Abstract

Purpose

Despite the increasing use of adjuvant bone-modifying agents (BMAs) such as zoledronate and clodronate in the treatment of patients with early stage breast cancer (EBC), little is known about real world practice patterns. A physician survey was performed to address this deficit and determine interest in clinical trials of alternative strategies for BMA administration.

Methods

Canadian oncologists treating patients with EBC were surveyed via an anonymized online survey. The survey collected information on: physician demographics, knowledge and interpretation of adjuvant bisphosphonate guidelines, and real world prescribing practices. Questions also determined thoughts around the design of future adjuvant BMA trials.

Results

Of 127 surveyed physicians, 53 eligible invitees responded (response rate 42%). The majority of physicians are offering high-risk postmenopausal patients adjuvant BMAs. The most common BMA regimen was adjuvant zoledronate (45/53, 85%) every 6 months for 3 years. Concerns around toxicities and repeated visits to the cancer centre were perceived as the greatest barriers to adjuvant bisphosphonate use. Respondents were interested in future trials of de-escalation of BMAs comparing a single infusion of zoledronate vs. 6-monthly zoledronate for 3 years. The most favoured primary endpoints for such a trial included disease recurrence and fragility fracture rates.

Conclusion

Questions around optimal use of adjuvant bisphosphonates in patients with EBC still exist. There is interest among physicians in performing trials of de-escalation of these agents. The results of this survey will assist in designing pragmatic clinical trials to address this question.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Patients with early stage breast cancer (EBC) are at an increased risk of skeletal morbidity, reflected through fragility fractures, and an increased risk of developing bone metastases. The results of trials evaluating bone-modifying agents such as bisphosphonates and the results of a subsequent meta-analysis demonstrated that in post-menopausal women, or premenopausal patients receiving ovarian suppression, adjuvant bisphosphonates reduced the rate of distant breast cancer recurrence, recurrence in the bone, and improved breast cancer survival [1]. Ultimately, national and international evidence-based treatment guidelines have recommended that bisphosphonates (usually zoledronate or clodronate) be considered as adjuvant therapy for postmenopausal patients with higher risk breast cancer who are deemed candidates for adjuvant systemic therapy [1, 2]. Another recent guideline has recommended that adjuvant bisphosphonates be part of treatment for postmenopausal patients (naturally or induced), who are treated with chemotherapy, and/or have a greater than 12% 10-year risk of breast cancer death [3].

Despite these guidelines, the uptake of these recommendations has been variable. At the 2019 St Gallen Consensus Conference, only 42.6% of the international panel reported routine use of BMAs in patients with EBC [4], despite the previous conference “strongly endorsing” their use to improve disease outcomes in post-menopausal women with breast cancer [5]. Similarly, data obtained from Cancer Care Ontario (14/April/2020, personal communication Fatuma for the Data Disclosure Team, CCO) shows that only about 20% of eligible breast cancer patients in Ontario are receiving adjuvant bisphosphonate therapy [6].

Given the variable clinical uptake of these agents, a survey targeting physicians treating patients with EBC was conducted to identify knowledge and interpretation of adjuvant bisphosphonate treatment guidelines, and current bisphosphonate prescribing practices. In addition, as the CCO-ASCO Practice Guideline, ‘Bottom line recommendations’ states, “More research is recommended comparing different bone-modifying agents, doses, dosing intervals, and durations” [2], we asked physicians what future adjuvant BMA trials they felt would be worth performing. The information obtained from the survey will be used to learn more about real world practice, explore unanswered questions and assist in the design of clinical trials to address these questions.

Materials and methods

Study population

Health care providers (medical oncologists, surgical oncologists, oncology nurse practitioners) involved in the systemic treatment of patients with EBC, across all Canadian provinces, were the target population.

Study outcomes

The information sought in the survey aimed to obtain insights on real world adjuvant BMA prescribing practices, such as the proportion of health care providers who were prescribing these agents, and how they identified suitable patients for these therapies. In addition, we wished to determine health care provider interest in the design of future adjuvant BMA studies and seek feedback as to which endpoints are most relevant for such studies.

Survey development

The survey was designed by a multidisciplinary team with established expertise in survey development and performance. The survey was pilot tested on two oncologists (MC, SMG) before launch. The first section of the survey was devised to collect basic demographic information (e.g. profession [medical oncologist, surgical oncologist etc.], duration in practice). The second section aimed to determine physician knowledge of current clinical practice guidelines on the use of adjuvant BMAs (e.g. guidance available, eligible patients, treatment benefits). The third section was designed to clarify physician interpretation and application of clinical guidelines (e.g. definitions of eligible patients), and real-world prescribing patterns (e.g. percentage of patients offered treatment, patient characteristics [i.e. menopausal status, chemotherapy use], agent/schedule used). The final section explored physician ideas for the design of future trials of BMA use, including preferred endpoints, agents, and dosing schedule.

Survey implementation

Potential participants were contacted using a collection of publicly available email addresses accessible to the investigators that has been used in previous surveys of this type [7]. This includes members of the Canadian Association of Medical Oncologists. The oncology nurse practitioners were contacted through the Canadian Association of Oncology Nurses (CANO) website. The online survey was run using Microsoft Forms from the research coordinator’s secure account within the Ottawa Hospital Research Institute. Physicians were sent an invitation to complete the survey, a link to the electronic survey, and a study information sheet. Another reminder notice was sent to participants two weeks later. The survey was approved by the Ontario Cancer Research Ethics Board (OCREB). After the survey had started, we received approval to add a question asking physicians specifically what 10-year mortality rate they would use to consider adjuvant BMA treatment for. This was based on the ESMO guideline that recommended adjuvant bisphosphonate use for patients treated with chemotherapy, and/or have a greater than 12% 10-year risk of breast cancer death [3, 8].

Data analysis

All data was summarized descriptively. The frequency of each answer choice was tabulated as a proportion of the total number of respondents for that category. Data were analyzed using Excel.

Results

Physician demographics

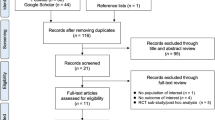

Between October 19 and November 13, 2020, the electronic survey was sent out to 146 physicians; 19 invitees were not eligible (maternity leave, no longer treating breast cancer, retired, out of office or e-mail address invalid). A total of 52 eligible invitees responded for a physician response rate of 41% (52/127). Unfortunately, the response rate could not be calculated for the nurse practitioners, as the CANO website sent the survey to all oncology nurses in Canada with no information on the number who are either nurse practitioners or who treat breast cancer. Of the total eligible respondents (n = 53), the majority were medical oncologists (47, 88.7%) (Table 1). Respondents spanned a broad range of clinical practice experience, including 28.3% with less than 5 years and 15.1% with over 20 years in independent practice.

Health care provider awareness of practice guidelines

All 53 respondents were aware of at least one clinical practice guideline recommending the use of adjuvant bisphosphonate therapy in patients with EBC. With respect to the individual guideline groups the most common were for; Cancer Care Ontario and American society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO-CCO) (49/53, 94.2%), European society for Medical Oncology ESMO (22/53, 42.3%), and St Gallen (14/53, 26.9%). From these different sources, physicians were aware that guidelines recommended adjuvant bisphosphonate therapy be considered either for “patients with natural or treatment induced menopause, and high-risk disease” (34/53, 64.2%) or “EBC with natural or treatment induced menopause” (13/53, 24.5%).

With respect to the populations who benefit from adjuvant bisphosphonate therapy reported in the EBCTCG meta-analyses, the most common responses were for; reduced risk of disease recurrence/relapse in the bone (48/53, 90.6%), increased breast cancer specific survival (30/53, 56.6%) and increased overall survival (23/53, 43.4%). When physicians were asked about patient populations who benefited from adjuvant bisphosphonate in EBCTCG study, 35/53 (67.3%) mentioned only postmenopausal patients benefited and 15/52 (28.2%) mentioned that only postmenopausal patients with high risk disease benefited.

Physician personal practice with respect to adjuvant bisphosphonates

The majority of respondents (41/53, 77.4%) recommend adjuvant BMAs for patients with natural or treatment induced menopause, and high-risk disease. Only two respondents did not recommend adjuvant bisphosphonates (Table 2). When asked to define what they felt would be considered high risk features, the most common answers were; node positive disease (47/53, 88.7%), patients who received chemotherapy (47/53, 88.7%) and patients with high Oncotype DX scores (39/53, 73.6%) (Table 2).

When asked for recurrence risk thresholds to recommend adjuvant bisphosphonate use > 12%, 25/53 (47.2%) of respondents would consider a 10-year disease recurrence risk > 10% for adjuvant bisphosphonate use. After we had received responses from 17 respondents, the survey was modified. A question asking physicians specifically what 10-year mortality rate they would use to consider adjuvant BMA treatment, and for 35 respondents was added and the most common answer was > 5% (17/35, 48.6%).

The majority of physicians felt that the benefit from adjuvant bisphosphonates was seen in patients with all receptor types (23/53, 43.4%) or mainly in ER/PR positive cohorts (25/53, 47.2%). In their practice oncologists offer adjuvant bisphosphonate therapy to patients they consider high risk either “Always” (14/53, 26.4%), or “Frequently (> 75% of the time)” (27/53, 50.9%). Adjuvant zoledronate (47/53, 88.7%) was the most commonly used BMA at a schedule of either; every 6 months for 3 years (45/53, 84.9%) or 6-monthly for 5 years (4/53, 7.5%). No physicians were prescribing clodronate. The greatest barriers to the wider use of adjuvant bisphosphonate therapy were; risk of toxicities on treatment (e.g. renal toxicity, ONJ, atypical fractures) (34/53, 64.2%) and the requirement for prolonged follow up, at the cancer centre (28/53, 52.8%). Only 5 (9.4%) respondents felt the breast cancer benefits of adjuvant bisphosphonates were not clinically meaningful.

Potential future trials of adjuvant BMAs

Respondents were asked for their views on future trials of adjuvant BMAs with respect to trials evaluating de-escalation of treatment. Most (45/53, 84.9%) would enroll patients on de-escalation trials (Table 3). If such a trial was performed, primary endpoints identified as most important were: a “Combination of the incidence of bone metastasis recurrence as well as the incidence of fragility fractures” (14/53, 26.4%); a “Combination of the incidence of breast cancer recurrence at any site including loco-regional as well as the incidence of fragility fractures” (14/53, 26.4%); or the “Incidence of breast cancer recurrence at any site including loco-regional” (9/53, 17.0%). The most important secondary endpoints were overall survival (12/53, 22.6%), toxicities (7/53, 13.2%) and the incidence of metastatic bone recurrence (7/53, 13.2%).

When presented with a choice of different scenarios of clinical trials, or the option to cite their own alternative design, the majority ranked a randomised trial comparing a single infusion of zoledronate vs. zoledronate every 6 months for 3 years (44/53, 83.0%) as their top choice (Table 3). Alternative trial designs suggested by survey recipients are shown in Supplementary Appendix 1.

Discussion

Evidence-based guideline groups have recommended bisphosphonates as adjuvant therapy for postmenopausal women with EBC as well as premenopausal women treated with ovarian suppression [2, 9,10,11,12]. However, the optimal choice, dosage and duration of bisphosphonate treatment for preventing recurrence and improving survival in women with EBC is unclear. Two important challenges still remain for patients and health care providers, the first being how to increase the number of patients being offered this treatment. The second challenge is identifying the optimum schedule, duration, and type of bisphosphonate therapy. This survey was devised to gain an understanding of current prescribing patterns of Canadian physicians of BMA and provide guidance for potential future trial designs. The latter is of particular importance given that trials in metastatic disease [13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21], AI-induced bone loss [22], and osteoporosis [23,24,25,26], have all demonstrated efficacy with less frequent administration of BMAs.

Survey respondents came from across Canada with varying durations in clinical practice, from early to late career. All physicians were aware of clinical practice guidelines recommending the use of adjuvant bisphosphonate therapy in patients with EBC and not surprisingly the most commonly cited was the CCO/ASCO guideline. Most respondents were aware that these guidelines recommend adjuvant bisphosphonate use for postmenopausal patients with high risk disease. Most physicians cited that the EBCTCG meta-analyses of adjuvant bisphosphate use reported benefit in terms of; reduced risk of disease recurrences/relapse in the bone, increased overall survival and increased breast cancer specific survival.

