Abstract

Optimism in conservation, and its potential impact on conservation practice, has been the focus of considerable recent attention. Dispositional optimism is the tendency to have positive expectations for the future, and previous research on optimism has focused particularly on the relationship between optimism and positive health outcomes. This research has concluded that optimism is generally a positive trait that can help people address problems, and set and achieve their goals. These characteristics may also be beneficial in conservation contexts. Using the revised Life Orientation Test, we measure dispositional optimism in conservation professionals to assess whether they are more or less optimistic than individuals who do not work in conservation, and whether there are differences in dispositional optimism between conservation professionals. We find that conservation professionals in the UK are more optimistic than a comparator sample of UK residents. Within conservation professionals, we do not find differences in dispositional optimism with age, gender, country of residence, employer, employment status, whether an individual thinks of themselves as a conservation biologist, or years working in conservation. We find weak evidence for lower dispositional optimism in conservation professionals working in Europe, Africa and South America. The most commonly expressed motivation for working in conservation was a feeling of love or connection, but we found no relationship between motivations and dispositional optimism. We did find that conservation professionals with higher dispositional optimism were more likely to be optimistic about the future of conservation, although no more likely to be optimistic about three specific conservation issues. Greater optimism in conservation professionals has important implications for conservation practice—optimists could benefit the success of the projects they work on, and benefit from the resilience that optimism provides, in a difficult sector where success is uncertain.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Even before the rise of the #oceanoptimism and #conservationoptimism movements, there has been interest in optimism in conservation. Numerous comments and editorials have discussed the optimism (or pessimism) of conservation professionals, the impact that this might have on conservation practice, and how positive or negative framing might influence messages about biodiversity conservation (Noss 1995; Beever 2000; Orr 2004, 2007; Webb 2005; Nugent 2007; Swaisgood and Sheppard 2010, 2011; Patten and Smith-Patten 2011; Knight 2013; Watters 2016; Balmford 2017; Morton 2017). These strongly felt statements have provoked debate and range from those which propose an advantage for optimism in biodiversity conservation (Beever 2000; Swaisgood and Sheppard 2011), to those which caution against optimistic “Pollyannas” who will reduce support for conservation by suggesting we have solved all the problems already (Noss 1995). There is also concern that optimism might affect recruitment, morale of conservation professionals, and even the resilience of conservation itself (Swaisgood and Sheppard 2010). It has also been suggested that an overly pessimistic approach to conservation communication might affect recruitment into the profession, and over time lead to an increasingly pessimistic workforce in biodiversity conservation (Swaisgood and Sheppard 2010). However, in spite of this interest in optimism, concern about its potential impacts on conservation, and the availability of psychometric tests to measure the optimism of individuals (Alarcon et al. 2013), we do not know how optimistic conservation professionals actually are.

Within publications on optimism in conservation, there is some conflation of the terms optimism and hope, and debate about what these terms mean and which is most appropriate for conservation (Orr 2004, 2007; Nugent 2007). In the psychological literature, there is a distinction between these two psychological constructs, with a recent meta-analysis suggesting that they are distinct but related traits (Alarcon et al. 2013). Optimism describes a tendency for positive expectations for the future (Carver et al. 2010), and it does not distinguish the means through which individuals believe these positive outcomes will occur, e.g. either through their own agency and abilities, or through aid from other people and/or institutional processes (Carver and Scheier 2014). In contrast, hope is thought to be made up of two sub-dimensions: the first is an individual’s determination to achieve their goals (agency), and the second is their ability to identify methods (pathways) to pursue these goals (Snyder et al. 1991). Here, we investigate optimism, due to the greater number of publications on this construct (Alarcon et al. 2013), and the greater recent attention on optimism in conservation.

