Abstract

The effect of nickel deprivation from the influent of a mesophilic (30°C) methanol fed upflow anaerobic sludge bed (UASB) reactor was investigated by coupling the reactor performance to the evolution of the Methanosarcina population of the bioreactor sludge. The reactor was operated at pH 7.0 and an organic loading rate (OLR) of 5–15 g COD l−1 day−1 for 191 days. A clear limitation of the specific methanogenic activity (SMA) on methanol due to the absence of nickel was observed after 129 days of bioreactor operation: the SMA of the sludge in medium with the complete trace metal solution except nickel amounted to 1.164 (±0.167) g CH4-COD g VSS−1 day−1 compared to 2.027 (±0.111) g CH4-COD g VSS−1 day−1 in a medium with the complete (including nickel) trace metal solution. The methanol removal efficiency during these 129 days was 99%, no volatile fatty acid (VFA) accumulation was observed and the size of the Methanosarcina population increased compared to the seed sludge. Continuation of the UASB reactor operation with the nickel limited sludge lead to incomplete methanol removal, and thus methanol accumulation in the reactor effluent from day 142 onwards. This methanol accumulation subsequently induced an increase of the acetogenic activity in the UASB reactor on day 160. On day 165, 77% of the methanol fed to the system was converted to acetate and the Methanosarcina population size had substantially decreased. Inclusion of 0.5 μM Ni (dosed as NiCl2) to the influent from day 165 onwards lead to the recovery of the methanol removal efficiency to 99% without VFA accumulation within 2 days of bioreactor operation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Biological wastewater treatment processes require both macronutrients (Goodwin et al. 1990) and micronutrients for bacterial metabolism, growth and activity (Florencio et al. 1994; Cook and Shiemke 1996; Mulrooney and Hausinger 2003). The optimal operation of upflow anaerobic sludge bed (UASB) reactors and similar anaerobic wastewater treatment systems highly depends on the presence of metal ions in the influent wastewater (Speece et al. 1983; Oleszkiewicz and Sharma 1990; Singh et al. 1999). Methanolic wastewater is commonly treated at full-scale in UASB reactors (Weijma 2001). Methanol is an important constituent of wastewater generated in the petrochemical industry and in the widely used “kraft” process for wood pulping in the paper industry.

Methanogenic Archaea use several pathways to reduce the various carbon substrates involved in methanol degradation (methanol, acetate, and CO2/H2) (Fig. 1A), but each pathway converges to the common intermediate methyl-S-CoM (Thauer 1998). Methyl-S-CoM and coenzyme B are the substrates of methyl-S-CoM reductase, whereas methane and heterodisulfide are its products (Bobik et al. 1987; Ellermann et al. 1988) (Fig. 1B).

Depletion of cobalt (Zandvoort et al. 2006a) has been shown to induce methanol accumulation, and, later, acidification, of methanol-fed UASB reactors (Fermoso et al. 2008). This is due to the key role of cobalt in the direct conversion of methanol to methane, as it forms the metallocenter of corrinoid compounds that catalyze the methyl transfer from methanol to methyl-S-CoM (Thauer 1998; Fermoso et al. 2008). Similarly, nickel plays also a key role in the methanogenic conversion of methanol: one mol of methyl-S-CoM reductase contains 2 mol of tightly, but not covalently, bound coenzyme F 430 (Ellefson et al. 1982). F 430 is a nickel porphinoid (Fig. 2). In addition, many hydrogenase enzymes involved in hydrogen formation possess nickel (Deppenmeier et al. 1992; Kemner and Zeikus 1994). For example, carbon monoxide dehydrogenase (CODH), which possesses two nickel-containing metallocentres, is present in both acetoclastic methanogens and acetogenic microorganisms (Hausinger 1987). In medium rate methanol-fed UASB reactors (organic loading rate (OLR) of 7.5 g COD l−1 day−1), omission of nickel from the influent indeed induced a nutrient (nickel) limitation of the methanol conversion by the granular sludge (Zandvoort et al. 2002b).

Structure of coenzyme F430 in the Ni2+ oxidation state. From Thauer (1998)

The granular sludge present in UASB reactors consists of dense conglomerates of biomass. The bioavailability of a metal in a sludge granule depends on the chemical speciation of the metal and physical processes within the granular matrix, e.g., adsorption and precipitation. In studies on metal bioavailability in complex biological systems as a UASB granule, it is usually assumed that the metal bioavailability is correlated to the free metal ion concentration in the liquid phase (Weng et al. 2005).

