Abstract

In recent years, researchers have observed the process of mainstreaming Fair Trade and the emergence of alternative sustainability standards in the coffee industry. The underlying market dynamics that have contributed to these developments are, however, under-researched. Insight into these dynamics is important to understand how markets can develop to favor sustainability. This study examines the major developments in the market for certified coffee in the Netherlands. It finds that, in the creation of a market for sustainable coffee, decisions that significantly influence market creation are made in the lead companies (retailers and coffee roasters). These decisions are made possible by the availability of multiple systems of sustainability standards and by the existence of a small segment of loyal Fair Trade customers that ensured that sustainability remained an issue on the coffee market in the years before the market creation took-off. Fair Trade did not become the new rule in this process, but it became the benchmark against which companies could compare themselves and the basis upon which they built in adopting or developing new standards that would be more feasible in their business models.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The coffee market has undergone many changes in recent decades with respect to sustainability (e.g., Kolk 2005). This case study describes how the market for sustainable coffee in the Netherlands developed from a market share of <1% in the mid-1980s to 45% in 2010, with a share of 75% projected by 2015. In this study, “sustainable” is defined as compliance with standards for the social and environmental aspects of production and trade. The establishment of standards is an increasingly important instrument to improve environmental and social sustainability in supply chains that originate from developing countries (e.g., Barrientos et al. 2003; Giovannucci and Ponte 2005; World Bank 2002). With approximately 20 different systems of sustainability standards, including Rainforest Alliance, Starbucks, and Utz Certified, the coffee industry is, in this respect, a forerunner (Kolk 2005).

Previous research on standards has examined the ethical content of standards and the degree to which market actors comply with them (e.g., Healy and Iles 2002; Kolk and Van Tulder 2002). The multi-stakeholder process in which standards are formulated has also been analyzed (Ingenbleek et al. 2007; Ingenbleek and Immink 2010), but the market process in which companies decide to adopt standards and thereby create a market for sustainable products has not been studied. This study is the first to describe this process, from the introduction of a Fair Trade product, Max Havelaar coffee, to the subsequent creation of a market for sustainable products. Although Max Havelaar coffee was the first Fair Trade product introduced in the mainstream supermarket channel anywhere in the world, the process of its introduction and its subsequent role in competition with other standards has not yet been extensively reported in the academic literature.

A detailed description of this case is important to better understand the role of Fair Trade. Mainstreaming is regarded by an increasing number of scholars as one of the most significant developments of the Fair Trade movement (Moore 2004; Hira and Ferrie 2006). Researchers have described the changes in the Fair Trade organization (Moore 2004; Gendron et al. 2009; Özçağlar-Toulouse et al. 2009; Davies 2008), the role of commercial companies that adopt the Fair Trade certification system (Fridell 2008; Raynolds 2009; Reed 2008), and the role of specific Fair Trade brands that have contributed to the growth of Fair Trade products in mainstream distribution channels (Davies et al. 2010; Randall 2005). Less attention has been devoted to the role of Fair Trade in the dynamic market processes, including the emergence of alternative sustainability standards, which underlie the mainstreaming of sustainability standards.

This case study is relevant for managers in other industries because it may help them to understand the development of multiple standard systems in their industries. The existence of multiple standards systems may involve strategic, as well as ethical, decisions about which standard-formulating organization to join. In addition, this study is relevant for public policy-makers who aim to implement sustainability practices by encouraging market actors to adopt sustainability standards. A deeper understanding of what caused the creation of a market for sustainable coffee may lead to a more effective deployment of policy instruments, such as the regulation of sustainability labels.

This study is structured as follows. We first briefly describe the background of sustainability standards, including Fair Trade, in international supply chains. Next, we describe the chronological development of a market for certified coffee in the Netherlands. This description ends with our conclusions and discussion of implications. For a description of the research method, please see “Appendix 1”. “Appendix 2” contains materials that may facilitate classroom discussion of the study.

Background on Sustainability Standards and Fair Trade

Companies increasingly attach sustainability standards to their criteria for safety and quality (Waddock and Bodwell 2004). These standards may include any type of responsible behavior, such as the way the company deals with natural resources (e.g., forests in timber production), waste materials, labor conditions, or social arrangements (e.g., maternity leave for employees). All these sustainability standards have different set ups and incentive structures and can be used in consumer and business-to-business markets. In consumer markets, they are communicated as a label (for example, the Fair Trade label). To primary producers and intermediary traders in international supply chains, standards are rules that they may voluntarily comply with. By complying with the standards, producers and traders receive licenses to sell, either a formal certificate or a designation of “preferred supplier” (Drumwright 1994; Ingenbleek et al., 2007; Maignan and McAlister 2003), because, by complying with the standards, they transfer the positive traits of the standards to the customer company.

If the customer company is the only one (or perhaps one of the few) that offers sustainable products to the consumer, this is likely to contribute to its Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) reputation. The CSR reputation may in-turn contribute to a better evaluation of the products of that company (Brown and Dacin 1997; Sen and Bhattacharya 2001). However, when more companies adopt standards, the differential advantage of the standards may decrease and consumers may perceive the adoption of standards as a requirement for a legitimate business. In other words, rather than setting the company apart in terms of CSR, the standards show that the company operates within the norms of what is deemed appropriate in society (cf. Grewal and Dharwadkar 2002).

According to institutional theory, sustainability standards are therefore institutions; they emerge from social pressures to restore or improve the legitimacy of a company’s activities. In other words, under social pressure from special-interest groups and/or media, companies may voluntarily comply with standards to restore or maintain their legitimacy. Specifically, the formulation of sustainability standards is the so-called authorization process that “involves the development of rules or codes of conduct that are deemed appropriate and require channel members to seek voluntarily the approval of authorization agents” (Grewal and Dharwadkar 2002, pp. 86–87). The organizations that develop these standards are called standard-formulating organizations (Ingenbleek and Immink 2010).

