Abstract

In the current literature, institutional adoption of Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) governance standards is mainly understood in a binary sense (adoption versus no adoption), and existing research has hitherto focused on inducements as well as on barriers of related organizational change. However, little is known about often invisible internal adoption patterns relating to institutional entrepreneurship in the field of CSR. At the same time, additional information about these processes is relevant in order to systematically assess the outcomes of institutional entrepreneurship and to differentiate between substantive versus symbolic implementation. In this paper, we contribute a comparative intraorganizational differentiation of institutional adoption processes in the field of CSR, and we distinguish between broad and narrow organizational institutional adoption across different management functions relating to institutions of a similar type. Our study is based on a quantitative survey among members of the United Nations Global Compact Network Germany, as well as on qualitative interviews. We analyze different institutional adoption patterns and derive ten theoretical predictors of diverse institutional adoption choices and thereby inform the literatures on institutional entrepreneurship, CSR governance, and Multi-Stakeholder Initiatives. Besides our theoretical contributions, our findings serve as a source of information for practitioners engaged in CSR governance as they provide new insights into the managerial perception and assessment of different CSR standards and initiatives.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In the field of Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR), diverse groups and constellations of institutional entrepreneurs, including governmental bodies, private organizations, and Multi-Stakeholder Initiatives (MSIs), develop standards and guidance on how companies can set up their operations in a more ecologically and socially sustainable way (Fransen & Kolk, 2007; Rasche & Gilbert, 2012; Roloff, 2008; Utting, 2002). This activity is frequently referred to in the literature as CSR governance, which comprises actors, processes, and instruments that are involved when trying to address social or ecological issues within the field of CSR (Jastram, 2016).

Institutional adoption of CSR governance standards is typically voluntary, and research has identified a variety of inducements as well as barriers of related organizational change (Aguilera et al., 2007; Christmann & Taylor, 2006; Fransen & Kolk, 2007; Rasche et al., 2013; Utting, 2002; Wijen, 2014). For instance, existing studies show that complexity, practice multiplicity, and behavioral invisibility inhibit compliance, whereas clear rules, incentives, and the provision of best practice examples have enforcing and stimulating effects (Baron & Lyon, 2012; Christmann & Taylor, 2006; Greenwood et al., 2011; Jiang & Bansal, 2003; King et al., 2012; Pache & Santos, 2010; Terlaak, 2007).

In recent research, scholars have often been focusing on capturing and analyzing existing institutions in the field of CSR by describing the variety of institutional designs, actor constellations, enforcement mechanisms, and by discussing institutional legitimacy, output, outcome, and impact (e.g., De Bakker et al., 2019; Mückenberger & Jastram, 2010; Jastram & Klingenberg, 2018; Djelic & Den Hond, 2014; Fransen et al., 2019; Cashore et al., 2020).

Yet, while we know much about the general multiplicity of existing CSR standards and initiatives, there is considerably less literature on how and where in the organization institutional adoption takes place.

If firms refer to MSIs like the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) or the United Nations Global Compact (UN Global Compact or UN GC) in CSR reports or on their webpages, institutional adoption might have taken place, but few additional details about the organizational implementation processes are known. Accordingly, existing studies often discuss whether or not specific standards are applied by organizations as a whole (Battilana et al., 2009; Baumann-Pauly & Scherer, 2013; Brown et al., 2018; Chandler & Hwang, 2015; Wijen, 2014) while more specified knowledge concerning intraorganizational adoption processes and places is largely missing. At the same time, more differentiated information about organizational adoption patterns is relevant in order to systematically assess governance outcomes and to distinguish between substantive versus symbolic implementation (Christmann & Taylor, 2006). If, for instance, a CSR standard is only employed as a reference in corporate communications but not part of employee trainings or supply chain management, the institutional outcome is different compared to a standard that has been integrated throughout the organization and across managerial functions.

In this context, the literature has demonstrated that different strengths of policy-practice coupling relate to different ultimate impacts of CSR for beneficiaries such as workers in international supply chains or local communities (De Bakker et al., 2019; Jastram & Klingenberg, 2018; Rasche, 2009; Wijen, 2014). In other words, the likelihood of improving the social and environmental conditions of global economic production is higher the more systematic and integrative CSR standards are applied across managerial functions and throughout the value chain (Siltaloppi et al., 2020; Yuan et al., 2011). We, thus, argue that more detailed knowledge about intraorganizational implementation processes is needed to address current research gaps and to gain insights for the further development of institutional entrepreneurship theory.

Against this background, the research questions we aim to address in this paper are: In which organizational areas and management functions do firms adopt CSR standards? What explains different institutional adoption patterns relating to similar institutions in the field of CSR?

Our empirical analysis focuses on corporate institutional adoption choices to understand how CSR standards defined by external institutional entrepreneurs are adopted and implemented within organizations. These intraorganizational outcomes of institutional entrepreneurship are different from potential ultimate impacts of CSR (Clark et al., 2004; Jastram & Klingenberg, 2018) because, while organizational adoption is the first important step towards impact, it can nonetheless be ineffective if corporate programs and strategies are insufficient in addressing grand challenges (Ferraro et al., 2015) or if they are applied only symbolically (Christmann & Taylor, 2006). This phenomenon is also referred to in the literature as the decoupling of means and ends (Bromley & Powell, 2012; Wijen, 2014).

While ultimate impacts in the field of CSR are influenced by a multitude of factors, including the local institutional context and sociostructure (Jastram & Schneider, 2018a; Chowdhury, 2021), the initial effective implementation of CSR principles within organizations is essential for creating change. This study, thus, aims to contribute to a better understanding of intraorganizational institutional adoption patterns related to external institutional entrepreneurship. We will address these questions through an explorative, comparative research approach involving a quantitative survey among members of the UN GC Network Germany as well as qualitative interviews with CSR managers. To the best of our knowledge, a comparative analysis of institutional outcomes and adaption patterns in different organizational functions has not been conducted before although the results are relevant from a theoretical as well as practical perspective.

Our study contributes to institutional theory, especially to the institutional entrepreneurship literature (e.g., Battilana et al., 2009; DiMaggio, 1988; Fligstein, 1997; Garud et al., 2007; Hardy & Maguire, 2013; Holm, 1995; Seo & Creed, 2002), by providing a comparative intraorganizational analysis of institutional adoption patterns in the field of CSR. We differentiate institutional entrepreneurship outcomes by distinguishing between broad and narrow organizational institutional adoption across different management functions relating to institutions of a similar type. We further show that institutional adoption is not binary, but that policy and practice can interact in a diverse manner. Moreover, we discuss reasons for different forms of institutional adoption and develop predictors on the likelihood of a broad institutional implementation of CSR principles across diverse management functions. Our theoretical differentiation and predictors are relevant in order to understand and to identify limited corporate institutional adoption, which can be an indicator of policy-practice decoupling (Bromley & Powell, 2012; De Bakker et al., 2019; DiMaggio, 1988; Wijen, 2014) and may lead to a limited impact of institutional entrepreneurship for beneficiaries.

Besides these theoretical contributions, our findings serve as a source of information for governance actors because they provide new insights into the managerial perception and assessment of different CSR governance initiatives. Practitioners will understand how and where in the organization CSR standards are applied and can match these findings with their own governance targets. Moreover, they may derive implications for adjustments of their governance approaches if corporate institutional adoption deviates from intended governance outcomes.

