Abstract

Purpose

Safe de-intensification of adjuvant radiotherapy (RT) for early breast cancer (BC) is currently under evaluation. Little is known about the patient experience of de-escalation or its association with fear of cancer recurrence (FCR), a key issue in survivorship. We conducted a cross-sectional study to explore this association.

Methods

Psychometrically validated measures including the Fear of Cancer Recurrence Inventory-Short Form were completed by three groups of women with early BC: Women in the PROSPECT clinical trial who underwent pre-surgical MRI and omitted RT (A), women who underwent pre-surgical MRI and received RT (B); and women who received usual care (no MRI, received RT; C). Between group differences were analysed with non-parametric tests. A subset from each group participated in a semi-structured interview. These data (n = 44) were analysed with directed content analysis.

Results

Questionnaires from 400 women were analysed. Significantly lower FCR was observed in Group A (n = 125) than in Group B (n = 102; p = .002) or Group C (n = 173; p = .001), and when participants were categorized by RT status (omitted RT vs received RT; p < .001). The proportion of women with normal FCR was significantly (p < .05) larger in Group A (62%) than in Group B (35%) or Group C (40%). Two qualitative themes emerged: ‘What I had was best’ and ‘Coping with FCR’.

Conclusions

Omitting RT in the setting of the PROSPECT trial was not associated with higher FCR than receiving RT. Positive perceptions about tailored care, lower treatment burden, and trust in clinicians appear to be protective against FCR.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

A priority in breast cancer (BC) care is to achieve optimal outcomes while avoiding both over-treatment and under-treatment of the disease. Recent advances show a steady progression towards de-escalation of treatment in lower risk disease, where patients are carefully selected for the most appropriate treatment approach to minimize toxicities and maximize outcomes [1]. Among these outcomes, psychosocial wellbeing, and quality of life (QoL) are key considerations.

One QoL outcome of particular significance in the context of BC is fear of cancer recurrence (FCR), defined as “fear, worry or concern relating to the possibility that cancer will come back or progress” [2]. FCR can become a concern shortly after diagnosis or treatment, persists long after treatment completion [3] and remains relatively stable over the survivorship trajectory [3]. It is one of the most common psychological phenomena in BC survivors.

FCR severity is most frequently measured using a subscale of the Fear of Cancer Recurrence Inventory (FCRI-SF) [4, 5]. On this scale, scores ≥ 13 indicate possible clinical FCR and warrant additional investigation, while scores ≥ 22 indicate clinical FCR that needs specialized intervention [3]. Approximately 60–88% of women with BC score ≥ 13, and 16–22% score ≥ 22 [3]. Clinical FCR is characterized by constant, intrusive thoughts about cancer; interpretation of mild, unrelated symptoms as a sign of recurrence; a belief that cancer will return regardless of actual prognosis; and an inability to make longer-term plans due to cancer worry[2]. FCR is a common reason for seeking professional clinical support and is associated with psychological distress, poorer social and occupational functioning, and increased health care costs [6].

While the prevalence and impacts of FCR in women with BC are well known, understanding of the predictors of FCR is still evolving. Surprisingly, prognosis and more intensive treatment have not been clearly associated with FCR [7]. More specifically, the association between adjuvant radiotherapy (RT) and FCR is unclear. In BC, a weak positive association between RT and FCR has been reported, consistent with other cancers [8].

While clinical trials have shown that adjuvant RT decreases the risk of local recurrence after breast conserving surgery for early BC, most women are cured with surgery alone [9]. RT is associated with significant short-term and longer-term morbidity, is expensive, and prolongs treatment duration [10]. Consequently, defining a sufficiently low-risk population in whom RT can be safely de-escalated is desirable. Many previous and ongoing studies seek to achieve this aim. One such study is PROSPECT (Post-operative Radiotherapy Omission in Selected Patients with Early breast Cancer Trial, ANZ-1002), a prospective non-randomized cohort study where women with unequivocally unifocal early BC on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and favourable surgical pathology were treated with breast conserving surgery and adjuvant systemic therapy but without adjuvant RT. Of the 443 patients registered for PROSPECT, 201 were treated on study without RT. The primary outcome of PROSPECT was reported in 2022, showing a very low rate of recurrence [11].