The first standards for international supply chains were likely developed by the Fair Trade movement itself. Moore (2004, p. 74) and Redfern and Snedker (2002, p. 11) describe the following goals of Fair Trade: “(1) To improve the livelihoods and well-being of producers by improving market access, strengthening producer organizations, paying a better price and providing continuity in the trading relationship. (2) To promote development opportunities for disadvantaged producers, especially women and indigenous people, and to protect children from exploitation in the production process. (3) To raise awareness among consumers of the negative effects on producers of international trade so that they exercise their purchasing power positively. (4) To set an example of partnership in trade through dialogue, transparency and respect. (5) To campaign for changes in the rules and practice of conventional international trade. (6) To protect human rights by promoting social justice, sound environmental practices and economic security.”

The Fair Trade movement emerged in the middle of the twentieth century from a general dissatisfaction with the functioning of the capitalist system, which was accused of being unfair to small-scale producers in developing countries (Witkowski 2008). To connect consumers in high-income countries directly with producer groups in low-income countries, the Fair Trade movement developed a network of World Shops which sold handicrafts and, later, food products such as coffee, tea, and sugar (Gendron et al. 2009). In these small-scale initiatives, there were direct contacts between the charity groups that ran the stores or organized the supply on their behalf and the producer groups in developing countries. Consumers paid price premiums for the products, and the earnings of the stores were sent to missionaries or cooperatives to improve the living standards of producers. There was no need for formal standards at that time; these would emerge later when the movement became professionalized and institutionalized and increasingly started to penetrate mainstream distribution channels. These developments will not be described here in detail, as they are well described in other studies (e.g., Moore 2004; Gendron et al. 2009; Hira and Ferrie 2006).

Davies (2008) as well as Davies and colleagues (2010) recognize three phases in the development of the Fair Trade movement. A solidarity era prior to 1990 during which the first contacts were established between producer organizations in developing countries and ethically driven entrepreneurs in the North was followed by a phase from 1990 to 2002 in which Fair Trade tried to compete on the open market with products of better quality than those sold during the solidarity era. Finally, the mass market era (from 2002 onwards) is characterized by brand alliances and differentiation of Fair Trade products at different price-quality levels. Our case description roughly follows the latter two phases of development and will show that Fair Trade was joined by rival standard-formulating organizations in the second and third phases. It will also highlight the dynamics among these organizations in the institutional environment in relation to brand competition in the market environment. Figure 1 summarizes our findings in a timeline depicting the major developments and events in the Dutch market for coffee, while Table 1 provides an overview of the different sustainability standards and their logos that are discussed in this study.

The Dutch Coffee Market in the Solidarity Era (Before 1988)

Before the emergence of retailers’ private coffee brands, coffee roasters were the sole lead companies in the Dutch coffee chain. During the 1980s, they had either a national or, at best, a European orientation. Coffee roasters source their coffee beans from tropical countries in Latin America, Asia, and Africa. Although there are several varieties of coffee beans (such as Arabica and Robusta), coffee beans are traded as commodities at institutions like the New York Board of Trade. The market functions, therefore, much like an anonymous spot market in which market prices for coffee beans fluctuate with changes in supply and demand. Between the coffee roasters and the primary producers, a multitude of traders and transporters may be involved; these include importing companies, exporting companies, national marketing boards, and transporters/traders who purchase coffee beans from individual primary producers or cooperatives.

In the 1980s, the Dutch coffee market consisted of two major channels. First, the larger coffee roasters served the supermarket channel, where consumers bought their coffee for home use. Second, many Dutch consumers drank their coffee away from home, either at work or at bars and restaurants. The vending machines at work places and offices were generally supplied by the large coffee roasters, whereas three or four smaller coffee roasters focused on bars and restaurants by producing specialized coffee of refined quality. In the 1980s, the supermarket channel was dominated by three brands, of which Douwe Egberts (DE) was most prominent. DE was a typical traditional Dutch brand, and the Dutch were very familiar with its typical flavor, which was created by combining different types of beans. It was often said that “DE taught the Dutch how to drink coffee.” By promoting coffee drinking as a social event shared with family and friends, the DE brand had become a part of Dutch culture. As market leader, DE also had the strongest voice in the industry organization of Dutch coffee roasters.

In the mid-1980s, coffee became the subject of a political controversy that created an uproar in the Netherlands. In several Latin American countries, such as El Salvador and Nicaragua, left-wing governments had come to power. Following the rationales of the Cold War, coffee farmers in these countries were excluded from the world market for political reasons. Activist groups blamed the coffee industry and developed plans to break the power of the dominant firms in the coffee chain. These groups created an atmosphere conducive to new ideas intended to dramatically reorganize economic systems. The Fair Trade movement, for example, experienced an increase of sales of “alternative” products in churches and World Shops during these years. One of these products was coffee, made with coffee beans from El Salvador. One respondent explained how this coffee served primarily as a political statement rather than a beverage: “The taste was considered unimportant relative to the political message, and it therefore tasted terrible.” The market share of this product was negligible on the Dutch coffee market. However, it was in this environment that the idea for Fair Trade coffee in the mainstream supermarket channel emerged.

In 1986, Nico Roozen, a new employee of the Dutch Catholic development organization Solidaridad, which was active in the Fair Trade movement, visited Latin America. He spent considerable time with missionary Frans van der Hoff at Uchiri, a cooperative of coffee farmers in Mexico. This trip provided Roozen significant insight into how the coffee market functioned from the perspective of primary producers. Roozen witnessed the social consequences of the system for the coffee farmers, who claimed that, instead of development aid, they preferred a fair price for their products. Roozen and Van der Hoff decided to collaborate: Van der Hoff would organize the supply chain in Mexico, and Roozen would organize the demand among roasters and supermarkets for Max Havelaar coffee in the Netherlands. Thus, the plan to put a Fair Trade product in a marketing channel was born.

The goal was to develop a label for the coffee that could be used by existing brands as an extension of their product line. At the time, the name Fair Trade was not yet well established, so the label used the name Max Havelaar. This name was derived from the main character of a famous nineteenth century novel that described the injustices of the Dutch colonial system in the coffee-growing areas of Indonesia. Consumers would pay a premium price for the labeled coffee, while producers would be paid a minimum price that covered the costs for development of their livelihoods.

Back in the Netherlands, Roozen realized that he needed an alliance with an established company in the coffee industry, and he therefore decided to visit all the major players in the industry. Before he could do so, however, he first had to convince people in his own organization that “talking to the enemy” was really necessary. The second problem that he encountered was whom to contact at the coffee companies. CSR was not well established in this industry at the time. Most companies considered their relationships with alternative trade movements to be in the category of “damage control,” which was the responsibility of a public relations manager. In most companies, however, decision-making authority lay with the CEO of the company. It took Roozen almost 3 years to make contact with all the companies on his list.

