Abstract

Multi-stakeholder initiatives (MSIs) have been praised as vehicles for tackling complex sustainability issues, but their success relies on the reconciliation of stakeholders’ divergent perspectives. We yet lack a thorough understanding of the micro-level mechanisms by which stakeholders can deal with these differences. To develop such understanding, we examine what frames—i.e., mental schemata for making sense of the world—members of MSIs use during their discussions on sustainability questions and how these frames are deliberated through social interactions. Whilst prior framing research has focussed on between-frame conflicts, we offer a different perspective by examining how and under what conditions actors use shared frames to tackle ‘within-frame conflicts’ on views that stand in the way of joint decisions. Observations of a deliberative environmental valuation workshop and interviews in an MSI on the protection of peatlands—ecosystems that contribute to carbon retention on a global scale—demonstrated how the application and deliberation of shared frames during micro-level interactions resulted in increased salience, elaboration, and adjustment of shared frames. We interpret our findings to identify characteristics of deliberation mechanisms in the case of within-frame conflicts where shared frames dominate the discussions, and to delineate conditions for such dominance. Our findings contribute to an understanding of collaborations in MSIs and other organisational settings by demonstrating the utility of shared frames for dealing with conflicting views and suggesting how shared frames can be activated, fostered and strengthened.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Today’s pressing challenges to the sustainability of social, economic and ecological systems are complex, closely intertwined with each other, and therefore relevant to a broad spectrum of stakeholders (Liu et al., 2018). Multi-stakeholder initiatives (MSIs) are increasingly used to engage multiple stakeholders in decisions on sustainability policies (Gray & Purdy, 2018; Mena & Palazzo, 2012), aiming to integrate their knowledge, gain their commitment, and arrive at solutions that are likely to be accepted and implemented by all involved. MSIs range from large, well-known global partnerships such as the UN’s cross-sector collaborations for reducing poverty (Utting & Zammit, 2009) and certification initiatives that create non-governmental governance mechanisms (for example the Forest Stewardship Council/FSC, Roundtable for Sustainable Palm Oil/RSPO, Fairtrade International) to small projects where local stakeholders participate in decision making concerning particular socio-ecological systems (Kenter, 2016a, 2016b; Raymond & Kenter, 2016; Reed et al., 2017a). These smaller participative projects generally do not take the form of legal partnerships, and tend to involve stakeholders that are not representatives of organisations and do not have formal decision-making power, such as local community members.

In practice, multi-stakeholder collaborations often struggle to achieve the joint decisions they aim for because it proves hard to bridge multiple stakeholders’ different or even conflicting interests and perspectives (e.g. Dentoni et al., 2018; Ferraro et al., 2015; Gray & Purdy, 2018; Kenter et al., 2014, 2016a, 2016b; Moog et al., 2015; Ranger et al., 2016; Reed et al., 2013, 2017a; Reinecke & Ansari, 2015). In the literature on MSIs, insights are accumulating on how stakeholders can reach common ground and arrive at mutually satisfactory decisions (e.g., Dreyer et al., 2011; Reinecke & Ansari, 2015). However, we yet need to develop a better understanding of how stakeholders bridge their different perspectives during these collaborations, particularly when it comes to the micro-level mechanisms by which perspectives are deliberated (DeWulf & Bowen, 2012).

We capture stakeholders’ perspectives by examining their ‘frames’, i.e. mental schemata that actors use to make sense of the world (Goffman, 1974), and in our case of the situation and issues at stake. Taking an interactive perspective on frames, we regard frames as dynamic structures that are socially constructed and transformed during social interactions (Benford, 1997; DeWulf et al., 2009) and can therefore be deliberated through interactions. Moreover, we hold that actors can apply frames in different ways, resulting in different views of particular situations or issues. Whilst frames are sensemaking devices, views are the interpretations that result from the application of a frame, i.e., they are the ‘sense’ that actors make of the world. Even in the case of shared frames, actors can thus hold conflicting views that impede joint decisions.

Studies that apply the lens of frames in organisational research (e.g. Gray et al., 2015; Kaplan, 2008) and in the context of MSIs (e.g. DeWulf & Bowen, 2012; Dreyer et al., 2011) have so far concentrated on what Schoen and Rein (1994) call ‘between-frame conflicts’, i.e. on situations where actors use conflicting frames to interpret and evaluate the issues at stake. We offer a different perspective by asking how stakeholders deal with conflicting views when they can draw on shared frames. We thus explore how, and under what conditions, stakeholders use shared frames to tackle ‘within-frame conflicts’ (Schoen & Rein, 1994), i.e., disagreements on views (rather than frames) that stand in the way of joint decisions. Framing research (Schoen & Rein, 1994) acknowledges that conflicts can occur within shared frames, but has to our knowledge not elaborated on how such conflicts are dealt with.

Whilst research on between-frame conflicts has analysed mechanisms by which divergent frames may develop and change interactively, we examine how stakeholders deliberate their shared frames during these interactions. Through an inductive analysis of a ‘best practice’ case, we demonstrate how the application and deliberation of shared frames during micro-level interactions resulted in increased salience, elaboration, and in some cases adjustment of shared frames. We interpret our findings to suggest that frame deliberation mechanisms in settings where actors use strong shared frames from the outset differ to those that have been described for settings of between-frame conflicts. In the case of shared frames, it is not essential for actors to modify their frames, but it is important to make shared frames more salient and elaborate them to encompass divergent views, in order to resolve within-frame conflicts that hinder joint decisions. We further explain why the shared frames dominated the discussions in this setting, considering that the discussion of divergent views could have reinforced different frames or broken up the shared frames. We deduce conditions for such dominance of shared frames during discussions, enabling us to suggest how these conditions can be identified and promoted in practice. Our focus on within- rather than between frame conflicts hence serves to demonstrate not only the utility of shared frames for bridging differences in views, but also how shared frames can be activated, fostered, and strengthened.

Empirically, we derive our insights from a qualitative study of discussions during an MSI on the protection of peatland ecosystems and communities in the North Pennines (United Kingdom). This sustainability issue has international significance, given that peatlands are an important source of biodiversity, water regulation, and carbon sequestration, and globally store about 30% of soil carbon stock (Bain et al., 2011). The MSI was set up in response to the Brexit decision, aiming to inform policies for peatland protection after the UK would leave the European Union and EU policies would no longer protect this important ecosystem and the communities who maintain it. Particularly, this MSI constituted a deliberative monetary valuation of peatlands, where stakeholders considered social and cultural peatland values and their views on social payments for conserving them. Deliberative valuation has been advocated as an answer to the limitations of conventional economic appraisal through its ability to tackle multiple conflicting and potentially incommensurable values (O’Connor & Kenter, 2019; Orchard-Webb et al., 2016; Spash, 2008). Thus far, however, frame deliberation, which is the focus of this paper, has not been explicitly considered within this field.

In what follows, we first review conceptualisations of frames and frame deliberation mechanisms and how they have been applied in organisational settings generally and MSIs in particular. We then present our methods and findings. Our discussion centres on characteristics of frame deliberation mechanisms in settings of within-frame conflicts where actors use shared frames, and explanations for the dominance of shared frames during the discussion. We conclude by highlighting boundary conditions, limitations, and implications for future research.

