Abstract

Coastal ecosystems are prone to multiple anthropogenic and natural stressors including eutrophication, acidification, and invasive species. While the growth of some macroalgae can be promoted by excessive nutrient loading and/or elevated pCO2, responses differ among species and ecosystems. Native to the western Pacific Ocean, the filamentous, turf-forming rhodophyte, Dasysiphonia japonica, appeared in estuaries of the northeastern Atlantic Ocean during the 1980s and the northwestern Atlantic Ocean during the late 2000s. Here, we report on the southernmost expansion of the D. japonica in North America and the effects of elevated nutrients and elevated pCO2 on the growth of D. japonica over an annual cycle in Long Island, New York, USA. Growth limitation of the macroalga varied seasonally. During winter and spring, when water temperatures were < 15 °C, growth was significantly enhanced by elevated pCO2 (p < 0.05). During summer and fall, when the water temperature was 15–24 °C, growth was significantly higher under elevated nutrient treatments (p < 0.05). When temperatures reached 28 °C, the macroalga grew poorly and was unaffected by nutrients or pCO2. The δ13C content of regional populations of D. japonica was −30‰, indicating the macroalga is an obligate CO2-user. This result, coupled with significantly increased growth under elevated pCO2 when temperatures were < 15 °C, indicates this macroalga is carbon-limited during colder months, when in situ pCO2 was significantly lower in Long Island estuaries compared to warmer months when estuaries are enriched in metabolically derived CO2. The δ15N content of this macroalga (9‰) indicated it utilized wastewater-derived N and its N limitation during warmer months coincided with lower concentrations of dissolved inorganic N in the water column. Given the stimulatory effect of nutrients on this macroalga and that eutrophication can promote seasonally elevated pCO2, this study suggests that eutrophic estuaries subject to peak annual temperatures < 28 °C may be particularly vulnerable to future invasions of D. japonica as ocean acidification intensifies. Conversely, nutrient reductions would serve as a management approach that would make coastal regions more resilient to invasions by this macroalga.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The continued anthropogenic delivery of carbon dioxide (CO2) into surface oceans is changing the carbonate chemistry of the ocean, yielding reductions in pH and CO32− levels and increases in CO2 and HCO3− levels (Meehl et al. 2007). Beyond the combustion of fossil fuels, eutrophication-enhanced microbial respiration can also be a strong regional source of CO2 and acidification that can result in the seasonal accumulation of respiratory CO2 to levels that can exceed end of century projections of pCO2 for the open ocean (> 1000 µatm; Cai et al. 2011; Melzner et al. 2013; Wallace et al. 2014). While ocean acidification can have negative consequences for calcifying organisms (Gazeau et al. 2007; Ries et al. 2009; Talmage and Gobler 2011; Young et al. 2019) elevated pCO2 can benefit some, but not all, photosynthetic organisms (Hattenrath-Lehmann et al. 2015; Koch et al. 2013; Palacios and Zimmerman 2007), such as macroalgae (Gao et al. 1993; Hepburn et al. 2011; Young and Gobler 2016; Young et al. 2018). However, elevated pCO2 may also benefit invasive macroalgae and provide them an advantage over their native counterparts (Hall-Spencer et al. 2008).

Invasive macroalgae can be a significant ecosystem threat. Invasive species often tolerate a wide range of abiotic conditions and may be less palatable to grazers than native species (Hayes and Barry 2008; Low et al. 2015; Theoharides and Dukes 2007). The filamentous, turf-forming rhodophyte Dasysiphonia (formerly Heterosiphonia) japonica (henceforth Dasysiphonia) is native to the western Pacific Ocean (Chihara 1970; Choi et al. 2009; Okamura 1936) but was introduced into European waters in 1984 (Sjøtun et al. 2008). Since then, this macroalga has spread throughout the eastern Atlantic Ocean from France north to Norway and Sweden (Husa et al. 2004; Lein 1999), south into the Mediterranean Sea (Sagerman et al. 2015; Sjøtun et al. 2008), and as far west as Scotland (Moore and Harries 2009; Supplementary Fig. S1). Following this introduction, the macroalga spread to the western Atlantic Ocean. In North America, the macroalga has been found as far south as Rhode Island and eastern Long Island Sound (USA) (Newton et al. 2013; Ramsay-Newton et al. 2017; Schneider 2010) and as far north as Maine and Nova Scotia, Canada (Idlebrook 2012; Savoie and Saunders 2013; Supplementary Fig. S1). While the species appears to be a cold-water alga, Bjærke and Rueness (2004) found that the macroalga’s temperature range for growth is 0–30 °C and that the optimal temperature for growth is 19–25 °C. Given this, it is possible this macroalga will continue to invade the North American East Coast (Bjærke and Rueness 2004). The role of anthropogenic processes, including ocean acidification and nutrient loading, in facilitating the spread of Dasysiphonia, is unknown.

Excessive nutrient loading can promote the overgrowth of larger indigenous macroalgae (Conley et al. 2009; Valiela et al. 1997) by smaller morphologically simpler species that are capable of rapid growth in the presence of high nutrient concentrations and have a high assimilative capacity for nutrients (Neori et al. 2003; Valiela et al. 1997). Despite the great diversity of macroalgae, eutrophic conditions often lead to dominance by opportunistic chlorophytes and several branching or filamentous genera of rhodophytes such as Gracilaria (Valiela et al. 1997). To date, it has been generally concluded that such macroalgae can dominate estuaries with high nutrient loads and shorter residence times due to their ability to attach to the benthos and form dense beds (MacIntyre et al. 2004; Valiela et al. 1997). The extent to which invasions of Dasysiphonia are related to eutrophication is presently unknown.

Beyond nutrients, elevated pCO2 has been shown to benefit multiple marine macroalgae, including a variety of non-calcifying chlorophytes (Björk et al. 1993; Holmer et al. 2005; Olischläger et al. 2013; Young and Gobler 2016), phaeophytes (Hepburn et al. 2011), and rhodophytes (Gao et al. 1993; Hofmann et al. 2012; Xu et al. 2010). Of these three divisions, Rhodophyta has the largest number of species that are obligate CO2 users with a high affinity for CO2 and thus may respond more positively as CO2 levels increase compared to species that rely exclusively on HCO3− or use both forms of inorganic carbon (Badger et al. 1998; Johnson et al. 1992; Koch et al. 2013). The extent to which a macroalga may benefit from elevated pCO2 is partly dependent on whether inorganic uptake of the macroalga is substrate-saturated at modern day pCO2 levels (Koch et al. 2013). To date, no study has explored the effects of elevated pCO2 on the growth of Dasysiphonia.

The objective of this study was to assess how elevated nutrients and pCO2 levels may individually and collectively affect the growth rate of the invasive rhodophyte Dasysiphonia for the entirety of its growing season (Newton et al. 2013; Ramsay-Newton et al. 2017; Schneider 2010). Surveys of Dasysiphonia were performed across the south shore of Long Island (New York, USA) during which δ13C and δ15N content of macroalgal tissue were quantified to evaluate C and N sources. Laboratory experiments were performed monthly over an annual cycle, exposing the macroalga to ambient and elevated pCO2 levels with and without nutrient enrichment with each experiment performed at ambient water temperatures (4–28 °C). Given the invasive nature of Dasysiphonia, further experiments were performed to assess the growth response of co-occurring native macroalgae to elevated pCO2 and nutrients in both the presence and absence of Dasysiphonia (details below). For those experiments, the foliose rhodophyte Porphyra purpurea (henchforth Porphyra) and cylindrical, branching rhodophyte Agardhiella subulata (henchforth Agardhiella) were examined. Both species are common in estuaries across Long Island (Pedersen et al. 2008; Stewart Van Patten and Yarish 2009; Tang et al. 2015). For all experiments, growth rates, δ13C signatures, and elemental composition were evaluated and analyzed.

Methods

Experimental design and set-up

During spring, summer, and fall 2018, and winter 2019, ten experiments were performed to assess the effects of elevated pCO2, nutrients, and temperature on the growth rates of Dasysiphonia. All experiments were performed following previously published methods (Young and Gobler 2016, 2017; Young et al. 2018) in 1-L polycarbonate vessels, which were acid-washed (10% HCl) and liberally rinsed with deionized water prior to use. Seven parallel experiments were performed with Porphyra during summer and fall 2018. Vessels were placed in an environmental control chamber set to a constant temperature consistent with ambient water temperatures (4–28 °C), light intensity (~ 250 µmol photons m−2 s−1), and duration (i.e. light: dark cycle) at the macroalgal collection site. The light intensity and temperature measurements were made with a LI-COR LI-1500 light sensor logger and a YSI Pro Series sonde at collections sites (see below) and were obtained via regional monitoring buoys. Vessels were filled with filtered (0.2 µm polysulfone filter capsule, Pall©) seawater collected from the macroalgal collection sites and were randomly assigned, in quadruplicate, to one of four treatments: a control with ambient pCO2 (~ 400 µatm) and ambient nutrients (~ 1–5 µM nitrate, ~ 0.1–1 µM phosphate), a treatment with ambient pCO2 and elevated nutrients (50 µM nitrate, 3 µM phosphate), a treatment with elevated pCO2 (~ 1800 µatm) without nutrient additions, and a treatment with elevated pCO2 (~ 1,800 µatm) and elevated nutrients (50 µM nitrate, 3 µM phosphate), resulting in 16 experimental vessels per experiment. The pCO2 and nutrient levels used during experiments were within the range of levels of US East Coast estuaries (Baumann and Smith 2017; Baumann et al. 2015; Wallace et al. 2014; Wallace and Gobler 2015) and were used during prior experiments that involved macroalgae from Shinnecock Bay, New York, USA (Young and Gobler 2016, 2017; Young et al. 2018).

