Abstract

In 2005, a Swedish television documentary that revealed gross misconduct and abuse in Swedish children’s homes led to a number of inquiries that culminated with the passing of the Redress Act. This act entitled everyone that had suffered from abuse in out-of-home care to 250,000 Swedish crowns (close to 25,000 Euros). However, only 42 percent of the Swedish claimants were granted the compensation, a very low number in international comparison. The starting point of this study is this—in many accounts failed—redress process. Why did Sweden, self-appointed moral superpower, produce such deviating results? This question is addressed by an inquiry into the Swedish scheme of redress, focusing on the role of archives and recordkeeping with particular focus on the concepts of total archives and politics of regret. This paper argues that it was impossible for the Swedish Board of Redress to make satisfactory assessments of redress claims, given the set criteria and the archival material on which they were required to base their decisions, and that it is a futile task to base the writing of individual life stories on official documentation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In November 2005, the popular Swedish documentary series Documents from Within (Dokument inifrån) aired an episode called “Stolen Childhood” (“Stulen barndom”). The episode revealed gross misconduct at one of Sweden’s many children’s homes in use during the 1950s; it also suggested, furthermore, that the abuse in that particular home was not a unique case but had, in fact, occurred at many other similar institutions throughout the twentieth century. Pressured by the ensuing public outcry over the documentary’s revelations, the Swedish Minister of Health and Welfare initiated a governmental commission that produced a series of reports and culminated in the passing of the Redress Act (SFS 2012:663). This Act entitled everyone who could show that they, as children, had suffered from severe neglect, abuse, or misconduct in out-of-home care between 1920 and 1980 to 250,000 Swedish crowns (close to 25,000 Euros). When the Redress Board, responsible for assessing claimants’ stories and distributing the money, disbanded in 2016, only 42% of claimants had been granted this compensation-which meant that a whopping 58% of claims were denied, far more than in other countries with similar redress processes. In Ireland and Australia, for instance, only 6.6 and 9.7% of those who claimed compensation were denied it (Sköld et al. 2020, p 182). In Norway, a country whose geographical and socio-political closeness to Sweden might augur similar outcomes in these countries’ redress processes, the rejection rate was still a fairly low 22%.

Why did Sweden, which prides itself on high humanitarian standards and wants to be seen as a role model for human rights compliance (e.g. Trägårdh 2021), produce such deviating results? This paper will examine the anomaly of Sweden’s redress process, focusing on the role of archives and recordkeeping. As noted by a number of archival scholars in recent decades, recordkeeping so far has failed to meet the needs of children in care and of care-leavers (Golding et al. 2021, 1626).

The Swedish children’s historian Johanna Sköld and her colleagues have highlighted the inconsistent and fragmentary role of archives in the Swedish redress process (Sköld et al. 2020, 2012, 2021; Sköld and Jensen 2015).

The present study contributes to this archive-based approach to redress by compiling and refocusing known problems, discussing the concepts of total archives and politics of regret in relation to redress processes, and placing the relation between redress and archival records in a wider societal and political context.

In addition to politics of regret and total archives, this paper draws on the concept of logics to explain the Swedish redress process. By using two different logics, that of legislation and that of compassion (or emotion), it describes and elucidates the different ways of governments to relate to redress. These two logics are ever present in processes of redress, where different types of human suffering, by its nature impossible to quantify and put a price on, are to be measured, labelled and financially compensated through bureaucratic measures (Ericsson 2015, p 131).

After stating the aim and research questions, the article gives a brief overview of the theoretical concept politics of regret and a short discussion on total archives. Following this, the Swedish process of redress is described, drawing parallels and comparisons to cases of redress in other countries and briefly mentioning the struggles for redress by the Sami people in Sweden and the Finnish war children. After this setting of the scene, the records forming the foundation of redress are discussed in relation to the Swedish context, recordkeeping practices, and total archives. Thereafter, the article discusses the fragmentation of narratives in records, and in the redress process, drawing on two examples from the proceedings of the Swedish Redress Board. Following this, the redress is examined through the lens of politics of regret as well as those of different logics. The outcome of the Swedish redress scheme is then summarized and theorized upon, leading up to the conclusion, in which the results are discussed and a possible approach to the role of records in redress is suggested.

Aim and research questions

This article seeks to answer the following questions:

-

A)

What role did narratives play in the use of archival records in the Swedish redress process?

-

B)

What views on archives and archival records are implicit in the Swedish redress scheme?

-

C)

How might an archival system based on the total archive affect potential future redress processes?

To answer these questions, this study draws on different types of material. While the literature on the Swedish redress process is extensive, the reviewed research for the present study is primarily within the fields of child studies (e.g. Sköld et al. 2020) and history (e.g. Arvidsson 2016). These texts have been selected based on their focus on archives and recordkeeping and their relevance for my research questions. In her doctoral thesis To replace the irreplaceable: state redress for involuntary sterilization and neglect of children in care (2016), historian Malin Arvidsson gives a thorough review of the Swedish redress process, not only establishing a timeline for the different rounds of the process but also gathers information from a number of sources, providing wide context. Historian Johanna Sköld has published extensively on the Swedish redress process, with special emphasis on its use of archival records and the production of oral testimonies. Particularly useful to my study has been the article “Conflicting or complementing narratives?” (Sköld et al. 2012), in which Sköld, Emma Foberg, and Johanna Hedström compare the oral testimonies of the care-leavers with their respective documentary records.

Swedish governmental reports (SOUs) from 2006 through 2011 make up this study’s main source material, mainly the Inquiry into severe abuse and neglect (“Vanvårdsutredningen”) (SOU 2011:61) and of the Inquiry into Redress, (“Upprättelseutredningen”) (SOU 2011:9), as well as depictions of and comments on these reports in media and popular culture (e.g. Kanger 2014; Funke 2016). The Inquiry into Severe Abuse and Neglect was initiated in 2006, a direct effect of the Stolen Childhood TV documentary. The inquiry’s task was to collect testimonies from care-leavers and hence uncover the scope of the abuse and neglect. The Inquiry into Severe Abuse and Neglect produced two reports. Following the publication of this investigation’s results, the government initiated a second inquiry, the Inquiry into Redress, tasked to investigate the possibility of financial compensation for the victims of abuse and neglect. This study draws on these two reports not only as a collection of governmental facts and findings but also as objects of study in themselves. Besides the examples of abuse described, an analysis of the phrasing in the reports offers important insights into the implicit presumptions and postulates underlying the investigation. The material was analyzed using a hermeneutic method, where reading of the SOU:s alternated with historical and theoretical literature on the topic, such as e.g. Sköld et al. (2020, 2021), Jardine and Drage (2018), Sköld and Jensen (2015), Sköld et al. (2012), and Olick (2007), and as well as constant note-taking, writing, and re-writing. The selection of texts was made organically through reference chaining and suggestions from colleagues to whom I presented drafts of the article.

The TV documentary, Stolen Childhood, that kickstarted the entire Swedish redress process was made by journalist Thomas Kanger. In addition to the actual documentary, Kanger (2014) wrote a follow-up book after the redress was concluded. In addition to recounting the original story of neglect and abuse, Kanger discusses the low rate of granted compensations. Drawing on the Redress Board’s documentation, the original archival material, and interviews with care-leavers who applied for compensation, Kanger’s work provides important material for the present study, an excellent source of information on both the abuse committed and the aftermath of the redress and how it affected some of the care-leavers.

Theoretical framework

In his book The Politics of Regret, sociologist Jeffrey K. Olick (2007) explores the concepts of memory, reconciliation, and redress and develops a theory of how power gains support and legitimizes its current political rule by looking back to the past. He argues that rulers look back not to remember and build on a glorious past but to distance themselves from this past. One example of this is the redress processes, which forms what Olick calls “the politics of regret.” According to this perspective, the redress scheme can be a way for the government to gain credibility and distance itself from the all-encompassing social engineering instrument that it once was. Nevertheless, by compensating the victims of this instrument, the state inadvertently “grows,” stretching its reach further into the lives of its citizens. Olick’s theory also addresses the problems that emerge when societies in a globalized late-modern world try to unite around shared memories. When societal consensus is hard to achieve, sometimes the only thing to unite around is the denouncement of the actions of past leaders (Olick 2007, p 137).

Another concept underpinning this article is that of total archives, which emerged in the 1970s as a way of creating a coordinated national network of archives to benefit as many people as possible (Ghaddar 2021, p 76). The total archive, particularly as realized in Canada, is often described as a means of bridging the divide between records from the public and private sectors. The aim is to create archives that cover all of society—not only decision-making power institutions—to ensure that all aspects and levels of society are represented and made visible. Hence, total archives are commonly seen as a project of democratization (e.g. Millar 1998). Recently, however, this view has been challenged, both inside and outside the field of archival science (e.g. Ghaddar 2021). Since advocates of total archives want to bring together records and archives from both the public sector and civil society, they need coordination that in turn presupposes the extended reach of the politic sphere. Hence, one could say that the total archive is about incorporating civil society into the public sphere. One example of this view is offered by historians and philosophers Boris Jardine and Matthew Drage, who read the total archive as something both threatening and impossible. They argue that one cannot embrace and enclose the totality of society in an archive, or even in “archives,” and that the impulse to attempt it stems from a desire for total order and control that will ultimately lead to oppression (Jardine and Drage 2018). These clashing views of the total archive are significant for this paper. The divide between different facets of society in the Redress Board’s assessments led to care-leavers being denied compensation on grounds that it was not the state as such that put them in care, but rather different parts of civil society. This sectioning puts strain on the questions of what reach the state has, and should have, into the lives of its citizens, and what responsibility it has towards children growing up within it.

Regardless of objections such as those by Jardine and Drage, the aim of the total archive is benevolent. In his article “Counterweight: Helen Samuels, archival decolonization, and social licence” (2021), Canadian archivist Greg Bak draws on the work of Helen Samuels (1992) and investigates how her concepts of documentation strategy and functional analysis might be useful in the decolonization of Canadian archives. Can records, he asks, created with bad intentions really do good, even after the creator of these records (the colonial state) has made amends? He answers Hans Booms’ (1987) claim that it is society itself, and no one else, that is qualified to give legitimacy to archival appraisal: “But what happens if society itself is unjust, and its values sanction gross violations of human, civil, or Indigenous rights? What if the functions of an institution or government include genocide? What is the archival imperative then?” (Bak 2021, p 433). Hence, it is Western archival theory’s functionalism that is the reason for this theoretical lock-in. A total archive cannot work against the state from which it emerges. Nevertheless, Bak sees potential in the production of oral testimonies and the collection of non-official documents as counterweights against the state’s official records. The total archive may be totalitarian in its full realization, but the quest for a fuller picture using “counterweights on counterweights” might still in practice give richer, fairer, and more diverse archives, Bak concludes.

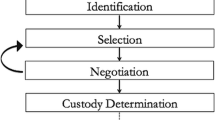

The Swedish process

In 2006, the Swedish Inquiry into Severe Neglect and Abuse was commissioned to collect testimonies from people who had suffered from neglect and abuse in children’s homes and foster homes (Dir. 2006:75). Although the Inquiry’s directive was to map and measure occurrences of abuse, the terms of reference acknowledged that written documentation of such abuse was very scarce. The Inquiry’s first mission, therefore, was to collect and document testimonies from care-leavers (Arvidsson 2016, p 120), thus creating its own sources as the basis for a reparation historiography. After two prolongations due to the large number of people wanting to testify, the Inquiry handed over its final report in 2011 (SOU 2011:61).

One purpose of the Inquiry was to allow victims to process their experiences of abuse. The opportunity to tell their stories was described as part of the reparation, even if the information acquired during the interviews also served as the basis for the factual report of the Inquiry (Dir. 2006:75). The Commission acknowledged the risk of re-traumatization caused by the recollection of hurtful memories many years later, and chose to handle this risk by offering psychological support in connection with the interviews. Hence, narrativization was used as a tool both for the state to investigate what had occurred and for the claimants to process the events emotionally.

When a decision has been made to compensate a victim financially, the money can be distributed in different ways. In Sweden, the redress scheme adopted the form of ex gratia payments (Prop. 2011/12:160). These payments, in contrast with criminal or civil justice processes but in line with restorative redress, focus on the suffering of the victim, rather than the liability of the wrongdoer (Law Commission of Canada 2000). The choice of type of compensation affects, or, rather, is affected by, the perception of liability. The Swedish Inquiry asserted that although the state could not be held legally responsible for the violations of human rights that occurred at its institutions, it nevertheless carried a heavy moral responsibility (SOU 2011:9, 104). As we shall see, however, this statement had little actual impact on individual cases.

As Sköld et al. (2021) point out, the Swedish process differed in a number of significant ways from other international redress schemes. First, the Swedish redress included different types of abuse and neglect in the same process; it did not focus on one specific type of abuse at a time, as Ireland did with sexual abuse, for example. Second, Sweden did not focus on abuse at specific types of institutions but rather on violations committed at many different institutions, including children’s homes, reformatories, and even foster homes. Third, the compensation in Sweden was not graded; the same amount of 250,000 SEK (roughly 25,000 Euro) was paid out to everyone whose claims the Board considered legitimate, regardless of the type and severity of the abuse. Last, Swedish claimants did not have the right to appeal against the Redress Board’s decisions, nor were they entitled to legal counsel.

To be considered for financial compensation in Sweden, the claimant must have been placed in care by their municipality’s welfare board and able to prove this through archival records. The demand on the claimant was to produce records of the municipality’s decision of placement. Whatever neglect or abuse that did or did not occur within this placement was then to be investigated based on the claimant’s oral statement. No actual written proof of abuse was required, but the claims needed to be supported, not contradicted, by the records (SOU 2011:9, 167). Cases, for example, in which a doctor or a local health authority decided on the placement were not considered for redress because they did not qualify under the Redress Act’s stipulations for compensation, as phrased in legal terms. The Act’s criteria for compensation eligibility were, in fact, quite strict, requiring that the claimant’s placement was motivated through one of four different acts: (1) The Act Concerning Reprobate and Morally Neglected Children (Lag angående vanartade och i sedligt avseende försummade barn (SOU 1902:67)); (2) The Act For the Relief of the Poor (Lag om fattigvården (SFS 1918:422)); (3) The Act of the care of children (Barnavårdslagen (SFS 1924:361)); or (4) The Act of society’s care of children and young people (Lag om samhällets vård av barn och ungdom (SFS 1960:97)). The Redress Board did not always demand that the original decision be produced; in some cases, other document mentioning the decision was sufficient. However, the reasons for placement had to be one of those stated in the Redress Act—otherwise the case was dismissed (Sköld and Jensen 2015, 169). The Inquiry into Severe Abuse and Neglect also proposed that so called private placements be covered by the Redress Act, since, in many cases, the social service authorities were responsible for auditing them too (SOU 2011:61, 79). This suggestion did not meet with the legislators’ approval, however, and the Redress Act ended up stating the narrower criteria.

Settler states such as Canada and Australia have aimed their redress processes at wrongdoings committed against communities of Indigenous people within its borders, especially children within these communities. Sweden, too, is to some extent a settler state. The Sami population in the Swedish part of Sápmi have been deprived of large parts of their land and culture. In 1913, the Swedish state opened schools for Sami children, so-called nomad schools, with the express purpose of assimilating these children, forbidden from speaking their native language, into Swedish society. Many have testified to the harsh and humiliating conditions within these schools, where physical and emotional abuse was frequent (e.g. Huuva and Blind 2015). When the Swedish Inquiry into Redress was initiated, many Sami people hoped it would also encompass the oppression and abuse of Sami children. This did not happen, however, because the Commission for the Inquiry was limited to those children placed in care on the basis of the four specific Acts listed above and none of these were used to justify sending Sami children to nomad schools.

Neither did the inquiry include the so-called Finnish War Children, children who were sent from Finland to Sweden during the Second World War. Approximately 70,000 children came to stay with Swedish families, and about 7,000 of them remained in Sweden after the war. Many of these children, now ageing and decreasing in numbers, struggled to be included in the redress process but did not succeed (Arvidsson 2016, p 172).

In 1998, the Swedish Minister for Agriculture made an official apology to the Sami people for the way the state treated them. However, this apology was not followed by any action or change of politics until 2020, when the Swedish Parliament gave 1.2 million Swedish crowns (120,000 Euros) to the Sami Parliament to initiate a Truth and Reconciliation Process (Quinn 2020). Unlike the Sami, whose suffering has finally been acknowledged by the Swedish government, in words if not in compensation, the Finnish War Children continue to be denied any form of reparation, verbal or otherwise. Because this article focuses on people eligible for compensation, neither of these groups are included in this study. But the fact that both the Sami and the Finnish War Children were excluded from the redress scheme is significant and worthy of further scholarly attention.

The records

Records from social care are sometimes the only remains, or “evidence,” of a person’s childhood. But recordkeeping is often both inconsistent and fragmentary; case files turn out to be thin and anonymous, frequently exhibiting gaps in their timelines. Obviously, one needs to be aware that where records do occur, their purpose is to motivate or document administrative and legal procedures, not to document the life of a child (Billquist and Johnsson 2007). This makes it hard to follow a child retrospectively through his or her records and create a narrative out of them. Indeed, it is problematic to even check a narrative from a spoken testimony for facts (Sköld and Jensen 2015). In Sweden, moreover, the responsibility for auditing the care of children has often shifted between different municipalities and county administrative boards over the years. This is one reason why the search for records can sometimes be complicated and involve several different archival institutions.

Since 1862, Swedish municipalities, county councils, and regions have been governed by legislation (SFS 1991:900, the Municipalities Act) that gives them strong self-governance (Smedberg 2012, p 242). This independence also reflected in the archives. Not only are municipalities and county councils independent organizational authorities, but the Act on Archives (SFS 1990:782) also states that these local authorities are responsible for auditing their own archives. Hence, local archives are not governed by the National Archives but by the boards of each municipality and county council. These boards commonly have little to no knowledge of recordkeeping or archival matters; indeed, their primary task is to allocate funding to the archival institutions. Thus, in practice, it is the archival institutions themselves who make decisions regarding their operations. The municipal and regional archives can follow the recommendations and guidelines published by the National Archive, but they do not have to. This self-determination has led to great diversity in the archival practices throughout Sweden, which in turn has given great variation in what kind of records the Inquiry into Severe Neglect and Abuse could expect to find (SOU 2011:9, 166).

Unlike Canada, Sweden has never based its archival system on the idea of the total archive. The Swedish archives have traditionally been organized strictly on provenance, keeping each archive separate from each other and clearly tied to its organizational origin. This fact likely contributed to the partitioning and fragmentation of the different archives relevant for the redress investigations.

When Sköld et al. (2012) carried out a comparative study on claimants’ oral statements and documentary records, they found that some of the documents required for their research were lost due to improper disposal and/or unclear disposal schedules. They additionally discovered that there was little uniformity in which records the different archives had chosen to preserve (Sköld et al. 2012, pp 19f). Lack of documentation was sometimes also due to conscious decisions taken by social care workers. In many of the children’s case files there was correspondence from one social worker to another implying that the conditions within the placement were not ideal, but that the issue was too sensitive to discuss by letter and would instead be brought up either at their next meeting or in a phone call (Sköld et al. 2012, p 23). Because these issues were never written down, what they actually were will never be known. To believe certain information too sensitive to write about, however, is not unique to social workers. In 1963, Sweden passed a law (SFS 1963:341) that demanded medical doctors keep journals of all their patients, a practice that previously had been optional. The Swedish Association of Provincial Physicians protested against this, claiming that the information contained in these journals would be far too critical to store and was better off as silent knowledge in the individual physician’s mind (Wendel 2019, p 23). The passing of the bill, despite these objections, might be seen as a consequence of the increasing democratization of society during the second half of the twentieth century. It also mirrors the move towards putting the interests of patients over the authority of physicians. Nevertheless, the doctors protesting against the changes in documenting routines were not arguing for continued power over their patients. Rather, they pressed for the “soft” aspect of doctor-patient relationships and did not want to acknowledge their own power over patients at all. These Swedish physicians did not want to put information about their patients into writing because they wanted to protect their patients. Doing so, however, meant withholding information that ultimately might protect these same patients’ rights.

The relations between individuals and public institutions are seldom reciprocal; the individual is usually dependent on the official body. This power imbalance can motivate ideas on appraisal in two different directions. One approach is that the documentation of these unequal relations should be retained to document and “prove” the exercise of power. The other approach views documentation not primarily as proof of oppression but as a representation or continuation of it. According to this second view, then, records ought not to be retained since they represent and reproduce derogatory views on the affected individuals. In a total archive, however, or with the social functionalism of Bak and Samuels, oppressive records should be retained and weighed up with other types of documentation that tell other narratives from the perspective of the oppressed.

From a practical perspective, the tendency to protect others (and ourselves) by leaving no trace leads to thin and insipid files and complicates care-leavers’ search for answers about their past. However, the view of such files as precisely thin and insipid presupposes that the purpose of these records was to provide information to care-leavers. It was not. As social scientist Viviane Frings-Hessami points out, historical records created by child welfare agencies “were compiled for the agencies’ own use, not to meet the needs of the children or their adult selves.” (Frings-Hessami 2018, p 158). In a Swedish context, this is certainly true. The Social Services Act (SFS 2001:453), for instance, says very little about documentation in general and nothing at all about documentation as a means for care-leavers to gain information about their past. The records are byproducts of social and administrative work, created to document what was necessary for social workers and childcare agency civil servants to know in order to carry out their profession. As such, the records functioned very well, regardless of what we might think of them today. The records were never meant to serve as a means for the children in question to research their personal history, let alone to enable a redress process against the Swedish state.

Childhood narratives

During their years in care, Swedish care-leavers were often moved between various institutions and foster homes. The Redress Board tested the requirements for entitlement to compensation against a person’s every placement individually. Hence, instead of viewing the years in care as a single, cohesive narrative, the Board’s assessments fragmented the claimants’ narratives. One example of this fragmentation is a woman who had been placed in the same foster family for over ten years, where she suffered from neglect and harsh treatment. However, the most severe abuse that she was subjected to, when she was recurrently raped by a relative of the foster parents, did not take place until after 1980. Since the Redress Act did not allow compensation for abuse that took place outside of the 1920–1980 time frame, the Board felt forced to deny the woman compensation. She did suffer from some abuse before 1980 but none deemed severe enough to induce the compensatory sum of money (Sköld et al. 2020). Instead of considering her time in placement in its entirety, as a cohesive experience, the Board sundered her childhood into discrete events that did not form a whole.

This example shows how the myopic reading of the Redress Board’s instructions, combined with the focus on individual placements and restricted by the narrow time frame, led to fewer events being judged as severe enough for compensation. It also contradicted the legislators’ intention. The aim was for the state to compensate wrongdoings against individuals, regardless of the type of institution in which the abuse had taken place. Instead, the responsibility was again divided between different institutions and individuals, and the Board failed to make a comprehensive assessment (Sköld et al. 2020).

This fragmentation mirrors that of the Swedish archival system, where responsibility for the custody of records lies with the institutions that created them, as discussed earlier. The care and placement of children in Sweden was, and still is, a matter for the municipalities in which the children live. The self-governance of these municipalities is far-reaching and regulated by the Swedish Instrument of Government. This means, first, that the municipalities themselves get to decide what documentation of their activities is to be preserved and, second, that the municipal boards are responsible for auditing their own administration and recordkeeping, not the National Archive. This has led to a lack of coordination between the different municipalities’ archival practices, complicating the identification of and search for records (e.g. Sköld et al. 2012).

In her work on victimhood, Norwegian psychologist and criminologist Kersti Ericsson describes how abused and neglected children sometimes use silence as a strategy. Telling others about their experiences does not help; on the contrary, it often makes things worse, so children quickly learn to keep things to themselves (Ericsson 2015, pp 50f). This psychological phenomenon of keeping quiet is easy to envision–in fact, it borders on being common knowledge–but silence nevertheless became an obstacle for many Swedish care-leavers who applied for compensation. As a way of finding external support for the claims, the board orderly asked the claimants if they told anyone about the abuse at the time it occurred. A “no” answer did not necessarily mean a rejection, but it did complicate the assessment and increase the risk of the claim being denied. One example is that of a man who told the Redress Board about being regularly raped and humiliated by older boys at the children’s home where he lived. The Board asked if he ever told the staff about this, but he said that he did not. He was then denied compensation on the grounds that the institution where he lived could not be held responsible for the abuse, since they did not know about it (Kanger 2014, p 230). Here, one could instead hold the view that the children’s home (and by extension the state) provided an environment where this type of abuse among children could go on without notice. This view would also be closer to the intention behind the redress scheme, namely to compensate for wrongs suffered within society’s care, not caused by society (e.g. SOU 2011:9, p 58; Arvidsson 2016, p 149). The telling or not telling of the wrongs one was subjected to was brought up by the Inquiry of Redress, which stated that the fact that claimants had told other people about the abuse at the time it occurred might offer support for their stories (SOU 2011:9, p 15). However, the Inquiry of Redress did not say that the absence of such testimonies should be taken to obstruct the possibility of being granted compensation in the way that it actually did.

The redress

In 2011, the Swedish Deputy Minister for Social Affairs, Maria Larsson, stated that the task of politicians is to care for the future, not the past, and hence that economic compensation from the state to survivors of past institutional abuse would be both unjust and pointless (Arvidsson 2016, p 149). Even though Sweden eventually did launch a redress scheme with economic compensation, the view exemplified by Larsson calls for further dissection of the different positions held in matters of state redress and reconciliation processes. Political theorist Stephen Winter has pointed out that in cases of restorative redress (as in for example Sweden and Canada), the focus tends to be on the claimants as individuals in need of healing and comfort, not as holders of certain rights that have been violated (Winter 2014, pp 191f). This difference might be phrased as the application of different logics to the same empirical conditions. In the examples of Sweden and Canada, one might say that a logic of emotion (or compassion), has been applied to victims searching for redress for past violations. This logic of compassion places great importance on the life stories, narratives, and emotions of the claimants, a significance clearly demonstrated in the collection of oral testimonies and in the Redress Board’s assessment of these accounts. Such stories assist the Board’s ability to judge whether the violations have had a (sufficiently) detrimental impact on the claimants. It would have been equally possible though, to apply a logic focused more on legislation of the cases than on the stories of the claimants. According to this legislative logic, victims could be compensated for the mere fact that they had been taken into “care,” regardless of how much or little damage it had caused them as individuals. With a logic of compassion, as opposed to a more legalistic focus, also comes an unawareness of the state’s responsibility. In line with the Swedish physicians who protested against the duty to hold records on their patients and did not want to acknowledge their power in relation to these patients, the focus on the suffering of individuals averts attention away from the structural oppression exercised by the Swedish state against children from the lower classes and cultural minorities. At the same time, the Swedish redress process very much emerged out of the re-evaluation of the Swedish welfare state from the 1970s onwards. As mentioned earlier, the redress process worked as a politics of regret for Sweden, a way to distance itself from a dark and complicated past, one in which its own state institutions had great influence on and power over the lives of its citizens. The redress process was supposed to put an end to the paternalistic Swedish state of the twentieth century. Instead, it was perceived as a continuation of the same control and oppression that the care-leavers had experienced growing up. This paradox mirrors that of the total archive. In an attempt to become less paternalistic, the state archives incorporate records on and by its subjects into the official archival body. By doing so, however, the state archives actually consume the smaller individual ones.

Human rights focus on the rights of individuals. Indigenous communities often organize through families, clans, or land, which makes, for example, attempts to restore rights to stolen land, problematic (McKemmish et al. 2011, p 117). This problem has a parallel in the Swedish redress process when compared to the Norwegian. In Sweden, the investigations carried out by the Redress Board were individual, focused not on institutions but on private citizens’ experiences of abuse within the welfare system. Norway, by contrast, chose to focus on the institutions that figured in the testimonies, not on individual life stories, applying more of a legislative logic to the redress process than did Sweden. Nevertheless, the Norwegian focus on institutions did not imply that the redress in Norway ignored the care-leavers’ experiences. In the documentary that triggered the Swedish process, the former Norwegian Minister of Family Matters (familjeminister), Laila Davöj, said, “A wasted life is in itself a kind of documentation” (Stulen barndom 2005, my translation).Footnote 1 By stating this, she meant that there was no need for thorough investigations, no need to know what exactly was done to the claimants by whom and when. The mere fact that so many care-leavers’ lives had been marked by mental illness, unemployment, crime, and abuse provided evidence enough of the damage done to them by growing up in society’s “care.”

Both Sweden and Norway decided to base their inquiries on the UN Convention of the Rights of the Child (UNCRC) and hence to define abuse as anything that violated the rights stated within. Because the UNCRC was ratified by Sweden in 1990 and Norway in 1991, it did not apply to the years investigated in either country, but decisions were taken to adopt a universal human rights perspective in these matters. However, when the Swedish inquiry went on referral to the Council on Legislation (Lagrådet), the Council added that the Redress Board should take into consideration “general opinions of the time” (Arvidsson 2016, p 154). So, while Norway went on to assess claims using solely the UNCRC’s criteria, the Swedish redress board was instructed to historicize the testimonies and acknowledge abuse as severe only if it would have been considered as such when and where it occurred. Naturally, the demand that maltreatment must have been beyond what was considered normal at the time of the abuse decreased the chances for Swedish claimants to be granted compensation. It also belied the whole point of the redress: to compensate for past incidents of malpractice.

The outcome

As most people who have ever set foot in a physical archive can attest, public archives often lack the records requested by their users; in turn, the records within the archives often lack the information that one seeks. Thus, archives tend to be a disappointment to its users as well as to its creators. One cause of these failures is deemed to be inadequate funding and scarce resources (Sköld and Jensen 2015), but one could perhaps consider some additional explanations. Sköld and Jensen suggest a larger, contextual approach to the use of documentation in redress processes, one that focuses not on individual cases but on patterns of abuse at a national as well as an international level (Sköld and Jensen 2015, 171). The report of the Swedish Inquiry on Redress noted that offenses are seldom discrete, anomalous incidents that can be identified individually: “A violation is normally not an isolated event that can be judged independently. Reality does not let itself be defined that way.” (SOU 2011:9, p 143, my translation). The writers of the report obviously acknowledged the impossibility of constructing a coherent narrative out of fragmentized anecdotes and scattered documents. Nevertheless, the implementation of their results caused exactly this kind of fragmentation.

As Bak discusses (2021, p 426), the National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation (NCTR) in Canada brought together official state and church records from residential schools-the colonial archive-with recordings of oral testimonies from indigenous survivors. Both sources were used in writing the final report of the Canadian Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC), published in 2007 and then deposited in a new archive and research center located at the University of Manitoba. This seems a perfect example of the total archive in action. By combining the official documentation with a “counterweight” of individual testimonies, the NCTR wanted to create an archive that gives a fuller and more correct picture of Canada’s colonial past. In a similar way, the Swedish redress process created new records based on the testimonies of care-leavers, functioning as counterweight to the original, official narrative of the welfare state. However, even though the Inquiry of Redress suggested, in its final report, the production of an exhibition to make visible and disseminate these new narratives, the various records were returned to their respective original archives after the hearings were concluded. The documentation of the oral testimonies is stored alongside the rest of the Redress Boards records, not kept with the official documentation of child placements-a very provenance-based way of organizing archives. While the approach to re-archiving this material differed between Canada and Sweden, neither method prevented the perception that, in many cases, the very act of collecting oral testimonies was simply another violation on top of the original ones about which the claimants testified.

As Olick shows, a state’s apology to oppressed communities can be seen as having a contradictory effect–states are strengthened and allowed to appropriate the subjects of apology into the body of society. In Sweden, the justification of the state was even explicitly used as a reason for handing out economic compensation by the Inquiry of Redress (SOU 2011:9, p 107). However, the effect of the redress scheme was, to a large extent, the opposite of the intended. When the numbers of those granted compensations turned out to be startlingly low, the government came across as not only petty and mean but also unduly bureaucratic, bordering on autocratic (e.g. Funke 2013). In interviews, both the chair of the Redress Board, Göran Ewerlöf and the Minister of Justice, Morgan Johansson, have expressed regret over the low percentage of claimants granted compensation (Funke 2016). Ewerlöf also expressed frustration by the wording of the Redress Act, which, according to him, forced the Board to make such strict assessments. The legislators, he claimed, could not have fully anticipated the consequences of the law (Andersson 2015). In short, the care-leavers were not happy, the public was not happy, and not even the responsible politicians and officials seemed to be happy with the results of the Swedish process.

Conclusion

Abuse is, by its nature, secret and silent. When a society discovers past abuse, it must document those instances of abuse to prevent them from happening again (Law Commission of Canada 2000, p 75). This insight acknowledges a rather obvious point stated earlier in this paper, that abusers do not willingly leave traces of their own abuse in official documents. Hence, the question should not be how the existing archival records contributed to the redress process—we know that they often did not-but rather what kinds of records and archives was produced by the redress process and what we can learn for the future. What can be said about the records, though, is that they did play a role in the processes of redress, in Sweden and elsewhere—but a more complicated role than might have first been assumed. The scarcity of documentation of the neglect and abuse under investigation made it impossible to base the trials and assessments solely on written evidence. Instead, oral testimonies came to be the most important source of information for the Redress Board. The redress schemes have thus actualized and highlighted the harm that reliance on records can do in redress processes if, that is, we use the archives for purposes they were not designed for and expect them to answer questions phrased in ways they cannot answer. To the extent that the inquiries and assessments in the Swedish redress process did rely on archival documents, the documents contributed to the fragmentation of narratives.

In summary, and to reconnect with the questions posed at the beginning of this article, narratives played a crucial role in the Swedish redress process. The claimants were encouraged to produce narratives of their experiences by telling their stories to the Redress Board. Hence, they were invited to participate in the redress process according to the logic of compassion, focusing on their experiences as coherent narratives. However, these narratives were then dissected and torn apart when scrutinized by the logic of legislation.

As Sköld et al. show, Sweden’s high rate of rejections depended partly on the phrasing of the different criteria against which the claimants’ narratives were tested (Sköld et al. 2021, p 97). This paper argues that the construction of those narratives, based on the archival records that were at hand, was in many cases an impossible task. It was not possible to live up to the set criteria using only the material available. The attempt to base investigations and assessments on individual life stories as documented by public authorities proved futile—the archives simply did not hold the required information. Because the records were not produced to tell the life stories of children in care, it was impossible to base those kinds of narratives on them. As this article has argued, the Inquiry of Redress (SOU 2011:9, p 143) was well aware of this. However, that the inquiry did, in fact, rely on documentation and archival records indicates an implicit assumption that archives mirror reality in a rather uncomplicated way.

The Swedish government tried to use the redress process as a politics of regret, seeking to profit politically and distance itself from its predecessors and from the social engineering politics carried out during parts of the twentieth century. Unfortunately for everyone involved, the scheme backfired, leaving the politicians looking cheap and heartless, the claimants re-traumatized and angry, and Swedish society troubled and embarrassed.

From the myriad problems built into the redress process, and from the lack of coherence in Swedish archives, one might find it appealing to turn to the total archives for a solution. Archival and appraisal systems that take a collective grip on both the originators of the records and the archives themselves are, of course, attractive when disruption and the lack of clear, collective responsibility are the problems. When I started writing this article, I thought that using a different archival system in the future would safeguard Sweden against repeating the tragedy of its redress process—a system that could encompass all of society and not leave anything (or anyone) out in the cold: a total archive. However, during the course of this study my conviction gradually became diluted and replaced by a suspicion that the total archive is not the solution. On the contrary, it is the positivistic view of and belief in the archive as a total archive that is the problem.

There seems to be a built-in paradox in the total archive. Its aspirations of inclusion can become a golden cage for the people and experiences contained within, but it also gives the illusion of total inclusivity, leading to the dismissal of those lives that did not leave any official traces. One way forward, out of this paradox, seems to be a “human-centered recordkeeping,” (Shepherd et al. 2020), or a “rights-based recordkeeping infrastructure” (Evans et al. 2021), in which a central purpose of social service records is to actually document the lives of children in care, not merely the actions taken by society regarding them. Regarding historical records, on the other hand, this is obviously not an option. As this article has argued, the reasonable approach to archival records in redress processes is a profoundly skeptical one. As archivists, we naturally want to use what we have and know best—the archives—for good, enabling individuals wronged by the state to gain reparation. However, in certain cases, the most constructive approach might be to show why the archives, used this way, failed to produce what the redress process required. Instead of simply providing politicians with the records they request, archivists should challenge them to ask different questions.

Notes

This documentary is not available online. Recorded copies can be borrowed from the Swedish National Library, through their database, SMDB (Swedish Media Data Base).

References

Andersson M (2015) Allvarlig vanvård krävs för att få statlig ersättning. [Severe neglect necessary to receive state compensation]. Advokaten. Tidskrift För Sveriges Advokatsamfund 81 (7). https://www.advokaten.se/Tidningsnummer/2015/Nr-7-2015-argang-81/Allvarlig-vanvard-kravs-for-att-fa-statlig-ersattning-/. Accessed 27 Jan 2023

Arvidsson M (2016) Att ersätta det oersättliga: statlig gottgörelse för ofrivillig sterilisering och vanvård av omhändertagna barn. [To replace the irreplaceable: state redress for involuntary sterilization and neglect of children in care]. Örebro studies in history 18. Örebro: Örebro University

Bak G (2021) Counterweight: Helen Samuels, archival decolonization, and social license. Am Arch 84(1):420–444

Billquist L, Johnsson L (2007) Sociala akter som empiri: om möjligheter och svårigheter med att använda socialarbetares dokumentation i forskningssyfte. [Social case files as empirical material. Possibilities and difficulties in using documentation of social workers in research]. Socialvetenskaplig Tidskrift 1:3–19

Booms H (1987) Society and the formation of a documentary heritage: issues in the appraisal of archival sources. Archivaria 24:104

Ericsson K (2015) Victim capital and the language of money: the Norwegian process of inquiries and apologies. J Hist Child Youth 8(1):123–137. https://doi.org/10.1353/hcy.2015.0012

Evans J, Wilson J, McKemmish S, Lewis A, McGinniss D, Rolan G, Altham S (2021) Transformative justice: transdisciplinary collaborations for archival autonomy. J Arch and Records Ass 42(1):3–24

Frings-Hessami V (2018) Care leavers’ records: a case for a repurposed archive continuum model. Arch Manuscr 46(2):158–173

Funke M (2016) Missnöje efter utebliven upprättelse för barnhemsbarnen. [Discontent after missed redress for care-leavers]. Sveriges Radio P1. https://sverigesradio.se/artikel/6551487. Accessed 27 Jan 2023

Ghaddar J (2021) Total archives for land, law and sovereignty in settler Canada. Arch Sci 21(1):59–82

Golding F, Lewis A, McKemmish S, Rolan G, Thorpe K (2021) Rights in records: a charter of lifelong rights in childhood recordkeeping in out-of-home care for Australian and Indigenous Australian children and care leavers. Int J Human Rights 25(9):1625–1657

Huuva K, Blind E eds. (2015) “När jag var åtta år lämnade jag mitt hem och jag har ännu inte kommit tillbaka”: minnesbilder från samernas skoltid. [“When I was eight years old I left my home, and I am yet to return”: memories of Sami childrens’ schooling]. Stockholm: Verbum AB

Jardine B, Drage M (2018) The total archive: data, subjectivity, universality. J Hist Hum Sci 31(5):3–22

Kanger T (2014) Stulen barndom: vanvården på svenska barnhem: ett reportage. [Stolen childhood: abuse and neglect in Swedish children's homes]. Stockholm: Bonnier

Kommittédirektiv 2006:75 Utredning om dokumentation och stöd till enskilda som utsatts för övergrepp och vanvård inom den sociala barnavården. [Inquiry into documentation of and support to people who suffered from abuse and neglect in social child care]

Law Commission of Canada (2000) Restoring dignity. Responding to child abuse in Canadian institutions

McKemmish S, Iacovino L, Ketelaar E, Castan M, Russell L (2011) Resetting relationships: archives and Indigenous human rights in Australia. Arch Manuscr 39(1):107–144

Millar L (1998) Discharging our debt: the evolution of the total archives concept in English Canada. Archivaria 46:103–146

Olick J (2007) The politics of regret: on collective memory and historical responsibility. Routledge, New York

Proposition 2011/12:160 Ersättning av staten till personer som utsatts för övergrepp eller försummelser i samhällsvården. [State redress for people subjected to abuse or neglect in society's care]. https://www.regeringen.se/49bbd6/contentassets/b0d10f782f63417ba829d41a4b4e94f5/ersattning-av-staten-till-personer-som-utsatts-for-overgrepp-eller-forsummelser-i-samhallsvarden-prop.-201112160

Quinn E (2020) Sami in Sweden start work on structure of truth and reconciliation commission. The Barents Observer, June 17

Samuels H (1992) Varsity letters: documenting modern colleges and universities. Society of American Archivists; Scarecrow Press, Chicago, Metuchen, N.J

SFS 1918:422. Lag om fattigvården (SFS 1918:422) [The Act For the Relief of the Poor]

SFS 1924:361. Barnavårdslagen (SFS 1924:361) [The Act of the care of children]

SFS 1960:97. Lag om samhällets vård av barn och ungdom [The Act of society’s care of children and young people https://www.lagboken.se/Lagboken/start/socialratt/socialtjanstlag-2001453/d_2685241-sfs-1960_97 Accessed 02 July 2023

SFS 1963:341. Allmänna läkarinstruktionen [General instruction for physicians] https://www.riksdagen.se/sv/dokument-och-lagar/dokument/svensk-forfattningssamling/allmanna-lakarinstruktionen-1963341_sfs-1963-341/ Accessed 02 July 2023

SFS 1990:782. Arkivlag [The Act on Archives] https://www.riksdagen.se/sv/dokument-och-lagar/dokument/svensk-forfattningssamling/arkivlag-1990782_sfs-1990-782/ Accessed 02 July 2023

SFS 1991:900. Kommunallagen [The Municipalities Act] https://www.riksdagen.se/sv/dokument-och-lagar/dokument/svensk-forfattningssamling/kommunallag-1991900_sfs-1991-900/ Accessed 02 July 2023

SFS 2001:453. Socialtjänstlag [The Social Services Act] https://www.riksdagen.se/sv/dokument-och-lagar/dokument/svensk-forfattningssamling/socialtjanstlag-2001453_sfs-2001-453/ Accessed 02 July 2023

SFS 2012:663 Lag om ersättning på grund av övergrepp eller försummelser i samhällsvården av barn och unga i vissa fall. [Law 2012:663 on compensation for abuse or neglect of young people in social care in certain cases] https://rkrattsbaser.gov.se/sfst?bet=2012:663 Accessed 02 July 2023

Sköld J, Foberg E, Hedström J (2012) Conflicting or complementing narratives? interviewees’ stories compared to their documentary records in the Swedish commission to inquire into child abuse and neglect in institutions and foster homes. Arch Manuscr 40(1):15–28

Sköld J, Jensen Å (2015) Truth-seeking in oral testimonies and archives. In: Sköld J, Swain S (eds) Apologies and the legacy of abuse of children in care. Palgrave Macmillan, Basingstoke, pp 159–171

Sköld J, Sandin B, Schiratzki J (2020) Historical justice through redress schemes? The practice of interpreting the law and physical child abuse in Sweden. Scand J His 45(2):178–201

Sköld J, Sandin B, Schiratzki J (2021) När välfärdssamhället gör fel. De vanvårdade och upprättelsens gränser. [When the welfare state is wrong. Neglected children and the limits of redress]. Arbetarhistoria. 3–4(179–180): 93–101

Smedberg, S (2012) Sverige. [Sweden]. In: Jörwall L et al. (eds) Det globala minnet. Nedslag i den internationella arkivhistorien. [Global memory. Fragments of the international archival history]. Västerås, Riksarkivet, pp 231–60

SOU 2011:9. Barnen som samhället svek: åtgärder med anledning av övergrepp och allvarliga försummelser i samhällsvården : betänkande. [Children let down by society: actions on abuse and severe neglect in society’s care]. https://www.regeringen.se/rattsliga-dokument/statens-offentliga-utredningar/2011/02/sou-20119/ Accessed 02 July 2023

SOU 1902:67. Lag angående vanartade och i sedligt avseende försummade barn [The Act Concerning Reprobate and Morally Neglected Children]

SOU 2011:61. Vanvård i social barnavård under 1900-talet: slutrapport ; slutbetänkande. [Neglect in social childcare during the 20th century: final report]. https://www.regeringen.se/contentassets/e568dc8c155d4a599a4a9177e839b3f5/vanvard-i-social-barnavard---slutrapport-sou-201161 Accessed 01 July 2023

Stulen barndom (2005) [Stolen Childhood]. Sveriges Television

Trägårdh L (2021) Scaling up solidarity from the national to the global: Sweden as welfare state and moral superpower. In: Witoszek N, Midttun A (eds) Sustainable modernity. The Nordic model and beyond Routledge studies in sustainability. Routledge, London, pp 79–101

Wendel L (2019) När läkare blev skyldiga att föra patientjournal: en studie av introduktionen av 1963 års läkarinstruktion. [When doctors had to keep records: the implementation of the 1963 instruction for physicians]. Arkiv, Samhälle Och Forskning 3:6–42

Winter S (2014) Transitional justice in established democracies: a political theory. International political theory. Palgrave Macmillan, Basingstoke

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank all her colleagues at Uppsala University, both in the Department of ALM and in the Engaging Vulnerability research program, for their reading of and comments on early drafts of this text, and to the anonymous reviewers for their insightful comments and suggestions. Particular gratitude goes to Reine Rydén, Anyssa Neumann, and Mats Hyvönen for reading, commenting, and editing. Thank you also to the organizers of the Digital Archives, Big Data and Memory conference in Copenhagen for letting me present a version of this paper in August 2022. Thank you also to Greg Bak, Devon Mordell, and Nina Janz for their helpful comments and questions during and after the presentation in Copenhagen.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Uppsala University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

No competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Grönroos, I. Records of neglect: the significance of archives in redress processes. Arch Sci 23, 591–608 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10502-023-09421-x

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10502-023-09421-x