Abstract

Floodplain ecosystems are biodiversity hotspots and supply multiple ecosystem services. At the same time they are often prone to human pressures that increasingly impact their intactness. Multifunctional floodplain management can be defined as a management approach aimed at a balanced supply of multiple ecosystem services that serve the needs of the local residents, but also those of off-site populations that are directly or indirectly impacted by floodplain management and policies. Multifunctional floodplain management has been recently proposed as a key concept to reconcile biodiversity and ecosystem services with the various human pressures and their driving forces. In this paper we present biophysics and management history of floodplains and review recent multifunctional management approaches and evidence for their biodiversity effects for the six European countries Ireland, the Netherlands, Germany, Slovakia, Hungary and the Ukraine. Multifunctional use of floodplains is an increasingly important strategy in some countries, for instance in the Netherlands and Hungary, and management of floodplains goes hand in hand with sustainable economic activities resulting in flood safety and biodiversity conservation. As a result, biodiversity is increasing in some of the areas where multifunctional floodplain management approaches are implemented. We conclude that for efficient use of management resources and ecosystem services, consensual solutions need to be realized and biodiversity needs to be mainstreamed into management activities to maximize ecosystem service provision and potential human benefits. Multifunctionality is more successful where a broad range of stakeholders with diverse expertise and interests are involved in all stages of planning and implementation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Under natural conditions, biodiversity hotspots are often found near rivers, their banks and floodplains, as these areas represent habitats with high levels of structural and functional dynamics, primarily induced by downstream flow (Ward et al. 1999). Floodplains are often characterized by a mosaic of habitats differing in age, humidity, sediment properties, productivity, and diversity, abundance, composition and succession state of biota (Geilen et al. 2004). This habitat mosaic is inhabited by a multiplicity of generalist and specialist species, both terrestrial and aquatic, which often depend on the relative habitat quality and on proximity and functional connectivity of various habitat patches (Romanowski et al. 2005; Scholz et al. 2012). Historically rivers and their floodplains have served for multiple human uses including as major axes of migration, settlement, agriculture, forestry, fishery, industrial development and trade. This is not surprising, since monofunctional management of areas with such high potential for providing goods and services would be potentially inefficient (Secchi et al. 2012). Most floodplain areas have meanwhile been hydrologically disconnected from the river by the construction of dykes, and are currently often dominated by intense human use, such as agriculture, settlements or traffic routes (Hein et al. 2016) and Europe is the continent that is most affected by such activities (Nilsson et al. 2005). Habitat conditions in the remaining active floodplain areas have often substantially been altered by human impacts, such as river training, river damming, floodplain disconnection, aggradation, pollution by fertilizers and chemical contaminants, introduction of invasive species, or by intense forestry (e.g. Nijland and Cals 2001; Leyer 2005; Rinaldi et al. 2013). Thus, most floodplains in Europe are degraded, especially due to reduced hydromorphological dynamics. This has led, among other things, to a decrease of dynamic habitat types which are an essential part of floodplains (Klimo et al. 2008). The resulting reduced rate of habitat turnover is accompanied by a decrease in the richness particularly of specialist and sensitive species that depend on the availability of newly formed habitat and sediment accumulations created by the natural patterns of high and low discharge levels (Poff et al. 1997).

Historical interventions in the functions and structures of European rivers and floodplains also enhanced the risk of devastating flood events (e.g. Somlyódi 2011). In the last decades, major floods occurred in Central Europe (1997, 1998, 1999, 2000, 2002, 2006, 2013), in the UK (2002, 2004, 2005, 2007, 2009, 2010, 2012), and in Ireland (2009, 2012, 2015). A political answer of the EU to the first events was the launch of a Flood Directive (EC 2007). Furthermore, these major floods have triggered additional interest in floodplain areas, partly aimed at the increase and optimization of flood retention capacities. In cases of non-technical measures like dyke relocations, the establishment of flood retention areas has been shown, for instance, to provide a cost-effective protection against flood damage with significant ecological co-benefits (Grossmann et al. 2010).

This interest from governmental flood management administrations has opened new options and innovative co-financing opportunities to re-establish hydrological dynamics in floodplain areas that have previously been partially or fully disconnected. Within such floodplain management projects, any physical alterations and new management regimes should be agreed on by all stakeholders of the respective areas, in order to minimize potential conflicts of development aims. Thus, there is a need to establish and implement multifunctional approaches in floodplain management instead of sectoral narrow-focused actions, which may present great opportunities to restore degraded floodplain areas (Secchi et al. 2012; Schindler et al. 2014). However, in many places major target conflicts have not been resolved, land use pressures being a predominant issue in this context. Today no systematic approach exists to reconcile the various competing management goals.

Green Infrastructure has been increasingly proposed as a multifunctional solution for halting loss and fragmentation of habitats, and thus biodiversity, and for maintaining and restoring ecosystems and their services (EC 2011; EEA 2015). Green Infrastructure was defined in this context as “an interconnected network of green space that conserves natural ecosystem values and functions and provides associated benefits to human populations” (Benedict and McMahon 2002). Multifunctionality is a key feature of Green Infrastructure and commonly related to the functions of ecosystems and to the ecosystem services provided to human populations (MA 2005; Weber et al. 2006). Multifunctional floodplain management (MFM) can be defined as a management approach aimed at a balanced supply of ecosystem services, serving the needs of local and remote residents, who are directly or indirectly impacted by floodplain policies (cf. Secchi et al. 2012). Existing trade-offs imply in this context cut-backs in some provisioning services currently dominating many floodplain landscapes (Schindler et al. 2014).

In this study we applied the Driver-Pressure-State-Impact-Response (DPSIR) framework (EEA 2007) for selected temperate European floodplains. The aim of this study was to review status of biodiversity in floodplains, pressures and their impacts as well as multifunctional floodplain management as response and evidence for its effects on biodiversity. This study was conducted in the frame of the trial assessments for testing functionality and performance of the science-policy interface ‘BiodiversityKnowledge’ (Nesshöver et al. 2016; Schindler et al. 2016). Conducting this assessment also delivered some methodological insights for ‘BiodiversityKnowledge’ that will be highlighted in the discussion section (see also Schindler et al. 2016).

Methods

The research question ‘Impact of multifunctional floodplain management on biodiversity and ecosystem services’ was tackled by several methodological approaches in the frame of the trial assessment ‘conservation case’ for testing functionality and performance of the science-policy interface BiodiversityKnowledge, (Schindler et al. 2013a, b, 2014, 2016). The focus of the trial assessment was on temperate Europe, because floodplains under other climatic regimes, such as boreal or Mediterranean, have basic differences in their floodplain ecology and dynamics. The trial assessment strongly relied on a group of experts that was compiled by contacting knowledge hubs and individual knowledge holders (Schindler et al. 2013b) and covered multidisciplinary expertise on floodplains and had a broad geographic coverage (Schindler et al. 2014 supplementary material; 2016).

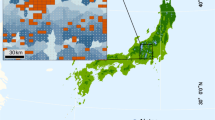

This assessment dealt with the six countries Ireland, the Netherlands, Germany, Slovakia, Hungary and the Ukraine covering temperate European floodplains along a West-East gradient of approximately 4000 km (Fig. 1). The situation in each country was reviewed by one or more floodplain experts using their personal expertise in their resident country complemented by a review of the national literature. MFM projects were selected according to their relevance for the study aims as judged by the national experts. To reach consistency among contributions for each country, we understand floodplains for this study as ‘low-relief earth surfaces composed of fluvial deposits that are frequently flooded (active floodplains) or formerly flooded (morphological floodplains) and are an integral part of catchments‘(Tockner et al. 2010). Although the balanced provision of many functions and services should ideally be aimed for in MFM (Schindler et al. 2014; Plieninger et al. 2015), we further agreed to potentially consider bifunctional management strategies and projects, a minimalistic version of multifunctionality aiming at conservation or restoration of two functions only. We further agreed on applying the DPSIR-framework (EEA 2007; see Hein et al. 2016 for another DPSIR-application comparing different floodplains) to review status of biodiversity in floodplains, pressures on floodplain biodiversity and their impacts as well as MFM as response and evidence for its effects on biodiversity. We also predefined that the contributions should be narratives containing the information that was judged to me the most relevant for each section and that grey literature should be adequately considered, not least because other methods such as systematic reviews strongly relied on evidence published in international scientific journals, while it was challenges to integrate practical experience and local knowledge (Schindler et al. 2016). These narratives were complemented with tables that summarize a standardized way key information on floodplain habitats, pressures on floodplain biodiversity, impacts of floodplain management measures, and main elements of floodplain management approaches. Based on these country-specific assessments, we discuss interdisciplinary concepts that have been developed to create “win–win” situations in timely floodplain management, including substantial improvement of the ecological status of the respective floodplains. We further compared the relevance of the assessment in comparison to other products of the trial assessments of ‘BiodiversityKnowledge’. In the following we present the result of our assessment in the order (i) status, (ii) pressures and impacts, and (iii) response.

Results

Status: rivers, floodplains and their biodiversity in the six countries

In Ireland, there are 74,000 km of river channel including 38,000 km of the smallest order streams (Byrne and Fanning 2015). Larger Irish rivers, such as the Shannon, Lee, Suir, Nore, Barrow, Slaney, Munster Blackwater and Boyne, often have extensive floodplains. The River Shannon catchment alone covers an area of 14,700 km2, and one-fifth of the land area of Ireland ultimately drains into the Shannon system (Browne et al. 2002). For administrative reasons Ireland has been divided into seven river basin districts due to the requirements of the Water Framework Directive (WFD) (DECLG 2013). Many of Ireland’s rivers, including the eight listed above, are designated under the EU Habitats Directive as Special Areas of Conservation (SACs) for the conservation of fish, lamprey, otter and several other aquatic species listed in Annex II of the EU Habitats Directive (Dromey and O’Keeffe 2004). Irish floodplains are also important areas for bird species listed in Annex I of the EU Birds Directives such as Greenland White-fronted Goose (Anser albifrons flavirostris), Whooper Swan (Cygnus cygnus) and kingfisher (Alcedo atthis). Irish floodplain habitats of conservation concern include Molinia meadows and Alluvial forests (Table 1).

The Netherlands are dominated by the Rhine river delta, consisting of the main branches Ijssel, Lower Rhine and Waal. Rivers with smaller catchments are the Eems and Scheldt. Being at the bottom end of these rivers has a particular impact on the Dutch landscape morphology, but also on river dynamics. In the Netherlands rivers and consecutive wetlands form the backbone for the National Ecological Network and create with their floodplains a corridor through different lowland landscapes (Van der Sluis et al. 2004). Nationwide the network NATURA2000 networks covers 10.8 % of the terrestrial area, whereas almost 60 % of the active floodplains are NATURA2000 including fifteen Annex I habitat types (Table 1).

In Germany there is a wide range of different river and floodplain types, from alpine streams to lowland rivers (Dister et al. 1990; Koenzen 2005; Pottgießer and Sommerhäuser 2008), supporting multiple types of uses of both aquatic and riparian areas. The large catchments of the Rhine, Elbe, Danube, Weser, Ems and Odra dominate the hydrographic system, overlain by the topographical regions of the alpine/prealpine, the central low mountain range and the northern lowlands. Some rivers and floodplains in Germany are still hotspots of biodiversity (Ackermann and Sachteleben 2012) but a nationwide inventory of floodplains in quantity and quality has revealed great losses on both scales, their value slowly and steadily decreasing in nearly all parts of the country (2009; BMU 2009). Nationwide the network of 5,253 NATURA2000 sites covers 14.5 % of the terrestrial area, whereas more than 50 % of the active floodplains are NATURA2000 sites with a considerable number of Annex I habitat types (e.g. large areas of alluvial forests and lowland hay meadows, see Table 1) and Annex II species.

Slovakia has a dense network of streams; its territory is crossed by the main European watershed between the Black Sea (96 % of the Slovak catchment area) and the Baltic Sea (4 % in northern Slovakia). There are 32 rivers in Slovakia, the Váh (406 km), the Hron (298 km) and the Nitra (193 km) are the longest. Nationwide the NATURA2000 network covers 29.6 % of the terrestrial area, whereas 58 % of the active floodplains are located in fifteen NATURA2000 sites (Stanová and Valachovič 2002). Annex I habitat types in floodplains mainly include Ranunculion fluitantis and Callitricho-Batrachion vegetation, hydrophilous tall herb fringe communities, alluvial forests and riparian mixes forests (Table 1). However, forest habitats have been strongly impacted by anthropogenic pressures during the last 70 years and occur in many places only as small fragments of primary tree species composition or as larger complexes with changed species composition in behalf of planted clone poplars (Dister 1999; Oszlányi 1999). Biodiversity related to rivers is rich and varied, many taxa are listed in Annex II Habitats Directive; e.g. the animals Lutra lutra, Castor fiber, Ciconia nigra, Charadrius dubius, Haliaeetus albicilla, Gobio kessleri, Zingel streber and Lycaena dispar that are partly important indicator species for floodplains (Dister 1999).

Hungary’s most important river is the Danube (in Hungary 417 km) (Somogyi 2001). Its largest tributary, the Tisza, collects water from the Carpathians. Reaching the lowland areas of Hungary, both rivers slow down, get middle section character and form one of the largest floodplains of Europe (Somogyi 2001). They are characterized by alluvial meadows and tall herb communities, open water surfaces, marshes, fens and reed beds and the characteristic standing water communities in the backwaters (Table 1) (Molnár et al. 2008a; Haraszthy 2014). The Hungarian rivers are currently bordered by willow shrubs, alluvial forests and riparian mixed forests (Table 1) (Haraszthy 2014).

The Ukraine has nine rivers with catchment basins larger than 50,000 km2. There are 43 lakes with a surface of more than 10 km2 and most of them are situated in floodplains (Gusieva 2012). The basins of Dnieper, Southern Bug and Severski Donets lie mostly within Ukraine, whereas the largest parts of the other catchments are located in neighbouring countries (Romanenko 2004). Despite recent losses due to human impact, floodplains are still rich in biodiversity and host almost all Annex I habitat types typical for floodplains in any of the other five countries (Table 1). Also 80 % of the Ukrainian tetrapode species including 27 species of herpetofauna (Bulakhov et al. 2007; Gasso 2009; Giller 2002) and 300 bird species (Bulakhov et al. 2008). They also host more than 700 species of algae (Gerasimova 2006), 1000 species of vascular plants (Koreliakova 1977; Baranovsky 2000; Baranovsky and Aleksandrova 2005), 250 species of zooplankton (Mykolaichuk 2006), 200 species of zoobenthos (Zagubizhenko 1999), and 65 fish species (Kochet 2010).

Pressures and impact: relevant pressures on rivers and floodplains, historical floodplain regulation and its biodiversity effects

In Ireland, land use developments that affect rivers and their floodplains include agricultural intensification, urbanization and housing developments, tourism and leisure activities, peat extraction and forestry. However, as in several other countries the most important pressures for floodplain biodiversity are alterations of hydrological conditions and invasive alien species (Table 2). Agricultural intensification over the last 50 years has resulted in the drainage of wetlands, channelization of rivers, and has contributed to the increased eutrophication of Ireland’s rivers, which is an important threat for aquatic biodiversity (Moorkens 2000). In recent decades, and especially over the last 20 years, urbanization and building on floodplains in particular has become a problem, with the destruction of wetland areas resulting in flooding problems for residents in these areas. Forestry and its clear-felling may also cause problems, as clear-felled areas suffer from a range of impacts including soil erosion, with the resulting soil particles washing into river systems (Giller et al. 2002; Hutton et al. 2008). Similarly, the drainage of bogs, often a precursor to peat extraction, can result in increased siltation into rivers (Moorkens 2000), as can the extraction process itself (Anonymous 2003).