A 3.8 × 1.3 cm air diffuser (Pentair) connected with Tygon tubing to 1-mL polystyrene serological pipettes inserted into the bottom of each vessel was used to deliver dissolved gases to vessels. Vessels were subjected to ambient (400 µatm) and elevated (~ 2000 µatm) pCO2 via a gas proportionator system (Cole Parmer® flowmeter system, multi-tube frame) that mixed ambient air from an air source with 5% CO2 gas (Talmage and Gobler 2010). Gases were mixed and delivered at a flow rate of 2500 ± 5 mL min−1, which turned over the volume of the vessels > 1,000 times daily. Bubbling was initiated 2–3 days prior to the beginning of each experiment to allow pCO2 levels and pH to reach a state of equilibrium. All experiments lasted approximately one week, a duration consistent with prior studies that yielded significant changes in the growth of macroalgae (Young and Gobler 2016, 2017). Measurements of pH within experimental vessels were made daily with a Honeywell Durafet III ion-sensitive field-effect transistor-based (ISFET) solid-state pH sensor (± 0.01 pH unit, pH unit, total scale), which was calibrated with a seawater pH standard (Dickson 1993). Measurements of pH made with the Durafet were compared to measurements made spectrophotometrically using m-cresol purple (Dickson et al. 2007) and were found to be nearly identical and never significantly different.

Discrete seawater samples were collected at the beginning and conclusion of all experiments to directly measure DIC within each experimental vessel in each treatment (n = 4 per treatment). DIC samples were preserved using a saturated mercuric chloride (HgCl2) solution and stored at ~ 4 °C until analysis. DIC samples were analyzed by a VINDTA 3-D (versatile instrument for the determination of total inorganic carbon) delivery system coupled with a UIC Inc. coulometer (model CM5017O) as per Young and Gobler (2018). Final total alkalinity, pCO2, and levels of HCO3− (Supplementary Table S1) were calculated from measured DIC levels, pH, temperature, and salinity, as well as the first and second dissociation constants of carbonic acid in seawater (Millero 2010) using the program CO2SYS (http://cdiac.ess-dive.lbl.gov/ftp/co2sys/, last access: 23-November-2019). For quality assurance, DIC levels and pH within certified reference material (provided by Andrew Dickson of the University of California, San Diego, Scripps Institution of Oceanography; batches 159 and 173 = 2027.14 and 2042.41 µmol DIC kg seawater−1, respectively) were measured during analyses of every set of samples. The analysis of samples only continued after complete recovery (99.8 ± 0.2%) of certified reference material was attained. Actual mean pH and pCO2 were 7.99 and 408 µatm, respectively, for ambient conditions, and 7.36 and 1860 µatm, respectively, for elevated pCO2 conditions. These values were within the range found seasonally in some estuarine environments (Baumann and Smith 2017; Baumann et al. 2015; Wallace et al. 2014; Wallace and Gobler 2015).

Assessing the effects of elevated pCO 2 and nutrient levels on Dasysiphonia and Porphyra

Dasysiphonia and Porphyra were collected from a shallow-water (depths of 1–2 m) area in Great South Bay, New York, USA (Fig. 1; 40.73° N, −73.05° W) during low tide. All macroalgae collected were found growing subtidally. 20-L carboys were used to collect water from the collection sites. Large, well-pigmented, robust fronds of Dasysiphonia and Porphyra were collected, placed in coolers of seawater from the collection site, and transported to the Stony Brook Southampton Marine Science Center within 30 min of collection. Identification of macroalgae was based on morphology, microscopy, and known biogeography. Dasysiphonia is a common, but non-native species of red macroalgae along the North American east coast including around Long Island (Newton et al. 2013; Ramsay-Newton et al. 2017; Schneider 2010). Porphyra is a common species of rhodophyte in estuaries across Long Island (Pedersen et al. 2008; Stewart Van Patten and Yarish 2009; Tang et al. 2015). While Dasysiphonia is present most of the year in NY coastal waters, Porphyra is present seasonally during warmer months. Hence, experiments for Dasysiphonia were performed February through November, whereas Porphyra experiment were performed May through November. Pieces approximately 5 cm in length were cut from larger thalli, rinsed in filtered (0.2 µm) seawater and placed in a salad spinner to remove debris and epiphytes. They were then extensively rinsed with filtered seawater before being spun again to further remove any debris, epiphytes, and excess seawater (Young and Gobler 2016). Additional samples of were cut, cleaned, rinsed, and spun as described, and frozen for later analyses (see below). From the 5-cm pieces of thalli, a sub-sample was removed and weighed on a Scientech ZSA-120 digital microbalance (± 0.0001 g) to obtain initial wet weights which were typically ~ 1 g. All samples were kept in 100-mL filtered seawater after cleaning and weighing to prevent desiccation prior to introduction to experiments.

Maps of Great South Bay and Shinnecock Bay, NY, USA. Numbers represent shallow-water regions where collections of 1) Dasysiphonia japonica and Porphyra purpurea for March 2018 through February 2019 experiments, and 2) Dasysiphonia japonica and Agardhiella subulata for the October 2019 experiment. All maps were generated using ArcMap (Version 10.6) (Esri)

Experiments began with the introduction of macroalgae and nutrients into vessels that had been bubbling at the desired pCO2 levels for several days as described above. Vessels were monitored daily for one week during the experiment as described above. Periodic light measurements were made using a LI-COR LI-1500 light sensor logger and HOBO pendant temperature and light data loggers. At the conclusion of experiments, final pH and temperature measurements were made and a final DIC sample from each bottle was analyzed as described above. Macroalgae samples were removed from their respective vessels and rinsed, spun, re-rinsed, re-spun, and weighed as described above. After being weighed, samples were placed into small freezer bags for further analysis. Weight-based growth rates for all species were determined using the relative growth rate formula (growth d−1) = (ln Wfinal–ln Winitial)/(Δt), where Wfinal and Winitial are the final and initial weights in grams and Δt is the duration of the experiment in days. Normality and equal variance of growth rates were assessed via the use of Shapiro–Wilk and Leven tests; assumptions of equal variance and normality were met for all data. Differences in the growth rates of Dasysiphonia or Porphyra under ambient and elevated pCO2 and nutrients were assessed via two-way ANOVAs performed using SigmaPlot 11.0 for which the main treatment effects were pCO2 (ambient or elevated) and nutrients (ambient or elevated). For comparison of growth rates between Dasysiphonia and Porphyra, Tukey Honest Difference (Tukey HSD) tests using R 3.4.0 within 1.0.143 were performed.

Assessing the effects of elevated pCO 2 and nutrients, and competition

A final laboratory experiment was performed to assess the effects of competition and elevated pCO2 and nutrients on the growth of Dasysiphonia and Agardhiella. Identification of macroalgae was based on morphology, microscopy, and known biogeography. Dasysiphonia and Agardhiella were collected during low tide from a shallow-water (depths of 1–2 m) area in Shinnecock Bay, New York, USA (Fig. 1; 40.85° N, −72.50° W) and prepared in the same manner described above. All macroalgae collected were found growing subtidally. The experiment was performed in 1-L polycarbonate vessels in an environmental control chamber as described above. Containers were randomly assigned, in quadruplicate, to one of six treatments: two controls with ambient pCO2 (~ 400 µatm) and ambient nutrients (1 µM nitrate, 0.5 µM phosphate) that received either Agardhiella or Dasysiphonia, a treatment with ambient pCO2 and nutrients that received Agardhiella and Dasysiphonia, and three treatments with elevated pCO2 (~ 1,800 µatm) with daily nutrient additions (20 µM nitrate, 1.2 µM phosphate) that received either Agardhiella only, Dasysiphonia only, or Agardhiella and Dasysiphonia, resulting in 24 experimental units. This level of nutrient addition (20 µM N added daily over six days = 120 µM) is slightly more than twice what was used in the single species experiment (50 µM) to accommodate for the biomass of macroalgae that was twice the level of the single alga experiments (1 v 2 g). Nutrient concentrations were consistent with those observed in waterbodies around Long Island, New York (NY), and with Redfield stoichiometry (Gobler et al. 2006; Wallace and Gobler 2015). As described above, (1) experiments began with the introduction of macroalgae and nutrients into experimental vessels that had been bubbling at the desired pCO2 levels for several days as described above. Vessels were monitored daily for one week during the experiment; (2) final pH and temperature measurements were made and a final DIC sample from each vessel was analyzed; (3) macroalgae samples were removed from their respective vessels and rinsed, spun, re-rinsed, re-spun, weighed, and placed into small freezer bags for further analysis; (4) Weight-based growth rates for all species were determined using the relative growth rate formula and differences among growth rates were statistically evaluated.

Pre- and post-experimental analyses

For carbon (C), nitrogen (N), δ15N, and δ13C analyses, frozen samples of Dasysiphonia from March 2018 through February 2019 experiments were dried at 60 °C for 48 h and then homogenized into a fine powder using a mortar and pestle. Tissue C, N, δ15N, and δ13C were analyzed using an elemental analyzer interfaced to a Europa 20–20 isotope ratio mass spectrometer at the UC Davis Stable Isotope Facility. For comparison to Dasysiphonia, samples of Fucus vesiculosus, Gracilaria tikvahiae, Porphyra purpurea, Saccharina latissima, and Ulva rigida were collected from Shinnecock Bay, where Dasysiphonia co-occurs during the same period in which the macroalga was collected, and prepared for analysis of δ13C as described above. These species are common and native to Long Island (Stewart Van Patten and Yarish 2009; Wallace and Gobler 2015). Differences in tissue content of Dasysiphonia among treatments were statistically evaluated as described above. For all experiments involving Dasysiphonia, concentrations of nitrate (NO3−), phosphate (PO43−), and ammonium (NH4+) within experimental vessels, 20 mL of seawater was removed from each vessel and filtered by passing the seawater through pre-combusted (4 h at 450 °C) glass fiber filters (GF/F, 0.7-µm pore size) at the beginning and at the end of the experiments. The filtrate was frozen in 20 mL acid-washed scintillation vials for future analysis. A QuikChem 8500 (Lachat Instruments) flow injection analysis system was used to analyze the filtrate colormetrically to measure NO3−, PO43−, and NH3 (Parsons 2013). Initial, ambient concentrations of NO3−, PO43−, and NH3 were 2.65, 0.95, and 0.35 µM, respectively, and final concentrations of NO3−, PO43−, and NH3 were 0.66, 1.18, and 0.60 µM, respectively, with no significant differences in concentrations between ambient or elevated pCO2 or nutrient treatments.

