Abstract

This randomized experiment tested whether the inclusion of a “something else” response option for a question about sexual identity in a national health survey would significantly moderate estimated differences between sexual identity subgroups in terms of various health outcomes, including substance use and reproductive health. We conducted secondary analyses of data from five consecutive years of the National Survey of Family Growth (NSFG; 2015–2019), where two large national half-samples were randomly assigned to receive one of two different versions of a question about sexual identity (a four-category version that included a “something else” response option or a three-category version omitting this option). We focused on national estimates of differences between subgroups defined by sexual identity. Multivariable models indicated that the estimated subgroup differences changed in a statistically significant fashion when using the four-category version of the sexual identity question for several measures, including 16% of male measures (household size, past-year cigarette use, and past-year illicit drug use) and 15% of female measures (wanting a/another child, ever had a sexually transmitted disease, and past-year marijuana use). The absence of a “something else” response option for questions about sexual identity in national health surveys may cause respondents to select options that do not accurately describe their identities, and this can have a significant effect on national estimates of differences between sexual identity subgroups in terms of selected health outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

A large body of research has presented evidence of significant differences in the prevalence of adverse health outcomes among subgroups of individuals defined by sexual identity (NASEM, 2020). Individuals who identify as sexual minorities (e.g., lesbian, gay, bisexual) have repeatedly been shown to be at higher risk of substance use disorders (Boyd et al., 2019; Klare et al., 2021; McCabe et al., 2009), psychopathology (e.g., mood disorders) (Bostwick et al., 2010; Denney et al., 2021; Garbarski, 2021), suicidality (Denney et al., 2021; Haney, 2021), and risky sexual behaviors (Charlton et al., 2021; Gurnik et al., 2023; Macapagal et al., 2021). Sexual minorities have also been shown to be at higher risk of discrimination (Casey et al., 2019; Denney et al., 2021; McCabe et al., 2010). Substance misuse is the leading cause of preventable disease and death in the U.S., and sexual minorities are at higher risk for substance-related health consequences (Cochran et al., 2013; HHS, 2020a, b; Veliz et al., 2019). Potential variance in the magnitude of these differences across the lifespan has also been examined (McCabe et al., 2018), suggesting that the significance of this public health problem may vary by age. This growing body of research has led to the implementation of public health policies designed to understand and reduce these differences among sexual identity subgroups at the local, state, and national levels (NASEM, 2020; Tran et al., 2019).

Much of this research has utilized secondary analyses of large national survey data sets that collect measures of both sexual identity and various health outcomes, including the National Survey of Family Growth (NSFG), the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC), and the National Survey of Drug Use and Health (NSDUH). The validity of the estimated differences reported in these studies relies heavily on high-quality measurement of sexual identity, which is critical for the translation of these findings into effective public health policies and programs. Unfortunately, Table 1 below indicates substantial variability across numerous major national health and social surveys in terms of how sexual identity is measured. The effects of these different measurement approaches on population estimates of differences in various health and family formation outcomes among subgroups defined by sexual identity have largely been unexplored to date.

The survey methodology field is well-aware of this critical measurement issue (Eliason et al., 2016; FSCM, 2016a; Ridolfo et al., 2012). An entire 2019 issue of the Journal of Official Statistics was dedicated to research on the survey measurement of sexual identity (Volume 35, Issue 4: Special Issue on Measuring LGBT Populations). The Federal Committee on Statistical Methodology recently established an inter-agency interest group dedicated to research on the measurement of sexual orientation and gender identity (https://nces.ed.gov/FCSM/interagency_reports.asp). Based in part on the work of this interest group, the Office of the Chief Statistician of the United States recently released a report providing recommended best practices for collecting sexual orientation and gender identity data in Federal surveys (Office of the Chief Statistician of the United States, 2023). The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM) also recently released a report describing an extensive inter-agency study of best practices for measuring sexual orientation and gender identity (NASEM, 2022). Unfortunately, many of the national surveys used to generate this influential body of research on health differences related to sexual identity were fielded prior to these more recent attempts to establish best practices. These surveys generally collected relatively simple closed-ended measures about sexual identity that required respondents to choose from a limited number of response options (i.e., straight, lesbian/gay, or bisexual, with no other choices provided) (FCSM, 2016b).

Using sexual identity questions with limited response options introduces a risk of survey respondents being misclassified in terms of their sexual identity, especially if respondents do not perceive that the options provided apply to them (Dragan & Folkierska-Żukowska, 2022; see also the discussion in Everett, 2013). The minority stress model (Meyer, 2003, 2015) is one theoretical model proposing that members of sexual minority subgroups experience greater stigma and stressors than do heterosexual individuals. In response to this stress, sexual minority individuals may not outwardly identify as a member of a sexual minority subgroup, instead choosing a less stigmatizing option like heterosexual or “something else”. This misclassification may be heightened in racial/ethnic minority groups, those with high levels of internalized homophobia, or those living in less accepting environments (Amola & Grimmett, 2015; Denison et al., 2021; McConnell et al., 2018).

The statistical literature has clearly established that this type of misclassification in the measures on a categorical variable (like sexual identity) will attenuate estimated associations between that categorical variable and other measures (West & McCabe, 2021). Thus, national estimates of health disparities among sexual identity subgroups may be understated and/or misleading, and recent work has confirmed this possibility (West & McCabe, 2021). This survey measurement issue therefore has critical implications for evidence-based public health policies and practices.

In the current study, we present secondary analyses of data collected from a split-sample experiment embedded in five years of the NSFG (2015–2019), extending preliminary work examining this issue (West & McCabe, 2021). We focus on a variety of health outcomes, including reproductive health and related attitudes, and examine whether the same patterns of attenuated differences between sexual identity subgroups reported in previous work on substance use emerge for these additional health measures (West & McCabe, 2021). Based on this prior work and the theoretical mechanisms outlined above, we hypothesize that estimated differences between the sexual identity subgroups in terms of these additional health measures will be attenuated when using a smaller number of response options for sexual identity. With this work, we hope to motivate the continued development and use of improved measures of sexual identity for studies aiming to compare health outcomes among sexual identity subgroups.

Method

National Survey of Family Growth Overview

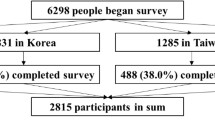

The NSFG collects fertility and family formation data in 60–80 min in-person interviews conducted with a national area probability sample of individuals aged 15 to 49. The NSFG sample design features stratified multistage cluster sampling of households and age-eligible individuals within households (Lepkowski et al., 2013). The NSFG data collection is continuous, with national probability samples released every quarter. We analyzed public-use NSFG data collected from a national probability sample of more than 21,441 U.S. males and females between 2015 and 2019. For additional details about the design of the NSFG, including response rates from these years (which generally averaged 70%), see the technical reports for these data prepared by the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS, 2018; NCHS 2020).

