Abstract

Evidence-based assessments of extinction risk are established tools used to inform the conservation of plant species, and form the basis of key targets within the framework of the Global Strategy for Plant Conservation (GSPC). An overall picture of plants threat assessments is challenging due to the use of a variety of methodologies and range in scope from global to subnational. In this study, we quantify the state of progress in assessing the extinction risk of all land plants, determine the key geographic and taxonomic gaps with respect to our understanding of plant extinction risk, and evaluate the impact of different sources and methodologies on the utility of plant assessments. To this end, we have analyzed a cleaned dataset compiled from IUCN Red List of Threatened Species and Regional Red Lists. We reveal that there are assessments available for 89,810 distinct species or 25% of all accepted land plant species. However unlike with other major organismal lineages the bulk of the plant species assessments are derived from Regional Red Lists, and not the Global IUCN Red List. We demonstrate that this bias towards regional assessments results in distinct taxonomic and geographic strengths and weaknesses, and we identify substantial taxonomic and geographic gaps in the assessment coverage. With species that have been assessed in common at both global and regional levels, we explore the implications of combining threat assessments from different sources. We find that half of global and regional assessments do not agree on the exact category of extinction risk for a species. Regional assessments assign a higher risk of extinction; or underestimate extinction risk with almost equal frequency. We conclude with recommended interventions, but support the suggestion that all threat assessments should be pooled to provide more data and broaden the scope of threat assessments for monitoring progress towards GSPC targets.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

At the tenth Conference of the Parties to the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) it was widely accepted that the proposed 2010 Biodiversity target to significantly reduce the rate of biodiversity loss had not been met (Balmford et al. 2005; Walpole et al. 2009; Butchart et al. 2010; Brummitt et al. 2015). The Parties to the Convention responded by declaring a Decade of Biodiversity, and Decision X/2 in particular which sets out 20 new biodiversity targets (Tittensor et al. 2014). In response to the CBD, a plant-specific program called the Global Strategy for Plant Conservation (GSPC) (Wyse Jackson and Kennedy 2009) set sixteen targets for the conservation of plant species by the year 2020 (Paton and Lughadha 2011). Of these sixteen targets, three GSPC targets make specific reference to threatened plant species.

GSPC Target 2 calls for assessment of the threat status of all known plant species, as far as possible, to guide conservation action. GSPC Target 7 calls for at least 75% of known threatened plant species to be conserved in situ. GSPC Target 8 requires that at least 75% of threatened plant species are held in ex situ collections, preferably in the country of origin, with at least 20% available for recovery and restoration programs (Paton and Lughadha 2011). Clearly gains towards GSPC Target 2 are required before progress towards GSPC Target 7 and GSPC Target 8 can be meaningfully measured and monitored.

Threatened species assessments are the central component of GSPC Target 2 (Wyse Jackson and Kennedy 2009), and provide an easily understood and qualitative estimate of extinction risk for different species (Possingham et al. 2002). All threatened species assessments generate an evidence informed assertion on the probability of decline of a particular taxon (Possingham et al. 2002), a principle exemplified by the leading protocol for global evidence-based conservation assessment, the global IUCN Red List of Threatened Species (IUCN-RL). The IUCN-RL classifies species on a qualitative scale, as threatened (Critically Endangered, Endangered, or Vulnerable), not threatened (Near Threatened or Least Concern), extinct (Extinct, Extinct in the Wild), or about which there is insufficient information to categorize (Data Deficient) (Fig. 1). To be added to the published global IUCN Red List, species need to be evaulated against quantitative thresholds of the following criteria: (1) decline in population size, (2) small geographic range, (3) small population size plus decline, (4) very small population size, or (5) quantitative analysis. However, assessments are inevitably linked to subsequent decision-making processes that include evaluating adverse impacts on threatened species, advising conservation priorities, and informing regional environmental assessments (Possingham et al. 2002). The use of threatened species assessments to inform such decision-making processes and downstream legislation has received criticism, due to their qualitative nature, application to multiple objectives, variety of end users, and for the different protocols used to generate different assessments (Possingham et al. 2002). Nonetheless, threatened species assessments are established tools for biological conservation because they provide quantitative, actionable, and evidence-based data (Collen et al. 2016).

The structure and relations of the IUCN-RL Categories and Criteria version 3.1. The three categories within the dotted line box form the ‘threatened’ categories. http://www.iucnredlist.org/static/categories_criteria_3_1

In addition to the internationally focused IUCN-RL, there is a wide range of different types of lists for threatened plant species that focus on assessments on a sub-global scale, termed Regional Red Lists or RRL, including: sub-national assessments (Chua et al. 2010; Cortini Pedrotti and Aleffi 2011; Ah-Peng et al. 2012); national assessments (Dines et al. 2005; Natcheva et al. 2006; Tefnu and Goia 2012, and many others listed at http://www.nationalredlist.org/t); supra-national but sub-global assessments (Eastwood et al. 2009; Bilz et al. 2011); assessments of particular ecological habitats (Witkowski et al. 2003; González-Espinosa et al. 2011) and; focused assessments on endemic species (León-Yánez et al. 2011). The extent of RRL has been rapidly increasing in response to the 2020 Biodiversity Targets (Rodriguez 2008; Zamin et al. 2010). RRL have five major functions: classifying the status of species at the level at which they are managed, evaluating locally threatened taxa, informing local conservation priorities, providing data for global assessments, and underpinning the legal protection of species (Rodriguez 2008; Zamin et al. 2010; Harris et al. 2012). RRL can commonly use the same or similar criteria as the IUCN-RL to assess extinction risk, but exact processes can vary and may not be consistent between different regions. Given their prevalence and importance for conservation, a number of studies have sought to compare RRL with IUCN-RL assessments in order to integrate RRL data into the global IUCN-RL (Rodriguez 2008; Moser et al. 2016), or to apply IUCN-RL assessments and criteria at regional levels (Gärdenfors et al. 2001). Typically, comparisons between RRL and IUCN-RL assessments will find differences in total number of evaluated taxa (Rodriguez 2008; Brito et al. 2010), in the geographic distribution of assessments (Brito et al. 2010; Zamin et al. 2010), in taxonomic sampling (Rodriguez 2008; Zamin et al. 2010), and in the level of threat status assigned to the same species (Brito et al. 2010; Morais et al. 2012; Harris et al. 2012; Helfman 2013). Differences in the level of threat status assigned can be further distinguished into three categories: (1) differences in abundance of individual species at different geographic scales such that a species will have fewer populations at sub-global scales leading to a higher category of assigned threat status at sub-global levels; (2) different scientific understanding resulting in differing species delineations, change in status over time, altered interpretation of the same data, and new or rediscovered species; (3) discrepancies that result from regional inequalities in the availability of financial resources and expertise, regional differences in the value attached to different units and types of biodiversity, politicization or bureaucracy associated with regional and global assessments, the application of different protocols, and the misapplication of common protocols (Collen et al. 2008; Kozlowski 2008; Brito et al. 2010; Zamin et al. 2010).

Clearly such differences between assessment lists can challenge the evaluation of GSPC targets, as articulated by a recent assessment of progress towards GSPC Target 2. A recent CBD report (CBD 2014) concluded that the proportion of plants assessed globally by IUCN has only reached approximately 6% of total plant diversity, but that many more plant species have been assessed at a regional level by a variety of different systems. It should be noted that many of these regional assessments will be of endemic species, and essentially constitute global assessments, and thus this figure of 6% was always likely to be an under-estimate of global assessments. Nonetheless, given the degree of fragmentation in threat assessments, the report identified that a global perspective on progress toward GSPC Target 2 is lacking, and made the following recommendations: (a) A working list of all available evidence-based conservation assessments for plants, to be maintained as an online resource and developed to include all plant species by 2020; (b) a published interim threatened species list, an output from (a) above, from which other GSPC targets can be measured by 2015; (c) An assessment of the threat status of a globally representative sample of plant species by 2015; and (d) Regional Red Lists developed or updated to assist in obtaining an overview of threat levels at a global level. Of these recommendations, (a) has been met (see https://www.bgci.org/threat_search.php), and (c) has been met through the IUCN Sampled Red List Index for Plants (SRLI) (Brummitt et al. 2015), which has extrapolated sampled species to non-assessed species and estimated that over 20% of plant species are threatened with extinction. However while the SRLI provides an important baseline measure, it does not provide the necessary foundation of data for GSPC Target 7 and 8 which deal with in situ and ex situ conservation.

