Abstract

Aquaponics is a food production system which connects recirculating aquaculture (fish) to hydroponics (plants) systems. Although aquaponics has the potential to improve soil conditions by reducing erosion and nutrient loss and has been shown to reduce food production related carbon emissions by up to 73%, few commercial aquaponics projects in the EU and UK have been successful. Key barriers to commercial success are insufficient initial investment, an uncertain and complex regulatory environment, and the lack of projects operating on a large scale able to demonstrate profitability. In this paper, we use the UK as a case study to discuss the legal and economic barriers to the success of commercial aquaponics in the EU. We also propose three policies: (1) making aquaponics eligible for the new system of Environmental Land Management grants; (2) making aquaponics eligible for organic certification; and (3) clarifying and streamlining the aquaponics licence application process. The UK’s departure from the EU presents a unique opportunity to review agricultural regulations and subsidies, which in turn could provide evidence that similar reforms are needed in the EU.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In 2018, the UK Government released a report attributing 10% of UK greenhouse emissions to agriculture and a further 28% to transport (Department for Business, Energy, and Industrial Strategy 2020). These pose notable challenges to a government which has committed to achieving net-zero carbon emissions (UK Government 2019). In addition, there are many other global resource challenges, including depletion of fish stocks (Sumaila and Tai 2020), degradation of soil (Scherr 1999), availability of land (Lambin and Meyfroidt 2011), pesticide-induced pollinator loss (Stanley et al. 2015), and nutrient loss in both agriculture and aquaculture systems, potentially causing eutrophication and environmental contamination (Chakraborty et al. 2017).

The UK Government recognised the environmental and economic problems with agriculture in their “Farming for the Future Policy Update”, which also provides a roadmap for agricultural policy post-Brexit (Department for Environment, Food, and Rural Affairs 2020). The policy update suggests approaches such as replacing farming subsidies with financial incentives for environmentally positive farming interventions, as well as grants to promote technological and innovative solutions aimed at improving existing farming techniques. However, one potential technological solution was missing—aquaponics.

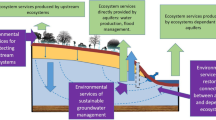

Recirculating Aquaculture Systems (RAS) are fish-rearing systems which recycle water and treat fish waste, which have benefits including saving water and improved fish yields (Goddek et al. 2015). Aquaponics systems are a subset of RAS which connect recirculating aquaculture to hydroponics, creating a sustainable, multi-trophic food production system in a closed or semi-closed loop (Fig. 1). Toxic ammonium from the fish waste is converted by bacteria present in the biofilter to nitrate taken up for plant growth.

Schematic of a basic coupled aquaponics system with a fish tank, b sedimenter or clarifier for solids separation, c biofilter for nitrification, d hydroponics unit (e.g. media bed or deep water culture) which also acts as a secondary biofilter, and e a sump with pump (Palm et al. 2019)

Aquaponics may be operated with a semi-closed system, without a dependence on soil (reducing soil erosion) and with nutrient recycling (removing nutrient loss). An aquaponics farm does not require arable land and so may be located in areas with arid conditions, poor soil, or in urban areas where it can reduce the emissions associated with long-distance supply chains. Aquaponics has been shown to have 72% lower carbon emissions per unit of production than the better-known and more established hydroponics (Monsees et al. 2019). Additionally, it potentially addresses sustainability issues by reducing pesticides, overfishing, and pollution without compromising on yield (comparable to that of hydroponic systems) (Graber and Junge 2009). The fish produced from these systems are regarded as the animal protein with the lowest carbon footprint (Flachowsky et al. 2017). The ethical benefits of aquaponics extend beyond sustainability. They can provide local healthy food and jobs in urban settings (Proksch et al. 2019) and support teaching of common curricular topics such as plant growth and nutrient cycles whilst creating nature experiences for children (Genello et al. 2015). They also can serve as social projects for disadvantaged groups or as community-building projects (Hart et al. 2013).

These characteristics mean there is potential to improve food security, reduce carbon emissions, benefit communities, and support governmental efforts to address several key environmental challenges to the agricultural sector. This potential was recognised by the European Parliament in 2015 when it named aquaponics as one of the “ten technologies which could change our lives” (Van Woensel et al. 2015). However, there are several regulatory and economic barriers to overcome before aquaponics can become a well-established sector.

The current UK regulatory landscape

The UK Government has acknowledged aquaponics as a technology with high potential (Freeman 2019) but has highlighted the considerable innovation required before it can compete commercially at any significant level (Black and Hughes 2017). Enterprise-level viability has been demonstrated in desk research, subject to site testing (such as water quality) (Telsnig 2014), but few commercial aquaponics facilities currently exist in the UK (Villarroel 2018). This is not surprising given the legal uncertainties.

There is no unified regulatory framework or specific legislation for aquaponic food production (COST Action FA1305 2018). Aquaponics is such a novel technology that a search of parliamentary debate transcripts via the Hansard database of UK parliamentary debates for the keyword “aquaponics” reveals zero resultsFootnote 1. Similarly, in Scotland, the only parliamentary mention is congratulations to a food festival which sourced fish from an aquaponics farm in 2011 (Scottish Parliament 2011). Unlike single-component RAS producing only fish, which have been deployed widely in Scotland (Ellis et al. 2016) and with mixed success in England and Wales (Hambrey and Evans 2016), the combination of fish and plant production in aquaponics systems means that the regulatory framework is segregated, so it is unclear which regulatory framework (aquaculture or conventional terrestrial agriculture) takes priority. The aquaculture side of the business in Europe is with few exceptions regulated by fisheries and aquaculture bodies (under the EU Common Fisheries Policy for member states) and the hydroponics side by agricultural bodies (under the EU Common Agricultural Policy).

The ease of obtaining planning permission for aquaponics projects in Europe is highly dependent on the nature and location of the farm. Planning, building, and water abstraction and discharge are governed at national and local levels within European Union member states. In the UK, small, rural farms including polytunnels may not require planning permission. At the other end of the scale, some countries such as Belgium apply agricultural zoning regulations, which may render a farm ineligible for permission in urban areas (Joly et al. 2015).

