Abstract

Human Quality Treatment (HQT) is a theoretical approach expressing different ways of dealing with employees within an organization and is embedded in humanistic management tenants of dignity, care, and personal development, seeking to produce morally excellent employees. We build on the theoretical exposition and present a measure of HQT-Scale across several studies including cross-culturally to enhance confidence in our results. Our first study generates the 25 items for the HQT-Scale and provides initial support for the items. We then followed up with a large study of managers (n = 363) from Nigeria in study 2, which confirms the theoretical properties of the five dimensions of HQT and highlights a two-factor construct: HQT Ethically Unacceptable and HQT Ethically Acceptable using a 20-item HQT-Scale. Study 3 with a large sample of New Zealand employees (n = 452) again confirms the nature of the construct and provides construct validity tests. Finally, using time-lagged data, study 4 (n = 308) focuses on New Zealand employees and job attitudes and behaviors, and a well-being outcome. That study not only confirms the theoretically implied effects but also shows the HQT Ethically Acceptable factor mediates the detrimental effects of HQT Ethically Unacceptable. Overall, our four studies provide strong support for the HQT-Scale and highlight important understandings of HQT and humanistic management in the workplace.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Find the latest articles, discoveries, and news in related topics.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Humanistic management (or HM), broadly speaking, makes human beings and their well-being the central purpose of managing in organizations. For Melé (2016), HM goes beyond simply treating employees as resources to moral reflection on the nature of humans and the ideal way they should be treated, as well as promoting human flourishing through commercial activities that add value to society and enhance human living. According to neoclassical economics, firms are a collection of self-interested competitive individuals who enter a nexus of contracts to maximize their utility (Lips-Wiersma & Nilakant, 2008), without any real concern for shared values or common goals, including the wider good of society. From an HM perspective, firms are a community of persons who flourish when managers promote unity, favor the acquisition of human virtues, and aim at the common good (Melé, 2003). Consequently, HM centers “on building up a community of persons embedded within an organizational culture which fosters excellent moral character” (Melé, 2003, p. 82).

From a business case perspective, HM seems good for business (Vogel, 2005; Wang et al., 2016; Arnaud & Wasieleski, 2014), although several authors have noted that performance outcomes are not necessarily moral ends in themselves (Arjoon, 2000; Sison & Fontrodona, 2012). Also noted by Spitzeck (2011), is the argument that HM provides moral legitimacy to the business with its stakeholders, as well as ensuring “that the chosen course of conduct improves the life conduciveness of all parties involved” (p. 53). For example, it enables organizations, and managers, to differentiate between inhumane (i.e., sweatshops) and humane treatment (i.e., safe work and fair wages). Despite growing attention to HM, more research is needed. As Melé (2003) observes, there is a requirement “for new research in order to delve into the relationship between these concepts and practical ways to carry out this humanistic management” (p. 85).

If the goal of HM is to produce morally excellent human beings who enhance firm and wider societal flourishing, then developing a measure of HM’s effectiveness in organizations would be beneficial. Certainly, measures exist of management ethical conduct toward employees (see, e.g., Shanahan & Hyman, 2003; Brown et al. 2005; Liden et al., 2008) as well as how managers can foster ethical climates (Grojean et al., 2004). However, these do not explicitly consider management, or organizational, capacity to develop employee moral excellence from a humanistic perspective. Starting with the notion that quality is a frequently used term in manufacturing and engineering, Melé (2014) notes that the word is rarely applied to human beings’ treatment. Using the basic idea that quality is about the improvement of processes with the aim of performance excellence, Melé coined the term Human Quality Treatment (HQT) as a way of evaluating HM within organizations. He argues that HQT requires managers to consider the implications of treating employees as more than resources whose utility they have a responsibility to maximize (Grawitch et al., 2006; Van De Voorde et al., 2012), but rather as human beings that have “intrinsic value and [an] openness to flourishing” (Melé, 2009, p. 413).

Consequently, the primary goal of this paper is to develop a scale based on the notion of HQT, which Melé (2014) defined “as dealing with persons in a way appropriate to the human condition, which entails acting with respect for their human dignity and rights, caring for their problems and legitimate interests, and fostering their personal development” (p. 462). Such a scale can be used by managers to reflect on how they have dealt with or are dealing with people from a HM perspective or to determine the current situation of their firm regarding humanistic ends to maintain or increase the quality level. The second goal of the paper is to test this scale on two distinct employee samples from Nigeria and New Zealand to determine its cross-cultural validity. The paper’s final goal is to highlight the importance of HQT to employee work and well-being outcomes. It is important to understand the influence HQT has on employee outcomes to further enhance the importance of a HM approach within organizations.

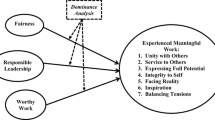

The Human Quality Treatment Model

For Melé (2014), appropriate humanistic treatment of employees includes each of three aspects: respect, care, and intelligent love. Respect involves treating people as rational free beings and not as instruments. Nor does it mean treating people indifferently. Care involves the “will solve the real, and not frivolous, problems of the other, and is not simply a question of satisfying their desires” (p. 462). Finally, benevolence, understood as intelligent love, fosters the will to work for the good of persons and the common good of society. This is an “attitude of true esteem for people in such as to promote a development of the whole person” (p. 462) and especially their moral excellence. From these ideas, Mele developed the HQT model, which evaluates the effectiveness of management to enrich eudaimonic well-being in organizations (Melé, 2014). Simply put, this model ranks the treatment of employees, by managers, from a humanistic perspective using five levels of quality: maltreatment, indifference, justice, care, and development (see Fig. 1).

Melé’s (2014) five levels of human quality treatment model (p. 463)

Maltreatment is the lowest level in Melé’s (2014) model. This refers to any exploitative use of power that leads to inequity, harm, and any form of abuse. This includes such things as paying employees less than fair wages, violating their human rights, and forcing them into inhumane work conditions. It also encompasses things like harassment and bullying, favoritism, discrimination, and misleading, or being dishonest toward, staff. Indifference, Melé’s (2014) second level, covers behavior that is legal but disrespectful to human beings. At this level, employees are primarily viewed as resources for achieving economic ends, and the only requirement for an organization regarding their treatment is obedience to the law. While this perspective has been previously labeled ‘socially responsible’ (Friedman, 1970; Sternberg, 1995), Melé (2014) argues it fails to treat employees with dignity and care. Not surprisingly, such indifference is most clearly evidenced in organizations where there is a lack of straightforward reporting lines for employees to receive or give feedback, and management has little interest in employee opinions or needs. Melé considers both these levels ethically unacceptable.

Contrary to the indifference level, an organization at the justice level treats employees equitably and with respect. This means recognition of their “innate and acquired rights, not only the legal, but also those which correspond to them through morality” (Melé, 2014, p.464). Recognizing a person’s dignity means organizational communication processes are more two-way, performance is evaluated openly and honestly, and employee voices are encouraged and listened to. At this level, compensation reflects work done, and the selection and dismissal of employees occurs fairly and transparently; no employee should be subject to arbitrary decisions. According to Melé (2014), justice is the minimal level for meeting the ethical obligations for HQT.

The next level care moves beyond “recognition and respect for rights” toward a “concern for the person’s legitimate interests and provision of support to resolve their problems” (Melé, 2014, p. 464). Care involves showing a genuine interest in people and their difficulties both at work and in private contexts. Managers who practice care are tolerant when mistakes or conflict occur, and they help relevant persons to work through these situations positively. When decisions that impact negatively on employees must be made, there is a significant attempt to minimize damage. While there are some similarities here with emotional intelligence, this is not simply empathizing with employees or feeling sorry for them. Care is a moral response that has ethical obligations; it is not just “an expression of spontaneous sentiment” (p. 465).

