Abstract

This study used a theoretically-derived set of items of the Achenbach System of Empirically Based Assessment to develop the Achenbach Self-Control Scale (ASCS) for 7–16 year olds. Using a large dataset of over 20,000 children, who are enrolled in the Netherlands Twin Register, we demonstrated the psychometric properties of the ASCS for parent-, self- and teacher-report by examining internal and criterion validity, and inter-rater and test–retest reliability. We found associations between the ASCS and measures of well-being, educational achievement, and substance use. Next, we applied the classical twin design to estimate the genetic and environmental contributions to self-control. Genetic influences accounted for 64–75% of the variance in self-control based on parent- and teacher-report (age 7–12), and for 47–49% of the variance in self-control based on self-report (age 12–16), with the remaining variance accounted by non-shared environmental influences. In conclusion, we developed a validated and accessible self-control scale, and show that genetic influences explain a majority of the individual differences in self-control across youth aged 7–16 years.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Self-control—the capacity to alter unwanted impulses and behavior, in order to bring them into agreement with internal and external standards—is consistently associated with thriving mental, social, and physical well-being among children and adults (de Ridder et al. 2012; Moffitt et al. 2011; Tangney et al. 2004). A validated scale allowing for longitudinal assessments of self-control from childhood to adolescence is needed to advance investigations of its development. A self-control scale suitable for children and adolescents should take several issues into account. First, in studying children’s development, it is important that the scale is reliable across different ages. Second, we should take into account that children develop across contexts. The school context is different than the home context, with different raters providing different information (Bartels et al. 2007), and thus afford access to different behavior and insights that may be diagnostic for self-control. It is therefore important that a scale is reliable across different informants because, on the one hand, different informants afford a richer assessment of self-control, and, on the other hand, inter-rater reliability ensures robust assessment of self-control when only one rater is available. In the present study, we propose a scale that takes these issues into account.

Why is self-control important in children? Self-control entails the strengthening of a desired action (e.g., concentrating on an assignment, finishing homework, paying attention during class), and the capacity to suppress an undesired impulse (e.g., suppress temper tantrums, avoid breaking rules at home, inhibit irritable behavior in the classroom; Tangney et al. 2004). Self-control allows children to regulate their emotions, thoughts, or behavior, and underlies many skills and competences necessary to become healthy and well-adjusted adults (de Ridder et al. 2012; Finkenauer et al. 2005). For example, low self-control in early childhood is associated with less happiness, less compliance, poorer educational achievement, and with more oppositional and deviant behaviors, such as substance use in later life (Duckworth et al. 2014; Finkenauer et al. 2005; Moffitt et al. 2011).

So far, a wide variety of questionnaires have been used to assess self-control. Some researchers use self-contained questionnaires, others select specific items of existing questionnaires. For example, Moffitt et al. (2011) assessed self-control by composing a scale of items selected from different scales, such as their Dunedin Behavioral Ratings. Their assessment included items such as “emotionally labile”, “brief attention to tasks”, and “impulsive”. Likewise, Hay and Forrest (2006) and Turner and Piquero (2002) used a scale drawing items from the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) (Achenbach and Rescorla 2001) in combination with items of other child behavior scales such as the Rutter Behavior Scale (Hogg et al. 1997) including items such as “temper tantrums”, “has difficulty completing activities”, and “cannot wait for things”. While there is a clear overlap in items included in these aforementioned studies, these composites of items have not yet resulted in the validation of an internationally accessible and applicable self-control scale, a crucial step to improve our understanding of self-control among children in the future. In this research, we therefore investigate whether a theoretically-derived set of items, similar to the aforementioned items, of the Achenbach System of Empirically Based Assessment (ASEBA, http://www.aseba.com) can be used to assess self-control during childhood. The ASEBA is a worldwide, frequently used, multi-informant tool applied in both scientific research and clinical practice (Achenbach and Rescorla 2001; Achenbach et al. 2002). Validating a self-control scale based on such items could have vast implications. There are multiple large population based registers (e.g. NTR, Tchad, CATSS, Generation R, TRAILS) with longitudinal ASEBA data readily available (Anckarsäter et al. 2011; Lichtenstein et al. 2007; Ormel et al. 2012; Jaddoe et al. 2012). A validated ASEBA self-control scale (ASCS) allows to calculate a score for self-control in retrospect. This richness of available longitudinal data is unique, and would be difficult to become available if self-control were to be assessed from now onwards. Additionally, the ASEBA questionnaires have been translated in over 100 languages facilitating prospective cross-cultural studies. This offers novel and exciting opportunities to examine theoretical suggestions regarding the development of self-control.

The widely used ASEBA includes the CBCL, the Youth Self-Report (YSR), and Teacher’s Report Form (TRF), which were tailored for parents, children, and teachers, respectively (Achenbach and Rescorla 2001; Achenbach et al. 2002). The ASEBA questionnaires were developed to assess child maladaptive functioning, including syndrome scales such as anxiousness, depression, somatic problems and later also applied to assess dimensions of Autism and obsessive–compulsive disorder (Achenbach and Rescorla 2001; Achenbach et al. 2002; So et al. 2013; Nelson et al. 2001). They measure comparable constructs across ages with similar item content, allowing us to select items that meet the theoretical conceptualization of self-control and that overlap in item content with existing self-control scales (Moffitt et al. 2011; Tangney et al. 2004). We selected 8 items, similar in content across informants. The current study examines the psychometric properties of this 8-item scale. Depending on the informant, we call this scale the ASCS parent-report, ASCS self-report, or the ASCS teacher-report. We refer to these questionnaires collectively as the ASEBA Self-Control Scale or ASCS.

As a first step in examining the psychometric characteristics of the ASCS, we established their internal consistency and examined its dimensionality. In the literature on self-control, the dimensionality has been subject to discussion, some arguing that self-control is a unidimensional construct (Piquero et al. 2000; Tangney et al. 2004), while others suggest that it is multi-dimensional (Duckworth and Steinberg 2015; Maloney et al. 2012; Williams et al. 2007). In addition, we tested for criterion validity of the ASCS. Next, we examined associations between the ASCS and several relevant outcomes including well-being, educational achievement (i.e., school results in math, language, education level in high-school and classroom compliance, evaluated individually), and substance use (i.e., alcohol use, drunk prevalence, smoking, evaluated individually). (Duckworth et al. 2014; Finkenauer et al. 2005; Moffitt et al. 2011). We investigated the reliability of the ASCS by testing their test–retest reliability and inter-rater reliability. A number of studies investigate the stability of self-control over time. Some find evidence supporting stability (Beaver et al. 2013), while others find evidence on malleability (Burt et al. 2014; Hay and Forrest 2006; Turner and Piquero 2002). Although increases with time and age (maturation) have been found (Casey 2015), longitudinal studies have reported substantial stability of self-control (Hennecke et al. 2014). In line with these results, we expected that self-control will predict his/her own self-control in the future to a certain extent. Specifically, we expected that a child’s level of self-control, as assessed by the ASCS at age 7, predicts his/her levels of self-control at later ages. Furthermore, we expected the mother-, father-, self- and teacher-reports to be significantly correlated, indicating agreement between informants, thus addressing the ability of the ASCS to appropriately measure self-control across contexts and informants.

Next, we looked at the genetic and environmental sources of individual differences in self-control assessed with the ASCS and estimated the heritability as a function of age, informant, and sex using the classical twin design (Boomsma et al. 2002). Previous twin studies demonstrate that self-control “runs in families” (Bridgett et al. 2015). Several small-scale studies using adolescent twin data from Add Health (http://www.cpc.unc.edu/projects/addhealth) examined the genetic and environmental contributions to the variance in self-control. These studies showed heritability estimates between 44 and 64% for adolescent self-reported self-control, with the remaining variance accounted for by non-shared environmental factors, and no sex differences (Beaver et al. 2008, 2009; Boisvert et al. 2013). These results are largely consistent with more recent adolescent twin studies, such as the study by Anokhin et al. (2011), which reported a heritability estimate of 51% for self-control in 14-year-olds, and a study by Li et al. (2014), which reported a heritability estimate of 58% for self-control in 15-year-olds. In both studies the remaining variance was is accounted for by non-shared environmental factors. Studies using parent-reports consistently show stronger genetic influences, with most heritability estimates ranging between 74 and 79% (Lemery-Chalfant et al. 2008; Li et al. 2014), and one estimate of 95% (Beaver et al. 2013). Thus far, however, twin studies on self-control included relatively small samples (ranging between 372 and 825 twin pairs), few tested sex differences, and none included informantion from father- or teacher-reports. This study adds to this line of research by analyzing data from a large group of same-sex and opposite sex twin pairs, collected by the The Netherlands Twin Register (NTR), providing heritability estimates for mother-, father-, teacher- and self-report of self-control, from age 7 to 16. We also tested sex differences applying scalar and non-scalar sex limitaton models.

Methods

Sample and procedure

The NTR was initiated in 1987 in the Netherlands, and follows twins from childhood to adulthood (for more details see van Beijsterveldt et al. 2013). The present study includes measures of the ASEBA-CBCL/ASEBA-TRF based on mother-, father- and teacher-report of children assessed at aged 7, aged 10 and aged 12, and measures of the ASEBA-YSR based on self-reports in children aged 12, aged 14 and aged 16. Accordingly, we assessed the reliability and validity of the ASCS based on mother-, father- and teacher-report of children aged 7, aged 10 and aged 12, and measures of self-control based on self-reports in children aged 12, aged 14 and aged 16 (the scales are consistent across ASEBA measures). The current study includes data from 24,704 7-year-olds (50.3% girls), 19,589 9/10-year-olds (50.7% girls), 16,436 12-year-olds (50.9% girls), with 1704 self-reports for 12-year olds (50.8% girls), 10,020 14-year-olds (57.6% girls) and 7566 16-year-olds (59.9% girls). Participants with a disease or handicap that interfered severely with daily functioning were excluded (N = 500). For same sex twin pairs, zygosity was based on DNA polymorphisms (N = 1578) or blood markers (N = 240). For the remaining same-sex twin pairs, zygosity was determined using parent-reported items on resemblance in appearance and confusion of the twins. In approximately 93% of the cases, zygosity was correctly classified by these items (Rietveld et al. 2000). For the main analyses, we included all teacher reports, with slightly more than half of the twins sharing the same teacher (age 7, 54%; age 10, 53%; age 12, 57% of the twins were rated by the same teacher).

Measures

ASEBA

The ASEBA assessment consists of standardized questionnaires, which are completed by parents (CBCL), children themselves (YSR), and/or teachers (TRF). These questionnaires are used to rate a child’s competencies and problems in the past 6 months (for parent- and self-report), or in the past 2 months (for teacher-report). The response format of the items is a 3-point scale, with response options not true (coded 0), somewhat or sometimes true (coded 1), and very true or often true (coded 2). The CBCL and TRF consist of 113 items and the YSR of 112. Subsets of items are summed to create syndrome scales such as social problems, anxious depressed, and somatic complaints (Achenbach and Rescorla 2001).