This study aims to evaluate the effect of nickel deprivation on the performance of a high-rate methanol-fed UASB reactor (OLR: 15 g COD l−1 day−1). Specifically, it was investigated whether the mechanism of nickel deprivation during high rate methanol conversion is similar to the outline for cobalt deprivation (Fermoso et al. 2008) resulting in acidification of the UASB reactor (Fig. 3) or if it follows the outline proposed by Zandvoort et al. (2002b), where long-term operation of medium rate UASB reactors without nickel in the influent appeared to induce a nickel independent methanol degradation route. The fate and removal efficiency of methanol, along with the metal content of the UASB sludge were monitored as a function of time. The metabolic properties, specific methanogenic activity (SMA), the abundance of the key organism Methanosarcina and possible nickel limitation of the sludge that developed in the UASB reactor were characterized. The effect of nickel speciation on the uptake and activity of nickel-limited anaerobic granular sludge was studied as well.

Materials and methods

Source of biomass

Methanogenic granular sludge was obtained from a full-scale UASB reactor treating paper mill wastewater (pH 7.0, 30°C) at industriewater Eerbeek (Eerbeek, The Netherlands), described in detail by Zandvoort et al. (2006b).

Medium composition

The reactor was fed with a basal medium as synthetic watewater, consisting of methanol, macronutrients, and a trace metal solution (Table 1). The inorganic macronutrients contained (mg l−1 basal medium): NH4Cl (280), K2HPO4 (250), MgSO4·7H2O (100), and CaCl2·2H2O (10). To ensure pH stability, 2.52 g (30 mM) of NaHCO3 was added per liter of basal medium. To avoid precipitation in the storage vessels prior to reactor feeding, the UASB influent was composed of three streams: (1) macronutrients and trace metal solution without K2HPO4 and NaHCO3, (2) methanol with NaHCO3 and K2HPO4 and (3) dilution water. Tap water was used to prepare the influent and as dilution water.

UASB reactor operation

The experiment was performed in a Plexiglas cylindrical UASB reactor with a working volume of 7.25 L and an inner diameter of 0.1 m. The reactor was operated at 30 (±2)°C in a temperature-controlled room. The UASB reactors were inoculated with 8.02 g VSS l−1 reactor and operated at a hydraulic retention time (HRT) of 8 h. The conical bottom of the reactors was filled with glass marbles (1 cm diameter) to evenly distribute the influent over the sludge bed. Peristaltic pumps (type 505S, Watson and Marlow, Falmouth, UK) were employed for influent flow, whereas no effluent recycle was applied. The superficial liquid upflow velocity was 0.1 m h−1.

The produced biogas was led through a water lock filled with a concentrated NaOH (15%) solution in order to remove CO2 and H2S. The volume of the produced methane was measured with a wet gas meter (Schlumberger Industries Dordrecht, The Netherlands).

The reactor run was divided into three periods. Period I [(PI), days 0–137] focused on methanogenesis from methanol under nickel limiting conditions. On day 137, 65% of the sludge bed (calculated based on bed height) was removed from the reactor to perform kinetic studies with the nickel-limited methanogenic sludge. Period II [(PII), days 137–165)] focused on methylotrophic acetogenesis under nickel-limited conditions. Period III (PIII), days 165–191] focused on the potential recovery of methylotrophic methanogenesis by the continuous addition of nickel (0.5 μM Ni2+ as NiCl2) to the bioreactor influent.

Specific methanogenic activity assays

The SMA of the sludge that developed in the reactor was determined in duplicate at 30 (±2)°C using on-line gas production measurements as described by Zandvoort et al. (2002a). Briefly, ∼1 g (wet weight) of granular sludge was transferred to serum bottles (0.12 L) containing 0.05 L of basal medium with the same composition as the reactor basal medium, but which was supplemented with methanol (4 g COD l−1) or acetate (2 g COD l−1) as the substrate. The data were plotted in a rate versus time curve, using moving average trend lines with an interval of ten data points.

The SMA with methanol as the substrate was determined on days 22, 35, 45, 64, 82, 95, 110, 129, and 137, and with acetate on days 129 and 168. The effect of different metal concentrations in the test medium was also studied for the different sludge samples. Sludge samples for SMA were always taken from the same place (the mid-height) in the sludge bed.

Metal uptake kinetics

The apparent affinity constant (\(K_{\rm m}^{\prime}\)) and maximum specific methanogenic activity (SMAmax) with methanol for NiCl2 and NiEDTA2− were determined with nickel-deprived granular sludge harvested from the UASB reactor on day 137. The evolution of the methanol and dissolved nickel concentration as well as pressure increase during methanogenic methanol degradation upon addition of NiCl2 or NiEDTA2− (0.5 μM) were monitored. The \(K_{\rm m}^{\prime}\) and SMAmax were calculated using Michaelis-Menten kinetics, following SMA assays with different initial nickel concentrations. The free nickel concentration in the liquid media was calculated by equilibrium speciation modeling (MINTEQA2).

