Abstract

Using baseline data from the PrEP1519 cohort, in this article we aimed to analyze: (i) the effectiveness of demand creation strategies (DCS) to enroll adolescent men who have sex with men (AMSM) and adolescent transgender women (ATGW) into an HIV combination prevention study in Brazil; (ii) the predictors of DCS for adolescents’ enrollment; and (iii) the factors associated with DCS by comparing online and face-to-face strategies for enrollment. The DCS included peer recruitment (i.e., online and face-to-face) and referrals from health services and non-governmental organizations (NGOs). AMSM and ATGW who agreed to participate in the study could opt to enroll in either PrEP (PrEP arm) or to use other prevention methods (non-PrEP arm). Bivariate and multivariate analyses were conducted and logistic regression odds ratios were estimated. The DCS reached 4529 AMSM and ATGW, the majority of which were derived online (73.8%). Of this total, 935 (20.6%) enrolled to participate (76.6% in PrEP arm and 23.4% in non-PrEP arm). The effectiveness of enrolling adolescents into both arms was greater via direct referrals (235/382 and 84/382, respectively) and face-to-face peer recruitment (139/670 and 35/670, respectively) than online (328/3342). We found that a combination under DCS was required for successful enrollment in PrEP, with online strategies majorly tending to enroll adolescents of a higher socioeconomic status. Our findings reinforce the need for DCS that actively reaches out to all adolescents at the greatest risk for HIV infection, irrespective of their socioeconomic status.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Youth and adolescents from low- and middle-income countries (LMIC) face barriers to HIV prevention (Patton et al., 2016) and are exposed to multiple factors that increase their risk for HIV infection. Such factors may operate at the individual level (e.g., low level of education, use of psychoactive substances, difficulty in talking about sexuality at one’s home and/or at school) (Felisbino-Mendes et al., 2018; Jarrett et al., 2018; Magno et al., 2022;), the programmatic level (e.g., limited availability of HIV prevention services, exigence of parental consent for consultations) (DeMaria et al., 2009; Magno et al., 2022), and the structural level (e.g., conservative environment, absence of legislative protection against sexual coercion, violence, and discrimination for adolescents) (Dubov et al., 2018; Magno et al., 2022, 2019a, b; Melesse et al., 2020).

HIV infections are increasing among adolescents in different regions of the world, including LMIC (UNAIDS, 2020). In Latin America, the epidemic is concentrated among key populations, particularly men who have sex with men (MSM) and transgender women (TGW) (UNAIDS, 2020). In Brazil, surveys using respondent-driven sampling (RDS) showed a high-HIV prevalence among adults MSM (Kerr et al., 2013, 2018) and TGW (Bastos et al., 2018; Grinsztejn et al., 2017).

In the last decade, the AIDS incidence rate among males aged 15 to 19 years in Brazil has increased from 3.7 cases per 100,000 inhabitants in 2009 to 6.1 in 2019—an increase of 64.9% (Brasil, 2020a). Despite the scarcity of data regarding HIV prevalence among adolescent men who have sex with men (AMSM) in Brazil, the available data seems to draw a disproportional rate for this population when compared to adolescents from the general population (Coelho et al., 2021; Saffier et al., 2017). For example, the official surveillance data on the HIV seroprevalence among male adolescents in Brazil demonstrates that over time, AMSM have a higher HIV prevalence in comparison to heterosexual boys; furthermore, there is an increasing trend among adolescents and young MSM aged 17 to 22 years old: 0.56% in 2002 (Szwarcwald et al., 2005), 1.23% in 2007 (Szwarcwald et al., 2011) and 1.32% in 2016 (Sperhacke et al., 2018). Regarding adolescent transgender women (ATGW), to the best of our knowledge, data on the burden of the HIV epidemic in this group is still lacking.

HIV combination prevention strategies have been proposed to reduce infection rates, including pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP), with recent data regarding its effectiveness and feasibility from different countries such as South Africa (Celum et al., 2019), USA (Hosek et al., 2017a, b; Hosek et al., 2017a, b), and Brazil (Dourado et al., 2020). Nevertheless, expanding PrEP access and uptake among youth and adolescents remains a challenge (Jaspan et al., 2011; Ongwandee et al., 2018; Tolley et al., 2014). Services need to be youth-friendly, inclusive, and employ strategies to increase demand by delivering positive messaging about the benefits of PrEP as a component of HIV combination prevention (Celum et al., 2019; Dourado et al., 2020).

In the last decade, several strategies to boost demand targeting youth and adolescents (Maloney et al., 2020) have been used in demonstration studies, clinical trials, and health services aiming to increase the coverage and effectiveness of HIV prevention control measures (Ongwandee et al., 2018). Such strategies include peer recruitment (Lightfoot et al., 2018; Ongwandee et al., 2018), peer-facilitated community-based interventions (Rose-Clarke et al., 2019), interventions on online platforms (Du Bois et al., 2012), and mobile apps (Ippoliti & L’Engle, 2017; Sullivan & Hightow-Weidman, 2021), among others.

Despite these efforts, studies analyzing the effectiveness of strategies used for demand creation are still scarce, especially concerning adolescents at greater risk for HIV infection (Bradley et al., 2020). To contribute to filling this gap, we aimed to analyze: i) the effectiveness of demand creation strategies (DCS) to enroll AMSM and ATGW into an HIV combination prevention study in Brazil; ii) the predictors of DCS for adolescents’ enrollment, and iii) the factors associated with DCS by comparing online and face-to-face strategies for enrollment.