In the European Union, the Directorate General for Maritime and Fisheries (DG MARE) is responsible for EU policy on aquaculture, regulated under the Common Fisheries Policy (CFP). DG MARE does not provide specific regulations for the aquaponics industry. Other relevant EU policy areas for aquaculture include the EU Animal Welfare Strategy, Food and Nutrition Policy, and Environmental Policy. European aquaculture regulators operate at both local and national levels, including local authorities and fisheries, veterinary, and environmental bodies. In the UK, the Centre for Environment, Fisheries and Aquaculture Science (CEFAS), which incorporates the Fish Health Inspectorate (FHI), is responsible for authorising and inspecting aquaculture businesses and for regulating much of aquaculture operations including biosecurity, fish movements, imports, monitoring of fish health, and reporting of disease outbreaks. CEFAS provides a regulatory toolkit specifically for aquaponics businesses (Centre for Environment, Fisheries, and Aquaculture Science 2020) which greatly simplifies meeting of the regulatory requirements for the aquaculture side but is unable to give advice relating to hydroponic production, food safety, or construction of facilities.

The European Union Strategy for Protection and Welfare of Animals (2012–2015) (European Commission 2021) provides a framework for animal welfare in the EU; however, for fish species, it is limited in scope and lacks equivalent detail compared to regulations concerning handling and slaughter of other livestock. National level policies, including in the UK, are limited to non-binding advice on a few species commonly grown in conventional aquaculture. Aquaponics famers may choose to adopt certifications relevant to welfare to advertise their product; however, these may be difficult to achieve for aquaponics businesses. In the UK, for example, the options include the RSPCA Assured Welfare Standard (RSPCA 2020) (applicable to salmon and trout only, common conventionally farmed species, but rare in aquaponics), the Aquaculture Stewardship Council (ASC) standards, or organic certification (which precludes certification of products from recirculating aquaculture).

In the European Union, the hydroponic side of the business falls under the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) and is subject to fewer regulations than aquaculture. Aquaponics avoids one of the larger regulatory issues associated with crop production through an inability to employ pesticides. The main regulatory considerations of hydroponic production, therefore, involve planning permission and food safety.

The complexity of aquaponics regulation in comparison to either conventional aquaculture or horticulture may disincentivise companies or investors due to the perceived hurdles and additional administrative burden. However, in England, some advice is available (Centre for Environment, Fisheries, and Aquaculture Science 2020), and the design of aquaponics systems may render some of the regulatory concerns of conventional aquaculture or agriculture unnecessary.

Despite the challenges in navigating the disparate policies involved in aquaponic regulation, the sector may have some regulatory advantages over conventional production. Single-loop aquaponics systems by design are unable to use either medicated feed or pesticides and so avoid major regulatory obstacles encountered by producers that employ either. The closed nature of all aquaponic system designs may lessen the difficulties of obtaining planning permission compared to conventional flow-through aquaculture. Environmental impact assessments, water abstraction, and discharge licences may not be required, and farms may be located in areas with less competition for access to open water. EU Regulation No. 304/2011 allows farming of alien species (such as tilapia) in closed facilities such as aquaponics farms provided that biosecurity requirements are met. It is important to note, however, that differences in classification of aquaponic waste discharge (manure, treated or untreated water) by individual countries have implications for the design of aquaponics systems and the permissions required (including for alien species) and may create difficulties in attempting to duplicate a business model across national borders.

This is a complex landscape of local, national, and EU legislation, all lacking specific reference to aquaponics. This means that anyone wishing to establish an aquaponics business has to engage with multiple unlinked bodies with no crossover and little experience with dealing with the sector. The lack of clarity may discourage potential small businesses and investors, but given that aquaponics fits within a number of EU policy goals in relation to sustainable food production, waste reduction, and recycling, there are grounds for its inclusion in future policy revisions. The UK’s departure from the EU provides an opportunity to update and streamline national legislation by adding specific mentions of aquaponics to provide clarity and recognition for the sector.

Economic barriers to the success of aquaponics

Despite the environmental benefits and potential for high yields, the economic success of the aquaponics industry is mixed. Research from academic laboratories and case studies show multiple examples of economic viability and high profit potential of aquaponics facilities, with payback times estimated at around 7.5 years or less if produce can achieve organic food prices (Watten and Busch 1984; Bailey et al. 1997; Chaves et al. 1999; Love et al. 2015b; Bailey and Ferrarezi 2017; Quagrainie et al. 2018; Baganz et al. 2020).

Outside of a laboratory setting, however, the reality is different. Aquaponics is better established in the USA, but a survey of commercial aquaponics companies found that only 31% were profitable in the last 12 months although many of the remaining companies predicted they would achieve profitability in the next 12–36 months (Love et al. 2015a). Despite many hobbyists and researchers with aquaponics systems, in Europe, there are fewer cases of commercial success. A 2017 survey of the European sector by Turnšek et al. (2020) identified 60 participants involved in commercial aquaponics. Amongst these is an often-cited example of commercial aquaponics success, Bioaqua Farm, which is a medium-sized facility based in the UK. Bioaqua Farm produces rainbow trout and seasonal crops in outdoor ponds and polytunnels. The farm sells value-added produce, for example, smoked trout fillets and basil pesto, which allows for an increased profit margin. They also deliver courses to industry professionals and hobbyists and provide both catering and consultancy services, generating additional revenues. Products are marketed as “natural, ethical, and impeccable”, focussing on their environmental benefits and taste.

As economic feasibility is currently based on limited commercial data or derived from a research laboratory setting and/or models (that often fail to account for realistic expenses), it is difficult to comment with accuracy on the economics of aquaponics. The examples of profitable commercial facilities suggest potential but also tell a story of an industry which is still in its infancy. A survey of European commercial facilities highlights two major challenges: raising initial investment and administrative/legislative obstacles (e.g. environmental regulation) (Turnšek et al. 2020).

Failure to raise initial investment is particularly problematic for the industry because economic viability is dependent on size, with small facilities unable to compete effectively with large-scale projects (Bailey et al. 1997; Turnšek et al. 2019). Only when they reach scale can aquaponics projects prove their profitability, but they cannot reach scale without investment and cannot raise investment without demonstrating profitability (Turnšek et al. 2020).

Administrative obstacles hamper both the potential profitability, and the ease with which new facilities can start. European Union funding has been advertised for either aquaculture or hydroponics, and so it has been unclear what aspects of projects encompassing both (i.e. aquaponics) are eligible for, leading to a lack of applications and funding (Stinton 2016).