Field surveys of Dasysiphonia

During October and November 2019, field surveys for Dasysiphonia were conducted along the south shore of Long Island, NY (Fig. 1). A total of 32 land-accessible sites were sampled in Great South Bay, Moriches Bay, Narrow Bay, Quantuck Bay, Shinnecock Bay, and Peconic Bay, NY. Identification of macroalgae was based on morphology and microscopy. The morphology and pigmentation of macroalgal fronds used in this study were fully consistent with prior descriptions of the macroalgae in the region (Newton et al. 2013; Ramsay-Newton et al. 2017; Schneider 2010). Upon arrival at each site, a 100-m transect was performed parallel to the shore. When Dasysiphonia was found, large, well-pigmented fronds were collected, placed in 50-mL centrifuge tubes in a cooler, and transported to the laboratory where they were examined microscopically and subsequently frozen for further analysis. The samples were dried at 60 °C for 48 h and then homogenized into a fine powder using a mortar and pestle. Tissue δ13C and δ15N was analyzed at the UC Davis Stable Isotope Facility as described above.

Results

Response of Dasysiphonia to elevated nutrients and/or pCO 2

Growth rates of Dasysiphonia were responsive to pCO2 levels during experiments performed in winter, spring and fall (February, March, April, October, and November), where a higher level of pCO2 significantly increased growth relative to ambient pCO2 treatments regardless of nutrient concentrations (Two-way ANOVA; p < 0.05; Fig. 2; Supplementary Table S2). For those experiments, growth rates of Dasysiphonia were ~ 60% higher when it was exposed to elevated pCO2 compared to ambient conditions (Fig. 2). Across all experiments, growth rates of Dasysiphonia were 26% higher under elevated pCO2 treatments compared to ambient treatments (Fig. 2). During late spring and summer experiments, growth was not significantly affected by elevated pCO2 as a single factor (Two-way ANOVA; p > 0.05; Fig. 2; Supplementary Table S2). Furthermore, for seven of ten experiments, growth rates of Dasysiphonia were significantly higher when exposed to elevated nutrient concentrations, regardless of pCO2 level (Two-way ANOVA; p < 0.05; Fig. 2; Supplementary Table S2) with the exceptions being during April, August, and February (Two-way ANOVA; p > 0.05; Fig. 2; Supplementary Table S2). When exposed to elevated nutrient levels, Dasysiphonia growth rates were 40% and ~ 25% higher in ambient and elevated pCO2 treatments, respectively (Fig. 2). There were no significant interactions between levels of pCO2 and nutrients during experiments (Two-way ANOVA; p > 0.05; Fig. 2; Supplementary Table S2), except for the May experiment when neither pCO2 nor nutrients alone altered growth rates but the combination of elevated pCO2 and nutrient levels synergistically increased the growth of Dasysiphonia by 30% relative to the control (Two-way ANOVA; p < 0.05; Fig. 2; Supplementary Table S2). The August experiment, when water temperatures were ~ 28 °C, was unique in that Dasysiphonia had negative growth rates across all treatments and was not significantly affected by elevated pCO2 or nutrient levels (Two-way ANOVA; p > 0.05; Fig. 2; Supplementary Table S2).

Growth rates of Dasysiphonia japonica exposed to ambient and elevated pCO2 with and without nutrient additions for March 2018 through February 2019 experiments. Columns represent means ± standard error. Temperatures represent means ± standard deviation for all treatments. Two-way ANOVA performed with significant differences (p < 0.05) in main treatment effects, (CO2 and Nutrients, abbreviated as N + P), appearing at the top right of each panel

The δ13C content of Dasysiphonia was significantly lower when exposed to elevated pCO2 (−43.4‰) compared to control conditions (-31.7‰; Two-way ANOVA; p < 0.05; Fig. 3; Supplementary Table S3). In contrast, there was no difference in δ13C content when Dasysiphonia was exposed to elevated nutrients for any experiment (Two-way ANOVA; p > 0.05; Fig. 3; Supplementary Table S3). The tissue C content of Dasysiphonia was not significantly altered by elevated pCO2 or nutrient conditions across all experiments (Two-way ANOVA; p > 0.05; Fig. 4; Supplementary Table S4). Tissue N content was not significantly changed by pCO2 (Two-way ANOVA; p > 0.05; Fig. 5; Supplementary Table S5) but was significantly higher under elevated nutrient conditions (p < 0.05) in experiments performed from April through September (Fig. 5). For April through September experiments, average tissue N content of Dasysiphonia under elevated nutrients was 12% and ~ 16% higher under ambient and elevated pCO2, respectively (Fig. 5). Furthermore, C:N ratios of Dasysiphonia were significantly lower when exposed to elevated nutrients for April through July and November to February experiments (Two-way ANOVA; p < 0.05; Fig. 6; Supplementary Table S5). The average tissue C:N ratio of Dasysiphonia was 10% and ~ 18% lower under elevated nutrient levels in ambient and elevated pCO2 treatments, respectively (Fig. 6). Tissue C:N ratios were unaffected by elevated pCO2 levels (Two-way ANOVA; p > 0.05; Fig. 6; Supplementary Table S6) except for the May and July experiments when tissue C:N ratios were significantly higher under elevated pCO2 (Two-way ANOVA; p < 0.05; Fig. 6; Supplementary Table S6).

Tissue δ13C content of Dasysiphonia japonica exposed to ambient and elevated pCO2 levels with and without nutrient additions for March 2018 through February 2019 experiments. Columns represent means ± standard deviation. Two-way ANOVA performed with significant differences (p < 0.05) in main treatment effects, (CO2 and Nutrients, abbreviated as N + P), appearing at the top right of each panel

Tissue carbon content of Dasysiphonia japonica exposed to ambient and elevated pCO2 levels with and without nutrient additions for March 2018 through February 2019 experiments. Columns represent means ± standard deviation. Two-way ANOVA performed with significant differences (p < 0.05) in main treatment effects, (CO2 and Nutrients, abbreviated as N + P), appearing at the top right of each panel

Tissue nitrogen content of Dasysiphonia japonica exposed to ambient and elevated pCO2 levels with and without nutrient additions for March 2018 through February 2019 experiments. Columns represent means ± standard deviation. Two-way ANOVA performed with significant differences (p < 0.05) in main treatment effects, (CO2 and Nutrients, abbreviated as N + P), appearing at the top right of each panel

Tissue C:N ratios of Dasysiphonia japonica exposed to ambient and elevated pCO2 levels with and without nutrient additions for March 2018 through February 2019 experiments. Columns represent means ± standard deviation. Two-way ANOVA performed with significant differences (p < 0.05) in main treatment effects, (CO2 and Nutrients, abbreviated as N + P), appearing at the top right of each panel

Response of Porphyra to elevated nutrients and/or pCO 2 and comparison to Dasysiphonia

Porphyra growth rates was rarely or never responsive to pCO2 levels and nutrient additions, respectively (Two-way ANOVA; p > 0.05; Fig. 7; Supplementary Table S7). Of the seven experiments performed, Porphyra only grew faster in response to elevated pCO2 during the July and August experiments (Two-way ANOVA; p < 0.05 for both; Fig. 7; Supplementary Table S7).

Growth rates of Porphyra purpurea exposed to ambient and elevated pCO2 with and without nutrient additions for May through November 2018 experiments. Columns represent means ± standard deviation. Temperatures represent means ± standard deviation for all treatments. Two-way ANOVA performed with significant differences (p < 0.05) in main treatment effects, (CO2 and Nutrients, abbreviated as N + P), appearing at the top right of each panel

When comparing the growth of Dasysiphonia to Porphyra, there were several significant differences among treatments and seasons. For spring experiments, Dasysiphonia growth was 13-fold and significantly higher than that of Porphyra in all treatments, regardless of pCO2 or nutrient level (Tukey HSD; p < 0.05 for all; Supplementary Table S8). During the summer experiments, Dasysiphonia growth was 40% higher than that of Porphyra and significantly higher in ambient pCO2 treatments and treatments that received nutrient additions as well as when all treatments were combined (Tukey HSD; p < 0.05 for all; Supplementary Table S8). For the fall experiments, Dasysiphonia growth rates were significantly higher than Porphyra in the ambient pCO2 treatment that received nutrient additions (Tukey HSD; p < 0.05; Supplementary Table S8) whereas Porphyra growth was significantly higher than that of Dasysiphonia in ambient pCO2 treatments that did not receive nutrient additions, (Tukey HSD; p < 0.05 for all; Supplementary Table S8). Overall, during the fall, Porphyra growth was ~ 70% higher than that of Dasysiphonia (Figs. 2 and 7).

