Abstract

Research studying the effects of non-financial goals on stakeholder relationships remains inconclusive, with scholars disagreeing on which goals increase or decrease a firm’s proactive stakeholder engagement (PSE). Instead of examining which goals act as forces for good or evil, we shift the focus of recent discussions by emphasizing the mechanisms that can explain the positive and negative stakeholder outcomes of non-financial goals under the umbrella of one theoretical lens. We do so by introducing an ethics of care perspective. Specifically, we first show that four of the five most distinctive non-financial goals of family owners jointly stipulate care-based morality, which likely enhances PSE. However, we subsequently argue that one goal, namely, the wish to exert power and influence, interacts with other goals and related care-based morality to lower PSE. Finally, we show how female family directors temper these interactions. Our insights into the additive and interactive effects of non-financial goals on PSE contribute to corporate social responsibility research, to the organizational goal literature, to family business studies and to work drawing on care ethics in management studies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The purpose of business organizations and their benefits to internal and external stakeholders is increasingly called into question (Mitchell et al., 2016; Porter & Kramer, 2019). In this context, scholars highlight the pressing need for future studies to move beyond financial performance indicators and to pay increased attention to firms’ non-financial goals and outcomes (De Massis, Fini, et al. De Massis, Fini, et al., 2020; Kotlar et al., 2018). Although a substantial body of literature emphasizes that organizational actors often pursue different goals (Cyert & March, 1963), the effects of goals other than profitability have long been neglected (Greve, 2008; Kammerlander & Ganter, 2015). To rectify this omission, the emerging literature on organizational goals seeks to explore the multitude and effects of non-financial goals (Hart & Zingales, 2017; Kotlar et al., 2018) and has turned to family business research to better understand the latter (Chua et al., 2018).

Family firms are one of the most prevalent and important types of organization around the world (Carney et al., 2017; IFERA, 2003; Memili et al., 2015). Research on family-owned firms has long emphasized that family business owners pursue non-financial goals alongside financial aspirations and generate detailed accounts on the unique characteristics of family-derived, non-financial goals (Chrisman et al., 2012; Zellweger et al., 2013). For instance, family members seek to cherish positive emotions associated with the business and foster binding ties to important firm stakeholders (Gomez-Mejia et al., 2011). These non-financial goals arise from and contribute to the affective endowments that many family owners hold through their firms, referred to as socioemotional wealth (SEW) (Berrone et al., 2012).Footnote 1 Within this literature, several studies have addressed the important question of how these family-derived, non-financial goals affect firms’ corporate social responsibility (CSR) (e.g., Astrachan Binz et al., 2017; Mariani et al., 2021). However, whereas research predominantly agrees that non-financial goals improve firms’ environmental outcomes (Berrone et al., 2010; Cruz et al., 2014), their effects on stakeholders remain inconclusive.

Stakeholder value creation is a vital aspect of a firm’s CSR (Freeman et al., 2010). Proactive stakeholder engagement (PSE) is characterized by a firm’s active stance towards stakeholders, anticipating and honouring their needs and generating substantive, stakeholder-oriented practices (e.g., Cennamo et al., 2012; Hillman & Keim, 2001; Sharma, 2000). Some scholars theorize that all major family-centred non-financial goals discussed in the literature should increase firms’ PSE (Cennamo et al., 2012). In contrast, other studies postulate that certain non-financial goals likely decrease PSE (Cruz et al., 2014; Kellermanns et al., 2012; Zientara, 2017). Despite these valuable conceptualizations and insights, we lack an understanding of the mechanisms that turn non-financial goals from generating positive stakeholder effects to generating negative effects. Furthermore, we do not know how the non-financial goals commonly pursued by families interact to either promote or hinder PSE. This is important because recent scholarly work has cautioned that multiple organizational goals may have additive and interactive effects (Greve, 2008; Kotlar et al., 2018) that need to be better accounted for.

Moreover, past studies tend to draw on non-financial goals to explain PSE without theorizing the underlying morality that those family-centred goals jointly stipulate. However, uncovering family firms’ distinct ethical approaches is important because scholars have accused family firms of cherry-picking CSR topics for the self-serving purpose of achieving specific non-financial goals, which prevents them from engaging in a “whole-business view of responsibility” (Zientara, 2017, p. 185). We argue that this scholarly accusation has arisen because the family business literature, although shedding light on values (e.g., Duh et al., 2010; Koiranen, 2002), virtues (Payne et al., 2011) and spirituality (Astrachan et al., 2020; Le Breton-Miller & Miller, 2016), has yet to explain how the overall ethical approach to CSR differs between family and non-family firms. Indeed, a recent comprehensive review of relevant literature reveals that business ethics research in the context of family businesses is underdeveloped and in its initial stage (Vazquez et al., 2018). We tap into this research gap by conceptualizing the relationship between family firms’ non-financial goals and business ethics and theorizing about their effects on PSE.

We do so by drawing on an ethics of care perspective. Originating from feminist theory, the ethics of care perspective is a relational approach to morality that emphasizes interconnectedness, emotions, nurturing, and responsibility to particular others (Gilligan, 1982; Held, 2006; Tronto, 1993). Importantly, the ethics of care perspective rejects an abstract, universal deliberation of morality, which centres on the realm of reason. Therefore, the ethics of care stands in contrast to the ‘ethics of justice’, which encompasses traditional ethical theories such as a Kantian view of ethics (Nunner-Winkler, 1993; Simola, 2003).

In this paper, we propose a conceptual model linking the most prominent non-financial goals of family firms to the core features of the ethics of care and argue that four of the five most recognized non-financial goals deriving from owners’ SEW are likely to foster moral reasoning aligned with the ethics of care. We then theorize on the complex relationship between one of the five SEW-related goals, i.e., the family owners’ wish to exert power and influence, and the ethics of care. Next, we conceptualize how care-based morality fosters PSE in family firms pursuing non-financial goals. However, we theorize that the goal of exerting power and influence will interact with the other non-financial goals and the related care-based morality to lower PSE. Finally, we highlight that the negative effects of such goal interactions are tempered by the presence of female family directors. Our focus on female family directors is in line with the feminist tradition of the ethics of care (Gilligan, 1982) and responds to the gender inequality that prevails in many family firms (Hamilton, 2006).

We make several contributions to existing scholarship. First, our theorizing contributes to the literature on CSR in family firms by explaining how family owners’ non-financial goals instil a special kind of morality based on the ethics of care that stands in contrast to what is traditionally referred to in ethical theory, notably, the notion of justice and universal rights (Held, 2006), which impacts family firms’ PSE. We build on previous insights that non-financial goals might be a double-edged sword (Cruz et al., 2014) by conceptualizing when and why the same non-financial goals that promote PSE hinder the latter, explaining the mixed findings of existing research with regard to family firms’ social responsibility. Second, our work contributes to the organizational goals literature, which has called for additional outcome measures, such as PSE, to close the conceptual gap between various organizational goals on the one hand and firm performance on the other (Kotlar et al., 2018). Moreover, most studies within the literature have used a trade-off perspective when exploring different goals of family firms and their effects on firm outcomes (Vazquez & Rocha, 2018). Instead of focusing on such goal conflicts, we reveal the additive and interactive effects of various non-financial goals that need to be better accounted for (Greve, 2008; Kotlar et al., 2018). Finally, we contribute to the growing literature on the ethics of care (e.g., Antoni et al., 2020; Carmeli et al., 2017; Hamington, 2019) by showing how the features of ethics of care explain the morality of family-owned firms, the most prevalent form of organization (La Porta et al., 1999). Importantly, we introduce a critical view of the ethics of care by highlighting that although care-based morality can generate beneficial outcomes for stakeholders, it also has the potential to cause negative effects due to the exploitation of power inequalities inherent in the ethics of care.

