Abstract

Purpose

The early months of the COVID-19 pandemic led to reduced cancer screenings and delayed cancer surgeries. We used insurance claims data to understand how breast cancer incidence and treatment after diagnosis changed nationwide over the course of the pandemic.

Methods

Using the Optum Research Database from January 2017 to March 2021, including approximately 19 million US adults with commercial health insurance, we identified new breast cancer diagnoses and first treatment after diagnosis. We compared breast cancer incidence and proportion of newly diagnosed patients receiving pre-operative systemic therapy pre-COVID, in the first 2 months of the COVID pandemic and in the later part of the COVID pandemic.

Results

Average monthly breast cancer incidence was 19.3 (95% CI 19.1–19.5) cases per 100,000 women and men pre-COVID, 11.6 (95% CI 10.8–12.4) per 100,000 in April–May 2020, and 19.7 (95% CI 19.3–20.1) per 100,000 in June 2020–February 2021. Use of pre-operative systemic therapy was 12.0% (11.7–12.4) pre-COVID, 37.7% (34.9–40.7) for patients diagnosed March–April 2020, and 14.8% (14.0–15.7) for patients diagnosed May 2020–January 2021. The changes in breast cancer incidence across the pandemic did not vary by demographic factors. Use of pre-operative systemic therapy across the pandemic varied by geographic region, but not by area socioeconomic deprivation or race/ethnicity.

Conclusion

In this US-insured population, the dramatic changes in breast cancer incidence and the use of pre-operative systemic therapy experienced in the first 2 months of the pandemic did not persist, although a modest change in the initial management of breast cancer continued.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The early months of the COVID-19 pandemic caused major disruption to health care delivery, in both cancer diagnosis, including lower rates of screening [1,2,3,4,5,6,7], and cancer treatment, including widely reported of delays in therapy [5, 8, 9]. Many hospitals postponed non-emergent surgeries, including cancer surgeries, and in the case of breast cancer, guidelines recommended considering pre-operative systemic therapy if surgery might not be readily available [10,11,12]. After the initial turmoil, most reports going beyond the first few months of the pandemic have shown at least some degree of recovery of screening toward the pre-pandemic levels [1,2,3, 7]. However, it is not yet known whether and to what extent changes in the management of breast cancer that occurred during the early period of the pandemic may have continued.

The impact of the pandemic, including on health care delivery, has varied greatly across the United States (US) and the world. Different regions of the US have been more severely affected by the pandemic at different times [13], and COVID-19 incidence and outcomes have varied by demographic factors, such as race/ethnicity [13,14,15,16] and socioeconomic status [15, 16]. The initial impact of the pandemic on cancer screening also varied across geographic regions [1]. Whether its impact on the treatment of breast cancer varied by geographic regions or other demographic factors is not yet known.

In this study, we used data from the Optum database of insurance claims and electronic health records for US individuals through March 2021 to assess the incidence of breast cancer diagnosis and first treatment after diagnosis before the pandemic, during the first 2 months of the pandemic when disruption in cancer screening and care delivery were most pronounced [1, 17], and during the later months of the pandemic. Moreover, we sought to understand whether the changes observed over the course of the pandemic in breast cancer incidence and treatment varied by geographic region, local area socioeconomic deprivation, or race/ethnicity.

Methods

Data source and study sample

We analyzed de-identified data from the Optum Research Database, consisting of private insurance claims linked to electronic health record information from US individuals, from January 2017 through March 2021. Our study sample included individuals at least 18 years of age, with at least 6 months of electronic health record information prior to and at least 30 days of enrollment in an Optum health plan after their first recorded diagnostic or procedure claims code during the study interval and with no breast cancer diagnosis prior to their entry into the cohort.