The impact of treatment de-escalation by omission of RT on FCR has not been systematically studied. Among trials of post-operative RT in BC, only the PRIME (Post-operative Radiotherapy In Minimum-risk Elderly) trial [12] included measurement of FCR. PRIME included women older than 65 years with low-risk BC treated with breast conserving surgery and endocrine therapy, with or without RT. This study did not employ a validated inventory to measure FCR but relied on qualitative analysis of free-text responses to the question ‘how did breast cancer impact on your life?’ Results indicate that 15 months post-surgery, 15% of both groups of women commented on FCR but by 5 years, this proportion was much lower. Anxiety about clinical follow-up increased in the first 15 months for all women but was consistently higher among women in whom RT was omitted, suggesting that women who received RT may have felt additional ‘protection’ from RT which would mitigate against FCR.

Clearly any attempts to reduce the physical morbidity of oncologic treatment must not compromise women’s psychological health, and as such, closer scrutiny of the association between FCR and omission of RT is warranted. We undertook a cross-sectional, retrospective study of a large sample of women with early BC to explore the association between receipt of RT and FCR. Given that RT is the standard of care, we hypothesized that women who received RT would have lower levels of FCR than women for whom RT was omitted.

Methods

Recruitment procedure

Participants were women with early BC, diagnosed between 2011 and 2019 who were at least 12 months post-diagnosis, and had undergone breast conserving surgery with sentinel node biopsy and/or axillary dissection. Women were recruited from a large tertiary hospital breast service in metropolitan Melbourne, Australia.

Participants enrolled in PROSPECT (ANZ-1002) [11] were approached. Women assessed as eligible for de-escalation following local staging with MRI and surgery who omitted RT comprised Group A of our sample; women deemed ineligible for de-escalation post-MRI and surgery who underwent RT comprised Group B. A third cohort of usual care patients, Group C comprised patients who had not undergone MRI, underwent adjuvant RT, and were never approached for participation in PROSPECT but were approximately matched on age, tumour grade distribution, and tumour size to Groups A and B.

All women able to consent and participate in English were invited by letter or email to complete a study questionnaire, either online or on paper. Invitations were followed with a phone call 2 weeks later. Where contact was unsuccessful, a second invitation was sent. Women who agreed to participate by completing the questionnaire and providing written informed consent, could opt into a semi-structured interview. Women were selected for interview based on their scores on the FCRI-SF to provide a range of FCR experiences. Interviews continued until saturation (no new themes emerging from three consecutive interviews) was achieved. The study received ethics approval [HREC approval number: 2020.002].

Measures

Questionnaire

Study questionnaires collected data on educational and relationship status, language spoken at home, parity, medical comorbidities, and current or past treatment for anxiety or depression. Tumour characteristics, nodal stage, age, and time since diagnosis were collected from medical records.

Quantitative psychometric outcomes were assessed with robust, well-validated patient-reported outcome measures. Fear of cancer recurrence was assessed using the 9-item short-form (severity) subscale of the FCRI (FCRI-SF). Scores range from 0 to 36 and cut-offs are as described above [4, 5]. Negative affectivity, a general disposition to experience subjective distress [13], a potential confounder of FCR [14,15,16], was measured with the 10-item Neuroticism subscale of the International Personality Item Pool [17].

Semi-structured interview

The semi-structured interview was drafted by the first author, an academic psycho-oncologist with extensive clinical and research experience in BC and it was then refined in consultation with the multidisciplinary author group including another expert psycho-oncologist, specialist breast surgeon, breast radiologist, breast care nurse, and consumer with lived experience of BC. Semi-structured interviews were conducted telephonically by an experienced psychologist, and explored experience of BC treatment and the presence, nature, and extent of FCR (see Table 1). Interviews were recorded, electronically transcribed, and checked for accuracy.

Analyses

Quantitative data were analysed using SPSS version 28. Between group differences were analysed with non-parametric tests. Qualitative analysis, using Nvivo 12 software, followed the directed content analysis approach [18] informed by the literature, researcher expertise, and the study focus i.e. experiences of FCR, the extent to which treatment may have contributed to FCR and how women coped with FCR. Commonalities across existing FCR theory [19] and participant responses were used to identify preliminary coding categories. Two authors independently coded 20% of transcripts and developed the coding framework and potential themes, resolving disparities through discussion. The remaining interviews were then coded. Theme meanings were refined, and illustrative quotes identified.

Results

Study participation

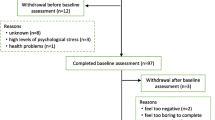

Of eligible women who had participated in PROSPECT, 189 who had omitted RT (Group A) and 176 who had received RT (Group B) were contacted for participation. Of women who had RT in usual care, 443 were approached. The final sample included 400 women comprising 125, 102, and 173 in Groups A, B, and C, respectively. Of these participants, 79, 68, and 101 women from Groups A, B, and C, respectively, consented to participate in a semi-structured interview. Interviews were conducted with 15 participants each from Groups A and B and 14 from Group C. Details of study participation are shown in Fig. 1.

Sample characteristics

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the sample are shown in Table 2. Most women were married (68.5%) and half had at least a secondary education (54.8%). Median age was 65 years, and median time since diagnosis was 4.4 years. There were no differences between groups in demographic and clinical groups except in tumour size. Participants in Group A had significantly smaller tumours (median = 10 mm) than their counterparts in Groups B and C (13 and 14 mm, respectively).

Fear of cancer recurrence: quantitative outcomes

Comparisons of FCR across groups using Mann–Whitney U test are shown in Table 3. Women who omitted RT following MRI (Group A) had significantly lower FCR compared to those who had RT, whether compared to participants who: received RT after MRI (Group B), received RT in usual care (Group C), or a combination of all participants who received RT (Group B plus C). Undergoing MRI with RT was not associated with significant differences in FCR as demonstrated in the comparison between women in Groups B and C, both of whom received RT. The inclusion of MRI i.e. participation in the PROSPECT trial (Groups A and B) was associated with lower FCR when compared with FCR in Group C.

A 3 × 3 χ2 test was used to compare categories of FCR severity between groups. As shown in Table 3, the proportions of women in each FCR category differed between the groups [X2 (4, n = 400) = 23.82, p < 0.001]. Specifically, the proportion of women who omitted RT (Group A) with normal levels of FCR (≤ 13) was significantly larger (62%) than the proportion of women with normal levels in the groups who received RT (Group B = 35%, Group C = 40%; p < 0.05). A significantly greater proportion of women in Group B (55%) than Group A (33%) scored 13–21 on the FCRI-SF (p < 0.05). This association between higher FCR and receipt of RT was shown again in the significantly larger proportion of women in Group C (16%) compared to Group A (6%) with scores ≥ 22 (p < 0.05). There were no other significant differences between groups.

A secondary analysis was conducted to eliminate any potential impact of disease severity on the analysis (see Appendix 1). All cases (n = 126) with any positive nodes, a Grade 3 tumour and tumour size > 20 mm were removed. The remaining sample comprised 274 women. There were no significant differences in age, time since diagnosis, parity, mental health treatment status or neuroticism between groups, and results were similar to the primary analysis. Women who omitted RT after MRI had significantly lower FCR than women who received RT after MRI (p = 0.008) and the combined group of women who received RT (p = 0.014). A significantly larger proportion of women in Group A (60%) had non-clinical levels of FCR (< 13) compared to Group B (34%), and a significantly smaller proportion of women in Group A (34%) had FCR levels warranting further clinical investigation (13–21) than in Group B (53%).

Fear of cancer recurrence: qualitative outcomes

Qualitative analysis yielded two themes. The first theme, ‘What I had was best’ is inductive and describes how women managed their FCR by having trust in their treatment and faith in the medical advice they received. The second theme, ‘Coping with FCR’, is deductive and comprises women’s descriptions of their FCR and coping as it related to their treatment. Theme descriptions and illustrative quotes for these themes are in Table 4.

Discussion

Avoiding over-treatment and minimizing treatment-related physical morbidity in lower risk BC is of growing importance but the effect of de-escalation on mental health, including FCR, must also be carefully considered. We sought to explore this association using a combination of validated psychometric assessment and qualitative interviews.

Our findings from this exploratory study provide preliminary but novel data that in a select but large sample of women with early BC, those who omit adjuvant RT after pre-operative MRI do not experience higher FCR than their counterparts who subsequently undergo RT, as well as women in usual care who do not have MRI but have RT. This finding was consistent whether treating FCR as a dimensional variable or using recommended cut-offs. A secondary analysis in which women with any positive nodes, a Grade 3 tumour or tumour size > 20 mm were excluded, yielded the same result. The results are made more compelling by the lack of significant differences between groups in time since diagnosis, age of participants, mental health treatment status, and neuroticism.

There are several possible explanations for our findings. It may be that RT is associated with higher FCR due to prolonging the treatment experience, with side effects serving as a reminder of cancer and/or being interpreted as signs of recurrence [20]. Certainly, interview data showed that many women did experience toxicities, and expressed a need for more education prior to RT. RT recipients consequently had more triggers for FCR and reported higher levels of FCR than women who omitted RT. Indeed, many women who omitted RT described very positive treatment experiences and BC having a minimal impact on their lives.