The remainder of this conceptual paper is structured as follows. First, we provide an overview of the literature on non-financial goals and business ethics in family firms and introduce the ethics of care. We subsequently develop propositions on specific non-financial goals and their relationship to core features of the ethics of care (Propositions 1 and 2). Next, we theorize on the effects of care-based morality and the family’s quest for power on PSE (Propositions 3 and 4). Finally, we evaluate the role of female family directors (Proposition 5) and discuss the contributions of our framework to the existing literature, highlighting new avenues for future scholarship.

Family Firms’ Non-financial Goals and Care-Based Morality

Non-financial Goals in Family Firms

Research on family firms has grown substantially (Williams et al., 2018), with scholars particularly interested in the unique goals of this type of organization (Chrisman et al., 2012; Gomez-Mejia et al., 2007; Zellweger et al., 2012). The goals of family firms are often driven by family-centric, non-financial motivations, which affect family firms’ decision-making and behaviour (Kotlar et al., 2018; Sciascia et al., 2015). For instance, non-financial goals have been shown to affect intrafamily successions (De Massis et al., 2008), family firms’ reaction to disruptive changes (Kammerlander & Ganter, 2015), strategic reference points (Kotlar et al., 2014), and the level of socioemotional wealth in the firm, i.e., SEW (Berrone et al., 2012; Gomez-Mejia et al., 2007).

Family firms can differ from one another with regard to their non-financial goals (Chrisman et al., 2012; Chua et al., 2012) because they reflect the owning family’s personal motivations (Mitchell et al., 2011). Nevertheless, the SEW literature has revealed distinctive dimensions of affective endowments, which are characteristic of many family firms, such as the families’ influence over and emotional attachment to the firm, helping researchers differentiate between family and nonfamily firms (Berrone et al., 2012). These SEW endowments both stipulate and derive from family-centred, non-financial goals and motivations (Debicki et al., 2009; Williams et al., 2018). The multiple goals of family firms can be conflicting (Hauck et al., 2016; Vardaman & Gondo, 2014). For instance, research has pointed out that externally oriented non-financial goals such as wishing to promote a favourable firm image can sometimes be in conflict with internal family goals, for instance, the wish to exert family control over generations (Block, 2010; Hauck et al., 2016). Individual family owners can experience such goal conflicts within themselves, affecting firm behaviour and performance (De Massis et al., 2018).

Business Ethics and Morality in Family Firms

Research at the intersection of business ethics and family firms is scarce (Vazquez, 2018). Drawing on virtue ethics, initial scholarship has found that family firms tend to communicate higher levels of some virtues, notably, empathy, warmth, and zeal, but score lower on other virtues, notably courage, compared to nonfamily firms (Payne et al., 2011). Despite these important insights, it remains understudied why family firms report higher levels of some virtues but lower levels of others. Moreover, the link to firm outcomes, notably the benefits of the family firm’s virtue orientation for firm stakeholders, remains unexplored. Somewhat relatedly, other research found that certain values such as honesty, credibility, and quality are likely to be pronounced in family firms (Koiranen, 2002). Despite an interesting and growing literature on value dynamics in family firms, particularly in the context of entrepreneurship and succession (Hjorth & Dawson, 2016; Jaskiewicz et al., 2016; Raitis et al., 2021), it remains underconceptualized how the moral values of the family shape stakeholder relationships.

One key assumption in the family business literature is that family owners exert substantial influence over their organizations (e.g., Berrone et al., 2012). To explain the influence of the owning family on the firm’s stakeholder relationships, it is therefore necessary to rely on ethical theory that does not solely focus on ‘public’ life but acknowledges the moral significance of the ‘private’ domain of the family (Held, 2006). The ethics of care provides such conceptual insights as it explains the morality guiding family relationships, characterized by unequal power distributions and laden with emotions. Unlike virtue ethics, which focuses on the character of individuals, the ethics of care perspective centres on caring relations (Held, 2006). Caring relations have primary value and are applicable not only in the private domain of the family but also in the organizational context (Antoni et al., 2020; Liedtka, 1996), especially in family firms where the business domain is strongly influenced by the family domain (Reay et al., 2015; Richards et al., 2019). The need to develop a more fine-grained conceptualization of care in the context of family firms is also reflected in existing studies stressing that caring climates (Duh et al., 2010) and caring relationships are particularly prevalent in this type of organization (Cruz et al., 2010).

The Ethics of Care

The ethics of care perspective is often positioned in contrast to the more commonly known ethical theories based on principles and justice, such as Kantian ethics, which are also collectively referred to as ethics of justice (Held, 2006; Spence, 2016). Held, a leading scholar of the ethics of care perspective, explains the difference as follows: “An ethic of justice focuses on questions of fairness, equality, individual rights, abstract principles, and the consistent application of them. An ethic of care focuses on attentiveness, trust, responsiveness to need, narrative nuance, and cultivating caring relations” (2006, p. 15). The ethics of care is rooted in feminism (Gilligan, 1982; Noddings, 2013; Ruddick, 1995). The founding scholars of the ethics of care perspective perceived the predominant ethical perspectives based on abstract and universal principles (Kohlberg, 1981) as being overly male-oriented and instead emphasized an alternative moral orientation, traditionally applied by (female) caregivers—one that is contextual and relational and that values connections over autonomy (Gilligan, 1982).

The ethics of care was subsequently applied in a business context where scholars emphasized a potential conflict between the traditional perception of for-profit organizations as impersonal, objective and instrumental and the ethics of care, which emphasizes the interconnectedness to and responsibility for particular others (Liedtka, 1996). Despite these promising early works, ethics of care initially only played a niche role in business ethics scholarship (Hamington, 2019). However, more recently, the ethics of care perspective has gained momentum, as evidenced by an increasing number of studies drawing on this ethical perception, such as in the field of social entrepreneurship (André & Pache, 2016), small- and medium-sized enterprises (Spence, 2016), design thinking (Hamington, 2019), ethical consumption (Heath et al., 2016; Shaw et al., 2016), sustainability (Carmeli et al., 2017; Paillé et al., 2016), crisis management (Linsley & Slack, 2013), and coworker relationships (Antoni et al., 2020). The growing application of the ethics of care perspective goes hand in hand with management theorists and business ethicists stressing that recent high profile business scandals have pointed out the limits of rule-based ethical approaches and the need for a relational approach provided by the ethics of care (Hamington, 2019; Hawk, 2011; Koehn, 2011).

SEW-Related Non-financial Goals and Their Relationship to Core Features of the Ethics of Care

Family owners are likely to pursue a range of family-specific non-financial goals to protect and foster their affective endowments in the family firm, referred to as SEW (Gomez-Mejia et al., 2007). Berrone et al. (2012) have significantly enhanced the theoretical construct of SEW by structuring it into five dimensions: renewal of family bonds to the firm through dynastic succession, emotional attachment, binding social ties, family members’ identification with the firm, and family control and influence. These five dimensions of SEW initiated a critical debate (Chua et al., 2015; Miller and Le Breton-Miller, 2014; Schulze & Kellermanns, 2015), and scholars have since proposed various improvements to the original construct and scale development (Debicki et al., 2016; Hauck et al., 2016). We build on these valuable insights when introducing the non-financial goals associated with family owners’ SEW. Crucially, we show that four of the five non-financial goals typically pursued by family owners relate to the core features of the ethics of care and, as a result, are likely to stipulate care-based morality within family firms.

First, many family owners pursue the non-financial goal of renewing family bonds through dynastic succession by handing the firm down to future generations of family members. Indeed, this goal is commonly perceived as a highly central aspect of SEW (Zellweger & Astrachan, 2008; Zellweger et al., 2012). Scholars contend that many family owners have a very strong non-financial desire to ensure transgenerational sustainability because they feel a strong sense of responsibility to future generations of family members (Kets de Vries, 1993) and want to preserve the family dynasty for them (Sirmon & Hitt, 2003).Footnote 2

This goal relates to two core features of the ethics of care perspective. First, the central focus of the ethics of care lies in the compelling moral salience of attending to and meeting the needs of the particular others for whom we take responsibility. Therefore, caring for one’s own offspring is at the forefront of a person’s moral concerns. This is because the ethics of care emphasizes the responsibility to respond to the needs of those dependent on us (Feder Kittay, 1999; Held, 2006). This stands in contrast to the ethics of justice, which is built on the image of independent and autonomous individuals and thus overlooks the reality of human dependence and the morality that is associated with such dependence (Held, 2006).

