Abstract

We investigate by means of direct numerical simulation how large-scale circulations produce deviations from Monin–Obukhov similarity theory (MOST) in the limit of free convection, disentangling the role of large-scale downdrafts from updrafts using conditional analysis. We compare the convective boundary layer to two other free-convective flows: Rayleigh–Bénard convection with an adiabatic top lid and classical Rayleigh–Bénard convection. This serves a dual purpose: firstly, to ascertain how changes in the upper boundary conditions and thereby in the large-scale circulations modify the near-surface behaviour and secondly, to assess to what extent we can extrapolate results from idealized systems to the unstable atmospheric surface layer. Using a low-pass filter to define the large scales we find that, whilst deviations from MOST occur within large-scale downdraft regions, strong deviations also occur within large-scale updraft regions. The deviations within updrafts are independent of the filter length scale used to define the large-scale circulations, independent of whether updrafts are defined as ascending air, or as air that is both ascending and positively buoyant, and are not due to changes with height of the updraft area fraction. This suggests that even updraft properties are not just determined locally, but also by outer scales. Cold, strong downdrafts in classical Rayleigh–Bénard convection notably modify the near-surface behaviour compared to the other two systems. For the moderate Reynolds numbers considered, Rayleigh–Bénard convection with an adiabatic top lid thus seems more appropriate than classical Rayleigh–Bénard convection for studying the unstable atmospheric surface layer in the limit of free convection.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Much of our understanding of the atmospheric surface layer (ASL) has its roots in Monin–Obukhov similarity theory (MOST), which assumes that all flow properties in the ASL depend only on the friction velocity, the surface buoyancy flux and the height above the ground (Monin and Obukhov 1954). In the limit of free convection, the friction velocity goes to zero and the only remaining scaling parameters are height, z, and the surface buoyancy flux. Through dimensional analysis, MOST asserts that under free-convective conditions, the nth-order moment of the velocity is proportional to \(z^{n/3}\) whilst the nth-order moment of the buoyancy is proportional to \(z^{-n/3}\) (Prandtl 1932; Priestley 1954).

A key assumption in MOST is that surface-layer properties are determined locally, with no influence from the outer layer. On the whole, early work has provided empirical support for MOST under near-neutral (i.e., weakly stable or weakly unstable) conditions (Wyngaard et al. 1971; Kaimal et al. 1976). However, under strongly unstable and free-convective conditions, measurements of the root-mean-square (r.m.s.) of the buoyancy fluctuations indicate power laws with exponents in the range [\(-\,0.5\), \(-\,0.3\)] (Adrian 1996; Mellado et al. 2016; Maronga and Reuder 2017), whilst both a power law and a logarithmic law support measurements of the vertical velocity r.m.s. equally well (Adrian 1996; Khanna and Brasseur 1997; Mellado et al. 2016). These deviations from the predicted scaling laws are known to result from the interaction with large-scale circulations (LSCs), defined as persistent circulatory structures in the velocity field that extend across the whole boundary layer in convectively-driven systems (Chillà and Schumacher 2012; Mellado et al. 2016; Salesky and Anderson 2018). Still, there is conflict about the mechanisms by which LSCs introduce non-local effects to the surface layer.

One proposed mechanism involves wind shear induced by the LSCs that may alter scaling laws in the surface layer, since wind shear is not accounted for by MOST in free convection (Kraichnan 1962; Businger et al. 1971; Businger 1973). Another proposed mechanism is that large-scale downdrafts introduce non-local properties to the surface layer by transporting free-tropospheric air down to the surface (de Bruin et al. 1993; Lohou et al. 2010; van de Boer et al. 2014). The shear mechanism has been widely discussed, not only in the context of the atmospheric boundary layer (ABL), but also in studies of Rayleigh–Bénard convection, where it is supposed that LSCs induce the laminar boundary layer to become turbulent and thereby modify scaling laws near the surface at a sufficiently high Rayleigh number (van Reeuwijk et al. 2008; Shishkina et al. 2015; du Puits and Willert 2016). This possibility is an on-going source of debate and here we choose to focus on the downdraft mechanism, which has been less studied and where we are able to isolate the role of downdrafts using conditional analysis.

Since downdrafts occupy a significant area fraction near the surface, we hypothesize that when conventional statistics are taken, downdrafts mask the behaviour inside large-scale updraft regions, where, conversely, properties are postulated to follow the predicted scaling laws more closely. This hypothesis stems from an understanding of updrafts as being formed from buoyant thermals rising from the surface and merging together (Schmidt and Schumann 1989; Mellado et al. 2016). From that point of view, it seems reasonable to suppose that updraft properties are characterized by a local length scale (the height above the ground) and the surface buoyancy flux, in agreement with MOST. A decomposition into large-scale updraft and downdraft regions thus has the potential to not only elucidate the mechanisms producing deviations from MOST, but also simplify scaling laws in the free-convective regime to a combination of the MOST prediction, representing the updraft contribution, plus a scaling law for the downdraft contribution based on outer scales.

Using conditional analysis, differences between updraft and downdraft properties have previously been found in the bulk of the convective boundary layer (CBL—Young 1988; Schumann and Moeng 1991; Siebesma et al. 2007) and in the cloud layer (Siebesma and Cuijpers 1995; Park et al. 2016). Here we extend this analysis into the surface layer by means of direct numerical simulation (DNS). Although restricted to moderate Reynolds numbers, DNS is an appropriate tool for investigations into the ABL, allowing detailed study of the full range of turbulence scales in relatively large-aspect-ratio domains, without the uncertainty associated with subgrid-scale modelling (Mellado et al. 2018). With the exception of Mellado et al. (2016), DNS studies of the ASL dealing explicitly with MOST have tended to focus on stable (Chung and Matheou 2012; Shah and Bou-Zeid 2014; Ansorge and Mellado 2014) or mildly unstable (McColl et al. 2017; Li et al. 2018) conditions. This further motivates our consideration of the free-convective case.

One question that we also address is the extent to which classical Rayleigh–Bénard convection constitutes a good model of the CBL. Both configurations share commonalities. For example, the LSCs occurring in both systems closely resemble one another (Schmidt and Schumann 1989) and the scaling of the Nusselt number with the Rayleigh number is the same in both systems (Mellado et al. 2016). These commonalities indicate a potential for results from Rayleigh–Bénard convection to be extrapolated to the ABL, but it is unclear how suitable Rayleigh–Bénard convection is for this purpose because differences in the upper boundary conditions between the two systems modify the LSCs, which in turn may affect surface-layer properties. To address this issue, we compare three configurations: the CBL, Rayleigh–Bénard convection with an adiabatic top lid (LID) and classical Rayleigh–Bénard convection (RBC). The LID case acts as an intermediary step between the warm entrainment zone of the CBL and the cooled upper plate of Rayleigh–Bénard convection (Sorbjan 1996) and allows us to systematically explore how changes in the upper boundary conditions and the large scales affect the near-surface region. We can also thereby assess to what extent idealized configurations such as the LID case, or the more commonly studied RBC case, are representative of the unstable ASL.

Although the CBL, LID and RBC cases have previously been compared in studies by Adrian et al. (1986) and Moeng and Rottuno (1990), only the former study addressed the validity of MOST and concentrated on the LID case in that context. By comparing the three systems using laboratory experiments and atmospheric measurements, Adrian et al. (1986) concluded that all three systems are similar in many respects in the lower half. Here, by using DNS to focus on the surface layer, we show that the LID case provides a better model of the CBL than does the RBC case.

