Abstract

Tigers are one of the most recognized and charismatic predator on earth, yet their habitats have declined, their numbers are low, and substantial threats to their survival persist. Although, tiger conservation is high priority globally and tigers are generally considered well studied, there has been no comprehensive global assessment of tiger-related publications aimed at identifying trends, assessing their status and pinpointing research gaps. Utilizing PRISMA framework, we conducted an extensive search across multiple databases, including Scopus, Web of Science, and ScienceDirect, to gather research related to Bengal tigers. Following thorough screening, we selected and evaluated 491 articles published between 2010 and 2022 to address these issues. The results show that publications on Bengal tigers have steadily on rise, with an average of 40 papers/year within this period. We found that most research was focused on the theme of tiger biology. Information on leopards and dholes was also frequently associated with tiger research. The highest number of lead authors originated from India (n = 192), where most research was also conducted. Authors from USA (n = 111) and UK (n = 38) were the next most productive, even though tigers are not found in or anywhere near these countries. We demonstrate that there is only limited amount of transboundary research, and that relatively little tiger research is conducted in the forests beyond protected areas. Similarly, very important but the least studied themes ─Poaching, Population and Socio-culture dimension should be the priority of future research efforts. Additionally, research on tourism, economic aspects and technological inputs are essential for the sustainable conservation of Bengal tigers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Tigers (Panthera tigris) are the largest of all living felids, Asia’s largest terrestrial predator, and one of the most recognizable and charismatic species on earth (Sunquist 1981; Seidensticker and McDougal 1993). They were historically classified into nine sub-species (GTI 2011), with a recent genetic evolutionary analysis by Liu et al. (2018) identifying six extant sub-species (Bengal tiger, Amur tiger, South China tiger, Sumatran tiger, Indochinese tiger, and Malayan tiger) and three extinct sub-species (Javan tiger, Bali tiger, and Caspian tiger). The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) red list identifies tigers as an ‘endangered’ species, and the Convention on International Trade of Endangered Species of Flora & Fauna (CITES) has retained tigers in Appendix I (CITES 2022), thereby prohibiting or regulating their international trade. The historical distribution of tigers once ranged from Eastern Turkey to the sea of Japan and throughout southeast Asia including many large Asian islands (Seidensticker et al. 1999), but their density and range has now contracted to a suite of relatively small patches throughout this former range. Tiger populations are thought to remain in just 13 tiger range countries (TRCs) including Bangladesh, Bhutan, Cambodia, China, India, Indonesia, Lao PDR, Malaysia, Myanmar, Nepal, Russia, Thailand and Vietnam (GTI 2011), although Goodrich et al. (2022) showed that tigers have vanished completely from Cambodia, Lao PDR and Vietnam. The global population of tigers is currently estimated to be between 3,726 and 5,578 individuals, located in only 10 tiger range countries (Goodrich et al. 2022). Tigers remain a species of high conservation value.

Tigers are also an umbrella species, which means that their presence is associated with relatively healthy ecosystems, and tiger-focused conservation can therefore benefit multiple species at lower trophic levels (Karanth 2003; GTI 2011). Tigers are now facing substantial environmental challenges, climate change, population growth and infrastructure development (Seidensticker 2010). South China tigers exist only in captivity while Amur, Malayan and Indochinese tigers exist only between 150 and 250 in number and Sumatran tiger constitute ∼ 600 individuals (Jhala et al. 2021). Most sub-species retain very small population that are not expected to persist. However, the Bengal tiger is by far the largest population and can be found in Bangladesh, Bhutan, India and Nepal, where ∼ 3,800 animals exist (GTI 2011). Understanding the trends and status of research on Bengal tigers is critical to ensuring that conservation effort and resources are allocated wisely, for the benefit of tigers and the many other species that coexist with them in tiger-suitable habitats.

Here, we review Bengal tiger studies published globally between 2010 and 2022, focusing on research themes, as well as spatial and temporal publication trends. Previous reviews have focused on limited areas and themes (Sarkar et al. 2021a; Yadav et al. 2022). For example, country-specific reviews from India (Rastogi et al. 2012) and Nepal (Ghimire 2022) have also focused on just one theme tiger conservation. Other reviews focusing on tiger pheromones (Brahmachary and Poddar-Sarkar 2015), conservation status (Kumar 2021; Sarkar et al. 2021a) and recovery (Seidensticker 2010) have also been carried out in the past, but none of these sought to synthesize the breadth of work similar with what we have undertaken here. Similar reviews to our have recently been conducted for greater one-horned rhinoceros Rhinoceros unicornis (Pant et al. 2020), red panda Ailurus fulgens (Karki et al. 2021), and various large felids and other mammals (Ghosal et al. 2013; Akash and Zakir 2020; Bist et al. 2021; Srivathsa et al. 2022). Our work therefore expands the breadth and depth of these reviews, necessary for identifying global trends and status of Bengal tiger research.

Consequently, our aims are to (1) examine the number and geographic distribution of studies, including the types and sources of those studies, as well as institutional and research collaboration; (2) examine the primary themes and sub-themes discussed; and (3) identify important gaps in the current knowledge. We hope that this review will give direction towards future research and conservation efforts for Bengal tigers, and related sub-species.

Materials and methods

Literature search strategies

We followed the systematic literature review approach demonstrated by Pant et al. (2020) and Karki et al. (2021), which is based on the recommendations of Pullin and Stewart (2006) and the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA ) framework described by Moher et al. (2009). Peer reviewed articles published in English between 2010 and 2022 in three web-based databases (i.e., − Scopus, Web of Science and Science Direct) were searched for the following terms: “Tiger” OR “Bengal tiger” OR “Panthera tigris tigris”.

Article selection criteria

Our literature search returned 35,744 articles. We then examined the article title, abstract and keywords of each article and only retained peer-reviewed empirical and review articles on wild and captive Bengal tigers. Irrelevant articles associated with fish, plants, insects, entertainment and sports were excluded. This resulted in sourcing 2,118 articles in Scopus, 1,744 in Web of Science, and 767 in Science Direct database after applying our first level of exclusion criteria (see Supplementary Material, Table 1). All the duplicates were then removed by combining all articles in “Zotero” software, followed by re-screening each article by title and abstract to further exclude irrelevant articles related to other species. Tiger related articles were then segregated at the sub-species level for further analysis. Articles related to the other five sub- species of tiger were excluded, and only articles related to Bengal tigers were used for our analysis. Thus, we chose to review a total of 491 articles about Bengal tigers (see Supplementary Material, Fig. 1). These articles encompass non-specified sub-species as well as review papers.

Data compilation and analysis

We categorized each article according to publication year, authors, country of research (i.e. where the work originated from), journal of publication, data types, and thematic areas for our analysis (see Supplementary Material, Table 2). We defined ‘primary data’ to reflect empirical studies based on original data generated by researchers through surveys, questionnaires and/or experiments, and ‘secondary data’ to reflect empirical studies based on data originally generated by others. The thematic areas adopted by Pant et al. (2020) and Karki et al. (2021) were considered for this review as well, and were further reclassified into sub-themes for critical appraisal. The thematic areas we assessed were broadly categorized into eight themes−: habitat, biology, population, conflict, genetics, poaching, socio-cultural dimension, and general (Table 1). The data frame with the specified categories are presented in detail in the Supplementary Material, Table 2. The analysis of qualitative data was performed using VOSviewer software, and spatial information was displayed using ArcGIS 10.2, while descriptive quantitative data were analyzed using Microsoft Excel.

Why 2010 to 2022?

A global tiger workshop was held in October 2009 in Kathmandu, Nepal with a theme “Saving wild tiger is our test; if we pass, we get to keep the planet” which was attended by more than 250 tiger experts from 13 tiger Range Countries (TRCs). The workshop recommended celebrating 2010 as the year of tiger throughout the world. The recommendation was carried forward to the First Asian Ministerial Conference on Tiger Conservation (1st AMC) which was held in January 2010 in Hua Hun, Thailand, which set the ambitious goal of total protection of critical tiger habitats and doubling the global number of wild tiger (TX2) by 2022 in the 13 TRCs. Similarly, the follow-up meeting amongst TRCs and experts held in July 2010 at Bali, Indonesia solidified the foundation for doubling tiger numbers and creating a Global Tiger Recovery Program. Finally, in November 2010, the first “Tiger Summit” or International Tiger Conservation Forum was held at St Petersburg, Russia. The significant declarations and outputs of this summit were (1) to double the number of wild tigers across their range by 2022, (2) endorse the Global Tiger Recovery Program (2010–2022), and (3) celebrate 29th July as global tiger day across the world. Hence, the year 2010 is a pivotal year for the history of tiger conservation throughout the world, and 2022 represents the global benchmark denoting the date that many of the proposed goals should have been achieved by. The global tiger number is presented in Supplementary Material, Table 3.

Results

Spatial and temporal trends of research

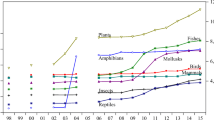

The number of Bengal tiger studies published annually has increased over time (Fig. 1a). The fewest number of studies were published in 2010 (n = 22), while the highest number of studies were published in 2022 (n = 61).

Most studies were geographically focused on India (n = 256), followed by Nepal (n = 56) and Bangladesh (n = 22) (see Supplementary Material, Fig. 2a) and 53 studies were not specific to any country or area. A total of 12 studies were conducted at a transboundary level covering two or more TRCs, and only 13 studies were conducted across all TRCs. Tiger research from the USA, Australia, UK, Italy, France, Germany, Pakistan and other non-TRCs were mainly associated with captive tigers and illegal trade.

Research types and duration

Of the 491 articles we reviewed, ∼75% of them were empirical studies based on primary data and ∼22% of them were based on secondary data; ∼5% of the studies were based on use of both primary and secondary data. Of the empirical studies that mentioned duration (n = 252), most of them were short-term studies with the study periods of < 6 months (Fig. 1b). Approximately 87% of the studies focused on wild tigers, ∼11% focused on captive tigers, and ∼3% focused on both. Most of the studies on captive tigers were carried out in the USA (n = 16) and India (n = 10), followed by Australia (n = 7) and China (n = 6).

Thematic fields

We have categorized the research into wide range of themes and sub theme. Thematic diversity increased over time (see Yadav et al. 2022). Between 2010 and 2022, Biology (∼22%) was the most common research theme, followed by Genetics (∼16%), Conflict (∼14%) and Habitat (∼12%); Poaching (∼7%) was the least studied theme (Table 1). The General category included studies on conservation and collaboration, review papers, technologies, history, veterinary and economic analysis.

Biology

Bengal tiger biology was the most studied theme (∼22% of studies). Within this theme, dietary (n = 42) aspect of their biology was the most studied (Aziz et al. 2020; Lahkar et al. 2020; Letro et al. 2022; Pun et al. 2022), followed by behavior (n = 28) (Sarkar et al. 2021b; Singh et al. 2020) and physiology (n = 22) (Singh et al. 2014; Williams et al. 2015; Long et al. 2017; Pereira et al. 2022). Tiger interactions (n = 13) with other wild animals was the least studied aspects in this theme (Ullas Karanth et al. 2017; Bhandari et al. 2021; Thapa et al. 2021).

Genetics

Within the genetics theme, most research centered on species and individual identification (n = 37) (Nittu et al. 2021; Jiang et al. 2020; Dalton et al. 2020; Karmacharya et al. 2018), followed by diversity (n = 28) (Aziz et al. 2022; Mondol et al. 2013; Naidenko et al. 2019; Thapa et al. 2018). Population estimation (n = 3) (Aziz et al. 2017; Aylward et al. 2022) and faecal and blood analysis (n = 6) (Shrivatav et al. 2012; Parnell et al. 2015; Kumari Patel et al. 2021) studies were also undertaken. Many genetic-related studies originated from non-TRCs such as Australia, Korea, USA, UK and South Africa.

Conflict

Conflict was the third most studied theme. Within this category, over 50% of the research (n = 38) were related with human and tiger conflict (Karanth et al. 2012; Sharma et al. 2020; Shahi et al. 2022) including some other species like leopard (Panthera pardus) and dhole (Cuon alpinus). Conflict associated with interactions (n = 12) (Penjor et al. 2022; Puri et al. 2022b; Carter et al. 2022) such with infrastructures were also undertaken. Livestock depredation by tigers (Borah et al. 2018; Letro and Fischer 2020; Li et al. 2020) were studied from Bhutan, Nepal, India and China. Coexistence (Inskip et al. 2016; Rakshya 2016; Badola et al. 2021) was the least studied aspect with the ‘conflict’ theme .

Habitat

A total of 58 studies focused on the habitat theme, including studies on species distribution (n = 17) (Hossain et al. 2018; Mohan et al. 2021; Shrestha et al. 2022; Vernes et al. 2022), connectivity (n = 17) (Mondal and Nagendra 2011; Kanagaraj et al. 2013; Schoen et al. 2022), habitat suitability (n = 14) (Kanagaraj et al. 2011; Carter et al. 2013; Thinley et al. 2021), threats (n = 6) (Aziz et al. 2013; Saxena and Habib 2022) and climate change impacts (n = 3) (Deb et al. 2019; Mukul et al. 2019; Rather et al. 2020). The few studies related to climate change effects on habitat were originated from India, Nepal, and Bangladesh.

Socio cultural

Socio-Cultural themed studies (n = 40) covered a wide variety of subjects, including people’s perceptions of tigers (n = 21) (Carter and Allendorf 2016; Doubleday and Rubino 2022; Dhungana et al. 2022), and research related to tourism (n = 12) (Ghosh and Uddhammar 2013; Thapa et al. 2017a; Macdonald et al. 2017), investigations into tradition practices (n = 5) (Liu et al. 2016; Saif et al. 2016), and ecosystem services (n = 2) (Zabel and Engel 2010; Bhattarai et al. 2021).

Population

A total of 34 studies focused on the population theme, and within this, studies on tiger density (n = 27) (Harihar et al. 2017, 2020; Thapa and Kelly 2017; Tempa et al. 2019) emerged as the most extensively researched subject. A limited number of studies also focused on tiger diversity (n = 4) (Debata and Swain 2018; Ahmed et al. 2021) and dispersal (n = 3) (Singh et al. 2013; Thapa et al. 2017b; Lamichhane et al. 2018).

Poaching

Poaching (n = 32) was the least studied theme, even though we included poaching related articles wherever tiger sub-species was unknown. Poaching studies concentrated on tiger trade (n = 18) (Li and Hu 2021; Khanwilkar et al. 2022; Dang Vu et al. 2022), illegal killing (n = 11) (Saif et al. 2018; Davis et al. 2020) and illegal wildlife trade network (n = 3) (Patel et al. 2015; Paudel et al. 2020; Domínguez et al. 2022) connection of criminal groups in and out of the country.

General

Articles that could not be classified under the previous themes were categorized under the General theme (n = 81). These could be further classified into groups that focused on conservation-related studies (n = 14) (Wikramanayake et al. 2011; Harihar et al. 2018; Puri et al. 2022a), reviews (n = 14) (Seidensticker 2010; Akash and Zakir 2020; Srivathsa et al. 2022), tiger recovery (n = 5) (Wilting et al. 2015; Gubbi et al. 2016; Karanth et al. 2020), technology (n = 5) (Miller et al. 2010; Maheswari et al. 2022), veterinary associated topics (Guthrie et al. 2021; McCauley et al. 2021; Kadam et al. 2022) and other subjects (n = 23) (Yamaguchi et al. 2013; Sadath et al. 2013; Kafey et al. 2014; Whitfort 2019; Sanderson et al. 2019; Nayak et al. 2020) included articles related to economic analysis, farming and history.

Journals, authors and affiliations

Journals

We identified 171 journals which published articles pertaining to Bengal tigers. Among these, the highest number of publications (∼9%, n = 37) were found in PLoS ONE, followed by Biological Conservation with around (6%, n = 27) and Oryx (∼5%, n = 23; Fig. 1c). The top eleven publishing journals, primarily from Europe and USA, are categorized as Q1 and Q2 publications.

Country of first author, affiliation and co authorship

We identified first authors from 34 different counties, with ∼38% (n = 192) from India and ∼25% (n = 111) from the USA and ∼8% (n = 38) from the UK ( see Supplementary Material, Fig. 2b). About 74% of these studies were conducted by first authors based within the same country where the research was undertaken. Although ∼18% of the first authors were not based in the country of research, a substantial portion of such studies involved co-authors who were situated in the country where the research was conducted.

We further found that authors from India have collaborated with the highest number of co-authors, closely followed by those from Nepal. We also identified the presence of eight author groups engaged in collaborative efforts (Fig. 2). Among these, we found two distinguishable groups: one with five interconnected clusters highly interlinked with prominent researchers from India, and another group with three clusters highly interlinked with the prominent researchers from Nepal, USA and India.

Key word co-occurrence analysis

Keyword analysis revealed that obvious words such as ‘tiger’ and ‘Panthera tigris’ were most frequently used words (> 100 times) in titles and abstracts of published articles (Fig. 3), but ‘protected area’, ‘endangered species’, ‘conservation’, ‘human’ and ‘biodiversity’ also featured heavily.

Discussion

Spatial and temporal trend of research

The average annual publications count (n = 40) is higher than the greater one-horned rhinoceros and red panda (Pant et al. 2020; Karki et al. 2021), which are also of great conservation concern in the same region (Fig. 1a).

Although most research is conducted in India, Nepal and Bangladesh (see Supplementary Material, Fig. 2a), researchers from Nepal and Bangladesh are less prominent as lead authors compared with those from India, the USA and UK (see Supplementary Material, Fig. 2b). Causes of this are unknown, but may be associated with funding and/or publication biases. Bhutan is underrepresented on both counts, necessitating greater attention on tigers there from both perspectives.

Although many contiguous protected areas exist among India-Nepal, India-Bangladesh and India-Bhutan, where tigers are moving freely across them, yet there is a surprising lack of cross-country or transboundary studies (Harihar et al. 2017; Naidenko et al. 2019; Sharma et al. 2020). This limited number of transboundary research may be due to the complexity of tiger management regimes and lack of transboundary coordination. This barrier must be overcome if tiger conservation efforts are to succeed in the future.

Research types and duration

Three-quarters of the research conducted relied on primary data sources indicating the trustworthy research trend of Bengal tigers. The intricate studies such as behavior ecology, effects of climate change, population dynamics, threats, and human-tiger conflict demand long term efforts. Our findings reveal that only 23% of the studies carried out for more than three years (Harihar et al. 2020; Krishnakumar et al. 2022) indicating the scarcity of long term research on those intricate studies. The long term studies on those subjects need to be highlighted in the future. Although, there has been notable research on captive tigers across many countries in non-TRCs (Lefebvre et al. 2020; Pandey et al. 2021), which is positive step. However, it is equally important to conduct captive tiger studies in TRCs as well.

Thematic fields

Biology

The study conducted by Ghosal et al. (2013) indicated that Biology was the most extensively explored theme and still it persists. Under this theme, the dietary aspects were highly investigated across the range countries and the studies showed that wild boar Sus scrofa and sambar Rusa unicolor are the preferred prey (Hayward et al. 2012) of Bengal tigers, while the largest ungulate, Gaur Bos gaurus also played a significant role in the tiger’s biomass consumption (Krishnakumar et al. 2022).

The spatial ecology of tigers, including dispersal (Bhardwaj et al. 2021; Singh et al. 2021) and home range size (Barlow et al. 2011; Majumder et al. 2012) were commonly studied, while the physiological aspect was less studied in the TRCs. The majority of tigers behavior studies were originated from India (Singh et al. 2020; Bhardwaj et al. 2021) with only one from Bangladesh (Barlow et al. 2011). Such type of research is important if the expansion on tiger habitats beyond the protected areas remains as international goal. We did not find any studies directly related to tiger behavior from Nepal and Bhutan, the nations that play vital role in doubling the tiger number.

Concerning species interactions, tigers were mostly studied in association with leopards and dholes, though greater one-horned rhinoceros (Rhinoceros unicornis), Asian elephants (Elephas maximus) and even lion (Panthera leo) interactions have been evaluated (Thuppil and Coss 2013; Williams et al. 2015; Medhi and Saikia 2019; Saikia et al. 2020) However, there remains a dearth of studies regarding tiger interactions with sloth bears (Melursus ursinus) Indian jackals (Canis aureus indicus), and hyenas (Hyaena hyaena), which all share the same habitat.

Genetics

Despite the growing volume of genetic research, a notable gap exists in Bhutan, where such research remains absent. Countries like Bangladesh (Aziz et al. 2022) and Nepal (Karmacharya et al. 2019) yield fewer studies as compared to India. Genetic analysis is widely accepted tool safeguarding species like tigers, both within their natural habitats and in controlled environments (Luo et al. 2010). Investigation into the genetic makeup of populations reveals the adverse effects of inbreeding depression on small population (Khan et al. 2021). Such genetic analysis and population estimation approach studies are still lacking in the counties like Bhutan, Bangladesh and Nepal. Furthermore, the captive tigers studies on genetics were mostly unrelated to TRCs, except few from India (Maity et al. 2022; Dehnhard et al. 2015; Mishra et al. 2014). This suggests that more resourceful and developed countries have taken the lead in such studies. To address this disparity, it is essential to find ways to overcome the research resources and expertise in these TRCs countries.

Some of the genetic studies showed that population isolation is caused by human disturbance, fragmentation and topographic complexity (Reddy et al. 2017, 2019; Thatte et al. 2020). Various studies in landscape genetics have tried to integrate genetic data with landscape features to pinpoint barriers to gene flow (Mondol et al. 2013; Sharma et al. 2013; Yumnam et al. 2014). Such barriers could be overcome by the establishment of habitat corridors and connectivity facilitating of the movement and gene flow of tigers (Kolipakam et al. 2019; Thapa et al. 2018). However, these studies were limited mostly in India and few from Nepal. Such studies focusing on landscape genetics, emphasizing the importance of corridors and connectivity between the adjacent transboundary protected areas, could be a critical areas of study for preserving genetic diversity, which is completely lacking at present.

Conflict

Goodrich (2010) suggested that as tiger populations rise, so does the potential for human-tiger conflicts, and TRCs must proactively address this issue. Various strategies have been proposed to mitigate these conflicts, including prompt compensation, insurance scheme (Dhungana et al. 2016) radio collaring of problematic tigers (Barlow et al. 2013; Dhungana et al. 2016) and payment of ecosystem services (PES) (Khadija et al. 2022). But, some additional mitigating factors such as efficacy of awareness programs and use improved corral for domestic animals are still unexplored.

We noticed fewer studies examining human-tiger interactions resulting to conflicts, particularly due to infrastructures such as roads (Carter et al. 2020; Quintana et al. 2022) at overall context. Following the rapid infrastructure development in the TRCs, such studies need to be further intensified at local level to gain deeper understanding of these issues.

Studies indicates that leopards and dholes tend to avoid tigers (Thinley et al. 2018; Ramesh et al. 2020; Penjor et al. 2022), residing in peripheral forest near human settlements. Consequently, livestock depredation occurred by these animals at the peripheral forest. Thus, these aggravate the potential human –wildlife conflict scenario.

Habitat

Our findings reveal that habitat is the third most studied theme, while Yadav et al. (2022) emphasized habitat and ecology as the most studied theme. We have identified studies that focus on habitats situated at higher altitudes in regions beyond those typically considered suitable for Bengal tigers i.e. India (Mohan et al. 2021), Nepal (Bista et al. 2021; Shrestha et al. 2022) and Bhutan (Dorji et al. 2019). Despite these investigations, the precise cause behind the existence and significance of these high-altitude habitats for tiger populations remains as unexplored aspect of research.

A range of habitat studies were conducted, covering habitat preference by reintroduced tigers (Sarkar et al. 2017), the utilization of agriculture lands as seasonal habitats (Warrier et al. 2020), and assessment of habitat change at different land management regimes in human dominated areas (Carter et al. 2013). Nevertheless, a noteworthy gap persists in study of behavior change of tigers at these distinct habitats. Various studies concluded that infrastructures such as roads and railways (Carter et al. 2020, 2022; Quintana et al. 2022; Saxena and Habib 2022) as well as dam and hydropower projects (Kenney et al. 2014; Palmeirim and Gibson 2021) pose substantial threats to tiger populations. However, studies on the effects of irrigation canals, high tension lines and industries on tigers remains unexplored.

Regarding habitat connectivity, numerous studies have highlighted the importance of corridors and connectivity (Anwar and Borah 2019) and its mapping (Dutta et al. 2016). These studies were limited and only from India and Nepal, thus need to be further intensified across the TRCs. Research prioritizing the identification of threats (Aziz et al. 2013) has identified climate change as another significant threat (Naha et al. 2016). Mukul et al. (2019) found out that the suitable habitat for tiger in Sundarbans will disappear by 2070. Furthermore, climate change studies concerning tigers have often studied with other species like leopards (Rather et al. 2020) and other mammals (Deb et al. 2019). All of these climate change studies use habitat suitability modeling and the consistent outcome of these studies is the projected reduction of suitable habitats of tigers in the future. We found none of studies from Nepal and Bhutan directly related to climate change.

Socio cultural

Few studies have addressed socio-economic issues in the past (Ghosal et al. 2013), and our results also confirm the same result. In the domain of ecosystem services, aspect related with willingness to pay by the visitors of protected areas in Nepal (Bhattarai et al. 2021) and performance payment to tiger-livestock conflict in India (Zabel and Engel 2010) has been conducted. These innovative approaches hold the potential to foster sustainable conservation practices, hence need to be further intensified across the TRCs. The studies exploring traditional knowledge, art and literature, ethics and values, and religion and rituals associated with tigers within diverse communities is currently very insufficient.

Several tourism-related studies (Ghosh and Ghosh 2019; Rao and Saksena 2021) have revealed that it was unable to benefit local communities. But, tourism is often considered as a significant component of both local and national economies due to its substantial multiplier effects. Hence, it should be extensively studied across the TRCs from the prospective of employment generation and promotion of local products, which is still lacking. It has also got some adverse consequences such as threats to local culture and traditions, pollution, and habitat loss. These aspects also need to be explored for better understanding and address the challenges associated with sustainable tourism.

Population

Harihar et al. (2017) suggested that tiger population estimates should be at annual or biennial intervals. To achieve this, Gopalaswamy et al. (2012) emphasized the robustness of combining camera trap data with fecal DNA analysis to obtain more accurate density estimates. However, Harihar et al. (2020) suggested that population increases alone may not reflect tiger conservation success given that prey depletion and human disturbance play the major roles in tiger loss at local levels (Karanth et al. 2011). All of these studies exclusively focused on India. Therefore, it is crucial to investigate the impact of prey depletion and human disturbance on tiger populations at each distinct locality across the range countries. Our investigation revealed that there is a total lack of population-related research from Bangladesh.

In an unprecedented discovery, a study done in China’s Tibet region recorded the presence of Bengal tigers for the first time (Li et al. 2021). We found only limited studies on tiger dispersal in Nepal (Thapa et al. 2017b; Lamichhane et al. 2018) and India (Singh et al. 2013), which revealed that tigers are dispersing from seemingly suitable areas towards seemingly unsuitable or peripheral areas. Causes for this are unknown, but will be important to identify if we are to improve reintroduction success and effectively protect key tiger habitats.

Poaching

Our finding was also consistent with the findings of Yadav et al. (2022) and Bist et al. (2021) from Terai Arc Landscape in which poaching was identified as the least studied theme of tigers globally. Illegal wildlife trade is valued at more than USD$ 20 billion per year (Barber-Meyer 2010), and is multinational in scope (Paudel et al. 2020; Khanwilkar et al. 2022). Some of the studies showed that the efforts towards tiger farming will not stop the demand of wild-sourced products (Rizzolo 2021; Dang Vu et al. 2022). Such studies are limited only in few countries. Rampant snaring is one of the most common threats to large mammals in Southeast Asia (Figel et al. 2021). However, our understanding of various alternative techniques used by hunters at modern world need to be further investigated. Additionally, it is equally crucial to study the economic, social, and cultural factors that drive the behavior of hunters.

Tiger products experience varying degrees of demand. Tiger bone wine is the most demanded product of tiger (Li and Hu 2021) and tiger bone glue is mainly used for medicinal purposes (Davis et al. 2020). Additional items such as tiger skin, claws, bones and teeth are also demanded in markets (Nittu et al. 2022). Given the multinational nature of poaching, the studies originated from TRCs and even USA (Khanwilkar et al. 2022), revealing that China and Vietnam as major suppliers to the USA. Patel et al. (2015)explored China as the pivotal hub for the illegal wildlife trade network involving tigers, rhinos and elephants. Even though, it is complex to investigate organized crime and tough to research and publish, it should be emphasized in future.

Only one study focused on technology known as Management Information System (MIST) (Stokes 2010), which is the computerized management information system designed for ranger-based data collection for law enforcement, was recorded. Conducting additional research on the adopted anti-poaching technologies in countries like India and Nepal, such as Spatial Monitoring and Reporting Tool (SMART), Unmanned Aerial Vehicles(UAVs) and sniffer dogs, has the potential to make significant contributions to the conservation of the species.

General

Assessing the tigers protection using Conservation Assured/Tiger Standards (CA/TS) studies (Pasha et al. 2018; Dudley et al. 2020)provides a useful measuring scale for assessing the progress of conservation efforts. However,, there is not much research on expansion of protected area for tigers, with only one study identified from India (Gubbi et al. 2016, 2017).

The tiger related review papers that we found were primarily concentrates on policy, large felids, and prey species, with majority of these papers originating from India, with an exception from Bangladesh. The recent research conducted on novel technologies for animal detection through video analysis (Maheswari et al. 2022) and utilization of wireless sensor networks to monitor tigers (Badescu and Cotofana 2015), strive to contribute to species conservation and further intensified across the TRCs, particularly addressing the imperative of anti-poaching efforts for tigers in future.

Limited studies within the domain of veterinary science, demonstrated the transmission of canine distemper virus from dogs to tigers (Sidhu et al. 2019), tigers being infected by H5N1 avian influenza virus (He et al. 2015). Further, a broad spectrum of health perspectives could be explored. The recent Tiger summit in Russia also emphasize adoption of one health approach and safeguard against zoonotic disease transmission (VDTC 2022).

Furthermore, economic considerations related research such as the analysis of expenditures (Nayak et al. 2020) in India showed the allocated fund for tiger conservation is not proportionally allocated according to size of park or population of tigers. A financial analysis of tiger conservation in Nepal (Kafey et al. 2014) also found the current level of funding is inadequate. Similar financial gaps could be explored in other countries as well.

Publishing journals, authors, affiliation and key word co-occurrence

In the past 12 years, the research trend has shown a diverse array of journals interested on publishing tiger-related studies (Fig. 1c). All the top eleven journals are from natural science discipline, indicating consistent and valuable publishing trend that need to be continued. However, the dominance of journals originating from the USA and Europe highlights the shortage of journals from TRCs dedicated to tiger research. We found that the highest publisher PLoS ONE (published from USA) may be skewed towards native authors, as there were second highest lead authors from the same country.

As expected universities and research institutes dominate the production of tiger research, and publications attributed to government organizations accounted for less than 10%, reflecting a lower emphasis on research production within government.

The extensive researchers from many nationality, along with good connections of authors or co-authors at the country where research occurred, signifies the robustness of Bengal tigers research. Though, Indian authors demonstrates a strong culture of collaboration among its domestic authors, they should further enhance collaborative efforts with authors from other countries to create stronger links in research endeavors. Despite non-TRCs, the USA holds significant position in terms of authorship and organizational involved. This prominence could likely be attributed to the resource availability and substantial number of academic institutes in the USA.

The topics such as animal behavior, estimation methods, human-wildlife conflict, wildlife trade, ecotourism, economics have been relatively underexplored. It is imperative to focus on these underrepresented topics to advance the understanding on these areas.

Conclusions

We found that the number of publications on Bengal tigers is on upward trajectory every year with wide range of publication outlets. We found that the highest number of research were conducted on biology-theme and lowest on poaching-theme. Our findings highlight a hopeful trend in both wild and captive Bengal tigers research, both within and beyond its geographical range, signifying a positive expansion of knowledge on charismatic species. Based on our analysis, the following key research gaps emerge, necessitating attention and action:

-

1.

To ensure the long-term survival of Bengal tigers, it is essential to address the gaps in transboundary research, mainly at the interconnected forest and protected areas spanning across its range countries. Conducting comprehensive, long-term studies throughout their habitat is essential.

-

2.

A significant gap exists in the behavior study of Bengal tigers within Bangladesh, Bhutan and Nepal, especially long term research to know the behavior of the species in distinct habitats. Furthermore, expanding protected areas for conservation of tigers demands in-depth studies to support future decisions. The interaction of tiger with other species should also be investigated more closely.

-

3.

Genetic research, along with capacity enhancement is a dire need in Bangladesh, Bhutan and Nepal. These endeavors are crucial for a comprehensive understanding of the species and its long term viability.

-

4.

Addressing the gaps in human-tiger conflict management, particularly through the lens of coexistence and infrastructure development aspects is essential. Likewise, a compelling need for intensified research on dispersal of Bengal tigers from their prime habitats in the context of climate change is warranted.

-

5.

The scarcity of research focused on poaching-theme need to be prioritized in the future, especially in the illegal trade networks analysis though found to be difficult task. Similarly, anti-poaching strategy could be bridged through the technological innovation and studies.

-

6.

Emerging areas such as tourism, economic analysis, and veterinary aspects remain relatively unexplored, and should be prioritized.

-

7.

Governments, functioning as policy-maker and field implementing agencies should escalate Bengal tigers research integrating insights from academia for effective conservation of the species. It is important to encourage collaborative research among multinational researchers to promote and expand the scope and knowledge of the tigers across their range.

References

Ahmed T, Bargali HS, Verma N, Khan A (2021) Mammals outside protected areas: Status and Response to Anthropogenic Disturbance in Western Terai-Arc Landscape. Proc Zool Soc 74:163–170. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12595-020-00360-4

Akash M, Zakir T (2020) Appraising Carnivore (Mammalia: Carnivora) studies in Bangladesh from 1971 to 2019 bibliographic retrieves: trends, biases, and opportunities. J Threat Taxa 12:17105–17120. https://doi.org/10.11609/jott.6486.12.15.17105-17120

Anwar M, Borah J (2019) Functional status of a wildlife corridor with reference to tiger in Terai Arc Landscape of India. Trop Ecol 60:525–531. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42965-020-00060-2

Aylward M, Sagar V, Natesh M, Ramakrishnan U (2022) How methodological changes have influenced our understanding of population structure in threatened species: insights from tiger populations across India. Philos Trans R Soc B Biol Sci 377. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2020.0418

Aziz A, Barlow ACD, Greenwood CC, Islam A (2013) Prioritizing threats to improve conservation strategy for the tiger Panthera tigris in the Sundarbans Reserve Forest of Bangladesh. ORYX 47:510–518. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0030605311001682

Aziz MA, Tollington S, Barlow A et al (2017) Using non-invasively collected genetic data to estimate density and population size of tigers in the Bangladesh Sundarbans. Glob Ecol Conserv 12:272–282. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gecco.2017.09.002

Aziz MA, Islam MA, Groombridge J (2020) Spatial differences in prey preference by tigers across the Bangladesh Sundarbans reveal a need for customised strategies to protect prey populations. Endanger Species Res 43:65–73. https://doi.org/10.3354/ESR01052

Aziz MA, Smith O, Jackson HA et al (2022) Phylogeography of Panthera tigris in the mangrove forest of the Sundarbans. Endanger Species Res 48:87–97. https://doi.org/10.3354/esr01188

Badescu A-M, Cotofana L (2015) A wireless sensor network to monitor and protect tigers in the wild. Ecol Indic 57:447–451. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2015.05.022

Badola R, Ahmed T, Gill AK et al (2021) An incentive-based mitigation strategy to encourage coexistence of large mammals and humans along the foothills of Indian Western Himalayas. Sci Rep 11. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-84119-7

Barber-Meyer SM (2010) Dealing with the clandestine nature of wildlife-trade market surveys. Conserv Biol 24:918–923. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1523-1739.2010.01500.x

Barlow ACD, Smith JLD, Ahmad IU et al (2011) Female tiger Panthera tigris home range size in the Bangladesh Sundarbans: the value of this mangrove ecosystem for the species-conservation. ORYX 45:125–128. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0030605310001456

Barlow ACD, Ahmad I, Smith JLD (2013) Profiling tigers (Panthera tigris) to formulate management responses to human-killing in the Bangladesh Sundarbans. Wildl Biol Pract 9:30–39. https://doi.org/10.2461/wbp.2013.9.6

Bhandari A, Ghaskadbi P, Nigam P, Habib B (2021) Dhole pack size variation: assessing the effect of Prey availability and apex predator. Ecol Evol 11:4774–4785. https://doi.org/10.1002/ece3.7380

Bhardwaj GS, Kari B, Mathur A (2021) Utilisation of honey trap method to ensnare a dispersing sub-adult Bengal Tiger Panthera tigris tigris L. in a human dominated landscape. J Threat Taxa 13:19153–19155. https://doi.org/10.11609/jott.6476.13.8.19153-19155

Bhattarai BR, Morgan D, Wright W (2021) Equitable sharing of benefits from tiger conservation: beneficiaries’ willingness to pay to offset the costs of tiger conservation. J Environ Manage 284:112018. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2021.112018

Bist BS, Ghimire P, Nishan K et al (2021) Patterns and trends in two decades of research on Nepal’s mammalian fauna (2000–2019): examining the past for future implications. Biodivers Conserv 30:3763–3790

Bista D, Lama ST, Shrestha J et al (2021) First record of bengal tiger, panthera tigris tigris Linnaeus, 1758 (Felidae), in eastern Nepal. Check List 17:1249–1253. https://doi.org/10.15560/17.5.1249

Borah J, Bora PJ, Sharma A et al (2018) Livestock depredation by Bengal tigers in fringe areas of Kaziranga Tiger Reserve, Assam, India: implications for large Carnivore conservation. Hum-Wildl Interact 12:186–197. https://doi.org/10.26077/ZH6V-PK64

Brahmachary RL, Poddar-Sarkar M (2015) Fifty years of tiger pheromone research. Curr Sci 108:2178–2185

Carter NH, Allendorf TD (2016) Gendered perceptions of tigers in Chitwan National Park, Nepal. Biol Conserv 202:69–77. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2016.08.002

Carter NH, Gurung B, Viña A et al (2013) Assessing spatiotemporal changes in tiger habitat across different land management regimes. Ecosphere 4. https://doi.org/10.1890/ES13-00191.1

Carter N, Killion A, Easter T et al (2020) Road development in Asia: assessing the range-wide risks to tigers. Sci Adv 6. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.aaz9619

Carter N, Pradhan N, Hengaju K et al (2022) Forecasting effects of transport infrastructure on endangered tigers: a tool for conservation planning. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.13472. PEERJ 10:

CITES (2022) Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Flora and Fauna (Appendex I,II &III, 22 june 2022)

Dalton DL, Kotzé A, McEwing R et al (2020) A tale of the traded cat: development of a rapid real-time PCR diagnostic test to distinguish between lion and tiger bone. Conserv Genet Resour 12:29–31. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12686-018-1060-x

Dang Vu HN, Gadbert K, Vikkelsø Nielsen J et al (2022) The impact of a legal trade in farmed tigers on consumer preferences for tiger bone glue – evidence from a choice experiment in Vietnam. J Nat Conserv 65:126088. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnc.2021.126088

Davis EO, Willemsen M, Dang V et al (2020) An updated analysis of the consumption of tiger products in urban Vietnam. Glob Ecol Conserv 22:e00960. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gecco.2020.e00960

Deb JC, Phinn S, Butt N, McAlpine CA (2019) Adaptive management and planning for the conservation of four threatened large Asian mammals in a changing climate. Mitig Adapt Strateg Glob Change 24:259–280. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11027-018-9810-3

Debata S, Swain K (2018) Estimating mammalian diversity and relative abundance using camera traps in a tropical deciduous forest of Kuldiha Wildlife Sanctuary, eastern India. MAMMAL STUDY 43:45–53. https://doi.org/10.3106/ms2017-0078

Dehnhard M, Kumar V, Chandrasekhar M et al (2015) Non-invasive pregnancy diagnosis in big cats using the PGFM (13,14-dihydro-15-keto-PGF2α) assay. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0143958. PLoS ONE 10:

Dhungana R, Savini T, Karki JB, Bumrungsri S (2016) Mitigating human-tiger conflict: an assessment of compensation payments and tiger removals in chitwan national park, Nepal. Trop Conserv Sci 9:776–787. https://doi.org/10.1177/194008291600900213

Dhungana R, Maraseni T, Silwal T et al (2022) What determines attitude of local people towards tiger and leopard in Nepal? J Nat Conserv 68:126223. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnc.2022.126223

Domínguez JLC, Quiroz IA, Martínez MTV, Salazar JIC (2022) Trafficking of a Tiger (Panthera tigris) in northeastern Mexico: a social network analysis. Forensic Sci Int Anim Environ 2:100039. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fsiae.2021.100039

Dorji S, Rajaratnam R, Vernes K (2019) Mammal richness and diversity in a himalayan hotspot: the role of protected areas in conserving Bhutan’s mammals. Biodivers Conserv 28:3277–3297. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10531-019-01821-9

Doubleday KF, Rubino EC (2022) Tigers bringing risk and security: gendered perceptions of tiger reintroduction in Rajasthan, India. Ambio 51:1343–1351. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13280-021-01649-0

Dudley N, Stolton S, Pasha MKS et al (2020) How effective are tiger conservation areas at managing their sites against the conservation assured | tiger standards (Ca|ts)? Parks 26:115–128. https://doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.CH.2020.PARKS-26-2ND.en

Dutta T, Sharma S, McRae BH et al (2016) Connecting the dots: mapping habitat connectivity for tigers in central India. Reg Environ Change 16:53–67. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10113-015-0877-z

Figel JJ, Hambal M, Krisna I et al (2021) Malignant snare traps threaten an irreplaceable Megafauna Community. Trop Conserv Sci 14. https://doi.org/10.1177/1940082921989187

Ghimire P (2022) Conservation of Tiger Panthera tigris in Nepal: a review of current efforts and challenges. J Threat Taxa 14:21769–21775

Ghosal S, Athreya V, Linnell J, Vedeld P (2013) An ontological crisis? A review of large felid conservation in India. Biodivers Conserv 22:2665–2681. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10531-013-0549-6

Ghosh P, Ghosh A (2019) Is ecotourism a panacea? Political ecology perspectives from the Sundarban Biosphere Reserve, India. GeoJournal 84:345–366. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10708-018-9862-7

Ghosh N, Uddhammar E (2013) Tiger, lion, and human life in the heart of wilderness: impacts of institutional tourism on development and conservation in East Africa and India. Conserv Soc 11:375–390. https://doi.org/10.4103/0972-4923.125750

Goodrich JM (2010) Human-tiger conflict: a review and call for comprehensive plans. Integr Zool 5:300–312. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-4877.2010.00218.x

Goodrich J, Wibisono H, Miquelle D et al (2022) Panthera tigris. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2022: e. T15955A214862019

Gopalaswamy AM, Royle JA, Delampady M et al (2012) Density estimation in tiger populations: combining information for strong inference. Ecology 93:1741–1751. https://doi.org/10.1890/11-2110.1

GTI (2011) Global tiger recovery program 2010–2022. Glob Tiger Initiat GTIWashington DC USA

Gubbi S, Mukherjee K, Swaminath MH, Poornesha HC (2016) Providing more protected space for tigers Panthera tigris: a landscape conservation approach in the western ghats, southern India. ORYX 50:336–343. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0030605314000751

Gubbi S, Harish NS, Kolekar A et al (2017) From intent to action: a case study for the expansion of tiger conservation from southern India. Glob Ecol Conserv 9:11–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gecco.2016.11.001

Guthrie A, Strike T, Patterson S et al (2021) The past, present and future of hormonal contraceptive use in managed captive female tiger populations with a focus on the current use of deslorelin acetate. Zoo Biol 40:306–319. https://doi.org/10.1002/zoo.21601

Harihar A, Chanchani P, Pariwakam M et al (2017) Defensible inference: Questioning Global trends in Tiger populations. Conserv Lett 10:502–505. https://doi.org/10.1111/conl.12406

Harihar A, Chanchani P, Borah J et al (2018) Recovery planning towards doubling wild tiger Panthera tigris numbers: detailing 18 recovery sites from across the range. PLoS ONE 13. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0207114

Harihar A, Pandav B, Ghosh-Harihar M, Goodrich J (2020) Demographic and ecological correlates of a recovering tiger (Panthera tigris) population: lessons learnt from 13-years of monitoring. Biol Conserv 252:108848. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2020.108848

Hayward MW, Jedrzejewski W, Jedrzewska B (2012) Prey preferences of the tiger P anthera tigris. J Zool 286:221–231. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7998.2011.00871.x

He S, Shi J, Qi X et al (2015) Lethal infection by a novel reassortant H5N1 avian influenza a virus in a zoo-housed tiger. Microbes Infect 17:54–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.micinf.2014.10.004

Hossain ANM, Lynam AJ, Ngoprasert D et al (2018) Identifying landscape factors affecting tiger decline in the Bangladesh Sundarbans. Glob Ecol Conserv 13:e00382. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gecco.2018.e00382

Inskip C, Carter N, Riley S et al (2016) Toward Human-Carnivore coexistence: understanding tolerance for tigers in Bangladesh. PLoS ONE 11. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0145913

Jhala Y, Gopal R, Mathur V et al (2021) Recovery of tigers in India: critical introspection and potential lessons. People Nat 3:281–293. https://doi.org/10.1002/pan3.10177

Jiang H, Chen W, Su L et al (2020) Impact of host intraspecies genetic variation, diet, and age on bacterial and fungal intestinal microbiota in tigers. MicrobiologyOpen 9. https://doi.org/10.1002/mbo3.1050

Kadam RG, Karikalan M, Siddappa CM et al (2022) Molecular and pathological screening of canine distemper virus in Asiatic lions, tigers, leopards, snow leopards, clouded leopards, leopard cats, jungle cats, civet cats, fishing cat, and jaguar of different states, India. Infect Genet Evol 98:105211. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.meegid.2022.105211

Kafey H, Gompper ME, Spinelli F et al (2014) Alternative financing schemes for tiger conservation in Nepal. Wildl Biol Pract 10:155–167. https://doi.org/10.2461/wbp.2014.10.6

Kanagaraj R, Wiegand T, Kramer-Schadt S et al (2011) Assessing habitat suitability for tiger in the fragmented Terai Arc Landscape of India and Nepal. Ecography 34:970–981. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0587.2010.06482.x

Kanagaraj R, Wiegand T, Kramer-Schadt S, Goyal SP (2013) Using individual-based movement models to assess inter-patch connectivity for large carnivores in fragmented landscapes. Biol Conserv 167:298–309. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2013.08.030

Karanth U (2003) Tiger ecology and conservation in the Indian subcontinent. J Bombay Nat Hist Soc 100

Karanth KU, Gopalaswamy AM, Kumar NS et al (2011) Monitoring Carnivore populations at the landscape scale: occupancy modelling of tigers from sign surveys. J Appl Ecol 48:1048–1056. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2664.2011.02002.x

Karanth KK, Gopalaswamy AM, DeFries R, Ballal N (2012) Assessing patterns of Human-Wildlife conflicts and compensation around a central Indian protected area. PLoS ONE 7. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0050433

Karanth KU, Kumar NS, Karanth KK (2020) Tigers against the odds: applying macro-ecology to species recovery in India. Biol Conserv 252:108846. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2020.108846

Karki S, Maraseni T, Mackey B et al (2021) Reaching over the gap: a review of trends in and status of red panda research over 193 years (1827–2020). Sci Total Environ 781:146659

Karmacharya D, Sherchan AM, Dulal S et al (2018) Species, sex and geo-location identification of seized tiger (Panthera tigris tigris) parts in Nepal—A molecular forensic approach. PLoS ONE 13. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0201639

Karmacharya D, Manandhar P, Manandhar S et al (2019) Gut microbiota and their putative metabolic functions in fragmented Bengal tiger population of Nepal. PLoS ONE 14. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0221868

Kenney J, Allendorf FW, McDougal C, Smith JLD (2014) How much gene flow is needed to avoid inbreeding depression in wild tiger populations? Proc R Soc B Biol Sci 281. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2013.3337

Khadija, Ahmed T, Khan A (2022) Economics of Carnivore depredation: a case study from the northern periphery of Corbett Tiger Reserve, Uttarakhand, India. Acta Ecol Sin 42:68–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chnaes.2021.03.007

Khan A, Patel K, Shukla H et al (2021) Genomic evidence for inbreeding depression and purging of deleterious genetic variation in Indian tigers. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 118. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2023018118

Khanwilkar S, Sosnowski M, Guynup S (2022) Patterns of illegal and legal tiger parts entering the United States over a decade (2003–2012). Conserv Sci Pract 4. https://doi.org/10.1111/csp2.622

Kolipakam V, Singh S, Pant B et al (2019) Genetic structure of tigers (Panthera tigris tigris) in India and its implications for conservation. Glob Ecol Conserv 20:e00710. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gecco.2019.e00710

Krishnakumar BM, Nagarajan R, Selvan KM (2022) Diet Composition and Prey Preference of Tiger, Leopard, and Dhole in Kalakkad-Mundanthurai Tiger Reserve, Southern Western Ghats, India. Mammal Study 47. https://doi.org/10.3106/ms2020-0058

Kumar A (2021) Conservation status of Bengal Tiger (Panthera tigris tigris)-A review. J Sci Res 65:1–5

Kumari Patel S, Biswas S, Goswami S et al (2021) Effects of faecal inorganic content variability on quantifying glucocorticoid and thyroid hormone metabolites in large felines: implications for physiological assessments in free-ranging animals. Gen Comp Endocrinol 310:113833. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ygcen.2021.113833

Lahkar D, Ahmed MF, Begum RH et al (2020) Responses of a wild ungulate assemblage to anthropogenic influences in Manas National Park, India. Biol Conserv 243:108425. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2020.108425

Lamichhane BR, Pokheral CP, Poudel S et al (2018) Rapid recovery of tigers Panthera tigris in Parsa Wildlife Reserve. Nepal ORYX 52:16–24. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0030605317000886

Lefebvre SL, Wallett HM, Dierenfeld ES, Whitehouse-Tedd KM (2020) Feeding practices and other factors associated with faecal consistency and the frequencies of vomiting and diarrhoea in captive tigers (Panthera tigris). J Appl Anim Nutr 8:31–40. https://doi.org/10.3920/JAAN2019.0002

Letro L, Fischer K (2020) Livestock depredation by tigers and people’s perception towards conservation in a biological corridor of Bhutan and its conservation implications. Wildl Res 47:309–316. https://doi.org/10.1071/WR19121

Letro L, Fischer K, Duba D, Tandin T (2022) Occupancy patterns of prey species in a biological corridor and inferences for tiger population connectivity between national parks in Bhutan. ORYX 56:421–428. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0030605320000976

Li J, Hu Q (2021) Using culturomics and social media data to characterize wildlife consumption. Conserv Biol 35:452–459. https://doi.org/10.1111/cobi.13703

Li BV, Reardon K, Satheesh N et al (2020) Effects of livestock loss and emerging livestock types on livelihood decisions around protected areas: case studies from China and India. Biol Conserv 248:108645. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2020.108645

Li X, Bleisch WV, Liu X, Jiang X (2021) Camera-trap surveys reveal high diversity of mammals and pheasants in Medog, Tibet. Oryx 55:177–180

Liu Z, Jiang Z, Fang H et al (2016) Perception, price and preference: consumption and protection of wild animals used in traditional medicine. PLoS ONE 11. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0145901

Liu Y-C, Sun X, Driscoll C et al (2018) Genome-wide evolutionary analysis of natural history and adaptation in the world’s tigers. Curr Biol 28:3840–3849

Long K, Prothero D, Madan M, Syverson VJP (2017) Did saber-tooth kittens grow up musclebound? A study of postnatal limb bone allometry in felids from the Pleistocene of Rancho La Brea. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0183175. PLoS ONE 12:

Luo S-J, Johnson WE, O’Brien SJ (2010) Applying molecular genetic tools to tiger conservation. Integr Zool 5:351–362. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-4877.2010.00222.x

Macdonald C, Gallagher A, Barnett A et al (2017) Conservation potential of apex predator tourism. Biol Conserv 215:132–141. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2017.07.013

Maheswari M, Josephine MS, Jeyabalaraja V (2022) Customized deep neural network model for autonomous and efficient surveillance of wildlife in national parks. Comput Electr Eng 100:107913. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compeleceng.2022.107913

Maity S, Singh SK, Yadav VK et al (2022) DNA matchmaking in captive facilities: a case study with tigers. Mol Biol Rep 49:4107–4114. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11033-022-07376-3

Majumder A, Basu S, Sankar K et al (2012) Home ranges of the radio-collared Bengal tigers (Panthera tigris tigris L.) in Pench Tiger Reserve, Madhya Pradesh, Central India. Wildl Biol Pract 8:36–49. https://doi.org/10.2461/wbp.2012.8.4

McCauley D, Stout V, Gairhe KP et al (2021) Serologic survey of selected pathogens in free-ranging bengal tigers (Panthera tigris tigris) in Nepal. J Wildl Dis 57:393–398. https://doi.org/10.7589/JWD-D-20-00046

Medhi S, Saikia MK (2019) Spatial relationship between mother-calf of Rhinoceros unicornis in a predator dominated landscape, Kaziranga National Park, Assam, India. Asian J Conserv Biol 8:126–134

Miller CS, Hebblewhite M, Goodrich JM, Miquelle DG (2010) Review of research methodologies for tigers: Telemetry. Integr Zool 5:378–389. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-4877.2010.00216.x

Mishra S, Singh SK, Munjal AK et al (2014) Panel of polymorphic heterologous microsatellite loci to genotype critically endangered Bengal tiger: a pilot study. https://doi.org/10.1186/2193-1801-3-4. SpringerPlus 3:

Mohan G, Yogesh J, Nittu G et al (2021) Factors influencing survival of tiger and leopard in the high-altitude ecosystem of the nilgiris, India. Zool Ecol 31:116–133. https://doi.org/10.35513/21658005.2021.2.6

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J et al (2009) Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med 151:264–269

Mondal P, Nagendra H (2011) Trends of forest dynamics in tiger landscapes across Asia. Environ Manage 48:781–794. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00267-011-9720-6

Mondol S, Bruford MW, Ramakrishnan U (2013) Demographic loss, genetic structure and the conservation implications for Indian tigers. Proc R Soc B Biol Sci 280. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2013.0496

Mukul SA, Alamgir M, Sohel MSI et al (2019) Combined effects of climate change and sea-level rise project dramatic habitat loss of the globally endangered Bengal tiger in the Bangladesh Sundarbans. Sci Total Environ 663:830–840. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.01.383

Naha D, Jhala YV, Qureshi Q et al (2016) Ranging, activity and habitat use by tigers in the mangrove forests of the Sundarban. PLoS ONE 11. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0152119

Naidenko SV, Berezhnoi MA, Kumar V, Umapathy G (2019) Comparison of tigers’ fecal glucocorticoids level in two extreme habitats. PLoS ONE 14. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0214447

Nayak BP, Jena PR, Chaudhury S (2020) Public expenditure effectiveness for biodiversity conservation: understanding the trends for project tiger in India. J Econ 35:229–265. https://doi.org/10.1561/112.00000512

Nittu G, Bhavana PM, Shameer TT et al (2021) Simple nested allele-specific approach with penultimate mismatch for precise species and sex identification of tiger and leopard. Mol Biol Rep 48:1667–1676. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11033-021-06139-w

Nittu G, Shameer TT, Nishanthini NK, Sanil R (2022) The tide of tiger poaching in India is rising! An investigation of the intertwined facts with a focus on conservation. GeoJournal 88:753–766

Palmeirim A, Gibson L (2021) Impacts of hydropower on the habitat of jaguars and tigers. Commun Biol 4. https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-021-02878-5

Pandey P, Hyun JY, Yu M, Lee H (2021) Microsatellite characterization and development of unified STR panel for big cats in captivity: a case study from a Seoul Grand Park Zoo, Republic of Korea. Mol Biol Rep 48:1935–1942. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11033-021-06202-6

Pant G, Maraseni T, Apan A, Allen BL (2020) Trends and current state of research on greater one-horned rhinoceros (Rhinoceros unicornis): a systematic review of the literature over a period of 33 years (1985–2018). Sci Total Environ 710:136349

Parnell T, Narayan EJ, Nicolson V et al (2015) Maximizing the reliability of non-invasive endocrine sampling in the tiger (Panthera tigris): environmental decay and intra-sample variation in faecal glucocorticoid metabolites. Conserv Physiol 3. https://doi.org/10.1093/conphys/cov053

Pasha MKS, Dudley N, Stolton S et al (2018) Setting and implementing standards for management of wild tigers. Land 7. https://doi.org/10.3390/land7030093

Patel NG, Rorres C, Joly DO et al (2015) Quantitative methods of identifying the key nodes in the illegal wildlife trade network. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 112:7948–7953. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1500862112

Paudel PK, Acharya KP, Baral HS et al (2020) Trends, patterns, and networks of illicit wildlife trade in Nepal: a national synthesis. Conserv Sci Pract 2. https://doi.org/10.1111/csp2.247

Penjor U, Astaras C, Cushman SA et al (2022) Contrasting effects of human settlement on the interaction among sympatric apex carnivores. Proc R Soc B Biol Sci 289. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2021.2681

Pereira KS, Gibson L, Biggs D et al (2022) Individual identification of large felids in Field studies: Common methods, challenges, and implications for Conservation Science. Front Ecol Evol 10. https://doi.org/10.3389/fevo.2022.866403

Pullin AS, Stewart GB (2006) Guidelines for systematic review in conservation and environmental management. Conserv Biol 20:1647–1656

Pun P, Lamichhane S, Thanet DR et al (2022) Dietary composition and prey preference of royal bengal tiger (panthera tigris tigris, linnaeus 1758) of parsa national park, Nepal. Eur J Ecol 8:38–48. https://doi.org/10.17161/EUROJECOL.V8I1.15466

Puri M, Marx AJ, Possingham HP et al (2022a) An integrated approach to prioritize restoration for Carnivore conservation in shared landscapes. Biol Conserv 273:109697. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2022.109697

Puri M, Srivathsa A, Karanth KK et al (2022b) Links in a sink: interplay between habitat structure, ecological constraints and interactions with humans can influence connectivity conservation for tigers in forest corridors. Sci Total Environ 809:151106. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.151106

Quintana I, Cifuentes EF, Dunnink JA et al (2022) Severe conservation risks of roads on apex predators. Sci Rep 12. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-05294-9

Rakshya T (2016) Living with wildlife: conflict or co-existence. Acta Ecol Sin 36:509–514. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chnaes.2016.08.004

Ramesh T, Kalle R, Milda D et al (2020) Patterns of livestock predation risk by large carnivores in India’s Eastern and Western Ghats. Glob Ecol Conserv 24:e01366. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gecco.2020.e01366

Rao A, Saksena S (2021) Wildlife tourism and local communities: evidence from India. Ann Tour Res Empir Insights 2:100016. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annale.2021.100016

Rastogi A, Hickey GM, Badola R, Hussain SA (2012) Saving the superstar: a review of the social factors affecting tiger conservation in India. J Environ Manage 113:328–340. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2012.10.003

Rather TA, Kumar S, Khan JA (2020) Multi-scale habitat modelling and predicting change in the distribution of tiger and leopard using random forest algorithm. Sci Rep 10. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-68167-z

Reddy PA, Cushman SA, Srivastava A et al (2017) Tiger abundance and gene flow in Central India are driven by disparate combinations of topography and land cover. Divers Distrib 23:863–874. https://doi.org/10.1111/ddi.12580

Reddy PA, Puyravaud J-P, Cushman SA, Segu H (2019) Spatial variation in the response of tiger gene flow to landscape features and limiting factors. Anim Conserv 22:472–480. https://doi.org/10.1111/acv.12488

Rizzolo JB (2021) Effects of legalization and wildlife farming on conservation. Glob Ecol Conserv 25:e01390. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gecco.2020.e01390

Sadath N, Kleinschmit D, Giessen L (2013) Framing the tiger — a biodiversity concern in national and international media reporting. Conserv Policy Chang Clim 36:37–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.forpol.2013.03.001

Saif S, Russell AM, Nodie SI et al (2016) Local usage of Tiger Parts and its role in Tiger Killing in the Bangladesh Sundarbans. Hum Dimens Wildl 21:95–110. https://doi.org/10.1080/10871209.2015.1107786

Saif S, Tuihedur Rahman HM, Macmillan DC (2018) Who is killing the tiger Panthera tigris and why? ORYX 52:46–54. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0030605316000491

Saikia M, Maiti AP, Devi A (2020) Effect of habitat complexity on rhinoceros and tiger population model with additional food and poaching in Kaziranga National Park, Assam. Math Comput Simul 177:169–191. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matcom.2020.04.007

Sanderson EW, Moy J, Rose C et al (2019) Implications of the shared socioeconomic pathways for tiger (Panthera tigris) conservation. Biol Conserv 231:13–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2018.12.017

Sarkar M, Krishnamurthy R, Johnson J et al (2017) Assessment of fine-scale resource selection and spatially explicit habitat suitability modelling for a re-introduced tiger (Panthera tigris) population in central India. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.3920. PEERJ 5:

Sarkar MS, Amonge DE, Pradhan N et al (2021a) A review of two decades of Conservation efforts on Tigers, co-predators and Prey at the Junction of Three Global Biodiversity Hotspots in the Transboundary Far-Eastern Himalayan Landscape. Animals 11:2365

Sarkar MS, Niyogi R, Masih RL et al (2021b) Long-distance dispersal and home range establishment by a female sub-adult tiger (Panthera tigris) in the Panna landscape, central India. Eur J Wildl Res 67. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10344-021-01494-2

Saxena A, Habib B (2022) Crossing structure use in a tiger landscape, and implications for multi-species mitigation. Transp Res Part Transp Environ 109:103380. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trd.2022.103380

Schoen JM, Neelakantan A, Cushman SA et al (2022) Synthesizing habitat connectivity analyses of a globally important human-dominated tiger-conservation landscape. Conserv Biol 36. https://doi.org/10.1111/cobi.13909

Seidensticker J (2010) Saving wild tigers: a case study in biodiversity loss and challenges to be met for recovery beyond 2010. Integr Zool 5:285–299. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-4877.2010.00214.x

Seidensticker J, McDougal C (1993) Tiger predatory behaviour, ecology and conservation. In: Symposium of the zoological society of London

Seidensticker J, Christie S, Jackson P (1999) Riding the Tiger. Tiger conservation in human-dominated landscapes. Camb Univ Press New YorkUSA 383 383

Shahi K, Khanal G, Jha RR et al (2022) Characterizing damages caused by wildlife: learning from Bardia National Park, Nepal. Hum Dimens Wildl 27:173–182. https://doi.org/10.1080/10871209.2021.1890862

Sharma S, Dutta T, Maldonado JE et al (2013) Spatial genetic analysis reveals high connectivity of tiger (Panthera tigris) populations in the Satpura-Maikal landscape of Central India. Ecol Evol 3:48–60. https://doi.org/10.1002/ece3.432

Sharma P, Chettri N, Uddin K et al (2020) Mapping human–wildlife conflict hotspots in a transboundary landscape, Eastern Himalaya. Glob Ecol Conserv 24:e01284. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gecco.2020.e01284

Shrestha S, Sherpa AP, Lama S et al (2022) Tigers at higher elevations outside their range: what does it mean for conservation? Eco mont 14:43–46. https://doi.org/10.1553/ECO.MONT-14-1S43

Shrivatav AB, Singh KP, Mittal SK, Malik PK (2012) Haematological and biochemical studies in tigers (Panthera tigris tigris). Eur J Wildl Res 58:365–367. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10344-011-0545-7

Sidhu N, Borah J, Shah S et al (2019) Is canine distemper virus (CDV) a lurking threat to large carnivores? A case study from Ranthambhore landscape in Rajasthan, India. J Threat Taxa 11:14220–14223. https://doi.org/10.11609/jot.4908.11.9.14220-14223

Singh R, Qureshi Q, Sankar K et al (2013) Use of camera traps to determine dispersal of tigers in semi-arid landscape, western India. J ARID Environ 98:105–108. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaridenv.2013.08.005

Singh R, Qureshi Q, Sankar K et al (2014) Reproductive characteristics of female Bengal tigers, in Ranthambhore Tiger Reserve, India. Eur J Wildl Res 60:579–587. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10344-014-0822-3

Singh R, Pandey P, Qureshi Q et al (2020) Acquisition of vacated home ranges by tigers. Curr Sci 119:1549–1554. https://doi.org/10.18520/cs/v119/i9/1549-1554

Singh R, Pandey P, Qureshi Q et al (2021) Philopatric and natal dispersal of tigers in a semi-arid habitat, western India. J Arid Environ 184:104320. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaridenv.2020.104320

Srivathsa A, Banerjee A, Banerjee S et al (2022) Chasms in charismatic species research: seventy years of Carnivore science and its implications for conservation and policy in India. Biol Conserv 273:109694. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2022.109694

Stokes EJ (2010) Improving effectiveness of protection efforts in tiger source sites: developing a framework for law enforcement monitoring using MIST. Integr Zool 5:363–377. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-4877.2010.00223.x

Sunquist (1981) The social organization of tigers (Panthera tigris) in Royal Chitawan National park, Nepal

Tempa T, Hebblewhite M, Goldberg JF et al (2019) The spatial distribution and population density of tigers in mountainous terrain of Bhutan. Biol Conserv 238:108192. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2019.07.037

Thapa K, Kelly MJ (2017) Density and carrying capacity in the forgotten tigerland: Tigers in the understudied Nepalese Churia. Integr Zool 12:211–227. https://doi.org/10.1111/1749-4877.12240

Thapa B, Aryal A, Roth M, Morley C (2017a) The contribution of wildlife tourism to tiger conservation (Panthera tigris tigris). Biodiversity 18:168–174. https://doi.org/10.1080/14888386.2017.1410443

Thapa K, Wikramanayake E, Malla S et al (2017b) Tigers in the terai: strong evidence for meta-population dynamics contributing to tiger recovery and conservation in the terai arc landscape. PLoS ONE 12. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0177548

Thapa K, Manandhar S, Bista M et al (2018) Assessment of genetic diversity, population structure, and gene flow of tigers (Panthera tigris tigris) across Nepal’s Terai Arc Landscape. PLoS ONE 13. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0193495

Thapa K, Malla S, Subba SA et al (2021) On the tiger trails: Leopard occupancy decline and leopard interaction with tigers in the forested habitat across the Terai Arc Landscape of Nepal. Glob Ecol Conserv 25:e01412. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gecco.2020.e01412

Thatte P, Chandramouli A, Tyagi A et al (2020) Human footprint differentially impacts genetic connectivity of four wide-ranging mammals in a fragmented landscape. Divers Distrib 26:299–314. https://doi.org/10.1111/ddi.13022

Thinley P, Rajaratnam R, Lassoie JP et al (2018) The ecological benefit of tigers (Panthera tigris) to farmers in reducing crop and livestock losses in the eastern Himalayas: implications for conservation of large apex predators. Biol Conserv 219:119–125. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2018.01.015

Thinley P, Rajaratnam R, Morreale SJ, Lassoie JP (2021) Assessing the adequacy of a protected area network in conserving a wide-ranging apex predator: the case for tiger (Panthera tigris) conservation in Bhutan. Conserv Sci Pract 3. https://doi.org/10.1111/csp2.318

Thuppil V, Coss RG (2013) Wild Asian elephants distinguish aggressive tiger and leopard growls according to perceived danger. Biol Lett 9. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsbl.2013.0518

Ullas Karanth K, Srivathsa A, Vasudev D et al (2017) Spatio-temporal interactions facilitate large Carnivore sympatry across a resource gradient. Proc R Soc B Biol Sci 284. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2016.1860

VDTC (2022) The Vladivostok Declaration on Tiger Conservation, 2nd International Tiger Forum,Vladivostok, Russian Federation, September 5,2022

Vernes K, Rajaratnam R, Dorji S (2022) Patterns of species co-occurrence in a diverse Eastern Himalayan montane Carnivore community. Mammal Res 67:139–149. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13364-021-00605-3

Warrier R, Noon BR, Bailey L (2020) Agricultural lands offer seasonal habitats to tigers in a human-dominated and fragmented landscape in India. https://doi.org/10.1002/ecs2.3080. Ecosphere 11:

Whitfort A (2019) China and CITES: strange bedfellows or willing partners? J Int Wildl Law Policy 22:342–372. https://doi.org/10.1080/13880292.2019.1708558

Wikramanayake E, Dinerstein E, Seidensticker J et al (2011) A landscape-based conservation strategy to double the wild tiger population. Conserv Lett 4:219–227. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1755-263X.2010.00162.x

Williams VL, Loveridge AJ, Newton DJ, Macdonald DW (2015) Skullduggery: Lions align and their mandibles rock! https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0135144. PLoS ONE 10:

Wilting A, Courtiol A, Christiansen P et al (2015) Planning tiger recovery: understanding intraspecific variation for effective conservation. Sci Adv. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.1400175. 1:

Yadav PK, Brownlee MT, Kapoor M (2022) A systematic scoping review of tiger conservation in the Terai Arc Landscape and Himalayas. Oryx 1–9

Yamaguchi N, Driscoll C, Werdelin L et al (2013) Locating specimens of extinct tiger (Panthera tigris) subspecies: Javan tiger (P. t. Sondaica), balinese tiger (P. t. balica), and Caspian tiger (P. t. virgata), including previously unpublished specimens. MAMMAL STUDY 38:187–198. https://doi.org/10.3106/041.038.0307

Yumnam B, Jhala YV, Qureshi Q et al (2014) Prioritizing tiger conservation through landscape genetics and habitat linkages. PLoS ONE 9. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0111207

Zabel A, Engel S (2010) Performance payments: a new strategy to conserve large carnivores in the tropics? Spec Sect Ecol Distrib Confl 70:405–412. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2010.09.012

Acknowledgements

The first author would like to thank Ministry of Forest and Environment, Government of Nepal for granting study leave and University of Southern Queensland for providing International PhD Research Fee Scholarship support to conduct this research. We also acknowledge Kishor Aryal, Utsab Bhattarai and Rajan Budhathoki for their support.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Amir Maharjan: Conceptualization, Methodology, Data curation, Software, Analysis, Writing─ original draft. Tek Maraseni: Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing─ review and editing. Benjamin L Allen: Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing─ review and editing. Armando Apan: Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing─ review and editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Communicated by David Hawksworth.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions