Abstract

The literature on meaningful work often highlights the role of leaders in creating a sense of meaning in the work or tasks that their staff or followers carry out. However, a fundamental question arises about whether or not leaders are morally responsible for providing meaningful work when perceptions of what is meaningful may differ between leaders and followers. Drawing on Buddhist ethics and interviews with thirty-eight leaders in Vietnam who practise ‘engaged Buddhism’ in their leadership, we explore how leaders understand their roles in creating meaningfulness at work and their perceptions of how employees experience their leadership approach in this respect. On the basis of Buddhist ontology on the sense of meaningfulness, we introduce a number of leadership approaches in cultivating meaning at work that question the argument that leaders are primarily responsible for enabling or satisfying employees’ search for meaning. The study provides an alternative lens through which to examine the role of leadership from a Buddhist ethics perspective and shows how an insight from this particular tradition can enrich secular interpretations of meaningful work and leadership.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The experience of meaning in life is universally viewed as a cornerstone of human well-being and a fundamental contributor to motivation (Heintzelman & King, 2014). Meaningful work has recently been receiving increased attention across a variety of disciplines such as management, psychology, theology, philosophy, sociology, and ethics (Bailey et al., 2019; Frémeaux & Pavageau, 2022; Lepisto & Pratt, 2017; Lysova et al., 2019; Rosso et al., 2010). The most common focus of the study is employees’ experience of work meaningfulness (e.g., Aguinis & Glavas, 2013; Aguinis & Glavas, 2019; Michaelson et al., 2014; Pratt et al., 2013; Rosso et al, 2010), particularly how organizations can engage and retain employees by providing work that is experienced or perceived as meaningful to them (Bailey et al., 2019; Lysova et al., 2019).

Business ethics scholars consider meaningful work in the context of leading and managing people in the workplace as a moral issue (Michaelson et al., 2014). Leaders have increasingly been regarded as having a responsibility to provide a supportive working environment for employees. For instance, leaders can treat employees with honesty, fairness, and respect by providing or encouraging democratic involvement to support their desire for meaning in their work and its pursuit and discovery (Frankl, 1984; Michaelson, 2005). Leaders can also enhance a sense of belonging and worth (Gill, 2022a) by creating or making a clear connection between employees’ daily tasks and the vision and purpose, or mission of their group or organization (Allan, 2017). Leaders are expected to set, and live up to, objectively defined ethical standards in the organization (Wang & Xu, 2019) to create an ethical climate whereby employees can experience meaningfulness through the alignment between personal and organizational values (Kahn & Fellows, 2013).

However, in their study, Bailey & Madden (2016) found limited fulfillment of this ethical responsibility. It is therefore useful to explore how leaders support employees in their search for meaning (Lips-Wiersma et al., 2020). We argue that placing the responsibility for cultivating employees’ sense of meaningfulness on leaders alone is problematic. Much of the literature assumes that people share a sense of meaningfulness, but not much has been said about how and why meaningfulness may differ across different individuals (Rosso et al., 2010; Weeks & Schaffert, 2019), particularly between leaders’ and followers’ perceptions of what is meaningful work (Demirtas et al., 2017). Michaelson et al. (2014) called for a greater integration of the literature on business ethics and meaningful work because moral responsibility in organizational management largely lies with leaders, who are able to help create a sense of meaning for their followers in their daily work (Chalofsky, 2003; Michaelson, 2005; Pratt & Ashforth, 2003).

In this paper, we explore the viewpoints of Buddhist-enacted leaders from their lived experiences of applying Buddhist philosophy to cultivate meaningful work. In doing so, we also explore how leaders understand their roles in creating meaningfulness at work and their perceptions of how employees experience their leadership approaches. Given that the notion of meaningfulness is contextually and culturally bounded (Boova et al., 2019; Geertz, 1973; Mead, 1934), we examine the perspectives of, and approaches to, meaningful work of leaders who practise “engaged Buddhism” in their leadership behavior in Vietnam, a communist nation that is in economic and social transition (The Economist, 2020). Engaged Buddhism emerged in Asia in the twentieth century to describe how Buddhists responded to the challenges of colonialism, modernity and secularism, often ascribed to the Vietnamese Buddhist monastic Thich Nhat Hanh in his anti-war activism (Gleig, 2021).

We argue that it is important to explore the notions of meaning-making and meaningful work from alternative perspectives of different traditions (Ivanhoe, 2017; Lloyd, 1996; Wong, 2020) as a comparative philosophical approach can further extend understanding and transcend the limits of a given philosophical and social paradigm. Yu & Bunnin (2001) posit that each tradition has something insightful to offer about some aspect of the problem. More specifically, in most Western studies of meaningful work, tensions tend to arise as a result of the paradox of self-fulfillment versus dependence on the ‘other’ (Bailey et al., 2019), which entails how attachment to the self and self-fulfillment can limit experiences of meaningfulness. Buddhist philosophy on the other hand provides a more naturalistic analytic philosophy that highlights how the self is not a bounded and discrete entity (Flanagan, 2013; Sidertis, 2003) that encourages a more impersonal view of the self and desire for meaningfulness (Wong, 2020). This can offer an alternative lens to hyper-individualist notions and misconceptions of the self and promote instead the notion of ‘Oneness’ (Ivanhoe, 2017) in cultivating meaningfulness at work in which responsibility for meaning-making is situated in a more interconnected and interdependent social ontology.

There are a number of reasons why we chose to study this specific context. First, engaged Buddhism has emerged as a significant phenomenon: spiritual yearning influences the way people perceive work and behave at work (Vu & Gill, 2018; Vu, 2021a). Other studies suggest that the societal and cultural context can affect the way individuals see the inherent worthiness of work (Lepisto & Pratt, 2017; Mitra & Buzzanell, 2017). Second, examining meaningful work within a Buddhist-enacted context contributes to the conceptualization of meaningful work in the context of workplace spirituality. Although there is a growing interest in approaching meaningful work from a spiritual perspective (e.g., Ahmad & Omar, 2016; Chen & Li, 2013; Gill, 2022b; Vu & Burton, 2021), empirical evidence remains relatively limited (for a review see Bailey et al, 2019). Spiritual traditions provide normative commitments: Buddhist ethics is a philosophy with an ethical and moral way of living that can shape distinctive meaning-making in organizations (Vu & Burton, 2021). Third, a spiritual ethical guide (e.g., Buddhist ethics) can be a driver in how leaders experience, make sense of, and influence meaningfulness at work (Lips-Wiersma & Morris, 2009).

Our findings show that Buddhist leaders have distinctive interpretations of, and approaches to, meaningful work due to the multiple socio-political-cultural contextual constraints. The Buddhist worldview emphasizes the need to interpret and see phenomena (e.g., meaningful work) and practices (Buddhist-enacted leadership styles) in terms of their transient and impermanent nature. This reflects a practical and contextual approach of Buddhism and how its applicability is influenced by its rhetorical, pedagogical, and soteriological context (Schroeder, 2000, 2011) to shape how Buddhist principles and teachings influence the way individuals interpret phenomena differently. Our findings suggest that making sense of meaningful work and its cultivation in the context of workplace spirituality are subject to the nature of the context, spiritual, and cultural worldviews, and subjective value systems (Boova et al, 2019; Mitra & Buzzanell, 2017; Vu & Burton, 2021). This highlights why the Buddhist perspective ontologically positions a sense of meaningfulness in impermanence (similar to the ontology of becoming).

The study also contributes to the limited research on leaders’ views about and practices of meaningful work, supplementing a recent study by Frémeaux & Pavageau (2022) which identified new aspects of meaning in relation to leadership. The study provides an alternative Buddhist view that questions post-modern forms of organizational control of meaningful work. Drawing on Buddhist ethics that does not privilege agency as the core moral value within the nexus of an interdependent community (Garfield, 2021), we contribute to a deeper understanding of why cultivating meaningful work is not solely a matter of individual agency, nor the sole responsibility of leaders. In doing so, we answer the fundamental question of whether leaders are morally responsible for meaningful work in organizations (Michaelson, 2021), thereby enriching secular interpretations (Wong, 2020) of meaningful work and leadership (Frémeaux & Pavageau, 2022).