Sexual Identity Experiment

Between the years of 2015 and 2019, the NSFG implemented a unique split-sample experiment related to the measurement of sexual identity during data collection (the experiment was not implemented in any other years). Half of the 2015–2019 NSFG sample (here forth labelled TG1) was randomly assigned to receive one version of the sexual identity question during audio computer-assisted self-interviewing (ACASI), and half of the sample was randomly assigned to receive the other version (HHS, 2018; NSFG, 2021). The first “three-category” version (TG1) was unchanged from previous NSFG years: “Do you think of yourself as…heterosexual or straight (1), homosexual or gay/lesbian (2), or bisexual (3)?” The second “four-category” version (here forth labelled TG2) was drawn from the PhenX Toolkit: “Which of the following best represents how you think of yourself? Lesbian/gay (1), straight, that is, not lesbian/gay (2), bisexual (3), or something else (4)?” Item non-response rates for these two sexual identity questions were small (1.5% of women and 1.0% of men for TG1, and 1.0% of women and 0.8% of men for TG2) and did not vary significantly between the half-samples (West & McCabe, 2021).

In theory, adding the fourth response option of “Something Else” helps to improve the measurement of sexual identity. A recent NASEM report (2020) called for “…methodological research to develop, improve, and expand measures that capture the full range of sexual and gender diversity in the population—including but not limited to intersex status and emerging sexual and gender identities…” Write-in options for “something else” that would enable more evaluation of these emerging sexual identities were not collected for TG2, so we cannot qualitatively examine the responses of these individuals.

While the wording of these two questions in TG1 and TG2 was quite similar, the TG2 version (Dahlhamer et al., 2014) did not use the terms “heterosexual” or “homosexual” in the response options because some respondents find these terms confusing (Ridolfo et al., 2012). We also note that the ordering of the responses varied in the two questions. Response-order effects are generally more prominent in telephone surveys, where respondents cannot see the survey questions and response options (Holbrook et al., 2003). Self-administration of these types of sensitive questions does not introduce substantial effects of response ordering (Bishop et al., 1988; Sykes and Collins, 1988). Primacy effects previously reported for “speeders” and respondents with lower education in web surveys with no interviewer present would also likely be mitigated by the interviewer presence during ACASI in the NSFG (Galesic et al., 2008; Malhotra, 2008). We therefore have no theoretical reason to expect that the different ordering of the response options in the two versions of this question would affect our analyses.

Finally, the TG2 version also contains the qualifier “that is, not lesbian/gay” in the “Straight” category. Ridolfo and colleagues (2012) noted that this is important, as it allows respondents to identify with “not-me identities,” constructed through a process of dis-identification with an often-stigmatized group. This subtle difference may have resulted in slightly different populations identifying with the “Straight” category across TG1 and TG2; we will examine this possibility as part of our analytic approach.

Survey Measures

We computed estimates of sexual identity subgroup differences in the distributions of selected measures that met the following criteria:

-

(1)

They are of high scientific interest to researchers studying reproductive health and family formation (see https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nsfg/nsfg_products.htm) and

-

(2)

They have been the focus of prior studies where sexual identity and possibly interactions involving sexual identity were predictors of the measure (see the studies cited in the list of measures below).

These measures (with possible values in parentheses) included:

-

(1)

Current marital status (married vs. not married), along with number of times married (0, 1, 2,…; Kerridge et al., 2017);

-

(2)

Family formation, including household size (1, 2, 3, …) and an indicator of currently living with at least one child under the age of 18 (yes/no; Weber, 2008);

-

(3)

Current pregnancy status (yes/no; Charlton et al., 2020; Everett et al., 2017, 2019a);

-

(4)

Current use of various types of contraceptives (e.g., condoms; yes/no, for each type; Charlton et al., 2013, 2019);

-

(5)

Current sexual activity without contraceptive use (yes/no, for those sexually active; Charlton et al., 2013, 2019);

-

(6)

Intention to have children in the future (yes/no; Shenkman & Abramovitch, 2021);

-

(7)

Measures of current substance use, including past-month binge drinking; past-year cigarette smoking, including at the rate of a pack-per-day; marijuana use; and other illicit drug use (e.g., cocaine, crack, and crystal meth) (yes/no; Boyd et al., 2019; Drabble et al., 2021; Klare et al., 2021);

-

(8)

Risky sexual behaviors, including number of current sex partners (0, 1, 2,…) and anal sex (ever/never; Parmenter et al., 2020; Ueda et al., 2020); and

-

(9)

Measures of sexual health, including sexually transmitted diseases (ever had an STD/never had an STD, and past-year STD (yes/no); Gurnik et al., 2023; Everett et al., 2019a, 2019b).

Additional covariates considered included age in years, race (white, black, other), education (less than high school (HS), HS, greater than HS), and total family income ($0–$19,999, $20K–$34,999, $35K-$69,999, $70K+). As the concept of “straight” does not resonate culturally with Spanish speakers (Ridolfo et al., 2012), we also analyzed an indicator of Hispanic ethnicity (yes, no).

Statistical Analysis

We used the NSFG survey weights to compute design-unbiased estimates of population parameters and account for the complex sampling features of the NSFG when estimating standard errors and testing hypotheses. All bivariate tests of associations between sexual identity and categorical health measures employ design-adjusted Rao-Scott tests. We used multivariable models to compute adjusted estimates of subgroup differences in the distributions of the health outcomes; we fit both linear and logistic regression models using the pseudo-maximum likelihood estimation method for complex samples, and use design-adjusted subpopulation analyses and goodness of fit assessments (e.g., area under the ROC curve, or AUC) when appropriate (Heeringa et al., 2017). All analyses are stratified by sex, given evidence of larger increases in the risk of adverse health outcomes for sexual minority women (Boyd et al., 2019; McCabe et al., 2005). All analyses use Stata (version 17) commands for the analysis of complex sample survey data.

We first performed descriptive comparisons of the weighted percentages and means for the various health outcomes for each sexual identity subgroup defined by the two NSFG treatment groups. This enabled comparisons of the estimated associations between sexual identity and the various outcome measures across the two samples, via the Rao-Scott tests and design-adjusted Wald tests (for the means). Next, we fit linear and logistic regression models to predict the various continuous and binary health outcomes with the different measures of sexual identity and the covariates. We formally compared the sexual identity subgroup differences between the two NSFG treatment groups by testing two-way interactions between sexual identity and the treatment group indicator. In the comparative analyses, we dropped respondents indicating “something else” in NSFG TG2, enabling comparisons across the treatment groups of estimated differences in the health outcomes between the more commonly endorsed sexual identities (straight or heterosexual, gay (for males) or lesbian (for females), and bisexual).

