Abstract

Hunting of wild animals for meat and habitat loss are the main drivers of wildlife population decline around the world, and in tropical regions in particular. While Madagascar is a hotspot for biodiversity, hunting is widespread, mostly in form of subsistence hunting, while hunting for the pet trade is less often reported.

We studied hunting of the Critically Endangered black-and-white ruffed lemur (Varecia variegata) in northeastern Madagascar. Using lemur surveys (102.7 km survey effort) and 54 semi-structured and seven key informant interviews, we assessed the local knowledge, hunting pressure, and the perceived and actual abundances of V. variegata in two hunting and two non-hunting villages.

V. variegata was well known (> 83%) by the respondents but abundance estimates differed significantly between hunting and non-hunting villages, with 26% and 77% of respondents, respectively, estimating a high abundance of ruffed lemurs in the adjacent forests of the villages. Actual observations of V. variegata also differed strongly, in accordance to perceived abundances. Hunting was either done by trapping animals or by pursuit hunts. In both hunting villages, adult lemurs were used for direct meat consumption and juveniles for rearing for the later trade. Hand-raised V. variegata were reported to be sold for 38–71 USD on regional markets or ‘delivered’ directly to buyers.

While wildlife hunting has been widely reported from all over Madagascar, commercial hunting, hand-rearing and trading adds a new dimension of threat towards these Critically Endangered lemurs. As such, the extent of the trade is a priority for future studies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Global biodiversity is in decline (e.g., IPBES 2019). Land partitioning for agricultural production is having a major effect on the availability of land suitable for wildlife, leading to habitat loss and fragmentation (e.g., IBPES 2019; Newbold et al. 2015). Wildlife is often simultaneously threatened by hunting (Gallego-Zamorano et al. 2020; Milner-Gulland et al. 2003; Ripple et al. 2016). Although not problematic in all cases, over-exploitation of populations together with land use changes have resulted in massive declines in a multitude of wildlife species (Benítez-López et al. 2017; Gallego-Zamorano et al. 2020).

Hunting of wild animals is generally defined as the extraction of any kind of undomesticated animal for food (i.e., wild meat or bushmeat hunting), medicinal reasons, and/or as trophies or pets (Estrada and Garber 2022; Nasi et al. 2008). Consequently, hunting in tropical regions often provides an important livelihood strategy for both income generation and food acquisition (Cawthorn and Hoffman 2015; Lee et al. 2020). Rural areas in close proximity to forests are usually the hunting grounds where wild meat is either consumed locally or transported to urban markets (Jones et al. 2019; Nasi et al. 2008). Wild meat demand can be linked to economic factors with two contrasting positions prevailing: households that are more isolated and less food secure appear to have higher levels of wildlife consumption, while on the other hand, demand may also increase with increasing proximity to urban areas and infrastructure (Brashares et al. 2011; McNamara et al. 2019; Ziegler et al. 2016). In the former case, wild meats are often considered a fallback resource, used in times of increased food insecurity coupled with low levels of livelihood diversification in general (Borgerson et al. 2016; Brashares et al. 2011; Golden et al. 2011). It also provides essential proteins to rural populations in some regions (Golden et al. 2011; van Vliet and Mbazza 2011). In the latter case, wild meat is often consumed by an increasingly wealthy population for which consumption of certain species represents a status symbol (i.e., luxury meat) or the continuation of traditional practices (e.g., Cawthorn and Hoffman 2015; Lee et al. 2020; McNamara et al. 2019).

Wildlife is increasingly hunted in many important hotspots of tropical biodiversity across West Africa, Southeast Asia, and Madagascar. While hunting in West Africa and Southeast Asia is variously done for one’s own consumption, commercial use, medical reasons, the pet trade, and as trophies (e.g., Estrada et al. 2018; Fominka et al. 2021; Lee et al. 2020), the situation in Madagascar is somewhat different: Multiple reports suggest wildlife is hunted and directly consumed locally by a particularly poor and food insecure population (e.g., Borgerson et al. 2016; Gardner and Davies 2013; Golden 2009; Jenkins and Racey 2009; Merson et al. 2019; Randriamamonjy et al. 2015; Thompson et al. 2023). Poverty is widespread and comprehensive estimates state that almost eight out of ten Malagasy persons live below the poverty line of 1.9 USD per day (UNDP 2022). While hunting is practiced nation-wide (Borgerson et al. 2021), its contribution to income generating activities, in contrast to direct subsistence, has rarely been assessed (Reuter et al. 2016). A survey on the transport of wild meat as an indicator for commercial interests has revealed that wild meat trade is prevalent in Madagascar, and is assumed to be more widespread than previously thought (Reuter et al. 2016). Others have hypothesized the rise of commercial wild meat or even luxury wild meat hunting as a consequence of political instability in the country (Barrett and Ratsimbazafy 2009). In any circumstance, hunting is unanimously considered as a potential final push of already endangered species towards their extinction (Estrada et al. 2018; Ralimanana et al. 2022; Ripple et al. 2016).

In this study, we investigate patterns of illegal hunting concerning one of the charismatic primate species of the island, the Critically Endangered black-and-white ruffed lemur (Varecia variegata). Focusing on four different formally unprotected forests of northeastern Madagascar, we (1) compare the effects of hunting presence and absence on the abundance of V. variegata and local perceptions on population change and (2) explore the methods and motivations for lemur hunting using key informant interviews.

Methods

Study region

Northeastern Madagascar forms a part of the tropical rainforest biome of Madagascar (Beck et al. 2018). Today, it is characterized by highly degraded and long term deforested landscapes in proximity to major roads and larger cities, while still forested regions with small villages can only be found further away from the coast in the remote countryside (Schüßler et al. 2020). These areas are generally characterized by limited access to infrastructure, high dependence on natural resources, the prevailing existence of customary rules and the virtual absence of state control and law enforcement (Randimbiharinirina et al. 2021; Schüßler et al. 2020; pers. obs.). Remaining forests and their non-human inhabitants are mainly perceived as resource reservoirs (Golden 2009; Ratsimbazafy et al. 2012), for which unsustainable use is regularly reported (Brook et al. 2019; Schüßler et al. 2018, 2020).