In light of the recommendations from the 2010 progress report, we have analysed a cleaned dataset of evidence-based conservation assessments derived from both RRL and IUCN-RL sources ((a) above). We have then compared RRL and IUCN-RL derived data, and sought to evaluate the different datasets in light of the following questions: (a) what assessment sources are driving the accumulation of plant conservation assessments? (b) what proportion of land plant species have been subject to conservation assessment, and subsequently what percentage been found to be threatened? (c) to what extent do these assessments, and different sources of assessment, adequately and equitably represent the phylogenetic diversity of land plants, and their geographic distributions? d) to what extent do different sources affect the level of assigned threat status, and what are the implications for merging assessments? In answering these questions, we hope to assess whether we have information available that is sufficiently relevant, sensitive, and unbiased to establish a baseline against which subsequent progress towards GSPC targets can be measured, and to provide a better theoretical understanding of the data, to help identify interventions that may be needed, to increase the extent, quality and utility of evidence-based threat assessments of plants.

Methods

Data acquisition and management

We downloaded the full list of 20755 IUCN-RL assessed plant species corresponding to version 2015-4 from the IUCN-RL website on January 4th 2016. Conservation assessments for plant species were obtained from a pre-release version of BGCI ThreatSearch (https://www.bgci.org/threat_search.php, accessed: 2016-02-10). After acquisition in UTF8-encoded, plain text, CSV format, all of the data was tracked in a private git repository to ensure that all subsequent changes to the data were traceable and recorded (Ram 2013).

Data cleaning and normalisation

Both IUCN-RL and Regional Red List data were filtered to remove assessments of taxa that were out of scope for this study e.g. fungal, algal, and animal taxa. We then computationally-normalised the taxonomy of both IUCN-RL and RRL assessment data using the R package Taxonstand (Cayuela et al. 2012) version 1.8. Species that could not be automatically matched to a species name listed at The Plant List v1.1 (hereafter TPL; TPL 2013) were manually resolved to the correct species name or discarded if the taxon was not validly published. Examples of discarded un-recognised taxa include “Asparagus sp. nov. A” (Miller 2004) and “Eugenia sp. nov. lepredourii’” (Hequet 2010) on the IUCN-RL. After normalisation to TPL, some taxa were demoted from species rank in the original assessment to subspecies rank e.g. Arenaria bolosii which is Critically Endangered on the IUCN-RL (Bibiloni and Mus 2006) but is deemed to be only a subspecies by TPL, Arenaria grandiflora subsp. bolosii (Cañig.). For consistency and comparability only species-level taxa were retained for analysis, subspecies taxon assessments were discarded. Less than 0.5% of the original assessments were discarded through taxonomic normalisation to a subspecies rank. Likewise after taxonomic normalisation to TPL some assessments had to be discarded because of synonymy e.g. TPL considers Aglaia cinnamomea Baker f. to be a synonym of the accepted name Aglaia elliptica (C.DC.) Blume. The IUCN-RL assesses A. cinnamomea as Vulnerable (Pannell 1998a) and A. elliptica as Least Concern (Pannell 1998b), TPL considers Aglaia cinnamomea to be a synonym of the accepted name Aglaia elliptica thus we retained A. elliptica as Least Concern and discarded the assessment for A. cinnamomea. In such cases of synonymy involving two or more assessments from the same data source we kept the accepted species name and its associated status. Where a species has more than one regional-level assessment we selected the least imperiled regional-level assessment to represent the species. After all these data processing steps we were left with 20,367 IUCN-RL, and 75,255 Regional and RRL assessments of TPL-normalised, land plant species. All of these steps are summarized in Fig. 2. The complexity of change over time in taxonomy and species concepts is such that for robustness-sake when comparing between IUCN-RL and RRL assessments we provide two separate analyses (Fig. 8a, b), one including and one excluding synonym-affected conservation assessments to provide both conservative and relaxed analyses with respect to matching taxon circumscriptions.

Higher-level classification annotation

We used the R package taxonlookup version 1.1.1 (Pennell et al. 2016) to annotate every included assessment species with current information on higher-classification of the taxon: Family, Order and Higher-level group. We also used taxonlookup to provide authoritative species counts per genus, family, order, and higher-level hierarchies based upon TPL accepted species names only (e.g. for Fig. 5). By using accepted names-only we recognise that the species totals will be a minimum estimate with many unresolved names on the TPL.

Geographic occurrence and endemicity

IUCN-RL provides data on known countries of occurrence of each species for all IUCN-RL assessed species, so we used this data as count data per country. For the set of species with only regional assessments, we used the country issuing the RRL assessment as the occurrence data for that species. We are aware that species nationally listed in one country may also occur in other countries—our data therefore serve as lower bounds on the true extent of country-level occurrence for nationally assessed species. Where a species is assessed by both the IUCN-RL and at least one RRL, we use the country-level occurrence data given by IUCN-RL. For analyses of combined IUCN-RL and RRL assessments we avoided double counting the same species in the same country (Figs. 7, 8). For the purpose of this study we define an endemic species as one that is present in only one country, with ‘countries’ defined as one of 249 territories recognized by the ISO 3166-1 standard. In order to assess country-endemicity of each IUCN-RL species (shown in Fig. 6b) we used official IUCN-RL data that provides country-level distribution information for each assessment taxon. Assessments of country-endemicity relied solely upon IUCN-RL data that provides country-level distribution information for each assessed taxon. There have been many significant critiques of uncritical use of online species occurrence data (Yesson et al. 2007; Beck et al. 2013, 2014; Mesibov 2013; Otegui et al. 2013), so we emphasize here that in this case we are only interested in accuracy to the country-level for the purpose of assessing endemicity. As opposed to species distribution modeling, a relatively coarse country-level analysis is justified here, since the implementation of CBD and GSPC are focused with respect to country boundaries.

Standardising conservation assessment classification

We standardised assessments where possible to IUCN 3.1 Categories and Criteria. Thus permitted assessment classifications were Data Deficient (DD), Least Concern (LC), Near Threatened (NT), Vulnerable (VU), Endangered (EN), Critically Endangered (CR), Regionally Extinct (RE), Extinct in the Wild (EW), and Extinct (EX). The vast majority of included RRL assessments use IUCN Criteria for assessing extinction risk. However, RRL assessments such as ‘Rare’ and ‘Very Rare’ were excluded from all analyses as the natural rarity of taxa is distinct to assessment of extinction risk. Furthermore, we decided that we could not confidently reconcile Mexican governmental extinction risk assessments (NOM-059-SEMARNAT-2010) with IUCN Criteria, so we do not include these in any analyses. For reconciling NatureServe (North American non-profit assessor) criteria we follow NatureServe’s own guidance (NatureServe 2012) and assign the following as equivalents: GX = EX, GXC = EW, GH = RE, G1 = CR or EN, G2 = VU, G3 = NT, G4 = LC, G5 = LC. For a species with a NatureServe G1 assessment we score the difference conservatively e.g. the difference between a G1 and VU assessment is counted as just 1 (treating G1 as EN) and the difference between a G1 and EX assessment is counted as just 3 (treating G1 as CR). For all relevant calculations we define ‘threatened’ as those species that have been assessed as either VU, EN or CR.