Another challenge is organic certification. In the EU, organic certification for plant production revolves around “nourishing the plants primarily through the soil ecosystem.” As a result, “hydroponic cultivation, where plants grow with their roots in an inert medium fed with soluble minerals and nutrients, should not be allowed” (European Commission 2008; Kledal et al. 2019). The United States Department of Agriculture does not prohibit hydroponic or aquaponic produce to be certified under the organic standard, and some growers in the USA have achieved organic certification for plants produced by aquaponics; however, this is not without challenge. Last year, the Center for Food Safety and a coalition of farmers launched an on-going legal challenge to prevent soil-less growers from using the term (Center for Food Safety 2019). The fish waste is a natural fertiliser, but current EU organic certification does not approve its use.

Fish produced by closed aquaponics systems in the EU also are unable to meet the standards for organic certification. European Commission Regulation No. 889/2008 prohibits the use of RAS for organic production, but the introduction to the amendment, Commission Regulation (EC) No. 710/2009, acknowledges that organic aquaculture is a new and evolving field. Despite concerns regarding energy consumption in RAS, the lower discharge of waste and greater biosecurity are advantages of such systems.

The profitability of aquaponics is significantly increased (even halving the payback time) if organic prices can be generated for produce (Quagrainie et al. 2018). Historically, there have been no plans to change certification requirements when discussion has arisen (COST Action FA1305 2018), although legislation is theoretically open for review when new evidence emerges (Kledal et al. 2019).

The challenges for commercial aquaponics projects unable to sell under an organic label are further compounded by a lack of public awareness. Fifty percent of European consumers are unaware of aquaponics and its associated environmental and ethical benefits, making it difficult to justify a higher price for their produce (Miličić et al. 2017). Without the seal of authenticity that an organic label would provide, a lack of consumer awareness hampers the ability to charge a premium price for aquaponics products on a mass scale. The Aquaculture Stewardship Council (ASC) does allow fish farmed in recirculating systems to be awarded the ASC label for responsibly farmed fish, one of the few sustainability or welfare certifications available to aquaponic producers. Consumer bias towards wild-caught over farmed and lower recognition of the aquaculture compared to the Marine Stewardship Council label (Alfnes et al. 2018) still means that fish produced by aquaponics experiences heavy market competition from fisheries products. Despite low consumer recognition for aquaponics and certifications outside of the organic label, consumers (in a range of countries) have been shown to accept aquaponics products when they are provided with more information on the technology and its environmental benefits (Eichhorn and Meixner 2020; Greenfeld et al. 2020). Once educated, most consumers appear likely to accept crops produced via aquaponics as organic (Gilmour et al. 2019). These are promising early findings, but the marketing of aquaponic products is addressed in very few studies (Greenfeld et al. 2019).

In addition to a lack of consumer knowledge, there is also a need for education within the aquaponics field (König et al. 2018). A survey of European aquaponics practitioners highlights knowledge gaps with regard to performing key tasks such as controlling plant nutrition, dealing with fish disease, and navigating the regulations for processing and selling fish (Villarroel et al. 2016). Furthermore, the expertise of aquaponics practitioners tends to be in either horticulture or aquaculture, not both, and the diffusion of information (particularly regarding business and regulatory knowledge) between practitioners is slow (König et al. 2018). The teaching of aquaponics at a university level is also scarce, though several organisations have attempted to address this issue. The COST (European Cooperation in Science and Technology) Action FA1305 aimed to facilitate education in aquaponics by bringing together cross-disciplinary working groups to network and train. The Action delivered seven training schools with lecture materials released onlineFootnote 2 along with a number of factsheets and open-source publications. The Aquaponics Association has a STEM working group and made integrating aquaponics into STEM education a focus of their 2020 conference “Cultivating the Future” (Aquaponics Association 2020). The recent programme Aqu@teach (Junge et al. 2020) was developed in part “as a response to the lack of adequately skilled personnel to design and operate aquaponic systems”. Insufficient opportunities and platforms for knowledge exchange and a limited skilled labour force are barriers to commercial aquaponics, but the adoption and proliferation of education programmes could go some way to addressing the latter.

Aquaponics facilities must compete against horticultural farms and facilities which are entitled to subsidies. For example, in the UK during 2018/2019, subsidies comprised more than 8% of the income for the average horticultural facility (Department for Environment, Food, and Rural Affairs 2019). This subsidy may enable horticulture to charge comparatively lower prices for food. Despite targets in both the CFP and CAP for improving the competitiveness and sustainability of aquaculture and agriculture (Massot 2020), there is no support for urban agriculture (Curry et al. 2015), and rural sites must cover at least five hectares to qualify for direct payment subsidies from the CAP (European Commission 2018). Aquaponics is newly emerging but must compete with horticulture which has well-established farming techniques, infrastructure, and support.

Similarly, the distribution of EU fishery funds strongly favours maritime and traditional freshwater aquaculture over aquaponics (König et al. 2018). A search of the European commission’s financial transparency system between 2010 and 2019 using the keyword “aquaponic” yields only 5 results, whereas there are 88 grants awarded to “maritime” and “aquaculture” projects in 2019 alone (European Commission 2020). European Maritime and Fisheries Fund (EMFF) grants awarded in the UK by the Marine Management Organisation from 2016 to 2020 (Marine Management Organisation 2020) show a similar pattern, with 27 grants awarded to projects with “maritime” and “aquaculture” in the operation name and only one with “aquaponics”. Despite the potential environmental benefits of aquaponics, both the aquaculture and horticulture components of businesses are at a funding disadvantage compared with their more conventional counterparts.

It is therefore unsurprising that some aquaponics projects fail, with research attributing being too early on the learning curve a key reason for RAS project failures (Hambrey and Evans 2016). Whilst there are limited data available specifically for aquaponics projects, because these projects involve similar concepts, it is likely that they will experience similar challenges. The lack of commercial projects means that development cannot be pushed forward. As we have seen with offshore wind in the renewable energy sector, innovative technologies can be driven by government support to the point where they become commercially competitive, becoming profitable without the need for subsidies (Jansen et al. 2020). Demonstration aquaponics projects such as that presented by Baganz et al. (2020) show the potential, but a 12-year payback period is too long. Without the learning process involved with real-world deployments, it will be impossible to ever reach the economies of scale needed for aquaponics to achieve financial sustainability (Goddek et al. 2015; Turnšek et al. 2019; Turnšek et al. 2020).