Moreover, the ethics of justice seeks to avoid bias and arbitrariness so that individuals can strive for impartiality when making ethical decisions. The ethics of care, however, rejects the view that morality needs to be based on abstract reasoning and instead accepts partiality in moral judgements. To most proponents of the ethics of care, the compelling moral claim of the particular other may be valid even when it conflicts with the requirement of the ethics of justice that moral judgements ought to be universalizable (Held, 2006). Moreover, the ethics of justice assumes a conflict between egoistic individual interests on the one hand and universal moral principles on the other. In contrast, the ethics of care suggests that people who care for others are not primarily motivated to pursue their own individual interests, nor do they act for humanity in general. Instead, their interests are intertwined with the persons they care for, and they seek to preserve and promote the relations between themselves and particular others (Benhabib, 1992; Friedman, 1993; Held, 2006). This relates to the family owners’ non-financial goal of ensuring dynastic successions because it explains the wish of parents to promote their own children and their future offspring in the family business context.

Another important non-financial goal of family owners is to enjoy an emotional attachment to their organization and its members. It is argued that because of the blurred boundaries between the family and the firm, emotions of the family system transfer to the firm, affecting the organization’s decision-making (Baron, 2008). These emotions can be positive, such as warmth, tenderness, and happiness, or negative, such as anger, sadness, and disappointment (Epstein et al., 1993). Moreover, emotional attachment to the firm helps family owners maintain a positive sense of self as the organization becomes a place where the needs of belonging, affect and intimacy are fulfilled (Kepner, 1983). Despite the importance of emotions in the context of family firms, they remain vastly understudied within family business research (Berrone et al., 2012), with scholars currently calling for increased attention to this important area of research (De Massis, Eddleston, et al., De Massis, Eddleston, et al., 2020).

The family owners’ goal of cherishing an emotional attachment to the family firm is aligned with the ethics of care because it also values emotions to understand what would be morally best for us to do. Accordingly, emotions such as sympathy, empathy, sensitivity and responsiveness are regarded as moral emotions that help to determine what morality recommends (Held, 2006; Urban Walker, 1998). In contrast, the ethics of justice seeks to rely primarily on reason and rationalistic deductions to avoid feelings that undermine universal moral norms or that allow favouritism to impede impartiality. The ethics of care, however, values emotions because it enables people to understand what would be best given the unique interpersonal context of moral concern (Held, 2006). This is likely to be particularly relevant for family firms, characterized by highly complex and embedded emotional bonds (Fletcher, 2000).

In addition, many family owners seek to foster and protect their binding ties not just to family members but also to other important stakeholders (Miller et al., 2013). Accordingly, family business owners often value time-honoured partners, customers and suppliers (Miller & Le Breton-Miller, 2005). Family firms are said to have a natural incentive to engage in long-term relationships with external stakeholders to accumulate social capital and reserves of goodwill (Carney, 2005; Gomez-Mejia et al., 2011), which will protect them in times of crisis (Godfrey, 2005). Family firms are less driven by short-term results, instead, adopting patient strategies that involve building close relationships with key stakeholders (Miller & Le Breton-Miller, 2005). Importantly, family business owners are often motivated to foster and protect their relationship ties to selected stakeholders even if there is no obvious financial gain associated with doing so (Brickson, 2005, 2007). Accordingly, this non-financial goal relates to the affective value generated by a sense of community and interpersonal solidarity (Hauck et al., 2016).

The goal of fostering and protecting binding ties corresponds to the ethics of care perspective that perceive individuals as relational and interdependent. The ethics of care emphasizes that persons start out as children, are dependent on the care of others, and remain interdependent with others throughout life (Held, 2006). Similar to the non-financial goal of protecting binding ties, the ethics of care holds that our relations are part of what constitutes our identity. However, in line with recent work within the family business literature (Nason et al., 2019), it also acknowledges that people may reshape their relations with others and have the capacity to cultivate new relationships (Held, 2006). Nevertheless, the ethics of care stresses that our responsibility to others is predominantly a result of our embeddedness in familial, social and historical contexts (Held, 2006).

Finally, many family business owners seek to increase the personal identification of family members with the firm. Due to the intermeshing of family and business, the identity of the organization is strongly tied to and influenced by the identity of the family, with many family firms carrying the owners’ name (Berrone et al., 2010; Dyer & Whetten, 2006). As a result, external stakeholders view the firm as an extension of the family (Berrone et al., 2012), and internal stakeholders are likely to experience a corporate culture infused with the owning family’s values and norms.

This goal of family business owners corresponds to the ethics of care, which highlights the private sphere as a territory for morality (Spence, 2016). Proponents of the ethics of care posit that dominant moral theories solely focus on public life, neglecting the moral significance of the private domain of the family (Held, 2006). As such, these theories have constructed morality assuming that individuals are unrelated, mutually indifferent and equal (Darwall, 1983; Gauthier, 1986). However, these assumptions do not hold in the context of the family, where members have unequal power and must accept the ties and obligations that exist involuntarily by being part of the owning family. The ethics of care sheds light on the morality arising in relationships of unequal and dependent individuals and argue that these attributes apply not just in households but also in organizations and society in general. This is particularly true for family firms given the non-financial goal of fostering family firm identification through which the private domain influences the business domain.

To summarize, we postulate that four of five crucial non-financial goals work in conjunction to stipulate a unique approach to morality in family firms, namely, one centred on the ethics of care.

Proposition 1

The non-financial goals of renewing family bonds through dynastic succession, cherishing emotions, protecting binding social ties, and increasing the personal identification of family members with the firm foster care-based morality in family firms.

One of the most distinctive non-financial goals family owners tend to pursue is the wish to exert power and influence over the firm. Indeed, Berrone et al. (2012) argue that the first dimension of SEW constitutes ‘family control and influence’ because the family’s power to control strategic decisions distinguishes family firms (Chua et al., 1999; Schulze et al., 2003). More recently, scholars have emphasized that the motivation to exert control and influence is more affective than conceptualized by Berrone et al. (Hauck et al., 2016). Particularly, these scholars stress that family owners derive affective value from feeling influential and powerful and enjoy the authority related to their powerful positions in the firm (Gomez‐Mejia et al., 2010). Accordingly, research has found that family owners may enjoy being authoritarian leaders (Dyer & Handler, 1994; Kelly et al., 2000) and, above and beyond their power in the business, often exercise authority within their families (Kellermanns & Eddleston, 2004; Tagiuri & Davis, 1992). This dominant position enables such family business leaders to make decisions without consulting others (Tagiuri & Davis, 1992), prevents them from being openly questioned during their reign (Beckhard & Dyer, 1983), and leads to a less participative atmosphere within the organization (Kellermanns & Eddleston, 2004). As such, the goal of exerting power is associated with patriarchal domination within family firms.

We argue that the wish to exert power and influence has a complex relationship with the ethics of care. On the one hand, the ethics of care acknowledges that individuals are in unequal positions of power because the caregiver has power over the care receiver and that caring persons may often need to exercise such power (Held, 2006). Therefore, the notion of power and influence is more legitimized in care-based morality than in justice-based morality, which emphasizes the universal rights, equality, and autonomy of every individual. However, the wish to exert power is also strongly at odds with the ethics of care and its feminist origin that rejects a patriarchal order and its associated domination of the powerful over subordinates (Grosser, 2009). Instead, caregivers should be sensitive to avoid paternalistic domination over the recipients of care and promote the competent but not disconnected autonomy of the people being cared for. It rejects subtle as well as blatant coercion as disrespectful and inconsiderate and stresses that caring should be practised in a post-patriarchal organization that fosters trust and mutuality in place of (benevolent) domination (Held, 2006). To summarize, we propose:

Proposition 2

The non-financial goal of exerting power and influence fosters family members’ patriarchal domination over the firm. As such, it contradicts a care-based morality that, although acknowledging the inequalities and dependencies of caring relationships, rejects the self-interested wish to dominate such relationships.