Competition of Agardhiella and Dasysiphonia under ambient and elevated nutrients and/or pC O 2

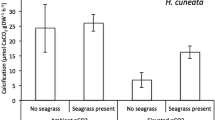

There were differing growth responses for Agardhiella and Dasysiphonia exposed to combined elevated pCO2 and nutrients. Agardhiella growth rates were not significantly altered by elevated pCO2 and nutrient levels or by competition with Dasysiphonia (Two-way ANOVA; p > 0.05; Fig. 8; Supplementary Table S9). In contrast, Dasysiphonia growth rates were ~ 120% higher under elevated pCO2 and nutrients (Two-way ANOVA; p < 0.05; Fig. 8; Supplementary Table S9) but were unaffected by competition with Agardhiella (Two-way ANOVA; p > 0.05; Supplementary Table S9). While growth rates of Dasysiphonia and Agardhiella were similar under ambient levels of nutrients and pCO2, the growth rates of Dasysiphonia were three times greater than Agardhiella under elevated levels of nutrients and pCO2 (Two-way ANOVA; p < 0.05; Fig. 8; Supplementary Table S9).

Growth rates of Agardhiella subulata and Dasysiphonia japonica exposed to ambient and elevated CO2 and nutrient conditions, with and without competition from the other macroalga for the October 2019 experiment. Columns represent means ± standard deviation. Two-way ANOVA performed with significant differences (p < 0.05) in main treatment effects, (CO2 and Nutrients, abbreviated as N + P), for each species appearing at the top left of the panel

Field surveys of Dasysiphonia across the south shore of Long Island

The field surveys of the southern shore of Long Island revealed that Dasysiphonia was widespread across the area. The macroalga was present at 24 of 32 sites (Fig. 9; Supplementary Table S10) including all 15 sites in Great South Bay, two sites in Narrow Bay, and two sites in western Moriches Bay. It was absent from eastern Moriches Bay, Quantuck Bay, and western Shinnecock Bay but was present at all four sites across eastern Shinnecock Bay and the single site in the southern section of Great Peconic Bay (Fig. 9; Supplementary Table S10). In Great South Bay, Dasysiphonia δ15N signatures varied by site, with no noticeable trends across the bay. Signatures of δ15N in Great South Bay ranged from 6.4 to 11.7‰ (sites 1–15; Fig. 10; Supplementary Table S10). In Narrow Bay, the average δ15N signature for Dasysiphonia was ~ 10‰, while the Mastic Beach and Center Moriches sites in Moriches Bay (sites 18 and 19, respectively) were 10.6 and 7.5‰, respectively (Fig. 10; Supplementary Table S10). The sole site in Peconic Bay (site 27) had a δ15N signature of 8.6‰. For eastern Shinnecock Bay, Dasysiphonia in the northern sites (Ponquogue Bridge and Shinnecock Hills, sites 28 and 29, respectively) had δ15N values of ~ 10‰ while macroalgae from the southern sites (Shinnecock Inlet, sites 30 and 31) had δ15N values of ~ 8‰ (Fig. 10; Supplementary Table S10). The overall minimum, maximum, and average δ15N content of Dasysiphonia was 6.4, 11.7, and 9.1‰, respectively (Fig. 10; Supplementary Table S10).

Discussion

Given that the growth of Dasysiphonia generally increased when exposed to elevated pCO2 and nutrient levels in contrast to indigenous macroalgae, this study provides insight regarding the factors driving invasions of this macroalga. During this study, elevated pCO2 was found to significantly enhance the growth rates of the invasive red macroalga Dasysiphonia during experiments performed when water temperatures were at or below 15 °C. In contrast, elevated nutrient concentrations significantly increased growth rates during experiments across a wider range of temperatures (4–23 °C). Tissue N and C:N content were significantly increased and decreased, respectively, when Dasysiphonia was exposed to elevated nutrient concentrations. The growth rates of Dasysiphonia were generally greater than those of two other indigenous macroalgae, especially when levels of nutrients and pCO2 were elevated. The δ13C and δ15N of this macroalga indicated that it relied on CO2 and wastewater-derived N for in situ growth.

The response of macroalgae to pCO2 levels may depend on their mode of C acquisition as well as the extent to which inorganic carbon uptake of the organism is substrate-saturated at current pCO2 levels (Badger 2003; Koch et al. 2013). When exposed to elevated pCO2, macroalgae may downregulate their carbon concentrating mechanisms (CCMs) that convert HCO3− to CO2, allowing more energy to be available for processes such as vegetative growth (Björk et al. 1993; Cornwall et al. 2012; Koch et al. 2013). Values of δ13C are often used to assess the types of inorganic carbon used by macroalgae for photosynthesis, with a δ13C signature of −10‰ being indictive of HCO3− use and signatures of -30‰ or lower characteristic of diffusive uptake of CO2 (Bricelj et al. 2001; Hepburn et al. 2011; Maberly et al. 1992; Raven et al. 2002). In the present study, Dasysiphonia had significantly lower δ13C signatures when exposed to experimentally elevated pCO2, evidencing uptake of the δ13C-enriched experimental CO2 source (Young and Gobler 2016). Furthermore, under ambient conditions, the δ13C signatures of Dasysiphonia were consistently at -30‰ or lower, a finding consistent with prior studies of this macroalga (Kang et al. 2008; Leclerc et al. 2013) and indicating that Dasysiphonia predominately uses CO2 for photosynthesis (Bricelj et al. 2001; Hepburn et al. 2011; Maberly et al. 1992; Raven et al. 2002). Rhodophytes are known to have a high affinity for CO2 and RuBisCO that minimizes CO2 loss from photorespiration despite not using HCO3− or having a CCM (Badger et al. 1998; Johnson et al. 1992; Koch et al. 2013). While not all rhodophytes may benefit from increased pCO2, (Britton et al. 2019; Koch et al. 2013), the results of the present study demonstrate that Dasysiphonia is likely not substrate-saturated at ambient pCO2 levels (~ 400 µatm) given the seasonally increased growth rates in response to elevated pCO2.

Dasysiphonia differs from many other macroalgal species that comprise the assemblages in the waters around New York, including Fucus vesiculosus, Gracilaria tikvahiae, Porphyra purpurea, Saccharina latissima, and Ulva rigida, which have δ13C signatures ranging from −12 to −18% (Young and Gobler 2016, 2017; Young et al. 2018; Fig. 11). This finding suggests that among all of these co-occurring macroalgae, Dasysiphonia is the most reliant on CO2 as a carbon source (Bricelj et al. 2001; Hepburn et al. 2011; Maberly et al. 1992; Raven et al. 2002) and may, therefore, be the most likely to benefit from higher pCO2 in coastal waters. In addition to the rapid rise in atmospheric pCO2 during the past half century (Meehl et al. 2007), it has become well recognized that eutrophication-enhanced organic-matter loading to coastal waters also causes seasonally elevated pCO2 (Cai et al. 2011; Melzner et al. 2013; Wallace et al. 2014). It seems plausible that high pCO2 levels seasonally present today in the coastal waters may be favoring the proliferation of Dasysiphonia over other macroalgae that are substrate-saturated at present pCO2 levels or are unable to utilize CO2 for photosynthesis under acidified conditions (Cornwall et al. 2012; Koch et al. 2013).

The δ13C content of various species of macroalgae (Dasysiphonia japonica, Fucus vesiculosus, Gracilaria tikvahiae, Porphyra purpurea, Saccharina latissima, and Ulva rigida) under ambient pCO2 levels without nutrient additions. Columns represent means ± standard deviation. Red dashed lines represent divisions in macroalgae that solely rely on HCO3− (0 to −10‰), can use both HCO3− and CO2 (−10 to −30‰), or solely rely on CO2 (−30‰ or less) for photosynthesis (Maberly et al. 1992; Bricelj et al. 2001; Raven et al. 2002; Hepburn et al. 2011)

Elevated nutrient concentrations significantly increased and decreased tissue N and C:N content, respectively, of Dasysiphonia, indicating that while both N and P were added during experiments, N was a critical element. Beyond these changes in N content relative to the control treatment, the absolute N content of Dasysiphonia usually increased to ≥ 0.03 g N per g tissue following nutrient additions, a level known to represent N saturation (Lyngby et al. 1999; Wallace and Gobler 2015). These trends align with growth rates in most experiments of the present study, where Dasysiphonia responded positively to elevated nutrient levels during most experiments. Dasysiphonia has been shown to have a high nitrate uptake efficiency consistent with rapid growth compared to native macroalgal species (Low et al. 2015). In the present study, while the presence of Dasysiphonia did not significantly affect the growth rates of a common native rhodophyte (Agardhiella) in ambient or elevated pCO2 and nutrient conditions, the former outgrew the latter by nearly two-fold when high levels of nutrients and pCO2 were present. Similarly, the growth rates of Dasysiphonia exceeded those of Porphyra during most seasons when nutrients and pCO2 levels were high. The filamentous morphology of Dasysiphonia affords it a surface-area-to-volume ratio greater than bladed and branching macroalgae and allows for a higher nutrient uptake capacity (Low et al. 2015; Rosenberg and Ramus 1984). These traits may allow Dasysiphonia to undergo rapid growth in eutrophic settings (Valiela et al. 1997; Wallace and Gobler 2015). Eutrophication can promote coastal ocean acidification due to the accumulation of respiratory CO2 due to microbial degradation of excessive organic matter, resulting in seasonal pCO2 levels (> 1000 µatm) not predicted to occur in open ocean regions for more than a century (Wallace et al. 2014). As such, eutrophication may promote seasonally-elevated pCO2 levels that may yield nutrient- and CO2-mediated enhanced growth of Dasysiphonia, a scenario that would make eutrophied estuaries more susceptible to invasion by the macroalga. Furthermore, given that climate change is expected to increase incidences of eutrophication in many estuaries due to increased precipitation-driven N loading (Sinha et al. 2017), these systems may become more susceptible to invasion by macroalgae such Dasysiphonia.