This paper is structured as follows: in Sect. 2, we detail the numerical procedure and provide a dimensional analysis of the problem that allows us to appropriately compare the three configurations. In Sect. 3, we explain our conditioning methods, present results from the conditional analysis and consider how the results depend on our definition of “large scale”. Conclusions are given in Sect. 4.

2 Formulation

2.1 Governing Equations

All three configurations considered are governed by the Navier–Stokes equations under the Boussinesq approximation,

where \(\pmb {v}(\pmb {x},t)\) is the velocity vector with components (u, v, w), \(\pmb {x}\) is the position vector with horizontal coordinates x and y, and vertical coordinate z, t is time and \(\mathbf {k}=(0,0,1)\) is the unit vector in the vertical direction. The variable p is the pressure divided by a constant reference density and b is the buoyancy (which can be related to, e.g., the virtual potential temperature \(\theta _v\) via \(b=g(\theta _v-\theta _{v,0})/\theta _{v,0}\), where \(\theta _{v,0}\) is a reference value and g is the acceleration due to gravity). The parameters \(\nu \) and \(\kappa \) are the kinematic viscosity and the thermal diffusivity respectively.

The variable \(\chi \) is a top-down scalar. This top-down scalar is a passive scalar that can be considered as a reference non-dimensional moisture field that, in combination with b, can be used to reconstruct several moisture statistics (Mellado et al. 2017). Here we use it to better interpret the behaviour within downdrafts, since \(\chi \) has no forcing at the surface whereas b does.

2.2 Boundary Conditions

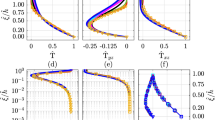

a–c Schematics of the three free-convective systems. d–f Profiles of (cyan) the mean buoyancy, (orange) the mean top-down scalar, (green) the turbulent buoyancy flux, and (purple) the turbulent top-down scalar flux. Note that in the CBL case, only heights up to 1.2h are shown, but the full vertical domain extends up to 4.2h. Symbols used in this figure are defined in Table 1

All simulations have periodic lateral boundary conditions and are statistically homogeneous in the horizontal directions. The surface is aerodynamically smooth. The boundary conditions at the surface are no penetration, no-slip on the velocity and Neumann on the scalars, such that a constant surface buoyancy flux is maintained,

and a zero surface flux is maintained for the top-down scalar,

The three configurations differ in their upper boundary conditions, illustrated schematically in terms of some key properties in Fig. 1 (symbols used are explained in Table 1). In the CBL case, the initial buoyancy field increases linearly with height as \(N^2z\), where N is the buoyancy frequency in the free troposphere. The top-down scalar initially decreases with height as \(-\gamma _\chi z\), where \(\gamma _\chi \) is the lapse rate of \(\chi \) in the free troposphere. The turbulent boundary layer that forms adjacent to the surface continuously penetrates into this linearly stratified fluid layer. At the top of the computational domain, which is placed far enough away such that it does not affect the turbulent boundary layer (see Garcia and Mellado 2014 for a sensitivity study), a Neumann boundary condition is applied on the scalars, maintaining a constant buoyancy flux, \(F_{b,\mathrm {t}}=-\kappa N^2\), and constant top-down scalar flux, \(F_{\chi ,\mathrm {t}}=\kappa \gamma _\chi \). An impenetrable, free-slip condition is used for the velocity. The upper 25% of the computational domain contains a sponge layer, which relaxes all profiles back to their initial state, so as to prevent the reflection of gravity waves. After an initial phase of unsteady development, the CBL reaches a quasi-steady state in which the growth of the CBL is slow compared to the turnover time of the LSCs. For present purposes, we focus on this quasi-steady state.

In the LID case, the upper boundary condition on the velocity is no-penetration, no-slip and on the buoyancy, zero flux is maintained, rendering the top lid adiabatic. The top-down scalar has a constant flux at the upper plate. The LID case may be interpreted as a CBL with infinitely strong stratification. The adiabatic upper plate prevents any heat from escaping and the fluid thus constantly warms over time, but because the depth of the fluid layer does not change, many properties do reach a statistically steady state (Sorbjan 1996).

In the RBC case, the same upper boundary conditions as in the LID case are used for the velocity and top-down scalar, but for the buoyancy, the flux at the upper plate is equal to that at the surface and the system is thus statistically steady for velocity and buoyancy properties.

It is worth commenting here on the role of the boundary conditions in determining the relative importance of the top-down and bottom-up contributions to the buoyancy field. In the RBC and CBL cases, the buoyancy is both bottom-up and top-down. In the RBC case, the bottom-up and top-down contributions are equal, since the surface flux equals the flux at the top plate. In the CBL case, the bottom-up contribution dominates as the magnitude of the entrainment flux is around 10% of the surface flux (Garcia and Mellado 2014). In the LID case, the buoyancy is purely bottom-up, as the flux at the top plate is zero, and the LID case thereby acts as a limit in which the influence of downdrafts on the buoyancy near the surface is minimized.

2.3 Dimensional Analysis

In order to define reference scalar fluxes, we approximate the flux of a scalar \(\phi \), \(F_\phi = \langle \phi ^\prime w^\prime \rangle -\kappa \partial \phi /\partial z\), as varying linearly with height from the surface to \(z=h\) (see Fig. 1) and take the integral over this linear approximation

For the buoyancy, Eq. 4 evaluates to

where in the CBL, we have neglected \(F_b|_{z=h}\) since \(-F_b|_{z=h}/F_{b,\mathrm {s}}\approx 0.12\) (Garcia and Mellado 2014). For the top-down scalar, Eq. 4 evaluates to

where in the CBL, we have taken into account the entrainment flux of \(\chi \) at the CBL top, which is estimated by the product of a passive scalar scale, \(\gamma _\chi L_0\), and a velocity scale, \(L_0 N\), where

is the reference Ozmidov length that characterizes the thickness of the entrainment zone at the top of the CBL (Mellado et al. 2017). We note that the entrainment flux in the CBL is not a control parameter, but an outcome of the flow.

2.3.1 Convective Scales

Once the flow is fully turbulent and the details of the initial conditions have been sufficiently forgotten, statistical properties in the CBL case depend only on the control parameters \(\{F_{b,0},N,\nu ,\kappa \}\) and the independent variables z and t, whilst in the non-penetrative RBC and LID cases, the control parameters are \(\{F_{b,0},h,\nu ,\kappa \}\) and the independent variable is z. The outer length scale, h, is equal to the depth of the Rayleigh–Bénard cell and in the CBL it is a measure of the boundary-layer depth, which may be defined in numerous ways, though all are commensurate with one another (Garcia and Mellado 2014). Here, we define the top of the CBL as the point of maximum mean buoyancy gradient away from the surface (see Fig. 2). Unlike the non-penetrative cases, where the depth of the cell is a control parameter, the CBL depth increases in time.

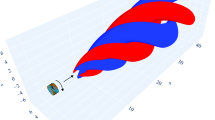

Logarithm of the magnitude of the buoyancy gradient in each system. The dashed white line in panel a shows the depth of the CBL, h. The full width of the domain is shown, giving an aspect ratio of 11. The solid horizontal white lines show the LSC width as determined from the wavelength of the peak in the azimuthally integrated two-dimensional cospectrum between buoyancy and vertical velocity (see Table 2)

Each system has four control parameters and two fundamental dimensions; length and time. Dimensional analysis thus dictates that each system is governed by two non-dimensional parameters: the Reynolds number (or the Rayleigh number) and the Prandtl number, \({Pr}= \nu /\kappa \). We fix \({Pr}\) to be equal to one in all our simulations, leaving the Reynolds (or Rayleigh) number as the only non-dimensional control parameter.

