Abstract

In this article, we discuss and compare various positions in leadership theory through the perspective of Kierkegaard’s modes of existence. After a brief presentation of the three modes of existence—aesthetic, ethical and religious—and a description of the ironic–reflective interpretation of the change process (expanding contexts), we synthesize leadership theories into the three main positions of instrumental, responsible and spiritual. Later, we compare and integrate the different positions in leadership theory with the three modes of existence. We argue that the various positions in leadership theory represent different modes of existence. This means that leaders (or cultures) anchored within the aesthetical mode of existence tend to prefer the instrumental position, leaders (or cultures) anchored in the ethical mode of existence tend to prefer the responsible position, and leaders (or cultures) anchored in the religious mode of existence tend to prefer the spiritual position. In accordance with this line of reasoning the ironic–reflective interpretation of Kierkegaard’s three modes of existence gives a relevant explanation for development of leadership theory, and we delve deeper into some key dimensions in the expanding contexts of ontology, epistemology, ethics, the image of man and organizational ends. We conclude that it is necessary to start a process of transition in the mode of existence and in leadership theory in order to cope with the underlying patterns of the natural, cultural and economic crises we are facing today.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Humanity is now facing an unprecedented challenge, requiring us to rethink radically the way we see the world and organize our society. Never previously in the history of civilization have humans faced so many interconnected global crises of our own making—from ‘financial scandals, human rights violations, environmental side effects’ (Palazzo and Scherer 2006, p. 71) to eco-system and community breakdown, the extinction of many species and social inequality. If we do not realize that these crises are symptoms of a deeper moral, ethical and spiritual crisis, no technical fast-fixes can help us (Eisenstein 2011). Creating a life-enhancing world and a viable future is about justice—for humans, for the Earth and for future generations of all living species. Palazzo et.al (2012) conceptualize the interplay of psychological and sociological forces on three different levels, namely ‘the individual sense making, the decision-making situation and the ideological context’ (Palazzo et al. 2012, p. 324). The interconnection of economics, leadership theories, human development and existential perspectives are thus central issues in order to understand the patterns of potential underlying crises. In this article, we discuss and compare various positions in leadership theory using the perspective of Kierkegaard’s modes of existence to explore these questions.

We start with a brief presentation of the three modes of existence: aesthetic, ethical and religious and describe the change process from the ironic–reflective interpretation. Then, we synthesize leadership theories into three main positions: instrumental, responsible and spiritual. Subsequently, we compare and integrate the different positions in leadership theory with the three modes of existence. We argue that the different positions in leadership theory represent different modes of existence. This means that leaders (or cultures) anchored within the aesthetical mode of existence tend to prefer the instrumental position, leaders (or cultures) anchored in the ethical mode of existence tend to prefer the responsible position and leaders (or cultures) anchored in the religious mode of existence tend to prefer the spiritual position in leadership theory. To implement a position in leadership theory which does not harmonize with the mode of existence of the leader (or culture) is problematic. Hence; changing from one position of leadership theory to another implies a corresponding change in the mode of existence, or vice versa. We argue that the ironic–reflective (expanding contexts) interpretation of Kierkegaard’s three modes of existence gives a relevant explanation for development of leadership theory, and we delve deeper into some key dimensions in the expanding context of the ironic–reflective interpretation: ontology, epistemology, ethics, the image of man and organizational ends. To understand and solve some of the most urgent challenges the global society is facing, we conclude that a change towards spiritual leadership is of great importance.

Kierkegaard’s Modes of Existence

Kierkegaard made a distinction between three modes or spheres of existence: the aesthetic, the ethical and the religious. Before entering into any of the different modes, the individual is no more than an anonymous member of a crowd. The individual finds it much easier and safer ‘to be like the others, to become a copy, a number, along with the crowd’ (Kierkegaard 1989, p. 36). The story Kierkegaard tells is that of a person‘s inner development from being ‘untruth’ to being ‘in the truth’, how he recognizes, through an appeal to his own inner experience, the considerations that lead him to adopting a particular mode of living and the limitations it imposes.

The Aesthetic Mode of Existence

Aestheticism manifests itself at many diverse levels of sophistication and self-consciousness and expresses itself in levels far beyond those of the mere pursuit of pleasure for pleasure’s sake. The aesthetic man is governed by sense and impulse and has a tendency to interpret himself as if he is ‘on the stage’ and life is not to be taken too seriously. Choice is cynical: ‘it does not matter what I choose because it will turn out equally well or, alternatively, equally badly’ (Jones 1975, p. 220). If he does ever adopt long-term goals or wish to chase certain maxims, this is done in a purely ‘experimental’ spirit. The man who lives aesthetically is not really in control, either of himself or his situation, he tends to live in the moment, ‘for whatever the passing instant will bring in the way of entertainment, excitement, interest’ (Gardiner 2002, p. 48). This means he will decide otherwise as soon as the idea no longer appeals to him. ‘Or, rather, the form of his life is its very formlessness, self-dispersal on the level of sense’ (Copleston 1985, p. 342). What is common to people in this sphere is that ‘they live constantly (…) in the moment, absorbed in moods, governed by caprice’ (Cooper 1996, p. 331). Committed to nothing permanent or definite, dispersed in sensuous immediacy he may think one thing at a given time and the exact opposite at some other time; ‘his life is, therefore, without “continuity”, lacks stability and focus, changes course according to mood or circumstance, is like a witch’s letter from which one sense can be got now and then another, depending on how one turns it’ (Gardiner 2002, p. 48).

The essential feature of a person in the aesthetic stage is that he avoids any commitment; ‘whether personal, social, or official, which would limit his field of choice and prevent him from following whatever is immediately attractive’ (Kenny 1998, p. 299). However, it should never be claimed that the aesthetic man is always governed by mere impulse; he may also be reflective and calculating. The aesthetic person thinks of his existence as one of freedom, but the freedom in this mode of existence is, in fact, extremely limited. External factors such as possessions, power and affection of and for other human beings are of great importance. Internal factors like health and physical beauty are also important for the aesthetics. ‘At this stage, we do not involve ourselves ethically and seriously in life, but remain passive observers’ (Skirbekk and Gilje 2001, p. 340). The aesthetic man depends on conditions outside him and on external stimulation, and hence is contiguous and subject to the occasion.