Seasonal response to nutrients and CO 2

The response of Dasysiphonia varied seasonally with CO2 responses being limited to cool water conditions, and nutrient effects present during warmer periods of the year with these changing responses being reflective of seasonal cycles in nutrients and acidification. For example, continuous measurements of pH in Great South Bay during this study, the collection site for Dasysiphonia, revealed pH values decreased from > 8.1 during early April to < 7.9 from May through September, and values > 8 during the fall (Fig. 12a). Given that values of pH and pCO2 are inversely related in oceans (Caldeira and Berner 1999; Marsh 2008; Martz et al. 2010) and Long Island estuaries (Baumann et al. 2015; Gobler and Baumann 2016; Wallace et al. 2014), these patterns in pH suggest in situ pCO2 levels were low during the colder months and higher during the warmer months of the study, a trend consistent with other studies in the region (Baumann et al. 2015; Gobler and Baumann 2016; Wallace et al. 2014). In contrast, concentrations of dissolved inorganic nitrogen (DIN) during this study revealed a steady decrease from ~ 4.0 µM in February to ~ 0.3 µM in May, low concentrations (0.4 ± 0.2 µM) throughout the summer before increasing to > 2.7 µM in the fall (SCDHS 2018; Fig. 12b). This trend is consistent with prior coastal studies showing nutrients drawn down by enhanced rates of productivity during warmer months (Carpenter and Dunham 1985; Glibert et al. 2007; Woodwell et al. 1979). Collectively, these seasonal patterns in nitrogenous nutrients and pH/CO2 align well with the experimental outcomes of this study. During the colder months (< 15 °C; February, March, April, October, and November), pH levels were higher and pCO2 levels were likely lower, and CO2 was likely a limiting resource for the growth of the obligate CO2-user, Dasysiphonia. During the warmer months, when pCO2 levels were higher but DIN concentrations levels were low, growth of Dasysiphonia was limited by N but not pCO2 levels. The only experiment that revealed co-limitation of nutrients and CO2 was during the transition month of May, when nutrients and CO2 combined to synergistically enhance the growth of Dasysiphonia. Lastly, the δ15N content of macroalgae is < 3‰ when utilizing N from fertilizer or atmospheric deposition, and > 3‰ when utilizing N from wastewater (Kang et al. 2015; Kendall and McDonnell 2012; Lapointe et al. 2004). Based on samples collected during field surveys of the present study, the δ15N content of Dasysiphonia across Long Island was up to ~ 12‰ and averaged ~ 9‰, indicating that wastewater was the primary source of N for the macroalga, an outcome consistent with the finding that wastewater supplies ~ 70% of the N to Long Island estuaries (Kinney and Valiela 2011). Given that N is often a limiting resource for macroalgae in estuaries (Valiela et al. 1997) and given the significantly higher growth rates of Dasysiphonia in the majority of experiments following N enrichment, it seems likely that while pCO2 levels can limit Dasysiphonia growth, N may be the more important resource.

a Daily and monthly pH values (total scale) obtained from a continuous monitoring buoy in Bellport Bay, NY (40.7533º, -72.9321º), b Monthly dissolved inorganic nitrogen (DIN) concentrations (µM) obtained from discrete monitoring at various locations in Great South Bay in 2018 by the Suffolk County Department of Health Services (SCDHS), and c Daily and monthly surface water temperatures obtained from the buoy in Bellport Bay

During this study, Dasysiphonia populations were observed in Great South Bay throughout the year, during which the macroalga was exposed to temperatures ranging from 0 °C to 28 °C (Fig. 12c). Dasysiphonia is an invasive species, in part, due to its ability to tolerate a wide temperature range (0 °C to 30 °C), although reduced growth and cellular damage can occur at temperatures exceeding 28 °C (Bjærke and Rueness 2004; Husa et al. 2004). This upper temperature limit is consistent with the present study, where negative growth rates occurred during the August experiment, when temperatures were ~ 28 °C. This is also consistent with continuous measurements of temperature in Great South Bay, with the highest daily temperatures (27–28 °C) occurring throughout August and the beginning of September (Fig. 12c). While Bjærke and Rueness (2004) found that the optimal temperature for growth of Dasysiphonia (as Heterosiphonia japonica) was 19–24 °C, in this study growth rates were similar across a wide range of seasonal experiments (4–24 °C), suggesting that the optimal temperature range for growth may be wider than previously thought. This difference may be, in part, because the current study sampled macroalgae from the field over a complete annual cycle, allowing for natural acclimation at the population or clonal level to in situ temperatures. Regardless, as water temperatures increase this century and some northern estuaries more regularly enter the 19–24 °C range, they may become vulnerable to invasion by Dasysiphonia. The upper temperature limit of Dasysiphonia in the present study and others (Bjærke and Rueness 2004) suggests that the timing of future invasions in areas south of Long Island may be limited to some, but not all, months of the year. Isotherms in the North Atlantic Ocean are expected to shift as much as 600 km northwards by the end of the twenty-first century (Hansen et al. 2006), with annual mean water temperatures increasing by 4 °C on rocky shores in the North Atlantic (Müller et al. 2009). This increase in temperature is expected to cause poleward shifts in pelagic and benthic communities, including macroalgal assemblages (Jueterbock et al. 2013; Southward et al. 1995; Wernberg et al. 2011). Considering the enhanced growth of Dasysiphonia under elevated pCO2 and nutrient levels (current study), the thermal tolerance of Dasysiphonia (Bjærke and Rueness 2004; Husa et al. 2004), and the higher levels of pCO2 at higher latitudes across North America (Gledhill et al. 2015), eutrophic estuaries of the northeast US and eastern Canada may be the most vulnerable to future invasion by Dasysiphonia. Given the ability of this macroalgae to persist at lower levels during the warmest month, invasions to the south of its southern-most site in the North Atlantic (Long Island, NY; this study) may also be possible.

Past, present, and future invasions of Dasysiphonia

Dasysiphonia is native to East Asian waters, where it occurs sporadically throughout the year and generally comprises a small fraction of macroalgal communities (Kang et al. 2008; Kim et al. 2008). Since the 1980s, the macroalga has spread throughout the eastern Atlantic Ocean (Moore and Harries 2009; Sagerman et al. 2015; Sjøtun et al. 2008; Supplementary Fig. S1), the US East Coast, (Idlebrook 2012) and Canada (Savoie and Saunders 2013). Schneider (2010) documented the macroalga’s presence in the waters around Rhode Island in 2007 but did not find the macroalga in the waters around Long Island. However, Newton et al. (2013) reported the presence of the macroalga in Long Island Sound in 2012 (Supplementary Fig. S1). As evident by the present study, the macroalga has continued its western North Atlantic invasion of more than two dozen sites across the south shore of Long Island since its first appearance in Long Island Sound, representing the southernmost observations of Dasysiphonia in North America.

Non-indigenous macroalgae can outcompete native species for space and with respect to growth and nutrient acquisition (Hayes and Barry 2008; Low et al. 2015; Theoharides and Dukes 2007). High levels of biomass of Dasysiphonia have been shown to exceed that of native species by an order of magnitude (Sagerman et al. 2014) and can lower native macroalgal species richness, evenness, and diversity (Low et al. 2015; Sagerman et al. 2014). In the present study, spring, and summer growth rates of Dasysiphonia exceeded those of Porphyra by as much as 13-fold and ~ 25%, respectively. Additionally, Dasysiphonia outgrew Agardhiella by ~ 70% under high nutrient and high pCO2 conditions. We note, however, that this experiment assessed interspecific competition but did not establish a control with double the levels of each seaweed individually to assess intraspecific competition (Underwood 1986). Ramsay-Newton et al. (2017) found that, following invasion of Dasysiphonia in Nahant, MA in 2011, there was a significant decline in macroalgal species richness. Introduced macroalgae such as Dasysiphonia can form dense mats that limit light availability and inhibit the recruitment and establishment of other macroalgae species, such as kelp (Ambrose and Nelson 1982; Britton-Simmons 2004). Dasysiphonia can occupy up to 80% available substrate and can grow epiphytically on other macroalgae (Moore and Harries 2009; Newton et al. 2013; Supplementary Fig. S2). The literature regarding management of Dasysiphonia is currently limited, but it appears that the most effective means of limiting invasions by the macroalga, and others, is prevention of introduction through means such as transoceanic shipping, aquaculture and aquarium trade, fishing/boating activities, and the opening of canals (Doelle et al. 2007; Mathieson et al. 2008; Mineur et al. 2014; Petrocelli et al. 2013; Sant et al. 1996; Vranken et al. 2018). Given the results of this study, it would seem efforts to reduce N loading to coastal waters may also reduce metabolic CO2 production, and may slow or reverse invasions of Dasysiphonia, thereby mitigating the negative effects of this macroalga on marine ecosystems. Reductions in N inputs to coastal ecosystems have been shown to reduce the frequency and intensity of harmful algal blooms (Heisler et al. 2008) caused by microalgae (Gobler et al. 2005; Nuzzi and Waters 2004), as well as macroalgae (Harlin 1995).

