Abstract

The genetic diversity of the Turkish native chicken breeds Denizli and Gerze was evaluated with 10 microsatellite markers. We genotyped a total of 125 individuals from five subpopulations. Among loci, the mean number of alleles was 7.5, expected heterozygosity (H e) was 0.665, PIC value was 0.610, and Wright’s fixation index was 0.301. H e was higher in the Denizli breed (0.656) than in the Gerze breed (0.475). The PIC values were 0.599 and 0.426 for Denizli and Gerze, respectively. A phylogenetic tree was constructed using genetic distance and the neighbor-joining method. Its topology reflects the general pattern of genetic differentiation among the Denizli and Gerze breeds. The present study suggests that Denizli and Gerze subpopulations have a rich genetic diversity. The information about Denizli and Gerze breeds estimated by microsatellite analysis may also be useful as an initial guide in defining objectives for designing future investigations of genetic variation and developing conservation strategies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Native chickens are known to be good foragers and efficient mothers, and they require minimal care to grow. They are, therefore, most suited for raising under village conditions. These birds do, however, need special attention with respect to their conservation and improvement. Turkish native chicken breeds exist as names in the literature, but there is no information on their characteristics, such as the extent of genetic diversity. Furthermore, native chicken breeds are becoming extinct because of their poor commercial performance. Consequently, there is a need to define existing chicken populations and to develop improvement and conservation programs so as to benefit people living in rural areas.

It can be assumed that local breeds contain the genes and alleles pertinent to their adaptation to particular environments and local breeding goals. Such local breeds are needed to maintain genetic resources permitting adaptation to unforeseen breeding requirements in the future and can serve as a source of research material (Romanov and Weigend 2001).

Düzgüneş (1990) claimed that the Denizli and Gerze breeds are two of the Turkish native chickens. These breeds are primarily located to the western (Denizli) and northern (Gerze) parts of Turkey. Denizli hens are reared for eggs and as a hobby, and Denizli cocks are famous for their long crowing (app. 15–16 s). Gerze chickens, reared in the province of Sinop in northern Turkey, are primarily reared for eggs and as a hobby. Additional reports on Denizli and Gerze phenotypes include feathering characteristics (Aksoy et al. 2002), adult body weight, egg number, reproduction performance (Özdoğan et al. 2007), and blood group alleles (Aksoy et al. 2000).

Recent advances in molecular technology have provided new opportunities to assess genetic variability at the DNA level. Microsatellites are tandem repeats of one to six bases. They are widely used since they are numerous, randomly distributed in the genome, and highly polymorphic, and they show codominant inheritance (Cheng and Crittenden 1994). A number of publications have revealed that microsatellite markers are useful in determining many descriptive statistics such as heterozygosity, genetic distance, number of effective alleles, and polymorphic information content among closely related populations. Relatively few publications have addressed the genetic diversity of local chickens (Wimmers et al. 2000; Zhang et al. 2002; Hillel et al. 2003; Kong et al. 2006; Shahbazi et al. 2007).

Microsatellite analysis is regarded as the most convenient tool in the determination of heterozygosity and genetic distance, and many microsatellite loci are available for use in chickens. For a more general view on the importance of the exotic populations as genetic resources, it would be interesting to look at genetic distance to other commercial strains. Furthermore, the presence of unique alleles or allelic combinations coding for specific (production) traits and characteristics related to adaptability is of interest. An example of this is the Indian Kadaknath breed as a source for the valuable dark meat genes (Wimmers et al. 2000). In addition, with the increased focus on genetic conservation, unique alleles may be of use in decisions to maintain such birds. These decisions will be important, especially if the alleles are associated with economically important traits (Emara et al. 2002).

Turkey has undertaken a national project (TAGEM-97/17/01/0003) to genetically improve indigenous native chickens. The Lalahan Livestock Central Animal Research Institute has operated a national program of genetic preservation of native chickens, titled “The conservation of Turkish native chickens, Denizli and Gerze,” since 1997. This project specifically aimed to identify, characterize, and protect the Denizli and Gerze breeds for quantitative traits. It has also tried to determine and maintain genetic diversity in these breeds. There is, however, no comprehensive published genetic description of current Turkish native chickens. According to the Turkish Ministry of Agricultural and Rural Affairs, there are two indigenous chickens, Denizli and Gerze, and these breeds are now in serious danger of extinction. The present analysis is of great importance because it is probably the first genetic study of Turkish native chicken biodiversity using microsatellite markers. The objective of this research was to determine genetic diversity within the breeds and to compare the Denizli and Gerze Turkish native chicken breeds. To achieve this goal, we individually genotyped 10 microsatellite loci in 125 chickens from five subpopulations.

Materials and Methods

Experimental Populations

Turkish native chicken subpopulations and the number of individuals used in this study are as follows: Denizli Cock Rearing Farm (DHUC, N = 25), Denizli Lalahan Livestock Central Animal Research Institute (DLHMAE, N = 25), Denizli Private Farms (DOI, N = 25), Gerze Lalahan Livestock Central Animal Research Institute (GLHMAE, N = 25), and Gerze Private Farms (GOI, N = 25). The DHUC, DLHMAE, and DOI subpopulations contain only the Denizli breed. The DLHMAE subpopulation was derived from the DHUC subpopulation for genetic conservation purposes in 1997, and they have been reared closely. The GLHMAE and GOI subpopulations contain only the Gerze breed. The GLMHAE was derived from the GOI subpopulation for genetic conservation in 1997, and they have the same genetic background. In total, 125 chickens from the five subpopulations were genotyped.

DNA Isolation

Blood samples were collected from the wing vein with syringes into a tube containing EDTA as an anticoagulating agent. DNA of individuals was isolated from 100 μl of blood in EDTA using a Wizard Genomic DNA Purification Kit (Promega).

Microsatellite Loci

Ten microsatellite primers (ADL0102, ADL0136, ADL0158, ADL0171, ADL0172, ADL0176, ADL0181, ADL0210, ADL0267, and ADL0268) have been recommended by the FAO/MoDAD (2004) advisory group and were provided by the Coordinators of the U.S. National Poultry Genome Research Program.

PCR Procedure

PCR reactions were carried out in a total volume of 25 μl containing 50–100 ng genomic DNA, 2.5 mM MgCl2, 200 μM dNTP, 0.5 U Taq Polymerase, 50 nM each primer (one of which was labeled with a fluorescent dye). The cycling conditions consisted of 5 min at 95°C followed by 30 cycles of 30 s at 94°C, 45 s at 50°C, and 90 s at 72°C, and a final extension step of 10 min at 72°C (Cheng et al. 1995). A mixture of 1 μl PCR product and 80% formamide was made, denatured by heating to 94°C for 5 min, and analyzed by an ABI Prism 310 sequencer (Applied Biosystems, USA). The size of each fragment was determined relative to the TAMRA 350 size standards (Applied Biosystems) using GeneScan.

Statistical Analysis

Based on microsatellite genotyping and allele frequencies, the number of alleles, allele size range (in base pairs), observed heterozygosity, Nei’s (1987) expected heterozygosity, and Wright’s (1978) fixation index were estimated using the computer software package PopGene version 1.31 (Yeh et al. 1997). Allele frequencies obtained from the microsatellite genotypes were used to calculate PIC (polymorphism information content) values (Botstein et al. 1980) using the computer software package Cervus 3.0 (Marshall et al. 1998; Kalinowski et al. 2007) in order to measure the degree of information obtained by a microsatellite. Based on microsatellite genotyping, Nei’s (1978) unbiased genetic distance between subpopulations was estimated. These results were used to construct phylogenetic trees by neighbor-joining cluster analysis with the appropriate options of computer software package PopGene version 1.31.

Results

Microsatellite Allele Distribution

All microsatellite primers gave PCR products that were polymorphic in the five subpopulations (Table 1). Allele size range differences between the alleles observed within the loci ranged from 18 bp (ADL0181) to 40 bp (ADL0171), with an average of 25.4 bp per locus. The number of alleles per locus varied from 3 (ADL0210) to 12 (ADL0136) alleles detected. The total number of alleles was 75 across all populations. The mean number of alleles across all microsatellite loci was 7.5 ± 0.76 (Table 1).

Across breeds, the mean number of alleles in Denizli was 6.1 ± 0.6, and in Gerze it was 5.0 ± 0.7 (Table 2).

Genetic Variability

The estimates of expected heterozygosity (H e) and PIC were obtained using the allele frequency data for each locus in each subpopulation and across breeds. Expected heterozygosities were quite high, ranging from 0.498 (ADL0181) to 0.852 (ADL0136), and the mean H e was 0.665 ± 0.04 among loci (Table 1). The estimates of H e at different loci between subpopulations showed a large variation. Among breeds given in Table 2, the mean H e was 0.656 ± 0.045 in Denizli and 0.475 ± 0.074 in Gerze. This result showed that genetic diversity is higher in the Denizli breed than in the Gerze breed.

The PIC among loci was highest for ADL0136 (0.830) and lowest for ADL0210 (0.381). Among breeds, the mean PIC value was 0.599 ± 0.049 in Denizli and 0.426 ± 0.068 in Gerze (Table 2).

Wright’s fixation index (F ıs) values among loci ranged from −0.017 (for ADL0210) to 0.540 (ADL0171). The mean F ıs for 10 microsatellite loci was 0.301 ± 0.05 (Table 1). The mean of observed heterozygosity (H o) was 0.508 ± 0.037 in the Denizli breed and 0.380 ± 0.065 in the Gerze breed (Table 2).

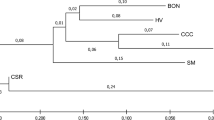

Genetic Distance and Phylogenetic Analysis

Using Nei’s (1978) unbiased genetic distance (Table 3) and the neighbor-joining method, a phylogenetic tree was constructed for the Denizli and Gerze subpopulations. The smallest genetic distance, between DLHMAE and DHUC, was quite low (0.0652). A similar result was obtained for the GLMHAE and GOI subpopulations, with a very low genetic distance (0.0783). The larger genetic distances (greater than 0.4193) were found between the Denizli and Gerze subpopulations. The neighbor-joining dendrogram in Fig. 1 was drawn using the genetic distances given in Table 3. The Denizli (DHUC, DLHMAE, and DOI) and Gerze (GLHMAE and GOI) breeds were clearly clustered as different groups according to their origin, supporting the reliability of this analysis.

Discussion

Microsatellite Allele Distribution

All microsatellite loci recommended by the FAO/MoDAD (2004) Advisory Group were extremely proficient at obtaining highly polymorphic PCR products within and between Turkish native chickens. They also demonstrated their utility as informative molecular markers in the Denizli and Gerze breeds. The mean number of alleles in this research for overall loci was 7.5 ± 0.76 (Table 1).

Compared with previous studies (Kong et al. 2006; Wimmers et al. 2000), the present research revealed the same microsatellite allele variation in Turkish native chickens. In particular, the mean number of alleles is similar to that of Korean native chickens (Kong et al. 2006). The number of alleles for ADL0158, ADL01171, ADL01176, ADL0210, and ADL0267 was higher than the number reported by Wimmers et al. (2000) in African, Asian, and South American local chickens.

The mean number of alleles for all loci was similar among the five subpopulations. Across breeds, the mean number of alleles in the Denizli and Gerze breeds was 6.1 ± 0.6 and 5.0 ± 0.7, respectively (Table 2). In chickens, the number of alleles at a single microsatellite locus in any single population has ranged from one (monomorphic) up to several (Emara et al. 2002; Cheng et al. 1995). For instance, Emara et al. (2002) examined 41 microsatellite markers in three commercial broiler pure lines and reported an average number of alleles per marker of 3.5, 2.8, and 3.1 for each of the lines. Hillel et al. (2003) reported that the mean number of alleles was 3.5 within 52 populations. Shahbazi et al. (2007) reported a mean number of alleles of 4.5 per locus in Iranian native chickens. Compared with the data obtained by Croojimans et al. (1996), who reported an average of 3.6 alleles per marker in broiler lines, and by Kaiser et al. (2000), who reported 2.8 and 2.9 alleles per marker in two broiler populations, we observed higher numbers of alleles (6.1 ± 0.6 and 5.0 ± 0.7) per primer in Turkish native chickens. These values are lower than those reported by Zhang et al. (2002), who estimated a mean of 9.32 alleles for the same primers in Chinese native chicken breeds.

Genetic Variability

Heterozygosity estimates within the populations were based on a set of markers showing substantial heterogeneity in the number of alleles detected and the polymorphic information content. The use of a mixture of highly variable and less variable microsatellites should reduce the danger of overestimating genetic variability, which might occur if only highly variable loci are used (Wimmers et al. 2000). For all loci, high H e was observed, and mean H e was 0.665 ± 0.04 among loci (Table 1). Among breeds in Table 2, the mean H e was 0.656 ± 0.045 in Denizli and 0.475 ± 0.074 in Gerze. This result showed that genetic diversity in the Denizli breed is higher than in the Gerze breed. This level of mean H e is quite similar to the value reported for Korean native chickens (0.630) (Kong et al. 2006). Hillel et al. (2003) reported that the average gene diversity within 52 populations across all 22 loci was 0.47. Romanov and Weigend (2001), using microsatellites with chickens, have reported heterozygosity of 0.60 or higher. A similar result (0.45–0.67) was reported by Wimmers et al. (2000) for African, Asian, and South American local chickens. The mean H e recorded in this research, however, is lower than that reported by Zhang et al. (2002) in Chinese native chickens and by Shahbazi et al. (2007) in Iranian native chickens. Very high heterozygosity values have also been described in Chinese and Iranian native chickens (0.63–0.86 and 0.62–0.74, respectively). The variation of expected heterozygosity may be adduced to differences in location, sample size, population structure, and sources of microsatellite markers.

The mean PIC was an ideal index to measure the polymorphism of allele fragments. According to Botstein et al. (1980), PIC > 0.50 indicates a highly informative locus, 0.50 > PIC > 0.25 indicates a reasonably informative locus, and 0.25 > PIC indicates a slightly informative locus. The mean PIC among loci was 0.610 ± 0.05, and almost all markers (except ADL0210) were highly informative in Turkish native chickens (Table 1). Reasonably informative PIC values for the ADL0158, ADL0171, ADL0176, ADL0210, and ADL0267 loci were reported in African, Asian, and South American local chickens (Wimmers et al. 2000). Among breeds, mean PIC values in the Denizli and Gerze breeds were 0.599 ± 0.049 and 0.426 ± 0.068, respectively (Table 2). Almost all loci (except ADL0102 and ADL0210) in the Denizli breed are highly informative, whereas 40% of the loci in the Gerze breed were reasonably informative. The ADL0158 and ADL0181 loci in the Gerze breed were slightly informative. The others were highly informative.

The mean F ıs for 10 microsatellite loci was 0.301 ± 0.05 (Table 1). The results at each single locus revealed that in all cases (except ADL 210) positive F ıs values were estimated. This means that there may be more heterozygotes than expected for ADL0210 in all five subpopulations (Table 2).

The mean H o was 0.508 ± 0.037 in the Denizli breed and 0.380 ± 0.065 in the Gerze breed (Table 2). The number of heterozygous genotypes was higher in the Denizli than in the Gerze breed. Thus, the Denizli breed is more variable than the Gerze breed. Therefore, the wide genetic diversity of the Denizli breed allows scientists and farmers to use it in future research and development of quality chicken breeds in Turkey. The high level of variability in the Denizli and Gerze breeds calls attention to the importance of conserving the Turkish native chicken gene pool.

Genetic Distance and Phylogenetic Analysis

The genetic distance (0.0652) between the DLHMAE and DHUC subpopulations was estimated to be quite low (Table 3), reflecting the fact that these subpopulations are not genetically isolated from each other. The same result can be seen for the GLMHAE and GOI subpopulations, with a very low genetic distance (0.0783). Larger genetic distances (greater than 0.4193) were found between the Denizli and Gerze subpopulations. This result is similar to that of Hillel et al. (2003), who found Nei’s mean genetic distance between a given population and all other 51 populations to be 0.44. Hillel et al. (2003) also emphasized that genetic distance measures based on gene frequencies were in good agreement with the genetic diversity of the breeds examined, indicating that these approaches fit the history of the domesticated chickens well.

The genetic differentiation found between the Denizli and Gerze breeds in the neighbor-joining dendrogram (Fig. 1) is confirmed by their breeding origin and evolution.

The present study demonstrates the usefulness of microsatellite primers as molecular markers to identify and compare the Denizli and Gerze subpopulations even with a limited number of loci and samples analyzed. The data also suggest that genetic diversities within and between the Denizli and Gerze breeds are being well preserved by conservation efforts. The information about the Denizli and Gerze breeds estimated by microsatellite analysis may also be useful as an initial guide in defining objectives for designing future investigations of genetic variation and developing conservation strategies.

References

Aksoy FT, Ertuğrul O, Atasoy F, Gürler S, Erdoğan M (2000) A study on blood group alleles of Denizli Fowl. Turk J Vet Anim Sci 24(5):431–434

Aksoy FT, Atasoy F, Onbaşılar EE, Apaydın S (2002) The possibilities of sexing day-old Denizli fowl by means of feathering characteristics. Turk J Vet Anim Sci 26(3):567–575

Bolstein D, White RL, Skolnik M, Davis RW (1980) Construction of a genetic linkage map in man using restriction fragment length polymorphisms. Am J Hum Genet 32:314–331

Cheng HH, Crittenden LB (1994) Microsatellite markers for genetic mapping in the chicken. Poult Sci 73:539–546

Cheng HH, Levin I, Vallegjo RL, Khatip H, Dodgson JB, Crittenden LB, Hillel J (1995) Developing of a genetic map of the chicken with markers of high utility. Poult Sci 74:1855–1874

Croojimans RPMA, Groen AF, Van Kampen AJA, Van der Beek S, Van der Poel JJ, Groenen MAM (1996) Microsatellite polymorphism in commercial broiler and layer lines using pooled blood samples. Poult Sci 74:1855–1874

Düzgüneş O (1990) Hayvancılıkta Genetik Kaynaklar. Türkiye’nin Biyolojik Zenginlikleri. Türkiye Çevre Sorunları Vakfı Yayınları

Emara MG, Kim H, Zhu J, Lapierre RR, Lakshmanan N, Lillehoj HS (2002) Genetic diversity at the major histocompatibility complex (B) and microsatellite loci in three commercial broiler pure lines. Poult Sci 81:1609–1617

FAO/MoDAD (2004) Secondary Guidelines. Measurement of Domestic Animal Diversity (MoDAD): Recommended Microsatellite Markers. http://fao.org/dad-is

Hillel J, Groenen MAM, Boichard MT, Korol AB, Davıd L, Kirzhner VM, Burke T, Barre-Dirie A, Crooijmans RPMA, Elo K, Feldman M, Freidlin PJ, Mäki-Tanila A, Oortwijn M, Thomson P, Vignal A, Wimmers K, Weigend S (2003) Biodiversity of 52 chicken populations assessed by microsatellite typing of DNA pools. Genet Sel Evol 35:533–557

Kaiser MG, Yonash N, Cahaner A, Lamont SJ (2000) Microsatellite polymorphism between and within broiler populations. Poult Sci 79:626–628

Kalinowski ST, Taper ML, Marshall TC (2007) Revising how the computer program CERVUS accommodates genotyping error increases success in paternity assignment. Mol Ecol 16:1099–1006

Kong HS, Oh JD, Lee JH, Jo KJ, Sang BD, Choi CH, Kim SD, Lee SJ, Yeon SH, Jeon GJ, Lee HK (2006) Genetic variation and relationships of Korean native chickens and foreign breeds using 15 microsatellite markers. Asian Aust J Anim Sci 19(11):1546–1550

Marshall TC, Slate J, Kruuk LEB, Pemberton JM (1998) Statistical confidence for likelihood-based paternity inference in natural populations. Mol Ecol 7:639–655

Nei M (1978) Estimation of average heterozygosity and genetic distance from a small number of individuals. Genetics 89:583–590

Nei M (1987) Molecular evolutionary genetics. Columbia University Press, NY

Özdoğan N, Gürcan İS, Bilgen A (2007) Egg weight and egg weight repeatability of Denizli and Gerze local hen breeds. J Lalahan Livestock Res Inst 47(1):21–28

Romanov MN, Weigend S (2001) Analysis of genetic relationship between various populations of domestic and jungle fowl using microsatellite markers. Poult Sci 80:1057–1063

Shahbazi S, Mirhosseini SZ, Romanov MN (2007) Genetic diversity in five Iranian native chicken populations estimated by microsatellite markers. Biochem Genet 45(1/2):63–75

Wimmers K, Ponsuksili S, Hardge T, Valle-Zarate A, Mathur PK, Horst P (2000) Genetic distinctness of African, Asian and South American local Chickens. Anim Gen 31:159–165

Wright S (1978) Variability Within and Among Natural Populations, vol 4. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Yeh FC, Yang RC, Boyle TBJ, Ye ZH, Mao JX (1997) PopGene, the user-friendly shareware for population genetic analysis. Molecular Biology and Biotechnology Centre, University of Alberta, Canada. http://www.ualberta.ca/~fyeh

Zhang X, Leung FC, Chan DKO, Yang G, Wu C (2002) Genetic diversity of Chinese native chicken breeds based on protein polymorphism, randomly amplified polymorphic DNA, and microsatellite polymorphism. Poult Sci 81:1463–1472

Acknowledgments

This work was performed by Muhammet Kaya in partial fulfillment of the Ph.D. degree in Biometry and Genetics at University of Ankara, Turkey. The authors would like to thank Dr. H. H. Cheng, from USDA-ADOL, for supplying microsatellite markers, reviewing the early manuscript, and valuable comments. Dr. Cheng also allowed Muhammet Kaya to work in his lab. We are also grateful to Dr. Neval Özdoğan (Lalahan Livestock Central Animal Research Institute), Agr. Eng. Mustafa Ünal (Denizli Cock Rearing Farm), İsmail Fışkın (Private Farm, Denizli), and Halil Karadeniz (Private Farm, Sinop) for providing the collection of blood samples. This project was supported by a grant, TOVAG-105O446, from The Scientific and Technological Research Council of Turkey (Project coordinator Dr. M. A. Yıldız). We are also grateful to anonymous reviewers for their comments on an earlier version of the manuscript.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Kaya, M., Yıldız, M.A. Genetic Diversity Among Turkish Native Chickens, Denizli and Gerze, Estimated by Microsatellite Markers. Biochem Genet 46, 480–491 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10528-008-9164-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10528-008-9164-8