Policy proposals for the UK and EU

The commercial aquaponics sector in the EU may have been hampered by both the regulatory environment and the availability of subsidies for their primary competitors, horticultural farms and conventional aquaculture operations. The UK’s departure from the EU presents a unique opportunity to review agricultural regulations and subsidies, which in turn could serve as proof that reforms in the EU are required. This point was not lost on the UK Government. Following a consultation in 2018, the future direction was set out in the “Farming for the Future Policy Update” (Department for Environment, Food, and Rural Affairs 2020). On the basis that the UK Government considers the previous system—the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP)—“deeply flawed”, a new system of Environmental Land Management (ELM) was set out to contribute towards the 25-year environment plan and the 2050 net-zero carbon emissions target.

The ELM system moves away from the generic subsidies offered by the CAP and provides financial incentives for certain projects designed to improve the environment. These include using cover crops, planting wildflower margins, woodland planting, and creation or restoration of carbon-rich habitats such as peatlands, wetlands, and salt marshes. However, despite the focus on environmental benefit, the only incentive that could apply to aquaponics is funding for “locally targeted environmental outcomes”. This falls under the second of the ELM’s three-tier design whereby local people, land owners, and farmers are involved in the planning of projects in their local area. This tier is designed to provide support for regional needs as opposed to top-down control of large national or continental projects.

The UK is currently between agricultural oversight systems. Although the UK has formally left the EU, it is still in a transition state where EU systems continue to operate whilst new programmes are designed, developed, and launched within the UK. The ELM is not due to become operational until late 2024, with a pilot system beginning in late 2021 (Department for Environment, Food, and Rural Affairs 2020). During this interim 3-year period, the ELM will go through multiple iterations as plans are created, consulted on, tested, and adjusted.

This is a brief window for new ideas to be discussed, and the government is specifically asking for input and suggestions. In this section, we make three policy proposals to encourage the development of aquaponics to fit into the new ELM scheme and also to consider policy alternatives for the EU. The first of these is an adjustment to the UK ELM grants to ensure that aquaponics projects can apply for funding. The equivalent proposal for the EU is to amend the CFP and CAP such that aquaponics facilities qualify for the equivalent subsidies available to horticultural farms and that more fisheries subsidies are directed towards aquaponics projects. The second proposal is a review of organic certification guidelines so that aquaponic production methods become eligible for certification. The final proposal is a suggestion to clarify the regulatory landscape so that clear aquaponics licencing guidance can be offered and the application process streamlined.

For each proposal, we include a qualitative evaluation based on the Evaluation stage of the Rationale, Objectives, Appraisal, Monitoring, Evaluation and Feedback (ROAMEF) framework set out in HM Treasury’s Green (HM Treasury 2018) and Magenta (HM Treasury 2020) Books. The Rationale stage is assumed through the desire of the ELM to create “a productive, competitive farming sector – one that will support farmers to provide more home grown, healthy produce made to high environmental and animal welfare standards” (Department for Environment, Food, and Rural Affairs 2020). Whilst written from the perspective of the UK, the proposals address global issues for commercial aquaponics: funding opportunities, legislation, and the certification and marketing of produce. We hope that our recommendations can inform policy making in the UK, EU, and further afield.

Proposal 1: Make aquaponics eligible for ELM grants

One of the aims of the ELM is to improve the resilience of the supply chain (including the range of supply sources), a goal that could be facilitated by an emerging aquaponics industry producing food in new locations (including cities). This would shorten the supply chain, increase food production in the UK, and contribute to food security goals given that only 53% of food consumed in the UK is produced there (UK Government 2020).

The ELM seeks to improve environmental sustainability (and reduce emissions) by offering grants aimed at supporting innovative agricultural technologies and equipment. It specifies two main types of grants:

-

1.

Smaller grants: for improving performance, reducing emissions, and benefiting the environment

-

2.

Larger grants: targeted at higher-value or more complex investments, aiming to transform the performance of existing businesses

Whilst the proposed list of smaller grants does not include anything targeted towards aquaponics, the larger grants category is more flexible and could be open to aquaponics-related applications. The UK should use the opportunity of switching from the CAP to ELM to make it clear to investors and operators that aquaponics is a desired food production system that it sees developing from an emerging industry into an established and growing industry.

As discussed above, securing investment is the main barrier to the realisation of commercial aquaponics (Turnšek et al. 2020). Without investment potential, aquaponics projects look to grants but have found the eligibility criteria confusing (Hoevenaars et al. 2018). A Web of Science searchFootnote 3 for the number of peer-reviewed publications in “aquaponics” research shows an increase in publications every year, and it is likely that as research into technologies in this sector moves forward, yields will go up and costs come down.

As such, we suggest that aquaponics be listed as an eligible industry for funding in both the small and large grant categories (Table 1). The smaller grants would enable new facilities to open and sustain the losses that are often encountered in the first year of running a complex aquaponics system (Quagrainie et al. 2018). The larger grants will enable experienced operators to open large-scale facilities and develop new technologies and systems that will increase yields or reduce costs

The ELM guidance documentation should be expanded to include specific references to the value of aquaponics and to direct applicants to the funding available to the industry. The United States Environmental Protection Agency (2016) provides detailed business planning documentation covering marketing, operations, and financial strategy for aquaponics operators. This guidance could form a template for the UK and other countries looking to adopt similar measures.

The aquaponics industry should be included in the discussions that take place about the development of the ELM scheme. The ELM states that the UK Government wishes to discuss and consult with key stakeholders such as the National Federation of Young Farmers Clubs, National Farmers Union, Country Land and Business Association, and the National Trust. We suggest that this should also include The Aquaponics Association.

Changes to the ELM could address the lack of commercial investment in aquaponics facilities and the subsidisation of its primary competitors in the UK. Equivalent results could be achieved in the EU by making agricultural subsidies and grants available for aquaponics under the CAP and importantly by promoting this opportunity to farmers, investors, and legislators.

Proposal 2: Make aquaponics eligible for organic certification

“Organic” is usually defined as encompassing products that are environmentally and socially sustainable whilst avoiding the use of artificial fertilisers and pesticides (Department for Environment, Food, and Rural Affairs 2016). As discussed above, EU organic certification prohibits both soil-less and Recirculating Aquaculture Systems and therefore excludes both plant and fish production by aquaponics. This arbitrary distinction prevents aquaponics farmers from achieving the organic prices that would enable them to flourish. With the UK’s departure from the European Union, this is a clear opportunity for the UK to take the lead in creating a regulatory environment friendly to aquaponics. Mitigations to the organic standard could be made to include aquaponics whilst protecting the sustainability goals of the certification scheme. Soil-less plant production could be allowed provided that the media used was of natural origin, met the remainder of the requirements, and could be shown to develop and sustain a diverse ecosystem equivalent to that of organic soil. Fish production in recirculating aquaculture could be included with similar caveats to those employed by the RAS Module of the Aquaculture Stewardship Council (Aquaculture Stewardship Council 2020), namely, water abstraction and discharge, waste production, and energy use, along with existing welfare (such as stocking density) and sustainability conditions of the organic standard.