The highest level is called development, which is characterized as “a willingness to serve people’s real needs, which is those which contribute to their human flourishing, and so to promote the development of their humanity and virtuous behavior” (Melé, 2014, p.465). While this level involves respecting others’ rights (justice) and showing legitimate concern for their interests (care), it also means helping cultivate their natural gifts and moral character. This means, for example, providing training and development that nurtures not just their technical competencies, but also their moral proficiencies. By maximizing people’s talents, managers can create “a virtuous circle of human flourishing, mutual esteem and a willingness to serve and cooperate” (Melé, 2014, p. 465). As stated earlier, such cultivation is only possible if managers understand the nature of human beings and if they consider the employee’s situation. Growing in virtue does not happen in isolation; one’s surrounding context has a significant bearing on virtue development. Indeed, several studies have shown that subordinate behavior is, in part at least, a reflection of how managers communicate and act on their values (Brown et al., 2005; Duchon & Drake, 2008; Flynn, 2008).

To date, only a single qualitative study exists that explores the HQT model, whereby Ogunyemi and Melé (2014) analyzed several small to medium-sized Nigerian firms’ HQT of their employees. Their findings verified the HQT levels as well as several concepts that pertain to these levels. Despite these outcomes, Ogunyemi and Melé noted the need for more research to confirm the HQT model and to apply it across diverse organizations from various contexts. After all, HQT is a reasonably new idea for managers. Usually, the quality of employee treatment is associated with constructs such as satisfaction, hedonic well-being, and employee engagement. By challenging organizations to aim for higher ends (e.g., eudaimonic well-being), HQT goes further. As such, it encourages managers and employers to develop cultures with a shared and deep-rooted sense of community, where employees can develop moral excellence and flourish.

HQT may be especially relevant for organizations that claim they have an ethical culture already or organizations striving to achieve such a culture. We next discuss the theoretical lens we used to understand how an HQT climate can influence employee outcomes.

Social Exchange Theory

Social exchange theory (SET) (Blau, 1964) reflects the relationship of give and take between parties, typically employer–employee, and captures the potential reciprocation when actions are desirable or valued. Haar and Spell (2004) highlight that “felt obligation is based on cultural rules of behavior in social exchange situations” (p. 1041). Thus, when an employer provides something of value to their employees (e.g., a workplace high on the HQT), then recipients (i.e., employees), because of reciprocity norms (Gouldner, 1960), feel obligated to react in kind. Kurtessis et al. (2017) note that SET is a theoretical approach to explain employee attitudes and behaviors, with greater reciprocation by employees found when employers provide stronger support.

This might include higher job attitudes like job satisfaction. Haar (2006) states that SET “suggests that employees who value benefits received from their organization, such as pay, fringe benefits or working conditions, will reciprocate with more positive work attitudes” (p. 194). Importantly, SET can be used to understand why employees provide fewer desirable attitudes and behaviors, which theoretically occurs when one parties’ action is poor and under-valued. This aligns well with the HQT and its multiple levels. Employees who believe their organization is condoning maltreatment and indifference may reciprocate with poorer outcomes, such as thinking about leaving their job.

Theoretically, employee perceptions of their organization considering the HQT framework should reflect negative attitudes and behaviors at the bottom of the model (maltreatment and indifference) and become more positive at higher levels (justice, care, and development). Theoretically, as the actions of an organization are seen as becoming more genuine and caring, then employees are strongly driven to reciprocate with enhanced attitudes and behaviors. These felt obligations (Haar & Spell, 2004), while not guaranteed (Gouldner, 1960), are commonly evidenced (e.g., Kurtessis et al., 2017). This applies to HQT, as employees will recognize and acknowledge that not all employers operate on high HQT levels (i.e., care and development) and instead are characterized by low HQT levels (i.e., maltreatment and indifference).

HQT-Scale Development and Validation

Human treatment at work has been subject to study from a variety of perspectives—especially by researchers in human behavior and psychology. For instance, scholars have attested to the need for, and importance of, respecting the human rights of their employees in order to comply with requirements of law and respect for human dignity (Arnold, 2010; Bolton, 2010; Caldwell, 2011) and to ensure distributive, procedural, and interpersonal justice (Andersson & Pearson, 1999; Ambrose et al., 2002). Others have advocated for transformative forms of leadership (e.g., ethical, servant, and responsible) in order to achieve optimal attitudes and performance from employees (Parris & Peachey, 2013; Stahl & De Luque, 2014; Bedi et al., 2016). With the introduction of HQT, this area is extended by giving it an ethical perspective that looks at the human quality of people’s treatment.

An organization that seeks to be ethical in its dealing with stakeholders will constantly strive to treat its employees appropriately as part of this effort. Therefore, it becomes useful to measure HQT to recommend methods of continuous improvement. Additionally, given how people are treated is likely to have an impact on key job outcomes (e.g., job satisfaction and turnover intentions), which in turn could affect the transaction costs of the firm, it would appear desirable to measure this newly revealed antecedent of attitude and behavior. The present study extends the HQT literature by evaluating a quantitative HQT measure. Several instruments are measuring similar constructs. For example, both Donovan et al. (1998) and Keashly et al. (1994) developed measures of interpersonal treatment at work, while others have focused on how well organizations value employee contributions and whether they care about employee well-being (see Kurtessis et al., 2017). The HQT-Scale goes further in attempting to capture organization-wide culture, structure, practices, and processes and to estimate the quality of people treatment within the organization as a whole from an eudaimonic perspective. Importantly, the HQT-Scale has a unique approach whereby the different levels are expected to have detrimental effects for the first two levels (maltreatment and indifference) and grow steadily more positive through the other three levels (justice, care, and development) (Melé, 2014).

We look to test our HQT-Scale using four studies: (1) initial scale development and pilot testing, (2) large-scale testing of the construct, (3) construct validity tests (Campbell & Fiske, 1959), and (4) enhanced methodology using time-lagged data (Podsakoff et al., 2003). All studies received university ethics review board approvals. We detail the studies below.

Methods

Study 1: HQT-Scale Item Generation

This first study adopted a conceptually focused approach (DeVellis, 2003; Netemeyer et al., 2003). It began by splitting the framework of HQT into the five levels and then breaking these into items. Consequently, the meaning of each level was operationalized for measurement purposes. Several assumptions provided direction in this scale development. First, the level of analysis is the organization. The scale attempts to determine degrees of HQT in organizations, or at least in collective entities, rather than at the level of dyads or the individual level. Second, an initial audience was specified for the survey to avoid responses being skewed and we focused on middle managers since it was felt that they would be best placed to address the factual situation of their organization. Third, to elicit objective facts rather than perceptions, the questions were framed to evoke answers based on knowledge of past events and current factual situations. A Likert scale design asking for frequency of occurrences also worked to focus respondents on factual details. Finally, not all organizations are at the same level with regard to formal structures. Structures and systems that might exist informally need to be considered. Therefore, for example, rather than asking whether promotion processes were fair, it was decided to ask whether promotion decisions were fair—as not all organizations would have processes. Similarly, when asking about coaching or mentoring systems, care was taken to clarify that the items envisaged both formal and informal systems.

Item Development

After determining assumptions regarding the HQT-Scale’s contents and limitations, we next generated HQT items informed by the literature and the aforementioned qualitative study by Ogunyemi and Melé (2014) which explored the levels of HQT with small and medium-sized enterprise (SME) employees in Nigeria. The researchers generated many items as potential measures of the five levels of HQT. These were then edited for clarity, accuracy, and parsimony. Several panels were convened representing a variety of groups to review the items. These included a panel of Professors in Business Ethics & Statistics and Ph.D. students at Lagos Business School in Nigeria, and Ph.D. students at IESE Business School in Barcelona, Spain. Combined, these three groups represented the continents of Asia, Europe, Africa, and the Americas. Each item was evaluated by panel members who were then invited to comment on relevance, clarity, cultural neutrality, and redundancy (cf., Foody, 1998).

Items for the HQT levels were generated from numerous sources, mainly Melé (2011; 2014; 20162003, 2009) and Ogunyemi and Melé (2014), but also specifically for levels of maltreatment (see, e.g., Cortina et al., 2001; Matsunaga, 2010; Matthiesen & Einarsen, 2010), indifference (see, e.g., Andersson & Pearson, 1999; Cortina et al., 2001; Schneider, 1999), justice (see, e.g., Arnold, 2010; Gross, 2010; Caldwell, 2011), care (see, e.g., French & Weis, 2000; Grant, 2008; Caldwell, 2011), and development (see, e.g., Jaramillo et al., 2009; Okpara & Wynn, 2008; Weaver, 2006). Initially, sixty-seven items were generated. To avoid anchoring respondent answers, the items were arranged in alphabetical order rather than according to their levels. The items took the form of statements rather than questions. Each statement required an answer in order for the respondent to move to the next item, using a Likert scale, coded 1 = not at all, to 5 = almost always.

These items were used in a pilot anonymous online survey with 55 Executive MBA participants in Lagos, Nigeria (these results are not shown due to the small sample size). Respondents scored each statement by indicating the extent to which it reflected the real situation in their organizations and then provided feedback around improving the instrument (e.g., issues around clarity of meaning). Overall, this feedback along with further consultation from expert panels produced a list of 25 items ready for initial testing, which we call the HQT-Scale. See Table 1 for items including a breakdown across samples (2–4). We used a mixture of reverse-coded items to aid the psychometric properties of the scales. This also ensured the ethically unacceptable items tapping levels 1 and 2 of the HQT (maltreatment and indifference) represented organizational actions where a higher score represented more of the unethical treatment (i.e., more maltreatment and greater indifference to employees).

Study 2: Initial HQT-Scale Validation

Sampling and Procedure

A large empirical study was conducted with Lagos Business School (Nigeria) alumni to test the HQT-Scale. We emailed an invitation to 676 alumni to complete an electronic survey that included the 25-item HQT-Scale, demographic questions, and validation items. In return, we received 413 responses. We removed CEO responses given the potential bias they might have toward their own companies and removed incomplete responses, which resulted in 363 usable surveys (53.7%). Respondents were mostly male (61.4%), with most of the sample (87.1%) below 50 years of age, with only 8% of these being below 30. These figures reflect business demographics in Nigeria, where managers are primarily men aged between 30 and 50 (Okafor et al., 2011). Almost all survey respondents had postgraduate education. This is also common in Nigeria, where many complete a master’s degree early in their careers, and where many people progress in their chosen profession by getting advanced degrees (Ituma et al., 2011). Most were in middle- to upper-level management positions (86.8%) and worked in medium (50–249 employees) to large organizations (250 + employees). While such characteristics might reflect a high-level executive in Western settings, in the Nigerian context, this is not the case. These employees are likely to be paid not much more than employees below them at the next lower organizational level.

Measures

We used the 25-item HQT-Scale developed from study 1 (shown in Table 1), assessing the five HQT levels, coded 1 = strongly disagree, 6 = strongly agree.

Analysis

Because most of the dimensions of the HQT exist in some form (e.g., organizational justice), we conducted Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) using structural equation modeling (SEM with AMOS version 26) to test our measures (Schreiber et al., 2006). Since SEM is a confirmatory procedure, it provides an ideal way to test hypothesized models against specific datasets. It is effective for confirming the factors of a scale in scale development, and for estimating a model for interrelationships among different observed and latent variables (Schreiber et al., 2006). Finally, we performed a correlation analysis to compare the HQT-Scale’s five levels.

Results

Within the SEM literature, several goodness-of-fit indices are highlighted (e.g., Williams et al., 2009) such as (1) the comparative fit index (CFI ≥ 0.95), (2) the root-mean-square error of approximation (RMSEA ≤ 0.08), and (3) the standardized root mean residual (SRMR ≤ 0.10). However, Hu and Bentler (1998) caution that “it is difficult to designate a specific cut-off value for each fit index because it does not work equally well with various types of fit indices” (p. 449). This is due to various factors like sample size and distributions. They do note that “considering any model with a fit index above 0.9 as acceptable” and thus for (1), we relax the threshold to CFI > 0.90. Our CFA in study 2 resulted in an acceptable fit to the data: χ2(265) = 1081.4 (p = 0.000), CFI = 0.90, RMSEA = 0.08, and SRMR = 0.06. Alternative CFA models, whereby various levels were explored together (e.g., combining care and development), these all resulted in a significantly poorer fit to the data (all p < 0.001). Finally, we tested a higher-order model, whereby our five HQT levels might represent a global factor, but this was also an inadequate fit to the data (p < 0.001). However, we did explore a higher-order model that reflects the negative HQT levels (maltreatment and indifference) and the positive HQT levels (justice, care, development) and this was an adequate fit to the data: χ2(272) = 1117.8 (p = 0.000), CFI = 0.90, RMSEA = 0.09, and SRMR = 0.06. Hence, there is initial support for a 2-factor HQT-Scale.

Our CFA data (Factor Loadings) are presented in Table 2 (including studies 2–4) and correlations are in Table 3.

Overall, our five HQT dimensions fit the theory well. The two bottom dimensions of the HQT: Maltreatment (M = 2.22) and Indifference (M = 2.95) correlate highly with each other (r = 0.70, p < 0.01) and have low mean scores, both below the mid-point of 3.5. As we might expect, such perceptions are less numerous but similar. The other three higher HQT dimensions of Justice (M = 3.81), Care (M = 3.67), and Development (M = 3.75) are all above the mid-point, all correlate highly with each other (all p < 0.01) and all correlate strongly (and negatively) with the bottom two HQT dimension (all p < 0.01). All dimensions of the HQT-Scale achieved adequate reliability (all α > 0.70). Overall, we suggest this gives us initial validation for our construct.

Study 3: HQT-Scale Validation

Sampling and Procedure

We sought to test the HQT-Scale in another country to enhance confidence in its psychometric properties. Data were collected from a Qualtrics survey panel on a broad range of New Zealand employees, working at least 20-h/week. The sample comes from a largely representative group by gender and geographic location. Qualtrics participants are anonymous, and the system removes participants who respond too fast or too slow to the survey, and they can only do the survey once. Overall, Qualtrics provides quality employee samples (e.g., Kang & Hustvedt, 2014; Haar et al., 2018a). A total sample size of 452 respondents was gathered, consisting of 50% male/female, with a median age of 39.0 years (SD = 10.0 years) and median tenure of 4.4 years (SD = 3.2). The sample was predominantly New Zealand European (60%) and educated (52% university degree), with 70% working in the private sector.

The focus of study 3 was to conduct validity tests (Campbell & Fiske, 1959) by undertaking both convergent and discriminant tests to provide support for our HQT-Scale, following typical approaches in the literature (e.g., Aritzeta et al., 2007). Fiske (1971) stated that convergent validity “is a minimal and basic requirement” (p. 164) for a new construct, with convergent validity defined as “substantial and significant correlations between different instruments designed to assess a common construct” (Duckworth & Kern, 2011. p. 259). While convergent validity looks for similarities, discriminant validity is a check for differences, with Wahlqvist et al. (2002) defining it “as a low correlation between the measured variables and measures of a different concept” (p. 109). Discriminant validity occurs when a construct has a low correlation value with one variable that in turn is related to another (Wahlqvist et al., 2002). Overall, we would expect the HQT-Scale dimensions to correlate significantly with other global perceptions of the organization for discriminant validity but then not be highly correlated with other factors.