The following sections will provide a discussion of the state of the literature on institutional entrepreneurship and organizational adoption. Next, we present our methodology as well as the results of our empirical study, and derive ten institutional adoption predictors. We finish the article with a discussion, conclusion and research outlook.

State of Research

Institutional theory argues that institutions shape patterns of action and organization (Aldrich & Fiol, 1994; Battilana, 2006; DiMaggio & Powell, 1983; Meyer & Rowan, 1977). Institutions can be defined as “rules, norms, and beliefs that describe reality for the organization” (Hoffman, 1999, p. 351). They can be formed by institutional entrepreneurs, who, “whether individuals or organizations, are agents who initiate, and actively participate in the implementation of changes that diverge from existing institutions, independent of whether the initial intent was to change the institutional environment and whether the changes were successfully implemented” (Battilana et al., 2009, p. 72; see also: Shane & Venkataraman, 2000; Battilana, 2007; Hardy & Maguire, 2013; Lawrence et al., 2002; DiMaggio, 1988; Garud et al., 2007; Greenwood & Hinings, 1996; Lounsbury & Crumley, 2007). In this context, the paradox of embedded agency (DiMaggio & Powell, 1983; Garud et al., 2007; Holm, 1995; Seo & Creed, 2002) describes that institutional entrepreneurs are part of the institutional environment that forms them and simultaneously cause changes to those institutions (Etzion & Ferraro, 2010; Fligstein, 1997; Levy & Scully, 2007; Lounsbury & Crumley, 2007; Olsen & Boxenbaum, 2009).

In the field of Corporate Social Responsibility, individual as well as collective actors are engaging in governance and institutional entrepreneurship in order to drive organizational and social change towards a more sustainable future (Mückenberger & Jastram, 2010; Rasche, 2012). These institutional entrepreneurs develop norms and standards based on their notion of responsible business and/or on existing fundamental norms such as human rights. In addition, they engage in related dissemination, implementation, and enforcement activities (Jastram & Schneider, 2018a; Jastram & Klingenberg, 2018; Alvord et al., 2004).

This extensive engagement of institutional entrepreneurs has led to a multiplicity of new standards and initiatives in the field of CSR (Djelic & Den Hond, 2014; Wijen, 2014) as well as corresponding scientific overview studies and typologies. In this context, authors cluster standards and initiatives based on, for instance, targeted actors, industry-specificity, geographic scope, degree of voluntariness, type of interaction, varying logics, or interaction types between private and public organizations (Auld et al., 2015; Cashore et al., 2020; Fransen et al., 2019; Ponte et al., 2020). In addition, De Bakker et al. (2019) differentiate initiatives based on input, institutionalization, and impact. Overall, the literature provides many comparative analyses of institutions in the field of CSR, however, analyses of organizational adoption patterns are largely missing.

If studies analyze institutional implementation, the focus has often been on understanding reasons for voluntary adoption, and research has found that corporate actors comply with externally developed or promoted CSR standards or other institutions if they are morally, instrumentally, and/or relationally motivated. Morally driven firms adopt CSR norms because they want to act ethically (Bansal & Roth, 2000; Cropanzano et al., 2003; Gottschalg & Zollo, 2007). Instrumentally driven organizations see a benefit or a competitive advantage in institutional adoption, while firms under pressure are relationally motivated (Aguilera et al., 2007).

Influenced by the institutional environment, CSR can be conducted implicitly or explicitly (Matten & Moon, 2008), while institutions such as the UN GC can lead to both forms of institutional adoption (Brown et al., 2018). Hence, institutional entrepreneurship can have various effects which are not always considered as positive outcomes (Banerjee, 2008; Garud et al., 2002; Khan et al., 2007). An issue that can occur in this context is symbolic adoption, which describes the corporate application of institutions mainly for reputational or lobbying reasons without corresponding systematic organizational change (Christmann & Taylor, 2006). This phenomenon has been referred to as ‘decoupling’ (Bromley & Powell, 2012), and the corresponding literature demonstrates that institutional adoption does not necessarily equal substantial problem-solving.

In this context, authors distinguish two types of decoupling: ‘policy-practice decoupling’, the non-compliance of adopters (practice) with an institution (policy)—also referred to as symbolic adoption or greenwashing—and ‘means-ends decoupling’, which assumes compliance with the institution (means) but does not lead to the targeted impacts (ends) (DiMaggio, 1988, p. 5; Bromley & Powell, 2012; Meyer & Rowan, 1977).

In other words, adopting principles of an MSI does not guarantee related ultimate impacts such as increasing wages, the elimination of child labor, or fair victim compensation (Banerjee, 2008; Chowdhury, 2017, 2021). For instance, companies such as El Corte Inglès, Inditex, or Carrefour were members of the United Nations Global Compact before the Rana Plaza collapse in 2013, and yet they have been linked with the disaster indicating that institutional decoupling had taken place (Clean Clothes Campaign, 2021; United Nations Global Compact, 2021). In this context, Wijen (2014) explains that symbolic adoption is often related to the high opacity of the CSR field, which is characterized by difficulties to comprehend and to measure organizational practices and their impact. This leads to uncertainty and ambiguity (Jiang & Bansal, 2003; Wijen, 2014) due to high degrees of interdependency and causal complexity regarding impacts (Greenwood et al., 2011; Levy & Lichtenstein, 2012).

Different geographical, cultural, social, political, or economic influences lead to a variety of CSR standards and practice as well as behavioral invisibility (Pache & Santos, 2010; Jiang & Bansal, 2003; Djelic & Den Hond, 2014), non-transparency (Schleifer et al., 2019), and low levels of traceability (Chowdhury, 2019). In this regard, Terlaak (2007) argues that increased precision and explicitness among institutions lead to increased institutional adoption and compliance. Furthermore, incentives such as labels or certificates — which may correspond with the ability of firms to reach new customer groups, achieve a reputational benefit, or generate a price premium — can foster standard adoption (Christmann & Taylor, 2006; De Bakker et al., 2019; Perez-Aleman & Sandilands, 2008; Sine et al., 2007). Moreover, monitoring and negative incentives such as sanctions lead to increased compliance (Dietz et al., 2003). Educational training and the provision of best practice examples further support implementation and adoption. Also, institutional adoption can be enhanced via the development of niche institutions tailored to specific business fields and contexts. Such niche institutions might complement more general ones and make them more specific and achievable for adopters (Timmermans & Epstein, 2010; Young, 2012).

Other authors argue that institutional adoption can best be supported by endorsing a systemic mindset (Sterman, 2000), supporting organizations to internalize the institution so that they self-define and monitor their impact targets and implementation strategies (Berger & Luckmann, 1966; Tyler & Lind, 1992; Young, 2012). In this scenario, adopters embed the institution’s goals into their own and create more innovative solutions due to lower external pressure and demands (Gottschalg & Zollo, 2007). Finally, collaborative approaches to impact creation involving local actors such as NGOs, unions, and/or governmental organizations are regarded to increase the impact of CSR governance (Jastram & Schneider, 2018a, 2018b).

It becomes clear that the existing literature provides knowledge on motives, barriers, and enablers of institutional adoption. Yet, especially in highly opaque and complex fields, such as the one of CSR, we lack precise, comparative information about where in the organization institutional adoption takes place and how institutional diversity influences adoption patterns.

While it should be stressed again that institutional adoption must not be equalized with institutional impact, adoption is the first crucial step towards substantial problem-solving, which could not be reached if organizations did not implement CSR policies in the first place. We, thus, focus our empirical study on organizational adoption patterns as a relevant first stage towards impact creation and introduce our methodological approach in the next section.