In their own clinical practice, most respondents recommend BMA use for postmenopausal patients with high risk disease and the most commonly used regimen was 6-monthly zoledronate for 3 years. Interestingly, no respondents were using adjuvant clodronate. This was despite the SWOG 0307 trial that compared intravenous zoledronic acid, oral clodronate, or oral ibandronate, showing no evidence of differences in efficacy by type of bisphosphonate. Indeed, in this study patients expressed preference for oral formulation [27]. Clodronate is not approved for this indication in the USA, while in Canada Respondents felt the greatest barriers to the wider use of adjuvant bisphosphonate therapy were; overall survival, risk of toxicities on treatment (e.g. renal toxicity, ONJ, atypical fractures), and increased requirement for follow up and treatment at the cancer centre.

However, despite the recommendations of evidence-based guideline groups and the findings of the survey it is evident that many questions remain around the optimal choice of agent, route of administration, dose and dosing schedule [28]. This is important as the EBCCTG meta-analysis [1] was unable to demonstrate the superiority of longer durations of bisphosphonate use over shorter schedules. Indeed, this inability to identify the optimal agent, dose or duration of therapy is particularly important with zoledronate where the trials included different durations, dosing intervals, and total number of infusions [9, 29, 30]. Despite different numbers of zoledronate doses at 4 mg with 11 doses in ZO-FAST, 19 doses in AZURE and 7 doses in ABCSG-12 the hazard ratio for disease-free interval was similar (between 0.66 and 0.77) in these trials [9, 29, 30]. The SUCCESS trial compared 2 years of adjuvant zoledronate with 5 years of therapy, and while making no difference in the primary endpoint of bone metastasis free survival, the extra 3 years was associated with a significantly higher incidence of renal toxicity and osteonecrosis of the jaw [31]. Given all these findings it is not surprising that most physicians recommend 6-monthly zoledronate over 3 years over more intense zoledronate regimens for their patients. However, questions around why oral clodronate was not recommended by the respondents require further exploration.

The CCO/ASCO Practice Guideline, ‘Bottom line recommendations’ specifically states, “More research is recommended comparing different bone-modifying agents, doses, dosing intervals, and durations” [2]. For this reason, it is not surprising that most (39 (83.0%) physicians in our survey were interested in enrolling patients on trials using fewer bisphosphonate infusions. The most frequently selected trial design was for a randomised trial comparing a single injection of zoledronate with 6-monthly treatment for 3 years. While a single infusion may be viewed as under treatment, studies have evaluated single-dose of zoledronate and the resulting increase in bone density over 2 years [25, 26], 3 years [32] and 5 years [22] in different patient populations including those with cancer.

Respondents felt the most important primary endpoint for de-escalation trials should be: a combination of the incidence of bone metastasis recurrence as well as the incidence of fragility fractures; a combination of the incidence of breast cancer recurrence at any site including loco-regional as well as the incidence of fragility fractures; or the incidence of breast cancer recurrence at any site including loco-regional. The most important secondary endpoints identified were overall survival, treatment-related toxicities or the incidence of bone metastasis recurrence. Challenges of study designs using endpoints such as fragility fractures and bone recurrences however would be the requirement for a large sample size of several thousand patients, and follow up of several years [9, 10, 29].

There are clear limitations to this study. Firstly, there is always an inherent selection bias in those that are contacted and in those that respond to surveys. In addition, while the study team endeavor to keep our list of email addresses for health care providers up to date this is not always possible. This may explain while although respondents here reported prescribing BMAs to the majority of eligible patients, data shows that only around 20% of eligible patients in Ontario receive adjuvant bisphosphonates. As this is a survey of Canadian health care providers, the choice of BMA is influenced by the funding structure for different agents. In Ontario, adjuvant zoledronate has been publicly funded since 2015, whereas in Quebec the physician has to apply for funding on a case by case basis. Another challenge for this survey was the response rate. As we have observed, the overwhelming situation to all health care workers during the COVID-19 pandemic has made the performance of surveys, and clinical research overall, very challenging. However, despite this, the quality of data received by respondents was excellent, as evidenced by many who took the time to inform us of alternative trial designs shown in Table 3.

Conclusions

To date there has been limited adoption of 6-monthly zoledronate for 3 years as adjuvant therapy for postmenopausal women with higher risk breast cancer in many parts of Canada with the greatest barriers to more widespread use being the risk of treatment-induced toxicities and the increased requirement for follow up and treatment at the cancer centre. Physicians still have questions around the optimal scheduling of zoledronate and are enthusiastic about enrolling patients in a possible trial of single agent zoledronate vs 6-monthly treatment. Health care providers are however, less enthusiastic about trials using either clodronate or longer durations of zoledronate. Given the endpoints identified as important to physicians, such a trial will clearly require a large sample size and considerable international collaboration.