Measures

We used the HQT-Scale developed from study 1 to assess the 5 dimensions of HQT, coded 1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree. We looked to tighten the construct by exploring the potential for a smaller number of items and used the best 4-items per dimension from study 2 considering their Factor Loading score and their frequency. For example, item 5 “There are incidences of sexual harassment” had the lowest frequency score, and paired t-tests confirmed it was significantly lower than all other items in that HQT level (all p < 0.001). Tables 1 and 2 show the items used and associated scores for the new 4-item per HQT 5 dimension. All dimensions of the HQT-Scale in study 3 achieved adequate reliability (all α > 0.70). Following the 2-factor HQT higher-order findings, we then created two composite scores: HQT Ethically Unacceptable which relates to the ethically unacceptable HQT levels of maltreatment and indifference combined (α = 0.87), and HQT Ethically Acceptable that combines the levels of justice, care, and development (α = 0.95) (Melé, 2014).

For a test of discriminant validity, we used an organizational construct with strong meta-analytic support (Kurtessis et al., 2017) which similarly is grounded in SET. Perceived organizational support (POS) was measured by 4-items from Eisenberger et al. (1986) coded 1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree. A sample item is “My organization would ignore any complaint from me” (reverse coded), and this had strong reliability (α = 0.88).

For a test of convergent validity, we used an individual psychological construct. Mindfulness was measured using the Brown and Ryan (2003) Mindful Attention Awareness Scale, with 3-items drawn from Höfling et al. (2011) short scale coded 1 = never to 5 = all of the time. A sample item is “I find myself doing things without paying attention” (reverse coded), and this had strong reliability (α = 0.86).

Analysis

Again, we used SEM to conduct a CFA to confirm the factor structure of the HQT-Scale. We then conducted a correlation analysis to determine the distinctive nature of our HQT-Scale.

Results

Our CFA results of the five dimensions of the HQT-Scale in study 3 are shown in Table 2. Ultimately, the CFA resulted in good fit to the data: χ2(160) = 595.3 (p = 0.000), CFI = 0.93, RMSEA = 0.08, and SRMR = 0.05. When the construct validity measures were included, the CFA still resulted in good fit to the data: χ2(303) = 848.6 (p = 0.000), CFI = 0.94, RMSEA = 0.06, and SRMR = 0.05. We tested alternative CFA models whereby various HQT-Scale dimensions were explored together and this resulted in a significantly poorer fit to the data (all p < 0.001). Similarly, a poorer fit was found (all p < 0.001) when the dimensions were tested in combination with the POS items. Finally, we tested the HQT as a higher-order model, and similar to study 2, this resulted in a poorer fit to the data (p < 0.001). Again, we found support for the 2-factor HQT higher-order model: χ2(167) = 632.6 (p = 0.000), CFI = 0.93, RMSEA = 0.08, and SRMR = 0.06, which is important as we move toward ultimately testing the HQT toward outcomes.

Finally, given the HQT focus and a potential bias with higher-paid workers (over low-paid workers), we also tested responses by income, to ascertain if differently paid workers viewed the HQT differently. Thus, a multi-group CFA analysis was conducted to establish measurement invariance between respondents and income. The median income in New Zealand is roughly NZ$55,000, and we captured income in three bands: 1 = up to $55,000, 2 = $55,001-$100,000, and 3 = $100,001 and above. Finding measurement equivalence would show that HQT is viewed similarly, irrespective of income. It also supports combining all respondents. We followed the metric invariance logic of Haar et al. (2014), and the difference in RMSEA was small (0.001) between the three groups, supporting their combination.

Study 3 correlations are in Table 4.

Similar to study 2, in study 3 our five HQT dimensions fit the theory well. The two bottom dimensions of the HQT: Maltreatment (M = 2.37) and Indifference (M = 2.44) are highly correlated with each other (r = 0.63, p < 0.01) and have low mean scores, both below the mid-point (3.0). The other three higher HQT dimensions of Justice (M = 3.36), Care (M = 3.47), and Development (M = 3.31) are all above the mid-point, all correlate highly with each other (all p < 0.01) and all correlate strongly (and negatively) with the bottom two HQT dimension (all p < 0.01). All dimensions of the HQT-Scale achieved adequate reliability (all α > 0.70). These findings supply evidence of validation for our HQT-Scale construct cross-culturally.

We now focus on the HQT 2-factor higher-order constructs: HQT Ethically Unacceptable and HQT Ethically Acceptable. For our test of convergent validity, we would expect both factors: HQT Ethically Un/Acceptable to be significantly related to POS (negatively and positively). We do find strong support for convergent validity, with HQT Ethically Unacceptable correlating significantly with POS (r = -0.66, p < 0.01) as does HQT Ethically Acceptable (r = 0.58, p < 0.01). We also find useful evidence of discriminant validity, with mindfulness being non-significant toward HQT Ethically Acceptable (r = -0.01, non-significant) while HQT Ethically Unacceptable correlates significantly but only modestly (r = -0.19, p < 0.01). Importantly, POS is also significantly correlated with mindfulness and at a stronger level (r = 0.24, p < 0.01), supplying useful support for discriminant validity (Wahlqvist et al., 2002).

Finally, ANOVA analysis was conducted to explore HQT Ethically Acceptable and Ethically Unacceptable by income, following Haar et al. (2014), using the Student–Newman–Keuls (SNK) test of difference. This showed no significant difference between HQT Ethically Acceptable (F = 0.137, p = 0.872) and HQT Ethically Unacceptable (F = 1.281, p = 0.279). Hence, these scores did not differ by the income earnt by respondents.

Study 4: HQT-Scale and Consequences

In study 4, we offer hypotheses linking our HQT-Scale to outcomes.

Hypotheses

Here, we argue that employees will recognize the manager’s superior efforts of focusing on the higher ends of the HQT and thus, through the felt obligation, respond with extra positive job attitudes (e.g., increased satisfaction, and lower turnover intentions). There exists strong meta-analytic backing for SET leading to enhanced job attitudes and behaviors (Kurtessis et al., 2017). Thus, as employees perceive their organization climate to be more aligned with higher levels of HQT, we expect them to report more beneficial job attitudes and behaviors. Further, SET has been found to similarly positively shape well-being outcomes. Kurtessis et al. (2017) explain that perceptions of support influence employee well-being through psychological mechanisms, stating “perceived organisational support should fulfil socioemotional needs, increasing the anticipation of help when needed” (p. 1871).

We hypothesize the effects of HQT across the levels that correspond to negative and positive ethical experiences within organizations: (1) HQT Ethically Unacceptable levels, which capture the lowest levels of HQT (i.e., maltreatment and indifference), and (2) HQT Ethically Acceptable levels, which captures the higher levels (i.e., justice, care, and development). HQT Ethically Unacceptable includes the lowest level in Melé’s (2014) model (maltreatment), which reflects inequity, harm, and abuse. All forms of organizational behavior that should lead to negative outcomes under SET. Similarly, indifference reflects disrespectful treatment of employees (Melé, 2014), which again reflects poorly under SET. Theoretically, employees return positive attitudes and feelings when they know they are supported and can rely on their organization (Kurtessis et al., 2017). While empirical studies of SET typically take a positive approach (e.g., Haar & Spell, 2004), some researchers highlight that workers respond negatively to unfavorable treatment under SET (Parzefall & Salin, 2010). Here the treatment is detrimental and thus is actively discouraged by employees, through reporting poorer job attitudes for example. Theoretically, we expect HQT Ethically Unacceptable to be detrimental to all outcomes.

Alternatively, the HQT Ethically Acceptable is more likely to align with meta-analyses based on SET, whereby employees will report enhanced job outcomes and superior well-being (Kurtessis et al., 2017). Thus, HQT Ethically Acceptable is expected to be beneficial to all outcomes. Finally, under the HQT approach (Melé, 2011, 2014, 2016), we would also expect HQT Ethically Acceptable to mediate the influence of HQT Ethically Unacceptable levels. We posit the following broad hypotheses:

Hypotheses 1

HQT Ethically Unacceptable will be detrimentally related to (a) job attitudes, (b) job behaviors, and (c) well-being outcomes.