The form of the Reynolds number depends on the choice of control parameters used for non-dimensionalization. By choosing \(\{F_{b,0},h\}\) in the LID and RBC cases, one finds the following convective Reynolds number, \(Re_*\), and related convective Rayleigh number, \(Ra_*\),

where \(w_*\) in Eq. 8a is an outer (or convective) velocity scale defined as (Deardorff 1970a, b),

In the CBL case, by choosing \(\{F_{b,0},N\}\) to non-dimensionalize the system, one finds the reference Reynolds number, \(Re_0 \equiv L_0(L_0N)/\nu = F_{b,0}/(\nu N^2)\), as a control parameter. In addition, the CBL case depends on the non-dimensional time variable Nt. The reference Reynolds number employs the length scale \(L_0\) (Eq. 7) and the velocity scale \(L_0N\). The effect of \(Re_0\) near the surface can be neglected as a first approximation once the CBL is in the quasi-steady regime considered here, as near-surface statistics only depend weakly on \(Re_0\) (Mellado et al. 2016). Without loss of generality, the dependence on time can be expressed in terms of the dependence on \(Re_*\) (or \(Ra_*\)) defined in Eq. 8 because the CBL depth, h, acts as a proxy time variable. Hence, the statistics of the three systems, CBL, LID and RBC, can be expressed solely as functions of \(Re_*\) (or \(Ra_*\)) and normalized height, z / h. We match \(Re_*\) in all three of our systems, such that \(Re_* = 3258\) and \(Ra_* = 3.5 \times 10^{10}\).

Using outer length and velocity scales allows us to define a convective turnover time, \(t_*\),

To remove the initial transient, we reject all data up to \(h\approx 6.8L_0\) in the CBL case and up to \(t\approx 12t_*\) in the non-penetrative cases. In order to improve statistical convergence, all statistics are then averaged over a period \(t\approx 6t_*\) in the CBL case, and over \(t\approx 16t_*\) in the non-penetrative cases. A shorter averaging time must be used in the CBL case so that \(Re_*\) does not change significantly as the CBL grows. The non-penetrative cases thus have the advantage that greater statistical convergence can be achieved through long time averaging.

2.3.2 Free-Fall Scales

If instead of \(F_{b,0}\), one employs \(\Delta b\), the mean buoyancy difference across the convective region (defined as the region of positive turbulent buoyancy flux), one finds the free-fall Reynolds and Rayleigh numbers,

In Eq. 11a, the free-fall velocity scale, \(w_{\mathrm {f}}\) is

Because we use a Neumann boundary condition on the buoyancy, \(\Delta b\) is not a control parameter and has to be obtained from the simulations, but within statistical convergence it is steady in the non-penetrative cases and quasi-steady in the CBL case. Mean values of \(Re_{\mathrm {f}}\) and \(Ra_{\mathrm {f}}\) are \(\sim 10^4\) and \(10^8\) respectively in all simulations (see Table 2). Employing h and \(w_{\mathrm {f}}\) allows us to construct the free-fall time,

In terms of \(t_{\mathrm {f}}\), statistics are averaged over a period \(t\approx 33t_{\mathrm {f}}\) in the CBL case and over \(t\approx 93t_{\mathrm {f}}\) in the non-penetrative cases.

2.3.3 Diffusive Scales

Using the parameters \(F_{b,\mathrm {s}}\) and \(\kappa \), one can define diffusive length, velocity and buoyancy scales as

Diffusive scales characterize the region of the boundary layer where the molecular diffusion of heat is equally or more important than the turbulent flux (Townsend 1959). For flow over an aerodynamically smooth surface, this region is known as the diffusive layer and extends up to around 10\(z_\kappa \) (Mellado 2012). Because we match \(Re_*\) in all three of our systems, given Eqs. 5, 8a and 14a, the scale separation in terms of the diffusive length scale, \(h/z_\kappa \), is a factor of \(2^{1/4}\) less in the RBC case than in the LID and CBL cases. However, in terms of the Kolmogorov length, \(\eta = (\nu ^3/\epsilon )^{1/4}\), where \(\epsilon \) is the viscous dissipation rate of the turbulence kinetic energy (TKE), the scale separation, \(h/\eta \), is similar in all three configurations.

The surface layer comprises both the diffusive layer and a region above in which MOST predicts distinct scaling laws to hold, though as discussed in Sect. 1 the true scaling laws are uncertain. This region above the diffusive layer is the region of interest in this study, but a precise definition of its depth is elusive. Typically, the ASL depth is taken to be 0.1h, which, for the Reynolds numbers considered here, is equivalent to \(43z_\kappa \) in the LID and CBL cases and \(36z_\kappa \) in the RBC case. However, an equally valid definition is the depth over which scaling laws hold. This is found to be of order 0.1 of the LSC width (Mellado et al. 2016), which is defined here as the wavelength of the maximum in the azimuthally integrated two-dimensional cospectrum between b and w. Consistent with Mellado et al. (2016) and Pandey et al. (2018), we find that \(\lambda _{\mathrm {LSC}}/h\) is around twice as large in the RBC case compared to the CBL case (Fig. 2; Table 2). Other plausible definitions of the LSC width, for example based on the peak in the vertical velocity spectrum, yield similar results (Mellado et al. 2016). Based on the magnitudes of \(\lambda _{\mathrm {LSC}}/h\) given in Table 2, the region of the ASL on which we focus is \(10z_\kappa \lesssim z \lesssim 100z_\kappa \) in all cases.

2.4 Numerical Method, Resolution Requirements and Domain Size

The governing equations are discretized on a structured grid using sixth-order, spectral-like compact finite differences (Lele 1992) and integrated in time using a low-storage, fourth-order Runge–Kutta scheme (Carpenter and Kennedy 1994). The divergence-free condition, Eq. 1b, is maintained by performing a Fourier decomposition of the Poisson equation for the pressure in the periodic, horizontal directions and factorizing the resulting set of equations in the vertical direction (Mellado and Ansorge 2012). The grid is uniform and isotropic in most of the domain. Stretching is used to increase the vertical resolution near the walls in all cases, as well as to increase the domain depth in the CBL case.

The grid spacings are chosen according to previous studies of the resolution requirements for convection-driven flows (Shishkina et al. 2010; Mellado 2012; Garcia and Mellado 2014). The ratio of the vertical grid spacing, \(\Delta z\), to the Kolmogorov length is \(\Delta z/\eta \lesssim 1.5\) everywhere, which is sufficient for statistical properties of interest to depend less than 5% on the grid spacing. The vertical resolution near the walls in the non-penetrative RBC and LID cases is increased to \(\Delta z/\eta \lesssim 0.9\) compared to \(\Delta z/\eta \lesssim 1.1\) in the CBL case near the surface. This increase in resolution is necessary because the maximum value of the turbulent Reynolds number,

where e is the TKE, is reached near the upper wall in the LID case and near both walls in the RBC case and is at least three times larger in the non-penetrative cases than in the CBL case (see Table 2). This is due to vigorous plume impingement and strong horizontal velocity fluctuations in the non-penetrative cases, resulting in greater TKE than in the CBL case where the large-scale horizontal motion is weaker (despite the convective Reynolds number being the same in the three systems).

The aspect ratio, \(\varGamma \), defined as the ratio between the width of the domain and h, is equal to 11 in all three cases, which is at least twice as large as the typical LSC width (Table 2). We verified that the domain size does not restrict the horizontal extent of the LSCs by performing simulations with a smaller aspect ratio of \(\varGamma \approx 6.7\) and obtained similar results to the larger-aspect-ratio simulations (not shown).

