Abstract

Presentism faces the following well-known dilemma: either the truth-value of past-tense claims depends on the non-existing past and cannot be said to supevene on being, or it supervenes on present reality and breaks our intuition which says that the true past-tense claims should not depend on any present aspect of reality. The paper shows that the solution to the dilemma offered by Kierland and Monton’s brute past presentism, the version of presentism according to which the past is supposed to be both a fundamental and present aspect of reality, is implausible and proposes how to cure presentism: the dillema can be avoided by taking a third road consisting of introducing dynamics into presentism in the form of the real passage of time. Dynamic presentism, which is constructed in such a way, can overcome the dilemma by providing an ontological basis for the past-tense propositions in the form of the real past. Dynamic presentism also offers a rationale for treating the future as being open.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Presentism, the view that the way things are is the way things presently are,Footnote 1 faces the following well-known difficulty for all presentists: what is the ontological basis for true past-tense claims such as, for example, ‘Socrates was a philosopher’, if the past does not exist. This entails the following dilemma which Kierland and Monton (2007) tried to solve:

Dilemma: either truth-value of past-tense claims depends on the non-existing past and cannot be said to supevene on being, or it supervenes on present reality and breaks our intuition which says that the true past-tense claims should not depend on any present aspect of reality.Footnote 2

Solving this dilemma, the authors developed the view which is a version of presentism they termed brute past presentism (BPP).Footnote 3 According to this view, in addition to the standard thesis of presentism which claims that the only things that exist are presently existing things, it claims that the past is supposed to be a fundamental aspect of reality and—at the same time—a present aspect of reality. I would like to show that this is a strategy which amounts to the old adage of two steps forward, one step back: the authors interestingly push forward presentism when they claim that the past is supposed to be a fundamental aspect of reality, however, in the next step, they retreat by claiming that the past is a present aspect of reality. This diagnosis is put forward in the second section of the paper, while the third one introduces a potential remedy to this weakness in the form af modified versions of dynamic presentism (DP),Footnote 4 that may restore the patient to full health: not only does DP try to provide presentists with an ontological basis for the past-tense propositions in the form of the real past, but it also offers a rationale for treating the future as being open as an extra bonus. The paper ends with some conclusions.

2 The Problem: Diagnosis

According to BPP,

-

1.

The way things are is the way things presently are.

Which entails that

-

2.

The only things that exist are presently existing things.

As concerns the the truth-value of past-tense claims, refering to our intuition the authors claim that

-

3.

‘The truth-value of past-tense claims is determined by the past.’ (2007: 485)

But how this can be done? The authors answer:

-

4.

‘The shape of the past is what makes past-tense claims true.’ (2007: 492)

-

5.

‘This shape does not consist in a structure of things having properties and standing in relations to one another.’ (2007: 491)

Then the essential question arises as to what is the past if—according to presentism—the past does not exist. Kierland and Monton (2007) give us a number of declarations clarifying how they understand the past:

-

6.

The past is a fundamental aspect of reality different from things and how things are. (2007: 485, 496)

-

7.

The past is what has happened: what things existed and how they were. (2007: 491)

But what does it mean that objests like Socrates existed and somethings have happened if presentism only talks about what does and does not exist? They try to solve this question by means of the sidestep strategy:

-

8.

‘The past is an aspect of reality, even though no past things are. How can this be? There is no reductive explanatory answer to this question.’ (2007: 491)

However, according to all standard versions of presentism, only the present exists, so the authors felt to be forced to admit that:

-

9.

‘The past is a present aspect of reality.’ (2007: 496)

There is no contradiction between (6), saying that the past is a fundamental aspect of reality different from things and how things are, and (9) because Kierland and Monton assume that

-

10.

Reality is not exhausted by things and how things are. (2007: 485, 491)

Nonetheless, a more essential difficulty arises as a consequence of the proposed solution. Namely, the authors wanted to solve the Dilemma: either the truth-value of past-tense claims depends on the non-existing past and cannot be said to supevene on being, or it supervenes on the present reality and breaks our intuition which says that true past-tense claims should not depend on any present aspect of reality. Did they succeed? I claim that not at all because Kierland and Monton smuggle in through the back door of their ideology what they thought they had ruled out of the ontology, saying that the past is a present aspect of reality. In the solution preferred by them, to avoid the second horn of the Dilemma they assumed, firstly, that the truth-value of past-tense claims is determined by the past (3), and, secondly, that the past is a fundamental aspect of reality different from things and how things are (6), nevertheless then the first horn (if the truth-value of past-tense claims depends on the non-existing past, then it cannot be said to supevene on being) fought them off back to the second horn and forced them to reject the stipulation (let us call it after the authors P) that the past-tense claims do not depend on any present aspect of reality for their truth-value. The rationale for such a move was that reality is not exhausted by presently existing things and how things are (2007: 496). This is why, according to Kierland and Monton, ‘P is not intuitively true’ (2007: 496).

The point is, however, that even if we agree to deny the existence of facts as the authors do (2007: 497), we will still believe that Socrates is part of the real past and not of a present aspect of reality, so P seems to be still intuitively true contrary to what Kierland and Monton claimed. It is hard to accept that the past is a present aspect of reality (9): it is not a present aspect of reality that Socrates was a philosopher and that he was convicted by the Athenians. Srictly speaking, we have, of course, a history of philosophy but it is not the history that made Socrates a philosopher but rather the other way around: that he was a philosopher made our history and us as we are. And we are resposible in no way for his conviction by the Athenians and it is no aspect of the present world; we are really responsible but only for our own faults. McFetridge, Keller, and by Sanson and Caplan noted that we do not want a mere correlation between what is true and what the world is like; rather, we want the truth of a proposition to be explained by how things are in the world.Footnote 5 Kierland and Monton do not offer us such an explanation. As long as a plausible explantion of the ontological status of the past is not offered, such a solution cannot be regarded as reasonable.

Of course, our knowledge is fallible and perhaps P is just the thesis that should be changed. I would like to show, however, that P can be saved in a plausible way which has some other virtues for the presentists and therefore there is no need to reject it. Before I introduce the proposed improvement of presentism, I would like to briefly analyse Kierland and Monton’s second strategy of solving the Dilemma, one which is connected with a different reading of P.Footnote 6 According to this second strategy, in the intuition that past-tense claims do not depend on any present aspect of reality for their truth-value, the past should be understood as a one big event (let us call it ‘the paste’ after the authors) which consists of all past events, such as that Socrates died, World War II occurred, and Mt. St Helens erupted. Then—Kierland and Monton (2007: 496) claim—‘”The paste occurred’ is a true claim about a past event,’ and P is intuitively true. One can certainly agree with Kierland and Monton, but only when the past is not a present aspect of reality (and it is a real past which means that the truth-value of past-tense claims depends on the non-existing past), because when the past is a present aspect of reality, the second horn of the Dilemma is encountered (that true past-tense claims should not depend on any present aspect of reality), contrary to what is claimed by the authors.

So, is the patient terminally ill without any chances of surviving? I claim that this is not the case at all. Kierland and Monton (2007) were on the right track when they claimed that the truth-value of past-tense claims is determined by the past (3); and that the past is a fundamental aspect of reality which is different from things and how things are (6); and that the past is what has happened: what things existed and how they were (7). However, it is hard to accept that the past is a present aspect of reality as it was argued above.

Where, then, did Kierland and Monton make a slip? The point is that the fundamental thesis of presentism (2) ‘The only things that exist are presently existing things’ seems, at first glance, to block any other understanding of the past than that which is offered by (9) (‘the past is a present aspect of reality’). The thesis (8), let us recall, ‘The past is an aspect of reality, even though no past things are. How can this be? There is no reductive explanatory answer to this question,’ seems to confirm this diagnosis of the authors’ approach. However, our intuition, which is so highly estimated by them, together with our everyday experience, gives us a simple answer to these exciting mysteries: the past is not a present aspect of reality, but by definition past. And it is the passage of time that is responsible for the fact that Socrates and his contemporaries do not exist, although they did exist, and this concerns all other past things as well.

Strictly speaking, Kierland and Monton maintain that the past ‘is what has happened: what things existed and how they were’ (7), however, they do not explain what this is and how it is possible that something has existed and does not exist? Nor have they explained what is the origin of the phenomena that something existed but no longer exists. They simply declare that there is no reductive explanatory answer to this question (8), and we are left in the dark as to how this is possible; the past is declared to be brute and that it is a present aspect of reality.

Sider (2001: 39–41) claims that introducing ‘primitive tensed properties of the world’ as a solution to the grounding objection is a case of cheating. Answering this objection, Kierland and Monton compare brute past presentism to brute disposition and brute counterfactuals (2007: 494) and suggest that the latter ‘can be reductively explained’ so they can be accused of cheating. And they add: ‘Maybe something similar can be said about a brute past, but that requires independent motivation.’ So, let us show that such a motivation is known for philosophers and, what is more, enjoys a very long pedigree. Namely, let us look at the following passage from the 11th book of St. Augustine’s Confessions:

Boldly for all this dare I affirm myself to know thus much; that if nothing were passing, there would be no past time: and if nothing were coming, there should be no time to come: and if nothing were, there should now be no present time. Those two times therefore, past and to come, in what sort are they, seeing the past is now no longer, and that to come is not yet ? As for the present, should it always be present and never pass into times past, verily it should not be time but eternity. If then time present, to be time, only comes into existence because it passeth into time past; how can we say that also to be, whose cause of being is, that it shall not be: that we cannot, forsooth, affirm that time is, but only because it is tending not to be? (St. Augustine 1912: 239)

This observation is simple but one which is hard to overestimate: if nothing were passing, there would be no past time, in other words, if there was no flow of time, there would be no past time. It means that every presentist who wants to speak seriously about past time, should accept the existence of the flow of time.Footnote 7 Then, undoubtedly, someone who claims, as Kierland and Monton do, that the past is a fundamental aspect of reality (6), should accept existence of the flow of time. And, naturally, St. Augustine offers us in this way an explanation of the origin of past time which is lacking: time present, to be time, only comes into existence because it passes into time past. What is also important, our intuition and our experience strongly confirm that it is the flow of time which is responsible for the fact that Socrates existed and was convicted, and that he does not exist any more. Unfortunately, conceptions such us the flow of time or becoming do not appear in Kierland and Monton’s paper.

Thus the question arises as to why Kierland and Monton, as is the case with many other presentists, did not refer to the flow of time? There seem to be three reasons which are responsible for this: firstly, conceptual difficulties connected with the idea of the flow of time; secondly, the fact that the main thesis of presentism is introduced with only one ontological thesis (1 or 2), which says nothing about the flow of time; and thirdly, the fact that presentism makes use of the notion of existence which allows only the dichotomy of exist or do not exist, and which does not permit the introduction of the metaphysical category for objects that existed and do not exist. In other words, the notion of existence exploited by the presentists, and by Kierland and Monton as well, has a static character, that is, this is the notion of existence (or non-existence) at some fixed moment of time, and it does not make it possible to talk about ontological changes in time.Footnote 8 All these reasons deprive presentism of dynamics and make it impossible to find an ontological basis on which the truth-value of past claims can supervene.

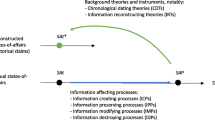

So, in summary, the proposed diagnosis of the weakness of BPP and other static versions of presentism is the following: the lack of dynamics and—in consequence—the lack a plausible metaphysical base on which truth-value of past-tense sentences can supervene. The next section tries to find a remedy for these flaws.

3 A Remedy with an Extra Bonus

It was already suggested in the previous section, that every presentist who wants to speak seriously about past time should accept the existence of the flow of time and introduce it into her/his ontology. Kierland and Monton were close to the solution which is going to be proposed in this paper when they claimed that, for the presentist, the past is a fundamental aspect of reality (6) and that the past is what has happened: what things existed and how they were (7). Unfortunately, they also maintained that the past is brute and although the brute past is supposed to form a sui generis metaphysical category, an explanation of what the brute past is, according to the authors, unattainable:

The brute past has an intrinsic nature. Given what we say next, we like to think of this intrinsic nature in terms of the past having a certain ‘shape’. This shape does not consist in a structure of things having properties and standing in relations to one another. The past is an aspect of reality, even though no past things are. How can this be? There is no reductive explanatory answer to this question. The crucial feature of brute past presentism is that is postulates a sui generis metaphysical category, one independent of things and how they are. (Kierland and Monton 2007: 491)

Of course, any opponent of the idea of the introduction of the flow of time into the ontology of presentism can object: not so fast, wait a moment: have you perhaps explained what is the flow of time, or perhaps you are trying to explain ignotum per ignotius? S/he may also object that a simple admixture of the thesis about the flow of time to her/his main thesis (1/2) does not change the situation of the presentist too much because, according to the main ontological thesis of presentism, only the present exists and thus there will still be missing a plausible metaphysical category of the past on which the truth-value of past-tense claims can supervene.

I would answer such doubts by saying that a deeper change in the ontological position of the presentist is indeed necessary. This is a change which introduces real dynamics into this view and allows us to say what did exist, however, does not exist. I would also add that a plausible explanation of what constitutes the flow of time was offered by Broad (1938) in terms of the absolute becoming of events, that is, their coming to pass,Footnote 9 and that this approach can be developed in the dynamic and full-blooded versions of presentism which deserve to be called dynamic presentism (DP). Let us briefly introduce two such presentist solutions developed by means of the notion becoming after Gołosz (2013, 2017c), and by means of the notion of dynamic existence after Gołosz (2013, 2015, 2018).

So, let us start with the first approach and introduce this version of DP in the following form (expressed in tensed language):

Becoming: The events which our world consists of become (come to pass).

where becoming, as Broad’s absolute becoming, is a primitive notion which cannot be further analysed in terms of a non-temporal copula and some kind of temporal predicate.Footnote 10 This thesis expresses, of course, the reality of the flow of time, however, it is easy to show that Becoming also leads precisely to the ontological thesis of presentism.Footnote 11 To show this, we should only notice that Becoming says that events become, that is, they come into being and then they pass, and recall that, according to the long presentist tradition, the present can be identified with what exists.Footnote 12 It means exactly that only present events exist. This formulation of presentism, however, avoids the triviality objection because neither the notion of the present nor the notion of time are involved in Becoming.Footnote 13

Now, what remains is to introduce three definitions:

-

The present ≡ The totality of events which become (come to pass).

-

The past ≡ The totality of events which became (came to pass).

-

The future ≡ The totality of events which will become (will come to pass).

The first of these definitions was adopted following the above mentioned presentist tradition of identifying the present with what exists, the second and the third ones were assumed by analogy. Such a version of presentism has some virtues which speak for themselves:Footnote 14

-

(i)

According to Becoming, the present is continuously changing, which means that it allows the expression of a dynamic character of reality, which presentism in the form of a single thesis of the form (1, 2) is not able to do.

-

(ii)

It avoids the question of the rate of time’s passage because—as emphasized by Broad—the notion of becoming is primitive and unrelated to anything else, and especially it is not related to time.

-

(iii)

This formulation of presentism also avoids the triviality objection because the notion of the present is not involved in Becoming and thus this thesis is not trivial.

-

(iv)

This version of presentism provides us with the metaphysical category of the past which we have sought.

From the point of view of this paper, the last virtue is especially important: this version of presentism provides us with the metaphysical category of the real past which we have sought: the past consists of the totality of events which became (came to pass). Thanks to this, it allows us to differentiate between actual events, such as, for example, the case of Socrates, which did become, and fictions such as the capture of Cerberus by Heracles, which did not become.

At this point, Kierland and Monton could oppose: Becoming cannot be treaed as a remedy for positions such as BPP because we rejected the ontology of facts and our ontology is based on things and the way they are; we emphasized that fact–talk is always parasitic on something which is metaphysically more fundamental.Footnote 15 And that is why we cannot accept such a solution to our Dilemma—they could add.

I would answer such an objection by claiming that the notion of becoming and the dynamic version of presentism presented can be further developed in such a way that things and the way they are would be included in ontology as fundamental objects. This is precisely the second version of presentism which was mentioned above and which is introduced in Gołosz (2013, 2015, 2018). It is based on the notion of the dynamic existence of things to emphasize a fundamental difference between things and events—while existence of both things and instantaneous events has a dynamic character, the former do not cease to be but persist by enduring, that is by keeping their strict (literal or numerical) identity over time:Footnote 16

Dynamic Reality: All of the objects that our world consists of exist dynamically.

where Dynamic Reality (DR) is expressed in the tensed language and the notion of dynamic existence is a primitive notion (just as Broad’s absolute becoming) which can be roughly characterised by the set of postulates:

-

(i)

the notion of dynamic existence is tensed;

-

(ii)

things that dynamically exist endure;

-

(iii)

events (which are acts of acquiring, losing or changing properties by dynamically existing things and their collections) dynamically exist in the sense of coming to pass.

The term “objects” is here used in such a way that it applies to things and events, however things are treated here as primary objects, while events are secondary.Footnote 17

DR is accompanied by the three definitions (similarly to Becoming):

-

The present ≡ The totality of objects that dynamically exist.

-

The past ≡ The totality of objects that dynamically existed.

-

The future ≡ The totality of objects that will dynamically exist.

Again, as in the case of Becoming, DR expresses at the same time the reality of the flow of time and the ontological thesis of presentism in the form of one single thesis. DR has the same virtues (i–iv) as Becoming (with swapping Becoming for DR, of course) and once again, from the point of view of this paper, the last virtue is especially important: this version of presentism also provides us with the metaphysical category of the real past which we need so much: the past consists of the totality of objects that dynamically existed.

DR, however, has two essential advantages not only over Becoming, but over every other version of presentism: first, the endurance of things is here a simple logical consequence of the dynamic existence of things, that is, it is a consequence of their way of existence proposed in this thesis. Contrary to what is commonly assumed by the presentists, the enduring of things is not a logical consequence of presentist theses of type (1/2) as shown by Brogaard.Footnote 18

The second advantage is even more important: the notion of dynamic existence which is applied in it is supposed to supersede the ordinary notion of existence which is standardly used by the presentists (and eternalists as well) and which has a static character, that is, it is a fixed existence in a fixed moment of time which is not appropriate for expressing the transitory character of the present. From this that I exist—in the tensed meaning of the standard term “exist”—in no way follows that I will not exist, neither that I am changing. Similarly—when we use tensed language—the standard notion of existence does not explain how it is possible and what it really means that the past existed and that the future will exist although both do not exist (in the tensed meaning of the term “exist”).

This is very important for two reasons: first, because it means that it makes no sense to ask whether things that dynamically existed do (statically) exist or do not (statically) exist: the notion of dynamic existence supersedes the notion of (static) existence and introduces more metaphysical categories than the latter. While the latter introduces only two fixed metaphysical categories of what exists and what does not exist, the former introduces six metaphysical categories which are continuously changing: the past (things and events that dynamically existed); the present (things and events that dynamically exist); the future (things and events that will dynamically exist); and their complements, that is, the past’ (things and events that did not dynamically exist); the present’ (things and events that does not dynamically exist); and the future’ (things and events that will not dynamically exist). So, for example, Socrates belongs to the past, while Zeus and Apollo belong to its complement, that is, the past’. They (Zeus and Apollo, of course) belong to the present’ and to the future’ as well. What should be emphasised, once again, is that all six categories are continuously changing, namely the past and the future’ are growing, the future and the past’ are shrinking, while the present—to say it meataphorically—is ‘moving’ toward the direction which we call the future (I would like to empahsize here that the term ‘move’ was not used in DR).

There is a second reason to be considered and which is mentioned above, namely that Kierland and Monton (2007: 492) complained about the lack of a metaphysically perspicuous language for describing the ‘shape of the past.’Footnote 19 The last version of dynamic presentism equipped with the notion of dynamic existence provides us with a language which allows us to talk not only about Kierland and Monton’s ‘shape of the past,’ but also about a structure of past things, their having properties and standing in relation to one another. Thus it allows us to say, for example, that Heraclitus (who dynamically existed) didn’t like Pythagoras (who dynamically existed), or that Heraclitus (who dynamically existed) was a native of the city of Ephesus (which dynamically existed). The language of DP also enables us to talk about the past, the present and the future, as they are changing, and to differentiate between objects like Socrates—on the one hand—that did dynamically exist, and Zeus and Apollo—on the other—that did not dynamically exist. What this means, and is of fundamental importance, is that, in this way, the notion of dynamic existence and DP provide presentists with a rationale for introducing and making use of tensed language:Footnote 20 this is exactly the dynamic existence of the world which is resposible for this that it is continuously changing, and that although Socrates (dynamically) existed, does not (dynamically) exist any more, and we should speak about him using the past tense. And, of course, the same concerns all other past objects.

At the end of this section, I would like to mention an additional bonus provided by DP concerning the problem of being-supervenience (or truthmaking). Namely, the presentists who try to respond to the objection from being-supervenience, usually assume that they need not look for an ontological basis for (contingent) future-tense claims because the claims about the future are not determined and lack truth-value.Footnote 21 But what is the origin of this asymmetry between the fixed past and (probably) open future? We cannot change the past no matter how strongly we would like to do this. But we have traces of it in our memory and in the world around us. Conversely, the future seems to be open—our experience seems to suggest this openness and quantum mechanics confirms this conviction—and perhaps it depends on our actions. How it is possible? Physics is silent on this issue; the physical laws describing the electrodynamic, strong and gravitational interactions are invariant under time reversal and as such cannot distinguish any direction of time. In turn, weak interactions are not time reversal invariant, but they are not involved in the processes leading to the coming into being of the traces of the past which we observe in everyday life.Footnote 22 Presentism in its standard form (1 or 2) is also silent on this issue: no ‘move’ of the present and no asymmetry of time follows from (1 or 2). DP in both versions provides us with a simple metaphysical solution to this exciting mystery: the past has already become or dynamically existed, as such is fixed and directly unavailable, we can only get to know it by its traces. Contrary to the past, which dynamically existed (or became) and as such is fixed and cannot be changed, the future looks as if it were open: it does not dynamically exist yet, it will only come into (dynamic) existence and, for this reason, we can probably influence it, at least sometimes.Footnote 23

It should also be emphasized that while brute past presentism can be accused of being an ad hoc solution to the objection from being-supervenience,Footnote 24DP cannot be: both versions of presentism, and the notions of becoming and dynamic existence which these versions of presentism are based on, were introduced as a solution to the difficulty with the explanation of what the flow of time consists in and the explanation of the ontological status of past, present and future objects is an additional bonus.

4 Conclusions

I have tried to show that Kierland and Monton interestingly extended our knowledge about presentism and its ontological basis for past-tense claims when they proposed that the past should be regarded as a fundamental aspect of reality. Unfortunately, after this move they retreat and assumed that this fundamental aspect of reality is a present aspect of reality: the rub is that the past is a past and not a present aspect of reality. It was also recalled—as noticed long ago by St. Augustine—that if there was no flow of time, there would be no past time. So, the cure proposed in this paper consists of including the flow of time into the ontology of presentism and making presentism a dynamic view of reality. The world in which we live—as we see it—is the world in statu nascendi, in which everything is changing and DP tries to describe such a world. The dynamic ontology of this view provides the presentists with the correct ontological basis for both present- and past-tense claims.

Two versions of DP were presented which are based on the notions of becoming and dynamic existence and which provide us with metaphysical categories of the past—real and dynamic past as we know from our experience—the past as the totality of events which became (came to pass in the first version of dynamic presentism), and the past as the totality of objects that dynamically existed (in the second version of dynamic presentism). Not only do they introduce the past as growing, as it should be expected, but also both introduce the asymmetry between the fixed past and the (probably) open future (events,which are acts of acquiring, losing or changing properties by dynamically existing things and their collections, dynamically exist in the sense of coming to pass).

The latter of these two versions (based on the notion of dynamic existence) seems to be more promising because it entails as its direct consequence the enduring of things which is commonly assumed by the presentists, and—what is even more important—it eliminates a potential tension between becoming and existence which is still present in the former version of DP because the notion of existence is not changed there. The version based on the notion of dynamic existence can eliminate this tension because the notion of dynamic existence which is applied in it is supposed to supersede the ordinary notion of existence which is standardly used by presentists (and eternalists as well), and which has a static character (it is a fixed existence in a fixed moment of time). Thanks to this, instead of only two fixed metaphysical categories of what exists and what dos not exist, we receive six metaphysical categories which are continuously changing: the past (things and events that dynamically existed); the present (things and events that dynamically exist); the future (things and events that will dynamically exist); and their complements, that is, the past’ (things and events that did not dynamically exist); the present’ (things and events that do not dynamically exist); and the future’ (things and events that will not dynamically exist). The future defined in such a way is (probably) open, while the past defined in such a way is fixed and provides adherents of this version of DP with a missing ontological basis on which truth-value of past-tense claims can supervene.

For all these virtues, the versions of DP presented in this paper—and especially the one based on the notion of dynamic existence—deserve to be regarded as the potential successors to traditional presentism.

Notes

I follow here Hinchliff (1996: 123) and Kierland and Monton (2007: 485). As noted by Kierland and Monton (2007: 485), this thesis entails the more popular formulation of presentism: the only things that exist are presently existing things. This more popular formulation of presentism will be used in the paper as well.

Kierland and Monton (2007: 495–496).

The authors add that they ‘are not yet fully convinced by this attempt’, nonetheless, they ‘think it important that, even if it ultimately fails, such a defence of this version of presentism be represented in the literature’ (2007: 486).

Other versions of dynamic presentism are analysed by Dainton (2014: 87–95).

In Kierland and Monton’s paper (2007: 496), this is the the first strategy which is analysed.

See Gołosz (2018).

“To ‘become present’ is, in fact, just to ‘become’, in an absolute sense; i.e., to ‘come to pass’ in the Biblical phraseology, or, most simply, to ‘happen’. Sentences like ‘This water became hot’ or ‘This noise became louder’ record facts of qualitative change. Sentences like ‘This event became present’ record facts of absolute becoming.” (Broad 1938: 280–281)

See Gołosz (2017c: 292).

See, for example, Prior (1970: 247): ‘the presentness of an event is just the event. The presentness of my lecturing, for instance, is just my lecturing’; Christensen (1993: 168): ‘To be present is simply to be, to exist, and to be present at a given time is just to exist at that time—no less and no more’; and Craig (1997: 37): ‘Presentness is the act of temporal being.’

The triviality problem for presentism consists in this that when we examine its ontological thesis, saying that the only things that exist are presently existing things, it turns out that this thesis is trivially true or trivially false, depending on the way we understand the verb ‘exists’: in the tensed or in the tenseless way. See, for example, Merricks (1995: 523), Savitt (2006), Gołosz (2013), and discussions of the problem in Zimmerman (2004).

See Gołosz (2017c: 293).

Kierland and Monton (2007: 497): ‘we deny the existence of facts altogether. As we explained in Sect. 3, we think fact–talk is always parasitic on something metaphysically more fundamental. In the case of talk of facts about present things, it’s the present things and how they are that is more fundamental. In the case of talk of facts about the past, it’s the past itself which is more fundamental.’

See Gołosz (2018: 404). There are two opposite views on persistence: endurantism and perdurantism. According to the latter, things perdure if they persist through time by having temporal parts, and persisting things are treated as mereological aggregates of temporal parts, none of which are strictly identical with one another. The enduring of things is usually defined as a persistence over time by being wholly present at each time but, as noticed by Merricks (1994: 182), ‘(…) the heart of the endurantist’s ontology is expressed by claims like ‘[object] O at t is identical with [object] O at t*’.’ That is why, for the author of this paper, this second condition alone suffices for the definition of endurantism and is a better criterion of endurance, so it will be used in what follows.

See Gołosz (2018: 403).

From the idea that the present exists while the past and the future do not exist, one cannot infer that the persisting object keeps its strict identity. It is possible, after all, that an object persists in such a way that it is four-dimensional and its temporal parts (or stages)—not strictly identical with themselves—are coming consecutively into being. See Brogaard (2000: Sect. 3) and Gołosz (2018: 406–407).

‘This shape does not consist in a structure of things having properties and standing in relations to one another.’ (2007: 491) ‘Of course, we have no independent, metaphysically perspicuous language for describing this shape (and we don’t propose to introduce one), but that does not matter.’ (2007: 492)

In Gołosz (2019), it is argued that the debate between presentism and eternalism can be understood as a debate concerning the problem whether the tensed structure of our language corresponds to the metaphysical structure of the world.

See the famous Aristotle’s problem of sea-battle tomorrow (De Interpretatione: ch. 9), and, for example, Kierland and Monton (2007: 486).

This ‘can’ follows from the possibilty which cannot be a priori excluded that our world will turn out to be deterministic after all because, for example, the quantum gravity which we are looking for will be deterministic in accordance with Einstein’s expectations. But even if it is determined and not open, it does not dynamically exist yet and will just come into (dynamic) existence.

See fn. 3.

References

Aristotle (1975) De interpretatione. In: Aristotle’s Categories and de interpretione (Ackrill JL, trans). Clarendon Press, Oxford

Augustine S (1912) The confessions of St. Augustine (Watts W, trans), vol 2. William Heinemann, London

Broad CD (1938) Examination of McTaggart’s philosophy. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Brogaard B (2000) Presentist four-dimensionalism. The Monist 83:341–356

Christensen FM (1993) Space-like time. University of Toronto Press, Toronto

Craig WL (1997) Is presentness a property? Am Philos Q 34:27–40

Dainton B (2014) Time and space. Routledge, New York

Gołosz J (2013) Presentism, eternalism, and the triviality problem. Logic Log Philos 22:45–61. https://doi.org/10.12775/LLP.2013.003

Gołosz J (2015) How to avoid the problem with the question about the rate of the time’s passage. Rev Port Filos 71:807–820. https://doi.org/10.17990/RPF/2015_71_4_0807

Gołosz J (2017a) Weak interactions: asymmetry of time or asymmetry in time? J Gen Philos Sci 48:19–33. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10838-016-9342-z

Gołosz J (2017b) The asymmetry of time: a philosopher’s reflections. Acta Phys Pol B 48(10):1935–1946. https://doi.org/10.5506/APhysPolB.48.1935

Gołosz J (2017c) Presentism and the flow of time. Axiomathes 27:285–294. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10516-016-9305-3

Gołosz J (2018) Presentism and the notion of existence. Axiomathes 28:395–417. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10516-018-9373-7

Gołosz J (2019) Meyer’s struggle with presentism or how we can understand the debate between presentism and eternalism. Logic Log Philos 28:731–751. https://doi.org/10.12775/LLP.2019.018

Hinchliff M (1996) The puzzle of change. Philos Perspect 10:119–136

Keller S (2004) Presentism and truthmaking. In: Zimmerman DW (ed) Oxford studies in metaphysics, vol 1. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Kierland B, Monton B (2007) Presentism and the objection from being-supervenience. Australas J Philos 85(3):485–497. https://doi.org/10.1080/00048400701572279

McFetridge IG (1977) Truth, correspondence, explanation and knowledge. In: Haldane J, Scruton R (eds) Logical necessity & other essays, vol 1990. Aristotelian Society, London, pp 29–52

Merricks T (1994) Endurance and indiscernibility. J Philos 91:165–184

Merricks T (1995) On the incompatibility of enduring and perduring entities. Mind 104:523–531

Prior A (1970) The notion of the present. Stud Gen 23:245–248

Sanson D, Caplan B (2010) The way things were. Philos Phenomenol Res 81:24–39

Savitt S (2006) Presentism and eternalism in perspective. In: Dieks D (ed) The ontology of spacetime, vol 1. Elsevier, Amsterdam

Sider T (2001) Four-dimensionalism: an ontology of persistence and time. Clarendon Press, Oxford

Sklar L (1974) Space, time, and spacetime. University of California Press, Berkeley

Zimmerman DW (ed) (2004) Oxford studies in metaphysics, vol 1. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Acknowledgements

The research contained in this paper has been supported by the National Science Centre, Poland, Grant OPUS 11 No. 2016/21/B/HS1/00807.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gołosz, J. Brute Past Presentism, Dynamic Presentism, and the Objection from Being-Supervenience. Axiomathes 31, 211–223 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10516-020-09489-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10516-020-09489-5