Psychological research splits optimism into two different types, dispositional optimism and situational optimism (Carver and Scheier 2014). Whereas dispositional optimism is a personality trait that is relatively stable over time, situational optimism describes the expectation of positive outcomes that individuals possess or exhibit about a specific context (Tusaie and Patterson 2006); for example, how optimistic an individual is that we could reduce deforestation in the Amazon. Previous research has found that situational optimism is only weakly correlated with dispositional optimism (Tusaie and Patterson 2006). The psychological research on dispositional optimism gives a rich literature from which to infer potential impacts of optimism on conservation. In general, optimistic people address potential problems and their feelings about them, set and achieve goals, and pre-emptively tackle threats to their well-being (Segerstrom et al. 2017). One of the primary focuses of research in this area is the strong evidence for a positive correlation between dispositional optimism and positive health outcomes (Carver et al. 2010). It has been argued that this link might either be because optimists take a more proactive approach to health, or because they respond better to adversity (Carver and Scheier 2014). For example, a study of HIV positive patients showed that more optimistic patients had slower increases in viral load and slower decreases in CD4 counts, and were more likely to engage in positive behaviors such as exercising and lower cigarette smoking (Ironson et al. 2005). In the past, optimism in conservation has been seen as potentially detrimental due to concerns that optimists may no longer be realistic (Patten and Smith-Patten 2011). However, although there are negative characteristics associated with dispositional optimism, these seem restricted to specific contexts and are fewer than the advantages of optimism (Segerstrom et al. 2017). Risky situations are one context in which high dispositional optimism may be a disadvantage. In a gambling experiment where the odds of winning were fixed across all participants, optimists reported greater success than pessimists (Gibson and Sanbonmatsu 2004), and optimists also report reduced feelings of control when faced with failure (Norem and Chang 2002). Decisions in conservation often have to be made when there is considerable uncertainty about the outcomes of actions (Regan et al. 2005), and so the association between optimism and greater expectations when outcomes are risky (Gibson and Sanbonmatsu 2004) may not be beneficial for biodiversity conservation. In spite of these possible downsides, the resilience and proactive approach which is often correlated with higher dispositional optimism (Lee et al. 2013; Carver and Scheier 2014) may be beneficial for conservation professionals. In conservation, optimistic individuals may be more likely to take proactive action, which would be beneficial in what has been described as a “crisis discipline” (Soule 1985), and optimism has been associated with greater success in careers where failure is common (Forgeard and Seligman 2012). Dispositional optimism is also negatively correlated with depressive symptoms (Glaesmer et al. 2012), and so optimistic individuals may have greater resilience to cope with the reputation of conservation as “one of the most depressing sciences” (Swaisgood and Sheppard 2010) where people are “constantly faced with loss” (Hobbs 2013). The generally positive effects of dispositional optimism have led to a variety of research which investigates ways to increase optimism in an individual, and a recent meta-analysis has showed that it is possible to increase dispositional optimism (Malouff and Schutte 2017) using a variety of interventions.

In spite of the potential positive and negative effects of dispositional optimism on conservation, and the interest in conservation optimism, we do not yet know how optimistic conservation professionals are, nor whether dispositional optimism in conservation professionals is any different from dispositional optimism within the wider population. In this study, we use the revised Life Orientation Test (LOT-R; Scheier et al. 1994) to quantify the dispositional optimism of conservation professionals, and compare this to the optimism of a similar sample of individuals who do not work in conservation. There may also be differences between conservation professionals that could affect biodiversity conservation. We tested whether dispositional optimism differed within conservation professionals, specifically looking at employment sector, region of work and duration of employment in conservation. We also investigated the relationship between optimism and recruitment by testing whether there is a relationship between optimism and motivation for working in conservation. Finally, we tested whether there was a relationship between dispositional optimism and situational optimism, looking at optimism both about the future of conservation and about three conservation issues.

Methods

Survey design

The survey was designed and distributed using the software package Qualtrics (Qualtrics, Provo, UT). The survey was administered in English and started with demographic questions on gender, age and employment status (see supporting information for survey questions). Participants were also asked for country of residence and whether they considered themselves to work in biodiversity conservation. Participants who did consider themselves to work in biodiversity conservation were asked how long they had been working in conservation, their employer (academic, government, non-governmental organization or other), the broad geographic regions where they worked (participants could select more than one option), whether they considered themselves a conservation biologist, and their motivation for working in conservation (a free text box). Participants who did not consider themselves to work in biodiversity conservation skipped this section and were not asked these questions.

The next survey section focused on situational optimism. Participants were asked about their optimism about the future of conservation, and their optimism about three conservation issues: whether we can prevent the cheetah going extinct, whether cosmetic and cleaning products in the UK will be free from microbeads by 2020, and whether declines in UK bumblebees can be reduced. Bees and microbeads were chosen as they were topical issues receiving news coverage at the time of the survey, and we assumed participants were more likely to feel optimistic or pessimistic about conservation issues they had previously been exposed to. This rational was also used to select the cheetah as an example of a well-known charismatic mega-fauna of conservation concern (Durant et al. 2017), we assumed many conservation professionals would be familiar with the species. Participants answered these questions using a five point Likert scale (from very optimistic to very pessimistic). Finally, all participants were asked to complete the LOT-R (Scheier et al. 1994). The test consists of ten statements, and participants are asked to state their agreement on a five point Likert scale (from strongly disagree to strongly agree). Three statements assess optimism and are positively scored, and three statements assess pessimism and are negatively scored. Four statements are filler items. There remains debate on whether optimism and pessimism represent opposing ends of a single scale or are two distinct constructs (Hinz et al. 2017; Segerstrom et al. 2017), but here we consider optimism and pessimism as two extremes in a unidimensional construct (following Segerstrom et al. 2017). To calculate the LOT-R score, which can range from 0 to 24, the optimism and inverted pessimism scores are summed. Questions asked in the survey that are not included in this analysis are not reported here, but are included in the supporting information. These include more specific questions (for example, asking participants which species or ecosystems they worked with) that were designed to test for potential biases in participants (e.g. if all participants worked in the same area) but were voluntary and answered by only a small subsection of participants.

Distribution and ethical information

A sample of conservation professionals was targeted using seven online sampling drives. One drive consisted of posting a link on social media platforms (Twitter and Facebook), which generated 54.5% of participants. Unique links were also distributed by email to two conservation NGOs (generating 11.1% and 6.8% of participants), online in an article for Marine Ecosystems and Management (generating 15.7% of participants), and during three presentations by SP (generating 2.2%, 4.0%, and 5.8% of participants). Distribution occurred between April and October 2017. Participation in the survey was not limited to conservation professionals, but the question “do you consider yourself to work in biodiversity conservation?” was used to identify a self-classified group of conservation professionals, in the sense that they identified as being employed within the sector. This ensured an inclusive range from on-the-ground field staff to NGO executives. Individuals who answered negatively to this question were classified as non-conservation professionals, and were used as the comparator group to determine whether conservation professionals are more or less optimistic than the overall sampling population for the study. A total of 325 participants completed the primary survey targeted at conservation professionals. Of these 325 participants, 264 self-classified themselves as working in biodiversity conservation and were considered ‘conservation professionals’. Due to the location of the original postings, the sample had a strong bias toward participants from the UK, with 171 UK conservation professionals participating. This represents around 0.86% of the 20,000 conservation professionals working in the UK (Office for National Statistics UK 2018). As previous research on LOT-R has found significant differences in dispositional optimism between countries (Schou-Bredal et al. 2017), the comparison between conservation professionals and the comparator group was therefore restricted to individuals based in the UK. Of the participants, only 44 individuals from the UK did not consider themselves conservation professionals (suggesting the distribution methods successfully targeted the intended audience of conservation professionals). To gain a larger comparator group to assess whether dispositional optimism of conservation professionals differs from non-conservation professionals, the LOT-R scores of these 44 participants were supplemented with data for an additional 219 UK participants from a separate unpublished study on optimism and gardening by SP and RT. This combined sample is referred to as the ‘enlarged comparator group’ below. This survey on optimism and gardening was distributed using social media (Twitter, Facebook and an online newsletter) for six weeks in September and October 2017 and was targeted at people in the UK with gardens. This sample may have included conservation professionals, but no specific question was asked during this survey to identify conservation professionals. Seven participants with missing data were excluded, leaving a comparator group sample size of 256. All participants in both surveys were 18 or above in age, and no incentives were provided to complete the survey. At the end of the survey, participants were given feedback on their LOT-R score and typical LOT-R scores for someone of their age and gender. Both surveys were approved by the Royal Holloway ethical approval process. The datasets generated by this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Analyses

