Abstract

Although the call to understand how sexual behaviors have been impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic has been established as an important area of study, research examining the extent to which gender, sexual attitudes, impulsivity, and psychological distress predicted breaking shelter-in-place (SIP) orders to engage in sexual behaviors with partners residing outside the home is undefined. Obtaining a deeper examination of the variables which predict risky sexual behaviors during SIP has important implications for future research at the intersection of public health, sexuality, and mental health. This study addressed the gap in the literature by considering how partnered sexual behaviors may be used during the COVID-19 pandemic to alleviate stress, as measured by breaking SIP orders for the pursuit of sexual intercourse. Participants consisted of 186 females and 76 males (N = 262) who predominately identified Caucasian/White (n = 149, 57.75%) and heterosexual/straight (n = 190, 73.64%) cultural identities with a mean age of 21.45 years (SD = 5.98, range = 18–65). A simultaneous logistic regression was conducted to examine whether mental health symptoms, sexual attitudes, and impulsivity predicted participants’ decision to break SIP orders to engage in sexual intercourse. Based on our results, breaking SIP orders to pursue sexual activities with partners residing outside the home during the COVID-19 pandemic may be understood as an intentional strategy among men with less favorable birth control attitudes to mitigate the effects of depression. Implications for mental health professionals, study limitations, and future areas of research are additionally provided.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Shortly after the COVID-19 pandemic was declared a national emergency, a total of 42 US states and territories issued mandatory stay-at-home orders between March 1 and May 31, 2020 to reduce population movement and minimize viral spread (Moreland et al., 2020). Social distancing was also a recommended strategy to prevent the spread of COVID-19 (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2020a, b; World Health Organization [WHO], 2020). Given the infectious nature of the virus, sexual contact with individuals residing outside one’s home was discouraged due to the risk of infection through respiratory droplets, blood, and semen from contaminated persons (Li et al., 2020; Turban et al., 2020; Yu et al., 2020). Indeed, guidelines for safer sex practices during social distancing include abstinence, autoeroticism (e.g., masturbation), and noncoital behaviors that do not involve direct contact (e.g., sexting, video calls; Cabello et al., 2020; Lopes et al., 2020; Turban et al., 2020).

The deleterious effects of social isolation on overall well-being became apparent in the months following stay-at-home orders (CDC, 2020a; b; Rosenberg et al., 2020). According to a study of US adults (N = 5,412) conducted in June 2020, approximately 41% of participants reported higher levels of psychological distress characterized by symptoms of anxiety and depression following the pandemic (Czeisler et al., 2020). These stay-at-home orders created new challenges for people who had previously leveraged social engagement and in-person support to mitigate psychological distress. One specific strategy of stress relief is sexual intercourse. The extant body of research identifies partnered sexual activities and achieving orgasm as well-established strategies to reduce stress and promote overall physical and psychological well-being (Berdychevsky & Carr, 2020; Burleson et al., 2007; Ditzen et al., 2007).

The mandatory shelter-in-place (SIP) orders and social distancing recommendations created new challenges for in vivo sexual activities with sexual partners residing outside the home following the global pandemic. The infectious nature of the COVID-19 virus is therefore juxtaposed at the intersection of sexuality and mental health, illuminating a new area of research that necessitates further investigation. The following sections: (1) describe the effects of quarantine on eroticism and sexual behaviors, (2) provide an overview of common predictors of risky sexual behavior, and (3) examine which of these variables were most predictive of sex during SIP orders for men and women.

Effects of Quarantine on Eroticism and Sexual Behaviors

Empirical studies that examined the effects of social isolation, psychological well-being, and pandemic related stress on sexual arousal, satisfaction, and activity have yielded mixed results. Though increased levels of stress, loneliness, and psychological distress following the quarantine have been linked to lower frequency of sexual behaviors (Cocci et al., 2020; Li et al., 2020; Luetke et al., 2020) and decreased levels of sexual arousal and satisfaction (Yuksel & Orgor, 2020), other studies have identified no changes in sexual desire or higher levels of sexual arousal and behaviors following the pandemic (Jacob et al., 2020; Lehmiller et al., 2020). In one study of US adults (N = 1559), nearly half of the participants reported a decline in their overall sex lives, though one in five indicated their sexual repertoire had expanded to include new sexual activities (Lehmiller et al., 2020). Individuals who were younger, lived alone, and experienced higher levels of stress and loneliness were more likely to incorporate novel sexual activities during quarantine such as sexting, trying new sexual positions, filming oneself masturbating, and sharing sexual fantasies (Lehmiller et al., 2020). Higher rates of autoeroticism were also identified in about 40% of adults (N = 1515) during the quarantine in Italy though heightened rates of eroticism did not lead to greater frequency of sexual behaviors (Cocci et al., 2020). Additional research at the intersection of sexuality, intimacy, and COVID-19 have examined patterns of sexual behavior among lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender individuals in the USA (Griffin et al., 2022), perceptions of infectability as a moderator in the association between COVID-19 concern and sexual satisfaction (Hicks et al., 2022), predictors to engage in sexting during shelter-in-place (Thomas et al., 2022), and the impact of COVID-19 on sex and relationships among US undergraduate students (Herbenick et al., 2022). Although one study examined the extent to which Brazilian and Portuguese men who have sex with men (MSM) broke shelter-in-place to engage in casual sex (de Sousa et al., 2021), to the best of the researchers’ knowledge, an empirical investigation of the contributing factors that predicted breaking SIP orders to engage in sexual intercourse with partners residing outside the home in the USA have not yet been conducted.

Effects of Sexual Behaviors on Well-Being and Stress

Following the COVID-19 pandemic, lower levels of well-being and higher rates of psychological distress were reported globally (APA, 2020; Cito et al., 2020; Litam & Lenz, 2021; Rosenberg et al., 2020). These findings come as no surprise given the extant body of research indicating high levels of stress and loneliness may contribute to psychological distress and posttraumatic stress disorder (Cabello et al., 2020; Cao et al., 2020). Engaging in sexual activity may buffer the effects of stress in ways that promote overall well-being and increase mental health (Berdychevsky & Carr, 2020; Muise et al., 2016). Indeed, studies indicated sexual activity and sexual satisfaction improved mood in patients with anxiety and depression (Gagong & Larson, 2011; Smith et al., 2010), contributed to emotional health (Blanchflower & Oswald, 2004; Davison et al., 2009), promoted sleep quality (Kleinstäuber, 2017), increased relaxation (Weeks, 2001), and reduced stress (Charnetski & Brennan, 2001; Ein-Dor & Hirschberger, 2012). The positive effects of partnered sexual interactions compared to orgasm from autoeroticism suggest people may be motivated to pursue sexual experiences with others to improve mood and reduce stress (Burleson et al., 2007). Although engaging in sexual activities amid the COVID-19 pandemic may represent a helpful strategy to promote overall physical and psychological well-being among partnered cohabitating adults (Berdychevsky & Carr, 2020; Cabello et al., 2020; CDC, 2020a, b; Rosenberg et al., 2020), a dearth of research has examined the sexual attitudes and behaviors of individuals who violated SIP orders to pursue partnered sexual experiences and mitigate psychological distress with new partners outside their home.

Effects of Stress on Impulsivity and Sexual Behaviors

Impulsivity is characterized by poor concentration, rapid and careless decision making, and an overall tendency to act without considering the consequences (Quinn & Harden, 2013; Stanford et al., 2009). Understanding the relationship between pandemic related stress, impulsivity, and engaging in sex with partners residing outside the home is especially warranted as impulsive people under stress may be more likely to employ coping responses that provide short term relief (e.g., in vivo dyadic sexual activities with new partners), even when potentially long-term negative consequences are present (e.g., illness and infection; Hull & Sloane, 2004; Magid et al., 2007). The extant body of research has identified a strong relationship between impulsive decision making and high-risk sexual activities (Charnigo et al., 2013; Curry et al., 2018; Hoyle et al., 2000), including sex with strangers (Deckman & DeWall, 2011; Derefinko et al., 2014), multiple sex partners (Derefinko et al., 2014; Dir et al., 2014), and sexually transmitted infections (Dir et al., 2014). According to the developmental asymmetry hypothesis (McCabe et al., 2015), young adults may be most likely to engage in risky sexual behaviors when motivated toward reward-driven behavior paired with an underdeveloped capacity to control their behavior. Although earlier studies have posited that stress may be a motivator for sexual behaviors as a form of mood repair (Bancroft et al., 2003; Graham et al., 2004), no studies have examined this phenomenon within the context of breaking SIP orders to engage in sexual activities with partners residing outside the home during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Effects of Gender on Impulsivity

Earlier studies on the impact of gender on impulsivity have yielded mixed results. Studies on impulsivity may assess impulsive action, which is the inability to inhibit a response (Weinstein & Dannon, 2015). Examples of impulsive action tasks include go/no go exercises and stop tasks. Findings on gender differences in impulsive action have reported contradictory results; whereas men displayed poorer control on go/no go tasks (Liu et al., 2013; Saunders et al., 2008), women displayed poorer control on stop tasks (Morgan et al., 2011). Impulsivity research also considers impulsive choice, which is measured by difficulty in delaying gratification (Weafer & de Wit, 2014). Impulsive choice may be assessed by discounting tasks where individuals can either choose a small reward delivered immediately or a larger reward delivered at less certain time (Richards et al., 1999). A meta-analysis of 33 studies reported a female advantage in the capacity to delay gratification although the effect size was small (Silverman, 2003).

Other findings that examined impulsive choice were mixed and may depend on the presence of hypothetical versus actual rewards (Kirby & Maraković, 1996; Weafer & de Wit, 2014). Specifically, women may demonstrate higher levels of impulsive choice for hypothetical rewards, but men may demonstrate greater impulsive choice for actual rewards (Dittrich & Leipold, 2014; Kirby & Maraković, 1996; Weafer & de Wit, 2014). In a landmark study conducted by Kirby and Maraković (1996), men who believed they would be entered into a lottery and could win money based on their choices discounted more steeply, especially at higher reward values. Similarly, findings postulated by Dittrich and Leipold (2014) indicated men were less able to delay gratification and preferred to receive a sum of money in one month rather than a different amount in 13 months. These findings are often conceptualized through the lens of evolutionary theory which postulates that men may exhibit greater reward sensitivity because their reproductive success is contingent on dominance and mate competition (Dittrich & Leipold, 2014; Weafer & de Wit, 2014).

Effects of Gender on Impulsivity, Sexual Attitudes, and Sexual Behaviors

The extant research on gender’s impact on impulsivity, sexual attitudes, and sexual behaviors creates a narrative wherein lower levels of impulse control, higher levels of sensation seeking (Black et al., 2015; Shulman et al., 2015), higher attitudes of sexual permissiveness and less favorable attitudes toward birth control (Petersen & Hyde, 2011; Temple et al., 1993) among men may lead to higher rates of risk-taking sexual behaviors. In a study of college aged participants (n = 86), men were more likely to prefer more brief, immediate sexual opportunities over longer but more delayed possible sexual encounters (Lawyer et al., 2010).

Based on an extensive review of research, Baumeister et al. (2001) reported men preferred immediate access to sexual opportunities and were significantly less likely than women to tolerate sustained periods of time without a sexual outlet. Furthermore, the purpose of sexual behaviors differed; whereas women reported stress was mitigated through non-sexual outlets (e.g., physical activity), men were vastly more likely to report the usage of sex as a strategy to alleviate sexual tension and stress (Baumeister et al., 2001). These findings partially support a study conducted by Meston and Buss (2007) that indicated men and women (n = 1,549) scored similarly in their reasons for engaging in partnered sexual activities. Although both genders reported physical (e.g., stress reduction, physical desirability, and experience seeking), goal attainment (e.g., resources, social status, and revenge), and insecurity (e.g., to boost self-esteem, pressure, and mate guarding) reasons to engage in sexual intercourse, the relationships between sex for the purpose of stress reduction and goal attainment were strongest among men. These findings combine with earlier studies that posit how men may be more likely to use sex as a form of stress relief (Hill & Preston, 1996) and supplement research that partnered sexual activities among men may serve to reduce stress, modify stress responses, and promote recovery from stress (Ein-Dor & Hirschberger, 2012).

The Current Study

Although the call to understand how sexual behaviors have been impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic has been established as an important area of study (Cabello et al., 2020; Turban et al., 2020), research examining the extent to which biological sex, sexual attitudes, impulsivity, and psychological distress predict breaking SIP orders to engage in sexual behaviors is undefined. The extant body of research has established common predictors of risky sexual activity (Baumeister et al., 2001; Black et al., 2015; Dittrich & Leipold, 2014; Ein-Dor & Hirschberger, 2012; Gagong & Larson, 2011; Meston & Buss, 2007; Shulman et al., 2015; Smith et al., 2010). Though studies have begun to examine the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on married and cohabitating partners (Cito et al., 2020; Jacob et al., 2020; Luetke et al., 2020; Yang & Ma, 2020), empirical analyses on single adults who broke SIP orders to engage in partnered sexual activities remain forthcoming. This study addressed the gap in the literature by attempting to clarify the mixed findings of the impact of biological sex on impulsivity and sexual behaviors while considering how partnered sexual behaviors may be used among men during the COVID-19 pandemic to alleviate stress, as measured by breaking SIP orders for the pursuit of sexual intercourse. The following hypotheses were identified: (1) Mental health symptoms, sexual attitudes, and impulsivity will be statistically significant predictors of participants’ decision to break SIP orders for the purpose of engaging in sexual intercourse; and (2) Predictive models will indicate statistically significant gender differences with proportions of variance explained.

Method

Participants

Participants in this study consisted of a convenience sample of Amazon MTurk workers and undergraduate students who were recruited through the SONA psychology pool at a Midwestern public university in the US MTurk workers were selected for inclusion in this study if they (1) reported their age as 18 years or older, (2) self-identification as single/not partnered, and (3) engaged in sexual activity with partner(s) residing outside the home during SIP at the time of data collection.

Participants were 258 adults (Mage = 21.45, SD = 5.98, range = 18–65 years). Participants identified as female (n = 186, 72.10%) and male (n = 72; 27.90%) who reported Caucasian/White (n = 149, 57.75%), African American/Black (n = 43, 16.67%), Hispanic/Latinx (n = 22, 8.52%), Asian American/Asian (n = 19, 7.36%), Arab American/Arab (n = 12, 4.65%), and Other (n = 13, 5.03%) cultural identities. Participants identified as predominately heterosexual/straight (n = 190, 73.64%) with others indicating bisexual (n = 50, 19.38%), gay or lesbian (n = 6, 2.32%), asexual (n = 5, 1.93%), or other (n = 7, 2.71%) sexual identities. The majority of participants were students (n = 232; 89.92%) who were employed in part-time (n = 117; 45.34%), full-time (n = 49; 18.99%), or under-employed (n = 5; 1.94%) conditions and considered themselves in lower middle (n = 105; 40.70%), upper middle (n = 79; 30.62%), and working (n = 63; 24.41%) social classes. Across biological sex, males tended to be older (t[256] = 4.51, p < .01, df = 0.71, M = 24.91 and 20.11, respectively) and enrolled in college to a lesser proportion (χ2[1] = 29.32, p < .01, V = .33) than females. However, no other statistically significant differences were detected among participant characteristics (see Table 1).

Measures

Demographics and Personal Background

A demographics and background form was created to collect information related to participants’ age, biological sex, race/ethnicity, sexual orientation, social status, employment status, and relationship status. One item was included to assess the frequency in which participants had broken SIP orders to engage in sex or sexual activities with partners residing outside the home (i.e., “During shelter-in-place, how often did you have sex or engage in sexual activities with people residing outside your home?”). Response options included “Never,” “Once,” “Twice,” and a type-in option for “If more than twice, about how many times?”

Mental Health

This Patient Health Questionnaire-4 (PHQ-4; Kroenke et al., 2009) is a brief screener for anxiety and depression, the most prevalent and commonly co-occurring psychiatric syndromes within the United States. The PHQ-4 quantifies the severity and frequency of symptoms during the previous 2 weeks using response categories ranging from 0 (Not at all) to 3 (Nearly every day). The 2-item Anxiety scale evaluates experiences using prompts about “Feeling nervous, anxious or on edge” and “Not being able to stop or control worrying.” The 2-item Depression scale evaluates experiences using prompts “Feeling down, depressed or hopeless” and “Little interest or pleasure in doing things.” For both subscales, higher scores on the PHQ-4 represent greater presence of symptoms. Estimates of internal consistency by Kroenke et al. (2009) and Lenz and Li (2022) reported internal consistency for scores on the PHQ ranging from .80 to .90 with factor invariance across age groups, biological sex, and ethnicities. Internal consistency estimates for anxiety and depression subscales in our study were .83.

Sexual Attitudes

The Brief Sexual Attitudes Scale (BSAS; Hendrick et al., 2006) was used to measure sexual attitudes. Participants respond to 23 items on a 5-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The BSAS has four subscales that measure sexual attitudes related to permissiveness (10 items; “Casual sex is acceptable”), birth control (3 items; “Birth control is part of responsible sexuality”), communion (5 items; “Sex is the closest form of communication between two people”), and instrumentality (5 items; “Sex is primarily a bodily function, like eating”; Hendrick et al., 2006). Hendrick et al. reported reliability of scores for the permissiveness, birth control, communion, and instrumentality subscales were .92, .57, .86, and .75, respectively, which was similar to the values noted with our sample (.92, .76, .75, and .79).

Impulsiveness

The Barratt Impulsiveness Scale (BIS-15; Spinella, 2007) was used to measure impulsiveness in this study. Participants were asked to respond to 15 items on a 4-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (rarely/never) to 4 (almost always). The BSAS-15 consists of three subscales: non-planning impulsivity (6 items; “I say things without thinking”), motor impulsivity (5 items; “I act on the spur of the moment,”, and attentional impulsivity (4 items; “I don’t pay attention; Spinella, 2007). Spinella reported reliability estimates of non-planning impulsivity, motor impulsivity, and attentional impulsivity subscales were within the acceptable range. Internal consistency estimates within our sample were slightly lower for scores on the Non-Planning (.66), Motor (.70), and Attention (.67) subscales.

Procedure

An electronic form of the survey (i.e., demographic form, BSAS, and BIS-15) was created using Qualtrics. Prospective participants were invited to participate in an online survey to better understand attitudes, behaviors, and experiences during COVID-19. Prospective participants were informed that completing the survey was voluntary and they could end the study at any time. Participants were invited to complete the survey through Amazon MTurk, an online platform that allows researchers to obtain geodemographically diverse samples, and through the psychology research pool at a Midwestern public university. MTurk workers received $1.00 as compensation and students earned 0.5 research credits as part of their psychology course requirements. One screening question was included in the MTurk version of the survey as a strategy to monitor data quality (i.e., “What is the monetary value of a quarter + dime + nickel?”). A total of 24 participants submitted incorrect responses and were excluded from the sample and data analysis.

Analytic Strategy

Our analyses were intended to identify the degree that sexual attitudes and impulsivity characteristics predicted breaking SIP orders. Thus, our analytic strategy implemented a simultaneous logistic regression model with PHQ, SAS, and CIS subscales as predictors of self-reported breaking of SIP orders to engage in sexual activities (did or did not).

Preliminary Analyses

Our research design met model assumptions for use of a binary criterion variable and independence of observations. Inspection of descriptive statistics, internal consistency estimates, and bivariate correlations among predictor variables suggested that predictive modeling was justified (see Table 2). Finally, a sample size of 258 with 9 predictor variables yielded an observation/predictor ratio of 28.66 suggesting that our design was sufficiently powered for our omnibus statistical model; however, analyses of gender differences are considered descriptive in nature given the imbalanced proportion of females (n = 186) to males (n = 72) within our sample.

Primary Analysis

We computed separate simultaneous logistic regression models for males and females to identify the statistically significant probability of breaking SIP orders during the COVID-19 pandemic as a function of mental health, sexual attitudes, and impulsivity characteristics. Statistical significance for the χ2 test of logistic regression model fit was evaluated at the .05 level. Additionally, McFadden’s pseudo-R2 (\({R}_{\mathrm{MF}}^{2}\)) was calculated based on the equation \({R}_{\mathrm{MF}}^{2}=1-\frac{{LL}_{\mathrm{mod}}}{{LL}_{0}}\) and used to contrast statistical fit of the predictors within logistic regression models for males and females. This confirmatory fit measure was selected based on its conservative representation and usefulness as a metric to base contrasts across fixed predictor-criterion configurations between different samples (Smith & McKenna, 2013; Veall & Zimmerman, 1996). McFadden (1974) indicated that values closer to 0 indicate a non-fitting predictive model in which the probability of an outcome is effectively equivalent to the null model with only the intercept as a predictor. By contrast, models that feature predictors that increase the probability of an outcome occurring, such as breaking SIP orders to have sex or engage in sexual activities with people residing outside of the home, would have values increasing closer to 1. McFadden noted that \({R}_{\mathrm{MF}}^{2}\) values will inherently be lower than variance-related R2 values in ordinary least squares regression models and suggested that values within the range of 0.20–0.40 represent an excellent fit of contributing predictors within the probability models.

Within statistically significant and well-fitting models, the contributions of individual predictor variables were inferred from inspection of the statistical significance of Z-tests and interpretation of related Odds Ratios (OR). An OR value of 1.00 indicates no relationship between the predictor and criterion; whereas increases and decreases from that value indicate percentages of the probability of a binary outcome occurring.

Results

Breaking Shelter-in-Place Orders

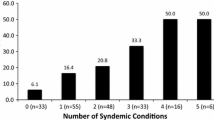

Nearly one in four participants within our sample (n = 69 of 258; 27%) indicated that they had broken SIP orders during the COVID-19 pandemic (see Table 3). Our analyses detected statistically significant differences in proportions of breaking SIP across participants’ reported ethnic identities, χ2(5) = 11.73, p = .04, and the differences were associated with a small effect size, V = .21. No other statistically significant differences in breaking SIP were detected between group proportions based on sexual identity (χ2[4] = 9.72, p = .05, V = .19), gender (χ2[1] = 1.37, p = .24, V = .07), or age group (χ2[2] = 2.21, p = .33, V = .09).

Predictive Associations with Shelter-in-Place

The simultaneous logistic regression analysis for males yielded a statistically significant model for predicting breaking of SIP to have sex or engage in sexual activities with people residing outside of the home, χ2(62) = 33.60, p < .01, \({R}_{\mathrm{MF}}^{2}\) = .37, indicative of an excellent fit for predictors within the model. Within this model, degree of depression symptoms was a statistically significant predictor of participants’ breaking SIP, Z = 2.09, p = .03, OR = 1.89 (CI95 = 1.03, 3.43). This finding suggests that participants who reported more depression symptoms were about 89% more likely to break SIP orders than those with lower scores on the PHQ-4 Depression subscale. Attitudes about birth control were a statistically significant predictor of participants’ breaking SIP, Z = − 2.54, p = .01, OR = 0.55 (CI95 = 0.35, 0.87). This finding suggests that participants with less favorable attitudes toward birth control were about 45% more likely to break SIP orders than those with more favorable attitudes. Finally, non-planning type impulsivity was also a statistically significant predictor, Z = − 2.31, p = .02, OR = 0.56 (CI 95 = 0.35, 0.91). This finding suggests that participants who tended to act without planning were about 44% less likely to break SIP orders. No other scores related to mental health, sexual attitudes, or impulsivity were identified as statistically significant predictors of breaking SIP among males (see Table 4).

The simultaneous logistic regression analysis for females did not yield a statistically significant model for predicting breaking of SIP to have sex or engage in sexual activities with people residing outside of the home, χ2(176) = 16.21, p = .07, \({R}_{\rm MF}^{2}\) = .07, indicative of a poor fit for predictors within the model.

Discussion

The aim of the present study was to examine sex differences in psychological distress, sexual attitudes, and impulsivity as possible predictors of whether participants had broken SIP orders to engage in sexual activities with partners residing outside the home during COVID-19. Though this behavior may relieve stress, it may be considered a risky sexual activity because of increased risk of contracting and spreading COVID-19. Our results add to the extant research on impulsivity and high-risk sexual activities (Charnigo et al., 2013; Curry et al., 2018; Deckman & DeWall, 2011; Derefinko et al., 2014; Hoyle et al., 2000), and sex during the COVID-19 pandemic (Cocci et al., 2020; Jacob et al., 2020; Lehmiller et al., 2020; Li et al., 2020; Luetke et al., 2020) while contributing new findings that may serve as a starting point for understanding the functional purpose of partnered sexual activities as a form of mood repair among men during the COVID-19 pandemic. It is plausible that breaking SIP orders to pursue sexual activities with partners residing outside the home during the COVID-19 pandemic may be understood as an intentional strategy to mitigate the effects of depression among men with less favorable attitudes toward birth control. Our functional hypothesis is supported by evolutionary perspectives (Dittrich & Leipold, 2014; Weafer & de Wit, 2014), findings that less favorable attitudes toward birth control among men were associated with riskier sexual behaviors (Temple et al., 1993), and research that established sex as a strategy to mitigate the effects of depression (Gagong & Larson, 2011; Smith et al., 2010).

Based on our study, men who were more likely to engage in non-planning type impulsivity were less likely to break SIP to engage in sexual activities with partners residing outside their home. This result is inconsistent with previous studies that identified a strong association between impulsive decision making and high-risk sexual activities (Charnigo et al., 2013; Curry et al., 2018; Hoyle et al., 2000), and challenge aspects of the asymmetry hypothesis (McCabe et al., 2015), in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. Rather than engaging in sex as a consequence of lack of planning, it can be conjectured that male participants may have pursued sexual activities with partners residing outside the home after intentionally weighing their options and determining that the benefits of sexual intercourse outweighed the potential costs of breaking SIP. This hypothesis is in line with earlier studies that posited how high levels of distress may motivate sexual interactions to repair mood (Bancroft et al., 2003; Graham et al., 2004) and findings that men demonstrated greater levels of impulsive choice when actual rewards were perceived (Dittrich & Leipold, 2014; Kirby & Maraković, 1996; Weafer & de Wit, 2014). Taken together, our results indicate that breaking SIP orders to engage in sexual activities with partners outside the home may represent an intentional and potentially risky strategy to mitigate feelings of depression or hopelessness among men, even at the expense of potential illness and contagion. It is possible that the men in our study believed the immediate gratification associated with partnered sexual activities represented a salient enough reward (e.g., decreased levels of depression) that outweighed the risk of possible consequences. This hypothesis is consistent with evolutionary theory which asserts that men may exhibit greater reward sensitivity compared to women because their reproductive success is contingent on mate competition (Dittrich & Leipold, 2014; Weafer & de Wit, 2014). In the context of evolutionary theory, breaking SIP orders to engage in sexual intercourse with partners residing outside the home may serve two functions- repairing mood and promoting reproductive success in a pandemic.

Our finding that men who endorsed less favorable attitudes toward birth control may have intentionally leveraged sexual intercourse with partners outside the home as a strategy to mitigate the deleterious effects of depression is consistent with earlier studies. Specifically, studies on related topics have reported that men with less favorable birth control attitudes engaged in risky sexual behaviors (Temple et al., 1993). Additionally, the extant body of research has positioned physical touch and achieving orgasm as well-established strategies to improve overall well-being, reduce stress, and decrease symptoms of depression (Berdychevsky & Carr, 2020; Burleson et al., 2007; Charnetski & Brennan, 2001; Ditzen et al., 2007; Gagong & Larson, 2011; Muise et al., 2016; Smith et al., 2010), especially among men (Baumeister et al., 2001; Ein-Dor & Hirschberger, 2012; Meston & Buss, 2007). The findings of our study supplement existing research that examined the extent to which Brazilian and Portuguese MSM broke shelter-in-place to engage in casual sex (de Sousa et al., 2021). According to findings from de Sousa et al. (2021), Brazilian men who engaged in group sex, lived in urban areas, believed that SIP had a high impact on their daily lives, and reported casual partners were more likely to break SIP orders for sex. In the same study, Portuguese men who used Facebook to find partners, who did not decrease amount of partners, who usually found partners in physical venues, who felt that isolation had a high impact on their daily lives, and who reported HIV-positive serostatus were more likely to break SIP for sex (de Sousa et al., 2021). Based on a review of the existing literature, our study is the first to conceptualize how breaking SIP orders in the USA in pursuit of sexual intercourse with partners residing outside the home may represent a short-term coping strategy among men with low birth control attitudes to intentionally mitigate the deleterious effects of depression.

Implications for Mental Health Professionals

Based on our results, participants who reported more depression symptoms, endorsed less favorable birth control attitudes, and tended to act without planning were significantly more likely to break SIP orders to engage in sexual activities with partners residing outside the home. Mental health professionals may incorporate these findings into their practice by helping clients mitigate depression symptoms, address unhelpful attitudes related to birth control, and facilitate strategies to address aspects of impulsivity. Clinicians working with clients who have demonstrated histories of non-planning type impulsivity may support clients by engaging in discussions of harm reduction and incorporating strategies to help clients engage in delay discounting. For example, mental health professionals may help clients complete a cost benefits analysis of quarantining for 2 weeks prior to in vivo sexual activities with new partners to minimize illness and contagion. Clients may also participate in sex education topics that address birth control attitudes. For example, clients may be encouraged to practice safer sex behaviors such as condom use, video messages, and sexting.

Given that higher rates of depression may predict breaking SIP to engage in sexual activities with partners outside the home, it may behoove mental health professionals to facilitate conversations with clients about the benefits of autoeroticism and orgasm to decrease depression symptoms. Indeed, practicing autoeroticism may represent enjoyable and socially distant strategies to procure the benefits of orgasm while limiting exposure to new partners. For example, mental health clinicians can explore how purchasing and/or incorporating adult lifestyle products may enhance sexual enjoyment and promote psychological well-being. This recommendation is in line with the guidelines for safer sex practices during social distancing amid the COVID-19 pandemic (Cabello et al., 2020; Lopes et al., 2020; Turban et al., 2020).

Limitations and Recommendations for Future Research

First, the use of self-report surveys may pose a threat to internal validity as it is may be more susceptible to social desirability bias when compared to more objectively verifiable measurement approaches such as observation or contemporaneous activity recording. Future area of study on topics related to sex and sexuality may benefit from including a measure, such as the Marlowe-Crowne Social Desirability Scale (Crowne & Marlowe, 1960), to screen out responses that reflect high amounts of social desirability bias. Readers must be judicious about generalizing these findings due to the use of a convenience sample. Our study used a cross-sectional and retrospective design that may limit the causality and directionality of our findings as well as potentially result in common methods variance. Future studies on this topic would benefit from qualitative investigations, longitudinal studies, and other research designs that may assess the direction of causality. Another study limitation is related to our sample, which predominantly consisted of young adults in their 20s. Given the lower risk of adverse health outcomes from COVID-19 in younger groups compared to older populations, future studies would benefit from examining how risk evaluation and perception of COVID-19 severity across age groups may have impacted breaking SIP to engage in sexual behaviors with non-cohabitating partners. Additionally, despite CDC and WHO recommendations to SIP, our analyses may be limited because political affiliation was not measured and thus not controlled for in our study. Future studies may consider how political affiliation may impact adherence to CDC and WHO guidelines. Next, our study may have overlooked important potential factors such as relationship status and attachment style. For example, our study did not consider whether participants broke SIP to engage in sex with non-cohabitating partners nor did we examine the influence of attachment style on non-planning impulsivity type. Future studies are therefore needed to examine the relationship between mental health, attachment styles, cohabitating status, and relationship status.

Conclusion

Breaking SIP orders to engage in sexual activities with partners residing outside the home during the COVID-19 pandemic may represent an intentional strategy among men who have less favorable birth control attitudes to mitigate the effects of depression. Our findings supplement earlier studies on the relationship between biological sex, impulsivity, and sexual behaviors while contributing new knowledge at the intersection of mental health and sexual behaviors in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. Mental health professionals may help clients engage in delay discounting, mitigate depression symptoms, and address birth control attitudes. Future studies may consider the influence of adult attachment styles and partnership status to contribute to the paucity of research on the possible protective effects of relationship status on mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic.

References

American Psychiatric Association. (2020). New poll: COVID-19 impacting mental well-being: Americans feeling anxious, especially for loved ones; older adults are less anxious. https://www.psychiatry.org/news-room/news-releases/new-poll-covid-19-impacting-mental-well-being-americans-feeling-anxious-especially-for- loved-ones-older-adults-are-less-anxious

Bancroft, J., Janssen, E., Strong, D., Carnes, L., Vukadinovic, Z., & Long, J. S. (2003). The relation between mood and sexuality in heterosexual men. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 32(3), 217–230. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1023409516739

Baumeister, R. F., Catanese, K. R., & Vohs, K. D. (2001). Is there a gender difference in strength of sex drive? Theoretical views, conceptual distinctions, and a review of relevant evidence. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 5(3), 242–273. https://doi.org/10.1207/S1532795PSPR0503_5

Berdychevsky, L., & Carr, N. (2020). Innovation and impact of sex as leisure in research and practice: Introduction to the special issue. Leisure Sciences, 42(3–4), 255–274. https://doi.org/10.1080/01490400.2020.1714519

Black, A. C., McMahon, T. J., Potenza, M. N., Fiellin, L. E., & Rosen, M. I. (2015). Gender moderates the relationship between impulsivity and sexual risk-taking in a cocaine-using psychiatric outpatient population. Personality and Individual Differences, 75, 190–194. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2014.11.035

Blanchflower, D. G., & Oswald, A. J. (2004). Money, sex and happiness: An empirical study. Scandanavian Journal of Economics, 106(3), 393–415

Burleson, M. H., Trevathan, W. R., & Todd, M. (2007). In the mood for love or vice versa? Exploring the relations among sexual activity, physical affection, affect, and stress in the daily lives of mid-aged women. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 36(3), 357–368. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-006-9071-1

Cabello, F., Sánchez, F., Farré, J. M., & Montejo, A. L. (2020). Consensus on recommendations for safe sexual activity during the COVID-19 coronavirus pandemic. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 9(7), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm9072297

Cao, W., Fang, Z., Hou, G., Han, M., Xu, X., Dong, J., & Zheng, J. (2020). The psychological impact of the COVID-19 epidemic on college students in China. Psychiatry Research, 287, 112934. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112934

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020a). Mental health: Household Pulse Survey. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/covid19/pulse/mental-health.htm

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020b). Social distancing. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/prevent-getting-sick/social-distancing.html

Charnetski, C. J., & Brennan, F. X. (2001). Feeling good is good for you: How pleasure can boost your immune system and lengthen your life. Rodale Press.

Charnigo, R., Noar, S. M., Garnett, C., Crosby, R., Palmgreen, P., & Zimmerman, R. S. (2013). Sensation seeking and impulsivity: Combined associations with risky sexual behavior in a large sample of young adults. Journal of Sex Research, 50(5), 480–488. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2011.652264

Cito, G., Micelli, E., Cocci, A., Polloni, G., Russo, G. I., Coccia, M. E., Simoncini, T., Carini, M., Minervini, A., & Natali, A. (2020). The impact of the COVID-19 quarantine on sexual life in Italy. Urology, 147, 37–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.urology.2020.06.101

Cocci, A., Giunti, G., Tonioni, C., Cacciamanin, G., Tellini, R., Polloni, G., Cito, G., Presicce, F., Di Mauro, M., Minervini, A., Cimono, S., & Russo, G. I. (2020). Love at the time of the Covid-19 pandemic: Preliminary results of an online survey conducted during the quarantine in Italy. Sexual Medicine Journal, 32, 556–557. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41443-020-0305-x

Crowne, D. P., & Marlowe, D. (1960). A new scale of social desirability independent of psychopathology. Journal of Consulting Psychology, 24(4), 349–354. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0047358

Curry, I., Luk, J. W., Trim, R. S., Hopfer, C. J., Hewitt, J. K., Stallings, M. C., Brown, S. A., & Wall, T. L. (2018). Impulsivity dimensions and risky sex behaviors in an at-risk young adult sample. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 47(2), 529–536. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-017-1054-x

Czeisler, M. É., Lane, R. I., Petrosky, E., Wiley, J. F., Christensen, A., Njal, R., Weaver, M. D., Robbins, R., Facer-Childs, R., Barger, L. K., Czeisler, C. A., Howard, M. E., & Rajaratnam, S. M. W. (2020). Mental health, substance use, and suicidal ideation during the COVID-19 pandemic-United States, June 24–30, 2020. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 69(32), 1049–1057. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6932a1

Davison, S. L., Bell, R. J., LaChina, M., Holden, S. L., & Davis, S. R. (2009). The relationship between self-reported sexual satisfaction and general well-being in women. Journal of Sexual Medicine, 6(10), 2690–2697. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1743-6109.2009.01406.x

de Sousa, A. F. L., de Oliveira, L. B., Queiroz, A. A. F. L. N., de Carvalho, H. E. F., Schneider, G., Camargo, E. L. S., de Araújo, T. M. E., Brignol, S., Mendes, I. A. C., Fronteira, I., & McFarland, W. (2021). Casual sex among men who have sex with men (MSM) during the period of sheltering in place to prevent the spread of COVID-19. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(6), 3266. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph180632676

Deckman, T., & DeWall, C. N. (2011). Negative urgency and risky sexual behaviors: A clarification of the relationship between impulsivity and risky sexual behavior. Personality and Individual Differences, 51(5), 674–688. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2011.06.004

Derefinko, K. J., Peters, J. R., Eisenlohr-Moul, T. A., Walsh, E. C., Adams, Z. W., & Lynam, D. R. (2014). Relations between trait impulsivity, behavioral impulsivity, physiological arousal, and risky sexual behavior among young men. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 42(6), 1149–1158. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-014-0327-x

Dir, A. L., Coskunnipar, A., & Cyders, M. A. (2014). A meta-analytic review of the relationship between adolescent risky sexual behavior and impulsivity across gender, age, and race. Clinical Psychology Review, 34(7), 551–562. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2014.08.004

Dittrich, M., & Leipold, K. (2014). Gender differences in time preferences. Economics Letters, 122(3), 413–415. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econlet.2014.01.002

Ditzen, B., Neumann, I. D., Bodenmann, G., von Dawans, B., Turner, R. A., Ehlert, U., & Heinrichs, M. (2007). Effects of different kinds of couple interaction on cortisol and heart rate responses to stress in women. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 32(5), 565–574. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psyneuen.2007.03.011

Ein-Dor, T., & Hirschberger, G. (2012). Sexual healing: Daily diary evidence that sex relieves stress for men and women in satisfying relationships. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 29(1), 126–139. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407511431185

Gagong, K., & Larson, E. (2011). Intimacy and belonging: The association between sexual activity and depression among older adults. Society and Mental Health, 1, 153–172. https://doi.org/10.1177/2156869311431612

Graham, C. A., Sanders, S. A., Milhausen, R. R., & McBride, K. R. (2004). Turning on and turning off: A focus group study of the factors that affect women’s sexual arousal. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 33(6), 527–538. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:ASEB.0000044737.62561.fd

Griffin, M., Jaiswal, J., Martino, R. J., LoSchiavo, C., Comer-Carruthers, C., Krause, K. D., Stults, C. B., & Halkitis, P. N. (2022). Sex in the time of COVID-19: Patterns of sexual behavior among LGBT+ individuals in the U.S. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 51, 287–301. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-022-02298-4

Hendrick, C., Hendrick, S. S., & Reich, D. A. (2006). The Brief Sexual Attitudes Scale. Journal of Sex Research, 43(1), 76–86. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224490609552301

Herbenick, D., Hensel, D. J., Eastman-Mueller, H., Beckmeyer, J., Fu, T.-C., Guerra-Reyes, L., & Rosenberg, M. (2022). Sex and relationships pre- and early- COVID-19 pandemic: Findings from a probability sample of U.S. undergraduate students. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 51, 181–195. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-021-02265-5

Hicks, L. L., Meltzer, A. L., French, J. E., Altgelt, E., Turner, J. A., & McNulty, J. K. (2022). Perceptions of infectability to disease moderate the association between daily concerns about contracting COVID-19 and satisfaction with sex. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 51, 197–202. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-021-02076-8

Hill, C. A., & Preston, L. K. (1996). Individual differences in the experience of sexual motivation: Theory and measurement of dispositional sexual motives. Journal of Sex Research, 33(1), 27–45. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499609551812

Hoyle, R. H., Fejfar, M. C., & Miller, J. D. (2000). Personality and sexual risk taking: A quantitative review. Journal of Personality, 68(6), 1203–1231. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-6494.00132

Hull, J. G., & Sloane, L. B. (2004). Alcohol and self-regulation. In R. F. Baumeister & K. D. Vohs (Eds.), Handbook of self-regulation: Research, theory, and applications (pp. 466–491). Guilford Press.

Jacob, L., Smith, L., Butler, L., Barnett, Y., Grabovac, I., McDermott, D., Armstrong, N., Yakkundi, A., & Tully, M. (2020). COVID-19 social distancing and sexual activity in a sample of the British public. Journal of Sexual Medicine, 17(7), 1229–1236. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsxm.2020.05.001

Kirby, K. N., & Maraković, N. N. (1996). Delay-discounting probabilistic rewards: Rates decrease as amounts increase. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 3(1), 100–104. https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03210748

Kleinstäuber, M. (2017). Factors associated with sexual health and well being in older adulthood. Current Opinion in Psychiatry, 30(5), 358–368.

Kroenke, K., Spitzer, R. L., Williams, J. B. W., & Löwe, B. (2009). An ultra-brief screening scale for anxiety and depression: The PHQ-4. Psychosomatics, 50(6), 613–621. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.psy.50.6.613

Lawyer, S. R., Williams, S. A., Prihodova, T., Rollins, J. D., & Lester, A. C. (2010). Probability and delay discounting of hypothetical sexual outcomes. Behavioral Processes, 84(3), 687–692. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beproc.2010.04.002

Lehmiller, J. J., Garcia, J. R., Gesselman, A. N., & Mark, K. P. (2020). Less sex, but more sexual diversity: Changes in sexual behavior during the COVID-19 coronavirus pandemic. Leisure Sciences: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 43(1–2), 295–304. https://doi.org/10.1080/01490400.2020.1774016

Lenz, A. S., & Li, C. (2022). Evidence for measurement invariance and psychometric reliability for scores on the PHQ-4 from a rural and predominantly Hispanic community. Measurement and Evaluation in Counseling and Development, 55, 17–29. https://doi.org/10.1080/07481756.2021.1906157

Li, D., Jin, M., Bao, P., Zhao, W., & Zhang, S. (2020). Clinical characteristics and results of semen tests among men with coronavirus disease 2019. JAMA Network Open, 3(5), e208292. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.8292

Litam, S. D. A., & Lenz, A. S. (2021). Moderation of attachment on association between relationship status and depression. Journal of Counseling and Development, 100(2), 194–204.

Liu, T., Xiao, T., & Shi, J. (2013). Response inhibition, preattentive processing, and sex differences in young children: An event-related potential study. Neuro Report Journal, 24(3), 126–130. https://doi.org/10.1097/WNR.0b013e32835d846b

Lopes, G. P., Vale, F. B. C., Vieira, I., da Silva Filho, A. L., Abuhid, C., & Geber, S. (2020). COVID-19 and sexuality: Reinventing intimacy [Letter to the Editor]. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 49, 2735–2738. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508/020-01796-7

Luetke, M., Hensel, D., Herbenick, D., & Rosenberg, M. (2020). Romantic relationship conflict due to the COVID-19 pandemic and changes in intimate and sexual behaviors in a nationally representative sample of American adults. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 46(8), 747–762.

Magid, V., MacLean, M. G., & Colder, C. R. (2007). Differentiating between sensation seeking and impulsivity through their mediated relations with alcohol use and problems. Addictive Behaviors, 32(10), 2046–2061. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.01.015

McCabe, C. J., Louie, K. A., & King, K. M. (2015). Premeditation moderates the relation between sensation seeking and risky substance use among young adults. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 29(3), 753–765. https://doi.org/10.1037/adb0000075

McFadden, D. (1974). Conditional logit analysis of qualitative choice behavior. In P. Zarembka (Ed.), Frontiers in econometrics (pp. 105–142). Academic Press.

Meston, C. M., & Buss, D. M. (2007). Why humans have sex. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 36, 477–507. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-007-9175-2

Moreland, A., Herlihy, C., Tynan, M. A., Sunshine, G., McCord, R. F., Hilton, C., Poovey, J., Werner, A. K., Jones, C. D., Fulmer, E. B., Gundlapalli, A. V., Strosnider, H., Potvien, A., García, M. C., Honeycutt, S., & Baldwin, G. (2020). Timing of state and territorial COVID-19 stay-at-home orders and changes in population movement-United States, March 1–May 31, 2020. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 69(35), 1198–1203.

Morgan, J. E., Gray, N. S., & Snowden, R. J. (2011). The relationship between psychopathy and impulsivity: A multi-impulsivity measurement approach. Personality and Individual Differences, 51(4), 429–434. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2011.03.043

Muise, A., Schimmack, U., & Impett, E. A. (2016). Sexual frequency predicts greater well-being, but more is not always better. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 7(4), 295–302. https://doi.org/10.1177/1948550615616462

Petersen, J. L., & Hyde, J. S. (2011). A meta-analytic review of research on gender differences in sexuality, 1993–2007. Psychological Bulletin, 136(1), 21–38. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0017504

Quinn, P. D., & Harden, K. P. (2013). Differential changes in impulsivity and sensation seeking and the escalation of substance use from adolescence to early adulthood. Development and Psychopathology, 25(1), 223–239. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579412000284

Richards, J. B., Zhang, L., Mitchell, S. H., & de Wit, H. (1999). Delay or probability discounting in a model of impulsive behavior: Effect of alcohol. Journal of Experimental Analysis of Behavior, 71(2), 121–143. https://doi.org/10.1901/jeab.1999.71-121

Rosenberg, M., Luetke, M., Hensel, D., Kianersi, S., & Herbenick, D. (2020). Depression and loneliness during COVID-19 restrictions in the United States, and their associations with frequency of social and sexual connections. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 56(7), 1221–1232. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.05.18.20101840

Saunders, B., Farag, N., Vincent, A. S., Collins, F. L., Sorocco, K. H., & Lavallo, W. R. (2008). Impulsive errors on a go-no go reaction time task: Disinhibitory traits in relation to a family history of alcoholism. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 32, 888–894. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1530-0277.2008.00648.x

Shulman, E. P., Harder, K. P., Chein, J. M., & Steinberg, L. (2015). Sex differences in the developmental trajectories of impulse control and sensation-seeking from early adolescence to early adulthood. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 44(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-017-0116-9

Silverman, I. W. (2003). Gender differences in delay of gratification: A meta-analysis. Sex Roles, 49(9), 451–463. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1025872421115

Smith, J. F., Breyer, B. N., Eisenberg, M. L., Sharlip, I. D., & Shindel, A. W. (2010). Sexual function and depressive symptoms among male North American medical students. Journal of Sexual Medicine, 7(12), 3909–3917. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1743-6109.2010.02033.x

Smith, T. J., & McKenna, C. M. (2013). A comparison of logistic regression pseudo R2 indices. Multiple Linear Regression Viewpoints, 39(2), 17–26.

Spinella, M. (2007). Normative data and a short form of the Barratt Impulsiveness Scale. International Journal of Neuroscience, 117(3), 359–368. https://doi.org/10.1080/002707450600588881

Stanford, M. S., Mathias, C. W., Doughtery, D. M., Lake, S. L., Anderson, N. E., & Patton, J. H. (2009). Fifty years of the Barret Impulsiveness Scale: An update and review. Personality and Individual Differences, 47(5), 385–395. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2009.04.008

Temple, M., Leigh, B., & Schafer, J. (1993). Unsafe sexual behavior and alcohol use at the event level. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 6(4), 393–401.

Thomas, M. F., Binder, A., & Mattes, J. (2022). Love in the time of corona: Predicting willingness to engage in sexting during the first COVID-19-related lockdown. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 51, 157–168. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-022-02290w

Turban, J. L., Keuroghlian, A. S., & Mayer, K. H. (2020). Sexual health in the SARS-CoV-2 era. Annals of Internal Medicine, 173(5), 387–389. https://doi.org/10.7326/M20-2004

Veall, M. R., & Zimmerman, K. F. (1996). Pseudo-R2 measures for some common limited dependent variable models. Journal of Economic Surveys, 10(3), 241–260. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6419.1996.tb00013.x

Weafer, J., & de Wit, H. (2014). Sex differences in impulsive action and impulsive choice. Addictive Behaviors, 39(11), 1573–1579. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2013.10.033

Weeks, D. J. (2001). Sex for the mature adult: Health, self-esteem and countering ageist stereotypes. Sexual and Relationship Therapy, 17(3), 231–240. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681990220149031

Weinstein, A., & Dannon, P. (2015). Is impulsivity a male trait rather than a female trait? Exploring the sex differences in impulsivity. Current Behavioral Neuroscience Reports, 2, 9–14. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40473-015-0031-8

World Health Organization. (2020). Considerations in adjusting public health and social measures in the context of COVID-19: Interim guidance. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/331773

Yang, H., & Ma, J. (2020). How an epidemic outbreak impacts happiness: Factors that worsen (vs. protect) emotional well-being during the coronavirus pandemic. Psychiatry Research, 289, 113045–113045. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psy-chres.2020.113045

Yu, F., Yan, L., Wang, N., Yang, S., Wang, L., Tang, Y., Gao, G., Wang, S., Ma, C., Xie, R., Wang, F., Tan, C., Zhu, L., Guo, Y., & Zhang, F. (2020). Quantitative detection and viral load analysis of SARS-CoV-2 in infected patients. Clinical Infectious Diseases, 71(15), 793–798. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciaa345

Yuksel, B., & Orgor, F. (2020). Effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on female sexual behavior. International Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics, 150(1), 98–102. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijgo.13193

Funding

The authors have not disclosed any funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

We have no known conflicts of interest to disclose.

Ethical approval

Researchers obtained university Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval before data collection.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Litam, S.D.A., Lenz, A.S. Evidence for Sex Differences in Depression, Sexual Attitudes, and Impulsivity as Predictors of Breaking Shelter-in-Place Orders During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Arch Sex Behav 52, 2527–2538 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-023-02609-3

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-023-02609-3