Abstract

Ideal friend and romantic partner characteristics related to self-perceived characteristics have been investigated in typically developing (TD) individuals, but not in individuals with autism spectrum disorder (ASD). Considering the autistic symptoms and challenges, investigating these concepts in autistic individuals is relevant. Given the lack of consensus, identity-first (“autistic person”) and person-first (“person with autism”) language are mixed throughout, to cover all preferences. This study explored (1) the association between self-perceived characteristics and desires in a friend/romantic partner, as well as (2) compare two groups (ASD and TD) in their desires for a friend/romantic partner. Two matched groups (ASD and TD) of 38 male adolescents (age 14–19 years) reported on the desire for nine characteristics (i.e., funny, popular, nice, cool, smart, trustworthy, good looking, similar interests, and being rich) in a friend/partner, and to what extent they felt they themselves possessed seven characteristics (i.e., funny, popular, nice, cool, smart, trustworthy, and good looking). Results showed both groups sought a friend and partner similar to themselves on intrinsic characteristics (e.g., trustworthiness), but less similar on extrinsic and social status characteristics (e.g., being less cool and popular). Particularly intrinsic characteristics, more than extrinsic and social status characteristics, were valued in both partners and friends, regardless of group. No significant differences were found between groups concerning to what extent characteristics were desired. Overall, adolescents with ASD desire similar characteristics as TD adolescents in their potential romantic partners and friends. There is some indication that the match between self-perception and desired characteristics is different.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Individuals with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) often have difficulties developing and maintaining friendships and romantic relationships (APA, 2013; Petrina et al., 2014).Footnote 1 A long-held belief was that they preferred solitude and had no interest in social or intimate relationships (Ballan, 2012; Kanner, 1943). However, several studies have underlined that individuals with ASD have the desire for friendship and romantic relationships (Bauminger & Kasari, 2000; Calder et al., 2013; Cheak-Zamora et al., 2019; Hellemans et al., 2010; Henault, 2006; Stokes et al., 2007). Some research has found that, not a limited social motivation and desire, but rather difficultly to initiate and maintain romantic relationships exists for many adults with ASD (Strunz et al., 2017). Such issues may also exist in adolescents with ASD. Despite several successful evidence-based programs (e.g., Dekker et al., 2019; Laugeson et al., 2012; Visser et al., 2017) that aim to improve the social knowledge and skills that individuals with ASD have, it seems that in daily life, making and maintaining friendships or romantic relationships remain a challenge (Bauminger & Kasari, 2000; Church et al., 2000; Finke, 2016; May et al., 2017; Petrina et al., 2014; Rowley et al., 2012). One explanation for this is that, despite improved social communicational skills, there might be a mismatch between self-perceived (own) characteristics, preferences, attitudes, with desires about a potential friend or romantic partner in individuals with ASD (Finke, 2016).

The interplay between self-perceived own characteristics and desired characteristic in a friend or romantic partner is currently unknown in individuals with ASD. Research in typically developing (TD) individuals found that desired characteristics in a friend or a partner are related to self-perceived characteristics (i.e., the characteristics a person beliefs to possess) (Brown & Brown, 2015; Campbell et al., 2001; Kenrick et al., 1993; Sprecher & Regan, 2002). These studies showed that people who rate themselves highly as a potential friend or partner also have higher demands in what they desire in various relational partners (e.g., friendship or romantic relationship) (e.g., Regan et al., 2000).

Regardless of self-perceived characteristics, there are certain characteristics generally desired more in friendships and/or romantic relationships. Commonly listed desired friendship qualities mentioned by adolescents with ASD and TD adolescents entail; trustworthiness, kindness, companionship, and having similar interests (Locke et al., 2010; Petrina et al., 2014). In a qualitative study in adolescents and young adults with ASD ideal partners were described with characteristics like caring, kind, smart, romantic, and funny, whilst physical attractiveness was described as less important (Cheak-Zamora et al., 2019). In the TD population, three major components have been underlined as desirable in a romantic partner; i.e., warmth/trustworthiness, attractiveness/vitality, and status/resources (Fletcher et al., 2004). In TD adults, intrinsic characteristics (e.g., warmth, honesty, and intelligence) are desired to a greater degree than extrinsic characteristics (e.g., wealth and physical attractiveness) in romantic partners (Figueredo et al., 2006; Regan et al., 2000). Similarly, in TD adolescents extrinsic characteristics (e.g., physical attractiveness) were found to be more important for short-term sexual partners, and intrinsic characteristics (e.g., intelligence and humor) more so for long-term romantic partners (Regan & Joshi, 2003).

Friendship and romantic relationships have been studied in ASD populations; however, desired or idealized characteristics were usually not the focus. Most of the studies on friendships in individuals with ASD have investigated how individuals with ASD define friendship (i.e., what makes someone a friend; e.g., Petrina et al., 2014), whether they have friends (e.g., Rowley et al., 2012) and the quality of the friendships they have (e.g., Calder et al., 2013; Kuo et al., 2013; Locke et al., 2010). Research regarding romantic relationships in individuals with ASD has followed a similar pattern, with the focus on the existence of (e.g., Byers et al., 2013a; Fernandes et al., 2016; May et al., 2017; Strunz et al., 2017) and satisfaction with romantic relationships (e.g., Strunz et al., 2017). Although one study did find some characteristics to be mentioned as ideal (Cheak-Zamora et al., 2019), it remains unclear which characteristics are desired in their potential friends and romantic partners by adolescents with ASD, and if and how this may differ from TD adolescents.

The studies on friendships and romantic relationships in individuals with ASD have found that gender is related to the outcomes. Friendship studies have found that males with ASD have less social motivation (Sedgewick et al., 2016), less conflict experiences (Sedgewick et al., 2019b), less social skills (Head et al., 2014), different friendship understanding (Płatos & Pisula, 2021), and different activity patterns with friends (i.e., males more video gaming, females more conversations) (Kuo et al., 2013). Also, in romantic relationships gender has been linked to differences in sexual well-being in individuals with ASD. For example, males with ASD reported more dyadic arousability, greater desire, and greater sexual satisfaction (Byers et al., 2013b), more desire for sexual activity, less sexual anxiety and less sexual problems (Byers et al., 2013a), and less sexual orientation diversity (Dewinter et al., 2017; Turner et al., 2017). There is mixed evidence of how gender may be related to dyadic romantic or sexual relationships, with some finding men with ASD to have a greater engagement (Pecora et al., 2016) and others that males with ASD are less likely to be in a relationship (Turner et al., 2017). Given the gender differences, it is relevant to account for gender in research into friendships and romantic partners, as potentially it may translate to self-perceived characteristics and desired characteristics.

In addition, much of the research on friendships and romantic relationships was performed in primarily adult or clinical samples with ASD (May et al., 2017), while few have focused specifically on adolescents (e.g., Cheak-Zamora et al., 2019; Dekker et al., 2017; Dewinter et al., 2017). This despite the fact that in adolescence different characteristics may become more important in friendships; for example, loyalty and trustworthiness as intimate disclosure increase (Berndt, 1996). Similarly, romantic interests, dating, and social interaction with peers are increasingly important and are typical for this developmental period (Kuo et al., 2013; Regan & Joshi, 2003). In addition, interactions and experiences during this time allow for more complex emotions and romantic and social interactions later life. Such experiences also change and deepen romantic relationships, going from more friendship-like qualities to more bonding, intimacy, caring for one another and sexuality (Furman & Wehner, 1994). Furthermore, during adolescence, making and maintaining friendships and relationships becomes an individual task, rather than a task that is facilitated by parents or caregivers. In individuals with ASD particularly adolescence is a vulnerable period, as social problems typically worsen, as well as the emergence of feelings of loneliness and isolation (Locke et al., 2010). Findings in adolescent populations with ASD discuss negative experiences, such as anxiety, loneliness, limited opportunities to learn and practice social and romantic skills or to initiate relationships, and differences in sexual orientation (see Pecora et al., 2016 for elaborate discussion). However, these studies did not investigate desired characteristics in (potential) friends or romantic partners, especially in relation to self-perceived characteristics.

For many TD individuals, friendships are a steppingstone to romantic relationships (Fraley et al., 2013). Often the friendships, which become increasingly important during adolescence, serve as an opportunity to learn and practice social and relationship skills, as well as opportunities to meet potential partners (Glick & Rose, 2011; Seiffge-Krenke, 2003). There are studies that describe that a lack of friendships may decrease the possibility of practicing social/romantic skills (e.g., Strunz et al., 2017), which could escalate into inappropriate courting behavior (e.g., Stokes et al., 2007). In addition, qualities, which may be deemed valuable in a friend, are also often sought-after traits in a potential romantic partner (e.g., Sprecher & Regan, 2002), implying that desired characteristics in a friend may be at least to some extent related to desired characteristics in romantic partners. Lastly, congruence between friends (having similar characteristics) is important for a friendship to flourish (Bagwell & Schmidt, 2011). Therefore, knowing what adolescents with and without ASD would desire in their friends and/or romantic partners, also in relation to their own characteristics, may give insights into the trajectories of social and psychosexual development, for individuals with and without ASD. In turn, such knowledge could inform how support may be better tailored to assist in forming relationships and can be used to optimize existing evidence-based interventions, which could decrease loneliness and isolation.

Therefore, this study investigated the association of the desired characteristics in a friend and romantic partner with self-perceived (own) characteristics in adolescents with ASD, as well as in TD adolescents. This will provide information on whether adolescents look for someone similar (i.e., congruent) or different (i.e., complementing) to how they regard themselves. Given the known gender differences, as discussed above, in friendship and romantic relationships in individuals with ASD (e.g., Byers et al., 2013a, 2013b; Sedgewick et al., 2019b) and the limited number of females in our data set, we focused on adolescent males. Based on clinical observations, we hypothesized that male adolescents with ASD show a bigger discrepancy between their desired characteristics in a friend or romantic partner and their self-perceived characteristics than TD adolescents. As a first step, we compared which, and to what extent, characteristics adolescents with ASD desire in a romantic partner and friends, to TD adolescents. We hypothesized that adolescents with ASD desire different characteristics, and to a different extent (i.e., more or less), in their romantic partners and friends than TD adolescents. Second, we investigated the relation between self-perceived characteristics and friend and partner characteristics. We hypothesized that adolescents with ASD will be shown a larger discrepancy (more complementing) than TD adolescents (more congruent). Knowledge about desired characteristics, as well as the relation to self-perceived characteristics, may shed light on why individuals with ASD experience difficulties in forming and maintaining social relationships. The relevance of research on both the experiences and navigation of sexuality across the lifespan (priority ranking #3 out of 10) as well as how to support and promote sexual well-being (priority ranking #2 out of 10) has been underlined as relevant future research in this field by researchers, groups of people with ASD and other stakeholders (Dewinter et al, 2020).

Method

Participants and Procedure

Between 2011 and 2012, data for this study were collected from an ASD group and a TD group. As the ASD sample had a limited number of female adolescents, it was decided to only include the male adolescents in this study. This was done as gender can have a significant relation with partner preferences (e.g., Furnham, 2009; Hall, 2011) and the quality of a friendship (Kuo et al., 2013; Sedgewick et al., 2019a). Next, the two groups (ASD and TD) were matched on age with a maximum of one-month variation in age (i.e., 1-month fuzz in matching procedure). Matching on age was done because age may also influence which qualities are desired in a romantic partner and friend. Older participants include different and more information in their definition of romantic partners and friendship (Collins, 2003; Petrina et al., 2014), e.g., intimacy, mutual help/protection, and similarity in personality. In addition, matching, particularly in ASD research, is valuable to generate a more precise evaluation of potential differences with comparison groups (Burack et al., 2004). The sampling was set with a ratio of one adolescent with ASD to one TD adolescent. This ratio was chosen primarily to increase similarity between the two groups. As described in Stuart (2010) although it may reduce sample size, given that matched to the smallest sample the overall power may not be reduced much, and in addition, it can increase power due to reduced extrapolation and higher precision. In addition, in a larger matching ratio the final matching may have been poorer (i.e., matches may be less similar), leading to less comparability. By ensuring well-matched pairs in a relatively smaller sample, overall, the group is more comparable, and results can be interpreted with more certainty.

The ASD group (N = 38; ages 14 to 19) was selected from a larger clinical sample from the outpatient’s Department of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry/psychology of the Erasmus MC-Sophia Rotterdam, the Netherlands, who were participating in a follow-up study (de Bruin et al., 2007; Louwerse et al., 2015). For the current study only males with a best-estimate ASD diagnosis were included.

In the first study between July 2002 and September 2004, 503 children were referred for psychiatric evaluation. Of the 503 referrals, 234 children were eligible to be included in the follow-up study due to their social and/or communication problems at the time of the first study (see Eussen et al., 2015; Louwerse et al., 2015 for information on the procedure). Of the 234 children, for 104 (42.3%) children a best-estimate ASD diagnosis was indicated as based on the ADI-R and ADOS (see ASD diagnostic procedure below). Only those with a best-estimate ASD diagnosis received the questionnaire to participate in this part of the study. Of the 104 adolescents with a best-estimate ASD diagnosis, 58 (55.8%) returned the questionnaire. The group who did not return the questionnaire did not differ significantly from the group who did on age (t(77) = 0.68, p = 0.50), intelligence (t(59) = -1.43, p = 0.16), or gender (χ2(1, n = 79) = 0.46, p = 0.50). As only males were included (n = 49), the matching based on age resulted in a final ASD sample of 38 male adolescents. The mean age of the ASD group was 16.50 years (range 14.10–19.30, SD = 1.60) with a mean total IQ of 104.40 (range 71–135, SD = 14.5).

The TD group (N = 38; ages 14 to 19) was drawn from a Dutch general population study (N = 1710) (Evans et al., 2012; Louwerse et al., 2013; Tick et al., 2008) from which 326 individuals were eligible to participate based on their age (between 12 and 21 years old) (Evans et al., 2012). Of the 326 adolescents who were contacted, 113 (35%) returned the questionnaire. To ensure the TD group would be without autistic characteristics, we additionally excluded individuals if they had elevated autistic characteristics (n = 22) as assessed with the Autism Quotient (AQ; Baron-Cohen et al., 2001). This resulted in a sample of 91 adolescents (of which 38 male), who returned the questionnaire and were without autistic characteristics on the AQ. Those who did not return the questionnaire did not differ significantly from the group who did return the questionnaire on intelligence (t(118) = −0.66, p = 0.51), or gender (χ2(1, n = 131) = 1.96, p = 0.16). However, the group who did return the questionnaire was significantly younger (M = 16.12, SD = 1.47) than the group who did not (M = 16.73, SD = 1.77; t(129) = 2.03, p = 0.04). Matching of the TD adolescents with ASD group resulted in 38 TD adolescents to participate in the current study. The mean age of the TD sample (n = 38) was 16.35 years (range 14.1–19.3, SD = 1.66), and they had a mean total IQ of 103.61 (range 64–152, SD = 16.40).

The study was approved by the Medical Ethical Review Committee (MEC-2008–388). All adolescents gave informed consent and, where relevant due to their age, also the parents.

ASD Diagnostic Procedure

The best-estimate clinical diagnosis of ASD was obtained by means of the Autism Diagnostic Interview Revised (ADI-R; Rutter et al., 2003) and the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule (ADOS; Lord et al., 2000). Examiners who completed the research-training and had achieved sufficient reliability for administration and coding administered the ADI-R and ADOS. Module 4 of the ADOS was primarily used, based on age and language capability of the sample, although for six participants the ADOS module 3 was used. The examiner of the ADI-R and the examiner of the ADOS reviewed DSM-IV-TR criteria of ASD (i.e., Pervasive Developmental Disorder) and together they obtained a consensus diagnosis (Falkmer et al., 2013).

Measures

Characteristics

In the current study, we used a part of the Teen Transition Inventory (TTI; Dekker et al., 2017) which was developed using feedback of adolescents with ASD on wording and content. Seven characteristics were rated by the participants three times, first, to what level they possessed the characteristic, second, to what level they desired this characteristic in a partner, and third, to what level they desired this characteristic in a friend. The seven characteristics were: funny, popular, nice, cool, smart, trustworthy, and good looking. Two additional characteristics were part of the list of characteristics for a friend and partner, i.e., similar interests and being rich. All characteristics were rated on a 3-point rating scale (“Not at all,” “Somewhat,” and “Definitely”).

The wording in the TTI (Dekker et al., 2017) was aimed to be as concrete and non-ambiguous as possible, to better suit the ASD population as well as the age of the participants. The characteristics in the current study were based on terms used in the previous research in TD young adults (e.g., Sprecher & Regan, 2002). The characteristics can be roughly divided into three categories: intrinsic characteristics (i.e., trustworthy, nice, funny, smart, and similar interests), extrinsic characteristics (i.e., good looking), and social status (i.e., popular, cool, rich). The latter two categories are generally not used in descriptions of high-quality friendship, but have been found to be more relevant for partner choice, as well as for adolescents as social status is increasingly important then (Caravita et al., 2009; Sprecher & Regan, 2002).

Physical Development

For physical development, we used the Tanner stages, a staging system which uses schematic drawings of secondary sexual characteristics divided into five standard stages (Marshall & Tanner, 1969, 1970). The adolescent indicated on the gender appropriate sketches which stage resembled the physical appearance of himself/herself most. The ratings have been used widely and shown good reliability and validity (Dorn et al., 1990).

Analyses

Descriptive Statistics

As only males were selected and the two groups are matched on age, no significant differences were expected on these descriptive characteristics. To ensure this, and for other descriptive characteristics, we investigated whether the two groups differed in age, self-reported physical development (i.e., Tanner stages), and intelligence. Furthermore, for the ASD group we analyzed the severity of their ASD by means of the calibrated severity score (Gotham et al., 2009; Hus et al., 2014) on the ADOS (Lord et al., 2000) as well as their score on the ADI–R (Lord et al., 1994) (see section ASD Diagnostic Procedure for more information). In addition, we investigated how many adolescents in our sample claimed to have experience with friendship and romantic relationships, as well as if they thought they would make a good friend or partner. Finally, for each group (ASD and TD) we ranked the characteristics of how they view themselves from most present to least present, as well as in a friend and a partner from most desired to least desired.

Group Differences Friend/Partner Characteristics

To investigate differences in desired characteristics in a friend between the adolescents with ASD and the TD adolescents, we ran chi-square tests to check whether the groups (ASD vs. TD) differed significantly in how much they desire each characteristic in a friend. Similar analyses were performed to examine desired characteristics in a partner.

Relation Self-Perception to Friend or Partner Characteristics

Our main goal was to investigate whether there would be a significant relation between self-perceived level of having characteristics and the level to which these characteristics are desired in a friend and a partner. For this purpose, we ran Wilcoxon signed-rank tests for both groups (ASD and TD) comparing self to friend characteristics and self to partner characteristics.

Results

Sample Descriptives

There were no significant differences in age, intelligence, and self-reported physical development (Tanner stage) between the two groups (see Table 1). Furthermore, the majority of the adolescents in both groups reported that they currently had at least one meaningful friendship. About two-third in both groups reported they have dated someone, which means they also did not differ significantly in this respect. Interestingly, there was a significant difference in how the adolescents consider themselves in terms of being a good friend or a good romantic partner. Adolescents with ASD considered themselves to be a lesser friend (M = 2.60, SD = 0.50), than their TD peers (M = 2.82, SD = 0.46; t(73) = −2.00, p = 0.048), as well as a significantly lesser partner (ASD: M = 2.14, SD = 0.72; TD: M = 2.50, SD = 0.69; t(72) = −2.20, p = 0.03).

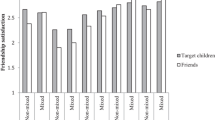

Table 2 shows the rankings of the different characteristics per group, regarding what the adolescents desire in a partner and in a friend, as well as how the adolescents view themselves. The results showed that for desired characteristics in partners, the top four of the ranking was the same in the ASD group and the TD group (with some variation in percentages), but the other five characteristics are ranked slightly different. Regarding desired characteristics in a friendship, it stood out that place one and two in the ranking are switched when comparing the ASD and TD groups, but primarily there was a consensus between the two groups in terms of ranking. As for the characteristics of themselves, the ranking was the same for the first four places, although the number of adolescents who claim this characteristic ‘suits them very much or often’ did differ (i.e., lower percentages in the ASD group).

Group Differences Friend Characteristics

For friend characteristics, we ran Chi-square tests to investigate whether the scoring per characteristic differed significantly between the two groups. As can be seen in Table 3, none of the scores significantly differed between the ASD and TD groups. This indicates that for friends, both groups desired each characteristic to a similar level.

Group Differences Partner Characteristics

Similarly, to test whether the ranking of partner characteristics differed between the two groups, we ran Chi-square tests. As can be seen in Table 4, none of the scorings significantly differed between the ASD and TD groups. This means that for each partner characteristic both groups desired it to a similar level.

Relation Self-Perception to Friend or Partner Characteristics

Lastly, we investigated whether adolescents seek a partner or friend who is like themselves (i.e., congruent) or dissimilar to themselves (complementary). Our results showed that for both the ASD and TD groups, friends were desired who are slightly less like themselves (i.e., more complementary with self) than partners (i.e., more congruent with self).

With regard to friends, the Wilcoxon signed-rank tests indicated that five of the seven characteristics were ranked significantly different in the ASD group when comparing what was desired in a friend and how they viewed themselves. Specifically, the characteristics on which adolescents with ASD rank themselves significantly different compared to what they would desire in a friend were: being popular (z = −4.08; p < 0.001), being nice (z = −2.45; p = 0.01), being cool (z = −2.11; p = 0.04), being smart (z = −4.33; p < 0.001) and being good looking (z = −3.52; p < 0.001). Adolescents with ASD desired a best friend who would be less popular, less cool, less smart, and less good looking but nicer than that they regarded themselves. The TD group showed similar results, with also five characteristics ranked significantly different. In the TD group, a friend was desired who is significantly less funny (z = −3.28; p < 0.01), less popular (z = 5.14; p < 0.001), less cool (z = −4.63; p < 0.001), less smart (z = −5.06; p < 0.001), and less good looking (z = −4.49; p < 0.001) than how they ranked themselves. In contrast to the ASD group, there was no significant difference regarding the characteristic being nice (z = −1.63; p = 0.10), but there was a significant difference on the characteristic funny (desire a less funny friend). The only characteristic which showed no significant difference in both groups was ‘trustworthy’. Thus, both ASD and TD adolescents desire a friend who was similar in terms of trustworthiness compared to how they rated themselves.

With regard to a partner, the Wilcoxon signed-rank tests showed that for four of the seven characteristics, adolescents with ASD rank themselves differently from what they would seek in a partner. Adolescents with ASD desired a partner who is less popular (z = −4.15; p < 0.001), less cool (z = −2.43; p = 0.02); less smart (z = −3.79; p < 0.001), but nicer (z = −1.97; p = 0.05) than they would rate themselves on these variables. In the TD group, three characteristics were rated significantly different when comparing self-image to what is desired in a partner. TD adolescents desired a partner who is less popular (z = −4.84; p < 0.001), less cool (z = −4.72; p < 0.001), and less smart (z = −3.51; p < 0.001) than that they regarded themselves on these variables. In contrast to the ASD adolescents, no significant difference was found regarding the characteristic nice. No significant differences were found on the other variables, i.e., trustworthiness, funny, and good looking.

The results show that for both friends and partners the adolescents with ASD and TD had similar desires in relation to their own characteristics. The only differences found were on the characteristic nice and funny. For the characteristic nice only, a significant difference in ranking was found for the adolescents with ASD, where they desired someone who is nicer compared to how they rated themselves (both in a partner and a friend). For the characteristic funny only for a friend a significant difference was found in ranking in the group of TD adolescents. TD adolescents desired a friend, but not a partner, who is less funny than how they rated themselves.

When including all the males in both samples (n = 49 ASD and n = 38 TD), overall similar results were found.

Discussion

In the past few decades, the empirical and academic interest in romantic relationships and friendships in adolescents with ASD has increased (e.g., Bauminger & Kasari, 2000; Dewinter et al., 2020; Henault, 2006; Pecora et al., 2016). However, it remained unclear which characteristics individuals with ASD desire in a partner or friend, and how these relate to characteristics the adolescents think they themselves possess. The current study investigated desired characteristics in friends and romantic partners, in relation to self-perceived own characteristics, comparing adolescents with and without ASD, in order to examine to what extent, they desire a similar (i.e., congruent) or dissimilar (i.e., complementing) partner or friend to how they perceive themselves. Our study revealed that adolescents with ASD and TD have similar desires regarding which, and how much, they seek certain characteristics in both their partners and friends. Furthermore, it showed that both adolescents with ASD and TD desire a friend and partner who is congruent in some ways (e.g., intrinsic characteristics), but also complementing (e.g., social status characteristics) to their own characteristics.

More specifically, the results showed that adolescents with ASD have similar desires in their partners and friends regarding nine characteristics (i.e., funny, popular, nice, cool, smart, trustworthy, good looking, similar interests, and being rich), when compared to TD adolescents. Also, it showed that particularly intrinsic characteristics (i.e., trustworthy, nice, and funny) are valued more than extrinsic characteristics (i.e., good looking) and social status characteristics (e.g., popular, and rich). The lack of difference between the two groups contradicts our hypothesis that possibly adolescents with ASD desire different characteristics in their relationships. A possible explanation may be that society has an influence on which characteristics are considered to be more desirable than others. This may be subconsciously transferred by parents, caregivers, and peers, but also more explicitly in psycho-educational material or training programs regarding intimate relationships, which may internalize to rules that adolescents with ASD conform to. As rule-breaking is experienced differently and more distressing in individuals with ASD compared to TD adolescents (Bolling et al., 2011), this may explain why they report to desire similar characteristics as their TD peers. More research would be necessary to determine whether indeed desired characteristics are influenced by societal influences and/or opinions of authority figures.

Our main research question was to explore whether adolescents seek someone similar or dissimilar to themselves. Our results showed that both adolescents with ASD and TD adolescents reported to seek people (both partner and friend) who are relatively similar in terms of intrinsic characteristics, but less similar in terms of social status characteristics (i.e., less strong need to be popular, and cool). One difference that stands out is that adolescents with ASD, but not TD adolescents, seek someone who is nicer than themselves, both in a partner and a friend. Several possible explanations for this difference can be found in the adolescents with ASD themselves. Firstly, and interestingly, the difference seems to be caused by the lower score on self-rating rather than a difference in what is desired in friend/partner. This may be indicative of relatively low self-esteem in the adolescents with ASD, especially in terms of their own niceness. This is in line with other research, which has found that children and adolescents with ASD have significantly lower self-esteem than TD children and adolescents (Dekker et al., 2017; McCauley et al., 2019; van der Cruijsen & Boyer, 2021). In addition, the current study showed that there was a significant difference in how the adolescents viewed themselves in romantic relationships and friendships: significantly less adolescents with ASD felt confident that they would be a good partner as well as a good friend, than the matched TD adolescents. A possible explanation may be that particularly cognitively able adolescents with ASD—of which our sample existed—are aware of their social difficulties, which may lead them to think they are less suitable partners and friends for others. Although this requires more research, it is in line with previous research, which has shown that particularly the awareness of the social difficulties can have negative results (Locke et al., 2010; Sterling et al., 2008). Another explanation could be earlier experiences with peer rejection, which is common for many with ASD (Carrington & Graham, 2001; Symes & Humphrey, 2010). Possibly, previous peer rejection may have caused individuals with ASD to assume they will not be good partners or friends. This may also putatively explain the difficulties individuals with ASD have with developing and maintaining relationships, as low self-esteem may lead to less optimal outcomes (e.g., Takizawa et al., 2014) and correlates significantly with loneliness (Mazurek, 2014) and lower friendship qualities (Bauminger et al., 2004). Future research could investigate self-esteem in relation to self-perceived characteristics and desired characteristics in populations with ASD.

Interestingly, the results also show that adolescents with ASD seek someone who is closer to their own characteristics than TD adolescents, particularly in friends. Research in TD individuals found that the importance of ideal standards for a partner is calibrated to match one’s self-perception on the same dimensions (Brown & Brown, 2015; Campbell et al., 2001; Kenrick et al., 1993; Sprecher & Regan, 2002). Although previous research has suggested that individuals with ASD may be less capable of self-reflection and insight into their own functioning (Cederlund et al., 2010), our results suggest that cognitively able adolescents with ASD may in fact adapt their desires for partners and friends more to their own capabilities in those domains than TD adolescents. This could indicate a certain level of self-reflection and flexibility in real-life, alternatively, individuals with ASD may simply seek individuals who are ‘less’ desirable and therefore closer match their own lower self-image.

There are several noteworthy limitations to the current study. Here we discuss the four most prominent limitations. First, a limited number of characteristics were investigated, and it would be valuable to include more characteristics and possibly allow adolescents to add characteristics they desire. For example, the characteristic “dependable” has been found in the previous research to be important (Figueredo et al., 2006), but was not included in our list. Second, each characteristic was rated on a 3-point scale, which may have allowed insufficiently for variance. Future research could use a wider range. Third, our sample was limited, with 38 participants per group and only males. Given the differences in social and romantic functioning in females with ASD, it would be valuable to investigate desired characteristics in both females and males with ASD as well. Last, the ASD group consisted of predominantly average to high IQ, which decreases the generalizability of our findings to the more heterogeneous group of adolescents with ASD. Larger more diverse groups could provide more insight into which characteristics are desired by adolescents with ASD.

Despite the limitations, the current study adds new insights to the growing literature on the topic of psychosocial and psychosexual functioning in individuals with ASD. First, the current study is the first to investigate self-perceived characteristics in relation to desired characteristics in individuals with ASD and directly compare TD adolescents with adolescents with ASD. Second, self-report is still not commonly used in research into psychosexual functioning in adolescents with ASD (Fernandes et al., 2016). Although self-reflection or self-evaluation within children and adolescents with ASD has been challenged over time with respect to the reliability (e.g., Cederlund et al., 2010) and potential overestimation (Furlano et al., 2015), more recent studies have underlined the value of self-report and the insight to the personal experience of children and adolescents with ASD (e.g., Keith et al., 2019; Stokes et al., 2017). For example, the study of Cage et al. (2016) showed that adolescents (age 12 to 15) with ASD do have a self-concept and can report on it. In a study investigating the relation between survey information and autonomic measures (Keith et al., 2019), a high correlation between the two types was found, implying that self-report can provide unique insights into the experience of adolescents with ASD themselves. Even more so, a study on quality of life (Stokes et al., 2017) highlighted that parents are perhaps poor proxies of the experience of children with ASD (ages 6 to 20). Although individuals with ASD may over-estimate their competencies (e.g., Furlano et al., 2015), self-report does provide insights into how they think they are doing. Potentially, adapting self-perception to more reflect reality may be something useful in also seeking friends and romantic partners that better match this. By asking the adolescents themselves what they desire in a friend/partner, more insight is gained into their experiences, rather than the opinion of others. As the adolescents must establish and maintain relationships more and more on their own—as opposed to with help of parents or caregivers—information about their personal desires and experiences can better inform how parents, caregivers, and healthcare professionals may be able to support the adolescents. Third, by making use of a TD comparison group as well as using the same measurement in both groups, our results allow for a direct comparison of adolescents with ASD to a TD sample. Thereby, we can more clearly indicate whether and how adolescents with ASD differ from TD adolescents. As we matched our sample, our results cannot be caused by factors such as gender, age, and intelligence. Fourth, adolescence is the period in which increasingly time is spent with other gender peers and romantic partners (Collins et al., 2009). Also, previous research has shown that there is no significant difference in age of onset regarding, for example, sexual activity between adolescents with ASD and TD adolescents (Dekker et al., 2017). Therefore, investigating preferences for characteristics of friends and romantic partners during this period may shed more light on potential differences in the developmental paths of relationships between adolescents with ASD and their TD peers.

For future research, it may be beneficial to also include qualitative data, to go more into depth on how the adolescents would define certain characteristics and why they find them important, and how it may relate to their self-perception. Furthermore, it would be interesting to also receive information from individuals who are identified as friend or partner as well as relationship satisfaction, to investigate whether indeed the desired characteristics are in line with the partner’s or friend’s actual characteristics. This could perhaps also shed light on if the stated desires match actual characteristics of a friend/partner or if the reported desires are what they think is expected. In addition, investigating desired characteristics and self-perceived characteristics in relationship to self-esteem and in a more diverse population can further elucidate the interplay in individuals with ASD and how it may relate to social and romantic outcomes. Lastly, it may be valuable to include larger samples, to also allow for more complex analyses, for example a form of multivariate testing with profiles, and to be able to include other influential variables, such as physical maturation.

A possible clinical implication of our findings could be that adolescents with ASD may need different support in terms of establishing and maintaining successful long-term interpersonal relationships, a topic which was previously highlighted as an important research focus (Dewinter et al., 2020). Increasing their self-esteem, or at least nuancing their self-image, may benefit adolescents with ASD to find and maintain romantic and friendly relationships. In addition, it could be beneficial to train adolescents with ASD in self-awareness and self-presentation, so if they desire, they can be more desirable for others as a potential partner or friend. Another clinical implication could be increasing the willingness of adolescents with ASD to allow trade-offs between their desires and actual partners/friends. Clinicians, but also parents and other professionals, could perhaps work on the tolerance of individuals with ASD for imperfectness in self, partners and friends, which could lead to more long-lasting mental health and relationships. Although more research is required to see whether, in situations in which personal relationships are established, indeed self-esteem/image, self-awareness/presentation, or flexibility is a problem for adolescents with ASD, it could be valuable to promote these things in support programs for adolescents with ASD, so they may have a better chance at establishing and maintaining personal relationships.

Although beyond the scope of our research, two potential mechanisms may be related to difficulties with high-quality friendship and relationship outcomes and our current findings. First, lower self-esteem and less strategic self-presentation may also lead to less personal relationships. The characteristics sought after by both TD adolescents and adolescents with ASD are elements which individuals with ASD may struggle to offer or present (e.g., being nice). Some research has shown that children with ASD are less strategic and convincing in their self-presentation when seeking personal gain (Begeer et al., 2008). Second, difficulty with flexibility may be another reason why adolescents with ASD struggle with establishing and maintaining personal relationships. Often actual partners or friends will not show all the desired qualities, as there is a trade-off in real relationships (Figueredo et al., 2006; Varella Valentova et al., 2016). Speculatively, in real life adolescents with ASD allow less of a trade-off between what is desired and what an actual friend/partner has as characteristics than TD adolescents. This may lead to a more unattainable combination of characteristics (e.g., an unrealistic combination of characteristics), desired in their romantic partners and friends than TD individuals. Clearly, more research is needed to examine these speculations.

To summarize, our results indicate that in fact adolescents with ASD desire similar characteristics to a similar level as TD adolescents in their partners and friends. And, also comparable to TD adolescents, adolescents with ASD seek a partner and friend who is similar in most intrinsic characteristics, but less similar in other characteristics (i.e., social status and extrinsic characteristics) to themselves. As earlier research has shown that in fact individuals with ASD have a desire for romantic relationships and friendships, our research extends this work by showing that they also desire the same characteristics in their partners and friends as well as the level of congruency they seek with friend/partner as TD adolescents. Although a valuable first step, more research is required to clarify and replicate our findings to translate the current findings into support for adolescents with ASD in successfully navigating relations and sexuality throughout the lifespan. Knowledge on self-perception and desired characteristics may help to better tailor support programs aimed to improve romantic and friendship outcomes, for example by increasing awareness of own characteristics (i.e., better self-awareness), by improving self-presentation to peers, or by aiding in finding a better match in a potential partner or friend. For future research, it would be valuable to investigate more characteristics in a larger and more diverse sample, preferably including self-esteem as well as self-evaluation.

Data Availability

Data and material are not publicly available.

Notes

Given the lack of consensus on identity-first or person-first language (e.g., Kenny et al., 2016), a mix is used throughout this paper.

References

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed). doi: https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596.

Bagwell, C. L., & Schmidt, M. E. (2011). The friendship quality of overtly and relationally victimized children. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 57(2), 158–185.

Ballan, M. S. (2012). Parental perspectives of communication about sexuality in families of children with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 42(5), 676–684. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-011-1293-y

Baron-Cohen, S., Wheelwright, S., Skinner, R., Martin, J., & Clubley, E. (2001). The Autism-Spectrum Quotient (AQ): Evidence from Asperger syndrome/high-functioning autism, males and females, scientists and mathematicians. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 31(1), 5–17. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1005653411471

Bauminger, N., & Kasari, C. (2000). Loneliness and friendship in high-functioning children with autism. Child Development, 71(2), 447–456. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8624.00156

Bauminger, N., Shulman, C., & Agam, G. (2004). The link between perceptions of self and of social relationships in high-functioning children with autism. Journal of Developmental and Physical Disabilities, 16(2), 193–214. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:JODD.0000026616.24896.c8

Begeer, S., Banerjee, R., Lunenburg, P., Meerum Terwogt, M., Stegge, H., & Rieffe, C. (2008). Brief report: Self-presentation of children with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 38(6), 1187–1191. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-007-0503-0

Berndt, T. J. (1996). Transitions in friendship and friends’ influence. In J. A. Graber, J. Brooks-Gunn, & A. C. Petersen (Eds.), Transitions through adolescence: Interpersonal domains and context (pp. 57–84). Psychology Press.

Bolling, D. Z., Pitskel, N. B., Deen, B., Crowley, M. J., McPartland, J. C., Kaiser, M. D., Vander Wijk, B. C., Wu, J., Mayes, L. C., & Pelphrey, K. A. (2011). Enhanced neural responses to rule violation in children with autism: A comparison to social exclusion. Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience, 1(3), 280–294. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dcn.2011.02.002

Brown, M. A., & Brown, J. D. (2015). Self-enhancement biases, self-esteem, and ideal mate preferences. Personality and Individual Differences, 74, 61–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2014.09.039

Burack, J. A., Iarocci, G., Flanagan, T. D., & Bowler, D. M. (2004). On mosaics and melting pots: Conceptual considerations of comparison and matching strategies. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 34(1), 65–73. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:JADD.0000018076.90715.00

Byers, E. S., Nichols, S., & Voyer, S. D. (2013a). Challenging stereotypes: Sexual functioning of single adults with high functioning autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 43(11), 2617–2627. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-013-1813-z

Byers, E. S., Nichols, S., Voyer, S. D., & Reilly, G. (2013b). Sexual well-being of a community sample of high-functioning adults on the autism spectrum who have been in a romantic relationship. Autism, 17(4), 418–433. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361311431950

Cage, E., Bird, G., & Pellicano, L. (2016). ‘I am who I am’: Reputation concerns in adolescents on the autism spectrum. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 25, 12–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rasd.2016.01.010

Calder, L., Hill, V., & Pellicano, E. (2013). ‘Sometimes I want to play by myself’: Understanding what friendship means to children with autism in mainstream primary schools. Autism, 17(3), 296–316. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361312467866

Campbell, L., Simpson, J. A., Kashy, D. A., & Fletcher, G. J. O. (2001). Ideal standards, the self, and flexibility of ideals in close relationships. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 27(4), 447–462. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167201274006

Caravita, S. C. S., Di Blasio, P., & Salmivalli, C. (2009). Unique and interactive effects of empathy and social status on involvement in bullying. Social Development, 18(1), 140–163. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9507.2008.00465.x

Carrington, S., & Graham, L. (2001). Perceptions of school by two teenage boys with Asperger syndrome and their mothers: A qualitative study. Autism, 5(1), 37–48. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361301005001004

Cederlund, M., Hagberg, B., & Gillberg, C. (2010). Asperger syndrome in adolescent and young adult males. Interview, self—and parent assessment of social, emotional, and cognitive problems. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 31(2), 287–298. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ridd.2009.09.006

Cheak-Zamora, N. C., Teti, M., Maurer-Batjer, A., O’Connor, K. V., & Randolph, J. K. (2019). Sexual and relationship interest, knowledge, and experiences among adolescents and young adults with autism spectrum disorder. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 48(8), 2605–2615. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-019-1445-2

Church, C., Alisanski, S., & Amanullah, S. (2000). The social, behavioral, and academic experiences of children with Asperger syndrome. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 15(1), 12–20. https://doi.org/10.1177/108835760001500102

Collins, W. A. (2003). More than myth: The developmental significance of romantic relationships during adolescence. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 13(1), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1111/1532-7795.1301001

Collins, W. A., Welsh, D. P., & Furman, W. (2009). Adolescent romantic relationships. Annual Review of Psychology, 60(1), 631–652. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.60.110707.163459

de Bruin, E. I., Ferdinand, R. F., Meester, S., de Nijs, P. F. A., & Verheij, F. (2007). High rates of psychiatric co-morbidity in PDD-NOS. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 37(5), 877–886. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-006-0215-x

Dekker, L. P., van der Vegt, E. J. M., van der Ende, J., Tick, N., Louwerse, A., Maras, A., Verhulst, F. C., & Greaves-Lord, K. (2017). Psychosexual functioning of cognitively-able adolescents with autism spectrum disorder compared to typically developing peers: The development and testing of the Teen Transition Inventory-a self- and parent report questionnaire on psychosexual functioning. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 47(6), 1716–1738. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-017-3071-y

Dekker, V., Nauta, M. H., Timmerman, M. E., Mulder, E. J., van der Veen-Mulders, L., van den Hoofdakker, B. J., van Warners, S., Vet, L. J. J., Hoekstra, P. J., & de Bildt, A. (2019). Social skills group training in children with autism spectrum disorder: A randomized controlled trial. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 28(3), 415–424. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-018-1205-1

Dewinter, J., De Graaf, H., & Begeer, S. (2017). Sexual orientation, gender identity, and romantic relationships in adolescents and adults with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 47(9), 2927–2934. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-017-3199-9

Dewinter, J., van der Miesen, A. I. R., & Graham Holmes, L. (2020). INSAR Special Interest Group Report: Stakeholder perspectives on priorities for future research on autism, sexuality, and intimate relationships. Autism Research, 13(8), 1248–1257. https://doi.org/10.1002/aur.2340

Dorn, L. D., Susman, E. J., Nottelmann, E. D., Inoff-Germain, G., & Chrousos, G. P. (1990). Perceptions of puberty: Adolescent, parent, and health care personnel. Developmental Psychology, 26(2), 322–329. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.26.2.322

Eussen, M. L. J. M., de Bruin, E. I., Van Gool, A. R., Louwerse, A., van der Ende, J., Verheij, F., Verhulst, F. C., & Greaves-Lord, K. (2015). Formal thought disorder in autism spectrum disorder predicts future symptom severity, but not psychosis prodrome. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 24(2), 163–172. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-014-0552-9

Evans, B. E., Greaves-Lord, K., Euser, A. S., Tulen, J. H. M., Franken, I. H. A., & Huizink, A. C. (2012). Alcohol and tobacco use and heart rate reactivity to a psychosocial stressor in an adolescent population. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 126(3), 296–303. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.05.031

Falkmer, T., Anderson, K., Falkmer, M., & Horlin, C. (2013). Diagnostic procedures in autism spectrum disorders: A systematic literature review. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 22(6), 329–340. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-013-0375-0

Fernandes, L. C., Gillberg, C. I., Cederlund, M., Hagberg, B., Gillberg, C., & Billstedt, E. (2016). Aspects of sexuality in adolescents and adults diagnosed with autism spectrum disorders in childhood. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 46(9), 3155–3165. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-016-2855-9

Figueredo, A. J., Sefcek, J. A., & Jones, D. N. (2006). The ideal romantic partner personality. Personality and Individual Differences, 41(3), 431–441. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2006.02.004

Finke, E. H. (2016). Friendship: Operationalizing the intangible to improve friendship-based outcomes for individuals with autism spectrum disorder. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 25(4), 654–663. https://doi.org/10.1044/2016_AJSLP-15-0042

Fletcher, G. J. O., Tither, J. M., O’Loughlin, C., Friesen, M., & Overall, N. (2004). Warm and homely or cold and beautiful? Sex differences in trading off traits in mate selection. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 30(6), 659–672. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167203262847

Fraley, R. C., Roisman, G. I., Booth-LaForce, C., Owen, M. T., & Holland, A. S. (2013). Interpersonal and genetic origins of adult attachment styles: A longitudinal study from infancy to early adulthood. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 104(5), 817–838. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0031435

Furlano, R., Kelley, E. A., Hall, L., & Wilson, D. E. (2015). Self-perception of competencies in adolescents with autism spectrum disorders. Autism Research, 8(6), 761–770. https://doi.org/10.1002/aur.1491

Furman, W., & Wehner, E. A. (1994). Romantic views: Toward a theory of adolescent romantic relationships. In R. Montemayor, G. R. Adams, & T. P. Gullotta (Eds.), Personal relationships during adolescence (pp. 168–195). Sage Publications Inc.

Furnham, A. (2009). Sex differences in mate selection preferences. Personality and Individual Differences, 47(4), 262–267. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2009.03.013

Glick, G. C., & Rose, A. J. (2011). Prospective associations between friendship adjustment and social strategies: Friendship as a context for building social skills. Developmental Psychology, 47(4), 1117–1132. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0023277

Gotham, K., Pickles, A., & Lord, C. (2009). Standardizing ADOS Scores for a measure of severity in autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 39(5), 693–705. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-008-0674-3

Hall, J. A. (2011). Sex differences in friendship expectations: A meta-analysis. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 28(6), 723–747. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407510386192

Head, A. M., McGillivray, J. A., & Stokes, M. (2014). Gender differences in emotionality and sociability in children with autism spectrum disorders. Molecular Autism, 5(1), 19. https://doi.org/10.1186/2040-2392-5-19

Hellemans, H., Roeyers, H., Leplae, W., Dewaele, T., & Deboutte, D. (2010). Sexual behavior in male adolescents and young adults with autism spectrum disorder and borderline/mild mental retardation. Sexuality and Disability, 28(2), 93–104. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11195-009-9145-9

Henault, I. (2006). Asperger’s syndrome and sexuality: From adolescence through adulthood. Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Hus, V., Gotham, K., & Lord, C. (2014). Standardizing ADOS domain scores: Separating severity of social affect and restricted and repetitive behaviors. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 44(10), 2400–2412. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-012-1719-1

Kanner, L. (1943). Autistic disturbances of affective contact. Nervous Child, 2(3), 217–250.

Keith, J. M., Jamieson, J. P., & Bennetto, L. (2019). The importance of adolescent self-report in autism spectrum disorder: Integration of questionnaire and autonomic measures. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 47(4), 741–754. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-018-0455-1

Kenny, L., Hattersley, C., Molins, B., Buckley, C., Povey, C., & Pellicano, E. (2016). Which terms should be used to describe autism? Perspectives from the UK autism community. Autism, 20(4), 442–462. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361315588200

Kenrick, D., Groth, G., Trost, M., & Sadalla, E. (1993). Integrating evolutionary and social exchange perspectives on relationships: Effects of gender, self-appraisal, and involvement level on mate selection criteria. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 64, 951–969. https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-3514.64.6.951

Kuo, M. H., Orsmond, G. I., Cohn, E. S., & Coster, W. J. (2013). Friendship characteristics and activity patterns of adolescents with an autism spectrum disorder. Autism, 17(4), 481–500. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361311416380

Laugeson, E. A., Frankel, F., Gantman, A., Dillon, A. R., & Mogil, C. (2012). Evidence-based social skills training for adolescents with autism spectrum disorders: The UCLA PEERS program. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 42(6), 1025–1036. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-011-1339-1

Locke, J., Ishijima, E. H., Kasari, C., & London, N. (2010). Loneliness, friendship quality and the social networks of adolescents with high-functioning autism in an inclusive school setting. Journal of Research in Special Educational Needs, 10(2), 74–81. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-3802.2010.01148.x

Lord, C., Risi, S., Lambrecht, L., Cook, E. H., Leventhal, B. L., DiLavore, P. C., Pickles, A., & Rutter, M. (2000). The Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule—Generic: A standard measure of social and communication deficits associated with the spectrum of autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 30(3), 205–223. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1005592401947

Lord, C., Rutter, M., & Le Couteur, A. (1994). Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised: A revised version of a diagnostic interview for caregivers of individuals with possible pervasive developmental disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 24(5), 659–685. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02172145

Louwerse, A., Eussen, M. L. J. M., Van der Ende, J., de Nijs, P. F. A., Van Gool, A. R., Dekker, L. P., Verheij, C., Verheij, F., Verhulst, F. C., & Greaves-Lord, K. (2015). ASD symptom severity in adolescence of individuals diagnosed with PDD-NOS in childhood: Stability and the relation with psychiatric comorbidity and societal participation. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 45(12), 3908–3918. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-015-2595-2

Louwerse, A., van der Geest, J. N., Tulen, J. H. M., van der Ende, J., Van Gool, A. R., Verhulst, F. C., & Greaves-Lord, K. (2013). Effects of eye gaze directions of facial images on looking behaviour and autonomic responses in adolescents with autism spectrum disorders. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 7(9), 1043–1053. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rasd.2013.04.013

Marshall, W. A., & Tanner, J. M. (1969). Variations in pattern of pubertal changes in girls. Archives of Disease in Childhood, 44(235), 291–303. https://doi.org/10.1136/adc.44.235.291

Marshall, W. A., & Tanner, J. M. (1970). Variations in the pattern of pubertal changes in boys. Archives of Disease in Childhood, 45(239), 13–23. https://doi.org/10.1136/adc.45.239.13

May, T., Pang, K. C., & Williams, K. (2017). Brief report: Sexual attraction and relationships in adolescents with autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 47(6), 1910–1916. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-017-3092-6

Mazurek, M. O. (2014). Loneliness, friendship, and well-being in adults with autism spectrum disorders. Autism, 18(3), 223–232. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361312474121

McCauley, J. B., Harris, M. A., Zajic, M. C., Swain-Lerro, L. E., Oswald, T., McIntyre, N., Trzesniewski, K., Mundy, P., & Solomon, M. (2019). Self-esteem, internalizing symptoms, and theory of mind in youth with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 48(3), 400–411. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2017.1381912

Pecora, L. A., Mesibov, G. B., & Stokes, M. (2016). Sexuality in high-functioning autism: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 46(11), 3519–3556. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-016-2892-4

Petrina, N., Carter, M., & Stephenson, J. (2014). The nature of friendship in children with autism spectrum disorders: A systematic review. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 8(2), 111–126. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rasd.2013.10.016

Płatos, M., & Pisula, E. (2021). Friendship understanding in males and females on the autism spectrum and their typically developing peers. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 81, 101716. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rasd.2020.101716

Regan, P. C., & Joshi, A. (2003). Ideal partner preferences among adolescents. Social Behavior and Personality, 31(1), 13–20. https://doi.org/10.2224/sbp.2003.31.1.13

Regan, P. C., Levin, L., Sprecher, S., Christopher, F. S., & Gate, R. (2000). Partner preferences. Journal of Psychology & Human Sexuality, 12(3), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1300/J056v12n03_01

Rowley, E., Chandler, S., Baird, G., Simonoff, E., Pickles, A., Loucas, T., & Charman, T. (2012). The experience of friendship, victimization and bullying in children with an autism spectrum disorder: Associations with child characteristics and school placement. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 6(3), 1126–1134. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rasd.2012.03.004

Rutter, M., Le Couteur, A., & Lord, C. (2003). Autism diagnostic interview—Revised (ADI-R). Western Psychological Services.

Sedgewick, F., Hill, V., & Pellicano, E. (2019a). ‘It’s different for girls’: Gender differences in the friendships and conflict of autistic and neurotypical adolescents. Autism, 23(5), 1119–1132. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361318794930

Sedgewick, F., Hill, V., Yates, R., Pickering, L., & Pellicano, E. (2016). Gender differences in the social motivation and friendship experiences of autistic and non-autistic adolescents. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 46(4), 1297–1306. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-015-2669-1

Sedgewick, F., Leppanen, J., & Tchanturia, K. (2019b). The Friendship Questionnaire, autism, and gender differences: A study revisited. Molecular Autism, 10(1), 40. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13229-019-0295-z

Seiffge-Krenke, I. (2003). Testing theories of romantic development from adolescence to young adulthood: Evidence of a developmental sequence. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 27(6), 519–531. https://doi.org/10.1080/01650250344000145

Sprecher, S., & Regan, P. C. (2002). Liking some things (in some people) more than others: Partner preferences in romantic relationships and friendships. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 19(4), 463–481. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407502019004048

Sterling, L., Dawson, G., Estes, A., & Greenson, J. (2008). Characteristics associated with presence of depressive symptoms in adults with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 38(6), 1011–1018. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-007-0477-y

Stokes, M., Kornienko, L., Scheeren, A. M., Koot, H. M., & Begeer, S. (2017). A comparison of children and adolescent’s self-report and parental report of the PedsQL among those with and without autism spectrum disorder. Quality of Life Research, 26(3), 611–624. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-016-1490-4

Stokes, M., Newton, N., & Kaur, A. (2007). Stalking, and social and romantic functioning among adolescents and adults with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 37(10), 1969–1986. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-006-0344-2

Strunz, S., Schermuck, C., Ballerstein, S., Ahlers, C. J., Dziobek, I., & Roepke, S. (2017). Romantic relationships and relationship satisfaction among adults with Asperger syndrome and high-functioning autism. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 73(1), 113–125. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.22319

Stuart, E. A. (2010). Matching methods for causal inference: A review and a look forward. Statistical Science: A Review Journal of the Institute of Mathematical Statistics, 25(1), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1214/09-STS313

Symes, W., & Humphrey, N. (2010). Peer-group indicators of social inclusion among pupils with autistic spectrum disorders (ASD) in mainstream secondary schools: A comparative study. School Psychology International, 31(5), 478–494. https://doi.org/10.1177/0143034310382496

Takizawa, R., Maughan, B., & Arseneault, L. (2014). Adult health outcomes of childhood bullying victimization: Evidence from a five-decade longitudinal British birth cohort. American Journal of Psychiatry, 171(7), 777–784. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2014.13101401

Tick, N. T., van der Ende, J., & Verhulst, F. C. (2008). Ten-year increase in service use in the Dutch population. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 17(6), 373–380. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-008-0679-7

Turner, D., Briken, P., & Schöttle, D. (2017). Autism-spectrum disorders in adolescence and adulthood: Focus on sexuality. Current Opinion in Psychiatry, 30(6), 409–416. https://doi.org/10.1097/YCO.0000000000000369

van der Cruijsen, R., & Boyer, B. E. (2021). Explicit and implicit self-esteem in youth with autism spectrum disorders. Autism, 25(2), 349–360. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361320961006

Varella Valentova, J., Štěrbová, Z., Bártová, K., & Corrêa Varella, M. A. (2016). Personality of ideal and actual romantic partners among heterosexual and non-heterosexual men and women: A cross-cultural study. Personality and Individual Differences, 101, 160–166. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2016.05.048

Visser, K., Greaves-Lord, K., Tick, N. T., Verhulst, F. C., Maras, A., & van der Vegt, E. J. M. (2017). A randomized controlled trial to examine the effects of the Tackling Teenage psychosexual training program for adolescents with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 58(7), 840–850. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.12709

Acknowledgements

We are grateful for all the adolescents and their parents who participated in this study. We would like to thank Frieda Boudesteijn for her contributions to the development of the Teen Transition Inventory (TTI).

Funding

This project was financially supported by Yulius, a large mental health organization in the South-West of the Netherlands, together with Erasmus MC, from a grant of the Sophia Children’s Hospital Fund (Grant Number 617, titled Tackling Teenage: a multicenter study on psychosexual development and intimacy in adolescents with Autism Spectrum Disorder), as well as the Academische Werkplaats Autisme (Academic Workplace Autism—The Netherlands) which is a government-funded cooperation between several clinical and research centers in the Netherlands (ZonMw grant: Project number 639003101).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

L.P. Dekker and K. Greaves-Lord are the developers of the TTI, for this they do not receive remuneration. K. Greaves-Lord is the second author on the Dutch ADOS-2 manual, for which Yulius receives remuneration. F.C. Verhulst is former head of the department of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry at Erasmus MC, which publishes ASEBA materials and from which he receives remuneration. A. Maras has been a consultant to/member of advisory board of/and/or speaker for Janssen Cilag BV, Eli Lilly, Shire. He is not an employee or a stock shareholder of any of these companies. He has no other financial or material support, including expert testimony, patents, and royalties. E. van der Vegt, A. Louwerse, K. Visser, and J. van der Ende declare that they do not have conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in the study involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. This study was approved by the medical ethical commission of the Erasmus Medical Center, Rotterdam (MEC-2013–040).

Informed Consent

Written informed consent is obtained from all participating adolescents and their parents.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Dekker, L.P., van der Vegt, E.J.M., Louwerse, A. et al. Complementing or Congruent? Desired Characteristics in a Friend and Romantic Partner in Autistic versus Typically Developing Male Adolescents. Arch Sex Behav 52, 1153–1167 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-022-02444-y

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-022-02444-y