dual concern (M = 4.11, SD = 1.06) than singular concern (M = 2.82, SD = 1.26), F(2,216) = 44.199, p < 0.001, or singular concern plus a general positive statement (M = 2.74, SD = 1.17), F(2,216) = 50.094, p < 0.001. Additionally, the singular concern + positive statement condition was not significantly higher in perceived moral concern than the singular concern condition, F(2,216) = 0.167, p = 0.683. Thus, H1 was supported.

Next, to test H2, we conducted a one-way ANOVA predicting agreement with the criticism with the variable indicating the message condition (3 levels). This revealed a significant effect of message condition, F(2,216) = 4.63, p = 0.011. MTurk participants, who are themselves Workers and thus members of the criticized target group, agreed significantly more with the criticism about Workers when the messenger also expressed concern for them (dual concern, M = 3.92, SD = 1.19) than when the messenger did not (singular concern, M = 3.28, SD = 1.48), F(2,216) = 8.239, p = 0.005 and when the messenger affirmed general liking of Workers (singular concern + positive statement, M = 3.41, SD = 1.35), F(2,216) = 5.39, p = 0.021. Thus, as can be seen in Fig. 4, H2 was supported in both instances. Adding a positive statement to a singular concern message did not improve persuasion relative to expressing singular concern only, F(2, 216) = 0.314, p = 0.576.

Study 1: Effect of dual concern versus 1. singular concern and 2. singular concern plus a positive statement on moral concern and persuasion when criticizing a target group (Workers) for causing harm to a victim group (Requesters) in a workplace context (Amazon’s Mechanical Turk). Note. Error bars represent standard error of the mean. All items are on a 7-point scale, on which 1 = most negative and 7 = most positive. ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05

Did this positive persuasive effect of dual concern emerge because dual concern changed perceptions of a messenger’s moral concern for the target group (H3)? Perceptions of moral concern positively predicted the dependent variable of agreement with the criticism (B = 0.424, SE = 0.064, p < 0.001). Two simple mediation bootstrapping procedures in a PROCESS SPSS macro (Model 4; 5,000 bootstraps) (Hayes, 2012) were conducted: one model with the conditions dual concern coded as 1 and singular concern coded as 0, and a second model with dual concern coded as 1 and singular concern + positive statement coded as 0. Both revealed a significant indirect effect of moral concern inferences on agreement with criticism (dual versus singular concern: B = 0.529, SE = 0.146, 95% CI = [0.2872, 0.8725]; dual concern versus positive statement: B = 0.496, SE = 0.147, 95% CI = [0.2458, 0.8197]). Thus, H3 was supported.

Discussion

This study shows that dual concern messages can be more effective than singular-concern messages when trying to persuade members of a target group to agree with criticism about their own group. Gig workers on MTurk were more likely to agree that they are unfair to their freelance employers when the criticism was paired with concern for their own well-being. This effect emerged because dual concern messages increased the perception that the critical messenger was morally concerned about the target group whose actions they were criticizing.

Further, dual concern messages were more effective than singular-concern messages that included a positive statement about the target group. This finding that adding a simple statement of positive regard to a singular concern message was not as effective at improving criticism acceptance as a dual concern message supports the idea that dual concern messages do not function by simply indicating general positive regard for a criticized target group or increasing a messenger’s general likability. This finding also suggests that effects are not driven by complementing positive information with negative information in ways that might enhance credibility like a two-sided argument. Only expressions of dual concern helped to rectify the perception that a critical messenger has less moral concern for a target group and therefore had positive persuasive effects.

The finding that merely adding a positive statement to a singular-concern message did not significantly improve receptiveness to criticism, relative to expressing criticism only, is in contrast to some previous research, which found that pairing praise with criticism had a small positive effect on agreement with criticism (Hornsey et al., 2008). Perhaps the null effect in the current study occurred because the positive statement was relatively superficial, rather than being more specific positive praise, and people are skeptical of the veracity of such statements of general positive regard when connected to criticism.