Another plausible explanation is that adjuvant treatment may be perceived as indicating more serious illness. Women who omitted RT in this study expressed relief that their cancer was ‘caught early,’ and others who received RT noted that adjuvant RT ‘compounded’ their illness experience. Those deemed ineligible for de-escalation may have interpreted ineligibility as signalling a significantly worse prognosis. The way in which news of ineligibility for de-escalation was communicated to patients is unknown, but this too may have contributed to FCR if conveyed as indicative of a poorer prognosis.

Another potential contributing factor explaining lower FCR in the cohort who omitted RT is the close monitoring and personalized care from dedicated trial staff in PROSPECT. This is supported by the qualitative data. Further, although women from all three groups reported high levels of trust in the recommendations of their treating team, the additional prognostic information afforded by MRI may have been protective for FCR by providing even more reassurance. Women who omitted RT did not perceive RT omission as under-treatment, rather as appropriate treatment.

Limitations and future research

Interpretation of these findings is limited by the cross-sectional, retrospective study design and recruitment from a single breast service. The groups studied were a priori clinically different in order to test the PROSPECT hypothesis. However, the absence of significant differences between the groups on age, time since diagnosis, neuroticism, and current or past mental health treatment is reassuring. It is possible that patients who declined participation in PROSPECT were more anxious and therefore disinterested in the option of treatment de-escalation. The exclusion of women not able to participate due to language barriers is recognized as a limitation.

There are several other psychological variables that could account for the differences reported here. Illness perceptions (personal ideas that patients have about their illness) may be important to consider. For instance, stronger beliefs about personal control over BC are related to fewer worries about whether cancer has been cured [21] and ideas about the chronicity, consequences, and emotional representation of BC have been associated with FCR [22]. Perceived risk of recurrence and appraisal of that risk are a key part of illness representations and are also associated with FCR [22, 23]. Future studies would benefit from including these variables. The way outcomes of investigations (e.g. pre-surgical MRI staging) and implications for treatment (e.g. eligibility for de-escalation) are communicated to patients and the meaning attributed to this information in terms of prognosis also warrants further scrutiny.

Nonetheless, the preliminary data presented here are novel and provide compelling grounds on which to include FCR in future studies of similar treatment de-escalation. If large-scale replication of PROSPECT confirms that omission of RT is associated with only a small rate of local recurrence in this select group, it may mean that QoL impacts, like FCR, become the deciding factor in determining whether or not to undergo RT.

Clinical implications

Within the limits of this study, omitting RT in this setting does not appear to be associated with higher FCR, and this is reassuring for clinicians and patients attempting to limit treatment burden through de-escalation. Our findings may be of particular relevance to women ≥ 70 years with oestrogen receptor-positive, clinically node-negative T1 tumours for whom omission of RT is guideline-concordant. Further, providing clear communication, fostering trust in the patient-doctor and reassuring patients that their treatment plan is personalized may facilitate lower FCR.

Conclusions

These findings provide preliminary but novel evidence that a select group of women with early BC who omit adjuvant RT after pre-operative MRI do not experience higher FCR than their counterparts who subsequently undergo RT, as well as women in usual care who do not have MRI but have RT. Future studies of de-escalation should include measurement of FCR and explore the role of illness perception variables and clinician communication in determining outcomes.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- BC:

-

Breast cancer

- FCR:

-

Fear of Cancer Recurrence

- FCRI-SF:

-

Fear of Cancer Recurrence-Short Form

- MRI:

-

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

- PRIME:

-

Post-operative Radiotherapy In Minimum-risk Elderly

- PROSPECT:

-

Post-operative Radiotherapy Omission in Selected Patients with Early breast Cancer Trial

- QoL:

-

Quality of Life

References

Sacchini V, Norton L (2022) Escalating de-escalation in breast cancer treatment. Breast Cancer Res Treat 195(2):85–90

Lebel S et al (2016) From normal response to clinical problem: definition and clinical features of fear of cancer recurrence. Support Care Cancer 24(8):3265–3268

Luigjes-Huizer YL et al (2022) What is the prevalence of fear of cancer recurrence in cancer survivors and patients? a systematic review and individual participant data meta-analysis. Psychooncology 31(6):879–892

Simard S, Savard J (2009) Fear of cancer recurrence inventory: development and initial validation of a multidimensional measure of fear of cancer recurrence. Support Care Cancer 17(3):241–251

Simard S, Savard J (2015) Screening and comorbidity of clinical levels of fear of cancer recurrence. J Cancer Surviv 9(3):481–491