Background

The Concept of Frames

The concept of frames has been applied across a range of disciplines such as psychology, sociology, political studies, and management. Frames shape individuals’ interpretations of “what is going on” or “what should be going on” (Benford & Snow, 2000, p. 614; Goffman, 1974) and serve to guide people’s actions. Actors will for example interpret a waving hand in a different manner depending on whether they apply a frame of ‘greeting’ or ‘conflict’, and they will react to this signal differently subject to their interpretation, for example in a friendly or hostile manner. Types of frames have been distinguished firstly by “what is framed” (DeWulf et al., 2009), for example issues or interaction processes. Issue frames are schemata that shape actors’ interpretation of an issue at stake, such as the reasons and solutions to a sustainability problem. Interaction frames in turn concern the communication process and appropriate ways of behaving during the interaction (DeWulf et al., 2009).

Recent reviews have pointed out that researchers tend to take either a more static or more dynamic and interactive view of frames (Cornelissen & Werner, 2015; DeWulf et al., 2009). Some treat frames as relatively stable cognitive schema or categories, such as memory structures that help people “organise and interpret incoming perceptual information by fitting into pre-existing categories” (Minsky, 1975, cf. DeWulf et al., 2009). Others have described frames as dynamic structures that are socially constructed, negotiated, contested, and transformed (Benford, 1997, p. 415; Goffman, 1974). In this sense frames can be regarded as co-constructions which are continuously negotiated during social interactions. Due to socialisation, individuals share certain frames with members of their social groups, such as friendship groups, organisations, organisational fields, and societies. When individual frames change during social interaction, this can impinge back upon the social group’s frames. For example, institutional theorists have argued that actors’ frames are shaped by and shape the institutional logics—i.e. belief systems and associated practices—of their organisational fields (Purdy et al., 2019). Individually held frames and group frames are thus interdependent and overlap.

Studies following the dynamic perspective on frames tend to focus more on the interactional framing process rather than the resultant frames (DeWulf et al., 2009). In line with DeWulf et al. (2009) however, we hold that the more static or more dynamic conceptualisations of frames are not mutually exclusive. Even when frames are co-constructed and change continuously during social interactions, extant frames can be identified at a certain point in time—even though they may change later on. The focus on either the structure of frames or on the framing process can be chosen based on the research question, and on whether the stable or the dynamic aspect of frames is of practical importance. At a certain point in time—for example at the start of an MSI—it is important to assess different individuals’ or groups’ current frames, to establish a baseline for discussion and to be able to examine subsequent change. At the same time, examining the co-construction process will be useful for supporting frame deliberation. By understanding how in detail individual or group frames emerge and are modified during interactions, it will be easier to steer these interactions. In our study, we therefore examine not only the relatively stable structure of frames at the start of the examined stakeholder interaction, but also the mechanisms through which they are deliberated.

Building on the dynamic perspective of frames, we additionally reason that holding the same frames does not mean actors necessarily arrive at the same interpretation or ‘view’ of a situation or issue. Firstly, frames are schemata and therefore do not include all specifics of every situation. In other words, they are sensemaking devices rather than the sense that actors make of a particular situation. Therefore, different actors can apply the same frame in different ways, resulting in different interpretations. For example, actors may share a ‘sustainability’ frame, defined as the need to preserve the natural environment for future generations, which guides their judgement on environmental management. Using this frame, these actors can however come to different interpretations of whether a particular wildlife management scheme is sustainable. The sustainability frame is hence sufficiently broad to yield different interpretations of specific situations. Such different interpretations can amount to within-frame conflicts, i.e. conflicting views despite shared frames. Schoen and Rein (1994) suggest in this vein that the same policy frame can yield conflicting views on policy actions. For example, Liberals who advocate the same general welfare policies “tend to disagree among themselves about the proper treatment of ineligibles on the welfare rolls” (Schoen & Rein, 1994, p. 35).

Actors can also hold multiple frames at the same time, and different frames become more or less salient to them depending on cues in the environment (Goffman, 1974). At a particular point in time, certain frames or combination of frames can therefore be more salient to one actor than another, leading to different interpretations. For example, actors may hold the same greeting frame, but arrive at different views on whether a waving hand was meant to be a ‘merely polite’ or ‘warm, personal’ greeting, due to attention to different cues, such as the smiling face or previous conversations with the waving person.

Whilst the distinction between frames and views is inherent in the definition of frames (Goffman, 1974) and within-frame conflicts (Schoen & Rein, 1994), it has to our knowledge not been drawn in empirical framing research. Instead, frames are sometimes described in terms of quite specific views of certain situations, such as particular management options for local natural resources (e.g. DeWulf & Bowen, 2012; Hassenforder et al 2016; Shmueli, 2008). When conceptualising frames as interpretive schemata, it is however necessary to ‘reconstruct’ the schemata from the idiosyncratic experience through which they are expressed (Johnston, 1995). As Schoen and Rein (1994) point out, it is in practice often difficult to discern frames, given their tacit nature. It can therefore also be difficult to distinguish between conflicts within and across frames, as this distinction depends on how we construct the frames that underly conflicting positions (Schoen & Rein, 1994, p. 35), particularly the level of abstraction at which we define the frames.

Frame Deliberation

In line with the interactive view on framing, we suggest that frames can be ‘deliberated’ through social interactions. We follow Chambers’ (2003, p. 309) generic definition of deliberation as “debate and discussion aimed at producing reasonable, well-informed opinions in which participants are willing to revise preferences in light of discussion, new information, and claims”. Besides opinions and preferences, researchers have also understood deliberation to be about informing, forming and revising individual and shared values (Kenter et al., 2016b), whilst we examine the deliberation of frames. Drawing on framing research, we distinguish between (a) mechanisms of frame deliberation, which includes frame reflection and social interaction, and (b) outcomes of frame deliberation concerning the resultant frames. We conceptualise these components by drawing on general framing theory, research that applies the framing lens to organisational contexts generally, and to MSIs in particular. Notably, the majority of prior framing research describes frame deliberation mechanisms at the meso-level, namely as interactions between organisational or stakeholder groups. Only a minority of studies elaborates on micro-level mechanisms, namely in-situ actions and interactions between individuals that underly frame deliberation.

Mechanisms of Frame Deliberation

We distinguish between frame reflection and social interaction as prominent mechanisms of frame deliberation. The notion of frame reflection was developed by Schoen and Rein (1994) when outlining how political opponents can resolve frame conflicts. In the case that disputes take place within the same frame, they hold, disputes can be resolved through reference to facts alone and the political conflicts are therefore tractable. However, if the dispute takes place across different frames, opponents need to become aware of their own and the opponent’s frame in order to make the conflict tractable. They must give reason for their own view and acknowledge the legitimacy of the opponent’s conflicting values, in order to arrive at a ‘reframing’ of the policy dilemma (Schoen & Rein, 1994, p. 187). Frame reflection serves to lay open what opponents regard as ‘facts’, tied to their selective perception within the boundaries of their frames.

We argue that frame reflection also helps overcome within-frame conflicts, namely conflicts between actors’ different views that result from different applications of the same frame or different frame salience. Reflecting on shared frames can here help stakeholders understand why they have applied the frame differently or referred to a different shared frame, helping to reconcile or agree on the different interpretations. Reflecting on shared frames will also make these frames more salient and thereby more readily available for resolving differences in subsequent discussions.