Hypothesis 2

HQT Ethically Acceptable will be beneficially related to (a) job attitudes, (b) job behaviors, and (c) well-being outcomes.

Hypothesis 3

The influence of HQT Ethically Unacceptable levels on outcomes will be mediated by HQT Ethically Acceptable levels.

Study 4 Method

Our final study looked to test the various HQT dimensions with data collected again from a Qualtrics survey panel on New Zealand employees. In study 4, we followed recommendations from Podsakoff et al. (2003) and used time-lagged data. Our HQT-Scale was collected at time 1 with outcome variables at time 2 (one month later). A total matched sample of 308 respondents was gathered, consisting of 51% male, with a median age of 38.8 years (SD = 12.8) and median tenure of 4.6 years (SD = 3.3). The sample was predominantly New Zealand European (61%) and educated (53% university degree), with 69% working in the private sector.

The focus of study 4 was to confirm the HQT-Scale and then test dimensions toward important work outcomes. These include work-life balance, which is an important well-being outcome itself (Haar et al., 2018b), as well as an important antecedent of other work outcomes (e.g., Haar et al., 2019). It is also linked to ethical leadership (Haar et al., 2019). As our job outcomes, we examined job satisfaction and work engagement due to their positive links to performance (Judge et al., 2001; Bakker et al., 2012). Finally, while organizational citizenship behaviors (OCBs) are an important outcome, they also contribute to organizational performance (Organ et al., 2005).

Measures

We used the HQT-Scale developed from study 1, assessing the 5 dimensions of HQT, coded 1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree, using the 20-item scale from study 3. Table 2 shows the factor score loading for study 4. All dimensions of the HQT-Scale in study 4 achieved adequate reliability (all α > 0.70). As with study 3, we created the 2-factor HQT higher-level factors: HQT Ethically Unacceptable which is the maltreatment and indifference levels combined (α = 0.87), and HQT Ethically Acceptable which is the justice, care, and development levels combined (α = 0.95).

Job Satisfaction was measured using three items by Judge et al. (2005), coded 1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree. A sample item includes “I find real enjoyment in my work.” This shortened construct has been well validated (e.g., Haar, 2013; Haar et al., 2014, 2019) and had good reliability (α = 0.85).

Work Engagement was measured using the 9-item short scale by Schaufeli et al. (2006), coded 1 = never, 5 = always. A sample item is “My job inspires me.” This scale has been well validated (e.g., Young et al., 2018) and had excellent reliability (α = 0.94).

OCBs were measured using four items from Lee and Allen’s (2002) OCB instrument (organizational dimension due to the HQT focus of the organization), coded 1 = never, 5 = always. This is based on the short 4-item version by Saks (2006). Questions followed the stem “Please indicate how often you engage in the following behaviors,” with a sample item “Show pride when representing the organization in public” (α = 0.75). This scale has been well validated, including in New Zealand (e.g., Haar & Brougham, 2020).

Work-life balance was measured using the 3-item scale by Haar (2013), coded 1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree. A sample item is “Nowadays, I seem to enjoy every part of my life equally well” and had very good reliability (α = 0.86). This construct has been well validated in New Zealand employees (e.g., Haar et al., 2018a, 2018b, 2019) and with international samples (e.g., Haar et al., 2014).

We controlled for Age (years) and Tenure (years) due to meta-analytic support for our outcomes (Ng & Feldman, 2010a, 2010b).

Analysis

Again, we used SEM to conduct a CFA to confirm the factor structure of the HQT-Scale. We then conducted hierarchical regression analysis (SPSS version 26) to determine the influence of the HQT levels on outcomes using the PROCESS 3.4 program (Hayes, 2018), which is especially useful for testing mediation effects. We conducted bootstrapping (5,000 times) with confidence intervals and indirect effects. In all models, Step 1 is the control variables (age and tenure), Step 2 is the HQT Ethically Unacceptable construct (Hypothesis 1), and Step 3 is the HQT Ethically Acceptable construct (Hypothesis 2). We separate the two HQT levels to test their potential effects aligned with Melé’s (2011, 2014, 2016) arguments that ethically acceptable treatment should triumph over ethically unacceptable treatment (Hypothesis 3).

Results

Our CFA results of the five dimensions of the HQT-Scale in study 4 resulted in good fit to the data: χ2(160) = 477.7 (p = 0.000), CFI = 0.93, RMSEA = 0.08, and SRMR = 0.05. Again, both alternative CFA models and a single higher-order model were consistently a poorer fit to the data (all p < 0.001). However, the 2-factor HQT higher-order model was also a good fit to the data: χ2(167) = 514.6 (p = 0.000), CFI = 0.92, RMSEA = 0.08, and SRMR = 0.06. Again, a multi-group CFA analysis was conducted to establish measurement invariance between respondents and income (using the three income bands from study three), and metric invariance was supported because the difference in RMSEA was again small (0.001) between the three groups, supporting their combination (see Haar et al., 2014 for more details).

Study 4 correlations are shown in Table 5.

Overall, the HQT Ethically Unacceptable construct was significantly and negatively correlated with the HQT Ethically Acceptable (r = -0.80, p < 0.01), and with all the work outcomes (all p < 0.01). Similarly, the HQT Ethically Acceptable construct was significantly and positively correlated with all work outcomes (all p < 0.01).

We now move beyond the correlations between our HTQ-Scale and apply these in regression models to our job and well-being outcomes.

Regression analyses for study 4 are shown in Fig. 2.

We find strong support for our theoretically driven hypotheses regarding the two groupings of HQT levels. Overall, the construct HQT Ethically Unacceptable was significantly and negatively related to job satisfaction (β = -0.41, LL = -0.56, UL = -0.34, p < 0.0001), work engagement (β = -0.31, LL = -0.49, UL = -0.24, p < 0.0001), OCBs (β = -0.19, LL = -0.30, UL = -0.08, p = 0.0010), and work-life balance (β = -0.46, LL = -0.61, UL = -0.39, p < 0.0001). Similarly, the construct HQT Ethically Acceptable was significantly and positively related to job satisfaction (β = 0.34, LL = 0.18, UL = 0.52, p < 0.0001), work engagement (β = 0.21, LL = 0.04, UL = 0.43, p = 0.0200), OCBs (β = 0.33, LL = 0.14, UL = 0.48, p = 0.0010), and work-life balance (β = 0.31, LL = 0.15, UL = 0.49, p < 0.0001). Combined, these findings provide support for Hypotheses 1a and 2a (job attitudes), Hypotheses 1b and 2b (job behaviors) and Hypotheses 1c and 2c (well-being). The analyses show that when the HQT Ethically Acceptable construct was included in the models, the detrimental influence from HQT Ethically Unacceptable dropped appreciably, toward job satisfaction (to β = -0.14, p = 0.095), work engagement (β = -0.14, p = 0.116), OCBs (β = 0.07, p = 0.454), and work-life balance (to β = -0.21, p = 0.014).

Examining the indirect effects, shows that HQT Ethically Unacceptable remains significantly related to job satisfaction (β = -0.27, LL = -0.41, UL = -0.13, p < 0.0001), work engagement (β = -0.17, LL = -0.30, UL = -0.03, p = 0.0076), OCBs (β = -0.26, LL = -0.41, UL = -0.13, p = 0.0002), and work-life balance (β = -0.25, LL = -0.38, UL = -0.11, p = 0.0002). In summary, the addition of HQT Ethically Acceptable levels of the HQT-Scale appears to fully mediate the influence of HQT Ethically Unacceptable levels toward all outcomes, albeit only partial mediation toward work-life balance, supporting Hypothesis 3. However, the significant indirect effect shows that HQT Ethically Unacceptable shows it is still important. Overall, the models accounted for robust amounts of variance toward job satisfaction and work-life balance (25% variance), and more modest toward engagement (16%) and small toward OCBs (8%).