Methodology

To comparatively differentiate institutional adoption patterns, we employ data from a survey which we conducted together with the United Nations Global Compact (Rasche & Gilbert, 2012; Rasche et al., 2013) Network Germany. The intention of the survey was to explore and to better understand corporate adoption patterns concerning different types of CSR standards. Besides the UN GC, the study comprised further CSR related initiatives and instruments, including the OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises (Baccaro & Mele, 2011), ISO 26000 (Moratis, 2017), the Global Reporting Initiative (Bradford et al., 2017), SA8000 (Gilbert & Rasche, 2007), and the (German) Sustainability Code (Stawinoga & Velte, 2015). All selected initiatives and instruments are based on an individual normative institutional core and vary with regard to their institutional origin, design, reach, and governance structures. We aimed to involve initiatives and instruments which share the goal to mainstream CSR in business activities but are at the same time different in design to allow for comparative analysis. Thus, we selected international initiatives as well as a more nationally oriented one (the (German) Sustainability Code), initiatives with a wider normative spectrum (e.g., UN GC or GRI), as well as a topically more focused example (SA8000). We also chose initiatives with different actor constellations, i.e., international organizations as well as civil society-driven organizations such as GRI. Despite these differences, all initiatives share a focus on CSR and could potentially be adopted by firms individually and/or complementarily.

In a previous study, our analysis focused on institutional adoption patterns concerning the UN Global Compact only (Jastram & Klingenberg, 2018). We now conduct a comparative data analysis based on all selected initiatives.

Data Collection

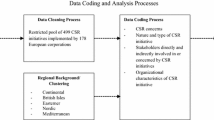

Our general research ambition was inductive in nature as existing theory on how and where in the organization CSR standards are adopted was hitherto missing. We explored the subject by engaging in a mixed-method design (Schifeling & Demetry, 2020). In the first stage, we employed a descriptive quantitative survey to gain a basic understanding of existing institutional adoption patterns. Next, we conducted open qualitative interviews in order to better understand the reasons for different adoption choices.

The quantitative survey was sent out to all registered corporate members of the UN Global Compact Network Germany (N = 274) in May 2013. We received 49 responses (an 18.5% response rate). The survey questions were based on a set of adoption indicators (see Table 1). Detailed information on the theoretical foundations of the indicators and their conceptual development can be found in Jastram & Klingenberg, 2018. The questionnaire is provided in the supplement to this article (Supplement 1). Participants were given a binary choice (“adopted/not adopted”) on each question.

To deepen and to further analyze the insights from the quantitative survey and to derive institutional adoption predictors, we conducted 17 additional qualitative, semi-structured interviews with all survey participants who volunteered to do so. The interviews took place via telephone in June 2013, with about 30 min of interview time, on average. Due to our explorative research interest, we pre-defined a limited number of guiding questions for the interviews (Glaser & Strauss, 1967). The UN Global Compact served as our reference instrument as we knew it was applied by all interviewees. Referring to our indicators, we first asked interviewees how and why the UN GC was applied in specific areas of the firm and then compared the instrument with other initiatives. As all interviewees had already participated in our online survey, they were familiar with our comparative research approach and the other CSR instruments our study was focusing on. Therefore, we could directly engage in open comparative questions such as “The online survey has indicated that some CSR instruments like the UN GC or GRI are being applied more broadly compared to the OECD Guidelines, SA8000, or ISO 26000. What do you think is the reason for this?” (see interview guideline in the supplement to this article: Supplement 2). Moreover, we inquired the application concerning specific indicators, for instance, by asking: “Compared to the UN GC, other instruments are applied less during purchasing/supply chain management. Why do you think this is the case?”. Depending on the timely availability of interviewees and the development of each individual interview, specific topics and indicators were particularly amplified. In order to gain rich data, we rephrased and repeated our questions to facilitate further and deeper reflections by the interviewees.

Data Analysis

Based on the answers to the quantitative survey, we calculated frequencies for the adoption of each of the six CSR initiatives for different management functions. As the data shows substantial differences in frequencies across initiatives/instruments, we further conducted binomial probability tests to check if the observed frequency for a particular initiative or instrument differs significantly from the observed frequencies of other initiatives and instruments. The test results for all initiatives and instruments can be found in the supplement to this article (Supplements 3–8).

Our qualitative data analysis comprised several steps of analytical induction. First, our interviews were transcribed, and all sections relating to the adoption of MSIs and other instruments were coded in order to isolate them from other, unrelated parts of the conversations. Next, we looked for explanations relating to different intraorganizational adoption patterns and individually created lists of possible adoption predictors.

We then engaged in iteration between literature and data to identify a suitable theoretical framing of our first findings. We initially considered the political CSR literature (Matten & Crane, 2005; Scherer & Palazzo, 2007; Scherer et al., 2006). However, we were not fully satisfied with the feasibility of that theory due to its focus on political constructs such as legitimacy or citizenship.

We thus engaged in further literature reviews and discussions among the team of researchers until we identified an institutional theory perspective on a topic similar to ours (Wijen, 2014), which seemed a suitable framing for analyzing standard diffusion and adoption processes. We decided to dive deeper into institutional entrepreneurship (e.g., Battilana et al., 2009) and identified a theoretical gap concerning diverse adoption patterns relating to institutions of a similar type.

Having identified our theoretical context, we reviewed and reduced our data by successively clustering codes based on external heterogeneity until our final list of ten adoption predictors was derived. We then compared our results again with the existing literature in order to reconfirm our contribution. Moreover, we verified our quantitative results as well as our interpretations of the interviews by presenting and discussing these at the annual meeting of the UN Global Compact Network Germany shortly after data collection and initial analysis. We received positive feedback on our results.

The next sections will present our final findings in detail.

Results

The results of our quantitative survey were analyzed in multiple ways.

Table 2 shows absolute and relative frequencies of institutional adoption responses per instrument/initiative across all indicators. The columns show institutional adoption levels for each individual CSR initiative/instrument (organized in rows). Vertically, the table shows adoption frequencies per individual indicator for all CSR initiatives/instruments.

The first figure in the first data column shows, for instance, that 11 people (22.4% of all survey participants) confirmed that the top management of their firm is supporting the OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises, while the first figure in the third data column indicates that 47 people (95.9% of the participants) have confirmed top management support for the UN GC. The table, thus, shows institutional adoption patterns concerning CSR initiatives individually (horizontal reading) but also allows for comparison between them (vertical reading).

Overall, we can identify higher levels of adoption for the UN GC compared to the other institutions, which likely relates to our sampling. Yet, it is interesting that member firms of the UN GC Network Germany report considerably lower adoption rates for most other CSR institutions. Why is this the case? Why did these firms choose to adopt the UN GC rather than other initiatives? Why is the UN GC supported more than ISO 26000, for instance? Are CSR institutions perceived as substitutes, and what determines their selection and adoption by firms? Can we identify general adoption patterns across different management levels that are common for all types of CSR initiatives/instruments?

We used a semantic differential (see Chart 1) to visualize institutional adoption of each CSR initiative/instrument across all indicators/ management functions, and we can see a diversity of adoption patterns (illustrated by differently shaped vertical lines) for each CSR initiative or instrument.

