Abstract

Purpose

To evaluate patient-reported cosmetic satisfaction in women treated with radiation therapy for breast cancer and to determine the association between dissatisfaction and quality of life (QoL) and depression.

Methods

Within the prospective UMBRELLA breast cancer cohort, all patients ≥ 1 year after breast conserving treatment or mastectomy with immediate reconstruction were selected. Self-reported cosmetic satisfaction was measured on a 5-point Likert scale. QoL, social functioning, and emotional functioning were measured using EORTC QLQ-C30 and BR23 at 1, 2, and 3 years after inclusion. Mixed model analysis was performed to assess the difference in different domains of QoL between patients with good versus poor self-reported cosmetic satisfaction over time after adjustment for potential confounders. Depression scores were collected by means of the HADS-NL questionnaire. Chi-square test or Fisher's exact test was used to assess the difference in proportions of HADS score ≥ 8, indicating increased depression risk, between satisfied and dissatisfied patients.

Results

808 patients were selected for analysis. Respectively one, two, and three years after surgery, 8% (63/808), 7% (45/626), and 8% (31/409) of patients were dissatisfied with their cosmetic outcome. Poor patient-reported cosmetic satisfaction was independently associated with impaired QoL, body image, and lower emotional and social functioning. Scores ≥ 8 on the HADS depression subscale were significantly more common in dissatisfied patients.

Conclusions

Dissatisfaction with cosmetic outcome was low after breast cancer surgery followed by radiation therapy during 3 years follow-up. Knowing the association between dissatisfaction with cosmetic outcome and QoL and depression could help to improve the preoperative counseling of breast cancer patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Due to the rising incidence of breast cancer, and the improved survival rates, the number of women living with the consequences of breast cancer and breast cancer treatment is growing [1]. As a result, cosmetic satisfaction and quality of life (QoL) after breast cancer treatment are increasingly being recognized as important.

Since the introduction of breast cancer screening programs, breast cancer is often detected at an earlier stage [2]. Consequentially, the majority of breast cancer patients can be treated with breast-conserving therapy, a combination of breast-conserving surgery and breast irradiation [3, 4]. Concurrently, the interest in oncoplastic and reconstructive surgery is rising, leading to improved cosmetic results and consequently higher expectations in patients. However, the long-term degree of self-reported cosmetic satisfaction with modern treatments and how this affects QoL is yet unclear.

The aim of this study was to evaluate the prevalence of poor patient-reported cosmetic satisfaction up to 3 years following breast cancer treatment, to assess the determinants associated with poor cosmetic outcome, and to evaluate the association of poor cosmetic satisfaction with social functioning, emotional functioning, body image, and depression.

Methods

This study was conducted within the UMBRELLA cohort (Utrecht cohort for Multiple BREast cancer intervention studies and Long-term evaLuAtion) [5]. This prospective observational cohort includes breast cancer patients referred for post-operative radiation therapy to the department of Radiation Oncology at the Utrecht Medical Center Utrecht (UMC), the Netherlands. Here, prior to the start of radiation therapy, all breast cancer patients are invited to participate in the UMBRELLA. Inclusion criteria are invasive breast cancer or ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS), age over 18 years, and good understanding of the Dutch language. The UMBRELLA study complies with the Dutch law on Medical Research in Humans and was approved by the Medical Ethical Committee of the UMC.

Upon inclusion, all patients were asked for informed consent for the collection of clinical data and patient-reported outcomes (PROs). Clinical data were obtained through the Netherlands Comprehensive Cancer Organization (IKNL) [1]. Data on PROs were collected through self-reported questionnaires, which were collected before the start of radiation therapy (baseline) and at 3, 6, 12, 18, and 24 months after inclusion.

All patients enrolled in UMBRELLA between October 2013 and June 2018 were eligible for this study. Patients were selected when they completed the cosmetic evaluation questionnaire at 12 months after inclusion. In the cosmetic evaluation questionnaire the treated breast is compared to contralateral breast, therefore patients with mastectomy without breast reconstruction were excluded.

Cosmetic satisfaction was measured by means of a structured questionnaire by Sneeuw et al. [6]. This questionnaire was specifically designed to measure satisfaction with the breast after radiation therapy. Patients reported their satisfaction with cosmetic outcome in comparison to the contralateral breast on a 5-point Likert scale. UMBRELLA participants filled out this questionnaire at 12 months after inclusion, as scars will have matured at this time point, and again at 24 months and 36 months.