We surveyed four different villages and adjacent forests along this forest frontier within the southern Analanjirofo region of Madagascar. Two of these study sites were characterized by illegal hunting of Varecia variegata (forests A & B), while the other two village communities did not participate in hunting this species (forests C & D). All surveyed forests were otherwise characterized by the same set of factors, e.g., short distance to the nearest village, connectivity to a larger forest and survey effort. The closest villages to these forests were chosen for conducting interviews (see below). Exact forest or village locations are not further detailed to ensure anonymity of our key informants. The distances among the villages were at least two regular day hikes (i.e., local walking speed estimation) to reduce spatial autocorrelation.

Lemur surveys

We placed 4–5 transect lines of 0.5-2.0 km length at each study site, starting at the forest edge extending towards the forest core areas. These transects were three to four times surveyed during day (9am-3pm) and night (6pm-12pm) and for 6–8 consecutive days/nights (e.g., Schüßler et al. 2018) equaling a survey effort of 23.67, 35.07, 22.24 and 21.70 km in forests A-D, respectively. All lemur encounters were recorded and georeferenced. Forest cover and distance to the nearest village were derived from Schüßler et al. (2020) and were comparable across the sites.

Interviews

We conducted 54 semi-structured household interviews in the four selected villages and a further seven key informant interviews in villages with reported hunting of V. variegata in April and May 2022. The number of households surveyed corresponded to the total village size and comprised roughly half of the available households per village (sample sizes and percentage of surveyed households: A: n = 11 (55%), B: n = 16 (53%), C: n = 14 (40%), D: n = 13 (43%). A native speaker conducted the interviews in Malagasy, always adapting the questions to the local dialect and translating all answers into English afterwards. Before any interview was conducted, the village leaders were approached to explain the objectives of the research (i.e., to learn about local knowledge and interactions with lemurs, local land use strategies, and that all data is anonymized and not retraceable to the communities) and to ask for permission. We explained to each study respondent (adults of > 18 years) that their participation was voluntary, they could deny answers to any question and end the interview at any time, and the objectives of the study beforehand. All respondents gave their informed consent to participate. Our methods adhered to the standards defined by the World Medical Association (2013) and Wilmé et al. (2016) for ethical research in Madagascar and were further approved by the ethics committee at the University of Hildesheim (on 28.06.2019). This study was conducted under research permit No. 030/22/MEDD/SG/DGGE/DAPRNE/SCBE.Re issued by the Ministry for the Environment and Sustainable Development of Madagascar. All data in this manuscript is anonymized. We included the number of the key informant as KI# for consistency with our anonymized data and added necessary information for understanding quotations in square brackets. Data was analyzed in R v4.2.2 and RStudio v12.0.353 (R Core Team 2022; Posit Team 2022).

The semi-structured interviews (n = 27 in hunting villages, n = 27 in non-hunting villages) included questions on demographic variables (i.e., age, gender, school education, origin), resource extraction from forests (i.e., wood, non-timber forest products (NTFP)), land use systems (i.e., shifting cultivation, rice paddy cultivation), participation in clove, vanilla or coffee agroforestry, and specifics about V. variegata. We asked each participant (1) whether they recognized the species and could provide the local name when presented with a photograph of V. variegata, (2) how they would categorize the abundance of this species (many, few, not here anymore), and (3) whether it is allowed to be eaten or considered taboo by the members of the own household. A further open question gave space for comments on this species in general, i.e., personal experiences, observations or things the respondents heard about it from others.

We interviewed seven key informants in the two hunting villages (four in village A, three in village B) who identified themselves as associated with the hunting business (i.e., hunter (KI1, 2, 3), observer (KI5 and 7), pet keeper (KI4), or intermediary (KI4 and 6)). We used open questions and an interview guideline including specific questions about the in-depth knowledge and experiences with V. variegata, hunting practices, use of lemur meat and live animals and selling opportunities.

Results

Demography of respondents to household interviews

About two thirds of respondents were native to the respective village and 77.8% identified themselves as male (22.2% as female; Table 1). About half of respondents (51.9%) were young adults (18–30 years old) and half (48.1%) were adults older than 30, with few (5.6%) elders older than 55 years (Table 1). Less than a quarter (22.2%) of respondents had attended secondary or high school and the highest share of respondents has not attended any school (44.4%; Table 1). Almost all respondents practiced shifting cultivation for rice farming and agroforestry of cash crops such as vanilla and/or cloves (Table 1). Most (85.2%) relied on forest products for subsistence (e.g., construction wood, fiber).

Presence of Varecia variegata – observed and perceived

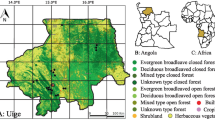

V. variegata was found in different abundances in the four surveyed forests. Whereas only single sightings (i.e., one group, sighted one time) were noted in forests A and B (hunting villages), eleven and ten encounters of groups were noted in forests C and D (non-hunting villages), respectively (Fig. 1). Groups consisted in all cases of at least three and up to seven individuals. We furthermore documented 14 trapping locations in forest A (Fig. 1), which consisted each of 2–4 snare traps as shown in Fig. 2 and described below. Traps were absent from the other forests.

Out of 54 respondents to our semi-structured interviews, 83.3% could recall V. variegata from a photograph. With 85.2% and 81.5% in non-hunting and hunting villages, respectively, this proportion did not differ between villages (χ² = 0.000, df = 1, P = 1.000). When asked about the abundance of V. variegata, significantly fewer (26.1%) respondents from hunting villages reported a high abundance of V. variegata in the forests surrounding the village than in non-hunting villages (77.3%) (χ² = 9.831, df = 1, P = 0.002). Six respondents (11.1% of all respondents) from hunting villages further reported about the population change, saying, ‘before there was many here, but now you have to go far to find them’ (meaning of the Malagasy word “sasatra”). Most (75.9%) respondents told that there are no taboos in their household about eating or hunting V. variegata (neither formal nor informal; insignificant across villages: χ² = 2.843, df = 2, P = 0.241), 3.7% reported that it is taboo for them, while 20.4% declined answering this question.