We first provide a literature review of meaningful work in relation to leadership in general and in the field of business ethics and the relationship between meaningfulness and meaning-making in Buddhism. Next, we present our research methodology and findings, with a discussion of the main contributions of the study and suggestions for future studies.

Meaningful Work and Leadership Responsibility

The conceptualization of meaningful work has both objective and subjective dimensions. Objective characteristics of meaningful work refer to a type of activity (Bailey & Madden, 2016), such as providing opportunities for intrinsic motivation (Chalofsky & Krishna, 2009; Michaelson, 2005). Subjective characteristics concern the value of work judged in relation to individuals’ personal standards (May et al., 2004; Michaelson, 2021). Because of the complex and dynamic dimensions of meaningful work, the term ‘meaningful work’ has been used interchangeably in the literature with ‘meaningfulness’ and ‘meaning of work’ and defined in various ways (Allan, 2017): there is no concrete consensus so far on how to define meaningful work (Bailey et al., 2019).

Scholars of ethics, philosophy, and political science (e.g., Beadle & Knight, 2012; Bowie, 1998; Michaelson, 2008; Sayer, 2005; Wolf, 2010; Yeoman, 2014) have referred to meaningful work as a moral concern (Lips-Wiersma et al., 2020; Lips-Wiersma & Morris, 2009; Michaelson et al., 2014; Trevino et al., 2006; Yeoman, 2014). Studies show that employees’ experience of meaningful work is associated with a moral organizational climate and an organizational self-transcendent orientation (Schnell et al., 2013). Organizational purpose and objective ethical features such as autonomy and equitable compensation (Bowie, 1998) that are recognized by individuals can enable them to experience meaningful work (Ciulla, 2012). There is, therefore, an ethical imperative for organizations and leaders to create the conditions for meaningful work (Lips-Wiersma et al., 2020; Yeoman, 2014) whereby leaders imbue work with meaningfulness by articulating an inspiring vision and shared values (Michaelson et al., 2014).

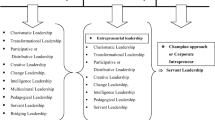

There are a number of leadership styles that can enhance employees’ sense of meaningful work through engagement and organizational identification (e.g., Chen et al., 2018; Demirtas et al., 2017; Lysova et al., 2019). There is a consensus among researchers that the dynamics of meaning are not the exclusive responsibility of leaders but are linked to leadership (Lysova et al., 2019; Michaelson, 2005) and how leaders foster person-organizational fit (Chalofsky, 2003; Steger & Dik, 2010) to align personal values with the organizational mission in daily tasks (Allan, 2017). For instance, both transformational leadership (Tummers & Knies, 2013) and ethical leadership (Demirtas et al., 2017) are positively linked to meaningful work. Ethical/moral values-based leadership such as spiritual leadership (Avolio & Gardner, 2005), authentic leadership (Avolio et al., 2004; Cassar & Buttigieg, 2013; Gill, 2022a), and servant leadership (Jiang et al., 2015) all influence followers’ meaning-making.

Leadership behavior can help to construct meaning in work for followers (Sosik, 2000) through a leader’s own sense of meaningfulness (Steger & Dik, 2010), providing supportive, honest, and fair working conditions (Michaelson, 2005), and providing followers with a sense of significance (Martela, 2010; Rosso et al., 2010). They do this by helping them to understand how their daily tasks connect to higher purposes (Allan, 2017). These features of leadership behavior led Frémeaux & Pavageau (2022) to identify and conceptualize several components of meaning related to leadership activity known as “meaningful leadership”: moral exemplarity, self-awareness, personal and professional support, community spirit, shared work commitment, and a positive attitude toward others and events.

However, in a study by Bailey & Madden (2016), there was little evidence of organizational leaders actually creating work meaningfulness; indeed, managers contributed to a decrease in it. And while transformational leadership can inspire employees through a vision for a meaningful future (Bass, 1990) and ideal job characteristics, such a vision may often be too vague for employees to understand or may not reflect what employees are actually seeking. Objective and subjective features of meaningful work arise from ‘a sense of coherence between the expected and perceived job characteristics according to one’s own ideals or standards’ (Frémeaux & Pavageau, 2022, p.55). Even if leaders engage in altruistic and reflective approaches (e.g., spiritual leadership) they run the risk of being confronted with the dominant values of the socio-economic system and a lack of flexibility of their organizations (Frémeaux & Pavageau, 2022).

Studies have found that organizations’ intentions to enhance employees’ sense of meaningful work by creating an environment characterized by ethical leadership can fail when facing employees with poor dispositional characteristics (Wang & Xu, 2019). Bailey & Madden (2016) argued that leaders need to pay attention to what to do to avoid damaging meaningfulness as experienced by employees. This, they say, may include providing autonomy for employees to encourage their creativity, acknowledging employees’ contributions (Montani et al, 2017), avoiding overburdening them with work (Duffy et al, 2016), and promoting authenticity in cultivating meaningful work (Lysova et al., 2019). Yet leadership approaches to meaningful work also entail tensions because their approaches may be considered to be instrumental rather than altruistic (Bailey & Madden, 2016; Bailey et al., 2017; Gabriel, 1999). While studies focus on what leaders can or should do to cultivate meaningfulness at work, little is known about what meaningfulness actually means for leaders themselves and how their interpretations of their own and others’ meaning-making guide their approaches to it.

Meaningful Work and Workplace Spirituality

Meaningful work and spirituality are closely related (Gill, 2014, 2022b). Meaningful work is understood to exist ‘when an individual perceives an authentic connection between their work and a broader transcendent life purpose beyond the self’ (Bailey & Madden, 2016, p. 55) in which spirituality is a significant source of influence (Rosso et al, 2010). Empirical studies show that spirituality promotes meaningfulness at work that leads to engagement with work (Saks, 2011). Indeed ‘spiritual’ employees tend to relate their work to things that are greater than themselves—a higher purpose and meaning (Lips-Wiersma, 2002). Likewise, studies also suggest that spiritual leaders enhance a climate of meaningfulness (Yang & Fry, 2018) and provide employees with a sense of the intrinsic value and meaning of work (Reave, 2005). Dess & Picken (2000) suggest that leadership is not just about making money, but more about making meaning: people at work seek greater meaning, value, and a sense of belonging and worth in what they do.

The literature also highlights that leaders and organizations may display “empty speech” in their promises to leave the ego behind through a putative connection to purposes greater than the self (Dehler & Welsh, 1994; Driver, 2005). For example, leaders may attach their ‘selves’ to a larger identity, such as their organization’s purpose or mission or its goals (Driver, 2005; Tourish & Tourish, 2010), in the name of securing beneficial interests for all. This aims to make profit-driven goals more acceptable to employees, a tactic known as a ‘Machiavellian calculation’ (Tourish & Tourish, 2010).

Workplace spirituality may also reflect a normatively regulated working environment (Bailey et al., 2019) that significantly affects the ways in which individuals experience meaningful work. In this sense, the language of spirituality can be an attempt to manipulate or seduce employees into placing the needs of the organization above their own (Krishnakumar et al., 2015; Lips-Wiersma et al., 2009). And once employees choose or become attached to spirituality as a form of rationality, they may become vulnerable to manipulation. We situate our study in the context of workplace spirituality where we explore how Buddhist-enacted leaders use Buddhist practices to justify their interpretations of leadership responsibility for meaningful work.

Meaningful Work and Buddhist Ethics

In this section, we deconstruct Buddhist interpretations and sense-making of meaningfulness and how they may influence leaders’ perspectives of, and approaches to, meaningful work.

