Abstract

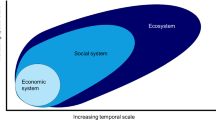

The article posits the concept of economy of mutuality as an intellectual mediation space for shifts in emphasis between market and social structures within economic theory and practice. Economy of mutuality, it is contended, provides an alternative frame of reference to the dichotomy of market economy and social economy, for inquiry about what business is for and what values it presupposes and creates. The article centers around the objective of gaining a broadened understanding of business so as to include not just market economy, but social enterprise and social economy. In pursuit of this objective, a range of various archetypes of business enterprise are considered in light of higher ends of economic life. The highest telos of business encompassing all such archetypes, it is argued, is founded on reciprocity and integral human development. The article concludes that, compared to market economy per se, economy of mutuality provides a better conceptual framework for business in undertaking the challenges of sustainability.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The concept is not to be confused with the much different notion of “economics of mutuality” discussed by Kay (1991).

An important caveat is that profit per se does not reveal anything concerning the means by which it has been made or the uses to which it is put. Profit sometimes flows from violations of commutative justice in respect to relations between an enterprise and its stakeholders (Dembinski 2011, p. 37). Recent critiques of Chinese enterprises in Africa reveal instances of businesses taking advantage of market power to enforce unconscionable prices and wages (Economist 2011). Such practices occur without violating existing positive law, yet nevertheless are violations of natural duties of justice and prudence (Dembinski, Id.).

Aristotle, Nicomachean Ethics, Bk. I, Ch.1, 1094a 1-2, p. 935.

Id., Bk. I, Ch. 2, 1094a 17-24 at 935.

Aristotle, Politics, Bk. I, Ch. 2, 1253a 25-32, at 1130.

Mission drift. Commercially oriented microfinance institutions (MFIs) are sometimes identified as drifting away from an original mission of serving low-income clients, instead serving better-off clients to improve the financial bottom line (Armendariz and Szafarz 2011). An ethical issue arises insofar as such MFIs are found to be using poor clients mainly as a means to attaining profitability (Sandberg 2012). Excessively high interest rates. Interest rates charged by some MFIs can range between 20 and 70 % per annum, making them higher than rates commanded by commercial banks (Rosenberg et al. 2009; Sandberg 2012). Group lending abuses. Violent collection practices and oppressive forms of group pressure are sometimes used by MFIs for obtaining repayment of group loans (Montgomery 1996; Ghate 2007).

Aquinas argues that human beings always act for some end, and that, whereas what he terms proximate ends often are sought for the sake of ulterior ends, human beings must always act for some ultimate end (Summa Theologiae 1-2, q. 1, aa. 1, 4, 6). He argues that the good that ultimately fulfills human beings—the good whose attainment he refers to as “beatitude”—is in God alone (Summa Theologiae 1-2, q. 2, a. 8, c).

In a study of the three sectors of markets, civil society, and the state, Grassl depicts the proximate end of markets to be efficiency. He identifies the ultimate end of markets to be profit. In contrast, he posits the proximate end of civil society as solidarity, and its ultimate end as fraternity. As for the state, he takes its proximate end to be equity and its ultimate end to be order (Grassl 2011, p. 115).

Aquinas argues that the good that ultimately fulfills human beings—the good whose attainment he calls “beatitude”—is in God alone (Summa Theologiae 1–2, q. 2, a. 8, c).

Again, the idea of a higher end refers to a purpose presupposed and endorsed by the archetype that is specified at a higher level of generality and abstraction than one given as the proximate end.

Associated with the “logic of gift” are issues concerning how to render a precise distinction between market-economic exchange via pricing systems and instances of reciprocity, for which gift-giving appears to be vital. Anthropological research suggests that what distinguishes market exchange from gift-giving is not the element of expected returns, which can be found in both, but rather the inability of donors to justifiably command counter-gift, even though the same might be wished for or anticipated (Testart 2007).

In both the United States and the UK, charities can engage in a limited amount of commercial activity, but only if the activity directly furthers the entity’s charitable purpose beyond simply raising funds (Doeringer 2010, p. 267). Since non-profits are barred from equity capital markets and generating a return for investors, non-profits must rely primarily on grants and donations for their survival, which are often insufficient to further their social goals (Taylor 2009/2010), p. 754.

Proverbs 29:18.

Here, I intend ‘education’ in a broad sense, encompassing not only what is taught in schools but also in churches, temples, synagogues, mosques, and other associations.

The vital importance of the family institution is expressed in the following passage:

It is surprising to see that humanity’s oldest institution, the one making it possible for people to live a harmonious and balanced life, and the very origin or society, is the target of ideological attacks. The family, not the individual, is the basis of society, since the latter cannot fully develop itself on its own: it is not self-sufficient and is naturally family orientated (Chinchilla and Moragas 2008, p. 120).

