Abstract

Laetiporus sulphureus is a source of α-1,3-glucan that can substitute for the commercially-unavailable streptococcal mutan used to induce microbial mutanases. The water-insoluble fraction of its fruiting bodies from 0.15 to 0.2% (w/v) induced mutanase activity in Paenibacillus sp. MP-1 at 0.35 μ ml−1. The mutanase extensively hydrolyzed streptococcal mutan, giving 23% of saccharification, and 83% of solubilization of glucan after 6 h. It also degraded α-1,3-polymers of biofilms, formed in vitro by Streptococcus mutans, even after only 3 min of contact.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Dental plaque is a biofilm formed by the adhesion of Streptococcus mutans and other bacterial cells to the tooth surface. This adhesion is mediated by extracellular polysaccharides (EPS), whose important components are homopolymers, such as mutans (α-1,3-glucans) produced by cariogenic streptococci. EPS are mostly water-insoluble and have a complex structure. They promote selective adherence and accumulation of mutans streptococci on teeth, and increase the bulk, and porosity of dental plaque (Paes Leme et al. 2006). Formation of dental plaque leads to dental caries, and other oral diseases, but enzymatic hydrolysis of mutans can prevent, and/or remove dental biofilm. Degradation of α-1,3-glucans can be performed by two types of enzymes; endomutanases (EC 3.2.1.59) and exomutanases (EC 3.2.1.84), which release short oligosaccharides or glucose from the polysaccharide chain, respectively. Mutanases are produced by fungi, mainly Trichoderma, and also by several bacterial genera, such as Bacillus, Paenibacillus, Flavobacterium, Streptomyces, and Pseudomonas.

Previous studies indicate mutanases could be used to prevent caries (Asai et al. 1998; Inoue et al. 1990; Tsuchiya et al. 1998). However, their use in oral and dental care depends on the availability of their inducers. The mutanases reported so far, have been inducible in media containing streptococcal mutan. Unfortunately, this biopolymer is not available in bulk quantities due to the pathogenicity of its producers (cariogenic streptococci), the necessity to use complex, and expensive media (e.g., beef brain–heart infusion), multistage production process, low product yields (no more than 2 g l−1), and high structural heterogeneity. Substitution of mutan by more available inducers could facilitate commercial-scale mutanase production.

An alternative source of α-1,3-glucans is the fungal cell wall. We have shown that a cell wall preparation from L. sulphureus effectively induced mutanase in Trichoderma harzianum (Wiater et al. 2008) and, to our best knowledge, this was the first occasion when this material had been used for mutanase production. We have also described a newly isolated, mutan-degrading bacterium, Paenibacillus sp. MP-1, which synthesizes high amounts of extracellular mutanase when grown on bacterial mutan (Pleszczyńska et al. 2007). In this present study, L. sulphureus cell wall preparations, together with other fungal α-1,3-glucans, have been tested as inducers of Paenibacillus mutanase. The induced mutanase hydrolyzed streptococcal mutan also had biofilm-degrading activity.

Materials and methods

Microorganisms

Paenibacillus sp. MP-1 was isolated from soil, and was characterized as closely related to P. curdlanolyticus (Pleszczyńska et al. 2007). The fruiting bodies of Laetiporus sulphureus (Bul.: Fr.) Murrill were obtained from infected trees growing in Lublin area in Poland. A voucher specimen was deposited in the Department of Industrial Microbiology, Maria Curie-Skłodowska University, Poland. Aspergillus wentii and A. nidulans were taken from the culture collection of that department. Dried fruiting bodies of Lentinus edodes, Pleurotus djamor, P. ostreatus, P. citrinopileatus, P. eryngii, Agaricus blazei, Kuehneromyces mutabilis, Hericium erinaceum, and Piptoporus betulinus were a kind gift from Prof. M. Siwulski (Department of Vegetable Crops, Poznań University of Life Sciences, Poland).

Mutan preparation

Mutan was synthesized from sucrose by cell-free glucosyltransferases of Streptococcus sobrinus/downei CCUG 21020. A form of this glucan treated by dextranase (Sigma) was also prepared and used as a mutanase assay substrate (Pleszczyńska et al. 2008; Wiater et al. 2005). A 1H NMR analysis of the native and dextranase-treated glucans confirmed that they were mutans with 59.1 and 86.6 mol% α-1,3-linked glucosyl residues, respectively.

Isolation of cell wall material and an alkali-soluble glucan from fruiting bodies of L. sulphureus

Fresh fruiting bodies of L. sulphureus were lyophilized and milled and the dried fruiting bodies (DFB, 100 g) were suspended in water, heated at 117°C for 1 h, and washed with water by centrifugation (9600×g, 20 min). The material treated three times in this way was lyophilized and used as a water-insoluble cell-wall preparation (CWP, 70 g) (Wiater et al. 2008). For the isolation of the alkali-soluble α-glucan, the DFB fraction (100 g) was successively extracted with methanol, NaCl (9 g l−1), hot water, Na2CO3 (50 g l−1), and 1 M NaOH containing 0.2 g NaBrH4 l−1 for 24 h at room temperature. The final extract was neutralized with 1 M HCl under constant mixing (Kiho et al. 1994). The water-insoluble fraction was washed with water, collected by centrifugation, and lyophilized (purified α-1,3-glucan preparation, 56.9 g).

Preparation of mycelia of filamentous fungi

Aspergilluswentii, A. nidulans, A. niger CBS 554.65, and A. fumigatus CCM F-614 were cultured in Hasegawa medium (Hasegawa and Nordin 1969) on a rotary shaker at 150 rpm and 25°C for 6 days. Mycelia was harvested, washed with water, lyophilized, and milled.

Biofilm assay

Mutanase preparation was obtained by salting out with ammonium sulfate of cell-free filtrates obtained after culture of Paenibacillus MP-1 on a medium containing CWP. Biofilm degradation assays were performed by a modified method of Shimotsuura et al. (2008). Streptococcus sobrinus/downei CCUG 21020 (formerly S. mutans OMZ 176) was inoculated into glass tubes containing 3 ml BHI medium with 30 mg sucrose ml−1 and grown for 24 h at 37°C at an angle of 30°. The medium was then discarded and the formed biofilms were rinsed twice with 4 ml distilled water. Next, 4 ml of each mutanase solution (0.01; 0.1; 0.2; 1, and 2 U ml−1 in 50 mM phosphate buffer, pH 6.6) were added to the tubes. After 3 min at 37°C, the enzyme was replaced with 4 ml buffer, and incubation was continued for 6 h. In control trials, biofilms were incubated with the mutanase solutions for the whole 6 h. At the end of the experiments, residual biofilms were rinsed twice with 4 ml of water, homogenized, lyophilized, and weighed.

Analytical methods

To determine mutanase activity, a reaction mixture containing 0.5 ml of 0.2% (w/v) suspension of homogenized, dextranase-treated mutan in 0.05 M potassium phosphate buffer (pH 6.6) and 0.5 ml of appropriately diluted enzyme was incubated at 45°C. After 60 min, the insoluble mutan was removed by centrifugation (15,500×g for 10 min), and the released reducing sugars were estimated by the Samogyi-Nelson method using d-glucose as a standard. One unit of mutanase activity (U) was defined as the amount of the enzyme which produced 1 μmol reducing sugar equivalent per min under the defined conditions. The specific activity was expressed as mutanase units per mg protein. Protein was quantified using a protein assay kit (Bio-Rad) with bovine serum albumin as a standard. All the experiments and determinations were performed in triplicate, and the results were expressed as mean values. Standard deviations in the results were less than 5%.