Finally, ANOVA analysis was conducted to explore HQT Ethically Acceptable and Ethically Unacceptable by income in study four. Again, using the SNK test of difference we find no significant difference toward HQT Ethically Unacceptable (F = 1.521, p = 0.220) but we do toward HQT Ethically Acceptable (F = 4.272, p = 0.015). Hence, the scores for HQT Ethically Unacceptable did not differ by the income earnt by respondents. But, toward HQT Ethically Acceptable, we find the low-income group (up to $55,000) reported the lowest score (M = 3.22), which was significantly lower than the middle-income group ($55,001-$100,000) on M = 3.47, which was also significantly lower than the highest-income group ($100,001 or greater) on M = 3.56.

Discussion

Overall, the present study sought to achieve three goals: (1) develop an HQT-Scale, (2) provide cross-cultural validity, and (3) establish the links between our HQT-Scale and employee job and well-being outcomes. Our first two goals were well supported, with our development and validation across four studies, with the first study basing our original items for the HQT-Scale on the qualitative work of Ogunyemi and Melé (2014). This was then developed with several academic experts and finally trialed on a small sample of MBA students to establish the 25-item HQT-Scale. Our second study then tested this on a sample of managers from Nigeria and the analyses showed the 25 items fit the theoretically derived HQT well (Melé, 2003, 2009, 2011, 2014, 2016). We also confirmed that a higher-order construct was not a good fit for the data, but a two-factor higher order was a solid conceptualization of the HQT-Scale, and with this, generated two factors: (1) HQT Ethically Unacceptable, which captured the low HQT dimensions of maltreatment and indifference, and (2) HQT Ethically Acceptable, captured the HQT levels of justice, care, and development. Importantly, this provides researchers with a pair of theoretically based but empirically derived constructs for empirically testing the HQT-Scale.

Our third study conducted tests of the construct and the findings from study 2 were replicated. This is important because we shifted the focus from Nigeria to New Zealand, and the construct held in a wider sample of employees (not just managers as per study 2) and in a different cultural context. This supported our second goal of cross-cultural validation. This study also conducted tests of convergent and discriminant validity, and this again supported the HQT-Scale. We also refined the scales and removed the least popular item from each HQT dimension originally tested in study 2, and ultimately settled on a 20-item construct. Ultimately, study 3 gives us confidence that the two-factor HQT-Scale is robust and unique. Finally, in study 4 we tested hypotheses around the influence of the HQT-Scale on job attitudes, behaviors, and well-being supporting our third goal.

Theoretically, the lower levels of HQT (maltreatment and indifference) are expected to be detrimental to employees (Melé, 2003, 2009, 2011, 2014, 2016). Under SET, we expect employees to reciprocate with poorer job attitudes, behaviors, and well-being when they feel their organization provides such a poor organizational climate typified by maltreatment and indifference toward employees. Our findings from studies 2–4 showed respondents were much less likely to rate their organizations as behaving in such an inhumane way, but those who rated their firms more on the HQT Ethically Unacceptable factor (study 4), were found to report negative effects toward job attitudes, job behaviors, and well-being. These findings align well with the theoretical approach of HQT (Melé, 2014). Alternatively, we argued that under SET, firms that provide a strong climate of justice, care, and development (HQT Ethically Acceptable) create a felt obligation on employees to respond with more positive attitudes and behaviors, and this was also supported. Similarly, given the links between SET and well-being whereby employees understand their employer can step in to aid them when needed, we also found support for positive effects on well-being. Again, these findings align both with the theories around HQT (Melé, 2014) and social exchange (Blau, 1964). Our further analysis also showed these effects hold across employees on differing income levels, indicating that HM and HQT are universally important whether workers are on low, medium, or higher wages. This further supports Melé’s argument around the importance of HM for all human beings.

Our study 4 findings also provided interesting effects around the HQT factors. While HQT Ethically Acceptable was found to typically mediate the effects of HQT Ethically Unacceptable—fully on job attitudes and behaviors, but only partially toward well-being—the additional indirect effects analysis showed that HQT Ethically Unacceptable maintained a significant and strong indirect effect. This has important implications for HM scholars. Melé (2003) champions the importance of HM and these findings remind us that even in the context of good humanistic support within organizations (high HQT levels of justice, care, and development) that the inhumane approach to people (high HQT levels of maltreatment and indifference) can still play an important and detrimental role. We suggest this shows that engaging in more of the positive forms of HQT (Ethically Acceptable) without addressing the negative forms of HQT (Ethically Unacceptable) is likely to have adverse effects and ultimately be destructive for organizations. Thus, organizations need to acknowledge that building an ethically acceptable climate means addressing and dismantling the ethically unacceptable behaviors within an organization at the same time. We address this more fully below.

Implications

Our results highlight that, aligned theoretically with HQT (Melé, 2014) and HM (Melé, 2003) more generally, organizations need to focus on building a climate that embraces the higher HQT levels of justice, care, and development. Hence, dealing openly and transparently with issues around performance and complaints is important—being fair is fundamentally vital for organizations seeking to develop HQT in their workplaces. Similarly, encouraging managers to care about their workers and provide support for legitimate goals will strengthen a firm’s HQT focus. Finally, focusing on character and human flourishing when considering promotions, driving ethical decision-making, and practicing moral values are all important ways an organization shows it is strongly focused on HM.

However, we also showed above that it is important for firms to address the lower level HQT factors of maltreatment and indifference. Caring, supporting, and nurturing employees may align with the higher HQT levels. Still, managers and senior leaders must be aware that they have to address bullying, health and safety issues, and employee voice and decision-making participation. Indifference to these aspects may undermine higher-level HQT actions by an organization, and thus leaders need to examine their organization across a range of actions, whereby they minimize and address negative HQT actions and develop and champion positive HQT actions.

These results also have implications for researchers. While our paper provides a framework for empirically testing HQT, there is clearly a need for greater empirical support. We encourage researchers to test our HQT-Scale across several settings to improve the generalizability of our scale. Further, more exploration of employee outcomes is encouraged, especially other factors like turnover intentions and counterproductive work behaviors. Similarly, our study 4 included only one well-being outcome (work-life balance), and researchers should seek to test other constructs like anxiety and depression, life satisfaction, and happiness. This would strengthen the indication toward key well-being outcomes. Further, researchers might explore the HQT-Scale at the team level to explore performance effects, and indeed, extending to the firm-level might show that firms with higher HQT may outperform competitors.

Limitations

We conducted four studies to build and test our HQT-Scale and this does provide strong confidence in our findings. Further, we used samples from Nigeria (studies 1–2) and New Zealand (studies 3–4) to provide some cross-cultural validation. Further, we used large and robust samples of employees and included time-lagged data in study 4 to aid confidence in our analyses (Podsakoff et al., 2003). Some limitations, however, include the use of more constructs for construct validity tests in study 3 and more employee behaviors and well-being constructs in study 4. Ultimately, we were parsimonious in our focus to provide greater validation across studies than simply within studies. One limitation was not having secondary data such as partner-rated well-being or supervisor-rated performance. Such an approach was beyond the focus of our studies.

Conclusion

Overall, the present study developed and tested a construct based on the HQT approach and this resulted in the 20-item HQT-Scale. Our use of multiple studies provided growing evidence and support for the construct, especially the two-factor approach around acceptable and unacceptable ethical behavior within an organization. Not only did our analysis of job attitudes, behaviors, and well-being provide alignment with the theoretical arguments around HQT, but it also highlighted the indirect effect of unacceptable ethics and how these can continue to undermine and detract from the ethical culture of an organization. This provides useful guidance for how organizations must seek to not only develop and grow ethical behaviors within but importantly, seek out and address unethical behaviors as these can continue to play a detrimental role.