Comparison of four forests for sightings of Varecia variegata groups with distance to the nearest village. A-B: forest with Varecia variegata hunting (with trapping locations each consisting of multiple snare traps associated in trapping lines in A); C-D: forest without Varecia variegata hunting. Forest cover and village locations according to Schüßler et al. (2020)

Hunting motivation

All key informants from the hunting villages reported about hunting of Varecia variegata, while three also talked about hunting of Indri indri, one about Eulemur fulvus, and one about hunting of Propithecus diadema. Three of our seven key informants identified themselves as lemur hunters (including V. variegata), two as observers of hunting practices in the village, and two as lemur pet keepers and middlemen in the lemur pet trade.

We documented two different methods of hunting of V. variegata (see below). In both cases, hunting can be differentiated into either fatal capture of adult individuals for own consumption or live capture of juvenile individuals, primarily for later sale. ‘In the forest, animals are very aggressive. You cannot get them’ (KI2). ‘They are killed directly and eaten in the village’ (KI1,2). Aggressiveness of adult individuals is also reflected in another instance, when KI3 told: ’I was once attacked by a simpona [P. diadema], it bit me in the hand.’ Juvenile individuals are considered less aggressive: ‘At first [after acquisition], lemurs are scared but after, they are calm’ (KI4). ‘When you raise a lemur by hand, it is calm after [a while]’ (KI2). One middleman (KI4) put it as follows: ‘we take lemurs from the forest and then pet them.’ ‘Sometimes you can buy baby lemurs and pet them after. I already bought varikandana [V. variegata] for 5,000 and once for 20,000 Ariary [1.2USD and 4.76USD, respectively] and babakoto [Indri indri] for 35,000 Ariary [8.33USD]. I pet them afterwards. The place to buy lemurs is 12 h walking from here. There [place not named], the forest is very dense [= low degradation]’. Both middlemen in our sample already sold former pet lemurs on a regional market or directly ‘delivered’ (KI4) individuals to the bigger cities of the region, i.e., Mananara Avaratra, Andilamena and Ampasimbe. ‘Lemurs are kept as pets, until they are sold alive to another place’ (KI2). Revenues were reported differently from four key informants. They varied from 160,000 to 200,000 Ariary (38.10-47.60USD; KI1,5,6) to 300,000 Ariary (71.40USD; KI4) from the latest sale of V. variegata, and 40,000 and 140,000 Ariary (9.50 and 33.30USD; KI1,6) for the sale of I. indri.

Hunting practice

Each hunting village practiced only one type of hunting. The first method of hunting involves passive trapping in the forest with snare traps, “laly” (KI1). These traps are constructed almost entirely from natural materials surrounding the trapping location. A single snare trap consists of two or more vertical poles made out of young trees installed on a scaffold about 2-3 m above the ground. The middle of the vertical poles supports a rope snare, which is fixed to another pole bent and set under pressure. Bait, like banana or other fruits, is provided right below the rope snare. If a lemur moves along the vertical poles and enters the snare, a thin rope is hit by the animal and releases the tension of the pole under pressure, tightening the snare around the animal, preferably the neck, to kill it. The dead animal then hangs from the pole fixed to the snare to be gathered afterwards. If the killed animal was a female carrying a juvenile on its back, the juvenile usually still clings to the back and can be collected alive (KI1). Snare traps are ’checked on a regular basis’ (KI1). We observed several pathways in the forest that were only used to check traps and ended at these places. Around each trap, all woody vegetation was cleared beforehand. This resulted in a 10 m wide clearing with a length of 80 m to sometimes 150 m. On these long, strip-shaped clearings (“trapping lines”), up to four snare traps were documented. The traps therefore represent the only arboreal crossing of the artificial clearing. All trapping locations documented in forest A (Fig. 1) were at the ridges of hills or close to them. These kind of traps were found in otherwise relatively intact forest.

The described method indiscriminately targets quadrupedal lemur species including Eulemur fulvus and E. rubriventer, too. The former species is hunted for local consumption while the latter was ‘not seen any more for a long time.’ ‘Varikandana [V. variegata] and varikosa [E. fulvus] have the best taste. But all lemurs taste good‘ (KI1). One hunter and one observer from the forests A and B further discussed the population change: ‘To see varikandana [V. variegata], it is very difficult today, but before it was easy’ (KI3) or ‘Varikandana is not here anymore, too many people ate it’ (KI7).

The second method does not involve snare traps, but actively chasing individual lemurs through pursuit hunting. As put by KI2: ‘We [group of hunters] search for [a group of] varikandana [V. variegata] in the forest. If varikandana are seen, females with juveniles [on the back] are identified. They are followed and shot with slingshots until they lose [abandon] the juvenile. The juvenile is then taken and raised by hand.’ From our observation, hunters also usually carry machetes, to cut vegetation in the escape routes of lemurs and are very skilled at climbing up trees to block ways for escaping individuals.

Snare trap used for quadrupedal lemurs like Varecia variegata, Eulemur fulvus, and E. rubriventer. This trap is part of a trapping line, for which vegetation in completely cut down to provide the trapping scaffolds as single passages to the clearing for quadrupedal, arboreal lemurs. Two scaffolds are visible here. The first goes down with a larger pole from the right upper corner towards a net-like structure, which is built with a rope snare in its middle, which is then fixed to a thin wooden pole set under pressure. No bait is visible in this trap. The scaffold then continues upwards to the left upper corner to reach its connection with the higher trees at the forest edge. A second trap is visible in the background. Photo taken by Maria Jäger in 2022

Discussion

Population effects

Most wildlife populations in tropical countries are declining due to land use changes and simultaneously acting pressures like hunting practiced by local communities (Gallego-Zamorano et al. 2020; Milner-Gulland et al. 2003; Ripple et al. 2016). This combination usually acts as the final push towards local extirpations (Estrada et al. 2018; Ripple et al. 2016) and the phenomenon of still “intact but empty forests” (Benítez-López et al. 2019). Forests outside protected areas often host less mammal species and lower abundances than those within protected areas (Benítez-López et al. 2017). Although the data presented here stem from a case study in four villages of northeastern Madagascar, the outlined mechanisms are likely to reflect larger-scale developments of the whole region of central- and northeastern Madagascar (Andrianaivoarivelo et al. 2021; Golden 2009; DS pers. obs.), an area equaling the size of Togo, Croatia, or Costa Rica.