Ranked-comparisons between assessments

For the purpose of comparison between global IUCN-RL and RRL assessments for the same species, each assessment status was also given an equivalent numerical score: LC = 7, NT = 6, VU = 5, EN = 4, CR = 3, RE = 2, EW = 1, EX = 0. This is an arbitrarily-chosen scoring system (c.f. Moser et al. 2016) designed to promote clarity where there is a difference in threat assessment rank; we do not intend to symbolize that CR(3) is somehow twice as imperiled as NT(6), or that the difference between NT and VU is the same as the difference between EW and EX—these numbers are indications of relative rank only and the difference of 1 unit between them is purely to provide interpretive clarity. Our ‘Difference in Assessment’ for a species between IUCN-RL and RRL is the numerical score for the IUCN-RL assessment minus the numerical score for the RRL assessment. The Difference in Assessment is thus an integer bounded between − 7 and + 7. Species assessments of Data Deficient (DD) or Not Evaluated (NE), were discarded as incomparable. As an illustrative example we discuss the Difference in Assessment for the species Hopea shingkeng between IUCN-RL and China’s Higher Plants Red List (Zhao et al. 2014). The IUCN-RL has an assessment for this species listing it as Extinct (0) (Ashton 1998), whilst China’s Higher Plants Red List assesses it as Endangered (4). The Difference in Assessment for this species is thus considered to be − 4 (0 minus 4). We note that both of these assessments cannot simultaneously be true for this species; it is either extinct OR extant, these are mutually exclusive conditions, but without further information we cannot further determine which assessment is correct. Nevertheless it objectively highlights a significant conflict in assessment for a species. Differences in assessments were statistically modelled using the lm() function of the ‘stats’ R package (R Core Team 2017), to examine if there were any significant factors determining difference in assessment. Specifically we used stepwise multiple linear regression analysis inclusive of these variables: country endemism (scored as binary; endemic or not), temporal difference between assessment years, regional list source, taxonomic issues (scored as binary; yes or no), and country of origin.

Results

Accumulation rates and redundancy

Combining both IUCN-RL and Regional assessments, Fig. 3 indicates evidence-based evaluations of species have risen from 27,291 (29% of which were global post-1997 IUCN-RL assessments) in 2003, to 95,622 species-level assessments in 2015 (21.3% of which are global post-1997 IUCN-RL assessments). This is of course biased by a focus on the digitisation of more recently published Regional Red Lists, but nevertheless represents the best assessment of digitised data so far. 89,810 unique species are covered by those 95,622 species-level assessments. Collectively, of the 350,699 accepted TPL plant species, 25.6% have been subject to at least one threat assessment. Different types of red list assessments have not contributed equally to this accumulation. For the data assembled by the end of 2015 there were five times more plant species assessed solely by Regional Red Lists than solely by IUCN-RL, with 69,443 and 14,555 species respectively, equating to 19.8 and 4.2% respectively. In terms of unique species assessments, the IUCN-RL and Regional Red List data mostly assess different plant species giving a mutually exclusive pattern of coverage. Only 5812 species have been assessed in common between the Regional and IUCN Red Lists, which equates to 6.5% of assessed species, 8.3% of Regional Red List assessments, and 28% of IUCN Red List assessments (Fig. 4a). The observed pattern of non-overlap between the sets is similar when considering just threatened species, with only 7.0% of assessed species in common, evaluated as threatened by both IUCN-RL and Regional Red Lists (Fig. 4b).

The rise in number of unique land plant species threat assessments from 1998 to 2015. Data sourced from the IUCN Red List 2015-4 and Regional Red Lists (https://www.bgci.org/threat_search.php)

Phylogenetic coverage and taxonomic bias

Table 1 and Fig. 5 show that in terms of absolute species numbers of major land plant lineages, RRL consistently assess more species than the IUCN-RL. In other words, RRL have assessed over forty times as many bryophyte species, over nine times as many pteridophytes, and over three times as many angiosperms as the IUCN-RL. Gymnosperms are the exception, for which IUCN-RL has assessed close to twice as many species as the RRL (972 vs 493). The bryophytes have a consistent pattern of disparity in species coverage between RRL and the IUCN-RL. The IUCN-RL has assessed just 0.2% of Bryophyta, 0.8% of Marchantiophyta, and 1% of Anthocerotophyta species, whilst RRL have assessed 10.5, 18.2 and 17.8% of those same lineages (Fig. 5). At the ordinal level, the number of RRL species assessments equal or exceed the number of IUCN-RL species assessments for all but the Cycadales, Pinales, Gnetales, Magnoliales, Dilleniales, Canellales, Berberidopsidales, Metteniusales—the last four of which have relatively few accepted species in them anyway (219, 53, 3, and 3 species respectively). Over all, for the 82 ordinal level groupings showed in Fig. 5a the mean percentage assessment coverage relative to all accepted species in that group by RRL is 32.5%, whereas the IUCN-RL assessments cover 14.9% of species per group (Fig. 5a). The IUCN-RL has more species assessed as threatened for these orders than the RRL: Pandanales, Arecales, Sapindales, Malvales, Aquifoliales. The most striking of these is the Malvales for which IUCN-RL assesses 590 out of 706 assessed species as threatened (83.6% of the assessed species), compared to the RRL for which only 551 out of 1292 assessed species are considered threatened (42.6% of the assessed species) (Fig. 5a, b). Neither IUCN-RL nor the RRL have assessed species from three different angiosperm orders: the extinction risk of Amborellales (one genus, one species), Vahliales (one genus, eight species) and Bruniales (seventeen genera, one hundred species) remains un-quantified.

Far left, the data is related to the cladogram of higher-level relationships reflecting APG IV (APG 2016) and consensus summary of phylogenetic relationships inferred by Ruhfel et al. (2014). The proportion of land plant species that are: a assessed for threat status, b threatened, relative to total known accepted species numbers per order or division according to The Plant List v1.1, the IUCN Red List 2015-4, and Regional Red Lists. The data are stacked so that the proportion of species occurring in both IUCN-RL and RRL are labelled black, the proportion that is solely IUCN-RL is labelled grey, and the proportion that is solely RRL is labelled white

Geographic comparisons between IUCN-RL and RRL coverage

Collectively, IUCN-RL assessed species occur in 249 different countries, dependent territories, and special areas of geographical interest (as defined by the ISO 3166-1 standard), although the distribution of occurrences is highly unequal (see Fig. 6a). The IUCN-RL has a concentration of assessments of plants known to occur in Ecuador (Fig. 6a) with, in order of occurrence frequency, Malaysia, China, India, Mexico, Tanzania, Indonesia, USA and Brazil also containing more than 1000 IUCN-RL assessed species each. In terms of IUCN-RL threatened plant species Ecuador has more than double the number of any other country. Aside from Ecuador, the next most threatened-plant rich countries are Malaysia, Tanzania, China, Madagascar, Brazil, Cameroon and Indonesia which all have over 400 threatened plant species according to IUCN-RL assessments. 204 territories have one or more IUCN-RL threatened plant species growing in them, while 45 territories, mostly small states such as Andorra, Vatican City, Kuwait, Luxembourg, Liechtenstein and Qatar, have no IUCN-RL threatened plant species. Only the very largest territories without IUCN-RL threatened species are visible in Fig. 6a: Iceland, Belgium, the Netherlands, Macedonia, Mongolia and Mauritania.

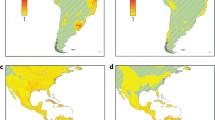

Choropleth maps of equirectangular projection demonstrating the geopolitical distribution of assessed land plant species per country. a All 20,367 assessed IUCN Red List species. b All 75,255 Regional Red List assessed species. c All 89,810 species that have been assessed by the IUCN-RL, a Regional Red List or both. Note we have avoided ‘double-counting’ the same species in the same country if it was assessed by both IUCN-RL and a Regional Red List

Geopolitically, the RRL derive from sources that cover only 87 territories out of the 249 (Fig. 6b). The RRL assessments are predominantly from China (29,899 species assessments from China’s Higher Plants Red List) and the USA (15,845 species assessments from NatureServe). The number of Regional Red List species assessments for China (29,899) and USA (15,845) vastly exceed the total assessments given by IUCN-RL for plants of those countries: just 1580 and 1258 respectively. When it comes to species that are assessed by RRL as threatened there is considerable variation in the proportion of assessed species that are threatened. China for instance has only 11.8% (3526) of its Nationally-Listed species as threatened, whereas the USA considers 39.6% (6268) of its Nationally-Listed species as threatened. Geographically, when combined, IUCN-RL and regional-level assessment complement each other well—the IUCN-RL assessments usefully bolster coverage particularly for Ecuador and South East Asia (Fig. 6c). The distribution of land plant species diversity is well-acknowledged to be unevenly held between countries (Fig. 7a; Pitman and Jørgensen 2002; Giam et al. 2010). European countries have higher levels of coverage, thanks in part to their relatively low native plant species diversity and efforts from regional red list initiatives. By contrast African countries have higher levels of species diversity and lower levels of species that have evidence-based conservation assessments (Fig. 7a, b).

Choropleth maps of equirectangular projection demonstrating; a the estimated number of land plant species that occur in each country based upon data from Pitman and Jørgensen (2002) and updates from Giam et al. (2010), b the percentage of native species that have a threat assessment, per country, given the estimated native plant species numbers from (a)

Difference in like-for-like assessments between IUCN-RL and RRL

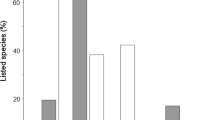

A total of 5812 species were assessed in common by both IUCN-RL and RRL. Once incomparable assessments were removed, we were left with comparable, data-supported assessment pairs for 4524 species. The difference in assessment score for these assessment pairs was calculated and tabulated. The majority of this subset of species are from China or North America which is unsurprising given that most digitally-available RRL assessments are sourced from NatureServe and China’s Higher Plants Red List (Fig. 8c, d); the majority of species are also endemic (58%, Fig. 7e) to just one country. 50% (n = 2301) of IUCN-RL and RRL assessments for the same species agreed upon a threat assessment, indicated by a difference in assessment score of 0. The mean of all Difference in Assessment scores was + 0.25, and the overall distribution has a clearly visible positive skew of 0.20 and is leptokurtic with a kurtosis of 4.81 (Fig. 8a), normally distributed data has skew of 0 and kurtosis of 3. The Anderson–Darling test for normality as calculated with the R package nortest (Gross and Ligges 2015) rejects the null hypothesis that the Difference in Assessment scores are normally distributed (< 2.2e−16). A Chi square test demonstrates that large positive differences (+ 3 to + 7) in assessment are significantly (p value < 0.001) associated with non-endemic species. There are also many large negative differences between assessments (− 3 to − 6), indicating that some species have been assessed as much less threatened by RRL relative to IUCN-RL assessments. Negative assessment differences are proportionally more typically associated with endemic species (Fig. 8e, examples in Table 1) but Chi square testing does not support endemicity as a statistically significant factor (p value = 0.643) for extreme negative assessment differences from − 3 to − 6 considered in isolation to all other factors. Both non-endemic and endemic species display positive skew and high-variance in difference of assessment when considered separately (Fig. 8e). The date of assessment is not controlled for in this analysis but when the data is subset to assessment pairs that are separated by no more than 5 years, the distribution remains similar (Fig. 8f). Some difference in assessment might not be surprising if the assessment pairs are separated in time by a decade or more, as some species can be rediscovered or become more significantly imperiled over these time spans [e.g. Acaena exigua which was positively evidenced as extant in 1997, but subsequently declared extinct in 2000 after the last remaining individual died (Gon et al. 2016)]. But negative assessment differences were not always associated with older RRL assessment and newer IUCN-RL assessment (i.e. potentially explainable as a species becoming genuinely more threatened some time after a RRL assessment). Of the 830 species with negative assessment differences, for 596 (72%) of them, the RRL assessment was published in the same year or was more recent than the publication of the IUCN-RL assessment—indicating discordance that could be examined more closely to determine if the older IUCN-RL assessments are still accurate in their globally-scoped assessment of extinction risk.

Distribution of difference in assessment threat ranking between IUCN-RL and Regionally published assessments; a All 4524 assessment pairs, b where both assessments are published under the current accepted name of the taxon, n = 3943, c NatureServe compared with IUCN-RL assessments, n = 766, d the Chinese Higher Plants Red List (Zhao et al. 2014) compared with IUCN-RL assessments, n = 1277, e Country-endemic species, n = 2623, f where both assessments have been published within 5 years of each other, n = 1867

Modeling difference in assessment

We applied a variety of different models to the available data, with the aim of finding explanatory variables for the observed difference in assessment rank between IUCN-RL and RRL assessments of the same species. Our best model (BIC = 15,729.18) is a simple two-parameter linear model which tries to explains difference in assessment, as a function of: (1) the years elapsed between the assessment pairs, which range from the RRL assessment being 16 years newer [− 16] to the RRL assessment being 30 years older than the most recent global IUCN-RL assessment [+ 30], with a median of 0 and mean of − 0.22; and (2) the number of countries the species is known from, which ranges from 1 to 248, with a median of 1 and a mean of 6.6. These two parameters are both statistically significant factors (p < 0.0001) in this model, but together they only explain less than 6% of the observed difference in assessment (adjusted R2 value = 0.05519). We also ran a three parameter model, modeling taxonomic change as a possible factor in difference in assessment. If one or both of the assessments was published under what we now think of as a synonym, it is scored as ‘1’, if both assessments were published under the current accepted name then it was scored as ‘0’. Adding this third binary parameter into the model gave us a BIC of 15,734.38 which is larger (worse) than the BIC of the two-parameter model. It did not significantly add to the explanatory power of the two parameter model and synonymy as a factor itself was not significant (p = 0.0734).

Discussion

Quantifying evidence-based threat assessments for plant species

We find that of the 350,699 accepted plant species (TPL 2013), 25.6% have been subject to some form of evidence-based threat assessments, of which 9.1% have been designated as threatened by either the IUCN-RL or a RRL. The accumulation of plant species assessments in recent years has been impressive, rising from 36,618 in 2003, to 89,810 species-level assessments in 2015 (Fig. 3). However, this accumulation has been largely driven by RRL, as evidenced by the fact that in 2003, 47% were IUCN-RL assessments, whereas in 2015, only 23% are IUCN-RL assessments (Fig. 3). Indeed, by 2015 there are five times more plant species assessed solely by RRL than solely by IUCN-RL, with 69,443 and 14,555 species respectively, equating to 19.8 and 4.2% of total plant species diversity respectively (Fig. 4). In other words, efforts to assess plant species by RRL have extended our knowledge to 69,443 additional species that have no current IUCN-RL assessments. Moreover, our results demonstrate a considerable proportion of non-overlap between both taxa assessed by the IUCN-RL and RRL (Fig. 3). From the 89,810 species-level assessments, only 5812 have been assessed in common by IUCN-RL and RRL (Fig. 4).