Care-Based Morality, Quest for Power, and PSE

Care-Based Morality and PSE

In the following section, it is argued that the care-based morality stipulated by the family owners’ non-financial goals promotes PSE.

First, care-based morality aims to meet the needs of others for whom we take responsibility, which likely instils a caring culture within the organization (Hamington, 2019). Although all business relationships are, to some extent, guided by instrumental motives, past research has revealed that the owning family not only cares about its own members but also feels responsible for non-family employees who are dependent on the firm (Duh et al., 2010; Uhlaner et al., 2004). We argue that this is particularly true for family owners who exhibit the wish to protect the firm as a valuable asset for the future generation of family members because these family owners are likely to experience the compelling urge to care for their dependents. The most important dependents are likely to derive from the owning family itself. However, the feeling of responsibility for particular others often also transcends the family boundary and likely instils a caring culture towards nonfamily employees who often have a close and long-term relationship with the family owners (Uhlaner et al., 2004).

Scholars who explore the role of care ethics in corporate culture highlight the need to internalize the responsibility for care within the organization (Hamington, 2019; Liedtka, 1996). Accordingly, the firm should be led by managers who openly speak of care and have systems in place that foster care. Importantly, however, a healthy caring environment promotes employees’ understanding that although the organization provides care for them, they should be empowered to take care of themselves and others (Oliner & Oliner, 1995). As such, a caring culture respects employees and exhibits trust, helping behaviours, lenience, courage and mentorship (von Krogh et al., 2000). Caring matters for moral, ethical and social reasons and hypercompetitiveness among employees, promoted by many conventional human resource practices, is antithetical to the caring culture that enables prosocial benefits (von Krogh et al., 2000).

Family firm research is full of evidence of such caring cultures within family-owned businesses. For instance, research has found that family firms have cultures of high commitment to employees (Duh et al., 2010), implement ‘care-oriented’ contracts that exhibit a high degree of genuine concern for nonfamily employees (Cruz et al., 2010), provide more stable employment (Block, 2010; Stavrou et al., 2007), strive to be responsible employers (Astrachan Binz et al., 2017; Zellweger & Nason, 2008), encourage employees to be their best (Moscetello, 1990) and perceive nonfamily employees as part of the extended family (Uhlaner et al., 2004).

Second, care-based morality’s focus on emotions likely promotes empathy and compassion. The positive consideration of emotions, such as empathy and compassion, is an important feature of the ethics of care (Slote, 2007) that distinguishes this ethical perspective from the ethics of justice with its objectivist moral approach (Hamington, 2019). Noddings (2010, p. 9) describes empathy as an important step in the process of providing care: “As we listen to the other, we identify her feelings; we begin to understand what she is going through. As a result, we feel something. When what we feel is close to what the other is expressing, we may say that we are experiencing empathy. This experience leads to motivational displacement. We put aside our own goals and purposes temporarily to assist in satisfying the expressed needs of the other; our motive energy flows toward the purposes or needs of the other. This is the basic chain of events in caring”. Accordingly, the ethics of care stresses that factual knowledge of a concern, although informative, might not necessarily lead to a caring action. Empathy, however, is likely to provide the emotional motivation to act and meet the needs of the other (Hamington, 2019). In our context, we argue that the goal of fostering family members’ emotional attachment to the organization and its members will increase the level of empathy in the family firm, promoting PSE.

Relatedly, research has found that family firms possess higher levels of empathy, warmth and zeal (Payne et al., 2011). Such virtuous emotions likely explain why owning family members often act unselfishly with each other and towards external stakeholders (Brickson, 2005, 2007). When family members feel empathy, they are more likely to proactively engage with stakeholders, not because it makes economic sense but because it is ‘the right thing to do’ and because any adverse effects would feel like harming ‘one of ourselves’ (Cennamo et al., 2012).

Third, the care-based morality’s view of individuals as relational and interdependent fosters collaboration with external stakeholders such as competitors, suppliers and clients. Instead of conflicting competition, which is at odds with the ethics of care, owner-managers often enjoy a sense of camaraderie with their competitors, which instils a feeling of moral responsibility to their peers (Spence, 2016; Spence et al., 2001). In keeping with the ethics of care, such moral concern for competitors likely leads to ‘coopetition’ (Nalebuff et al., 1996) over conflicting rivalry (Wicks et al., 1994). Feminist scholars have long stressed that rampant competitive individualism fails to acknowledge the complexity and fragility of the world. Companies should, therefore, not be portrayed as autonomous actors but as embedded in a web of fundamental ties. Placing more emphasis on those ties enables organizations to take responsibility for all their actions, which affects stakeholders, even if there is no legal requirement to do so (Wicks et al., 1994). Accordingly, we argue that the wish to foster binding ties to important firm stakeholders likely increases PSE.

Research has found that family firms tend to form closer and more enduring relationships, which goes against the opportunistic, transactional short-termism that hinders organizations’ PSE (Jamali & Mirshak, 2007; Le Breton-Miller & Miller, 2016). Indeed, scholars have argued that family firms are hesitant to change long-standing suppliers in industries characterized by social concerns because over the years of collaboration, they have developed a strong sense of responsibility for them (Richards et al., 2017). By engaging in long-term relationships, family firms gain more in-depth knowledge of their stakeholders. Care ethicists argue that knowledge and care are intermingled because people and organizations cannot care for something or someone they only possess superficial knowledge of (Hamington, 2019). Relatedly, family business research has argued that family firms are often deeply rooted in their communities (Cennamo et al., 2012), which likely motivates them to engage with more loosely connected stakeholders that are not part of their organization (Laguir et al., 2016; Westley & Vredenburg, 1991).

Finally, care-based morality’s focus on the private sphere to ascertain what is morally desirable likely affects family firms’ PSE. In line with existing research, we argue that this feature of the ethics of care perspective is especially relevant if individuals’ private self-identification is tied to the organization and vice versa (Spence, 2016). This is particularly true in family firms because family owners often seek to increase their personal identification with the firm (Berrone et al., 2012). As a result, family and firm dynamics are highly interconnected (Aldrich & Cliff, 2003). Indeed, extant family business research has shown that the firm often reflects the owning family’s self-concept (Kepner, 1983). As such, the organization is a reflection of the family’s core values, beliefs and norms (Cennamo et al., 2012). Due to this substantial influence of the private sphere on the family firm, family owners are likely to be proactive when engaging with stakeholders because prosocial actions are a way to uphold family values and principles (Cennamo et al., 2012). Indeed, scholars have argued that in addition to the instrumental motive of protecting and enhancing the family firm’s reputation by engaging in PSE, family owners are also likely to be normatively interested in promoting stakeholder relationships. This is because family owners are not faceless shareholders but instead are often closely identified with the firm’s activities (Gomez-Mejia et al., 2011). To summarize, we propose:

Proposition 3

Care-based morality promotes family firms’ PSE.

The Quest for Power

Having outlined the positive effects of care-based morality on family firms’ PSE, we now explain how one of the five SEW-related non-financial goals often pursued by family owners—the desire to exert power and influence—interacts with care-based morality to harm PSE.

We postulate that the non-financial goal of exerting power interacts with care ethics’ aim to meet the needs of others for whom we take responsibility. More specifically, we argue that the goal of exerting power and influence will entice family owners to strongly favour kin over nonkin when dealing with competing caring needs and responsibilities. This will particularly harm nonfamily employees, who are in many ways dependent on the organization and its owners. Care ethicists have unveiled the dilemma of allocating care and managing competing responsibilities (Antoni et al., 2020). As Tronto describes, “in general, caring will always create moral dilemmas because the needs for care are infinite” (1993, p. 137). More recently, scholars have highlighted how individuals struggle with the competition of care in the workplace (Antoni et al., 2020). Building on these insights, we predict that the goal of exerting power and influence will motivate family owners to disproportionately allocate care to family members, disadvantaging other stakeholders, notably nonfamily employees. In line with our reasoning, research has found that family owners who seek to extend their power and influence over the firm are more likely to employ family members over nonfamily members even if the former are unqualified (Chua et al., 2009) and engage in the scapegoating of nonfamily employees (Gomez-Mejia et al., 2003). This asymmetry in the allocation of care between family and nonfamily members hinders responsible employee practices, which typically expect fair treatment of the workforce and equal opportunities for all employees (Cruz et al., 2014). Indeed, the quest for impartiality and equality are core features of the ethics of justice. However, the ethics of care accepts partiality and therefore legitimizes the unique treatment of family members, which is spurred on by the goal of fostering the family’s power and influence over the organization.

At this point, it is important to note that the goal of particularly attending to the needs of next-generation family members is not always associated with negative consequences for nonfamily stakeholders. Indeed, research has found that concern for the succeeding generation can actually promote social practices because it fosters forward-looking behaviour (Delmas & Gergaud, 2014). Accordingly, if the goal to pass on the company legacy to descendants is pronounced, long-term caring relationships with employees might be promoted to accumulate social capital (Carney, 2005; Cennamo et al., 2012). However, if family owners are driven by power motives, they might become overly focused on ensuring that future generations claim dominant positions in the family firm and society in general, harming other stakeholders. Aligned with this reasoning, family firms have been found to maximize profits to promote transgenerational wealth accumulation, which renders future generations more powerful and influential instead of sharing excess wealth with nonfamily employees (Astrachan & Jaskiewicz, 2008; Astrachan Binz et al., 2017; Habbershon et al., 2003).

In addition, we expect the non-financial goal of exerting power and influence to interact with the care ethics’ focus on emotions. More specifically, we argue that the quest for power turns the family owner-manager’s emotional concern into benevolent domination over other family members and nonfamily employees. This reasoning is in line with care ethicists acknowledging that even helpful emotions can become misguided and that empathy and compassion can cross over into controlling dominance (Held, 2006).Footnote 3 In line with this argument, research has highlighted that family owners’ goal of exerting power within the organization is at odds with modern employee practices, which emphasize empowerment, autonomy and participation (Green, 2008; Zientara, 2014). Granting nonfamily members discretion over how they perform their work and allowing them to participate in decision-making expands employees’ freedom in the workplace (Zientara, 2017). Such work practices are characterized by trust and mutuality rather than benevolent coercion. The latter, although driven by well-meaning, paternalistic concern for subordinates, impedes good caring relationships (Held, 2006). Accordingly, family owners who are driven by power motives are likely to centralize decision-making at the helm of the company and exercise top-down control over the firm and its internal stakeholders, harming employees’ satisfaction and commitment (Zientara, 2017). Moreover, the benevolent domination of the controlling owner-manager might also harm other family members. For example, compassionate concern for next-generation family members, coupled with power motives, might lead owner-managers to coerce young family members into joining the firm (Freudenberger et al., 1989) because they believe that a career in the family firm would not only increase family influence but also be beneficial to the offspring. As a result, next-generation family members might feel locked into the family firm (Schulze et al., 2001), which likely leads to frustration and emotional pain among family members (Kellermanns et al., 2012). In particular, family members might feel suffocated by the omnipresent benevolent care of the head of the family and the firm, who pressures them into aligning with his or her aspirations for them, irrespective of personal preferences (Schulze et al., 2001).

Next, we postulate that the non-financial goal of exerting power and influence interacts with the ethics of care view of individuals as relational and interdependent. In particular, we hold that when family owners’ quest for power and influence is pronounced, a high degree of group cohesion among business partners and competitors might generate negative consequences for other societal stakeholders. Accordingly, the family’s goal of exerting power and influence over the industry might foster the mentality of ‘us against them’ (cf. Gordon & Nicholson, 2008; Kidwell, 2008) that places the needs of the tight-knit group of business partners over those of other stakeholders. The outcome of such a mentality might be collusion, favouritism and the perpetuation of exclusive clubs that harm industry stakeholders and society at large. Family owners who cherish their position of power are likely to exploit their authority to help others to whom they feel connected, furthering the preservation of business elites and socialization into a capitalist class (Nason et al., 2019), cementing social inequality. Indeed, extant research has shown that family firms often greatly distrust whom they perceive as outsiders (Fukuyama, 1995) and that high levels of group cohesion can spur deviant behaviour (Kellermanns et al., 2012; Warren, 2003) to the detriment of external stakeholders.

Finally, we posit that the non-financial goal of exerting power and influence interacts with the care ethic’s focus on the private sphere to ascertain what is morally desirable. We argue that if the family business owners’ quest for power and authority is high, it is likely not limited to the firm but also inherent to family dynamics (Kellermanns & Eddleston, 2004), given the intermeshed identity of the family owners and the business. Power inequalities in the family system traditionally put women in disadvantaged positions. Feminist scholars, including care ethicists, emphasize the longstanding gender inequalities within the familial system and criticize the often unquestioned power men possess ‘in the castle of their homes’ (Held, 2006).

If family owner-managers pursue the goal of exerting power and influence, such patriarchal family values are likely to exist in the individual family and invade the business sphere, leading to discriminatory practices against women above and beyond the average level of gender inequality prevailing in the workplace.Footnote 4 Indeed, extant research has highlighted such discriminatory practices within family firms (Campopiano et al., 2017; Martinez Jimenez, 2009). For instance, studies have shown that women’s contributions to family firms often remain unacknowledged due to traditional values that put women and men in different social positions (Rowe & Hong, 2000). Similarly, rigid traditional gender roles within the owning family often prevent women from joining the family firm (Rothausen, 2009), and intrafamily succession is more likely to take place if the current owner-manager has a son (Ahrens et al., 2015) because a male successor is usually preferred over a female candidate (Glover, 2014). Importantly, this gender inequality does not necessarily derive from ill-intentioned discrimination against women but is instead the outcome of the patriarch’s care for family members, coupled with the goal of exercising authority over and controlling family dynamics. Accordingly, the patriarch might wish to reduce the perceived work-family conflict (cf., Vera & Dean, 2005) of female family members by avoiding having them struggle to raise a family while working hard in the business (Cadieux et al., 2002; Cole, 1997), which preserves the traditional family set up with its inherent discrimination of women.

To summarize, we argue that the family owners’ goal of exerting power and influence interacts with every core feature of care-based morality to lower PSE. Thus, we propose:

Proposition 4

The non-financial goal of exerting power and influence interacts with care-based morality to lower family firms’ PSE.

An overview of the family owners’ SEW-related non-financial goals, their relationships to core features of the ethics of care and the effects on firm PSE is depicted in Table 1.

The Role of Female Family Directors

Family owners’ non-financial goal of exerting power and influence interacts with care-based morality to harm firms’ stakeholders, as conceptualized in the preceding text. However, we argue that this negative interaction effect of the family’s power motive can be tempered by female family involvement. The reasons to focus on the role of female family directors are twofold. First, the ethics of care is rooted in feminism (Gilligan, 1982; Noddings, 2013; Tronto, 1993). Feminist scholarship typically involves a critical inquiry into gender domination and subordination (Allen, 2009; Karam & Jamali, 2017). In fact, the ethics of care perspective was developed as a feminist alternative to predominant ethical perspectives, which were perceived as overly male-oriented (Gilligan, 1982). Feminist scholarship argues that organizations reproduce patriarchal systems of gender relations. Involving women in leadership positions helps to change these systems by valuing women’s differences, notably their relational skills and empathy (Grosser & Moon, 2019). The ethics of care has been particularly fruitful in this scholarly inquiry, as this perspective has facilitated a change in the gendered status quo by underscoring the importance of relational activities for organizations, which are typically associated with female values (Grosser & Moon, 2019).Footnote 5 Second, women are still underrepresented in top positions in family firms, in which gendered norms and roles often impede female succession into leadership roles (Glover, 2014; Overbeke et al., 2013; Rothausen, 2009).However, there is an increasing awareness of this inequality and a growing interest in female family successions, both from academia (see Campopiano et al., 2017 for an overview) and from business practice (Forbes, 2015; PwC, 2016).

Female Family Involvement and the Goal of Exerting Power and Influence

In general, female involvement on boards of directors tends to enhance a firm’s CSR (Boulouta, 2013; Cruz et al., 2019). However, initial evidence on female directors who are also part of the owning family is mixed and seems to reveal a complex relationship with CSR. Accordingly, one study finds that family internal female directors do not increase CSR (Campopiano et al., 2019), whereas another study shows that internal family directors are particularly effective in increasing CSR if they also hold a managerial position in the firm (Cruz et al., 2019). Adding to these important insights, we argue that female family members’ involvement on boards of directors lessens the negative effect of the family’s goal of exerting power in combination with care-based morality on firms’ PSE.

Accordingly, we postulate that female family members are likely to lessen the asymmetry in the allocation of care between family and nonfamily members, which derives from the interplay of the owners’ power motives and their care-based morality. Women are found to be more ‘communal’ than men (Eagly, 2005). This implies that female family directors—although compelled to satisfy the needs of family members and secure dynastic succession—are more likely to feel a strong sense of responsibility for the entire organizational community, which encompasses all employees, irrespective of their family status. Moreover, women tend to be less tolerant of ethical compromises (Kennedy & Kray, 2014). As such, they are more likely to experience the pressing dilemma of allocating care (Tronto, 1993) in a way that does not compromise their ethical beliefs. It follows that women are less likely to disproportionally attend to familial demands at the expense of other firm-internal stakeholders—even if they share the family’s goal of securing family influence—because doing so would clash with their moral values. This argument is in line with initial empirical findings that female family members, despite being committed to the family and its non-financial goals, indeed ‘humanize the workplace’ (Cruz et al., 2019; Edlund, 1992). More specifically, a recent study shows that the presence of female family directors benefits employees, whereas family ownership per se had a negative effect on employees (Cruz et al., 2019).

In addition, female family directors might lower the risk that the caring concern of the owning family turns into benevolent dominance due to power motives. Women tend to have more participative decision-making styles than men (Konrad et al., 2008), who tend to be more authoritarian. As such, female directors, even if part of the owning family, are more likely to collaborate and consult with nonfamily members in the decision-making process, enhancing employee satisfaction and commitment. Within the family, female family directors might assist other family members in voicing their concerns in the presence of a paternalistic head of the family. Relatedly, the family business literature has long emphasized the important role of women as mediators who seek peace and harmony between family members and thus act as ‘chief emotional officers’ of family firms (Ward, 1987). This is because women are more likely to express others’ emotions (Cross et al., 2011) and to nurture relationships (Campopiano et al., 2019) rather than dominate them.

Moreover, female family members are likely to reduce the risk of collusion and the perpetuation of exclusive clubs with external stakeholders, which arise through the interplay of the family’s care-based morality and its quest for power. Female family directors are likely to bring different perspectives and nontraditional professional experiences to the table (Singh et al., 2008). As a result, they are likely to form new connections between the firm and external stakeholders, which deters favouritism. In fact, existing studies have highlighted that female family directors often feel challenged by the masculine environment prevailing in many family firms (Campopiano et al., 2017) and, as a result, often establish new networks with other successful women (Lyman et al., 1985), combatting the perpetuation of incestuous business relationships that harm outside stakeholders.

Finally, appointing female family members as directors helps tackle gender discrimination in family firms that derives from traditional power inequalities within the family system and the intermeshing of family and business dynamics. Women in family firms have traditionally played roles related to the family sphere, such as spouses or mothers (Martinez Jimenez, 2009). Interestingly, the ethics of care perspective has been criticized within feminist literature for reinforcing the stereotypical image of women as selfless nurturers who are responsible for all caring work (Held, 2006). However, having female members of the family in strategic positions reduces such unequal role allocations based on gender and advances gender diversity (Burke, 1994; Cruz et al., 2019). Moreover, female family directors are likely to address discriminatory firm practices during board meetings and hence act as modest forces to change the patriarchal values that often persist within family firms, benefitting the morale and retention of female employees irrespective of their family status (Burke, 1994; Cruz et al., 2019). To summarize, we propose:

Proposition 5

Female family directors weaken the negative interaction effect of the non-financial goal of exerting power and care-based morality on family firms’ PSE.

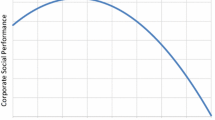

Our overall conceptual model is depicted in Fig. 1.

Discussion

This conceptual study introduces the ethics of care perspective to family business research. It highlights that the SEW-related non-financial goals often pursued by family members either stipulate or interact with care-based morality, affecting PSE in family firms. We believe that a more in-depth evaluation of care in the context of family firms is important and timely, not least because the current pandemic has called into question scholars’ reliance on economic assumptions about individuals as purely self-interested actors. Instead, as we are reminded to care for one another, the act of caring, its relationships and responsibilities seem of central importance, having been neglected in favour of competition and financial performance in the business context. Inherent in this shift of perspective lies the realization that it is not only about financial outcomes but also, first and foremost, about the safety and wellbeing of all stakeholders, emphasizing social firm outcomes, such as PSE, rather than purely economic ones. Against this backdrop, this study seeks to contribute to a better acknowledgement of the non-financial goals and outcomes of organizations. Doing so seems particularly relevant for family firms whose owners are understood as pursuing a set of distinct non-financial goals that, as argued in this study, foster care within the organization. However, we also caution scholars to be mindful of family owners’ power motivations, as patriarchal domination unleashes the dark side of care, which needs to be better understood if we are to promote care over rules and regulations. This study offers a novel conceptualization of care and power in the context of family firms and, in particular, contributes to three strands of current research.

Contribution to Literature on Corporate Social Responsibility of Family Firms

Recently, scholars have highlighted that research at the intersection of business ethics and family firms has, overall, been scarce (Vazquez, 2018). Moreover, while there is a general consensus that family owners increase the environmental performance of firms (Berrone et al., 2010; Cruz et al., 2014), the effect of family ownership on the firm’s stakeholders remains inconclusive. For instance, many scholars highlight the positive effect of family ownership on nonfamily employees (Astrachan Binz et al., 2017; Block, 2010; Duh et al., 2010), but others contrarily argue for negative effects (Cruz et al., 2014; Neckebrouck et al., 2018). Finally, the majority of studies suggest that family owners seek to engage in ethical behaviour (Astrachan et al., 2020; Marques et al., 2014), whereas the dark side of family ownership (Kellermanns et al., 2012) is often only discussed at the fringes of CSR research and lacks a more in-depth and structured exploration. To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to theorize about both the good and bad stakeholder outcomes of family ownership under the umbrella of one theoretical lens. In doing so, we build on the previous insight that SEW might be a double-edged sword in regard to CSR (Cruz et al., 2014) by conceptualizing when and why the same non-financial goals that promote PSE also hinder it, explaining the inconclusive findings of existing scholarship.

Moreover, we add to recent insights into the role of female family directors in CSR, which thus far has generated mixed findings, revealing the role of power (Cruz et al., 2019) and self-construal (Campopiano et al., 2019). Interestingly, however, as noted in a recent literature overview, there is a dearth of studies drawing on the goal literature to explain the role of female involvement (Campopiano et al., 2017). Our research contributes to filling this gap by highlighting that female family directors play a crucial role in ensuring that the non-financial goals of the family promote, instead of inhibit PSE.

Contribution to Literature on Goals in the Context of Family Firms

The goals of family owners are perceived as a cornerstone to understand the behaviour and performance of family firms (Chrisman et al., 2012). Most studies within this literature have used a trade-off perspective when exploring different goals of family firms and their effects on firm outcomes (Vazquez & Rocha, 2018), usually stressing goal conflicts and competing reference points (e.g., Gomez-Mejia et al., 2007; Minichilli et al., 2014; Sciascia et al., 2015). We expand these theoretical insights by revealing the additive and interactive effects of the various non-financial goals pursued by the family that need to be better accounted for (Greve, 2008; Kotlar et al., 2018). More specifically, we highlight additive effects by arguing how four central non-financial goals of family owners jointly stipulate care-based morality, which, in its pure form, increases PSE. However, we also reveal interactive effects by arguing that one of the five SEW-related non-financial goals, namely, the goal of exerting power, interacts with the goals behind care-based morality to generate stakeholder concerns. Interestingly, in the context of our study, there is no goal conflict, as predominantly assumed in the existing literature (Vazquez & Rocha, 2018). However, the combination of certain goals, while aligned, still shifts the firm’s stakeholder engagement from being positive to negative.

Moreover, we respond to the recent call to go beyond agency theory in the family firm goals literature (Vazquez & Rocha, 2018). Research on family involvement in firms has predominantly drawn on agency theory, assuming self-interested individuals. Accordingly, scholars have argued that family successors exploit their parents’ altruism by engaging in self-serving behaviour such as free riding or shirking (Schulze et al., 2001, 2003). However, such theoretical arguments contradict the ethics of care because it holds that the characteristic stance of a person is neither egoistic nor altruistic but that people in caring relationships are acting for self and particular others together (Held, 2006). As such, the ethics of care could serve as an alternative theoretical lens to stewardship theory, which has recently been criticized for its ambiguity related to the theoretical mechanisms that engender stewardship (Neckebrouck et al., 2018). The ethics of care perspective seems to be a particularly promising lens to advance the organizational goal literature because various non-financial goals discussed in that literature are closely related to key features of the ethics of care, as emphasized in this conceptual study.

Our research also contributes to literature on socioemotional wealth. Although a vast body of research has drawn on SEW (e.g., Deephouse & Jaskiewicz, 2013; Minichilli et al., 2014; Strike et al., 2015) it is still not fully established whether the construct is uni- or multidimensional (Brigham & Payne, 2019). If uni-dimensionality is assumed the latent construct only exists if all or most sub-dimensions are present. However if SEW is conceptualized as being multi-dimensional, it exists as a group of independent dimensions (Brigham & Payne, 2019). This distinction is important in the context of CSR. Past research, indirectly assuming multi-dimensionality, has argued that SEW promotes an instrumental and selective approach to CSR to achieve specific SEW goals rather than engaging in a “whole business view of responsibility” (Zientara, 2017, p. 185). We counter this conceptualization by showing how multiple SEW dimensions jointly relate to the ethics of care and thus indeed promote a whole business view of CSR. However, we also uncover the complex relationship between one dimension of SEW, namely family power and influence, and the ethics of care. Accordingly, we highlight that this SEW dimension plays a different and particularly critical role with regards to PSE. Outlining this SEW dimension in our study we considered the work of Hauck et al. (2016) who argue that the original conceptualization of this dimension labelled ‘family control and influence’ (Berrone et al., 2012) lacked insights into the affective value for family owners. Accordingly, they proposed to alter this dimension to acknowledge the affective desire of feeling influential and powerful (Hauck et al., 2016) and the enjoyment of exerting authority (Gomez‐Mejia et al., 2010). Acting upon those suggestions, we labelled the related non-financial incentive as goal to ‘exert power and influence’ and argue that this goal acts as hinge that defines whether the goals related to the remaining SEW dimensions produce positive or negative stakeholder effects.

Contribution to Literature on the Ethics of Care

Finally, we contribute to existing scholarship drawing on an ethics of care perspective in the organizational context (e.g., Antoni et al., 2020; Carmeli et al., 2017; Hamington, 2019). Specifically, we respond to a recent call to apply an ethics of care lens to family firms (Spence, 2016), the most prevalent form of organizations worldwide (La Porta et al., 1999). Our insights on family firms correspond to recent scholarship proposing that the ethics of care is a fitting lens to study CSR of small and medium sized firms (Spence, 2016). We add to this line of inquiry by explaining how distinctive non-financial goals pursued by the owing family instil an ethics of care. However, we also caution that there are potential risks associated with fully embracing the ethics of care, particularly if seen as an exclusive alternative to the ethics of justice. More specifically, we emphasize that if the care giver pursues power motives, core features of the ethics of care—the fact that it accepts partiality, acknowledges human dependence and embraces emotions—can lead to patriarchal dominance, risking the protection of universal rights and individuals’ equality, as promoted by the ethics of justice. We believe that recent applications of the ethics of care in an organizational context has not emphasized this risk sufficiently and instead focus extensively on the pro-social effects of the ethics of care. However, as Held (2006) notes, the ethics of care is best applied in a post-patriarchal society, which is not reflective of our current organizational landscape. Future research on care ethics needs to be mindful of and further investigate power motives and structures in the organizational context.

Limitations and Future Research

Our conceptual work is not free of limitations, which present an opportunity for future research. First this conceptual study assumes that the five goals related to the FIBER dimensions of SEW (Berrone et al., 2012) are the most important and distinctive non-financial goals of family business owners. However, the FIBER conceptualization, whilst highly influential in family business research has also been criticized on various grounds (Miller and Le Breton-Miller, 2014), with scholars demanding a “finer grained characterizations of the components of SEW” (Chua et al., 2015, p. 180). We have acted on some of these criticisms by reframing the goal of exerting power and influence according to recent suggestions (Hauck et al., 2016). However, the antecedents of non-financial goals associated with SEW (Debicki et al., 2016; Williams et al., 2018) are beyond the scope of this conceptual paper. Recently, researchers have stressed that SEW might become reified implying that the construct will be taken for granted (Jiang et al., 2018; Schulze & Kellermanns, 2015). To avoid this pitfall, future research should explore the underlying assumptions and antecedents of SEW in more detail. Moreover, it would be interesting to investigate family members’ heterogeneity with regards to non-financial goals and to explore how such heterogeneity affects the conceptual model presented in this paper. Furthermore, this study centers on family derived, non-financial goals. Recently, scholars have provided valuable insights by distinguishing between family owners’ financial and non-financial goals as well as between family and business goals (Astrachan Binz et al., 2017). Extending our conceptual model by exploring the role of those remaining goal categories might be a promising avenue for future research.

Second, the ethics of care is a contextual perspective, focusing on the uniqueness of caring relationships with particular others. However, our theoretical paper highlights the relationship of non-financial goals and the ethics of care in more general terms, which helps to explain PSE in family firms and is in line with existing work on care ethics in organizations (e.g., Spence, 2016). Nevertheless, we encourage future research to place more emphasis on the individual context, by zooming in on the caring relationships prevailing in business owning families. Such insights are needed because the ethics of care emphasizes that the private sphere influences public life in general (Held, 2006) and the organizational context in particular (e.g. Spence, 2016).

Third, we stress the salient role of the family’s goal of exerting power and influence. Future research should add to these conceptual insights by further investigating the role of power in the context of family firms. Care ethics, with its feminist roots, opposes patriarchal domination but family ownership often seems to be associated with traditional authority structures and power motivations. We highlight how such motivations interfere with the ethics of care to the detriment of various stakeholders and invite future research to deepen our insights.

Relatedly, it would be interesting for future research to explore possible combinations of care and justice-based ethics in business practice. Most proponents of the ethics of care acknowledge that a focus on caring relationships alone is not sufficient to solve all ethical issues (Held, 2006; Moller Okin, 1989). Future research could explore to what extent business reality is shaped by justice and care and explore potential trade-offs between these two ethical perspectives.

Notes

“Affective endowments” or “Socioemotional Wealth (SEW)” refer to the nonfinancial utility that family business owners derive from their firms. These endowments relate to family owners binding ties to stakeholders (1), their identification (2) and emotional attachment (3) to the firm, and their current (4) and future (5) influence over the business. These five key dimensions of SEW both stipulate and derive from family-centered, nonfinancial goals (Berrone et al., 2012; Debicki et al., 2016). Accordingly, family owners typically pursue nonfinancial goals, next to financial goals, which seek to preserve and enhance their SEW (Berrone et al., 2012). As such, SEW typically describes the family’s present endowments, whereas nonfinancial goals represent family owners’ future-oriented incentives.

It is important to note that the nonfinancial goal to renew family bonds through dynastic succession by handing the firm down to future generations of family members might be culturally bounded. This implies that this wish for transgenerational sustainability might be more pronounced in some countries than in others.

Benevolent domination arises when excessive empathy and concern leads to controlling and coercive practices. Good caring relations avoid subtle as well as blatant coercion. Care givers should foster trust and mutuality instead of benevolent domination (Held, 2006).

Patriarchal family values coupled with the owner’s goal of exerting power and influence over the firm may promote coercive practices against employees in general, irrespective of their gender. However, given traditional gender norms prevailing in many households, women are particularly at risk of being discriminated against.

Some feminist writers caution that overstating stereotypical female traits might increase discriminatory practices against women (Fletcher, 1994; Grosser and Moon, 2019) Relatedly, entrepreneurship research has highlighted that investors are not biased against women as such, but against feminine-stereotyped behaviours, irrespective of the entrepreneurs’ sex (Balachandra et al., 2019).

References

Ahrens, J.-P., Landmann, A., & Woywode, M. (2015). Gender preferences in the CEO successions of family firms: Family characteristics and human capital of the successor. Journal of Family Business Strategy, 6(2), 86–103.

Aldrich, H. E., & Cliff, J. E. (2003). The pervasive effects of family on entrepreneurship: Toward a family embeddedness perspective. Journal of Business Venturing, 18(5), 573–596.

Allen, A. (2009). Gender and power. In S. Clegg & M. Haugaard (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of power (pp. 293–310). London.

André, K., & Pache, A.-C. (2016). From caring entrepreneur to caring enterprise: Addressing the ethical challenges of scaling up social enterprises. Journal of Business Ethics, 133(4), 659–675.

Antoni, A., Reinecke, J., & Fotaki, M. (2020). Caring or not caring for coworkers? An empirical exploration of the dilemma of care allocation in the workplace. Business Ethics Quarterly, In Press.

Astrachan Binz, C., Ferguson, K. E., Pieper, T. M., & Astrachan, J. H. (2017). Family business goals, corporate citizenship behaviour and firm performance: Disentangling the connections. International Journal of Management and Enterprise Development, 16(1–2), 34–56.

Astrachan, J. H., Astrachan, C. B., Campopiano, G., & Baù, M. (2020). Values, spirituality and religion: Family business and the roots of sustainable ethical behavior. Journal of Business Ethics, In Press.

Astrachan, J. H., & Jaskiewicz, P. (2008). Emotional returns and emotional costs in privately held family businesses: Advancing traditional business valuation. Family Business Review, 21(2), 139–149.

Balachandra, L., Briggs, T., Eddleston, K., & Brush, C. (2019). Don’t pitch like a girl!: How gender stereotypes influence investor decisions. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 43(1), 116–137.

Baron, R. A. (2008). The role of affect in the entrepreneurial process. Academy of Management Review, 33(2), 328–340.

Beckhard, R., & Dyer, J. W. G. (1983). Managing continuity in the family-owned business. Organizational Dynamics, 12(1), 5–12.

Benhabib, S. (1992). Situating the self: Gender, community, and postmodernism in contemporary ethics (p. 1992). Routledge.

Berrone, P., Cruz, C., & Gomez-Mejia, L. R. (2012). Socioemotional wealth in family firms: Theoretical dimensions, assessment approaches, and agenda for future research. Family Business Review, 25(3), 258–279.

Berrone, P., Cruz, C., Gomez-Mejia, L. R., & Larraza-Kintana, M. (2010). Socioemotional wealth and corporate responses to institutional pressures: Do family-controlled firms pollute less? Administrative Science Quarterly, 55(1), 82–113.

Block, J. (2010). Family management, family ownership, and downsizing: Evidence from S&P 500 firms. Family Business Review, 23(2), 109–130.

Boulouta, I. (2013). Hidden connections: The link between board gender diversity and corporate social performance. Journal of Business Ethics, 113(2), 185–197.

Brickson, S. L. (2005). Organizational identity orientation: Forging a link between organizational identity and organizations’ relations with stakeholders. Administrative Science Quarterly, 50(4), 576–609.

Brickson, S. L. (2007). Organizational identity orientation: The genesis of the role of the firm and distinct forms of social value. Academy of Management Review, 32(3), 864–888.

Brigham, K. H., & Payne, G. T. (2019). Socioemotional Wealth (SEW): Questions on construct validity. Family Business Review, 32(4), 326–329.

Burke, R. J. (1994). Women on corporate boards of directors: Views of Canadian Chief Executive Officers. Women in Management Review, 9(5), 3–10.

Cadieux, L., Lorrain, J., & Hugron, P. (2002). Succession in women-owned family businesses: A case study. Family Business Review, 15(1), 17–30.

Campopiano, G., De Massis, A., Rinaldi, F. R., & Sciascia, S. (2017). Women’s involvement in family firms: Progress and challenges for future research. Journal of Family Business Strategy, 8(4), 200–212.

Campopiano, G., Rinaldi, F. R., Sciascia, S., & De Massis, A. (2019). Family and non-family women on the board of directors: Effects on corporate citizenship behavior in family-controlled fashion firms. Journal of Cleaner Production, 214, 41–51.

Carmeli, A., Brammer, S., Gomes, E., & Tarba, S. Y. (2017). An organizational ethic of care and employee involvement in sustainability-related behaviors: A social identity perspective. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 38(9), 1380–1395.

Carney, M. (2005). Corporate governance and competitive advantage in family-controlled firms. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 29(3), 249–265.

Carney, M., Duran, P., Van Essen, M., & Shapiro, D. (2017). Family firms, internationalization, and national competitiveness: Does family firm prevalence matter? Journal of Family Business Strategy, 8(3), 123–136.

Cennamo, C., Berrone, P., Cruz, C., & Gomez-Mejia, L. R. (2012). Socioemotional wealth and proactive stakeholder engagement: Why family–controlled firms care more about their stakeholders. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 36(6), 1153–1173.

Chrisman, J. J., Chua, J. H., Pearson, A. W., & Barnett, T. (2012). Family involvement, family influence, and family–centered non–economic goals in small firms. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 36(2), 267–293.

Chua, J. H., Chrisman, J. J., & Bergiel, E. B. (2009). An agency theoretic analysis of the professionalized family firm. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 33(2), 355–372.

Chua, J. H., Chrisman, J. J., & De Massis, A. (2015). A closer look at socioemotional wealth: Its flows, stocks, and prospects for moving forward. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 39(2), 173–182.

Chua, J. H., Chrisman, J. J., De Massis, A., & Wang, H. (2018). Reflections on family firm goals and the assessment of performance. Journal of Family Business Strategy, 9(2), 107–113.

Chua, J. H., Chrisman, J. J., & Sharma, P. (1999). Defining the family business by behavior. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 23(4), 19–39.

Chua, J. H., Chrisman, J. J., Steier, L. P., & Rau, S. B. (2012). Sources of heterogeneity in family firms: An introduction. SAGE Publications.

Cole, P. M. (1997). Women in family business. Family Business Review, 10(4), 353–371.

Cross, S. E., Hardin, E. E., & Gercek-Swing, B. (2011). The what, how, why, and where of self-construal. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 15(2), 142–179.