Buddhism and Buddhist Ethics

Buddhist philosophy reflects a way of living and reasoning which encourages a practical attitude toward dealing with the issues of life (Esposito et al., 2006; Mendis, 1994). Buddhism highlights a way to understand the nature of suffering and its function by taking refuge in the Three Jewels (Sanskrit: triratna): the Buddha, the Dharma—Buddhist teachings and behavioral codes—and the Sangha—the community that follows the Buddha’s footsteps and practices of the Dharma (Sangharakshita, 1968). Buddhist practices are guided by the Four Noble Truths (Sanskrit: catvāri āryasatyāni; Pali: cattāri ariyasaccāni)—the fundamental Buddhist truths that encourage ethical conduct by balancing material and spiritual well-being and the need to moderate desires such as greed which, in excess, are sources of suffering (Mendis, 1994).

These truths (Flanagan, 2011; Mendis, 1994; Siderits, 2007) highlight how (1) life consists of suffering; (2) suffering is a result of desires and cravings; (3) suffering can be eliminated by overcoming ignorance; and (4) following the Noble Eightfold Path (Pali: ariyo aṭṭhaṅgiko maggo; Sanskrit: āryāṣṭāṅgamārga) liberates suffering. Through the Noble Eightfold Path, an individual can develop ethical conduct (via the principles of right speech, right action, and right livelihood), mental discipline (via the principles of right effort, right mindfulness, and right concentration), and wisdom (via the principles of right views and right thoughts) (Anderson, 2001; Case & Brohm, 2012; Rahula, 1978). Such a developmental journey is based upon the Buddhist worldview, which relies on understanding the truth or reality through direct experiences with the nature of reality (the world) and epistemological beliefs (e.g., how we know what we know) (Hart, 1987). Realities or truths in the Buddhist worldview are conceptualized through the acknowledgment of the notions of impermanence,Footnote 1 emptiness,Footnote 2 non-self,Footnote 3 dependent arising,Footnote 4, and karma,Footnote 5 to mention a few.

However, to be able to fully experience reality in a discerning way, Buddhist philosophy places great importance on the notion of non-attachment—the ability to release mental fixations that are incompatible with dependent arising and the impermanent nature of reality (Sahdra et al., 2010). Interestingly, non-attachment calls for Buddhists not to be attached to Buddhist teachings (the Dharma) and practices without careful consideration of context, instead to contextualize Buddhist practices flexibly with a variety of delivery forms known as skillful meansFootnote 6 (Kern, 1989; Lindtner, 1986). Skillful means concern the way knowledge is taught and applied flexibly in practice, based on non-attachment and compassion (Vu & Gill, 2019a, 2019b). Skillful means resist the tendency to confine the practices to an absolute soteriological path (Schroeder, 2011). This highlights how Buddhism is embedded in a contextual approach which is more pragmatic and functional than propositional and is without fixed evaluative criteria (Schroeder, 2004, 2011). Even when one takes refuge in the Dharma, it is important to highlight that Buddhist practice (the Dharma) is empty of any substance of independent validity and its applicability is determined by its rhetorical, pedagogical, and soteriological context (Schroeder, 2004).

Buddhist ethics based on this Buddhist worldview reflect the need to solve or ameliorate the problem of suffering in relation to dependent arising as a path and not a set of prescriptions (Garfield, 2021). Garfield (2021) argues that Buddhist ethics ‘presents a distinct moral framework addressed to existential problem-solving. In this framework, action is not taken to be produced by a free will bound by laws. Instead, action is seen as arising from a dependently originated, conditioned continuum of causally interdependent psychophysical processes.’ (p.20).

In the west, the concept of virtue ethics originated with Aristotle. Keown (1992) argued that Aristotelian virtue ethics provide a useful model for understanding Buddhist ethics and the Buddhist moral system. It is also regarded as a useful model in contemporary leadership and management theory and practice. Both the Buddha and Aristotle valued ethical reasoning and embodied positive values, which Aristotle called virtues. For instance, in Buddhism, in the process of attaining wisdom, there is a teleological summum bonumFootnote 7 (eudaimoniaFootnote 8 in Aristotle, nirvanaFootnote 9 in Buddhism) that is achieved through the cultivation of virtues and actions that are right to the extent that they are manifest in “nirvanic values” such as “Liberality (arāga), Benevolence (adosa), and Understanding (amoha).

However, Keown (1992) argues that, unlike Aristotle’s virtue ethics, summum bonum is situated within the right and the good; in Buddhism they are inseparably intertwined. In Buddhist ethics, it is the motivation which precedes an act that determines its rightness or goodness. Aristotle viewed virtue as a state that involves choice and a disposition to act in certain ways that concerns the agent’s character, feelings, and emotions (Hanner, 2021). Fink (2013), while generally accepting Keown’s comparison between Aristotelian virtue ethics and Buddhist ethics, argues that Buddhist ethics are similar to act-centered virtue ethics. Garfield (2015) claims that it is important not to assimilate Buddhist ethics to any system of Western metaethics because it is neither utilitarian nor deontological and not aretaic—focused on virtue or excellence—in form. Buddhist metaphysics that embraces the commitment to the notion of dependent arising of all phenomena reaffirms how moral reflection on action must take into consideration all dimensions of dependence into account, not just focusing on agency, motivation, the action itself, or the consequences for others (Garfield, 2015). This highlights the contextual approach (Schroeder, 2011) in Buddhist ethics and how agency is no longer the core moral value in the Buddhist worldview (Garfield, 2021). Indeed, Hanner (2021) argues, Buddhist ethics should be seen as a pluralistic system of different modalities of living well and associated practices rather than a universalistic theory.

Based on Buddhist philosophy and ethics, we deconstruct meaningfulness (1) as a state of being that can closely relate to suffering if there is over-attachment to it, and (2) as a transient state based on the notion of impermanence of all phenomena.

Meaningfulness, Attachment, and Suffering

Most of the extant literature on meaningful work focuses on the ‘self,’ such as meaningful work relating to self-worth (Rosso et al., 2010), self-determination (Deci & Ryan, 2000), self-realization (Waterman, 1993), and individualistic concerns about job meaningfulness (Bailey & Madden, 2016). The notion of self is also emphasized in leadership, in particular spiritual leadership, but through the need to motivate oneself to enhance a sense of spiritual well-being, making a difference in some way, and through the need to be understood and appreciated (Fry et al., 2005).

However, in Buddhism, according to the Four Noble Truths (Sanskrit: catvāri āryasatyāni; Pali: cattāri ariyasaccāni), excessive desires may induce individuals to become fixated on the need to achieve things at any cost, thereby leading to psychological or emotional burden and suffering. Some of this suffering is caused by individuals’ illusions of an ultimate state of self and reality (Gampopa, 1998) and a failure to acknowledge the impermanent nature of all phenomena, including an illusion of a definite self. Therefore, excessive desires, even for meaningful things, can lead individuals into paradoxes of meaningful work because the state and the sense of meaningfulness are not static but impermanent. For instance, individuals with a greater sense of calling at work can experience heightened expectations about management’s moral duty related to work, which may be a ‘double-edged sword’ (Bunderson & Thompson, 2009, p.52) in pursuing meaningfulness. In doing so, individuals may strategize and craft a counterfactual self or an imagined self to fit in with others’ expectations in the pursuit of acceptance or recognition (Obodaru, 2012), or they may develop a symbolic manipulation of meanings (Gabriel, 1999) to generate a felt need as if work were meaningful (Bailey et al., 2017; Cartwright & Holmes, 2006). This may result in a struggle to reach a balance between being (e.g., belonging) and doing (e.g., making a contribution) (Lips-Wiersma & Morris, 2009; Lips-Wiersma & Wright, 2012), reflecting ignorance or misunderstanding and consequent suffering in forming an excessive attachment to the pursuit of meaningfulness at work.

