Abstract

Prioritization is indispensable for the management of biological invasions, as recognized by the Convention on Biological Diversity, its current strategic plan, and specifically Aichi Target 9 that concerns invasive alien species. Here we provide an overview of the process, approaches and the data needs for prioritization for invasion policy and management, with the intention of informing and guiding efforts to address this target. Many prioritization schemes quantify impact and risk, from the pragmatic and action-focused to the data-demanding and science-based. Effective prioritization must consider not only invasive species and pathways (as mentioned in Aichi Target 9), but also which sites are most sensitive and susceptible to invasion (not made explicit in Aichi Target 9). Integrated prioritization across these foci may lead to future efficiencies in resource allocation for invasion management. Many countries face the challenge of prioritizing with little capacity and poor baseline data. We recommend a consultative, science-based process for prioritizing impacts based on species, pathways and sites, and outline the information needed by countries to achieve this. This should be integrated into a national process that incorporates a broad suite of social and economic criteria. Such a process is likely to be feasible for most countries.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Invasive species have significant impacts on valued features of the environment, a fact clearly recognized in the current Strategic Plan for Biodiversity of the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) (UNEP 2011). Between 5 and 20 % of alien species are problematic (Vilà et al. 2010; Lockwood et al. 2013) and the impacts of these few are large and persistent. These include negative environmental impacts, such as those on threatened species and ecosystems, as well as socioeconomic impacts (Jeschke et al. 2014). Invasive species can be enormously costly to manage, so resources must be committed to where they are likely to be most cost-effective (Krug et al. 2009). Major challenges arise from the large number of species involved, from distinguishing those that are invasive from those that are not, and the expense of acquiring and assessing the information needed to support decision making (Hulme 2009). Problems and opportunities must therefore be ranked or prioritized, according to the severity of actual and potential impacts on biodiversity and ecosystems (Carrasco et al. 2010; Kumschick et al. 2012).

Prioritization to support cost-effective allocation of resources is part of decision-making at nearly every stage of the invasion process (Fig. 1). For example, pathways may be prioritized for the purpose of preventing the introduction of harmful alien species (pre-invasion or pre-border). Once an invasive alien species (IAS) has arrived and is established (post-invasion or post-border), the focus moves to preventing its spread and to the protection of high-priority sites. When a species with demonstrated impact threatens to spread, prioritization is focused on the feasibility of its eradication or containment (Fig. 1). Species-focused prioritization schemes, mostly for plants, have proliferated, although few of these have developed via the primary literature (Heikkilä 2011). More recently a number of standardized, evidence-based approaches for prioritizing pathways and sites have been proposed that encompass (or have the potential to encompass) a broad suite of alien taxa (Dawson et al. 2015; Essl et al. 2015; Kumschick et al. 2015; McGeoch and Latombe 2015).

Prioritization takes place within and across stages of the invasion process, both before (pre-border) or after (post-border) invasion. It is therefore relevant to prevention and control objectives, and may be supported by a range of analytical decision-support tools (examples shown). Each focus (species, pathways and sites) has particular data requirements (see Table 2). In each case the typical output used in decision making would be a ranking, or ordered set of categories, of those species, pathways or sites where action would most effectively prevent or mitigate the impact of biological invasions (self-organizing maps are an artificial neural network-based, risk assessment method that can contribute to a prioritization scheme, see text)

The Convention on Biological Diversity and its Strategic Plan for Biodiversity 2011–2020, supported by most of the world’s countries, provide an overarching framework for all parties engaged in biodiversity management and policy development to save biodiversity and to enhance its benefits for people (UNEP 2011). One of the Strategic Plan’s 20 Aichi Targets for achieving this aim concerns invasive alien species. Aichi Target 9 stresses the importance of identifying and prioritizing both IAS and their invasion pathways: Invasive alien species and pathways are identified and prioritized, priority species are controlled or eradicated, and measures are in place to manage pathways to prevent their introduction and establishment (UNEP 2011). The goal of the previous 2010 Biodiversity Target for IAS assumed that “major” IAS were already well known and documented (in other words, that they had been identified—with important species distinguished from less important ones). This turned out not to be the case at the country level (McGeoch et al. 2010; Genovesi et al. 2013). The shift of focus in Aichi Target 9 reflects an improved understanding of the nature and extent of global invasion, and appreciation of current gaps in knowledge. The current target therefore concedes that IAS must first be identified and then prioritized at multiple scales, to ensure strategic and effective responses.

Although Aichi Target 9 is aptly focused on a strategic approach to decision-making for control of IAS, several challenges remain. Here we outline the major concepts and approaches to prioritization for policy makers, agencies and scientists working towards achieving and reporting on Aichi Target 9. We argue that any comprehensive and strategic approach to prioritization must include three complementary foci that together enable effective prioritization. Aichi Target 9 identifies two of these, i.e. species and pathways. The third focus, proposed in this paper, is sites at high risk of invasion and of high biodiversity value. We also outline the kinds of country-level information that will be needed for effective assessment and reporting to meet Aichi Target 9 for IAS under the Strategic Plan for Biodiversity 2011–2020.

Prioritization

Here we define prioritization as the process of ranking species, pathways, or sites for the purposes of (1) determining their relative environmental (and sometimes also socio-economic) impacts (sensu Kumschick et al. 2012; Blackburn et al. 2014), and for (2) deciding on the relative priority of actions to effectively and efficiently prevent or mitigate the impact of invasive alien species (Fig. 2). Priority species, pathways, or sites are therefore those that are identified as posing the greatest risk to the environment and biodiversity and, in some cases, also the greatest opportunities for preventing such risk (e.g. Dawson et al. 2015). Stakeholders involved in prioritization therefore include policy makers, regulators, scientists, and managers.

The process of prioritization in biological invasion happens for two distinct purposes and encompasses risk assessment (RA), although both purposes can be addressed simultaneously. Existing prioritization schemes vary widely in the relative emphasis given to one or both of these purposes (see text). Definitions are provided in italics (those modified from Richardson (2011) with an asterisk)

A prioritization scheme (or prioritization model) is any structured system that produces a ranking or ordered set of risk categories. In some cases, it is designed to deal with many species (and potentially also pathways and sites) in a short time without the need for extensive resources (Heikkilä 2011). Prioritization schemes are generally question-driven and score-based, and enable a balanced and transparent approach to decision-making (Sutherland et al. 2006; Benke et al. 2011). They provide a vehicle for generating consistent and comparable outcomes, and for dialogue and information exchange (Brunel et al. 2010). They are also adaptive, and can readily be updated and refined as the available information improves.

Risk assessment and prioritization are closely related processes, but have different specific objectives (Fig. 2; Lonsdale 2011). Risk assessment is the first step in risk management and focuses principally on the quantification of risk per se, whereas prioritization focusses specifically on ranking or categorization of relative risk or relative priorities for action (Pyšek and Richardson 2010; Fig. 2). Risk assessments that underpin prioritization, and that evaluate the likelihood and consequences of invasion, remain strongly evidence-based and dependent on scientific input (Fig. 2). Prioritization is often based on the results of a risk assessment, which may be formal or informal, qualitative, semi-quantitative or quantitative, and is sometimes formally incorporated as the desired end point of a risk assessment process (Fig. 2; Leung et al. 2012). In practice, prioritization often focuses on either impact or action and, in some cases, both simultaneously (Fig. 2; Heikkilä 2011; Kumschick et al. 2012). Although prioritization schemes for decision-support are commonly used in policy environments, they have been less considered in the invasion literature, beyond risk assessments (Heikkilä 2011; Roy et al. 2014). Because prioritization is so central to current global targets for minimizing the impact of invasion on biodiversity, here we define and describe prioritization as applied to invasion biology, and identify developments necessary to achieve Aichi Target 9. We also argue for more comprehensive and standardized prioritization within and across species, pathways and sites.

Prioritization for ranking impact and deciding on actions

Prioritization schemes for assessing relative impact are typically based on a risk assessment (left of Fig. 2). However, with a few exceptions, most risk assessments in invasion biology concern either single species (e.g. Krug et al. 2009), or multiple species in particular regions or within particular taxa (e.g. invasive alien trees and shrubs that pose a threat to particular ecosystems; Roura-Pascual et al. 2009). By contrast, prioritization schemes for action must often simultaneously consider many species, pathways and sites, but nonetheless need to be straightforward and quick to conduct (see right of Fig. 2; Higgins et al. 1997; Heikkilä 2011). Action-focused prioritization schemes therefore rely on appropriately focused and well-synthesized outcomes of risk assessments and impact rankings (Fig. 2). However, in practice action-focused prioritization schemes are not always informed by an independent evidence-based risk assessment, either because data are not readily available, the analysis does not directly address a policy concern, or the process of integrating such assessment into a scheme is too costly and time-consuming (Leung et al. 2002; Thuiller et al. 2005; Drake and Lodge 2006). Quantitative risk assessments are under-used in policy because they tend to be time-demanding, and require more or better quality data than are often available (Andersen 2008; Leung et al. 2012).

Prioritization for action also generally encompasses a broader set of considerations than impacts on the environment (right of Fig. 2; Kumschick et al. 2012). For example, policy-makers and regulators commonly implement schemes to meet explicit regulatory needs (ISPM 2004). In this way, the outcome of an action-focused prioritization process may trigger a decision for further or more detailed risk assessment (arrow from right to left in Fig. 2; Brunel et al. 2010). The time and resources available, as well as the relevant regulatory context, are usually key considerations that drive the way in which the prioritization process for deciding on actions takes place (Liu et al. 2011a, b).

Broad sectors of society can be represented in the process of prioritizing for action, including special-interest groups such as importers, food producers, and hobbyists (Kumschick et al. 2012). A well-known example shows how the decision to remove alien trees must take into account the likely economic consequences of removal for the nearby communities that depend on harvesting them for firewood (de Neergaard et al. 2005). In this way, the needs of stakeholders are taken into account to ensure that the outcomes are relevant, understood, and adopted (Krueger et al. 2012). Prioritization schemes should ideally include consideration of uncertainty in input information and output rankings (Heikkilä 2011). Because existing schemes vary substantially in the extent to which they encompass information, processes or objectives beyond formal risk assessment (i.e. where they fit within Fig. 2; Kumschick et al. 2012), we do not attempt to categorize schemes here. Rather, we focus on schemes that explicitly rank or produce ordered sets of risk categories (i.e. that prioritize) and that have significant potential to contribute to achieving Aichi Target 9 at country or broader scales.

Existing schemes and models

Currently, there are no broadly adopted, standard approaches to prioritizing invasions, but there are several in local or regional use (Table 1). There are several species-based schemes in use, especially for plants (Brunel et al. 2010; Essl et al. 2011). For example, there are over 70 different prioritization schemes for pathogens, pests and weeds (Heikkilä 2011). These schemes differ in how qualitative information was translated into quantitative data, in the weighting of different components (e.g. types of impacts), and in whether uncertainty in the model’s data inputs and outputs is considered. Several policy-driven systems have emerged recently, particularly in Europe, such as Harmonia+ from Belgium (http://ias.biodiversity.be/harmoniaplus), the German-Austrian Black List Information System (Essl et al. 2011), and the European and Mediterranean Plant Protection Organization (EPPO) prioritization process (Brunel et al. 2010). Harmonia+, for example, is the first online scheme for assessing the potential risk of invasive alien species that is applicable across taxonomic groups and environments and supported by a rigorous scientific set of protocols.

In the context of Aichi Target 9, relevant societal values, available resources for management, and the size and nature of invasion risks vary significantly across countries (Pyšek et al. 2008; McGeoch et al. 2010). As a result, the context for prioritization can vary widely in scope and objective, and individual countries decide what levels of risk are acceptable (ISPM 2004). However, risk assessment is needed across countries because of accelerating rates of international trade, travel, and transport (Pyšek et al. 2010). For example, an introduced species may be unlikely to become invasive in one country because of local environmental conditions, but it may act as a stepping stone for the species to become invasive in other countries. Therefore formal prioritization schemes (such as those listed in Table 1) are essential for effective invasion policy and management. Also, for generating globally comparable data for developing appropriate policy and internationally co-ordinated interventions, widely adopted standardized approaches are desirable. Below we provide a description of prioritization for species, pathways and sites, as well as key examples and recently proposed schemes.

Three foci for prioritization: species, pathways, and sites

Targeting species, pathways and sites for prioritization is necessary to enable effective invasion policy and management (Fig. 3). Aichi Target 9 explicitly mentions the first two foci; we now provide a description and examples of all three, and then argue for the necessity of integrating priorities across all three for the most effective interventions. Finally, we suggest that integrated prioritization across these three foci would lead to improved outcomes and efficiencies in resource allocation.

The three foci for a comprehensive approach to prioritizing investment in management of biological invasions. Examples of combined prioritized risks associated with these focus areas, with the example in the centre being ornamental species in gardens as escapees (pathway) into adjacent protected areas (sites)

Prioritizing species

Species-based prioritization is the most common and best-developed of the three focus areas, with by far the largest number of existing models (Fig. 3; Heikkilä 2011; Kumschick et al. 2012, 2015). Currently, no single method is broadly adopted (Brunel et al. 2010). However, most schemes consider which alien species, and which traits, are associated with the greatest negative impacts on the economy, society, ecosystems, habitats, or native species. For example, impact-focused prioritization (Fig. 2) often uses species distribution models that incorporate climate suitability to assess risk (e.g. Sheppard et al. 2014). As reviewed by Pyšek and Richardson (2010), several analytical approaches have been used to conduct risk assessments to produce outputs that enable ranking (i.e. prioritization based on relative risk), particularly pre-border, and there are a number of species-based risk assessment frameworks for biosecurity (e.g. ISPM 2004; Baker et al. 2008; EPPO 2011; Generic Impact Scoring System (GISS) of Kumschick et al. 2012, 2015). Here we provide examples of some of the most common, recent and prioritization-relevant examples.

Prioritization using multi-criteria decision analysis (MCDA) has been widely used, especially for invasive plant species (Benke et al. 2011; Liu et al. 2011a). For example, the EPPO’s action-focused scheme applies MCDA to lists of alien plants in Europe, or at risk of entering it. The scheme is designed for rapid assessment of potential invasive plants, identified by scores on eight initial questions (Brunel et al. 2010). Three further questions can then be posed, to identify species for which a more detailed pest risk assessment should be conducted. A scheme called weeds of national significance (WoNS) is another action-focused and species-based system for weeds with substantial impact in Australia (Fig. 4; Thorp and Lynch 2000). This scheme has provided a basis for channeling investment in the management of major invasive species across the country (Thorp and Lynch 2000). Under WoNS, agencies with responsibility for weed management can nominate a number of species of high impact in their jurisdictions, based on multiple criteria that include ecological, agricultural and socioeconomic impacts that are scored and weighted to provide an overall weighting (Fig. 4). Question- and score-based approaches, such as WoNS and other structured decision-making models (e.g. Figure 1 in McGeoch et al. 2012), enable repeatable and transparent prioritization when the available information is inadequate (Essl et al. 2011; Heikkilä 2011; Leung et al. 2012).

The weeds of national significance (WoNS) model, showing the relationship and maximum weightings for all variables used in ranking the weeds of national significance in Australia. Modified with permission from Thorp and Lynch (2000)

Another approach for multi-species prioritization at a national level uses artificial neural networks (such as self-organizing maps) to estimate the likelihood of species establishment in a given country (Worner and Gevrey 2006; Paini et al. 2010). Assemblages of co-occurring invasive species from potential source regions are used to identify and prioritize new species threats for the region of interest. The application of a neural network algorithm, known as self-organized mapping (SOM), to the known occurrence of over 800 insect pests in over 450 geographic regions allowed each species to be ranked in terms of its likelihood of invading each particular region (Worner and Gevrey 2006). This ranking is based on the strength of association (likelihood of co-occurrence) of each species with the pest assemblage of each particular region.

Most recently a species-based and impact-focused scheme has been proposed that assigns alien species to five semi-quantitative, sequential categories, ranging from minimal to massive impact (Blackburn et al. 2014). Classification is based on a fixed set of mechanisms by which species cause impacts, including for example, competition or hybridization with native taxa, disease transmission and biofouling. This scheme (Environmental Impact Classification for Alien Taxa, EICAT) provides a transparent, standardized, and effective approach that can also be applied to a diverse range of taxa (across plants and animals) and differing types and quality of available evidence (Table 2). EICAT is now being refined for Aichi Target 9 and as it undergoes testing and further development is likely to be widely adopted (Hawkins et al. 2015).

Prioritizing invasion pathways

Species are introduced either intentionally or unintentionally. For unintentional introductions, species-based prioritization is not always feasible because which species will arrive is difficult to predict, and the biology and life history of the species that do arrive are sometimes poorly known (Leung et al. 2014). The focus on species must therefore be balanced with a focus on pathways of introduction and spread, with the purpose of preventing the propagules that they carry from arriving and spreading (Fig. 3; Hulme 2009).

Prioritization of pathways uses information on the full suite of vectors and routes by which alien propagules are introduced, and the propagule loads of such pathways (Carlton and Ruiz 2005; Hulme et al. 2008; Essl et al. 2015). For example, a risk assessment of pathways into the Antarctic found high propagule loads for fresh produce (especially leafy produce; Hughes et al. 2011), infrastructure development activities, and entrainment on the clothing of visiting tourists and scientists (Chown et al. 2012). This knowledge has allowed five particular pathways of introduction to the region to be prioritized for management (COMNAP 2014). There are two ways in which a particular pathway may be prioritized: (1) according to the number of different invasive species that are introduced and spread by the pathways, and (2) based on the severity of the impact caused by the invasive species introduced and spread by the pathway (Essl et al. 2015). The latter would use species risk assessment information to determine which pathways are associated with species with the greatest magnitude of impact.