Varecia variegata was well-known among the respondents with more than 80% of them being able to recall this species from photographs. This percentage is markedly higher than for other species like the verbally often cited Aye-aye (Daubentonia madagascariensis) with a recall rate of 29% (Randimbiharinirina et al. 2021) or the elusive hairy-eared dwarf lemur (Allocebus trichotis) with only 2% recalls from photographs (Schüßler et al. 2023). Recall rates did not differ between hunting and non-hunting villages, but local perceptions on the population of V. variegata did: Most respondents in hunting villages attested a low abundance of this species surrounding their village while in non-hunting villages, people perceived that this species occurs in high abundances in the adjacent forests. These assessments were congruent with our own surveys. Six respondents from hunting villages elaborated on the population development, reporting that they experienced a decline in abundances and that today, long distances have to be walked from the villages into the forest to still find V. variegata. This perception appears to be rather common in communities living along the forest frontiers when over-exploitation of resources (like wild meat) is taking place (partly echoed in Benítez-López et al. 2019; Feurer et al. 2019; Muhamad et al. 2014). The study region has undergone substantial settlement expansion and concomitant migration towards the forest edges driven by the quest for arable lands, at least since 1990 (Jones et al. 2018; Schüßler et al. 2020). As dependence on natural resources in these regions is high and comparable to other studies (Randimbiharinirina et al. 2021; Ratsimbazafy et al. 2012; Table 1), and valuable cash crops like vanilla and cloves require at least 5–10 years until their first harvest (pers. Comm. With local land users), the overuse of directly available resources is very likely to happen.

Varecia variegata, together with Eulemur spp., Hapalemur spp. and Indri indri have been reported to be consumed by more than three quarters of all villages studied (with varying proportions of households) in the Makira region north of our study villages (Golden 2009; Spira et al. 2021). Moreover, local extirpations of V. variegata and I. indri have already been evidenced from parts of the region (Schüßler et al. 2018). In central-eastern Madagascar, about 30% of respondents reported to have recently eaten V. variegata meat in 2008/09 (Jenkins et al. 2011), and in southeastern Madagascar, six out of eight surveyed forests showed high levels of hunting (Lehman et al. 2006). A nation-wide meta-analysis attested that V. variegata is among the most eaten species in Madagascar (Borgerson et al. 2021). Although hunting occurs across its entire range, northeastern Madagascar may represent a hunting hotspot concerning this species (Borgerson et al. 2021). Hunting together with habitat degradation also has the highest impact on the sister species V. rubra, resulting in drops of population density in areas close to villages (Borgerson 2015) comparable to what we documented in this study. Although protected by international and national legislation, the Critically Endangered V. variegata was considered as neither formally nor informally protected by more than three quarters of our respondents and hunting was therefore not regarded as an illegal activity by them. This discordance between national legislation and local conviction is rather typical in these rural areas with virtually no presence of state authorities and law enforcement at all (pers. obs.). That this species is also not integrated in the local taboo system is in accordance to previous findings (Golden and Comaroff 2015).

Hunting motivation

Wild meat is often considered a fallback resource in communities living close to the forest frontier (Borgerson et al. 2016, 2017; Kümpel et al. 2010) with peaks in hunting activity in times of limited resource availability (Jenkins and Racey 2009; Golden et al. 2019). Direct consumption is sometimes coupled with income generation through trading to regional or urban markets (e.g., Jones et al. 2019; Nielsen et al. 2017). In Madagascar, wild meat hunting has often been related to direct consumption with drivers like poverty, child malnutrition, and poor health conditions prevailing (Borgerson et al. 2016, 2017; Merson et al. 2019). Trading of wild meat as an income generation strategy has rarely been reported but may be more prevalent than previously thought (Reuter et al. 2016). We documented the same duality in our case study, with a certain amount of animals being consumed locally, mostly those fatally captured. Localized consumption of wild meat is common in Madagascar (e.g., Borgerson 2015; Golden 2009). However, here we show that some hunting is also directly targeted toward the capture of live individuals for the single purpose of pet keeping and later sale. Juveniles were the major target of this capture, as adults were perceived to be too aggressive to be kept as pets. Hand-reared lemurs, V. variegata and I. indri in our case, were fed with rice, cassava, and fruits until later sale. If an individual died before being sold, it was consumed by the pet keepers (usually folivorous I. indri die on such a diet and are then eaten). Trading was directed towards the major cities of the region, either via middlemen or directly by family members of the pet keeper who delivered the animal to its buyer. This indicates some kind of work sharing between hunters (see below), pet keepers, and sellers. How developed this system is, remains elusive until further investigation. In other parts of Madagascar, lemur pet trade has been linked to touristic activities to display lemurs as attractions in hotels (Reuter and Schaefer 2017), but other accounts indicated that a high share of pet animals are not publically visible (Reuter et al. 2016). Unfortunately, our respondents could not estimate the purpose of the respective buyers.

In Madagascar, it is approximated that 78.8% of the population live below the income poverty line of 1.90 USD per day (UNDP 2022). Sales prices of 38–71 USD achieved for one living individual of V. variegata could certainly make hunting a lucrative business in our study communities. Livelihood strategies are rather homogeneous in northeastern Madagascar, with almost all people farming their own rice (major staple crop), growing agroforestry products like vanilla and cloves, and extracting construction materials from forests, while only very few are generating income from other sources (Andriamparany et al. 2021; Randimbiharinirina et al. 2021; Ratsimbazafy et al. 2012; Table 1). Diversification of livelihood strategies to counteract inherent food insecurity (Andriamparany et al. 2021; Borgerson et al. 2017; Harvey et al. 2014) may be therefore a main driver for this localized pet keeping and trading business. However, as populations of the Critically Endangered Varecia variegata (and others) are already almost depleted, and given that local hunting communities themselves recognize this depletion, too, the need for alternative sources of sufficient income and strategies to counteract food insecurity is of outmost importance to both reduce the pressure on wildlife populations and improve the living condition in northeastern Madagascar.