For example, while Table 2 and Chart 1 show that some CSR institutions, such as the UN GC, are strongly applied on the strategic level (e.g., 75% for development of strategic objectives) but less in trainings (40.8%), other institutions such as ISO 26000, the German Sustainability Code, or SA8000 rank comparatively low on all adoption levels. GRI has high adoption levels in the field of reporting (62.2%) but lower rates for top management support (38.8%).

We further found that adoption patterns of the UN GC are significantly different from almost all other CSR instruments (see Supplement 3). For most instruments/initiatives and management functions, we could reject the hypothesis of identical frequencies at the 1%-level.

There are some similarities between GRI (Supplement 6) and UN GC in the fields of measurement and reporting, for example, that can be explained by the institutional linkages between the two initiatives. Regarding the significance of differences in frequencies of the OECD Guidelines (Supplement 4), ISO 26000 (Supplement 5), SA8000 (Supplement 7), and the German Sustainability Code (Supplement 8), the data exhibits no clear pattern. Thus, while there may be similar adoption rates for certain management functions, there is no such evidence for others.

In sum, our quantitative data display clear differences between more extensive and broader intraorganizational institutional adoption patterns (e.g., relating to the UN GC) and more limited and narrow approaches (e.g., relating to SA8000).

In addition to these quantitative results, we engaged in qualitative interviews to discuss and deepen our findings together with some of the survey participants and to develop explanatory predictors (see Table 3) relating to the likelihood of a broad institutional implementation of CSR principles across various management functions.

From our interviews, we first learned that the willingness of firms to adopt CSR institutions increases the more the institution is already established in the market. This became particularly evident when we discussed the higher adoption rates of UN GC and GRI compared to the other CSR institutions in our survey. More specifically, we found that the more publicly known an institution is, the more stakeholders advocate it, and the more firms have already adopted an institution, the higher the likelihood that other firms will follow.

For example, Interviewee No. 2 explained: “[The UN GC] has a very, very high degree of popularity. […] You do not need to explain much. If you come with ISO 26000, you see question marks in the eyes of many people. If one says ‘we are part of the Global Compact’, then that is common sense.” [All interviews were translated from German into English by the authors]. Another interviewee stated: “Today there are many codes and if you wanted to participate everywhere, you couldn’t stop reporting anymore, that is counterproductive. GRI has value because it is an established standard and many have agreed on it.” (Interviewee No. 14). Further interviews followed a similar direction, including statements such as “GRI is just the most established reporting standard.” (Interviewee No. 13), “I stick to what’s established and acknowledged” (Interviewee No. 8), or “It is probably because it [the UN GC] is the best known instrument” (Interviewee No. 4).

Overall, market establishment and publicity were among the most frequently mentioned reasons for interviewees’ preferences towards certain CSR institutions over others. Thus, we formulated our first predictor as: Predictor 1: Publicity of an institution.

Besides publicity, several interviewees also pointed out the relevance of the number of existing adopters for their institutional choices. The following statement exemplifies this view: “There are many companies which have already chosen to participate in the UN Global Compact. […] I realized that many, many companies, […] especially big ones, were already members of the UN Global Compact. And then I said, okay, this has to be a good initiative with value added for the companies […] there is evidence so to say, that the UN Global Compact really works.” (Interviewee No. 1). Interviewee No. 8 agrees: “It [UN GC] is a quality label, […] because by now there are really a lot of participants.” Similarly, several other interviewees stated that they were influenced by what other firms had chosen, so we formulated the second predictor as: Predictor 2: Number of existing adopters.

Our research also found that the adoption of specific institutions can be relationally motivated if stakeholders express certain institutional preferences. As Interviewee No. 4 states: “With the UN Global Compact it is […] that our customers have been asking us about it […] also analysts. And that is why we said okay […] we can principally live with these values and principles, we already live them in our organization. That is why we joined because if you communicate this to your customers, it creates trust.” Another interviewee argued similarly and stressed the relevance of rating agencies for institutional choices in the field of CSR: “GRI is used by stakeholders like rating agencies to assess companies. That’s why it makes sense to apply it during reporting.” (Interviewee No. 13). Another interviewee stated at the example of the Sustainability Code supported by the German government that institutions may not be chosen if there is no substantial market enforcement. “The Sustainability Code was introduced with the argument that the financial sector demands such a code. […] But then this demand wasn’t acually there. […] So that just creates administrative expenses. […] If there is a demand by stakeholders, be it NGOs or consumers or whomever, for more transparency regarding corporate sustainability and if this demand is growing then it will also become addressed, companies then have to because otherwise they could not survive in the market. [But] I cannot create this demand artificially by just forcing everybody to report” (Interviewee No. 9). Correspondingly our next predictor is formulated as: Predictor 3: Stakeholder pressure towards the adoption of an institution.

Predictors 1–3 indicate that there are isomorphic patterns affecting managerial decision-making in the field of CSR governance. Yet, we found further influences on institutional adoption, and one of them is related to the comprehensiveness of an institution. In this context, several interviewees argued that they would rather adopt one institution with a broader scope than several more specific ones. Accordingly, Interviewee No. 9 states: “At the Global Compact, I have the most important values covered. I have it short, easy to understand and I have all material aspects […] included,” and he/she continues: “This does not mean that ISO 26000 is bad but just that the UN Global Compact already covers all relevant aspects.” And similarly: “The UN Global Compact already comprises other initiatives […]. The principles of the UN Global Compact already comprise the ILO Core Labour Standards plus the Human Rights […] and it is connected with GRI.” (Interviewee No. 6) The same comprehensive quality was also stressed regarding GRI which according to Interviewee No. 6: “comprises all you need to present your activities […] in the field of sustainability.”

As UN GC and GRI were more established in the market and more comprehensive than other CSR institutions, interviewees argued that there was no further need to adopt more CSR standards. Correspondingly, Interviewee No. 12 stated: “There are many redundancies between the German Sustainability Code and GRI. […] and I ask myself, do I need to dance on all weddings?”.

Against this background, our next predictor was formulated as: Predictor 4: Comprehensiveness of an institution.

In addition to market establishment and comprehensiveness, our interviews showed that the international reach of institutions is important in the field of CSR. Interviewee No. 1 states: “I think [the UN GC] is a very good instrument because it is an […] international initiative which covers all industries. […]. The Global Compact is internationally known. You do not need to explain much.” Interviewee No. 9 argued similarly: “It [the UN GC] is internationally compatible and applies globally […] while many others […] have a limited target group.” Interviewees specifically stressed the relevance of the international reach for global trade as this statement illustrates: “Imagine you come to China and you say ‘I have signed the German Sustainability Code’, then no one knows what it is in China” (Interviewee No. 9). Consequently, we derived the following fifth predictor: Predictor 5: International reach of an institution.

We further found that institutions in the field of CSR are more likely to be adopted and internalized the easier the institutional integration and adoption can be managed. Corresponding statements by our interviewees were, for instance, “It is because of the manageability, so when I compare [the UN Global Compact] with […] ISO 26000, which is very complex, it [ISO 26000] is hardly applied.” (Interviewee No. 4). Or: “It [the UN Global Compact] is most manageable and the best we have.” (Interviewee No. 5). This need for manageability especially applies for smaller firms with limited resources and capacities: “It must be manageable for companies, also for small and medium sized firms, hands-on, easy to apply, without large data volumes or extensive reporting” (Interviewee No. 5).

Institutional manageability in this context is supported through clear and understandable standards and implementation guidance, materials, as well as training or webinars. Accordingly, Interviewee No. 6 states: “There are clear standards. Also […] the UN Global Compact provides help via webinars and, at least in Germany, is supportive and advisory.” Interviewee No. 5 agrees: “The ten principles of the UN Global Compact are very tangible. This is hands-on, anybody can work with it.” Similar positive statements are articulated relating to GRI: “GRI is easy […], it has clear guidelines which are easy to respond to” (Interviewee No. 6), while negative statements result regarding other standards: “ISO 26000 […] is very complex. With the OECD Guidelines, I have the feeling that these are things that are not immediately accessible” (Interviewee No. 8). He/she continues: “The UN Global Compact and GRI provide much better support.”

Interviewee No. 11 further explains why manageability is an important characteristic: “[CSR standards] must be relatively simple, I mean, most colleagues in the company don’t engage with this in a deep manner so you need concrete and practical guidance.” In other words, coherent and easily applicable standards are more likely to diffuse within an organization and to become applied by colleagues in other departments. The same interviewee further explains: “If I want to use this as a vehicle to enforce a certain topic within the organization and to position it as important, then the level of detail of the UN Global Compact is actually perfect. Anybody can understand it and it’s easily communicable.” Thus, less institutional complexity also facilitates intraorganizational advocacy. Interviewee No. 12 sums it up: “The more operationable you can design something like this with documents and so on, the higher the chances of application.”

Besides these procedural advantages of manageability, it can also include the potential for symbolic adoption if firms choose an institution because it is easy to adopt with no substantial effort or problem-solving intention involved. Thus, manageability can serve both impact-oriented as well as greenwashing-driven CSR activities; in both cases, it is likely to increase standard adoption. Against this background, our next predictor is stated as: Predictor 6: Manageability of an institution.

Apart from manageability, managers stated the relevance of voluntariness and implementation flexibility for institutional adoption: “[The UN GC] leaves space for interpretation but at the same time it is concrete enough so that you can apply it” (Interviewee No. 14). In a similar sense, other interviewees argued that too strict standards would have lower chances of voluntary adoption compared to more flexible ones, assuming other conditions are similar. In this context, Interviewee No. 10 explains: “The UN Global Compact with the ten principles is quickly read […] and you can interpret it as you like. […] The OECD Guidelines […] are more complicated to study and to understand. […] I mean, they don’t make this a secret at the Global Compact, that you could principally upload whatever you want, […] and that you can state whatever comes to your mind in the progress report.” This statement illustrates another potential trade-off between flexibility and the risk of symbolic adoption or free-riding, which can impede the goals of institutional entrepreneurs in the field of CSR. Yet, also in this case, flexibility can serve both types of adoption, symbolic as well as substantive.

Against this background, we suggest Predictor 7: Degree of flexibility of an institution.

Besides these institutional characteristics and general managerial requirements, interviewees explained the relevance of communicability of institutions in a CSR context. Interviewee No. 8 stated: “It [the UN GC] is very simple and very plausible, you can easily explain the ten principles, and you can demonstrate why it makes sense for companies to use it for orientation […] and that it’s worth it.” Similarly, Interviewee No. 16 explains: “[The UN GC] is better known […] and with its political roof it gets more attention than other initiatives. […] and we are allowed to use the UN logo and we do that.”

Being able to utilize the UN Global Compact logo in corporate communications was frequently mentioned during our interviews, like with Interviewee No. 12 who stated: “I mean, sure, you have the nice [UN GC] logo which has a high recognition value.” In this context, Interviewee No. 15 explained the attractiveness of the logo: “I am convinced that [the UN GC] has the highest credibility and advertising effectiveness. […] That is certainly because […] the UN is behind it […] you don’t need to explain much. If I follow ISO 26000 or something else, many do not know what it is. UN, Ban Ki-moon and Global Compact everybody knows.” In that regard, the simple design of the UN Global Compact was stressed as advantageous considering its communicability: “If I ask a supplier ‘show me that you act according to ISO 26000’ then that would lead to a longer discussion. But if I create a questionnaire based on the [UN GC’s] ten principles or raise it as part of a supplier audit, then I use the four terms — human rights, labor rights, environment, and corruption — and we easily get into a conversation, and I can assess my supplier according to these four headlines” (Interviewee No. 17).

Based on these findings, we derived the next predictor: Predictor 8: Communicability of an institution.

Besides all revealed arguments, the overall costs of institutional adoption were often mentioned as potential barriers by our interview partners. In this context, costs can include costs of participation (i.e., fees, travel and accommodation costs, work hours) as well as resources necessary for institutional implementation, such as trainings or internal and external communication. Furthermore, interviewees specifically mentioned supply chain related costs referring to supplier communication, training and capacity building as well as auditing.

In this context, firms stated that the costs of voluntary institutional adoption need to be outweighed by potential economic benefits. As Interviewee No. 14 explained: “For ISO 26000 I cannot see an added value, because there are many certifications that go into a similar direction. […] There are many established certifications that already cover many aspects […] and each certification is of course resource intensive and can be very costly. So there has to be an added value to justify the costs.” Interviewee No. 11 adds: “Some companies flinch because this audit tourism increased massively. Every additional auditor in the house is a problem for most companies. It costs resources.”

Thus, we added the next predictor as: Predictor 9: Advantageous cost–benefit ratio of institutional adoption.

Finally, legitimacy was mentioned as an important criterion by the interviewed managers. The term was, in most cases, related to the Global Compact and the United Nations behind it. Interviewee No. 8 states, for instance: “The Global Compact […] is on the UN level […]. It is a quality label, that was established by the General Secretary of the United Nations Ban Ki-moon, Kofi Annan earlier.” Moreover, Interviewee No. 9 refers to the legitimacy of the development process of the UN GC: “The UNO as highest institution of the international community as well as the civil society were involved.”

Thus, the last of our ten predictors is called: Predictor 10: Perceived legitimacy of an institution.

Table 3 summarizes all ten predictors.

Discussion and Conclusion

Our empirical analysis has highlighted the diversity of intraorganizational institutional adoption profiles and provides predictors for more extensive, and broad versus rather limited and narrow implementation choices. It became clear that adoption patterns do not look alike and that organizations do not adopt similar institutions in a similar manner but implement each standard differently.

While the contour of each adoption pattern might change over time, for our main argument, the exact shape of each adoption profile is not constitutive. The important insight from our data is that a yes/no answer to the question of whether organizations apply external CSR standards is not capturing the variety of intraorganizational adoption behavior.

Instead, our results show that there are different forms of organizational standard application, which has consequences for the impacts of CSR governance, as discussed earlier in this paper. Moreover, our interviews indicate that adoption diversity, as a response to institutional pressure, is likely to remain because, while those institutions are highly similar, they are different in specific characteristics, which are crucial for integrative implementation. If an institution is manageable and flexible, for instance, it is easier to become implemented across management functions in different organizational contexts. Another example is international reach which determines whether an institution will play a role in international organizational operations.

Some of these predictors are also supported by existing research. Scholars such as De Bakker et al. (2019), Rasche et al. (2020), Mena and Palazzo (2012), or Sauer and Hiete (2020) have, for instance, identified topics like institutional legitimacy as a driver for institutional adoption. Other predictors, including comprehensiveness (Sauer & Hiete, 2020), a beneficial cost–benefit ratio (Fransen et al., 2019; Moog et al., 2015), or communicability (Brown et al., 2018; Nesadurai, 2013), have also been discussed in the literature earlier. However, this discourse has so far been rather fragmented, and by adding further institutional adoption predictors, we are contributing a more comprehensive list of drivers for institutional change, which enables us to estimate and explain the variety of institutional adoption patterns in the field of CSR in a more holistic manner. Furthermore, by illustrating the diversity of intraorganizational adoption patterns, we add a more differentiated perspective to the existing literature, which has treated the adoption of CSR standards hitherto largely as binary (e.g., Baumann-Pauly & Scherer, 2013; Brown et al., 2018; Wijen, 2014).