There are numerous ecosystem implications associated with the ability of nutrient loading and ocean acidification to promote invasions of Dasysiphonia. In the North Atlantic Ocean, the replacement of kelp beds with invasive species, such as Dasysiphonia, may alter the ecosystem services provided by kelp, such as a refuge from predation (Watanabe 1984). The ability of macroalgae to serve as refuge from predation can partly depend on the complexity of the macroalga’s thallus. The thalli of Dasysiphonia are complex and filamentous (O'Brien et al. 2018), which, in higher densities, can form a biogenically complex habitat capable of hosting some meso-invertebrates due to smaller interstitial volume and area compared to macroalgae with branched or blade morphology (Dijkstra et al. 2017; Holmlund et al. 1990; Veiga et al. 2014; Ware et al. 2019; Warfe et al. 2008). Dijkstra et al. (2017) found that invasive filamentous red macroalgae, such as Dasysiphonia, supported two to three times more meso-invertebrate individuals and species that form the base of food webs, which may benefit higher trophic levels. However, several studies have found that while cunner prefer to refuge in the tall, simple blades provided by kelp (Saccharina latissima), they will use turf macroalgae (i.e. Dasysiphonia) if kelp becomes scarce, although this is not preferred, as turf macroalgae do not provide as much protection from predation as kelp (Dijkstra et al. 2019; O’Brien et al. 2018). While Dasysiphonia may provide a suitable habitat for some organisms, its value as a food source could alter herbivore assemblages. Some herbivores avoid grazing on the invasive species (Low et al. 2015) and Sagerman et al. (2015) reported that Dasysiphonia (as Heterosiphonia japonica) is not a preferred food source for several common invertebrates, an outcome that may allow for continued proliferation of the macroalga. Given Dasysiphonia can grow epiphytically on other macroalgae (Moore and Harries 2009; Supplementary Fig. S2) and seagrass (García-Redondo et al. 2019), the further invasion, proliferation, and overgrowth of this macroalga in response to acidification and eutrophication could disrupt seaweed assemblages and/or seagrass beds due to decreased light availability (Valiela et al. 1997) and/or direct competition for nutrients (Duarte 1995; Young and Gobler 2017; Young et al. 2018). Macroalgal overgrowth can also smother benthic habitats and promote diel hypoxia/anoxia (Liu et al. 2009; Valiela and Cole 2002; Valiela et al. 1997). Lastly, the overgrowth of Dasysiphonia may be problematic for shellfisheries, as it can overgrow oysters (Haydar and Wolff 2011). A study by Glenn et al. (2020) found that within the Great Bay Estuary in New Hampshire, USA, 81% of all biomass on oyster farm gear consisted of non-native macroalgae, including Dasysiphonia, which may provide additional substrate for the macroalga to propagate.

In conclusion, the invasive red macroalga Dasysiphonia experienced enhanced growth compared to other red macroalgae when exposed to elevated pCO2 and nutrient levels. Based on the δ13C signatures of Dasysiphonia, the macroalga appears to predominately use CO2 as a source of carbon for photosynthesis, which may give it a competitive advantage over other macroalgae in high CO2 ecosystems. Its δ15N signatures suggest its growth is being promoted by excessive wastewater-derived N loading. Dasysiphonia has spread across estuaries of the northwestern and northeastern Atlantic Oceans since the 1980s. Given predicted trends in N loading, acidification, and warming of coastal ecosystems in the coming decades (Doney et al. 2009; Sinha et al. 2017), it may continue to spread into eutrophied estuaries further north and south due to its ability to rapidly grow under elevated pCO2 and nutrient conditions and its wide thermal tolerance.

References

Ambrose RF, Nelson BV (1982) Inhibition of giant kelp recruitment by an introduced brown alga. Bot Mar, 25(6):265–267.https://doi.org/10.1515/botm.1982.25.6.265

Badger M (2003) The role of carbonic anhydrases in photosynthetic CO2 concentrating mechanisms. Photosyn Res 77:83–94. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1025821717773

Badger MR, Andrews TJ, Whitney SM, Ludwig M, Yellowlees DC, Leggat W, Price GD (1998) The diversity and coevolution of Rubisco, plastids, pyrenoids, and chloroplast-based CO2-concentrating mechanisms in algae. Can J Bot 76:1052–1071. https://doi.org/10.1139/b98-074

Baumann H, Smith EM (2017) Quantifying metabolically driven pH and oxygen fluctuations in US nearshore habitats at diel to interannual time scales. Estuar Coast. https://doi.org/10.1007/s1223

Baumann H, Wallace RB, Tagliaferri T, Gobler CJ (2015) Large natural pH, CO2 and O2 fluctuations in a temperate tidal salt marsh on diel, seasonal, and interannual time scales. Estuar Coast 38:220–231. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12237-014-9800-y

Bjærke MR, Rueness J (2004) Effects of temperature and salinity on growth, reproduction and survival in the introduced red alga Heterosiphonia japonica (Ceramiales, Rhodophyta). Botanica Marina 47:373–380. https://doi.org/10.1515/BOT.2004.055

Björk M, Haglund K, Ramazanov Z, Pedersén M (1993) Inducible mechanisms for HCO3- utilization and repression of photorespiration in protoplasts and thalli of three species of Ulva (Chlorophyta). J Phycol 29:166–173. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0022-3646.1993.00166.x

Bricelj VS, MacQuarrie SP, Schaffner RA (2001) Differential effects of Aureococcus anophagefferens isolates (“brown tide”) in unialgal and mixed suspensions on bivalves feeding. Mar Biol 139:605–615

Britton D, Mundy CN, McGraw CM, Revill AT, Hurd CL (2019) Responses of seaweeds that use CO2 as their sole inorganic carbon source to ocean acidification: differential effects of fluctuating pH but little benefit of CO2 enrichment. ICES J Mar Sci. https://doi.org/10.1093/icesjms/fsz070

Britton-Simmons KH (2004) Direct and indirect effects of the introduced alga Sargassum muticum on benthic, subtidal communities of Washington State, USA. Mar Ecol-Prog Ser 277:61–78. https://doi.org/10.3354/meps277061

Cai W-J et al (2011) Acidification of subsurface coastal waters enhanced by eutrophication Nat Geosci 4:766–770. https://doi.org/10.1038/ngeo1297

Caldeira K, Berner R (1999) Seawater pH and atmospheric carbon dioxide. Science 286:2043. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.286.5447.2043a

Carpenter EJ, Dunham S (1985) Nitrogenous nutrient uptake, primary production, and species composition of phytoplankton in the Carmans River estuary, Long Island, New York. Limnol Oceanogr. https://doi.org/10.4319/lo.1985.30.3.0513

Chihara M (1970) Common seaweeds of Japan in color. Hoikusha Publishing Company, Osaka (in Japanese)

Choi CG, Oh SJ, Kang IJ (2009) Subtidal marine algal community of Jisepo in Geoge. Korea Journal of the Faculty of Agriculture, Kyushu University 55:39-45

Conley DJ et al (2009) Ecology controlling eutrophication: nitrogen and phosphorus. Science 323:1014–1015

Cornwall CE, Hepburn CD, Pritchard D, Currie KI, McGraw CM, Hunter KA, Hurd CL (2012) Carbon-use strategies in macroalgae: differential responses to lowered pH and implications for ocean acidification. J Phycol 48:137–144. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1529-8817.2011.01085.x

Dickson AG (1993) The measurement of sea water pH. Mar Chem 44:131–142. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-4203(93)90198-W

Dickson AG, Sabine CL, Christian JR (2007) Guide to best practices for ocean CO2 measurements PICES Special Publication 3:191

Dijkstra JA, Harris LG, Mello K, Litterer A, Wells C, Ware C (2017) Invasive seaweeds transform habitat structure and increase biodiversity of associated species. J Ecol 105:1668–1678. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2745.12775

Dijkstra JA, Litterer A, Mello K, O’Brien BS, Rzhanov Y (2019) Temperature, phenology, and turf macroalgae drive seascape change: connections to mid-trophic level species. Ecosphere 10(11):e02923. https://doi.org/10.1002/ecs2.2923

Doelle M, McConnell ML, Vanderzwaag DL (2007) Invasive seaweeds: global and regional law and policy responses. Bot Mar, 50:438–450. https://doi.org/10.1515/BOT.2007.046

Doney SC, Fabry VJ, Feely RA, Kleypas JA (2009) Ocean acidification: the other CO2 problem. Ann Rev Mar Sci 1:169–192. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.marine.010908.163834

Duarte CM (1995) Submerged aquatic vegetation in relation to different nutrient regimes. Ophelia 41:87–112. https://doi.org/10.1080/00785236.1995.10422039

Gao K, Aruga Y, Asada K, Kiyoharda M (1993) Influence of enhanced CO2 on growth and photosynthesis of the red algae Gracilaria sp. and G. chilensis. J Appl Phycol 5:563–571. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02184635

García-Redondo V, Bárbara I, Díaz-Tapia P (2019) Biodiversity of epiphytic macroalgae (Chlorophyta, Ochrophyta, and Rhodophyta) on leaves of Zostera marina in the northwestern Iberian Peninsula Anales del Jardín Botánico de Madrid, 76:e078

Gazeau F, Quiblier C, Jansen JM, Gattuso J-P, Middelburg JJ, Heip CHR (2007) Impact of elevated CO2 on shellfish calcification. Geophys Res Lett 34:L07603. https://doi.org/10.1029/2006GL028554

Gledhill DK et al (2015) Ocean and coastal acidification off New England and Nova Scotia. Oceanography 28:182–197. https://doi.org/10.5670/oceanog.2015.41

Glenn M, Mathieson A, Grizzle R, Burdick D (2020) Seaweed communities in four subtidal habitats within the Great Bay estuary New Hampshire: Oyster farm gear, oyster reef, eelgrass bed, and mudflat. J Exp Mar Biol Ecol 524:151307. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jembe.2019.151307

Glibert PM, Wazniak CE, Hall MR, Sturgis B (2007) Seasonal and interannual trends in nitrogen and brown tide in Maryland’s coastal bays. Ecol Appl 17:S79–S87

Gobler CJ, Baumann H (2016) Hypoxia and acidification in ocean ecosystems: coupled dynamics and effects on marine life. Biol Lett 12:20150976. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsbl.2015.0976