Our second proposal is to allow certification of aquaponic production in soil-less and Recirculating Aquaculture Systems as organic (Table 2). The UK has a growing demand for organic products (Nechaev et al. 2018; Zhao and Dou 2019), and the UK organic market is worth an estimated £2.45bn (The Soil Association 2020). Certification of aquaponics as organic could help the UK meet this increasing demand. A key benefit of aquaponics lies in its short supply chain, which could be located entirely within the UK. Existing conventional agriculture and horticulture farmers who sell their organic produce in the EU would still be able to apply for an EU organic label and would be unaffected by this modification of the UK certification criteria.

The introduction of this modification allowing hydroponics and aquaponics into the certification criteria could be accompanied by a marketing scheme with participation of the newly certified projects. This would boost consumer awareness, discussed above as a barrier to consumer purchasing, and would provide an incentive for the creation of new projects that would benefit from being first-to-market through the government marketing scheme.

Proposal 3: Clarify and streamline the aquaponics licence application process

As discussed above, setting up an aquaponics project requires the involvement of up to five government organisations, with much of the regulatory responsibility falling to the Fish Health Inspectorate, outlined in the regulatory toolkit developed by CEFAS as guidance for the aquaculture portion of an aquaponics business (Centre for Environment, Fisheries, and Aquaculture Science 2020). This uncertainty has hampered investment because of the legal risk.

Our third proposal is to simplify this process by the integration of the existing CEFAS regulatory toolkit into a centrally produced DEFRA toolkit (Table 3). Templates could be created for the common project scenarios to streamline this application process (e.g. small-scale projects tend not to require planning permission, water abstraction, and discharge licences). Scenario-specific templates to integrate rules, such as the use of aquaculture wastewater for crop production, or when fish stocks are imported and transported (regulated by the Fish Health Inspectorate and the Animal and Plant Health Agency, respectively), would simplify the application process for these small projects and could allow streamlining of the approvals procedure. Encouraging communication and overlap between advisory bodies to develop a cohesive regulatory framework for aquaponics would not only benefit new starters to the industry during the planning and application process, but also provide longer-term advantages for the sector. Recent surveys of aquaponics practitioners in Europe show a higher level of experience and confidence in aquaculture production than in horticulture (Villarroel et al. 2016; Turnšek et al. 2020). Integrating aquaculture guidance from CEFAS with agricultural guidance may encourage more individuals with horticultural or agricultural knowledge into the sector, improving and advancing the currently weaker side of the business. The increased oversight provided by a cohesive regulatory framework may have a risk reduction effect, for example, regarding food safety concerns in aquaponics. Guidance on, for example, nitrate accumulation (Pérez-Urrestarazu et al. 2019) and pathogen control (Weller et al. 2020) may reassure investors whilst providing robust standards to protect the industry against a potential crisis.

Investors want to see a route to enterprise profitability, which means operating on a large scale. Larger projects may require new applications for planning permission, water abstraction, etc. A clear route to converting the licencing from small to large scale is needed. If there are legal uncertainties when a project grows to a certain size, this could prevent projects from starting. Investors expect problems, but legal barriers are often the most challenging because they are outside the control of the project.

Reducing legal uncertainty requires showing a clear path for applicants (and their potential investors) to progress through permitting quickly, with clear criteria and guidance for compliance.

Conclusions

The EU’s CAP provides an important revenue stream for farmers but has failed to offer sufficient incentives to develop environmentally sustainable production methods. As tackling environmental damage from soil erosion to greenhouse gas emissions becomes a priority, new technologies are hampered in their development due to a lack of subsidies, complex legislation, and arbitrary restrictions on food production schemes which can help them gain mainstream adoption, such as requirements for organic certification.

Regardless of whether you consider Brexit to be a net positive or negative, the UK now has a unique opportunity to rectify the “deeply flawed” CAP by writing its own agricultural policy. The inflexible system of CAP subsidies has been reworked into targeted grants which now have the possibility to focus attention on environmental outcomes rather than automatic payments. This transition needs to be combined with streamlined legislation and clear guidance to encourage the development of innovative technologies. Aquaponics is one such technology that could benefit from this transition. Not only does it have the potential to prevent soil erosion and nutrient loss, it also can be deployed in urban environments to create local jobs growing healthy produce.

Greenfeld et al. (2019) surmise that larger systems, higher retail prices, and improved business plans lead to improved profitability for commercial aquaponics projects. These universal factors affect the profitability of commercial aquaponics worldwide. Our proposed policies would support realisation of the initial capital, business guidance, and regulatory environment to allow greater investment, in turn leading to larger, more efficient commercial systems that can achieve premium retail prices via their organic status.

The aquaponics industry in the USA is both larger and faster growing than its counterpart in the EU (Proksch et al. 2019), perhaps, in part accelerated by the eligibility there for organic certification of aquaponics products (National Organic Standards Board 2017) and the more readily available business advice and information for aquaponics facilities. This observation supports the case for implementation of our second proposal in the EU and would also benefit countries like Israel and Australia that prohibit organic certification of aquaponics produce (Joly et al. 2015; Miličić et al. 2017). However, the organic status of aquaponics in the USA is not guaranteed, and many members of the National Organic Standards Board (NOSB) who advise the National Organics Programme (NOP) wish to prohibit aquaponics products from organic certification (National Organic Standards Board 2017). Other countries following in these footsteps can expect similar challenges and resistance.

Beyond our proposed policies, which aim to create the initial environment for a successful aquaponics sector, there are other commercial barriers such as education and marketing. More education is required to improve systems operations and business plans and provide suitably skilled labour for a growing industry. Aquaponics is a suitable subject for teaching large parts of science curricula, and its inclusion in universities (with programmes such as Aqu@teach) would provide skilled labour for emerging markets. Embedding aquaponics into education systems also may increase consumer awareness and acceptance of aquaponics products. Investments in market research will help to understand the consumer and how best to sell aquaponics products (with or without the organic label) and strengthen retail prices. Globally, there is potential for a strong niche market if consumers are well informed, but product preferences vary between countries. The products also may need to be developed or better understood; research into the nutrient content and sustainability benefits of aquaponics could further enhance sales.

In this paper, we have suggested three areas on which the UK Government could focus as it develops the ELM over the coming months. The opportunities afforded by a move to the ELM highlight flaws with the EU systems and suggest areas where reform is needed for growth of aquaponics in both the EU and UK. However, the barriers addressed here are not unique to the UK and the EU; many countries could stimulate the sector by subsidising aquaponics and permitting organic registration of its products. Legislation is a big issue in the EU, and emerging markets may seek to streamline their processes early to facilitate growth of this industry.

The viability of laboratory-based aquaponics systems has already been proven, and successful commercial aquaponics systems already exist in the USA and Europe. In fact, the global aquaponics market is predicted to grow to US$871 million by the year 2022 (Business Wire 2017). The wind energy sector has shown how to use government support to push an innovative technology from high cost to high profit. If the right incentives are implemented, consumers are made aware of the benefits of aquaponics, and the licencing system is streamlined, the same can happen for aquaponics in the UK, Europe, and globally. Sustainability is the future of farming, and we hope to see policies that give aquaponics the green light.

Notes

Keyword: “aquaponics”, filtered for peer-reviewed literature only

Abbreviations

- ASC:

-

Aquaculture Stewardship Council

- CAP:

-

Common Agricultural Policy

- CFP:

-

Common Fisheries Policy

- DEFRA:

-

Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs

- DG MARE:

-

Directorate General for Maritime and Fisheries

- EMFF:

-

European Maritime and Fisheries Fund

- ELM:

-

Environmental Land Management

- FHI:

-

Fish Health Inspectorate

- NOSB:

-

National Organic Standards Board

- NOP:

-

National Organics Programme

- RAS:

-

Recirculating Aquaculture Systems

- ROAMEF:

-

Rationale, Objectives, Appraisal, Monitoring, Evaluation, and Feedback

- CEFAS:

-

UK Centre for Environment, Fisheries and Aquaculture

References

Alfnes F, Chen X, Rickertsen K (2018) Labeling farmed seafood: a review. Aquac Econ Manag 22:1–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/13657305.2017.1356398

Aquaculture Stewardship Council (2020). Recirculating aquaculture systems. https://www.asc-aqua.org/what-we-do/our-standards/new-standards-and-reviews/ras/. Accessed 23 Jan 2021

Aquaponics Association (2020). Cultivating the future. https://aquaponicsconference.org/. Accessed 23 Jan 2021

Baganz G, Baganz D, Staaks G, Monsees H, Kloas W (2020) Profitability of multi-loop aquaponics: year-long production data, economic scenarios and a comprehensive model case. Aquac Res 51:2711–2724. https://doi.org/10.1111/are.14610

Bailey D, Rakocy J, Cole W, Shultz K (1997) Economic analysis of a commercial-scale aquaponic system for the production of tilapia and lettuce. In: Fitzsimmons K (ed) Proceedings of the Fourth International Symposium on Tilapia in Aquaculture, Orlando, pp 603–612

Bailey DS, Ferrarezi RS (2017) Valuation of vegetable crops produced in the UVI commercial aquaponic system. Aquac Rep 7:77–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aqrep.2017.06.002

Black K, Hughes A (2017) Future of the sea: trends in aquaculture. Government Office for Science, UK. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/future-of-the-sea-trends-in-aquaculture. Accessed 22 Feb 2021

Business Wire (2017) Global aquaponics market report 2017: by component, equipment & product type - research and markets. https://www.businesswire.com/news/home/20170926005989/en/Global-Aquaponics-Market-Report-2017-By-Component-Equipment-Product-Type-Research-and-Markets. Accessed 23 Jan 2021

Center for Food Safety (2019) Center for food safety files legal action to prohibit hydroponics from organic. Center for Food Safety, Washington, DC https://www.centerforfoodsafety.org/press-releases/5501/center-for-food-safety-files-legal-action-to-prohibit-hydroponics-from-organic#:~:text=Washington%2C%20D.C.%20Today%2C%20Center%20for,operations%20from%20the%20Organic%20label.&text=Hydroponic%20systems%20cannot%20comply%20with,not%20use%20soil%20at%20all. Accessed 22 Feb 2021

Centre for Environment, Fisheries & Aquaculture Science (2020) Freshwater - aquaponics farm. CEFAS https://www.seafish.org/trade-and-regulation/regulation-in-aquaculture/aquaculture-regulatory-toolbox-for-england/. Accessed 22 Feb 2021

Chakraborty S, Tiwari PK, Sasmal SK, Misra AK, Chattopadhyay J (2017) Effects of fertilizers used in agricultural fields on algal blooms. Eur Phys J Spec Top 226:2119–2133. https://doi.org/10.1140/epjst/e2017-70031-7

Chaves PA, Sutherland RM, Laird LM (1999) An economic and technical evaluation of integrating hydroponics in a recirculation fish production system. Aquac Econ Manag 3:83–91. https://doi.org/10.1080/13657309909380235

COST Action FA1305 (2018) COST Action FA1305 Final Achievement Report. FA1305: The EU Aquaponics Hub: Realising Sustainable Integrated Fish and Vegetable Production for the EU. COST Association AISBL, Brussels https://www.cost.eu/actions/FA1305/#tabs|Name:overview. Accessed 22 Feb 2021

Curry NR, Reed M, Keech D, Maye D, Kirwan J (2015) Urban agriculture and the policies of the European Union: the need for renewal. Span J Rural Dev 5:91–106. https://doi.org/10.5261/2014.ESP1.08

Daniel N (2018) A review on replacing fish meal in aqua feeds using plant protein sources. Int J Fish Aquat Stud 6:164–179. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-60325-7

Department for Business, Energy & Industrial Strategy (2020) 2018 UK greenhouse gas emissions. Department for Business, Energy & Industrial Strategy. https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/final-uk-greenhouse-gas-emissions-national-statistics-1990-to-2018. Accessed 22 Feb 2021

Department for Environment, Food & Rural Affairs (2009) Safeguarding our soils - a strategy for England. GOV.UK. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/safeguarding-our-soils-a-strategy-for-england. Accessed 22 Feb 2021

Department for Environment, Food & Rural Affairs (2016) Organic farming: how to get certification and apply for funding. Department for Environment, Food & Rural Affairs. https://www.gov.uk/guidance/organic-farming-how-to-get-certification-and-apply-for-funding. Accessed 1 Aug 2020

Department for Environment, Food & Rural Affairs (2018) Approved UK organic control bodies. GOV.UK https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/organic-certification-list-of-uk-approved-organic-control-bodies/approved-uk-organic-control-bodies. Accessed 9 Aug 2020

Department for Environment, Food & Rural Affairs (2019) Farm business income by type of farm in England, 2018/19. Department for Environment, Food & Rural Affairs. https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/historic-farm-business-income. Accessed 22 Feb 2021

Department for Environment, Food & Rural Affairs (2020) The future for food, farming and the environment: policy statement (2020). Department for Environment, Food & Rural Affairs. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/the-future-for-food-farming-and-the-environment-policy-statement-2020. Accessed 22 Feb 2021

Diamant E, Waterhouse A (2010) Gardening and belonging: reflections on how social and therapeutic horticulture may facilitate health, wellbeing and inclusion. Br J Occup Ther 73:84–88. https://doi.org/10.4276/030802210X12658062793924

Eichhorn T, Meixner O (2020) Factors influencing the willingness to pay for aquaponic products in a developed food market: a structural equation modeling approach. Sustainability 12:3475. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12083475

Ellis T, Turnbull JF, Knowles TG, Lines JA, Auchterlonie NA (2016) Trends during development of Scottish salmon farming: an example of sustainable intensification? Aquaculture 458:82–99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aquaculture.2016.02.012

European Commission (2008) Commission Regulation (EC) No 889/2008 of 5 September 2008 laying down detailed rules for the implementation of Council Regulation (EC) No 834/2007 on organic production and labelling of organic products with regard to organic production, labelling and control. http://data.europa.eu/eli/reg/2008/889/oj. Accessed 22 Feb 2021

European Commission (2018) CAP Explained. Directorate-general for agriculture and rural development. https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/541f0184-759e-11e7-b2f2-01aa75ed71a1. Accessed 22 Feb 2021

European Commission (2020) Financial transparency system (FTS) - European Commission. https://ec.europa.eu/budget/fts/index_en.htm. Accessed 23 Jan 2021

European Commission (2021) European union strategy for the protection and welfare of animals 2012-2015. https://ec.europa.eu/food/sites/food/files/animals/docs/aw_eu_strategy_19012012_en.pdf. Accessed 30 Jan 2021

Flachowsky G, Meyer U, Südekum K-H (2017) Land use for edible protein of animal origin - a review. Anim Open Access J MDPI 7. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani7030025

Flynn D (2019) Organic industry is not giving hydroponic, aquaponic growers a warm embrace. Food Safety News. https://www.foodsafetynews.com/2019/02/organic-industry-is-not-giving-hydroponic-growers-a-warm-embrace/. Accessed 9 Aug 2020

Freeman B (2019) How are emerging technologies changing the way we farm our food? - Futures, foresight and horizon scanning. In: Futur. Foresight Horiz. Scanning https://foresightprojects.blog.gov.uk/2019/01/15/how-are-emerging-technologies-changing-the-way-we-farm-our-food/. Accessed 23 Jul 2020

Genello L, Fry JP, Frederick JA et al (2015) Fish in the classroom: a survey of the use of aquaponics in education. Eur J Health Biol Educ 4:9–20. https://doi.org/10.20897/lectito.201502

Gilmour DN, Bazzani C, Nayga RM, Snell HA (2019) Do consumers value hydroponics? Implications for organic certification. Agric Econ 50:707–721. https://doi.org/10.1111/agec.12519

Goddek S, Delaide B, Mankasingh U, Ragnarsdottir K, Jijakli H, Thorarinsdottir R (2015) Challenges of sustainable and commercial aquaponics. Sustainability 7:4199–4224. https://doi.org/10.3390/su7044199

Graber A, Junge R (2009) Aquaponic systems: nutrient recycling from fish wastewater by vegetable production. Desalination 246:147–156. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.desal.2008.03.048

Greenfeld A, Becker N, Bornman JF, dos Santos MJ, Angel D (2020) Consumer preferences for aquaponics: a comparative analysis of Australia and Israel. J Environ Manage 257:109979. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2019.109979

Greenfeld A, Becker N, McIlwain J, Fotedar R, Bornman JF (2019) Economically viable aquaponics? Identifying the gap between potential and current uncertainties. Rev Aquac 11:848–862. https://doi.org/10.1111/raq.12269

Hambrey J, Evans S (2016) Aquaculture in England, Wales and Northern Ireland: an analysis of the economic contribution and value of the major sub-sectors and the most important farmed species. Seafish Report SR694. https://www.seafish.org/document?id=4382b7aa-ffce-448b-850d-46a8f7959115. Accessed 22 Feb 2021

Hart ER, Webb JB, Danylchuk AJ (2013) Implementation of aquaponics in education: an assessment of challenges and colutions. Sci Educ Int 24:460–480

HM Treasury (2018) The Green Book. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/685903/The_Green_Book.pdf. Accessed 1 Aug 2020

HM Treasury (2020) Magenta Book. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/879438/HMT_Magenta_Book.pdf. Accessed 1 Aug 2020

Hoevenaars K, Junge R, Bardocz T, Leskovec M (2018) EU policies: new opportunities for aquaponics. Ecocycles 4:10–15. https://doi.org/10.19040/ecocycles.v4i1.87

Jansen M, Staffell I, Kitzing L, Quoilin S, Wiggelinkhuizen E, Bulder B, Riepin I, Müsgens F (2020) Offshore wind competitiveness in mature markets without subsidy. Nat Energy 5:1–9. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41560-020-0661-2

Joly A, Junge R, Bardocz T (2015) Aquaponics business in Europe: some legal obstacles and solutions. Ecocycles 1:3–5. https://doi.org/10.19040/ecocycles.v1i2.30

Junge R, Antenen N, Villarroel M, Griessler T, Ovca A, Milliken S (eds) (2020) Aquaponics textbook for higher education. Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3948179

Kledal PR, König B, Matulić D (2019) Aquaponics: the ugly duckling in organic regulation. In: Goddek S, Joyce A, Kotzen B, Burnell GM (eds) Aquaponics food production systems: combined aquaculture and hydroponic production technologies for the future. Springer International Publishing, Cham, pp 487–500. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-15943-6