The End of the Solidarity Era: The Introduction of Max Havelaar (1988–1990)

As the Netherlands was the first country and the coffee industry was the first industry where a mainstream Fair Trade product was being launched, the initiative was fundamentally new: company managers within the industry had no reference points from other industries or countries. Although coffee roasters had become aware of the problems in the coffee-growing countries, these companies had regarded those problems as inevitable in a market economy. Low prices were explained as resulting from overproduction. If injustice was done to coffee producers, the companies considered remedies to be the responsibility of local governments, not of the industry. The latter was considered only responsible for producing coffee for consumers and profits for its shareholders. “Coffee and politics shouldn’t mix” was the general opinion in the industry, as expressed by one respondent.

Roozen was taken seriously by the coffee roasters: his idea was perceived as a serious threat to the coffee business as it had long been operated by the existing companies. At market leader DE, Roozen had six or seven subsequent meetings about his ideas. DE was, however, no longer the family business that it had been for decades. In 1984, the company was sold to multinational Sara Lee. This takeover led to a change in strategic direction. Plans to expand the brand internationally were abandoned, and the company, with its dominant domestic market position, was added to its new owner’s portfolio as a “cash cow.” This change in strategy was accompanied by a change of CEO at DE. The new CEO was described by one of his employees as a “calculator” and a “typical rationally-thinking manager,” a description that fit the company’s new strategy.

The new strategy at DE would have a strong impact on how the company would respond to the Max Havelaar initiative. To estimate the potential market share of the Max Havelaar coffee, both Solidaridad and DE conducted market surveys. As Roozen said

At that moment, I was really convinced that we would conquer a 7 to 15% market share. That was not wishful thinking, but those were predictions on the basis of market research. This result was consistent from both our own studies and the ones from DE that leaked and that we laid our hands on. All studies told us that 7 to 15% of the Dutch consumers would be willing to pay a little bit more for fair coffee than for regular coffee.

Based on these predictions, market leader DE took a well-supported and strategic position. According to Roozen, the CEO of DE once told him: “I allow you 5 percent maximum; otherwise, I will sweep you off the market, or I will join you.” It seemed likely that, if Max Havelaar did reach a market share of at least 5%, it would be more profitable for DE to join the initiative. Solidaridad was, therefore, eager to achieve a 5% market share because it would give them bargaining power. Getting the market leader on board would give the market for Fair Trade coffee an enormous boost.

However, DE’s first option was to prevent the Max Havelaar label from coming to the market in the first place, and indeed, it made great efforts to prevent a market entry. DE used its power in the organization of Dutch coffee roasters to convince coffee roasters not to join the initiative. At his visits to those companies, Roozen was told simply that they would not roast the certified coffee beans and bring them to the market. This made it completely impossible to enter the market with certified coffee. Therefore, Roozen tried to circumvent DE’s power by dealing directly with retailers. Initially, the new approach seemed successful

At some point, we had Albert Heijn (AH) supermarkets [the leading retailer in the Netherlands] on our side. They had agreed to develop a label with us and to sell the labeled coffee in their stores. This decision was called back by the president of the company. I was told by my contact person at AH that the president received a phone call from the president of DE. After that, he had decided to cancel all contacts with Solidaridad.

Another informant confirmed that the market entry was essentially blocked by the domination of DE and AH in the market. At this point, Solidaridad was left empty-handed, and DE’s strategy seemed to have been effective.

Just as Solidaridad was about to conclude that entering the market with Max Havelaar coffee was not possible, an unexpected breakthrough occurred; one of the smaller roasters, Neuteboom, suddenly offered to produce the Max Havelaar coffee. This company had been active on the retail market for several decades but had been squeezed out of the market for home use coffee by the A-brands. Relying on the out-of-home consumption market alone was an undesirable position for the company because it operated under capacity. The company urgently needed an opportunity to fill its capacity; otherwise, it would eventually go bankrupt. When the major brands in the retail channel were not willing to join with Solidaridad, Max Havelaar suddenly offered Neuteboom an opportunity to fill its capacity. Neuteboom could, however, count on the efforts of DE to stop them, as Roozen described

Right at the moment when I was there to sign the contract, he received a phone call from the president of DE personally, telling him that he would regret his decision to produce Max Havelaar. I left him for a moment, because I would understand it if he backed off at that moment. He quickly followed me, however, telling me that if DE was afraid of it, that it must be interesting enough to step in.

According to Jan-Willem Top, managing director at Neuteboom, the company did not regard the market power of DE as a major risk to their business at that time. Rather, the main risk for Neuteboom was associated with the supply chain: “There was, of course, a risk; you did not know where the coffee came from. One of the first things after we signed the contract was that someone visited one of the producer’s countries, to see the farmers.” When Neuteboom began working with Max Havelaar, Norbert Douqué (of the family-owned coffee trading company Douqué) was called into organize the supply from Mexico, operating as a separate business unit named Van Weely.

Initially, the initiative indeed seemed to produce what Neuteboom wanted: a return to the supermarket channel with its own brand, albeit this time with a Max Havelaar label attached. Although AH supermarkets had initially stepped away from the initiative, they seemed to change their minds when Neuteboom agreed to produce the coffee. AH placed a large order for Max Havelaar coffee with the roasting company. The contracts were, however, not iron-clad: when the roaster had made the necessary investments, the order was suddenly canceled for no clear reason. This seemed to be the final blow for the coffee roaster, which was already in bad financial straits. Nevertheless, this event led to a remarkable outcome: an investment (development funding from a charity) from Solidaridad was used to save the company from bankruptcy.

This appeared to be the final hurdle to the introduction of Max Havelaar coffee. The product was introduced in several supermarket channels in 1988. AH supermarkets followed 4 months later, after receiving bad press and complaints from concerned consumers.

The New Competitor is Ignored (1990–1996)

It was clear within a month. We saw it happening immediately, that we would be stuck at 2% market share, 3% at best. I was convinced that power would be with the consumers, but it turned out otherwise. Even taking into account the socially-desirable responses in the market research, consumers are agenda-setting to a very small extent, a very small push factor. The market is made by the choices that producers and retailers make. Consumers are much more loyal to brands than we expected.

Thus, Roozen reflected on the introduction of Max Havelaar. When it became clear that the market share of Max Havelaar would not grow beyond 3%, there was no serious incentive for DE to join the initiative. According to Roozen, “they could finally ignore us, and they did so for ten years, because Max Havelaar didn’t grow further.” Additionally, a CSR initiative targeted at coffee farmers, which had been announced by the organization of Dutch coffee roasters (most likely an attempt to safeguard its reputation) shortly before the introduction of Max Havelaar, was cancelled. According to Norbert Douqué, “what has been killing for Max Havelaar was that there was no roaster who was prepared to stick his neck out to take responsibility for the marketing. When there are so many different small roasters, no one is willing to advertise, because then they would advertise for each other.”

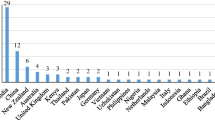

With no party willing or able to make substantial marketing investments in Max Havelaar, the market remained relatively stable over the next several years. The market share of Max Havelaar did not grow beyond 3%, as is seen in Fig. 2. Instead of devoting all its efforts to increasing the market share in the Netherlands, the Fair Trade movement focused during those years on internationalization of the Max Havelaar certification concept and on diversification into bananas and, subsequently, other tropical fruits. DE established a charitable foundation in 2002 that financed small development projects with coffee farmers, but this effort never became part of its core processes. According to a respondent, the DE president once said that “we have given it a place now. It is no threat to us; it sticks to 2% of the market, so we can ignore it.”

Under cover of this stable market, several important market trends took place. First, a trend of increasing concentration took place in the coffee industry. The largest brand (DE) eventually acquired most of its competitors, leading to a market share of approximately 70%. With the removal of European trading barriers during the 1990s, there was also a trend of increased internationalization. Foreign players such as Nestlé became more prominent in the Dutch coffee market. Sara Lee began to strengthen its grip on its daughter company, DE. A third trend was the increasing market share of store brands (private labels) and a growing concentration of coffee roasters that focused on store brand manufacturing. According to an expert respondent, the store brands’ market share grew with 7% at the expense of the A-brands. Of the two or three companies in this segment, the most prominent was the Ahold Coffee Company (ACC), which sourced, branded, and packaged coffee for the Ahold supermarkets in Europe and the US. Finally, during the 1990 s, a trend toward higher product quality and finer taste emerged. This trend resulted in the entry of a few smaller brands (predominantly foreign, for example, Italian) that focused on the high quality-high price market, often selling through specialty stores that began to emerge at that time.

At the producer level, a worldwide coffee production crisis emerged during the 1990s. During the 1970s and 1980s, prices were well above 100 US cents/lb., but they declined during the 1990s, reaching a low of 41.17 US cents/lb. in September 2001 (whereas a Max Havelaar farmer received 120 US cents/lb. at that time). Coffee prices remained low until 2004. There are various reasons for the steady price decrease. First, the International Coffee Agreement, which had ensured a minimum price for coffee since 1974, was abandoned in 1989 when there was no longer pressure from communist countries to maintain it. Second, production of coffee beans had increased with the expansion of coffee production in Brazil and the market entry of Vietnam following the end of the US trade embargo in 1994 (Vietnam rapidly became the world’s second largest coffee producer after Brazil). Third, some argue that concentration in the international roaster market (resulting in four large multinational roasting companies: Procter & Gamble, Nestlé, Kraft, and Sara Lee) led to a stronger focus on efficient sourcing.

Due to the crisis in coffee production, the role of the large multinational roasting companies received more attention, as their policies became more clearly linked to growing poverty among coffee farmers. As a result, the large coffee companies started to experience significant social pressure (Kolk 2005). NGOs conducted campaigns and actions were held. For example, according to the sustainability manager of Douwe Egberts

When we celebrated our 250th anniversary in 2003 and coffee prices had reached their minimum, posters were hung with texts like DE celebrates, but for most of the coffee farmers it’s no party at all!

In response, CSR became more prominent within these companies. According to one respondent, there emerged a new generation of managers who had received training in CSR during their management education. For example, although the growing influence of Sara Lee on DE had initially brought about more efficiency-oriented management, a respondent working at DE reported that CSR subsequently became a higher priority, as US companies were also being held more accountable in their home country for externalities in the coffee trade.

Mainstreaming Beyond Fair Trade: The Emergence of Utz Kapeh (1996–2000)

These developments during the 1990s set the stage for the first real follow-up to Max Havelaar in the Dutch coffee market. In 1997, the ACC began to develop Utz Kapeh (which can be translated from the Mayan language as “Good Coffee”). ACC was the private label coffee roaster for Ahold, which sourced not only the AH supermarkets but also the other Ahold supermarket formulas in Western Europe and the US. As a result, Utz Kapeh has experienced significant growth since the end of the 1990 s (the second largest Dutch supermarket C1000 followed by adopting Utz Kapeh, for example, in 2005). A strong driving force behind the development of Utz Kapeh was Ward de Groote, managing director of ACC, who had lived in Latin America for several years and witnessed the impact of the coffee crisis on farmers

When I visited the origins of our supply chain, I saw myself what had to be changed […] I had a passion to help these farmers in the Third World […] We did not see Fair Trade as a good solution because it was based on positive discrimination, only small farmers were allowed to participate in Fair Trade, and because the certification system works with a minimum price. Such a minimum price partly removes the incentives for farmers to look for operational efficiency and new technologies and this undermines the position of the farmers in the long run.

The standards of Utz Kapeh are, therefore, different from those of Fair Trade. In fact, development of the Utz Kapeh standards was used as an opportunity to improve upon the Fair Trade standards. One expert, therefore, expressed the expectation that “the model of Utz will eventually have more impact in the long term than the Max Havelaar model.”

Utz Kapeh establishes environmental and social requirements, as well as cost-saving and quality-enhancing standards, within the coffee chain. On each issue of the certification scheme, producers receive a certain score. In order to increase sustainability, the minimum required score is increased over time. Compared to Fair Trade’s in-or-out standard on mainly social issues, the more complex system of Utz Kapeh is considered necessary to cover the many different social and natural environments involved. Another important difference between Max Havelaar and Utz Kapeh is that Max Havelaar focuses on the consumer, who is paying the price for the product’s social and environmental costs. Utz Kapeh, on the other hand, requires retailers and coffee roasters to internalize these additional costs. As a result, one respondent argued that Utz is a “CSR concept,” whereas Fair Trade is “a consumer label.” Although Utz allows coffee roasters and retailers to use the label “Utz Certified,” the Utz strategy regards the company, rather than the consumer, as the most important actor.

As already mentioned, another key difference is that Utz does not pay primary producers a guaranteed minimum price; rather, it helps them to be more efficient and to produce higher quality coffee that generates a higher market price. With this approach, long-term relationships between roasters and producers should provide producers more stability than a spot market can. As the former Utz Kapeh manager David Rosenberg has argued

It is an integral project in which we offer tools to participating coffee farmers to improve their business processes. This pays off because, if a coffee farmer implements a solid management system, he will run his business more efficiently. Subsequently, we reward that, following the rationale: I asked you for a better product, and I am also willing to pay more for it. That’s a big difference from Fair Trade coffee. If you start talking about a higher price right away, that’s the wrong way. Price is only one part of the entire process. We target the large brands, the mainstream market. The scale advantages keep prices low. Our approach is commercial and competitive.

Remarkably, Solidaridad, the founding organization of Max Havelaar, began to support Utz Kapeh financially in 1999. According to Roozen

I found out that you can’t turn Max Havelaar into a mainstream system. DE would never accept that. For its core product, a system should be implemented for which price setting is not free because of a minimum price guarantee. In a competitive market, this would be impossible for such a company. They would be competed out of the market during times of price crises.

Although both organizations shared the objective of reducing poverty among coffee growers, competitive tensions emerged between Max Havelaar and Utz Kapeh. A Max Havelaar employee discussed the issue: “we are very similar to each other because Utz Kapeh also has the objective of mainstreaming sustainable coffee. There is, of course, already Max Havelaar coffee, so there are a lot of tensions.” According to Ward de Groote, a Max Havelaar representative told him that PR and communication were the domains of Max Havelaar, so he was not allowed to seek media attention for Utz: “The reaction of Max Havelaar was fierce, because they thought that they had the press behind them.” Douqué argued that the introduction of Utz helped Max Havelaar to position itself as a quality brand. Thus, behind the market competition between coffee brands, rivalry emerged as well between the standard-formulating organizations in the institutional environment.

Who is the Fairest of Them All? (2000–2006)

Utz Kapeh was adopted by the two leading supermarket chains in the Netherlands to strengthen the CSR image of their store brands, thus making coffee a central product in their CSR policies. As a result, the third supermarket formula on the market (Super de Boer) also felt pressure to strengthen its quality image with an ambitious CSR strategy. It, therefore, needed a certification system for its private label coffee. Instead of adopting Utz Kapeh, however, it turned to Rainforest Alliance (and was sourcing 30% of its private label coffee from Rainforest Alliance in 2006). The Rainforest Alliance was established in the late 1980 s with the objective of halting deforestation by providing specific solutions to the problem, rather than merely increasing public awareness. In 1989, it launched the forestry certification system Smartwood, and in 1991, introduced the Rainforest Alliance label for bananas. In the 2000s, Rainforest Alliance also launched a certification system for coffee. Growers are certified on the basis of several standards: conserving local wildlife and water resources, protecting forests (including reforestation where possible), minimizing soil erosion, and treating workers fairly. Comparable to Utz, the Rainforest Alliance system offers growers the tools to lift themselves out of poverty and open their markets to more profitable premium products.

One respondent suggested that Super de Boer selected Rainforest Alliance (even though it is based in New York), because Utz was already strongly identified with other brands; Super de Boer preferred a different label to support its differentiation strategy. Super de Boer sources its coffee from private label roaster De Drie Mollen, which also supplies Rainforest Alliance coffee to the British market. In addition to Rainforest Alliance, this roaster also offers Fair Trade and Utz Kapeh, so it can proudly claim to offer its customers all three certification systems in the coffee industry.

One point of criticism leveled at Rainforest Alliance is that they allow the use of their label on coffee containing a minimum of 30% certified coffee beans. According to a respondent from Drie Mollen

Rainforest Alliance started with 30% certified coffee beans, because they wanted to slowly build their market. When you start with 100% certified coffee, you have the same problem as Max Havelaar: this would be too expensive, and companies would not do business with you.

Interestingly, for consumers, the involvement of lead companies and the feasibility of organizing a certified supply for them weighed more heavily than the desire for 100% certified products. In 2006, other retailers (Superunie, Koopconsult) sourced at least 10% of their private label coffee from certified sources.

The Market Leaders Follow

In an environment in which coffee brands continuously developed new plans for certification, it is hard to imagine that market leader DE would not take measures to improve the ethical dimension of its brand, especially when DE’s mother company, Sara Lee, became more actively involved in providing certified coffee. Sara Lee began offering Transfair coffee (the US-based Fair Trade coffee) on the institutional market in the US after McDonald’s explicitly requested the coffee for its restaurants. Moreover, according to a DE employee, a new CEO at DE brought about a wave of change to the inward-looking corporate culture of the company. Finally, as already mentioned, when the brand celebrated its 250th anniversary in 2003, it became the target of a pressure campaign by NGOs.

In 2004, DE responded to this pressure and announced that it would begin obtaining 4.5% of its coffee beans from sources certified by Utz Kapeh. Currently, approximately 33% of DE’s coffee on the Dutch market can be labeled as sustainable (Oxfam Novib 2010). DE’s ambition is to offer 100% certified coffee by 2017. According to a respondent from DE, “the main trigger for our company to source sustainable coffee was increased demand from large out-of-home customers such as companies and ministries. These customers started to adopt CSR in their policies, which was also translated in the coffee that they wanted to offer to their employees.” DE’s adoption of Utz was, indeed, a true competitive move to strengthen its position on the institutional market (i.e., offices, schools, and canteens). In 2007, DE sued the Dutch province of Groningen for explicitly requiring its coffee suppliers to meet Fair Trade criteria; DE believed that this requirement excluded its own Utz Certified coffee from the market. After several months, the provincial authorities won the case. Coen de Ruiter, director of the Max Havelaar Foundation, commented on the case

It provides governmental institutions the freedom in their purchasing policy to require suppliers to provide coffee that bears the Fairtrade/Max Havelaar criteria, so that a substantial and meaningful contribution is made in the fight against poverty through the daily cup of coffee.

DE may have lost a battle but has not yet lost the war. In fact, as this study was being written, the Dutch government was developing new criteria for its sustainable purchasing policy that will apply to all governmental bodies and offices. The latest information is that the Dutch government will allow different certification systems, such as Fair trade/Max Havelaar and Utz Certified. In the meantime, DE has decided to add Fairtrade-certified coffee to their product line. As of January 2011, Fairtrade-certified coffee is offered to the out-of-home market.

Completing the Pyramid of Change

In 2007, 4C (Common Code for the Coffee Community) emerged as another player in the arena of sustainable coffee standards. Initiated by the German ministry of development, 4C is “a floor initiative” that was adopted by all large coffee roasters and NGOs in the world. The participants aim to improve the sustainability of the entire sector by setting minimum standards for the economic, ecological, and social aspects of coffee production. This code went into effect in 2007. As one respondent described it,

The Common Code for the Coffee Community is a round-table process for all parties: all large roasters, production countries, and traders. Here, they try to define some sort of minimum standard that works as a license to operate in the sector. You can’t bring coffee to the market if you haven’t organized a few basic things.

Sustainability has become widely accepted in the international coffee industry and actively used by companies to strengthen their market position: Starbucks launched its criteria for sourcing sustainable coffee in 1999; Holiday Inn hotels and KLM began offering Rainbow Alliance coffee; Ikea began serving Utz in its restaurants around the world; Kraft offered a sustainable brand with Rainbow Alliance coffee; Nestlé began to offer a Fair Trade product (questioning, in a press release, why other companies did not adopt Fair Trade and instead chose “second best” standards systems). In 2007, ACC, together with Solidaridad, introduced “Café Oké,” a line of Fair Trade brand coffee products with the Max Havelaar label. According to a respondent from Drie Mollen,

Sustainability is now embedded within the industry and society. […] External circumstances are changing; customers are asking for certified coffee. First, you had to convince your customers several times before they wanted to buy your sustainable coffee; now they are demanding it. That’s the difference.

Roozen believes that sustainability standards can be described as a pyramid, with on-the-floor initiatives that set basic rules, such as 4C, on the bottom; CSR initiatives like Utz and Rainforest Alliance in the middle; and consumer labels like Fairtrade/Max Havelaar at the top (Fig. 3). Sustainable development requires initiatives at all three levels, according to Roozen

This is what I call the pyramid of change. In the sector, you try to create dynamics where consumers can express their preferences. Mainstream companies can take responsibility for a mainstream product. This will be done predominantly by the A-brands. Whether a company is able to internalize the higher costs for sustainability depends on the positioning of the brand. At Fair Trade, you let the consumer pay; about 3% of the market does that. With a CSR concept, you should stick closer to the market; otherwise, they can’t afford it, and then the mechanism won’t work. At the same time, you should ensure that there are no free riders at the bottom, no players that can ignore the entire sustainability agenda.

According to a report by Oxfam Novib, in 2010, 45% of all coffee consumed by Dutch consumers was certified (Oxfam Novib 2010). Furthermore, on November 9, 2010, the Dutch Coffee and Tea Branch signed a Memorandum of Understanding, declaring their intent that, by 2015, 75% of all coffee consumed and sold on the Dutch market should be certified. This memorandum was supported by the Dutch Ministry of Economic Affairs, Agriculture and Innovation, as well as by supermarkets and NGOs.

Discussion and Conclusion

Looking back on the introduction of Max Havelaar and subsequent events on the Dutch coffee market, we can conclude that, over the course of 20 years, a market for sustainable coffee has been created. Sustainability standards have clearly become a critical success factor in the industry. The driving forces behind the creation of this market were the competition between brands on the market and the rivalry of multiple standards systems, or at least the existence of multiple systems, in the institutional environment. The first important step in the process was the introduction of Max Havelaar. This brought a new competitive dimension to the coffee market on which coffee brands could potentially position themselves. As a second step, the introduction of Utz Kapeh started a process that would eventually affect nearly every brand in the market. Suddenly, brand competition on the coffee market was no longer a force that worked against sustainability, as it had in the greater part of the 1990 s, 1980 s, and earlier; it had now become a force that stimulated sustainability.

Remarkably, the key decisions leading to the creation of a market for sustainable coffee were made in the executive offices of lead companies, such as brand-owners and retailers, as well as in standard-formulating organizations and/or by social entrepreneurs who initiated new standards. Consumers expressed their support for these decisions but were not the main factors determining the course of events, in part because, as one respondent formulated it, “consumers could not make the distinction between the different standards schemes, because they don’t know the underlying differences.” Nevertheless, consumers played an important role in that the market would not have taken off, without the presence of a small segment of highly involved and loyal Max Havelaar buyers. These consumers ensure that sustainability remained an issue on the coffee market for the years in which none of the big players in the market responded to the issues. They, therefore, contributed to the continuing awareness of the great majority of the consumers that companies could do something to solve sustainability problems in coffee-growing countries. This in turn created a basis for companies to differentiate their brands. Once the first brands had taken their positions, the issue changed from a matter of differentiation into a matter of legitimacy. The more aware consumers became, the more effective became the campaigns of NGOs targeted at companies that had not yet adopted standards. The sustainability issue, therefore, changed from a form of added-value to a necessary requirement for legitimacy. By pointing companies at their legitimacy, the NGOs therefore played an important role (and still play that role) in the continuing increase of the market share of sustainable coffee in the Netherlands.

Also remarkable is the small role that the government played in the creation of the Dutch market for sustainable coffee. Policy-makers generally saw unsustainable choices of consumers as a market failure that can be solved by removing the information asymmetry. With the introduction of the Max Havelaar coffee, the information asymmetry problem was solved in their eyes and they believed that the government did not have any other instruments to change the situation. It would take until 2010, when the Dutch Ministry of Economic Affairs, Agriculture and Innovation explicitly supported the Memorandum of Understanding, that government started to actively promote sustainable procurement. This result has encouraged us to rethink the role of Fair Trade. Indeed, as this study suggests, Fair Trade is rapidly achieving its main objectives on the Dutch coffee market. However, it achieves these objectives with the help of other organizations, and the process of change is actually beyond the control of those who initiated it. The introduction of Max Havelaar labeled coffee in the supermarket was not the spark that initiated the creation of a market for certified coffee in the Netherlands. In that respect, it took too long before incumbents in the industry responded. It was Fair Trade, however, that started the development of market creation. According to Douqué, “the knock-on effect of Max Havelaar was much larger than that of Utz or Rainforest.”

Fair Trade did not become the new rule; it became the standard against which others could compare themselves and upon which they could build to develop new standards that would be more feasible in their business models. Fair Trade played a key role in the process but needed the co-existence of others to create a market for sustainable coffee. Raynolds (2009) suggests that mainstreaming Fair Trade introduces market-driven motivations in the Fair Trade community. Our study reaffirms her findings in that the motivations of mainstream coffee roasters who began producing Max Havelaar coffee and the motivations of the market leader to prevent its introduction were both market-driven. This, however, does not mean that a higher market share for Fair Trade is always better (even at the expense of more pragmatic standards). Because Fair Trade should fulfill a role as the standard of comparison, it can provide a critical mirror to other organizations. One way of doing this is by showing that, although the organization is smaller in size, the farmers that are Fair Trade-certified make more progress in developing their livelihoods than those certified by other organizations.

In addition, we note that the scope of sustainability standards has also broadened over the years. Fair Trade began with the goal of improving the position of local farmers in the Third World, but over time, as other standards were introduced in the market, other issues became more prominent, such as maintaining biodiversity. Thus, the market for sustainable coffee started with focus on a single issue but gradually broadened to include other sustainability issues.

Implications

The case on the creation of a market for sustainable coffee in the Netherlands offers important lessons for the ways in which policy-makers can use market forces to achieve sustainability objectives. Our findings suggest that policy-makers should ensure that a consumer label identifying sustainable products exists in the market, although the market share of the labeled product is not of major importance as long as the share is big enough to support a viable business. Rather, the case results suggest that consumers should be aware of the label, even if they do not purchase the labeled product on a routine basis. Next, policy-makers may support the emergence of other standards systems that provide lead companies with sustainability standards that are feasible within the business models of those companies. Finally, our findings imply that policy-makers should allow the co-existence of multiple standard systems to allow the building of brand alliances between brands and standards systems.

Business managers may also draw important lessons from this case because it shows that sustainability issues can best be handled proactively. Otherwise, the issue may enter the market environment in ways that create opportunities for new competitors, and, over time, it may change the rules of competition on the market. In the Dutch coffee market this may have created new opportunities for some companies, but for others (the larger and more established companies in the market), it created threats that could have been avoided by early recognition of the changing norms in the institutional environment and an active response to those changes.

Finally, our study has implications for future research. This case study has focused on one product and one country. The generalizability of the current findings may be tested in other countries and with other products, for example other food products, like meat, or non-food products, like sustainable lumber or apparel, leading to a deeper understanding of how markets can stimulate sustainable development. The emergence of new standard-formulating organizations seems to be leading to the development of a “sustainability standards industry” in its own right. Future research may examine this “industry,” its development, and the emerging rules of the game and strategies across industries. Jointly, these organizations change practices in major product markets; their role as a force for sustainable development deserves more recognition.

Abbreviations

- ACC:

-

Ahold Coffee Company

- AH:

-

Albert Heijn

- CSR:

-

Corporate Social Responsibility

- DE:

-

Douwe Egberts

References

Barrientos, S., Dolan, C., & Tallontire, A. (2003). A gendered value chain approach to codes of conduct in African horticulture. World Development, 31(9), 1511–1526.

Brown, T. J., & Dacin, P. A. (1997). The company and the product: Corporate associations and consumer product responses. Journal of Marketing, 61(1), 68–84.

Coffee Barometer. (2009). Report by the Tropical Commodity Coalition, The Hague.

Consumers International. (2005). From bean to cup: How consumer choice impacts on coffee producers and the environment. Report by Consumers International and IIED, December 2005, London.

Davies, I. A. (2008). Alliances and networks: Creating success in the UK fair trade market. Journal of Business Ethics, 86, 109–126.

Davies, I. A., Doherty, B., & Knox, S. (2010). The rise and stall of a fair trade pioneer: The Cafédirect story. Journal of Business Ethics, 92, 127–147.

Drumwright, M. E. (1994). Socially responsible organizational buying: Environmental concern as a noneconomic buying criteria. Journal of Marketing, 60(July), 1–19.

Fridell, G. (2008). The Co-operative and the corporation: Competing visions of the future of fair trade. Journal of Business Ethics, 86, 81–95.

Gendron, C., Bisaillon, V., & Rance, A. I. O. (2009). The institutionalization of fair trade: More than just a degraded form of social action. Journal of Business Ethics, 86, 63–79.

Giovannucci, D., & Ponte, S. (2005). Standards as a new form of social contract? Sustainability initiatives in the coffee industry. Food Policy, 30, 284–301.

Grewal, R., & Dharwadkar, R. (2002). The role of the institutional environment in marketing channels. Journal of Marketing, 66(July), 82–97.

Healy, M., & Iles, J. (2002). The establishment and enforcement of codes. Journal of Business Ethics, 39(1–2), 117–124.

Hira, A., & Ferrie, J. (2006). Fair trade: Three key challenges for reaching the mainstream. Journal of Business Ethics, 63, 107–118.

Ingenbleek, P. T. M., Binnekamp, M., & Goddijn, S. (2007). Setting standards for CSR: A comparative case study on criteria-formulating organizations. Journal of Business Research, 60, 539–548.

Ingenbleek, P. T. M., & Immink, V. M. (2010). Managing conflicting stakeholder interests: An exploratory case analysis of the formulation of CSR standards in the Netherlands. Journal of Public Policy & Marketing, 29(1), 52–65.

Ingenbleek, P., & Meulenberg, M. T. G. (2006). The battle between “good” and “better”: A strategic marketing perspective on codes of conduct for sustainable agriculture. Agribusiness, 22(4), 451–473.

Kolk, A. (2005). Corporate social responsibility in the coffee sector: The dynamics of MNC responses and code development. European Management Journal, 23(2), 228–236.

Kolk, A., & Van Tulder, R. (2002). The effectiveness of self-regulation: Corporate codes of conduct and child labour. European Management Journal, 20(3), 260–271.

Maignan, I., & McAlister, D. T. (2003). Socially responsible organizational buying: How can stakeholders dictate purchasing policies? Journal of Macromarketing, 23(2), 78–89.

Moore, G. (2004). The fair trade movement: Parameters, issues and future research. Journal of Business Ethics, 53, 73–86.

Oxfam Novib. (2010). Zuivere koffie. De Nederlandse supermarkten doorgelicht. Report (in Dutch), the Hague.

Özçağlar-Toulouse, N., Béji-Bécheur, A., & Murphy, P. E. (2009). Fair trade in France: From individual innovators to contemporary networks. Journal of Business Ethics, 90, 589–606.

Randall, D. C. (2005). An exploration of opportunities for the growth of the fair trade market: Three cases of craft organizations. Journal of Business Ethics, 56, 55–67.

Raynolds, L. T. S. (2009). Mainstreaming fair trade coffee: From partnership to traceability. World Development, 37(6), 1083–1093.

Redfern, A., & Snedker, P. (2002). Creating market opportunities for small enterprises: Experiences of the fair trade movement. Geneva: Report by the International Labour Organization.

Reed, D. (2008). What do corporations have to do with fair trade? Positive and normative analysis from a value chain perspective. Journal of Business Ethics, 86, 3–26.

Sen, S., & Bhattacharya, C. B. (2001). Does doing good always lead to doing better? Consumer reactions to corporate social responsibility. Journal of Marketing Research, 38(2), 225–243.

Waddock, S. A., & Bodwell, C. (2004). Managing responsibility: What can be learned from the quality movement. California Management Review, 47(1), 25–37.

Witkowski, T. H. (2008). Fair trade marketing: An alternative system for globalization and development. Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice, 13(4), 22–33.

World Bank. (2002). Sustainable development in a dynamic world. World Development Report 2003, Washington, DC: World Bank.

Yin, R. (2003). Case study research: Design and methods (3rd ed.). London: SAGE.

Acknowledgment

This study is funded by the expertise programme of the Dutch Ministry of Agriculture, Nature and Food Quality. The authors thank Renée Ros for research assistance.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License which permits any use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and the source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix 1: Case Study Methodology

A case study approach was selected as the principal method for gaining in-depth information about the underlying developments in the market for Fair Trade coffee in the Netherlands (Yin 2003). In order to reconstruct the developments in the Dutch coffee market after the introduction of the first Fair Trade coffee, we relied on a variety of sources. Primary data were collected by conducting 16 interviews with experts, individuals directly involved in initiating Fair Trade coffee, and individuals who could inform us about the strategies pursued by incumbent companies. In order to obtain insight into developments in the market from different perspectives, we selected interviewees representing a range of functions in, or relationships with, the organizations in question (Yin 2003). We made sure that we had respondents who could inform us about critical changes in the market from firsthand experience. These respondents were either approached directly through their current or former employers or approached upon the recommendations of other informants, following a snowballing procedure. For companies that played an important role in the Dutch coffee market, at least two people from each organization were interviewed. To obtain information on general trends from independent informants, several interviews were conducted with industry experts, such as consultants.

For each interview, a separate and unique protocol was developed, beginning with general questions about the development of the market and trends that influenced it and ending with more specific questions on the role that the respondent (or her/his organization) had played in specific phases of the market, discussed in chronological order. These protocols functioned as guidelines for semi-structured interviews. The interviews, which lasted between one and a half and two hours, took place in the interviewees’ offices. The researchers taped all interviews and then made full transcripts. Subsequently, the transcripts were coded using the software program Atlas.ti. Both the transcription and the coding occurred immediately after each interview (rather than being postponed until after the final interviews were completed).

In order to enable data triangulation, we also conducted intensive desk research from articles, newspapers, annual reports, company reports, and public sources such as websites. These supplementary data sources provided background and additional information to the findings from the interviews. Moreover, for each organization represented in the interviews, additional information sources were collected; comparing this information with that obtained in interviews increased the reliability of our findings, especially when informants were relying on memory to answer questions about events that happened years earlier (Yin 2003).

Appendix 2: Teaching Material

Teaching Notes

In this appendix, you may find some questions that can be used for classroom discussion of the case study. The case study described in this article can be distributed in its entirety for first or second year undergraduate students. However, for students who are in their final years, we advise lecturers to remove the discussion and conclusion sections from the paper before distributing it to the students to allow the students to draw more of their own conclusions.

Questions

-

1.

Why do you think that, before the introduction of Max Havelaar, predictions of its future market share were wrong?

-

2.

When Neuteboom decided to produce Fair Trade coffee, they promptly visited the Fair Trade coffee farmers. Why do you think they did that?

-

3.

Why did companies ignore Fair Trade after its introduction? Was that a wise decision?

-

4.

Besides Fair Trade, what were the main developments in the coffee market that led to mainstreaming?

-

5.

What lessons did Utz draw from the experiences of Max Havelaar?

-

6.

DE established a foundation in 2002 that financed projects with coffee farmers, but that activity didn’t affect the company’s core processes. Why is it important that CSR initiatives be developed in conjunction with core processes?

-

7.

What was the reason that the founding organization of Max Havelaar also started to support Utz Kapeh?

-

8.

Explain why the development of a market for sustainable coffee throughout the years can be seen as both a desirable marketing strategy for companies and a necessary requirement for legitimacy.

-

9.

Institutional theory suggests that standards are developed in response to external pressure. Can you describe the pressures that led to the standards that are described in this case study?

-

10.

Give a number of reasons why consumers are only a very small factor in the development of a market for sustainable coffee?

-

11.

Select another industry in which sustainability is an important issue and evaluate the extent to which developments in that industry are comparable to the developments described in this case study.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Ingenbleek, P.T.M., Reinders, M.J. The Development of a Market for Sustainable Coffee in The Netherlands: Rethinking the Contribution of Fair Trade. J Bus Ethics 113, 461–474 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-012-1316-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-012-1316-4