The Ethical Mode of Existence

In the ethical sphere life is serious; the person takes his place within social institutions and accepts the obligations which flow from them. A man accepts the determination of moral standards and obligations, ‘the voice of universal reason, and thus gives form and consistency to his life’ (Copleston 1985, p. 342). The ethical sphere transfigures the aesthetic sphere, and determinate duties and responsibilities are of great importance. A person who lives such a life must also acknowledge specific norms and values which he regards as valid for himself and others. The fundamental categories for the ethical are “good and evil” and “duty”, and they are referred to as if they had a meaning necessarily shared by all who used them’ (Gardiner 2002, p. 55). Choice becomes problematic and serious since ‘ethical men must decide how their code applies to the various concrete situations in which they find themselves’ (Jones 1975, p. 220). He gives up the perpetual aesthetic life and forsakes pleasures of fleeting affairs. ‘The ethical man may take account of human weakness, (…) but he thinks that it can be overcome by strength of will, enlightened by clear ideas’ (Copleston 1985, p. 343). The ethical person stands out from the crowd; ‘he takes his place in society not unthinkingly but by an act of self-conscious choice’ (Kenny 1998, p. 299). He was born into particular circumstances, but he has chosen his code instead of merely drifting into it. By such inward understanding and critical self-exploration, ‘a man comes to recognize, not only what he empirically is, but what he truly aspires to become’ (Gardiner 2002, p. 54). Since the ethical mode includes strict demands on the person, he will become vividly conscious of human weakness and this brings him to a sense of guilt and a consciousness of sinfulness.

The Religious Mode of Existence

In this mode ‘it is faith in God which determines one’s life—a faith which can conflict with ethical demands’ (Cooper 1996, p. 332). Desire is, therefore, absolutely sound, and it is not ‘a question (here) of desire in a particular individual but of desire as a principle, spiritually specified’ (Kierkegaard 2004, p. 93). Ethical and religious modes are not differentiated by two kinds of acts, for the same act may be done from a merely ethical motive (or indeed from an aesthetic motive) as from a religious motive. Nor is it merely the difference between calculation and commitment, for a man may be passionately serious at the ethical stage. ‘The difference (…) is that between commitment to (…) a cause or code and commitment to God’ (Jones 1975, p. 222).

Kierkegaard refers to the biblical story of God’s command to Abraham to kill his son Isaac as a sacrifice. But, an ethical hero, such as Socrates, laid down his life for the sake of a universal moral law, ‘Abraham’s heroism lay in his obedience to an individual command of God’ (Kenny 1998, p. 299). If Abraham is a hero, as the Bible says, it can only be from the standpoint of faith. ‘Abraham’s act transgressed the ethical order in view of his higher end or telos outside it’ (Kenny 1998, p. 300). Kierkegaard stresses that faith is not the outcome of any objective reasoning. What he means is that the man of faith is directly related to a personal God whose demands are absolute and cannot be measured simply using the standards of human reason. The infinite or absolute ‘other’ transcends human reason and understanding, ‘the paradox of faith is this, that the individual is higher than the universal, that the individual (…) determines his relation to the universal by his relation to the absolute, not his relation to the absolute by his relation to the universal’ (Kierkegaard 2012, p. 58).

Interpretations of the Process of Development

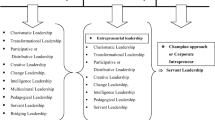

According to Skirbekk and Gilje (2001), there are different well-founded interpretations of the process of development in Kierkegaard’s stages of modes of existence; the edifying, the synthesizing and the ironic–reflective. We focus on the ironic–reflective interpretation which is characterized as an expanding context of consciousness. Existential choice initiates the process through which our attitude towards life is changed (Fig. 1).

In this interpretation, the aesthete emerges as one maintaining an inner distance from life, in which life is ethically empty because everything is just as valid as anything else. Consequences are irrelevant. ‘In this sense, the aesthete is the incarnation of European nihilism in the Nietzschean sense’ (Skirbekk and Gilje 2001, p. 342). The leap to the ethical mode of existence contains the choice in which people see themselves as an end. ‘The catchwords may be self-consciousness and the will to conduct our own life, or passion and sincere inwardness’ (Skirbekk and Gilje 2001, p. 342). ‘To have an authentic existence one must not be a mere spectator or passenger in life, but seize control of one’s own destiny’ (Kenny 1998, p. 300). The ethicist overcomes the anxiety and existential despair of the aesthete. For Kierkegaard, only the self-conscious choice of our own life is morally decisive. Faced with this challenge, the ethicist becomes aware that his own powers are insufficient to meet the demands of the common moral law, and ‘religion is the only power which can deliver the aesthetical out of its conflict with the ethical’ (Kierkegaard 2012, p. 78). To escape from this, the person must expand ‘from the ethical sphere to the religious sphere’ (Kenny 1998, p. 299). In the struggle with guilt and angst, ‘we have a passionate and ironic–reflective relationship to ourselves and the historical God’ (Skirbekk and Gilje 2001, p. 343).

Positions in Leadership Theory

In the following section, we place leadership theories into three different positions: instrumental, responsible and spiritual.

The Instrumental Position

Taylor’s (2011) philosophy of scientific management contributed to a more effective utilization of human resources. Workers represent a potential that can be exploited through individualized training based on specific principles of action and scientific studies of how different tasks can be performed more effectively are central. Since workers are lazy by nature and dislike working, their avoidance is reinforced when several workers come together in groups. By individualizing the work tasks and assigning each worker to one manager, it is possible to reduce this kind of organized laziness. As a result, there is a need for an authoritarian hierarchical organizational structure where everyone obeys the orders of his or her senior manager. Salary is the most important and perhaps the only motivation to work, and the workers can increase their remuneration by following the leaders’ work instructions. Authoritarian management models may be supplemented or replaced by democratic models based on participation. McGregor (1960) and the human relations tradition argued that governance based on democratic principles provides increased efficiency and increased profitability. Rewards in terms of increased self-esteem and respect from colleagues are at least as important as the increases in salary. An ability to use imagination, ingenuity and creativity in solving organizational challenges exists in nearly all people, and the efficiency and profitability depend on management’s ability to facilitate the conditions for the workers. Despite major differences between the two theories, both are characterized by a focus on efficiency and profitability.

The Responsible Position

Participative management (Ouchi 1981) is based on the assumption that people in the organization are interdependent and the development of a feeling of community counteracts the selfishness and dishonesty in the firm. Care and altruistic behaviour are natural results of close social relationships. ‘Organizations can be effective economically and satisfying emotionally only by maintaining a delicate balance between intimacy on the one hand and objective and explicitness in the other’ (Ouchi 1981, pp. 53–54).

Profitability is perceived as a reward for offering customers high-quality products, helping employees in their personal development and practising social and environmental responsibility. Collective organizational values are communicated through symbols and myths and help the employees to experience and practice co-responsibility. ‘Tacit’ knowledge is of great importance, and the only way to change human behaviour is through cultural development. ‘The process of participative management, once begun, is largely self-sustaining because it appeals to the basic values of all employees. And in fact the process promotes greater productivity and efficiency through better coordination’ (Ouchi 1981, p. 110).

The importance of values has created an extension of several versions of network- and stakeholder theories and value-based leadership theories, where ‘management is the act of ‘‘handling’’ things, while stewardship is the art of taking care of what’s been entrusted for safekeeping: in this case, the interests of customers, employees, society, future generations, and nature itself’ (Miller and Miller 2008, p. 12). A common purpose, or value-system, is better for ‘controlling’ businesses in networks rather than command and conviction towards ‘wealth creation for the optimum benefit of all stakeholders’ (Miller and Miller 2008, p. 13). Cooperative interactions between the individuals stimulate the creativity of the business networks. ‘We are constantly called to be in relationship—to information, people, events, ideas, life. Even reality is created through our participation in relationships’ (Wheatley 2006, p. 166). Employees are encouraged to question the company’s core values, strategies and concrete actions, and they are treated as ‘individual companies’. Positions and promotions are no longer the focal point for career development; variety and personal development are assumed to be superior appraisals. Participative management and value-based leadership focus on collective values such as social and environmental responsibility.

The Spiritual Position

‘It is an undeniable reality that workplace spirituality has received growing attention during the last decade’ (Gotsis and Kortezi 2007, p. 575). Several authors have offered a variety of definitions of spirituality. A basic definition of spirituality is ‘a worldview plus a path’ (Cavanagh and Bandsuch 2002, p. 110). Mitroff and Denton (1999, p. 86) define spirituality as the ‘basic feeling of being connected with one’s complete self, others and the entire universe’. Miller and Miller (2008, p. 17) define spirituality as the ‘breath’ animating the individual and the community, the pervading breath of aspiration, adventure and creative powers, ‘energy and consciousness are qualities of the “common ground” of creation’. These definitions are in accordance with Pruzan and Pruzan Mikkelsen (2007) who argue that people long to experience inner coherence and meaning in their work. They call for spiritual leadership where corporate goals are not isolated from the objectives concerning positive social development.

Pruzan (2012) argues that we should develop our empathy, the ability to immerse ourselves in the experiences, thoughts and feelings of others and to promote the common good. Spirituality connects individuals, organizations and society, and ‘spirituality is simply a part of what it means to be human, inseparable from the human enterprise in business’ (Miller and Miller 2008, p. 20). Links between spirituality and leadership are rooted in ‘the recognition that we all have an inner voice that is the ultimate source of wisdom in our most difficult business and personal decisions’ (Fry and Cohen 2009, p. 270).

According to Fry (2003), spiritual leadership is developed within a model in which intrinsic motivation is more important than external motivation related to efficiency and profitability. Relationships are characterized by altruistic love, hope and faith. Altruistic love is defined as a sense of wholeness, harmony and ‘well-being’ based on selflessness and thoughtfulness towards oneself and others. Hope refers to desires that one expects to be fulfilled; faith is stronger and implies that one is sure that something will happen, even if no evidence of this exists. People with hope and faith have a vision of ‘where they are going, and how they get there, they are willing to face opposition and endure hardship and suffering, to achieve their goals’ (Fry 2003, p. 713). Hope and faith are the sources of a belief that the organization’s vision, purpose or mission can be achieved. This, therefore, means a change in the primary goal of organizations, ‘spiritual fulfillment and service to society, where both are derived from and motivated by a transcendent consciousness’ (Miller and Miller 2008, p. 19) and ‘wealth creation is simply a natural result of excellence in living and working from a spiritual context’ (Miller and Miller 2008, p. 20).

Connecting Leadership Theory and Kierkegaard’s Modes of Existence

In accordance with Palazzo et.al (2012, p. 325), we argue that the different modes of existence could be characterized as frames or ‘(mental) structures that simplify and guide our understanding of a complex reality’. Ethical blindness is defined ‘as the temporary inability to see the ethical dimension of a decision at stake’ (Palazzo et al. 2012, p. 325). The various degrees of ‘visual impairment’ or consciousness in such a situation can be explained by the different modes of existence. Ethical blindness comes from the interplay between tendencies towards rigid framing and contextual pressures. Sense-making and decision-making are always embedded within an ideological context, and according to Zsolnai (2004), the ethical fabric of the economy determines which face of the moral economic man predominates. The relative cost of ethical behaviour will vary in the different institutional contexts in which individuals and their organizations are embedded and must not be neglected. At one end of the scale, we find economics and management systems based on mechanical assumptions strengthening the narrowly oriented instrumental position, and at the other end we find economics and leadership theory grounded in an organic worldview nourishing the spiritual position (Storsletten and Jakobsen 2013).