3 Conditional Analysis

In this section, we will look at how statistical properties of the flow behave within large-scale updraft and downdraft regions. In order to do this, a large-scale field first needs to be defined. The conditioned statistical properties we consider, however, come from the original DNS data and the large-scale field is simply used as an indicator of where the large-scale updraft and downdraft regions are located.

3.1 Defining a Large-Scale Field

We obtain a large-scale field by employing a low-pass Helmholtz filter in all three spatial dimensions. The Helmholtz filter is defined implicitly as (Foias et al. 2001),

where \(\alpha = \Delta /(2\uppi )\), \(\Delta \) is the filter size, \(\phi (\pmb {x},t)\) is the unfiltered field and \(\overline{\phi }(\pmb {x},t)\) is the filtered (‘large-scale’) field. Equation 16 is solved by performing a Fourier decomposition in the periodic, horizontal directions to obtain a set of finite difference equations in the vertical direction. The boundary conditions are the same as those used in the simulation, in particular, the Helmholtz-filtered fields satisfy the no-slip condition. Being able to choose the boundary conditions that the large-scale field satisfies is a distinct advantage of the Helmholtz filter over more traditional spatial filters such as the box (or top-hat) filter, where each point is averaged over a volume specified by the filter size. Failing to satisfy the no-slip condition results in an unphysical increase in the large-scale TKE near the surface with the filter size (see Appendix 1). For this reason, other, more conventional filters were rejected.

Of the many detection techniques we could have used to identify the LSCs, we favoured spatial filtering for the following reason. Other detection techniques, such as time averaging, proper orthogonal decomposition and Lagrangian techniques, critically rely on the choice of a finite time interval over which the structures are defined. This time scale should be on the order of, or less than, the decorrelation time to avoid averaging out the large-scale structures themselves. However, preliminary work using two-dimensional simulations revealed that the decorrelation time in the CBL case can vary by up to one order of magnitude depending on the initial time from which it is calculated, and this variability does not reduce with increasing aspect ratio. This makes the choice of time scale highly dependent on the time period considered. Hence, spatial filtering, which instead utilizes a length scale, is a convenient choice.

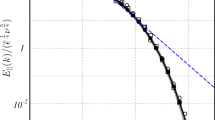

a Radial autocorrelation function of the vertical velocity at its height of maximum variance. The solid line shows the time average and shading shows one standard deviation away from the mean. b Integral length, \(L_{\mathrm {i}}\), defined by Eq. 17, as a function of time, where \(t_0\) is the time at the beginning of the averaging period. In this figure, we have extended the RBC simulation to demonstrate that it is in a statistically steady state, but as stated in Sect. 2.3.2, all following statistics from the RBC case shown herein are averaged over a time period \(t\approx 93t_{\mathrm {f}}\)

The filter size, \(\Delta \), determines the definition of “large scale” and here we consider two different characteristic length scales of the LSCs as candidates for \(\Delta \); a vertical scale and a horizontal scale. For the vertical scale, we use h, which characterizes the depth of the LSCs and for the horizontal scale, we use the following integral length (Salesky et al. 2017),

where \(\rho _w(s)\) is the radial autocorrelation function of the vertical velocity field at its height of maximum variance and \(l_0\) is the zero-crossing point of \(\rho _w(s)\) (Fig. 3a). The radial autocorrelation function at a given height is defined as

where \(r=\sqrt{x^2+y^2}\) and the subscript rms indicates the root-mean-square. Since \(L_{\mathrm {i}}\) is a measure of the horizontal distance over which vertical velocity fluctuations are correlated, it is a length scale characteristic of the large scales and naturally captures the greater horizontal extent of the LSCs found in Rayleigh–Bénard convection compared to the CBL (see Fig. 3b). Moreover, \(L_{\mathrm {i}}/h\) is steady in time (the standard deviation is less than 10% of the mean value in all cases), even in the CBL where h increases with time, so unlike the decorrelation time, \(L_{\mathrm {i}}\) does not depend on the time period considered. This result corroborates de Roode et al. (2004) for the CBL and von Hardenberg et al. (2008) for Rayleigh–Bénard convection. The former study showed that a length scale based on the vertical velocity spectrum in the mid-CBL remains steady in time, whilst the latter study showed that for large enough aspect ratios and beyond the initial transient, the length scale of the large-scale structures in Rayleigh–Bénard convection is also steady in time. Mean values of \(L_{\mathrm {i}}/h\) are shown in Table 2 and indicate that \(L_{\mathrm {i}}\) is 6–7% of the LSC width, \(\lambda _{\mathrm {LSC}}\), determined by the wavelength of the peak in the cospectrum between b and w.

In Table 3, we show how the choice of filter length scale affects the proportion of TKE remaining in the large-scale field. Using \(L_{\mathrm {i}}\) to define the large scales results in a slightly greater decrease of TKE in the RBC case than in the CBL case, and vice versa when using h. Either way, the partitioning of TKE between the systems is similar, despite the factor of two difference in horizontal scale between the CBL and RBC cases. For comparing the three configurations, it is thus irrelevant whether the LSCs are defined using their vertical scale or their horizontal scale. For a given configuration however, conditional statistics may well depend on the choice of filter length scale, and this is tested in Sect. 3.7. For the sake of clarity of figures, we only utilize the h-filtered fields for the conditional analysis presented in Sects. 3.3–3.6. The qualitative impact of spatial filtering with a filter size of h is shown in Fig. 4 for reference.

a–c Horizontal cross-sections of the h-filtered vertical velocity field at 0.1 h. The white horizontal line shows the length of h, which is the same in all three cases. The short black line shows the integral length, \(L_{\mathrm {i}}\) and the long black line shows the LSC width, \(\lambda _{\mathrm {LSC}}\). d–f Horizontal cross-sections of the unfiltered vertical velocity field at 0.1 h. g–i Zooms into the black boxes shown in panels d–f

3.2 Conditioning Criteria

We consider two different conditioning procedures. The first procedure conditions statistics from the original, unfiltered fields into large-scale updraft and downdraft regions based only on the sign of the large-scale vertical velocity field. For the second, we constrain our definition of updrafts to only large-scale buoyant updrafts, which have both positive vertical velocity and positive buoyancy fluctuation (see Fig. 5). This second, bivariate approach aims to test how sensitive surface-layer properties are to the conditioning criteria. We emphasize that the filtered fields are only used to determine the location of large-scale updraft and downdraft regions. The statistics themselves are taken from the unfiltered fields.

Schematic of the two conditioning procedures used in this study. Out of the four quadrants, the domain is partitioned into two regions, as indicated by the colour shading. Left: Partitioning into updrafts (quadrants I and II) and downdrafts (quadrants III and IV). Right: Partitioning into buoyant updrafts (quadrant I) and anything outside of that region (quadrants II, III and IV)

By partitioning fields into two regions, the horizontal plane average of a dependent variable, \(\phi \), may be expressed as

where \(a_{\mathrm {u}}\) is the area fraction covered by updrafts, \(a_{\mathrm {d}} = 1-a_{\mathrm {u}}\) is the remaining area fraction covered by downdrafts, \(\langle \phi \rangle _{\mathrm {u}}\) is the mean inside updrafts and \(\langle \phi \rangle _{\mathrm {d}}\) is the mean inside downdrafts. Note that when we consider buoyant updrafts, where both \(\overline{w}^\prime >0\) and \(\overline{b}^\prime >0\), “downdraft” regions contain negatively buoyant, ascending air (quadrant II in Fig. 5).