Inference of breast cancer incidence and first treatment after diagnosis

To identify people who were newly diagnosed with invasive breast cancer, we selected individuals who had a first-ever International Classification of Disease (ICD) code for invasive breast cancer (ICD-10 C50; ICD-9 174 and 175) and a breast cancer diagnostic procedure (biopsy or fine needle aspiration) Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) code within ± 30 days of that ICD code. We did not exclude male breast cancer. To select early-stage breast cancers, we excluded individuals with a secondary malignant neoplasm diagnosis code. We set the date of diagnosis as the date of the breast cancer diagnostic procedure code. To identify first treatment after breast cancer diagnosis, we selected those individuals with a new breast cancer diagnosis who had at least 60-day enrollment in an Optum health plan after diagnosis date. We then recorded whether a medication code for an endocrine drug (tamoxifen, letrozole, anastrozole, or exemestane), medication code for a chemotherapy drug, or CPT code for a breast surgical procedure appeared first within those 60 days. If none of these occurred within 60 days, we classified these patients as not having received treatment during follow-up.

Statistical analysis

We defined three time periods corresponding to the pre-COVID period, COVID period 1 representing the first 2 months of the pandemic, and COVID period 2 representing the subsequent months of the pandemic. For breast cancer incidence analyses, we defined COVID period 1 as diagnosis dates in April and May 2020, while for the first-treatment analyses, we defined it as diagnosis dates in March and April 2020, reflecting the delay between diagnosis and treatment. COVID period 2 ended in February 2021 for breast cancer incidence analyses and in January 2021 for first-treatment analyses, due to the requirement for longer follow-up to assess first treatment. We used Chi-squared tests to compare proportions other than the proportion of patients receiving pre-operative systemic therapy, which was tested in the logistic regression model. We used a univariate Poisson model including COVID period to calculate monthly breast cancer incidence and 95% confidence intervals; to assess whether incidence differed across the three COVID periods, we reported the P value of the COVID period term. We used a univariate logistic regression model including COVID period to estimate the proportion of patients with a new diagnosis of breast cancer receiving pre-operative systemic therapy (combining endocrine therapy and chemotherapy) and 95% confidence intervals; to assess whether this proportion differed across the three COVID periods, we reported the P value of the COVID period term.

For analyses of the impact of geographic region, Area Deprivation Index (ADI) [18], and race/ethnicity on breast cancer incidence and treatment across the pandemic, we note that Optum data are available as two unlinked databases, one with five-digit zip code information and a separate one with race/ethnicity information from the electronic health record. Therefore, we assessed in different datasets using the separate models, adding main effect and the interaction term of interest, to test whether the change in breast cancer incidence or in first treatment across time periods varied by geographic region, by ADI, and by race/ethnicity, reporting the P value of the interaction term between COVID period and each covariate. We defined geographic region according to the nine Census Bureau-designated divisions. ADI was derived from areal-level income, education, employment, and housing conditions and linked to five-digit zip code; we divided our study sample into those living in less-deprived areas (0–80th ADI percentile) and those living in most deprived areas (over 80th ADI percentile). All analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc.).

Results

Breast cancer incidence across the COVID-19 pandemic

Between January 2017 and February 2021, Optum included 19,329,646 unique women and men who met criteria for inclusion in our cohort. Average monthly breast cancer incidence (including both females and males) prior to the onset of COVID was 19.3 (95% CI 19.1–19.5) cases per 100,000 individuals (Fig. 1). In April and May 2020 (COVID period 1), breast cancer incidence dropped by 40% to 11.6 (95% CI 10.8–12.4) cases per 100,000 (P < 0.001 compared to pre-COVID), and from June 2020 to February 2021 (COVID period 2), it recovered to 19.7 (95% CI 19.3–20.1) cases per 100,000 (P = 0.10 compared to pre-COVID).

Monthly breast cancer incidence per 100,000 people from 2017 to 2021. Month of breast cancer diagnosis is shown on the x-axis. The pre-COVID period extends from January 2017 through March 2020, COVID period 1 from April 2020 through May 2020, and COVID period 2 from June 2020 through February 2021. Across the population, breast cancer incidence dropped precipitously in COVID period 1 and recovered to slightly above-normal levels in COVID period 2