Hunting practices may give a further hint into the hunter’s motivations. Pursuit hunting on the one hand may be associated with the ‘thrill of the chase’ (e.g., El Bizri et al. 2015), which attracts mostly young men in our study region, targeting any kind of wildlife (pers. obs.). This is paralleled by opportunistic shooting birds with slingshots and hand-catching frogs, chameleons, or mouse lemurs (pers. obs.). On the other hand, the construction of passive snare –traps in trapping lines and the preparation of clearings must include a much higher amount of workforce. Andrianaivoarivelo et al. (2021) estimated, that one trapping line may require cutting 16,000–24,000 smaller and larger trees, while maintaining the traps and checking for trapping success results in a long-term investment of time and work, which is unlikely to be explained by something like the ‘thrill of the chase’ or the immanent need for wild meat (adult weight of V. variegata is about 3–4 kg, Mittermeier et al. 2010). The financial benefit instead could explain this discrepancy between workload and meat offtake, under circumstances when other sources of income generation are limited or inaccessible. Although hunting in Madagascar has usually been associated with bridging the lean season of rice harvest, when little other food sources are available (e.g., Golden et al. 2019), earning between 38 and 71 USD with one animal could be indeed a strong motivation for year-round hunting (Jones et al. 2019; Nielsen and Meilby 2014). Alternatively, a traditional component in hunting wildlife may be used as an explanation, too. However, the low numbers of lemurs observed in the hunting forests may not justify the high workload of preparing and maintaining trapping lines, while the absence of hunting in other forests may also question this view.

To conclude, we attribute the observed hunting of lemurs to be mostly commercially driven, based on high workload, low meat offtake and high potential income from selling pet animals. However, it remains open, why some communities are not participating in this hunting business, although target species are still abundant. Whether this can be explained by better market access, diversified livelihood strategies, including cash crop farming, or local customs is up for further research.

Hunting practice and the pet trade

Lemur hunting in Madagascar is mostly reported as either passive trapping of individuals with some kind of simple snare traps (Borgerson 2015; Golden 2009; Sato et al. 2021) or shooting lemurs with rifles, slingshots, or blowpipes (Davies & Gardner 2014; Sato et al. 2021; Vasey 1996). Trapping with snares was also confirmed in one of the hunting villages. Here, trapping lines (locally called laly dilana or laly lava) as already documented by Borgerson (2015) and Golden (2009) were found.

Apart from widespread lemur trapping around Madagascar, our study is the first to report pursuit hunting of lemurs in one village. This may represent an adaptation to the aim of specifically targeting juvenile individuals for hand-rearing and later sale. Passive snare trapping is unspecific concerning the animal to be caught and may therefore have a lower probability to capture females that carry juveniles. Pursuit hunts are therefore more target-oriented as infant-carrying adults are either chased until they lose/abandon their offspring or are directly killed (if possible with slingshots) for local consumption – rifles are not used. V. variegata is a group living species with group sizes of 2–15 individuals (Balko and Underwood 2005). If several individuals of a group are killed (especially breeding females with juveniles, given the species irregular birthing cycles (Baden 2019), this is likely to have massive effects on its demographic structure, sex ratio, and reproductive rates. In particular, the extraction of breeding females and juveniles could lead to a rapid depletion of family groups and/or their entire reproductive output.

Implications for conservation

Species conservation in tropical environments has to counteract two main threats: habitat loss and hunting (Gallego-Zamorano et al. 2020; Ripple et al. 2016). Our study species, Varecia variegata, is already considered as Critically Endangered by the IUCN with estimates of habitat loss due to ongoing deforestation together with climatic changes predicting a bleak future (Morelli et al. 2019). Widespread reports of wild meat hunting together with presumably highly unsustainable hunting practices like the documented pursuit hunts further question the future of this species outside the protected area network (but also inside as evidenced from hunting in the Corridor Ankeniheny-Zahamena, Andrianaivoarivelo et al. 2021). However, it is worth mentioning that some communities do not participate in hunting. Whether this is due to better market accessibility and more diversified livelihood strategies concerning cash crops must be investigated in future research. Conservation of V. variegata and other lemurs facing similar threats (e.g., Critically Endangered I. indri) would involve the expansion of protected areas, improved information campaigns about the protection status of lemurs and law enforcement activities, but such efforts may be more effective if non-hunting communities could be identified and promoted as positive examples for the coexistence with lemurs without hunting. Any kind of interventions must involve support for livelihood diversification (i.e., increasing food security) and improvements in the access to markets (e.g., for participating in the cash crop business or other non-land based economic opportunities) to make lemur hunting for subsistence or trading less attractive. However, the extent of this kind of commercial lemur hunting remains elusive today and requires further investigation.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study cannot be made publicly available, as they may help to identify study communities practicing illegal activities.

References

Andriamparany JN, Hänke H, Schlecht E (2021) Food security and food quality among vanilla farmers in Madagascar: the role of contract farming and livestock keeping. Food Secur 13:981–1012. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12571-021-01153-z

Andrianaivoarivelo RA, Grifiths O, Rafeliarisoa TH, Andrianavonjihasina NZM, Andriantsalama ZT, Randriamiadanjato M, Ratsimbason M (2021) Intensive hunting of Varecia variegata in Andriantantely, section of the new Protected Area Corridor Ankeniheny Zahamena. Lemur News 23:18

Baden AL (2019) A description of nesting behaviors, including factors impacting nest site selection, in black-and‐white ruffed Lemurs (Varecia variegata). Ecol Evol 9:1010–1028

Balko EA, Underwood HB (2005) Effects of forest structure and composition on food availability for Varecia variegata at Ranomafana National Park, Madagascar. Am J Primatol 66:45–70. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajp.20127

Barrett MA, Ratsimbazafy J (2009) Luxury bushmeat trade threatens lemur conservation. Nature 461:470–470

Beck HE, Zimmermann NE, McVicar TR, Vergopolan N, Berg A, Wood EF (2018) Present and future Köppen-Geiger climate classification maps at 1-km resolution. Sci Data 5:180214. https://doi.org/10.1038/sdata.2018.214