In the following paragraphs, we compare and integrate the positions in leadership theory with the three modes of existence in Kierkegaard’s theory of human development. We argue, firstly, that the instrumental position shares several similarities with the aesthetic mode of existence. Secondly, we argue that the responsible position has some parallels of significance with the ethical mode. Thirdly, the spiritual position and the religious mode of existence also have much in common.

The Instrumental–Aesthetic Connection

Both scientific management and human relations provide important input for improving the efficiency of many companies based on more effective utilization of human resources. Even if there is a huge difference between the negative and the positive image of man in the two theories, both focus on instruments for increased efficiency and increased profitability. Focus on salary and facilitating the conditions to develop the individual potential in each worker are instruments for reaching corporate objectives. In harmony with this description, people living in the aesthetic mode of existence, according to Kierkegaard, depend on conditions outside themselves. In addition, such persons will not involve themselves ethically and seriously in life; they live in and for the moment. People living aesthetically are in fact not in control, neither of themselves nor of their situation. This fits in within instrumentally oriented leadership theories that, to various degrees, position exterior surroundings and controlling principles as the overall focal point for goal achievement.

Owing to many concurrent characteristics, the aesthetic mode of existence and the instrumental position strengthen each other. Therefore, we can conclude that leaders in the aesthetic mode of existence are well suited for working within the instrumental position of leadership. Since all energy is concentrated on increasing the egocentric utility (or profit maximization), social and environmental challenges are only focused as long as they can contribute to company’s profit maximization. Companies characterized by an instrumental–aesthetical perspective are basically focused on short-term profits, and they will use their resources solely to get the biggest possible profits, regardless of the consequences or the risk involved. Renee O’Farrell argues that ‘some companies employ this strategy exclusively, constantly jumping on the next big trend’ (http://smallbusiness.chron.com).

The Responsible–Ethical Connection

Participative and value-based leadership theories provide important input to an understanding indicating that the company is inextricably linked with cultural and ecological conditions. An organization’s collective values should help the employees in their personal development and help them experience and practise social and environmental co-responsibility. At the ethical stage, the person accepts the duties and obligations characterizing social institutions and the local culture. The ethical person takes his place in society through an act of self-conscious choice. As opposed to aestheticists who are focused on externals, the ethicists direct their attention towards their own nature. This is closely associated with the ideas of self-knowledge, self-acceptance and self-realization. The ethical subject shares more similarities with the person who regards himself as a goal and uses his power constantly to control and develop his talents, characteristics and passions. For such a person surrendering to the arbitrary authorities of outside circumstances and incalculable contingencies is out of the question; the ethical individual expresses the universal in his life and acts in accordance with fundamental categories such as ‘good and evil’ and ‘duty’. The ethical mode of existence shares similarities with the yearning for the uncomplicated applicability of general, public or organizational shared standards in participative management and value-based leadership.

In that the ethical mode of existence and the responsible position are based on many common assumptions, it is reasonable to conclude that leaders in the ethical mode of existence are well adjusted to the responsible position. They give priority to social and environmental responsibilities as long as the activities are within the accepted values and norms in society. On their web site VOLVO give a description of their business which closely resembles the characteristics of the responsible-ethical connection. They point out that if a company is non-profitable it will face problems in the future to raise capital for investment in environmentally enhanced technology and improvements in the workplace. If it fails to address environmental issues, there is a huge risk of acquiring a bad reputation which in turn will lead to a loss of customers and profit. In addition, if the company ignores human rights and social issues it can make it difficult to recruit and retain employees with the right skill set. (http://www.volvogroup.com).

The Spiritual–Religious Connection

Spiritual leadership requires a radical change in our understanding of reality. Spiritual leadership represents a fundamental change as the company will be perceived as an integral part of a larger community in which the objective lies far beyond the company’s traditional boundaries of mere profit and loss. Leadership with spiritual grounding assumes and requires a complete change in the mindset, amongst other things, leading to mechanical solutions being perceived and understood in terms of an organic worldview (spiritual leadership). To interpret organic solutions by means of a mechanical perception of reality, as in the case of scientific management, is a profoundly different matter. Moreover, interpreting participative management and value-based leadership in an organic perspective does not necessarily rule out all or any moral requirements but the absolute sovereignty of the ethical can no longer be assumed within a context of spiritual leadership. It is rather transcended through a spiritual perspective in which the self-sufficiency of morality, regarded as a socially established and universally acknowledged institution, is explicitly challenged. The religious subject is prepared to resist the dictates of ordinary morality. Against every rational expectation, he still believes that he in some way will ‘be given back’ that which he has been required to sacrifice when determining his relation to the universal from the absolute. Leaders in the religious mode of existence are motivated by an intuitive experience of unity and coherence, and we find it likely that they feel attracted to the spiritual position in leadership theories.

In this way, we will identify leaders with the potential to change radically the frame of reference and hence make fundamental changes in the responsibility for the social and natural environments. According to Lindner (2012), we will find leaders with the courage, to step off the beaten track of familiarity and see everything from a new and more worthwhile perspective. Weleda is a company which clearly demonstrates the spiritual–religious connection. On their web site, they explain that since it was established, Weleda has offered products that support ‘human beings in their personal development, in maintaining, promoting and restoring their health and in their efforts to achieve physical well-being and a balanced lifestyle’ (http://www.weleda.com). Weleda’s economic approach is based on the existence of an objective, intellectually comprehensible spiritual world that leads to a new focus on people and nature. As a socially oriented company, Weleda attaches great importance to providing its employees, suppliers and partners with a secure environment which offers scope for mutual development.

Development Enlightened by the Ironic–Reflective Interpretation

Based on the ironic–reflective interpretation of Kierkegaard’s modes of existence, we have described the connection between the three modes of existence and the three positions in leadership theory as a process of expanding consciousness. Later levels integrate and reinterpret the achievements of earlier levels. For example, when the means-end relation at the instrumental–aesthetic connection is interpreted from the consciousness characterizing the spiritual–religious connection, the relation between the variables is changed. Efficiency and profits are no longer ends in themselves anymore but rather the means to reach individual, social and ecological ends.

We will now concentrate on leadership theory as enlightened by the ironic–reflective interpretation and discuss the change process as it affects ontology, epistemology, ethics, image of man and organizational ends.

Ontology

The instrumental position is based on a mechanical worldview characterized by the idea that pieces of matter are isolated entities (atomism), related to each other only externally. Both the organization and the market are nothing more than mere mechanisms based on the interplay between egocentric actors seeking their own ends. One of the most important consequences of the mechanical worldview is that the whole universe is completely causal and deterministic and offers no capacity whatever for creativity, spontaneity, self-movement or novelty. Interpreted within the mechanical worldview, the actors in the market are supposed to act independently of one another in order to maximize their self-interests.

A more responsible position is anchored in a cultural worldview based on the precondition that people in organizations have common beliefs, attitudes and skills. It is impossible, according to the cultural world view, to understand fully a person without understanding his or her culture. In the context of leadership theory, culture is defined as the patterns of behaviour, beliefs and values shared by a group of people within the organization or the wider society. Culture includes everything from language and superstitions to moral beliefs and food preferences. Any social or cultural force influencing human lives is important to the cultural perspective. Business administration and leadership theory can, according to the cultural perspective, only be fully understood, if culture, ethnic identity and gender identity are taken into consideration (Fig. 2).

The spiritual position is based on an organic worldview in which ‘life’ and ‘mind’ are interwoven with matter and motion. Patterns, designs and emerging parts of this worldview manifest itself in most of the things that are called alternative, holistic or ecological today. It is the essence of life that it exists for its own sake, as an intrinsic value. Essentially, we cannot understand physical nature or life unless we fuse them together as essential factors in the composition of the whole universe. This interconnectedness is non-linear in the sense that freedom is considered to be the claim for self-assertion. Spontaneity and originality of decision are the supreme expressions of individuality. In a civilised society, the general end is that the variously coordinated organizations or companies should contribute to community life. In this perspective, the individual and the community make each other and require each other at the same time. Organizations simply cannot be reduced to parts in a mechanical system, governed by law and scientific rationality—that is the most important consequence of the organic worldview. Instead, the market consists of partners integrated in a living system. A more complex and dynamic framework takes into consideration that economic behaviour is both multi-faceted and context dependent.

Epistemology

Inborn complex patterns of behaviour (instincts) characterize the instrumental position. Behaviour that occurs under the influence of the major instincts ‘often consists of chains of more or less stereotyped patterns of behaviour called fixed action patterns’ (Sheldrake 2009, p. 167). Any behaviour is instinctively motivated if performed without being based upon prior experience (that is, in the absence of learning) and is, therefore, an expression of innate biological factors. Humans have an inborn tendency to seek pleasure and avoid pain (Blackburn 2001). Utility and profit maximization are examples of instinctively motivated behaviour in the instrumental position. Instincts exist in every member of the species and cannot be overcome by force of reason or will. However, the absence of volitional capacity must not be confused with an inability to modify fixed action patterns. For example, people may be able to modify a stimulated fixed action pattern by consciously recognizing the point of its activation and simply stop doing it, whereas animals without sufficiently strong volitional capacity may not be able to disengage from their fixed action patterns, once activated.

Intelligence characterizes the responsible position. Today, researchers emphasize that there is no single form of intelligence. Rather than seeing intelligence as dominated by a single general ability, they classify intelligence into several different forms. According to Sternberg, there are three types of intelligence: analytical, creative and practical (Sternberg 2005). Analytical intelligence reflects how an individual relates to the internal world and refers to the ability of the mind to arrive at correct conclusions about what is true and how to go about solving problems. Creative intelligence (Sternberg 2006) reflects how the individual connects to the internal and the external world. It involves insights, synthesis and the ability to react to novel stimuli and situations. Practical intelligence reflects the individual’s ability to relate to concrete tasks in the external world. It refers to individual competence in dealing with everyday challenges. Leadership theory in the responsible position presupposes that economic activity is a result of intelligent behaviour. It refers to individual competence to deal with everyday challenges (Fig. 3).

In the spiritual position, intuition is introduced as a source of knowledge. Intuition is defined as understanding or knowing without conscious recourse to thought, observation or reason. ‘Intuition is the conscious experience, within what is purely spiritual, of a purely spiritual content’ (Steiner 1995, p. 136). It is not unusual to conceive of intuition as somehow mystical, referring to the ability to acquire knowledge without the use of reason. Some scientists contend that intuition is associated with innovation in scientific discovery. According to Popper, ‘every discovery contains an “irrational element”, or “a creative intuition”’ (Popper 2002, p. 8).

Intuition is often discussed in writings of spiritual thought, including spiritual leadership. Contextually, there is often an idea of a transcendent and more qualitative mind of one’s spirit towards which a person strives, or towards which consciousness evolves. Typically, intuition is regarded as a conscious commonality between earthly knowledge and the higher spiritual knowledge and appears as flashes of illumination. It is asserted that, by definition, intuition cannot be assessed by means of logical reasoning (Popper 2002).

Ethics

Ethical egoism characterizes the instrumental position in leadership theory. According to Ketola; ‘Companies seem to have had an inherent tendency towards utilitarianism or egoism ever since the times of Adam Smith’ (Ketola 2008, p. 421). Ethical egoism claims that it is necessary and sufficient for an action to be morally right if it maximizes one’s own self-interest. Ethical egoism pre-supposes a mechanism (‘the invisible hand’) ensuring that no individual egoist pursues his or her own interests at other egoists’ expense. Following Adam Smith’s theory, based on ethical egoism, an action is morally right if the decision makers freely decide in order to pursue either their (short-term) desires or their (long-term) interests. Consequently, Smith avoids the serious problem connected to the fact that man only has limited insights into the consequences of his own actions. Based on this reasoning, Smith draws the conclusion that it is impossible to calculate the impact individual actions have on other peoples’ well-being.

Utilitarianism—another version of consequentialism—is an impartial or impersonal moral view accepting that morality is agent independent. Its aim is to maximize ‘the utility or happiness of the greatest number of people’ (Renouard 2011, p. 86). Relevant utilitarian criteria are pleasure and pain, as the sole good and bad things in human lives (ethical hedonism). According to utilitarian ethics, the outcome of an action is more important than the intentions. Utilitarian principles can be summarized in the following way: the goodness of a state of affairs could be assessed by looking at the sum total of all the utilities in that state, and it requires that every choice could be ultimately determined by the goodness of the consequent states of affairs. Ethical behaviour is ‘understood as the maximization of the global well-being or material growth in a society’ (Renouard 2011, p. 86).

The responsible position is anchored in duty ethics. Duty ethics is less abundant than utilitarian, because ‘the duty ethical approach is considered normative’ (Ketola 2008, p. 421). Duty ethics argues that it is not the consequences of actions that make them right or wrong, but rather the motives of the person carrying out the action. ‘The only thing good in itself, then, is a good will’ (Blackburn 2001, p. 102). To act morally, one must act purely from duty. Those things usually thought to be good, such as perseverance and pleasure, fail to be intrinsically good. Pleasure, for example, appears not to be good without qualification, because when people take pleasure in watching someone suffer this seems to make the situation ethically worse. We conclude that there is only one thing that is truly good: nothing can possibly be called good, except a good will (Fig. 4).

In duty ethics, the consequences of an act cannot be used to determine that the person has a good will; good consequences can arise by accident from an action motivated by a desire to cause harm to an innocent person, and bad consequences can arise from an action that was well motivated. People act out of respect for the moral law when they act in some way, because they have a duty to do so (Blackburn 2001). The only thing that is truly good in itself is a good will, and a good will is only good when the willer (person who wills) chooses to do something because it is that person’s duty, i.e. out of respect for the law.

Virtue ethics characterizes the spiritual position in leadership theory. Carette and King argue that ‘spirituality has become the ‘‘brand label’’ for the search for meaning, values, transcendence, hope and connectedness in modern societies’ (McGhee and Grant 2008, p. 62). Cavanagh and Bandsuch (2002, p. 112) introduce virtue ethics as a benchmark to help managers ‘recognize spiritualities that help to develop virtue and character’, in addition they claim that such spiritualities are appropriate for the workplace. A good and moral life, according to virtue ethics, is a life responsive to the demands of the world. Virtue ethics’ central concepts are good judgment, justice, courage and self-control. To possess a virtue is to be a person with a given complex mindset. ‘The most significant aspect of this mindset is the wholehearted acceptance of a certain range of considerations as reasons for action’ (Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy 2012). Virtue ethics focuses on the moral person’s character characterized by the ability to be aware of, to identify and to handle moral dilemmas in real-life situations. In other words, virtue ethics and spirituality represent ‘a higher level of understanding that enables the contextualization of lower levels’ (McGhee and Grant 2008, p. 62). Gotsis and Kortezi (2007, p. 577) argue that virtue ethics meets the main spirituality exigencies, character education and well-being. They claim that it is relevant ‘to develop a more inclusive framework for constructing and implementing spirit at work’.

Image of Man

In the instrumental position, the economic actor is described as narrowly self-interested. Economic actors make judgments towards their subjectively defined ends. Using rational assessments, the economic actor attempts to maximize utility as consumer and economic profit as producer. Economic man is a metaphor, indicating that economic actors act according to the ideas of ethical egoism. Economic man is seen as rational in the sense that well-being as defined by the utility function is optimized given perceived opportunities. That is, the individual seeks to attain very specific and predetermined goals to the greatest extent at minimum possible cost (Ingebrigtsen and Jakobsen 2009).

This kind of rationality does not say that the individual’s actual goals are rational in some larger ethical, social, or human sense, only that he tries to attain them at minimal cost. Only naïve applications of the economic man assume that this hypothetical individual knows what is best for his long-term physical and mental health and can be relied upon always to make the right decision for himself. Smith argued that the principle of pursuit of self-interest was acceptable because it produced a morally desirable outcome for society, given the assumption that economic decisions take into account sympathy and fellow-feeling. In the responsible position, the economic actors are described as social. Man is by nature social. Society is something that precedes the individual (Ingebrigtsen and Jakobsen 2009) (Fig. 5).

The spiritual position is based upon an idea that economic actors have a cosmic perspective characterized by having a sense of being part of the whole of life. The cosmic man has much in common with ‘Philosophy of Organism’ (Whitehead 1967) and ‘Deep Ecology’ (Næss 1989). Cosmic man is rooted in the idea that the superior goal of sustainability and quality of life cannot be reached within abstracted mechanistic or social worldviews. According to Kohlberg (1964), the ‘cosmic man’ is a person who engages scientists, humanists, modern men and women in a fundamental enquiry concerning basic questions such as humanity’s relationship to the source and ground of its being.

Organizational Ends

The instrumental position is based on shareholder value. Shareholder value assumes that corporations are primarily the means of its owners and that their corporate purpose is to maximize long-term shareholder value. Shareholder value is a business term (micro-perspective), sometimes phrased as shareholder value maximization or as the shareholder value model (Friedman 1970). Proponents of the shareholder value model believe that the success of an organization can be measured on a monetary scale by share price, dividends and profit. Shareholders obviously have a financial interest to invest in companies with high profitability. While there may sometimes be short-term tension between profits and ethics, ethical behaviour should be viewed as being consistent with a desire to maintain long-term profitability and financial soundness. Shareholder value proponents regard ethics as a means rather than as an end/purpose in itself. Hence, they do not believe that social responsibility is a matter for companies at all and think that society is best served by companies pursuing self-interest and economic efficiency (Fig. 6).

Stakeholder theory is the perspective characterizing the responsible position. All companies have responsibilities towards the welfare of a range of actors with a stake in what the company does. A firm’s stakeholders are individuals, groups or other organizations affected by, or themselves affecting, the firm’s decisions and actions (Carroll 1991). The various stakeholders may have competing, even conflicting, interests that need to be balanced. Clearly, different groups of stakeholders will place a different emphasis on what they expect from their company. Depending on the specific firm, stakeholders may include governmental agencies, NGOs, employees, shareholders, suppliers, distributors, the media and the community in which the firm is located.

A holistic perspective is essential to the spiritual position. Earth is a dynamic living organism whose complex processes have maintained the conditions for life to keep on evolving over millions of years. Humans are integral parts of this living process and depend on it for their well-being. Businesses are co-responsible for ensuring a mutually enhancing way to live on our planet, our only home. A Buddhist economic strategy (Zsolnai 2008) is a major alternative to the western economic mindset. Buddhism is centred on want negation and purification of the human character and leads to happiness, peace and permanence.

The Gaia (macro) perspective is essential, because all decisions have an influence and are themselves influenced by both lesser and greater wholes. A business, a community, or indeed the global community, cannot be managed without ‘looking inward to the lesser wholes that combine to form it, and outward to the greater wholes of which it is a member’ (Savory and Butterfield 1999, p. 17). In this perspective, the goal is quality of life, an expression of how people want their lives to be, and what they ultimately want to accomplish together.

Concluding Remarks

According to Eisenstein, the present convergence of crises, ‘in money, energy, education, health, water, soil, climate, politics, the environment, and more—is a birth crisis, expelling us from the old world into a new’ (Eisenstein 2011, p. xx). Basic principles of modern Western economics such as profit maximization, cultivating desires, introducing markets, instrumental use of the world and self-interest-based ethics have now been severely and rigorously challenged. Buddhist economics (Zsolnai 2008) proposes alternative principles such as minimizing suffering, simplifying desires, non-violence, genuine care and generosity. Lindner (2012) follows though by adding how destructive competition must not be chosen at the expense of life-enhancing cooperation. Instead of firing up the engine of capitalism and wealth creation by prioritizing selfishness, individualism and narcissism, the ability to say yes to love, kindness, generosity, sympathy and empathy alleviates the pain of birth pangs for a new world. At the individual level, flexible framing and the ability to see and consider the complexity of reality reduce the risks of unethical behaviour. Flexible framing is superior to rigid framing, and ‘it makes sense to promote conditions in societies and organizations that foster a climate of tolerance and pluralism instead of fundamentalism and dogmatism’ (Palazzo et al. 2012, p. 335).

We have argued that it is necessary to initiate a transition in the mode of existence and in leadership theory in order to cope with the underlying patterns of the crises, both at a personal level, organizationally and globally. By comparing the different positions in leadership theory with Kierkegaard’s three modes of existence, it becomes clear that a transition towards a spiritual–religious perspective offers a new economic system embodying a new human identity in cooperative partnerships with both culture and nature. The new economic practice goes hand in hand with a transition in both consciousness and leadership theory, a radical shift away from rational, and traditional, self-interest, to a holistic concern.

We have argued that the ironic–reflective interpretation offers a relevant and valid explanation for these processes, in both modes of existence and positions in leadership theory. According to the ironic–reflective interpretation, the process can be described as expanding consciousness both individually (leaders) and collectively (culture).

Central dimensions in these processes are at the ontological level—from a mechanical to an organic worldview. An important implication is the acceptance of organizations as parts of integrated networks. At the epistemological level, instincts and intellect are expanded by intuition, with an increasing focus on relations and wholes. At the ethical level, focus changes from egocentric utility to development of the selfless moral character. One consequence is a massive transition away from economic man to cosmic man. To sum up, leaders with consciousness of the spiritual–religious perspective will focus on Gaia, including networks of all living entities on the Earth, more than on the single organization (Table 1).

The return they seek is not terms of profit, ‘but in advances in education, environmental protection, rural development, poverty alleviation, human rights, healthcare, care for the disabled, care for children at risk, and other fields’ (Bornstein 2007, p. 12). This leads to ‘deeper meaning in their work as well as personal and professional satisfaction, recognition, happiness, peace of mind and the feeling of being whole—of living with harmony with their values, thoughts, words and deeds’ (Pruzan 2008, s. 112). Life’s spiritual dimension and meaning is the context of understanding reality. This anchoring requires a pervasive change in the levels of consciousness in which mechanical solutions are understood from an organic perception of reality and not the inverted form in which organic solutions are interpreted in a mechanical perception of reality. This can only be done by a radical rethink of the way we see the world and by opening up to a new holistic framework for our perceptions. These processes have the potential to reveal solutions to the world’s most urgent challenges, helped along by a pure moral awareness and acts of will.

References

Accessed 23 January, 2014, from http://smallbusiness.chron.com/advantages-disadvantages-profit-maximization-11225.html.

Accessed 23 January, 2014, from http://www.volvogroup.com/group/global/en-gb/responsibility/Pages/responsibility.aspx.

Accessed 23 January, 2014, from http://www.weleda.com/90years/language=en/11201.

Blackburn, S. (2001). Ethics—A very short introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Bornstein, D. (2007). How to change the world: Social entrepreneurs and the power of new ideas. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Carroll, A. B. (1991). The pyramid of corporate social responsibility: Toward the moral management of organizational stakeholders. Business Horizons, 34, 39–48.

Cavanagh, G. F., & Bandsuch, M. R. (2002). Virtue as a benchmark for spirituality in business. Journal of Business Ethics, 38, 109–117.

Cooper, D. E. (1996). World philosophies: An historical introduction. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers.

Copleston, F. S. J. (1985). A history of philosophy (book three). New York: Doubleday.

Eisenstein, C. (2011). Sacred economics: Money, gift and society in the age of transition. Berkeley: Evolver Editions.

Friedman, M. (1970). The social responsibility of business is to increase its profits. The New York Times Magazine, 5, 265–269.

Fry, L. W. (2003). Toward a theory of spiritual leadership. Leadership Quarterly, 14, 693–727.

Fry, L. W., & Cohen, M. P. (2009). Spiritual leadership as a paradigm for organizational transformation and recovery from extended work hours cultures. Journal of Business Ethics, 84, 265–278.

Gardiner, P. (2002). A very short introduction to Kierkegaard. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Gotsis, G., & Kortezi, Z. (2007). Philosophical foundations of workplace spirituality: A critical approach. Journal of Business Ethics, 78, 575–600.

Ingebrigtsen, S., & Jakobsen, O. (2009). Moral development of the economic actor. Ecological Economics, 68, 2777–2784.

Jones, W. T. (1975). A history of western philosophy: Kant and the nineteenth century. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich.

Kenny, A. (1998). A brief history of western philosophy. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers.

Ketola, T. (2008). A holistic corporate responsibility model: Integrating values, discourses and actions. Journal of Business Ethics, 80(3), 419–435.

Kierkegaard, S. (1989). The sickness unto death. Westminster: Penguin Books.

Kierkegaard, S. (2004). Either/Or: A fragment of life. New York: Penguin Books.

Kierkegaard, S. (2012). Fear and trembling. New York: Merchant Books.

Kohlberg, L. (1964). The development of moral character and moral ideology. In M. L. Hoffman & L. W. Hoffman (Eds.), Review of child development research. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Lindner, E. (2012). A dignity economy. Lake Oswego: World Dignity University Press.

McGhee, P., & Grant, P. (2008). Spirituality and ethical behaviour in the workplace: Wishful thinking or authentic reality. Electronic Journal of Business Ethics and Organization Studies, 13(2), 61–69.

McGregor, D. (1960). The human side of enterprise. New York: McGraw-Hill Book Company.

Miller, W. C., & Miller, D. R. (2008). Spirituality: The emerging context for business leadership. Copenhagen: Global Dharma Center.

Mitroff, I. A., & Denton, E. A. (1999). A spiritual audit of corporate America. San Francisco: Pfeiffer.

Næss, A. (1989). Ecology, community and lifestyle. London: Cambridge University Press.

Ouchi, W. (1981). Theory Z—How American business can meet the Japanese challenge. New York: Avon Books.

Palazzo, G., Krings, F., & Hoffrage, U. (2012). Ethical blindness. Journal of Business Ethics, 109, 323–338.

Palazzo, G., & Scherer, A. G. (2006). Corporate legitimacy as deliberation: A communicative framework. Journal of Business Ethics, 66, 71–88.

Popper, K. (2002). The logic of scientific discovery. London: Routledge.

Pruzan, P. (2008). Spiritual-based leadership in business. Journal of Human Values, 14(2), 101–114.

Pruzan, P. (2012). The source of ethical competency; eastern perspectives provided by a westerner. Paper presented at the Tabec conference “Business and the greater good: Regaining trust, humanity and purpose in the age of crisis”, NHH, Bergen.

Pruzan, P., & Pruzan Mikkelsen, K. (2007). Leading with wisdom: Spiritual-based leadership in business. Sheffield: Greenleaf Publishing.

Renouard, C. (2011). Corporate social responsibility and the capabilities approach. Journal of Business Ethics, 98, 85–97.

Savory, A., & Butterfield, J. (1999). Holistic management: A new framework for decision making. Washington: Island Press.

Sheldrake, R. (2009). Morphic resonance—The nature of formative causation. Rochester: Park Street Press.

Skirbekk, G., & Gilje, N. (2001). A history of western thought: From ancient Greece to the twentieth century. London: Routledge.

Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. (2012). Virtue ethics. Accessed August 27, 2013, from http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/ethics-virtue/.

Steiner, R. (1995). Intuitive thinking as a spiritual path. Hudson: Anthroposophic press.

Sternberg, R. J. (2005). The nature of creativity. Creativity Research Journal, 18(1), 87–98.

Sternberg, R. J. (2006). The theory of successful intelligence. Interamerican Journal of Psychology, 39(2), 189–202.

Storsletten, V. M. L., & Jakobsen, O. D. (2013). Revolution and evolution in economics, business management and leadership theory. In A. Midttun (Ed.), CSR and beyond—A nordic perspective (pp. 364–386). Oslo: Cappelen Damm Akademisk.

Taylor, F. W. (2011). The principles of scientific management. New York: Harper & Brothers.

Wheatley, M. J. (2006). Leadership and the new science: Discovering order in a chaotic world (3rd ed.). San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler Publishers.

Whitehead, A. N. (1967). Science and the modern world. New York: The Free Press.

Zsolnai, L. (2004). The moral economic man. In L. Zsolnai (Ed.), Ethics in the economy: Handbook of business ethics (pp. 39–58). Oxford: Peter Lang Academic.

Zsolnai, L. (2008). Buddhist economic strategy. In L. Bouckaert, H. Opdebeeck, & L. Zsolnai (Eds.), Frugality: Rebalancing material and spiritual values in economic life (pp. 279–303). Oxford: Peter Lang Academic.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License which permits any use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and the source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Storsletten, V.M.L., Jakobsen, O.D. Development of Leadership Theory in the Perspective of Kierkegaard’s Philosophy. J Bus Ethics 128, 337–349 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-014-2106-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-014-2106-y