First treatment for breast cancer across the COVID-19 pandemic

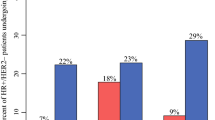

Between January 2017 and January 2021, we identified 34,893 women and men who met criteria for a new breast cancer diagnosis and who received a first treatment (either surgery, endocrine therapy, or chemotherapy) during the first two months after diagnosis. Prior to the onset of COVID, 12.0% (95% CI 11.7–12.4) of individuals were prescribed pre-operative systemic therapy, increasing to 37.7% (95% CI 34.9–40.7) during COVID period 1 (P < 0.001 compared to pre-COVID) and declining, yet remaining above pre-COVID level, to 14.8% (95% CI 14.0–15.7) during COVID period 2 (P < 0.001 compared to pre-COVID) (Fig. 2). Much of this change was due to the use of pre-operative endocrine therapy, which comprised 5.0% of first therapy pre-COVID, 26.8% during COVID period 1 (P < 0.001 compared to pre-COVID), and 6.2% during COVID period 2 (P < 0.001 compared to pre-COVID) (Fig. 2).

First treatment after breast cancer diagnosis from 2017 to 2021. Month of breast cancer diagnosis is shown on the x-axis, with first treatment occurring within first 2 months after diagnosis. The pre-COVID period extends from January 2017 through February 2020, COVID period 1 from March 2020 through April 2020, and COVID period 2 from May 2020 through January 2021. Across the population, use of pre-operative systemic therapy, and particularly endocrine therapy, increased acutely in COVID period 1 and recovered, although not fully to pre-pandemic levels, in COVID period 2

We identified 8,099 individuals with newly diagnosed breast cancer who did not receive a first treatment during the first 2 months after diagnosis. The proportion of individuals who had no treatment within 2 months of diagnosis was modestly less during the early pandemic: 18.9% pre-COVID; 15.7% during COVID period 1 (Chi-squared P = 0.005 compared to pre-COVID); and 19.1% during COVID period 2 (P = 0.74 compared to pre-COVID).

We next asked whether those patients who were prescribed pre-operative endocrine therapy during the first 2 months of the pandemic (COVID period 1) were more likely to be prescribed it for a short period of time as compared to other patients in the cohort. In COVID period 1, 65.9% of patients who were prescribed pre-operative endocrine therapy went onto surgery in less than 2 months, as compared to 32.2% in the pre-COVID period (P < 0.001 as compared to COVID period 1) and 30.2% in COVID period 2 (P < 0.001 as compared to COVID period 1).

Variability across the United States in breast cancer diagnosis and treatment during COVID-19

We next investigated whether the reduction in breast cancer incidence during the first 2 months of the pandemic or the recovery in breast cancer incidence thereafter differed by geographic region, ADI, or race/ethnicity (Table 1; Fig. 3). We found no significant differences by these factors (interaction term with COVID period P = 0.11 for geographic region, P = 0.61 for ADI, and P = 0.29 for race/ethnicity). All races/ethnicities experienced a recovery in breast cancer incidence in COVID period 2 to a higher incidence compared to pre-COVID, with the exception of the Hispanic population (P = 0.03 recovery relative to the non-Hispanic White population, not significant when adjusting for multiple hypothesis testing).

Breast cancer incidence across the COVID-19 pandemic by area deprivation and race/ethnicity. a Average monthly breast cancer incidence across the pandemic by area deprivation. Less-deprived areas correspond to Area Deprivation Index percentiles between 0 and 80%, and most deprived corresponds to Area Deprivation Index percentiles over 80%. b Average monthly breast cancer incidence across the pandemic by race/ethnicity. 95% confidence intervals are shown. Pre-COVID is January 2017 through March 2020, COVID period 1 April 2020 through May 2020, and COVID period 2 June 2020 through February 2021. There were no significant differences in the reduction in breast cancer incidence in COVID period 1 and its recovery in COVID period 2 across Area Deprivation Index or race/ethnicity

The use of pre-operative systemic therapy across COVID period differed significantly by geographic region (P = 0.01), but not by ADI (P = 0.32) nor by race/ethnicity (P = 0.58) (Table 1). During COVID period 1, the Mountain region saw the least increase in pre-operative systemic therapy with a 2.7-fold odds ratio from 12% (10.8–13.3) to 27% (19.9–35.6), while the Mid-Atlantic region saw the greatest increase (8.4-fold odds ratio) from 11.5% (10.2–12.9) to 52% (40.8–63.0).

