Abstract

Purpose

Some studies have indicated age-specific differences in quality of life (QoL) among breast cancer (BC) patients. The aim of this study was to compare patient-reported outcomes after conventional and oncoplastic breast surgery in two distinct age groups.

Methods

Patients who underwent oncoplastic and conventional breast surgery for stage I-III BC, between 6/2011–3/2019, were identified from a prospectively maintained database. QoL was prospectively evaluated using the Breast-Q questionnaire. Comparisons were made between women < 60 and ≥ 60 years.

Results

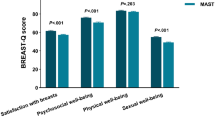

One hundred thirty-three patients were included. Seventy-three of them were ≥ 60 years old. 15 (20.5%) of them received a round-block technique (RB) / oncoplastic breast-conserving surgeries (OBCS), 10 (13.7%) underwent nipple-sparing mastectomies (NSM) with deep inferior epigastric perforator flap (DIEP) reconstruction, 23 (31.5%) underwent conventional breast-conserving surgeries (CBCS), and 25 (34.2%) received total mastectomy (TM). Sixty patients were younger than 60 years, 15 (25%) thereof received RB/OBCS, 22 (36.7%) NSM/DIEP, 17 (28.3%) CBCS, and 6 (10%) TM. Physical well-being chest and psychosocial well-being scores were significantly higher in older women compared to younger patients (88.05 vs 75.10; p < 0.001 and 90.46 vs 80.71; p = 0.002, respectively). In multivariate linear regression, longer time intervals had a significantly positive effect on the scales Physical Well-being Chest (p = 0.014) and Satisfaction with Breasts (p = 0.004). No significant results were found concerning different types of surgery.

Conclusion

Our findings indicate that age does have a relevant impact on postoperative QoL. Patient counseling should include age-related considerations, however, age itself cannot be regarded as a contraindication for oncoplastic surgery.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Over the last decades, significant improvements have been made in the treatment of breast cancer (BC), resulting in improved survival rates, especially in early-stage disease [1]. As a result of improved survival outcomes, breast cancer is increasingly perceived as a chronic disease, and thus survivors’ health-related quality of life (QoL) has become a major focus of overall treatment. Since BC can affect different age groups, it seems important to examine age-related differences in terms of QoL. This might contribute to personalized decision making, taking into account this important variable when counseling our patients.

While a vast body of literature examining age-specific differences in QoL related to systemic treatments and survivorship exists [2,3,4], only few studies have investigated age-related differences in postoperative QoL, comparing different breast surgery procedures [5, 6]. In particular, there is a lack of data on QoL in older patients after BC surgery. This is relevant as a high proportion of newly diagnosed BC affects older women, and evidence is needed to provide proper counseling to this patient population in clinical practice. Previous studies have shown that younger patients have worse QoL outcomes in the social domain, being more concerned with their physical appearance and femininity. Older patients, in contrast, often see their breast appearance as a less important aspect of their QoL, but they tend to score lower in the physical well-being domains [5]. As such, it is important to further investigate possible age-related differences in patient-reported outcomes. Additionally, in the era of personalized BC therapy, age-related differences and requirements should be considered when planning the patient’s treatment [7, 8]. The aim of this study was to compare QoL in two distinct age groups after conventional and oncoplastic breast surgery using the Breast-Q as validated, patient-reported outcome assessment tool [9,10,11].

Methods

Study design and patients

A retrospective review of a prospectively maintained database of consecutive patients undergoing BC surgery between June 2011 and March 2019 by three selected breast surgeons from the Department of Surgery of a tertiary referral center in Switzerland was performed. Women were eligible for study inclusion if they underwent either conventional surgical techniques, such as total mastectomy (TM) and conventional breast-conserving surgeries (CBCS), or oncoplastic breast-conserving surgeries (OBCS), specifically round-block technique (RB) or nipple-sparing mastectomy (NSM) with deep inferior epigastric perforator flap (DIEP) reconstruction. The response rate was 43%.