Plants are unarguably under-represented in the IUCN-RL 2015-4 data relative to vertebrates, as evidenced by the fact that only 6% of accepted plant species have had global IUCN-RL assessments. The extent of this under-representation is not a new finding, although our analyses suggest that the situation remains severe 5 years on from the GSPC report, which estimated 10% coverage of plant diversity by IUCN-RL criteria and protocols in 2010. Previous explanations for this under-representation have suggested that, whereas metazoan assessments have been a top-down global process led by specialist groups, global plant assessments have been bottom-up and organized primarily by countries that already have well-developed RRL for plant species (Zamin et al. 2010). Consistent with this explanation, our analyses show that the bulk of plant species assessments do indeed stem from RRL, where the greater attention to plant diversity may reflect the priorities of local conservation practitioners, policy makers and the public. Our analyses certainly support the contention that RRL have emerged as the major contributor to the threat assessment process within the plant kingdom. Furthermore, there is valuable complementarity between the RRL and IUCN-RL datasets, as only 6.4% of species have been assessed in common (Fig. 4), supporting in principle, the integration of these data sources to better assess GSPC targets.

Methodological challenges in normalising RRL and IUCN-RL data

Nonetheless as our methodology highlights, in practice, there are notable procedural challenges in normalizing RRL and the IUCN-RL, in order to compare the data sources, and with a view to their eventual integration. Ultimately, as discussed below, in order to normalize the datasets for comparison, 3.2% of all assessments were discarded in our analyses (Fig. 2). Of the initial 98,844 assessments of plant species, there were also problems arising from assessments based on inadequately described taxa, which resulted in 129 discarded assessments. Aside from ‘species novum’ taxa there were also assessments for nomina nuda such as ‘Rughidia milleri’ and ‘Oreofraga morrisiana’, neither of which have ever been published to our knowledge, or that of The Plant List (TPL 2013). Finally, changes in taxonomy since the time of assessment, together with on-going taxonomic uncertainty and taxonomic disagreement clearly affect a substantial number of published assessments. A total of 2131 assessments were discarded because, according to TPL, they were no longer considered to be a species-level taxon, or because they were considered to be synonymous with another assessed taxon. Again with the bulk of this discrepancy coming from the RRL, with 1837 examples of these. In total, issues with systematics caused us to discard 388 (1.8%) of IUCN-RL assessments, and 2834 (3.6%) of the published RRL assessments (Fig. 2). Evidently the degree of discrepancy found within RRL data sources, relative to TPL, appears to be considerably higher than the IUCN-RL, owing in part to the IUCN-RL usage of TPL since its release in 2010.

Gaps in taxonomic and phylogenetic coverage

Bias in taxonomic coverage across conservation assessments is a well-established phenomenon, and plants have previously been identified as under-represented in conservation science and policy. Our analyses reveal similar biases in coverage within assessments of plant species at the level of the four major groupings of land plants, angiosperms, gymnosperms, pteridophytes, and bryophytes. Considering all assessments, both RRL and IUCN, coverage per group is; 80,942 species or 26.6% of angiosperms, 988 species or 89.3% of gymnosperms, 3677 species or 34.4% of pteridophytes, and 4303 species or 12.2% of bryophytes. Although by raw count there are vastly more angiosperm assessments, in terms of percentage coverage, due to the high species diversity of angiosperms the overall percentage coverage of the group is low (26.6%) relative to gymnosperms and pteridophytes. The coverage of gymnosperms is exceptionally good, as there is an active group (Conifer Specialist Group) working on the conservation assessments of these taxa and there are relatively few species to assess. As might be expected, given smaller research communities and more limited pools of taxonomic expertise, the number of assessments for bryophytes is the lowest both as an absolute number and as a proportion.

Perhaps more instructive, is the comparison of the taxonomic coverage between the IUCN-RL and RRL data sets. The IUCN-RL has better coverage of gymnosperms, but much poorer coverage of angiosperms. Relative to RRL, IUCN-RL coverage of bryophyte species is exceptionally poor, where just 102/34,556 species (0.3%) of accepted bryophyte species have an IUCN-RL assessment. With over 4000 bryophyte assessments, the RRL are providing key coverage for the early diverging land plant lineages, in absence of a coherent international program. Although a predictable deficiency, the lack of coverage of bryophyte species fails to recognize that bryophytes form dominant communities across a significant fraction of the Earth’s surface. Bryophytes typically occur in tundra, boreal, and peatland ecosystems (Lindo and Gonzalez 2010), where they provide a habitat to a highly diverse microbiota (Kauserud et al. 2008), and play a central role in the detrital networks and nutrient cycling in these ecosystems (Turetsky 2003).

Higher numbers of assessments in RRL datasets versus IUCN-RL hold across lower taxonomic hierarchies. At the ordinal level, mean percentage coverage relative to all accepted species by RRL is 32.5% per order, whereas the IUCN-RL assessments cover an average of 14.9% of species per order (Fig. 5). Consistent with these mean values, the same data mapped across a consensus topology of the land plants in Fig. 5, show that RRL have more even and proportional sampling across the major orders of land plants. RRL species assessments equal or exceed the number of IUCN-RL species assessments for all but the Cycadales, Pinales, Gnetales, Magnoliales, Dilleniales, Canellales, Berberidopsidales, and Mettenusiales (Fig. 5). That the IUCN-RL assesses far more species in the order Magnoliales is due to active specialist groups focusing on their assessments, such as the publication of the Red List of Magnoliaceae (Rivers et al. 2015), evidence of the success of focused taxonomic intervention of global assessment in key groups.

Overall, the results clearly suggest that in terms of enriching taxonomic coverage, much could be gained from merging RRL and the IUCN-RL into one single pool of plant species threat assessments as suggested by Zamin et al. (2010). This has now been turned into reality in the publication by BGCI of a global database ThreatSearch (www.bgci.org/threat_search.php), which has assembled regional and global assessments of plants in a single portal.

Geographic coverage

As with taxonomic bias, the geographical bias in conservation activity, including biodiversity data collection and publication has been well documented (Reddy and Dávalos 2003; Boakes et al. 2010; Trimble and van Aarde 2012; Oliveira et al. 2016). In general, despite high species diversity, tropical areas are understudied and underrepresented in biodiversity data (Kier et al. 2005; Collen et al. 2008). Consistent with this observation, previous studies have highlighted similarly large gaps in evidence-based conservation assessments across all continents that transect the tropics: Africa, Asia, Australasia and South America (Collen et al. 2008; Zamin et al. 2010). The RRL for Ecuador (León-Yánez et al. 2011), Malaysia (Chua et al. 2010) and the Philippines (Fernando et al. 2008) are notable exceptions to this tropical deficit. Limited availability of financial resources, using Gross Domestic Product as an indicator, is also strongly correlated with limited biodiversity data, again contributing to gaps in conservation assessments across these same continents (Zamin et al. 2010). In addition, specifically with respect to RRL coverage, previous studies have identified substantial gaps in data from West Africa, Central Africa, Australasia, and the Caribbean (Zamin et al. 2010).

Our analyses of plant focused conservation assessments are consistent with these previous studies, as depicted cartographically, conservation assessment coverage does not correlate well with the natural geographic distribution of plant species diversity (Fig. 7). The average percentage of total plant biodiversity assessed across Africa (including the Middle East), Asia (including Oceania and the Pacific Islands), and South America is 13.3, 21.8, and 7.6% respectively, compared to Europe (including Central Asia) and North America (including the Caribbean and Central America) at 27.7 and 16.0% respectively (Fig. 7). However there are notable differences in the extent of geographic coverage between IUCN and RRL assessments of plant species, with IUCN having at least one species in 249/249 countries while the RRL cover 89/249 countries (Fig. 6). There are also clear differences in geographic focus. The RRL have a disproportionate bias towards assessments of plants in the USA and China, but are still notably absent from West Africa, Central Africa, and the Middle East (Fig. 6). The IUCN-RL thus often offers the only conservation assessments across large tracts of continent for which RRL are apparently absent (Fig. 6).

Clearly the globally operating IUCN-RL is providing key biodiversity data in areas where resources are limiting the production of regional red lists. Simply put, with respect to plant species assessments, IUCN-RL often usefully complements the geographic gaps in RRL coverage, and vice versa.