ASCS

The ASCS is intended to measure self-control as defined by person’s ability to control his or her impulses, alter his or her emotions and thoughts, and to interrupt undesired behavioral tendencies and refrain from acting on them (Muraven and Baumeister 2000). To develop the ASCS, we followed a systematic scale development procedure for item selection. In this procedure, two subject matter experts independently assessed the relevance of each item of the ASEBA to the theoretical conceptualization of self-control (Muraven and Baumeister 2000). A third reviewer independently screened all ASEBA items selecting those corresponding to items used in earlier self-control studies. To resolve disagreement, in-depth discussion followed based the theoretical literature (Muraven and Baumeister 2000; de Ridder et al. 2012) and earlier studies including separate items to construct a self-control scale (e.g., in line with items selected by Cecil et al. 2012; Moffitt et al. 2011; Hay and Forrest 2006; Turner and Piquero 2002). As a result, 8 items were selected for the ASCS (see Table 1), with 4 items of the attention problem scale (item 4, 8, 41, 78), 4 items of the aggressive behaviour scale (item 86, 87, 95), and 1 item of the rule breaking behaviour scale (item 28).

We calculated the scale score given three or fewer missing item responses (Achenbach and Rescorla 2001). In the case of one to three missing item responses, we used the person-based weighted score. Cases with more than 3 items missing were excluded (2%), not expecting to influence variables of interest considering their low prevalence. Conducting our analyses in the subsample of participants without any missing values yielded similar results. Originally, the ASEBA was set up so that higher sum scores reflect higher frequency of child problems. Extending this approach to the ASCS, higher sum scores on the ASCS correspond to lower overall levels of self-control. This is in line with earlier studies on self-control (Moffitt et al. 2011).

Well-being

Well-being was assessed using the Cantril ladder (Cantril 1965). Parents (age 7, 9/10, 12) and children (14, 16) rated well-being on a ten-step ‘ladder’, with the bottom ‘step’ of the ladder representing the worst possible life and the top ‘step’ indicating the best possible life. Teachers rated well-being of 7, 9/10, and 12-year old children on a 5-point scale, with response options ranging from always or almost always unhappy (coded 1), more often unhappy than happy (coded 2), equally often happy as unhappy (coded 3), more often happy than unhappy (coded 4), almost always happy (coded 5).

Conners’ Parenting Rating Scale/Teacher Rating Scale—Revised

This widely used instrument assesses the severity of behavior problems of children in the past month (Conners et al. 1998a, b). The short version consists of 27 items for parent-report and 28 items for teacher-report (reported for age 7, 9/10, 12). Items are rated on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 0 = not true at all (never, rarely), 1 = a little bit true (so now and then), 2 = quite true (often, regularly), 3 = very much true (very often), where higher scores indicate more severe symptoms. Cronbach’s alphas were in line with the Conner’s manual, reporting Cronbach’s alphas between 0.83 and 0.85 for oppositional behavior, Cronbach’s alphas between 0.78 and 0.90 for inattention, and Cronbach’s alphas between 0.78 and 0.87 for hyperactivity (Conners et al. 1998a, b).

Educational achievement

Educational achievement was assessed through school results in math, language, learning problems, behaviour in class and education level in high school, evaluated separately. Parents rated children’s math and language achievement (on a 5-point scale, higher scores reflecting higher grades: 1 = fail, 2 = weak, 3 = pass, 4 = good, 5 = excellent), and learning problems (“did your child ever have learning problems?”, on a two-point scale, 1 = no, 2 = yes). Teachers rated compliance and task orientation of the child (“in comparison to the average student in your class, how compliant is he/she?”, “in comparison to the average student in your class, how task orientated is he/she”, 7-point scale, 1 = much less, 2 = less, 3 = a little bit less, 4 = average, 5 = little bit more, 6 = more, 7 = much more). Adolescents (aged 14, 16) rated their level of education. The Dutch school system divides education level according to three levels: VMBO (preparing students for vocational training), HAVO (preparing students to study at universities of applied sciences) and VWO (preparing students for university), also referred to as lower level (coded as 1), middle level (coded as 2) and higher level education (coded as 3), respectively.

Substance use

Adolescents (aged 14, 16) were asked how often they smoked (1 = never, 2 = I quit smoking, 3 = I smoke once a week, 4 = I smoke multiple times per week 5 = I smoke multiple times per day), their amount of alcohol intake per day in the weekend (1 = less than 1 glass, 2 = 1–2 glasses, 3 = 3–5 glasses, 4 = 6–10 glasses, 5 = 11–16 glasses, 6 = 17–20 glasses, 6 = 17–20 glasses, 7 = more than 20 glasses), and whether they had ever been drunk (0 = never, 1 = 1–2 times, 2 = 3–4 times, 3 = 5–6 times, 4 = 7–8 times, 5 = 9–10 times, 6 = 11–19 times, 7 = 20–39 times, 8 = more frequent).

Strategy of analyses

In order to examine psychometric properties of the ASCS, we tested internal consistency, dimensionality, criterion validity, inter-rater reliability, test–retest reliability, and heritability estimates. We used SPSS 21 (IBM Corp. 2012) and Mplus version 7 (Muthén and Muthén 2012) and conducted the analyses separately in children aged 7, 9/10, 12, 14, and 16, and separately for mother-, father-, self- and teacher-report. To correct for the dependency of the observations due to clustering in families, a sandwich estimator was used with weighted least squares with mean variance adjusted (WLSMV) as the estimator (Rebollo et al. 2012).

We investigated internal consistency by calculating Cronbach’s alphas. The dimensionality was examined by fitting a Multimethod-Single trait confirmatory factor model (CFA) (Campbell and Fiske 1959). This allowed us to establish whether the items measure a single factor (the single “trait” self-control) while taking into account the fact that the items are taken from different subscales within the ASEBA. In this manner, we can test the dimensionality of a model with one psychometric factor and multiple residual factors. Goodness of fit was evaluated using the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA), the Comparative Fit Index (CFI), and the Tucker Lewis Index (TLI). We adopted the rules of thumb that the RMSEA should be between 0.05 and 0.08 or lower (adequate fit in terms of error of approximation), and the TLI and CFI should be 0.95 or larger (Hu and Bentler 1999).

We examined criterion validity by calculating cross-sectional and longitudinal correlations between ASCS and the variables mentioned above concerning adaptive behaviors (i.e., well-being, educational achievement and substance use). Additionally, we investigated inter-rater reliability by examining the correlations between the ASCS parent-, self- and teacher-report. We investigated test–retest reliability by investigating correlations between ASCS scores over time.

Next, we estimated the heritability of self-control in a classical twin design in Mplus version’, 7 (Muthén and Muthén 2012). This design is built on the premise that differences in the resemblance between monozygotic twins (sharing approximately 100% of their DNA) and dizygotic twins (sharing 50% of their segregating genes on average) can be used to parse phenotypic trait variance into environmental and genetic components (Boomsma et al. 2002). As such, this model can be applied to estimate additive genetic (A, additive effects of alleles at multiple loci), non-additive or dominance genetic (D), common environment (C, the part of the variance that is shared by members of family), and non-shared environment (E, the part of the total variance that is unique to a certain individual) effects. We used raw-data genetic structural equation modelling with maximum likelihood estimation to perform univariate model fitting analyses to estimate the contributions of A, D or C, and E.

We first fitted a saturated model to estimate the twin correlations with their 95% confidence intervals. Based on these twin correlations an ACE or an ADE model with parameters allowed to differ between boys and girls was fitted to the data. Nested submodels were compared by hierarchic χ2 tests. The χ2 statistic was computed by subtracting—2LL (log-likelihood) for the full model from that for a reduced model (v2 = − 2LL1 − (− 2LL0)). Given that the reduced model is correct, this statistic is χ2 distributed with degrees of freedom (df) equal to the difference in the number of parameters estimated in the two models (Δdf = df1 − df0). In addition to the χ2 test statistic, Akaike’s Information Criterion (AIC = v2 − 2df) was computed to compare non-nested models. A lower AIC indicates a better the fit of the model to the observed data. Quantitative sex differences were tested by constraining the A, C/D, and E parameters to be equal across sex (Neale et al. 2006). Based on the twin correlations, we see little support for qualitative sex differences, which were therefore not modelled. When sex differences appeared to be significant, a scalar-sex limitation model was tested. In this model, a difference in total variance between boys and girls is allowed, but the relative contributions of genetic and environmental influences are equal across gender (Neale et al. 2006). In order to test the significance of A, C/D factors, we fitted models without the parameter with confidence intervals including zero.

Results

Internal consistency

Descriptive statistics of the ASCS are presented in Table 2. Cronbach’s alpha coefficients suggested adequate internal consistency, with coefficients ranging between 0.81 and 0.83 for ASCS parent- and teacher-reports, between 0.70 and 0.73 for ASCS self-reports.

Dimensionality

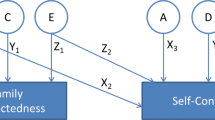

The ASCS consists of 8 items, with items derived from the attention problem scale (4 out of 10), aggressive behavior scale (3 out of 18), and rule-breaking behavior scale (1 out of 17). We specified a CFA with one psychometric (trait, denoted SC) common factor representing self-control. In addition, we included one residual factor to account for the fact that the 4 items were taken from the attention problem scale (R1att) and a second residual factor (R2agg) to account for the fact that three items were taken from the aggressive behavior scale (see Fig. S1, Supplemental Material). Statistically, this model showed good model fit for parent- and teacher-reports across all ages (see Tables S2 and S3, Supplemental Material), supporting the psychometric unidimensionality of the scale. For self-reports among adolescents aged 12–16 years, a correlation was added between the residuals of item 8 and item 78 (“can’t concentrate/can’t pay attention for long”, “inattentive, easily distracted”), because these items correlated highly. Given this addition, the model fitted well (see Tables S2 and S3, Supplemental Material). The high correlation between these items suggests that children might have more difficulties making a distinction between the subtle meaning of these 2 items than adults, making children more likely to rate them more similarly (see Table S3, Supplemental Material).

Criterion validity

Consistent with the literature (e.g., Moffitt et al. 2011), cross-sectional associations between the ASCS and several relevant outcomes, such as well-being and educational achievement, were significant in the predicted directions (see Table 3). For example, low self-control at age 7 based on mother-report was significantly correlated with mother-rated Conners’ oppositional behavior (.67), more learning problems (.28), and lower well-being (− .36). Similarly, low self-control at age 7 based on teacher-report was significantly correlated with teacher-rated Conners’ oppositional behavior (.58), and lower well-being (− .35). It also correlated negatively with compliance (− .55), and task orientation in class (− .65), two measures that were unique to teacher-reports. These results replicated in cross-sectional correlations across ages and informants (see Table 3 for details, and Table S4 for the descriptives of measures included in tests of criterion validity).

In addition to the cross-sectional analyses, self-control at age 7 was significantly correlated with constructs to which it should theoretically be related to at age 12 (see Table S4, Supplemental Material) and age 16 (see Table 4). For example, teacher-reported low self-control at age 7 was negatively correlated with self-reported education level at age 16 (− 0.24). Mother-, father-, and teacher-reported low self-control at age 7 were positively and significantly correlated with self-reported smoking behavior at age 16, but were not significantly correlated with self-reported alcohol intake at age 16. Self-reported low self-control at age 14 was significantly correlated with both self-reported smoking and alcohol intake at age 16. See Table S6, Supplemental Material, for descriptives of measures included in criterion validity tests.

Test–Retest Reliability and Inter-rater Reliability

Inter-rater reliability of the ASCS was assessed by correlating ASCS measures over raters and time (see Table 5). Results showed significant cross-sectional correlations between the informants, with (a) significant and strong correlations between father- and mother-reports (.66–.67), (b) significant and moderate correlations between parent- and child-reports (.40–.44), (c) significant, but lower correlations between teacher- and self-reports (.29), and (d) significant and moderate correlations between teacher- and parent-reports (.32–.40).

Longitudinal correlations of the ASCS scales across informants (intervals of 3–5 years) showed similar results, with (a) significant and moderate/strong correlations between father- and mother-reports (.45–.67), (b) significant and small/moderate correlations between parent- and child-reports (.16–.38), (c) significant and small correlations between teacher- and self-reports (.08–.25), and (d) significant and small/moderate correlations between teacher- and parent-reports (.23–.35). These findings, higher correlations between mother and father but low to moderate correlation between parent and child, parallel the cross-informant correlations reported by Achenbach et al. (2002), and earlier cross-informant studies on self-control (Duckworth and Kern 2011), confirming the inter-rater reliability of the ASCS.

To examine test–retest reliability, we investigated correlations between self-control scores measured across time within raters, with time intervals of 3–5 years (see Table 5). The results showed (a) significant and strong correlations between mother-reports from age 7–12 (.57–.67) and significant and strong correlations between father-reports from age 7–12 (.52–.65), (b) significant and moderate/strong correlations between teacher-reports from age 7–12 (.43–.54) and, (c) significant and moderate/strong correlations between self-reports from age 12–16 (.35–.55). These results are consistent with longitudinal correlations of earlier studies on self-control (e.g., Turner and Piquero 2002).

Twin data modeling

Within-twin pair correlations of each zygosity group (MZM, DZM, MZF, DZF, and DZ opposite-sex) were inspected for initial exploration of the possible contribution of genetic and environmental factors (correlations are shown in Table 6). MZ correlations were high for all informants, with the size of the correlations being relatively stable for both males and females by parent-, teacher- and self-reports. These were approximately .70–.75 for mother-report, .70–.78 for father-report, .61–.67 for teacher-report, and .40–.57 for self-report. This stability suggests that parent-, teacher- and self-report continue to report self-control in a fairly reliable way. MZ correlations were more than twice the DZ correlations at almost all ages and all informants, except for father report at ages 7, 10, and 12 and self-reports at age 12. Thus, one would expect genetic dominance or sibling interaction to be important for mother, teacher and self-reports. We observed no statistically significant zygosity effect on the variances in our data therewith suggesting the presence of D, rather than presence of a sibling interaction effect (Eaves 1976; Rietveld et al. 2003).

Subsequently, we fitted a series of models that tested for relative contribution of additive genetic (A), dominant genetic (D) or common environment (C), and unique environmental (E) influences. First, we fitted ACE and ADE models separately allowing parameters to be estimated freely across sex. Based on the lowest AIC value, we selected the best fitting model, that is an ACE or an ADE model. Second, to assess sex differences we fitted a model constraining parameters to be equal across sex. Third, when sex differences appeared, a scalar sex-limitation model was tested, allowing total variance to differ between boys and girls. Fourth, if confidence intervals of the estimated parameters included zero, we refitted the model dropping that specific parameter.

The best fitting models for mother- and teacher-ratings were ADE models with scalar sex-limitation. For self-report at age 14 and 16, an ADE model without sex differences showed the best model fit. A slightly different set of candidate models emerged for father report (age 7, 10, 12) and self-report (age 12) analyses. Comparing the AIC of an ADE and ACE model, an ACE model showed better model fit. However, the confidence intervals of C included zero, suggesting an AE-scalar model to be the final best fitting model for father-report (all ages) and an AE no sex-differences model for self-report (age 12) (see Table S6, Supplemental Material, with the data presented by informant, age and model). Important to note is that we had a limited sample size at age 12 (N = 1704), so it is possible that we did not have enough power to detect D at this specific age (Rietveld et al. 2003).

The standardized estimates of the best fitting models are presented in Fig. 1, and a full overview of estimates of the contributions of genetic and environmental factors are included in Table S7 of the Supplemental Material. For mother-, father- and teacher-report (age 7–12), genetic influences accounted for 64–75% of the variance, with unique environmental influences accounting for 25–36% of the variance in self-control. For self-report, genetic influences accounted for 47–50% of the variance in self-control age 12–16, with the remaining variance attributed to unique environmental factors. These estimates are in line with heritability estimates of earlier research (Beaver et al. 2009; Boisvert et al. 2013).