Analyses were conducted in RStudio 1.0.153 (R Studio Team 2016). There is debate about how to analyze Likert scale data (Carifio and Perla 2008), but to test for differences in dispositional optimism between conservation professionals (including both those based in the UK and elsewhere), the LOT-R score was expressed as binomial count data in a generalized linear model, so that predictions from the model were bounded at zero and 24. Employment sector (government, non-governmental organization, academia or other), whether the participant considered themselves a conservation biologist (binomial variable, yes or no), number of years working in conservation, and whether the participant worked in Europe, Asia, Africa, North America or South America (binomial variable, yes or no) were used as explanatory variables. Gender, age, and whether the participant was from the UK (binomial variable, yes or no) were also included as confounding factors. For analyses, categorical ranges of years working in conservation and age were assigned a numerical value at the mid-point of the category. McFadden’s R2 was calculated using the function pR2 in the pscl package (Jackman 2017). Wald’s tests were conducted using the function regTermTest in the survey package (Lumley 2004). To compare the dispositional optimism of conservation professionals to the enlarged comparator group, an identical model and methodology was used, with gender, age and employment status as potential confounding factors. Due to small sample size, unemployed and retired participants were classed together for this analysis.

Motivations for working in conservation were classified by SP and STT over two iterations, with discrepancies and classification definitions discussed between each iteration. RLT checked the clarity of classification definitions, and the assignment of statements of motivation into these categories. To determine whether there was a relationship between LOT-R score and motivations for working in conservation, we used individual logistic regressions (participants either did, or did not express a particular motivation) to test for relationships between LOT-R score and motivations expressed by > 15% of participants, using Bonferroni corrections for multiple tests to reduce the critical alpha value to 0.01. Finally, the relationship between situational optimism and dispositional optimism was assessed using ordinal logistic regression with the function polr in the MASS package (Venables and Ripley 2002). For the questions on microbeads and bees in the UK, we limited the sample to conservation professionals based in the UK.

Results

The mean LOT-R score for conservation professionals in the UK was 15.22 ± SD 4.05 (n = 171), which was higher than mean score of 13.54 ± SD 4.34 for the enlarged comparator group (Table 1; Odds ratios and Wald test; 1.33 95% CI 1.22–1.45, F1|415 = 41.99, p < 0.001, McFadden R2 = 0.05), indicating higher dispositional optimism in conservation professionals. Male participants were less optimistic than females (Odds ratio and Wald test; 0.83 95% CI 0.76–0.91, F1|415 = 16.47, p < 0.001). Dispositional optimism also increased with age and employment status (Wald tests; age: F4|415 = 10.26, p < 0.001; employment: F3|415 = 12.08, p < 0.001), with retired, unemployed and part time workers having lower dispositional optimism.

The mean LOT-R score for the 264 conservation professionals who participated in the research was 15.48 ± SD 4.06. Conservation professionals working in Europe, Africa, and South America had lower dispositional optimism (15.26 ± SD 4.23, 14.63 ± SD 4.34, 14.35 ± SD 4.60 respectively) than participants who did not work in these areas (Table 2), but overall the model explained very little variation in the data (generalized linear model with a binomial count response variable, McFadden R2 = 0.03).

In our dataset, 262 conservation professionals described what motivated them to work in biodiversity conservation. These responses were classified into 16 general motivations for working in biodiversity conservation (Table 3). Responses could be placed into more than one category, but the most common motivation (reported by 39.3% of participants) was a love for or connection with something, whether individual species or particular places, or a more general love for nature. There was no relationship between LOT-R score and any of the five most frequently reported motivations for working in biodiversity (Odds ratios and Wald tests; love: 0.977 95% CI 0.919–1.040, F1|260 = 0.543, p = 0.462, McFadden R2 = 0.00; interest: 1.108 95% CI 1.020–1.210, F1|260 = 5.559, p = 0.019, McFadden R2 = 0.02; concern: 0.955 95% CI 0.886–1.041, F1|260 = 1.435, p = 0.232, McFadden R2 = 0.00; personal experience: 0.996 95% CI 0.922–1.079, F1|260 = 0.010, p = 0.920, McFadden R2 = 0.00; desire to make a difference: 0.997 95% CI 0.920–1.084, Wald test, F1|260 = 0.007, p = 0.934, McFadden R2 = 0.00).

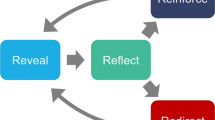

When asked about the future of conservation, the most commonly selected option by conservation professionals was ‘slightly optimistic’ (101 of 263). However, conservation professionals with higher dispositional optimism were more likely to be very optimistic about the future of conservation, whereas those with lower dispositional optimism were more likely to be very or slightly pessimistic (Fig. 1, odds ratio 1.087 [95% CI 1.028–1.150], t = 2.90, p = 0.004, n = 263). Conservation professionals were also most likely to be ‘slightly optimistic’ about preventing cheetah extinction (132 of 263), and conservation professionals in the UK most commonly selected ‘slightly optimistic’ to describe their attitude to reversing bee decline and banning microbeads (77 and 61 of 170 respectively). However there was no relationship between dispositional optimism and situational optimism for these three specific conservation issues (preventing cheetah extinction: odds ratio = 1.054 [95% CI 0.996–1.116], t = 1.84, p = 0.066, n = 263; reversing bee declines: odds ratio = 1.061 [95% CI 0.989–1.139], t = 1.65, p = 0.099, n = 170; banning microbeads: 1.032 [95% CI 0.963–1.106], t = 0.877, p = 0.381, n = 170).

Discussion

Our study sample suggests that conservation professionals in the UK are more optimistic than individuals who do not work in conservation. The mean LOT-R score of non-conservation professionals in this study (13.54 ± SD 4.34) is lower than previous measures in the UK (14.7 and 13.9; Walsh et al. 2015), though the mean LOT-R score of conservation professionals in this study (15.22 ± SD 4.05) is still higher than these previous UK estimates. It is likely that the sample of non-conservation professionals is not entirely representative of the UK population, as sampling was conducted online, and the sample was of individuals who self-selected to participate in a survey on gardening. Potential bias from online sampling was however consistent for both the conservation professionals and non-conservation professionals. In spite of these caveats, this is the first time that dispositional optimism has been investigated in conservation professionals, and provides an initial evidence base to support debate on the potential implications of optimism for conservation.

Even though conservation professionals were found to be more optimistic than non-conservation professionals in this study, it should not be concluded that conservation professionals are universally optimistic. Our non-random sample of conservation professionals contained a wide range of possible LOT-R scores (from 1 to 24), which may contribute to the resilience of the discipline, as different individuals may be better placed to deal with different aspects of the diverse range of situations and contexts that conservation involves on a practical level. In addition to the broad range of LOT-R scores, we found little evidence of differences in dispositional optimism between different groups of conservation professionals in the sample. Other studies on dispositional optimism have found small differences in dispositional optimism between individuals from different countries, of different ages, and between men and women (Glaesmer et al. 2012; Hinz et al. 2017; Schou-Bredal et al. 2017). Not only did we fail to identify these differences in our sample of conservation professionals, we also did not find evidence of differences in dispositional optimism with employment sector, employment status or number of years working in conservation. We did find some evidence to suggest that conservation professionals in Africa, Europe and North America had lower dispositional optimism, but overall there was very low support for our model. As we did detect differences in dispositional optimism with age, gender and employment status in the combined sample of conservation professionals and the comparator group, it is possible that these effects were present in the sample of conservation professionals but we failed to detect differences due to a comparatively small sample size compared to studies which did detect demographic differences in dispositional optimism (e.g. n = 2372 in Glaesmer et al. 2012).

There are two possible mechanisms that might lead to higher dispositional optimism in conservation professionals. Conservation may attract more optimistic individuals, or there may be a strong selection pressure for optimists very early in their conservation career, leading less optimistic people to leave the sector. If the second explanation were true, we might expect to find a positive relationship between LOT-R score and number of years working in conservation. We did not find this relationship, but to distinguish accurately between these two hypotheses, it would be necessary to conduct a longitudinal study that measures the dispositional optimism of entry-level conservation professionals and follow their careers to establish whether less optimistic individuals leave the sector. The motivations expressed by conservation professionals in our study for working in conservation are similar to those identified in other studies of similar groups, e.g. biodiversity activists (Admiraal et al. 2017). The most common reported motivation was a love of or connection with something, ranging from a love for particular places and species to more general statements about nature or animals. The fact that love and other positive motivations (e.g. interest and enjoyment) were so commonly mentioned provides further evidence to support the role of positive emotions in promoting pro-environmental behaviors and attitudes (Corral Verdugo 2012; Powell and Bullock 2015). However, not all participants mentioned these as motivations, and there was considerable diversity in the reasons why people reported that they work in conservation. Of the five motivations which were given by at least 15% of participants, given the known psychological correlates of optimism (recognizing and tackling problems), we might expect participants who expressed a desire to make a difference to be more optimistic, but we did not find this relationship. Indeed, we did not find any evidence for a relationship between dispositional optimism and motivation for working in conservation. This analysis does not specifically address whether positive or negative messaging might affect recruitment of either optimists or pessimists (as suggested by Swaisgood and Sheppard 2010), but we did not find any evidence for differences in dispositional optimism with either motivation for working in conservation or number of years working in conservation. However, as optimists and pessimists respond similarly to successes, but differently to failure (Norem and Chang 2002; Forgeard and Seligman 2012), efforts to refocus conservation discourse on conservation successes may be beneficial for both optimists and pessimists.

It may be that there are consistent differences in dispositional optimism between different groups of conservation professionals that were not identified in this study. For example, the greater expectations of optimists in risky situations (Gibson and Sanbonmatsu 2004) may make them more likely to work with critically endangered or data deficient species, where there is greater uncertainty about the outcomes of conservation action. It is also possible that although individuals have low dispositional optimism, they are optimistic about specific conservation topics. We found that although more optimistic participants were more likely to be more optimistic about the future of conservation in general, they were no more likely to be optimistic about three different specific conservation contexts. Previous research on dispositional and situational optimism in an environmental context also found no relationship between optimism about future environmental conditions (as measured using the Environmental Future Scale of Gifford et al. 2009) and LOT-R scores (Milfont et al. 2011). Therefore, even conservation professionals with low levels of dispositional optimism may be very optimistic about specific conservation problems, and vice versa.

We show that conservation professionals, at least in this UK-based sample, are more optimistic than a comparator sample of non-conservation professionals. As optimism may be linked to specific behaviors and perceptions which could affect conservation practice, it may be useful for conservation professionals to be aware of their own levels of optimism, which they can measure using the LOT-R at www.conservationbehaviour.com/conservation-optimism. Awareness of their own levels of dispositional optimism may allow conservation professionals to reflect on their own perceptions of conservation problems, and how they communicate these to others. We still do not know the mechanism behind the observed differences in dispositional optimism found here, but this could be investigated through a longitudinal study of recruitment and retention in conservation. Potential future avenues for research include investigating a wider range of potential traits that may affect conservation practice, from the very general (for example, the five factor personality model) to the specific (for example risk aversion). Longitudinal research on how these traits and optimism are related to the recruitment and retention of conservation professionals, and whether these traits are equally distributed across individuals in different types of conservation work or different organizations, may provide further insights on how individuals and organizations within conservation work (or do not work) together.

References

Admiraal JF et al (2017) Motivations for committed nature conservation action in Europe. Environ Conserv 44:148–157

Alarcon GM, Bowling NA, Khazon S (2013) Great expectations: a meta-analytic examination of optimism and hope. Personal Individ Differ 54:821–827

Balmford A (2017) On positive shifting baselines and the importance of optimism. Oryx 51:191–192

Beever E (2000) The roles of optimism in conservation biology. Conserv Biol 14:907–909

Carifio J, Perla R (2008) Resolving the 50-year debate around using and misusing Likert scales. Med Educ 42:1150–1152

Carver CS, Scheier MF (2014) Dispositional optimism. Trends Cogn Sci 18:293–299

Carver CS, Scheier MF, Segerstrom SC (2010) Optimism. Clin Psychol Rev 30:879–889

Corral Verdugo V (2012) The positive psychology of sustainability. Environ Dev Sustain 14:651–666

Durant SM et al (2017) The global decline of cheetah Acinonyx jubatus and what it means for conservation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 114:528–533

Forgeard MJC, Seligman MEP (2012) Seeing the glass half full: a review of the causes and consequences of optimism. Prat Psychol 18:107–120

Gibson B, Sanbonmatsu DM (2004) Optimism, pessimism, and gambling: the downside of optimism. Pers Soc Psychol Bull 30:149–160

Gifford R et al (2009) Temporal pessimism and spatial optimism in environmental assessments: an 18-nation study. J Environ Psychol 29:1–12

Glaesmer H, Rief W, Martin A, Mewes R, Brähler E, Zenger M, Hinz A (2012) Psychometric properties and population-based norms of the Life Orientation Test Revised (LOT-R). Br J Health Psychol 17:432–445

Hinz A, Sander C, Glaesmer H, Brähler E, Zenger M, Hilbert A, Kocalevent R-D (2017) Optimism and pessimism in the general population: psychometric properties of the Life Orientation Test (LOT-R). Int J Clin Health Psychol 17:161–170

Hobbs RJ (2013) Grieving for the past and hoping for the future: balancing polarizing perspectives in conservation and restoration. Restor Ecol 21:145–148

Ironson G, Balbin E, Stuetzle R, Fletcher MA, O’Cleirigh C, Laurenceau JP, Schneiderman N, Solomon G (2005) Dispositional optimism and mechanisms by which it predicts slower disease progression in HIV: proactive behavior, avoidant coping, and depression. Int J Behav Med 12:86–97

Jackman S (2017) pscl: classes and methods for R developed in the political science computational laboratory. United States Studies Centre, University of Sydney, Sydney, Australia. https://github.com/atahk/pscl/

Knight AT (2013) Reframing the theory of hope in conservation science. Conserv Lett 6:389–390

Lee JH, Nam SK, Kim A-R, Kim B, Lee MY, Lee SM (2013) Resilience: a meta-analytic approach. J Couns Dev 91:269–279

Lumley T (2004) Analysis of complex survey samples. J Stat Softw 9:1–19

Malouff JM, Schutte NS (2017) Can psychological interventions increase optimism? A meta-analysis. J Posit Psychol 9760:1–11

Milfont TL, Wokje A, Mccarthy N (2011) Spatial and temporal biases in assessments of environmental conditions in New Zealand. N Z J Psychol 40:56–67

Morton SR (2017) On pessimism in Australian ecology. Austral Ecol 42:122–131

Norem JK, Chang EC (2002) The positive psychology of negative thinking. J Clin Psychol 58:993–1001

Noss RF (1995) The perils of Pollyannas. Conserv Biol 9:701–703

Nugent C (2007) Optimism versus hope. Conserv Biol 21:1396

Office for National Statistics, UK (2018) Number of employed conservation and environment professionals in the United Kingdom (UK) in 2018, by occupation (1000 s). In: Statista—The Statistics Portal. Retrieved October 22, 2018, from https://www.statista.com/statistics/778339/conservation-and-environment-professionals-employed-uk/

Orr DW (2004) Hope in hard times. Conserv Biol 18:295–298

Orr DW (2007) Optimism and hope in a hotter time. Conserv Biol 21:1392–1395

Patten MA, Smith-Patten BD (2011) “As If” philosophy: conservation biology’s real hope. Bioscience 61:425–426

Powell DM, Bullock EVW (2015) Evaluation of factors affecting emotional responses in zoo visitors and the impact of emotion on conservation mindedness. Anthrozoös 27(3):389–405

R Studio Team (2016) R Studio: integrated development for R Studio, Inc. Boston, MA. http://www.rstudio.com/

Regan HM, Ben-Haim Y, Langford B, Wilson WG, Andelman SJ, Burgman MA, Andelman SJ, Burgman MA (2005) Robust decision-making under severe uncertainty for conservation management. Ecol Appl 15:1471–1477

Scheier MF, Carver CS, Bridges MW (1994) Distinguishing optimism from neuroticism (and trait anxiety, self-mastery, and self-esteem): a reevaluation of the Life Orientation Test. J Pers Soc Psychol 67:1063–1078

Schou-Bredal I, Heir T, Skogstad L, Bonsaksen T, Lerdal A, Grimholt T, Ekeberg Ø (2017) Population-based norms of the Life Orientation Test- Revised (LOT-R). Int J Clin Health Psychol 17:216–224

Segerstrom SC, Carver CS, Scheier MF (2017) Optimism. In: Robinson MD, Eid M (eds) The happy mind: cognitive contributions to well-being. Springer, New York, pp 195–214

Snyder CR, Harris C, Anderson JR, Holleran SA, Irving LM, Sigmon ST, Yoshinobu L, Gibb J, Langelle C, Harney P (1991) The will and the ways: development and validation of an individual-differences measure of hope. J Pers Soc Psychol 60:570–585

Soule ME (1985) What is conservation biology? Bioscience 35:727–734

Swaisgood RR, Sheppard JK (2010) The culture of conservation biologists: show me the hope! Bioscience 60:626–630

Swaisgood RR, Sheppard J (2011) Hope springs eternal: biodiversity conservation requires that we see the glass as half full. Bioscience 61:427–428

Tusaie KR, Patterson K (2006) Comparative optimism: clarifying concepts for a theoretically consistent and evidence-based intervention to maximize resilience. Arch Psychiatr Nurs 20:144–150

Venables WN, Ripley BD (2002) Modern applied statistics with S, 4th edn. Springer, New York

Walsh D, Mccartney G, Mccullough S, Van Der Pol M, Buchanan D, Jones R (2015) Always looking on the bright side of life? Exploring optimism and health in three UK post-industrial urban settings. J Public Health 37:389–397

Watters JV (2016) On optimism and pessimism in conservation science and messaging. Zoo Biology 279:94132

Webb CO (2005) Engineering hope. Conserv Biol 19:275–277

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the participants in this study for their time in completing the survey.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Communicated by Dirk Sven Schmeller.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Papworth, S., Thomas, R.L. & Turvey, S.T. Increased dispositional optimism in conservation professionals. Biodivers Conserv 28, 401–414 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10531-018-1665-0

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10531-018-1665-0