Subdomains on quality of life, emotional functioning, and social functioning were collected with the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) QLQ-C30 questionnaires and body image was collected by means of the breast cancer specific BR23 questionnaire [7]. Each subscale contains a different number of items to be scored, and each individual item was scored on a 4-point Likert scale (body image, emotional functioning, and social functioning) or 7-point Likert scale (global QoL). The scores for global QoL, body image, emotional functioning, and social functioning were calculated using the EORTC scoring manual. Total score of one subscale ranges from 1 to 100. A higher score indicates a better outcome.

PROs on depression were collected through the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS, Dutch translation) questionnaire [8]. HADS is a 14-item self-rating scale with seven questions to measure the symptoms of depression. Each question has four answer options, leading to a score between 0 and 3 for each question. Higher scores indicate a higher risk of depression. An increased risk of depressive disorders was defined as a HADS score ≥ 8. A Dutch reference population (n = 904), matched for age and gender, was used for the EORTC QLQ-C30 and HADS depression scores [9].

Clinical data including type of surgery, axillary treatment, tumor size, radiation therapy, and primary (neoadjuvant) or post-operative systemic treatment with hormonal therapy or chemotherapy were collected through the IKNL. Information on age, height, weight and smoking behavior, was collected within the UMBRELLA cohort through a bi-annual questionnaire. Age is defined as age upon inclusion. Smoking was classified as ‘yes’ when patients were active smokers during follow-up and ‘no’ for non-active smokers. Body mass index (BMI) scores were based on mean height (m) and weight (kg) during follow-up. BMI was calculated as weight/height2.

Statistics

Patient demographics and tumor and treatment characteristics were used to compare proportions, frequencies, and means with standard deviations between three groups of patients: satisfied, neutral, or dissatisfied with cosmetic outcome. Patient, treatment, and tumor characteristics of patients who responded to the cosmetic questionnaire were compared to those of patients who did not respond to the cosmetic questionnaire.

Changes in QoL, body image, emotional functioning, and social functioning between satisfied and dissatisfied patients were analyzed using a linear mixed-effect model to account for correlation between subjects over time. For mixed model analysis the self-reported cosmetic outcome was dichotomized into satisfied/neutral with cosmetic outcome and dissatisfied with cosmetic outcome. The model included a random intercept, a linear time effect, and time–cosmetic outcome interaction. We adjusted for potential confounders, i.e., age (continuous), type of surgery (lumpectomy vs. breast reconstruction), hormonal therapy, chemotherapy ± immunotherapy, BMI (≤ 25 vs. > 25), active smoking during follow-up, axillary treatment (sentinel node procedure vs. axillary lymph node procedure), radiation therapy (local vs. locoregional), and radiation therapy boost on the tumor bed. An autoregressive covariance structure of the first order was included, since it was assumed that measurements closer together in time were more correlated than measurements further apart [10].

Differences in proportions of high depression scores (a HADS-NL score ≥ 8) were compared between satisfied and dissatisfied patients, using a Chi -square test and Fisher’s exact test. A p- value < 0.05 was considered significant. Analyses were performed with Statistical Package for Social Sciences software (IBM SPSS Statistics version 23).

Results

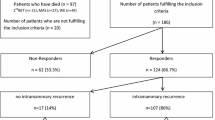

Between October 2013 and June 2018, 2140 patients were enrolled in the UMBRELLA cohort. Of those, 425 patients had a follow-up < 12 months, 292 patients had no clinical data available, 85 patients were treated with mastectomy without reconstruction, and 530 patients did not respond to the cosmetic questionnaire at 12 months (i.e. non-responders). These patients were excluded, resulting in 808 patients eligible for the present study (Fig. 1). Breast cancer treatment of women who responded to cosmetic questionnaires was comparable to that of patients who did not respond to cosmetic questionnaire (Table 1). There were more missing data on QoL, smoking, and BMI in non-responders in comparison to patients included in this study (respectively 41% vs. 10% and 55% vs 7%).

