Abstract

Persistent genital arousal disorder/genitopelvic dysesthesia (PGAD/GPD) is characterized by persistent, unwanted physiological genital arousal (i.e., sensitivity, fullness, and/or swelling) in the absence of sexual excitement or desire which can persist for hours to days and causes significant impairment in psychosocial well-being (e.g., distress) and daily functioning. The etiology and course of PGAD/GPD is still relatively unknown and, unsurprisingly, there are not yet clear evidence-based treatment recommendations for those suffering from PGAD/GPD. We present the case of a 58-year-old woman with acquired persistent genital arousal disorder, which began in March 2020; she believed she developed PGAD/GPD due to a period of significant distress and anxiety related to the COVID-19 pandemic. After seeking medical diagnosis and treatment from multiple healthcare providers and trying a combination of pharmacological and medical treatment modalities, she presented for psychological treatment. An integrative therapy approach (3 assessment sessions, 11 treatment sessions), which included cognitive behavior therapy, distress tolerance and emotion regulation skills from dialectical behavior therapy, and mindfulness practice, was utilized. The patient reported improvements anecdotally (e.g., decreased impact on occupational and social functioning, greater self-compassion, less frequent and shorter duration of PGAD/GPD flare-ups, improved ability to cope with PGAD/GPD symptoms, and decreased need for sleeping medication) and on self-report measures (e.g., lower PGAD/GPD catastrophizing, lower anxiety and depression, and greater overall quality of life).We report the use of an integrative (i.e., psychoeducational, cognitive behavioral, dialectical behavioral, and mindfulness-based) intervention, which may be an effective psychological treatment for PGAD/GPD.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Persistent genital arousal disorder/genitopelvic dysesthesia (PGAD/GPD) is a distressing and rare disorder which is not yet well understood. Generally, PGAD/GPD is characterized as the presence of persistent, unwanted physiological genital arousal (i.e., sensitivity, fullness, and/or swelling) in the absence of sexual excitement or desire which can persist for hours to days and causes significant impairment in psychosocial well-being (e.g., distress) and daily functioning. However, the conceptualization, diagnostic criteria, and terminology of this distressing condition are frequently evolving (see Table 1). For instance, the terminology was recently modified from PGAD to PGAD/GPD following the release of a consensus and process of care paper from leading clinicians and researchers in the area (Goldstein et al., 2021). Further, it has been specified that the sensations could occur in various genitopelvic areas (e.g., clitoris, vulva, bladder) and may be aggravated by a multitude of psychological (e.g., stress, general anxiety), sensory (e.g., music or sounds) and situational (e.g., vibrations from a moving vehicle, sitting) factors (for a detailed description of PGAD/GPD and why terminology was modified, see Goldstein et al., 2021).

The estimated prevalence of PGAD/GPD ranges from 0.6 to 4.3%, suggesting that globally, many individuals are affected (Dèttore & Pagnini, 2020; Garvey et al., 2009; Jackowich & Pukall, 2020b). Unfortunately, the etiology of PGAD/GPD is not yet well understood. Research to date indicates that PGAD/GPD is likely caused and maintained by a combination of biological (e.g., pudendal neuropathy, paracentral lobule hyperactivity), pharmacological (e.g., initiating/discontinuing SSRIs/SNRIs), psychological (e.g., depression, anxiety, catastrophizing), and systems-level (e.g., lack of awareness of PGAD/GPD by clinicians and the public) factors (for a review see Goldstein et al., 2021).

Overall, there is a dearth of research and literature about treatment approaches for PGAD/GPD. However, current evidence suggests that psychological, pharmacological, and physiological treatment approaches may be appropriate and effective (Goldstein et al., 2021; Martín-Vivar et al., 2022; Pease et al., 2022; Pukall et al., 2022). A scoping review of proposed treatments for PGAD/GPD (Martín-Vivar et al., 2022) identified 38 studies and found evidence for physical treatments such as surgery, neuromodulation, and pelvic floor physiotherapy; pharmacological approaches such as the use of paroxetine, duloxetine, and clonazepam; and psychotherapy approaches such as cognitive-behavior therapy (CBT), couples therapy, mindfulness, and hypnotherapy. Notably, the scoping review only identified seven studies which examined psychological interventions, all of which were case studies. Only one of these case studies used validated measures to assess symptoms and response to treatment (e.g., depression and anxiety, sleep quality, quality of life, intensity of symptoms, and marital interference; Elkins et al., 2014), while most did not include any formal assessment of symptoms over the course of treatment (Aswath et al., 2016; Curran, 2019; Eibye & Jensen, 2014; Hiller & Hekster, 2007; Hryńko et al., 2017). Further, most of the existing psychotherapy case studies provide very limited information about the therapeutic techniques utilized (Aswath et al., 2016; Curran, 2019; Eibye & Jensen, 2014; Hryńko et al., 2017). Indeed, some of the sparse descriptions of psychotherapy in these case studies consisted of only: “supportive therapy” (Aswath et al., 2016, p. 341), “trauma-focused therapy” (Curran, 2019, p. 188), “mindfulness therapy,” and “out-patient individual therapy sessions” (Eibye & Jensen, 2014, p. 2). Only three case studies provided some detail beyond therapeutic modality (i.e., Bilal & Cerniglia, 2020; Hiller & Hekster, 2007; Hryńko et al., 2017) and a fourth case study was the only one to provide a detailed description of their psychological intervention (i.e., hypnotherapy; Elkins et al., 2014). Notably, only one existing case study on a psychological treatment for PGAD/GPD both utilized validated measures and included a detailed description of the treatment (Elkins et al., 2014). As Crowe et al. (2011) highlight, it is important for health-related case studies to provide sufficient contextual information (e.g., decision-making processes, treatment approaches) and to include multiple sources of evidence (e.g., qualitative and quantitative) when available. We present a clinical case report which provides additional support (both qualitative and quantitative) for the effectiveness of psychological approaches in treating PGAD/GPD and details the integrative therapy approach utilized.

Case Report

The patient is a 58-year-old, White, heterosexual woman who described herself as an Atheist. She had been married for 37 years (relationship duration approximately 40 years) and had three adult sons. At the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic (end of February 2020/beginning of March 2020), the patient reported an intense increase in stress and anxiety, including difficulty sleeping due to her anxiety about the pandemic. By March 2020, she reported feeling as if her “nervous system was pinned” and she was “stuck in fight or flight mode 24/7.” At the onset of her symptoms, she did not have a primary care physician. She initially presented to the emergency departmentFootnote 1 in March 2020 with what she initially thought was a severe bladder infection (i.e., urge to urinate, sore back, intense pain along her pelvis, feeling like her clitoris was “on all the time,” in addition to vomiting, high blood pressure, and intense anxiety/panic).Footnote 2 Between March 2020 and early April 2020, she presented to the emergency department an additional six times with worsening symptoms and experienced her healthcare team as extremely invalidating (e.g., making jokes about her). Over the course of these seven visits to the emergency department, she was treated for several infections despite testing negative for the presence of an infection. By her final visit, she reportedly had not slept for 11 days and had lost 15 lbs because she was unable to eat due to constant nausea and vomiting. A family member of the patient eventually suggested she see a primary care physician, whom the patient had previously seen for hormone replacement therapy during menopause; this physician suggested a diagnosis of PGAD/GPD and referred her to a gynecologist. The patient saw two gynecologists in the community before eventually receiving a diagnosis of PGAD/GPD in July 2020 (approximately 4 months after symptom onset).

In terms of previous treatment, she had been prescribed several different medications (i.e., quetiapine, escitalopram, clonazepam, gabapentin, tramadol, nortriptyline, Tylenol No. 3 with Codeine (T3s), topical lidocaine, and vaginal suppositories of diazepam) to address her PGAD/GPD symptoms, in addition to her depressive and anxiety symptoms. She reported “some moments of relief [from PGAD/GPD symptoms]” after three weeks of using a combination of vaginal suppositories of diazepam and T3s, but overall, her symptoms remained severe. She also reported that some of the medications (e.g., nortriptyline) worsened her PGAD/GPD symptoms.

One gynecologist referred the patient to a psychologist due to her high suicide risk. The psychologist used an internal family systems therapy approach (Anderson et al., 2017), which the patient felt was not a good fit and ceased treatment. The patient was eventually referred to the British Columbia Centre for Vulvar Health, a multidisciplinary tertiary care center in a large metropolitan city, which provides comprehensive assessment of individuals with vulvar health issues. The gynecologist in the center then referred this patient to a psychology resident (the first author) for psychological treatment. At the time of referral, the patient was taking a combination of prescribed medications for PGAD/GPD (i.e., tramadol 50 mg, clonazepam 0.5 mg, gabapentin 300 mg [three times per day], and amitriptyline 100 mg) to address her symptoms with limited effectiveness (e.g., provided enough relief that she could sleep for a few hours, “walk carefully”, and get dressed). She had been consistently taking these medications for 1 year 2 months and described this combination of medications as “[taking] down the volume of PGAD so [she] could think again” but still reported almost constant PGAD/GPD symptoms which were significantly distressing and impairing.

Assessment

Two initial sessions focused on providing the patient—who had experienced invalidation and dismissal within the healthcare system—with the opportunity to share her experiences and background in a validating environment, and to obtain a general timeline of the PGAD/GPD onset and course. The third session focused on a comprehensive psychosexual assessment and discussion of treatment goals.

At the time of assessment, the patient continued to meet the proposed diagnostic criteria for PGAD/GPD (Table 1). There was no history of illnesses or injuries to her nervous system, although she did report having lifelong irritable bowel syndrome and a recent diagnosis of interstitial cystitis (after the onset of PGAD/GPD). Additionally, she reported “possible bladder damage” during childbirth and a hysterectomy at age 44. There was a history of hypertension (starting at age 51) following a stressful period of time during which a family member was struggling with substance use. She reported difficulties with anxiety and panic attacks, starting at 14-years-old, which caused significant functional impairment starting when she was in her thirties. At the time of presenting for treatment, she was assessed and met DSM-5 criteria for generalized anxiety disorder with panic attacks and described feeling constantly “hypervigilant” about any physiological changes in her body, especially those related to PGAD/GPD. She did not meet DSM-5 criteria for a major depressive episode at the time of assessment but still reported ongoing depressive symptoms. She may have met criteria for persistent depressive disorder; however, this was not formally assessed. She denied current suicidal ideation.

She grew up in an emotionally invalidating environment and her mother allegedly had a history of substance abuse. She described becoming hypervigilant and detail-oriented as a child in order to maintain her safety. The patient also reported two significant losses, her best-friend dying suddenly and her father dying approximately one year prior to the pandemic following surgical complications. She denied any past or current sexual, physical, or emotional abuse.

Regarding other aspects of her sexual functioning, she reported current and past low spontaneous sexual desire (solo and partnered) and was not distressed by this; she also reported rarely experiencing sexual attraction to others, instead describing her attraction as being emotional and mental. She had not received any formal or informal sexual education at home or in school as a child or adolescent. She denied any non-consensual or unwanted sexual encounters; however, she reported that her first experience of penetrative sexual intercourse was “excruciating…like a knife.” She denied pain during sexual intercourse with any other partners, including her husband, but stated that she did not find these sexual experiences satisfying or pleasant. She currently avoided solo or partnered sexual activity and reported that masturbation triggered PGAD/GPD flare-ups which lasted for weeks.

The patient reported her PGAD/GPD symptoms were frequently triggered by high levels of anxiety, and she attributed the onset of PGAD/GPD to stress related to the COVID-19 pandemic. She was unable to wear pants for 18 months and unable to sit down for long durations as these would worsen her PGAD/GPD symptoms. The patient reportedly found visual and auditory stimuli (e.g., lights, music, and television) overstimulating and these caused increases in anxiety and PGAD/GPD symptoms. Following the onset of PGAD/GPD symptoms, the patient experienced intense feelings of shame, felt socially isolated, had a major depressive episode with frequent suicidal ideation (lasting eight months), and elevated anxiety (lasting three months). The patient was employed as a childbirth educator, doula, and doula educator, but had to retire from her profession in 2020 due to her PGAD/GPD, anxiety, and depressive symptoms. After finding a combination of prescribed medications took “down the volume” of her PGAD/GPD symptoms, she was unable to return to her previous career but became self-employed part-time in a family-owned bakery business. She reported difficulty sleeping due to anxiety and PGAD/GPD symptoms and described that she frequently awakened in the morning with the physical sensation of a “level 10 orgasm.” At the time of assessment, she described her PGAD/GPD symptoms as “pre-orgasmic agony.”

Treatment

Treatment included a combination of psychoeducation, cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), mindfulness, and dialectical behavior therapy (DBT). Eleven therapy sessions (typically weekly, on average 50-min) were conducted online over the course of four months. All sessions were conducted virtually using the Zoom videoconferencing platform.

Initially, session content focused on psychoeducation and mindfulness, then CBT strategies, followed by emotion regulation and distress tolerance DBT skills. Importantly, the therapeutic approach was truly integrated, with most sessions involving therapeutic communication styles of DBT (including during the assessment sessions) and a balance of the core components of CBT, DBT skills, and mindfulness. Additionally, an emphasis was placed on the dialectic of acceptance and change throughout all sessions. A summary of the session content/themes and homework assigned can be found in Table 2.

Psychoeducation

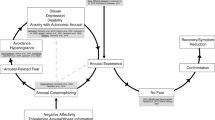

The Fear-Avoidance Model of PGAD/GPD (Jackowich & Pukall, 2020a) was introduced to the patient, who found it validating and reported it fit her experience of PGAD/GPD (Fig. 1). This model is based on a biopsychosocial framework, which is commonly utilized in the chronic pain literature and has previously been applied to sexual pain disorders (Davis et al., 2015; Thomtén & Linton, 2013). The Fear-Avoidance Model of PGAD/GPD suggests that if the physical symptoms of PGAD/GPD are interpreted as threatening, this will lead to catastrophizing about and fear of these sensations. Consequently, individuals become hypervigilant and engage in avoidance of behaviors/triggers related to sensations of arousal. Avoidance and hypervigilance then lead to negative psychosocial outcomes (e.g., anxiety, depression, decreased quality of life), which help to maintain the cycle by contributing to the experience and awareness of arousal sensations. Further, the Fear-Avoidance Model proposes that cognitive and behavioral strategies (e.g., cognitive restructuring, exposure, and relaxation) could be used to reduce fear and catastrophizing, increase adaptive coping, and increase acceptance of PGAD/GPD symptoms, which would then lead to reduced symptoms and increased engagement in activities of daily living (i.e., recovery).

Fear-Avoidance Model of PGAD/GPD. Note The Fear-Avoidance Model as applied to PGAD/GPD. The left side (light grey) depicts factors that maintain the cycle, and in turn, PGAD/GPD symptoms. The right side (dark grey) depicts factors that help move one out of the cycle, promoting symptom reduction and adaptation. The grey dashed arrows represent associations between variables within the model that have been supported by research [e.g., association between catastrophizing and depression; (Jackowich et al., 2018)]. Figure adapted from Jackowich and Pukall (2020a) and Goldstein et al. (2021). PGAD/GPD = persistent genital arousal disorder/genitopelvic dysesthesia

Cognitive Behavior Therapy-Based Strategies

Cognitive behavior therapy (CBT) has been shown to be an effective psychotherapy approach for other sexual dysfunctions (e.g., provoked vestibulodynia; Bergeron et al., 2016; Goldfinger et al., 2016). Additionally, two case studies support the use of CBT-based techniques for PGAD/GPD (Bilal & Cerniglia, 2020; Hiller & Hekster, 2007). Further, CBT is an effective treatment for mood and anxiety disorders, suggesting it could also be used to help address some of this patient’s comorbidities. The CBT-specific strategies utilized included: (1) a PGAD/GPD symptom tracking log to increase awareness of symptoms as well as the connections between triggers, thoughts, emotions, and PGAD/GPD symptoms; (2) thought records and cognitive restructuring of cognitive distortions related to PGAD/GPD; (3) identifying negative core beliefs; (4) a decisional balance about holding current negative core belief vs. holding an alternative, more balanced core belief; and (5) behavioral experiments to challenge PGAD/GPD-related cognitive distortions, especially those related to catastrophizing, fortune telling, and hypervigilance.

Mindfulness-Based Strategies

Mindfulness-based therapy has been found to be effective for sexual arousal (Brotto et al., 2008, 2022; Rashedi et al., 2022) and sexual pain disorders in women (Boerner & Rosen, 2015; Brotto et al., 2019; Dunkley & Brotto, 2016), as well as anxiety and depression (Hofmann et al., 2010; Khoury et al., 2013). Additionally, there is evidence from the chronic pain literature that mindfulness therapy leads to significantly greater reductions in pain catastrophizing and stress-related affect, relative to CBT (Davis et al., 2015). Given the role of catastrophizing in PGAD/GPD (Fear-Avoidance Model of PGAD/GPD; Fig. 1), mindfulness-based therapy may be an effective treatment for PGAD/GPD. Further, there is one case study supporting the use of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT) for PGAD/GPD (Bilal & Cerniglia, 2020). As such, mindfulness skills were introduced and core tenets of mindfulness were integrated throughout treatment. For instance, there was a focus on remaining non-judgementally in the present moment and developing metacognitive awareness, as well as bringing awareness to sensations of PGAD/GPD with equanimity and acceptance, curiosity, and self-compassion.

Dialectical Behavior Therapy-Based Strategies

DBT is a gold-standard treatment for those with borderline personality disorder, who struggle with emotion dysregulation and distress tolerance (Linehan, 2015; Linehan et al., 1991, 2015). Additionally, there is some evidence that DBT skills training can be an effective treatment for chronic pain, with improvements in emotion regulation, decreased pain intensity and catastrophizing, as well as with mood, coping behaviors, sleep, and general well-being (Linton & Fruzzetti, 2014; Norman-Nott et al., 2022). Further, DBT has recently been suggested as a treatment approach for sexual dysfunctions in those with a history of childhood sexual abuse (Wohl & Kirschen, 2018), although has not yet been evaluated as such.

The key components of DBT are a synthesis of acceptance with change, inclusion of mindfulness, emphasis on the therapeutic relationship, and an emphasis on dialectical processes (Linehan, 1993). The biosocial theory behind DBT was a particularly good fit for this patient given that the invalidating environment she grew up in led to the development of core beliefs and patterns of behavior which may have contributed to the onset of and/or maintained her PGAD/GPD. Further, this invalidating environment likely contributed to her struggling to label and modulate her physical and emotional arousal, tolerate distress, or to trust her own emotional responses as valid interpretations of events (Linehan, 1993).

General therapeutic communication styles from DBT were utilized throughout treatment, including irreverent and reciprocal communication. Self-disclosure was also used for the therapist to share her immediate personal reactions to the patient and the patient’s behavior. Core DBT strategies of problem-solving and validation (especially radical genuineness) were utilized to strike a balance between change and acceptance for PGAD/GPD. The patient seemed to respond particularly well to the DBT therapeutic communication styles, and a strong therapeutic alliance appeared to develop in part due to these communication styles. Given the patient’s past experiences with healthcare providers, a therapeutic alliance that included a deep sense of trust and connectedness was fundamental for engagement in treatment.

The distress tolerance TIPP skills were introduced to help the patient manage extreme arousal (both emotional and physiological). These skills are Temperature (i.e., submerging face in ice water to elicit the dive response), Intense exercise, Paced breathing, and Paired muscle relaxation (Linehan, 2015). The emotion regulation PLEASE skills (i.e., treat PhysicaL illness, balanced Eating, avoid mood-Altering substances, balanced Sleep, and get Exercise; Linehan, 2015) were introduced to help the patient decrease vulnerability to negative emotions and increase emotional resilience. The patient was encouraged to use TIPP when experiencing either high levels of emotional distress or high levels of physical distress associated with PGAD/GPD, which she reported reduced her symptoms and quickly and effectively. Given that she also tended to prioritize others and neglect her own physical well-being (e.g., work for 15 h straight with no breaks or food), these emotion regulation skills were a priority. However, the PLEASE skills were introduced towards the end of therapy, when she was able to challenge the automatic negative thoughts she had about taking care of herself, which were related to an underlying core belief that she was unlovable, and thus willing to prioritize her own well-being.

Outcomes

At the end of treatment, the patient reported improvements, which were assessed quantitatively (using self-report questionnaires) and qualitatively (through verbal self-report during final therapy session).

Quantitative

Throughout treatment, the patient completed self-report measures assessing depressive and anxiety symptoms (i.e., BDI-II and BAI; Beck & Steer, 1993; Beck et al., 1996), quality of life (Functional Status Questionnaire; Jette et al., 1986), as well as a measure assessing catastrophizing about PGAD/GPD symptoms (i.e., Pain Catastrophizing Scale; Sullivan et al., 1995; this scale has previously been adapted and utilized with PGAD/GPD samples; Jackowich et al., 2018). Self-report measures were completed approximately every two weeks. (Unfortunately, self-report measures were not utilized for the first two months of treatment. Further, the patient did not always complete every self-report measure at each timepoint. This resulted in only three timepoints of data collection for the self-report measures). Over the course of therapy, the patient experienced a reduction in overall catastrophizing about PGAD/GPD symptoms, and reductions in rumination, magnification, and feelings of helplessness about PGAD/GPD (Fig. 2). Additionally, she experienced reductions in her depressive and anxiety symptoms (Fig. 3) and increases in several aspects of her quality of life, including intermediate activities of daily living (e.g., walking, doing light housework, grocery shopping, driving a car, engaging in vigorous exercise), work performance, mental health, and quality of social interactions (Fig. 4).

Patient scores on PGAD/ GPD catastrophizing subscales over time. Note The patient’s scores on the subscales of a self-report measure of PGAD/GPD catastrophizing (a modified version of the Pain Catastrophizing Scale; Sullivan et al., 1995). PGAD/GPD = persistent genital arousal disorder/genitopelvic dysesthesia

Patient’s scores on the subscales of the Functional Status Questionnaire. Note The Functional Status Questionnaire assesses quality of life in six different areas: (1) Basic Activities of Daily Living, (2) Intermediate Activities of Daily Living, (3) Mental Health, (4) Work Performance, (5) Social Activities, and (6) Quality of Interactions. The patient’s scores on basic activities of daily living remained at 100 throughout treatment. Additionally, her scores on intermediate activities of daily living, mental health, work performance, and quality of interactions all increased over the course of treatment. In contrast, her scores on the social activities’ subscale had decreased slightly, although the client reported that this was not due to PGAD/GPD, but rather other situational factors (i.e., the physical and/or psychological health of two of her relatives declining). PGAD/GPD = persistent genital arousal disorder/genitopelvic dysesthesia

Qualitative

The patient also verbally reported several areas of improvement over the course of treatment and during her final treatment session. She reported some decrease in the frequency and severity of PGAD/GPD flare-ups, and—more importantly—she felt more confident in her ability to cope with flare-ups and had more acceptance towards her condition (e.g., “I may not always have PGAD, but if I do I know I am in control and can cope with it”). Further, she began prioritizing herself and her own well-being, which was leading to improved relationships with her family, especially her husband. She had been able to begin exercising regularly without fear of it triggering a PGAD/GPD flare-up. The patient used mindfulness of breathing daily, which she reported reduced her stress and allowed her to stop taking the amitriptyline. The increased acceptance of PGAD/GPD sensations also seemed to reduce distress associated with the presence of physiological symptoms of PGAD/GPD and anxiety. She was able to develop and hold an alternative, balanced core-belief (“I am enough”), which she reported led to feelings of increased self-worth and reduced distress and shame. There were no notable changes in sexual functioning by the end of treatment (e.g., no changes in sexual desire) and she had not resumed solo or partnered sexual activity. However, the improved coping with PGAD/GPD did appear to result in an improved romantic relationship with her husband. She was even considering going on a vacation with her husband, which she reportedly never would have considered prior to treatment. Overall, at the end of treatment, the client stated that this was the first time in her life that someone was listening to/hearing her, and that she had developed a new way of thinking and relating to her PGAD/GPD and anxiety, as well as improved coping skills.

Discussion

We report a successful treatment of PGAD/GPD with an integrative therapeutic approach which included psychoeducation, CBT, DBT, and mindfulness. A review of the literature revealed only one case report of using CBT couples therapy for PGAD/GPD (Hiller & Hekster, 2007) and one case report using MBCT for PGAD/GPD (Bilal & Cerniglia, 2020); however, there were no other reports of an integrative psychotherapeutic approach such as this. While this psychological treatment was technically provided in parallel with pharmacotherapy (in line with current recommendations; Goldstein et al., 2021), the patient had been on a consistent medication regime for 1 year 2 months yet only experienced marginal benefit. Further, she was able to reduce and then taper off one of her medications (i.e., amitriptyline) because she was experiencing benefit from the psychological intervention. However, it is important to note that we cannot completely dismiss the marginal benefits she received from this combination of medications—which provided enough relief that she was able to do some activities of daily living and engage in psychological treatment—nor that she was receiving pharmacotherapy and psychological therapy in parallel.

Additionally, it is important to note that the patient was no longer experiencing frequent suicidal ideation and desire by the time she presented for treatment. Had she continued to endorse suicidal ideation and desire, the treatment approach may have benefited from slight adjustment to reduce suicidality before targeting the PGAD/GPD. Specifically, DBT would have been emphasized earlier in treatment (e.g., strategies for orientation and commitment to treatment, introducing distress tolerance skills earlier, focus on building a life worth living, and daily tracking of suicidal ideation and urges).

Overall, we present a novel treatment approach for PGAD/GPD, which targets different aspects of the Fear-Avoidance Model of PGAD/GPD (e.g., catastrophizing, avoidance, psychosocial distress/impairment), which seem to maintain the disorder. People with PGAD/GPD typically present to gynaecology and medical approaches are usually considered first-line treatment. However, the success of the presented integrative therapeutic approach suggests that psychological treatments should be considered as a first-line treatment (or at the very least in parallel with first-line pharmacological treatments). Psychological treatment provides a cost-effective, accessible, and minimally invasive treatment option for PGAD/GPD. We encourage gynaecologists and other medical health providers to understand the important role of these therapeutic approaches and when to refer. We hope this clinical case report will inform future research and treatment for individuals with this distressing disorder.

Availability of Data and Materials

Not applicable.

Code Availability

Not applicable.

Notes

All healthcare treatment occurred in British Columbia, Canada, which has a publicly funded universal health care system.

Existing literature has suggested that the nervous system, including the autonomic nervous system, may be involved in the etiology and/or maintenance of PGAD/GPD (Goldstein et al., 2021; Jackowich et al., 2016; Leiblum et al., 2007). Additionally, factors such as stress have been linked to the onset of PGAD/GPD symptoms (Goldstein et al., 2021). Since the autonomic nervous system responses to stress can include physiological changes such as increased blood pressure, nausea, and vomiting (Ziegler, 2012), it is possible that some of her symptoms which seem unusual with PGAD/GPD are better explained by her response to the stress of the COVID-19 pandemic. Further, several other studies mention similar symptoms (e.g., nausea, vomiting, weight loss, hypertension) being present in PGAD/GPD patients (Goldmeier & Leiblum, 2008; Kamatchi & Ashley-Smith, 2013; Oaklander et al., 2020; Scantlebury & Lucas, 2023).

References

Anderson, F. G., Sweezy, M., & Schwartz, R. C. (2017). Internal Family System: Skills training manual trauma-informed treatment for anxiety, depression, PTSD, & substance abuse. PESI Publishing & Media.

Aswath, M., Pandit, L. V., Kashyap, K., & Ramnath, R. (2016). Persistent genital arousal disorder. Indian Journal of Psychological Medicine, 38(4), 341–343. https://doi.org/10.4103/0253-7176.185942

Beck, A. T., & Steer, R. A. (1993). Beck Anxiety Inventory Manual. New York: Psychological Corporation.

Beck, A. T., Steer, R. A., & Brown, G. K. (1996). Beck Depression Inventory (BDI-II): Manual and questionnaire. New York: Psychological Corporation.

Bergeron, S., Khalifé, S., Dupuis, M.-J., & McDuff, P. (2016). A randomized clinical trial comparing group cognitive-behavioral therapy and a topical steroid for women with dyspareunia. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 84(3), 259–268. https://doi.org/10.1037/ccp0000072

Bilal, A., & Cerniglia, L. (2020). Treatment of persistent genital arousal disorder: Single case study. Cogent Psychology, 7(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311908.2020.1849949

Boerner, K. E., & Rosen, N. O. (2015). Acceptance of vulvovaginal pain in women with provoked vestibulodynia and their partners: Associations with pain, psychological, and sexual adjustment. Journal of Sexual Medicine, 12(6), 1450–1462. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsm.12889

Brotto, L. A., Basson, R., & Luria, M. (2008). A mindfulness-based group psychoeducational intervention targeting sexual arousal disorder in women. Journal of Sexual Medicine, 5(7), 1646–1659. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1743-6109.2008.00850.x

Brotto, L. A., Bergeron, S., Zdaniuk, B., Driscoll, M., Grabovac, A., Sadownik, L. A., Smith, K. B., & Basson, R. (2019). A comparison of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy vs cognitive behavioral therapy for the treatment of provoked vestibulodynia in a hospital clinic setting. Journal of Sexual Medicine, 16(6), 909–923. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsxm.2019.04.002

Brotto, L. A., Stephenson, K. R., & Zippan, N. (2022). Feasibility of an online mindfulness-based intervention for women with sexual interest/arousal disorder. Mindfulness, 13(3), 647–659. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-021-01820-4

Crowe, S., Cresswell, K., Robertson, A., Huby, G., Avery, A., & Sheikh, A. (2011). The case study approach. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 11, 100. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-11-100

Curran, K. A. (2019). Case report: Persistent genital arousal disorder in an adolescent woman. Journal of Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology, 32(2), 186–188. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpag.2018.11.009

Davis, S. N. P., Bergeron, S., Bois, K., Sadikaj, G., Binik, Y. M., & Steben, M. (2015). A prospective 2-year examination of cognitive and behavioral correlates of provoked vestibulodynia outcomes. Clinical Journal of Pain, 31(4), 333–341. https://doi.org/10.1097/AJP.0000000000000128

Dèttore, D., & Pagnini, G. (2020). Persistent genital arousal disorder: A study on an Italian group of female university students. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 47(1), 60–79. https://doi.org/10.1080/0092623X.2020.1804022

Dunkley, C. R., & Brotto, L. A. (2016). Psychological treatments for provoked vestibulodynia: Integration of mindfulness-based and cognitive behavioral therapies. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 72(7), 637–650. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.22286

Eibye, S., & Jensen, H. M. (2014). Persistent genital arousal disorder: Confluent patient history of agitated depression, paroxetine cessation, and a tarlov cyst. Case Reports in Psychiatry, 2014. https://doi.org/10.1155/2014/529052

Elkins, G. R., Ramsey, D., & Yu, Y. (2014). Hypnotherapy for persistent genital arousal disorder: A case study. International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Hypnosis, 62(2), 215–223. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207144.2014.869136

Garvey, L. J., West, C., Latch, N., Leiblum, S., & Goldmeier, D. (2009). Report of spontaneous and persistent genital arousal in women attending a sexual health clinic. International Journal of STD & AIDS, 20(8), 519–521. https://doi.org/10.1258/ijsa.2008.008492

Goldfinger, C., Pukall, C. F., Thibault-Gagnon, S., McLean, L., & Chamberlain, S. (2016). Effectiveness of cognitive-behavioral therapy and physical therapy for provoked vestibulodynia: A randomized pilot study. Journal of Sexual Medicine, 13(1), 88–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsxm.2015.12.003

Goldmeier, D., & Leiblum, S. L. (2008). Interaction of organic and psychological factors in persistent genital arousal disorder in women: A report of six cases. International Journal of STD & AIDS, 19(7), 488–490. https://doi.org/10.1258/ijsa.2007.007298

Goldstein, I., Komisaruk, B. R., Pukall, C. F., Kim, N. N., Goldstein, A. T., Goldstein, S. W., Hartzell-Cushanick, R., Kellogg-Spadt, S., Kim, C. W., Jackowich, R. A., Parish, S. J., Patterson, A., Peters, K. M., & Pfaus, J. G. (2021). International Society for the Study of Women’s Sexual Health (ISSWSH) review of epidemiology and pathophysiology, and a consensus nomenclature and process of care for the management of persistent genital arousal disorder/genito-pelvic dysesthesia (PGAD/GPD). Journal of Sexual Medicine, 18(4), 665–697. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsxm.2021.01.172

Hiller, J., & Hekster, B. (2007). Couple therapy with cognitive behavioural techniques for persistent sexual arousal syndrome. Sexual and Relationship Therapy, 22(1), 91–96. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681990600815285

Hofmann, S. G., Sawyer, A. T., Witt, A. A., & Oh, D. (2010). The effect of mindfulness-based therapy on anxiety and depression: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 78(2), 169–183. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0018555

Hryńko, M., Kotas, R., Pokryszko-Dragan, A., Nowakowska-Kotas, M., & Podemski, R. (2017). Persistent genital arousal disorder–a case report. Psychiatria Polska, 51(1), 117–124. https://doi.org/10.12740/PP/64869

Jackowich, R. A., Pink, L., Gordon, A., Poirier, É., & Pukall, C. F. (2018). An online cross-sectional comparison of women with symptoms of persistent genital arousal, painful persistent genital arousal, and chronic vulvar pain. Journal of Sexual Medicine, 15(4), 558–567. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsxm.2018.02.007

Jackowich, R. A., Pink, L., Gordon, A., & Pukall, C. F. (2016). Persistent gential arousal disorder: A review of its conceptualizations, potential origins, impact, and treatment. Sexual Medicine Reviews, 4(4), 329–342. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sxmr.2016.06.003

Jackowich, R. A., & Pukall, C. F. (2020a). Persistent genital arousal disorder: A biopsychosocial framework. Current Sexual Health Reports, 12(3), 127–135. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11930-020-00268-2

Jackowich, R. A., & Pukall, C. F. (2020b). Prevalence of persistent genital arousal disorder in 2 North American samples. Journal of Sexual Medicine, 17(12), 2408–2416. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsxm.2020.09.004

Jette, A. M., Davies, A. R., Cleary, P. D., Calkins, D. R., Rubenstein, L. V., Fink, A., Kosecoff, J., Young, R. T., Brook, R. H., & Delbanco, T. L. (1986). The functional status questionnaire. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 1(3), 143–149. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02602324

Kamatchi, R., & Ashley-Smith, A. (2013). Persistent genital arousal disorder in a male: A case report and analysis of the cause. British Journal of Medical Practitioners, 6(1), a605.

Khoury, B., Lecomte, T., Fortin, G., Masse, M., Therien, P., Bouchard, V., Chapleau, M.-A., Paquin, K., & Hofmann, S. G. (2013). Mindfulness-based therapy: A comprehensive meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 33(6), 763–771. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2013.05.005

Leiblum, S., Seehuus, M., Goldmeier, D., & Brown, C. (2007). Psychological, medical, and pharmacological correlates of persistent genital arousal disorder. Journal of Sexual Medicine, 4(5), 1358–1366. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1743-6109.2007.00575.x

Linehan, M. M. (1993). Dialectical behavior therapy for treatment of borderline personality disorder: Implications for the treatment of substance abuse. NIDA Research Monograph, 137, 201–216.

Linehan, M. M. (2015). DBT: Skills training manual. New York: Guilford Publications.

Linehan, M. M., Armstrong, H. E., Suarez, A., Allmon, D., & Heard, H. L. (1991). Cognitive-behavioral treatment of chronically parasuicidal borderline patients. Archives of General Psychiatry, 48(12), 1060–1064. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.1991.01810360024003

Linehan, M. M., Korslund, K. E., Harned, M. S., Gallop, R. J., Lungu, A., Neacsiu, A. D., McDavid, J., Comtois, K. A., & Murray-Gregory, A. M. (2015). Dialectical behavior therapy for high suicide risk in individuals with borderline personality disorder: A randomized clinical trial and component analysis. JAMA Psychiatry, 72(5), 475–482. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.3039

Linton, S. J., & Fruzzetti, A. E. (2014). A hybrid emotion-focused exposure treatment for chronic pain: A feasibility study. Scandinavian Journal of Pain, 5(3), 151–158. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sjpain.2014.05.008

Martín-Vivar, M., Villena-Moya, A., Mestre-Bach, G., Hurtado-Murillo, F., & Chiclana-Actis, C. (2022). Treatments for persistent genital arousal disorder in women: A scoping review. Journal of Sexual Medicine, 19(6), 961–974. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsxm.2022.03.220

Norman-Nott, N., Wilks, C. R., Hesam-Shariati, N., Schroeder, J., Suh, J., Czerwinski, M., Briggs, N. E., Quidé, Y., McAuley, J., & Gustin, S. M. (2022). The No Worries Trial: Efficacy of online dialectical behaviour therapy skills training for chronic pain (iDBT-Pain) using a single case experimental design. Journal of Pain, 23(4), 558–576. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpain.2021.10.003

Oaklander, A. L., Sharma, S., Kessler, K., & Price, B. H. (2020). Persistent genital arousal disorder: A special sense neuropathy. Pain Reports, 5(1), e801. https://doi.org/10.1097/PR9.0000000000000801

Pease, E. R., Ziegelmann, M., Vencill, J. A., Kok, S. N., Collins, S., & Betcher, H. K. (2022). Persistent genital arousal disorder (PGAD): A clinical review and case series in support of multidisciplinary management. Sexual Medicine Reviews, 10(1), 53–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sxmr.2021.05.001

Pukall, C., Komisaruk, B. R., & Goldberg, A. E. (2022). Persistent genital arousal disorder/genitopelvic dysesthesia. In Y. Reisman, L. Lowenstein, & F. Tripodi (Eds.), Textbook of rare sexual medicine conditions (1st ed., pp. 37–49). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-98263-8

Rashedi, S., Maasoumi, R., Vosoughi, N., & Haghani, S. (2022). The effect of mindfulness-based cognitive-behavioral sex therapy on improving sexual desire disorder, sexual distress, sexual self-disclosure and sexual function in women: A randomized controlled clinical trial. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 48(5), 475–488. https://doi.org/10.1080/0092623X.2021.2008075

Scantlebury, M., & Lucas, R. (2023). Persistent genital arousal disorder: Two case studies and exploration of a novel treatment modality. Women’s Health Reports, 4(1), 84–88. https://doi.org/10.1089/whr.2022.0097

Sullivan, M. J., Bishop, S. R., & Pivik, J. (1995). The pain catastrophizing scale: Development and validation. Psychological Assessment, 7(4), 524–532. https://doi.org/10.1037/1040-3590.7.4.524

Thomtén, J., & Linton, S. J. (2013). A psychological view of sexual pain among women: Applying the fear-avoidance model. Women’s Health, 9(3), 251–263. https://doi.org/10.2217/whe.13.19

Wohl, A., & Kirschen, G. W. (2018). Betrayal of the body: Group approaches to hypo-sexuality for adult female sufferers of childhood sexual abuse. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse, 27(2), 154–160. https://doi.org/10.1080/10538712.2018.1435597

Ziegler, M. G. (2012). Psychological stress and the autonomic nervous system. In D. Robertson, I. Biaggioni, G. Burnstock, P. A. Low, & J. F. R. Paton (Eds.), Primer on the autonomic nervous system (3rd ed., pp. 291–293). Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-386525-0.00061-5

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our gratitude to the patient for her openness, willingness, and bravery; thank you for trusting us to tell your story. We would also like to acknowledge Dr. Melanie Altas for her guidance and support.

Funding

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

Not applicable.

Ethical Approval

This is an observational study. The Vancouver Coastal Health Research Ethics Committee has confirmed that no ethical approval is required.

Consent to Participate

Written informed consent was obtained for the patient presented in this case study. Verbal consent was provided during the final treatment session and written consent for the case study was obtained several months after the treatment had ended.

Consent for Publication

The patient provided written informed consent regarding the submission and publication of this case report. The patient also reviewed the final draft of the manuscript and was given the opportunity to provide feedback prior to the manuscript being submitted for publication.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Merwin, K.E., Brotto, L.A. Psychological Treatment of Persistent Genital Arousal Disorder/Genitopelvic Dysesthesia Using an Integrative Approach. Arch Sex Behav 52, 2249–2260 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-023-02617-3

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-023-02617-3