There is a long history of regulating rivers for power generation and transportation services (O’Grady 2006). The channelization of rivers and the associated dredging and building of earth embankments greatly reduced the size of floodplains. Rivers have also been regulated to improve the supply of water to major cities; one of the largest such projects, the Poulaphouca Reservoir on the River Liffey, was commissioned in 1938 to serve hydro power generation and the water supply needs of Dublin city (ESB 2015). The rivers Shannon and Lee have also been regulated for hydro power, with the Ardnacrusha hydro power plant the first to be commissioned, in 1929 (ESB 2015). Severe water shortages were experienced in Dublin between 2010 and 2013 and it is planned to obtain water from the Shannon river system for the Irish capital (Irish Water 2015a, b).

Large-scale developments on rivers such as hydro power structures pose a considerable barrier to the movement of fish, and even the smaller constructions such as weirs have an impact on the movement of aquatic species (King et al. 2011). The management of water levels for hydro power schemes has also been shown to have a negative effect on breeding birds (Mitchell 1990), and on certain rare plant species, such as Inula salicina (Martin 1998). Similarly there is evidence that increases in suspended solids, as a direct result of forestry and peat cutting activities, can in some river stretches affect key stages in the life cycles of aquatic species (King et al. 2011), such as salmon spawning, and survival rates of freshwater pearl mussel juveniles (Moorkens 2000).

The Dutch floodplains have fertile soils, which are rich in nutrients. From medieval times onwards tall fruit tree orchards were planted. In the 1960s and 1970s many of the orchards were uprooted for meadows. From 1980 onwards more orchards were reestablished, using more productive low fruit trees. In the lower parts of the floodplains meadows developed or, in the swampy areas, willows grew. Later, the opportunities for tillage improved due to better drainage systems and improved fertilization methods. Horticulture occurred on coarse sandy soils with clay substrate (Jongmans et al. 2013). The river area was also an important source for clay, sand and gravel (De Mulder et al. 2003).

The main biodiversity pressures in Dutch floodplains are related to alterations of hydrological conditions, agriculture, and soil pollution (Table 2). The large-scale building of dykes started in the fourteenth century. Initially, a low embankment was constructed along the border of the river to prevent the flooding of floodplain meadows. To prevent larger floods the much higher winter dykes were constructed, but they regularly broke due to stagnant ice (Van Beusekom 2007). Human encroachment and construction of dykes in the period 1850–2000 resulted in a restriction of discharge capacity and a loss of retention area. The Delta Plan, for which the first ideas were conceived in 1937, was launched. After the 1953 flood, the focus was on the sea defense in the Dutch delta and large dams closed off all river arms from the sea. After a severe flood event in 1995 a programme was initiated to reinforce the inland river dykes. Also, at that time a debate started on the development of water retention areas as flood protection measures. Due to rising sea level and increasing discharge of the rivers, the second Delta Plan was launched in 2008 to prepare the Netherlands for the effects of climate change (Kabat et al. 2009).

The biodiversity of the Dutch floodplains is impoverished, due to reduced natural dynamics and a history of intensive land use. The rivers were important for industry due to their transport potential and the presence of industrial water. This resulted in severely polluted water for many decades and floodplains still have high contamination rates of heavy metals and PCBs. The transport function of the river in combination with flood protection measures resulted in decreased natural dynamics where the river was managed to optimize transport and to minimize flood risks. Land reallotment, accompanied by drainage of marshland and removal of old parcel boundaries added to the decline of biodiversity, in particular hedges and tree rows, typical for diverse cultural riparian landscapes (Agricola et al. 2011).

During the last centuries, floodplains in Germany have largely decreased, and on a national level, just one third of the former floodplains still exist (BMU and BfN 2009). In major catchments, such as the Rhine, Elbe, Danube and Odra, only 10–20 % of the former floodplains are left (Brunotte et al. 2009). Local activities started long before the Middle Ages until 1800, but were scattered and mainly confined around settlements. They have been carried out mostly for the purpose of flood protection of settlements and agricultural areas. Systematic works began around the 1820s with conceptually laid out river bed fixation, and cut-off of side channels, oxbows and meanders, often backed by dyke construction (e.g. Tulla’s “First Rhine correction” 1828–1878). It was the growing importance of steam boat navigation that triggered the second phase of corrections with the aim of establishing a stable and constantly sufficient water level in the fairway. Measures included groynes and weirs, bank revetments and training walls. Modern river correction was determined by new construction technologies and capabilities, optimizing the waterways for larger navigation capacities and (on the Rhine following the Treaty of Versailles) for the increasing importance of hydropower use.

The main pressure for biodiversity of German floodplains is without doubt the alteration of hydrological conditions, however, there are several additional pressures that are highly relevant (Table 2). Floodplain forests are largely managed for timber extraction with only a few near-natural stands remaining. In addition almost all natural floodplain habitat types are suffering from a loss of dynamics. During the last decades, traditionally used wet meadows and grazing areas have been largely removed or severely altered through intensive agricultural use. Recreational use of floodplains is still increasing in many parts of the country, being a threat to conservation goals as well as a chance for a better public appreciation of the value of floodplains and rivers. The destruction of floodplain habitat is still ongoing. Chances arise from the current restructuring of the classification of navigable waterways for political and financial reasons, which might reveal opportunities for ecological development of certain river and floodplain areas. European WFD and FFH-Directives have triggered widespread activities of responsible authorities, but worries are that structural obstacles and political routine might reduce the needed measures to an inefficient extend. However, a couple of restoration projects have been established recently and could serve as pilots for larger-scale planning.

Demography and land use development in Slovakia was significantly associated with watercourses since the Paleolithic period. First settlements in the Mesolithic and Neolithic followed alluvia of rivers in lowlands and uplands (Rulf 1994). Direct systematic human interventions into the channels of major Slovak rivers date back to the 1770s, primarily in order to improve navigability and facilitate river transport. The earliest structures of erosion control and flow diversion represent wicker works, fascines, cut trees serving as breakwaters, groynes and bank revetments (Pišút 2006). The main biodiversity pressures in Slovak floodplains are related to alterations of hydrological conditions and alien species (Table 2). In Slovakia, almost one tenth of its territory (4500 km2) has been drained, followed by the construction of water works, regulation of water flow and exploitation of peat, and subsequently leading to the disappearance of wetlands and water ecosystems. Synchronously to infrastructural and housing developments in Slovakia there has been a loss of agricultural and arable land to forests (Klinda and Lieskovská 2010). Agricultural soils are still contaminated at the level of the early 1990 s, and must be further monitored (Klinda and Lieskovská 2010). In terms of river and floodplain regulations, most of the gravel-bed Váh River is regulated with canals, artificial dams and 22 hydropower stations. The Morava and Hron Rivers were straightened between 1930 and 1960 (Holubová et al. 2005). The lower Morava was shortened by more than 10 km by cutting off 23 meanders. The Lower Hron still maintains a certain degree of freedom to migrate, although flow dynamics and sediment transport are influenced by small hydroelectric power stations and the river shows higher concentrations of suspended load and rapid sedimentation in cut-off meanders (Holubová et al. 2005). Between 1378 and 1528 AD, large avulsions on the Danube River resulted in the abandonment of the 24 km-long lowermost stretch of the Dudváh River (Pišút 2006). At Bratislava the floods of the 1760 s and 1770 s triggered a series of channel adjustments and subsequent human interventions, leading to permanent instability of the river channel (Pišút 2002). The modern Danube is the result of the mid-flow channelization which happened from 1886 to 1896. Present-day fluvial processes of the Danube are restricted to the riverbed and the floodplain area between the embankments (Szmańda et al. 2008). The sediment transport through the Slovak section of the Danube has been recently affected by the hydropower plants Freudenau (at Vienna, Austria) and Gabčíkovo (Holubová 2000).

The Gabčíkovo–Nagymaros dam project at the Danube resulted in an international conflict between Slovakia and Hungary that was solved at the International Court of Justice in The Hague. The main aim of the project was the improvement of flood protection, river navigability and hydro power production. This construction had an enormous impact on ecological conditions in the Danube floodplains. Many scientific works describe in-depth research and monitoring conducted to elucidate the effects on particular taxonomic groups of plants and animals (Mucha 1999). Several studies demonstrate decline in biological diversity (Bulánková 1995; Krno et al. 1999), which is added to by competition by invasive alien plants (Huba et al. 1998), and the impoverishment of the species inventory of most forest communities (Uherčíková et al. 1999). Also in other Slovakian floodplains, habitat loss and fragmentation has led to the eradication of numerous organisms and the loss of functions which contribute to the preservation of the ecological balance (Klinda and Lieskovská 1998). The problem has increased in the last years, to the extent that a petition was sent to the Slovak Minister of the Environment in 2011 that contained detailed descriptions of the eradication of several fish populations. Also the Tisza River catchment was prone to biodiversity loss due to historic mistakes in floodplain management such as the destruction of large wetland areas (ICPDR 2011).

In Hungary, landscape transformations influencing the present landscape started in the late eighteenth century. Their main driving force was the increased European demand for cereals (Andrásfalvy 2007). Traditional floodplain management had been abandoned and the tillage area could be increased most efficiently by reducing the floodplain area and draining the large lowland marshes and moorlands found in the Tisza basin. For more efficient transportation of crops, rivers had been shortened, and dykes had been built. Wide-scale river regulations started in Hungary in 1846 (Somogyi 2001). Altogether 114 meanders of the Tisza were cut through, shortening the river’s whole length by 453 km (32 %) (Somogyi 2001). The river’s fall increased significantly, causing accelerated deepening of the river bed and, at high waters, the filling of the floodways with its own sediments. Outside the newly built dykes, inland waters accumulated, which was mitigated by floodplain drainage with 40,000 km of channels (Somogyi 2001). The majority of the floodways (i.e. the areas between the two dykes) remained under traditional smallholder use (e.g. crops, orchards pastures, meadows and vegetable gardens) until the 1980 s. Its abandonment resulted in a rapid degradation of the semi-natural habitats by the end of the twentieth century. More recently, some regions along the Tisza are losing their human population as a consequence of serious economic and employment difficulties (Mihók et al. 2006; Balázs et al. 2009; Borsos et al. 2010). The main actual pressures for Hungarian floodplain biodiversity are alterations of hydrologic conditions and invasive alien species, but also forestry, agriculture and effects of hydro power stations built outside the Hungarian border are highly relevant (Table 2). Despite all these pressures, three national parks have been established along the Danube, and nationally protected areas or Natura 2000 sites are relatively spacious (Beckmann and Jen 2004). Multilateral dialogues started with the objective of transforming the current river management regime (Sendzimir et al. 2007; Werners et al. 2009; Borsos et al. 2010; Somlyódi 2011).

In the last decades, the drainage of inland waters caused water shortage in some landscapes and contributed to increasing numbers of catastrophic floods in others (Somlyódi 2011). The loss of water had simultaneous ecological and social effects. The former shallow water surfaces, temporally inundated pastures and managed fishponds flooded by the Tisza were integral parts of the diverse traditional land use system, causing extreme abundance of fish in the region (Andrásfalvy 2007). This system has been gradually cut back in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, and ended totally with the construction of the dykes (Andrásfalvy 2007). The landscape change decimated not only the fish stocks but also the once famously rich avifauna: based on historical data, by the twentieth century nesting of white pelicans (Pelecanus onocrotalus) and common cranes (Grus grus) ceased, and the numbers of ducks, geese, herons, pygmy cormorants (Phalacrocorax pygmaeus), great bustards (Otis tarda) and saker falcons (Falco cherrug) became markedly less (Ecsedi 2004). Significant increases in the number of alien fish, reptiles and mollusks started at the end of the nineteenth century, and currently exceed 40 species in the Danube (Bódis et al. 2012). The proportion of alien species in the fish fauna in the larger rivers is 10–16 % (Erős 2007). Floodplain meadows, tall herb communities and marshes shrank to a fraction of their original extent. Meadows isolated from the floods have been transformed into arable land or dry short-grass steppe (Molnár and Borhidi 2003). In the last decades habitat quality and regeneration potential of floodplain habitats is rapidly decreasing due to the expansion of invasive species and land abandonment (Botta-Dukát 2008; Molnár et al. 2008b; Biró 2009).

Also in the Ukraine, large rivers, especially Dnieper, Severski Donets, Southern Bug, and their main tributaries are under constant anthropogenic influence. From 1930 to 1980 the main objective of the national economy was the river regulation for water engineering and land improvement. In the Dnieper storage reservoir cascade, for instance, consists of 1,103 large water storage reservoirs and 48,000 smaller artificial ponds (Gusieva 2012). The river regulation history in Ukraine was initiated in 1927, when the construction of Dniprovska hydropower station began, which was finished in 1935. From 1950 to 1975, five more water reservoirs were created and the Dnieper flow became completely regulated (Denisova et al. 1981). On the Southern Bug, the distinctive feature is the intense regulation of flow by 197 water basins and almost 7000 ponds with a total volume of 1.5 km3; currently most of these hydroelectric stations are ruins. The riverbed of the Ukrainian part of Seversky Donets is dammed three times. Many tributaries also have multiple dams; eight are located near Kharkiv, with more than ten around Sloviansk. In river basins of the middle-sized rivers of the Ukraine some small water reservoirs and many ponds were constructed since the 1960 s (Vyshnevsky et al. 2011). By 1990 the reservoirs’ area made up 761,000 ha (1.26 % of the country territory); 70 % of this inundated areas were former floodplains (Anonymous 2004). The most important pressures for Ukrainian floodplain biodiversity are alteration of hydrologic conditions and invasive alien species, but also settlements and industrial infrastructure, water pollution and eutrophication, hydropower, and mining and quarrying must be considered as highly relevant (Table 2).

The main environmental effect of river regulation was that huge areas of floodplains became permanently flooded, sometimes, also the second terraces of river valleys (Avakjan and Sharapov 1968; Vendrov 1970; Vyshnevsky et al. 2011). The landflood resulted in total destruction of natural vegetation and ecosystems of floodplains and in the occurrence of large areas of impoundments having quite a weak current. For 3–4 months per year, 80–90 % of the Dnieper water area blooms and biomass of cyanobacteria averages about 60–100 g/m3 (Yatsyk et al. 2007). The areas closed to the reservoirs are depleted wetlands, which are frequently protected by dams (Vyshnevsky et al. 2011). The flow regulation at the middle stretches leads to permanent flooding of bottomland and disturbance of their hydrological regime. Water levels are kept rather low in times of floods to protect the hydropower dams from destruction. The absence of high water changed the regime that had existed for millennia, and thereby reduced the removal of excessive organic matter from inundated reservoirs and diminished the beneficial natural fertilization of the floodplain soil by floods. Small rivers, which are highly relevant and form 60 % of the water resources of Ukraine, are also regulated and spring riverbed flushing is artificially reduced. In conjunction with the ploughing of land in river valleys this leads to inevitable silting and overgrowing of water bodies with aero-aquatic plants (Baranovsky et al. 2001).

As a result of all these developments, natural floodplain ecosystems changed considerably. Meadows, woods and arable lands were flooded, hydrology and hydrochemistry were altered, the soils were impounded, the vegetation changed and initial high level of biodiversity decreased strongly (Akinfiev 1889; Baranovsky and Aleksandrova 2005; Baranovsky et al. 2007). For instance in the area of the Dniprovske reservoir, 795 higher plant species were registered in the floodplain before construction works started. 150 of these species disappeared and many others became rare, whereas 90 alien species invaded the area (Baranovsky 2000). Naturally diverse woodland ecosystems of floodplains (Belgard 1950) changed into simple communities with reduced biodiversity. Forest ecosystems covering and surrounding Ukrainian floodplains in the past (Nikolaenko 1980), were largely degenerated or lost and replaced by meadows, pastures and tillage. The incessant destruction of the smaller rivers became one of the biggest regional environmental problems entailing sediment deposition in the larger rivers, summer bloom and fish kills caused by suffocation (Baranovsky et al. 2001). In the Dnieper basin the ecological conditions of the majority of small rivers are qualified either as catastrophic or as bad (Zagubizhenko et al. 2002; Yatsyk et al. 2007). Ecological changes include increased sedimentation and development of reeds (Phragmities australis (Cav.) Trin. ex Steud) that transformed a natural community into a simpler and depauperate one.

Response: floodplain conservation and restoration, multifunctional floodplain management and evidence for effects on biodiversity

The legislation and implementation in terms of floodplain management of all the mentioned countries except the Ukraine have been similarly influenced by their membership in the EU and the related policy framework such as the WFD, the Flood Protection Directive, the Habitats Directive, the Birds Directive, as well as the related financial instruments (in particular LIFE, LIFE+ and the funds of the EU’s Regional Policy) (Mauerhofer 2010).

The management of floodplains in Ireland is still focused on flood alleviation, with the building of embankments and other flood defenses being a common approach. There is also still an emphasis on the drainage of frequently flooded areas, rather than reinstating natural wetlands to slow down the rate of percolation of water through the system and therefore to slow down the rate at which the water reaches the rivers. The most common example of multifunctionality is likely the construction of weirs designed to ensure that they perform the role of water flow control while also facilitating the movement of fish and other aquatic species through the river system.

Small local-led initiatives funded by the EU Life programme have been the basis of several river restoration projects in Ireland which have sought to take a multifunctional approach to management. One such restoration project is MulkearLIFE (www.mulkearLIFE.com), which aims to restore 21.5 km of degraded habitats along stretches of the Mulkear River, which drains a total catchment area of 650 km2. The main focus is to provide habitat for sea lamprey (Petromyzon marinus), Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) and European otter (Lutra lutra). The project addresses multifunctionality by engaging with fisheries, farmers and the local community to achieve its multiple goals of improved water quality, locating alternative sustainable water sources for cattle, control of invasive species, and fostering a greater awareness locally of conservation issues relating to the river, its biodiversity and the ecosystem services that it supplies. A similar EU Life project has run in Duhallow, Co. Cork. Both of these projects have occurred in Special Areas of Conservation designated for their river habitats and associated species. In another project in County Kerry, biodiversity enhancement works to the River Lee at Ballyseedy Wood, an Annex I alluvial woodland, were recommended by O’Neill et al. (2008). Funding was received in 2012 and the project is expected to lead to improved water quality and enhanced conditions for spawning salmonids, with benefits expected for overall biodiversity and recreational fishing to the area. The Lough Melvin catchment management plan (Campbell and Foy 2008) is another project that applies a multifunctional approach, with the main aim being to reduce nutrient levels within the catchment. It has 22 recommendations covering impacts such as agriculture, forestry and wastewater from housing. Some of the most notable recommendations include (i) education programmes for landowners whose activities impact the environment, (ii) policies that restrict one-off housing in sensitive parts of the catchment, (iii) initiatives to deal with alien invasive species such as northern pike (Esox lucio), (iv) screening of forestry operations in the catchment for appropriate assessment under Article 6 of the Habitats Directive, (v) a package of agri-environment measures for the Lough Melvin catchment, and (vi) active management of riparian forest buffer zones to reduce the impact of neighbouring clear-felling.

To our knowledge there is no Irish evidence for biodiversity effects of multifunctional floodplains. However, evidence for failure of monofunctional conservation projects is available (Maher et al. 2011) and based thereon recommendations for multifunctional approaches were derived that include considering the needs of all stakeholder groups including conservation organizations, farmers and the tourism and leisure industry (Maher 2013).

In the Netherlands, the approach towards floodplains changed over the last two decades. The overall aim is to increase multifunctionality, with flood protection and increasing biodiversity being among the most important functions (Fliervoet et al. 2013), another important function is tourism. In the same period, water quality improved significantly due to the raising of environmental standards and international cooperation such as the International Rhine Committee. Through application of a mixed centralized–decentralized governance approach, the Room for River programme has dealt with governance pitfalls related to centralized planning approaches that previously impeded integrated water management (Rijke et al. 2012).

Planning for more natural floodplain development began in 1986, when landscape architects and spatial planners launched the development plan ‘Plan Stork’ that set into motion a school of planners and ecologists that promoted MFM. WWF Netherlands adopted this approach and a foundation ‘Ark’ was established with the aim of restoring natural processes; the programme was in line with the Dutch conservation programme (Kurstjens and Peters 2012b). It was a kind of new paradigm, which coincided also with the Ecological Network approach which was since 1991 leading for the Dutch conservation policy (Van der Sluis et al. 2012). In 1993 and 1995 the water levels were extremely high, and a quarter of a million people had to be evacuated. Extreme high river discharges are predicted to occur more frequently in the future and therefore it was decided to increase the discharge capacity of the rivers. The Government approved the Room for the River Programme in 2007 for the Rhine. This plan has three objectives (i) by 2015 the branches of the Rhine must be able to cope with a discharge capacity of 16,000 m3/s without flooding; (ii) the measures implemented to increase safety must also improve the overall environmental quality of the river region; and (iii) the additional retention area for the river, required to cope with higher discharges, will remain permanently available for this purpose. In total, nine options are considered to enlarge riverbed and floodplains, including dyke relocation, depoldering, and water storage (Fig. 2). The approaches presented in this figure are rather advanced examples of eco-engineering, and are expected to have different impacts on multifunctionality, natural dynamics, and biodiversity (Table 3). Of the 700 potential projects that were identified in the area of the Rhine and the Ijssel, 39 were selected (Rijke et al. 2012), with 35 projects to be implemented in the period 1995–2015. For the River Meuse, the Meuse Works Programme, was officially initiated in 1997 and scheduled for completion by 2018. The aims were similar to the ones for the Rhine: fewer floods, better navigability, a wider river bed and a more natural river valley. In total, 1800 ha are to be converted to nature restoration areas, and 52 projects are or have been executed in the Meuse areaFootnote 1; they focus on dyke improvement, tourism and grazing management.

Nine approaches of river restoration by reconstruction of the floodplains and the river bed (based on: the Dutch ‘Room for the River’ Programme: http://www.ruimtevoorderivier.nl)

Nature restoration projects along the Meuse were executed from 1995 onwards (Kurstjens and Peters 2011). The Meuse floodplains changed from an area which was mostly farmed or used for mineral extraction to a multifunctional area aimed at flood security, natural functions and recreation. The extent of natural floodplain habitats along the Meuse increased from 100 ha in 1990 to 1500 ha in 2006 (Kurstjens and Peters 2011), and the number of such areas increased from four to 42. An evaluation showed the following success for nature restoration (Kurstjens and Peters 2012a,b): (i) 40 % of the plant species benefited from the creation of floodplain meadows, scrub, and forest on former farmlands; (ii) increased river dynamics resulted in new habitats as well as the establishment of new plant populations; (iii) through excavation, pioneer situations were created; (iv) dispersal of seeds was enhanced by large grazing animals; and (vi) water quality improved for aquatic species. A strong increase in the riverine flora happened particularly in locations with sandy soils, where sand dynamics are a crucial factor. While increased dynamics also resulted in the loss of species that depend on stable situations, the overall impact was an increase in species diversity. Mammal indicator species such as Eurasian beaver (Castor fiber), European otter and European badger (Meles meles) returned. They had been absent from the rivers since the 1960 s, or extinct in Dutch territory in the case of the Beaver. For birds, the situation of pioneer species as well as species from softwood and hardwood forests and colony breeders improved significantly. However, marshland and farmland birds have not recovered yet or are still declining, despite active restoration plans (Kurstjens and Peters 2012a). Of the amphibian species the Great crested newt (Triturus cristatus) occurs along the different branches of the Rhine (Creemers 1994), and among reptiles, the Grass snake (Natix natrix) shows a positive trend along the natural floodplains of the Lower Rhine. The populations of fish of running water are increasing because of the improved water quality of the Rhine and the construction of side channels. Even fish species which were extinct have returned, such as the Atlantic salmon, for which conservation plans were implemented and many rivers were made passable (Van der Sluis et al. 2004). Recovery of butterflies is slow; the two areas with the highest species density are the Blauwe–Kamer and the Duursche Waarden (Online Ressource 1). The number of dragonflies has much increased due to the improved water quality, climate change and increased biotope diversity, especially in the Blauwe Kamer and the Duursche Waarden. Grasshoppers have also benefited. For some species climate warming is a relevant factor in recovery (Warren et al. 2001).

In Germany, multifunctionality is, to a very limited extent, included in various legal regulations. For instance, the Federal Water Act demands water managers to preserve, protect and even improve natural habitat, to preserve and improve current and potential uses of water resources, thus to manage resources beyond water in a sustainable manner. This is not yet multifunctional, but is intended at least to open the scope of authorities’ actions in order to comply with other sectors’ objectives. In particular, conservation goals have increasingly been included in other sectoral laws.

River restoration occurred mostly through the implementation of projects along smaller rivers and streams within the regular river maintenance “Gewässerunterhaltung”, many of these activities being a result of successful WFD implementation. Furthermore, several large projects have been carried out which tackled multiple aspects at a time, mostly flood protection and nature conservation, e.g. at Elbe, Danube, Rhine (again mostly in connection with the WFD), but also recreational areas in urban settings (e.g. Emscher project, Isar in Munich).

On a national level, the Federal Agency for Nature Conservation has financed restoration projects for about 15 years to enhance both nature conservation and flood protection. Moreover, a number of federal state programmes have been implemented primarily to increase the level of flood protection, especially with regard to climate change aspects. Nature conservation aspects are included to different extents in such programmes. For example, the Integrated Rhine Programme of Baden-Wuerttemberg started out as a combination of flood protection and floodplain conservation; the latter aspect has unfortunately been largely abandoned in the course of the programme. Synergic benefits of river and floodplain restoration e.g. mitigation of flood risk or of consequences of climate change, are far from being fully exploited and multiple environmental effects are still neglected. The ecosystem approach can help to provide a long-ranging delivery of natural resources and services depending on their sustainable use (BMU 2008).

Conflicts on future floodplain management regimes have emerged in cases where flood managers planned to use near-natural floodplain areas as controlled flood retention polders, which would involve an intentional, rapid filling of floodplain areas with water abstracted from the river during the peak phases of floods. Hydrologists consider this type of targeted polder filling as the most effective way of lowering peak flood levels in downstream sections of a river (Müller 2010). Such polder filling is accompanied by rapid increases in water levels in distinct floodplain areas enclosed by dykes on all sides with no significant through-flow of water. The obtainable flood peak reduction strongly depends on the shape of the flood hydrograph and its predictability (CRUE 2008; Förster 2008). Polders impose severe detrimental effects on the affected biocoenosis such as oxygen deficiency and sedimentation, their infrequent flooding impeding the development of flood-adapted species communities (Dister 1992; Armbruster et al. 2006).

A number of studies in Germany supports the hypothesis, that river and floodplain restoration measures increases biodiversity (Kail et al. 2015), with positive effects being more pronounced in terrestrial than in aquatic habitat types (UBA 2014). Whereas restoration successes prevail, neutral and even negative effects of restoration measures have also been reported in particular for aquatic organisms (Sundermann et al. 2011; Lorenz et al. 2012). A research project commissioned by the German Federal Agency for Nature Conservation revealed that restoration projects have been realized within some 5 % of the floodplains in Germany (BfN 2013). These cover about 40 projects alongside bigger rivers, in which approximately 4000 ha of floodplains have been reconnected by dyke and dam relocation in the last 15 years (BfN 2013). Although there is yet no suitable systematic study covering a representative number of restoration projects within smaller streams and catchments, there is some evidence that, due to restoration and subsequent management changes, the biodiversity value of the restored floodplains can significantly increase. Lüderitz et al. (2011) investigated the development of biodiversity during a large-scale river restoration project with a restored section of about 18 km compared to adjacent non-restored sectors. The study showed that species numbers were two to three times higher in the restored reaches. This increase applied to all taxonomic groups, but was particularly significant for Odonata, Trichoptera, Plecoptera and Ephemeroptera (Lüderitz et al. 2011). However, far more research is needed to analyze, monitor and evaluate further biodiversity effects of MFM.

In Slovakia, conservation of inland water ecosystems is one of several activities within the implementation of the Convention on Biological Diversity and the Ramsar Convention. Besides the National Biodiversity Strategy and its components related to ecosystem protection, Slovakia additionally adopted a National Programme on wetlands (according to the Ramsar Convention) and a programme on the restoration of river banks. Also an Integrated River Basin Management and a Land Restoration Programme have been implemented and restoration of water courses, bank vegetation and natural water regimes was performed.

One of the successful projects dealing with the floodplain restoration was the LIFE-project ‘Conservation and management of Danube floodplain forests’. The objective was to conserve the last remaining natural floodplain forests in the Slovak part of the Danube floodplain and to introduce sustainable forest management in the area (BROZ 2003). Project actions focused on halting the loss of natural floodplain forest habitats by improving forest management plans, applying ecological forest management measures, planting of native trees, designation of new nature reserves, land purchase and lease for nature conservation purposes and raising awareness of the general public, decision makers and other key stakeholders.

The productivity of arable fields in the floodplains is several times lower than the production from meadows (Šeffer and Stanová 1998). Intensive agricultural practices are not sustainable and polluted together with industrial developments the Morava river and its tributaries (Šeffer and Stanová 1998). The Danube and its floodplains play a very important multifunctional role for hydropower, transport, flood protection, biodiversity conservation, and creation of natural flow regimes, purification and remediation, and recreation and tourism (Lisický and Mucha 2003). The Váh River provides a significant supply of electric power; however, flood protection is also an important issue, as well as water provision for irrigation of agricultural areas, and tourism and recreation.

Slovakian floodplains host two large Protected Landscape Areas (PLAs) (Latorica and Dunajské Luhy), 14 Ramsar sites and more than 200 small protected areas (National Natural Reserves, Natural Reserves and Protected Areas). Beside flood protection, MFM often implies biodiversity conservation, but also of importance are recreation and tourism, namely hiking, swimming and sailing. Particular examples for MFM are the floodplains of the partly still meandering Morava River that include riverine forests and flooded meadows and are one of the most valuable wetland areas in Central Europe (Ruzickova et al. 2004). The 90 river kilometres that are forming the boarder to Austria are an important element of the European Green Belt (Zmelik et al. 2011) and the Alpine Carpathian Corridor (Strohmaier et al. 2008). Restoration measures such as reconnection of meanders with the river system, increase of flow dynamics, excavation of sediment deposits from meanders, and special mowing scheme are proposed and partly implemented to conserve the natural values and the derived human benefits (Rybanič et al. 1999; Holubová and Steiner 2011). Hay production has shown to significantly affect biodiversity because regularly mowed meadows maintain high vascular plant diversity including rare and endangered species, and nitrogen abatement has also positive effects on the plant communities (Šeffer and Stanová 1999). After 1990, arable fields in active floodplain areas were restored back to meadows to increase biodiversity and to decrease river pollution (Šeffer et al. 1999). The results show that the re-establishment of floodplain meadow communities can occur quickly and that rare species can reestablish and persist (Šeffer et al. 1999).

River and floodplain restoration projects in Hungary mostly target the reconstruction of oxbows, grasslands on abandoned arable fields, or pastures and meadows invaded by bastard indigo (Amorpha fruticosa). Grazing, mowing, grassland establishment, clearing of invasive shrubs and trees and restoration of the water balance support their biodiversity conservation functions. The keeping of a traditional cattle breed, the Hungarian grey cattle, has also a gene preservation function in Hungary. Information boards and educational trails in the restored areas serve for recreation and environmental education realizing the multifunctionality in the restoration projects. Some projects have implemented further multifunctionality, like social and economic benefits, producing new jobs or income from livestock and hay production (e.g. projects in Tiszatarján,Footnote 2 Tiszaalpár&Mártély,Footnote 3 Nagykörű,Footnote 4 Esztergom&Ipoly-völgyFootnote 5). During these projects inhabitants have been involved in the management and clearing of invasive species in the floodplain, by which further jobs have been created, fuel wood for winter has been provided, and the heating of public institutional buildings was realized. Traditional fishery management based on the natural dynamics of the river was reconstructed in Nagykörű. The renewal of traditional orchards was realized by the project at Mártély area. By reconstructing former side-channelsFootnote 6 traditional landscape scenery and land-use types, and aesthetic and recreation functions were implemented in all MFM projects project. One recently started regional scale programmeFootnote 7 aims at rural development in addition to habitat rehabilitations along the river Dráva (Elek et al. 2013). Cooperation with neighboring countries is remarkable in several floodplain rehabilitations and the use of EU and national ministry funds was widespread among the Hungarian MFM and floodplain rehabilitation projects.

During most projects diverse landscape structure has recovered, and the quality and naturalness of habitats has been continuously increasing. Abandoned pastures, meadows, arable fields, and invasive bush and tree stands have mostly been changed into regenerating floodplain meadows and native woodlands. Extensive grazing helped grassland regeneration and decreased cover of bastard indigo in almost all cases. Effects on biodiversity are monitored usually by nature protection managers of the National Park Directorates. However, systematic monitoring was implemented in only some of these projects. In two cases monitoring was based on phytosociological or zoological relevés (Demény and Keresztessy 2007; Margóczi and Roboz 2011). In these two areas (Nagykörű and Tiszaalpár) bird monitoring was also conducted. According to these observations White-tailed Eagles (Haliaeetus albicilla) established territories in both areas, and significant numbers of Pygmy Cormorants (Phalacrocorax pygmeus), herons, shorebirds and ducks were nesting and gathering on the lakes. Glossy Ibis (Plegadis falcinellus), Black Stork (Ciconia nigra) and Whiskered Tern (Chlidonias hybrid) were observed on several occasions (Rimóczi, unpubl. data; http://www.tiszalife.hu/en/life_program.html; Bártol 2008; Bártol unpubl. data). In Nagykörű the occurrence of 22 fish species (including two protected species, Misgurnus fossilis and Rhodeus sericeus) was recorded in the new traditionally managed fishpond (Demény and Keresztessy 2007). After the flood of 2006, 20–30 young fish/m3 were found in the lake. In autumn more than 2000 well-developed pikes were released into the river, but the reproduction of invasive fish species still seems to be a problem (Demény and Keresztessy 2007).

During restoration of an alluvial grassland the bastard indigo could be successfully suppressed by grazing or systematic mowing, but it can hardly be entirely eradicated despite interventions every year (Szigetvári 2002; Margóczi and Roboz 2011; Lájer 2012; Sallainé Kapocsi and Danyik 2015). In some of the ancient grasslands, stands of characteristic alluvial species (Orchis laxiflora subsp. laxiflora, Leucanthemella serotina, Clematis integrifolia and Iris spuria) became considerably stronger (Bártol 2008; Margóczi and Roboz 2011). The conversion of croplands and abandoned arable fields into grasslands had varying results. Regeneration was usually slow. In some cases disturbance-tolerant species or weeds became dominant, in other places generalist monocots like Alopecurus pratensis, Poa trivialis, Bolboschoenus maritimus or Elymus repens increased significantly, or occasionally rare annual floodplain species with high nature value (Vicia biennis, Astragalus contortuplicatus) appeared in large numbers (Margóczi and Roboz 2011; Bártol 2008). Habitat naturalness increased by the transformation of woods of non-native species and arable fields into native forests, where young stands of Populus nigra, Fraxinus angustifolia subsp. pannonica, Quercus robur and Ulmus laevis had been established in Tiszaalpár and Mártély. After the oxbow restorations (e.g. river deposits had been removed, floodgates had been built) the increased water level (by 30-40 cm) also improved habitat quality and naturalness, and diverse hydrophyte and wetland habitats developed (Bártol 2008).

Conservation of floodplains in Ukraine is ensured for 33 Ramsar cites by the implementation of the Ramsar Convention. The majority of the Ukrainian Ramsar sites are conserved as national nature parks, nature reserves, biosphere reserves and regional landscape parks. In 2009–2012, floodplains were restored by dyke removal and other measures within the Ramsar Sites “Stokhid River Floodplains” and “Prypiat River Floodplains.” (Anonymous 2012).

Long-term research of plant diversity of rivers of the Dnieper and Southern Bug basins allowed the development of a set of measures for restoration of natural conditions and biodiversity of the floodplains of the Steppe zone (Baranovsky 2000, 2005, 2005; Loza et al. 2004; Baranovsky et al. 2007). Long-term cooperation of scientists with basin authorities and waterworks allowed restoration studies and projects to be realized in the Dnieper basin: (i) hydro-engineering (dredging) works carried out under the control of ecologists (no river-channel straightening was allowed) with conservation of the areas with especially valuable flora and fauna, (ii) restoration of newly formed bank slopes with meadow grasses, and (iii) plantation of forest shelter along river banks with selected species forming a sustainable ecosystem with diverse communities of plants, animals and fungi (Baranovsky et al. 2007, 2009a, 2009c). Thus, floodplain forests recovered providing a high water-regulation capacity (cf. Tkachenko 1975) and formed a microclimate that promotes an increase in biodiversity (Grytsan 2000; Kulik et al. 2008).

Also Dnipropetrovsk National University and the State Regional Planning and Survey Institute “Dniprogiprovodhoz” are conducting multifunctional projects on environmental rehabilitation and biodiversity restoration of rivers (Baranovsky et al. 2013). One of the examples of such works is the project ‘Restoration of a hydrological regimen of the wetland Diovsky plavni’. The project cleared channels of impounded floodplains of the right bank of Dnieper River above Dnipropetrovsk (the upper part of the Dniprovske water reservoir). As a result of the project, an increase in biodiversity was noted in the water bodies and the floodplain (Grytsan et al. 2006) during the first period, mainly for plants. Another example is the project ‘Restoration of a hydrological regime of the Orel River’ at the border of Dnipropetrovsk and Poltava provinces. Riverside forest shelter belts of white willow (Salix alba) were created. The subsequent increase in plant diversity on the floodplain was confirmed (Baranovsky et al. 2009b).

The main purpose of the mentioned projects was to decrease the ground water level of the adjacent populated and agriculture lands for economic reasons. However, thereby the rehabilitation of ecosystems and biodiversity was realized as well. Successful small multifunctional projects of the Dniester floodplain rehabilitation are reported by Rusev and Ruseva (2000). The projects included measures such as clearance of small sections of the river bed, opening small gaps in dykes with subsequent renewal of flowage between water bodies, the reclamation of the riverside slopes, and the plantations of trees. The result was a restoration of the hydrological regime, a revitalization of the floodplain‘s meadows and increases in biodiversity and population abundance: the populations of fish, geese, herons, glossy ibises, ducks and waders increased (Rusev 2003).

Discussion

Multifunctional management of European floodplains

Multifunctional use of floodplains has become an important management strategy in some countries, in particular in The Netherlands and Hungary. This trend is in agreement with developments in floodplains and deltas in Europe (Hein et al. 2016) and in other continents (Wesselink et al. 2015). Multifunctional approaches mainly show success where a large range of stakeholders with diverse expertise and interests are involved in all stages of planning and implementation of projects. It is recognized that such participatory processes are beneficial for environmental resource management (EC 2005; Paavola et al. 2009; Silva et al. 2009). The mixed centralized-decentralized approach in the Netherlands has been effective though in realizing many water safety projects through the stakeholders involved, partly funded through industries. However, it was less effective in the used governance model, and stakeholders views and public support have been questioned (Fliervoet et al. 2013). In Hungary, projects aiming at rehabilitation of biodiversity by clearing invasive alien species have become frequent. In some projects multifunctionality was realized by implementing other functions like economic, social, educational and touristic ones. Although the involvement of local stakeholders and inhabitants at all stages of the process is not yet widespread, the role of common works, public involvement and a multifunctional approach are generally increasing in Hungarian projects. As enhancing biodiversity is an important goal, either the National Park Directorates or the WWF plays a leadership role in almost all projects. Due to projects focusing on areas invaded by alien species, habitat quality and abundance of characteristic floodplain species has generally increased, although systematic monitoring has been scarce. In those projects that aim to restore water balance of oxbows or inner dyke wetlands, diversity of fish and avifauna increased, large numbers of migrating birds appeared, and nesting of some rare and protected birds was observed (Demény and Keresztessy 2007; Bártol 2008 ). This is in concordance with conservation success of similar restoration projects from neighboring countries such as Austria (Funk et al. 2009; Schmutz et al. 2014).

Still in other cases efficient mechanisms are lacking and a big gap remains between the rhetoric on participation and the real-life implementation of participatory processes (Rauschmayer et al. 2009). Administrative structures often support the subsequent standstill at all levels: The sectoral organization of national governmental structures has its analogy in the organization of the European Administration and many European policies are not fostering multifunctionality. In Ireland, for instance, it is recognized that MFM is the best way to manage rivers and their associated floodplains, but there are only a few examples of this recognition being put into practice. There needs to be a more concerted effort by government agencies to promote multifunctional management and to monitor the effects of such management on biodiversity. Also in Germany, multifunctionality is still poorly represented in floodplain management. Programmes and measures which are mostly initiated by governmental institutions are reflecting that public administration is structured in sectors (Nielsen et al. 2013): entities responsible for water management are largely focusing on their respective goals (e.g. flood protection, land use, navigability). Measures initiated by conservation units are focusing mainly on conservation issues rather than on integrated or multifunctional landscape development. This has changed to some extent with the implementation of the WFD, but there is still a general lack of interdisciplinary measures, and this is unlikely to improve in the face of tightening budgets and reduced resource allocation (Nielsen et al. 2013). The importance of the WFD for floodplain management can hardly be overestimated, since no other EU-strategy has triggered so many waterbody related measures (Čimborová and Bartková 2014). However, the WFD focuses largely on ecological improvements, and related projects sometimes do not constitute multifunctional approaches. Even though in its implementation the scope has broadened and positive side effects do touch other sectors as well, future amendments of the directive should be used to further broaden its scope and install multifunctionality as it is already discussed for ecosystem services. Concerning other EU directives, the Habitat Directive similarly targets the safeguarding of natural values and conservation issues and widely lacks a multifunctional background. This could only be changed by broadening its focus as suggested for the WFD. The modern state of floodplains in Ukraine, the only investigated country which has not been influenced by the EU and its WFD, is still determined by long-term anthropogenic influences. The implementation of evidence-based management actions to improve floodplain functionality and to restore lost biodiversity are still few. Multifunctionality as a sustainable management approach for floodplains receives little attention from Ukrainian policy makers and authorities. In the Ukraine, there is much scientific literature on both floodplain biodiversity (Gasso 2009; Banik and Korshunov 2014) and floodplain management (Stefanyshin 2010), but it is often not related to each other and research assessing the biodiversity effects of management interventions would be highly required for many areas (Baranovsky et al. 2013).

When comparing the situation in the investigated countries, an interesting pattern of regional differences in current management goals and approaches occurs (Table 4). Whereas flood protection is the top priority in floodplain management in the Netherlands, Ireland, and Hungary, the focus is set on navigation in Germany, while Slovakia and Ukraine seem to have a more mixed agenda. MFM seems to be possible under all three strategies but it is showing differences in size and number of projects, which is mainly linked to the particular management structure for water in the countries, ranging from centralized national responsibility in the Netherlands and Hungary to provincial governance in Germany and Ireland and a rather mixed situation in Slovakia and the Ukraine (Table 4). In the Netherlands the approach based on the development of networks of natural areas resulted in a network of wetlands, riverine forests and natural grasslands. This has also an important scale effect, in that the areas together, the ecological network, allows for the (re-)establishment of wildlife populations. The ecological network is therefore essential in realizing sufficient habitat for wildlife populations. This was achieved through the cooperation between the Ministry and environmental research institutes, but also through funding mechanisms from the Provinces and mineral extraction industries. Regarding the management approaches, there is a compelling common set of measures all over Europe, targeting not only the restoration of hydrological connectivity at different scales, but also the adaptation and extensification of land use in flood plains as a precautionary principle.

Multifunctional floodplain management and biodiversity

According to our assessments, biodiversity decreased significantly due to conventional river regulations during the last two centuries, but has been positively affected by recent restoration efforts in the investigated countries. The main pressure for floodplain biodiversity is still the alteration of hydrological conditions, but also alien species, agriculture and forestry, water pollution and eutrophication, settlements and industrial infrastructure, soil pollution, and hydropower have important impacts across the six investigated countries. Biodiversity may benefit from multifunctional management, but evidence is rare as only few projects have documented the respective impacts and responses. Supported by the situation in Ireland, Germany, Hungary, and the Ukraine, the general impression is that a systematic scientific evaluation of the impacts of multifunctional floodplain management is lacking much too often. MFM projects with particular focus on the conservation of biodiversity should imply comprehensive evaluations of biodiversity impacts at habitat and species level (Jähnig et al. 2010). Restoration measures addressing relatively short river sections mainly improve habitat diversity of rivers and floodplains, but are often insufficient for changes in benthic invertebrate communities (Jähnig et al. 2010). It has been shown that plant diversity is crucial for ecosystem service supply (Isbell et al. 2011) and that biodiversity-rich natural or semi-natural floodplain habitats provide more ecosystem services than cultivated land use types (Felipe-Lucia and Comín 2015). As a consequence, biodiversity conservation must be a primary focus of sustainable MFM approaches. In Slovakia, for instance, the biodiversity effects of MFM are positive in protected floodplains with restricted management or management anchored in legislative acts. Here evidence of biodiversity effects is rather well documented and the creation and restoration of wet grasslands has become increasingly important following alarming biotope declines in many countries (José et al. 1999; Machar 2008). However, for small rivers and brooks outside protected areas that are managed within the local municipalities, decisions often fail to consider biodiversity, leading to high levels of pollution. For large rivers, particularly the Danube, Morava and Váh, conflicts among stakeholders in favour of hydropower production and dyke construction versus nature conservation are still ongoing. In the investigated countries, there is particularly little evidence for biodiversity effects concerning the large number of mostly smaller projects. Effects of MFM projects should be assessed by evaluating temporal change in biodiversity but also in supply (and demand) of all relevant ecosystem services (Felipe-Lucia and Comín 2015). When lacking quantitative data, expert knowledge can provide an alternative for such assessments (cf. Schindler et al. 2014). However, lack of thorough evaluation does not equal lack of important positive impacts. For many MFM projects, knowledge gaps must be interpreted as meaning that no evidence of an impact was assessed or found, rather than as providing evidence of no impact.

Outlook

Despite some of the challenges outlined above, there is a window of opportunity to push forward the establishment of multifunctional floodplains due to the public attention generated by multiple, devastating floods in Europe in the last decade, which showed the failure of monofunctional approaches, and by the enhanced interest and take up of the concepts of ecosystem services and multifunctionality by recent policies (e.g. policies to support “Green Infrastructure” across Europe; EC 2011; EEA 2015). The identification of suitable means how the interests of water and wetlands can be mainstreamed into decision making is supported by the “TEEB For Water and Wetlands” launched in February 2013. MFM is clearly linked furthermore to the ideas of Ecosystem based Adaptation (building resilient ecosystems for better adaptation to flood risk or other consequences of climate change; EEA 2015) and also to the targets of the Green Economy. On a national level, processes linked to e.g. “TEEB For Water and Wetlands”, the Mapping and Assessment of Ecosystems and their Services in Europe (MAES) which is one of the key actions of the EU Biodiversity Strategy to 2020, Green Economy initiative, and Ecosystem based Adaptation to the impacts of climate change are often managed in parallel and the opportunity for synergies is seldom fully exploited. Synergies need to be explored and potential alliances of stakeholders actively supported.

Insights for ‘BiodiversityKnowledge’