Gobler CJ, Buck NJ, Sieracki ME, Sañudo-Wilhelmy SA (2006) Nitrogen and silicon limitation of phytoplankton communities across an urban estuary: The East River-Long Island Sound system. Estuar Coast Shelf Sci 68:127–138. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecss.2006.02.001

Gobler CJ, Lonsdale DJ, Boyer GL (2005) A review of the causes, effects, and potential management of harmful brown tide blooms caused by Aureococcus anophagefferens(Hargraves et Sieburth). Estuaries 28:726–749. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02732911

Hall-Spencer JM, Rodolfo-Metalpa R, Martin S, Ransome E, Fine M, Turner SM, Rowley SJ, Tedesco D, Buia M-C (2008) Volcanic carbon dioxide vents show ecosystem effects of ocean acidification. Nature 454:96–99. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature07051

Hansen MM, Nielsen EE, Mensberg KLD (2006) Underwater but not out of sight: genetic monitoring of effective population size in the endangered North Sea houting (Coregonus oxyrhynchus). Can J Fish Aquat Sci 63:780–787

Harlin MM (1995) Changes in major plant groups following nutrient enrichment. In: McComb AJ (ed) Eutrophic Shallow Estuaries and Lagoons. CRC Press, Boca Raton, pp 173–187

Hattenrath-Lehmann TK et al (2015) The effects of elevated CO2 on the growth and toxicity of field populations and cultures of the saxitoxin-producing dinoflagellate. Alexandrium fundyense Limnol Oceanogr 60:198–214. https://doi.org/10.1002/lno.10012

Haydar D, Wolff WJ (2011) Predicting invasion patterns in coastal ecosystems: relationship between vector strength and vector tempo. Mar Ecol-Prog Ser 431:1–10. https://doi.org/10.3354/meps09170

Hayes KR, Barry SC (2008) Are there any consistent predictors of invasion success? Biol Invasions 10:483–506. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10530-007-9146-5

Heck KL Jr, Orth RJ (2007) Predation in seagrass beds. seagrasses biology, ecology and conservation. Springer, , Dordrecht

Heisler J, Glibert P, Burkholder J, Anderson D, Cochlan W, Dennison W, Gobler C, Dortch Q, Heil C, Humphries E, Lewitus A, Magnien R, Marshall H, Sellner K, Stockwell D, Stoecker D, Suddleson M (2008) Eutrophication and harmful algal blooms: a scientific consensus. Harmful Algae 8(1):3–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hal.2008.08.006

Hepburn CD, Pritchard DW, Cornwall CE, McLeod RJ, Beardall J, Raven JA (2011) Diversity of carbon use strategies in a kelp forest community: implications for a high CO2 ocean. Glob Change Biol 17:2488–2497. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2486.2011.02411.x

Hofmann LC, Straub S, Bischof K (2012) Competition between calcifying and noncalcifying temperate marine macroalgae under elevated CO2 levels. Mar Ecol-Prog Ser 464:89–105

Holmer M, Frederiksen MS, Møllegaard H (2005) Sulfur accumulation in eelgrass (Zostera marina) and effect of sulfur on eelgrass growth. Aquat Bot 81:367–379

Holmlund MB, Peterson CH, Hay ME (1990) Does algal morphology affect amphipod susceptibility to fish predation. J Exp Mar Biol Ecol 139:65–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-0981(90)90039-F

Husa V, Sjøtun K, Lein TE (2004) The newly introduced species Heterosiphonia japonica Yendo (Dasyaceae, Rhodophyta): geographical distribution and abundance at the Norwegian southwest coast. Sarsia 89:211–217

Idlebrook C (2012) Invasive seaweed creeping up maine coast. Island Institute. http://www.workingwaterfront.com/articles/Invasive-Seaweed-Creeping-Up-Maine-Coast/15065. Accessed 8 Feb 2019

Johnson AM, Maberly SC, Raven JA (1992) The acquisition of inorganic carbon by four red macroalgae. Oecologia 92:317–326

Jueterbock A, Tyberghein L, Vergbruggen H, Coyer JA, Olsen JL, Hoarau G (2013) Climate change impact on seaweed meadow distribution in the North Atlantic rocky intertidal. Ecol Evol 3:1356–1373. https://doi.org/10.1002/ece3.541

Kang C-K, Choy EJ, Son Y, Lee J-Y, Kim JK, Kim Y, Lee K-S (2008) Food web structure of a restored macroalgal bed in the eastern Korean peninsula determined by C and N stable isotope analyses. Mar Biol 153:1181–1198. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00227-007-0890-y

Kang Y, Koch F, Gobler CJ (2015) The interactive roles of nutrient loading and zooplankton grazing in facilitating the expansion of harmful algal blooms caused by the pelagophyte Aureoumbra lagunensis, to the Indian River Lagoon, FL, USA. Harmful Algae 49:162–173. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hal.2015.09.005

Kendall C, McDonnell JJ (2012) Isotope tracers in catchment hydrology. Elsevier, Amsterdam

Kim YS, Choi HG, Nam KW (2008) Seasonal variations of marine algal community in the vicinity of Uljin nuclear power plant. Korea J Environ Biol 29:493–499

Kinney EL, Valiela I (2011) Nitrogen loading to Great South Bay: Land use, sources, retention, and transport from land to bay. J Coastal Res 27:672–686

Koch M, Bowes G, Ross C, Zhang X-H (2013) Climate change and ocean acidification effects on seagrasses and marine macroalgae. Global Change Biol 19:103–132. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2486.2012.02791.x

Lapointe BE, Barile PJ, Matzie WR (2004) Anthropogenic nutrient enrichment of seagrass and coral reef communities in the Lower Florida Keys: discrimination of local versus regional nitrogen sources. J Exp Mar Biol Ecol 308:23–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jembe.2004.01.019

Leclerc JC, Riera P, Leroux C, Lévêque L, Laurans M, Schaal G, Davoult D (2013) Trophic significance of kelps in kelp communities in Brittany (France) inferred from isotopic comparisons. Mar Biol 160:3249–3258. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00227-013-2306-5

Lein TE (1999) A newly immigrated red alga ('Dasysiphonia’, Dasyaceae, Rhodophyta) to the Norwegian coast. Sarsia 84:85–88

Liu D, Keesing JK, Xing Q, Shi P (2009) World’s largest macroalgal bloom caused by expansion of seaweed aquaculture in China. Mar Pollut Bull 58:888–895

Lopez G et al (2014) Biology and ecology of Long Island sound. In: Latimer J, Tedesco M, Swanson R, Yarish C, Stacey P, Garza C (eds) Long Island Sound. Springer, New York, NY, pp 285–479

Low NHN, Drouin A, Marks CJ, Bracken MES (2015) Invader traits and community context contribute to the recent invasion success of the macroalga Heterosiphonia japonica on New England rocky reefs. Biol Invasions 17:257–271. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10530-014-0724-z

Lyngby JE, Mortensen S, Ahrensberg N (1999) Bioassessment techniques for monitoring of eutrophication and nutrient limitation in coastal ecosystems. Mar Pollut Bull 39:212–223

Maberly SC, Raven JA, Johnston AM (1992) Discrimination between 12C and 13C by marine plants. Oecologia 91:481–492

MacIntyre HL, Lomas MW, Jeff C, Suggett DJ, Gobler CJ, Koch EW, Kana TM (2004) Mediation of benthic-pelagic coupling by microphytobenthos: an energy- and material-based model for initiation of blooms of Aureococcus anophagefferens. Harmful Algae 3:403–437. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hal.2004.05.005

Marsh GE (2008) Seawater pH and anthropogenic carbon dioxide. University of Chicago, Argonne National Laboratory, Chicago

Martz TR, Connery JG, Johnson KS (2010) Testing the Honeywell Durafet® for seawater pH applications. Limnol Oceanogr: Methods 8:172–184. https://doi.org/10.4319/lom.2010.8.172

Mathieson AC, Dawes CJ, Pederson J, Gladych RA, Carlton JT (2008) The Asian red seaweed Grateloupia turuturu(Rhodophyta) invades the Gulf of Maine. Biol Invasions 10:985–988. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10530-007-9176-z

Meehl GA et al (2007) Global climate projections. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Melzner F et al (2013) Future ocean acidification will be amplified by hypoxia in coastal habitats. Mar Biol 160:1875–1888. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00227-012-1954-1

Millero FJ (2010) History of the equation of state of seawater. Oceanography 23:18–33. https://doi.org/10.5670/oceanog.2010.21

Mineur F, Roux AL, Maggs CA, Verlaques M (2014) Positive feedback loop between introductions of non-native marine species and cultivation of oysters in Europe. Conserv Biol 28(6):1667–1676. https://doi.org/10.1111/cobi.12363

Moore CG, Harries DB (2009) Appearance of Heterosiphonia japonica (Ceramiales: Rhodophyceae) on the west coast of Scotland, with notes on Sargassum muticum (Fucales: Heterokontophyta). Mar Biodiverv Rec 2:e131. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1755267209990509

Müller R, Laepple T, Bartsch I, Wiencke C (2009) Impact of oceanic warming on the distribution of seaweeds in polar and cold-temperate waters. Bot Mar 52:617–638. https://doi.org/10.1515/BOT.2009.080

Neori A, Msuya FE, Shauli L, Schuenhoff A, Kopel F, Shpigel M (2003) A novel three-stage seaweed (Ulva lactuca) biofilter design for integrated mariculture. J Appl Phycol 15:543–553. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:JAPH.0000004382.89142.2d

Newton C, Bracken ESM, McConville M, Rodrigue K, Thornber CS (2013) Invasion of the red seaweed Heterosiphonia japonica spans biogeographical provinces in the western North Atlantic Ocean. PLoS ONE 8:1–7. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0062261