Benítez-López A, Alkemade R, Schipper AM, Ingram DJ, Verweij PA, Eikelboom JAJ, Huijbregts MAJ (2017) The impact of hunting on tropical mammal and bird populations. Science 356:180–183. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aaj1891

Benítez-López A, Santini L, Schipper AM, Busana M, Huijbregts MAJ (2019) Intact but empty forests? Patterns of hunting-induced mammal defaunation in the tropics. PLoS Biol 17:e3000247. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.3000247

Borgerson C (2015) The effects of illegal hunting and habitat on two sympatric endangered primates. Int J Primatol 36:74–93. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10764-015-9812-x

Borgerson C, McKean MA, Sutherland MR, Godfrey LR (2016) Who hunts Lemurs and why they hunt them. Biol Conserv 197:124–130

Borgerson C, Rajaona D, Razafindrapaoly B, Rasolofoniaina BJR, Kremen C, Golden CD (2017) Links between food insecurity and the unsustainable hunting of wildlife in a UNESCO world heritage site in Madagascar. The Lancet 389:S3. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(17)31115-7

Borgerson C, Johnson SE, Hall E, Brown KA, Narváez-Torres PR, Rasolofoniaina BJR, Razafindrapaoly BN, Merson SD, Thompson KET, Holmes SM, Louis EE, Golden CD (2021) A national-level assessment of lemur hunting pressure in Madagascar. Int J Primatol 43:92–13. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10764-021-00215-5

Brashares JS, Golden CD, Weinbaum KZ, Barrett CB, Okello GV (2011) Economic and geographic drivers of wildlife consumption in rural Africa. Proc Natl Acad Sci 108:13931–13936

Brook CE, Herrera JP, Borgerson C, Fuller E, Andriamahazoarivosoa P, Rasolofoniaina BR, Randrianasolo JRR, Rakotondrafarasata ZE, Randriamady HJ, Dobson AP, Golden CD (2019) Population viability and harvest sustainability for Madagascar Lemurs. Conserv Biol 33:99–111. https://doi.org/10.1111/cobi.13151

Cawthorn DM, Hoffman LC (2015) The bushmeat and food security nexus: a global account of the contributions, conundrums and ethical collisions. Food Res Int 76:906–925. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodres.2015.03.025

El Bizri HR, Morcatty TQ, Lima JJS, Valsecchi J (2015) The thrill of the chase: uncovering illegal sport hunting in Brazil through YouTube TM posts. Ecol Soc 20. https://doi.org/10.5751/es-07882-200330

Estrada A, Garber PA (2022) Principal Drivers and Conservation Solutions to the impending primate extinction Crisis: introduction to the Special Issue. Int J Primatol 43:1–14. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10764-022-00283-1

Estrada A, Garber PA, Mittermeier RA, Wich S, Gouveia S, Dobrovolski R, Nekaris K, Nijman V, Rylands AB, Maisels F, Williamson EA, Bicca-Marques J, Fuentes A, Jerusalinsky L, Johnson S, de Melo FR, Oliveira L, Schwitzer C, Roos C, Cheyne SM, Kieruli MCM, Raharivololona B, Talebi M, Ratsimbazafy J, Supriatna J, Boonratana R, Wedana M, Setiawan A (2018) Primates in peril: the significance of Brazil, Madagascar, Indonesia and the Democratic Republic of the Congo for global primate conservation. PeerJ 6:e4869. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.4869

Feurer M, Heinimann A, Schneider F, Jurt C, Myint W, Zaehringer JG (2019) Local perspectives on ecosystem service trade-os in a forest frontier landscape in Myanmar. Land 8:45. https://doi.org/10.3390/land8030045

Fominka NT, Oliveira HFM, Taboue GCT, Luma FE, Robinson CA, Fokam EB (2021) Conserving the forgotten: new insights from a Central African biodiversity hotspot on the anthropogenic perception of nocturnal primates (Mammalia: Strepsirrhini). Primates 62:537–546. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10329-021-00898-7

Gallego-Zamorano J, Benítez-López A, Santini L, Hilbers JP, Huijbregts MAJ, Schipper AM (2020) Combined effects of land use and hunting on distributions of tropical mammals. Conserv Biol 34:1271–1280. https://doi.org/10.1111/cobi.13459

Gardner CJ, Davies ZG (2013) Rural bushmeat consumption within multiple-use protected areas: qualitative evidence from Southwest Madagascar. Hum Ecol 42:21–34. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10745-013-9629-1

Golden CD (2009) Bushmeat hunting and use in the Makira Forest, northeastern Madagascar: a conservation and livelihoods issue. Oryx 43:386–392. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0030605309000131

Golden CD, Comaroff J (2015) Effects of social change on wildlife consumption taboos in northeastern Madagascar. Ecol Soc 20:41. https://doi.org/10.5751/es-07589-200241

Golden CD, Fernald LC, Brashares JS, Rasolofoniaina BR, Kremen C (2011) Benefits of wildlife consumption to child nutrition in a biodiversity hotspot. Proc Natl Acad Sci 108:19653–19656. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1112586108

Harvey CA, Rakotobe ZL, Rao NS, Dave R, Razafimahatratra H, Rabarijohn RH, Rajaofara H, MacKinnon JL (2014) Extreme vulnerability of smallholder farmers to agricultural risks and climate change in Madagascar. Phil Trans R Soc B 369:20130089. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2013.0089

IPBES (2019) Global assessment report on biodiversity and ecosystem services of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services. IPBES secretariat, Bonn, Germany. https://doi.org/10.5281/ZENODO.3831673

Jenkins R, Racey P (2009) Bats as bushmeat in Madagascar. Madagascar Conserv Dev 3. https://doi.org/10.4314/mcd.v3i1.44132

Jenkins RK, Keane A, Rakotoarivelo AR, Rakotomboavonjy V, Randrianandrianina FH, Razafimanahaka HJ, Ralaiarimalala SR, Jones JP (2011) Analysis of patterns of bushmeat consumption reveals extensive exploitation of protected species in eastern Madagascar. PLoS ONE 6:e27570. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0027570