At 12 months, the proportion of satisfied, neutral, and dissatisfied patients was 72% (n = 584), 20% (n = 161), and 8% (n = 63), respectively (Table 2). The proportion of satisfied, neutral, and dissatisfied patients remained approximately stable over time. This proportion of dissatisfied patients was 8% (63/808), 7% (45/626), and 8% (31/409) after 1, 2, and 3 years of follow-up respectively (Table 3). Of the patients dissatisfied with cosmetic outcome at 24 months, 60% (27/45) was also dissatisfied at 12 months, whereas 40% (18/45) of patients who where previously satisfied with cosmetic outcome now were dissatisfied. At 36 months, 55% (17/31) patients were dissatisfied both at 12 months as well as at 36 months after inclusion.

The respective mean age at inclusion of satisfied, neutral, and dissatisfied patients was 58, 56, and 56 years. Of the patients satisfied at 12 months after inclusion, 97% (569/584) was treated with breast-conserving surgery. This was respectively 91% of the neutral patients (147/161) and 84% of dissatisfied patients (53/63). A larger proportion of dissatisfied patients was treated with chemotherapy in contrast to neutral and satisfied patients (respectively 51%, 45%, and 30%) as well as hormonal therapy (respectively 54%, 53%, and 43%). Also, 16% of the dissatisfied patients was treated with locoregional radiation therapy in contrast to 14% of the neutral and 7% of the satisfied patients. The proportion of satisfied, neutral, and dissatisfied patients was approximately equally distributed for radiation therapy boost, active smoking, and body mass index (respectively 49–52%, 10–12% and 48-60%).

Dissatisfied patients had lower levels of unadjusted QoL, body image, and social and emotional functioning compared to patients satisfied with cosmetic outcome (Fig. 2). Satisfied patients reported higher scores of global QoL in comparison to the reference population at all time-points. Social and emotional functioning of satisfied patients was comparable to that of the Dutch reference population. In contrast, dissatisfied patients reported poorer social and emotional functioning compared to the Dutch reference population during follow-up.

The crude levels of different domains of QoL in respect to cosmetic outcome and a matched Dutch reference non-cancer populationa. aA reference population for quality of life, emotional functioning, and social functioning was available. There is currently no reference population available for body image. Reference population included 907 women without breast cancer with comparable age to study population

After adjustment for potential confounders (i.e., age, type of surgery, chemotherapy, hormonal therapy, BMI, smoking, axillary treatment, and radiation therapy ± boost), dissatisfied patients reported significantly lower QoL at 12 and 36 months (mean difference (MD) 6.9, 95% CI 2.1–11.6 and MD 8.8, 95% CI 2.7–15.0) (Table 4). After 24 months, QoL was lower in dissatisfied than satisfied patients, however this difference was not significant (MD 3.4, 95% CI − 1.9–8.7). Dissatisfied patients had a worse body image compared to satisfied patients at 12, 24, and 36 months (MD 22.2, 95% CI 18.1–26.4; MD 20.6, 95% CI 16.0–25.1; and MD 20.3, 95% CI 15.6–25.0) (Table 4). Also, dissatisfied patients reported lower emotional functioning at 12, 24, and 36 months in comparison to satisfied patients (respectively MD 6.8, 95% CI 1.7–12.0; MD 7.9, 95% CI 2.3–13.5; and MD 8.2, 95% CI 1.2–15.3). Social functioning of dissatisfied patients in comparison to satisfied patients was significantly lower at 12 and 36 months (MD 8.4, 95% CI 3.3–13.5; MD 6.3, 95% CI 0.1–12.2). Although not statistically significant, social functioning of dissatisfied patients was lower in comparison to satisfied patients at 24 months (MD 5.4, 95% CI − 0.3–10.8). There was a significantly lower proportion of patients with symptoms suggestive of possible depression (i.e., with a HADS-NL score ≥ 8) among satisfied patients in comparison to dissatisfied patients after 12 and 24 months of follow-up (respectively 10% vs. 25% and 11% vs. 27%), in contrast to 14% in the Dutch reference population (Fig. 3). This was respectively 11% and 23% after 36 months of follow-up (not statistically significant).

Discussion

This prospective observational study showed that a stable proportion of 7–8% of breast cancer patients treated with breast-conserving treatment or mastectomy with immediate reconstruction were dissatisfied with respect to their cosmetic outcome up until 3 years after breast cancer treatment. Cosmetic dissatisfaction was independently associated with poorer global quality of life, body image, social functioning, and emotional functioning and a higher proportion of patients with moderate/severe depression scores.