Following recommendations from Rothman (1990) and Gardner and Altman (1986), we focused primarily on effect sizes associated with the two-way interactions of interest in these models (and their confidence intervals). We examined the estimated interaction coefficients in these models, along with their design-adjusted 95% confidence intervals, in addition to design-adjusted Wald tests for each two-way interaction, using a 0.05 level of significance, and used these criteria to identify outcomes where there was evidence of substantial (i.e., nonzero) moderation of the subgroup differences based on the measurement approach. For these outcomes, we computed estimates of odds ratios quantifying differences between the sexual identity subgroups (and their 95% confidence intervals) based on the estimated coefficients in the models. We then used the margins and marginsplot post-estimation commands in Stata to compute and visualize marginal predictions of the subgroup differences for each measurement approach (adjusting for the covariates in the models), along with design-adjusted 95% confidence intervals for the differences. This approach enabled visualization of any estimated subgroup differences that varied substantially depending on the measurement approach.

Given rates of item-missing data on the measures of interest that varied between 0.2 and 2.3% (for females) and 0.5 and 2.9% (for males), the sample sizes used to fit the multivariable models varied depending on the measure. We also performed a sensitivity analysis and repeated all analyses described above after conducting a multiple imputation analysis. We generated multiple (10) imputations of each missing value using a chained equations approach (Raghunathan et al., 2001), where we first imputed modal values for measures with less than 100 missing values, and then employed chained equations depending on the type of each measure. We imputed the four possible categories of sexual identity for both treatment groups. We recoded imputed values of “something else” in TG1 by first generating a random draw from a Uniform(0,1) distribution, and imputing one of the three response categories for TG1 by referring the random draw to the marginal distribution of sexual identity for TG1 based on complete cases (i.e., if the random draw was between 0 and 0.883 for females, per Table 2, the “something else” respondent was imputed to be heterosexual, and if the random draw was between 0.884 and 0.910, they were imputed to be lesbian). Estimates and their standard errors based on each imputed data set were combined using the combining rules described in Little and Rubin (2019).

Results

Estimated Sexual Identity Distributions

Table 2 below presents unweighted sample sizes and weighted estimates of the sexual identity distributions by sex based on the two sample subgroups (TG1 and TG2) in the 2015–2019 NSFG data (using the final NSFG survey weights).

In Table 2, we note that at least 100 women and men responded with the “something else” option when given the chance, meaning that this sexual identity subgroup represents a non-negligible 2–4% of the larger target population. Relative to the distributions based on TG1, we see that offering the “something else” option reduces the estimated percentages of both men and women who identify as heterosexual/straight, and of women who identify as lesbian or bisexual.

Comparisons of Associations

Table 3 presents the estimated bivariate associations between sexual identity and selected health outcomes for males, along with the design-adjusted Rao-Scott or Wald tests of the associations, separately for TG1 and TG2.Footnote 1

In Table 3, the reported tests of associations considered the largest three categories of sexual identity (heterosexual/straight, gay, and bisexual) to see if estimated differences between these categories would be sensitive to the inclusion of the “something else” response option in TG2. Consider the three outcomes measuring past-year cigarette use, past-year other drug use, and wanting a/another child. We see that males who identify as “something else” if given the option (TG2) tend to have a higher prevalence of each of these outcomes, and that estimates of differences between individuals who identify as heterosexual and gay or bisexual tend to change depending in the measurement approach. This is particularly true for other drug use and wanting a/another child, where the Rao-Scott tests are completely different; this is also the case for mean household size. Based on the sample that was only provided with three sexual identity options (TG1), the estimated prevalence of the three binary outcomes for the gay and bisexual subgroups tends to be larger, where presumably the individuals identifying as “something else” in TG2 (who tend to be more likely to endorse each of these outcomes) are forced to choose between the three options provided.

For example, consider other drug use in the past year. When using the four-category measure of sexual identity, the estimated prevalence is 13.8% among those responding with “something else”, compared to only 6.8% for those responding as gay. Table A8 in the online Appendix shows that the “something else” subgroup continues to have a marginally higher prevalence of substance use than the other three groups in a multivariable analysis. The resulting difference in prevalence between gay and bisexual males is very small, and the Rao-Scott test of association (p = .9) does not suggest any association of sexual identity with this outcome. However, when considering the estimates based on the three-category measure, we see much larger estimates of differences in prevalence between gay or bisexual males and heterosexual males (p < .001); notably, the estimated prevalence for heterosexual males remains quite similar regardless of the measure of sexual identity used. Respondents who might have indicated “something else” if provided with this option may have selected either gay or bisexual instead, increasing those estimated prevalence rates.

When following our multivariable modeling approach to determine which of these changes in associations remained large in magnitude after adjusting for relevant covariates, we identified three outcomes where the models had non-zero two-way interactions between sexual identity and the measurement approach (TG1 vs. TG2), with a design-adjusted Wald test p value less than .05 and corresponding interaction coefficients with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) that did not include zero. These included past-year cigarette use, past-year other drug use, and household size. See Table A4 in the online Appendix for the estimated coefficients, 95% CIs, and corresponding design-adjusted Wald tests. Notably, there was no longer evidence of a two-way interaction for wanting a/another child when adjusting for the covariates. This may have been due to shifts in socio-demographic measures related to this outcome that were also engendered by the different measurement approaches; see Table A3a in the online Appendix.

Based on the model for past-year cigarette use, the 95% CIs for the odds ratios comparing gay and bisexual individuals to heterosexual individuals in TG1 both included one, suggesting negligible differences based on TG1. Based on TG2, the estimated odds ratio comparing bisexual individuals to heterosexual individuals was 0.42 (95% CI = 0.22, 0.83), suggesting a non-zero 58% reduction in the odds of past-year cigarette use for bisexuals relative to heterosexuals; the 95% CI for the gay vs. heterosexual odds ratio continued to include 1. Consistent with Table 3, we would arrive at a completely different conclusion about the bisexual vs. heterosexual difference in this behavior depending on the measurement approach.

Based on the model for past-year other drug use, the estimated odds ratios for gay vs. heterosexual (OR = 2.23, 95% CI = 1.03, 4.81) and bisexual vs. heterosexual (OR = 3.56, 95% CI = 1.84, 6.90) in TG1 both had 95% CIs that did not include one, suggesting non-zero differences with increased drug use for sexual minorities (consistent with Table 3). In contrast, the 95% CIs both included one for TG2, suggesting negligible differences. We would again arrive at completely different conclusions about these differences after adjusting for the covariates, depending on the measurement approach. Based on the model for household size, gay and bisexual individuals were both estimated to have substantially lower mean household sizes than heterosexual respondents (estimated coefficients = − 0.75 and − 0.56, with 95% CIs of (− 1.07, − 0.43) and (− 0.83, − 0.29), respectively) in TG1 (again consistent with Table 3). In TG2, these differences disappeared, with both 95% CIs for the differences including zero.

Based on these modeling results, Fig. 1 displays estimates of the marginal differences between gay and heterosexual individuals (first column) and between bisexual and heterosexual individuals (second column) in terms of these outcomes (adjusting for the covariates in the models), along with 95% CIs for the marginal differences. Figure 1 provides a clear visualization of these estimated differences depending on the measurement approach, where in one case a 95% CI for the difference may include zero, and in a second case it does not.

Estimates of marginal differences between gay and heterosexual males (first column) and bisexual and heterosexual males (second column) in the probabilities or means of selected outcomes by measurement approach (TG1 = three categories of sexual identity, TG2 = four categories of sexual identity), including 95% CIs for the marginal differences, based on estimated multivariable models (PYCIG = past-year cigarette use; PYILLICIT = past-year other drug use; HH Size = household size)

Table 4 presents the estimated bivariate associations between sexual identity and selected health outcomes for females, along with the design-adjusted Rao-Scott or Wald tests of the associations, separately for TG1 and TG2.

In Table 4, consider the four outcomes measuring past-year pack-a-day smoker, past-year marijuana use, wanting a/another child, and ever had an STD. The estimates suggest that females provided with the “something else” response option for sexual identity (TG2) tend to have lower prevalence of these four outcomes, relative to those identifying as lesbian or bisexual when given the four possible options. Table A9 in the online Appendix shows that some of these differences (e.g., past-year marijuana use) remain robust in multivariable models fitted to the TG2 data. Accordingly, we see reductions in the prevalence estimates for lesbian and bisexual respondents based on the sample given the three-category version of sexual identity, where respondents are forced to choose from one of the three identities. In some cases (past-year pack-a-day smoker, wanting a/another child), this leads to non-significant associations in TG1, relative to significant associations in TG2. In others, a non-significant association in TG2 becomes significant in TG1 (ever had an STD). In the case of past-year marijuana use, we see evidence of a larger bisexual-lesbian difference in TG2.

Consider the indicator of wanting a/another child for females. With the four-category measure of sexual identity, there is evidence of a larger difference between bisexual women and heterosexual women, with an estimated 68.1% of bisexual women wanting a/another child (compared to only 50.7% of heterosexual women). This produces a significant Rao-Scott test of association (p < .001), suggesting significant differences in the prevalence of this outcome between subgroups defined by sexual identity. The estimated prevalence for a female identifying as “something else” is only 49.3%, and Table A9 in the online Appendix suggests that this subgroup has a marginally lower prevalence than the other three groups when adjusting for other covariates. When we consider the estimates based on the sample assigned to the three-category measure of sexual identity, the estimated prevalence drops for both lesbian and bisexual respondents (especially so for bisexual respondents), to the point where there is no longer evidence of a significant association between sexual identity and “wantedness” (p = .142).

When following our multivariable modeling approach to determine which of these changes in associations remained large in magnitude after adjusting for relevant covariates, we identified three outcomes where the models had non-zero two-way interactions between sexual identity and the measurement approach (TG1 vs. TG2). These included past-year marijuana use, wanting a/another child, and ever had an STD. See Table A6 in the online Appendix for the estimated coefficients, 95% CIs, and corresponding design-adjusted Wald tests. Based on the model for past-year marijuana use, the 95% CIs for the odds ratios comparing lesbian and bisexual individuals to heterosexual individuals in TG1 both did not include 1, suggesting large differences based on TG1 (odds ratios of 2.3 (95% CI = 1.5, 3.4) and 2.5 (95% CI = 1.9, 3.5), respectively). Based on TG2, the estimated odds ratio comparing bisexual individuals to heterosexual individuals was 4.5 (95% CI = 3.2, 6.4), suggesting a much larger adjusted difference between heterosexuals and bisexuals when using the four-category measure of sexual identity (consistent with Table 4).

Based on the model for wanting a/another child, the estimated odds ratios for lesbian and bisexual individuals versus heterosexual individuals were both less than 1, with 95% CIs that did not include 1 (OR = 0.3 (95% CI = 0.2, 0.6) and OR = 0.5 (95% CI = 0.3, 0.7), respectively), suggesting reductions in the odds of wanting a/another child for sexual minority females relative to heterosexual females (consistent with the lesbian vs. heterosexual difference in Table 4, but different for bisexuals after adjustment for covariates). In contrast, the 95% CIs both included one for TG2, suggesting negligible differences. We would again arrive at completely different conclusions about these differences after adjusting for the covariates, depending on the measurement approach; the estimates of the adjusted differences shrink and become positive when using the four-category measure of sexual identity.

Based on the multivariable model for ever had an STD, the estimated odds of ever having had an STD are about 70% lower for lesbian women relative to heterosexual women (OR = 0.3, 95% CI = 0.2, 0.6), adjusting for the covariates, while the estimated odds are about 40% higher for bisexual women relative to heterosexual women (OR = 1.4, 95% CI = 1.0, 2.0). In TG2, the estimated lesbian-heterosexual difference disappears (OR = 1.4, 95% CI = 0.4, 4.6), and the bisexual-heterosexual difference remained large, even increasing (OR = 2.0, 95% CI = 1.3, 3.0). We would reach a different conclusion about the adjusted lesbian-heterosexual difference depending on the measurement approach.

Given these modeling results, Fig. 2 displays estimates of the marginal differences between lesbian and heterosexual individuals (first column) and between bisexual and heterosexual individuals (second column) in terms of these three outcomes (adjusting for the covariates in the models), along with 95% CIs for the marginal differences. Figure 2 provides another clear visualization of these estimated differences depending on the measurement approach, where again in one case a 95% CI for the difference may include zero, and in a second case it does not.

Estimates of marginal differences between lesbian and heterosexual females (first column) and bisexual and heterosexual females (second column) in the probabilities of selected outcomes by measurement approach (TG1 = three categories of sexual identity, TG2 = four categories of sexual identity), including 95% CIs for the marginal differences, based on estimated multivariable models (PYMJ = past-year marijuana use; Life STD = ever had an STD; Want = want a/another child)

In none of our comparative or multivariable analyses did our primary conclusions change when conducting the multiple imputation analysis. None of the significance levels in any of the Rao-Scott tests changed in any meaningful fashion, and we found the same evidence of meaningful interactions in the multivariable models. No new two-way interactions with non-zero coefficients emerged in the multiple imputation analysis.

Discussion

Summary of Results

First, among males, we would arrive at different conclusions regarding sexual identity subgroup differences for 3 out of the 19 health outcomes considered (16% of the measures). While many of the measures may not be affected, there could be important policy implications when making conclusions about these populations based on the three measures that were affected (illicit drug use, household size, and cigarette smoking). Comparing bisexual males to heterosexual males, the three-category measure produced a meaningful positive difference for other illicit drug use that disappeared when using four categories, largely because the “something else” respondents had a higher prevalence on this measure, eliminating the large positive difference between heterosexual and bisexual individuals in the three-category version. The four-category measure produced a meaningful negative difference between bisexual and heterosexual males for past-year cigarette use, again because the high prevalence for “something else” respondents appeared to increase the prevalence for bisexual respondents in the three-category version, in this case eliminating the large difference between the three groups that we observed when using the four-category measure. For household size, both gay and bisexual men had lower means when using the three-category version of the measure, and these differences disappeared when using the four-category measure.

Among females, we would arrive at different conclusions regarding sexual identity subgroup differences for 3 out of 20 health outcomes (15% of the measures: wanting a/another child, ever had an STD, and past-year marijuana use). Meaningful negative differences between both lesbian and bisexual women and heterosexual women in the probability of wanting a/another child when using the three-category version of sexual identity disappeared when using the four-category version, in this case because “something else” individuals had a lower prevalence of this outcome that appeared to reduce the prevalence for lesbian and bisexual women when using the three-category measure. In terms of ever having had an STD, a large negative difference between lesbian women and heterosexual women in the three-category version disappeared when using the four-category version, while a negligible difference between bisexual women and heterosexual women because a large positive difference in the four-category version. This all may have been due to lower prevalence of this outcome among women identifying as “something else”. Finally, while large positive differences were found between both lesbian and bisexual women and heterosexual women in terms of past-year marijuana use when using both versions of the sexual identity measure, the difference between bisexual and heterosexual women was found to become substantially larger when using the four-category version (again possibly due to lower prevalence of this outcome among women identifying as “something else”).

These results suggest key sex differences in the studied behaviors among members of the “something else” group (TG2) that was administered the four-category sexual identity measure. In males, these individuals had relatively high rates of not just illicit drug use and cigarette use, but also binge alcohol use. In contrast, the “something else” group of females had lower rates of substance use that were often like those of heterosexual females. At least one longitudinal study has shown that males who reported sexual identity as “something else” had lower odds of cigarette (re)uptake than heterosexual males; this association was not mediated by internalizing and externalizing symptoms (Evans-Polce et al., 2022). Research in Australian sexual minority adults (McLaren, 2015) suggests that internalized homonegativity has stronger links to depressive symptoms in men than women, and men who identify as “something else” to ameliorate minority stress and internalized homonegativity may be a higher risk group. In women, however, lesser identification with the sexual minority group or openness about one’s sexual identity has been linked to better mental health (Kuyper & Fokkema, 2011; McLaren et al., 2013), which may partially explain why this group has lower rates of substance use and warrants additional attention.

Implications for Research and Practice

This study has broad implications for other secondary analyses of existing public health data, given the other major national studies that have measured sexual identity using a small number of categories (Table 1). Considering the results of this study, we do not find that inferences about the associations between sexual identity and all health outcomes are affected by how sexual identity is measured. However, a non-trivial number of estimated associations are indeed impacted by this problem, meaning that policy and programming decisions based on surveys that only offer a small number of response options for sexual identity should be considered carefully (and ideally, associations should be replicated using an independent data source providing more possible options for this construct).

Our hope is that the new federal guidelines mentioned in the Introduction will yield improved measures of sexual identity in all future national health surveys. We would endorse the best practices summarized in the NASEM report described in the Introduction (NASEM, 2022), which includes open-ended measures for those who would describe themselves as “something else”; careful qualitative analysis of such responses would make attenuated or potentially biased estimates of associations less likely. Indeed, a recent qualitative study of sexual and gender minority individuals suggested that current measures are not as clear as they should be and do not allow for sufficient fluidity and complexity in terms of the construct of sexual orientation identity (Suen et al., 2020).

Future Research Directions

We did not repeat these analyses for different socio-demographic subgroups of males and females (e.g., race/ethnicity). Future work in this area could investigate whether these changes in associations tend to disproportionately affect socio-demographic subgroups of either sex. The experimental design used in the NSFG also did not allow us to answer the question of how people would respond when asked both types of sexual identity questions. In other words, how do the “something else” respondents for each sex tend to answer when forced to choose between a smaller number of categories? Future experiments could examine this further; for instance, one prior study found that people may consider themselves as “mostly” belonging to a particular identity, and these identities could easily change depending on the response options provided (McCabe et al., 2012).

For example, it is possible that some people who would consider themselves “mostly heterosexual”, representing a unique but understudied sexual identity population that has elevated risk of substance use/mental health outcomes (Hughes et al., 2010, 2015; McCabe et al., 2005, 2012; Talley et al., 2016), would respond as heterosexual when only given three sexual identity options but as “something else” when given four options, affecting estimated differences in rates of substance use. We did see reductions in the estimated percentages of the target population identifying as heterosexual when the “something else” option was added (Table 2), which could have also affected the subgroup differences reported in this study. Tables A3a and A3b in the online Appendix present estimated socio-demographic distributions for each of the three largest sexual identity subpopulations (separately for males and females) based on the two measurement approaches and suggest that changes in Hispanic ethnicity and socio-economic status for gay/lesbian and bisexual individuals may be introduced when using the four-category measure of sexual identity (especially for males). How estimated differences in terms of family formation, rather than substance use, might be affected remains unclear and is worthy of future research. Our results suggest that males choosing the “something else” category tend to have a higher prevalence of substance use and average household sizes, while females choosing the “something else” category have less desire to have a/additional children (see Shenkman & Abramovitch, 2021), lower rates of STDs (see Gurnik et al., 2023 and Everett et al., 2019a, 2019b), and reduced odds of past-year marijuana use.

Other recent work has suggested that same-sex male couples may not provide reliable reports of sexual behavior, and this type of measurement error in sexual activity may affect time-varying reports of sexual identity if activity is considered when reporting identity (Walsh & Stephenson, 2021). Future studies could measure sexual identity in different ways for the same individuals over time and collect additional qualitative data to understand important contextual factors that influence these reports of identity, especially considering recent evidence from national longitudinal data showing significant associations between substance use and sexual identify fluidity/stability (Evans-Polce et al., 2023a, 2023b). This would also enable assessment of comprehension difficulties with the terms “homosexual” and “heterosexual” (Ridolfo et al., 2012), and how individuals identifying as one of these categories respond when different approaches are used to measure sexual identity in the future (e.g., “Straight, that is, not gay or lesbian”).

Availability of Data and Material

All data analyzed are available in the public domain at the respective NSFG (https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nsfg/) and NSDUH (https://www.samhsa.gov/data/data-we-collect/nsduh-national-survey-drug-use-and-health) websites.

Code Availability

All of the code used to perform the data management and analyses presented in this manuscript is available in the following GitHub repository: https://github.com/bradytwest/sexident.

Notes

We note that similar associations were found when conducting analyses of associations between the same three-category measure of sexual identity and common substance use outcomes in the 2015-2019 NSDUH data (for both males and females; SAMHSA, 2018a, 2018b, 2018c, 2019, 2020). This supports the idea that similar conclusions would arise when using the same three-category measure of sexual identity in different national surveys of the same target population, and the NSDUH is considered a gold-standard national survey of substance use. Please see Tables A1 and A2 in the online Appendix for details.

References

Amola, O., & Grimmett, M. A. (2015). Sexual identity, mental health, HIV risk behaviors, and internalized homophobia among Black men who have sex with men. Journal of Counseling and Development, 93, 236–246. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6676.2015.00199.x

Bishop, G. E., Hippler, H.-J., Schwarz, N., & Strack, F. (1988). A comparison of response effects in self-administered and telephone surveys. In R. M. Groves, P. P. Biemer, L. E. Lyberg, J. T. Massey, W. L. Nicholls, & J. Waksberg (Eds.), Telephone survey methodology (pp. 321–340). Wiley.

Bostwick, W. B., Boyd, C. J., Hughes, T. L., & McCabe, S. E. (2010). Dimensions of sexual orientation and the prevalence of mood and anxiety disorders in the United States. American Journal of Public Health, 100(3), 468–475. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2008.152942

Boyd, C. J., Veliz, P. T., Stephenson, R., Hughes, T. L., & McCabe, S. E. (2019). Severity of alcohol, tobacco, and drug use disorders among sexual minority individuals and their “not sure” counterparts. LGBT Health, 6(1), 15–22. https://doi.org/10.1089/lgbt.2018.0122

Casey, L. S., Reisner, S. L., Findling, M. G., Blendon, R. J., Benson, J. M., Sayde, J. M., & Miller, C. (2019). Discrimination in the United States: Experiences of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer Americans. Health Services Research, 54(Suppl 2), 1454–1466. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6773.13229

Charlton, B. M., Corliss, H. L., Missmer, S. A., Rosario, M., Spiegelman, D., & Austin, S. B. (2013). Sexual orientation differences in teen pregnancy and hormonal contraceptive use: An examination across 2 generations. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 209(3), 204.e1-204.e8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2013.06.036

Charlton, B. M., Everett, B. G., Light, A., Jones, R. K., Janiak, E., Gaskins, A. J., Chavarro, J. E., Moseson, H., Sarda, V., & Austin, S. B. (2020). Sexual orientation differences in pregnancy and abortion across the lifecourse. Women’s Health Issues, 30(2), 65–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.whi.2019.10.007

Charlton, B. M., Janiak, E., Gaskins, A. J., DiVasta, A. D., Jones, R. K., Missmer, S. A., Chavarro, J. E., Sarda, V., Rosario, M., & Austin, S. B. (2019). Contraceptive use by women across different sexual orientation groups. Contraception, 100(3), 202–208. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.contraception.2019.05.002

Charlton, B. M., Reynolds, C. A., Janiak, E., DiVasta, A. D., Jones, R. K., Chavarro, J. E., Sarda, V., & Austin, S. B. (2021). Sexual orientation-related differences in contraceptive use: A brief report based on a cohort of adolescent and young women. Contraception, 103(3), 195–198. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.contraception.2020.11.002

Cochran, S. D., Bandiera, F. C., & Mays, V. M. (2013). Sexual orientation–related differences in tobacco use and secondhand smoke exposure among us adults aged 20 to 59 years: 2003–2010 national health and nutrition examination surveys. American Journal of Public Health, 103(10), 1837–1844. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2013.301423

Dahlhamer, J. M., Galinsky, A. M., Joestl, S. S., & Ward, B. W. (2014). Sexual orientation in the 2013 national health interview survey: A quality assessment. Vital and Health Statistics. Series 2 Data Evaluation and Methods Research, 169, 1–32.

Denney, J. T., Zhang, Z., Gorman, B. K., & Cooley, C. (2021). Substance use, mental well-being, and suicide ideation by sexual orientation among US adults. In A. J. LeBlanc & B. L. Perry (Eds.), Advances in medical sociology (pp. 39–63). Emerald Publishing Limited. https://doi.org/10.1108/S1057-629020210000021008

Denison, E., Jeanes, R., Faulkner, N., et al. (2021). The relationship between ‘Coming Out’ as lesbian, gay, or bisexual and experiences of homophobic behaviour in youth team sports. Sexuality Research and Social Policy, 18, 765–773. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13178-020-00499-x

Drabble, L. A., Mericle, A. A., Gómez, W., Klinger, J. L., Trocki, K. F., & Karriker-Jaffe, K. J. (2021). Differential effects of state policy environments on substance use by sexual identity: Findings from the 2000–2015 national alcohol surveys. Annals of LGBTQ Public and Population Health, 2(1), 53–71. https://doi.org/10.1891/LGBTQ-2020-0029

Dragan, W. Ł, & Folkierska-Żukowska, M. (2022). The biodevelopment of sexual orientation: Beyond the known horizon [Commentary]. Archives of Sexual Behavior. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-022-02506-1

Eliason, M. J., Radix, A., McElroy, J. A., Garbers, S., & Haynes, S. G. (2016). The “something else” of sexual orientation: Measuring sexual identities of older lesbian and bisexual women using national health interview survey questions. Women’s Health Issues, 26, S71–S80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.whi.2016.03.012

Evans-Polce, R. J., Schuler, M. S., Kcomt, L., McCabe, V. V., & McCabe, S. E. (2023a). Sexual identity differences in tobacco (re)uptake: Testing mediation by internalizing and externalizing symptoms. American Journal of Preventative Medicine, 64(6), 824–833. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2023.01.017

Evans-Polce, R. J., Veliz, P., Kcomt, L., Boyd, C. J., & McCabe, S. E. (2023b). Examining sexual identity stability and change over time and associations with tobacco use in a nationally representative US sample. Addictive Behaviors, 141. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2023.107661

Everett, B. G. (2013). Sexual orientation disparities in sexually transmitted infections: Examining the intersection between sexual identity and sexual behavior. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 42(2), 225–236. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-012-9902-1

Everett, B. G., Higgins, J. A., Haider, S., & Carpenter, E. (2019a). Do sexual minorities receive appropriate sexual and reproductive health care and counseling? Journal of Women’s Health, 28(1), 53–62. https://doi.org/10.1089/jwh.2017.6866

Everett, B. G., Kominiarek, M. A., Mollborn, S., Adkins, D. E., & Hughes, T. L. (2019b). Sexual orientation disparities in pregnancy and infant outcomes. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 23(1), 72–81. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-018-2595-x

Everett, B. G., McCabe, K. F., & Hughes, T. L. (2017). Sexual orientation disparities in mistimed and unwanted pregnancy among adult women. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health, 49(3), 157–165. https://doi.org/10.1363/psrh.12032

Federal Interagency Working Group on Improving Measurement of Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity in Federal Surveys (FCSM). (2016a). Current measures of sexual orientation and gender identity in federal surveys. Retrieved March 20, 2023, from https://nces.ed.gov/FCSM/pdf/buda5.pdf

Federal Interagency Working Group on Improving Measurement of Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity in Federal Surveys (FCSM). (2016b). Toward a research agenda for measuring sexual orientation and gender identity in federal surveys: Findings, recommendations, and next steps. Retrieved March 20, 2023, from https://nces.ed.gov/FCSM/pdf/SOGI_Research_Agenda_Final_Report_20161020.pdf

Galesic, M., Tourangeau, R., Couper, M. P., & Conrad, F. G. (2008). Eye-tracking data: New insights on response order effects and other cognitive shortcuts in survey responding. Public Opinion Quarterly, 72(5), 892–913. https://doi.org/10.1093/poq/nfn059

Garbarski, D. (2021). The survey measurement of sexual orientation: Configurations of sexual identity and attraction and associations with mental health. LGBT Health, 8(4), 307–315. https://doi.org/10.1089/lgbt.2020.0270

Gardner, M. J., & Altman, D. G. (1986). Confidence intervals rather than P values: Estimation rather than hypothesis testing. British Medical Journal, 292, 746. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.292.6522.746

Gurnik, H., Engstrom, C. W., McCabe, S. E., & Evans-Polce, R. J. (2023). Differences in HIV testing among sexual orientation subgroups in the United States: A national cross-sectional study. Preventative Medicine Reports, 74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmedr.2023.102230

Haney, J. L. (2021). Suicidality risk among adult sexual minorities: Results from a cross-sectional population-based survey. Journal of Gay and Lesbian Social Services, 33(2), 250–271. https://doi.org/10.1080/10538720.2021.1875946

Heeringa, S. G., West, B. T., & Berglund, P. A. (2017). Applied survey data analysis (2nd ed.). CRC Press, Taylor & Francis Group.

Holbrook, A. L., Green, M. C., & Krosnick, J. A. (2003). Telephone versus face-to-face interviewing of national probability samples with long questionnaires. Public Opinion Quarterly, 67(1), 79–125. https://doi.org/10.1086/346010

Hughes, T., Szalacha, L. A., & McNair, R. (2010). Substance abuse and mental health disparities: Comparisons across sexual identity groups in a national sample of young Australian women. Social Science Medicine, 71(4), 824–831. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.05.009

Hughes, T. L., Wilsnack, S. C., & Kristjanson, A. F. (2015). Substance use and related problems among U.S. women who identify as mostly heterosexual. BMC Public Health, 15. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-015-2143-1

Kerridge, B. T., Pickering, R. P., Saha, T. D., Ruan, W. J., Chou, S. P., Zhang, H., Jung, J., & Hasin, D. S. (2017). Prevalence, sociodemographic correlates and DSM-5 substance use disorders and other psychiatric disorders among sexual minorities in the United States. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 170, 82–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2016.10.038

Klare, D. L., McCabe, S. E., Ford, J. A., & Schepis, T. S. (2021). Prescription drug misuse, other substance use, and sexual identity: The significance of educational status and psychological distress in US young adults. Substance Abuse, 42(3), 377–387. https://doi.org/10.1080/08897077.2020.1784358

Kuyper, L., & Fokkema, T. (2011). Minority stress and mental health among Dutch LGBs: Examination of differences between sex and sexual orientation. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 58(2), 222–233. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0022688

Lepkowski, J. M., Mosher, W. D., Groves, R. M., West, B. T., Wagner, J., & Gu, H. (2013). Responsive design, weighting, and variance estimation in the 2006–2010 national survey of family growth. Vital and Health Statistics. Series 2. Data Evaluation and Methods Research, 158, 1–52.

Little, R. J., & Rubin, D. B. (2019). Statistical analysis with missing data (3rd ed.). Wiley.

Macapagal, K., Moran, K., Newcomb, M. E., Moskowitz, D. A., Owens, C., & Mustanski, B. (2021). Patterns of online and offline partnering, partnership characteristics, and condomless sex among adolescent sexual minority males in the USA. AIDS and Behavior, 25(7), 2033–2045. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-020-03133-4

Malhotra, N. (2008). Completion time and response order effects in web surveys. Public Opinion Quarterly, 72(5), 914–934. https://doi.org/10.1093/poq/nfn050

McCabe, S. E., Bostwick, W. B., Hughes, T. L., West, B. T., & Boyd, C. J. (2010). The relationship between discrimination and substance use disorders among lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults in the United States. American Journal of Public Health, 100(10), 1946–1952. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2009.163147

McCabe, S. E., Hughes, T. L., Bostwick, W., & Boyd, C. J. (2005). Assessment of difference in dimensions of sexual orientation: Implications for substance use research in a college-age population. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 66(5), 620–629. https://doi.org/10.15288/jsa.2005.66.620

McCabe, S. E., Hughes, T. L., Bostwick, W. B., Morales, M., & Boyd, C. J. (2012). Measurement of sexual identity in surveys: Implications for substance abuse research. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 41(3), 649–657. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-011-9768-7

McCabe, S. E., Hughes, T. L., Bostwick, W. B., West, B. T., & Boyd, C. J. (2009). Sexual orientation, substance use behaviors and substance dependence in the United States. Addiction, 104(8), 1333–1345. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02596.x

McCabe, S. E., Matthews, A. K., Lee, J. G. L., Veliz, P., Hughes, T. L., & Boyd, C. J. (2018). Tobacco use and sexual orientation in a national cross-sectional study: Age, race/ethnicity, and sexual identity–attraction differences. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 54(6), 736–745. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2018.03.009

McConnell, E. A., Janulis, P., Phillips, G., II., Truong, R., & Birkett, M. (2018). Multiple minority stress and LGBT community resilience among sexual minority men. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 5(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1037/sgd0000265

McLaren, S. (2015). Gender, age, and place of residence as moderators of the internalized homophobia-depressive symptoms relation among Australian gay men and lesbians. Journal of Homosexuality, 62(4), 463–480. https://doi.org/10.1080/00918369.2014.983376

McLaren, S., Gibbs, P. M., & Watts, E. (2013). The interrelations between age, sense of belonging, and depressive symptoms among Australian gay men and lesbians. Journal of Homosexuality, 60(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/00918369.2013.735933

Meyer, I. H. (2003). Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychological Bulletin, 129(5), 674–697. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674

Meyer, I. H. (2015). Resilience in the study of minority stress and health of sexual and gender minorities. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 2(3), 209–213. https://doi.org/10.1037/sgd0000132

National Academies and of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM). (2020). Understanding the well-being of LGBTQI+ populations. The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/25877

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM). (2022). Measuring sex, gender identity, and sexual orientation. The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/26424

National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS). (2018). 2015–2017 National Survey of Family Growth public-use data and documentation. Hyattsville, MD: CDC National Center for Health Statistics. Retrieved on November 3, 2022, from http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nsfg/nsfg_2015_2017_puf.htm

National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS). (2020). 2017–2019 National Survey of Family Growth public-use data and documentation. Hyattsville, MD: CDC National Center for Health Statistics. Retrieved on November 3, 2022, from http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nsfg/nsfg_2017_2019_puf.htm

National Survey of Family Growth (NSFG). (2021). Comparisons of sexual orientation distributions in 2015–2019 NSFG ACASI, based on NSFG and NHIS question wording. OMB Attachment D4, OMB No. 0920–0314. Retrieved on 7/14/23 from https://www.reginfo.gov/public/do/PRAViewDocument?ref_nbr=202211-0920-003

Office of the Chief Statistician of the United States (2023). Recommendations on the best practices for the collection of sexual orientation and gender identity data on federal statistical surveys. Office of Management and Budget (OMB). Retrieved on April 12, 2023, from https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/SOGI-Best-Practices.pdf

Parmenter, J. G., Crowell, K. A., & Galliher, R. V. (2020). Subjective importance of masculinity as a factor in understanding risky sexual attitudes and behaviors among sexual minority men. Sex Roles, 82(7–8), 463–472. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-019-01067-3

Raghunathan, T. E., Lepkowski, J. M., Van Hoewyk, J., & Solenberger, P. (2001). A multivariate technique for multiply imputing missing values using a sequence of regression models. Survey Methodology, 27(1), 85–96.

Ridolfo, H., Miller, K., & Maitland, A. (2012). Measuring sexual identity using survey questionnaires: How valid are our measures? Sexuality Research and Social Policy, 9(2), 113–124. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13178-011-0074-x

Rothman, K. J. (1990). No adjustments are needed for multiple comparisons. Epidemiology, 1(1), 43–46.

Shenkman, G., & Abramovitch, M. (2021). Estimated likelihood of parenthood and its association with psychological well-being among sexual minorities and heterosexual counterparts. Sexuality Research and Social Policy, 18(2), 221–232. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13178-020-00451-z

Suen, L. W., Lunn, M. R., Katuzny, K., Finn, S., Duncan, L., Sevelius, J., Flentje, A., Capriotti, M. R., Lubensky, M. E., Hunt, C., Weber, S., Bibbins-Domingo, K., & Obedin-Maliver, J. (2020). What sexual and gender minority people want researchers to know about sexual orientation and gender identity questions: A qualitative study. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 49(7), 2301–2318. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-020-01810-y

Sykes, W., & Collins, M. (1988). Effects of mode of interview: Experiments in the U.K. In R. M. Groves, P. P. Biemer, L. E. Lyberg, J. T. Massey, W. L. Nicholls, & J. Waksberg (Eds.), Telephone survey methodology (pp. 301–320). Wiley.

Talley, A. E., Grimaldo, G., Wilsnack, S. C., Hughes, T. L., & Kristjanson, A. F. (2016). Childhood victimization, internalizing symptoms, and substance use among women who identify as mostly heterosexual. LGBT Health, 3(4), 266–274. https://doi.org/10.1089/lgbt.2015.0073

Tran, N. K., Hatzenbuehler, M. L., & Goldstein, N. D. (2019). Potential relationship between HIV criminalization and structural stigma related to sexual orientation in the United States. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 80(5), e106–e108. https://doi.org/10.1097/QAI.0000000000001961

Ueda, P., Mercer, C. H., Ghaznavi, C., & Herbenick, D. (2020). Trends in frequency of sexual activity and number of sexual partners among adults aged 18 to 44 years in the US, 2000–2018. JAMA Network Open, 3(6), e203833. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.3833

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). (2018). 2015–2017 National Survey of Family Growth user’s guide: Appendix 5. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nsfg/NSFG_2015-2017_UG_App5_QuexChanges.pdf

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality (SAMHSA). (2018a). National Survey on Drug Use and Health 2015 (NSDUH-2015-DS0001). Retrieved on October 14, 2022, from https://datafiles.samhsa.gov/

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality (SAMHSA). (2018b). National Survey on Drug Use and Health 2016 (NSDUH-2016-DS0001). Retrieved on October 14, 2022, from https://datafiles.samhsa.gov/

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality (SAMHSA). (2018c). National Survey on Drug Use and Health 2017 (NSDUH-2017-DS0001). Retrieved on October 14, 2022, from https://datafiles.samhsa.gov/

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality (SAMHSA). (2019). National Survey on Drug Use and Health 2018 (NSDUH-2017-DS0001). Retrieved on October 14, 2022, from https://datafiles.samhsa.gov/

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). (2020a). Smoking cessation. A report of the surgeon general. Atlanta: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality (SAMHSA). (2020b). National Survey on Drug Use and Health 2019 (NSDUH-2017-DS0001). Retrieved on October 14, 2022, from https://datafiles.samhsa.gov/

Veliz, P., Matthews, A. K., Arslanian-Engoren, C., Evans-Polce, R. J., Lee, J. G. L., Boyd, C. J., Hughes, T., McCabe, V. V., & McCabe, S. E. (2019). LDCT lung cancer screening eligibility and use of CT scans for lung cancer among sexual minorities. Cancer Epidemiology, 60, 51–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.canep.2019.03.009

Walsh, A. R., & Stephenson, R. (2021). Assessing the reliability of self-reported sexual behavior among male couples. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 50(3), 1067–1086. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-020-01857-x

Weber, S. (2008). Parenting, family life, and well-being among sexual minorities: Nursing policy and practice implications. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 29(6), 601–618. https://doi.org/10.1080/01612840802048824

West, B. T., & McCabe, S. E. (2021). Choices matter: How response options for survey questions about sexual identity affect population estimates of its association with alcohol, tobacco, and other drug use. Field Methods, 33(4), 335–354. https://doi.org/10.1177/1525822X21998516

Funding

This study was funded by NIH Grant Number 1R03HD107236-01A1 (PI: BTW).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

BTW designed the study, conducted literature review, supervised the data management and data analysis, drafted the manuscript, and finalized the manuscript. CWE conducted literature review, performed data management and data analysis, drafted the manuscript, and reviewed the manuscript. TSS helped to design the study and reviewed the manuscript. IJT performed data management and data analysis, and reviewed the manuscript. SEM helped to design the study, conducted literature review, and reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest or competing interests associated with this work.

Research Involving Human Participants

This research was entirely based on secondary data analysis. More information about the data collection and protection of human subjects can be found at the respective NSFG and NSDUH websites.

Informed Consent

More information about the data collection, the informed consent process, and protection of human subjects can be found at the respective NSFG and NSDUH websites.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

West, B.T., Engstrom, C.W., Schepis, T.S. et al. How a “Something Else” Response Option for Sexual Identity Affects National Survey Estimates of Associations Between Sexual Identity, Reproductive Health, and Substance Use. Arch Sex Behav 53, 107–126 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-023-02710-7

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-023-02710-7