Jones JP, Mandimbiniaina R, Kelly R, Ranjatson P, Rakotojoelina B, Schreckenberg K, Poudyal M (2018) Human migration to the forest frontier: implications for land use change and conservation management. Geo: Geogr Environ 5:e00050. https://doi.org/10.1002/geo2.50

Jones S, Papworth S, Keane A, John FS, Smith E, Flomo A, Nyamunue Z, Vickery J (2019) Incentives and social relationships of hunters and traders in a Liberian bushmeat system. Biol Conserv 237:338–347. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2019.06.006

Kümpel NF, Milner-Gulland EJ, Cowlishaw G, Rowcliffe JM (2010) Incentives for Hunting: the role of Bushmeat in the Household Economy in Rural Equatorial Guinea. Hum Ecol 38:251–264. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10745-010-9316-4

Lee TM, Sigouin A, Pinedo-Vasquez M, Nasi R (2020) The Harvest of Tropical Wildlife for Bushmeat and Traditional Medicine. Annu Rev Environ Resour 45:145170. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-environ-102016-060827

Lehman SM, Rajaonson A, Day S (2006) Lemur responses to edge effects in the Vohibola III Classified Forest, Madagascar. Am J Primatol 68:293–299

McNamara J, Fa JE, Ntiamoa-Baidu Y (2019) Understanding drivers of urban bushmeat demand in a Ghanaian market. Biol Conserv 239:108291. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2019.108291

Merson SD, Dollar LJ, Johnson PJ, Macdonald DW (2019) Poverty not taste drives the consumption of protected species in Madagascar. Biodivers Conserv 28:3669–3689. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10531-019-01843-3

Milner-Gulland E, Bennett EL (2003) Wild meat: the bigger picture. Trends in Ecology& Evolution 18:351–357. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0169-5347(03)00123-x

Mittermeier RA, Louis EEJ, Richardson M, Schwitzer C, Langrand O, Rylands AB, Hawkins F, Rajaobelina S, Ratsimbazafy J, Rasoloarison R, Roos C, Kappeler P, Mackinnon J (2010) Lemurs of Madagascar. Conservation International, 3rd Edition

Morelli TL, Smith AB, Mancini AN, Balko EA, Borgerson C, Dolch R, Farris Z, Federman S, Golden CD, Holmes SM, Irwin M, Jacobs RL, Johnson S, King T, Lehman SM, Louis EE, Murphy A, Randriahaingo HNT, Randrianarimanana HLL, Ratsimbazafy J, Razafindratsima OH, Baden AL (2019) The fate of Madagascar’s rainforest habitat. Nat Clim Change 10:89–96. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-019-0647-x

Muhamad D, Okubo S, Harashina K, Parikesit, Gunawan B, Takeuchi K (2014) Living close to forests enhances people’s perception of ecosystem services in a forest-agricultural landscape of West Java, Indonesia. Ecosyst Serv 8:197–206. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoser.2014.04.003

Nasi R, Brown D, Wilkie D, Bennett E, Tutin C, van Tol G, Christophersen T (2008) Conservation and use of wildlife-based resources: the bushmeat crisis. Technical series 33, Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity, Montreal, and Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR), Bogor

Newbold T, Hudson LN, Hill SL, Contu S, Lysenko I, Senior RA, Börger L, Bennett DJ, Choimes A, Collen B, Day J, Palma AD, Diaz S, Echeverria-Londono S, Edgar MJ, Feldman A, Garon M, Harrison MLK, Alhusseini T, Ingram DJ, Itescu Y, Kattge J, Kemp V, Kirkpatrick L, Kleyer M, Correia DLP, Martin CD, Meiri S, Novosolov M, Pan Y, Phillips HRP, Purves DW, Robinson A, Simpson J, Tuck SL, Weiher E, White HJ, Ewers RM, Mace GM, Scharlemann JPW, Purvis A (2015) Global effects of land use on local terrestrial biodiversity. Nature 520:45–50. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature14324

Nielsen MR, Meilby H (2014) Hunting and trading bushmeat in the Kilombero Valley, Tanzania: motivations, cost-benefit ratios and meat prices. Environ Conserv 42:61–72. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0376892914000198

Nielsen MR, Pouliot M, Meilby H, Smith-Hall C, Angelsen A (2017) Global patterns and determinants of the economic importance of bushmeat. Biol Conserv 215:277–287. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2017.08.036

Posit team (2022) RStudio: Integrated Development Environment for R. Posit Software, PBC, Boston, USA. URL http://www.posit.co/

R Core Team (2022) R: a language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. https://www.R-project.org/

Ralimanana H, Perrigo AL, Smith RJ, Borrell JS, Faurby S, Rajaonah MT, Randriamboavonjy T, Vorontsova MS, Cooke RSC, Phelps LN, Sayol F, Andela N, Andermann T, Andriamanohera AM, Andriambololonera S, Bachman SP, Bacon CD, Baker WJ, Belluardo F, Birkinshaw C, Cable S, Canales NA, Carrillo JD, Clegg R, Clubbe C, Crottini A, Damasco G, Dhanda S, Edler D, Farooq H, de Lima Ferreira P, Fisher BL, Forest F, Gardiner LM, Goodman SM, Grace OM, Guedes TB, Hackel J, Henniges MC, Hill R, Lehmann CER, Lowry PP, Marline L, Matos-Maraví P, Moat J, Neves B, Nogueira MGC, Onstein RE, Papadopulos AST, Perez-Escobar OA, Phillipson PB, Pironon S, Przelomska NAS, Rabarimanarivo M, Rabehevitra D, Raharimampionona J, Rajaonary F, Rajaovelona LR, Rakotoarinivo M, Rakotoarisoa AA, Rakotoarisoa SE, Rakotomalala HN, Rakotonasolo F, Ralaiveloarisoa BA, Ramirez-Herranz M, Randriamamonjy JEN, Randrianasolo V, Rasolohery A, Ratsifandrihamanana AN, Ravololomanana N, Razafiniary V, Razanajatovo H, Razanatsoa E, Rivers M, Silvestro D, Testo W, Jiménez MFT, Walker K, Walker BE, Wilkin P, Williams J, Ziegler T, Zizka A, Antonelli A (2022) Madagascar’s extraordinary biodiversity: Threats and opportunities. Science 378. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.adf1466