Study 2: Dual Concern in a Sociopolitical Context

Building on the results of Study 1, we examined whether effects would replicate in a different and ideologically tense context, that of convincing members of a political party to change their behavior toward the opposing party. Given that political identity is an important aspect of the self for many individuals, defensiveness may be especially pronounced in contexts involving sociopolitical issues (Federico & Ekstrom, 2018). In this sensitive context, would expressing dual concern effectively convey that a critical messenger holds moral concern for a target group they are criticizing for wrongdoing (Hypothesis 1), and would this increase the persuasiveness of their criticism (Hypotheses 2 and 3)?

Method

One hundred and thirty-nine self-identified Democrat participants (70 female, 69 male, MAge = 36.53) were recruited on MTurk for a study about politics. Participants were randomly assigned to read one of two statements from a supposed political Independent. In both conditions, the messenger criticized Democrats for “cruel prejudice” toward Republicans. In the singular concern + positive statement condition, the messenger also stated: “I like Democrats a lot” and “I think (Democrats) are good people”. In the dual concern condition, the messenger also showed concern for the target group, the Democrats, by mentioning that Republicans also harm Democrats: “Republicans are often very mean and prejudiced against Democrats.”

Next, participants specified how much they agreed with the criticism by indicating agreement with statements drawn directly from the materials such as “There is a lot of cruel prejudice against Republicans by Democrats” (1 = “strongly disagree” and 7 = “strongly agree”). Participants then made inferences about the messenger’s moral concern for the target group, the Democrats, on the same two-item moral concern measure as in Study 1: “When taking action to help Republicans, Johnson Michael would __________ any negative impacts on Democrats” (1 = “not be concerned at all about” to 7 = “be very concerned about”) and “Johnson Michael generally believes Republicans are _____ morally superior to Democrats” (1 = “not at all” to 7 = “very much”) (r = 0.423, p < 0.001).Footnote 2

Results and Discussion

The Democrat participants, members of the criticized target group, inferred that the messenger had greater moral concern for Democrats when the messenger expressed dual concern (Mdual = 4.75, SD = 1.47) than when the messenger expressed singular concern + positive statement (Msingular+positive = 3.61, SD = 1.38), t(137) = 4.723, p < 0.001, again supporting H1. As can be seen in Fig. 5, participants also agreed more with the messenger’s criticism that Democrats are being cruel to Republicans when the messenger expressed dual concern for Democrats (Mdual = 4.00, SD = 1.70) than when the messenger simply affirmed personal liking for Democrats (Msingular+positive = 2.60, SD = 1.73), t(137) = 4.500, p < 0.001, again supporting H2.

Study 2: Effect of dual concern versus singular concern paired with a general positive statement on moral concern and persuasion when criticizing a target group (Democrats) for harming a victim group (Republicans) in a sociopolitical context (U.S. politics). Note. Error bars represent standard error of the mean. All items are on a 7-point scale on which 1 = most negative and 7 = most positive. ***p < 0.001

Increased perceptions of moral concern again mediated the positive effect of dual concern on agreement with the criticism. Moral concern positively predicted agreement with the criticism, B = 0.450, SE = 0.094, p < 0.001. Mediation analysis (dual concern = 1, singular concern + positive = 0) revealed a significant indirect effect of moral concern on agreement with the criticism (95% CI = [0.1325, 0.7296]), thus supporting H3.

Study 3: Dual Concern and Consumer Backlash

When a CEO of a corporation criticizes a political group for wrongdoing, do dual concern messages increase the criticism’s effectiveness? In addition to testing the hypothesized effects of dual (vs. singular) concern on moral concern and target group agreement (H1-H3), Study 3 tests whether expressing dual concern reduces backlash against the messenger (H4 and H5).

Method

Participants and Procedure

Using Prolific filters, we aimed to recruit 100 self-identified Republican participants and 100 self-identified Democrat participants for a study about news articles. After eliminating participants who failed to confirm their political affiliation, we retained 97 Democrat and 92 Republican (109 women, 79 men, 1 non-binary, MAge = 36.34)Footnote 3 participants who completed the full study.

