Abstract

Campylopus introflexus is the only invasive moss listed among the 100 most prominent alien invaders in Europe. The present study shows dot distribution maps (at 10-years intervals from its introduction in 1986 to the present) and discusses the dynamics of its invasion, altitudinal distribution and ecological preferences. During the 30 years of its invasion, C. introflexus has spread widely throughout Poland and is currently known in 248 locations. A total of 93.1% of these are below 300 m a.s.l., and the maximum altitude is 780 m. With the passage of time since its first appearance this alien moss has occupied larger numbers of substrates and habitats. Currently C. introflexus is a component of 34 plant communities belonging to 18 habitat types. The most invaded habitats include young forest tree plantations and mature managed forest developed from old plantations (Pinus sylvestris woodland). This moss is frequently found in acidophilous semi-natural forests and inland dunes with Corynephorus and Agrostis grasslands, boggy woodland, dry heaths, and ruderal habitats. Although 30 cryptogam species were found in tufts of the alien moss, there is no characteristic species composition that constantly accompanies its presence.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The invasion of alien species is currently considered to be among the most important and difficult problems confronting nature protection. Compared with vascular plants, the phenomenon of non-native species invasion occurs on a much smaller scale in mosses. There is also a much smaller negative impact on biodiversity and on socio-economic features (Essl et al. 2014). On a global scale there are only 106 alien mosses, including 37 cryptogenic species (Essl et al. 2013). In Europe 21 non-native moss species (1.6% of the European moss flora) and 11 cryptogenic species (0.8%) have been identified (Essl and Lambdon 2009). In Poland, there are three alien moss species (0.4% of the Polish moss flora), namely Campylopus introflexus, Orthodontium lineare and Leptophascum leptophyllum (Ochyra et al. 2003; Fudali et al. 2009). The first of these is the most highly invasive and is listed among the 100 most prominent alien invaders (Lambdon 2009). Molecular studies on Campylopus introflexus have demonstrated that in its entire native and secondary ranges it is genetically homogenous (Stech and Dohrmann 2004; Gama et al. 2017). It is thus impossible to determine using genetic methods whether its European invasion is the result of one or many introductions. Although knowledge of adventive moss invasions remains incomplete, the history of C. introflexus spread in Europe is one of the best known and documented. These data, however, primarily refer to Western Europe (Klinck 2010 and the literature cited there) and to Central Europe (Mikulášková et al. 2012; Szűcs et al. 2014), and few data refer to East-Central Europe.

C. introflexus was first discovered in Poland in October 1986 (Lisowski and Urbański 1989). By 2016 30 years had passed since the first record, presenting a good opportunity to summarize data on the invasion and ecological preferences of this moss in Poland. Moreover, production of a distribution map in this country was attempted nearly 10 years ago (Fudali et al. 2009). The present study aims to answer the following main questions: (i) what is the current distribution of C. introflexus in Poland and what was the dynamic of its spread? (ii) What substrates and habitats were invaded by C. introflexus and were its ecological preferences changed as a result? (iii) With which native species of bryophytes and lichens does C. introflexus coexist?

Methods

The study species

Campylopus introflexus is a perennial, acrocarpous, medium-sized moss that forms yellowish to olive green or rarely dark green loose tufts or dense mats; hoary when dry. Shoots are 0.5–7.0 cm tall, with slender internodes and swollen nodes, tomentum reddish-brown present or almost absent. Leaves 2.5–6.0 mm in length, straight, erecto-patent when moist, appressed when dry, lanceolate with entire margins. Costa strong, excurrent in a dentate hyaline hair-point, which is conspicuously 90° reflexed; rarely, in plants growing in shade, hyaline hair-tip short or almost lacking. It commonly reproduces vegetatively by deciduous leaves and fragile stem tips which facilitate its short-distance spread. Dioicous, female shoots have terminal perichaetial buds which frequently produce sporophytes. Plants are occasionally polysetous; setae yellow–brown to pale brown, 5–15 mm long, curved or sinuose. Capsule brown, slightly asymmetric and curved, furrowed and shrunken when dry; spores pale brown, small 10–14 μm; ripe sporophytes have been observed in Poland between March and October.

Native range—C. introflexus is native to the Southern Hemisphere, where this moss has a pan-temperate range. C. introflexus is widespread in the southern part of South America and Africa, southern and eastern parts of Australia, in Tasmania and in New Zealand. Its range reaches north to New Caledonia, Réunion, St Helena, while it has been reported from most Subantarctic and some Antarctic islands (Gradstein and Sipman 1978; Söderström 1992; Ochyra et al. 2008; Klinck 2010).