Several other studies have described patient-reported cosmetic outcome after breast cancer treatment. In these studies, 8–20% of the patients were dissatisfied with their cosmetic outcome [11,12,13]. In the prospective trial of Garsa et al., 151 early-stage breast cancer patients treated with breast-conserving surgery and partial breast radiation therapy were included. The percentage of patients reporting excellent/good cosmetic outcome after respectively 3 months, 2, and 3 years after radiation therapy was 91%, 87%, and 92% [11]. Garsa et al. defined patient-reported cosmetic outcome as a combination of factors (i.e., breast size, nipple/areola location and shape, appearance of the surgical scar, breast shape, and skin color). In the older prospective study of Matory et al., 57 patients were treated with, as they described, partial mastectomy. Most patients were also treated with radiation therapy [12]. Cosmetic outcome was assessed by physical and photographic examination using a 4-point Likert scale with “no difference from contralateral breast,” “minimal difference from contralateral breast,” “moderate asymmetry,” and “gross distortion or asymmetry” representing respectively excellent, good, fair, and poor results. A good or excellent cosmetic result was reported by 80% (n = 50/57) of the patients after a median follow-up of 36 months, which was lower than the 93% which we found 3 years after treatment. This could be due to the fact that patients were treated with partial mastectomy. During a partial mastectomy larger tissue volume is removed in comparison to the breast-conserving surgery which is mostly performed nowadays. This can affect cosmetic outcome [14].

In accordance with the literature, we observed that younger patients were more likely to be dissatisfied with cosmetic outcome [15,16,17,18]. This might be because younger patients are more likely to receive mastectomy followed by reconstruction, resulting in a greater risk of dissatisfaction [15]. Another explanation may be that younger women are more demanding and sensitive regarding their physical appearance [16,17,18]. The use of tamoxifen is associated with the development of fibrosis, which might induce poorer cosmetic outcome [19, 20]. In the present study, hormonal treatment was observed more frequently in patients dissatisfied with cosmetic outcome than satisfied patients with cosmetic outcome. However, no distinction between the type of hormonal therapy was made, since data on type of hormonal therapy was often unknown. We found that axillary lymph node dissection impacted the cosmetic outcome which has been described previously. It is known that extensive axillary treatment like axillary lymph node dissection can be associated with the risk of developing lymphedema and therefore can influence the healing of the breast tissue after surgery and radiation therapy [21,22,23]. Results of this study also indicated that more extensive radiation therapy (i.e., locoregional radiation therapy) and type of surgery (i.e., mastectomy with immediate reconstruction) impair cosmetic outcome. Other studies showed that satisfaction with cosmetic outcome in patients treated with breast-conserving therapy depends on the amount of tissue excised during surgery, with a larger amount of tissue excised resulting in a lower level of satisfaction [14, 19, 24,25,26,27]. The higher proportion of dissatisfied patients in comparison to the neutral and satisfied patients treated with locoregional radiation therapy could be explained by the increased risk of fibrosis due to radiation therapy of the breast tissue even years after the start of radiation therapy, as the administration of an additional radiation therapy boost was distributed equally in local and locoregional treated patients [19, 28,29,30,31,32]. In the “boost vs. no boost” trial, 5318 early-stage breast cancer patients were randomized to additional boost on the tumor bed or no further treatment [19]. An independent association between radiation therapy boost and poorer cosmetic outcome was seen after 3 years follow-up. In our study, the proportion of patients treated with radiation therapy boost was approximately equally distributed amongst the satisfied, neutral, and satisfied patients. However, this was only evaluated at 1 year follow-up. Breast and chest wall fibrosis develop over the course of many years and our cohort may not be mature enough to assess the impact of radiation therapy boost. In contrast to other studies, smoking and BMI had no influence on cosmetic outcome in the present study.

We aimed to assess the impact of cosmetic (dis)satisfaction on the different domains of quality of life and found a strong association between the two. Since self-reported cosmetic outcome and quality of life and depression scores were measured simultaneously, we do not know the direction of the association. It could be that dissatisfaction with cosmetic outcome causes higher depression scores and lower quality of life. However, the contrary—higher depression scores or lower quality of life causing dissatisfaction with cosmetic outcome—may also be the case.