By contrast, in its tendency to reward unscrupulous conduct, the host of notorious executive compensation schemes connected to the financial crisis is inimical to the common good. Those schemes provide powerful incentives for people to maximize selfish interests at the expense of the well-being of others.

The insidious forms of moral degradation leading to the financial crisis reminds us of our interdependence and summons us to mutual responsibilities. Consider John Paul II’s encyclical Centesimus Annus:

[W]e see how [Rerum Novarum] points essentially to the socioeconomic consequences of an error which has even greater implications. As has been mentioned, this error consists in an understanding of human freedom which detaches it from obedience to the truth, and consequently from the duty to respect the rights of others. The essence of freedom then becomes self-love carried to the point of contempt for God and neighbor, a self-love which leads to an unbridled affirmation of self-interest and which refuses to be limited by any demand of justice (John Paul II 1991 ¶17).

For a proper framing of an economy of mutuality in the aftermath of recent financial scandals, it is vital to return to the ethics of virtue, human dignity, and a robust philosophy of the common good. Here is where human freedom and individual interest reach their proper proportion.

HDFC (A) Harvard Business School Case No. 9-301-093 (2000).

Sealed Air Corporation: Globalization and Corporate Culture (A), (B), Harvard Business School Case Nos. 9-398-096, 9-398-097 (1998).

AES Honeycomb (A), Harvard Business School Case No. 9-395-132 (1994).

In this regard, Collins and Porras, drawing a comparison between visionary companies, such as Hewlett-Packard and purely profit-driving companies such as Texas Instruments, quote the words of James Young, former CEO of Hewlett-Packard:

Maximizing shareholder wealth has always been way down the list. Yes, profit is a cornerstone of what we do—it is a measure of our contribution and a means of self-financed growth—but it has never been the point in and of itself. The point, in fact, is to win, and winning is judged in the eyes of the customer and by doing something you can be proud of. There is symmetry of logic in this. If we provide real satisfaction to real customers, we will be profitable (Collins and Porras 1994, p. 57).

References

Abela, A. (2001). Profit and more: Catholic social teaching and the purpose of the firm. Journal of Business Ethics, 31(2), 107–116.

Alford, H., & Naughton, M. (2002). Beyond the shareholder model of the firm: Working toward the common good of a business. In S. A. Cortright & M. Naughton (Eds.), Rethinking the purpose of business. Interdisciplinary essays from the Catholic Social Tradition (pp. 27–47). Notre Dame, IN: Notre Dame University Press.

Armendariz, B., & Szafarz, A. (2011). On mission drift in microfinance institutions. In B. Armendariz & M. Labie (Eds.), The handbook of microfinance (pp. 341–366). Singapore: World Scientific.

Aquinas. T. (1273/1972). In T. C. O’Brien (Ed.), Summa Theologiae. London: Eyre and Spottiswoode.

Argandoña, A. (1998). The stakeholder theory and the common good. Journal of Business Ethics, 17(9/10), 1093–1102.

Aristotle. (1941). In R. McKeon (Ed.), The basic works of Aristotle (B. Jowett, Trans.). New York: Random House.

Becchetti, L., Pelloni, A., & Rossetti, F. (2008). Relational goods, sociability, and happiness. Kyklos, 61, 343–363.

Benedict XVI. (2009). Encyclical letter Caritas in Veritate. San Francisco: Ignasius Press.

Billis, D. (2010). Hybrid organizations and the third sector. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Bourdieu, P. (1986). The forms of capital. In J. Richardson (Ed.), Handbook of theory and research for the sociology of education (pp. 241–258). New York: Greenwood.

Boyd, B., Henning, N., Reyna, E., Wang, D. E., & Welch, M. D. (2009). Hybrid organizations: New business models for environmental leadership. Sheffield: Greenleaf.

Buchanan, J., & Tullock, G. (1962). The calculus of consent: Logical foundations of constitutional democracy. Indianapolis, IN: Liberty Fund.

Buğra, A., & Arğatan, K. (2007). Reading Karl Polanyi for the twenty-first century: Market economy as a political project. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Calvez, J., & Naughton, M. (2002). Rethinking the purpose of business. Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame Press.

Chinchilla, N., & Moragas, M. (2008). Masters of our destiny. Pamplona: Universidad de Navarra.

Collins, J. C., & Porras, J. I. (1994). Built to last: Successful habits of visionary companies. New York: Harper Business.

Daly, H., & Cobb, J. B. (1990). For the common good: Redirecting the economy towards community, the environment and a sustainable future. London: Green Print.

de Tocqueville, A. (1994). In J. P. Mayer (Ed.), Democracy in America (G. Lawrence, Trans., Vol. 2). London: Fontana.

Dees, J. G. (1998). Enterprising nonprofits. Harvard Business Review, 76(1), 54–67.

Dembinski, P. H. (2011). The incompleteness of the economy and business: A forceful reminder. Journal of Business Ethics, 100, 29–40.

Doeringer, M. F. (2010). Fostering social enterprise: A historical and international analysis. Duke Journal of Comparative & International Law, 20, 291–303.

Dohmen, T., et al. (2009). Homo reciprocans: Survey evidence on behavioural outcomes. Economic Journal, 119(536), 592–612.

Donaldson, T., & Preston, L. (1995). The stakeholder theory of the corporation: Concepts, evidence, and implications. Academy of Management Review, 20, 65–91.

Douthat, R. (2014, July 30). In search of the conservative artist. New York Times (Op-Ed).

Durkheim, E. (1893). The division of labor in society. New York: Macmillan.

Duska, R. E. (1997). The why’s of business revisited. Journal of Business Ethics, 16(12/13), 1401–1409.

Economist. (2011, April 20). Trying to pull together: Africans are asking whether china is making their lunch or eating it.

Evan, W., & Freeman, R. E. (1993). A stakeholder theory of the modern corporation: Kantian capitalism. In T. Beauchamp & N. Bowie (Eds.), Ethical theory and business (5th ed.). Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Faldetta, G. (2011). The logic of gift and gratuitousness in business relationships. Journal of Business Ethics, 100, 67–77.

Freeman, R. E., Harrison, J. S., Wicks, A. C., Parmar, B. L., & de Colle, S. (2010). Stakeholder theory: The state of the art. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press.

Freeman, R. E., & Newkirk, D. (2008). Business as a human enterprise. In S. Gregg & J. R. Stoner Jr. (Eds.), Rethinking business management: Examining the foundations of business education (pp. 139–143). Princeton, NJ: ISI.

Friedman, M. (1962). Capitalism and freedom. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Fukuyama, F. (1995). Trust: The social virtues and the creation of prosperity. New York: Free Press.

Ghate, P. (2007). Consumer protection in Indian microfinance: Lessons from Andhra Pradesh and the microfinance bill. Economic and Political Weekly, 42(13), 1176–1184.

Gold, L. (2010). New financial horizons: The emergence of an economy of communion. Hyde Park, NY: New City Press.

Goodpaster, K. E. (1991). Business ethics and stakeholder analysis. Business Ethics Quarterly, 1, 53–73.

Goodpaster, K. E. (2011). Goods that are truly good and services that truly serve: Reflections on Caritas in Veritate. Journal of Business Ethics, 100, 9–16.

Granovetter, M. (1985). Economic action and social structure: The problem of embeddedness. American Journal of Sociology, 91(3), 481–510.

Grassl, W. (2011). Hybrid forms of business: The logic of gift in the commercial world. Journal of Business Ethics, 100, 109–123.

Gregg, S. (2010). Wilhelm Röpke’s political economy. Northampton, MA: Edward Elgar.

Gregory, P. R., & Stuart, R. C. (2004). Comparing economic systems in the 21st century (7th ed.). Mason, OH: South-Western.

Handy, C. (2002). What’s a business for? Harvard Business Review, 80(12), 49–55.

Harrison, L. E. (2012). Jews, Confucians, and Protestants: Cultural capital and the end of multiculturalism. New York: Rowman and Littlefield.

Hayek, F. A. (1948). Individualism and economic order. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Heinberg, R. (2011). The end of growth: Adapting to our new economic reality. Gabriola Island, BC: New Society Publishers.

Hirschman, A. O. (1997). The passions and the interests: Political arguments for capitalism before its triumph. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Hirst, P. (1994). Associative democracy: New forms of economic and social governance. Cambridge, MA: Polity Press.

Ims, K. J., & Jakobsen, O. D. (2011). Deep authenticity—An essential phenomenon in the web of life. In A. Tencati & F. Perrini (Eds.), Business ethics and corporate sustainability (pp. 213–223). Northampton, MA: Edward Elgar.

Jackson, K. T. (2004). Building reputational capital: strategies for integrity and fair play that improve the bottom line. New York: Oxford University Press.

John Paul II. (1991). Encyclical letter Centesimus Annus.

Jones, T. (1995). Instrumental stakeholder theory: A synthesis of ethics and economics. Academy of Management Review, 20, 92–117.

Kay, J. (1991). Economics of mutuality. Annals of Public and Cooperative Economics, 62(3), 309–313.

Keohane, R. O., & Nye, J. S. (2000). Globalization: What’s new? What’s not? (And so what?). Foreign Policy, 118, 104–119.

Koehn, D. (1995). A role for virtue ethics in the analysis of business practice. Business Ethics Quarterly, 5(3), 533–539.

Kropotkin, P. (1902/2009). Mutual aid: A factor of evolution. London: Freedom Press.

Marshall, A. (1920). Principles of economics. London: Macmillan.

Mbarathi, N. (2011). Kenya: Poverty eradication goes hi-tech with m-pesa. The Africa Report. 27 November. http://www.theafricareport.com/index.php/news-analysis/kenya-poverty-eradication-goes-hi-tech-with-m-pesa-5167300.html.

Melé, D. (2009). Integrating personalism into virtue-based business ethics: The personalist and the common good principles. Journal of Business Ethics, 88(1), 227–244.

Menning, C. B. (1993). Charity and state in Late Renaissance Italy. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Mill, J. S. (1848). The principles of political economy with some of their applications to social philosophy. London: Savill and Edwards.

Mitchell, R., Agle, B., & Wood, D. (1997). Toward a theory of stakeholder identification and salience: Defining the principle of who and what really counts. Academy of Management Review, 22, 853–886.

Montgomery, R. (1996). Disciplining or protecting the poor? Avoiding the social costs of peer pressure in micro-credit schemes. Journal of International Development, 8(2), 289–305.

Mook, L., Quarter, J., & Richmond, B. J. (2007). What counts: Social accounting for nonprofits and cooperatives (2nd ed.). London: Sigel Press, London.

Moore, G. (2005). Humanizing business: A modern virtue ethics approach. Business Ethics Quarterly, 15(2), 237–255.

Nagel, T. (1986). The view from nowhere. New York: Oxford University Press.

Nee, V., & Swedberg, R. (2005). The economic sociology of capitalism. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Novak, M. (1989). Free persons and the common good. New York: Madison Books.

O’Brien, T. (2009). Reconsidering the common good in a business context. Journal of Business Ethics, 85, 25–37.

Paine, L. S. (2003). Value shift: Why companies must merge social and financial imperatives to achieve superior performance. New York: McGraw Hill.

Petsoulas, C. (2001). Hayek’s liberalism and its origins: His idea of spontaneous order and the scottish enlightenment. New York: Routledge.

Phillips, R. (1997). Stakeholder theory and a principle of fairness. Business Ethics Quarterly, 7(1), 51–66.

Polanyi, K. (1944/2001). The great transformation: The political and economic origins of our time. 2nd ed. Boston: Beacon Press.

Porter, M., & Kramer, M. (2011). Creating shared value: How to reinvent capitalism and unleash a wave of innovation and growth. Harvard Business Review, 89(1/2), 63–70.

Ricardo, D. (1817). On the principles of political economy and taxation. London: Murray, Rogers, Everett.

Rosenberg, R., Gonzalez, A., & Narain, S. (2009). The new moneylenders: Are the poor being exploited by high microcredit interest rates? CGAP Occasional Paper No. 15. Washington, DC: CGAP.

Sandberg, J. (2012). Mega-interest on microcredit: Are lenders exploiting the poor? Journal of Applied Philosophy, 29(3), 169–185.

Sertial, H. (2012). Hybrid entities: Distributing profits with a purpose. Fordham Journal of Corporate & Financial Law, 17, 261–297.

Sison, A. J. G. (2007). Toward a common good theory of the firm: The tasubinsa case. Journal of Business Ethics, 74(4), 471–480.

Sison, A. J. G., & Fontrodona, J. (2011). The common good of business: Addressing a challenge posed by Caritas in Veritate. Journal of Business Ethics, 100, 99–107.

Smith, A. (1759/1976). The theory of moral sentiments. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Solomon, R. (1992). Corporate roles, personal virtues: An Aristotelian approach to business ethics. Business Ethics Quarterly, 2(3), 317–339.

Solomon, R. C. (2004). Aristotle, ethics and business organizations. Organization Studies, 25(6), 1021–1043.

Taylor, C. R. (2009/2010). Carpe crisis: Capitalizing on the breakdown of capitalism to consider the creation of social businesses. New York Law School Law Review, 54, 743–758.

Testart, A. (2007). Critique du don: Études sur la circulation non marchande. Paris: Syllepse. The Holy Bible. Book of Proverbs. King James Version.

Trachtenberg, Z. M. (1993). Making citizens: Rousseau’s political theory of culture. New York: Routledge.

Uelmen, A., & Bruni, L. (2006). Religious values and corporate decision making: The economy of communion project. Fordham Journal of Corporate & Financial Law, 11, 645–648.

Wals, A. E. J. (2007). Social learning towards a sustainable world: Principles, perspectives, and praxis. Wageningen: Wageningen Academic Publishers.

Yunus, M. (2007). Banker to the poor: Micro-lending and the battle against world poverty. New York: Public Affairs.

Yunus, M. (2011). Building social business: The new kind of capitalism that serves humanity’s most pressing needs. New York: Public Affairs.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Jackson, K.T. Economy of Mutuality: Merging Financial and Social Sustainability. J Bus Ethics 133, 499–517 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-014-2408-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-014-2408-0