Fluorescent in situ hybridization

The microbial population present in the anaerobic granules was studied by fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) as described by Fermoso et al. (2008). Granules were fixed in 4% (w/v) paraformaldehyde in phosphate buffered saline (PBS; 130 mmol l−1 sodium chloride and 10 mmol l−1 sodium phosphate [pH 7.2]) at 4°C for 6 h, and cross-sections (thickness, 16 μm; ∅, 0.5–1.5 mm) were prepared as described previously (Sekiguchi et al. 1999). FISH was performed as described by Schramm et al. (1998) using a Cy3-labeled 16S rRNA-targeted oligonucleotide probe (Biomers.net, Germany), Sarci551 (Sorensen et al. 1997), specific for Methanosarcina. The stringency in the hybridization buffer used was achieved by adding formamide to a final concentration (v/v) of 20%. The Non338 probe (Wallner et al. 1993) was used as a negative control, whereas pure cultures of Methanosarcina barkeri were used to positively control the Sarci551 probe. Specimens were viewed using a Nikon E600 epifluorescent microscope equipped with a 100 W mercury bulb and a Cy3 filter set. The abundance of Methanosarcina was determined as the fraction of the total area of respective granule sections.

Metal composition of the sludge

The total metal content of the sludge was determined after destruction with Agua regia (mixture of 2.5 ml 65% HNO3 and 7.5 ml 37% HCl) added to ∼1 g (wet weight) of granular sludge samples. After microwave destruction (Milestone ETHOS E temperate controlled; Milestone INC., Monroe, CT, USA), the samples were paper-filtered (Schleider Schuell 589, Germany) and diluted to 0.1 L with demineralised water. The total metal concentration was determined by Inductively Coupled Plasma Optical Emission Spectroscopy (ICP-OES; Varian, Australia) as described by van Hullebusch et al. (2005).

Ultra-pure water (Milli-Ro System, Millipore, Bedford, MA, USA) was used to prepare standard solutions of all reagents, which were of suprapur quality (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) and were checked for possible trace metal contamination. All glassware and plastic material used was treated for 12 h with 10% (v/v) HNO3 and rinsed vigorously with demineralized water.

Chemical analyses

Methanol and volatile fatty acid (VFA) were determined using gas liquid chromatography as described by Fermoso et al. (2008). The total suspended solids (TSS) and volatile suspended solids (VSS) concentrations were determined according to Standard Methods (APHA/AWWA 1998). All chemicals were of analytical or biological grade and purchased from E. Merck AG (Darmstadt, Germany).

Results

Reactor operation

After a start-up period of 12 days, methanol was fully converted to methane in the UASB reactor (Fig. 4). The OLR was increased twice during PI, first from 5 to 10 g COD l−1 day−1 on day 64 and then from 10 to 15 g COD l−1 day−1 on day 113, without resulting in methanol or VFA accumulation in the effluent (Fig. 4). The methanol effluent concentration started to accumulate on day 130, reaching a maximum value of 1,380 mg COD-MeOH l−1 on day 133, corresponding to 31% of the influent methanol concentration (4,500 mg COD-MeOH l−1). On day 137, the applied OLR was reduced from 15 to 5 g COD l−1 day−1 in order to avoid overloading of the reactor due to the sludge removal to perform kinetic studies on the reactor sludge. Methanol was completely removed without any VFA accumulation from day 137 (PII) until day 142. From day 142 onwards, however, methanol accumulation was observed in the UASB reactor, reaching 819 mg COD-MeOH l−1 by day 147. From day 149, the concentration of accumulated methanol decreased. This was accompanied by an increase in the VFA concentration, mainly acetate (around 86%). On day 163, VFA effluent concentrations reached a maximum of 1,150 mg COD-VFA l−1, corresponding to 95% of the influent methanol being converted to VFA.

Evolution of the reactor performance with time. (A) Calculated influent methanol (- - -), measured influent methanol (□), effluent methanol (■), and effluent VFA (▴) concentrations. (B) Total VFA (▴), acetate (x), propionate (•), butyrate (♦), and valerate (*) concentration. (C) CH4 production (Δ), note that gas production was not measured from day 137 onwards due to technical problems. (D) pH (◊) of UASB reactor mixed liquor

Methanol was fully removed from the wastewater by the UASB reactor from day 155 (prior to the nickel additions) onwards, but mainly converted to VFA (Fig. 4A). The continuous addition of 0.5 μM Ni2+ as NiCl2 to the influent from day 165 onwards (PIII) resulted in an immediate reduction in the effluent VFA concentration. From day 172 (7 days after the initiation of nickel supplementation) until the end of the experiment (day 191), the methanol was fully removed without any VFA accumulation. In fact, no VFA were detected in the effluent anymore after day 172.

Evolution of SMA over time

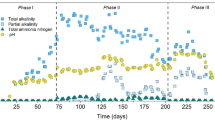

A slight nickel limitation of methylotrophic methanogenesis was observed in the beginning of the reactor operation. The SMA on methanol in a medium with the complete metal solution was 6.5% (day 22) and 17% (day 35) higher than in a medium with the complete metal solution except nickel (Fig. 5). On day 45, the SMA on methanol was double compared to day 35 for all the trace metal solutions tested (Table 2), which likely can be attributed to adaptation of the sludge to methanol. Similar SMA values to those on day 45 were measured on day 64 for all the different trace metal solutions tested (Table 2). On day 82, a 37% higher SMA on methanol was achieved in a medium with complete metal solution compared to a medium with complete metal solution except nickel. Similar SMA values were measured on day 82 and on day 95 for all the trace metal solutions tested (Table 2). On day 110, the SMA on methanol increased with around 25% compared to day 95 for all the different trace metal solutions tested, suggesting a further adaptation of the sludge to methanol (Table 2).

Evolution of the specific methanogenic activity (mg CH4-COD g VSS−1 d−1) with methanol as the substrate as a function of time and trace metal content of the medium. No metal addition (▴), addition of complete trace metal solution except nickel (•), addition of complete trace metal solution (♦), and addition of nickel alone (■). Note that at operation day 165, the UASB reactor was completely acidified and no activity on methanol was measured

On day 129, which was 1 day before the methanol accumulation was observed, the SMA on methanol had decreased to 1.164 g CH4-COD g VSS−1 day−1 in a medium containing the complete trace metal solution except nickel, corresponding to a 31% reduction in SMA compared to day 110 for the same test medium. However, in a medium containing a complete metal solution, the SMA on methanol on day 129 increased to 2.027 g CH4-COD g VSS−1 day−1, corresponding to a 9% higher SMA than on day 110 for the same test medium. No methanogenic activity on acetate was observed either on day 129 or on day 168.

Metal concentration in the sludge

Distinct differences in the retention of cobalt, zinc and copper were observed during the entire experiment, even when these metals were dosed at the same concentration (Table 1). After 60 days of UASB reactor operation at pH 7.2 (Fig. 4D), the cobalt and copper concentrations in the sludge had increased by about 2.5 and 4.5 times, respectively. From day 60 to 110, the cobalt concentration slightly decreased, while the copper concentration increased about seven times compared to the initial concentration in the seed sludge. The nickel and zinc concentrations in the sludge were stable over time during the first 110 days of operation, whereas, the iron concentration halved over the same period (Fig. 6, Table 3).

A decrease in concentration of all the measured metals occurred between day 110 and 134, at the same time that methanol accumulated and a small pH drop (from 7.25 on day 110 to 6.90 on day 134) occurred (Fig. 4D). The cobalt and nickel concentration on day 134 was about three times lower than the concentration on day 110. In the same period, the zinc and iron concentration decreased by 50%, while the copper concentration decreased with only 20% (Fig. 6, Table 3).

During acetate accumulation (PII, days 134–169), the cobalt, copper, and zinc content of the sludge increased slightly. In the same period, the nickel and iron concentration slightly decreased. The nickel concentration in the sludge doubled between days 169 (1 day after initiation of continuous nickel addition) and 191 (conclusion of the trial).

Evolution of key microbial population

Genus-specific hybridizations with the Sarci551 probe revealed a temporal evolution of the Methanosarcina populations in the reactor. In the seed sludge, Sarci551-positive cells were typically observed in densely packed clusters (Fig. 7A). The distribution pattern of Methanosarcina cells in the granules was dynamic during the start-up period, and more dispersed cells were observed on day 35 (Fig. 7B) than in the seed sludge. However, the relative abundance of hybridized cells appeared constant and was similar on day 35 compared to the seed sludge.

An increased abundance of Sarci551-positive cells was detected in the biomass by day 110 (Fig. 7C). Sarci551-positive cells were typically observed in loosely packed clusters by day 110, but they were less dispersed than on day 35. A reduction in the number of Sarci551-positive cells was evident by day 168, with fewer cells, which were more dispersed, rather than in clusters, and which, interestingly, were concentrated around the periphery of the sections (Fig. 7D). The relative abundance of hybridized cells on day 191 (Fig. 7E) was similar to day 168 (Fig. 7D). However, specimens examined on day 191 indicated that the Sarci551 cells were mainly packed in clusters or microcolonies of cells, also mainly located in the periphery of the granule cross sections.

Kinetic parameters of the nickel-limited granular sludge

The SMAmax of the sludge in the medium containing NiEDTA2− (2.62 g CH4-COD g VSS−1 day−1) was 20% higher than the medium with NiCl2 (3.08 g CH4-COD g VSS−1 day−1). The \(K_{\rm m}^{\prime}\) values of the UASB granules show that the nickel concentration required to overcome the limitation on nickel is low: 0.16 and 0.18 μM of Ni2+ for NiCl2 and NiEDTA2−, respectively (Fig. 8A). This corresponds to a free nickel concentration in the liquid medium of, respectively, 2 × 10−3 and 1 × 10−7 μM of Ni2+ for NiCl2 and NiEDTA2−.

(A) Effect of nickel concentration on the specific methanogenic activity with methanol as the substrate of nickel limited sludge (sampled on day 137). Nickel added as NiCl2 (■) and NiEDTA2− (♦). (B) Evolution of dissolved nickel added as NiEDTA2− (◊) during methanol (Δ) conversion to methane (━). (C) Evolution of dissolved nickel added as NiCl2 (♦) during methanol (▴) conversion to methane (━)

The evolution of the dissolved nickel concentration during a methanogenic activity test was different when nickel was dosed as NiEDTA2− (Fig. 8B) or as NiCl2 (Fig. 8C). Already 10 h after of the start of the experiment, the dissolved nickel concentration when nickel was added as NiCl2 was only 20% of the total added nickel, whereas 105% of the total added nickel was presented as dissolved nickel when it was added as NiEDTA2−. The dissolved nickel in the experiments decreased during the period with methylotrophic methanogenic activity at a rate of about 1.6 nM h−1 and about 5 nM h−1 for, respectively, NiCl2 and NiEDTA2−. After the activity had finished and substrate was consumed the rate decreased up to 1.6 nM h−1 in the experiment with NiEDTA2− (Fig. 8B). Interestingly, a slow nickel re-dissolution took place at a rate of about 0.3 nM h−1 in the experiment with NiCl2 upon completion of the methane production (Fig. 8C).

Discussion

Methanogenesis under nickel-limiting conditions

This study shows that lack of nickel in the influent reduces the methanol removal efficiency of methanol-fed anaerobic granular sludge bioreactors, and, ultimately, leads to reactor acidification. Under non-limiting conditions, methylothrophic methanogens, such as Methanosarcina (Florencio et al. 1995), are the predominant methanol-degrading population in mesophilic methanol-fed anaerobic granular sludge bioreactors. In the present study, nickel depletion led to a reduced SMA on methanol (Fig. 5) and, consequently, to methanol accumulation in the effluent after 140 days of operation (Fig. 4). Moreover, the nickel limitation occurred in a similar way as for cobalt shown by Fermoso et al. (2008), according to the algorithm presented in Fig. 3. Apparently, the shorter operation time and the higher OLR applied in this study did not allow the induction of a nickel independent pathway, as proposed by Zandvoort et al. (2002b). The time period required to achieve nickel limitation, as also observed by Zandvoort et al. (2002b), is much longer compared to that required for cobalt: at an OLR of 5 g COD l−1 day−1, cobalt limitation is achieved in 15 days (Fermoso et al. 2008).

In the present study, the SMA on methanol in the absence of nickel on day 110 was similar to the SMA in the presence of nickel and three times higher than the SMA on methanol in the absence of nickel on day 35 (Table 2). FISH data provided an ecological basis for this three times higher SMA: the abundance of Methanosarcina cells on day 110 was higher than in the seed sludge and on day 35 (Fig. 7B, C). The same increase in Methanosarcina cell number over time was also found in a stable methanogenic methanol-fed UASB (pH 7, 30°C, 5 g COD l−1 day−1) (Fermoso et al. 2008). The increased SMA during PI is most likely due to biomass adaptation to the substrate, as evidenced by the increase in activity (Table 2) and Methanosarcina abundance (Fig. 7).

Kida et al. (2001) observed that the methanogenic activity with acetate as the substrate (pH 7, 37°C), as well as F 430 and corrinoid concentrations in methanogenic mesophilic biomass from a sewage treatment plant decreased with decreasing amounts of Ni2+ and Co2+ added. The omission of nickel might thus result in a reduced amount of coenzyme F 430, thereby decreasing the SMA of the sludge. In the present study, the reduced SMA in the absence of nickel was not observed until day 129. The initial concentration of nickel in the seed sludge (43 μg g TSS−1; Table 3) was probably enough to support the enzymatic activity and synthesis of coenzyme F 430 for a considerably long time, even if the Methanosarcina population increased. Moreover, many organisms respond to lower metal bioavailability by an increased synthesis of metals transporters (Sunda and Huntsman 1998). This type of adaptation to low nickel concentrations might also have contributed to the longer time-period before a decrease in methylotrophic activity is observed.

Methanogenesis with different nickel species

Nickel bound to EDTA4− induced a similar \(K_{\rm m}^{\prime}\), but higher SMAmax of the nickel limited sludge with methanol as the substrate than nickel chloride (Fig. 8). This disagrees with the assumption that the free metal species is the bioavailable fraction in a biofilm system (Worms et al. 2006) as the initial free nickel concentration in NiEDTA2− amended medium is much lower (<0.1%) compared to NiCl2 (c.a. 28%) amended medium. This discrepancy might be due to the formation of different nickel species in the batch test medium or granular matrix that alter the metal bioavailability. Indeed, a lower total dissolved nickel concentration was measured in the nickel chloride activity test medium (Fig. 8C). For example, sulfide ions, which are always present in the granular sludge (van Hullebusch et al. 2003), may react with the free nickel ions to form metal sulfides. As the free nickel concentration is higher with nickel chloride than with nickel bound to EDTA4−, more nickel sulfide will be formed in the nickel chloride medium. Osuna et al. (2004), using a sequential extraction protocol with the same seed sludge as used in the present study, showed that nickel is mainly present in the sulfide fraction. The latter is a strongly bound fraction, which could make nickel less available for the methanogens (Jansen et al. 2005). In this way, the nickel bound to EDTA4− is less available to nickel sulfide formation and can thus penetrate the granular matrix without precipitation. Local and homogeneous dissociation of nickel bound to EDTA4− within the granule will lead to higher methanogenic activities. Therefore, the addition of nickel bound to EDTA4− or other strong ligands to UASB reactors will facilitate homogeneous distribution of nickel in the sludge present in the reactor.

The bioavailability of metal species depends on the species formed. In a medium with sulfide, carbonates, phosphates, and EDTA4− as the main metal ligands, it is more likely that the EDTA4− determines the nickel bioavailability, and thus nickel remains mainly dissolved (Fig. 8B). However, in a medium with only sulfide, carbonates, and phosphates, precipitation determines the nickel bioavailability (Fig. 8C). Further research is required to confirm this, measuring nickel bioavailability with specific techniques, as, e.g., by the donnan membrane technique (DMT) or diffusive gradient in thin films (DGT) techniques (Kalis et al. 2006).

The retention and bioavailability of the different nickel species in anaerobic reactors should also be taken into account when the HRT in anaerobic reactor operation is shorter than the time to reach physical and chemical equilibrium. This can be done using techniques that give a better understanding of the different metal retention mechanisms, e.g., spectrophotometric measurement of compounds that become fluorescent upon metal complexation, as, e.g., Newport green with nickel (Wuertz et al. 2000). The latter compound becomes a fluorescent molecule when bound to nickel. Using this technique, nickel retention in a biofilm was shown to be not only due to cellular sorption but also to extracellular binding by extracellular polymeric substance.

Acetogenesis under nickel-limiting conditions

Once the methanol accumulation surpasses a threshold value (about 18 mM in the present study; Fig. 4), acetogens outcompeted methanogens for methanol. This is due to the higher affinity of acetogens for methanol at high methanol concentrations (Florencio et al. 1995). Methanol accumulation was followed by acetate accumulation, similar to the algorithm of cobalt limitation of methanol-fed UASB reactors (Fermoso et al. 2008), even when nickel and cobalt are components of different enzymes in the anaerobic methanol degradation (Fig. 1B). This suggests that even other metals present in the enzyme system involved in methanol degradation could follow the same algorithm as well, e.g., iron which is present in heterodisulfide reductase (Deppenmeier et al. 1999) or zinc which is present in coenzyme M methyltransferase (Sauer and Thauer 2000).

Florencio et al. (1995), working with a methanol fed UASB reactor (pH 7.0 and 30°C), concluded that even if enough bicarbonate and cobalt are supplied to the media, significant acetate formation will occur when the effluent methanol concentration would exceed 20 mM in case of, e.g., overloading of the reactor or other metal deficiency. Therefore, maintenance of the SMA high enough to keep the methanol effluent concentration low is required to maintain methanol-fed UASB reactors methanogenic.

Reactor recovery by nickel addition

The addition of nickel (0.5 μM) to the influent almost instantaneously decreased the acidification and recovered the methanol removal efficiency (Fig. 4). The decreased VFA accumulation and complete methanol removal in these last days of operation (Fig. 4), coupled to the lack of acetoclastic methanogenic activity, indicates that methylothrophic methanogens recovered their activity upon the nickel addition. The nickel addition also influenced the Methanosarcina population dynamics inside the granule: the relative abundance of Methanosarcina cells did not change, but after 25 days of nickel addition (day 191) the Methanosarcina cells were much more packed in cluster than after 3 days (day 168) of nickel addition. The aggregation in clusters of methanogens after nickel addition is similar to that observed after 110 days of reactor operation. The growth of methanogens in clusters seems to be correlated with the development of the methanogenic population. Similarly, Fermoso et al. (2008) observed abundant clusters of Methanosarcina cells in a cobalt limited methanogenic methanol-fed UASB reactor during stable operation. Also Sekiguchi et al (1999) showed that methanogenic archaea are mainly present in clusters in sucrose and VFA fed mesophilic granular sludge.

In contrast with the methanogenic reactor recovery upon nickel addition, cobalt addition in a cobalt-deprived reactor enhanced the acetogenic activity of the biomass (Fermoso et al. 2008). This different behavior is probably due to the high cobalt dependence (Bainotti and Nishio 2000), but slightly nickel dependence of the enzymatic system of acetogenesis (Diekert et al. 1981). Thus, in the case of nickel limitation, dosing nickel can enhance methylotrophic methanogenic activity, without boosting acetogenesis.

Conclusions

-

To maintain a methanol-fed UASB reactor methanogenic requires a SMA high enough to keep the effluent methanol concentration low.

-

Nickel limitation can induce a failure of methanol fed UASB reactors due to methanol accumulation and later acidification.

-

Continuous addition of a small amount of nickel (0.5 μM nickel dosed as NiCl2) is enough to recover the methanogenic activity and overcome the acidification of the reactor in a few days of operation.

References

APHA/AWWA (1998) Standard methods for the examination of water and wastewater. USA

Bainotti AE, Nishio N (2000) Growth kinetics of Acetobacterium sp. on methanol-formate in continuous culture. J Appl Microbiol 88(2):191–201

Bobik TA, Olson KD, Noll KM, Wolfe RS (1987) Evidence that the heterodisulfide of coenzyme M and 7-mercaptoheptanoylthreonine phosphate is a product of the methylreductase reaction in Methanobacterium. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 149:455–460

Cook SA, Shiemke AK (1996) Evidence that copper is a required cofactor for the membrane-bound form of methane monooxygenase. J Inorg Biochem 63(4):273

Deppenmeier U, Blaut M, Schmidt B, Gottschalk G (1992) Purification and properties of a F420-nonreactive, membrane-bound hydrogenase from Methanosarcina strain Go1. Arch Microbiol 157(6):505

Deppenmeier U, Lienard T, Gottschalk G (1999) Novel reactions involved in energy conservation by methanogenic archaea. FEBS Lett 457(3):291

Diekert G, Konheiser U, Piechulla K, Thauer RK (1981) Nickel requirement and factor F430 content of methanogenic bacteria. J Bacteriol 148(2):459–464

Ellefson WL, Whitman WB, Wolfe RS (1982) Nickel containing factor F430: chromophore of the methylreductase of Methanobacterium. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 79:3707–3710

Ellermann J, Hedderich R, Böcher R, Thauer RK (1988) The final step in methane formation: investigations with highly purified methyl-CoM reductase (component C) from Methanobacterium thermoautotrophicum (strain Marburg). Eur J Biochem 172(3):669–677

Fermoso FG, Collins G, Bartacek J, O’Flaherty V, Lens P (2008) Acidification of methanol-fed anaerobic granular sludge bioreactors by cobalt deprivation: induction and microbial community dynamics. Biotechnol Bioeng 99(1):49–58

Florencio L, Field JA, Lettinga G (1994) Importance of cobalt for individual trophic groups in an anaerobic methanol-degrading consortium. Appl Environ Microbiol 60(1):227–234

Florencio L, Field JA, Lettinga G (1995) Substrate competition between methanogens and acetogens during the degradation of methanol in UASB reactors. Water Res 29(3):915

Goodwin JAS, Wase DAJ, Forster CF (1990) Effects of nutrient limitation on the anaerobic upflow sludge blanket reactor. Enzyme Microb Technol 12(11):877–884

Hausinger RP (1987) Nickel utilization by microorganisms. Microbiol Rev 51(1):22

Jansen S, Steffen F, Threels WF, vanLeeuwen HP (2005) Speciation of Co(II) and Ni(II) in Anaerobic bioreactors measured by competitive Ligand exchange-adsorptive stripping voltammetry. Environ Sci Technol 39(24):9493–9499

Kalis EJJ, Weng LP, Dousma F, Temminghoff EJM, VanRiemsdijk WH (2006) Measuring free metal ion concentrations in situ in natural waters using the Donnan membrane technique. Environ Sci Technol 40(3):955–961

Kemner JM, Zeikus JG (1994) Purification and characterization of membrane-bound hydrogenase from Methanosarcina barkeri MS. Arch Microbiol 161(1):47

Kida K, Shigematsu T, Kijima J, Numaguchi M, Mochinaga Y, Abe N, Morimura S (2001) Influence of Ni2+ and Co2+ on methanogenic activity and the amounts of coenzymes involved in methanogenesis. J Biosci Bioeng 91(6):590–595

Mulrooney SB, Hausinger RP (2003) Nickel uptake and utilization by microorganisms. FEMS Microbiol Rev 27(2–3):239–261