Nuzzi R, Waters RM (2004) Long-term perspective on the dynamics of brown tide blooms in Long Island coastal bays. Harmful Algae 3:279–293. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.halo.2004.04.001

O’Brien BS, Mello K, Litterer A, Dijkstra JA (2018) Seaweed structure shapes trophic interactions: a case study using a mid-trophic level fish species. J Exp Mar Biol Ecol 506:1–8

Okamura K (1936) Nippon kaisô shi [in Japanese]. Uchida Rokakuho, Tokyo

Olischläger M, Bartsch I, Gutow L, Wiencke C (2013) Effects of ocean acidification on growth and physiology of Ulva lactuca (Chlorophyta) in a rockpool-scenario. Phycol Res 61:180–190. https://doi.org/10.1111/pre.12006

Palacios SL, Zimmerman RC (2007) Response of eelgrass Zostera marina to CO2 enrichment: possible impacts of climate change and potential for remediation of coastal habitats. Mar Ecol-Prog Ser 344:1–13. https://doi.org/10.3354/meps07084

Parsons TR (2013) A manual of chemical & biological methods for seawater analysis. Elsevier, Philadelphia

Pedersen A, Kraemer G, Yarish C (2008) Seaweed of the littoral zone at Cove Island in Long Island Sound: annual variation and impact of environmental factors. J Appl Phycol 20:419–432. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10811-008-9316-6

Petrocelli A, Cecere E, Verlaque M (2013) Alien marine macrophytes in transitional water systems: new entries and reappearances in a Mediterranean coastal basin. BioInvasions Rec 2(3):177–184. https://doi.org/10.3391/bir.2013.2.3.01

Ramsay-Newton C (2015) Early strategies of invasive seaweeds: the recent invasion of Dasysiphonia (formerly, "Heterosiphonia") japonica to the western North Atlantic Ocean. Northeastern University

Ramsay-Newton C, Drouin A, Hughes AR, Bracken MES (2017) Species, community, and ecosystem-level responses following the invasion of the red alga Dasysiphonia japonica to the western North Atlantic Ocean. Biol Invasions 19:537–547. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10530-016-1323-y

Raven JA et al (2002) Mechanistic interpretation of carbon isotope discrimination by marine macroalgae and seagrasses. Funct Plant Biol 29:355–378

Ries JB, Cohen AL, McCorkle DC (2009) Marine calcifiers exhibit mixed responses to CO2-induced ocean acidification. Geology 37:1131–1134

Rosenberg G, Ramus J (1984) Uptake of inorganic nitrogen and seaweed surface area: volume ratios. Aquat Bot 19:65–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-3770(84)90008-1

Sagerman J, Enge S, Pavia H, Wikström SA (2014) Divergent ecological strategies determine different impacts on community production by two successful non-native seaweeds. Oecologia 175:937–946

Sagerman J, Enge S, Pavia H, Wikström SA (2015) Low feeding preference of native herbivores for the successful non-native Heterosiphonia japonica. Mar Biol 162:2471–2479

Sant N, Delgado O, Rodríguez-Prieto C, Ballestros E (1996) The spreading of the introduced seaweed Caulerpa taxifolia (Vahl) C. Agardh in the Mediterranean Sea: testing the boat transportation hypothesis. Bot Mar, 39:427–430. https://doi.org/10.1515/botm.1996.39.1-6.427

Savoie AM, Saunders GW (2013) First record of the invasive red alga Heterosiphonia japonica (Ceramiales, Rhodophyta) in Canada. BioInvasions Records 2:27–32. https://doi.org/10.3391/bir.2013.2.1.04

SCDHS (2018) Suffolk county department of health services water quality monitoring for 2018. Suffolk County Department of Health Services

Schneider CW (2010) Report of a new invasive alga in the Atlantic United States: Heterosiphoniajaponica in Rhode Island. J Phycol 46:653–657. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1529-8817.2010.00866.x

Sinha E, Michalak AM, Balaji V (2017) Eutrophication will increase during the 21st century as a result of precipitation changes. Science 357:405–408. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aan2409

Sjøtun K, Husa V, Peña V (2008) Present distribution and possible vectors of introductions of the alga Heterosiphonia japonica (Ceramiales, Rhodophyta) in Europe. Aquat Invasions 3:377–394

Southward AJ, Hawkins SJ, Burrows MT (1995) Seventy years’ observations of changes in distribution and abundance of zooplankton and intertidal organisms in the western English Channel in relation to rising sea temperature. J Therm Biol 20:127–155. https://doi.org/10.1016/0306-4565(94)00043-I

Stewart Van Patten M, Yarish C (2009) Bulletin No. 39: Seaweeds of Long Island Sound Bulletins 40, pp. 104

Talmage SC, Gobler CJ (2010) Effects of past, present, and future ocean carbon dioxide concentrations on the growth and survival of larval shellfish. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107:17246–17251. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0913804107

Talmage SC, Gobler CJ (2011) Effects of elevated temperature and carbon dioxide on the growth and survival of larvae and juveniles of three species of northwest Atlantic bivalves. PLoS ONE 6:e26941. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0026941

Tang YZ, Kang Y, Berry D, Gobler CJ (2015) The ability of the red macroalga, Porphyra purpurea (Rhodophyceae) to inhibit the proliferation of seven common harmful microalgae. J Appl Phycol 27:531–544. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10811-014-0338-y

Theoharides KA, Dukes JS (2007) Plant invasion across space and time: factors affecting nonindigenous species success during four stages of invasion. New Phytol 176:256–273. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8137.2007.02207.x

Underwood T (1986) Analysis of competition by field experiments. In: Kikkawa J, Anderson DJ (eds) Community ecology: pattern and process. Blackwell Scientific Publications, Melbourne, pp 240–268

Valiela I, Cole ML (2002) Comparative evidence that salt marshes and mangroves may protect seagrass meadows from land-derived nitrogen loads. Ecosystems 5:92–102

Valiela I, McClelland J, Hauxwell J, Behr PJ, Hersh D, Foreman K (1997) Macroalgal blooms in shallow estuaries: controls and ecophysiological and ecosystem consequences. Limnol Oceanogr 42:1105–1118. https://doi.org/10.4319/lo.1997.42.5_part_2.1105

Veiga P, Rubal M, Sousa-Pinto I (2014) Structural complexity of macroagae influences epifaunal assemblages associated with native and invasive species. Mar Environ Res 101:115–123. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marenvres.2014.09.007

Vranken S, Bosch S, Peña V, Leliaert F, Mineur F, Clerck OD (2018) A risk assessment of aquarium trade introductions of seaweed in European waters. Biol Invasions 20:1171–1187. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10530-017-1618-7

Wallace RB, Baumann H, Grear JS, Aller RC, Gobler CJ (2014) Coastal ocean acidification: The other eutrophication problem. Estuar Coast Shelf Sci 148:1–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecss.2014.05.027

Wallace RB, Gobler CJ (2015) Factors controlling blooms of microalgae and macroalgae (Ulva rigida) in a eutrophic, urban estuary: Jamaica Bay NY, USA. Estuar Coast 38:519–533. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12237-014-9818-1

Ware C, Dijkstra JA, Mello K, Stevens A, O’Brien B, Ikedo W (2019) A novel three-dimensional analysis of functional architecture that describes the properties of macroalgae as a refuge. Mar Ecol-Prog Ser 608:93–103. https://doi.org/10.3354/meps12800

Warfe DM, Barmuta LA, Wotherspoon S (2008) Quantifying habitat structure: surface convolution and living space for species in complex environments. Oikos 117:1764–1773. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0706.2008.16836.x

Watanabe J (1984) The influence of recruitment, competition, and benthic predation on spatial distributions of three species of kelp forest gastropods (Trochidae: Tegula). Ecology 65:920–936. https://doi.org/10.2307/1938065

Wernberg T, Russell BD, Thomsen MS, Gurgel CFD, Bradshaw CJA, Poloczanska ES, Connell SD (2011) Seaweed communities in retreat from ocean warming. Curr Biol 21:1828–1832. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2011.09.028

Woodwell GM, Hall CAS, Whitney DE, Houghton RA (1979) The flax pond ecosystem study: exchanges of inorganic nitrogen between an estuarine marsh and Long Island Sound. Ecology 60:695–702

Xu Z, Zou D, Gao K (2010) Effects of elevated CO2 and phosphorus supply on growth, photosynthesis and nutrient uptake in the marine macroalga Gracilaria lemaneiformis (Rhodophyta). Botanica Marina 53:123–129. https://doi.org/10.1515/BOT.2010.012

Young CS, Gobler CJ (2016) Ocean acidification accelerates the growth of two bloom-forming macroalgae. PLoS ONE 11:e0155152. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0155152

Young CS, Gobler CJ (2017) The organizing effects of elevated CO2 on competition among estuarine primary producers. Sci Rep 7:7667. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-08178-5

Young CS, Lowell A, Peterson BJ, Gobler CJ (2019) Ocean acidification and food limitation combine to suppress herbivory by the gastropod Lacuna vincta. Mar Ecol-Prog Ser 627:83–94. https://doi.org/10.3354/meps13087

Young CS, Peterson BJ, Gobler CJ (2018) The bloom forming macroalgae, Ulva, outcompetes the seagrass, Zostera marina, under high CO2 conditions. Estuar Coast 41:2340–2355. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12237-018-0437-0

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the assistance of Andrew Lundstrom and Jennifer Goleski during the analysis of dissolved inorganic carbon and dissolved nutrients during the study. We are appreciative of the logistical support provided by the Stony Brook Southampton Marine Science staff throughout the study. This work was supported by the Rauch Foundation, Laurie Landeau Foundation, Simons Foundation, and New York Sea Grant (R-FBM-38).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions