Abstract

It is unclear whether sexual well-being, which is an important part of individual and relational health, may be at risk for declines after a pregnancy loss given the limits of prior work. Accordingly, in a cross-sectional study, we used structural equation modeling to (1) compare sexual well-being levels—satisfaction, desire, function, distress, and frequency—of both partners in couples who had experienced a pregnancy loss in the past four months (N = 103 couples) to their counterparts in a control sample of couples with no history of pregnancy loss (N = 120 couples), and (2) compare sexual well-being levels of each member of a couple to one another. We found that gestational individuals and their partners in the pregnancy loss sample were less sexually satisfied than their control counterparts but did not differ in sexual desire, problems with sexual function, nor sexual frequency. Surprisingly, we found that partners of gestational individuals had less sexual distress than their control counterparts. In the pregnancy loss sample, gestational individuals had lower levels of sexual desire post-loss than their partners but did not differ in sexual satisfaction, problems with sexual function, nor sexual distress. Our results provide evidence that a recent pregnancy loss is associated with lower sexual satisfaction and greater differences between partners in sexual desire, which may be useful information for clinicians working with couples post-loss. Practitioners can share these findings with couples who may find it reassuring that we did not find many aspects of sexual well-being to be related to pregnancy loss at about three months post-loss.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data Availability

The data and materials for this study can be found at https://osf.io/z427u/.

Notes

The control sample data came from a broader study. Thus, there are some differences in eligibility criteria between the samples, such as the required relationship duration.

Percentages do not add to 100% as one couple was missing information on the number of weeks pregnant when the loss occurred.

Initially, in line with Mitchell et al. (2022) and our pre-registration, we utilized the full Problem Distress subscale of the Sexual Function Evaluation Questionnaire. In addition to the max score item we describe, the full subscale includes three other items relating to lacking interest, enjoyment, and excitement/arousal during sex. Per the pattern provided by Mitchell et al. (2022), we attempted to model this construct as a latent variable. Reliability was good for gestational individuals (ω = .79), partners of gestational individuals (ω = .77), and control AFAB individuals (ω = .77). However, reliability was poor for partners of control AFAB individuals (ω = .42) (and poorer yet for control partners who indicated their sex was male: ω = .36). Upon further inspection, we observed that the three items relating to lacking interest, enjoyment, and enjoyment/arousal were heavily kurtote and skewed toward no concern at all (a score of zero) and were poorly correlated with one another and the max item (r = .11–.48). Rather than exclude control partners because their subscale had poor reliability, we decided to directly compare the four groups on the maximum score item, which was neither skewed nor kurtote and adequately represented our aim to examine problems in sexual function and we had separately measured sexual desire. It is plausible the Problem Distress subscale of the SFEQ works best when men and individuals assigned male at birth have a specific sexual stressor or problem (like pregnancy loss) but not as well when they do not have a specific problem (i.e., are part of a control sample); this subscale may work well for women and AFAB regardless of if they have a specific stressor/problem or not. The subscale was originally validated among a clinical sample, and more work with this scale among community samples may be insightful.

The original power analysis as posted on the study’s OSF page assumed a sample size of 105 for the pregnancy loss sample and 128 for the control sample. The numbers reported in this paragraph came from an updated power analysis ran on October 21, 2022, which used the exact same model parameters as before, but updated the sample sizes for the pregnancy loss and control samples respectively to 103 and 120, which are the actual sample sizes used in the current study. This updated power analysis is also posted on the OSF page. Differences in expected and actual sample sizes are a result of data cleaning.