Data availability

Anonymized dataset is available upon request and approval by the Ontario Cancer Research Ethics Board.

References

Early Breast Cancer Trialists’ Collaborative Group (2015) Adjuvant bisphosphonate treatment in early breast cancer: meta-analyses of individual patient data from randomised trials. Lancet 386(10001):1353–1361

Dhesy-Thind S, Fletcher GG, Blanchette PS, Clemons MJ, Dillmon MS, Frank ES, Gandhi S, Gupta R, Mates M, Moy B, Vandenberg T, Van Poznak CH (2017) Use of adjuvant bisphosphonates and other bone-modifying agents in breast cancer: a cancer care ontario and american society of clinical oncology clinical practice guideline. J Clin Oncol 35(18):2062–2081

Hadji P, Coleman RE, Wilson C, Powles T, Clézardin P, Aapro M, Costa L, Body J-J, Markopoulos C, Santini D (2016) Adjuvant bisphosphonates in early breast cancer: consensus guidance for clinical practice from a European Panel. Ann Oncol 27(3):379–390

Balic M, Thomssen C, Würstlein R, Gnant M, Harbeck N (2019) St. Gallen/Vienna 2019: a brief summary of the consensus discussion on the optimal primary breast cancer treatment. Breast Care 14(2):103–110

Curigliano G, Burstein HJ, Winer EP, Gnant M, Dubsky P, Loibl S, Colleoni M, Regan MM, Piccart-Gebhart M, Senn H-J (2017) De-escalating and escalating treatments for early-stage breast cancer: the St Gallen International Expert Consensus Conference on the Primary Therapy of Early Breast Cancer 2017. Ann Oncol 28(8):1700–1712

Cancer Care Ontario, Data request to the Cancer Care Ontario Disclousre Team (2020) https://www.ccohealth.ca/en/request-data-for-research. (Accessed April 14 2020)

McGee SF, Vandermeer L, Mazzarello S, Sienkiewicz M, Stober C, Hutton B, Fergusson D, Hilton J, Caudrelier J-M, Blanchette P (2019) Physician survey of timing of adjuvant endocrine therapy relative to radiotherapy in early stage breast cancer patients. Clin Breast Cancer 19(1):e40–e47

Coleman R, Finkelstein DM, Barrios C, Martin M, Iwata H, Hegg R, Glaspy J, Periañez AM, Tonkin K, Deleu I (2020) Adjuvant denosumab in early breast cancer (D-CARE): an international, multicentre, randomised, controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 21(1):60–72

Coleman R, de Boer R, Eidtmann H, Llombart A, Davidson N, Neven P, von Minckwitz G, Sleeboom HP, Forbes J, Barrios C, Frassoldati A, Campbell I, Paija O, Martin N, Modi A, Bundred N (2013) Zoledronic acid (zoledronate) for postmenopausal women with early breast cancer receiving adjuvant letrozole (ZO-FAST study): final 60-month results. Ann Oncol 24(2):398–405

Gnant M, Pfeiler G, Dubsky PC, Hubalek M, Greil R, Jakesz R, Wette V, Balic M, Haslbauer F, Melbinger E, Bjelic-Radisic V, Artner-Matuschek S, Fitzal F, Marth C, Sevelda P, Mlineritsch B, Steger GG, Manfreda D, Exner R, Egle D, Bergh J, Kainberger F, Talbot S, Warner D, Fesl C, Singer CF (2015) Adjuvant denosumab in breast cancer (ABCSG-18): a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet (London, England) 386(9992):433–43

Ellis GK, Bone HG, Chlebowski R, Paul D, Spadafora S, Smith J, Fan M, Jun S (2008) Randomized trial of denosumab in patients receiving adjuvant aromatase inhibitors for nonmetastatic breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 26(30):4875–82

Coleman R, Body JJ, Aapro M, Hadji P, Herrstedt J (2014) Bone health in cancer patients: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines. Ann Oncol 25(Suppl 3): iii124–37

Amir E, Freedman O, Carlsson L, Dranitsaris G, Tomlinson G, Laupacis A, Tannock IF, Clemons M (2013) Randomized feasibility study of de-escalated (every 12 wk) versus standard (every 3 to 4 wk) intravenous pamidronate in women with low-risk bone metastases from breast cancer. Am J Clin Oncol 36(5):436–42

Kuchuk I, Beaumont JL, Clemons M, Amir E, Addison CL, Cella D (2013) Effects of de-escalated bisphosphonate therapy on the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Bone Pain, Brief Pain Inventory and bone biomarkers. J Bone Oncol 2(4):154–7

Addison CL, Pond GR, Zhao H, Mazzarello S, Vandermeer L, Goldstein R, Amir E, Clemons M (2014) Effects of de-escalated bisphosphonate therapy on bone turnover biomarkers in breast cancer patients with bone metastases. Springerplus 3:577

Addison CL, Bouganim N, Hilton J, Vandermeer L, Dent S, Amir E, Hopkins S, Kuchuk I, Segal R, Song X, Gertler S, Mazzarello S, Dranitsaris G, Ooi D, Pond G, Clemons M (2014) A phase II, multicentre trial evaluating the efficacy of de-escalated bisphosphonate therapy in metastatic breast cancer patients at low-risk of skeletal-related events. Breast Cancer Res Treat 144(3):615–24

Amadori D, Aglietta M, Alessi B, Gianni L, Ibrahim T, Farina G, Gaion F, Bertoldo F, Santini D, Rondena R, Bogani P, Ripamonti CI (2013) Efficacy and safety of 12-weekly versus 4-weekly zoledronic acid for prolonged treatment of patients with bone metastases from breast cancer (ZOOM): a phase 3, open-label, randomised, non-inferiority trial. Lancet Oncol 14(7):663–70

Lipton A, Steger GG, Figueroa J, Alvarado C, Solal-Celigny P, Body JJ, de Boer R, Berardi R, Gascon P, Tonkin KS, Coleman R, Paterson AH, Peterson MC, Fan M, Kinsey A, Jun S (2007) Randomized active-controlled phase II study of denosumab efficacy and safety in patients with breast cancer-related bone metastases. J Clin Oncol 25(28):4431–7

Himelstein AL, Foster JC, Khatcheressian JL, Roberts JD, Seisler DK, Novotny PJ, Qin R, Go RS, Grubbs SS, O’Connor T, Velasco MR Jr, Weckstein D, O’Mara A, Loprinzi CL, Shapiro CL (2017) Effect of longer-interval vs standard dosing of zoledronic acid on skeletal events in patients with bone metastases: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 317(1):48–58

Hortobagyi GN, Van Poznak C, Harker WG, Gradishar WJ, Chew H, Dakhil SR, Haley BB, Sauter N, Mohanlal R, Zheng M, Lipton A (2017) Continued treatment effect of zoledronic acid dosing every 12 vs 4 weeks in women with breast cancer metastatic to bone: the OPTIMIZE-2 randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol 3(7):906–912

Ibrahim MF, Mazzarello S, Shorr R, Vandermeer L, Jacobs C, Hilton J, Hutton B, Clemons M (2015) Should de-escalation of bone-targeting agents be standard of care for patients with bone metastases from breast cancer? Ann Oncol 26(11):2205–13

Brown JE, Ellis SP, Lester JE, Gutcher S, Khanna T, Purohit OP, McCloskey E, Coleman RE (2007) Prolonged efficacy of a single dose of the bisphosphonate zoledronic acid. Clin Cancer Res 18(Pt 1):5406–10

Khan SA, Kanis JA, Vasikaran S, Kline WF, Matuszewski BK, McCloskey EV, Beneton MN, Gertz BJ, Sciberras DG, Holland SD, Orgee J, Coombes GM, Rogers SR, Porras AG (1997) Elimination and biochemical responses to intravenous alendronate in postmenopausal osteoporosis. J Bone Miner Res 12(10):1700–7

Black DM, Delmas PD, Eastell R, Reid IR, Boonen S, Cauley JA, Cosman F, Lakatos P, Leung PC, Man Z, Mautalen C, Mesenbrink P, Hu H, Caminis J, Tong K, Rosario-Jansen T, Krasnow J, Hue TF, Sellmeyer D, Eriksen EF, Cummings SR (2007) Once-yearly zoledronic acid for treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis. N Engl J Med 356(18):1809–22

Greenspan SL, Perera S, Ferchak MA, Nace DA, Resnick NM (2015) Efficacy and safety of single-dose zoledronic acid for osteoporosis in frail elderly women: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Internal Med 175(6):913–21

Ofotokun I, Titanji K, Lahiri CD, Vunnava A, Foster A, Sanford SE, Sheth AN, Lennox JL, Knezevic A, Ward L, Easley KA, Powers P, Weitzmann MN (2016) A Single-Dose Zoledronic Acid Infusion Prevents Antiretroviral Therapy-Induced Bone Loss In Treatment-naive HIV-infected patients: a phase IIb trial. Clin Infect Dis 63(5):663–671

Gralow JR, Barlow WE, Paterson AH, Miao JL, Lew DL, Stopeck AT, Hayes DF, Hershman DL, Schubert MM, Clemons M (2020) Phase III randomized trial of bisphosphonates as adjuvant therapy in breast cancer: S0307. J Natl Cancer Inst

Jacobs C, Amir E, Paterson A, Zhu X, Clemons M (2015) Are adjuvant bisphosphonates now standard of care of women with early stage breast cancer? A debate from the Canadian Bone and the Oncologist New Updates meeting. J Bone Oncol 4(2):54–8

Coleman R, Cameron D, Dodwell D, Bell R, Wilson C, Rathbone E, Keane M, Gil M, Burkinshaw R, Grieve R, Barrett-Lee P, Ritchie D, Liversedge V, Hinsley S, Marshall H (2014) Adjuvant zoledronic acid in patients with early breast cancer: final efficacy analysis of the AZURE (BIG 01/04) randomised open-label phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 15(9):997–1006

Gnant M, Mlineritsch B, Stoeger H, Luschin-Ebengreuth G, Knauer M, Moik M, Jakesz R, Seifert M, Taucher S, Bjelic-Radisic V, Balic M, Eidtmann H, Eiermann W, Steger G, Kwasny W, Dubsky P, Selim U, Fitzal F, Hochreiner G, Wette V, Sevelda P, Ploner F, Bartsch R, Fesl C, Greil R (2015) Zoledronic acid combined with adjuvant endocrine therapy of tamoxifen versus anastrozol plus ovarian function suppression in premenopausal early breast cancer: final analysis of the Austrian Breast and Colorectal Cancer Study Group Trial 12. Ann Oncol 26(2):313–20

Domschke C, Schuetz F (2014) Side effects of bone-targeted therapies in advanced breast cancer. Breast Care (Basel, Switzerland) 9(5):332–6

Grey A, Bolland MJ, Horne A, Mihov B, Gamble G, Reid IR (2017) Duration of antiresorptive activity of zoledronate in postmenopausal women with osteopenia: a randomized, controlled multidose trial. CMAJ Can Med Assoc J [Journal de l'Association medicale canadienne] 189(36): E1130–E1136

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to health care providers for their participation in this survey.

Funding

The research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors. This work was supported by the Rethinking Clinical Trials (REaCT) Program platform at the Ottawa Hospital which is supported by The Ottawa Hospital Foundation and its generous donors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SM, AJM, LV, KC, GL, GP and MC designed the survey and prepared the protocol. LV collected the data and coordinated the study. SM, AJM, and GP did the statistical analysis. All authors had full access to the data and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. SM, AJM, GP, DS and MC wrote the manuscript. All authors were involved in the critical review of the manuscript and approved the final version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

SMG reports receipt of honorarium from Novartis for insights on management of breast cancer patients. AA has participated on an advisory board for Novartis, Eli Lily, Exactis innovation and Pfizer, has received honoraria from Apobiologix and Roche and has received travel funds from Roche. BH and MC reports consulting fees from Cornerstone Research, outside the submitted work. All other authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of each institution Research Ethics Board and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. All data has been anonymized to protect the identities of subjects involved in the research.

Informed consent

Completion of the survey implied consent to participate.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

McGee, S., Alzahrani, M., Vandermeer, L. et al. Adjuvant bisphosphonate use in patients with early stage breast cancer: a physician survey. Breast Cancer Res Treat 187, 477–486 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-021-06147-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-021-06147-1