Previously, only the impact of cosmetic outcome on global quality of life or body image was assessed. Hau et al. evaluated the association between global quality of life and cosmetic outcome in 688 breast cancer patients treated with post-operative radiation therapy after breast-conserving surgery, using the EORTC QLQ-C30 [33]. Patient-reported cosmetic outcome was dichotomized into good/excellent vs. fair/poor. Prior to radiation therapy, at 5 and 10 years follow-up, patients dissatisfied with cosmetic outcome reported a significantly lower global QoL score than satisfied patients (differences of 6.3, 9.6, and 7.3 points respectively on EORTC QLQ-C30). These results are comparable with our results.

After adjustment for patient and treatment related factors, patients satisfied with cosmetic outcome had similar emotional and social functioning in comparison to a Dutch reference non-cancer, female population during 3 years follow-up. Also, a smaller proportion of satisfied patients reported higher HADS scores in comparison to the Dutch reference population. Dissatisfied patients however, scored worse on all domains. Dissatisfaction with cosmetic appearance could be influenced by expectations of the cosmetic result after surgery [34, 35]. Therefore, managing patients’ expectations and providing information about cosmetic results of patients with similar characteristics and expectations seems important, possibly by early referral to a plastic surgeon.

Our study suffers from some limitations. There were 530 patients who did not respond to the cosmetic questionnaire. Even though there were no differences in patient and treatment characteristics, we may have over- or underestimated the proportion of dissatisfied participants. Also, we cannot rule out that the association between cosmetic outcome and quality of life was distorted: it may, for example, have been stronger, when cosmetically dissatisfied women with (very) low quality of life scores were more likely to be non-responders. In the present study, smoking was defined as active smoking during follow-up. Information on the number of pack years and the start date of smoking was not available. Therefore, the impact these factors could have had on the cosmetic outcome, could not be taken into account. Breast size prior to surgery, post-operative complications such as infection and seroma, and tumor localization within the breast are known to be risk factors for poor cosmetic outcome [13, 15, 22, 36]. These patient characteristics were not collected within the cohort. Also, the cosmetic evaluation questionnaire was only sent to patients 12, 24, and 36 months after inclusion. Consequently, we miss information on the satisfaction with cosmetic outcome shortly after surgery or prior to breast cancer treatment.

Nonetheless, this study provides insights into the longitudinal patient satisfaction with cosmetics after breast cancer and breast cancer treatment. Outcomes from this study emphasizes the importance of post-treatment care of breast cancer patients and shared decision making prior to breast cancer treatment.

Conclusion

In conclusion, dissatisfaction with cosmetic outcome in the first 3 years after breast surgery and post-operative radiation therapy is low, i.e., 7–8%. As cosmetic outcome was associated with reduced quality of life, poorer body image, reduced social and emotional functioning, and increased depressive symptom scores, counseling on the impact of satisfaction with cosmetic outcome on the quality of life could be considered.

Abbreviations

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- DCIS:

-

Ductal carcinoma in situ

- EORTC:

-

European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer

- HADS:

-

Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale

- IKNL:

-

The Netherlands Comprehensive Cancer Organization

- PROs:

-

Patient reported outcome(s)

- QoL:

-

Quality of life

- UMBRELLA:

-

Utrecht cohort for Multiple BREast cancer intervention studies and Long-term evaLuAtion

References

Netherlands Cancer Registry [Internet] (2018) www.cijfersoverkanker.nl. Accessed 20 May 2018

Verdial FC, Etzioni R, Duggan C, Anderson BO (2017) Demographic changes in breast cancer incidence, stage at diagnosis and age associated with population-based mammographic screening. J Surg Oncol 115(5):517–522

Veronesi U, Cascinelli N, Mariani L, Greco M, Saccozzi R, Luini A et al (2002) Twenty-year follow-up of a randomized study comparing breast-conserving surgery with radical mastectomy for early breast cancer. N Engl J Med 347(16):1227–1232

Darby S, McGale P, Correa C, Taylor C, Arriagada R, Clarke M et al (2011) Effect of radiotherapy after breast-conserving surgery on 10-year recurrence and 15-year breast cancer death: meta-analysis of individual patient data for 10,801 women in 17 randomised trials. Lancet (London, England) 378(9804):1707–1716

Young-Afat DA, van Gils CH, van den Bongard HJGD, Verkooijen HM (2017) The Utrecht cohort for Multiple BREast cancer intervention studies and Long-term evaLuAtion (UMBRELLA): objectives, design, and baseline results. Breast Cancer Res Treat 164(2):445–450

Sneeuw KC, Aaronson NK, Yarnold JR, Broderick M, Regan J, Ross G et al (1992) Cosmetic and functional outcomes of breast conserving treatment for early stage breast cancer. 1. Comparison of patients’ ratings, observers’ ratings and objective assessments. Radiother Oncol 25(3):160–166

Aaronson NK, Ahmedzai S, Bergman B, Bullinger M, Cull A, Duez NJ et al (1993) The European organization for research and treatment of cancer QLQ-C30: a quality-of-life instrument for use in international clinical trials in oncology. J Natl Cancer Inst 85(5):365–376

Spinhoven P, Ormel J, Sloekers PP, Kempen GI, Speckens AE, Van Hemert AM (1997) A validation study of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) in different groups of Dutch subjects. Psychol Med 27(2):363–370

van de Poll-Franse LV, Horevoorts N, van Eenbergen M, Denollet J, Roukema JA, Aaronson NK et al (2011) The Patient Reported Outcomes Following Initial treatment and Long term Evaluation of Survivorship registry: scope, rationale and design of an infrastructure for the study of physical and psychosocial outcomes in cancer survivorship cohorts. Eur J Cancer 47(14):2188–2194

Bonnetain F, Fiteni F, Efficace F, Anota A (2016) Statistical challenges in the analysis of health-related quality of life in cancer clinical trials. J Clin Oncol 34:1953–1956

Garsa AA, Ferraro DJ, DeWees T, Margenthaler JA, Naughton M, Aft R et al (2013) Cosmetic analysis following breast-conserving surgery and adjuvant high-dose-rate interstitial brachytherapy for early-stage breast cancer: a prospective clinical study. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 85(4):965–970

Matory WEJ, Wertheimer M, Fitzgerald TJ, Walton RL, Love S, Matory WE (1990) Aesthetic results following partial mastectomy and radiation therapy. Plast Reconstr Surg 85(5):739–746

Fujishiro S, Mitsumori M, Kokubo M, Nagata Y, Sasai K, Mise K et al (2000) Cosmetic results and complications after breast conserving therapy for early breast cancer. Breast Cancer 7(1):57–63

Immink JM, Putter H, Bartelink H, Cardoso JS, Cardoso MJ, van der Hulst-Vijgen MHV et al (2012) Long-term cosmetic changes after breast-conserving treatment of patients with stage I-II breast cancer and included in the EORTC “boost versus no boost” trial. Ann Oncol Off J Eur Soc Med Oncol 23(10):2591–2598

Wang HT, Barone CM, Steigelman MB, Kahlenberg M, Rousseau D, Berger J et al (2008) Aesthetic outcomes in breast conservation therapy. Aesthetic Surg J 28(2):165–170

Montazeri A, Vahdaninia M, Harirchi I, Ebrahimi M, Khaleghi F, Jarvandi S (2008) Quality of life in patients with breast cancer before and after diagnosis: an eighteen months follow-up study. BMC Cancer 8:1–6

Avis NE, Crawford S, Manuel J (2005) Quality of life among younger women with breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 23(15):3322–3330

Champion VL, Wagner LI, Monahan PO, Daggy J, Smith L, Cohee A et al (2014) Comparison of younger and older breast cancer survivors and age-matched controls on specific and overall quality of life domains. Cancer 120(15):2237–2246

Vrieling C, Collette L, Fourquet A, Hoogenraad WJ, Horiot JH, Jager JJ et al (2000) The influence of patient, tumor and treatment factors on the cosmetic results after breast-conserving therapy in the EORTC “boost vs. no boost” trial. EORTC Radiotherapy and Breast Cancer Cooperative Groups. Radiother Oncol 55(3):219–232

Johansen J, Overgaard J, Overgaard M (2007) Effect of adjuvant systemic treatment on cosmetic outcome and late normal-tissue reactions after breast conservation. Acta Oncol 46(4):525–533

Fabry HFJ, Zonderhuis BM, Meijer S, Berkhof J, Van Leeuwen PAM, Van der Sijp JRM (2005) Cosmetic outcome of breast conserving therapy after sentinel node biopsy versus axillary lymph node dissection. Breast Cancer Res Treat 92(2):157–162

Hennigs A, Hartmann B, Rauch G, Golatta M, Tabatabai P, Domschke C et al (2015) Long-term objective esthetic outcome after breast-conserving therapy. Breast Cancer Res Treat 153(2):345–351

Mills JM, Schultz DJ, Solin LJ (1997) Preservation of cosmesis with low complication risk after conservative surgery and radiotherapy for ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 39(3):637–641

Cochrane RA, Valasiadou P, Wilson ARM, Al-Ghazal SK, Macmillan RD (2003) Cosmesis and satisfaction after breast-conserving surgery correlates with the percentage of breast volume excised. Br J Surg 90(12):1505–1509

Vicini F, Beitsch P, Quiet C, Gittleman M, Zannis V, Fine R et al (2011) Five-year analysis of treatment efficacy and cosmesis by the American Society of Breast Surgeons MammoSite Breast Brachytherapy Registry Trial in patients treated with accelerated partial breast irradiation. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 79(3):808–817

Tenea Cojan TS, Vidrighin CD, Ciobanu M, Paun I, Teodorescu M, Mogos G et al (2012) Breast-conserving surgery in breast cancer. Chirurgia (Bucur) 107(5):616–625

Kim MK, Kim T, Moon HG, Jin US, Kim K, Kim J et al (2015) Effect of cosmetic outcome on quality of life after breast cancer surgery. Eur J Surg Oncol 41(3):426–432

Borger JH, Kemperman H, Smitt HS, Hart A, van Dongen J, Lebesque J et al (1994) Dose and volume effects on fibrosis after breast conservation therapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 30(5):1073–1081

Kelemen G, Varga Z, Lazar G, Thurzo L, Kahan Z (2012) Cosmetic outcome 1-5 years after breast conservative surgery, irradiation and systemic therapy. Pathol Oncol Res 18(2):421–427

Lyngholm CD, Christiansen PM, Damsgaard TE, Overgaard J (2013) Long-term follow-up of late morbidity, cosmetic outcome and body image after breast conserving therapy. A study from the Danish Breast Cancer Cooperative Group (DBCG). Acta Oncol 52(2):259–269

Munshi A, Kakkar S, Bhutani R, Jalali R, Budrukkar A, Dinshaw KA (2009) Factors influencing cosmetic outcome in breast conservation factors affecting cosmesis in breast. Clin Oncol 21(4):285–293. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clon.2009.02.001

Shiina N, Sakakibara M, Fujisaki K, Iwase T, Nagashima T, Sangai T et al (2016) Volumetric breast density is essential for predicting cosmetic outcome at the late stage after breast-conserving surgery. Eur J Surg Oncol 42(4):481–488

Hau E, Browne L, Capp A, Delaney GP, Fox C, Graham PH (2013) The impact of breast cosmetic and functional outcomes on quality of life : long-term results from the St. George and Wollongong randomized breast boost trial. Breast Cancer Res Treat 139:115–123

Contant CME, Menke-Pluijmers MBE, Seynaeve C, Meijers-Heijboer EJ, Klijn JGM, Verhoog LC et al (2002) Clinical experience of prophylactic mastectomy followed by immediate breast reconstruction in women at hereditary risk of breast cancer (HB(O)C) or a proven BRCA1 and BRCA2 germ-line mutation. Eur J Surg Oncol 28(6):627–632

Bresser PJC, Seynaeve C, Van Gool AR, Brekelmans CT, Meijers-Heijboer H, van Geel AN et al (2006) Satisfaction with prophylactic mastectomy and breast reconstruction in genetically predisposed women. Plast Reconstr Surg 117(6):1674–1675

Olfatbakhsh A, Mehrdad N, Ebrahimi M, Alavi N, Hashemi E, Kaviani A et al (2015) Evaluation of factors impacting cosmetic outcome of breast conservative surgery—a study in Iran. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 16(6):2203–2207

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

All authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in this study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Research involving human and animal participants

This article does not contain any studies with animals performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained form all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Batenburg, M.C.T., Gregorowitsch, M.L., Maarse, W. et al. Patient-reported cosmetic satisfaction and the long-term association with quality of life in irradiated breast cancer patients. Breast Cancer Res Treat 179, 479–489 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-019-05470-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-019-05470-y