References

Ambrose, M., Seabright, M., & Schminke, M. (2002). Sabotage in the workplace: The role of organizational injustice. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 89, 947–965.

Andersson, L. M., & Pearson, C. (1999). Tit for tat: The spiralling effect of incivility in the workplace. Academy of Management Review, 24, 452–472.

Aritzeta, A., Swailes, S., & Senior, B. (2007). Belbin’s team role model: Development, validity and applications for team building. Journal of Management Studies, 44(1), 96–118.

Arjoon, S. (2000). Virtue theory as a dynamic theory of business. Journal of Business Ethics, 28, 159–178.

Arnaud, S., & Wasieleski, D. (2014). Corporate humanistic responsibility: Social performance through managerial discretion of the HRM. Journal of Business Ethics, 120(3), 313–334. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-013-1652-z.

Arnold, D. G. (2010). Transnational corporations and the duty to respect basic human rights. Business Ethics Quarterly, 20(3), 371–399.

Bakker, A. B., Tims, M., & Derks, D. (2012). Proactive personality and job performance: The role of job crafting and work engagement. Human Relations, 65(10), 1359–1378.

Bedi, A., Alpaslan, C. M., & Green, S. (2016). A meta-analytic review of ethical leadership outcomes and moderators. Journal of Business Ethics, 139(3), 517–536.

Blau, P. (1964). Exchange and power in social life. Wiley.

Bolton, S. C. (2010). Being human: Dignity of labor as the foundation for the spirit-work connection. Journal of Management, Spirituality & Religion, 7(2), 157–172.

Brown, K. W., & Ryan, R. M. (2003). The benefits of being present: Mindfulness and its role in psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84, 822–848.

Brown, M., Treviño, L., & Harrison, D. A. (2005). Ethical leadership: A social learning perspective for construct development and testing. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 97(2), 117–134.

Caldwell, C. (2011). Duties owed to organizational citizens—Ethical insights for today’s leader. Journal of Business Ethics, 102, 343–356.

Campbell, D. T., & Fiske, D. W. (1959). Convergent and discriminant validation by the multitrait-multimethod matrix. Psychological Bulletin, 56(2), 81–105.

Cortina, L. M., Magley, V. J., Williams, J. H., & Langhout, R. D. (2001). Incivility in the workplace: Incidence and impact. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 6(1), 64–80.

DeVellis, R. F. (2003). Scale development: Theory and applications. Sage.

Donovan, M. A., Drasgow, F., & Munson, L. J. (1998). The perceptions of fair interpersonal treatment scale: Development and validation of a measure of interpersonal treatment in the workplace. Journal of Applied Psychology, 83(5), 683–692.

Duchon, D., & Drake, B. (2008). Organizational narcissism and virtuous behavior. Journal of Business Ethics, 85(3), 301–308.

Duckworth, A. L., & Kern, M. L. (2011). A meta-analysis of the convergent validity of self- control measures. Journal of Research in Personality, 45(3), 259–268.

Eisenberger, R., Huntington, R., Hutchison, S., & Sowa, D. (1986). Perceived organizational support. Journal of Applied Psychology, 71(3), 500–507.

Fiske, D. W. (1971). Measuring the concepts of personality. Aldline Publishing Co.

Flynn, G. (2008). The virtuous manager: A vision for leadership in business. In G. Flynn (Ed.), Leadership and Business Ethics (pp. 39–56). Springer.

Foody, W. (1998). An empirical evaluation of in-depth probes used to pretest survey questions. Sociological Methods and Research, 27(1), 103–133.

French, W., & Weis, A. (2000). An ethics of care or an ethics of justice. In J. Sójka & J. Wempe (Eds.), Business challenging business ethics: New instruments for coping with diversity in international business (pp. 125–136). Springer.

Friedman, M. S. (1970). The social responsibility of business is to increase its profits. In W. M. Hoffman & J. M. Moore (Eds.), Business ethics: Readings and cases in corporate morality (2nd ed., pp. 153–156). McGraw-Hill.

Gouldner, A. (1960). The norm of reciprocity. American Sociological Review, 25, 161–178.

Grant, K. (2008). Who are the lepers in our organizations? A case for compassionate leadership. Business Renaissance Quarterly, 3(2), 75–91.

Grawitch, M., Gottschalk, M., & Munz, D. (2006). The path to a healthy workplace: A critical review linking healthy workplace practices, employee well-being, and organizational improvements. Consulting Psychology Journal: Practice Research, 58(3), 129–148.

Grojean, M. W., Resick, C. J., Dickson, M. W., & Smith, D. B. (2004). Leaders, values, and organizational climate: Examining leadership strategies for establishing an organizational climate regarding ethics. Journal of Business Ethics, 55(3), 223–241.

Gross, J. A. (2010). A shameful business: The case for human rights in the American workplace. Cornell University Press.

Haar, J. M. (2006). Challenge and hindrance stressors in New Zealand: Exploring social exchange theory outcomes. International Journal of Human Resource Management, 17(11), 1942–1950.

Haar, J. M. (2013). Testing a new measure of work-life balance: A study of parent and non- parent employees from New Zealand. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 24(17), 3305–3324.

Haar, J., & Brougham, D. (2020). Work antecedents and consequences of work-life balance: A two sample study within New Zealand. The International Journal of Human Resource Management. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2020.1751238

Haar, J., Carr, S., Parker, J., Arrowsmith, J., Hodgetts, D., & Alefaio-Tugia, S. (2018a). Escape from working poverty: Steps toward sustainable livelihood. Sustainability, 10(11), 4144.

Haar, J., Roche, M., & Brougham, D. (2019). Indigenous insights into ethical leadership: A study of Māori leaders. Journal of Business Ethics, 160(3), 621–640.

Haar, J., Roche, M. A., & ten Brummelhuis, L. (2018b). A daily diary study of work-life balance in managers: Utilizing a daily process model. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 29(18), 2659–2681.

Haar, J. M., Russo, M., Sune, A., & Ollier-Malaterre, A. (2014). Outcomes of work-life balance on job satisfaction, life satisfaction and mental health: A study across seven cultures. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 85(3), 361–373.

Haar, J., & Spell, C. (2004). Program knowledge and value of work-family practices and organizational commitment. International Journal of Human Resource Management, 15(6), 1040–1055.

Hayes, A. F. (2018). Partial, conditional, and moderated mediation: Quantification, inference, and interpretation. Communication Monographs, 85(1), 4–40.

Höfling, V., Moosbrugger, H., Schermelleh-Engel, K., & Heidenreich, T. (2011). Mindfulness or mindlessness? European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 27(1), 59–64.

Hu, L. T., & Bentler, P. M. (1998). Fit indices in covariance structure modeling: Sensitivity to underparameterized model misspecification. Psychological Methods, 3(4), 424–453.

Ituma, A., Simpson, R., Ovadje, F., Cornelius, N., & Mordi, C. (2011). Four ‘domains’ of career success: How managers in Nigeria evaluate career outcomes. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 22(17), 3638–3660.

Jaramillo, F., Grisaffe, D. B., Chonko, L. B., & Roberts, J. A. (2009). Examining the impact of servant leadership on salesperson’s turnover intention. Journal of Personal Selling and Sales Management, 29(4), 351–365.

Judge, T. A., Bono, J. E., Erez, A., & Locke, E. A. (2005). Core self-evaluations and job and life satisfaction: The role of self-concordance and goal attainment. Journal of Applied Psychology, 90(2), 257–268.

Judge, T. A., Thoresen, C. J., Bono, J. E., & Patton, G. K. (2001). The job satisfaction–job performance relationship: A qualitative and quantitative review. Psychological Bulletin, 127(3), 376–407.

Kang, J., & Hustvedt, G. (2014). Building trust between consumers and corporations: The role of consumer perceptions of transparency and social responsibility. Journal of Business Ethics, 125(2), 253–265.

Keashly, L., Trott, V., & MacLean, L. M. (1994). Abusive behavior in the workplace: A preliminary investigation, violence, and victims. Violence and Victims, 9(4), 341–357.

Kurtessis, J. N., Eisenberger, R., Ford, M. T., Buffardi, L. C., Stewart, K. A., & Adis, C. S. (2017). Perceived organizational support: A meta-analytic evaluation of organizational support theory. Journal of Management, 43(6), 1854–1884.

Lee, K., & Allen, N. J. (2002). Organizational citizenship behavior and workplace deviance: The role of affect and cognitions. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87(1), 131–142.

Liden, R. C., Wayne, S. J., Zhao, H., & Henderson, D. (2008). Servant leadership: Development of a multidimensional measure and multi-level assessment. The Leadership Quarterly, 19(2), 161–177.

Lips-Wiersma, M., & Nilakant, V. (2008). Practical compassion: Toward a critical spiritual foundation for corporate responsibility. In J. Biberman & L. Tischler (Eds.), Spirituality in business: Theory, practice, and future directions (pp. 51–72). Palgrave Macmillan.

Matsunaga, M. (2010). Individual dispositions and interpersonal concerns underlying bullied victims’ self-disclosure in Japan and the US. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 27(8), 1124–1148.

Matthiesen, S. B., & Einarsen, S. (2010). Bullying in the workplace: Definition, prevalence, antecedents, and consequences. International Journal of Organization Theory & Behavior, 13(2), 202–248.

Melé, D. (2003). The challenge of humanistic management. Journal of Business Ethics, 44(1), 77–88.

Melé, D. (2009). Editorial introduction: Towards a more humanistic management. Journal of Business Ethics, 88(3), 413–416.

Melé, D. (2011). Management ethics: Placing ethics at the core of good management. Palgrave Macmillan.

Melé, D. (2014). Human quality treatment: Five organizational levels. Journal of Business Ethics, 120(4), 457–471.

Melé, D. (2016). Understanding humanistic management. Humanistic Management Journal, 1(1), 33–55.

Netemeyer, R. G., Bearden, W. O., & Sharma, S. (2003). Scaling procedures: Issues and applications. Sage.

Ng, T. W., & Feldman, D. C. (2010a). Organizational tenure and job performance. Journal of Management, 36(5), 1220–1250.

Ng, T. W., & Feldman, D. C. (2010b). The relationships of age with job attitudes: A meta-analysis. Personnel Psychology, 63(3), 677–718.

Ogunyemi, A. O., & Melé, D. (2014). Organizational levels of human quality treatment: Evidence from four SMEs. Symposium, Academy of Management Conference, Philadelphia, USA,. https://doi.org/10.5465/AMBPP.2014.14173abstract

Okafor, E. E., Fagbemi, A. O., & Hassan, A. R. (2011). Barriers to women leadership and managerial aspirations in Lagos, Nigeria: An empirical analysis. African Journal of Business Management, 5(16), 6717–6726.

Okpara, J. O., & Wynn, P. (2008). The impact of ethical climate on job satisfaction, and commitment in Nigeria: Implications for management development. Journal of Management Development, 27(9), 935–950.

Organ, D. W., Podsakoff, P. M., & MacKenzie, S. B. (2005). Organizational citizenship behavior: Its nature, antecedents, and consequences. Sage.

Parris, D. L., & Peachey, J. W. (2013). A systematic literature review of servant leadership theory in organizational contexts. Journal of Business Ethics, 113, 377–393.

Parzefall, M., & Salin, D. M. (2010). Perceptions of and reactions to workplace bullying: A social exchange perspective. Human Relations, 63(6), 761–780.

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–903.

Saks, A. M. (2006). Antecedents and consequences of employee engagement. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 21(7), 600–619.

Schaufeli, W. B., Bakker, A. B., & Salanova, M. (2006). The measurement of work engagement with a short questionnaire: A cross-national study. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 66(4), 701–716.

Schneider, S. C. (1999). Human and inhuman resource management: Sense and nonsense. Organization, 6(2), 277–284.

Schreiber, J. B., Nora, A., Stage, F. K., Barlow, E. A., & King, J. (2006). Reporting structural equation modeling and confirmatory factor analysis results: A review. The Journal of Educational Research, 99(6), 323–338.

Shanahan, K. J., & Hyman, M. R. (2003). The development of a virtue ethics scale. Journal of Business Ethics, 42, 197–208.

Sison, A., & Fontrodona, J. (2012). The common good of the firm in the Aristotelian-Thomistic tradition. Business Ethics Quarterly, 22(2), 211–246.

Spitzeck, H. (2011). An integrated model of humanistic management. Journal of Business Ethics, 99(1), 51–62.

Stahl, G. K., & De Luque, M. S. (2014). Antecedents of responsible leader behavior: A research synthesis, conceptual framework, and agenda for future research. Academy of Management Perspectives, 28(3), 235–254.

Sternberg, E. (1995). Just business: Business ethics in action. Warner Books.

Trevino, L. K., & Youngblood, S. A. (1990). Bad apples in bad barrels: A causal analysis of ethical decision-making behavior. Journal of Applied Psychology, 75(4), 378–385.

Van De Voorde, K., Paauwe, J., & Van Veldhoven, M. I. (2012). Employee well-being and the HRM–organizational performance relationship: A review of quantitative studies. International Journal of Management Reviews, 14(4), 391–407.

Vogel, D. J. (2005). Is there a market for virtue? The business case for corporate social responsibility. California Management Review, 47(4), 20–45.

Wahlqvist, P., Carlsson, J., Stålhammar, N. O., & Wiklund, I. (2002). Validity of a work productivity and activity impairment questionnaire for patients with symptoms of gastro-esophageal reflux disease (WPAI-GERD)—Results from a cross-sectional study. Value in Health, 5(2), 106–113.

Wang, Q., Junsheng, D., & Shenghua, J. (2016). A meta-analytic review of corporate social responsibility and corporate financial performance: The moderating effect of contextual factors. Business & Society, 55(8), 1083–1121.

Weaver, G. R. (2006). Virtue in organizations: Moral identity as a foundation for moral agency. Organization Studies, 27(3), 341–368.

Williams, L. J., Vandenberg, R. J., & Edwards, J. R. (2009). Structural equation modeling in management research: A guide for improved analysis. Academy of Management Annals, 3(1), 543–604.

Young, H. R., Glerum, D. R., Wang, W., & Joseph, D. L. (2018). Who are the most engaged at work? A meta-analysis of personality and employee engagement. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 39(10), 1330–1346.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions. The authors did not receive support from any organization for the submitted work. No funding was received to assist with the preparation of this manuscript. No funding was received for conducting this study. No funds, grants, or other support was received. The authors have no relevant financial interests to disclose.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

Author A is a Guest Editor for the Journal of Business Ethics Special Issue on “Ethics and the Future of Meaningful Work.” Authors B, C and D have no conflicts of interest to declare that are relevant to the content of this article. All authors certify that they have no affiliations with or involvement in any organization or entity with any financial interest or non-financial interest in the subject matter or materials discussed in this manuscript. The authors have no financial or proprietary interests in any material discussed in this article.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

McGhee, P., Haar, J., Ogunyemi, K. et al. Developing, Validating, and Applying a Measure of Human Quality Treatment. J Bus Ethics 185, 647–663 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-022-05213-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-022-05213-y