Williams JTW, Pearce A, Smith A (2021) A systematic review of fear of cancer recurrence related healthcare use and intervention cost-effectiveness. Psychooncology 30(8):1185–1195

Galica J et al (2021) Examining predictors of fear of cancer recurrence using Leventhal’s Commonsense model: distinct implications for oncology nurses. Cancer Nurs 44(1):3–12

Zheng M et al (2022) The correlation between radiotherapy and patients’ fear of cancer recurrence: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Hosp Palliat Nurs 24(3):186–198

Darby S, McGale P, Correa C (2011) Early Breast Cancer Trialists’ Collaborative Group (EBCTCG). Effect of radiotherapy after breast-conserving surgery on 10-year recurrence and 15-year breast cancer death: Meta-analysis of individual patient data for 10,801 women in 17 randomised trials. Lancet. 378:1717–1716

Speers C, Pierce L (2016) Postoperative radiotherapy after breast-conserving surgery for early-stage breast cancer: a review. JAMA Oncol 1:1075–1082

Mann B et al (2022) Primary results of ANZ 1002 Post-operative radiotherapy omission in selected patients with early breast cancer trial (PROSPECT) following pre-operative breast MRI. J Clin Oncol 40(16):572

Williams LJ et al (2011) A randomised controlled trial of post-operative radiotherapy following breast-conserving surgery in a minimum-risk population. Quality of life at 5 years in the PRIME trial. Health Technol Assess. https://doi.org/10.3310/hta15120

Watson D, Pennebaker JW (1989) Health complaints, stress and distress: exploring the central role of negative affectivity. Psychol Rev 96(2):234–254

Aarstad AKH et al (2011) Distress, quality of life, neuroticism and psychological coping are related in head and neck cancer patients during follow-up. Acta Oncol (Stockholm, Sweden) 50(3):390

Husson O et al (2017) Personality traits and health-related quality of life among adolescent and young adult cancer patients: the role of psychological distress. J Adolesc Young Adult Oncol 6(2):358

Ng DWL et al (2019) Fear of cancer recurrence among Chinese cancer survivors: prevalence and associations with metacognition and neuroticism. Psychooncology 28(6):1243–1251

Goldberg LR (1999) A broad-bandwidth, public domain, personality inventory measuring the lower-level facets of several five-factor models. In: Mervielde I et al (eds) Personality Psychology in Europe. Tilburg University Press, Tilburg, The Netherlands, pp 7–28

Hsieh H-F, Shannon SE (2005) Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res 15(9):1277–1288

Simonelli LE, Siegel SD, Duffy NM (2017) Fear of cancer recurrence: a theoretical review and its relevance for clinical presentation and management. Psychooncology 26(10):1444–1454

Fardell JE et al (2016) Fear of cancer recurrence: a theoretical review and novel cognitive processing formulation. J Cancer Surviv 10(4):663–673

Henselmans I et al (2010) Identification and prediction of distress trajectories in the 1st year after a breast cancer diagnosis. Health Psychol 29:160–168

Freeman-Gibb LA et al (2017) The relationship between illness representations, risk perception and fear of cancer recurrence in breast cancer survivors. Psychooncology 26(9):1270–1277

Ankersmid JW et al (2022) Relations between recurrence risk perceptions and fear of cancer recurrence in breast cancer survivors. Breast Cancer Res Treat 195(2):117–125

Acknowledgements

Michelle Sinclair is funded by a Fellowship from Breast Cancer Trials. The authors acknowledge the Psycho-oncology Co-operative Research Group (PoCoG) who supported the development of this research. The Psycho-oncology Co-operative Research Group is funded by Cancer Australia through their Support for Clinical Trials Funding Scheme. The authors acknowledge the contribution of Breast Cancer Trials in funding PROSPECT, without which the current work would not have been possible. Breast Cancer Trials receives funding from Cancer Australia.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions. Breast Cancer Trials, Fellowship, Michelle Sinclair

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

LS, BM, PB, and AR contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation and data collection were performed by MS with assistance from JH and AP. Data analyses were performed by LS, MS, and PB. The first draft of the manuscript was written by LS and MS. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors have no competing interests to declare.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was granted by The Royal Melbourne Hospital HREC approval number: 2020.002.

Consent to participate

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Consent to publish

The authors affirm that participants provided informed consent for publication of these data.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Stafford, L., Sinclair, M., Butow, P. et al. Is de-escalation of treatment by omission of radiotherapy associated with fear of cancer recurrence in women with early breast cancer? An exploratory study. Breast Cancer Res Treat 201, 367–376 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-023-07039-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-023-07039-2