Next, participants were randomly assigned to read one of two news article excerpts, which expressed either singular concern or dual concern. In the articles, CEO Steven Coffey of an outdoor sports company, described as a political Independent, criticized the participant’s associated political group. That is, Republicans read that Coffey criticized Conservatives and Democrats read that Coffey criticized Liberals. In the singular concern condition, the headline read “CEO of outdoor sports store criticizes [Conservatives/Liberals]” and Coffey stated “Modern [conservative/liberal] ideology is hurting different groups of Americans. […] [Conservatives/Liberals] really need to reconsider some of their policies moving forward or it will set the country on a problematic path.” The dual concern condition included the same criticism as the singular concern condition, but, in addition, Coffey expressed concern for members of the target group, stating for example: “[Conservatives/Liberals], like anyone, deserve a voice, and their concerns should be heard.”

Next, participants reported their purchase intentions at the critical messenger’s company by answering items similar to those used in past research (3 items, α = 0.89, 1 = “very unlikely”, 7 = “very likely”; Groza et al., 2011) and indicated how much they agreed with the content of the criticism, again taking statements pulled directly from the materials (2 items, r = 0.742, p < 0.001, 1 = “strongly disagree”, 7 = “strongly agree”). Inferred moral concern was measured using the same items as previous studies (2 items, r = 0.537, p < 0.001).

Results

There were no significant interactions between message condition (singular versus dual concern) and participant political affiliation (Democrat versus Republican) for any measure, all Fs < 2.42, all ps > 0.121, indicating that singular and dual concern messages have similar effects for both criticized target groups. Thus, we collapsed across party affiliation in all analyses. Results do not differ if we control for party affiliation.

Participants inferred that the messenger, CEO Steven Coffey, had greater moral concern for the target group when the message expressed dual concern (Mdual = 4.02, SD = 1.16) than when the message expressed singular concern (Msingular = 2.82, SD = 1.13), t(187) = 7.248, p < 0.001, thus supporting H1.

In line with H2, participants expressed somewhat more agreement with the messenger’s criticism when the messenger expressed dual concern (Mdual = 3.64, SD = 1.52) than singular concern (Msingular = 3.18, SD = 1.67), t(187) = 1.952, p = 0.052, though this difference did not reach conventional significance thresholds. Supporting H3, however, there was a significant indirect effect such that the dual concern message increased perceived moral concern, which then positively predicted agreement with the criticism. Moral concern positively predicted agreement with the criticism, B = 0.557, SE = 0.094, p < 0.001, and mediation analysis (5000 bootstraps; dual concern = 1, positive control condition = 0) revealed a significant indirect effect of moral concern on agreement with the criticism (95% CI = [0.4004, 0.9900]).

Supporting H4, participants had stronger purchase intentions when the messenger expressed dual concern (Mdual = 3.96, SD = 1.44) than singular concern (Msingular = 3.46, SD = 1.47), t(187) = 2.33, p = 0.021. Supporting H5, increased perceived moral concern also mediated the positive effect of dual concern on purchase intentions. Moral concern positively predicted purchase intentions, B = 0.559, SE = 0.084, p < 0.001. Mediation analysis revealed a significant indirect effect of these moral concern inferences on agreement with criticism (95% CI = [0.4234, 0.9700]). See Fig. 6.

Study 3: Effect of dual concern versus singular concern on moral concern, persuasion, and purchase intentions when a CEO criticizes a political group (Conservatives or Liberals) for causing harm to America. Note. Error bars represent standard error of the mean. All items are on a 7-point scale on which 1 = most negative and 7 = most positive. ***p < 0.001, *p < 0.05, +p < 0.10

Discussion

Dual concern (vs. singular concern) messages heightened the sense that a CEO who criticized a political target group nonetheless held moral concern for that group. This higher perceived moral concern prompted individuals from the criticized target group to be more open to the CEO’s criticism and further, to maintain stronger purchase intentions at the CEO’s company.

Study 4: Exo-Dyadic Dual Concern and Persuasion

Previous studies focused on dyadic dual concern messages, which may be problematic in certain situations, particularly as they may risk implicating the victim group in wrongdoing. Thus, this study tests whether exo-dyadic dual concern messages, which express concern about harm caused to the target group by a third party external to the target-victim dyad, bolster perceived moral concern of the messenger and persuasion (H1–H3).

Method

Participants

One hundred and sixteen MTurk participants (57 Female, 59 Male, MAge = 34.37) physically located in California completed the survey after and answering “yes” to the questions “Do you currently live in California?” and “In general, do you agree with the statement ‘California is awesome. I enjoy California’?”.Footnote 4

Procedure

After answering a filler question about their favorite locations in California, participants were randomly assigned to read one of two articles about California. In the singular concern condition, the participants read a short article summary from a supposed journalist who criticized California for unfairly harming Mexico, stating: “California is unfairly treating Mexico and its people in many ways. Much of this is because of California’s economic policies with Mexico. California needs to make more efforts to strongly reach out to Mexico.”

In the dual concern condition, the participants read the same article summary together with another article summary in which the journalist added that California had been unfairly harmed by the U.S. government in an unrelated way. The second article summary mentioned: “One must also have sympathy for California. Unrelated to its relations with Mexico, California is the victim in another story. The United States government continues to unfairly engage with California, restricting many of its dealings and business practices that would improve things for California and Californians.”

Participants then reported how much they agreed with the criticisms taken from the materials: “California is unfairly treating Mexico and its people in many ways,” and “California needs to make more efforts to strongly reach out to Mexico” (1 = “strongly disagree” to 7 = “strongly agree”, r = 0.602, p < 0.001).

Next, participants made inferences about the journalist’s moral concern for California on the same two-item measure as in previous studies (r = 0.281, p = 0.002).

Results and Discussion

In this study, a journalist criticized California for harming Mexico. Self-professed state-loving residents of California inferred that the critical messenger, the journalist, had more moral concern for the criticized target group, Californians, when the messenger employed exo-dyadic dual concern (Mdual = 4.11, SD = 1.17), rather than singular concern (Msingular = 3.55, SD = 1.25), t(114) = 2.492, p = 0.014, thus supporting H1.

In addition, as can be seen in Fig. 7, when the messenger also expressed concern for harm done to California by the U.S. government (exo-dyadic dual concern), the target group agreed more with the messenger’s criticism of their group (Mdual = 3.23, SD = 1.05) than when the messenger did not express concern for the target group (singular concern condition) (Msingular = 2.67, SD = 1.16), t(114) = 2.748, p = 0.007, therefore supporting H2.

Study 4: Effect of exo-dyadic dual concern versus singular concern on moral concern and persuasion when a journalist criticizes one government (California) for causing harm to another (Mexico). Note. Error bars represent standard error of the mean. All items are on a 7-point scale on which 1 = most negative and 7 = most positive. **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05

Further, inferences of moral concern positively predicted agreement with the criticism (B = 0.303, SE = 0.081, p < 0.001). Mediation analysis (dual concern = 1, singular concern = 0) indicated a significant indirect effect of these moral concern inferences on agreement with criticism (95% CI = [0.0310, 0.3617]), supporting H3.

Study 4 reveals that exo-dyadic dual concern messages have similar effects as dyadic dual concern messages, increasing perceived moral concern and message persuasiveness. Thus, dual concern can be expressed by stating that a target group is harmed by an external entity, rather than by the victim group involved in the target-victim dyad. This study reiterates the importance of inferences about moral concern underlying the success of dual-concern messages; effects are not driven simply by, for instance, enhancing messenger credibility by being equally critical of the two groups in a dyad as in a two-sided argument.

Study 5: Implicit Dual Concern

Given people’s sensitivity to criticism, we might expect that an individual would infer criticism of their group even when a messenger simply identifies a disfavored ideological group as a victim of harm. For example, if a messenger states that “Liberals are victims of much unfair prejudice,” then one might infer that Conservatives, as the ideological opponents of Liberals, are implicitly viewed by the messenger as perpetrating that prejudice, even if the messenger does not explicitly accuse Conservatives of causing harm. We predicted that even in the context of an indirect criticism for harm such as this, a dual concern message would increase criticism acceptance, which would be mediated by perceptions of moral concern. This study tests dual concern’s effects in a new format of communications that is reflective of strategies used in anti-prejudice campaigns or other types of public service announcements.

Method

Participants

One hundred twenty-five U.S. participants (78 female, 46 male, 1 non-binary/other, MAge = 33) completed the study on MTurk.