Randimbiharinirina RD, Richter T, Raharivololona BM, Ratsimbazafy JH, Schüßler D (2021) To tell a different story: unexpected diversity in local attitudes towards endangered aye-ayes Daubentonia madagascariensis offers new opportunities for conservation. People and Nature 3:484–498. https://doi.org/10.1002/pan3.10192

Randriamamonjy VC, Keane A, Razafimanahaka HJ, Jenkins RK, Jones JP (2015) Consumption of bushmeat around a major mine, and matched communities, in Madagascar. Biol Conserv 186:35–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2015.02.033

Ratsimbazafy CL, Harada K, Yamamura M (2012) Forest resources use, attitude, and perception of local residents towards community based forest management: case of the Makira reducing emissions from deforestation and forest degradation (REDD) project, Madagascar. J Ecol Nat Environ 4:321–332

Reuter KE, Schaefer MS (2017) Motivations for the ownership of Captive lemurs in Madagascar. Anthrozoös 30:33–46. https://doi.org/10.1080/08927936.2017.1270589

Reuter KE, Randell H, Wills AR, Janvier TE, Belalahy TR, Sewall BJ (2016) Capture, movement, trade, and consumption of mammals in Madagascar. PLoS ONE 11:e0150305. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0150305

Ripple WJ, Abernethy K, Betts MG, Chapron G, Dirzo R, Galetti M, Levi T, Lindsey PA, Macdonald DW, Machovina B, Newsome TM, Peres CA, Wallach AD, Wolf C, Young H (2016) Bushmeat hunting and extinction risk to the world’s mammals. Royal Soc Open Sci 3:160498. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsos.160498

Sato H, Rabe H, Razanaparany TP (2021) Techniques used for illegal lemur hunting in Ankarafantsika National Park, northwestern Madagascar. Lemur News 23:11–14

Schüßler D, Radespiel U, Ratsimbazafy JH, Mantilla-Contreras J (2018) Lemurs in a dying forest: factors influencing lemur diversity and distribution in forest remnants of north-eastern Madagascar. Biol Conserv 228:17–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2018.10.008

Schüßler D, Mantilla-Contreras J, Stadtmann R, Ratsimbazafy JH, Radespiel U (2020) Identification of crucial stepping stone habitats for biodiversity conservation in northeastern Madagascar using remote sensing and comparative predictive modeling. Biodivers Conserv 29:2161–2184. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10531-020-01965-z

Schüßler D, Rabemananjara NR, Radriarimanga T, Rafamantanantsoa SM, Randimbiharinirina RD, Radespiel U, Hending D (2023) Habitat and ecological niche characteristics of the elusive hairy-eared dwarf Lemur (Allocebus trichotis) with updated occurrence and geographic range data. Am J Primatol 85:e23473. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajp.23473

Spira C, Raveloarison R, Cournarie M, Strindberg S, O’Brien T, Wieland M (2021) Assessing the prevalence of protected species consumption by rural communities in Makira Natural Park, Madagascar, through the unmatched count technique. Conserv Sci Pract 3:e441. https://doi.org/10.1111/csp2.441

Statements & Declarations

Thompson KET, Borgerson C, Wright PC, Randriamanetsy JM, Andrianantenaina MY, Andriamavosoloarisoa NNM, Razafindrahasy TA, Rothman RS, Surkis C, Bankoff RJ, Daniels C, Twiss KC (2023) A coupled humanitarian and biodiversity crisis in western Madagascar. Int J Primatol. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10764-022-00338-3

UNDP (2022) Human Development Report 2021/2022 - Uncertain Times – Unsettled Lives: Shaping our Future in a Transforming World

van Vliet N, Mbazza P (2011) Recognizing the multiple reasons for bushmeat consumption in urban areas: a necessary step toward the sustainable use of wildlife for food in Central Africa. Hum Dimensions Wildl 16:45–54. https://doi.org/10.1080/10871209.2010.523924

Vasey N (1996) Clinging to life: Varecia variegata rubra and the Masoala Coastal forests. Lemur News 2:7–9

Wilmé L, Waeber PO, Moutou F, Gardner CJ, Razafindratsima O, Sparks J, Kull CA, Ferguson B, Lourenço WR, Jenkins PD et al (2016) A proposal for ethical research conduct in Madagascar. Madagascar Conserv Dev 11:36–39

World Medical Association (2013) Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. http://www.wmanet/e/policy/b3htm

Ziegler S, Fa JE, Wohlfart C, Streit B, Jacob S, Wegmann M (2016) Mapping bushmeat hunting pressure in Central Africa. Biotropica 48:405–412. https://doi.org/10.1111/btp.12286

Acknowledgements

We thank the Directeur des Aires Protégées, des Ressources Naturelles Renouvelables et des Ecosystemes and the Ministre de l’Environnement et du Development Durable for issuing the research permit (No. 30/22/MEDD/SG/DGGE/DAPRNE/SCBE.Re). Further thanks go to the regional (Direction Régional de l’Environnement, de l’Ecologie et de Forêts, Madagascar National Parks and the chef de Cantonnement in Soanierana-Ivongo) and local authorities for their help and cooperation during this study. We are grateful to Deborah Rabesamihanta and Ange Nandrianina for supporting the key informant interviews and one anonymous reviewer for significantly improving the manuscript. Fieldwork was financed by the German Science Foundation (DFG) under grant number RA 502/23 − 1 to U.R.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. The fieldwork was supported by the German Science Foundation (DFG) under grant number RA 502/23 − 1 to U.R.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by Dominik Schüßler and Stephan Michel Rafamantanantsoa. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Dominik Schüßler and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Communicated by David Hawksworth.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Schüßler, D., Rafamantanantsoa, S.M., Ratsimbazafy, J.H. et al. Documentation of commercial and subsistence hunting of Critically Endangered black-and-white ruffed lemurs (Varecia variegata) in northeastern Madagascar. Biodivers Conserv 33, 221–237 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10531-023-02744-2

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10531-023-02744-2