A cross-sectional survey was conducted using the Breast-Q, a validated, procedure-specific, patient-reported outcome assessment tool, to assess patient satisfaction and health-related QoL via the outcome collecting software Heartbeat® [9,10,11]. Patients were subdivided into two age groups: < 60 (“younger”) and ≥ 60 years (“older”) according to the age threshold defined by the United Nations [12]. Variables regarding patient, tumor, treatment, and outcome were recorded in a dedicated study database (Secu Trial®).

Statistical analysis

Patients were analyzed by age and type of surgery: RB/OBCS, NSM with DIEP reconstruction, CBCS and TM. We analyzed the following Breast-Q scales: Physical Well-being Chest, Psychosocial Well-being, Sexual Well-being and Satisfaction with Breasts. Each scale is scored from 0 to 100; higher scores represent more satisfaction or better QoL.

Continuous variables were reported by mean, standard deviation (SD), median, minimum, and maximum values. Categorical variables were summarized by absolute frequencies and percentages. Mean values were compared by age categories using T-tests. Occurrences were compared by age categories using Fisher’s exact test for association. Surgical complications were categorized according to the Clavien-Dindo classification [13]. Recurrence was defined as either local, loco-regional, regional, distant or combined recurrence.

Multivariate linear regression analysis for all Breast-Q scales with age category (< 60 years old, ≥ 60 years old) as covariate was performed. Additional covariates were entered into the model based on stepwise selection: type of surgery (RB/OBCS, NSM/DIEP, CBCS, TM), year of surgery, comorbidities at baseline (yes, no), recurrence (yes, no), time from surgery to follow-up Breast-Q. A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were conducted in SAS version 9.2.

Results

133 patients operated by breast surgeons with or without plastic surgeons were included in the study. The group of older patients consisted of 73 patients: 15 (20.5%) of them underwent RB/OBCS, 10 (13.7%) NSM with DIEP reconstruction, 23 (31.5%) CBCS, and 25 (34.2%) TM. The younger patient group consisted of 60 women: 15 (25%) underwent RB/OBCS, 22 (36.7%) NSM with DIEP, 17 (28.3%) CBCS, and 6 (10%) TM. In the older patient group the mean age was 71.63 (SD 8.39) years and in the younger patient group 49.72 (SD 7.29) years. The mean time from surgery to follow-up Breast-Q was 37.27 (SD 22.25) months in the older group and 35.34 (SD 25.24) months in the younger group. The groups differed significantly in terms of comorbidities (p < 0.001) and type of surgery (p = 0.001): older patients had significantly more comorbidities (65.8% vs. 25.0%) and underwent TM more often (34.2% vs. 10.0%); younger patients underwent NSM with DIEP more often (36.7% vs. 13.7%). Additionally, younger patients were significantly more often treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy (13.3% vs. 2.7%; p = 0.042). Other characteristics, such as T-stage, recurrence or surgical complications did not differ significantly (Table 1).

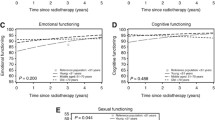

Physical Well-being chest

In older patients, mean scores for physical well-being chest were calculated in all groups: CBCS (91.7 SD 18.7), DIEP with NSM (88.2 SD 14.3), TM (88.1 SD 12.5), and OBCS (82.3 SD 19.2). Regarding the physical well-being of younger patients, mean scores were significantly lower than in older patients (p < 0.001). The results were comparable in CBCS (76.7 SD 16.3), OBCS (76.1 SD 15.3) and NSM with DIEP (75.3 SD 18.1), while TM scores were rather lower (67.7 SD 30.9). Overall, however, there were no significant differences between the types of surgery concerning physical well-being chest score (Fig. 1a; Table 2). Multivariate linear regression showed significant effects on the score by age category and by time from surgery to follow-up Breast-Q: better results were found in the older patient group (p < 0.001), and results were significantly better with a longer time interval between surgery and Breast-Q survey (p = 0.014) (Table 3).

Psychosocial well-being

When looking at psychosocial well-being, high values were reported in older patients: NSM with DIEP reached a mean score of 98.3 (SD 5.4), followed by CBCS (91.0 SD 14.1), TM (88.1 SD 17.4), and OBCS (88.1 SD 11.5). In younger patients the mean scores were significantly lower (p = 0.002): OBCS (83.9 SD 17.5) and NSM with DIEP (83.6 SD 19.4) scored highest, followed by CBCS (80.1 SD 19.7). TM showed a considerably lower score (64.7 SD 29.8). However, again no significant differences were found among the individual types of surgery (Fig. 1b; Table 2). Multivariate linear regression confirmed significantly better results in the older patient group (p = 0.002) (Table 3).

Satisfaction with breasts

In the older patient group, NSM with DIEP reconstruction achieved the highest scores (84.6 SD 18.3), followed by breast-conserving surgeries, CBCS (75.0 SD 25.3) and OBCS (72.1 DS 18.5). The TM outcome was lower with a mean score of 65.0 (SD 23.0). In the younger patient group, the breast-conserving surgery types, namely CBCS (80.2 SD 19.1) and OBCS (79.2 SD 16.6) showed the highest satisfaction. Comparable results were obtained with NSM with DIEP reconstruction (75.1 SD 22.2). The TM group performed worse with a mean score of 61 (SD 26.9). Once more, differences between the types of surgery were not significant (Fig. 1c; Table 2). Multivariate linear regression showed significant effects on the score by year of surgery and by time from surgery to follow-up Breast-Q: patients surveyed in later years and with a longer time interval between surgery and Breast-Q survey scored significantly better (p = 0.026; p = 0.004) (Table 3).

Sexual Well-being

In the older patient group, the questions regarding sexual well-being were answered by 44% (n = 32). DIEP with NSM achieved the maximum score (100 SD 0.0), OBCS was rated second (75.6 SD 21.3). The conventional techniques, CBCS (67.8 SD 26.2) and TM (66.5 SD 27.9) showed lower values. In the younger patient group, the scale was completed by 75% (n = 45): OBCS showed the highest score (74.9 SD 22.4), TM (65.8 SD 30.1), NSM with DIEP (65.5 SD 33.9) and CBCS (65.0 SD 22.1) were rated comparably low. Again, no significant differences between the types of surgery were found (Fig. 1d; Table 2). Multivariate linear regression showed no significant influences on the scores of sexual well-being (Table 3).

Discussion

This study analyzed patient-reported outcomes in 133 stage I-III BC patients who underwent NSM with DIEP, OBCS, CBCS or TM, comparing older patients, over 60 years of age, with younger patients under the age of 60 years. We have found that older patients achieved significantly higher scores in the psychosocial well-being and physical well-being chest domains compared to younger patients. These findings confirm our hypothesis that there are relevant age-specific differences to be taken into account when informing patients on their surgical options.

Age group comparison in different Breast-Q domains

Regarding psychosocial well-being, the results are in line with previous research. Studies on BC survivors found that in younger women psychological distress related to diagnosis and treatment and overall psychosocial well-being were significantly worse compared to elderly patients [6, 7]. Concerning physical well-being, on the other hand, there is a discrepancy with the findings reported in literature. Previous studies showed that older women had poorer physical and chest well-being and generally seemed to be more vulnerable to the physical impact of BC regardless of type of surgery [6, 7]. We instead found that older women had better physical well-being scores than their younger counterparts, which is also surprising given the higher comorbidity rate of the older group (Table 1). The good outcome in terms of physical well-being might be explained by the fact that, in our unit, elderly patients are only chosen for oncoplastic surgery if they are in a good general condition for their age. On the other hand, our favorable results among older patients reinforce the concept that age itself should not be considered a contraindication for any surgical procedure.

In our study, we were not able to show any significant difference between the older and younger patients in terms of their sexual well-being score. It has been described in various studies that BC has a stronger negative impact on the sexuality of younger patients [5, 14]. Nevertheless, our results should be interpreted with caution since only 44% of the older patients answered this module.

In terms of breast satisfaction there were comparable overall results in both age groups. One would assume that postoperative breast satisfaction is worse in younger patients, as younger women are more concerned with their physical appearance and femininity [14]. This was not confirmed in our study given the absence of substantial differences in overall scores. This could be associated with the fact that younger patients are more likely to have aesthetically pleasing breasts with less ptosis already preoperatively, whereby the aim is the preservation of aesthetics. In older patients, however, oncoplastic breast surgery can even result in an improvement of aesthetics.