Method

Study Design and Population

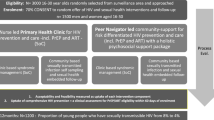

DCS were employed as part of a demonstration project titled PrEP1519, which aimed at analyzing the effectiveness of PrEP and other HIV combination prevention methods among AMSM and ATGW aged between 15 and 19 years, ongoing in PrEP clinics across three capital cities in Brazil: Belo Horizonte (located at a youth reference center), Salvador (located at a Diversity Center that advocates for Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer, Intersexual and other LGBTQI + rights), and São Paulo (located in an HIV testing and counseling center). All peer educators (young MSM or TGW) and health professionals working on the demonstration project were trained. The DCS were implemented from February 2019 to February 2021.

DCS and Data Collection

A summary of the DCS can be found in Table 1. These strategies were the same across all three sites, while respecting the cultural differences of each region.

Approaching and communicating with a target population is a key element for the success of any DCS (Bradley et al., 2020). Aiming to map out where AMSM and ATGW hung out in each city, the implementation of the PrEP clinics was preceded by a formative research, which employed direct observation of social venues, and in-depth interviews and focus groups with key informants (Zucchi et al., 2021). Besides mapping the venues, interviews and focus groups were employed to explore adolescents’ prior knowledge and acceptability of PrEP, their sexual behavior and HIV and sexually transmitted infections (STI) prevention behavior, and their opinion about the DCS planned by the study to reach out ATGW and AMSM.

The DCS developed by the study included face-to-face and online approaches. Both included discussions regarding sexual orientation and gender identity, sexual behavior, and HIV prevention, as well as the distribution of HIV self-test (HIVST), condoms, lubricants, and douching supplies (in the case of online approaches, the prevention supplies were sent to participants by mail or picked up at PrEP services, according to participants’ preference). From mid-March of 2020 onward, face-to-face activities were adapted to online activities due to the COVID-19 pandemic (Dourado et al., 2020).

All adolescents who accessed the DCS received pertinent information about the study, and those who agreed to participate signed an assent or a consent form as needed. Those presenting a high risk of or vulnerability to HIV infection (i.e., unprotected anal sex in the last 6 months, previous episode of STI or use of HIV post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) in the last 12 months, frequent use of alcohol or drugs before or during sexual intercourse, transactional or commercial sex, or experiences of discrimination and violence) were invited to enroll in the PrEP clinics. After evaluation from a provider, participants were able to choose, with assistance from the provider, which of the study arms they would like to be enrolled in: (i) the PrEP arm, which included daily use of oral PrEP along with the TDF/FTC combination, or (ii) the non-PrEP arm, in which participants who were PrEP-eligible but chose not to use PrEP had access to other HIV combination prevention methods (i.e., counseling, condoms, lubricant, douche, PEP, and HIVST). In both cases, quarterly follow-ups included medical consultations, HIV and STI testing, counseling, and access to prevention supplies. Participants received a reimbursement to cover transportation expenses.

All AMSM and ATGW, aged between 15 and 19 years, identified through DCS (i.e., online, face-to-face peer recruitment, direct referrals, and NGO) were invited to answer a recruitment questionnaire. When the participants arrived at the PrEP clinics for enrollment, they were invited to answer a more detailed socio-behavioral questionnaire (e.g., demographics, sexual behavior, drug use, STI, discrimination, and violence). For this analysis, data from both of these questionnaires were used.

Data from the two questionnaires were recorded by the peer educator or health provider in an online database platform. The recruitment questionnaire had a unique automatic code that was linked by the health provider to the socio-behavioral questionnaire when the participant arrived at the PrEP clinic, thereby preventing duplication. Adolescents who were approached more than once were categorized using the information from the first contact such individuals could be identified when they used the same social media profile or when they provided information at PrEP clinics.

Study Variables

The outcomes were as follows: (i) DCS across four categories (i.e., online, face-to-face peer recruitment, direct referrals, and NGO); and (ii) DCS dichotomized into “online” (i.e., only online recruitment) and “face-to-face” (i.e., peer recruitment face-to-face, direct referrals, and NGO) (Fig. 1).

Socioeconomic status (low, middle, and high) was based on the latent class analysis (LCA) of the following variables: having sought employment in the last month (yes, no); having a landline at home (yes, no); owning a cell phone (yes, no); owning a computer (yes, no); having access to the internet (yes, no); housemate having a car (yes, no); employing a house cleaner at home (yes, no). To identify the best LCA model, the Akaike information criterion and the Schwarz–Bayesian information criterion were used, assuming the lowest values to provide the best fit. Moreover, model selection was based on the parsimony and separation of the classes. Other predictor variables are presented in Fig. 1.

Data Analysis

Firstly, we conducted a descriptive analysis of the DCS based on the recruitment questionnaire across four categories (i.e., online, face-to-face peer recruitment, direct referrals, and NGO), stratified into time periods before and during the COVID-19 pandemic across the three cities (mid-March 2020). In the bivariate analysis, we initially analyzed predictors of DCS (four categories) for adolescents’ enrollment, based on the socio-behavioral questionnaire, and stratified by the study arms. Fisher exact tests were used to test the associations. In the multivariate analysis, DCS was recategorized as (i) “online” (i.e., only online recruitment) and (ii) “face-to-face” (i.e., peer recruitment face-to-face, direct referrals, and NGO). Multivariate analysis was conducted using logistic regression models, estimating the adjusted odds ratios (aOR) for factors associated with DCS and comparing online and face-to-face strategies for enrollment. To select the variables to be included in the logistic regression model, the P value was set at ≤ 0.20 in the bivariate analysis. After this, the variables were selected based on the literature review and statistical significance (p < 0.05) using backward elimination, and with satisfactory residual analysis, maintained within the final model. The fit of the model was assessed using the Hosmer–Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test. These analyses were conducted using the program R, version 4.0.3.

Ethical Consideration and Approval

This study was conducted in accordance with the guidelines from the Brazilian Research Ethics Commission Resolution 466/2012. The protocol was approved by the Research Ethics Committees of the World Health Organization (Protocol ID: Fiotec-PrEP Adolescent study) and the three Brazilian universities at each site (USP, UFBA, and UFMG). Written informed consent (WIC) was sought and obtained from the adolescents aged 18 and 19 years old. For those under 18, each city followed a different protocol, as per local court decisions: in Belo Horizonte, the WIC had to be signed by the parents or guardian, followed by the assent form (AF) signed by the adolescents; in Salvador, there were two possibilities: (i) WIC signed by a parent or guardian and AF by the adolescent; or (ii) just AF signed by the adolescent, in which case the team’s psychologist and social worker judged that their family ties had been broken or that they were at risk of physical, psychological, or moral violence due to their sexual orientation; and in São Paulo a judicial decision allowed a waiver of parental consent, which is why just the AF signed by the adolescents was enough to be able to join the study. All participants could withdraw participation at any stage of the process or skip any questions they perceived as too sensitive, personal, or distressing.

Results

Overall, 4,529 AMSM and ATGW were reached by the DCS, most of them via online strategies (73.8%), followed by face-to-face peer recruitment (14.8%), direct referrals (8.4%), and NGO recruitment (3.0%) (Fig. 2). During the COVID-19 pandemic period, there was a substantial increase in online recruitment (from 31.3 to 68.7%) and a decrease in face-to-face recruitment (from 78.1 to 21.9%), direct referrals (from 72.0 to 28.0%), and NGO strategies (from 99.3 to 0.7%) (Table 2).

Of the total number of individuals reached by the DCS, 20.6% (935/4529) were enrolled in the PrEP1519 study; of those, 76.6% (716/935) started using PrEP, and 23.4% (219/935) chose other HIV prevention methods (non-PrEP arm). The DCS that enrolled most adolescents in PrEP and non-PrEP was via online methods (328/716 and 92/219, respectively) and direct referrals (235/716 and 84/219, respectively). However, in terms of effectiveness, enrolling adolescents in the PrEP arm was greater via direct referrals (235/382) and face-to-face recruitment (139/670) than online strategies (328/3342). In the same way, regarding enrolling adolescents in the non-PrEP arm, direct referrals (84/382) and face-to-face recruitment (35/670) were more effective than online strategies were (92/3,342) (Table 2).

Most adolescents enrolled in the PrEP1519 study were enrolled in the São Paulo site (47.7%) and before the COVID-19 pandemic (52.5%). Furthermore, most were AMSM (92.0%); had a lower (34.6%) and middle (38.8%) socioeconomic status; had 12 or more years of schooling (52.1%); self-identified as black skin color (68.0%); were aged between 18 and 19 years (79.9%); were living with parents or relatives (80.1%); and did not participate in organized social movements or LGBTQI + NGO (88.0%). As for their sexual behavior, 21.4% reported having had an STI in the previous 12 months, 32.9% reported drug or alcohol use before or during sex, and 14.3% reported exchanging sex for money or favors. Moreover, most reported condomless anal sex in the past 3 months (79.3%), had their sexual debut at age 15 or under (62.8%); had not used a condom during their first sexual experience (54.2%); and reported prior PrEP knowledge (71.4%). Most had a perception of the moderate risk of HIV infection (46.1%). Concerning experiences of violence and discrimination, 33.0% said they experienced some form of discrimination or violence due to their sexual orientation or gender identity, and 28.5% reported an episode of sexual violence (Table 3).

In the bivariate analysis of predictors of DCS across the four categories, we observed that online strategies resulted in the recruitment of the following profile of enrollment in the PrEP arm: AMSM (48.4%), from the São Paulo site (57.4%), recruited during the COVID-19 pandemic period (60.6%), with a high socioeconomic status (59.1%), with 12 years or more of education (48.9%), and aged 18 or 19 years (47.1%). On the other hand, direct referrals played an important role in recruiting for PrEP enrollment, before the COVID-19 pandemic period (44.9%) and reached a higher proportion of TGW (44.4%) and participants with lower socioeconomic status (49.1%). In the non-PrEP arm, the online strategies played a part in enrolling a higher proportion of AMSM (43.5%), from the Salvador site (62.5%), during the COVID-19 pandemic period (75.3%), reaching those with a higher socioeconomic status (59.1%), and who had a high-HIV risk perception (72.4%). In addition, direct referrals resulted in a higher proportion of TGW (58.3%) being recruited for the non-PrEP arm, before the COVID-19 pandemic period (53.1%), reaching participants with lower socioeconomic status (53.5%) and low perception of an HIV risk (47.2%) (Table 3).

Table 4 shows the bivariate and multivariate analyses of factors associated with DCS comparing online and face-to-face strategies for enrollment. In the multivariate analysis, the odds of being enrolled in PrEP through an online strategy was greater among AMSM (aOR = 3.65; 95%CI: 1.74–8.28), those with middle (aOR = 3.24; 95%CI: 1.61–6.63) and higher socioeconomic levels (aOR = 3.36; 95%CI: 1.34–8.95), living with parents or relatives (aOR = 1.63; 95%CI: 1.02–2.62), and during the COVID-19 pandemic (aOR = 1.67; 95%CI: 1.06–2.61). Furthermore, the odds of being enrolled in the non-PrEP arm were greater among those with middle and higher socioeconomic levels (aOR = 3.22; 95%CI: 1.10–9.55; aOR = 4.23; 95%CI: 1.25–14.63, respectively), those who had a high-HIV risk perception (aOR = 4.32; 95%CI: 1.32–15.35), and during the COVID-19 pandemic (aOR = 6.32; 95%CI: 2.36–17.76).

Discussion

Our results demonstrate that the different DCS reached different profiles of AMSM and ATGW. Although online DCS reached a higher number of adolescents, it were less efficient in recruiting adolescents who were actually enrolled in PrEP than face-to-face strategies, which were also more capable of recruiting those at higher socioeconomic vulnerability. Moreover, we highlight the increase in the adolescents reached through online strategies and the decrease in face-to-face strategies during the COVID-19 pandemic, which resulted in a higher proportion of enrollments for PrEP and non-PrEP via online strategies during this period.

The COVID-19 pandemic may have contributed to an increase in the vulnerability of AMSM and ATGW to HIV infection (Grangeiro et al., 2021) because it affected their access to HIV prevention and testing services in various countries (Rao et al., 2021; Sanchez et al., 2020). Nevertheless, in our study, the proportion of enrolled participants was similar (52.5% pre- and 47.5% during the COVID-19 pandemic) and the PrEP1519 contingency plan, which included the intensification of online strategies during the pandemic, may have contributed to that result. Based on this contingency plan, PrEP1519 clinics continued their work during the pandemic and were able to adapt quickly to the new situation using a social media and telemonitoring infrastructure (Dourado et al., 2020; Magno et al., 2021).

The adolescents enrolled in the PrEP1519 study had a high social vulnerability, low socioeconomic status, and often engaged in high-risk sexual behavior. Unlike our study, in the Brazilian National Health System (in Portuguese: Sistema Único de Saúde–SUS) PrEP Program, where PrEP is only available for individuals aged 18 or above (as of 2022, PrEP became available for people over 15 years old), most PrEP users are white, with a high level of schooling, and aged between 30 and 39 years (Brasil, 2020b). The intersection of race, sexuality, and age is important because discrimination against black male adolescents is a well-documented reality in Brazil, especially in schools, and generally manifests indirectly in social relations, with individuals being differentiated according to their ethnic background (Guimarães & Pinto, 2016; Magno et al., 2022). The high enrollment of participants with black skin color in the PrEP1519 study differs from studies with adolescents carried out in the USA (Bradley et al., 2020).

ATGW are harder to engage both in PrEP and other HIV combination prevention methods when compared to AMSM. This suggests that despite efforts made using different DCS, the high social vulnerability of TGW and the social context of stigma and discrimination may have influenced their access to the study (Magno et al., 2019a, b). Other Brazilian studies have shown that TGW face discrimination in various spheres of their lives from adolescence onward, and tend to have limited access to education/training, formal employment, and social services in general, especially health services (Magno et al., 2018a, b; Soares et al., 2019).

The higher number of adolescents reached by the online DCS can be explained as the result of using a strategy that is compatible with the social dynamics of young people. It is also noteworthy that almost 81% of all online recruitment was conducted through dating or “hook-up” apps, which demonstrates that adolescents are more willing to talk about prevention in these spaces because they are at a greater risk of HIV infection (Chan et al., 2018). Online platforms and app-based prevention strategies were found as important tools to disseminate knowledge and promote healthier attitudes and practices among young people around the world (Maloney et al., 2020; Sullivan & Hightow-Weidman, 2021; Whiteley et al., 2018). In our study, the online strategy mediated by peer educators attracted the attention of and enrolled adolescents at high risk of HIV in PrEP and other combination prevention strategies.

The main limitation of the online DCS is that it tended to attract those AMSM with higher levels of schooling and income. This result can be explained by the unequal access to digital technologies in Brazil, such as computers, tablets, smartphones, and internet connection (Nishijima et al., 2017). A Chicago-based study with MSM analyzing online youth recruitment for HIV prevention found that Black and Latino youth used the internet less than their white peers, and that blacks were less likely to be recruited online than whites (Du Bois et al., 2012). This unequal access to digital technologies, known as the digital divide, affects several marginalized population groups (Chesser et al., 2016).

In this sense, studies have shown that face-to-face strategies and referrals from health services play a crucial role in reaching out to adolescents with greater social vulnerability, as we saw in our findings. During the implementation of a test-and-treat and HIV prevention program in Thailand in 2015 and 2016, peer-driven recruitment was effective for recruiting MSM and TGW living with HIV for treatment, and in recruiting MSM and TGW at high risk for HIV infection (Ongwandee et al., 2018).

Only one-fifth of the participants approached joined the study. This indicates that reaching out to and creating demand for HIV prevention among AMSM and ATGW requires a broad view that takes into account the diversity of individuals, their access to HIV prevention methods, health services, and the structural and political scenario underlying the HIV response. In contexts of growing conservatism in Brazil in the recent past and present day, comprehensive sex education has been undermined at schools.

An overwhelming silence about HIV and STI can be observed in the mainstream media. In recent years, issues pertaining to sex are not discussed at home or at school, primarily because of the rise of religious and political conservatism (Paiva et al., 2020; Reis Brandão & Cabral, 2019). In other LMIC, sexual health education programs for adolescents are still a challenge (DeMaria et al., 2009; Mashora et al., 2019; Melesse et al., 2020), which means this educational void tends to be filled by the internet (Burki, 2016). Furthermore, when an adolescent’s sexual orientation or gender identity does not conform to prevailing cisgender and heteronormative standards, they tend to be more vulnerable socially and programmatically, which is further aggravated by stigma and discrimination (Hatzenbuehler & Pachankis, 2016; Peng et al., 2019).

Therefore, an important factor for encouraging the engagement of AMSM and ATGW in HIV prevention services is to provide friendly services, free of sexuality- and gender-related stigma and discrimination. Consequently, considering the context of the three study sites, recruiting and enrolling AMSM and ATGW in a PrEP demonstration study in this scenario required the development of a variety of DCS. As such, face-to-face DCS of the PrEP1519 study can also be seen as interventions that created physical spaces, networks, and social gathering; used networks as well as personal and social competences/skills of participants and peer educators; used preexisting networks and activities in the community, and promoted community-based HIV testing in youth hotspots.

The limits of this study also include the convenience sampling method and the inclusion of the COVID-19 pandemic period, which disrupted face-to-face DCS, which could explain why more people were reached via online strategies. Furthermore, most of the study population were 18–19 years of age, which may limit generalization to younger adolescents. Nonetheless, the study was able to develop and analyze DCS that enrolled a diverse group of AMSM and ATGW, indicating that they are interested in PrEP and other HIV combination prevention once they are made aware of the same.

Conclusion

Recruiting AMSM and ATGW with different socioeconomic and behavioral profiles for HIV prevention services requires a combination of DCS. Our study points out the need for DCS that do not solely depend on spontaneous demand from health services, but which actively reach out to adolescents among populations at the greatest risk for HIV infection, while respecting their specific needs and choices and adopting local strategies for demand creation, recruitment, monitoring, and trained health care providers and peer educators. Moreover, the findings have been shared with the Brazilian Ministry of Health, with the aim to help in the establishment of a comprehensive network of public services which are able to tackle the particularities and needs of this highly vulnerable population, which includes, but is not limited, to stigma-free access to all HIV/STI combination prevention strategies.

Data Availability

Data and materials cannot be shared publicly because of their sensitive content. The informed consent process prior to participation ensured confidentiality and anonymity and that only investigators of the PrEP1519 project would be allowed to access the data collected. With these conditions assured, ethical approval was obtained from the Research Ethics Review Committees of the Universidade de São Paulo (protocol number 70798017.3.0000.0065), Universidade Federal da Bahia (protocol number 01691718.1.0000.5030), and Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais (protocol number 17750313.0.0000.5149). In the best interest of protecting participants’ confidentiality and anonymity, researchers may contact the Research Ethics Committee of Universidade de São Paulo, (Comissão de Ética para Análise de Projetos de Pesquisa, email: cappesq.adm@hc.fm.usp.br), to make requests related to access to the data used for the analyses in this manuscript.

Abbreviations

- AF:

-

Assent form

- AMSM:

-

Adolescent men who have sex with men

- aOR:

-

Adjusted odds ratio

- ATGW:

-

Adolescent transgender women

- DCS:

-

Demand creation strategies

- LCA:

-

Latent class analysis

- LGBTQI + :

-

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, intersexual, and others

- NGO:

-

Non-governmental organization

- PrEP:

-

HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis

- STI:

-

Sexually transmitted infections

- WIC:

-

Written informed consent

- USP:

-

University of São Paulo

- UFBA:

-

Federal University of Bahia

- UFMG:

-

Federal University of Minas Gerais

References

Bastos, F. I., Bastos, L. S., Coutinho, C., et al. (2018). HIV, HCV, HBV, and syphilis among transgender women from Brazil: Assessing different methods to adjust infection rates of a hard-to-reach, sparse population. Medicine (Baltimore), 97, S16–S24. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000009447

Bradley, E. L. P., Lanier, Y., Ukuku Miller, A. M., Brawner, B. M., & Sutton, M. Y. (2020). Successfully recruiting black and Hispanic/Latino adolescents for sexually transmitted infection and HIV prevention research. Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities, 7(1), 36–44. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-019-00631-7

Brasil. (2020a). Boletim epidemiológico HIV/AIDS. http://www.aids.gov.br/pt-br/pub/2020a/boletim-epidemiologico-hivaids-2020a

Brasil. (2020b). Painel PrEP. Departamento de Doenças de Condições Crônicas e Infecções Sexualmente Transmissíveis. Ministério da Saúde. http://www.aids.gov.br/pt-br/painel-prep

Burki, T. (2016). Sex education in China leaves young vulnerable to infection. Lancet. Infectious Diseases, 16(1), 26. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(15)00494-6

Celum, C. L., Delany-Moretlwe, S., Baeten, J. M., van der Straten, A., Hosek, S., Bukusi, E. A., McConnell, M., Barnabas, R. V., & Bekker, L. G. (2019). HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis for adolescent girls and young women in Africa: From efficacy trials to delivery. Journal of the International AIDS Society, 22(Suppl. 4), e25298. https://doi.org/10.1002/jia2.25298

Chan, P. A., Crowley, C., Rose, J. S., Kershaw, T., Tributino, A., Montgomery, M. C., Almonte, A., Raifman, J., Patel, R., & Nunn, A. (2018). A network analysis of sexually transmitted diseases and online hookup sites among men who have sex with men. Sexually Transmitted Diseases, 45(7), 462–468. https://doi.org/10.1097/OLQ.0000000000000784

Chesser, A., Burke, A., Reyes, J., & Rohrberg, T. (2016). Navigating the digital divide: A systematic review of eHealth literacy in underserved populations in the United States. Informatics for Health and Social Care, 41(1), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.3109/17538157.2014.948171

Coelho, L. E., Torres, T. S., Veloso, V. G., Grinsztejn, B., Jalil, E. M., Wilson, E. C., & McFarland, W. (2021). The prevalence of HIV among men who have sex with men (MSM) and young MSM in Latin America and the Caribbean: A systematic review. AIDS and Behavior, 25(10), 3223–3237. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-021-03180-5

DeMaria, L. M., Galárraga, O., Campero, L., & Walker, D. M. (2009). Educación sobre sexualidad y prevención del VIH: Un diagnóstico para América Latina y el caribe. Revista panamericana de Salud Pública, 26(6), 871. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1020-49892009001200003

Dourado, I., Magno, L., Soares, F., Massa, P., Nunn, A., Dalal, S., Grangeiro, A., et al. (2020). Adapting to the COVID-19 pandemic: Continuing HIV prevention services for adolescents through telemonitoring Brazil. AIDS and Behavior, 24(7), 1994–1999. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-020-02927-w

Du Bois, S. N., Johnson, S. E., & Mustanski, B. (2012). Examining racial and ethnic minority differences among YMSM during recruitment for an online HIV prevention intervention study. AIDS and Behavior, 16(6), 1430–1435. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-011-0058-0

Dubov, A., Galbo, P., Jr., Altice, F. L., & Fraenkel, L. (2018). Stigma and shame experiences by MSM who take PrEP for HIV prevention: A qualitative study. American Journal of Men’s Health, 12(6), 1843–1854. https://doi.org/10.1177/1557988318797437

Felisbino-Mendes, M. S., Paula, T. F., Machado, Í. E., Oliveira-Campos, M., & Malta, D. C. (2018). Analysis of sexual and reproductive health indicators of Brazilian adolescents, 2009, 2012 and 2015 and 2015. Revista Brasileira De Epidemiologia, 21(suppl 1), e180013. https://doi.org/10.1590/1980-549720180013.supl.1

Grangeiro, A., Magno, L., Ferraz, D., Escuder, M.M., Zucchi, E.M., Koyama, M., Massa, P., Soares, F., Santos, L.A., Westin, M., Préau, M., Mabire, X., Dourado, I (18–21 July 2021). High risk sexual behavior, access to HIV prevention services and HIV incidence during the COVID-19 pandemic among men who have sex with men and transgender women in Brazil. 11th IAS Conference on HIV Science, Berlim. https://theprogramme.ias2021.org/Abstract/Abstract/1187

Grinsztejn, B., Jalil, E. M., Monteiro, L., Velasque, L., Moreira, R. I., Garcia, A. C. F., Castro, C. V., Krüger, A., Luz, P. M., Liu, A. Y., McFarland, W., Buchbinder, S., Veloso, V. G., & Wilson, E. C. (2017). Unveiling of HIV dynamics among transgender women: A respondent-driven sampling study in Rio de Janeiro Brazil. Lancet HIV, 4(4), e169–e176. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2352-3018(17)30015-2

Guimarães, A. C., & Pintod, J. M. (2016). Racial discrimination at school: Black youth experiences. Revista Digital De Direito Administrativo, 3(3), 512–524. https://doi.org/10.11606/issn.2319-0558.v3i3p512-524

Hatzenbuehler, M. L., & Pachankis, J. E. (2016). Stigma and minority stress as social determinants of health among lesbian, Gay, bisexual, and transgender youth: Research evidence and clinical implications. Pediatric Clinics of North America, 63(6), 985–997. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pcl.2016.07.003

Hosek, S. G., Landovitz, R. J., Kapogiannis, B., Siberry, G. K., Rudy, B., Rutledge, B., Liu, N., Harris, D. R., Mulligan, K., Zimet, G., Mayer, K. H., Anderson, P., Kiser, J. J., Lally, M., Brothers, J., Bojan, K., Rooney, J., & Wilson, C. M. (2017a). Safety and feasibility of antiretroviral preexposure prophylaxis for adolescent men who have sex with men aged 15 to 17 years in the United States. JAMA Pediatrics, 171(11), 1063–1071. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2017.2007

Hosek, S. G., Rudy, B., Landovitz, R., Kapogiannis, B., Siberry, G., Rutledge, B., Liu, N., Brothers, J., Mulligan, K., Zimet, G., Lally, M., Mayer, K. H., Anderson, P., Kiser, J., Rooney, J. F., Wilson, C. M., Network, A. T., & (ATN) for HIVAIDS Interventions. (2017b). An HIV preexposure prophylaxis demonstration project and safety study for young MSM. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 74(1), 21–29. https://doi.org/10.1097/QAI.0000000000001179

Ippoliti, N. B., & L’Engle, K. (2017). Meet us on the phone: Mobile phone programs for adolescent sexual and reproductive health in low-to-middle income countries. Reproductive Health, 14(1), 11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-016-0276-z

Jarrett, S. B., Udell, W., Sutherland, S., McFarland, W., Scott, M., & Skyers, N. (2018). Age at sexual initiation and sexual and health risk behaviors among Jamaican adolescents and young adults. AIDS and Behavior, 22, 57–64. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-018-2058-9

Jaspan, H. B., Flisher, A. J., Myer, L., Mathews, C., Middelkoop, K., Mark, D., & Bekker, L. G. (2011). Sexual health, HIV risk, and retention in an adolescent HIV-prevention trial preparatory cohort. Journal of Adolescent Health, 49(1), 42–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.10.009

Kerr, L. R., Mota, R. S., Kendall, C., Pinho, Ade A., Mello, M. B., Guimarães, M. D., Dourado, I., de Brito, A. M., Benzaken, A., McFarland, W., Rutherford, G., & HIVMSM Surveillance Group. (2013). HIV among MSM in a large middle-income country. AIDS, 27(3), 427–435. doi: https://doi.org/10.1097/QAD.0b013e32835ad504

Kerr, L., Kendall, C., Guimarães, M. D. C., Salani Mota, R., Veras, M. A., Dourado, I., Maria de Brito, A., Merchan-Hamann, E., Pontes, A. K., Leal, A. F., Knauth, D., Castro, A. R. C. M., Macena, R. H. M., Lima, L. N. C., Oliveira, L. C., Cavalcantee, M. D. S., Benzaken, A. S., Pereira, G., Pimenta, C., & Johnston, L. G. (2018). HIV prevalence among men who have sex with men in Brazil: Results of the 2nd national survey using respondent-driven sampling. Medicine (Baltimore), 97, S9–S15. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000010573

Lightfoot, M. A., Campbell, C. K., Moss, N., Treves-Kagan, S., Agnew, E., Kang Dufour, M. S., Scott, H., Saʼid, A. M., & Lippman, S. A. (2018). Using a social network strategy to distribute HIV self-test kits to African American and Latino MSM. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 79(1), 38–45. https://doi.org/10.1097/QAI.0000000000001726

Magno, L., Medeiros, D., Soares, F., Jefferson, C., Duarte, F. M., Grangeiro, A., & Dourado, I. (2021). Demand creation and HIV self-testing delivery during COVID-19 contingency measures of physical distancing among adolescents’ key population enrolled in Brazil. Oral abstracts of the 11th IAS Conference on HIV Science, 18–21 July 2021. doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/jia2.25755

Magno, L., Dourado, I., & Silva, L. A. V. D. (2018a). Stigma and resistance among travestis and transsexual women in Salvador, Bahia State, Brazil [Estigma e resistencia entre travestis e mulheres transexuais em Salvador, Bahia, Brasil]. Cadernos De Saúde Pública, 34(5), e00135917. https://doi.org/10.1590/0102-311x00135917

Magno, L., Dourado, I., Silva, L. A. V. D., Brignol, S., Amorim, L., & MacCarthy, S. (2018b). Gender-based discrimination and unprotected receptive anal intercourse among transgender women in Brazil: A mixed methods study. PLoS ONE, 13(4), e0194306. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0194306

Magno, L., Dourado, I., Sutten Coats, C., Wilhite, D., da Silva, L. A. V., Oni-Orisan, O., Brown, J., Soares, F., Kerr, L., Ransome, Y., Chan, P. A., & Nunn, A. (2019a). Knowledge and willingness to use pre-exposure prophylaxis among men who have sex with men in Northeastern Brazil. Global Public Health, 14(8), 1098–1111. https://doi.org/10.1080/17441692.2019.1571090

Magno, L., Marinho, L. F. B., Zucchi, E. M., Amaral, A. M. S., Lobo, T. C. B., Paes, HCd. S., Lima, GMd. B., Nunes, C. C. S., Pereira, M., & Dourado, I. (2022). School-based sexual and reproductive health education for young people from low-income neighbourhoods in Northeastern Brazil: The role of communities, teachers, health providers, religious conservatism, and racial discrimination. Sex Education, 1, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681811.2022.2047017

Magno, L., Silva, L. A. V. D., Veras, M. A., Pereira-Santos, M., & Dourado, I. (2019b). Stigma and discrimination related to gender identity and vulnerability to HIV/AIDS among transgender women: A systematic review [Estigma e discriminacao relacionados a identidade de genero e a vulnerabilidade ao HIV/AIDS entre mulheres transgenero: Revisao sistematica]. Cadernos De Saúde Pública, 35(4), e00112718. https://doi.org/10.1590/0102-311X00112718

Maloney, K. M., Bratcher, A., Wilkerson, R., & Sullivan, P. S. (2020). Electronic and other new media technology interventions for HIV care and prevention: A systematic review. Journal of the International AIDS Society, 23(1), e25439. https://doi.org/10.1002/jia2.25439

Mashora, M. C., Dzinamarira, T., & Muvunyi, C. M. (2019). Barriers to the implementation of sexual and reproductive health education programmes in low-income and middle-income countries: A scoping review protocol. British Medical Journal Open, 9(10), e030814. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2019-030814

Melesse, D. Y., Mutua, M. K., Choudhury, A., Wado, Y. D., Faye, C. M., Neal, S., & Boerma, T. (2020). Adolescent sexual and reproductive health in sub-Saharan Africa: Who is left behind? BMJ Global Health, 5(1), e002231. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2019-002231

Nishijima, M., Ivanauskas, T. M., & Sarti, F. M. (2017). Evolution and determinants of digital divide in Brazil (2005–2013). Telecommunications Policy, 41(1), 12–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.telpol.2016.10.004

Ongwandee, S., Lertpiriyasuwat, C., Khawcharoenporn, T., Chetchotisak, P., Thiansukhon, E., Leerattanapetch, N., Leungwaranan, B., Manopaiboon, C., Phoorisri, T., Visavakum, P., Jetsawang, B., Poolsawat, M., Nookhai, S., Vasanti-Uppapokakorn, M., Karuchit, S., Kittinunvorakoon, C., Mock, P., Prybylski, D., Sukkul, A. C., & Martin, M. (2018). Implementation of a test, treat, and prevent HIV program among men who have sex with men and transgender women in Thailand, 2015–2016. PLoS One, 13(7), e0201171. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0201171

Paiva, V., Antunes, M. C., & Sanchez, M. N. (2020) Odireito à prevenção da Aids em tempos de retrocesso: Religiosidade e sexualidade na escola. Interface – Comunicação Saúde Educação, 24: 871. doi: https://doi.org/10.1590/interface.180625

Patton, G. C., Sawyer, S. M., Santelli, J. S., Ross, D. A., Afifi, R., Allen, N. B., Arora, M., Azzopardi, P., Baldwin, W., Bonell, C., Kakuma, R., Kennedy, E., Mahon, J., McGovern, T., Mokdad, A. H., Patel, V., Petroni, S., Reavley, N., Taiwo, K., & Viner, R. M. (2016). Our future: A lancet commission on adolescent health and wellbeing. Lancet, 387(10036), 2423–2478. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00579-1

Peng, K., Zhu, X., Gillespie, A., Wang, Y., Gao, Y., Xin, Y., Qi, J., Ou, J., Zhong, S., Zhao, L., Liu, J., Wang, C., & Chen, R. (2019). Self-reported rates of abuse, neglect, and bullying experienced by transgender and gender-nonbinary adolescents in China. JAMA Network Open, 2(9), e1911058. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.11058

Rao, A., Rucinski, K., Jarrett, B. A., Ackerman, B., Wallach, S., Marcus, J., Adamson, T., Garner, A., Santos, G. M., Beyrer, C., Howell, S., & Baral, S. (2021). Perceived interruptions to HIV prevention and treatment services associated with COVID-19 for Gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men in 20 countries. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 87(1), 644–651. https://doi.org/10.1097/QAI.0000000000002620

Reis Brandão, E., & Cabral, C. D. S. (2019). Sexual and reproductive rights under attack: The advance of political and moral conservatism in Brazil. Sexual and Reproductive Health Matters, 27(2), 1669338. https://doi.org/10.1080/26410397.2019.1669338

Rose-Clarke, K., Bentley, A., Marston, C., & Prost, A. (2019). Peer-facilitated community-based interventions for adolescent health in low- and middle-income countries: A systematic review. PLoS One, 14(1), e0210468. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0210468

Saffier, I. P., Kawa, H., & Harling, G. (2017). A scoping review of prevalence, incidence and risk factors for HIV infection amongst young people in Brazil. BMC Infectious Diseases, 17(1), 675. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-017-2795-9

Sanchez, T. H., Zlotorzynska, M., Rai, M., & Baral, S. D. (2020). Characterizing the impact of COVID-19 on men who have sex with men across the United States in April, 2020. AIDS and Behavior, 24(7), 2024–2032. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-020-02894-2

Soares, F., MacCarthy, S., Magno, L., da Silva, L. A. V., Amorim, L., Nunn, A., Oldenburg, C. E., Dourado, I., & PopTrans Group. (2019). Factors associated with PrEP refusal among transgender women in Northeastern Brazil. AIDS and Behavior, 23(10), 2710–2718. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-019-02501-z

Sperhacke, R. D., da Motta, L. R., Kato, S. K., Vanni, A. C., Paganella, M. P., Oliveira, M. C. P., Pereira, G. F. M., & Benzaken, A. S. (2018). HIV prevalence and sexual behavior among young male conscripts in the Brazilian army, 2016. Medicine (Baltimore), 97, S25–S31. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000009014

Sullivan, P. S., & Hightow-Weidman, L. (2021). Mobile apps for HIV prevention: How do they contribute to our epidemic response for adolescents and young adults? mHealth, 7, 36. https://doi.org/10.21037/mhealth-20-71

Szwarcwald, C. L., Andrade, C. L., Pascom, A. R., Fazito, E., Pereira, G. F., & Penha, I. T. (2011). HIV-related risky practices among Brazilian young men, 2007. Cadernos De Saúde Pública, 27(Suppl. 1), S19–S26. https://doi.org/10.1590/s0102-311x2011001300003

Szwarcwald, C. L., de Carvalho, M. F., Barbosa Júnior, A., Barreira, D., Speranza, F. A., & de Castilho, E. A. (2005). Temporal trends of HIV-related risk behavior among Brazilian military conscripts, 1997–2002. Clinics (sao Paulo, Brazil), 60(5), 367–374. https://doi.org/10.1590/s1807-59322005000500004

Tolley, E. E., Kaaya, S., Kaale, A., Minja, A., Bangapi, D., Kalungura, H., Headley, J. N., & Baumgartner, J. N. (2014). Comparing patterns of sexual risk among adolescent and young women in a mixed-method study in Tanzania: Implications for adolescent participation in HIV prevention trials. Journal of the International AIDS Society, 17(3), 19149. https://doi.org/10.7448/IAS.17.3.19149

UNAIDS. (2020). Global AIDS Update. Seizing the moment: Tackling entrenched inequalities to end epidemics (Global AIDS update Issue). https://www.unaids.org/en/resources/documents/2020/global-aids-report

Whiteley, L. B., Brown, L. K., Curtis, V., Ryoo, H. J., & Beausoleil, N. (2018). Publicly available Internet content as a HIV/STI prevention intervention for urban youth. Journal of Primary Prevention, 39(4), 361–370. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10935-018-0514-y

Zucchi, E. M., Couto, M. T., Castellanos, M., Dumont-Pena, É., Ferraz, D., Félix Pinheiro, T., Grangeiro, A., da Silva, L. A. V., Dourado, I., Pedrana, L., Santos, F. S. R., & Magno, L. (2021). Acceptability of daily pre-exposure prophylaxis among adolescent men who have sex with men, travestis and transgender women in Brazil: A qualitative study. PLoS ONE, 16(5), e0249293. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0249293

Funding

ID, AG, and DG are principal investigators of the PrEP1519 Study in the cities of Salvador and São Paulo, respectively, which is funded by Unitaid (Grant Number 2017–15-FIOTECPrEP). PrEP1519 Study is also funded by the Brazilian Ministry of Health, through the Department of Chronic Diseases and Sexually Transmitted Infections, Bahia State Department of Health, São Paulo State and City Department of Health, and City of São Paulo AIDS Program, by donating PrEP medications, condoms, and rapid tests and providing the necessary infrastructure for the study development.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

LM and ID contributed to conceptualization; ME, FS, and LM contributed to formal analysis; ID, AG, and DG acquired funding; LM, FS, AG, DG, and ID contributed to investigation and performed the research; LM, FS, ME, AG, and DF contributed to methodology; LM, ID, AG, and EMZ contributed to writing—original draft; LM, ID, AG, MME, EMZ, DG, and DF contributed to writing—review and editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Informed Consent

This study was conducted according to the directives derived from the Brazilian Research Ethics Commission Resolution 466/2012. The protocol was approved by the Research Ethics Review Committee of the World Health Organization (Protocol ID: Fiotec-PrEP Adolescent study) and by the three Brazilian Universities at each site (USP—protocol number 70798017.3.0000.0065, UFBA—protocol number 01691718.1.0000.5030, and UFMG—protocol number 17750313.0.0000.5149). Written informed consent and assent were asked for those who agreed to participate, and they could withdraw their consent at any stage of the process without any penalty, or even skip any questions they perceived as too sensitive, personal, or distressing.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Magno, L., Soares, F., Zucchi, E.M. et al. Reaching Out to Adolescents at High Risk of HIV Infection in Brazil: Demand Creation Strategies for PrEP and Other HIV Combination Prevention Methods. Arch Sex Behav 52, 703–719 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-022-02371-y

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-022-02371-y