Threat assessment between and among RRL and IUCN-RL datasets

Taxonomic and geographic gaps can undermine the efficacy and utility of evidence-based conservation assessments for biological conservation. The absence of certain species from the assessment process also has the potential to lead species to extinction, and discrepancies between different sources can undermine the credibility of both global and regional red lists. Discrepancies are commonly ascribed to a number of causes, including: regional inequalities in the availability of financial resources and expertise, regional differences in the value attached to different units and types of biodiversity, politicization of bureaucracy associated with regional and global assessments, the application of different protocols, the misapplication of common protocols, taxonomic uncertainty and disagreement, and differences in abundance of individual species at different geographical scales (Collen et al. 2008; Kozlowski 2008; Brito et al. 2010; Zamin et al. 2010).

Taking the RRL and IUCN-RL dataset for plant species as a whole, there are clearly considerable differences in the proportion of species considered as imperiled: 59% of IUCN-RL assessed taxa are considered threatened compared with only 33% in digitally-available RRL assessments. We explicitly recognize that due to the biases operating within these compiled datasets, this estimate cannot be meaningfully compared with, or substituted for, the recent figures obtained by the relatively unbiased Sampled Red List Index for Plants, which estimates that more than 20% of plant species are threatened with extinction. It is likely that the IUCN-RL overestimates the overall extinction of species mainly because over many years most effort has been focused on assessing the species that scientists expect to be threatened, due both to the limited resources available for assessments and to a natural tendency to select species considered to be most in need of assessment.

The 4524 species that have been assessed by both IUCN-RL and RRL with adequate data (i.e. not data deficient), give us a unique window on the comparability of IUCN-RL and RRL assessments of plant species. We observe (Fig. 8a) that 49.1% of IUCN-RL and RRL threat assessments do not agree on the exact category of extinction risk that has been assigned. That discord is just as common as agreement between IUCN-RL and RRL assessments has been noted before in the context of fish (Helfman 2013), but not plants. We find that 15.7% (709) of our sample is composed of species that are not recognized as threatened (Least Concern or Near Threatened) by the IUCN-RL, yet considered threatened or extinct per RRL. In this regard our results differ strongly from that of Brito et al. (2010) who analysed just four RRL but across all taxa, not just plants. Brito et al. (2010) found that only 2% of species assessed in common were not considered threatened by IUCN-RL, but were considered threatened on an RRL. In the same analysis, Brito et al. (2010) estimated that 14% of plants were listed as globally threatened but not nationally threatened, whereas our analysis finds that 8.3% (377) of plant species are considered globally threatened by IUCN-RL, but not considered threatened by RRL assessment. But here we analyze results in a more fine-grained way than a simple binary comparison of threatened and non-threatened, and consequently expose a greater range of discord than revealed by Brito et al. (2010).

The overall level of agreement (0 difference in assessment rank) is particularly driven by agreement on assessment of species that are Least Concern; such assessments make-up 42% (962/2301) of all the agreement assessment pairs. A two-tailed Fisher’s exact test (p < 0.0001) demonstrates then when the IUCN-RL assessment is Least Concern, the RRL assessment has a significant association with this assessment. So, for Least Concern assessments, agreement between IUCN-RL and RRL assessments is significantly better than random. This is unsurprising—it is relatively easier to agree on species which are not at risk of extinction. But even hidden within the assignment of ‘Threatened’ statuses there is disagreement, namely that 19.3% or 873 of our assessment pairs disagree in terms of what exact category of threat is assigned to particular species e.g.VU versus EN, EN versus CR, or VU versus CR (similar to that shown by Rivers et al. 2014). Our data shows a positive skew towards RRL assigning a greater extinction risk to species, than the corresponding IUCN-RL assessment (Fig. 8a).

Generally this positive skew fits null expectation as, due to reasons of geographic scale, the most common explanation is that a species is much more likely to become regionally extinct than to become globally extinct. However there are two more troubling aspects to these analyses of level of agreement. Firstly, when just endemic species are considered, the overall pattern remains largely similar with a similar positive skew (Fig. 8e). More than half (1314/2623, 50.1%) of the endemics-only data present some form of assessment disagreement albeit typically only one rank of threat status up or down (Fig. 8e). Procedural factors and differences in assessment protocol may therefore be a major contributor, perhaps including a national bias towards overvaluing culturally important plants, political interference to elevate or reduce threat status, application of different assessment protocols, misapplication or alteration of IUCN protocols, and taxonomic disagreement. Second, although the overall skew is towards the positive, there are a large number of disagreements, which fall to the negative i.e. the RRL assign a lower risk of extinction to species than the corresponding IUCN-RL assessment. But it is logically impossible for a species to be Near Threatened or Vulnerable nationally and Extinct globally. These ‘negative’ tail disagreements are the more dangerous in terms of species conservation, because most species conservation efforts are delivered locally or regionally, and so an underestimation of extinction risk by RRL may undermine these conservation efforts. However here, our comparisons and analyses provide a useful tool for targeting interventions, as a way of prioritizing species re-evaluation for which one of the assessments, either Regional or IUCN-RL, might be in need of updating an accurate.

Observed differences in assessment have different causes

Although just over 50% of the taxa have directly equivalent assessments between IUCN-RL and RRL, the remaining half of taxa have assessments that are different by one rank or more. The causes of difference in each case are not easy to pinpoint and cannot generally be identified or predicted by statistical modeling with the data we have available—they appear to require explanation and examination on a case-by-case basis. However, we can point to some general reasons, with examples from species assessments that are among those included in this study.

-

1.

Likely to form the bulk of the differences between IUCN-RL and RRL is the simple fact that regional extinction is inherently more likely than global extinction. In the case of the 3 species which have the maximal (7) difference in assessment possible, it is unsurprising to find that the countries lie at the extremities of the species range (Brito et al. 2010). For assessments of Cyperus glaber (1), Ranunculus ophioglossifolium (2), and Ulex europaeus (3) the IUCN-RL has them all as Least Concern, whilst at the regional level they have all been assessed as ‘Extinct’ (1) by a Croatian NL, (2) by an Israeli NL, and (3) by a Norwegian NL. For these species it is clear that they are geographically widespread species and the difference in assessment merely reflects regional extinction at the edge of the native species range, rather than global extinction.

-

2.

Real change in extinction risk occurring in the time elapsed between two assessments. In our pool of data we have some assessment pairs in which one assessment may be published up to 30 years after the other assessment for the same species (incidentally in all three of these maximal instances the assessment stays the same [Least Concern] between the two assessments). In the intervening time between assessments it is conceivable that the extinction risk of a species may genuinely change rank and thus difference in assessment could be purely down to just time elapsed between assessments. The statistical modeling demonstrates that time elapsed is only weakly predictive of difference in assessment. To add a complication, time elapsed also increases the likelihood of the taxon circumscription being revised, so time elapsed is co-correlated and not independent of issues owing to taxonomic change. Examination of assessment pairs that are separated in publication date by 5 years of less (e.g. Fig. 8f), show a similar trend to the overall data (Fig. 8a).

-

3.

Differences owing to changes in our understanding of the circumscription of taxa. In 1998, a global IUCN-RL assessment for Chrysophyllum claraense was published assessing it as Critically Endangered. The Plant List v1.1 treats Chrysophyllum claraense as a synonym of Chrysophyllum oliviforme What was assessed in 1998 under C. claraense by IUCN-RL is no longer considered a discrete separate taxon worthy of its own species-rank name. That taxon is considered a synonym of Chrysophyllum oliviforme and this species is regionally assessed as Least Concern by the Cuba Red List (Berazain Iturralde et al. 2005). As our analyses show, changes to the circumscription of taxa that affect conservation status are relatively rare (Fig. 8a, b). Most synonyms are orthographic or nomenclatural synonyms that do not change the circumscription of the taxon, unlike taxonomic synonyms which do change taxon circumscription (sensu Remsen 2016).

-

4.

Possible local rediscoveries, reflected in local assessments, that have not yet filtered back to global assessment processes. There are a noticeably large number of taxa (830) for which the RRL assessment is much less threatened than the global IUCN-RL assessment. Of particular interest, four species, namely Adiantum lianxianense, Melicope haleakalae, Chrysophyllum januariense, and Ormosia howii have regional assessments that indicate they are extant and are either Near Threatened or Vulnerable. However, the IUCN-RL has assessed all four species as globally extinct—a difference of unarguable significance. Three of those local assessments are noticeably more recent that their IUCN-RL counterparts which suggests they may have been rediscovered in the wild after the IUCN-RL ‘Extinct’ assessments were made. However, for Melicope haleakalae the publication date of NatureServe’s ‘G2’ assessment and IUCN-RL’s ‘Extinct’ assessment is the same: 1998, suggesting a possible taxonomic error. We note that Melicope haleakalae is listed as a ‘Species of Concern’ but not one that is Extinct (Wood et al. 2016), which suggests that the IUCN-RL assessment is perhaps too pessimistic. These sorts of disagreements need urgent re-evaluation to ensure appropriate conservation action is taken.

Concluding perspectives

We have found that RRL assessments are increasing at a rate much faster than global IUCN-RL assessments of plant species. The collective contribution of RRL is invaluable in terms of broadening the scope of threat assessments and providing much needed depth in certain taxonomic areas such as the bryophytes. The Regional and IUCN assessments are largely complementary in terms of taxonomic and geographic coverage, and there would be much to be gained by combining the work of IUCN-RL and RRL to support subsequent GSPC targets on the in situ and ex situ conservation of plants, which has now happened with the recent release of BGCI ThreatSearch (https://www.bgci.org/threat_search.php). However, comparisons of regional-level and global IUCN-RL assessments of the same species reveal interesting discrepancies in the exact level of extinction risk between assessments, something that could be usefully resolved in specific cases with further investigation. As expected, our data show that RRL tend to report higher risk of extinction relative to global assessments, but more concerning are the great many RRL assessments that report lower extinction risk for species than the global assessments Our analyses serve to highlight these instances and to direct specific efforts for re-assessment. In extreme cases this could lead to official ‘rediscovery’ of species that were previously considered extinct by global assessment groups, but found to be extant by regional assessments. These discrepancies that we highlight, together with the taxonomic and geographic gaps, should help guide focused intervention, ensuring both breadth and depth in the threat assessment coverage of all plant species.

References

Ah-Peng C, Bardat J, Pócs T, Söderström L, Staménoff P, Strasberg D (2012) Red List of liverworts and hornworts for Réunion (Mascarene archipelago). Phytotaxa 68(1):1–23

APG (2016) An update of the Angiosperm Phylogeny Group classification for the orders and families of flowering plants: APG IV. Bot J Linn Soc 181(1):1–20. https://doi.org/10.1111/boj.12385

Ashton P (1998) Hopea shingkeng. The IUCN Red List of threatened species 1998: e.T33469A9786213. https://doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.1998.RLTS.T33469A9786213.en

Balmford A et al (2005) Ecology: the convention on biological diversity’s 2010 target. Science 307:212–213

Beck J, Ballesteros-Mejia L, Nagel P, Kitching IJ (2013) Online solutions and the ‘Wallacean shortfall’: what does GBIF contribute to our knowledge of species’ ranges? Divers Distrib 19(8):1043–1050. https://doi.org/10.1111/ddi.12083

Beck J, Böller M, Erhardt A, Schwanghart W (2014) Spatial bias in the GBIF database and its effect on modeling species’ geographic distributions. Ecol Inf 19:10–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoinf.2013.11.002

Berazain Iturralde R, Areces Berazain F, Lazcano Lara JC, Gonzalez Torres LR. 2005. Lista roja de la flora vascular cubana. Jardin Botanico Atlantico de Gijon

Bibiloni G, Mus M (2006) Arenaria bolosii. The IUCN Red List of threatened species 2006:e.T61633A12529922. https://doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2006.RLTS.T61633A12529922.en

Bilz M, Kell SP, Maxted N, Lansdown RV (2011) European red list of vascular plants. Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg

Boakes EH, McGowan PJK, Fuller RA, Chang-qing D, Clark NE, O’Connor K, Mace GM (2010) Distorted views of biodiversity: spatial and temporal bias in species occurrence data. PLOS Biol 8:e1000385+

Brito D, Ambal RG, Brooks T, Silva ND, Foster M, Hao W, Hilton-Taylor C, Paglia A, Rodriguez JP, Rodríguez JV (2010) How similar are national red lists and the IUCN Red List? Biol Conserv 143:1154–1158

Brummitt NA et al (2015) Green plants in the red: a baseline global assessment for the IUCN Sampled Red List Index for plants. PLoS ONE 10:e0135152–e0135152

Butchart SHM et al (2010) Global biodiversity: indicators of recent declines. Science 328:1164–1168

Cayuela L, Granzow-de la Cerda I, Albuquerque FS, Golicher DJ (2012) Taxonstand: an R package for species names standardisation in vegetation databases. Methods Ecol Evol 3(6):1078–1083. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2041-210x.2012.00232.x

CBD (2014) Progress in achieving the targets of the Global Strategy for Plant Conservation 2011–2020 UNEP/CBD/SBSTTA/18/3. https://www.cbd.int/doc/meetings/sbstta/sbstta-18/official/sbstta-18-03-en.pdf

Chua LSL, Suhaida M, Hamidah M, Saw LG (2010) Malaysia plant red list: Peninsular Malaysian Dipterocarpaceae. Forest Research Institute Malaysia (FRIM), Malaysia, pp 210

Collen B, Ram M, Zamin T, McRae L (2008) The tropical biodiversity data gap: addressing disparity in global monitoring. Trop Conserv Sci 1:75–88

Collen B, Dulvy NK, Gaston KJ, Gärdenfors U, Keith DA, Punt AE, Regan HM, Böhm M, Hedges S, Seddon M, Butchart SHM, Hilton-Taylor C, Hoffmann M, Bachman SP, Akçakaya HR (2016) Clarifying misconceptions of extinction risk assessment with the IUCN red list. Biol Lett 12:20150843

Cortini Pedrotti C, Aleffi M (2011) Lista rossa delle Briofite del Trentino. Studi Trentini di Scienze Naturali. Acta Biol 88:5–27

Dines TD, Jones RA, Leach SJ, McKean DR, Pearman DA, Preston CD, Rumsey FJ, Taylor I (2005) The vascular plant Red Data List for Great Britain. In: Cheffings CM, Farrell L (eds.) Species status, vol 7. Joint Nature Conservation Committee, Peterborough, pp 1–116

Eastwood A, Lazkov G, Newton A (2009) The Red List of trees of Central Asia. Fauna & Flora International, Cambridge, pp 1–31

Fernando ES, Co LL, Lagunzad DA, Gruezo WS, Barcelona JF, Madulid DA, Lapis AB, Texon GI, Manila AC, Zamora PM (2008) Threatened plants of the Philippines: a preliminary assessment. Asian Int J Life Sci 3:1–52

Gärdenfors U, Hilton-Taylor C, Mace GM, Rodriguez JP (2001) The application of IUCN Red List criteria at regional levels. Conserv Biol 15:1206–1212

Giam X, Bradshaw CJA, Tan HTW, Sodhi NS (2010) Future habitat loss and the conservation of plant biodiversity. Biol Conserv 143:1594–1602

Gon SM, Keir M, Kwon J, Weisenberger L, Sporck-Koehler M, Chau M (2016) Acaena exigua. The IUCN Red List of threatened species 2016: e.T44072A101442020

González-Espinosa M, Meave JA, Lorea-Hernández FG, Ibarra-Manrquez G, Newton AC (2011) The Red List of Mexican cloud forest trees. Flora & Fauna International, Cambridge, pp 1–149

Gross J, Ligges U (2015) Nortest: tests for normality. R package version 1.0-4. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=nortest

Harris JBC, Reid JL, Scheffers BR, Wanger TC, Sodhi NS, Fordham DA, Brook BW (2012) Conserving imperiled species: a comparison of the IUCN Red List and U.S. Endangered Species Act. Conserv Lett 5:64–72. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1755-263X.2011.00205.x

Helfman GS (2013) National “versus” global red lists of imperiled fishes: why the discord? Environ Biol Fishes 96(10–11):1159–1168. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10641-011-9843-x

Hequet V (2010) Eugenia sp. nov. ‘lepredourii’. The IUCN Red List of threatened species 2010: e.T177842A7467970. https://doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2010-4.RLTS.T177842A7467970.en

Kauserud H, Mathiesen C, Ohlson M (2008) High diversity of fungi associated with living parts of boreal forest bryophytes. Botany 86:1326–1333

Kier G, Mutke J, Dinerstein E, Ricketts TH, Küper W, Kreft H, Barthlott W (2005) Global patterns of plant diversity and floristic knowledge. J Biogeogr 32:1107–1116

Kozlowski G (2008) Is the global conservation status assessment of a threatened taxon a utopia? Biodivers Conserv 17:445–448

León-Yánez S, Valencia R, Pitman N, Endara L, Ulloa C, Navarrete H (2011) Libro Rojo de Las Plantas Endémicas Del Ecuador, Segunda Edicion. Herbario QCA, Pontificia Universidad Católica del Ecuador, Quito, Ecuador

Lindo Z, Gonzalez A (2010) The Bryosphere: an integral and influential component of the Earth’s biosphere. Ecosystems 13:612–627

Mesibov R (2013) A specialist’s audit of aggregated occurrence records. ZooKeys 293:1–18. https://doi.org/10.3897/zookeys.293.5111

Miller A (2004) Asparagus sp. nov. A. The IUCN Red List of threatened species 2004: e.T44902A10957671. https://doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2004.RLTS.T44902A10957671.en

Morais AR, Braga RT, Bastos RP, Brito D (2012) A comparative analysis of global, national, and state red lists for threatened amphibians in Brazil. Biodivers Conserv 21:2633–2640

Moser D, Ellmauer T, Evans D, Zulka KP, Adam M, Dullinger S, Essl F (2016) Weak agreement between the species conservation status assessments of the european habitats directive and red lists. Biol Conserv 198:1–8

Natcheva R, Ganeva A, Spiridonov G (2006) Red List of the Bryophytes in Bulgaria. Phytol Balc 12(1):55–62

NatureServe (2012) NatureServe conservation status assessments: factors for evaluating species and ecosystem risk. http://www.natureserve.org/sites/default/files/publications/files/natureserveconservationstatusfactors_apr12_1.pdf

Oliveira U et al (2016) The strong influence of collection bias on biodiversity knowledge shortfalls of Brazilian terrestrial biodiversity. Divers Distrib. https://doi.org/10.1111/ddi.12489

Otegui J, Ariño AH, Encinas MA, Pando F (2013) Assessing the primary data hosted by the Spanish node of the global biodiversity information facility (GBIF). PLoS ONE. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0055144

Pannell CM (1998a) Aglaia cinnamomea. The IUCN Red List of threatened species 1998: e.T37558A10064069. https://doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.1998.RLTS.T37558A10064069.en

Pannell CM (1998b) Aglaia elliptica. The IUCN Red List of threatened species 1998: e.T33726A9805994. http://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.1998.RLTS.T33726A9805994.en

Paton A, Lughadha EN (2011) The irresistible target meets the unachievable objective: what have 8 years of GSPC implementation taught us about target setting and achievable objectives? Bot J Linn Soc 166(3):250–260. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1095-8339.2011.01155.x

Pennell MW, FitzJohn RG, Cornwell WK (2016) A simple approach for maximizing the overlap of phylogenetic and comparative data. Methods Ecol Evol 7(6):751–758. https://doi.org/10.1111/2041-210x.12517

Pitman NC, Jørgensen PM (2002) Estimating the size of the world’s threatened flora. Science 298(5595):989

Possingham HP, Andelman SJ, Burgman MA, Medellın RA, Master LL, Keith DA (2002) Limits to the use of threatened species lists. Trends Ecol Evol 17:503–507

R Core Team (2017) R: a language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria

Ram K (2013) Git can facilitate greater reproducibility and increased transparency in science. Source Code Biol Med. https://doi.org/10.1186/1751-0473-8-7

Reddy S, Dávalos LM (2003) Geographical sampling bias and its implications for conservation priorities in Africa. J Biogeogr 30:1719–1727

Remsen D (2016) The use and limits of scientific names in biological informatics. ZooKeys 550:207–223

Rivers M, Brummitt NA, Lughadha EN, Meagher TR (2014) Do species conservation assessments capture genetic diversity? Global Ecol Conserv 2:81–87

Rivers M, Shaw K, Beech E, Jones M (2015) Conserving the world’s most threatened trees: a global survey of ex situ collections. BGCI, Richmond

Rodriguez JP (2008) National Red Lists: the largest global market for IUCN Red List Categories and Criteria. Endanger Species Res 6:193–198

Ruhfel BR, Gitzendanner MA, Soltis PS, Soltis DE, Burleigh J (2014) From algae to angiosperms-inferring the phylogeny of green plants (Viridiplantae) from 360 plastid genomes. BMC Evolut Biol. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2148-14-23

Tefnu S, Goia I (2012) Checklist and Red List of Bryophytes of Romania. Nova Hedwigia 95:59–104

Tittensor DP et al (2014) A mid-term analysis of progress toward international biodiversity targets. Science 346:241–244

TPL (2013) The Plant List, Version 1.1. Published on the Internet; http://www.theplantlist.org/

Trimble MJ, van Aarde RJ (2012) Geographical and taxonomic biases in research on biodiversity in human-modified landscapes. Ecosphere 3:1–16

Turetsky MR (2003) The role of bryophytes in carbon and nitrogen cycling. Bryologist 106:395–409

Walpole M et al (2009) Ecology. Tracking progress toward the 2010 biodiversity target and beyond. Science 325:1503–1504

Witkowski ZJ, Król W, Solarz W (eds) (2003) Carpathian list of endangered species. WWF and Institute of Nature Conservation, Polish Academy of Sciences, Krakow

Wood KR, Appelhans MS, Wagner WL (2016) Melicope oppenheimeri, section Pelea (Rutaceae), a new species from West Maui, Hawaiian islands: with notes on its ecology, conservation, and phylogenetic placement. PhytoKeys 69:51–64

Wyse Jackson P, Kennedy K (2009) The global strategy for plant conservation: a challenge and opportunity for the international community. Trends Plant Sci 14:578–580

Yesson C et al (2007) How global is the global biodiversity information facility? PLoS ONE. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0001124

Zamin TJ, Baillie JEM, Miller RM, Rodriguez JP, Ardid A, Collen B (2010) National red listing beyond the 2010 target. Conserv Biol 24:1012–1020. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1523-1739.2010.01492.x

Zhao LN, Qin HN, Liu HY (2014) IUCN Red List and China Higher Plant Red List. In: Ma KP (ed) Advances in biodiversity conservation and research in China X. China Meteorological Press, Beijing, pp 111–117

Funding

Funding was provided by Natural Environment Research Council (Grant No. RG69516).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Communicated by Daniel Sanchez Mata.

This article belongs to the Topical Collection: Biodiversity legal instruments and regulations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Mounce, R., Rivers, M., Sharrock, S. et al. Comparing and contrasting threat assessments of plant species at the global and sub-global level. Biodivers Conserv 27, 907–930 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10531-017-1472-z

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10531-017-1472-z