Discussion

This study reports the construction of a self-control scale for children and adolescents, the ASCS, using the existing item pool in the widely used ASEBA questionnaires. Strengths of the study include the capitalization on widely available items to measure self-control, the use of a very large sample, the analysis of the heritability of self-control, and the examination of multiple aspects of the new scale’s psychometric functioning. The ASCS showed high internal consistency. In addition, we found high cross-sectional and longitudinal correlations between the ASCS and outcomes that were derived from the existing literature as being related to self-control (de Ridder et al. 2012; Moffitt et al. 2011), including well-being, educational achievement, and substance use. We also found that mother-, father-, self-, and teacher-reports were significantly correlated over time.

Adding to the psychometric soundness of the ASCS, we found heritability estimates paralleling earlier twin studies on self-control. A remarkable finding was that at age 12, genetic influences based on parent-reports accounted for 74–75% of the variance, while genetic influences based on self-reports accounted for only 47% of the variance. This pattern with higher heritability estimates for parent-reports than for self-reports has been reported by earlier studies on self-control and is a robust finding in the behavioral genetic literature (Anokhin et al. 2011; Beaver et al. 2009; Kan et al. 2014; Lemery-Chalfant et al. 2008). A body of empirical research attributes this finding to informant dependency; one important distinction between parent- and self-reports is that there is a single informant rating both twins (i.e., parent) versus different informants rating each twin (i.e., self-reports) (Bartels et al. 2007; Kan et al. 2014). However, the large genetic influence on self-control is in contrast to many non-genetic studies emphasizing the role of the ‘common’ environment rather than suggesting the role of genetics in the etiology of self-control, or the dynamical interaction between genes and environment. (cf. de Ridder et al. 2012; Pratt and Cullen 2000). This shows the need to bridge results from behavioral geneticists and developmental psychologists in order to investigate the underlying mechanisms of self-control development in childhood.

Gottfredson and Hirschi (1990) argue in their General Theory of Crime that self-control is formed in childhood and remains relatively stable over time (absolute levels of self-control may change over time, but an individual’s self-control relative to peers will be stable). Researchers using twin designs confirm the relative stability of self-control (cf. Beaver et al. 2008, 2013). As such, researchers in developmental psychology as well as in behavior genetics emphasize the importance of assessing self-control in youth to make inferences about adult adjustment. This is well illustrated in the recent work of Caspi et al. (2016), who assessed whether childhood risks forecast problems in adulthood. They found that children with low self-control were more likely to belong to high-cost economic burden groups as adults (e.g., using social welfare, smoking, crime, hospital stays, excessive weight). Policy makers are keen to improve well-being of adults by investing in child interventions. The returns of such an investment depends on the effectiveness of such interventions, and on the extent to which childhood outcomes predict adult adjustment. The ASCS can be used to assess self-control in youth, and thereby possibly for the prediction of adult adjustment.

In addition, the ASCS provide opportunities for secondary data-analyses. Specifically, our scale can be used to measure self-control in existing datasets, which include the ASEBA, but no questionnaires assessing self-control. Thereby, the ASCS may facilitate new research initiatives within existing research projects. For example, investigating the association between self-control and established psychopathologies or other dimensions of adult adjustment.

The results of the current study should be interpreted with some limitations in mind. While the present study has used a large population-based sample of Dutch twin youth (van Beijsterveldt et al. 2013), we recommend caution in generalizing our findings to other countries. An important next step therefore would be to replicate our findings in different populations. Vazsonyi and Belliston (2007) have investigated associations between family relationships, low self-control, and deviance across seven countries, reporting similar patterns across cultures. Furthermore, cross-cultural heritability studies for other childhood behavioral problems report on similar genetic architectures in different countries (cf. Porsch et al. 2016). Conducting comparable research would provide information on the cross-cultural validity and reliability of the ASCS. Replicating this study in twin data with a larger sample size of self-reports at age 12 is especially recommended, as research needs to clarify possible changes in environmental and genetic contributions to self-control from childhood to adolescence. Considering the international character of the ASEBA, and the wide variety of research groups including the ASEBA in their data collections, replicating this study is feasible.

Despite these limitations, the ASCS may provide insights and breakthroughs for longstanding questions and problems in the study of self-control, its links with adjustment and achievement across the lifespan, and its capacity for integration across multiple levels of analysis is especially high.

References

Achenbach T, Rescorla L (2001). Manual for the ASEBA school-age forms & profiles: an integrated system of multi-informant assessment. University of Vermont, Research Center for Children, Youth & Families, Burlington

Achenbach TM, Dumenci L, Rescorla LA (2002) Ten-year comparisons of problems and competencies for national samples of youth: self, parent, and teacher reports. J Emot Behav Disord 10(4):194–203

Anckarsäter H, Lundström S, Kollberg L, Kerekes N, Palm C, Carlström E et al (2011) The child and adolescent twin study in Sweden (CATSS). Twin Res Hum Genet 14(6):495–508

Anokhin AP, Golosheykin S, Grant JD, Heath AC (2011) Heritability of delay discounting in adolescence: a longitudinal twin study. Behav Genet 41(2):175–183

Bartels M, Boomsma DI, Hudziak JJ, van Beijsterveldt TC, van den Oord EJ (2007) Twins and the study of rater (dis) agreement. Psychol Methods 12(4):451

Beaver KM, Wright JP, DeLisi M, Vaughn MG (2008) Genetic influences on the stability of low self-control: results from a longitudinal sample of twins. J Crim Justice 36(6):478–485

Beaver KM, Schutt JE, Boutwell BB, Ratchford M, Roberts K, Barnes JC (2009) Genetic and environmental influences on levels of self-control and delinquent peer affiliation: results from a longitudinal sample of adolescent twins. Crim Justice Behav 36(1):41–60

Beaver KM, Connolly EJ, Schwartz JA, Al-Ghamdi MS, Kobeisy AN (2013) Genetic and environmental contributions to stability and change in levels of self-control. J Crim Justice 41(5):300–308

Boisvert D, Wright JP, Knopik V, Vaske J (2013) A twin study of sex differences in self-control. Justice Q 30(3):529–559

Boomsma D, Busjahn A, Peltonen L (2002) Classical twin studies and beyond. Nat Rev Genet 3(11):872

Bridgett DJ, Burt NM, Edwards ES, Deater-Deckard K (2015) Intergenerational transmission of self-regulation: a multidisciplinary review and integrative conceptual framework. Psychol Bull 141(3):602

Burt CH, Sweeten G, Simons R (2014) Self-control through emerging adulthood: instability, multidimensionality, and criminological significance. Criminology 52(3):450–487

Campbell DT, Fiske DW (1959) Convergent and discriminant validation by the multitrait-multimethod matrix. Psychol Bull 56(2):81–105

Cantril H (1965) The pattern of human concerns. Rutgers University Press, New Brunswick

Casey BJ (2015) Beyond simple models of self-control to circuit-based accounts of adolescent behavior. Annu Rev Psychol 66:295–319

Caspi A, Houts RM, Belsky DW, Harrington H, Hogan S, Ramrakha S et al (2016) Childhood forecasting of a small segment of the population with large economic burden. Nat Hum Behav 1(1):5

Cecil CAM, Barker ED, Jaffee SR, Viding E (2012) Association between maladaptive parenting and child self-control over time: cross-lagged study using a monozygotic twin difference design. Br J Psychiatry 201(4):291–297

Conners CK, Sitarenios G, Parker JDA, Epstein JN (1998a) The revised Conners’ Parent Rating Scale (CPRS-R): factor structure, reliability, and criterion validity. J Abnorm Child Psychol 26(4):257–268

Conners CK, Sitarenios G, Parker JD, Epstein JN (1998b) Revision and restandardization of the Conners Teacher Rating Scale (CTRS-R): factor structure, reliability, and criterion validity. J Abnorm Child Psychol 26(4):279–291

de Ridder DT, Lensvelt-Mulders G, Finkenauer C, Stok FM, Baumeister RF (2012) Taking stock of self-control: a meta-analysis of how trait self-control relates to a wide range of behaviors. Pers Soc Psychol Rev 16(1):76–99

Duckworth AL, Kern ML (2011) A meta-analysis of the convergent validity of self control measures. J Res Pers 45(3):259–268

Duckworth AL, Steinberg L (2015) Unpacking self-control. Child Dev Perspect 9(1):32–37

Duckworth AL, Gendler TS, Gross JJ (2014) Self-control in school-age children. Educ Psychol 49(3):1–19

Eaves LJ (1976) A model of sibling effects in man. Heredity 36:206–214

Finkenauer C, Engels R, Baumeister R (2005) Parenting behavior and adolescent behavioral and emotional problems: the role of self-control. Int J Behav Dev 29(1):58–69

Gottfredson M,R, Hirschi T (1990) A general theory of crime. Stanford University Press, Stanford

Hay C, Forrest W (2006) The development of self-control: examining self-control theory’s stability thesis. Criminology 44(4):739–774

Hennecke M, Bleidorn W, Denissen JJ, Wood D (2014) A three-part framework for self-regulated personality development across adulthood. Eur J Pers 28(3):289–299

Hogg C, Rutter M, Richman N (1997) Emotional and behavioural problems in children. NFER-NELSON

Hu L, Bentler PM (1999) Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct Equ Model 6(1):1–55

IBM Corp. (2012) IBM SPSS statistics for Windows, version 21.0. IBM Corp., Armonk

Jaddoe VW, van Duijn CM, Franco OH, van der Heijden AJ, van IIzendoorn MH, de Jongste JC et al (2012) The generation R study: design and cohort update 2012. Eur J Epidemiol 27(9):739–756

Kan K-J, van Beijsterveldt CEM, Bartels M, Boomsma DI (2014) Assessing genetic influences on behavior: informant and context dependency as illustrated by the analysis of attention problems of young adolescents. Behav Genet 44(4):326–336

Lemery-Chalfant K, Doelger L, Goldsmith HH (2008) Genetic relations between effortful and attentional control and symptoms of psychopathology in middle childhood. Infant Child Dev 17(4):365–385

Li M, Chen J, Li N, Li X (2014) A twin study of problematic internet use: its heritability and genetic association with effortful control. Twin Res Hum Genet 17(4):279–287

Lichtenstein P, Tuvblad C, Larsson H, Carlström E (2007) The Swedish twin study of child and adolescent development: the TCHAD-study. Twin Res Hum Genet 10(1):67–73

Maloney PW, Grawitch MJ, Barber LK (2012) The multi-factor structure of the Brief Self-Control Scale: discriminant validity of restraint and impulsivity. J Res Pers 46(1):111–115

Moffitt TE, Arseneault L, Belsky D, Dickson N, Hancox RJ, Harrington H et al (2011) A gradient of childhood self-control predicts health, wealth, and public safety. Proc Natl Acad Sci 108(7):2693–2698

Muraven M, Baumeister RF (2000) Self-regulation and depletion of limited resources: does self-control resemble a muscle? Psychol Bull 126(2):247

Muthén LK, Muthén BO (1998–2012) Mplus user’s guide, 7th edn. Muthén & Muthén, Los Angeles

Neale MC, Røysamb E, Jacobson K (2006) Multivariate genetic analysis of sex limitation and G × E interaction. Twin Res Hum Genet 9(4):481–489

Nelson EC, Hanna GL, Hudziak JJ, Botteron KN, Heath AC, Todd RD (2001) Obsessive-compulsive scale of the child behavior checklist: specificity, sensitivity, and predictive power. Pediatrics 108(1):e14-e14

Ormel J, Oldehinkel AJ, Sijtsema J, van Oort F, Raven D, Veenstra R et al (2012) The TRacking Adolescents’ Individual Lives Survey (TRAILS): design, current status, and selected findings. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 51(10):1020–1036

Piquero AR, MacIntosh R, Hickman M (2000) Does self-control affect survey response? Applying exploratory, confirmatory, and item response theory analysis to Grasmick et al.’s self-control scale. Criminology 38(3):897–930

Porsch RM, Middeldorp CM, Cherny SS, Krapohl E, Van Beijsterveldt CE, Loukola A et al (2016) Longitudinal heritability of childhood aggression. Am J Med Genet Part B 171(5):697–707

Pratt TC, Cullen FT (2000) The empirical status of Gottfredson and Hirschi’s general theory of crime: a meta-analysis. Criminology 38(3):931–964.

Rebollo I, de Moor MHM, Dolan CV, Boomsma DI (2012) Phenotypic factor analysis of family data: correction of the bias due to dependency. Twin Res Hum Genet 9(3):367–376

Rietveld MJH, van Der Valk JC, Bongers IL, Stroet TM, Slagboom PE, Boomsma DI (2000) Zygosity diagnosis in young twins by parental report. Twin Res Hum Genet 3(3):134–141

Rietveld MJH, Posthuma D, Dolan CV, Boomsma DI (2003) ADHD: sibling interaction or dominance: an evaluation of statistical power. Behav Genet 33(3):247–255

So P, Greaves-Lord K, Van der Ende J, Verhulst FC, Rescorla L, de Nijs PF (2013) Using the child behavior checklist and the teacher’s report form for identification of children with autism spectrum disorders. Autism 17(5):595–607

Tangney JP, Baumeister RF, Boone AL (2004) High self-control predicts good adjustment, less pathology, better grades, and interpersonal success. J Pers 72(2):271–324

Turner MG, Piquero AR (2002) The stability of self-control. J Crim Justice 30(6):457–471

van Beijsterveldt CEM, Groen-Blokhuis M, Hottenga JJ, Franić S, Hudziak JJ, Lamb D et al (2013) The Young Netherlands Twin Register (YNTR): longitudinal twin and family studies in over 70,000 children. Twin Res Hum Genet 16(1):252–267

Vazsonyi AT, Belliston LM (2007) The family→ low self-control→ deviance: a cross-cultural and cross-national test of self-control theory. Crim Justice Behav 34(4):505–530

Williams MWM, Fletcher RB, Ronan KR (2007) Investigating the theoretical construct and invariance of the self-control scale using confirmatory factor analysis. J Crim Justice 35(2):205–218

Funding

NTR acknowledges Twin-family database for behavior genetics and genomics studies (NWO 480-04-004); Genetics of Mental Illness: European Research Council (ERC-230374); Genetic influences on stability and change in psychopathology from childhood to young adulthood (NWO/ZonMW 91210020); Determinants of Adolescent Exercise Behavior (NIH-1R01DK092127-01). NWO-large investment (480-15-001/674: Netherlands Twin Registry Repository: researching the interplay between genome and environment.), The Consortium on Individual Development (CID), which is funded through the Gravitation program of the Dutch Ministry of Education, Culture, and Science and the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (NWO Grant Number 024.001.003). M. Bartels is supported by a VU University Research Chair position, The Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research (NWO): “Genetic and Family influences on Adolescent psychopathology and Wellness” (NWO 463-06-001); “A twin-sib study of adolescent wellness” (NWO-VENI 451-04-034). M. Bartels, D. I. Boomsma, and C. Finkenauer are supported by the European Union Seventh Framework Program (FP7/2007-2013, Grant No. 602768). Y. Willems is supported by NWO (Research Talent, 406-15-132).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Yayouk E. Willems, Conor V. Dolan, Catharina E. M. van Beijsterveldt, Eveline L. de Zeeuw, Dorret I. Boomsma, Meike Bartels, and Catrin Finkenauer declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Data collection complied with current APA Ethical Principles of Psychologists and Code of Conduct and was approved by the medical ethical review committee of the VU Medical Center Amsterdam (NTR25052007).

Human and Animal Rights and Informed consent

This article does not contain any studies with animals performed by any of the authors. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Edited by Wendy Slutske.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Willems, Y.E., Dolan, C.V., van Beijsterveldt, C.E.M. et al. Genetic and Environmental Influences on Self-Control: Assessing Self-Control with the ASEBA Self-Control Scale. Behav Genet 48, 135–146 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10519-018-9887-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10519-018-9887-1