For sexual satisfaction, sexual desire, and sexual distress, CFI, RMSEA, and normed \(\chi^{{2}}\) were in typically accepted ranges, but SRMR was too high (less than .10 is recommended; Hair, et al, 2010). This result may be an artifact of the “reliability paradox” (Hancock & Mueller, 2011), where a latent factor with low factor loadings (poor reliability) may have better model fit than a latent factor with high factor loadings (good reliability). For example, Ximénez and colleagues (2022) found that SRMR tends to be higher when standardized factor loadings are high (close to 1); the factor loadings for indicators of sexual satisfaction (GMSEX), sexual desire (SDI-2), and sexual distress (SDS-SF) were predominantly high (~ .7–.9). Considering this reliability paradox, and the fact that CFI, RMSEA and normed χ2 were acceptable for all models, we proceeded with caution to test mean differences between groups on these outcomes.

References

Allsop, D. B., Péloquin, K., Saxey, M. T., Rossi, M. A., & Rosen, N. O. (2023). Perceived financial burden is indirectly linked to sexual well-being via quality of life among couples seeking medically assisted reproduction. Frontiers in Psychology, 14. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1063268

Allsop, D. B., Wang, C.-Y., Dew, J. P., Holmes, E. K., Hill, E. J., & Leavitt, C. E. (2020). Daddy, mommy, and money: The association between parental materialism on parent–child relationship quality. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 42(2), 325–334. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-020-09705-9

Arpin, V., Brassard, A., El Amiri, S., & Peloquin, K. (2019). Testing a new group intervention for couples seeking fertility treatment: Acceptability and proof of concept. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 45(4), 303–316. https://doi.org/10.1080/0092623X.2018.1526836

Bois, K., Bergeron, S., Rosen, N., Mayrand, M. H., Brassard, A., & Sadikaj, G. (2016). Intimacy, sexual satisfaction, and sexual distress in vulvodynia couples: An observational study. Health Psychology, 35(6), 531–540. https://doi.org/10.1037/hea0000289

Bradford, J., Reisner, S. L., Honnold, J. A., & Xavier, J. (2013). Experiences of transgender-related discrimination and implications for health: Results from the Virginia Transgender Health Initiative Study. American Journal of Public Health, 103(10), 1820–1829. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2012.300796

Brier, N. (2008). Grief following miscarriage: A comprehensive review of the literature. Journal of Women’s Health, 17(3), 451–464. https://doi.org/10.1089/jwh.2007.0505

Camacho-Ávila, M., Hernández-Sánchez, E., Fernández-Férez, A., Fernández-Medina, I. M., Fernández-Sola, C., Conesa-Ferrer, M. B., & Ventura-Miranda, M. I. (2023). Sexuality and affectivity after a grieving process for an antenatal death: A qualitative study of fathers’ experiences. Journal of Mens’ Health, 19, 36–44. https://doi.org/10.22514/jomh.2023.010

Cao, C., Yang, L., Xu, T., Cavazos-Rehg, P. A., Liu, Q., McDermott, D., Veronese, N., Waldhoer, T., Ilie, P. C., Shariat, S. F., & Smith, L. (2020). Trends in sexual activity and associations with all-cause and cause-specific mortality among US adults. Journal of Sexual Medicine, 17(10), 1903–1913. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsxm.2020.05.028

Cheung, G. W., & Rensvold, R. B. (2002). Evaluating goodness-of-fit indexes for testing measurement invariance. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 9(2), 233–255. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15328007sem0902_5

Close, C., Bateson, K., & Douglas, H. (2020). Does prenatal attachment increase over pregnancy? British Journal of Midwifery, 28(7), 436–441. https://doi.org/10.12968/bjom.2020.28.7.436

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Routledge Academic.

Cornelius, T., DiGiovanni, A., Scott, A. W., & Bolger, N. (2022). Covid-19 distress and interdependence of daily emotional intimacy, physical intimacy, and loneliness in cohabiting couples. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 39(12), 3638–3659. https://doi.org/10.1177/02654075221106391

Diamond, D. J., & Diamond, M. O. (2016). Understanding and treating the psychosocial consequences of pregnancy loss. In A. Wenzel (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of perinatal psychology (pp. 487–523). Oxford University Press.