In summary, our study showed significantly higher scores in older patients concerning psychosocial well-being and physical well-being chest compared to younger patients. This suggests that even complex reconstructive surgical techniques could be recommendable for older patients, as they have a very good outcome regarding QoL postoperatively. The literature shows, that there are obstacles to overcome regarding the use of oncoplastic and reconstructive surgery in elderly patients. Among other things, there are prejudices related to body image of older patients, but also insufficient involvement of the patients in the decision making process, when it comes to their surgical therapy and potential breast reconstruction [15]. On the other hand, especially in younger women, care must be taken to become aware of pain or physical limitations in the breast area at an early stage and to treat those problems tiemly. The same applies to psychosocial problems.

Comparison of satisfaction and QoL by age after different breast procedures

We have found that the results of QoL were more homogeneous in older patients when comparing the four selected types of surgery, without substantial differences after the various procedures. A few comparable studies have shown similar results [16]. The EORTC 10,850 randomized trial, for instance, analyzed survival and QoL in elderly patients, undergoing mastectomy or tumor excision plus tamoxifen. The two groups did not differ in terms of QoL, except that tumor excision patients reported fewer arm problems and a borderline significant benefit in body image [17].

In the group of younger patients, on the other hand, the difference between TM and the other surgical procedures was noticeable in all four domains. The inferiority of mastectomy in terms of quality of life has been shown in several studies, whereas divergent results have been reported when comparing breast-conserving surgeries and SSM/NSM with reconstruction [18,19,20,21,22,23,24]. In our study, we could not demonstrate a significant influence of the different types of surgery on the Breast-Q scales. This is most likely due to the too small sample sizes of the individual types of surgery.

Other influences on Breast-Q scales

In our study, both physical well-being chest and satisfaction with breasts showed significantly better scores with longer time intervals between surgery and Breast-Q survey. Concerning satisfaction with breasts, a study by Atisha et al. showed opposing results [25]. However, the comparability to this study is questionable, as it had a considerably higher mean time interval between surgery and Breast-Q survey of 6.7 years (our study: 3.1 years). Other studies showed a significant increase in breast-Q scores with a longer time interval between surgery and survey [6, 19, 26] or no significant differences in the scores of either physical well-being chest and satisfaction with breasts at different points in time [27, 28]. Even though varying results were found in previous studies, the time interval between surgery and Breast-Q survey seems to be a possible influence on Breast-Q scores, which should be taken into account in future study designs.

Additionally, satisfaction with breasts showed better scores in patients operated on in later years. This can be explained in our particular case by the advanced training of the surgeons and therefore increased use of oncoplastic surgery in later years. A significant influence of the different types of surgery could not be shown directly, which is most likely due to the low sample size per type of surgery.

Limitations and Strengths

The main limitation of this study is the relatively small sample size. This is due to the fact that we included consecutive patients undergoing a specific set of procedures performed by three senior surgeons during a limited study period since introduction of OPS at the study site. This, in turn, increased comparability of outcomes due to similarities in technical performance of the procedures. Additionally, to make the groups as homogeneous as possible we only included specific types of operations. However, further studies with larger sample sizes are necessary to validate these data.

Another limitation is the considerable variation in the timing of Breast-Q assessment due to the cross-sectional nature of the survey. As mentioned above, previous studies have shown varying results concerning changes of Breast-Q scores over time, suggesting that questionnaires should be collected at comparable postoperative intervals [6, 19, 25,26,27,28]. However, the mean time from surgery to follow-up Breast-Q was found to be comparable in both groups.

As this study is a cross-sectional study, there is also no preoperative survey available for comparison, which can also represent a limitation to interpretation of our data.

Finally, this is an observational study, and selection criteria for type of surgery may have an impact on QoL. One strength of our study is that all surgeons in our unit are specialized in oncoplastic surgery, and therefore all surgical procedures are highly standardized. Furthermore, to prevent bias, we specifically looked at the cases of three experienced breast surgeons. Our study provides new insights in a field, where there is still paucity of evidence and our results confirm the relevance of age-specific differences in surgical-related QoL outcomes.

Conclusion

The current study indicates that age does have an impact on postoperative QoL. Patient counseling should include age-related considerations although age itself should, in our opinion, not be regarded as a contraindication for oncoplastic and reconstructive surgery. It is important not to withhold any surgical techniques from patients based solely on age, since, despite preconceptions, they can have a good or even better postoperative quality of life than younger patients. Our findings support personalized counseling for all women undergoing BC surgery and tailored care to address and anticipate the specific age-related physical and psychosocial needs of these patients. Attention to life-stage issues and concerns can help to improve postoperative QoL and patient satisfaction, as such improving overall patient care. Further studies with larger patient cohorts are necessary to corroborate our findings.

References

Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A (2016) Cancer statistics 2016. CA A Cancer J Clinic 66(1):7–30

Leinert E, Singer S, Janni W, Harbeck N, Weissenbacher T, Rack B, Augustin D, Wischnik A, Kiechle M, Ettl J (2017) The impact of age on quality of life in breast cancer patients receiving adjuvant chemotherapy: a comparative analysis from the prospective multicenter randomized ADEBAR trial. Clin Breast Cancer 17(2):100–106

Arraras J, Illarramendi J, Manterola A, Asin G, Salgado E, Arrondo P, Dominguez M, Arrazubi V, Martinez E, Viudez A (2019) Quality of life in elderly breast cancer patients with localized disease receiving endocrine treatment: a prospective study. Clin Transl Oncol 21(9):1231–1239

Arndt V, Merx H, Stürmer T, Stegmaier C, Ziegler H, Brenner H (2004) Age-specific detriments to quality of life among breast cancer patients one year after diagnosis. Eur J Cancer 40(5):673–680

Cimprich B, Ronis DL, Martinez-Ramos G (2002) Age at diagnosis and quality of life in breast cancer survivors. Cancer Pract 10(2):85–93

Cordova LZ, Hunter-Smith DJ, Rozen WM (2019) Patient reported outcome measures (PROMs) following mastectomy with breast reconstruction or without reconstruction: a systematic review. Gland Surg 8(4):441

Morris J, Royle G (1988) Offering patients a choice of surgery for early breast cancer: a reduction in anxiety and depression in patients and their husbands. Soc Sci Med 26(6):583–585

Collins ED, Moore CP, Clay KF, Kearing SA, O’Connor AM, Llewellyn-Thomas HA, Barth RJ Jr, Sepucha KR (2009) Can women with early-stage breast cancer make an informed decision for mastectomy? J Clin Oncol 27(4):519–525

Pusic AL, Klassen AF, Scott AM, Klok JA, Cordeiro PG, Cano SJ (2009) Development of a new patient-reported outcome measure for breast surgery: the BREAST-Q. Plast Reconstr Surg 124(2):345–353

Liu LQ, Branford OA, Mehigan S (2018) Breast q measurement of the patient perspective in oncoplastic breast surgery a systematic review. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery Global Open 6(8): 1904

Chen CM, Cano SJ, Klassen AF, King T, McCarthy C, Cordeiro PG, Morrow M, Pusic AL (2010) Measuring quality of life in oncologic breast surgery: a systematic review of patient-reported outcome measures. Breast J 16(6):587–597

Swaminathan V, Audisio R (2012) Cancer in older patients: an analysis of elderly oncology. Ecancermedicalscience 6

Dindo D (2014) The Clavien–Dindo classification of surgical complications. In: Treatment of postoperative complications after digestive surgery. Springer, pp 13–17

Miaja M, Platas A, Martinez-Cannon BA (2017) Psychological impact of alterations in sexuality, fertility, and body image in young breast cancer patients and their partners. Rev Invest Clin 69(4):204–209

James R, McCulley S, Macmillan R (2015) Oncoplastic and reconstructive breast surgery in the elderly. Br J Surg 102(5):480–488

Medina-Franco H, García-Alvarez MN, Rojas-García P, Trabanino C, Drucker-Zertuche M, Arcila D (2010) Body image perception and quality of life in patients who underwent breast surgery. Am Surg 76(9):1000–1005

De Haes J, Curran D, Aaronson NK, Fentiman I (2003) Quality of life in breast cancer patients aged over 70 years, participating in the EORTC 10850 randomised clinical trial. Eur J Cancer 39(7):945–951

Howes BH, Watson DI, Xu C, Fosh B, Canepa M, Dean NR (2016) Quality of life following total mastectomy with and without reconstruction versus breast-conserving surgery for breast cancer: A case-controlled cohort study. J Plast Recons Aesthetic Surg 69(9):1184–1191

Collins KK, Liu Y, Schootman M, Aft R, Yan Y, Dean G, Eilers M, Jeffe DB (2011) Effects of breast cancer surgery and surgical side effects on body image over time. Breast Cancer Res Treat 126(1):167–176

Jagsi R, Li Y, Morrow M, Janz N, Alderman A, Graff J, Hamilton A, Katz S, Hawley S (2015) Patient-reported quality of life and satisfaction with cosmetic outcomes after breast conservation and mastectomy with and without reconstruction: results of a survey of breast cancer survivors. Ann Surg 261(6):1198

Sun Y, Kim S-W, Heo CY, Kim D, Hwang Y, Yom CK, Kang E (2014) Comparison of quality of life based on surgical technique in patients with breast cancer. Jpn J Clin Oncol 44(1):22–27

Fung KW, Lau Y, Fielding R, Or A, Yip AWC (2001) The impact of mastectomy, breast-conserving treatment and immediate breast reconstructions on the quality of life of Chinese women. ANZ J Surg 71(4):202–206

Morris J, Ingham R (1988) Choice of surgery for early breast cancer: Psychosocial considerations. Soc Sci Med 27(11):1257–1262

Bailey CR, Ogbuagu O, Baltodano PA, Simjee UF, Manahan MA, Cooney DS, Jacobs LK, Tsangaris TN, Cooney CM, Rosson GD (2017) Quality-of-life outcomes improve with nipple-sparing mastectomy and breast reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg 140(2):219–226

Atisha DM, Rushing CN, Samsa GP, Locklear TD, Cox CE, Hwang ES, Zenn MR, Pusic AL, Abernethy AP (2015) A national snapshot of satisfaction with breast cancer procedures. Ann Surg Oncol 22(2):361–369

Howard MA, Sisco M, Yao K, Winchester DJ, Barrera E, Warner J, Jaffe J, Hulick P, Kuchta K, Pusic AL (2016) Patient satisfaction with nipple-sparing mastectomy: A prospective study of patient reported outcomes using the BREAST-Q. J Surg Oncol 114(4):416–422

Allen RJ, Sobti N, Patel AR, Matros E, McCarthy CM, Dayan JH, Disa JJ, Mehrara BJ, Morrow M, Pusic AL (2020) Laterality and patient-reported outcomes following autologous breast reconstruction with free abdominal tissue: an 8-year examination of BREAST-Q data. Plast Reconstr Surg 146(5):964–975

Eltahir Y, Werners LL, Dreise MM, van Emmichoven IAZ, Jansen L, Werker PM, de Bock GH (2013) Quality-of-life outcomes between mastectomy alone and breast reconstruction: comparison of patient-reported BREAST-Q and other health-related quality-of-life measures. Plast Reconstr Surg 132(2):201e–209e

Acknowledgements

We thank the Quality Management team of the University Hospital Basel for their help and support in the implementation of the outcome collecting software Heartbeat®. We thank Constantin Sluka and his team oft the Clinical Trial Unit Basel for the maintenance of the online clinical data management system secuTrial®.

Funding

Open Access funding provided by Universität Basel (Universitätsbibliothek Basel). This work was funded by the Department of Surgery University Hospital of Basel. This funding source had no involvement in study design; in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; and in the decision to submit the article for publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

E.A. Kappos has received research support by the “Freiwillige Akademische Gesellschaft Basel”. W.P. Weber has received research support from Takeda Pharmaceuticals International via Swiss Group for Clinical Cancer Research (SAKK), honoraria/consultation from Genomic Health, Inc., USA, and support for conferences and meetings from Sandoz, Genomic Health, Medtronic, Novartis Oncology and Pfizer. Jeremy Levy has received personal fees for his work from the Department of Plastic, Reconstructive and Aesthetic Surgery and the Department of Breast Surgery. All other authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ritter, M., Ling, B.M., Oberhauser, I. et al. The impact of age on patient-reported outcomes after oncoplastic versus conventional breast cancer surgery. Breast Cancer Res Treat 187, 437–446 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-021-06126-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-021-06126-6