Results

Effect of carbon sources on Paenibacillus sp. MP-1 mutanase production

Several α-1,3-glucan preparations derived from selected fungi were tested as potential Paenibacillus MP-1 mutanase inducers. The culture medium was supplemented with mutan as a control. In other trials, mutan was substituted by equivalent amounts of fungal α-glucan preparations. Table 1 shows that the α-1,3-glucan from the fruiting bodies of L. sulphureus induced high mutanase activity. Practical application of Laetiporus α-1,3-glucan, however, is conditioned by the cost and accessibility of its preparations. Among the three forms of fruiting body preparations tested as carbon sources (a) an extensively purified α-1,3-glucan (b) a cell-wall preparation (CWP), and (c) lyophilized and milled fruiting bodies (DFB), the first one induced the highest mutanase activity (Table 2) but was eliminated from further experiments due to its high price. DFB and CWP which are relatively inexpensive forms of Laetiporus α -1,3-glucan, gave similar levels of mutanase activity, but DFB contained water-soluble substances which made long-term storage difficult. The CWP fraction was storage-stable, and was therefore used as a mutanase inducer. CWP concentrations for maximum enzyme production (0.35 U ml−1) ranged from 1.5 to 2 g l−1.

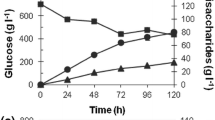

Mutan and biofilm degradation

Figure 1 shows that the cell-wall-induced mutanase preparation effectively degraded streptococcal mutan. The total amount of reducing sugars in 6-hour hydrolysates was 0.23 mg ml−1 (23%) and increased to 27% after 24 h. The CWP-induced mutanase solubilized 83% of mutan within 6 h. The enzyme also effectively degraded matrix α-1,3-glucans in biofilms preformed by S. mutans on a glass surface, even when the enzyme acted on them for 3 min only (Fig. 2) . The rate of biofilm degradation depended on the mutanase dose. Maximum dissociation of adherent biofilm (64%) occurred at the highest enzyme concentration (2 U ml−1).

Time course of mutan hydrolysis with Paenibacillus sp. mutanase induced by L. sulphureus cell wall. Mutan saccharification (□) and mutan solubilization (■). Native mutan (10 mg) and 1U of non-purified mutanase were added to 10 ml of 0.05 M phosphate buffer (pH 6.6) and incubated at 40°C together with 0.05% NaN3 (w/v) for 24 h. Samples were withdrawn periodically and analyzed for total reducing sugars. Solubilization of insoluble glucan was measured by turbidimetric analysis at 560 nm and the degree of solubilization was calculated. 100% of saccharification or solubilization corresponds to the total glucose residues of the initial amount of mutan (1.1 mg ml−1) or the turbidity of the blank without mutan (OD560 close to or equal to zero), respectively

Degradation of S. mutans biofilms by Paenibacillus MP-1 mutanase induced by L. sulphureus cell wall. 6-h action of mutanase (○), 3-min action of mutanase (■). The rate of biofilm degradation was calculated with the following equation: [1 – weight of mutanase-treated biofilm/weight of untreated biofilm] × 100%. One hundred percent biofilm degradation corresponds to complete removal of mutan from biofilm matrix (weight of mutanase-treated biofilm close to zero)

Discussion

Typically, mutanase synthesis is induced by α-1,3-glucan. The mutan produced by cariogenic streptococci is a commonly used and effective mutanase inducer, but has no practical application in biotechnology; larger-scale production of mutanase would require the use of more available and safer inducers derived from other sources. Such inducers can be found in cell walls of a large number of fungi.

Only a few substrates containing fungal α-1,3-glucan had been investigated previously for their ability to induce bacterial α-1,3-glucanases. Meyer and Phaff (1980) obtained up to 0.31 U glucanase ml−1 from Bacillus circulans WL-12 supplementing the media with whole cells of Schizosaccharomyces pombe or purified α-1,3-glucan from Aspergillus niger. Streptomyces KI-8 produced mutanase (0.16 U ml−1) when it was cultured on α-1,3-glucan isolated from dried fruiting bodies of Lentinus edodes (Imai et al. 1977). A cell-wall preparation of Schizophyllum commune was used as a mutanase inducer in B. circulans KA-304, but the enzyme activities were not reported (Mizuno et al. 1997; Yano et al. 2003, 2006). Importantly, none of those substrates were rich in α-1,3-glucan, and, in most cases, their preparation was expensive and time-consuming. Furthermore, the mentioned α-1,3-glucan-induced glucanases had not been considered in terms of their ability to hydrolyze dental-plaque mutan. Only Streptomyces KI-8 α-1,3-glucanase showed a weak ability to degrade this glucan (Imai et al. 1977). Between 9 and 10% hydrolysis was achieved for two mutans of S. mutans (glucan solubilization reached 38.0 and 42.0%) after 24 h. However, to our knowledge, similarly to the other mentioned mutanases, the S. mutanase has not been applied for the degradation of oral biofilms.

Laetiporus sulphureus is a valuable source of α-1,3-glucan for mutanase production. This has already been demonstrated for mutanase from T. harzianum (Wiater et al. 2008), but this α-glucan has never been used as an inducer of bacterial mutanases. L. sulphureus belongs to parasitic basidiomycota infecting hardwood trees, as a brown rot of the heartwood of living trees, and as a saprophyte on dead trees. It grows throughout much of the world, and produces very large edible shelf-shaped fruiting bodies of pink-orange color. Fruiting bodies of L. sulphureus can contain even up to 88% of α-1,3-glucan in the wall material (other fungi—up to 46%). The linear α-glucan predominantly consists of glucose (96%), which is mainly α-1,3-linked (Grün et al. 2003; Jelsma and Kreger 1978; Wiater et al. 2008). Fruiting bodies and cultured mycelium of Laetiporus are readily available on a large scale.

α-1,3-Glucan preparations from fruiting bodies of L.sulphureus are capable of inducing a satisfactory level of mutanase activity (0.35 U ml−1) in Paenibacillus sp. MP-1, which is higher than or comparable to the activities of this enzyme from other bacteria (Imai et al. 1977; Matsuda et al. 1997; Meyer and Phaff 1980). Furthermore, contrary to other fungal-α-1,3-glucan-induced glucanases, CWP-induced P. mutanase is suitable for application in dentistry. It not only effectively degrades pure S. mutans in a long-time reaction, but can also remove water-insoluble glucan from the polymer matrix of preformed Streptococcus biofilm, even if it is allowed to act on the biofilm for a very short time. To date, only Shimotsuura et al. (2008) have reported a similar efficacy of mutanase. They obtained an almost complete degradation of S. mutans ATCC 25175 biofilm after 3-min incubation with Paenibacillus sp. RM1 mutanase at 1.4 U ml−1.

In summary, the results of this study may have implications in dental caries prevention. The easily-available and inexpensive L. sulphureus cell-wall preparations can substitute streptococcal mutan in the production of high mutanase activity from Paenibacillus sp. MP-1. The obtained enzyme shows high hydrolytic activity towards mutan, quickly and effectively degrades bacterial biofilm. These characteristics suggest its potential application as an active agent of oral care compositions for controlling dental biofilm.

References

Asai Y, Odera M, Kikawa H, Shimotsuura I, Yokobori Y, Hirano M, Shibuya K (1998) Mutanase-containing oral compositions. US Patent No. 5,741,487

Grün CH, Hochstenbach F, Sietsma JH, Klis FM, Kamerling JP, Vliegenthart JFG (2003) Evidence for two conserved mechanisms of cell-wall α-glucan biosynthesis in fungi. In: Grün CH (ed) Structure and biosynthesis of fungal α-glucans. University of Utrecht, Utrecht, pp 116–132

Hasegawa S, Nordin JH (1969) Enzymes that hydrolyze fungal cell wall polysaccharides. I. Purification and properties of an endo-α-D-(1→3)-glucanase from Trichoderma viride. J Biol Chem 244:5460–5470

Imai K, Kobayashi M, Matsuda K (1977) Properties of an α-1, 3-glucanase from Streptomyces sp. KI-8. Agric Biol Chem 41:1889–1895

Inoue M, Yakushiji T, Mizuno J, Yamamoto Y, Tanii S (1990) Inhibition of dental plaque formation by mouthwash containing an endo-alpha-1,3 glucanase. Clin Prevent Dent 12:10–14

Jelsma J, Kreger DR (1978) Observations of the cell-wall compositions of the bracket fungi Laetiporus sulphureus and Piptoporus betulinus. Arch Microbiol 119:249–253

Kiho T, Yoshida I, Katsuragawa M, Sakushima M, Usui S, Ukai S (1994) Polysaccharides in fungi XXXIV. A polysaccharide from the fruiting bodies of Amanita muscaria and the antitumor activity of its carboxymethylated product. Biol Pharm Bull 17:1460–1462

Matsuda S, Kawanami Y, Takeda H, Ooi T, Kinoshita S (1997) Purification and properties of mutanase from Bacillus circulans. J Ferm Bioeng 83:593–595

Meyer MT, Phaff HJ (1980) Purification and properties of (1→3)-α-glucanases from Bacillus circulans WL-12. J Gen Microbiol 118:197–208

Mizuno K, Kimura O, Tachiki T (1996) Protoplast formation from Schizophyllum commune by a culture filtrate of Bacillus circulans KA-304 grown on a cell-wall preparation of S. commune as a carbon source. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem 61:852–857

Paes Leme AF, Koo H, Bellato CM, Bedi G, Cury JA (2006) The role of sucrose in cariogenic dental biofilm formation—new insight. J Dent Res 85:878–887

Pleszczyńska M, Marek-Kozaczuk M, Wiater A, Szczodrak J (2007) Paenibacillus strain MP-1: a new source of mutanase. Biotechnol Lett 29:755–759

Pleszczyńska M, Wiater A, Szczodrak J (2008) Methods for obtaining active mutanase preparations from Paenibacillus curdlanolyticus. Prep Biochem Biotechnol 38:389–396

Shimotsuura I, Kigawa H, Ohdera M, Kuramitsu HK, Nakashima S (2008) Biochemical and molecular characterization of a novel type of mutanase from Paenibacillus sp. strain RM1: identification of its mutan-binding domain, essential for degradation of Streptococcus mutans biofilms. Appl Environ Mirobiol 74:2759–2765

Tsuchiya R, Fuglsang CC, Johansen C, Aaslyng D (1998) Effect of recombinant mutanase and dextranase on plaque removal. J Dent Res 77:2713

Wiater A, Szczodrak J, Pleszczyńska M (2005) Optimization of conditions for the efficient production of mutan in streptococcal cultures and post-culture liquids. Acta Biol Hung 56:137–150

Wiater A, Szczodrak J, Pleszczyńska M (2008) Mutanase induction in Trichoderma harzianum by cell wall of Laetiporus sulphureus and its application for mutan removal from oral biofilms. J Microbiol Biotechnol 18:1335–1341

Yano S, Yamamoto S, Toge T, Wakayama M, Tachiki T (2003) Occurrence of a specific protein in Basidiomycete-lytic enzyme preparation produced by Bacillus circulans KA-304 inductively with a cell-wall preparation of Schizophyllum commune. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem 67:1976–1982

Yano S, Wakayama M, Tachiki T (2006) Cloning and expression of an α-1, 3-glucanase gene from Bacillus circulans KA-304: The enzyme participates in protoplast formation of Schizophyllum commune. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem 70:1754–1763

Acknowledgments

This work was financially supported from funds for science in the years 2008–2011 as the development project No 325/R/P01/2007/IT1.

Conflict of interest statement

None.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Purpose of work

To show that fungal α-1,3-glucans can replace streptococcal mutan in the production of mutanase from Paenibacillus sp. MP-1, which can be used as an active agent in oral care products.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Pleszczyńska, M., Wiater, A. & Szczodrak, J. Mutanase from Paenibacillus sp. MP-1 produced inductively by fungal α-1,3-glucan and its potential for the degradation of mutan and Streptococcus mutans biofilm. Biotechnol Lett 32, 1699–1704 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10529-010-0346-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10529-010-0346-1