Using Eq. 19 and the identity \(\phi ^\prime = \phi - \langle \phi \rangle \), one can obtain the following expression for the variance,

where \(\langle \phi ^{\prime 2}\rangle _{\mathrm {u}} = \langle \phi ^2\rangle _{\mathrm {u}} - \langle \phi \rangle _{\mathrm {u}}^2\) and \(\langle \phi ^{\prime 2}\rangle _{\mathrm {d}} = \langle \phi ^2\rangle _{\mathrm {d}} - \langle \phi \rangle _{\mathrm {d}}^2\). The respective terms on the right-hand side of Eq. 20 are contributions from the variance within updrafts, the variance within downdrafts and the squared difference between the mean inside updrafts and the mean inside downdrafts, hereafter referred to as the “mean difference term”. We will consider the relative contribution of each of the three terms on the right-hand side of Eq. 20 to the buoyancy and vertical velocity variance. The contribution from downdrafts or the mean difference term should be large if downdrafts are to explain the significant deviations from MOST found in previous studies.

3.3 Area Fraction

Before we proceed directly onto the conditional analysis, it is first important to consider the updraft area fraction, as strong variations of \(a_{\mathrm {u}}\) with height could by itself partly explain deviations from MOST. Previous studies considering the updraft area fraction profile have shown that it approaches 0.5 near the surface, but did not have sufficient data to analyze the near-surface behaviour in detail (Young 1988; Schumann and Moeng 1991; Sorbjan 1996).

As shown in Fig. 6, the updraft area fraction behaves in a similar way in the surface layer across all three systems; \(a_{\mathrm {u}}\) only varies by 3% in the interval \(10z_\kappa \lesssim z \lesssim 100z_\kappa \), regardless of the conditioning criteria. When using the more restrictive buoyant updraft definition, \(a_{\mathrm {u}}\) is simply smaller by 10%. Therefore, the variation of \(a_{\mathrm {u}}\) with height has a negligible effect on the behaviour of updraft and downdraft properties in the ASL.

3.4 Buoyancy Statistics

The first property we consider is the mean buoyancy gradient. Several studies agree that the mean buoyancy is consistent with MOST for sufficiently unstable conditions (Kader and Yaglom 1990; Mellado et al. 2016; Maronga and Reuder 2017). In Fig. 7, we show the magnitude of the mean buoyancy gradient normalized by \((z/z_\kappa )^{-4/3}\), the free-convective scaling given by MOST, such that if this scaling law is satisfied in the surface layer, profiles will be constant in the vertical.

We find that the mean buoyancy gradient follows free-convective scaling not only within updrafts, but also within downdrafts in the LID and CBL cases. For updrafts, this is in the range \(40z_\kappa \lesssim z\lesssim 100z_\kappa \) and for downdrafts between \(20z_\kappa \lesssim z\lesssim 80z_\kappa \). We also find that the magnitude of the mean buoyancy gradient in downdrafts is 50% of that in updrafts, demonstrating that updrafts primarily determine the mean buoyancy gradient near the surface, but downdrafts make a non-negligible contribution. Moreover, these results do not depend on whether conditioning is based on the vertical velocity only, or on both the vertical velocity and the buoyancy.

In contrast to the LID and CBL cases, the mean buoyancy gradient does not follow free-convective scaling in either updrafts or downdrafts in the RBC case for the Reynolds numbers (equivalently Rayleigh numbers) that we reach in our simulations. The discrepancy of the mean buoyancy with the MOST prediction in the RBC case is in agreement with Pirozolli et al. (2017). We attribute this to a difference in the large-scale downdraft regions between the systems. In the RBC case, cold air descending from the upper plate results in the air becoming well-mixed lower down in the cell compared to the LID and CBL cases, where there is no forcing from above. Consequently, the mean buoyancy profile has less space to develop before its vertical gradient vanishes. This interpretation is supported in Fig. 7, where the minimum in the buoyancy gradient occurs lower down in the RBC case compared to the other two systems, both in updrafts and in downdrafts.

Magnitude of the mean buoyancy gradient normalized by free-convective scaling. Thick solid lines indicate conditioning based only on \(\overline{w}^\prime \) and thick dashed lines based on both \(\overline{w}^\prime \) and \(\overline{b}^\prime \). Grey ticks on the right-hand side indicate 0.1 h and 0.5 h

Our results for the mean buoyancy already give one indication of how changes in the upper boundary condition can be felt near the surface. Although replacing a linearly stratified atmosphere with an impenetrable, adiabatic lid appears to hardly affect \(\langle b \rangle \) in the surface layer, if downdrafts are comparatively cold, as in the RBC case, the behaviour of \(\langle b \rangle \) is greatly modified. However, at higher Reynolds number, where the surface layer is deeper compared to the receding diffusive layer, the mean buoyancy gradient may vanish higher up, and it is possible that the profiles in the RBC case may tend towards those found in the LID and CBL cases.

a–c Contributions to the total buoyancy variance from updraft, downdraft and mean difference terms. d–f Buoyancy variance normalized by free-convective scaling. Thick solid lines indicate conditioning based only on \(\overline{w}^\prime \) and thick dashed lines based on both \(\overline{w}^\prime \) and \(\overline{b}^\prime \). Grey ticks on the right-hand side indicate 0.1 h and 0.5 h

Considering now the buoyancy variance, we first analyze the mean difference term in Eq. 20. Given that both \(\langle b\rangle _{\mathrm {u}} \) and \(\langle b\rangle _{\mathrm {d}}\) are of the form \(c_1(z/z_\kappa )^{-1/3}+c_2\) in the LID and CBL cases, where \(c_1\) and \(c_2\) are empirical constants obtained from the mean buoyancy profiles, we are able to calculate the form of the mean difference term analytically. This is

where \(\alpha \), \(\beta \) and \(\gamma \) are constants. MOST predicts the buoyancy variance to follow a \((z/z_\kappa )^{-2/3}\) power law, so the mean difference term could explain part of the deviation from this prediction. However, as shown in Fig. 8a, b, the mean difference term contributes the least to the total variance in the surface layer of the LID and CBL cases. Moreover, Fig. 8d, e demonstrate that the mean difference term is in agreement with free-convective scaling (profiles are approximately constant with height) and is hence dominated by \(\alpha (z/z_\kappa )^{-2/3}\) rather than \(\beta (z/z_\kappa )^{-1/3}\). This confirms that deviations in the buoyancy variance are not caused by the mean difference term.

Downdrafts strongly deviate from free-convective scaling (Fig. 8d, e) and make a contribution of 20–30% to the total buoyancy variance in the surface layer (Fig. 8a, b). Whilst this is non-negligible, it is updrafts that most strongly determine the buoyancy variance near the surface and despite expectations that updraft properties would comply better with MOST, strong deviations from free-convective scaling occur within large-scale updraft regions. This result is independent of whether we define updrafts based only on the vertical velocity, or also on the buoyancy fluctuation.

Compared to the other two systems, the buoyancy variance behaves in a similar manner in the RBC case and again, much of the deviation from free-convective scaling occurs within updraft regions (Fig. 8c, f). The major difference is the behaviour of the downdraft profile and this will be discussed in Sect. 3.5.

In summary, the first- and second-order moments of the buoyancy are primarily determined by large-scale updraft regions, but somewhat counter-intuitively, MOST is not satisfied within those regions any better than in downdraft regions. Moreover, the buoyancy field behaves very similarly in the LID and CBL cases, even within downdraft regions. This is interesting because the buoyancy is a purely bottom-up scalar in the LID case, but in the CBL case, the buoyancy also has a top-down contribution due to the entrainment flux, and yet the signature of that remote air is not evident in near-surface downdraft statistics. This suggests that even within downdrafts, the buoyancy in the CBL is primarily determined by the bottom-up contribution. In order to test this hypothesis, in the following section we consider the opposite limit of a purely top-down scalar, as this represents the case in which downdrafts have the strongest impact near the surface.