Discussion

In this study of insurance claims and electronic health data from 19 million US individuals with commercial health insurance, we observed a 40% reduction of breast cancer incidence during the first 2 months of the pandemic, recovering to baseline or slightly above thereafter. We also observed a 4.4-fold odds ratio in the use of pre-operative systemic therapy, especially endocrine therapy, as first treatment after breast cancer diagnosis during the first 2 months of the pandemic; in the later stages of the pandemic, the use of pre-operative systemic therapy remained modestly elevated (1.3-fold odds ratio) compared to prior to the pandemic. We did not observe any differences in the change in breast cancer incidence over the course of the pandemic based on geographic region, area socioeconomic deprivation, or race/ethnicity. Increased use of pre-operative systemic therapy varied by geographic region.

Prior studies have examined breast cancer screening during the pandemic [1,2,3,4,5,6,7], but there are relatively few reports thus far on changes in breast cancer diagnosis and to our knowledge the current study represents the report with the most recent data. One study of a single health care system found that the percentage of mammograms leading to a breast cancer diagnosis was higher during the pandemic [2], highlighting the likely reluctance of asymptomatic women to seek non-urgent care. As expected, we found that breast cancer diagnoses declined sharply in the first 2 months of the pandemic, although less severely than did screening in another population with commercial insurance [1]. We also found that there was a trend toward higher breast cancer incidence after the first 2 months of the pandemic, suggesting that many of the missed diagnoses in the first 2 months were captured subsequently.

We found no differences in breast cancer incidence by race/ethnicity, area socioeconomic deprivation, or geographic region. Some previous studies have similarly reported no difference in breast cancer screening changes during the pandemic by race/ethnicity [3, 19], while one study showed greater declines in non-White races/ethnicities, especially Hispanic women [20]. Part of the discrepancy in results is likely explained by different patient populations. There may indeed be less disparity by demographic factors in a commercially insured population as studied here, where disparity in access is somewhat mitigated. The study of a state-wide community health care system that found variability in the decline in breast cancer screening by race/ethnicity also reported that the largest reductions in screening were experienced by people with Medicaid or no insurance [20], populations not captured in this study. Similarly, while in this study sample, complete recovery of breast cancer incidence was observed after the first 2 months, other studies that included individuals without commercial insurance have identified groups that may not have fully recovered, including women of any race/ethnicity in a study of an urban safety-net hospital [21] and Asian and Hispanic women in the Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium [7]. This variance in results underscores the importance of studying multiple types of populations to identify the optimal targets to improve disparities in access and outcomes during the COVID-19 pandemic.

In examining treatment after breast cancer diagnosis, we found remarkably high uptake of pre-operative systemic therapy in the early months of the pandemic, consistent with survey data from this time period indicating increased willingness among physicians to use neoadjuvant endocrine therapy [22]; this use was more likely to be short term than in other periods and likely intended to tide patients over until surgery. Across this large national population, the uptake was similar to that reported in a study of a single academic center [23], suggesting that the patterns observed, while variable across geographic regions, may have occurred across multiple practice types. While longer than 8 weeks from diagnosis to first treatment is generally considered treatment delay [24, 25], in the early months of the pandemic, the proportion of patients with newly diagnosed breast cancer who did not receive any treatment in the first 2 months was, somewhat counterintuitively, reduced compared to the pre-pandemic or later-pandemic periods. This may reflect the widespread adoption of short-term endocrine therapy to protect against pandemic-induced surgery delays. Whether this practice pattern may translate into increased use of pre-operative systemic therapy going forward is not known, but we did note that the use of pre-operative systemic therapy remained modestly elevated in the later pandemic as compared to the pre-pandemic period. Further follow-up will be required to determine whether this change in practice may persist, especially as it remains possible that stage shift during the later pandemic because of the missed diagnoses in the early pandemic also increased the use of pre-operative systemic therapy.

This study has some limitations. First, the study sample included only individuals with commercial insurance, and other datasets are necessary to study disparities that may exist in access to cancer diagnosis and care during the COVID-19 pandemic. Second, we do not have information on tumor stage or other characteristics at diagnosis, limiting information on how choice of first treatment may have been dictated by a change in these variables during the pandemic. Similarly, we do not have information on health care system factors (for example, academic versus community practice) that may have led to variability in practice patterns during the pandemic. These limitations are offset by the large national sample, including multiple geographic regions and practice types.

As we enter a new phase of the pandemic, continued study is necessary to determine what may be the long-lasting impacts on the COVID-19 pandemic on breast cancer diagnosis and care. In this study of commercially insured US individuals, we observed a strong and persistent recovery in breast cancer incidence, but continued elevation in the use of pre-operative systemic therapy long after breast cancer incidence returned to baseline. This study offers a nationwide, broadly generalizable perspective on the care of insured patients with newly diagnosed breast cancer during the course of the pandemic to date, which may inform planning by health care systems and policy makers.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from Optum Clinformatics but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for the current study, and so are not publicly available. Data are however available from the authors upon reasonable request and with permission of Optum Clinformatics.

References

Chen RC, Haynes K, Du S, Barron J, Katz AJ (2021) Association of cancer screening deficit in the United States with the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Oncol 7(6):878–884. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaoncol.2021.0884

Bakouny Z, Paciotti M, Schmidt AL, Lipsitz SR, Choueiri TK, Trinh QD (2021) Cancer screening tests and cancer diagnoses during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Oncol 7(3):458–460. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaoncol.2020.7600

Nyante SJ, Benefield TS, Kuzmiak CM, Earnhardt K, Pritchard M, Henderson LM (2021) Population-level impact of coronavirus disease 2019 on breast cancer screening and diagnostic procedures. Cancer 127(12):2111–2121. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.33460

London JW, Fazio-Eynullayeva E, Palchuk MB, Sankey P, McNair C (2020) Effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on cancer-related patient encounters. JCO Clin Cancer Inform 4:657–665. https://doi.org/10.1200/CCI.20.00068

Yin K, Singh P, Drohan B, Hughes KS (2020) Breast imaging, breast surgery, and cancer genetics in the age of COVID-19. Cancer 126(20):4466–4472. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.33113

Patt D, Gordan L, Diaz M, Okon T, Grady L, Harmison M et al (2020) Impact of COVID-19 on cancer care: how the pandemic is delaying cancer diagnosis and treatment for American seniors. JCO Clin Cancer Inform 4:1059–1071. https://doi.org/10.1200/CCI.20.00134

Sprague BL, Lowry KP, Miglioretti DL, Alsheik N, Bowles EJA, Tosteson ANA et al (2021) Changes in mammography use by women’s characteristics during the first 5 months of the COVID-19 pandemic. J Natl Cancer Inst 113(9):1161–1167. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/djab045

Satish T, Raghunathan R, Prigoff JG, Wright JD, Hillyer GA, Trivedi MS et al (2021) Care delivery impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on breast cancer care. JCO Oncol Pract 17(8):e1215–e1224. https://doi.org/10.1200/OP.20.01062

Papautsky EL, Hamlish T (2020) Patient-reported treatment delays in breast cancer care during the COVID-19 pandemic. Breast Cancer Res Treat 184(1):249–254. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-020-05828-7

Sheng JY, Santa-Maria CA, Mangini N, Norman H, Couzi R, Nunes R et al (2020) Management of breast cancer during the COVID-19 pandemic: a stage- and subtype-specific approach. JCO Oncol Pract 16(10):665–674. https://doi.org/10.1200/OP.20.00364

Dietz JR, Moran MS, Isakoff SJ, Kurtzman SH, Willey SC, Burstein HJ et al (2020) Recommendations for prioritization, treatment, and triage of breast cancer patients during the COVID-19 pandemic. The COVID-19 pandemic breast cancer consortium. Breast Cancer Res Treat 181(3):487–97. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-020-05644-z

Curigliano G, Cardoso MJ, Poortmans P, Gentilini O, Pravettoni G, Mazzocco K et al (2020) Recommendations for triage, prioritization and treatment of breast cancer patients during the COVID-19 pandemic. Breast 52:8–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.breast.2020.04.006

Gold JAW, Rossen LM, Ahmad FB, Sutton P, Li Z, Salvatore PP et al (2020) Race, ethnicity, and age trends in persons who died from COVID-19 - United States, may-august 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 69(42):1517–1521. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6942e1

Karaca-Mandic P, Georgiou A, Sen S (2021) Assessment of COVID-19 hospitalizations by race/ethnicity in 12 states. JAMA Intern Med 181(1):131–134. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.3857

Quan D, Luna Wong L, Shallal A, Madan R, Hamdan A, Ahdi H et al (2021) Impact of race and socioeconomic status on outcomes in patients hospitalized with COVID-19. J Gen Intern Med 36(5):1302–1309. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-020-06527-1

Price-Haywood EG, Burton J, Fort D, Seoane L (2020) Hospitalization and mortality among black patients and white patients with Covid-19. N Engl J Med 382(26):2534–2543. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMsa2011686

Labaki C, Bakouny Z, Schmidt A, Lipsitz SR, Rebbeck TR, Trinh QD et al (2021) Recovery of cancer screening tests and possible associated disparities after the first peak of the COVID-19 pandemic. Cancer Cell 39(8):1042–1044. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccell.2021.06.019

Columbia Data Platform Demo (2021) Area Deprivation Index (ADI) (v1.0). Redivis. (Dataset). https://redivis.com/datasets/axrk-7jx8wdwc2?v=1.0

Marcondes FO, Cheng D, Warner ET, Kamran SC, Haas JS (2021) The trajectory of racial/ethnic disparities in the use of cancer screening before and during the COVID-19 pandemic: a large U.S. academic center analysis. Prev Med 151:1640. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2021.106640

Amram O, Robison J, Amiri S, Pflugeisen B, Roll J, Monsivais P (2021) Socioeconomic and racial inequities in breast cancer screening during the COVID-19 pandemic in Washington State. JAMA Netw Open 4(5):e2110946. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.10946

Velazquez AI, Hayward JH, Gregory B, Dixit N (2021) Trends in breast cancer screening in a safety-net hospital during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Netw Open 4(8):e2119929. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.19929

Park KU, Gregory M, Bazan J, Lustberg M, Rosenberg S, Blinder V et al (2021) Neoadjuvant endocrine therapy use in early stage breast cancer during the covid-19 pandemic. Breast Cancer Res Treat 188(1):249–258. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-021-06153-3

Hawrot K, Shulman LN, Bleiweiss IJ, Wilkie EJ, Frosch ZAK, Jankowitz RC et al (2021) Time to treatment initiation for breast cancer during the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic. JCO Oncol Pract 17(9):534–540. https://doi.org/10.1200/OP.20.00807

Hanna TP, King WD, Thibodeau S, Jalink M, Paulin GA, Harvey-Jones E et al (2020) Mortality due to cancer treatment delay: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 371:m4087. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.m4087

Khorana AA, Tullio K, Elson P, Pennell NA, Grobmyer SR, Kalady MF et al (2019) Time to initial cancer treatment in the United States and association with survival over time: an observational study. PLoS ONE 14(3):e0213209. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0213209

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge Natasha Purington and Summer Han for their feedback on the statistical analysis of this manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Breast Cancer Research Foundation (AWK); the Suzanne Pride Bryan Fund for Breast Cancer Research (AWK); the Jan Weimer Faculty Chair in Breast Oncology (AWK); and the BRCA Foundation (AWK).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JC-J, MS, MB, and AK conceived and designed the study. Data collection and analysis were performed by LX and ML. Data interpretation was performed by JC-J, MS, EJ, MB, and AK. The first draft of the manuscript was written by JC-J and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

Dr Caswell-Jin receives research support to her institution from QED Therapeutics and Effector Therapeutics. Dr Shafaee receives research support to her institution from Mirati Therapeutics. The remaining authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval

This study was performed on de-identified data and thus no ethical approval was required.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Caswell-Jin, J.L., Shafaee, M.N., Xiao, L. et al. Breast cancer diagnosis and treatment during the COVID-19 pandemic in a nationwide, insured population. Breast Cancer Res Treat 194, 475–482 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-022-06634-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-022-06634-z