Abstract

Purpose

Germline pathogenic variants in checkpoint kinase 2 (CHEK2) are associated with a moderately increased risk of breast cancer (BC). The spectrum of clinicopathologic features and genetics of these tumors has not been fully established.

Methods

We characterized the histopathologic and clinicopathologic features of 44 CHEK2-associated BCs from 35 women, and assessed responses to neoadjuvant chemotherapy. A subset of cases (n = 23) was additionally analyzed using targeted next-generation DNA sequencing (NGS).

Results

Most (94%, 33/35) patients were heterozygous carriers for germline CHEK2 variants, and 40% had the c.1100delC allele. Two patients were homozygous, and five had additional germline pathogenic variants in ATM (2), PALB2 (1), RAD50 (1), or MUTYH (1). CHEK2-associated BCs occurred in younger women (median age 45 years, range 25–75) and were often multifocal (20%) or bilateral (11%). Most (86%, 38/44) were invasive ductal carcinomas of no special type (IDC-NST). Almost all (95%, 41/43) BCs were ER + (79% ER + HER2-, 16% ER + HER2 + , 5% ER-HER2 +), and most (69%) were luminal B. Nottingham grade, proliferation index, and results of multiparametric molecular testing were heterogeneous. Biallelic CHEK2 alteration with loss of heterozygosity was identified in most BCs (57%, 13/23) by NGS. Additional recurrent alterations included GATA3 (26%), PIK3CA (226%), CCND1 (22%), FGFR1 (22%), ERBB2 (17%), ZNF703 (17%), TP53 (9%), and PPM1D (9%), among others. Responses to neoadjuvant chemotherapy were variable, but few patients (21%, 3/14) achieved pathologic complete response. Most patients (85%) were without evidence of disease at time of study (n = 34). Five patients (15%) developed distant metastasis, and one (3%) died (mean follow-up 50 months).

Conclusion

Almost all CHEK2-associated BCs were ER + IDC-NST, with most classified as luminal B with or without HER2 overexpression. NGS supported the luminal-like phenotype and confirmed CHEK2 as an oncogenic driver in the majority of cases. Responses to neoadjuvant chemotherapy were variable but mostly incomplete.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Checkpoint kinase 2 (CHK2) is a serine/threonine protein kinase encoded by the CHEK2 gene which maintains genomic stability in the setting of DNA damage [1,2,3]. CHK2 is activated by the ATM kinase and in turn, interacts with BRCA1, BRCA2, p53, CDC25, and other effectors to initiate DNA repair, apoptosis, and cell cycle arrest [4,5,6]. Germline CHEK2 variants were first described in patients without germline TP53 mutations who were thought to meet clinical criteria for Li-Fraumeni syndrome [7, 8], although the association with Li-Fraumeni syndrome has since been negated [9]. Germline CHEK2 variants have now been identified in ~ 1% of the population [9], and pathogenic variants (PVs) are causally linked to multiple types of cancer, including colon cancer and breast cancer (BC), further highlighting the functional relevance of CHEK2 in safeguarding genome integrity [3] [10]. Germline CHEK2 PVs confer a lifetime BC risk ranging from 20 to 44%, depending on family history of BC [11,12,13]. Furthermore, individuals with the higher risk c.1100delC allele carry a BC risk of up to two times higher in women and ten times higher in men when compared to non-carriers [14,15,16]. Accordingly, clinical guidelines currently recommend enhanced BC screening in individuals with protein truncating CHEK2 variants [17].

Investigations into the phenotype and clinical behavior of CHEK2-associated BCs have been limited. CHEK2-associated BCs tend to occur in younger women, with higher rates of bilateral disease [12], and frequently express estrogen receptor (ER) and/or progesterone receptor (PR) [12, 13]. Interestingly, in contrast to BRCA1/2-related cancers, CHEK2-associated BCs appear to lack the genetic characteristics of homologous recombination DNA repair deficiency [18, 19]. Biallelic CHEK2 inactivation has been observed in some but not all CHEK2-associated BCs [19]. The precise mechanistic relationship between CHEK2 and BC development currently remains uncertain.

In order to characterize BC that develop in the setting of germline CHEK2 variants, we explored the clinicopathologic, histologic, and genetic features of BCs arising in a consecutive series of patients with pathogenic or likely pathogenic germline CHEK2 variants (P/LPVs) at our institution.

Methods

Study population

The institutional review board of the University of California San Francisco (UCSF) approved this study. Patients with P/LPVs in CHEK2 who underwent breast tissue sampling were retrospectively identified over a 15-year period (2008 to 2023) using a pathology database. All germline variants in this cohort (n = 35) with invasive BC were reviewed by a board-certified genetic counselor (AB) and classified as P/LPVs according to the ClinVar database [20].

Study design

All slides were reviewed by at least one breast pathologist (CJS, YYC, and/or GK). For primary BCs, ER, PR, and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) were evaluated and scored according to ASCO/CAP guidelines [21, 22]. Ki67 was scored according to recommendations of the International Ki67 in Breast Cancer Working Group [23]. Immunohistochemical surrogates of molecular subtype were classified based on St. Galen criteria as previously described using either 14% or 20% cut-offs for Ki-67 [24]. Tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) were assessed based on recommendations by the TILs Working Group [25]. For neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NACT)-treated tumors, assessment of tumor cellularity and residual cancer burden (RCB) index were calculated according to methods previously described [26]. Clinicopathologic and outcome data were retrieved from the electronic medical record.

Targeted next-generation DNA sequencing

Tumor tissues were selected from primary BCs (n = 21), lymph node metastasis (n = 1), lung metastasis (n = 1), and liver metastasis (n = 1) for capture-based targeted next-generation DNA sequencing (NGS). Sequencing was performed at the UCSF Clinical Cancer Genomics Laboratory using an assay that targets all coding regions of ~ 500 cancer-related genes, select introns from 40 genes, and TERT promoter, and analyzed according to methods previously described [27].

Results

Study overview

The workflow for this study is depicted in Fig. 1. We identified 67 patients with CHEK2 P/LPVs who underwent core biopsy of the breast. Most patients (50/67, 75%) had intraductal epithelial atypia or in situ or invasive carcinoma on core biopsy. Of these, noninvasive disease included atypical ductal hyperplasia (4%, 3/67), lobular neoplasia (atypical lobular hyperplasia or lobular carcinoma in situ) (6%, 4/67), and ductal carcinoma in situ (12%, 8/67). Invasive BC was identified in 52% of patients (35/67), and these patients comprised the subsequent study population. In total, 44 invasive BCs were analyzed from these 35 patients. Most patients (88%, 15/17) without atypia or carcinoma on core biopsy were under active surveillance, with two patients opting for bilateral risk-reducing mastectomy (Fig. 1).

Indications for genetic testing and description of germline CHEK2 variants in patients with invasive breast cancer

Genetic testing followed the personal diagnosis of BC in 83% (29/35) of patients (Table 1). A smaller subset (11%, 4/35) underwent genetic testing after a germline CHEK2 variant was identified in a family member. Most patients (79%, 27/34) had a family history of BC, with 41% (14/34) occurring in a first degree relative (Table 1). Three patients had a previous history of BC prior to presentation at our institution (9%, 3/35).

A summary of the germline CHEK2 P/LPVs in patients that developed invasive BC and associated clinical characteristics are detailed in Supplementary Table S1. CHEK2 P/LPVs consisted of frameshift (17/35, 49%), missense (26%, 9/35), and splice site (11%, 4/35) mutations, as well as exonic deletions (14%, 5/35) (Table 2). The cohort was enriched for CHEK2 c.1100delC (p.T367fs) variants (40%, 14/35), which is thought to portend the highest BC risk [14,15,16]. The second most common variant was c.1283C > T (p.S428F) (9%, 3/35), a low penetrance missense mutation thought to abrogate the kinase function of CHK2 [28]. Nearly all patients (33/35, 94%) were heterozygous CHEK2 carriers (Table 2). Two patients (patient 2, c.1100delC and patient 32, c.499G > A) were homozygous with a family history of BC in a first-degree relative. Five patients (14%) additionally harbored PVs in other genes associated with BC risk, including ATM (c.1027_1030del, p.E343Ifs and c.237del, p.Lys79fs), PALB2 (c.2827_2830del, p.E943Sfs), RAD50 (c.2517dupA, p.D480fs) and MUTYH (c.536A > G, p.Y179C) (Supplementary Table S1).

Clinicopathologic characteristics of CHEK2-associated breast cancers

The clinicopathologic features of CHEK2-associated invasive BCs are shown in Table 3. All patients were women. The median age at diagnosis was 45 years (range 25–75, Table 3). Most presented with a palpable mass (54%, 19/35). The remainder had either a mammographically detected mass (29%, 10/35) or calcifications (17%, 6/35). Four patients had synchronous bilateral BCs (11%, 4/35) and seven had multifocal BC (20%, 7/35). The mean tumor size in non-treated cases was 1.3 cm (range < 0.1 to 5.4) (Table 3). Lymph node metastases were present in 38% of cases (13/34).

BCs were predominantly invasive ductal carcinomas of no special type (IDC-NST) (86%, 38/44). Other histologic types were invasive lobular carcinoma (7%, 3/44, including solid [1], alveolar [1], and classic [1] patterns), invasive carcinoma with ductal and lobular features (5%, 2/44), and invasive papillary carcinoma (2%, 1/44). BCs were most often Nottingham grade 2 (57%, 25/44), with 25% (11/44) grade 3 and 18% (8/44) grade 1. TILs were sparse (< 10%) in most (89%, 34/38) cases and > 20% in only one case (3%, 1/34) (Supplemental Table S2).

Nearly all BCs were ER + (95%, 41/43), including 79% (34/43) ER + HER2- and 16% (7/43) ER + HER2 + . Both ER- tumors were HER2 + (5%, 2/43). Of the nine total HER2 + BCs, seven (78%) arose in a background of CHEK2 c.1100delC, and, conversely, 43% (6/14) of BCs arising in patients with CHEK2 c.1100delC were HER2 + . No patients developed triple negative BC. The Ki67 proliferation index was ≥ 30% in 32% (10/31), 6–29% in 58% (18/31), and ≤ 5% in 10% (3/31) of cases. Using immunohistochemical surrogates for molecular subtyping, most (69%, 25/36) BCs were classified as luminal B (50%, 18/36 Luminal B HER2-, 19%, 7/36 Luminal B HER2 + ; using ≥ 14% Ki-67 cutpoint) [24]. One-quarter (25%, 9/36) were luminal A, and only 6% (2/36) were HER2-enriched. Results were similar when using ≥ 20% Ki-67 cutpoint for Luminal B (67% luminal B) (Supplemental Table S2).

OncotypeDX scores were available for 12 patients and were variable, with most (83%) scores falling into the low (5/12) or intermediate categories (5/12). Of the two patients with high OncotypeDX scores (16%, 2/12), one developed lung metastasis. MammaPrint assay scores were available for 13 patients and stratified nearly equally into low-risk (46%, 6/13) and high-risk categories (54%, 7/13).

Next-generation DNA sequencing

Targeted next-generation DNA sequencing was performed on 23 BCs (24 samples) from 20 patients, including 21 primary BCs, one lymph node metastasis,one liver metastasis, and one lung metastasis. The results are shown in Fig. 2. Sequenced primary BCs included synchronous unilateral tumors from two patients and synchronous bilateral tumors from one patient. Most (92%, 21/23) sequenced tumors were IDC-NST. All were ER + , and 22% (5/23) were HER2 + by immunohistochemistry and/or fluorescence in situ hybridization, including a metachronous ER + HER2 + lung metastasis in Patient 11.

Biallelic CHEK2 alteration was detected in 13 of 23 BCs (57%), which was due to somatic loss of heterozygosity (LOH) of the germline CHEK2 allele in all cases. All sequenced BCs arising in patients with germline CHEK2 c.1100delC (n = 6) showed biallelic CHEK2 inactivation via LOH. In one case (patient 26), an additional somatic missense CHEK2 mutation (p.K373E) was identified in an invasive lobular carcinoma (ILC) arising in a 70-year-old germline CHEK2 exon 9 deletion carrier. Whether this second CHEK2 hit was in cis or trans with the germline allele could not be determined. A synchronous ipsilateral ILC in the same patient was heterozygous for the germline CHEK2 mutation with no additional CHEK2 alterations. The genetic profiles of the synchronous ILCs in this patient were also otherwise distinct, including different inactivating CDH1 mutations (p.T115fs and p.N315fs) among other alterations (Fig. 2).

Aside from biallelic alteration of CHEK2, recurrent alterations included inactivating GATA3 mutations (6/23, 26%), PIK3CA hotspot (p.H1047R) mutations or amplification (6/23, 26%), and amplifications of CCND1 (5/23, 22%), FGFR1 (5/23, 22%), ERBB2 (4/23, 17%), GAB2 (4/23, 17%), ZNF703 (4/23, 17%), GPR124 (4/23, 17%), PPM1D (2/23, 9%), and MDM2 (2/23, 9%). TP53 mutation were infrequent (2/23, 9%).

Invasive BCs from 3 of the 5 patients with concurrent PVs in additional BC risk genes were sequenced (Fig. 2). Patient 13 (CHEK2 c.1100delC and PALB2 c.2827_2830del) presented with a 2 cm Nottingham grade 3 ER + HER2- IDC-NST at age 25 (Oncotype 21). Tumor sequencing revealed LOH in CHEK2 and PALB2, as well as CCND1,FGFR1, GPR124, ZNF217, ZNF703, and PTPN1 amplifications. Patient 22 (CHEK2 c.1100delC and ATM c.237del) presented with a Nottingham grade 3 ER + HER2- IDC-NST at age 30 (MammaPrint high-risk). Tumor sequencing revealed LOH in CHEK2 and ATM, as well as CCND1 and GAB2 amplifications. This patient received neoadjuvant chemotherapy and was one of only three patients to achieve pCR. Patient 31 (CHEK2 c.707 T > C (p. Leu236Pro and RAD50 c.2517dupA, p. D480fs) presented at age 45 with synchronous bilateral IDC-NST. No additional somatic alterations were identified on sequencing of either tumor.

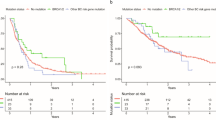

Treatment and Outcome

Treatment and outcomes of CHEK2-associated BCs are shown in Table 4. Most patients underwent mastectomy (69%, 24/35) compared to lumpectomy (31%, 11/35). Fourteen patients received NACT (40%, 14/35), and five patients received neoadjuvant hormonal therapy (NAHT) (14%, 5/35). In line with the high frequency of ER + BCs, nearly all (88%, 30/34) patients received adjuvant hormonal therapy. Twelve patients received adjuvant radiotherapy (35%), and 13 patients received adjuvant chemotherapy (38%).

Clinical follow-up was available for 34 patients (97%, 34/35) with a mean interval of 50 months. One patient (3%, 1/34) developed local recurrence, which was an axillary recurrence of ER + IDC-NST 72 months after bilateral mastectomy. Five patients (15%) developed distant metastases, with metastatic sites including liver (2), bone (2) and lung (1) (Supplementary Table S2). The majority of patients (85%, 29/34) had no evidence of disease at time of study, whereas 12% (4/34) are alive with disease. Only one patient (3%) died of disease following a poor response to NACT, liver metastasis at 58 months, and death at 117 months. Among the 11 patients who opted for breast conservation, none developed local recurrence during the follow-up period.

Response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy

Treatment responses to NACT of 18 CHEK2-associated BCs arising in 14 patients are summarized in Supplemental Table S3. All BCs (100%) showed a clinical reduction in tumor size based on tumor size at pathologic examination compared to pre-treatment magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). All BCs with available data showed a post-treatment reduction in Ki67 proliferation index compared to pre-treatment scores. By RCB calculation, most treated BCs were RCB-II (11/18, 61%) or RCB-I (4/18, 22%), with no RCB-III tumors. Pathologic complete response (pCR) was observed in only three patients (3/14, 21%), two of which had HER2 + BC. In cases with residual cancer, invasive tumor cellularity ranged from < 1% to 50% and was ≥ 30% in 50% (7/14) of tumors.

Discussion

In summary, CHEK2-associated invasive BCs tended to arise in younger women with a strong family history of BC and were often multifocal and bilateral. The tumors were mostly immune-poor ER + IDC-NST of predominantly luminal B subtype and were heterogeneous in terms of histologic grade, HER2 status, proliferation index, and multi-parametric molecular testing. NGS overall showed luminal-like genetics and biallelic CHEK2 alteration via LOH as an oncogenic driver in most cases. BCs arising in patients with concurrent germline PVs in the DNA damage genes PALB2 and ATM (but not RAD50) also showed LOH in these genes. Most patients with CHEK2-associated BCs had partial responses to NACT, with few achieving pCR.

Most but not all CHEK2-associated BCs showed biallelic CHEK2 alteration via LOH, which is in keeping with incomplete rates of LOH seen in prior studies [18, 19, 29, 30]. A recent study found high rates of CHEK2 LOH in BCs arising in c.1100delC carriers compared to lower rates in other CHEK2 variants [19]. Consistent with this, we found CHEK2 LOH in all BCs arising in c.1100delC carriers (6/6) but only in 47% (8/17) of BCs arising in other variants. Taken together, our findings and those of others raise consideration that at least some CHEK2 variants may function via haploinsufficiency in driving BC, whereas others (such as c.1100delC) may require bilallelic inactivation. This is in contrast to most other germline BC risk genes, such as BRCA1/2, PALB2, and ATM, PVs of which often show biallelic loss of function in BC [29]. Alternatively, CHK2 inactivation may also be due to non-genetic mechanisms in cases without LOH, and future studies may help address this issue.

Most BCs arising in our population of CHEK2 carriers were ER + IDC-NST, predominantly of luminal B subtype, with a minority of tumors being luminal A or HER2-enriched, and none being triple negative. These findings are consistent with previous reports showing a predominance of ER/luminal BC and HER2 overexpression in this setting [9, 12, 19, 31, 32]. Aside from biallelic CHEK2 inactivation in the majority of cases, the mutational repertoire of the sequenced luminal BCs in our series was otherwise similar to other luminal BCs and included recurrent aberrations in genes such as PIK3CA, GATA3, CCND1, FGFR1, and ERBB2, with a low frequency of TP53 mutations. Our results are thus overall consistent with those of previous studies [18, 19, 31, 33,34,35] and highlight CHEK2 as a dominant oncogenic driver in these tumors while also supporting a model in which CHEK2 may act as a facilitator or accelerator of tumorigenesis that is otherwise subtype-specific. This model of CHEK2-facilitated tumorigenesis was previously put forth by Massink et al. in their study describing luminal-like copy number profiles of BCs arising in CHEK2 c.1100delC carriers [18].

Concurrent germline P/LPVs in multiple hereditary BC risk genes (so-called double heterozygotes) are rare, and data regarding cancer risk and clinical implications are scarce. The majority of reported double heterozygotes in the literature include BRCA1 and/or BRCA2, with only few studies and case reports describing double heterozygosity exclusively involving other BC risk genes, such as CHEK2, ATM, PALB2, NBS1, and BLM [36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44]. Given the rarity of these events, conclusions regarding cancer risk, cancer phenotype, patient surveillance, and clinical management of these cases are limited. It has been suggested that BRCA1/2 and CHEK2 double heterozygotes do not have increased BC risk or a different BC phenotype beyond what is expected for BRCA1/2 variants [39, 40, 44]. Whether a similar principle holds for double heterozygotes involving CHEK2 and non-BRCA1/2 BC risk genes is not known due to paucity of data. Taken as a whole, BCs arising in double heterozygotes do not appear to present at younger age or with increased bilaterality compared to single heterozygotes [39]. Of the five double heterozygotes involving CHEK2 with ATM, PALB2, RAD50, or MUTYH in our study, we noted a younger age of BC presentation than the cohort median in three cases (CHEK2 c.433delC/MUTYH c.536A > G, age 34; CHEK2 c.1100delC/PALB2 c.2827_2830del, age 25; CHEK2 c.1100delC/ATM c.237del, age 29), and bilateral and multifocal tumors in only one patient (CHEK2 c.707 T > C/RAD50 c.2517dupA). We therefore find no compelling evidence of a synergistic effect compared to CHEK2 carriers alone, but note that the small number of such cases in our series significantly limits meaningful conclusions. There is similarly little data on BC risk and phenotype in CHEK2 homozygotes or compound heterozygotes, although available data suggests that these patients may have higher BC risk, present at younger age, and more often have a second BC diagnosis compared to heterozygotes [45,46,47]. Our study included two CHEK2 homozygotes (c.1100delC and c.499G > A), who presented with BC at 45 and 39 years of age, respectively, and have not developed additional BCs at time of study.

Ours is one of few studies assessing the response of CHEK2-associated BCs to NACT. Although decreased post-treatment tumor size and Ki67 proliferative index reflected treatment effect in all evaluable cases, only three patients in our series achieved pCR. Two tumors with pCR were HER2 + (Luminal B HER2 + and HER2 enriched). These results are not surprising, given the overall lower pCR rates of ER + /luminal tumors [48, 49] as well as the absence of robust homologous recombination DNA repair deficiency in CHEK2-associated BC [18, 19, 30]. Indeed, our results are similar to a prior study of poor NACT responses in eight CHEK2 patients with BC, in which responses to NACT were also found to be worse in CHEK2 carriers when compared to non-carriers [49]. Larger studies are required to confidently compare NACT sensitivities of CHEK2-associated ER + BCs to other BCs. We speculate that the absence of significant immune cell infiltration may also impact response rates to NACT.

Guidelines recommend annual mammography with consideration for magnetic resonance imaging starting at age 40 in patients with CHEK2 P/LPVs. However, unlike for patients with germline BRCA1 or BRCA2 alterations, there are currently no guidelines regarding risk-reducing mastectomy in CHEK2 carriers, and decision making is generally based on individualized and family risk [17]. There is a paucity of data evaluating recurrence rates after breast conservation versus unilateral or bilateral mastectomy in CHEK2 carriers with BC, although some studies have suggested a higher risk of contralateral BC [32, 50, 51]. In our study, only 11 patients with BC opted for breast conservation, and none experienced local recurrence. On the other hand, we found higher than expected rates of bilateral and multifocal tumors compared to the general population, which is consistent with prior studies [52] and has implications arguing against breast conservation. Aside from CHEK2 germline status and type of CHEK2 variant (i.e. c.1100delC vs other), patient age at presentation, family history, and patient preferences, should also be considered when planning surgical intervention and surveillance for these patients.

Data availability

Inquiries about data availability should be directed to the authors.

References

Filippini SE, Vega A (2013) Breast cancer genes: beyond BRCA1 and BRCA2. Front Biosci 18(4):1358–1372. https://doi.org/10.2741/4185

Lukas C, Bartkova J, Latella L et al (2001) DNA damage-activated kinase Chk2 is independent of proliferation or differentiation yet correlates with tissue biology. Cancer Res 61:4990–4993

Bartek J, Lukas J (2003) Chk1 and Chk2 kinases in checkpoint control and cancer. Cancer Cell 3(5):421–429. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1535-6108(03)00110-7

Stolarova L, Kleiblova P, Janatova M et al (2020) CHEK2 germline variants in cancer predisposition: stalemate rather than checkmate. Cells. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells9122675

Zhang J, Willers H, Feng Z et al (2004) Chk2 phosphorylation of BRCA1 regulates DNA double-strand break repair. Mol Cell Biol 24(2):708–718. https://doi.org/10.1128/MCB.24.2.708-718.2004

Apostolou P, Papasotiriou I (2017) Current perspectives on CHEK2 mutations in breast cancer. Breast Cancer (Dove Med Press) 9:331–335. https://doi.org/10.2147/BCTT.S111394

Ruijs MWG, Broeks A, Menko FH et al (2009) The contribution of CHEK2 to the TP53-negative Li-Fraumeni phenotype. Hered Cancer Clin Pract 7(1):4. https://doi.org/10.1186/1897-4287-7-4

Bell DW, Varley JM, Szydlo TE et al (1999) Heterozygous germ line hCHK2 mutations in Li-Fraumeni syndrome. Science 286:2528–2531. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.286.5449.2528

Bychkovsky BL, Agaoglu NB, Horton C et al (2022) Differences in Cancer Phenotypes Among Frequent CHEK2 Variants and Implications for Clinical Care—Checking CHEK2. JAMA Oncol 8(11):1598. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaoncol.2022.4071

Lu H-M, Li S, Black MH et al (2019) Association of breast and ovarian cancers with predisposition genes identified by large-scale sequencing. JAMA Oncol 5(1):51–57. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.2956

Couch FJ, Shimelis H, Hu C et al (2017) Associations between cancer predisposition testing panel genes and breast cancer. JAMA Oncol 3:1190–1196. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaoncol.2017.0424

Breast Cancer Association Consortium, Dorling L, Carvalho S et al (2021) Breast cancer risk genes - association analysis in more than 113,000 women. N Engl J Med 384(5):428–439. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1913948

Cybulski C, Wokołorczyk D, Jakubowska A et al (2011) Risk of breast cancer in women with a CHEK2 mutation with and without a family history of breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 29(28):3747–3752. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2010.34.0778

Weischer M, Bojesen SE, Ellervik C, Tybjaerg-Hansen A, Nordestgaard BG (2008) CHEK2*1100delC genotyping for clinical assessment of breast cancer risk: meta-analyses of 26,000 patient cases and 27,000 controls. J Clin Oncol 26(4):542–548. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2007.12.5922

CHEK2 Breast Cancer Case-Control Consortium (2004) CHEK2*1100delC and susceptibility to breast cancer: a collaborative analysis involving 10,860 breast cancer cases and 9,065 controls from 10 studies. Am J Hum Genet 74(6):1175–1182. https://doi.org/10.1086/421251

The CHEK2-Breast Cancer Consortium. Low-penetrance susceptibility to breast cancer due to CHEK2*1100delC in noncarriers of BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations. Nat Genet. 2002;31(1):55–59. doi:https://doi.org/10.1038/ng879

The American Society of Breast Surgeons. Consensus Guideline on Genetic Testing for Hereditary Breast Cancer. https://www.breastsurgeons.org/docs/statements/Consensus-Guideline-on-Genetic-Testing-for-Hereditary-Breast-Cancer.pdf. Published 2019. Accessed May 30, 2023.

Massink MPG, Kooi IE, Martens JWM, Waisfisz Q, Meijers-Heijboer H (2015) Genomic profiling of CHEK2*1100delC-mutated breast carcinomas. BMC Cancer 15(11):877. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-015-1880-y

Mandelker D, Kumar R, Pei X et al (2019) The Landscape of Somatic Genetic Alterations in Breast Cancers from CHEK2 Germline Mutation Carriers. JNCI Cancer Spectrum 3:pkz027. https://doi.org/10.1093/jncics/pkz027

Landrum MJ, Lee JM, Benson M et al (2018) ClinVar: improving access to variant interpretations and supporting evidence. Nucleic Acids Res 46:D1062–D1067. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkx1153

Hammond MEH, Hayes DF, Dowsett M et al (2010) American Society of Clinical Oncology/College Of American Pathologists guideline recommendations for immunohistochemical testing of estrogen and progesterone receptors in breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 28:2784–2795. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2009.25.6529

Wolff AC, Hammond MEH, Hicks DG et al (2013) Recommendations for human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 testing in breast cancer: American Society of Clinical Oncology/College of American Pathologists clinical practice guideline update. J Clin Oncol 31:3997–4013. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2013.50.9984

Leung SCY, Nielsen TO, Zabaglo LA et al (2019) Analytical validation of a standardised scoring protocol for Ki67 immunohistochemistry on breast cancer excision whole sections: an international multicentre collaboration. Histopathology 75:225–235. https://doi.org/10.1111/his.13880

Goldhirsch A, Winer EP, Coates AS et al (2013) Personalizing the treatment of women with early breast cancer: highlights of the St Gallen International Expert Consensus on the Primary Therapy of Early Breast Cancer 2013. Ann Oncol 24:2206–2223. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdt303

Salgado R, Denkert C, Demaria S et al (2015) The evaluation of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) in breast cancer: recommendations by an International TILs Working Group 2014. Ann Oncol 26:259–271. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdu450

Symmans WF, Peintinger F, Hatzis C et al (2007) Measurement of residual breast cancer burden to predict survival after neoadjuvant chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol 25:4414–4422. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2007.10.6823

Krings G, Joseph NM, Bean GR et al (2017) Genomic profiling of breast secretory carcinomas reveals distinct genetics from other breast cancers and similarity to mammary analog secretory carcinomas. Mod Pathol 30:1086–1099. https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.2017.32

Shaag A, Walsh T, Renbaum P et al (2005) Functional and genomic approaches reveal an ancient CHEK2 allele associated with breast cancer in the Ashkenazi Jewish population. Hum Mol Genet 14:555–563. https://doi.org/10.1093/hmg/ddi052

Lim BWX, Li N, Mahale S et al (2023) Somatic inactivation of breast cancer predisposition genes in tumors associated with pathogenic germline variants. J Natl Cancer Inst 115:181–189. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/djac196

Iyevleva AG, Aleksakhina SN, Sokolenko AP et al (2022) Somatic loss of the remaining allele occurs approximately in half of CHEK2-driven breast cancers and is accompanied by a border-line increase of chromosomal instability. Breast Cancer Res Treat 192:283–291. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-022-06517-3

Nagel JHA, Peeters JK, Smid M et al (2012) Gene expression profiling assigns CHEK2 1100delC breast cancers to the luminal intrinsic subtypes. Breast Cancer Res Treat 132:439–448. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-011-1588-x

Toss A, Tenedini E, Piombino C et al (2021) Clinicopathologic profile of breast cancer in germline ATM and CHEK2 mutation carriers. Genes (Basel) 12:616. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes12050616

Nik-Zainal S, Davies H, Staaf J et al (2016) Landscape of somatic mutations in 560 breast cancer whole-genome sequences. Nature 534:47–54. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature17676

Smid M, Schmidt MK, Prager-van der Smissen WJC et al (2023) Breast cancer genomes from CHEK2 c.1100delC mutation carriers lack somatic TP53 mutations and display a unique structural variant size distribution profile. Breast Cancer Res 25:53. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13058-023-01653-0

Ades F, Zardavas D, Bozovic-Spasojevic I et al (2014) Luminal B breast cancer: molecular characterization, clinical management, and future perspectives. J Clin Oncol 32:2794–2803. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2013.54.1870

Colombo M, Mondini P, Minenza E et al (2023) A novel BRCA1 splicing variant detected in an early onset triple-negative breast cancer patient additionally carrying a pathogenic variant in ATM: A case report. Front Oncol 13:1102184. https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2023.1102184

Megid TBC, Barros-Filho MC, Pisani JP, Achatz MI (2022) Double heterozygous pathogenic variants prevalence in a cohort of patients with hereditary breast cancer. Front Oncol 12:873395. https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2022.873395

Sukumar J, Kassem M, Agnese D et al (2021) Concurrent germline BRCA1, BRCA2, and CHEK2 pathogenic variants in hereditary breast cancer: a case series. Breast Cancer Res Treat 186:569–575. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-021-06095-w

Sokolenko AP, Bogdanova N, Kluzniak W et al (2014) Double heterozygotes among breast cancer patients analyzed for BRCA1, CHEK2, ATM, NBN/NBS1, and BLM germ-line mutations. Breast Cancer Res Treat 145:553–562. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-014-2971-1

Rebbeck TR, Friebel TM, Mitra N et al (2016) Inheritance of deleterious mutations at both BRCA1 and BRCA2 in an international sample of 32,295 women. Breast Cancer Res 18:112. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13058-016-0768-3

Turnbull C, Seal S, Renwick A et al (2012) Gene-gene interactions in breast cancer susceptibility. Hum Mol Genet 21:958–962. https://doi.org/10.1093/hmg/ddr525

Leegte B, van der Hout AH, Deffenbaugh AM et al (2005) Phenotypic expression of double heterozygosity for BRCA1 and BRCA2 germline mutations. J Med Genet 42:e20. https://doi.org/10.1136/jmg.2004.027243

Le Page C, Rahimi K, Rodrigues M et al (2020) Clinicopathological features of women with epithelial ovarian cancer and double heterozygosity for BRCA1 and BRCA2: A systematic review and case report analysis. Gynecol Oncol 156:377–386. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ygyno.2019.11.019

Cybulski C, Górski B, Huzarski T et al (2009) Effect of CHEK2 missense variant I157T on the risk of breast cancer in carriers of other CHEK2 or BRCA1 mutations. J Med Genet 46:132–135. https://doi.org/10.1136/jmg.2008.061697

Soleimani T, Bourdon C, Davis J, Fortes T (2023) A case report of biallelic CHEK2 heterozygous variant presenting with breast cancer. Clin Case Rep 11:e6820. https://doi.org/10.1002/ccr3.6820

Adank MA, Jonker MA, Kluijt I et al (2011) CHEK2*1100delC homozygosity is associated with a high breast cancer risk in women. J Med Genet 48:860–863. https://doi.org/10.1136/jmedgenet-2011-100380

Rainville I, Hatcher S, Rosenthal E et al (2020) High risk of breast cancer in women with biallelic pathogenic variants in CHEK2. Breast Cancer Res Treat 180:503–509. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-020-05543-3

Prat A, Fan C, Fernández A et al (2015) Response and survival of breast cancer intrinsic subtypes following multi-agent neoadjuvant chemotherapy. BMC Med 13:303. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-015-0540-z

Pfeifer W, Sokolenko AP, Potapova ON et al (2014) Breast cancer sensitivity to neoadjuvant therapy in BRCA1 and CHEK2 mutation carriers and non-carriers. Breast Cancer Res Treat 148:675–683. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-014-3206-1

Morra A, Mavaddat N, Muranen TA et al (2023) The impact of coding germline variants on contralateral breast cancer risk and survival. Am J Hum Genet 110:475–486. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajhg.2023.02.003

Yadav S, Boddicker NJ, Na J et al (2023) Contralateral breast cancer risk among carriers of germline pathogenic variants in ATM, BRCA1, BRCA2, CHEK2, and PALB2. J Clin Oncol 41:1703–1713. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.22.01239

Wolters R, Wöckel A, Janni W et al (2013) Comparing the outcome between multicentric and multifocal breast cancer: what is the impact on survival, and is there a role for guideline-adherent adjuvant therapy? A retrospective multicenter cohort study of 8,935 patients. Breast Cancer Res Treat 142:579–590. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-013-2772-y

Acknowledgements

We thank the UCSF Clinical Cancer Genomic Laboratory and Lyubov Loza for technical assistance.

Funding

This study was funded by the UCSF Department of Pathology Clinical Research Endowment Fund and Rebecca Frankel Research Award (awarded to CJS).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

CJS, YYC and GK conceived the work. CJS, NK, AB, RM and GK analyzed the data. CJS wrote the original draft. CJS, YYC, GK wrote and edited the final draft. AB, LE, RM, YYC and GK supervised the work. All authors read and approved the final version of the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

All authors declare no conflict of interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Schwartz, C.J., Khorsandi, N., Blanco, A. et al. Clinicopathologic and genetic analysis of invasive breast carcinomas in women with germline CHEK2 variants. Breast Cancer Res Treat 204, 171–179 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-023-07176-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-023-07176-8