Oleszkiewicz JA, Sharma VK (1990) Stimulation and inhibition of anaerobic processes by heavy-metals—a review. Biol Waste 31(1):45–67

Osuna MB, van Hullebusch ED, Zandvoort MH, Iza J, Lens PNL (2004) Effect of cobalt sorption on metal fractionation in anaerobic granular sludge. J Environ Qual 33(4):1256–1270

Sauer K, Thauer RK (2000) Methyl-coenzyme M formation in methanogenic archaea: Involvement of zinc in coenzyme M activation. Eur J Biochem 267(9):2498–2504

Schramm A, de Beer D, Wagner M, Amann R (1998) Identification and activities in situ of Nitrosospira and Nitrospira spp. as dominant populations in a nitrifying fluidized bed reactor. Appl Environ Microbiol 64(9):3480–3485

Sekiguchi Y, Kamagata Y, Nakamura K, Ohashi A, Harada H (1999) Fluorescence in situ hybridization using 16S rRNA-targeted oligonucleotides reveals localization of methanogens and selected uncultured bacteria in mesophilic and thermophilic sludge granules. Appl Environ Microbiol 65(3):1280–1288

Singh RP, Kumar S, Ojha CSP (1999) Nutrient requirement for UASB process: a review. Biochem Eng J 3(1):35

Sorensen AH, Torsvik VL, Torsvik T, Poulsen LK, Ahring BK (1997) Whole-cell hybridization of Methanosarcina cells with two new oligonucleotide probes. Appl Environ Microbiol 63(8):3043–3050

Speece RE, Parkin GF, Gallagher D (1983) Nickel stimulation of anaerobic digestion. Water Res 17(6):677–683

Sunda WG, Huntsman SA (1998) Processes regulating cellular metal accumulation and physiological effects: phytoplankton as model systems. Sci Total Environ 219(2–3):165–181

Thauer RK (1998) Biochemistry of methanogenesis: a tribute to Marjory Stephenson. 1998 Marjory Stephenson Prize Lecture. Microbiology 144(9):2377–2406

van Hullebusch ED, Utomo S, Zandvoort MH, Lens PNL (2005) Comparison of three sequential extraction procedures to describe metal fractionation in anaerobic granular sludges. Talanta 65(2):549

van Hullebusch ED, Zandvoort MH, Lens PNL (2003) Metal immobilisation by biofilms: mechanisms and analytical tools. Rev Environ Sci Biotechnol 2(1):9

Wallner G, Amann R, Beisker W (1993) Optimizing fluorescent insitu hybridization with ribosomal-rna-targeted oligonucleotide probes for flow cytometric identification of microorganisms. Cytometry 14(2):136–143

Weijma J (2001) Methanol conversion in high-rate anaerobic reactors. Water Sci Technol 44(8):7

Weng LP, Van Riemsdijk WH, Temminghoff EJM (2005) Kinetic aspects of donnan membrane technique for measuring free trace cation concentration. Anal Chem 77(9):2852–2861

Worms I, Simon DF, Hassler CS, Wilkinson KJ (2006) Bioavailability of trace metals to aquatic microorganisms: importance of chemical, biological and physical processes on biouptake. Biochimie 88(11):1721

Wuertz S, Müller E, Spaeth R, Pfleiderer P, Flemming HC (2000) Detection of heavy metals in bacterial biofilms and microbial flocs with the fluorescent complexing agent Newport Green. J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol 24(2):116–123

Zandvoort MH, Geerts R, Lettinga G, Lens PNL (2002a) Effect of long-term Cobalt deprivation on methanol degradation in a methanogenic granular sludge bioreactor. Biotechnol Prog 18(6):1233

Zandvoort MH, Osuna MB, Geerts R, Lettinga G, Lens P (2002b) Effect of nickel deprivation on methanol degradation in a methanogenic granular sludge reactor. J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol 29:268–274

Zandvoort MH, van Hullebusch ED, Gieteling J, Lens PNL (2006a) Granular sludge in full-scale anaerobic bioreactors: trace element content and deficiencies. Enzyme Microb Technol 39(2):337

Zandvoort MH, van Hullebusch ED, Golubnic S, Gieteling J, Lens PNL (2006b) Induction of cobalt limitation in methanol-fed UASB reactors. J Chem Technol Biotechnol 81(9):1486–1495

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by the Marie Curie Excellence Grant “Novel biogeological engineering processes for heavy metal removal and recovery” (MEXT-CT-2003-509567). The authors thank Dr. Eric van Hullebusch and Dr. Marcel Zandvoort for valuable discussions during the preparation of the manuscript.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Fermoso, F.G., Collins, G., Bartacek, J. et al. Role of nickel in high rate methanol degradation in anaerobic granular sludge bioreactors. Biodegradation 19, 725–737 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10532-008-9177-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10532-008-9177-3