Diamond, L. M., & Huebner, D. M. (2012). Is good sex good for you? Rethinking sexuality and health. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 6(1), 54–69. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-9004.2011.00408.x

Dong, M., Wu, S., Zhang, X., Zhao, N., Tao, Y., & Tan, J. (2022). Impact of infertility duration on male sexual function and mental health. Journal of Assisted Reproduction and Genetics, 39, 1861–1872. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10815-022-02550-9

Dubé, J. P., Dawson, S. J., & Rosen, N. O. (2020). Emotion regulation and sexual well-being among women: Current status and future directions. Current Sexual Health Reports, 12, 43–52. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11930-020-00261-9

Dyregrov, A., & Gjestad, R. (2011). Sexuality following the loss of a child. Death Studies, 35(4), 289–315. https://doi.org/10.1080/07481187.2010.527753

El Amiri, S., Brassard, A., Rosen, N. O., Rossi, M. A., Beaulieu, N., Bergeron, S., & Peloquin, K. (2021). Sexual function and satisfaction in couples with infertility: A closer look at the role of personal and relational characteristics. Journal of Sexual Medicine, 18(12), 1984–1997. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsxm.2021.09.009

Elmerstig, E., Wijma, B., & Bertero, C. (2008). Why do young women continue to have sexual intercourse despite pain? Journal of Adolescent Health, 43(4), 357–363. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2008.02.011

Francisco, M. D. F. R., Mattar, R., Bortoletti, F. F., & Nakamura, M. U. (2014). Sexuality and depression among pregnant women with recurrent spontaneous abortion. Revista Brasileira de Ginecologia e Obstetrícia, 36(4), 152–156. https://doi.org/10.1590/s0100-720320140050.0004

Furukawa, A. P., Patton, P. E., Amato, P., Li, H., & Leclair, C. M. (2012). Dyspareunia and sexual dysfunction in women seeking fertility treatment. Fertility and Sterility, 98(6), 1544-1548 e1542. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2012.08.011

Gaetano, J. (2013). Holm-Bonferroni sequential correction: An excel calculator. ResearchGate.net. https//www.doi.org/https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.1.4466.9927

Galovan, A. M., Holmes, E. K., & Proulx, C. M. (2016). Theoretical and methodological issues in relationship research: Considering the Common Fate Model. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 34(1), 44–68. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407515621179

Gauvin, S. E. M., Mulroy, M. E., McInnis, M. K., Jackowich, R. A., Levang, S. L., Coyle, S. M., & Pukall, C. F. (2022). An investigation of sexual and relationship adjustment during COVID-19. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 51(1), 273–285. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-021-02212-4

Gold, K. J., Sen, A., & Hayward, R. A. (2010). Marriage and cohabitation outcomes after pregnancy loss. Pediatrics, 125(5), e1202-1207. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2009-3081

Gravensteen, I. K., Jacobsen, E. M., Sandset, P. M., Helgadottir, L. B., Radestad, I., Sandvik, L., & Ekeberg, O. (2018). Anxiety, depression and relationship satisfaction in the pregnancy following stillbirth and after the birth of a live-born baby: A prospective study. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 18(1), 41. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-018-1666-8

Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (2010). Multivariate data analysis (7th ed.). Pearson Prentice Hall.

Hancock, G. R., & Mueller, R. O. (2011). The reliability paradox in assessing structural relations within covariance structure models. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 71(2), 306–324. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013164410384856

Hasanpour, V., Keshavarz, Z., Azin, S. A., Ansaripour, S., & Ghasemi, E. (2019). Comparison of sexual function and intimacy in women with and without recurrent miscarriage. Journal of Isfahan Medical School, 37(533), 768–774.

Herbert, D., Young, K., Pietrusinska, M., & MacBeth, A. (2022). The mental health impact of perinatal loss: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders, 297, 118–129. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2021.10.026

Hill, E. J., Allsop, D. B., LeBaron, A. B., & Bean, R. A. (2017). How do money, sex, and stress influence marital instability? Journal of Financial Therapy, 8(1), 21–42. https://doi.org/10.4148/1944-9771.1135

Holm, S. (1979). A simple sequentially rejective multiple test procedure. Scandinavian Journal of Statistics, 6(2), 65–70.

Howard, W. J., Rhemtulla, M., & Little, T. D. (2015). Using principal components as auxiliary variables in missing data estimation. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 50(3), 285–299. https://doi.org/10.1080/00273171.2014.999267

Impett, E. A., Muise, A., & Peragine, D. (2014). Sexuality in the context of relationships. In D. L. Tolman, L. M. Diamond, J. A. Bauermeister, W. H. George, J. G. Pfaus, & L. M. Ward (Eds.), APA handbook of sexuality and psychology, Vol. 1: Person-based approaches (pp. 269–315). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/14193-010

Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Understanding and Eliminating Racial Ethnic Disparities in Health Care. (2003). Unequal treatment: Confronting racial and ethnic disparities in health care. https://doi.org/10.17226/12875

Jaffe, J., & Diamond, M. O. (2011). Reproductive trauma: Psychotherapy with infertility and pregnancy loss clients (1st ed.). American Psychological Association.

Joel, S., Eastwick, P. W., Allison, C. J., Arriaga, X. B., Baker, Z. G., Bar-Kalifa, E., Bergeron, S., Birnbaum, G. E., Brock, R. L., Brumbaugh, C. C., Carmichael, C. L., Chen, S., Clarke, J., Cobb, R. J., Coolsen, M. K., Davis, J., de Jong, D. C., Debrot, A., DeHaas, E. C., ... Wolf, S. (2020). Machine learning uncovers the most robust self-report predictors of relationship quality across 43 longitudinal couples studies. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 117(32), 19061–19071. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1917036117.

Jurkovic, D., Overton, C., & Bender-Atik, R. (2013). Diagnosis and management of first trimester miscarriage. British Medical Journal, 346(7913), 34–37. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.f3676

Kenny, D. A., Kashy, D. A., & Cook, W. L. (2006). Dyadic data analysis. Guilford Publications.

Lang, K., Little, T., Chesnut, S., Gupta, V., Jung, B., Panko, P., & Waggenspack, L. (2020). Pcaux: Automatically extract auxiliary features for simple, principled missing data analysis. https://github.com/PcAux-Package/PcAux

Lawrance, K., & Byers, E. S. (1995). Sexual satisfaction in long-term heterosexual relationships: The Interpersonal Exchange Model of Sexual Satisfaction. Personal Relationships, 2(4), 267–285. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6811.1995.tb00092.x

Lundin, U., & Elmerstig, E. (2015). “Desire? Who needs desire? Let’s just do it!”: A qualitative study concerning sexuality and infertility at an internet support group. Sexual and Relationship Therapy, 30(4), 433–447. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681994.2015.1031100

Mark, K. P., Herbenick, D., Fortenberry, J. D., Sanders, S., & Reece, M. (2014). A psychometric comparison of three scales and a single-item measure to assess sexual satisfaction. Journal of Sex Research, 51(2), 159–169. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2013.816261

Markin, R. D. (2016). What clinicians miss about miscarriages: Clinical errors in the treatment of early term perinatal loss. Psychotherapy, 53(3), 347–353. https://doi.org/10.1037/pst0000062

Mekosh-Rosenbaum, V., & Lasker, J. N. (1995). Effects of pregnancy outcomes on marital satisfaction: A longitudinal study of birth and loss. Infant Mental Health Journal, 16(2), 127–143. https://doi.org/10.1002/1097-0355(199522)16:2%3c127::AID-IMHJ2280160207%3e3.0.CO;2-6

Mitchell, K. R., Gurney, K., McAloney-Kocaman, K., Kiddy, C., & Parkes, A. (2022). The Sexual Function Evaluation Questionnaire (SFEQ) to evaluate effectiveness of treatment for sexual difficulties: Development and validation in a clinical sample. Journal of Sex Research, 59(4), 426–434. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2021.1986800

Moyano, N., Vallejo-Medina, P., & Sierra, J. C. (2017). Sexual Desire Inventory: Two or three dimensions? Journal of Sex Research, 54(1), 105–116. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2015.1109581

Muise, A., Impett, E. A., & Desmarais, S. (2013). Getting it on versus getting it over with: Sexual motivation, desire, and satisfaction in intimate bonds. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 39(10), 1320–1332. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167213490963

Muise, A., Schimmack, U., & Impett, E. A. (2015). Sexual frequency predicts greater well-being, but more is not always better. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 7(4), 295–302. https://doi.org/10.1177/1948550615616462

Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. (1998–2017). Mplus user’s guide (8th ed.). Muthén & Muthén.

Ostwald, S. K., Bernal, M. P., Cron, S. G., & Godwin, K. M. (2009). Stress experienced by stroke survivors and spousal caregivers during the first year after discharge from inpatient rehabilitation. Topics in Stroke Rehabilitation, 16(2), 93–104. https://doi.org/10.1310/tsr1602-93

Patterson, J. M. (1988). Families experiencing stress: I. The Family Adjustment and Adaptation Response Model: II. Applying the FAAR model to health-related issues for intervention and research. Family Systems Medicine, 6(2), 202–237. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0089739

Patterson, J. M. (2002). Integrating family resilience and family stress theory. Journal of Marriage and Family, 64(2), 349–360.

Puscheck, E. E. (2018). Early pregnancy loss. https://reference.medscape.com/article/266317-print

Putnick, D. L., & Bornstein, M. H. (2016). Measurement invariance conventions and reporting: The state of the art and future directions for psychological research. Developmental Review, 41, 71–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dr.2016.06.004

R Core Team. (2022). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. https://www.r-project.org/

Reed, B. D., Harlow, S. D., Sen, A., Legocki, L. J., Edwards, R. M., Arato, N., & Haefner, H. K. (2012). Prevalence and demographic characteristics of vulvodynia in a population-based sample. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 206(2), 170 e171-179. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2011.08.012

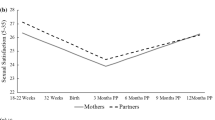

Rosen, N. O., Dawson, S. J., Leonhardt, N. D., Vannier, S. A., & Impett, E. A. (2020). Trajectories of sexual well-being among couples in the transition to parenthood. Journal of Family Psychology, 35(4), 523–533. https://doi.org/10.1037/fam0000689

Rosen, N. O., Dube, J. P., Corsini-Munt, S., & Muise, A. (2018). Partners experience consequences, too: A comparison of the sexual, relational, and psychological adjustment of women with sexual interest/arousal disorder and their partners to control couples. Journal of Sexual Medicine, 16(1), 83–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsxm.2018.10.018

Rosen, N. O., Muise, A., Bergeron, S., Impett, E. A., & Boudreau, G. K. (2015). Approach and avoidance sexual goals in couples with provoked vestibulodynia: Associations with sexual, relational, and psychological well-being. Journal of Sexual Medicine, 12(8), 1781–1790. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsm.12948

Rosen, R., Brown, C., Heiman, J., Leiblum, S., Meston, C., Shabsigh, R., Ferguson, D., & D’Agostino, R., Jr. (2000). The Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI): A multidimensional self-report instrument for the assessment of female sexual function. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 26(2), 191–208. https://doi.org/10.1080/009262300278597

Rosen, R. C., Riley, A., Wagner, G., Osterloh, I. H., Kirkpatrick, J., & Mishra, A. (1997). The International Index of Erectile Function (IIEF): A multidimensional scale for assessment of erectile dysfunction. Urology, 49(6), 822–830. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0090-4295(97)00238-0

Santos-Iglesias, P., Bergeron, S., Brotto, L. A., Rosen, N. O., & Walker, L. M. (2020). Preliminary validation of the Sexual Distress Scale Short-Form: Applications to women, men, and prostate cancer survivors. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 46(6), 542–563. https://doi.org/10.1080/0092623X.2020.1761494

Schnarch, D. M. (2009). Intimacy & desire: Awaken the passion in your relationship. Beaufort Books.

Schwenck, G. C., Dawson, S. J., Allsop, D. B., & Rosen, N. O. (2022). Daily dyadic coping: Associations with postpartum sexual desire and sexual and relationship satisfaction. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 39, 3706–3727. https://doi.org/10.1177/02654075221107393

Serrano, F., & Lima, M. L. (2006). Recurrent miscarriage: Psychological and relational consequences for couples. Psychology and Psychotherapy, 79(Pt 4), 585–594. https://doi.org/10.1348/147608306x96992

Spector, I. P., Carey, M. P., & Steinberg, L. (1996). The Sexual Desire Inventory: Development, factor structure, and evidence of reliability. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 22(3), 175–190. https://doi.org/10.1080/00926239608414655

Stephenson, K. R., & Meston, C. M. (2010). Differentiating components of sexual well-being in women: Are sexual satisfaction and sexual distress independent constructs? Journal of Sexual Medicine, 7(7), 2458–2468. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1743-6109.2010.01836.x

Swanson, K. M., Karmali, Z. A., Powell, S. H., & Pulvermakher, F. (2003). Miscarriage effects on couples’ interpersonal and sexual relationships during the first year after loss: Women’s perceptions. Psychosomatic Medicine, 65, 902–910. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.psy.0000079381.58810.84

van Anders, S. M., Herbenick, D., Brotto, L. A., Harris, E. A., & Chadwick, S. B. (2022). The heteronormativity theory of low sexual desire in women partnered with men. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 51, 391–415. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-021-02100-x

Wang, J., & Wang, X. (2019). Structural equation modeling: Applications using Mplus (2nd ed.). John Wiley & Sons.

Wikle, J. S., Leavitt, C. E., Yorgason, J. B., Dew, J. P., & Johnson, H. M. (2020). The protective role of couple communication in moderating negative associations between financial stress and sexual outcomes for newlyweds. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 42(2), 282–299. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-020-09728-2

Ximénez, C., Maydeu-Olivares, A., Shi, D., & Revuelta, J. (2022). Assessing cutoff values of SEM fit indices: Advantages of the unbiased SRMR index and its cutoff criterion based on communality. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 29(3), 368–380. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705511.2021.1992596

Zhang, Y. X., Zhang, X. Q., Wang, Q. R., Yuan, Y. Q., Yang, J. G., Zhang, X. W., & Li, Q. (2016). Psychological burden, sexual satisfaction and erectile function in men whose partners experience recurrent pregnancy loss in China: A cross-sectional study. Reproductive Health, 13(1), 73. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-016-0188-y

Funding

This study was funded by an award given to David Allsop and Natalie Rosen from the IWK Health Centre (Project No. 1026674) and an award given to Natalie Rosen from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada (Grant No. 435-2017-0534).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no known conflicts of interest to disclose.

Ethical Approval

Procedures for the control sample were approved by the Research Ethics Board at Dalhousie University, and those for the pregnancy loss sample were approved by the Research Ethics Board at the IWK Health Centre in Halifax, Nova Scotia. The procedures used in this study adhere to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Allsop, D.B., Huberman, J.S., Cohen, E. et al. What Does a Pregnancy Loss Mean for Sex? Comparing Sexual Well-Being Between Couples With and Without a Recent Loss. Arch Sex Behav 53, 423–438 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-023-02697-1

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-023-02697-1