Social interaction is not only core to deliberation in terms of discussion and debate (Chambers, 2003) but is also an integral component of framing and frame change. Early framing theory suggests that during social interactions, individuals send social cues (verbal or non-verbal signals) to each other indicating how they want their message to be understood, and thereby activate the counterpart’s frames for interpreting messages and actions. This is possible because individuals’ frames are a product of socialisation and therefore shared by members of a social group. Goffman’s (1974) classic example is a fight amongst children who cue to each other that the fight is either ‘real’ or ‘play’. Frames can also be switched or transformed during social interactions when actors respond to each other’s suggestions and add new interpretations. This can occur firstly through ‘keying’, i.e. when actors signal to others that they should change their current interpretation of an activity, using verbal cues such as “I'm really serious about this” (Goffman, 1974, p. 502), motivating the counterpart to behave differently. For example, a child can signal that the play fight is now a real fight. A switch or modification of frames can also occur through unintentional ‘misframing’, where actors get the wrong idea of the expected frame, or through intentional ‘frame break’, namely a violation of the current frame. Others can react either by maintaining the initial frame or by adopting the new or modified frame. Frames can be elaborated during the interaction as actors respond to each other’s suggested frames and add new interpretations of top of them, also called ‘lamination’ or ‘layering’ of frames (Goffman, 1974). With each new interpretation, a layer is added on top of the initial frame, resulting in a multi-layered frame structure (Goffman, 1974, p. 156).

Interactional framing mechanisms have been elaborated in some detail by social movements research (Benford & Snow, 2000; Snow et al., 1986) when describing how members of social movements align their frames to potential followers’ frames in order to win them for the movement. According to Snow et al. (1986), frame ‘bridging’ is used to link two or more ideologically congruent but previously unconnected frames. ‘Amplification’ serves to invigorate specific cultural values and beliefs that are part of a frame. ‘Extension’ is used to extend the boundaries of the social movement’s primary frameworks to encompass interests or points of view that are salient to potential adherents (Snow et al., 1986, p. 472). ‘Transformation’ in turn serves to change old understandings and/or generating new ones.

Snow et al.’s (1986) categorisation of frame alignment mechanisms has been applied to frame conflicts in various organisational contexts. For example, Kaplan’s (2008) study of ‘framing contests’ details how managers use the mechanisms described by Snow et al. (1986) to align their own and others’ frames concerning organisational strategy, after initially attempting to make their own frame the predominant frame. Gray et al. (2015) describe micro-processes of framing related to organisational frame change, suggesting that members of organisations use keying and frame breaks to layer interpretations and ‘amplify’ either existing or new frames.

A few studies have described framing mechanisms in MSI settings. For example, Dreyer et al. (2011) highlight frame alignment in an MSI concerning environmental risk management in the Baltic Sea region. To gain wider media attention, NGOs here ‘bridged’ their environmental frame with a ‘health frame’ and ‘extended’ their frame of local environmental pollution in the Baltic Sea to a more global frame of the Baltic Sea as vulnerable to international maritime activities. On a more general level, Vandenbussche et al. (2017) suggest that the success of collaborative planning by multiple stakeholders relies on an interplay between framing and relational dynamics. They propose that mutual frame alignment relies on perceptions of positive relations between stakeholders, which help overcome frame divergences, whilst the degree of frame alignment impacts back upon the quality of stakeholder relationships. Tisenkopfs et al. (2014) in turn suggest that frame alignment relies on a process of mutual learning. In their study of agricultural networks in Latvia, mutual learning was encouraged by stakeholders’ incomplete knowledge about new methods of biogas production.

A few studies in MSI settings have also taken a micro-level view on frame deliberation. Brugnach et al. (2011) posit that actors use certain interaction strategies to deal with frame differences. ‘Rational problem solving’ aims at finding solutions to problems by trying to arbitrate the frame differences using factual information, whilst ‘dialogical learning’ aims at reciprocal communication to learn about each other’s frame and develop a joint problem definition. ‘Persuasive communication’ is used to communicate the meaningfulness of one’s own frame, and ‘negotiation’ to reach an agreement despite the frame differences. ‘Opposition’ aims at imposing one’s own frame through the use of power. Compared to the mono-directional framing actions described by Snow et al. (1986; focusing on social movement members seeking alignment with audiences’ frames) these interaction strategies highlight the interactional and multidirectional aspect of frame deliberation.

Perhaps the most detailed analysis of micro level stakeholder interactions is provided by DeWulf et al. (2004) and DeWulf and Bowen (2012). In collaborative soil conservation initiatives in Ecuador, they describe how stakeholders use certain ‘discursive interaction strategies’ to deal with their differences in issue frames to arrive at joint definitions of problems and interventions. For example, stakeholders in these cases ‘accommodated’ their own framing to a challenging issue element—which is akin to frame extension. Alternatively, dominant actors in these cases used ‘frame disconnection’, i.e., they disconnect challenging elements from the ongoing conversation as irrelevant or unimportant, and thereby suppressed certain stakeholders’ contrasting frames. ‘Frame incorporation’ in turn serves stakeholders to incorporate a downgraded reformulation of others’ frame into their own issue frames. Different to the framing actions described by Snow et al. (1986), frame incorporation and disconnection thus allow dominant stakeholders to suppress others’ frames or subjugate them into their own frames, indicating that stakeholders in this setting aim to put their frame through, even if it requires them to be dominant.

Outcomes of Frame Deliberation

Several studies concentrate on the outcomes of what we call frame deliberation, considering resultant frames. As an outcome of ‘framing contests’, certain actors’ frames may emerge as the predominant frame that is used to arrive at joint decisions (Kaplan, 2008). However, this frame may become dominant only after being modified, for example extended and amplified, to encompass values and interests of other actors. There are many forms of compromise, as either one or more of the interactants can adjust their initial frame, i.e., modify or change it.

When multiple actors adjust their frames, they may do this by merging them into an overarching new frame (Gray et al., 2015) which has been called ‘compromise frame’ (Fligstein & McAdam, 2011) and ‘hybrid’ frame (Rao & Kenney, 2008). Similarly, actors can construct a new frame that helps arrive at joint problem solutions but preserves frame differences (Le Ber & Branzei, 2011). In this vein, Ferraro and Beunza (2018) describe how representatives of an automotive firm and an ethical shareholder organisation (the Interfaith Centre for Corporate Responsibility) negotiated a new, shared frame of ‘climate risk’ that agreed with the priorities of both parties, namely a focus on economic risks as well as environmental risks of carbon emissions and climate change. Openness to each other’s views and trust were seen as prerequisites for reaching this shared frame. In a similar vein, Kaplan and Orlikowksi (2013) propose that managers can achieve provisional settlements, allowing for joint decisions, if they can link their different interpretations of strategic situations and construct a strategic account that is regarded as coherent, plausible, and acceptable to the actors involved.

Importantly, adjusting frames and reaching shared, hybrid frames does not mean actors have to fully agree. Ansari et al. (2013, p. 1032) thus emphasise that collective hybrid frames that facilitate joint decisions can embody different interests even when actors do not shift their underlying logics. Gray et al. (2015) in turn suggest that organisational members may agree to disagree and maintain ‘frame plurality’. This can be the case when frame differences do not hinder joint decisions. For example, Klitsie et al. (2018) demonstrate that members of cross-sector partnerships were able to agree on an authoritative text whilst maintaining ‘optimal frame plurality’, i.e. a degree of plurality that creates creative tensions but avoids excessive variety that impedes sustained collaboration. Alternatively, external pressures to reach decisions can force actors to make compromises without adjusting their frames or creating a hybrid frame. Reinecke and Ansari (2015) thus observe that members of Fairtrade International had to suspend intractables and establish a truce in order to reach timely decisions on fair price.

Overall, the literature on framing in organisational and MSI settings has outlined several mechanisms and outcomes of frame deliberation. However, the focus of this research is on between-frame conflicts and we know little about how and under what conditions stakeholders use frames that they already share to overcome within-frame conflicts, which can be major barriers to joint decisions. We cannot take for granted that agreement on frames is sufficient for solving within-frame conflicts. To justify their different views, stakeholders could continue to refer to different frames amongst the shared frames, depending on which one is salient to them in association with the situation, further increasing the salience of different frames for different actors with respect to this issue. Moreover, given the socially constructed nature of frames, it is possible that shared frames do not withstand the conflict, but change and are broken up through controversial discussions.Footnote 1 For example, to justify their different views, actors may reinforce different meanings associated with the same shared frame and thereby modify this frame, which could reach the point that the shared frame is split into different frames.

As mentioned, the majority of prior framing research describes frame deliberation mechanisms at the level of organisational or stakeholder groups rather than observing the micro-level mechanisms that underly frame deliberation. A micro-level analysis is however useful for understanding when and how exactly frames become salient and develop as stakeholders act and react to each other in situ. Such understanding promises to help leaders of collaborations facilitate the interactions in a way to support the use and deliberation of shared frames. In order to analyse micro-level interactions amongst stakeholders, it is necessary to observe them in situ. We chose a stakeholder workshop as an ideal forum for observing detailed micro-level discussions between individual stakeholders for the purpose of reaching joint decisions.

Methods

Methodological Approach

We followed an interpretivist epistemology (Berger & Luckmann, 1966; Burrell & Morgan, 1979), with the aim to develop a plausible and internally consistent interpretation of the events and of the participants’ perceptions. We started our research with the conceptual lens of frames and frame deliberation, but further developed the concepts through inductive insights to arrive at an empirically grounded model. In line with the interpretivist approach, we did not use validity and reliability as criteria for the quality of our research, but followed Lincoln and Guba’s (1999) criteria of trustworthiness and the principles of reflexivity and transparency (Grodal et al., 2020; Pratt et al., 2020). Thus, to reveal the ‘dependability’ of our findings (Lincoln & Guba, 1999) we define our theoretical starting point and the questions that guided our categorisation of constructs (see Grodal et al., 2020). To achieve credibility, we are transparent about the links between the data, concepts, and the grounded model, as we relate our findings to detailed observations and quotes (Gioia et al., 2013); we describe the ‘moves’ taken during the categorisation process (Grodal et al., 2020); and we triangulate our findings (Lincoln & Guba, 1999). Moreover, to enable future researchers to inspect the transferability of our findings to corresponding settings, we provide a thick description of our research context (Lincoln & Guba, 1999, p. 420).

Research Context

Peatlands cover over 3% of the earth’s land surface (Joosten & Clark, 2002). They are an important source of biodiversity, water regulation, and carbon sequestration, globally storing about 30% of soil carbon stock (Bain et al., 2011). Despite its relatively small size, the UK holds between 9 and 15% of Europe’s peatland and 13% of the world’s blanket bog (Bain et al., 2011). Climate change and changes in land use and management now threaten to trigger long lasting changes or ‘tipping points’ in peatland ecosystems, which may lead to a perpetual release of carbon into the atmosphere. Presently the protection of peatlands is supported by EU policies such as the EU habitats directive (Byg et al., 2017), but the event of the UK leaving the EU necessitates a reconsideration of protection policies for the UK.

We studied an MSI involved in the UK based project ‘Peatland tipping points’,Footnote 2 which investigated how changes in climate and land management affected peatland ecosystems in the UK. We drew our data from a workshop through which the stakeholder collaboration took place, allowing us to observe micro-level interactions in real time and to account for the influence of design characteristics on frame deliberation. The aim of the workshop was for scientists to work with stakeholders to identify options for managing and protecting peatland ecosystems and upland rural communities in the North Pennines after Brexit, taking into account the peatland ecosystem as well as related social and cultural practices such as recreation, sheep grazing and grouse shooting (also see Reed et al., 2017b, 2020). By the end of the workshop, stakeholders had to jointly decide on recommendations for (a) what environmental land management options to be included in the governmental peat management payment scheme, and (b) what ‘fair price’ (Kenter, 2020) should be paid for those. The workshop was also a forum for uttering disagreements with the current scheme and inform other stakeholder groups and policymakers on difficulties and local issues regarding the scheme. The workshop and project results fed into a policy brief to the UK government. Stakeholders’ decisions and feedback could make a difference to what practices would be supported or prohibited, which was personally significant to some of the stakeholders, as detailed later on.

The first author, who led the research presented in this paper, was not part of the Peatlands tipping point project. The second author served as research assistant on the Peatlands project and was involved in administration and stakeholder interviews feeding into the workshop. The third author was a leader and facilitator of the workshop. We hence took advantage of the first authors’ outsider perspective as well as the second and third authors’ understanding of the Peatlands issues and the workshop rationale.

The workshop took place in the North Pennines and lasted about 6 h. The structure was designed in accordance with the Deliberative Value Formation model (Kenter et al., 2016b), a theoretical model developed in the context of environmental valuations, where participants moved from deliberating their broad values to connecting these with contextual information and evidence in order to eventually deliberate more specific contextual values for different policy options. Following Kenter et al. (2015) we thus define values to include both overarching principles and life goals such as fairness and sustainability and the contextual importance assigned to things, such as the importance of peatlands for recreation or place identity. A key rationale behind the structure of the workshop was to identify broader shared values, both in general and in relation to peatlands, early on in the workshop, before moving to questions of management.

In the morning, the third author presented results of a pre-workshop survey on the stakeholders’ values, followed by a storytelling exercise where stakeholders narrated their personal experiences of the North Pennines moorlands, with the option to consider these values. Project members then presented the outcomes of their economic and ecological analyses, introducing four post-Brexit ‘scenarios’ that had been developed through scientific research as well as inputs from an earlier stakeholder workshop. This highlighted various conflicts in management (e.g., possible negative tipping points in carbon sequestration resulting from overgrazing, negative impacts of grouse moor burning on carbon sequestration, negative preferences of recreationalists towards ‘re-wetting’ peatlands,) and risks (e.g., projections of a collapse in upland grazing if agricultural subsidies were lost post-Brexit). This was followed by a presentation by the second author about an interview study investigating the values of stakeholders in the region. The strong emphasis on stakeholder values was placed by the leaders of the Peatlands project, but was also well suited for the purpose of studying frames.

The afternoon contained the interactive discussions between stakeholders which are at the centre of our frame deliberation analysis. Two groups were formed—the ‘red’ and the ‘blue’ group—each including representatives of all stakeholder groups and facilitated by one of the leaders of the Peatland project. Each group was asked to evaluate the management policies in the scenarios, suggest what combination of policy options was most desirable for achieving multiple objectives and how the scenarios met different values. Each group further had to decide on a recommendation on fair prices to be paid to farmers and landowners for certain agri-environmental services, particularly the maintenance and restoration of moorland, and recommend what services should be included in the new payment scheme. The workshop concluded with a summary by the facilitators and final participant comments. More detail on the broader workshop aims, structure and outcomes can be found in Albers et al. (2019).

Participants

21 stakeholders attended the workshop. Throughout the day, four main stakeholder groups were represented: estates, farmers, representatives of other businesses (two contractors and a surveyor), and conservationists, including local and national conservation agency representatives Three members represented other groups (see Table 1 for stakeholder descriptions). Although participants were selected as representatives of their organisations, they could express their personal views. As one conservationist put it, the stakeholders were there "as individuals”, which allowed for “personal opinions being expressed in a relaxed way”.

Within the peatland management context, participants had both conflicting and shared and interests. From the issues mentioned above, the most prominent and contentious in UK peatland management typically pertains to grouse moor burning, opposed by conservationists on the grounds of impacts on water, biodiversity and carbon sequestration (Glaves et al., 2013), whilst these impacts are often contested by traditional landowners. However, the strong reliance of the upland economy on agri-environmental payments that seek to enhance these ecosystem services also meant farmers and conservationists had a shared interest in agri-environmental payments that provided effective incentives, particularly within the post-Brexit context where agricultural policy was under review and where there was a strong political drive for more effectively linking public payments to public environmental goods than in the era of the EU’s Common Agricultural Policy (Bateman & Balmford, 2018).

Data Collection

Data were obtained by the first author through naturalistic observations of the stakeholder workshop and individual follow-up interviews. Table 2 characterises the two methods of data collection.

Naturalistic Observations

In-situ observations of the workshop were the primary method of data collection. These allowed the researchers to examine what frames were used and how they were deliberated during the interactions, drawing on inference as well as participants’ and facilitators’ explicit naming of frames. During the introduction round of the workshop, the first author explained that she was working on a complementary project studying interactions between stakeholders and was going to observe the interactions between participants to make the participants comfortable with her presence. The second author introduced herself as assistant on the Peatlands project. Throughout the workshop discussions, these authors sat in one of the two stakeholder groups, listening quietly and taking notes. The workshop discussions were audio-recorded and later transcribed. During the breaks, the second author completed administrative tasks whilst the first author engaged in informal conversations with the participants to gather more background information about the participants, check her understanding of discussion topics, and answer questions about her own research. Judging from participants’ talkativeness during these conversations, they appeared comfortable with her presence.

Interviews

Four weeks after the workshop and over the course of 2 weeks, the first author conducted short follow-up interviews with 13 workshop participants, covering all main stakeholder groups (Table 1). The interviews lasted between 7 and 33 min, with an average of 18 min per interview. The interviews were semi-structured, allowing for targeted questions whilst being open to participants’ emphases, to obtain participants’ snapshot views on their own frames and views, changes instigated by the workshop, and retrospective accounts of the interactions during the workshop. First, to assess participants’ personal recollection of the interactions, the interviewer asked what they remembered most about the discussions at the workshop. To get a better understanding of participants’ frames and views, the interviewer further asked what the interviewees felt were the most striking things about the management of the Pennine peatlands, and what they thought were the most important points of disagreement. The interviews then focussed on potential changes in individuals’ frames and views by asking participants whether the workshop discussions had influenced their perspective or feelings in any way, and whether they would do anything differently now after the workshop.

Data Analysis

We used an iterative-inductive approach to analyse the observations and interview data, following our interpretivist epistemology. We started the investigation with the broad research questions of what frames stakeholders use when discussing sustainability issues, and how they deliberate the frames during their collaboration in the workshop. Based on our preliminary theoretical understanding, we used the concept of frames and deliberation mechanisms as a starting point to interpret our data. From our reading of the framing and MSI literature, we initially expected to detect contrasting frames in this setting. However, during the workshop observations and interviews, it became clear that participants disagreed not on frames but only on views within shared frames. Our specific questions of how and why shared frames are used and deliberated under these circumstances thus emerged during data collection.

We identified frames by detecting the rationale and criteria underlying participant's reasoning. As noted before, frames have to be reconstructed from the idiosyncratic experience through which they are expressed (Johnston, 1995), which are more directly observable than the underlying frames. This idiosyncratic experience includes views that individuals express concerning certain situations. In line with Schoen and Rein’s (1994) criteria, we reconstructed frames that would “account adequately for things and relations the frame sponsor singles out for attention or selectively ignores” (Schoen & Rein, 1994, p. 36). Whilst some frames were quite implicit, we were able to define others in terms of the principles that participants verbalised. For example, the environmental frame was expressed when certain participants stated the need to protect the environment, and the social justice frame was made explicit as part of the value elicitation exercise. Key words used by participants to justify their views often served as indicators of underlying frames. For example, a participant’s reasoning “If this about securing the environment going forward, then my concern would be that if you moved towards that model, that will not necessarily be good for biodiversity …” was noted as reference to the ‘environmental frame’ which guided the participant’s evaluation of a particular scenario.

We observed that each observed frame was held by multiple stakeholders, across stakeholder groups. Each stakeholder thus held multiple frames, albeit we could not arrive at a complete list of each stakeholder’s frames, because we cannot assume that stakeholders expressed all of the frames they may have held. The distinction between frames and views became clear when observing that participants disagreed on issues, such as the benefits of heather burning, but justified their different views by referring to the same principles, such as environmental or economic concerns. This made us aware that the same frame could lead to different interpretations (views) of an issue. Online Appendix 1 presents definitions for each of the frames described in this paper, illustrative quotes, and examples of views supported by each frame.

In some instances, participants justified their divergent views with reference to different frames, but we noted that the others did not disagree on this reference, but rather used this reference to justify their own view or combine different views. We hence inferred that these frames were held by individuals, but the frames were also shared amongst them. We thus labelled these frames ‘shared frames’. These observations were confirmed by participants in the interviews highlighting the participants’ agreement on overarching aims. Whilst it is possible that participants individually held other frames that differed from each other, these did not surface in the workshop discussions or the interviews and thus did not appear to be applied or relevant to the discussions. All the frames that we identified were thus held by individuals, but also shared amongst participants of the workshop.

During the workshop, we noted down our initial ‘hunches’ (Locke et al., 2008), which we inspected during the later analysis. Unexpected insights emerged early on, in particular the lack of contrasting frames amongst participants, combined with what we later called the ‘collaboration frame’, namely a strong willingness to achieve shared aims across different approaches. After the workshop, we analysed the data moving iteratively between the different data sources, the data, the emergent themes, and the literature. We coded the data initially using the categories taken from the literature, as well as those noted during the workshop such as the ‘localisation frame’ concerning the need to take into account local knowledge and to find local solutions, the ‘global frame’ indicating that participants zoomed out to take a national or international perspective, and the ‘holistic’ frame, referring to the need to take into account a broad range of interacting issues. During the analysis, we clustered similar codes together and created sub-categories. For example, we identified different aspects of holistic thinking as (a) the need to consider the interrelation of economic and environmental concerns, (b) the need to simultaneously consider all aspects of the socio-economic system such as ecology, grazing, game shooting, and floods, and (c) the need to ‘balance’ these different elements. In this manner the frames became more detailed. During the coding phase we noted down our hunches about possible overall results. We also highlighted interaction episodes that seemed to document the frame deliberation process very clearly.

After completing the initial coding, we scrutinised our hunches. We created a table to summarise the evidence from workshop interactions and interviews for each emergent theme. We also created a table to pair each interviewees’ report concerning their frames and frame deliberation with corresponding evidence from the workshop transcripts. We further explored our hunches with the help of various NVivo queries to look for relationships between codes. For example, we searched for the co-occurrence of issues (e.g., burning) with certain frames (e.g., localisation, holistic frame) to substantiate our interpretations of the use of frames during the discussion. NVivo queries about the co-occurrence of particular frames with changes in frames helped us to explore whether and how these frames had been affected through the discussions.

Concerning deliberation outcomes, we first sought for categories from the literature—in particular emergence of a new frame, frame blending, frame shifting, and non-adjustment of frames. Increasingly however, we recognised changes in frame salience and elaboration as most important outcomes of frame deliberation and used these as coding categories.

To discern micro-processes of frame deliberation (i.e. in-situ actions and interactions between individuals that underly frame deliberation), we started with a host of categories derived from the literature to identify framing actions (e.g. frame reflection, frame breaks, layering, extension, blending, disconnection, polarisation, accommodation, meta-framing) and more general speech acts, such as exploring, contradicting, compromising, repeating and pruning, to scrutinise micro-level interactions. During the coding process, it became increasingly clear that these framing actions and speech acts were used to deal with divergent views rather than frames. For example, participants introduced different frames to ‘break’ an interpretation of an issue, but without breaking the shared frames. Some of the framing actions did however affect the frames per se, for example when participants amplified, extended, or merged frames, and this was where we typically identified frame ‘elaboration’. To examine the micro-processes in more detail, we analysed selected interaction sequences to detect which frames participants applied during this sequence, whether and how participants took up a frame that had been cued by another participant, and how this affected the frames. Incrementally, we dropped some of the initial categories of framing actions (e.g., frame disconnection, meta-framing) and speech acts (e.g., repeating, pruning), to identify a set of categories that best described the micro-processes that we observed. In the later stages, we discerned that Goffman’s (1974) and Snow et al.’s (1986) categories were the most important for capturing interaction mechanisms in our case. The final set of micro-level mechanisms and outcomes of frame deliberation were integrated into our grounded model of frame deliberation (Figs. 1 and 4).

Findings

Our analysis indicates that participants consistently used strong shared frames to justify their views and deal with divergent views. In this manner, shared frames dominated their discussions. The shared frames included an interaction frame, certain issue frames, and a set of value frames held by members of all stakeholder groups. During the discussion, frames were deliberated through frame reflection and social interaction, affecting frame salience, elaboration, and adjustment.

Shared Frames

Shared Interaction Frame

Our analysis of the workshop discussions and the interviews suggests that participants held a shared interaction frame which we call ‘collaboration frame’. This frame could be seen in the participants’ strong willingness to collaborate, based on their understanding that they shared a common overarching aim and an openness to others’ perspectives. In the interviews, several participants reflected on these elements when asked what they remembered most about the workshop. For example:

We're all working towards restoring and managing that peatland for the overall benefit of the environment in the future. (Business 1)

I think everybody was on board with what everybody's trying to do and trying to listen to everybody's point of view just to come to some sort of compromise or a plan for doing the best we can. (Farmer 1)

Several participants recognised that the shared aim spanned different interest groups’ divergent perspectives on the right way to achieve this aim: “We all want the same thing ultimately, we just have different ways and different thoughts about how we should go about that process.” (Conservationist 7).

The collaboration frame was linked to feelings of a positive atmosphere –“What I remember most is it was a very good atmosphere” (Business 1)—and a positive feeling about the workshop in general. Participants also mentioned that they were ‘heartened’ by the shared aim across different interest groups:

I was very heartened to be in the room with a group of people that whatever their main interest was (e.g. farming, grouse, climate), were all appreciative of the importance of peatlands and agree that we want to get to a place where we have good functioning peatlands for the future. (Conservationist 1)

Shared Issue Frames

Throughout the workshop it also became clear that participants shared certain issue frames. Some of the shared frames were made explicit in the discussions, in particular an ‘environmental frame’, referring to a focus on environmental concerns (for example biodiversity, water regulation and carbon retention related to peatlands), and an ‘economic frame’, referring to the focus on economic and financial concerns (such as costs of peatland conservation). The other issue frames were more implicit.

We discerned repeated patterns of argumentation indicating the shared belief that it was necessary to take into account local differences and local knowledge and to find local solutions. We call this the ‘localisation frame’. For example, farmers and conservationists applied the localisation frame when pointing out that the official map of functioning or restorable blanket bog was not correct, because this map implied that all peat beyond 40 cm of depth could be turned into a “fully functioning rewetted peat ecosystem” even though more ‘porous ground and steep slopes’ would not allow for rewetting and thus creating a functioning blanket bog (Farmer 1).

Whilst the localisation frame meant that participants ‘zoomed in’ to highlight local factors, they occasionally also ‘zoomed out’ by using a ‘global’ frame. For example, participants reflected on the peatland management options in the light of UK-wide environmental policies, and they drew a few international comparisons of peatland management, for example with New Zealand.

Participants also frequently emphasised the need to take into account a broad range of issues that interact with each other, i.e., to take a ‘holistic’ view. “It’s not just the management of the hills; it needs to be a holistic approach.” (Farmer 1) The ‘holistic’ frame was used across participants, and promoted fervently by one farmer when explaining how environmental and economic concerns played into each other. For example, “from the farming point of view, most farmers farm as if they’re going to live forever because if you don’t look after the environment on your farm it won’t be there in the future.” (Farmer 1) The holistic frame was also apparent when participants stressed that it was impossible to gain viable solutions without taking into account the various elements of the socio-ecological system comprising farming, conservation of peatland, flood control, economic incentives and livelihoods, and that it was necessary to aim for a ‘balance’ between the interacting elements: “It’s all so interlinked that if you undermine one it undermines the other and at the moment there isn’t an economic sustainability underpinning environmental sustainability.” (Farmer 1). It also appeared that participants used the holistic frame to show their willingness to compromise and find a ‘balance’ between the different interests, in line with their collaboration frame.

Another frame concerned ‘framing to the public’, namely the need to use the right language to justify public payments and demonstrate public benefit to taxpayers. Public benefit was often phrased in terms of a ‘common good interest’, in line with the language used in scenarios presented by the researchers and the broader policy context (Bateman & Balmford, 2018). Participants highlighted that certain measures could not easily be framed favourably to the public even though they were required for protecting biodiversity. One example was animal population control: “I think telling the public we’re going to shoot all the bunnies and catch all the moles and hang them on the fence then there’s quite a bit of resistance, I would think.” (Farmer 2). Similarly, whilst the participants regarded carbon retention as a key function of peatlands, it was mentioned that the public may not be aware of this function.

Interestingly, the ‘framing to the public’ frame implied that ‘the public’ was seen as a common outgroup, suggesting an ingroup identity amongst workshop participants. The coherence of the workshop members as an ingroup became even more apparent in the frequent mention of disagreement with the approaches taken by certain external bodies, indicating an ‘external opponent’ frame. Above all, ‘Natural England’ (the government agency responsible for delivering large-scale agri-environmental payment schemes) was repeatedly criticised as historically imposing ill-informed policies that did not take into account local requirements, though there were more favourable opinions of more recent results-based payments pilot projects. To a smaller extent, participants showed antagonism towards broader UK and European governmental policies and the water regulation board.

Shared Value Frames

Our analysis further suggests that the workshop participants shared certain value frames, i.e., values that functioned as frames. Notably, the named interaction frame and issue frames are also not free of value, as values feed into them. For example, the collaboration frame relies on the perceived value of collaborating, the environmental frame relies on the value of an intact environment and the economic frame relies on the value of economic advantages. However, values are not the defining features of these frames, as these focus on interactions and issues, respectively. By contrast, values are the core constituents of value frames.

During the discussions, participants made either explicit or implicit reference to value frames to justify their reasoning. The value frame ‘social justice’ became salient foremost when participants discussed the current systems of distributing financial incentives for conservation actions, which put farms with poorer land at a disadvantage. A related value frame was ‘respect for tradition’, visible when participants referred to farming practices that had developed over centuries, based on local knowledge of the ecosystem, and were therefore environmentally sustainable.

Respect for tradition was linked with a strong value frame ‘place identity’, i.e. an appreciation of how the Pennines were special as a place. For example, beautiful wide views and broad skies, small scale farming based on long standing traditions, and the interdependent practices of grouse shooting, shepherding and heather conservation were described as beloved characteristics of this area. During the storytelling it became clear that a few participants had experienced these features as part of their upbringing, loading them with strong emotional value.

Somewhat related to the respect for tradition and place identity, participants also expressed a strong sense of ‘responsibility’ that guided their reasoning. Farmers and estate representatives felt responsible for maintaining the landscape that sustained their livelihood:

I think farmers are at the behest of environmentalists because it’s … certainly in our interest to do anything like that, because we have to live and work there every day. (Farmer 2)

Moreover, conservationists as well as those receiving the incentives (i.e., farmers and landowners) demonstrated their belief that payment incentives for ecosystem maintenance had to be allocated wisely to produce actual benefit: “Public money has to be used well and transparently” (Farmer 1).

Notably, some of the frames were cued by the workshop agenda from the start. Above all, the aim to evaluate post-Brexit peatland scenarios and to suggest fair prices for post-Brexit agri-environmental payments cued the ‘environmental’ and the ‘economic’ frame, and the need to combine the two. The ‘holistic frame’ was cued by the broad range of criteria included in the scenarios, and by stakeholders’ task to suggest a combination of policy options that would help achieve multiple objectives. The task to include multiple criteria and objectives also stressed the need to collaborate across different views, cueing the collaboration frame. The localisation frame became salient early in the discussion, driven by participants’ intricate knowledge of local differences that led them to question policies that did not take into account local factors. The value frames in turn were made explicit during the value elicitation exercise. Several other frames became salient only later in the discussion, such as the ‘framing to the public’ and ‘external opponents’ frame.

Stakeholders’ Views

The analysis of shared frames indicates how stakeholders’ frames informed their views concerning particular situations and issues (see Online Appendix 1). For example, the environmental frame informed views on particular methods of protecting biodiversity, and the localisation frame underscored views of mismatches between general grazing and cutting schemes and local peat conditions. At the same time, participants held certain divergent views despite their shared frames. We noted that these differences in views were based partly on different applications of shared frames and partly on differences in the initial salience that the frames had for different participants in relation to the issue.

There were disagreements between estate representatives and farmers on the one side and conservationists on the other concerning the environmental benefits and dangers of heather burning (discussed later), tied to different applications of the environmental frame. Moreover, there was initial disagreement on whether reducing grouse numbers was necessary for achieving satisfactory peatland conditions, again because participants applied the environmental frame in different ways. Whilst three conservationists explained that reducing grouse numbers could have biodiversity and carbon storage benefits, Estate 1 held that grouse management through burning helped conservation by preventing wildfires, and Business 3 explained that peat quality depended on local conditions more than grouse numbers. Differential salience of the economic versus environmental frame led to initial disagreement between a contractor and three conservationists on the benefits and dangers of planting trees. Whilst Business 3 suggested that tree production was an important new source of income for struggling farmers in the uplands, applying the economic frame, Conservationists 5 and 8 applied the environmental frame, explaining that planting “the wrong trees in the wrong place” was harmful for biodiversity and moor quality.

The different salience of certain frames also underscored divergent views regarding the option of rewilding, i.e., “letting nature take its course” as opposed to managing the landscape. Whilst an estate representative and two farmers highlighted the dangers of rewilding for current animal species, applying the environmental frame, two conservationists suggested payments for rewilding as an option for certain areas, using both the environmental and localisation frame.

Using and Deliberating Shared Frames

Our analysis of conversation episodes revealed how the shared frames guided participants’ reasoning and thus dominated during the discussion. Supported by their collaboration frame, participants repeatedly drew on the shared issue and value frames—partly implicitly and partly explicitly—to structure their argument, respond to each other, and arrive at joint decisions. As mentioned, in the case of divergent views some stakeholders initially applied the frames in a different manner or placed emphasis on different frames to justify their views. But, from their reactions to each other’s justifications, it was clear that they did not disagree on the frames the others referred to. Instead, they picked up the reference to this frame to further discuss the issue and arrive at an agreement.

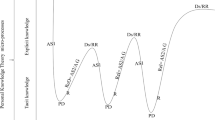

By being applied during the discussion, the shared frames were deliberated and thereby strengthened. Figure 1 illustrates how participants started with partly different views but shared frames, which underlay key frame deliberation mechanisms, feeding into deliberation outcomes concerning views and frames.

In terms of deliberation mechanisms, the workshop discussions allowed stakeholders firstly to reflect on their frames. For example, participants reflected on the environmental and economic frames when discussing the need to take both stances, and on the localisation frame when emphasising that Natural England did not sufficiently take into account local requirements. During social interactions, stakeholders used keying, layering and breaks of interpretations, and they amplified, extended and merged frames. Using and deliberating shared frames in this manner had the important function of dealing with divergent views, resulting in either agreements on views or maintaining a plurality of views. Moreover, the deliberation strengthened the frames by making them more salient to all involved, and more elaborate.

We did not discern any radical changes in the meanings associated with participants’ frames that would indicate ‘frame transformation’ (Snow et al., 1986). However, in the interviews, a slight change of meanings transpired. Changes in the relative salience and the elaboration of frames here amounted to a slight change in a frame, which we call ‘adjustment’ (rather than shift or transformation) of frames. Specifically, a surveyor and three farmers appeared to have significantly strengthened and elaborated their environmental relative to their economic frame, as they had become more aware of scientific details on environmental issues such as carbon retention, and on environmentally friendly alternatives to burning. For example,

I’m certainly far more aware when I’m on the fells of some of the finer points of the vegetation. And I am looking at sites and thinking, how would you restore that into a functioning carbon storing ecosystem? (Farmer 1)

Two conservationists had elaborated their economic frame and were now using it to a greater extent than before the workshop, as they had become more aware of economic management options in comparison to governmental subsidies:

I think as a group, as we began to discuss the role of businesses and their increased responsibility it triggered something in my mind that I thought well yeah, we do need to look at them to take a little bit more responsibility for their actions from now on. (Conservationist 7).

We will now take two examples of interaction episodes to demonstrate the use and deliberation of shared frames. The first example illustrates how frames were used to deal with divergent views on a particular issue, and how the frames were deliberated in the process. The second example shows how the course of interactions influenced the salience and elaboration of a particular frame.

Example 1: Using shared Frames to Deal with Divergent Views

We will first demonstrate the use and deliberation of shared frames with regard to the discussion of the perhaps most prominent point of disagreement, heather burning. Heather burning is a traditional practice used by farmers to create young shoots for grazing sheep and by the ‘sporting estates’, i.e. grouse shooting business, to yield a mixed (‘mosaic’) habitat for grouse. Members of these groups emphasised that controlled burning of combustible vegetation was also an important environmental measure to prevent wildfires, as it allowed for the growth of the more fire-resistant heather. This view was emphasised particularly by the grouse shooting estates: “Apart from getting young shoots through for grazing for sheep and for grouse we believe that it would be ridiculous not to have firebreaks to break wildfire up. Because once they get alight, they just keep going, they don’t stop.” (Estate 1).

A contrasting view was held foremost by conservationists, who had been lobbying for a stop of heather burning in the uplands. The view was that “the burning practices that have been carried out probably for the last 150/60 years are having a major negative impact on the upland environment, threatening these important carbon stocks, threatening the quality of our drinking water, increasing run-off from the big upland catchment, so associated with flooding downstream and impacting on priority habitats and species.” (Conservationist 5). Although the conservationists accepted that controlled burning helped to prevent wildfires, they argued that wildfires developed primarily on degraded, dry bogs, due to reduced water levels. Rather than controlling combustible vegetation through burning, degraded bogs should thus be rewetted to restrain combustible vegetation and make the bog more fire resistant. Views also diverged with regard to the option of burning merely for restoration purposes, which some conservationists criticised as unsustainable.

The issue of burning was brought up when evaluating the given scenarios in the blue group, as different burning practices featured in the different scenarios. The facilitator here labelled managed burning as a “the most controversial” aspect of the scenarios and outlined two ‘camps’ regarding burning, then inviting participants to present their stance. By frankly acknowledging that views on the issue were controversial, this introduction set the ground for participants mentioning their differing views openly and discussing them in detail.

The contrasting views on this issue were not resolved in the workshop. However, the discussions were shaped by shared frames, leading to conclusions that allowed the different views to co-exist, enabling a joint decision on what services should be included in the payment scheme. Rather than promoting the interests of their group, participants showed a clear willingness to evaluate burning as a practice by taking into account all interests and using the shared ‘environmental’ ‘localisation’ and ‘holistic’ frames. In line with their collaboration frame, participants were open to new information, built their arguments on the preceding utterances of other members, and reflected on the various stances. Figure 2 summarises the frames and deliberation mechanisms that participants used during this discussion.

The discussion started with Farmer 1 explaining the environmental risks of wildfire, hence using the ‘environmental’ frame (rather than promoting the narrower farming interest) and cueing this frame to the others (see Fig. 2). Layering onto this frame, a head estate keeper, part of the grouse shooting interest group, emphasised that the traditional ‘rotational’ burning practice was in fact a restoration activity and was not done routinely without a restoration need. He thus framed this practice in line with the environmental frame. He also applied the ‘holistic frame’ by combining economic (sheep and grouse shooting) and environmental aspects:

I think one of the huge mistakes was made was calling it rotational burning in the first place. You know, a keeper doesn’t go up to a bit of land and say, ‘Oh, I burnt that 15 years ago, it’s time to burn it again.’ They will go to an area that requires the heather vegetation could be taken off because it’s become long and stemmy and it isn’t good for grouse, it’s not good for sheep, draining out the bog. So they’ve probably been doing restoration burning for a long time under the remit of rotation burning. (Estate 1)

The same estate keeper also emphasised the need to take a holistic view on the burning issue to balance restoration with economic concerns:

It goes back to the holistic approach …, if you’re only looking at one factor, … you say: … if you stop burning completely … the peat’s going to start quicker … you forget about all the other stuff that it affects, whether it’s biodiversity, whether it’s the economics of the site. And you have to look at it as a whole and find the balance between all the different interests. (Estate 1)

Layering on the holistic frame, the estate keeper thus emphasised the interdependence of environmental and economic aspects and merged the environmental with the economic frame. Through this combination of frames, he offered a ‘break of interpretation’ of the burning issue, questioning the term ‘rotational burning’ and the approach of stopping burning completely (Fig. 2).

What followed was a discussion on the details of burning practices and alternatives such as cutting. Members of different interest groups asked each other factual questions, following a ‘rational problem solving’ approach (Brugnach et al., 2011) and demonstrating their willingness to learn from each other: Conservationist 1 explained the shooting communities’ practice of cutting combined with burning, Farmer 2 responded by inquiring about several details of this practice, which were then provided by the conservationist as well as the Estate representative 2. Farmer 1 chipped in with the comment “it [cutting] is a tool”, and shortly afterwards with the conclusion that “If we’re going to move on to trying to produce an outcome, you shouldn’t rule out any tool in the box”. He thereby suggested not to exclude any of the different practices, thus integrating the participants’ different views and allowing them to coexist. Farmer 1 justified his conclusion by drawing on the shared frames of localisation (the need to tap on local knowledge) and the environmental frame:

If we’re going to move on to trying to produce an outcome, you shouldn’t rule out any tool in the box to achieve that, and it should be relying on the intuition and knowledge of the people … that’s the only way that you’re actually going to get the improvement in the environment. (Farmer 1)

By layering the ‘localisation’ frame onto the holistic frame and the merged environmental and economic frames, Farmer 1 thus offered another break of interpretation, reinterpreting the different approaches to burning as a ‘tools’ in a ‘toolbox’ instead of alternatives. He thereby suggested that all the different approaches had potential use, depending on local conditions. This interpretation was clearly in line with the collaboration frame, and it served to extend the previously used environmental frames to encompass different views on burning.

The solution of retaining all tools was taken up by the facilitator: “Let’s expand that toolkit and let’s have more things in that toolkit that we can choose from”, followed by further confirmation and justification by Farmer 1, this time referring to the holistic frame in terms of taking a broad view and combining environmental and economic concerns:

You shouldn’t chuck anything out otherwise you’re limiting yourself because you don’t know what’s going to happen in the future. But the key thing for all these different scenarios is if you want to have environmental sustainability, it has to be underpinned by economic sustainability. (Farmer 1)

In this manner, the facilitator and Farmer 1 amplified the merged environmental, and economic frame, and the associated holistic frame. In the summary of the discussion, the facilitator later presented this conclusion as consensus across the different views in the group, again amplifying the used frames:

There is currently still conflict over whether or not burning should be allowed to be part of your toolkit or not. And going with the consensus of the table … the more tools you’ve got in that toolkit, the more adaptable you are and the more effectively you can then adapt to whatever changing conditions. (Facilitator of blue group)

This conclusion enabled participants to maintain their plural views on burning whilst reaching the joint decision of retaining burning in the catalogue of peatland management practices to be included in future policies.

The follow-up interviews later revealed that a few individuals had adjusted their views on burning slightly through the discussions. Farmer 2 related that he had now better understood the arguments against burning, and its possible alternatives. Conservationist 3 reflected on the different perspectives of the participants and pointed to the fact that scientific evidence regarding burning was inconclusive. Farmer 3 concluded that burning seemed to be acceptable in some areas but not others, relating to the localisation frame. He also explained his change of view:

I hadn't realised that if the peat is washed away they'll lose the carbon introduced as well. So I think I just have a better understanding of the consequences of allowing the peat to be damaged. So, controlling heather burning properly so that they protect the areas where the peat is. … I changed my mind on that one.

Notably, the discussions of divergent views also strengthened the ‘collaboration’ frame, visible in the fact that several interviewees recollected how workshop attendants had pursued a shared aim despite their different approaches. Using shared frames in their reasoning concerning divergent views (such as the issue of burning) had helped participants find an integrative solution (keeping all tools in the toolbox). This seems to have made workshop attendants aware that all participants’ interests should be taken into account to find a common solution for achieving the shared aim (frame reflection), thus strengthening the collaboration frame. Online Appendices 2 and 3 provide further illustrations of the use of frames and deliberation mechanisms during discussions of divergent views, concerning grouse management (Online Appendix 2) and tree planting (Online Appendix 3).

Example 2: Deliberating the Social Justice Frame

We now take the example of a particular frame, the social justice frame, to further illustrate how frames became more salient and were elaborated through the discussion, affecting subsequent discussions and the conclusions. Figure 3 summarises the use of frames and frame deliberation mechanisms in relation to deliberation outcomes for the relevant episode.