A framework that categorizes pathways is needed to compare data within regions and across countries, and also to facilitate regulatory approaches that have to deal with the many potential taxon–pathway combinations (Table 2; Essl et al. 2015). Hulme et al. (2008) outlined 32 different pathways of introduction (associated with agriculture, forestry, or the nursery trade for example). A more detailed categorization of pathways, largely based on the system proposed by Hulme et al. (2008), has been developed by the IUCN Invasive Species Specialist Group, and endorsed by the CBD (UNEP 2014; Essl et al. 2015). This hierarchical system of categorization encompasses three broad mechanisms: importation of a commodity, arrival of a transport vector, and spread from a neighbouring region. These are further subdivided into six principal pathway categories: intentional release, escape from containment, transport as a contaminant, transport as a stowaway, spread through corridors, and spread through unaided natural dispersal (Essl et al. 2015). Application of this framework to 500 invasive alien species in the Global Invasive Species Database revealed, for example, that horticultural and pet and aquarium escapees were the most frequent pathways by which invasive species are introduced and spread (Chang et al. 2009; Roy et al. 2014). Parties to the CBD have called for the use of this pathway framework for the purpose of assessing and prioritizing the risk posed by pathways (UNEP 2014), which will facilitate the reporting envisaged in Aichi Target 9.

Prioritizing susceptible and sensitive sites

The motivation for site-based prioritization is that the risk of entry and establishment by invasive species is unevenly distributed across landscapes and regions (Yemshanov et al. 2013). Site-based prioritization focuses on two broad categories of sites (Fig. 5). First, those sites most likely to be invaded, i.e. susceptible sites, include sites that are most exposed to invasion, such as those associated with high human activity (high exposure). Susceptible sites are also areas where invasive species are likely to establish and spread (invasible areas, sensu Catford et al. 2011), such as highly disturbed areas (D’Antonio et al. 1999), or those surrounded by high population density (Spear et al. 2013). For example, Gallardo and Aldridge (2013) quantified the risk of establishment and spread of 16 aquatic species in Britain using multiple modelling approaches, including climate matching. The results for all 16 species were integrated to produce heat maps to identify areas with the highest vulnerability of invasion. In other words, susceptible sites are those where there is both a high probability of an invasive species arriving along with conditions that favour survival and establishment (Fig. 5).

Sites can also be prioritized based on their vulnerability to the impact of invasions if it happens, i.e. sensitive sites (Fig. 5). Sites where the consequences of any impact are significant and where invasion is particularly undesirable can be considered sensitive to invasion and prioritized for management attention for this reason. In addition, functionally important sites, such as water catchments, wetlands, and waterways, are often priorities for management of multiple alien plant taxa (Fig. 5; Table 2; Bobeldyk et al. 2015). Sites may be sensitive, for example, because of their high conservation status or functional importance (Fig. 5; Keith et al. 2013). Sites generally sensitive to invasion include protected areas (Tu 2009) or those with high conservation value: for example, those that support one or more threatened taxa. Islands are another well-known example of sensitive sites, where introduced mammals have a disproportionately severe impact on native fauna (for recent example see Walsh et al. 2012).

Both susceptible and sensitive sites can be prioritized for prevention, and one particular site may be simultaneously both susceptible and sensitive. One example of the latter is riparian areas in some systems, which are highly exposed to water borne propagules (Foxcroft et al. 2008) and invasion is particularly undesirable because of the negative impact of woody alien plants on water flow (Le Maitre et al. 1996, 2014). Another example of site-based prioritization involves a new industrial development on Barrow Island, off the north-western coast of Australia (Whittle et al. 2013). Surveillance at this site is aimed at preventing the introduction and establishment of invasive invertebrates. Parts of the island are now susceptible as a result of development related disturbance and the import of goods and materials. The island itself is sensitive and has high protection status as a result of its diverse, comparatively intact mammal and reptile fauna. Expert input was used to generate risk maps and the susceptible zones that were prioritized as a result include the accommodation camp, the airstrip, and the barge landing (Whittle et al. 2013).

The invasibility of sites is rarely singled out to be quantified (Catford et al. 2011), but in practice, species and site prioritization happen simultaneously (Forsyth et al. 2012; Roura-Pascual et al. 2009), although spatial heterogeneity is seldom explicitly incorporated into prioritization models (Leung et al. 2012). Heat maps have been used with species distribution models, along with information on climate suitability to identify areas most vulnerable to multi-species invasion (Gallardo and Aldridge 2013). A specific site-focused approach was recently developed to prioritize islands for the eradication of invasive vertebrates (Dawson et al. 2015). This scheme takes into account the conservation value of each island, the feasibility of eradication and the risk of natural reinvasion. From this an index of eradication benefit is calculated as the difference between the conservation value of the island and feasibility of long-term eradication success. In the marine environment, combined information on global movements of cargo ships and environmental conditions and biogeography of ports has enabled identification of high-risk invasion routes and invasion hot spots (Keller et al. 2011; Seebens et al. 2013).

No guidelines for a common approach to site-based prioritization have yet been proposed, but is necessary as part of the process towards optimal prioritization of biological invasions. Because it is not explicitly covered by Aichi Target 9 it has received less policy attention. But sites clearly form an essential third focus area to ensure maximally effective invasion management (Andersen et al. 2004). As the examples provided above show, this is often implicitly recognized in practice along with the consideration of species and pathways. Susceptible and sensitive sites will necessarily be highly context dependent and a function of, for example, climate, disturbance history and how countries or local communities place value on particular landscapes. Nonetheless, the identification and prioritization of sites under these two categories provides an important, complementary approach to prioritizing species and pathways. In Table 2 we list the basic data requirements and some key questions for initiating the identification and classification of priority sites for invasion policy and management.

Integrated prioritization of species, pathways, and sites

Very little attention has been paid to making integrated prioritization more explicit, i.e. quantitative integration of priorities across multiple species, pathways, and sites (centre of Fig. 3; Brunel et al. 2010), although pairwise risk assessment and prioritization is more common [e.g. species by pathways (NOBANIS 2015), and pathways by sites (Chown et al. 2012)]. Three-way prioritization would involve identifying combinations of factors that jointly warrant priority attention, regardless of how the component factors have been classified. Questions that have been little addressed to date include which pathways are associated with the introduction of multiple highest-priority species at which sensitive sites, or which sites (or categories of sites) are most susceptible to invasion by those same species?

Some progress has been made with invasion-syndrome hypotheses that relate site conditions to characteristic suites of invasive species (Perkins and Nowak 2013). Recently Bobeldyk et al. (2015) showed that invertebrate introductions into the US were predominantly associated with ballast water, whereas fish introductions were largely via aquaria and aquaculture (i.e. considering species and pathway priorities). In another case, spatially explicit prioritization was conducted for the most important invasive alien plant species in a South African fynbos ecosystem (i.e. considering species by site priorities; Roura-Pascual et al. 2009). Integrated prioritization across multiple species, pathways, and sites however deserves far more attention (Andersen et al. 2004). If evidence is found in support of species-pathway-site syndromes, then integrated prioritization promises improved efficiencies in the allocation of resources to manage invasions.

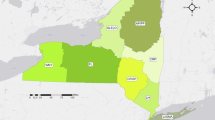

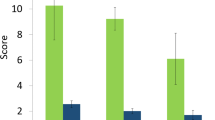

When data and capacity are inadequate

Prioritization is crucial not only as the cornerstone of Aichi Target 9, but because it enables improvements in the efficiency of invasion policy and management, regardless of the quantity or quality of data. While some countries have substantial data, along with evidence generated by sophisticated risk analyses, others must prioritize from limited baseline information and scant risk-analysis evidence (McGeoch et al. 2010). For example, of 170 countries that submitted reports under the terms of the CBD (Fourth National Reports, 2010–2013; www.cbd.int/reports/nr4), 15 % admitted to having insufficient information or capacity to report adequately on biological invasions (Fig. 6). An assessment of the content of invasive species information in these reports revealed that on aggregate, 43 % of countries had either instances of incorrect or inconsistent nomenclature (26 %), ambiguous common names (35 %), or species listed as alien invasives that were native to the country (8 %) (Fig. 6). This compromises the ability of countries to accurately report on progress toward Aichi Target 9. Even when countries are data-rich, prioritization is essential and data are not always adequate to do so (Bobeldyk et al. 2015). Conducting empirical risk assessments for every possible species, pathway and site is time-consuming, costly, and generally not feasible. This analysis of national reporting to the CBD illustrates that there is still some way to go to countries delivering evidence-based prioritization of species and pathways for reporting on Aichi Target 9.

The number of invasive alien species (IAS) mentioned in the Fourth National Reports, for 170 countries, submitted by these parties to the Convention on Biological Diversity (2010–2013, www.cbd.int/reports/nr4). All information on alien and invasive species was extracted from these reports, summarized, analyzed, and assessed to provide the basic statistics provided in the present paper. Grey shading represents those countries that refer to some external list of IAS for the country in addition to species mentioned in the Fourth National Reports

Although evidence-based input is highly desirable, prioritization is possible in cases where data are scarce. Even without baseline data on priority species, pathways, and sites, the combined use of expert opinion and evidence from elsewhere can help prioritization activities (Table 2). For example, species that typically cause the greatest impacts are often well-known, even for countries with little or incomplete information on the actual invasive species that threaten (Fig. 6; Hayes and Barry 2008). Species known to be invasive in neighboring countries may reasonably be considered high-risk by default (Paini et al. 2010). The impact classification scheme, EICAT, proposes a global assessment where the category to which a species is assigned is based on the maximum ever, or maximum current, impact recorded for the species anywhere (Blackburn et al. 2014; Hawkins et al. 2015). There are also rules of thumb about high-risk introduction pathways, and also about vulnerable sites (Leung et al. 2012). Similarly, many countries have information on the relative values of land for production and conservation that can feed into prioritization schemes (Nelson et al. 2009).

Priorities generated under data-poor conditions may be unstable. They can shift significantly as more and better-quality data become available. Priorities may also be founded on subjective impressions, or be swayed by political influence, context dependence, and motivational bias (Burgman et al. 2005). Most importantly, conservation investment based on priorities fed by poor data is more likely to fall short of its targets. With the aim of making quality data management for prioritization accessible to all countries, the most cost-effective way is to support existing international databases and information systems (Amano and Sutherland 2013; Costello and Wieczorek 2014; Costello et al. 2013, 2014). The starting point would be a world list of invasive species with a standardized nomenclature. To meet this need, the global register of introduced and invasive species (GRIIS) is under development: an initiative of the IUCN SSC Invasive Species Specialist Group (ISSG). This falls within the framework of the Global Invasive Alien Species Partnership (GIASIP), as does the World Register of Introduced Marine Species (WRIMS, Pagad et al. 2015) which is part of the World Register of Marine Species (Costello et al. 2013). GIASIP was formed to assist parties to the CBD in implementing Aichi Target 9. Although there are many regional and global initiatives and partnerships to support knowledge management and good data practices for invasive species (Costello and Wieczorek 2014), few of these provide the outcome of prioritization exercises per se. Most include information on species only, not on pathways or sites. There is however a minimum information set needed (see Pereira et al. 2013) to integrate species, pathway and site information to achieve Aichi Target 9 that all countries will need access to, supported and supplemented by more comprehensive data and analysis where possible (Table 2; Blackburn et al. 2014). Table 2 lists a set of data needs, and possible surrogates in the case where countries do not have such data, for species, pathways and sites. For example, knowing which species are already present, and the range of relevant pathways by which they are likely to be entering and spreading across the country are certainly essential baseline information.

Conclusion

Aichi Target 9 for biological invasions has policy and resource management implications for countries. Prioritization enables best use of available data and information. We propose that an internationally-agreed system of prioritization, based on species, pathways, and sites, and underpinned by quality assured databases, is the most cost-effective way forward. Existing systems focus on species and pathways. We propose that guidelines are developed for site-based prioritization, because this is essential for countries to satisfy Aichi Target 9 and to achieve harmonized global reporting. Prioritization is clearly relevant for invasive species, invasion pathways, and susceptible and sensitive sites, although little attention has been paid to integrating priorities across the three foci. Such attention may well lead to further efficiencies. Regardless of the quantity and quality of the available raw information, prioritization schemes enable it to be processed rationally for transparent and repeatable outcomes.

References

Amano T, Sutherland WJ (2013) Four barriers to the global understanding of biodiversity conservation: wealth, language, geographical location and security. Proc R Soc B Biol Sci. doi:10.1098/rspb.2012.2649

Andersen MC (2008) The roles of risk assessment in the control of invasive vertebrates. Wildl Res 35:242–248

Andersen MC, Adams H, Hope B, Powell M (2004) Risk analysis for invasive species: general framework and research needs. Risk Anal 24:893–900

Baker RHA, Black R, Copp GH et al (2008) The UK risk assessment scheme for all non-native species. Neobiota 7:46–57. http://eprints.bournemouth.ac.uk/9721/1/baker_etal.pdf

Benke KK, Steel JL, Weiss JE (2011) Risk assessment models for invasive species: uncertainty in rankings from multi-criteria analysis. Biol Invasions 13:239–253

Blackburn TM, Essl F, Evans T et al (2014) A unified classification of alien species based on the magnitude of their environmental impacts. PLoS Biol. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1001850

Bobeldyk AM, Rueegg J, Lamberti GA (2015) Freshwater hotspots of biological invasion are a function of species-pathway interactions. Hydrobiologia 746:363–373

Brunel S, Branquart E, Fried G et al (2010) The EPPO prioritization process for invasive alien plants. EPPO Bull 40:407–422

Burgman MA, Lindenmayer DB, Elith J (2005) Managing landscapes for conservation under uncertainty. Ecology 86:2007–2017

Carlton JT, Ruiz JA (2005) Vector science and integrated vector management in bioinvasion ecology: conceptual frameworks. In: Mooney HA, Mack RN, McNeely JA et al (eds) Invasive alien species. A new synthesis. Island Press, Washington, pp 36–58

Carrasco LR, Mumford JD, MacLeod A et al (2010) Comprehensive bioeconomic modelling of multiple harmful non-indigenous species. Ecol Econ 69:1303–1312

Catford JA, Vesk PA, White MD, Wintle BA (2011) Hotspots of plant invasion predicted by propagule pressure and ecosystem characteristics. Divers Distrib 17:1099–1110

Champion PD, Clayton JS (2001) A weed risk assessment model for aquatic weeds in New Zealand. In: Groves RH, Panetta FD, Virtue JG (eds) Weed risk assessment. CSIRO, Melbourne, pp 194–202

Chang AL, Grossman JD, Spezio TS et al (2009) Tackling aquatic invasions: risks and opportunities for the aquarium fish industry. Biol Invasions 11:773–785

Chown SL, Huiskes AHL, Gremmen NJM et al (2012) Continent-wide risk assessment for the establishment of nonindigenous species in Antarctica. PNAS 109:4938–4943

Collauti RI, Parker JD, Cadotte MW et al (2014) Quantifying the invasiveness of species. NeoBiota 21:7–27

COMNAP (Council of Managers of National Antarctic Programmes) (2014) Checklists for supply chain managers of National Antarctic Programmes for the reduction in risk of transfer of non-native species. www.comnap.aq/Shared%20Documents/checklistsposter.pdf

Costello MJ, Wieczorek J (2014) Best practice for biodiversity data management and publication. Biol Conserv 173:68–73

Costello MJ, Bouchet P, Boxshall G et al (2013) Global coordination and standardisation in marine biodiversity through the World Register of Marine Species (WoRMS) and related databases. PLoS ONE 8:e51629. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0051629

Costello MJ, Appeltans W, Bailly N et al (2014) Strategies for the sustainability of online open-access biodiversity databases. Biol Conserv 173:155–165

D’Antonio CM, Dudley TL, Mack M (1999) Disturbance and biological invasions: direct effects and feedbacks. In: Walker LR (ed) Ecosystems of disturbed ground. Elsevier, Amsterdam, pp 413–452

D’hondt B, Vanderhoeven S, Roelandt S et al (2015) Harmonia + and Pandora +: risk screening tools for potentially invasive plants, animals and their pathogens. Biol Invasions 17:1869–1883

DAISIE (2009) Handbook of alien species in Europe, delivering alien invasive species in Europe. Springer, Dordrecht

Dawson J, Oppel S, Cuthbert R et al (2015) Prioritizing islands for the eradication of invasive vertebrates in the UK overseas territories. Conserv Biol 29:143–153

de Neergaard A, Saarnak C, Hill T et al (2005) Australian wattle species in the Drakensberg region of South Africa—an invasive alien or a natural resource? Agric Syst 85:216–233

Downey PO (2010) Managing widespread, alien plant species to ensure biodiversity conservation: a case study using an 11-step planning process. Invasive Plant Sci Manag 3:451–461

Drake JM, Lodge DM (2006) Allee effects, propagule pressure and the probability of establishment: risk analysis for biological invasions. Biol Invasions 8:365–375

EPPO (2011) Guidelines on pest risk analysis: decision support scheme for quarantine pests. European and Mediterranean Plant Protection Organization Europe, Paris

Essl F, Dullinger S, Rabitsch W et al (2011) Socioeconomic legacy yields an invasion debt. PNAS 108:203–207

Essl F, Bacher S, Blackburn TM et al (2015) Crossing frontiers in tackling pathways of biological invasions. Bioscience 65:769–782

Forsyth GG, Le Maitre DC, O’Farrell PJ et al (2012) The prioritization of invasive alien plant control projects using a multi-criteria decision model informed by stakeholder input and spatial data. J Environ Manage 103:51–57

Foxcroft LC, Parsons M, McLoughlin CA, Richardson DM (2008) Patterns of alien plant distribution in a river landscape following an extreme flood. S Afr J Bot 74:463–475

Gallardo B, Aldridge DC (2013) Priority setting for invasive species management: risk assessment of Ponto-Caspian invasive species into Great Britain. Ecol Appl 23:352–364

Genovesi P, Butchart SHM, McGeoch MA, Roy DB (2013) Monitoring trends in biological invasion, its impact and policy responses. In: Collen B, Pettorelli N, Baillie JEM, Durant SM (eds) Biodiversity monitoring and conservation: bridging the gap between global commitment and local action. Wiley, Chichester, pp 138–158

Gordon DR, Gantz CA, Jerde CL, Chadderton WL, Keller RP, Champion PD (2012) Weed risk assessment for aquatic plants: modification of a New Zealand system for the United States. PLoS ONE 7:e40031

Harris DB, Gregory SD, Bull LS, Courchamp F (2012) Island prioritization for invasive rodent eradications with an emphasis on reinvasion risk. Biol Invasions 14:1251–1263

Hawkins CL, Bacher S, Essl F et al (2015) Framework and guidelines for implementing the proposed IUCN environmental impact classification for alien taxa (EICAT). Divers Distrib. doi:10.1111/ddi.12379

Hayes KR, Barry SC (2008) Are there any consistent predictors of invasion success? Biol Invasions 10:483–506

Heikkilä J (2011) A review of risk prioritization schemes of pathogens, pests and weeds: principles and practices. Agric Food Sci 20:15–28

Higgins SI, Azorin EJ, Cowling RM et al (1997) A dynamic ecological–economic model as a tool for conflict resolution in an invasive-alien-plant, biological control and native-plant scenario. Ecol Econ 22:141–154

Hughes KA, Lee JE, Tsujimoto M et al (2011) Food for thought: risks of non-native species transfer to the Antarctic region with fresh produce. Biol Conserv 144:1682–1689

Hulme PE (2009) Trade, transport and trouble: managing invasive species pathways in an era of globalization. J Appl Ecol 46:10–18

Hulme PE, Bacher S, Kenis M et al (2008) Grasping at the routes of biological invasions: a framework for integrating pathways into policy. J Appl Ecol 45:403–414

ISPM (2004) Pest risk analysis for quarantine pests including analysis of environmental risks and living modified organisms. International standards for phytosanitary measures, secretariat of the international plant protection convention, ISPM no. 11

Jeschke JM, Bacher S, Blackburn TM et al (2014) Defining the impact of non-native species. Conserv Biol 28:1188–1194

Keith DA, Rodríguez JP, Rodríguez-Clark KM et al (2013) Scientific foundations for an IUCN red list of ecosystems. PLoS ONE. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0062111

Keller RP, Drake JM, Drew MB, Lodge DM (2011) Linking environmental conditions and ship movements to estimate invasive species transport across the global shipping network. Divers Distrib 17:93–102

Khuroo AA, Reshi ZA, Rashid I et al (2011) Towards an integrated research framework and policy agenda on biological invasions in the developing world: a case-study of India. Environ Res 111:999–1006

Kolar CS (2004) Risk assessment and screening for potentially invasive fish. N Z J Mar Freshwater Res 38:391–397

Kolar CS, Lodge DM (2002) Ecological predictions and risk assessment for alien fishes in North America. Science 298:1233–1236

Krueger T, Page T, Hubacek K, Smith L, Hiscock K (2012) The role of expert opinion in environmental modelling. Environ Model Softw 36:4–18

Krug RM, Roura-Pascual N, Richardson DM (2009) Prioritising areas for the management of invasive alien plants in the CFR: different strategies, different priorities? S Afr J Bot 75:408–409

Kumschick S, Bacher S, Dawson W, Heikkilä J, Sendek A, Pluess T, Robinson TB, Kuhn I (2012) A conceptual framework for prioritization of invasive alien species for management according to their impact. NeoBiota 15:69–100

Kumschick S, Bacher S, Evans T et al (2015) Comparing impacts of alien plants and animals in Europe using a standard scoring system. J Appl Ecol 52:552–561

Le Maitre DC, van Wilgen BW, Chapman RA et al (1996) Invasive plants and water resources in the Western Cape Province, South Africa: modelling the consequences of a lack of management. J Appl Ecol 33:161–172

Le Maitre DC, Kotzee IM, O’Farrell PJ (2014) Impacts of land-cover change on the water flow regulation ecosystem service: invasive alien plants, fire and their policy implications. Land Use Policy 36:171–181

Leung B, Lodge DM, Finnoff D, Shogren JF, Lewis MA, Lamberti G (2002) An ounce of prevention or a pound of cure: bioeconomic risk analysis of invasive species. Proc R Soc B Biol Sci 269:2407–2413

Leung B, Roura-Pascual N, Bacher S et al (2012) TEASIng apart alien species risk assessments: a framework for best practices. Ecol Lett 15:1475–1493

Leung B, Springhorn MR, Turner JA, Brockerhoff G (2014) Pathway-level risk analysis: the net present value of an invasive species policy in the US. Front Ecol Environ 12:273–279

Liu S, Sheppard A, Kriticos D et al (2011a) Incorporating uncertainty and social values in managing invasive alien species: a deliberative multi-criteria evaluation approach. Biol Invasions 13:2323–2337

Liu S, Hurley M, Lowell KE, Siddique A-BM, Diggle A, Cook DC (2011b) An integrated decision-support approach in prioritizing risks of non-indigenous species in the face of high uncertainty. Ecol Econ 70:1924–1930

Lockwood JL, Hoopes MF, Marchetti MP (2013) Invasion ecology. Wiley, West Sussex

Lonsdale M (2011) Risk assessment and prioritization. In: Simberloff D, Rejmanek M (eds) Encyclopedia of biological invasions. University of California Press, Oakland, pp 604–609

McGeoch MA, Latombe G (2015) Characterizing common and range expanding species. J Biogeogr. doi:10.1111/jbi.12642

McGeoch MA, Butchart SHM, Spear D et al (2010) Global indicators of biological invasion: species numbers, biodiversity impact and policy responses. Divers Distrib 16:95–108

McGeoch MA, Spear D, Kleynhans EJ et al (2012) Uncertainty in invasive alien species listing. Ecol Appl 22:959–971

Molnar JL, Gamboa RL, Revenga C, Spalding MD (2008) Assessing the global threat of invasive species to marine biodiversity. Front Ecol Environ 6:485–492

Nelson E, Mendoza G, Regetz J et al (2009) Modeling multiple ecosystem services, biodiversity conservation, commodity production, and tradeoffs at landscape scales. Front Ecol Environ 7:4–11

NOBANIS European Network on Invasive Alien Species (2015) Invasive alien species pathway analysis and horizon scanning for countries in Northern Europe. Nordic Council of Ministers, Copenhagen. doi:10.6027/TN2015-517

Pagad S, Hayes K, Katsanevakis S, Costello MJ (2015) World Register of Introduced Marine Species (WRIMS). http://www.marinespecies.org/introduced. 23 Mar 2015

Paini DR, Worner SP, Cook DC et al (2010) Using a self-organizing map to predict invasive species: sensitivity to data errors and a comparison with expert opinion. J Appl Ecol 47:290–298

Pereira HM, Ferrier S, Walters M et al (2013) Essential biodiversity variables. Science 339:277–278

Perkins LB, Nowak RS (2013) Invasion syndromes: hypotheses on relationships among invasive species attributes and characteristics of invaded sites. J Arid Land 5:275–283

Pheloung PC, Williams PA, Halloy SR (1999) A weed risk assessment too for use as a biosecurity tool evaluating plant introductions. J Environ Manage 57:239–251

Pyšek P, Richardson DM (2010) Invasive species, environmental change and management, and health. Annu Rev Environ Res 35:25–55

Pyšek P, Richardson DM, Pergl J, Jarosik V, Sixtova Z, Weber E (2008) Geographical and taxonomic biases in invasion ecology. Trends Ecol Evol 23:237–244

Pyšek P, Jarošík V, Hulme PE et al (2010) Disentangling the role of environmental and human pressures on biological invasions across Europe. PNAS 107:12157–12162

Richardson DM (ed) (2011) Fifty years of invasion ecology: the legacy of Charles Elton. Wiley, Chichester

Roura-Pascual N, Richardson DM, Krug RM et al (2009) Ecology and management of alien plant invasions in South African fynbos: accommodating key complexities in objective decision making. Biol Conserv 142:1595–1604

Roy HE, Peyton J, Aldridge DC et al (2014) Horizon scanning for invasive alien species with the potential to threaten biodiversity in Great Britain. Glob Change Biol 20:3859–3871

Seebens H, Gastner MT, Blasius B (2013) The risk of marine bioinvasion caused by global shipping. Ecol Lett 16:782–790

Sheppard CS, Burns BR, Stanley MC (2014) Predicting plant invasions under climate change: are species distribution models validated by field trials? Glob Change Biol 20:2800–2814

Singh SK, Ash GJ, Hodda M (2015) Keeping ‘one step ahead’ of invasive species: using an integrated framework to screen and target species for detailed biosecurity risk assessment. Biol Invasions 17:1069–1086

Spear D, Foxcroft LC, Bezuidenhout H et al (2013) Human population density explains alien species richness in protected areas. Biol Conserv 159:137–147

Sutherland WJ, Armstrong-Brown S, Armsworth PR et al (2006) The identification of 100 ecological questions of high policy relevance in the UK. J Appl Ecol 43:617–627

Thorp JR, Lynch R (2000) The determination of weeds of national significance. National Weeds Strategy Executive Committee, Launceston

Thuiller W, Richardson DM, Pyšek P, Midgley GF, Hughes GO, Rouget M (2005) Niche-based modelling as a tool for predicting the risk of alien plant invasions at a global scale. Glob Change Biol 11:2234–2250

Tu M (2009) Assessing and managing invasive species within protected areas. The Nature Conservancy, Arlington

UNEP (2011) The strategic plan for biodiversity 2011–2020 and the Aichi biodiversity targets. UNEP/CBD/COP/DEC/X/2, 29 October 2010, Nagoya, Japan. COP CBD Tenth Meeting. www.cbd.int/decisions/cop/?m=cop-10

UNEP (2014) Pathways of introduction of invasive species, their prioritization and management. UNEP/CBD/SBSTTA/18/9/Add.1, subsidiary body on scientific, technical and technological advice, eighteenth meeting, Montreal. www.cbd.int/doc/meetings/sbstta/sbstta-18/official/sbstta-18-09-add1-en.pdf. Decision XII/17 CBD COP12

Van Wilgen NJ, Roura-Pascal N, Richardson DM (2009) A quantitative climate-match score for risk-assessment screening of reptile and amphibian introductions. Environ Manage 44:590–607

Vander Zanden MJ, Olden JD (2008) A management framework for preventing the secondary spread of aquatic invasive species. Can J Fish Aquat Sci 65:1512–1522

Vilà M, Basnou C, Pyšek P et al (2010) How well do we understand the impacts of alien species on ecosystem services? A pan-European, cross-taxa assessment. Front Ecol Environ 8:135–144

Walsh JC, Venter O, Watson JEM, Fuller RA, Blackburn TM, Possingham HP (2012) Exotic species richness and native species endemism increase the impact of exotic species on Islands. Glob Ecol Biogeogr 21:841–850

Whittle PJL, Stoklosa R, Barrett S et al (2013) A method for designing complex biosecurity surveillance systems: detecting non-indigenous species of invertebrates on Barrow Island. Divers Distrib 19:629–639

Wilson JRU, Dormontt EE, Prentis PJ et al (2009) Something in the way you move: dispersal pathways affect invasion success. Trends Ecol Evol 24:136–144

Worner SP, Gevrey M (2006) Modelling global insect pest species assemblages to determine risk of invasion. J Appl Ecol 43:858–867

Yemshanov D, Koch FH, Ducey M et al (2013) Mapping ecological risks with a portfolio-based technique: incorporating uncertainty and decision-making preferences. Divers Distrib 19:567–579

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Group on Earth Observation Biodiversity Observation Network (GEO BON) (www.earthobservations.org/geobon.shtml). MM acknowledges the support of a Monash University Larkins Fellowship and the Australian Research Council’s Discovery Projects funding scheme (Project Number DP150103017). PJB was supported by core funding from New Zealand’s Ministry for Business, Innovation and Employment to Landcare Research. Thanks to Guillaume Latombe for comments and discussion.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

McGeoch, M.A., Genovesi, P., Bellingham, P.J. et al. Prioritizing species, pathways, and sites to achieve conservation targets for biological invasion. Biol Invasions 18, 299–314 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10530-015-1013-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10530-015-1013-1