3.5 Top-Down Scalar Statistics

The results of the preceding section indicate that the buoyancy scales similarly in both large-scale updraft and downdraft regions. This seems to contradict the original hypothesis that downdrafts would show a much stronger signature of the top-down contribution than updrafts, and leads us to ask to what extent \(\langle b^{\prime 2}\rangle _{\mathrm {d}}\) near the surface is determined by air descending from aloft (the top-down contribution), and to what extent by thermals rising from the surface within the large-scale downdraft regions (the bottom-up contribution). A strong bottom-up contribution could partly explain the similarity to the updraft profile. To this end, we compare our buoyancy results to those for the top-down scalar (Fig. 9), which characterizes the contribution of air from aloft since it has zero surface flux.

Top-down scalar variance normalized by the convective scale, \(\chi _*=F_{\chi ,0}/w_*\). Linestyles are as in Fig. 8. Grey ticks on the right-hand side indicate 0.1h and 0.5h

In all cases, the top-down scalar variance is larger in downdrafts than in updrafts, is approximately constant with height near the surface, and above 0.1h (the lower grey tick in Fig. 9), \(\langle \chi ^{\prime 2}\rangle _{\mathrm {d}}\) begins to increase with height, indicating that top-down scalar variance from above is carried all the way to the surface layer by downdrafts. By contrast, \(\langle b^{\prime 2}\rangle _{\mathrm {d}}\) consistently decreases with height faster than \(z^{-2/3}\) in the LID and CBL cases (profiles in Fig. 8d, e lean to the left of the vertical line), indicating a negligible top-down contribution to the buoyancy field near the surface. In the RBC case, the situation is somewhat different (Fig. 8f). Above 0.1 h, the decrease in \(\langle b^{\prime 2}\rangle _{\mathrm {d}}\) becomes markedly slower than \(z^{-2/3}\) (profiles lean to the right of the vertical line). This suggests that the buoyancy variance within downdrafts already begins to be affected by cold air descending from aloft into the surface layer of the RBC case, whereas for the LID and CBL cases, \(\langle b^{\prime 2}\rangle _{\mathrm {d}}\) is mainly determined by the bottom-up contribution.

In Fig. 9b, c, the larger normalized top-down scalar variance in the LID case compared to the RBC case is at first sight surprising and calls for some explanation. The reason is related to the scale at which scalar fluctuations are generated at the top of the domain. Buoyancy fluctuations at the top of the domain in the RBC case are generated at small scales and the dissipation is fast, but in the LID case, which has no buoyancy forcing at the upper plate, buoyancy fluctuations are generated at larger scales by the LSCs and the dissipation is comparatively slow (see Fig. 2). Since the buoyancy is an active scalar, it modulates fluctuations in the velocity field, which the passive scalar follows. Hence, \(\langle \chi ^{\prime 2}\rangle \) is generated at small scales and is dissipated quickly near the upper plate of the RBC case, but in the LID case, it takes longer to dissipate as it first needs to be transferred to smaller scales via the turbulent cascade, so there is more time for \(\langle \chi ^{\prime 2}\rangle \) to be carried down to the surface and accumulate (Mellado et al. 2017).

In summary, the buoyancy variance near the surface scales similarly between updrafts and downdrafts in the LID and CBL cases due to the dominating influence of the bottom-up contribution, associated with thermals penetrating into the downdraft region. In the RBC case, by contrast, the effect of the top-down contribution, associated with cold air descending from aloft, is evident in near-surface downdraft buoyancy statistics.

3.6 Vertical Velocity Statistics

We now consider the vertical velocity field. Since the mean velocity is zero in free convection, we only consider the variance. The vertical velocity variance confirms the major results from the analysis of the buoyancy. Both updrafts and downdrafts are of comparable importance to determining \(\langle w^{\prime 2}\rangle \) near the surface (Fig. 10a–c) and although deviations from free-convective scaling do occur in downdraft regions, they also occur in updraft regions (Fig. 10d–f). Once again, the LID and CBL cases demonstrate remarkably similar behaviour, whilst in the RBC case, \(\langle w^{\prime 2}\rangle _{\mathrm {d}}\) is larger than in the other two cases due to the more vigorous downdraft plumes generating larger vertical velocity fluctuations.

a–c Contributions to the vertical velocity variance from updraft, downdraft and mean difference terms. d–f Velocity variance normalized by free-convective scaling. Linestyles are as in Fig. 8. Grey ticks on the right-hand side indicate 0.1h and 0.5h

3.7 Dependence on Filter Size

When large scales are defined based on a filter length scale equal to h, our results suggest that both large-scale updrafts and downdrafts contribute non-negligibly towards deviations from MOST in the buoyancy and vertical velocity variance. In this section we test the dependence of these results on the definition of updraft and downdraft regions. We utilize the same approach as before, but now define updraft and downdraft regions from three different vertical velocity fields with an increasing filter size: the unfiltered field (filter size equal to zero), the \(L_{\mathrm {i}}\)-filtered field and the h-filtered field. For conciseness, we only show the CBL case and conditioning based on the vertical velocity, but the results are similar for the non-penetrative cases and the factor of two difference in \(L_{\mathrm {i}}\) between the RBC and CBL cases is unimportant.

Sensitivity of conditional statistics in the CBL case to filter size, \(\Delta \). a Updraft area fraction, b mean buoyancy gradient, c buoyancy variance and d vertical velocity variance. Colours are as in Figs. 7, 8, 9 and 10. Colour shading indicates (light) \(\Delta =0\), (medium) \(\Delta =L_{\mathrm {i}} = 0.16h\) and (dark) \(\Delta =h\)

Figure 11 demonstrates that the larger the filter size is, the larger the downdraft contribution is and the more similarly updrafts and downdrafts behave. For second-order moments (Fig. 11c, d), the increasing downdraft contribution comes at the expense of the mean-difference term, indicating that mean properties within large-scale updraft and downdraft regions become more similar to each other when larger filter sizes are considered (e.g., Fig. 11b). These order-of-one changes are not caused by differences in the area fraction profile, which only changes by 2% in the surface layer between \(\Delta =L_{\mathrm {i}}\) and \(\Delta =h\) (Fig. 11a), but rather by fluctuations that occur within downdraft regions defined by a larger filter size. For filter sizes of order h, these fluctuations are filtered out of the large-scale fields (see Fig. 4). When statistics from the original field are taken within those large-scale downdraft regions, they include the fluctuations. Their presence strongly increases the variance within downdraft regions and also causes downdraft properties to become more similar to those of updrafts. This behaviour is consistent with the observation in Sect. 3.5 that the variance within downdrafts near the surface is mainly determined by the bottom-up contribution associated with thermals penetrating into the downdraft. For smaller filter sizes of order \(L_{\mathrm {i}}\), the fluctuations are not filtered out (not shown) and instead belong to the updraft regions. Their presence does not greatly alter the behaviour in those regions, hence why updraft properties demonstrate a weaker dependence on filter size.

Despite changes to the downdraft profiles, many of our conclusions in previous sections are robust. Regardless of the filter size used to define LSCs, downdrafts are partially responsible for the failure of the vertical velocity variance to comply with MOST, either directly through the downdraft contribution, or through the mean difference term. Most importantly, for both the buoyancy and the vertical velocity variance, strong deviations occur within large-scale updraft regions, and these are at least as important as downdrafts, if not more so, for determining the behaviour near the surface.

4 Summary and Conclusions

We have used direct numerical simulation and conditional analysis to explore how large-scale circulations may lead to deviations from MOST in free-convective flows ranging from the convective boundary layer to Rayleigh–Bénard convection. In all three configurations, the Prandtl number is unity and the Reynolds number based on the free-fall velocity is of order \(10^4\) (equivalently, Rayleigh number of order \(10^8\)). We have focused on the first- and second-order moments of the buoyancy and vertical velocity.

Previous studies have indicated that compliance with MOST is not guaranteed when large-scale downdrafts transport non-local, outer-layer air to the surface layer. Using a spatial filter to define the large scales, we have found that, whilst downdrafts contribute towards deviations from MOST, they are not the most important factor. Comparison with a top-down scalar (a scalar with zero surface flux) reveals that within downdraft regions, the buoyancy variance near the surface is predominantly determined by a bottom-up contribution, suggesting that the transport of non-local air into the surface layer is of little importance in causing deviations from MOST in this quantity.

Strong deviations from MOST also occur within large-scale updraft regions. These deviations are not due to changes in the updraft area fraction with height, which varies by no more than 5% in the surface layer, and occur regardless of the filter size used to define “large scale” and regardless of whether updrafts are defined as ascending air, or as air that is both ascending and positively buoyant. This indicates that near-surface updraft properties are not only determined locally by the surface buoyancy flux and the distance from the ground, but also by outer scales. The reasons for this are unclear. Shear effects caused by the large-scale horizontal flow may play a role here, as suggested before in studies of Rayleigh–Bénard convection, but this requires further investigation, particularly in the convective boundary layer where the large-scale horizontal motion is weaker.

A comparison of the CBL, LID and RBC configurations has shown that replacing a linearly stratified atmosphere with an impenetrable, adiabatic lid has very little impact on surface-layer properties, but if the upper plate is cooled, there are some notable changes of behaviour. In particular, the RBC case differs from the LID and CBL cases in the following ways: firstly, the mean buoyancy does not follow free-convective scaling. Secondly, the buoyancy variance within downdraft regions is not only affected by thermals rising from the surface, but also by cold air descending from aloft. Lastly, the contribution from downdraft regions to the vertical velocity variance is more important. It therefore seems that changes to the upper boundary conditions only result in significant changes in the surface layer if downdrafts are sufficiently cold and strong to modify properties there. Hence, we conclude that at the moderate Reynolds numbers considered here, the LID case is a better model of the unstable atmospheric surface layer than is classical Rayleigh–Bénard convection. The LID case has the advantage that it provides a longer statistically steady state than the CBL case, allowing for greater statistical convergence.

These findings also have implications for field measurements. For example, high- or low-pass filters are sometimes applied to atmospheric measurement data to remove mesoscale variations or inertial subrange turbulence. Whilst our results suggest that such a procedure would have little effect on measurements taken within updrafts, measurements taken within downdraft regions may be more strongly affected by the filter size.

References

Adrian R (1996) Variation of temperature and velocity fluctuations in turbulent thermal convection over horizontal surfaces. Int J Heat Mass Transfer 39:2303–2310

Adrian R, Ferreira R, Boberg T (1986) Turbulent thermal convection in wide horizontal fluid layers. Exp Fluids 4:121–141

Ansorge C, Mellado JP (2014) Global intermittency and collapsing turbulence in the stratified planetary boundary layer. Boundary-Layer Meteorol 153:89–116

Businger JA (1973) A note on free convection. Boundary-Layer Meteorol 4:323–326

Businger JA, Wyngaard JC, Izumi Y, Bradley PF (1971) Flux-profile relationships in the atmospheric surface layer. J Atmos Sci 28:181–189

Carpenter M, Kennedy C (1994) Fourth-order 2N-storage Runge–Kutta schemes. In: Technical Reports on NASA Technical Memorandum 109112. NASA Langley Research Center

Chillà F, Schumacher J (2012) New perspectives in turbulent Rayleigh–Bénard convection. Eur Phys J E 35:58

Chung D, Matheou G (2012) Direct numerical simulation of stationary homogeneous stratified sheared turbulence. J Fluid Mech 696:434–467

de Bruin H, Kohsiek W, van den Hurk B (1993) A verification of some methods to determine the fluxes of momentum, sensible heat, and water vapour using standard deviation and structure parameter of scalar meteorological quantities. Boundary-Layer Meteorol 63:231–257

de Roode S, Duynkerke P, Jonker H (2004) Large-eddy simulation: How large is large enough? J Atmos Sci 61:403–421

Deardorff J (1970) Preliminary results from numerical integrations of the unstable planetary boundary layer. J Atmos Sci 27:1209–1211

Deardorff J (1970) Convective velocity and temperature scales for the unstable planetary boundary layer and for Rayleigh convection. J Atmos Sci 27:1211–1213

du Puits R, Willert C (2016) The evolution of the boundary layer in turbulent Rayleigh–Bénard convection in air. Phys Fluids 28(044):108

Foias C, Holm D, Titi E (2001) The Navier–Stokes-alpha model of fluid turbulence. Physica D 152–153:505–519

Garcia J, Mellado JP (2014) The two-layer structure of the entrainment zone in the convective boundary layer. J Atmos Sci 71:1935–1955

Kader B, Yaglom A (1990) Mean fields and fluctuation moments in unstably stratified turbulent boundary layers. J Fluid Mech 212:637–662

Kaimal JC, Wyngaard JC, Haugen DA, Coté OR, Izumi Y (1976) Turbulence structure in the convective boundary layer. J Atmos Sci 33:2152–2169

Khanna S, Brasseur JG (1997) Analysis of Monin–Obukhov similarity from large-eddy simulation. J Fluid Mech 345:251–286

Kraichnan RH (1962) Turbulent thermal convection at arbitrary prandtl number. Phys Fluids 5:1374–1389

Lele S (1992) Compact finite difference schemes with spectral-like resolution. J Comput Phys 103:16–42

Li Q, Gentine P, Mellado JP, McColl K (2018) Implications of nonlocal transport and conditionally averaged statistics on Monin–Obukhov similarity theory and townsend’s attached eddy hypothesis. J Atmos Sci 75:3403–3431

Lohou F, Saïd F, Lothon M, Durand P, Serça D (2010) Impact of boundary-layer processes on near-surface turbulence within the West African monsoon. Boundary-Layer Meteorol 136:1–23

Maronga B, Reuder J (2017) On the formulation and universality of Monin–Obukhov similarity functions for mean gradients and standard deviations in the unstable surface layer: results from surface-layer-resolving large-eddy simulations. J Atmos Sci 74:989–1010

McColl K, van Heerwaarden C, Katul G, Gentine P, Entekhabi D (2017) Role of large eddies in the breakdown of the Reynolds analogy in an idealized mildly unstable atmospheric surface layer. Q J R Meteorol Soc 143:2182–2197

Mellado JP (2012) Direct numerical simulation of free convection over a heated plate. J Fluid Mech 712:418–450

Mellado JP, Ansorge C (2012) Factorization of the Fourier transform of the pressure-Poisson equation using finite differences in colocated grids. Z Angew Math Mech 92:380–392

Mellado JP, van Heerwaarden C, Garcia J (2016) Near-surface effects of free atmosphere stratification in free convection. Boundary-Layer Meteorol 159:69–95

Mellado JP, Puche M, van Heerwaarden C (2017) Moisture statistics in free convective boundary layers growing into linearly stratified atmospheres. Q J R Meteorol Soc 143:2403–2419

Mellado JP, Bretherton C, Stevens B, Wyant M (2018) DNS and LES for simulating stratocumulus: better together. J Adv Model Earth Syst 10:1421–1438

Moeng CH, Rottuno R (1990) Vertical velocity skewness in the buoyancy-driven boundary layer. J Atmos Sci 47:1149–1162

Monin A, Obukhov A (1954) Basic laws of turblent mixing in the surface layer of the atmosphere. Tr Akad Nauk SSSR Geophiz Inst 24:163–187

Pandey A, Scheel J, Schumacher J (2018) Turbulent superstructures in Rayleigh–Bénard convection. Nat Commun 9:2118

Park SB, Gentine P, Schneider K, Farge M (2016) Coherent structures in the boundary and cloud layers: role of updrafts, subsiding shells and environmental subsidence. J Atmos Sci 73:1789–1814

Pirozolli S, Bernardini M, Verzicco R, Orlandi P (2017) Mixed convection in turbulent channels with unstable stratification. J Fluid Mech 821:482–516

Pope SB (2000) Turbulent flows. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Prandtl L (1932) Meteorologische Anwendung der Strömungslehre. Beitr Phys Atmos 19:188–202

Priestley C (1954) Convection from a large horizontal surface. Aust J Phys 7:176–201

Salesky S, Anderson W (2018) Buoyancy effects on large-scale motions in convective atmospheric boundary layers: implications for modulation of near-wall processes. J Fluid Mech 856:135–168

Salesky S, Chamecki M, Bou-Zeid E (2017) On the nature of the transition between roll and cellular organization in the convective boundary layer. Boundary-Layer Meteorol 163:41–68

Schmidt H, Schumann U (1989) Coherent structure of the convective boundary layer derived from large-eddy simulations. J Fluid Mech 200:511–562

Schumann U, Moeng CH (1991) Plume fluxes in clear and cloudy convective boundary layers. J Atmos Sci 48:1746–1757

Shah S, Bou-Zeid E (2014) Direct numerical simulations of turbulent Ekman layers with increasing static stability: modifications to the bulk structure and second-order statistics. J Fluid Mech 760:494–539

Shishkina O, Stevens R, Grossmann S, Lohse D (2010) Boundary layer structure in turbulent thermal convection and its consequences for the required numerical resolution. New J Phys 12(075):022

Shishkina O, Horn S, Wagner S, Ching E (2015) Thermal boundary layer equation for turbulent Rayleigh–Bénard convection. Phys Rev Lett 114(114):302

Siebesma A, Cuijpers J (1995) Evaluation of parametric assmuptions for shallow cumulus convection. J Atmos Sci 52:650–666

Siebesma AP, Soares PMM, Teixeira J (2007) A combined eddy-diffusivity mass-flux approach for the convective boundary layer. J Atmos Sci 64:1230–1248

Sorbjan Z (1996) Numerical study of penetrative and “solid lid” nonpenetrative convective boundary layers. J Atmos Sci 53:101–112

Townsend A (1959) Temperature fluctuations over a heated horizontal surface. J Fluid Mech 5:209–241

van de Boer A, Moene AF, Graf A, Schüttemeyer D, Simmer C (2014) Detection of entrainment influences on surface-layer measurements and extension of Monin–Obukhov similarity theory. Boundary-Layer Meteorol 152:19–44

van Reeuwijk M, Jonker HJJ, Hanjalić K (2008) Wind and boundary layers in Rayleigh–Bénard convection. II. Boundary layer character and scaling. Phys Rev E 77:036,312

von Hardenberg J, Parodi A, Passoni G, Provenzale A, Spiegel E (2008) Large-scale patterns in Rayleigh–Bénard convection. Phys Lett A 372:2223–2229

Wyngaard JC, Coté OR, Izumi Y (1971) Local free convection, similarity, and the budgets of shear stress and heat flux. J Atmos Sci 28:1171–1182

Young G (1988) Turbulence structure of the convective boundary layer. Part II: Phoenix 78 aircraft observations of thermals and their environment. J Atmos Sci 45:727–735

Acknowledgements

Open access funding provided by Max Planck Society. The authors gratefully acknowledge the Gauss Centre for Supercomputing (GCS) for providing computing time through the John von Neumann Institute for Computing (NIC) on the GCS share of the supercomputer JUQUEEN at Jülich Supercomputing Centre (JSC). This work is supported by the Priority Programme SPP 1881 Turbulent Superstructures of the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG). Primary data and scripts used in the analysis and other supporting information that may be useful in reproducing the authors’ work are archived by the Max Planck Institute for Meteorology and can be obtained by contacting publications@mpimet.mpg.de.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix 1

Appendix 1

Top-hat filters are commonly used in the literature to define large-scale fields and we originally considered a three-dimensional top-hat filter for our study (Pope 2000). However, the implementation of the top-hat filter near the top and bottom boundaries is challenging for several reasons. First, the top-hat filter is typically implemented defining the filter size equal to an integer multiple of the grid spacing, and because the grid spacing is varying with height near the surface to satisfy the resolution constraints as explained in Sect. 2.4, the filter size is also varying with height. This artificially introduces an inhomogeneity in the large-scale field that could affect some of the properties that we are interested in, such as the variation with height of the area fractions associated with large-scale updrafts and downdrafts. This problem is solved when using the Helmholtz filter defined via Eq. 16.

One could avoid this problem by interpolating the DNS data into a uniform grid with a grid spacing equal to the smallest grid spacing in the vertical direction. However, even in this case of a uniform grid, finding appropriate boundary conditions for the filter operation when using a three-dimensional top-hat filter remains a challenge. We considered ghost cells where the fields were defined based on a linear extrapolation from the interior of the domain towards the exterior of the domain, applying then the top-hat filter across the boundary. However, such an approach fails to satisfy the no-slip boundary condition. In Fig. 12, we demonstrate this by comparing a top-hat filter with the Helmholtz filter in the RBC case. In the case of the top-hat filter, we obtain a non-zero filtered velocity field at the lower and upper boundaries, causing the proportion of TKE remaining in the filtered field to actually increase as the filter size becomes larger. The Helmholtz filter alleviates this issue and results in a systematic decrease in remaining TKE with increasing filter size.

Comparison of the effect of the top-hat filter and the Helmholtz filter on the TKE in the RBC case. a, b Percentage of vertically-integrated TKE remaining in the filtered flow, \(\int _0^{h}\langle \overline{u_i}^{\prime 2}\rangle \mathrm {d}z/\int _0^{h}\langle u_i^{\prime 2}\rangle \mathrm {d}z\), against filter size, \(\Delta \). c, d TKE profile as a function of filter size

To better understand the implicit definition of the Helmholtz filter via Eq. 16, one can consider this filter applied only in the horizontal directions, where the periodic boundary conditions allow for Fourier analysis. In this case, one finds that

where \(\hat{\cdot }\) indicates the Fourier transform along the horizontal planes, and k is the corresponding wavenumber. This expression shows that the filtered field is approximately equal to the original field when \(k\ll 2\uppi /\Delta \), and that the filtered field is approximately zero when \(k\gg 2\uppi /\Delta \). Hence, Eq. 16 defines a low-pass filter operation with a filter size \(\Delta \).

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Fodor, K., Mellado, J.P. & Wilczek, M. On the Role of Large-Scale Updrafts and Downdrafts in Deviations From Monin–Obukhov Similarity Theory in Free Convection. Boundary-Layer Meteorol 172, 371–396 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10546-019-00454-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10546-019-00454-3