Non-native, secondary range—Outside its native range it was first recorded in 1941 at Washington, West Sussex in Great Britain and in 1942 at Howth near Dublin in Ireland (Richards 1963). On mainland Europe, it was initially observed in 1954 in Brittany in France (Størmer 1958) before spreading rapidly throughout Europe (Gradstein and Sipman 1978; Söderström 1992; Smith 2004; Lambdon 2009; Klink 2010). The current non-native range of C. introflexus in Europe extends north to Iceland (Klinck 2010), south-west Norway (Øvstedal 1978) and Sweden (Hällingbäck et al. 1985); north-east—along the Baltic coasts—by the Kaliningrad Province of Russia (Razgulyaeva et al. 2001), Lithuania (Jukonienė et al. 2015), Latvia (Abolina and Reriha 2004) to Estonia (Vellak et al. 2009); east to Ukraine (Lobachevska and Sokhanchak 2010), Hungary (Szűcs et al. 2014), Turkey (Ros et al. 2013); south to Italy and the Mediterranean islands (Bealarics, Corsica, Sardinia) (Ros et al. 2013), and west to Portugal (Sérgio 1979) it has also been reported from the Azores, Madeira, and the Canary Islands in Macaronesia (Ros et al. 2013). C. introflexus frequently grows along the Pacific coasts of North America and has also been recorded in California, Oregon, Washington, and southern British Columbia (Frahm 2007; Carter 2014).

Ecology—The habitats that C. introflexus occupies in its native range are similar to those in the secondary (alien) range. It has a high ecological tolerance, and its populations are associated with both undisturbed and anthropogenic sites. In Europe C. introflexus occurs on a wide range of substrata and in greatly varied habitats. It is seen most frequently on acid sandy and sandy-gravelly soils, bare dry peat and less often on decaying rotten wood, rocks, waste deposits, and roofs of buildings. Its habitats include coastal grey dunes, dry sandy grassland vegetation, moorland, raised and blanket bogs (mostly disturbed or burned), coniferous forest, forestry tracks, plantations, forest ridges and clearings and margins of fish ponds (Richards and Smith 1975; Smith 2004; Lambdon 2009; Klinck 2010; Mikulášková et al. 2012). In North America C. introflexus primarily colonizes poor acid soils along the Pacific coasts in Pine forest and on stabilized sand dunes. It thrives on sandy soils along trails, at the base of trees, on the roofs of buildings, and on peat in bogs (Frahm 2007; Carter 2014). In active volcanic zones in Antarctica, Iceland, and in central Italy, this moss grows on geothermal ground and around active vents emitting sulphur and steam (Chiarucci et al. 2008; Ochyra et al. 2008; Klinck 2010).

Data sources and data analysis

In the present study we provide data on the occurrence and ecological preferences of the adventive moss C. introflexus in Poland as at the end of 2016.

We re-examined over 330 specimens of C. introflexus from the following herbaria: KRAM, KTU, LBL, LOD, POZG, SOSN, WA and WRSL. The above mentioned 8 herbaria are the most important, largest, and most active institutions where moss collections are housed from the whole of Poland. We checked also the databases of the Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF), Biological Collection Access Service for Europe (BioCASE) and e.g. the catalogue of herbarium S, but they contained few data about the occurrence of C. introflexus in Poland, being limited to what was already known from the labels of specimens housed in Polish Herbaria. Polish publications in which this species had been mentioned were also studied. The published data of the species are reliable, as there are virtually no mistakes in the taxon designations which were confirmed by the herbarium collections that we reviewed. C. introflexus is easily recognized, among other attributes, by the conspicuously 90° reflexed hair points and is unlikely to be confused with any other species in Poland. The revised specimens and published data on its occurrence refer to 248 localities, including collections from 91 stands, in which we made complete observations and provided descriptions of the ecological situation. In this group there are 60 unpublished stations. For 113 sites, information on species co-occurring with C. introflexus is available. All information on habitat, altitude, substrates, and associated species was included in a database. The data gathered during fieldwork and information from herbarium labels were used to describe the ecological preferences of the Polish populations of C. introflexus. A herbarium-based method has previously been successfully used, among others, to assess changes in the frequency of mosses in Sweden (Hedenäs et al. 2002) and to reconstruct the spread of invasive plants (Delisle et al. 2003).

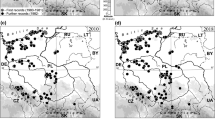

The distribution of C. introflexus is shown on dot maps at 10-years intervals (Fig. 1a–c). We also prepared a curve showing the spread of this alien species in Poland (Fig. 1e). Its distribution pattern is biased to some extent by herbarium sampling intensity and the research activity of bryologists during fieldwork. This impact was higher in the initial phase of invasion and later became increasingly less significant. At first this exotic moss was considered to be a rare and interesting plant so bryologists started to pay attention to it and its new stations were published. This phenomenon is an inherent imperfection of works based mostly on herbarium data and has already been discussed by Hedenäs et al. (2002), Delisle et al. (2003), and Hassel and Söderström (2005).

Contingency tables were used to examine whether there had been any significant changes over time in the frequency of invaded habitats and substrata. The G-test was used to determine the frequency of these over three time intervals ending in the years 1996, 2006 and 2016. The data from 1986 were further included in the next interval as single records derived before 1996.

To show the diversity of species accompanying C. introflexus, Nonmetric Multidimensional Scaling (NMDS) was applied due to presence/absence of species data with the Bray–Curtis distance. For habitats, a 1–6 scale of disturbance (rare; occasional; infrequent; frequent; strong at the initial establishment; strong), and a 1–4 scale of nutrient availability (low, rare pulses; low, occasional pulses; medium; high) were assigned according to Pyšek et al. (2010). The years 1986–2016 of recording were included in the analysis. Distance-based Redundancy Analysis (db-RDA), a constrained equivalent of NMDS was used to assess the impact of disturbance, nutrient availability and year (residence time) on the composition of species accompanying C. introflexus. R language and environment (version 3.4.2), and packages DescTools and vegan were used in the statistical analyses (R Core Team 2016).

Nomenclature and terminology

The terminology for plant invasion follows Richardson et al. (2011). We adopted the EUNIS habitat classification (Interpretation manual of EU habitats—EUR 28, April 2013). The classifications and names of syntaxa were assigned according to Matuszkiewicz (2001) and Schaminée et al. (2014). The nomenclature of mosses was consistent with Ochyra et al. (2003). Acronyms of the herbaria were assigned according to the Index Herbariorum (Thiers [continuously updated]).

Results

The first mention of C. introflexus in 1986 was from Wielkopolska Province in Western Poland, where this moss occurred in a Pinus sylvestris plantation (11.10.1986, leg. S. Lisowski; POZG). Then the species began to spread quickly. 5 years later, it was known from 17 stands, and in the following decades, the number of its localities continued to grow rapidly. At the end of 2016 C. introflexus had been reported from 248 stands (Fig. 1a–e). Initially two centres of occurrence were observed: the first in north-western Poland (mainly in the region of prevailing winds from the Baltic Sea), and the second in southern Poland to the north of the Moravian Gate separating the Carpathians and Sudetes (Fig. 1a). Next, the neophyte spread widely throughout Western Poland (Fig. 1b) and reached the eastern part of the country in the most recent decade, but the density of its sites there is much lower (Fig. 1c). C. introflexus is a lowland species, and 93.1% of its sites are below 300 m a.s.l. Its highest localities reach the mountain lower forest belt. Local maximum altitudes are in the Central Sudetes, on the Ubocze Mt. in the Bystrzyckie Mts (alt. 780 m, leg. M. Smoczyk, 2015), and in Lipnica Wielka in the Western Carpathians (alt. 750 m, leg. A. Stebel & G. Vončina, 2013; SOSN).

C. introflexus, almost from its first introduction in Poland, has produced sporophytes with the initial data from the Baltic coast (loc. Mierzeja Sarbska, leg. A. Grabowska, 1989; KRAM and loc. Rowy, leg. P. Urbański, 1990; POZG, SOSN). This adventive moss produces sporophytes in 18.3% of its localities, of which 73.8% are located in northern and western Poland, and the remaining 26.2% in the southern and central parts of the country. Mature sporophytes have been recorded between March and October, but 85.7% of these were observed between June and September. Plants forming sporophytes most frequently grew on podzolic soil (53.8%), mineral sandy soil (39.3%) and occasionally on dry eroded peat (7.1%). These mostly occurred in young coniferous forest tree plantations (32.1%) and in mature managed forest (Pinus sylvestris woodland; 32.1%), and much less often in semi-natural forests (Leucobryo-Pinetum; 10.7%) or on European dry heaths (7.2%).

There are significant differences in the substrata (G = 26.5, p = 0.02213) as well as in the habitats (G = 50.73, p = 0.03244) occupied by C. introflexus. In the first years, this species most often inhabited mineral sandy soil and was rarely found on other substrates. In the third decade of invasion, it was more frequently observed on podzolic soil than on mineral sandy soil, and its frequency on dry eroded peat escalated; overall, the range of substrates occupied by this moss has increased (Table 1). Alongside its prolonged residence time, C. introflexus has inhabited an increasing number of habitats (Table 2). In the first decade of invasion, this moss was frequently noted in Pinus sylvestris plantations and Calluno-Genistetum dry heaths and less often in the P. sylvestris woodland. After 30 years of spread it has overcome a number of biocoenotic barriers and is currently involved in 34 plant communities belonging to 18 habitat types (Table 2). The most invaded habitats are young forest tree plantations and mature managed forest (Pinus sylvestris woodland). C. introflexus also often forms numerous populations in acidophilous semi-natural forests, inland dunes with Corynephorus and Agrostis grassland, boggy woodland, dry heaths, and ruderal habitats.

In total, 30 cryptogams (2 liverwort species, 25 mosses and 3 lichens) were found in tufts of C. introflexus (Table 3). Merely 10 mosses and one lichen species were found with frequencies of more than 5%, the most common of these being Pohlia nutans, Ceratodon purpureus, Dicranum scoparium and Cladonia spp. According to dbRDA only year = residence time (pseudo-F = 16.17, p = 0.001) and nutrient availability (pseudo-F = 3.95, p = 0.014) were significant variables (Fig. 2). Residence time negatively affected species composition, indicating that none of the species were associated with increasing time. Among other species Polytrichastrum formosum and Dicranum polysetum are slightly associated with relatively higher nutrient availability.

Discussion and conclusion

In the first report on the occurrence of C. introflexus in Poland, Lisowski and Urbański (1989) cited four specimens collected in the years 1986–1987 at three stations in the western and north-western parts of the country. Currently, these specimens are housed in herbaria KRAM, LBL, POZG and SOSN which contain fragments of a 2–4-years-old turf of this species. Thus, it is obvious that this moss had previously occurred in western Poland. Although it is relatively large and easy to distinguish, the initial introduction of C. introflexus in Poland went undetected. The pattern of its distribution in 1996 and in 2006 (Fig. 1a, b) suggests that C. introflexus first invaded Poland in the west from Brandenburg and later from Saxony in Germany, where this moss was known from numerous areas bordering Poland (Düll and Meinunger 1989) and from the south, through the Moravian Gate, from the Moravian-Silesian Region of Czech Republic (Mikulášková 2006; Mikulášková et al. 2012). If we consider its invasion curve (Fig. 1e), and the fact that the precise time of its introduction was unnoticed (see above), the length of the lag phase of C. introflexus in Poland was approximately 9–12 years. This is similar to that observed in Britain and Western Europe, estimated to be approximately 10 years (Hassel and Söderström 2005). After this period, C. introflexus began to spread aggressively and the number of its localities in Poland started to increase exponentially (Fig. 1e). This effect probably resulted from more attention being paid to this alien moss; notably, a similarly shaped invasion curve of the species had previously been observed in Europe (e.g., Hassel and Söderström 2005; Mikulášková 2006). In 30 years C. introflexus has reached the eastern border of Poland, spreading approximately 650 km, and the current pattern of its distribution is similar to that observed in the Czech Republic (Mikulášková et al. 2012). It now occurs almost all over Poland, but is much commoner in the previously colonized western and southern parts of the country where most of the habitats were occupied and, as a consequence, there was higher propagule pressure (Fig. 1c).

The altitudinal range of C. introflexus in Europe is small, i.e., it grows up to 400 m a.s.l. in Britain and Ireland (Smith 2004), 110 m in Sweden (Hällingbäck et al. 1985), and 324 m in Hungary (Szűcs et al. 2014). Its highest locality in Western Europe is likely to be at 1700 m in Lucerne in Switzerland (Martinez et al. 2011) and in Central Europe at 1140 m in Šumava in the Czech Republic (Mikulášková 2006). Similarly, in Poland, 93.1% of C. introflexus sites are located in the lowlands, whereas only 6.9% are in the uplands and in the mountains. Its highest locality is at 780 m within the lower mountain forest belt in the Sudetes Mts.

Although C. introflexus is dioicous, in Europe, male and female plants are frequently found in its tufts, and it reproduces sexually (Klinck 2010). In the Czech Republic, for example, almost 30% of the population contains fertile plants, which in summer produce sporophytes (Mikulášková et al. 2012). In Poland, the sporophyte-producing population is smaller, amounting to slightly more than 18%, and the sporogones ripen between March and October (most often in the period from June to September). Sporophytes were mainly observed in dry habitats; on strongly moist substrates there were no plants with sporogones. The plants produce a large number of small spores that can be spread over long distances mainly by wind (Hassel and Söderström 2005). It primarily reproduces vegetatively by fragments of fragile leaves and tips of shoots. The huge mass of these diaspores, not only carried by the wind but also by animals and human activity, allows this moss to invade new areas. This last type of reproduction enhances the success of C. introflexus in spreading over short distances (Klinck 2010).

C. introflexus, throughout its secondary European range, invades similar substrates. Most often it grows on bare peat, nutrient poor acidic sandy soil or on coniferous forest soil with a thin layer of spruce- or pine-humus litter. It rarely occurs on other substrates, e.g., rocks, decaying wood, anthropogenic soil, mine waste, old walls, etc. (Richards 1963; Hassel and Söderström 2005; Lambdon 2009; Klinck 2010). These substrates must be dry because a high degree of water saturation limits its growth (Equihua and Usher 1993; Mikulášková et al. 2012; Priede and Mežaka 2016). During its spread in Poland C. introflexus gradually broadened its range of substrates and ultimately occurred on eight types (Table 1). Initially it primarily inhabited mineral sandy soil (66.7% of records in the years 1986–1996), while in the third decade of invasion (2006–2016) it much more frequently occurred on podzolic soil (41.5% of records) rather than on mineral sandy soil (35.9%), and its frequency increased on dry eroded peat (11.3%).

C. introflexus is a eurytopic moss showing a wide range of habitat and phytocoenotic preferences. It is primarily a successful early-successional invader in open places and gaps where there is little competition from vascular plants. In various regions of Europe, depending on environmental conditions, C. introflexus exhibits slightly different ecological preferences (Klinck 2010). In Britain and Ireland, it grows mainly in bogs and moorlands frequently disturbed by man or fire, and on forestry tracks (Richards 1963; Richards and Smith 1975; Equihua and Usher 1993). In the oceanic part of Western Europe, C. introflexus typically occurs on dry coastal and inland dunes, in sandy grassland, on heaths, at the margins of pine forest and in ruderal habitats (Berg 1985; Hassel and Söderström 2005; Hasse 2007; Daniëls et al. 2008; Klinck 2010). In the south-western part of the Scandinavian Peninsula and in the Baltic countries, C. introflexus is frequently recorded on cliff ledges, in disturbed peatland and at the margins of coniferous forest (Hällingbäck et al. 1985; Razgulyaeva et al. 2001; Vellak et al. 2009; Jukonienė et al. 2015; Priede and Mežaka 2016). In the Czech Republic in Central Europe 70% of C. introflexus stands are in coniferous forest and pine or spruce plantations, and 20% in disturbed peat bogs (Mikulášková et al. 2012). In Poland, C. introflexus demonstrates the ecological preferences observed in Western Europe, the Baltic countries, and in the Czech Republic bordering the south of Poland. Notably, during its spread it constantly expanded the range of invaded habitats and communities (Table 2). In the first decade (1986–1996), C. introflexus mostly occurred in young forest tree plantations (45.8% of records) and in European dry heaths (16.7%). After 30 years of invasion it is present in 19 communities from 13 types of European Union habitat, including two habitats of priority importance. Among this group, the most frequently invaded sites are inland dunes with open Corynephorus and Agrostis grassland (9.7%), boggy woodland (5.6%) and European dry heaths (5.2%). In addition C. introflexus is also a component of 15 communities in five types of the remaining habitats, and is most often recorded in young forest tree plantations (23.8%), and mature managed forest developed from old plantations (23.4%). In the last decade, C. introflexus has also increased in semi-natural forests (11.7%).

As in other countries in Central Europe, C. introflexus mainly coexists with eurytopic common mosses growing in dry, sandy open places or in gaps in coniferous forest and on dried peat in degraded peat bogs. The most common accompanying species are Pohlia nutans, Ceratodon purpureus, Dicranum scoparium and Polytrichum juniperinum, among others (Berg 1985; Mikulášková et al. 2012; Szűcs et al. 2014). The present study indicates that the species composition of bryophytes and lichens accompanying C. introflexus varies according to the type of habitat and nutrient availability. There has been no characteristic species association accompanying C. introflexus at any time or in any place.

We have not conducted detailed studies of the effects of C. introflexus on biocoenoses, but repeated field observations confirm its negative impact on native vegetation. The patches of dry dune grassland, heaths and dry pine forest with dense carpets of C. introflexus are monotonous and floristically poorer than adjacent areas not colonized by this species. Its dense carpets limit the development of other plants and lichens. In Western Poland, in Cladonio-Pinetum, Zarabska and Rosadziński (2011) reported that its aggresive spread threatened the lichen Pycnothelia papillaria which is known only from several stands in the country. Notably, C. introflexus increasingly invades valuable European Union habitats (including priority ones) and will increasingly affect the species richness and structure of these sites (Table 2).

C. introflexus has not yet completed its spread in Poland and the number of its sites will rapidly increase, especially in the eastern part of the country and in the lower parts of the Carpathians Mts and Sudetes Mts in the south. The large areas of sandy and podzolic soils with coniferous forest create perfect conditions for the invasion of this exotic alien, which, in a short time, can become one of the most common mosses in the country. Thus, C. introflexus is a transformer that must be strictly monitored.

References

Abolina A, Reriha I (2004) Papildinajumi Sliteres Nacionala Parka Sunaugu florai. Latvijas Universitates 62. Zinatniska Konference. Geografija. Geologija. Vides zinatne. Referatu tezes, Riga, pp 14–16. (In Latvian)

Berg C (1985) Zur Ökologie der neophytischen Laubmoosart Campylopus introflexus (Hedw.) Brid. in Mecklenburg. Arch Freunde Naturg Mecklb 25:117–126

Carter BE (2014) Ecology and distribution of the introduced moss Campylopus introflexus (Dicranaceae) in western North America. Mandroño 61(1):82–86. https://doi.org/10.3120/0024-9637-61.1.82

Chiarucci A, Calderisi M, Casini F, Bonini I (2008) Vegetation at the limits for vegetation: vascular plants, bryophytes and lichens in a geothermal field. Folia Geobot 43(1):19–33. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12224-008-9002-0

Daniëls FJA, Minarski A, Lepping O (2008) Dominace pattern changes of a lichen-rich Corynephorus grassland in the inland of The Netherlands. Annali di Botanica (Roma) 8:9–19

Delisle F, Lavoie C, Jean M, Lachance D (2003) Reconstructing the spread of invasive plants: taking into account biases associated with herbarium specimens. J Biogeogr 30(7):1033–1042. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2699.2003.00897.x

Düll R, Meinunger L (1989) Deutschlands Moose. I. Teil: Anthocerotae, Marchantiatae, Bryide: Tetraphidales—Pottiales. IDH, Bad Münstereifel

Equihua M, Usher MB (1993) Impact of carpets of the invasive moss Campylopus introflexus on Calluna vulgaris regeneration. J Ecol 81:359–365

Essl F, Lambdon PW (2009) Alien bryophytes and lichens of Europe. In: Daisie (ed) Handbook of alien species in Europe. Invading nature Springer series in invasion ecology 3. Springer Science and Busines Media, Dordrecht, pp 29–42

Essl F, Steinbauer K, Dullinger S, Mang T, Moser D (2013) Telling a different story: a global assessment of bryophyte invasions. Biol Invasions 15(9):1933–1946. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10530-013-0422-2

Essl F, Steinbauer K, Dullinger S, Mang T, Moser D (2014) Little, but increasing evidence of impacts by alien bryophytes. Biol Invasions 16(5):1175–1184. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10530-013-0572-2

Frahm J-P (2007) Campylopus bridel. In: Flora of North America Editorial Committee (ed) Flora of North America north of Mexico. Vol 28, part 2. Oxford University Press, New York, pp 366–376

Fudali E, Szczepański M, Rusińska A, Rosadziński S, Wolski G (2009) The current distribution in Poland of some European neophytic bryophytes with supposed invasive tendencies. Acta Soc Bot Pol 78(1):73–80

Gama R, Aguirre-Gutiérrez J, Stech M (2017) Ecological niche comparison and molecular phylogeny segregate the invasive moss species Campylopus introflexus (Leucobryaceae, Bryophyta) from its closest relatives. Ecol Evol 7:8017–8031. https://doi.org/10.1002/ece3.3301

Gradstein SR, Sipman HJM (1978) Taxonomy and world distribution of Campylopus introflexus and C. pilifer (= C. polytrichoides): a new synthesis. Bryologist 81(1):114–121

Hällingbäck T, Johansson T, Schmitt A (1985) Hårkvastmossa, Campylopus introflexus, i Sverige. Svensk Botanisk Tidskrift 79:41–47

Hasse T (2007) Campylopus introflexus invasion in a dune grassland: succession, disturbance and relevance of existing plant invader concepts. Herzogia 20:305–315

Hassel K, Söderström L (2005) The expansion of the alien mosses Orthodontium lineare and Campylopus introflexus in Britain and continental Europe. J Hattori Bot Lab 97:183–193

Hedenäs L, Bisang I, Tehler A, Hamnede M, Jaederfelt K, Odelvik G (2002) A herbarium–based method for estimates of temporal frequency changes: mosses in Sweden. Biol Cons 105(3):321–331. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0006-3207(01)00212-9

Interpretation Manual of European Union Habitats—EUR 28 (2013) European Commission DG Environment, Nature ENV B.3

Jukonienė I, Dobravolskaitė R, Sendžikaitė J, Skipskytė D, Repečkienė J (2015) Disturbed peatlands as a habitat of an invasive moss Campylopus introflexus in Lithuania. Boreal Env Res 20(6):724–734

Klinck J (2010) Invasive alien species fact sheet—Campylopus introflexus. In: NOBANIS, Online database of the European network on invasive Alien Species, www.nobanis.org. 14 Jun 2017

Lambdon PW (2009) Campylopus introflexus (Hedw.) Brid., heath star moss (Dicranaceae, Bryophyta). In: Daisie (ed) Handbook of alien species in Europe. Invading nature Springer series in invasion ecology 3. Springer Science + Busines Media, Dordrecht, p 344

Lisowski S, Urbański P (1989) Campylopus introflexus (Hedw.) Brid.—nowy gatunek dla brioflory Polski [Campylopus introflexus (Hedw.) Brid.—a new species in bryoflora of Poland]. Badania fizjograficzne nad Polską zachodnią 39:181–183 (In Polish with English summary)

Lobachevska OV, Sokhanchak RR (2010) Campylopus introflexus (Hedw.) Brid., a new alien moss species in the flora of Ukraine. Ukrainian Bot J 67(3):432–437. (In Russian with English summary)

Martinez K, Hinden H, Burgisser L (2011) Campylopus introflexus (Hedw.) Brid. an alien addition to the bryophyte flora of Geneva. Meylania 47:24–28

Matuszkiewicz W (2001) Przewodnik do oznaczania zbiorowisk roślinnych Polski [A key to determination of the plant communities in Poland]. Vademecum Geobotanicum 3. Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN, Warszawa. (In Polish)

Mikulášková E (2006) Development in distribution of the neophytic moss Campylopus introflexus in the Czech Republic. Bryonora 38:1–10 (In Czech with English abstract and summary)

Mikulášková E, Fajmonová Z, Hájek M (2012) Invasion of central-European habitats by the moss Campylopus introflexus. Preslia 84:863–886

Ochyra R, Żarnowiec J, Bednarek-Ochyra H (2003) Census catalogue of Polish mosses. Institute of Botany Polish Academy of Sciences, Kraków

Ochyra R, Lewis Smith RI, Bednarek-Ochyra H (2008) The illustrated moss flora of Antarctica. Cambridge University Press, New York

Øvstedal DO (1978) Campylopus introflexus (Hedw.) Brid. new to Norway. Lindbergia 4(3–4):336

Priede A, Mežaka A (2016) Invasion of the alien moss Campylopus introflexus in cutaway peatlands. Herzogia 29(1):35–51. https://doi.org/10.13158/heia.29.1.2016.35

Pyšek P, Chytrý M, Jarošík V (2010) Habitats and land-use as determinants of plant invasions in the temperate zone of Europe. In: Perrings CH, Mooney H, Williamson M (eds) Bioinvasions and globalization, ecology, economics, management and policy. Oxford University Press Inc, New York, pp 66–79. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199560158.003.0006

Razgulyaeva LV, Napreenko MG, Wolfram Ch, Ignatov MS (2001) Campylopus introflexus (Dicranaceae, Musci)—an addition to the moss flora of Russia. Arctoa 10:185–189