Moreover, we add to existing typologies (e.g., Fransen et al., 2019; Ponte et al., 2020), which focus on clustering the variety of existing standards and initiatives, by shifting the analytical perspective towards the intraorganizational response of addressed actors. Likewise, while the general multiplicity of existing standards and initiatives has already been identified by the existing literature (e.g., Fransen et al., 2019; Djelic & Den Hond, 2014), a comparative view of organizational adoption has so far been missing adding a further analytical level to the discourse. In this context, our analysis of intraorganizational adoption patterns highlights a new dimension of multiplicity, the multiplicity of organizational institutional adoption, and thereby enriches the understanding of a complex and still growing field of research. In addition, we add to the institutional decoupling discourse (Bromley & Powell, 2012; De Bakker et al., 2019; Wijen, 2014) by providing insights into potential intraorganizational reasons for policy-practice as well as means-ends decoupling. If, for instance, an institution is supported by the top management of an organization but not further implemented into trainings or supplier relations (policy-practice decoupling), positive results along supply chains (ends) can hardly be achieved. In other words, we provide a differentiation of potentially coupled or decoupled management practice by identifying broad versus narrow managerial implementation patterns relating to institutional policies. Our findings could, thereby, inspire future decoupling research to further investigate intraorganizational adoption patterns and, more generally, to discuss and analyze which management levels are relevant for the coupling of policy and practice as a condition for systematic change.

Finally, our analysis explains why firms choose to adopt certain institutions in the field of CSR over others, and it specifies which drivers and barriers determine voluntary adoption. We identified mainly instrumental and relational drivers (Aguilera et al., 2007), often both attributable to the same interviewee statements (e.g., when articulated relational motives were instrumental at the same time as in the case of strategic stakeholder relationships). Interviewees also mentioned several drivers in combination with each other (e.g., legitimacy and communicability), which indicates an interrelatedness of predictors.

Our findings are also relevant for practitioners in the field of governance because they make institutional implementation patterns, managerial motives, and barriers of standard adoption transparent, which is necessary for the further development and improvement of CSR governance approaches. Considering the fact that institutional development processes may take years to evolve and can involve thousands of institutional entrepreneurs as well as large financial and time investments (Jastram & Klingenberg, 2018), it is important to understand why institutions fail and/or do not become as widely adopted as expected. Thus, institutional entrepreneurs may consider our predictors as benchmarks when (further) developing governance standards in the field of CSR.

The limitations of this study are mainly related to the selection bias in our sample as all respondents were members of the UN Global Compact Network Germany and thus biased towards that institution. We do, however, argue that it is nevertheless interesting to understand why firms decide to choose one institution (UN GC) over another, how and why other institutions were adopted (or neglected) in addition to the UN GC, and in which management functions adoption takes place. Yet, it would be interesting to compare our results with current data from a larger, international sample to address the potential national bias in our study and to analyze if and how institutional adoption profiles change over time.

Moreover, we invite researchers to engage in further vertical and horizontal analyses of our data presented in Table 2. Additional vertical analyses could bring about deeper insights into institutional adoption patterns of each individual standard or initiative. As our data shows, all adoption profiles look different from each other and it will, therefore, be interesting to analyze and discuss each profile in detail, individually and/or from a comparative perspective. We did undertake an in-depth profile analysis of the UN Global Compact and found an interesting paradoxical combination of strong outcomes on strategic management levels combined with significantly weaker enforcement outcomes related to employee trainings or measurement of goal attainment (Jastram & Klingenberg, 2018). Other profiles will show different patterns and we suggest that each pattern is worth an in-depth analysis considering the individual history and design of each initiative. We, therefore, suggest further, comprehensive adoption profile studies, which could be based on our findings but also include additional data from ethnographic methods for instance.

Moreover, we suggest further horizontal analyses based on our data presented in Table 2. Researchers could focus on one or more management levels, and compare and interpret relative adoption frequencies of different institutions. Papers could be focussing on individual management functions and comparatively discuss the role of the different standards and initiatives in specific intraorganizational contexts. In doing so, researchers could employ various theoretical perspectives such as principal-agent theory for instance (Jensen & Meckling, 1976) when analyzing the application of the different institutions in supply chain management or marketing theories when comparing the adoption of different standards in communication and reporting.

Finally, it should be stressed again, that any related research needs to consider that our predictors explain motives and barriers for institutional adoption but do not differentiate between substantive and symbolic adoption. A highly flexible institution, for instance, bears a risk of symbolic adoption (or greenwashing) but it also allows organizations to overperform and go beyond minimum compliance. Substantive institutional adoption is a process that involves concerted implementation measures including employee training, for example, as well as the use of key performance indicators and monitoring (Jastram & Klingenberg, 2018), and we regard the conditions of substantive adoption of CSR standards as an important field of research to better understand the drivers and barriers of effective CSR governance.

References

Aguilera, R. V., Rupp, D. E., Williams, C. A., & Ganapathi, J. (2007). Putting the S back in corporate social responsibility: A multilevel theory of social change in organizations. Academy of Management Review, 32(2), 836–863.

Aldrich, H. E., & Fiol, C. M. (1994). Fools rush in? The institutional context of industry creation. Academy of Management Review, 19(4), 645–670.

Alvord, S. H., Brown, L. D., & Letts, C. W. (2004). Societal entrepreneurship and societal transformation: An explanatory study. The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 40(3), 260–282.

Auld, G., Renckens, S., & Cashore, B. (2015). Transnational private governance between the logics of empowerment and control. Regulation & Governance, 9, 108–124.

Baccaro, L., & Mele, V. (2011). For lack of anything better? International organizations and global corporate codes. Public Administration, 89(2), 451–470.

Banerjee, S. B. (2008). Corporate social responsibility: The good, the bad and the ugly. Critical Sociology, 34(1), 51–79.

Bansal, P., & Roth, K. (2000). Why companies go green: A model of ecological responsiveness. Academy of Management Journal, 43(4), 717–736.

Baron, D. P., & Lyon, T. P. (2012). Environmental governance. In P. Bansal & A. J. Hoffman (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of business and the natural environment (pp. 122–139). Oxford University Press.

Battilana, J. (2006). Agency and institutions: The enabling role of individuals’ social position. Organization, 13(5), 653–676.

Battilana, J. (2007). Initiating divergent organizational change: The enabling role of actors’ social position. In Academy of management annual meeting proceedings (pp. 7–53).

Battilana, J., Leca, B., & Boxenbaum, E. (2009). How actors change institutions: Towards a theory of institutional entrepreneurship. The Academy of Management Annals, 3(1), 65–107.

Baumann-Pauly, D., & Scherer, A. G. (2013). The organizational implementation of corporate citizenship: An assessment tool and its application at UN global compact participants. Journal of Business Ethics, 117, 1–17.

Berger, P. L., & Luckmann, T. (1966). The social construction of reality: A treatise in the sociology of knowledge (pp. 78–79). Penguin Books.

Bradford, M., Earp, J. B., Showalter, D. S., & Williams, P. F. (2017). Corporate sustainability reporting and stakeholder concerns: Is there a disconnect? Accounting Horizons, 31(1), 83–102.

Bromley, P., & Powell, W. W. (2012). From smoke and mirrors to walking the talk: Decoupling in the contemporary world. The Academy of Management Annals, 6(1), 483–530.

Brown, J. A., Clark, C., & Buono, A. F. (2018). The United Nations global compact: Engaging implicit and explicit CSR for global governance. Journal of Business Ethics, 147, 721–734.

Cashore, B., Knudsen, J. S., Moon, J., & Van der Ven, H. (2020). Private authority and public policy interactions in global context: Governance spheres for problem solving. Regulation & Governance. https://doi.org/10.1111/rego.12395

Chandler, D., & Hwang, H. (2015). Learning from learning theory: A model of organizational adoption strategies at the microfoundations of institutional theory. Journal of Management, 41(5), 1446–1476.

Chowdhury, R. (2017). The Rana Plaza disaster and the complicit behavior of elite NGOs. Organization, 24(6), 938–949.

Chowdhury, R. (2019). Critical essay: (In)sensitive violence, development, and the smell of the soil: Strategic decision-making of what? Human Relations, 74(1), 131–152.

Chowdhury, R. (2021). The mobilization of noncooperative spaces: Reflections from rohingya refugee camps. Journal of Management Studies, 58(3), 914–921.

Christmann, P., & Taylor, G. (2006). Firm self-regulation through international certifiable standards: Determinants of symbolic versus substantive implementation. Journal of International Business Studies, 37(6), 863–878.

Clark, C., Rosenzweig, W., Long, D., & Olsen, S. (2004). Double bottom line project report: Assessing social impact in double bottom line ventures. Working paper No. 13, University of California, Berkeley.

Clean Clothes Campaign. (2021). Who paid up and who failed to take responsibility? Retrieved February 21, 2021, from https://archive.cleanclothes.org/safety/ranaplaza/who-needs-to-pay-up.

Cropanzano, R., Goldman, B., & Folder, R. (2003). Deontic justice: The role of moral principles in workplace fairness. Journal of Organizational Behaviour, 24(8), 1019–1024.

De Bakker, F. G. A., Rasche, A., & Ponte, S. (2019). Multi-stakeholder initiatives on sustainability: A cross-disciplinary review and research agenda for business ethics. Business Ethics Quarterly, 29(3), 343–383.

Dietz, T., Ostrom, E., & Stern, P. C. (2003). The struggle to govern the commons. Science, 302, 1907–1912.

DiMaggio, P. J. (1988). Interest and agency in institutional theory. In L. G. Zucker (Ed.), Research on institutional patterns: Environment and culture (pp. 3–21). Ballinger Publishing Co.

DiMaggio, P. J., & Powell, W. W. (1983). The iron cage revisited: Institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational fields. American Sociological Review, 48(2), 147–160.

Djelic, M. L., & Den Hond, F. (2014). Introduction: Multiplicity and plurality in the world of standards: Symposium on multiplicity and plurality in the world of standards. Business and Politics, 16(1), 67–77.

Etzion, D., & Ferraro, F. (2010). The role of analogy in the institutionalization of sustainability reporting. Organization Science, 21(5), 1092–1107.

Ferraro, F., Etzion, D., & Gehman, J. (2015). Tackling grand challenges pragmatically: Robust action revisited. Organization Studies, 36(3), 363–390.

Fligstein, N. (1997). Social skill and institutional theory. American Behavioral Scientist, 40(4), 397–405.

Fransen, L., & Kolk, A. (2007). Global rules-setting for business: A critical analysis of multi-stakeholder standards. Organization, 14(5), 667–684.

Fransen, L., Kolk, A., & Rivera-Santos, M. (2019). The multiplicity of international corporate social responsibility standards: Implications for global value chain governance. Multinational Business Review, 27(4), 397–426.

Garud, R., Jain, S., & Kumaraswamy, A. (2002). Institutional entrepreneurship in the sponsorship of common technological standards: The case of sun microsystems and java. Academy of Management Journal, 45(1), 196–214.

Garud, R., Hardy, C., & Maguire, S. (2007). Institutional entrepreneurship as embedded agency: An introduction to the special issue. Organization Studies, 28(7), 957–969.

Gilbert, D. U., & Rasche, A. (2007). Discourse ethics and social accountability: The ethics of SA 8000. Business Ethics Quarterly, 17(2), 187–216.

Glaser, B. G., & Strauss, A. (1967). The discovery of grounded theory—strategies for qualitative research. Nursing Research. https://doi.org/10.1097/00006199-196807000-00014

Gottschalg, O., & Zollo, M. (2007). Interest alignment and competitive advantage. Academy of Management Review, 32(2), 418–437.

Greenwood, R., & Hinings, C. R. (1996). Understanding radical organizational change: Bringing together the old and the new institutionalism. Academy of Management Review, 21(4), 1022–1054.

Greenwood, R., Raynard, M., Kodeih, F., Micelotta, E. R., & Lounsbury, M. (2011). Institutional complexity and organizational responses. The Academy of Management Annals, 5(1), 317–371.

Hardy, C., & Maguire, S. (2013). Institutional entrepreneurship. In R. Greenwood, C. Oliver, R. Suddaby, & K. Sahlin (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of organizational institutionalism, Paperback edition. Sage Publications Ltd.

Hoffman, A. J. (1999). Institutional evolution and change: Environmentalism and the U.S. chemical industry. Academy of Management Journal, 42(4), 351–371.

Holm, P. (1995). The dynamics of institutionalization: Transformation processes in Norwegian fisheries. Administrative Science Quarterly, 40(3), 398–422.

Jastram, S. (2016). Habermas’ theorie und die legitimation von multi-stakeholder-verfahren in der praxis. In M. Scholz & M. Czuray (Eds.), ISO 26000 und ONR 192500: Leitlinien und Normen zur Unternehmensverantwortung (pp. 3–11). Springer Gabler.

Jastram, S. M., & Klingenberg, J. (2018). Assessing the outcome effectiveness of multi-stakeholder initiatives in the field of corporate social responsibility—the example of the United Nations global compact. Journal of Cleaner Production, 189, 775–784.

Jastram, S. M., & Schneider, A.-M. (Eds.). (2018a). Sustainable fashion—governance and new management approaches. Springer.

Jastram, S. M., & Schneider, A.-M. (2018b). New business and governance approaches to sustainable fashion—learning from the experts. In S. M. Jastram & A.-M. Schneider (Eds.), Sustainable fashion—governance and new management approaches. Springer.

Jensen, M. C., & Meckling, W. H. (1976). Theory of the firm: Managerial behavior, agency costs and ownership structure. Journal of Financial Economics, 3(4), 305–360.

Jiang, J. J., & Bansal, P. (2003). Seeing the need for ISO 14001. Journal of Management Studies, 40(4), 1047–1067.

Khan, F. R., Munir, K. A., & Willmott, H. (2007). A dark side of institutional entrepreneurship: Soccer balls, child labour and postcolonial impoverishment. Organization Studies, 28(07), 1055–1077.

King, A., Prado, A. M., & Rivera, J. (2012). Industry self-regulation and environmental protection. In P. Bansal & A. J. Hoffman (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of business and the natural environment (pp. 103–121). Oxford University Press.

Lawrence, T. B., Hardy, C., & Phillips, N. (2002). Institutional effects of interorganizational collaboration: The emergence of proto-institutions. Academy of Management Journal, 45(1), 281–290.

Levy, D. L., & Lichtenstein, B. B. (2012). Approaching business and the environment with complexity theory. In P. Bansal & A. J. Hoffman (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of business and the natural environment (pp. 591–608). Oxford University Press.

Levy, D. L., & Scully, M. A. (2007). The institutional entrepreneur as modern prince: The strategic face of power in contested fields. Organization Studies, 28(7), 971–991.

Lounsbury, M., & Crumley, E. T. (2007). New practice creation: An institutional perspective on innovation. Organization Studies, 28(7), 993–1012.

Matten, D., & Crane, A. (2005). Corporate citizenship: Toward an extended theoretical conceptualization. Academy of Management Review, 30, 166–179.

Matten, D., & Moon, J. (2008). ‘“Implicit”’ and ‘“explicit”’ CSR: A conceptual framework for a comparative understanding of corporate social responsibility. Academy of Management Review, 33(2), 404–424.

Mena, S., & Palazzo, G. (2012). Input and output legitimacy of multi-stakeholder initiatives. Business Ethics Quarterly, 22(3), 527–556.

Meyer, J. W., & Rowan, B. (1977). Institutionalized organizations: Formal structure as myth and ceremony. American Journal of Sociology, 83(2), 340–363.

Moog, S., Spicer, A., & Böhm, S. (2015). The politics of multi-stakeholder initiatives: The crisis of the forest stewardship council. Journal of Business Ethics, 128, 469–493.

Moratis, L. (2017). The credibility of corporate CSR claims: A taxonomy based on ISO 26000 and a research agenda. Total Quality Management, 28(2), 147–158.

Mückenberger, U., & Jastram, S. (2010). Transnational norm-building networks and the legitimacy of corporate social responsibility standards. Journal of Business Ethics, 97, 223–239.

Nesadurai, H. E. S. (2013). Food security, the palm oil-land conflict nexus, and sustainability: A governance role for a private multi-stakeholder regime like the RSPO? The Pacific Review, 26(5), 505–529.

Olsen, N., & Boxenbaum, E. (2009). Bottom-of-the-pyramid: Organizational Barriers to Implementation. California Management Review, 51(4), 100–125.

Pache, A.-C., & Santos, F. (2010). When worlds collide: The internal dynamics of organizational responses to conflicting institutional demands. Academy of Management Review, 35(3), 455–476.

Perez-Aleman, P., & Sandilands, M. (2008). Building value at the top and the bottom of the global supply chain: MNC-NGO partnerships. California Management Review, 51(1), 24–49.

Ponte, S., Noe, C., & Mwamfupe, A. (2020). Private and public authority interactions and the functional quality of sustainability governance: Lessons from conservation and development initiatives in Tanzania. Regulation & Governance. https://doi.org/10.1111/rego.12303

Rasche, A. (2009). “A necessary supplement”: What the United Nations global compact is and is not. Business & Society, 48(4), 511–537.

Rasche, A. (2012). Global policies and local practice: Loose and tight couplings in multi-stakeholder initiatives. Business Ethics Quarterly, 22(4), 679–708.

Rasche, A., & Gilbert, D. U. (2012). Institutionalizing global governance: The role of the United Nations global compact. Business Ethics: A European Review, 21(1), 100–114.

Rasche, A., Waddock, S., & McIntosh, M. (2013). The United Nations global compact: Retrospect and prospect. Business & Society, 52(1), 6–30.

Rasche, A., Gwozdz, W., Lund Larsen, M., & Moon, J. (2020). Which firms leave multi-stakeholder initiatives? An analysis of delistings from the UN global compact. Regulation & Governance. https://doi.org/10.1111/rego.12322

Roloff, J. (2008). Learning from multi-stakeholder networks: Issue-focussed stakeholder management. Journal of Business Ethics, 82, 233–250.

Sauer, P. C., & Hiete, M. (2020). Multi-stakeholder initiatives as social innovation for governance and practice: A review of responsible mining initiatives. Sustainability, 12(1), 236.

Scherer, A. G., & Palazzo, G. (2007). Toward a political conception of corporate responsibility. Business and society seen from a Habermasian perspective. Academy of Management Review, 32, 1096–1120.

Scherer, A. G., Palazzo, G., & Baumann, D. (2006). Global rules and private actors: Toward a new role of the transnational corporation in global governance. Business Ethics Quarterly, 16(4), 505–532.

Schifeling, T., & Demetry, D. (2020). The new food truck in town: Geographic communities and authenticity-based entrepreneurship. Organization Science, 32(1), 133–155.

Schleifer, P., Fiorini, M., & Auld, G. (2019). Transparency in transnational governance: The determinants of information disclosure of voluntary sustainability programs. Regulation & Governance, 13, 488–506.

Seo, M., & Creed, W. E. D. (2002). Institutional contradictions, praxis, and institutional change: A dialectical perspective. Academy of Management Review, 27(2), 222–247.

Shane, S., & Venkataraman, S. (2000). The promise of entrepreneurship as a field of research. Academy of Management Review, 25(1), 217–226.

Siltaloppi, J., Rajala, R., & Hietala, H. (2020). Integrating CSR with business strategy: A tensions management perspective. Journal of Business Ethics. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-020-04569-3

Sine, W. D., David, R. J., & Mitsuhashi, H. (2007). From plan to plant: Effects of certification on operational start-up in the emergent independent power sector. Organization Science, 18(4), 578–594.

Stawinoga, M., & Velte, P. (2015). CSR management and reporting between voluntary bonding and legal regulation. First empirical insights of the compliance to the German sustainability code. Problems and Perspectives in Management, 13(2), 36–50.

Sterman, J. D. (2000). Business dynamics: Systems thinking and modeling for a complex world. Irwin McGraw-Hill.

Terlaak, A. (2007). Order without law? The role of certified management standards in shaping socially desired firm behaviors. Academy of Management Review, 32(3), 968–985.

Timmermans, S., & Epstein, S. (2010). A world of standards but not a standard world: Toward a sociology of standards and standardization. Annual Review of Sociology, 36(1), 69–89.

Tyler, T. R., & Lind, E. A. (1992). A relational model of authority in groups. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 25, 115–192.

United Nations Global Compact. (2021). Our participants. Retrieved February 21, 2021, from https://www.unglobalcompact.org/what-is-gc/participants.

Utting, P. (2002). Regulating business via multistakeholder initiatives: A preliminary assessment. In UGLS & UNRISD (Eds.), Voluntary approaches in corporate responsibility: Readings and a resource guide. Geneva.

Wijen, F. (2014). Means versus ends in opaque institutional fields: Trading off compliance and achievement in sustainability standard adoption. Academy of Management Review, 39(3), 302–323.

Young, O. R. (2012). Navigating the sustainability transition: Governing complex and dynamic socio-ecological systems. In E. Brousseau, T. D. Aerdere, P.-A. Jouvet, & M. Willinger (Eds.), Global environmental commons: Analytical and political challenges in building governance mechanisms (pp. 80–101). Oxford University Press.

Yuan, W., Bao, Y., & Verbeke, A. (2011). Integrating CSR initiatives in business: An organizing framework. Journal of Business Ethics, 101(1), 75–92.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jastram, S.M., Otto, A.H. & Minulla, T. Diverse Organizational Adoption of Institutions in the Field of Corporate Social Responsibility. J Bus Ethics 183, 1073–1088 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-022-05085-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-022-05085-2