Procedure

Participants were told that the survey would be about controversial issues and that they would receive relevant content depending on their answers. From among the following list, participants were asked to select a group with whose opinions they strongly disagreed: Liberals, Conservatives, atheists, Christians, rural people, urban people, the elderly, millennials, students, and the working class. The group selected by each participant became the victim group supported in a poster campaign.

Most participants in the study (N = 81, 64.8%) selected a group with which they disagreed due to differences in political ideology. Fifty-five participants (44.0%) selected Conservatives as the group with which they disagreed, and 26 participants selected Liberals (20.8%). The next most commonly selected groups were Christians (N = 12, 9.6%), atheists (N = 11, 8.8%), the elderly (N = 11, 8.8%), students (N = 4, 3.2%), and millennials (N = 3, 2.4%). All other groups were selected once or less. Study condition did not interact with the group selected on either the agreement or the moral concern measures (ps > 0.3), so analyses were collapsed across all selected groups.

Participants were randomly assigned to either the singular concern or dual concern condition. In the singular concern condition, each participant viewed a poster from a group named Stop Now, which demanded that prejudice against the participant’s disfavored group be stopped. For example, if a participant indicated that they disagree with Liberals, the poster advocated ending prejudice against Liberals. The advertisement further stated: “Visit our website to learn more about the unfair specific prejudices [selected group] face at school, at work, and in the media.” The criticism implicit in this poster is that people who disagree with this group, such as the participants, are among those who often express prejudice toward this group.

In the dual concern condition, participants viewed the same poster together with an additional poster from Stop Now titled “Stop Prejudice Everywhere.” This poster stated that Stop Now supports stopping prejudice against many other groups and listed all the groups that were presented earlier in the study, together with Americans, internationals, minorities, and Muslims. The text included in the poster encouraged people to go online to learn about the various unfair prejudices faced by each group. In this manner, the poster demonstrated how Stop Now has shown concern for many different groups beyond the participants’ disfavored group, which also meant that Stop Now had shown concern for groups into which the participants fall.

Participants then indicated their agreement with the statement: “There are unfair specific prejudices [selected group] face at school, at work, and in the media” (1 = “strongly disagree” and 6 = “strongly agree”). Afterwards, participants completed a similar two-item moral concern measure as in the previous studies (r = 0.380, p < 0.001).

Results

Dual concern messages fostered the perception that the messenger also had moral concern for other groups. Participants inferred that the advocacy group had greater moral concern for other groups in the United States when it expressed concern via the second poster (Mdual = 3.20, SD = 1.43) than when it expressed only singular concern (Msingular = 2.60, SD = 1.27), t(123) = 5.126, p < 0.001, supporting H1. Participants were also more likely to agree that unfair prejudice exists against their disfavored group when presented with a second poster from the same advocacy group expressing concern for prejudice against many different groups (Mdual = 2.18, SD = 1.71) than when participants only saw the first poster expressing concern for their disfavored group (Msingular = 1.30, SD = 1.49), t(123) = 3.053, p < 0.001, supporting H2. See Fig. 8.

Study 5: Effect of dual concern versus singular concern on moral concern and persuasion when an anti-prejudice activist group implies criticism of a sociopolitical target group for causing harm to a sociopolitical victim group. Note. Error bars represent standard error of the mean. All items are on a 7-point scale on which 1 = most negative and 7 = most positive. ***p < 0.001

Increased perceived moral concern again mediated the effect of dual concern on agreement with the criticism. Moral concern positively predicted agreement (B = 0.506, SE = 0.093, p < 0.001) and mediation analysis (dual concern = 1, singular concern = 0) revealed a significant indirect effect of perceived moral concern on agreement with criticism (95% CI = [0.2621, 0.9691]), supporting H3.

Discussion

Even in the context of implied criticism in an anti-prejudice campaign, messages that expressed dual concern, versus singular concern, increased perceptions of moral concern toward the target group, which in turn predicted agreement with the criticism among members of the target group.

General Discussion

In pursuit of social change, messengers often use their voice to criticize target groups for the harm that they cause to prompt reconsideration of their behavior. Dual concern messages may offer a more positive, truthful, and effective way to levy such criticism. In a world in which the denial and dismissal of unpalatable facts often seems to be the norm, dual concern constitutes a promising strategy for communicating critical messages.