R Core Team (2016) R: a language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna. https://www.R-project.org/

Richards PW (1963) Campylopus introflexus (Hedw.) Brid. and C. polytrichoides De Not. in the British Isles; a preliminary account. Trans Br Bryol Soc 4(3):404–417. https://doi.org/10.1179/006813863804812390

Richards PW, Smith AJE (1975) A progress report on Campylopus introflexus (Hedw.) Brid. and C. polytrichoides De Not. in Britain and Ireland. J Bryol 8(3):293–298. https://doi.org/10.1179/jbr.1975.8.3.293

Richardson DM, Pyšek P, Carlton JT (2011) A compendium of essential concepts and terminology in invasion ecology. In: Richardson DM (ed) Fifty years of invasion ecology: the legacy of Charles Elton, 1st edn. Wiley-Blackwell, New York, pp 409–420

Ros RM, Mazimpaka V, Abou-Salma U, Aleffi M, Blockeel TL, Brugués M, Cros RM, Dia MG, Dirske GM, Draper I, El–Saadawi W, Erdağ A, Ganeva A, Gabriel R, González-Mancebo JM, Granger C, Herrnstadt I, Hugonnot V, Khalil K, Kürschner H, Losada-Lima A, Luís L, Mifsud S, Privitera M, Puglisi M, Sabovljević M, Sérgio C, Shabbara HM, Sim-Sim M, Sotiaux A, Tacchi R, Vanderpoorten A, Werner O (2013) Mosses of the Mediterranean, an annotated checklist. Cryptogam Bryol 34(2):99–283. https://doi.org/10.782/cryb.v34.iss2.2013.99

Schaminée JHJ, Chytrý M, Hennekens SM, Mucina L, Rodwell JS, Tichý L (2014) Development of vegetation syntaxa crosswalks to EUNIS habitat classification and related data sets. Final report EEA/NSV/12/001, Alterra, Wageningen

Sérgio C (1979) Primeiras localidades para Portugal da Campylopus introflexus (Hedw.) Brid. Portugaliae Acta Biologica, Serie B, Sistematica, Ecologia, Biogeografia e Paleontologia 17:273–274

Smith AJE (2004) The moss flora of Britain and Ireland, 2nd edn. Cambridge University Press, New York

Söderström L (1992) Invasions and range expansions and contractions of bryophytes. In: Bates JW, Farmer AM (eds) Bryophytes and Lichens in a changing environment. Clarendon Press, Oxford, pp 131–158

Stech M, Dohrmann J (2004) Molecular relationships and biogeography of two Gondwanan Campylopus species, C. pilifer and C. introflexus (Dicranaceae). In: Goffinet B, Hollowell V, Magill R (eds) Molecular systematics of bryophytes. Monogr Syst Bot Missouri Bot Gard 98:415–431

Størmer P (1958) Some mosses from the phytogeographical excursion 1–9 through the Armorican massive in 1954. Revue Bryologique et Lichénologique 40(27):13–16

Szűcs P, Csiky J, Papp B (2014) Distribution of Campylopus introflexus (Hedw.) Brid. in Hungary. Kitaibelia 19(2): 212–219 (In Hungarian with English summary)

Thiers B [continuously updated] Index Herbariorum: A global directory of public herbaria and associated staff. New York Botanical Garden’s Virtual Herbarium. http://sweetgum.nybg.org/science/ih/

Vellak K, Ingerpuu N, Kannukene L, Leis M (2009) New Estonian records and amendments: liverworts and mosses. Folia Cryptogam Estonica 45:91–93. https://doi.org/10.12697/issn1406-2070

Zarabska D, Rosadziński S (2011) New records of the lichen species Pycnothella papillaria in Poland in the context of threats to species. Roczniki Akademii Rolniczej w Poznaniu 390. Bot Steciana 15:149–152

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the curators at KRAM, KTU, LBL, LOD, POZG, WA, and WRSL for kindly allowing us to study herbarium specimens of Campylopus introflexus. Very special thanks are due to Mr Arthur Copping (Roydon, Diss, UK) for his kind verification and improvement of the English text. We would like to thank two anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments and suggestions that have helped us improve the final version of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Żarnowiec, J., Stebel, A. & Chmura, D. Thirty-year invasion of the alien moss Campylopus introflexus (Hedw.) Brid. in Poland (East-Central Europe). Biol Invasions 21, 7–18 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10530-018-1818-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10530-018-1818-9