In fact, many studies of leadership focus on the constructs of having (personal characteristics) and doing (actions or behavior), which are central to an ego-based concept of self rather than to an understanding of ‘being’ and non-self (the rejection of ego-centrality) (Fry & Kriger, 2009; Kriger & Seng, 2005). While leaders may be motivated to construct meaningful work, the desire to attain a sense of meaningfulness for all, and at all cost at work, supported and reflected by excessive and obstinate pursuits, can lead to suffering. The ‘self’ or ‘mode of being’ that leaders may be intrigued to promote in their approaches to meaning-making is embedded in society rather than in an autonomous and unitary entity or being. This is apparent or co-constituted in interactions with others that may affect and even question leaders’ sense of self and self-worth (Kenny & West, 2008). The practice of Buddhism, therefore, encourages a state of non-self in the sense that misinterpretations of a permanently independent self can lead to an adversely ego-centric or self-centered mindset (Hwang & Chang, 2009; Wallace & Shapiro, 2006).

Meaningfulness and Transiency

Constructing meaningful work is influenced by others: in an ongoing, natural search for meaningful work, it is rendered with, through, and by others (Lips-Wiersma & Morris, 2009). Meaningful work is often renegotiated over time when changes happen (Mitra & Buzzanell, 2017), reflecting the temporal nature of meaningfulness (Bailey & Madden, 2016). Likewise, the self is reflexively co-constituted with interactions with others (Mead, 1934), reflecting the non-static and temporary state of ‘self.’ The ‘self,’ therefore, embedded in meaningful work, is beyond an individual per se because it is constituted relationally (Simpson, 2015)—in a reflexive relationship with others and through the constitution of multiple contextual factors in a changing environment, as in the process of ‘othering’ (O’Mahoney, 2012)—treating or regarding a person or a group of people as alien to oneself or one's group because of different racial, sexual, or cultural characteristics.

While studies have focused on what leaders should do (e.g., Carton, 2018) and should not do (e.g., Bailey & Madden, 2016; Duffy et al, 2016; Montani et al., 2017) to enhance employees’ sense of meaningful work, such studies have not linked how leadership approaches themselves are temporal and embedded in relationality. In other words, how leadership approaches are subject to contextual temporality has yet to be covered sufficiently in the literature. This can usefully be further examined through the Buddhist notion of impermanence: the state of perpetual change of all phenomena (Pāli: anicca; Sanskrit: anitya).

In Buddhism, impermanence highlights that all phenomena in the universe are constantly changing, even in meaningful moments of time. And anything that resembles the intrinsic existence of the self or phenomena cannot be located in time and space (Tsong-Kha-pa, 2004). Such an interpretation portrays the transient state of meaningfulness. This aligns with studies noting that meaningfulness is an episodic state (e.g., Bailey and Madden, 2016) and is subject to negotiation retrospectively over time (Mitra & Buzzanell, 2017). Therefore, any experience of pleasure, satisfaction or meaningfulness that is believed to be permanent can lead to a self-centered mindset ruled by a hedonic principle (Hwang & Chang, 2009; Wallace & Shapiro, 2006).

According to this principle, such feelings are fleeting and subject to the rise of afflictive affects (Wang et al., 2018). Impermanence facilitates a non-attached attitude, which enables both well-being that is free from unnecessary grasping that in turn may lead to suffering and an understanding that all phenomena, including the self, are empty of intrinsic existence (Van Gordon et al., 2017). Studies also show how non-attachment is a construct of well-being that influences how meaning in life is perceived (Wang et al., 2018). According to the Buddhist concept of emptiness, nothing has a permanent nature as everything is causally related, and this may give rise to various different interpretations of meaningfulness (Cooper, 2002). A Buddhist interpretation of meaningfulness thus can speak much to the yet-to-be explored temporality of leadership approaches to, and interpretations, of meaningful work.

The Study

We studied the leadership approaches of 38 Buddhist practitioners in Vietnam who were senior organizational leaders. The aim of the study was to explore leaders’ interpretations of meaningful work, their perceptions of how employees experience their leadership approaches, and the ethical tensions they faced in handling the need for meaningful work in a range of sectors and industries.

Research Context

The Vietnamese transitional environment under the ‘Đổi Mới’ policy adopted in 1986 has been characterized as having “a dual ideology, a weak legal system, and a cash economy” (Nguyen, 2005, p. 206). Concerns with this culture have led to an upsurge of interest in spirituality and the felt need for the preservation of traditional cultural values in Vietnam (Kleinen, 1999). Buddhist practices have become increasingly evident during this transitional period in response to rapid socio-economic changes, a ‘corrupted’ communist ideology, and problems associated with institutionalized bribery and lack of trust (Vu & Tran, 2021; Vu, 2021b).

The complex transitional context has brought about unrest and feelings of powerlessness in people’s lives (Taylor, 2004; Vu & Tran, 2021), in turn leading to a need for spiritual reinforcement (Soucy, 2012, 2017). As a result, many people in Vietnam have engaged with Buddhist philosophy and practices in their daily life and work, and this has become part of their belief system and philosophical outlook (Vu & Gill, 2018), affecting their sense-making and ethical orientations (Vu et al., 2018) at work. Buddhism together with its philosophy has a long history in Vietnam. Examining meaningful work in this transitional context, we believed, would contribute to a distinctive contextual, spiritual, and cultural worldview and value system in regard to the sense-making and cultivation of meaningful work (Boova et al., 2019; Mitra & Buzzanell, 2017).

Methodology

The study explored the Buddhist-enacted leaders’ lived experiences of, and approaches to, meaningful work. We looked at how leaders’ interpretations of their own and others’ meaning-making at work and their Buddhist practice guide their approaches to cultivating meaningful work. The exploratory nature of this research called for an interpretive, naturalistic qualitative approach (Denzin & Lincoln, 1994). We employed a narrative inquiry approach to allow leaders to share narratives of their interpretations of and approaches to meaningful work and to create opportunities for leaders to make sense of experiences for themselves (Mueller, 2019) and to reflect on them (Humphreys & Brown, 2002). This approach enables a deeper insight into how leaders’ experiences illuminate the potential tensions and struggles they experienced in cultivating meaningful work for followers.

We applied Lincoln & Guba’s (1985) guidelines for purposeful sampling in selecting participants. The reason we chose leaders as interviewees was that they have key interpretational roles in organizations (Bennis & Nanus, 1985; Smircich & Morgan, 1982), so their understanding and cultivating of workplace meaningfulness are essential to our purpose. We used a snowball technique for recruiting thirty-eight leader participants in Vietnam. In Vietnam, people tend not to publicize themselves as Buddhist practitioners because they consider Buddhism to be a personal practice and choice in life. However, Buddhist practitioners generally are willing to share their experiences and practices in Buddhist communities or with people with whom they are familiar. This study was developed from a larger ongoing research project (since 2016) examining the application of various Buddhist principles in the organizational context in which non-attachment to leadership responsibilities and meaningful work emerged as one of the salient phenomena. The original intent of the wider study was to examine and explore the application and adaptation of Buddhist principles and practices in organizations. One of the main purposes of our original study was to investigate how Buddhist practices can be applied, interpreted, and misinterpreted in the contemporary context and how they are practised differently by different individuals in different organizational roles.

The data collection for this study was conducted from 2016 to 2019. In early 2016, the first author spent time seeking permission to participate in different internal workshops run by the three different Buddhist communities to gradually build up trust and contacts with participants. The first author made initial contact with five leaders from three different Buddhist communities based on her networks. We then asked those five participants to recommend other members from their communities who might be willing to take part in the study. Participants in this study are identified by person and company reference (e.g., BxCy) (see Table 1).

Semi-structured interviews were adopted to facilitate in-depth exploration of the leaders’ experiences, assumptions, and practices. This approach was guided by an interview schedule but with a high degree of flexibility to accommodate participants’ varying experiences (Bryman, 2015). Open-ended and follow-up questions that are a feature of semi-structured interviews help to facilitate in-depth exploration of complex phenomena and to “harness respondents’ constructive storytelling” (Gubrium & Holstein, 1997, p. 125). To facilitate participants’ sharing of their experiences of leadership, it was important to provide opportunities within the interviews for them to ascribe meaning to their experiences (Seidman, 2013) and to deconstruct and re-construct experiences in-depth and reflexively (Huber et al., 2013; Humphreys & Brown, 2002). The use of silence was also an important feature, as it allowed participants time to reflect on their thoughts (Van Manen, 1990).

Interviews were conducted face-to-face from 2017 to 2019 in Hanoi and Ho Chi Minh City by the first author. To minimize biasing members’ responses and potential misinterpretations by the interviewer, rather than probing or suggesting ideas, the first author asked follow-up questions only to clarify meaning and contextual stimuli or to elaborate on important or repeatedly mentioned issues. This was particularly important because Buddhist practices entail different approaches and complexities in their application that are distinctive to individuals practising them in different ways.

The interview protocol was designed in two phases (Table 2). The first phase was aimed at gathering demographic information about the respondents, including the number of years of practising Buddhism. In the second phase of the interview, we concentrated on exploring participants’ leadership approaches and actions in cultivating workplace meaningfulness, the tensions in those leadership practices, and their experience in dealing with them.

Analysis

Thematic analysis was adopted for our study. After reviewing the data several times to identify emerging theoretical arguments (Gioia et al., 2013), to develop first-order concepts, we used open coding (Strauss & Corbin, 1990) to determine what the text represented and to explore all possible alternative meanings of it and to give each phenomenon a name. Words and phrases relating to the same phenomenon were extracted and labeled as codes. Once the various codes were identified for each participant, we organized them into themes (Colaizzi, 1978). Statements with different wording but the same meaning received the same code. Codes were grouped into categories and subcategories to develop the initial coding frame and set rules on which data could be included in which category. We relied on vivo codes, notes on specific details and other pieces of information that a number of participants repeated to make sense of the context and important findings.

The participant data were then integrated and compared to identify patterns and the possible interconnections both within and between them. The initial coding frame included different Buddhist principles that influenced the way leaders made sense of meaningful work and their own and other’s perspectives of meaningfulness (e.g., impermanence, compassion, suffering, etc.), the way they felt about what is important for meaning-making (e.g., others, change, being led, etc.), and contextual features of tensions they experienced (e.g., collective, shareholder, network).

To discover second-order themes, we used axial coding to connect concepts that emerged through open coding alongside the process of contrasting and comparing to identify abstract and theoretical categories. We looked for relationships and made connections between a category and its subcategories (Strauss & Corbin, 1990). The codes were then examined and reorganized, categories and subcategories clearly defined, and all transcripts were then recoded using the final codes to establish consistency. We looked at how different Buddhist principles variously influenced the understanding of leaders’ meaning-making at work, arriving at higher, second-order abstract and theoretical categories (e.g., Locke, 2011). For instance, over-attachment to deliver compassion can have counterproductive effects that can lead to suffering (e.g., being taken advantage of, acontextual interpretation of others’ meaning-making, etc.).

Lastly, we further combined themes to identify aggregate dimensions and provide a coherent overall picture of how Buddhist philosophy influenced leaders’ interpretations of, and approaches to, meaning-making at work. To check the relationship between themes, we revisited the emergent first- and second-order themes along with the field notes. Whenever appropriate, we contacted participants to validate interpretations and obtain further explanations relating to the data and to check the coherence of the coding and interpretations of the data. Following the identification of the aggregate dimensions of the data, we turned to the emerging theoretical understanding (Eisenhardt & Graebner, 2007; Gioia et al., 2013) of how Buddhist ethics places agency as a moral value in leaders’ meaning-making at work. We reviewed the data and theory to identify patterns that we began to see and to differentiate between what was witnessed and what was already evident in the literature. Table 3 shows our coding template:

Main Findings

Leaders’ Perspectives of Meaningful Work

Participants in our study interpreted meaningfulness by drawing on their understanding and practice of Buddhist ethics. These interpretations are based on both their own Buddhist practices and fundamental Buddhist ethical principles and philosophy.

Context-Sensitive Compassion Toward Others

Participants highlighted the link between meaningfulness and the ability to show compassion as part of their Buddhist practice:

I find my role as a leader meaningful when I can help my people. […] I have saved a 3-h session each week for employees regardless of their roles to make appointments to have a chat with me and to see how I can offer help to them. I listen to their complaints, suggestions, and sometimes even to their family matters. I offer help whenever I can, which is one way for me to practise compassion, and that brings meaningfulness to my role. Being compassionate and being able to help others is meaningful in itself and it is the core principle of being a Buddhist practitioner. (B9C7)

Participants generally felt that delivering compassion and understanding to employees brings meaningfulness to their leadership roles and that these align with their Buddhist practice. Compassion is the heart of Buddhist philosophy; however, compassion requires a form of meta-practical reflection that takes into consideration different contexts of others without reducing the practice of compassion to a reproducible formula, fixed doctrine, or discourse (Schroeder, 2011). Accordingly, a number of participants also highlighted that over-attachment to compassion can be problematic and can lead to suffering. Participants stated that over-attachment to deliver compassion in unfavorable conditions could lead to counterproductive outcomes:

Compassion is an important practice of Buddhism […] As a Buddhist practitioner, I want to be a compassionate leader but it is not that easy. Being compassionate is supposed to be meaningful but it is not always the case. […] employees can take advantage of my compassion […] (B1C1). Trying to impose what I believe as compassion may only fulfill my own interpretations of meaningfulness and not others’. What I consider meaningful is not necessarily what employees find meaningful and they may feel uncomfortable with it. For instance, an employee told me that because of my constant overlooking of her mistakes and being positive with her in a newly assigned project, other employees believed that she was favoured by me, and she felt stressed. So pursuing the idea of being compassionate at any price can be counterproductive and a suffering for both myself and my employees. (B25C20)

Over-attachment to compassion can result in leaders falling into the trap of being unable to navigate the fundamental paradox of meaningful work in balancing self (self-actualization in practising compassion as a Buddhist practitioner) and others (serving others’ needs by showing compassion regardless of its suitability in a given context) (Lips-Wiersma & Wright, 2012). For instance, overemphasis on mastering compassion as a Buddhist practice for participant B1C1 had a counterproductive effect in letting employees take advantage of the practice. In an effort to be compassionate and positive toward others, participant B25C20 made employees feel uncomfortable by showing favoritism. This reflects how Buddhist practices such as compassion, if not practised in the right context with the right audience, can be problematic. In other words, unskillful practice of Buddhism reflects how ‘Dharma can be abstracted from its soteriological and rhetorical context and that Buddhism can be preached without any particular audience in mind’ (Schroeder, 2011, p.559). Participants stressed that compassion alone does not always deliver meaningfulness in different contexts; hence being able to be flexible and context-sensitive based on the notion of non-attachment is crucial:

Meaningfulness both in life and at work is when you do things properly and not blindly. You give money for what? What will it be used for? Will it be used for good purposes? If you give a man a motorbike, does he know how to ride? Otherwise, it will be very dangerous […] I used to think that forgiveness and continuous advice can change a harmful attitude in an organization but unfortunately, it just further tolerated wrongdoings […] meaningfulness for me is letting go, to be contextually mindful and skillful to different individuals and different circumstances. (B29C23)

While compassion is a moral value that is central to Buddhist Mahayana moral theory, over-attachment to the practice of compassion reflects a form of desire that can lead to suffering (e.g., favoritism, being exploited, overlooking wrongdoing). In the above cases, we can see how the enactment of compassion alone can be problematic. Compassion is grounded in awareness of joint participation and engagement with relevant contexts; therefore, agency is not taken as a primary moral category (Garfield, 2021). It is imperative that compassion is enabled by skillful means to realize one’s objectives in relation to others’ needs, because claiming to have the desire to bring meaningfulness to the workplace is not the genuine meaning of compassion but an overemphasis on self-actualizing compassion. In other words, over-reliance on compassion as a feature to promote moral exemplarity (Frémeaux & Pavageau, 2022) does not prove to be an effective meaning-making mechanism for leaders.

Interchangeable Leadership

Leaders mentioned the importance of impermanence in Buddhist practice and its implications for how they perceive meaningful work:

Work for me is meaningful in different ways because you can never expect things to remain the same. […] Understanding and practising impermanence in Buddhism is crucial. For example, at times it is truly meaningful when I can help my employees either by guiding them or teaching them a lesson to learn from. Other times, especially when I was overconfident with a project but failed, I find it meaningful to be attacked by my employees and learn from them. So for me, meaningfulness can come from different angles of work or situations and at different times, from leading and even from being led by others. (B35C28)

With impermanence, the roles of leading and being led by others have become interchangeable, highlighting the dynamic interpretations and re-conceptualization of the notion of meaningful leadership, which further extends Frémeaux’s & Pavageau’s (2022) dynamics of meaningful leadership by positioning the role of leadership in an impermanent and indefinite context. This is also consistent with Buddhist ethics that place agency not as the core moral value but within the nexus of an interdependent community (Garfield, 2021). Understanding impermanence also helped leaders to detach themselves from having a desire or responsibility to lead in order to cultivate a sense of meaningful work by fulfilling employees’ expectations regardless of the impermanent context. Participants felt that fulfilling impermanent expectations can be a form of suffering, reaffirming the need to abandon such responsibility:

When employees are happy, I used to believe that I did a meaningful job. I often observed employees’ expectations and tried to fulfill them because this is how I proved my role to be meaningful and showed my compassion. But I got tired of running after expectations because employees’ expectations are impermanent and are constantly changing. It has become a burden and frustration for me. After practising Buddhism, I realized that chasing after expectations is a form of desire and attachment, leading to suffering. I am now experiencing meaningfulness from freedom from having and chasing after expectations of being a leader. (B30C24)

While participant B30C24 had been able to identify attachment to fulfilling expectations as suffering, it is important to note that releasing an attachment to something is not the same as replacing one attachment with another. In this case, individuals may externalize consequences (Vu, 2021a) and abandon leadership efforts and responsibilities due to their over-reliance on impermanence. On the other hand, respondents in our study stressed that a sense of meaningfulness is interpreted differently by different individuals so for leaders it is impossible to cultivate so-called ‘meaningfulness for everyone’ because it is part of their ‘inner self’ that can be activated most effectively only by each individual:

I try my best as a leader to cultivate a supportive working environment for my employees, but let me be clear that it is beyond me to promise that everyone will be happy and feel meaningful […] everyone has their own value system which changes once in a while and only they know what is best for them […] As a Buddhist, I learned that it is not my job to change others or the outer context; my job is to change myself in a more positive way […] to appreciate the differences in how myself and others see what meaningfulness is and how it changes over time [...] (B23C18)

Participant B23C18 highlighted that leaders are more responsible for changing the way they conceptualize meaningful work to acknowledge how meaning-making differs among different people and over time. Based on that, B23C18 argued that it is beyond leaders’ responsibility to keep up with the ‘impermanent’ way in how meaningfulness is perceived at work by different individuals. Another participant B22C28 also emphasized that keeping that ‘responsibility’ to run after meeting the impermanent expectations of others is a source of suffering.

The moment you think that you are responsible for others to feel meaningful is the moment you may start to suffer from that because you are attached to a desire that cannot be controlled by yourself. I am responsible for my actions, for my own sense of meaningfulness. But it doesn’t mean that as a leader I should impose that sense of meaningfulness on others or expect them to perceive meaningfulness in the same way. I am not responsible for other’s sense of meaningfulness. I try my best to support and to help, but people have their own inner self of meaningfulness and they should be responsible for that. (B33C28)

Participant B33C28 particularly highlighted that they do make an effort to support followers; however, their moral responsibility as a leader should not entail imposing a particular sense of meaning at work because meaning-making is both subjective and objective (Bailey et al., 2019). Some respondents also mentioned the challenges in how employees today are living their lives passively, without any active responsibility for their own well-being. Instead, they leave the responsibility for fulfilling their expectations for this to the organization.

It is really interesting to see that some employees refuse to take control of their well-being. Rather than knowing what is best for them and what brings meaningfulness for them and how they can attain and take control of it, they rely on others to deliver it. While I am not judging, as a Buddhist I know that relying on others with expectations can cause suffering. They will always suffer from having to wait for someone do things that can only be fulfilled and understood by their inner self. (B37C30)

Meaningfulness evokes a subjective response regardless of the type of activity (Frémeaux & Pavageau, 2022). This may undermine leadership agency and the ability to influence others’ sense of meaningfulness. Impermanence highlights the importance of Buddhist ethical thought that focuses on concerns with understanding how the actions of individuals are located within a web of dependent arising rather than an individual agency (Garfield, 2021). Even for themselves, leaders felt that relying on fulfilling expectations to cultivate meaningfulness is not viable and even becomes a source of suffering in the impermanent nature of organizational context:

[…] my business has had ups and downs and I also lost the respect of my employees along the way. Having expectations is therefore not a sustainable way to generate meaningful moments at work […] having expectations to be a good leader all the time is impossible. I try to maintain a successful business, but I can control neither the market nor customers’ and employees’ expectations. It is something beyond my capabilities to satisfy all and my responsibilities to maintain meaningfulness at work for everyone. It is overwhelming, unrealistic, and unnecessary to chase after what others want, what the market wants all the time and at all cost. I lost many contracts and relationships with very good local instructors that now I cannot get hold of because of following customers’ needs and employees’ expectation that prioritizing foreign instructors over local ones will bring us more clients and projects but that expectation did not last and did not work out […] It can lead to excessive desires, which are considered causes of suffering in Buddhism. (B14C11)

Participants shared the view that, as Buddhists, being able to let go of their own expectations, or even fulfilling others’ expectations of meaningfulness, is part of the practice itself in learning to live with impermanence and relinquishing desires that are beyond individuals’ interventions. B12C11 experienced the impermanent nature of success. According to the participant, meaningfulness can be lost for employees when leaders fail in running a successful business. However, expectations of being a leader that can satisfy all stakeholders may be unrealistic and therefore counterproductive: expectations of stakeholders are in constant flux and are even volatile. Indeed, participant B37C30 highlighted the subjective nature of a sense of meaningfulness regardless of leadership approaches, which undermines leadership agency and the ability to influence or take control over others’ sense of meaningfulness. Such experiences and perceptions from leaders further contribute to the argument that cultivating meaningfulness at work should not be the responsibility solely of leaders (e.g., Lips-Wiersma et al., 2020; Wang & Xu, 2019).

Response to Contextual Tensions Challenging Leaders’ Responsibility Toward Meaningful Work

The somewhat unusual way in which our participants interpreted the role of leaders in cultivating meaningful work was influenced and even challenged by both organizational and institutional constraints.

Interconnected Meaning-Making

Leaders in our study said that there needs to be a collective effort to facilitate meaningful work and that there is no one best way to do so because of its subjective nature. However, employees may often interpret this way of thinking as leaders’ reluctance to cultivate meaningfulness. This highlights the challenge of choosing to avoid trying to fulfill others’ expectations unskillfully when a sense of meaningfulness is a subjective matter.

It is always challenging for me to find a common understanding of what meaningful work means to different employees. You never get a consistent answer […] therefore, from my perspective, there is no best way to cultivate meaningfulness at work. You can only do so much to try and accept that not everybody will be happy with the way you lead, which is totally normal […] cultivating meaningful work is a collective effort (B32C25)

While a sense of meaningfulness is subjective in nature, leaders who do not show enough effort to cultivate meaningfulness at work for employees may be seen as being reluctant. However, leaders in this study felt that navigating inconsistencies in others’ subjective meaning-making at work is somewhat beyond their capabilities.

There was a conflict between leaders as Buddhist practitioners and non-Buddhist employees in the way they perceived meaningfulness and expectations differently. This conflict reflects a form of spiritual tension in the workplace. The Buddhist philosophy of impermanence (the inability to grasp the changing context and expectations of others) and non-attachment to expectations in the participants’ leadership may be misinterpreted by employees as reluctance to facilitate meaning at work. Due to how agency is not privileged as a core moral value in Buddhist ethics (Garfield, 2021), leaders pay less attention to their agency in controlling the impermanent and subjective nature of meaning-making. This was somewhat difficult for non-Buddhist employees to understand.

In response to these tensions, some leaders take a more active approach to facilitate individuals’ proactive meaning-making at work. Participant B20C15 asked employees to reflect on what is meaningful to them while reassuring ongoing leadership support when needed:

Some of my employees complain that I am not attentive to their needs to make their work more meaningful. But you know, the reality is when one expectation is fulfilled, there is always going to be another one. So I always tell them to try to actively find meaningfulness in their work first. Why did you apply in the first place? You know yourself the best and what brings meaningfulness to you. All I can do is support them along the way in the way that I can. (B20C15)

Participant B20C15’s approach somewhat reflects an efforts to cultivate interconnected meaning-making, displaying commitment to the Three Jewels in Buddhism. In this case, we can consider (1) the first jewel (the Buddha) as the symbol of the Buddhahood of leaders in becoming more enlightened leaders to support employees’ meaning-making at work; (2) the second jewel (the Dharma)—rules, organizational policies, and culture to facilitate an ethical and supportive culture for employees’ meaning-making; and (3) the third jewel (the Sangha)—a mindful community of employees who recognize both the subjective and impermanent nature of meaningful work. Within this commitment, a number of leaders, such as B20C15, tried to inspire followers to proactively seek and take ownership of their own meaning-making. However, it is worth emphasizing that whichever approach leaders take, it should be implemented as a skillful means, whereby the soteriological and rhetorical context of any particular employee is taken into consideration (Schroeder, 2011). Without skillfulness and context-sensitivity, leaders’ effort can be interpreted as reluctance (in the case of B32C25) or as instrumental effort to maintain a normative control system influencing meaning-making at work (Bailey et al., 2019).

Participants did not reject the idea of supporting employees as much as they can, but they also stressed that, other than employees themselves, there were also challenges in having to meet the expectations of shareholders which may limit their leadership ability and approaches to doing so.

I admit that it is sometimes out of my hands to promote initiatives to cultivate a more meaningful workplace due to budget restrictions and shareholders’ expectations of spending money […] I just have to accept that there are things that are beyond my control and sometimes we just have to be honest in making promises to fulfill employees’ expectations. No meaningfulness is definite, and definitely, as a leader, I will fail to deliver meaningfulness at some point. (B38C31)

This has led leaders to acknowledge that it is not possible to meet everyone’s expectations of meaningfulness at work, that failure in cultivating this process is part of the impermanent nature of all phenomena, and that employees should not rely on others to provide a sense of meaningfulness at work. Such desires can translate into suffering. In contrast to how the literature on meaningful work has suggested that individuals’ sense of meaningful work is normatively regulated by organizations and management (Bailey et al., 2019), leaders in our study rejected the need to maintain a regulated meaning-making system. This reflects the de-emphasis on agency in Buddhist ethics (Garfield, 2021).

Ethical Relativism Rather than Moral Absolutes

Participants expressed difficulties in struggling to exercise their Buddhist practice and their interpretations of meaningfulness at work when they were challenged by institutional culture.

In my role as a leader, sometimes I have to redefine my own way of interpretations of ethical values in deciding whether to go for bribes to be able to overcome bureaucratic unfairness […] in exchange for being able to distribute affordable and good medications to patients in hospitals […] meaningfulness sometimes can be blurred in such cases if I do not have a strong stance of how the practice of non-attachment may involve the redefinition of ethics and meaningfulness in some pressing contexts… (B17C13)

Buddhism encourages overcoming ignorance by letting go of desires and greed for ecological benefits. However, leaders in our study experienced struggles in practising Buddhist ethical values and setting an example for followers because of unfavorable cultural conditions. Participant B17C13 emphasized how Buddhist practices (e.g., non-attachment) need to be situated within the nexus of an interdependent community. The same applies to the contextualization of ethical values and meaning-making. This reflects how Buddhism mirrors ethical relativism (Lorenz et al., 2020; Valentine & Bateman, 2011) in judging behavior based on contextual factors rather than moral absolutes. For example, in one case it was regarded as unavoidable to be involved in bribery in the interest of the greater good of medical patients or the community. Another example was the following:

As a lawyer myself, I also find it tensional to work within this weak legal system. There are values that are beyond me to acquire in my leadership role and in this context […] it is difficult to encourage employees to explore a sense of meaningfulness when for example they need to defend corporate scandals of financial misconduct when there is a lack of a strong and supporting legal system […] being able to flexible work with what we have is key in my profession (B23C18)

Leader B23C18 felt challenged in encouraging meaning-making at work in a particular field like law due to the weak legal system of a transitional context. This shows how contextual challenges influence meaning-making in general for both leaders and employees. Another participant also highlighted how the collectivist culture in Vietnam emphasizes relational networks. Because of such strong relational dynamics in business networks, ethics is also relational in collectivist cultures, reflecting the notion of moral relativism (Brogaard, 2008) whereby moral judgments are subject to the relative expressions of ‘right’ and ‘wrong’ and the contextual variability of truth-values.

Deciding what is right and wrong is not a textbook formula. In Vietnam, you work and sustain your work based on relational networks, reciprocity, and obligations to the people you work and network with. Without respecting that cultural feature in doing business, it is not realistic to work in a long-term. (B15C12)

It is apparent that these tensions somewhat represent the impact of the Vietnamese transitional context with its high levels of uncertainty and weak law enforcement. These issues challenge leaders’ approaches in business organizational contexts in cultivating meaning-making and meaningfulness, setting an example as a meaningful leader (Frémeaux & Pavageau, 2022), and even challenging them to redefine and renegotiate their sense of meaningfulness in different contexts. This demonstrates a paradox in meaningful work between being (e.g., belonging in a collectivist context) and doing (e.g., trying to make a contribution to facilitate meaning-making at work) (Lips-Wiersma & Wright, 2012). Our findings provide a clear picture of broader cultural and contextual features (Boova et al., 2019) such as institutional constraints and cultural dynamics in a collectivist culture with an emphasis on interpersonal relationships (Kashima et al., 1995) and obligations to the group (Triandis et al., 1988). The transitional context may challenge moral exemplarity (Frémeaux & Pavageau, 2022) set by leaders within the nexus of a collectivist community.

Our findings provide a different view compared to previous studies of meaningful leadership (e.g., Frémeaux & Pavageau, 2022) that highlight interconnected meaning-making and the need to activate others’ meaning-making rather than relying on leaders’ responsibility as the core source of meaning-making at work. On the basis of the temporal and impermanent nature of meaningful work: (i) leadership agency is de-emphasized to facilitate interchangeable leadership (leading and being led) to detach from the desire to lead and cultivate a particular sense of meaningfulness at work; and (ii) leadership approaches to compassion are contextualized to navigate the mismatch between leaders’ objectives in relation to followers’ needs. Buddhist-enacted leaders tend to embrace ethical relativism rather than moral absolutes without setting a definite moral exemplarity to attend to the contextual and cultural dynamics within the nexus of an interdependent community. Table 4 below summarizes our main findings and compares features of meaningful leadership from the perspective of Buddhist ethics.

Discussion

Our study makes a number of contributions to the conceptualization of meaningful work in the context of workplace spirituality and to understanding leaders’ responsibility in cultivating meaningful work in organizations. Our study provides an alternative lens through which to examine the role of leadership from a Buddhist ethics perspective and to show how an insight from a particular tradition can enrich secular interpretations (Wong, 2020) of meaningful work and leadership (Frémeaux & Pavageau, 2022) (see Table 4).

Our findings show that, although the literature demonstrates that spirituality makes a significant contribution to the facilitation of meaningfulness at work (e.g., Lips-Wiersma, 2002; Rosso et al., 2010), Buddhist ethics and practices actually eschew the need to pursue meaningfulness at any cost. Our findings indicate the importance of the transient nature of meaningfulness that requires reflexive and context-sensitive interpretation and conceptualization. For instance, leaders in our study highlighted that, based on the Four Noble Truths, the need and desire to feel a sense of meaningfulness at all times can be a source of suffering. A sense of meaningfulness is not a static state but a dynamic one that changes over time as a result of the impermanent and dependent arising nature of all phenomena.

The notion of impermanence stresses how states of meaningfulness are temporal and transient, while the notion of dependent arising highlights how such states are conditioned by other factors (e.g., other people and the context). The state of meaningfulness is therefore beyond an individual’s control and any attempt that shows over-attachment to such a state is a source of suffering. Our study provides evidence that illustrates how a particular spiritual tradition and its ontology can introduce an alternative lens to unpack how a sense of meaningfulness and meaningful work should be situated within a wider interdependent context, rather than being attached to an individual’s desire or a particular value system.

On the basis of the above Buddhist ontology on the sense of meaningfulness, below we describe a number of leadership approaches to cultivating meanings at work. These approaches question the argument that leaders are primarily responsible for employees’ search for meaning (Lips-Wiersma et al., 2020; Wang & Xu, 2019) and provide answers to an existing question within the literature: are leaders morally responsible for meaningful work in organizations (Michaelson, 2021)?

First, context-sensitive compassion toward others to facilitate meaning at work was emphasized as one of the leadership approaches. When there is a mismatch between leaders’ objectives and subjective interpretations of what meaningful work for followers is (Frémeaux & Pavageau, 2022), tensions tend to arise. Tensions intensify when the paradox between self (e.g., self-actualization in leadership approaches to deliver meaningful work) and others (e.g., others’ interpretations and expectations of meaningfulness) cannot be balanced and there is an over-attachment to one over the other. It is impossible for leaders to be compassionate all the time to facilitate meaningful work when such compassion can be interpreted differently by followers. For instance, in our study, some employees considered compassion to be favoritism. The reason is that in some contexts (e.g., tolerating wrongdoing and being taken advantage of), compassion and a positive attitude can become counterproductive, which does not cultivate a sense of meaningfulness for leaders and followers. People’s sense of meaningfulness changes when successful performance at work leads to enhanced expectations and compassion cannot always be maintained. Context-sensitivity in compassion is therefore crucial and leaders need to reflect on what is the ‘right amount’ or ‘right type’ of meaningful work (Bailey et al., 2019) in a given context.

Taking a context-sensitive approach to interpreting what meaningfulness is, leaders were able to move out of their leadership role and embrace meaningful moments by being led by their followers, facilitating interchangeable leadership. Interchangeable leadership differs from the conventional understanding of meaningful leadership through self-awareness in which leaders search for coherence between their leadership behavior, how they are perceived, and who they are (Frémeaux & Pavageau, 2022). Influenced by the Buddhist notion of impermanence, leaders tended to understand their roles of leading and being led as interchangeable, positioning both the role of leadership and the notion of meaningfulness as transient and impermanent states. Agency as a core moral value is no longer emphasized as a sense of meaningfulness is in constant flux (Mitra & Buzzanell, 2017) and meaningfulness arises in impermanent, in-between times and spaces rather than from everyday norms (Toraldo et al., 2019).

The interchangeable leadership approach shows how meaningfulness is a reflexively co-constituted concept by the self and others (Cooley, 1902; Schalk, 2011). A sense of meaningfulness can be interpreted differently by different individuals because it is closely related to an individual’s inner self and value system: what is meaningful or meaningless remains subjective (Rosso et al., 2010; Weeks & Schaffert, 2019). In our study, leaders realized that their own sense of meaningfulness may differ from their followers’ and, with interchangeable leadership, different perspectives on meaningfulness can be unpacked.

Third, as part of leaders’ practice of non-attachment to their followers’ expectations, leaders were of the opinion that it was important to activate others’ meaning-making as a leadership approach to facilitate meaningful work. Expectations for meaningfulness differ not only within individuals but also within different contexts, which makes it challenging to fulfill expectations of a definite state of meaningful work. Therefore, rather than just emphasizing personal and professional support (Frémeaux & Pavageau, 2022), our participants emphasized the need to facilitate individuals’ inner self to recognize and take ownership of meaning-making at work. Individuals have the capacity and the moral responsibility (Michaelson, 2011) to deconstruct what is subjectively meaningful to them at work. It is more important for leaders to provide support where needed to encourage individuals’ meaning-making efforts rather than presumptively imposing a specific sense of meaningfulness on their followers. Our study, therefore, provides further evidence of the problematic nature of conceptualizations of meaningful work that requires leaders to be primarily responsible for delivering meaning and assisting employees in their search for meaning (Lips-Wiersma et al., 2020; Wang & Xu, 2019).

However, leaders need to be mindful not to be trapped into being perceived as being reluctant or instrumental in trying to make individuals take ownership of their meaning-making. Some employees ascribed such leadership approaches simply to reluctance. It is therefore questionable whether Buddhist-enacted leaders had the tendency to over-rely on the external context and to fail to consider circumstances where their leadership could have contributed much more in cultivating workplace meaningfulness. We argue that leaders may benefit from adopting mindfulness in their leadership approach to empowering followers in their search for meaningfulness in their work. Mindfulness can facilitate self-correction and reflexivity (Purser & Millilo, 2015; Vu & Burton, 2021; Vu et al., 2018) for leaders in identifying extreme approaches that make followers fully responsible for meaningful work, without making any effort or taking leadership responsibility. Leaders can mindfully question their understanding of how they interpret meaningfulness (self-reflexivity) and how they evaluate the relevant context (critical reflexivity), to assess their leadership and to avoid reluctance in cultivating meaning at work. A mindful approach to leadership encourages leaders to acknowledge the dependent arising nature of meaning-making, thus embracing collective responsibility in facilitating meaningful work as well as the responsibility to activate others’ meaning-making efforts at work.

Fourth, a sense of meaningfulness that is derived from an individual’s inner self gradually becomes embedded in society and is influenced by organizational context (Tablan, 2015). Acknowledging the role of others in the construction of the meaning of work, therefore, is important (Wrzesniewski, 2003). For these reasons, there is a need for leaders to embrace interconnected meaning-making to situate the inner self within the nexus of an interdependent community. Such an approach would facilitate the construction of shared meaning-making and extend community spirit at work (Frémeaux & Pavageau, 2022). Our findings reaffirm how a sense of meaningfulness at work cannot be engineered or put under agency control of leadership alone because of its subjectivity (Ciulla, 2012; Lips-Wiersma & Morris, 2009) and its interrelated nature.

Lastly, Buddhist-enacted leaders highlighted the need to adopt ethical relativism in their leadership (Lorenz et al., 2020; Valentine & Bateman, 2011) to judge behavior based on contextual factors rather than on moral absolutes. For instance, in this study, shareholders’ expectations or requirements and even weak legal enforcement, along with institutionalized corruption, contributed to the impermanent and ‘beyond control’ features of an absolute standard of meaningful work that individuals experienced. Therefore, the notion of moral exemplarity as a feature of meaningful leadership (Frémeaux & Pavageau, 2022) cannot always be maintained by leaders because ethicality must be understood as an aspect of contextual and cultural narratives (e.g., institutionalized systems and the collective culture embedded in network relationships). This, however, can question a leader’s effort in setting an example, particularly in the context of cross-cultural management. Leaders can be criticized for using their cultural knowledge to bend moral rules (Lorenz et al., 2020).

We argue that leaders need to adopt a skillful approach to enhancing moral reflexivity (Vu & Burton, 2021) and attending to situations that may require them to reflect back on the appropriateness of their understanding and leadership in cultivating meaning at work. While moral relativism in leadership in our study was based on the Buddhist ontology, in the Buddhist philosophy, it is emphasized that all Buddhist teachings are skillful means that should be rejected when deemed inappropriate in certain contexts (Schroeder, 2004). Attachment to one particular practice is considered an unskillful path of practice in the Group Discourses of the Buddha (Saṃyutta Nikāya, SN36.23). It is important, for example, to skillfully moderate moral relativism in leadership and to recognize how spiritually embedded leadership practices may not be compatible with followers’ values, spirituality, or religiosity (Spoelstra et al., 2021; Vu et al., 2018).