Criticizing groups puts messengers in a perilous position. As our research shows, criticism often causes those in the target group to infer that the messenger has little moral concern for their group, leading those in the target group to be resistant to the criticism. The criticism also results in backlash toward the messenger, with members of the target group no longer willing to patronize a business whose CEO has been critical of their group. This can produce a double failure: an inability to persuade target groups to acknowledge the error of their ways, and in the act of criticizing, a loss of support.

To offer a solution for this dilemma, we introduced the concept of dual concern messages as a constructive new form of criticism. Dual concern messages criticize a target group for causing harm while also expressing concern for the same criticized target group. Across business and sociopolitical contexts, we found that dual concern messages that make salient messengers’ concern for the target groups they criticize have many benefits. Specifically, we observed that members of a target group are more likely to accept criticism of their group if the critical messenger also expresses concern for the target group. This effect also applies to corporate contexts. The otherwise detrimental effect of corporate criticism on purchase intentions is mitigated when the criticism is expressed via a dual concern message. Further, we found that dual concern messages are effective because they foster the perception that critical messengers have more moral concern for the target groups they criticize.

At first glance, it may seem disheartening that there is a widespread—and, as the pilot studies illustrate, often mistaken—inference that a person who criticizes a target group does not care about this group’s welfare. Unfortunately, too, this inference damages persuasion and business-consumer relations. However, our findings offer some optimism. As the pilot studies demonstrate, critical messengers often have more concern for those whom they criticize than the targets of criticism assume. These critical messengers can easily rectify misconceptions by explicitly stating dual concern and, in doing so, can improve the persuasive effectiveness of their criticism among the target group and reduce any backlash that is otherwise prompted. These findings resonate with other recent research that suggests that faulty meta-perceptions of what one group believes about another may drive divisions in society, and that reducing these mistaken beliefs can promote positive reactions and open minds to change (Ruggeri et al., 2021).

Implications

This research provides evidence that dual concern messages allow a messenger to offer criticism while communicating that they care about a criticized target group. Such messages encourage contemplation of criticism to a greater extent than do straightforward accusations and prevent backlash against the critical messenger. As such, dual concern constitutes a promising strategy for issuing criticism without prompting defensiveness and rejection of criticism, adding to theories of group-directed criticism (Hornsey, 2005; Hornsey et al., 2008; Rösler et al. 2021). Notably, dual concern messages represent a strategy that increases acceptance of criticism even when the messenger is an outgroup member (e.g., a political Independent criticizing Conservatives or Liberals). Research on group-directed criticism highlights the difficulty of overcoming defensive reactions to criticism, especially when outsiders criticize groups (Hornsey et al., 2004). We contribute by documenting a strategy that can reduce negative inferences about motives for criticizing a group and thus increase persuasiveness, regardless of the messenger’s outgroup status. Further, while research shows enhanced defensiveness when criticism implies immorality (Rösler et al., 2021), our research offers a strategy for addressing morally-laden issues (e.g., causing harm) without prompting negative inferences about a messenger.

Our research also illustrates that dual concern messages may forestall backlash against companies that take explicit ideological stances, thereby preventing consumers from feeling alienated and taking their business elsewhere. This adds an important new perspective to existing studies which examine the positive and negative consequences of corporate activism (Bhagwat et al., 2020; Eilert & Nappier Cherup, 2020; Hambrick & Wowak, 2021). Our findings show the importance of affirming moral concern for criticized groups in corporate communications and highlight the practical significance of employing dual concern when companies take a stance on sociopolitical and other ethical issues.

Our studies show that dual concern can be communicated in two forms. Dyadic dual concern, which was explored in Studies 2 and 3, involves implicating the victim group in harm. For instance, while criticizing Democrats for being unfairly prejudiced toward Republicans, a messenger also stated that Republicans are unfairly prejudiced toward Democrats. The second form of dual concern, referred to as “exo-dyadic,” is expressed through concern about harm caused to the target group by a third party that is clearly outside of the target-victim dyad. Stating that California is harmed by the U.S. federal government while criticizing California of harming Mexico (Study 4) is an example of this form of dual concern. Given that dual concern can be expressed exo-dyadically, it is not synonymous with blame sharing or two-sided argumentation. Exo-dyadic dual concern avoids explicitly or implicitly suggesting that a victim group is causing harm to a target group, thus avoiding victim blaming.

It is important to clarify that dual concern is not equivalent to statements in public discourse such as “All Lives Matter” (Victor, 2016), a rebuttal to statements like “Black Lives Matter.” The statement “Black Lives Matter” intends to highlight specific harm and injustice Black people face. Dual concern explicitly acknowledges the specific experienced harm of many groups.

Limitations and Future Directions

This series of studies focused primarily on members of the criticized target groups as the audience for dual concern messages. Future work should consider the effects of dual concern messages on other audiences. For some audiences, dual concern messages may prove less effective. For example, certain victim groups and their supporters may consider dual concern messages as morally problematic because these messages risk diverting the focus of moral concern away from victim groups. Dual concern messages could, thus, compromise a messenger’s standing with these audiences. Further, the chorus of people who already agree with a criticism may be more effectively motivated to act through singular concern criticism. To control for a messenger’s group status, the current studies mainly examined the effectiveness of dual concern messages issued by relatively neutral parties such as Independents criticizing Conservatives or Liberals. The effectiveness of dual concern messages might vary depending on the attributes of the speaker, for instance, whether they are part of the in-group or out-group (Esposo et al., 2013), and future research could investigate this possibility.

Conclusion

As a communication and persuasion strategy, dual concern may have applications to a wide range of ethical issues in business. From CEO and corporate activism to cause marketing and to non-profits, the need to communicate the importance of an issue and criticize those in the wrong is becoming exceptionally common. However, criticism often increases defensiveness among the very audience that needs to be receptive to a message calling for change. Our research demonstrates that calls for organizational and social change may unintentionally give the impression that messengers have no concern for the groups they criticize, leading these messages to backfire and inadvertently alienate the targets of criticism. But messages that are crafted in ways that avoid prompting this defensiveness—by showing that critical messengers nonetheless have moral concern for the people whom they implore to change—ultimately result in more openness to change. To prompt the changes that they want to see in the world, critical messengers need to learn to criticize with care.

Data availability

Data are available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Notes

For instance, the third opening example about focus groups expresses dyadic dual concern: “But companies are also unfair to participants in focus groups.” An exo-dyadic example in this same context might read instead: “But participants in focus groups also face challenges from the government, which makes paying taxes complicated.”

For robustness, this study included another non-comparative two-item measure of moral concern that asked participants to make inferences about the messenger’s absolute care for the target group, rather than the messenger’s concern for the target relative to the victim group. This measure was also included in Study 3, correlated highly with the measure presented in the text, and yields similar patterns and significance (see supplemental material).

We focused on Democrats and Republicans to have two clearly defined target groups that would be criticized by the messenger. However, including the 13 self-identified Independents whom we omitted from the analyses does not alter the patterns or significance of the results.

An additional eighteen participants who identified as “ethnically Mexican” at the end of the study were excluded from the main analyses as this population may perceive themselves, at least tangentially, as part of the victim group (i.e., Mexico and its people). When these participants were included in the analyses, the effects on agreement and moral concerns were slightly weakened, as may be expected, but the effects remained significant (ps < .02).

References

Ben & Jerry’s (2020). We must dismantle white supremacy: Silence is not an option. https://www.benjerry.com/about-us/media-center/dismantle-white-supremacy. Accessed 7 Mar 2022

Bhagwat, Y., Warren, N. L., Beck, J. T., & Watson, G. F. (2020). Corporate sociopolitical activism and firm value. Journal of Marketing, 84(5), 1–21.

Biggs, M., & Andrews, K. T. (2015). Protest campaigns and movement success: Desegregating the U.S. South in the early 1960s. American Sociological Review, 80(2), 416–443.

Branicki, L., Brammer, S., Pullen, A., & Rhodes, C. (2021). The morality of “new” CEO activism. Journal of Business Ethics, 170(2), 269–285.

Brenkert, G. G. (2019). Mind the gap! The challenges and limits of (global) business ethics. Journal of Business Ethics, 155(4), 917–930.

Chatterji, A., & Toffel, M. W. (2019). Assessing the impact of CEO activism. Organization & Environment, 32(2), 159–185.

Cialdini, R. B., Vincent, J. E., Lewis, S. K., Catalan, J., Wheeler, D., & Darby, B. L. (1975). Reciprocal concessions procedure for inducing compliance: The door-in-the-face technique. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 31(2), 206–215.

Cook, T. (2015). Pro-discrimination ‘Religious Freedom’ Laws Are Dangerous. The Washington Post. The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/pro-discrimination-religious-freedom-laws-are-dangerous-to-america/2015/03/29/bdb4ce9e-d66d-11e4-ba28-f2a685dc7f89_story.html. Accessed 7 Mar 2022

Cutright, K. M., Wu, E. C., Banfield, J. C., Kay, A. C., & Fitzsimons, G. J. (2011). When your world must be defended: Choosing products to justify the system. Journal of Consumer Research, 38(1), 62–77.

Dworkin, T., & Baucus, M. S. (1998). Internal vs. external whistleblowers: A comparison of whistleblowing processes. Journal of Business Ethics, 17(12), 1281–1298.

Eilert, M., & Nappier Cherup, A. J. (2020). The activist company: Examining a company’s pursuit of societal change through corporate activism using an institutional theoretical lens. Journal of Public Policy and Marketing, 39(4), 461–476.

Eisend, M. (2006). Two-sided advertising: A meta-analysis. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 23(2), 187–198.

Esposo, S. R., Hornsey, M. J., & Spoor, J. R. (2013). Shooting the messenger: Outsiders critical of your group are rejected regardless of argument quality. British Journal of Social Psychology, 52(2), 386–395.

Federico, C. M., & Ekstrom, P. D. (2018). The political self: How identity aligns preferences with epistemic needs. Psychological Science, 29(6), 901–913.

Gelles, D., & Sorkin, A. R. (2021). Hundreds of companies unite to oppose voting limits, but others abstain. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2021/04/14/business/ceos-corporate-america-voting-rights.html. Accessed 7 Mar 2022

Goodwin, G. P. (2015). Moral character in person perception. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 24(1), 38–44.

Gray, K., Schein, C., & Ward, A. F. (2014). The myth of harmless wrongs in moral cognition: Automatic dyadic completion from sin to suffering. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 143(4), 1600–1615.

Groza, M. D., Pronschinske, M. R., & Walker, M. (2011). Perceived organizational motives and consumer responses to proactive and reactive CSR. Journal of Business Ethics, 102(4), 639–652.

Hambrick, D. C., & Wowak, A. J. (2021). CEO sociopolitical activism: A stakeholder alignment model. Academy of Management Review, 46(1), 33–59.

Hayes, A. F. (2012). PROCESS: A versatile computational tool for observed variable mediation, moderation, and conditional process modeling [White paper]. Retrieved from http://www.afhayes.com/public/process2012.pdf.

Hoppner, J. J., & Vadakkepatt, G. G. (2019). Examining moral authority in the marketplace: A conceptualization and framework. Journal of Business Research, 95, 417–427.

Hornsey, M. J. (2005). Why being right is not enough: Predicting defensiveness in the face of group criticism. European Review of Social Psychology, 16(1), 301–334.

Hornsey, M. J., Grice, T., Jetten, J., Paulsen, N., & Callan, V. (2007). Group-directed criticisms and recommendations for change: Why newcomers arouse more resistance than old-timers. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 33(7), 1036–1048.

Hornsey, M. J., & Imani, A. (2004). Criticizing groups from the inside and the outside: An identity perspective on the intergroup sensitivity effect. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 30, 365–383.

Hornsey, M. J., Oppes, T., & Svensson, A. (2002). ‘It’s OK if we say it, but you can’t’: Responses to intergroup and intragroup criticism. European Journal of Social Psychology, 32, 293–307.

Hornsey, M. J., Robson, E., Smith, J. R., Esposo, S., & Sutton, R. M. (2008). Sugaring the pill: Assessing rhetorical strategies designed to minimise defensive reactions to group criticism. Human Communication Research, 34, 70–98.

Hornsey, M. J., Trembath, M., & Gunthorpe, S. (2004). ‘You can criticize because you care’: Identity attachment, constructiveness, and the intergroup sensitivity effect. European Journal of Social Psychology, 34, 499–518.