König B, Janker J, Reinhardt T, Villarroel M, Junge R (2018) Analysis of aquaponics as an emerging technological innovation system. J Clean Prod 180:232–243. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.01.037

Lambin EF, Meyfroidt P (2011) Global land use change, economic globalization, and the looming land scarcity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 108:3465–3472. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1100480108

Love DC, Fry JP, Li X, Hill ES, Genello L, Semmens K, Thompson RE (2015a) Commercial aquaponics production and profitability: findings from an international survey. Aquaculture 435:67–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aquaculture.2014.09.023

Love DC, Uhl MS, Genello L (2015b) Energy and water use of a small-scale raft aquaponics system in Baltimore, Maryland, United States. Aquac Eng 68:19–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aquaeng.2015.07.003

Marine Management Organisation (2020) European Maritime and Fisheries Fund (EMFF): successful applicants. GOV.UK https://www.gov.uk/guidance/european-maritime-and-fisheries-fund-emff-successful-applicants. Accessed 23 Jan 2021

Massot A (2020) The common agricultural policy (CAP) and the Treaty. Fact Sheets on the European Union. https://www.europarl.europa.eu/ftu/pdf/en/FTU_3.2.1.pdf. Accessed 25 Jul 2020

Miličić V, Thorarinsdottir R, Santos MD, Hančič MT (2017) Commercial aquaponics approaching the European market: to consumers’ perceptions of aquaponics products in Europe. Water 9:80. https://doi.org/10.3390/w9020080

Monsees H, Suhl J, Paul M, Kloas W, Dannehl D, Würtz S (2019) Lettuce (Lactuca sativa, variety Salanova) production in decoupled aquaponic systems: same yield and similar quality as in conventional hydroponic systems but drastically reduced greenhouse gas emissions by saving inorganic fertilizer. PLoS ONE 14:e0218368. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0218368

National Organic Standards Board (2017) Crops subcommittee proposal - hydroponics and container-growing recommendations. National Organic Standards Board, Orlando https://www.ams.usda.gov/sites/default/files/media/CSHydroponicsContainersNOPFall2017.pdf. Accessed 22 Feb 2021

Nechaev V, Mikhailushkin P, Alieva A (2018) Trends in demand on the organic food market in the European countries. MATEC Web Conf 212:07008. https://doi.org/10.1051/matecconf/201821207008

Nelson R (2007) 10 Great examples of aquaponics in education. Aquaponics J 46:18–21 https://aquaponics.com/wp-content/uploads/articles/Ten-Great-Examples-of-Aquaponics-in-Education.pdf. Accessed 22 Feb 2021

Palm HW, Knaus U, Appelbaum S et al (2019) Coupled aquaponics systems. In: Goddek S, Joyce A, Kotzen B, Burnell GM (eds) Aquaponics food production systems: combined aquaculture and hydroponic production technologies for the future. Springer International Publishing, Cham, pp 163–199. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-15943-6

Pérez-Urrestarazu L, Lobillo-Eguíba J, Fernández-Cañero R, Fernández-Cabanás VM (2019) Food safety concerns in urban aquaponic production: nitrate contents in leafy vegetables. Urban For Urban Green 44:126431. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ufug.2019.126431

Proksch G, Ianchenko A, Kotzen B (2019) Aquaponics in the built environment. In: Goddek S, Joyce A, Kotzen B, Burnell GM (eds) Aquaponics food production systems: combined aquaculture and hydroponic production technologies for the future. Springer International Publishing, Cham, pp 523–558. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-15943-6

Quagrainie KK, Flores RMV, Kim H-J, McClain V (2018) Economic analysis of aquaponics and hydroponics production in the U.S. Midwest. J Appl Aquac 30:1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/10454438.2017.1414009

RSPCA (2020) Farm animal welfare. RSPCA https://www.rspcaassured.org.uk/farm-animal-welfare/. Accessed 30 Jan 2021

Scherr SJ (1999) Soil degradation: a threat to developing-country food security by 2020? International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI). https://www.ifpri.org/publication/soil-degradation. Accessed 22 Feb 2021

Scottish Parliament (2011) Business Bulletin No. 99/2011. Scottish Parliament. https://archive.parliament.scot/business/businessBulletin/2011.htm. Accessed 22 Feb 2021

Specht K, Siebert R, Hartmann I, Freisinger UB, Sawicka M, Werner A, Thomaier S, Henckel D, Walk H, Dierich A (2014) Urban agriculture of the future: an overview of sustainability aspects of food production in and on buildings. Agric Hum Values 31:33–51. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10460-013-9448-4

Stanley DA, Garratt MPD, Wickens JB, Wickens VJ, Potts SG, Raine NE (2015) Neonicotinoid pesticide exposure impairs crop pollination services provided by bumblebees. Nature 528:548–550. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature16167

Stinton N (2016) CEFAS and regulations for aquaponics health and water quality issues in aquaponics systems. CEFAS BAQUA Presentation. https://issuu.com/baquacic/docs/baqua_03.09.2016. Accessed 22 Feb 2021

Sumaila UR, Tai TC (2020) End overfishing and increase the resilience of the ocean to climate change. Front Mar Sci 7:523. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2020.00523

Telsnig JD (2014) The feasibility of aquaculture, aquaponics and a lobster hatchery in Amble. Northumberland Inshore Fisheries and Conservation Authority. https://www.nifca.gov.uk/download/feasibility-aquaculture-aquaponics-lobster-hatchery-amble/. Accessed 22 Feb 2021

The Soil Association (2020) The soil association organic market report. Soil Association. https://www.soilassociation.org/certification/market-research-and-data/download-the-organic-market-report/. Accessed 1 Aug 2020

Tran G, Heuzé V, Makkar HPS (2015) Insects in fish diets. Anim Front 5:37–44. https://doi.org/10.2527/af.2015-0018

Turnšek M, Joly A, Thorarinsdottir R, Junge R (2020) Challenges of commercial aquaponics in Europe: beyond the hype. Water 12:306. https://doi.org/10.3390/w12010306

Turnšek M, Morgenstern R, Schröter I et al (2019) Commercial aquaponics: a long road ahead. In: Goddek S, Joyce A, Kotzen B, Burnell GM (eds) Aquaponics Food Production Systems: Combined Aquaculture and Hydroponic Production Technologies for the Future. Springer International Publishing, Cham, pp 453–485. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-15943-6

UK Government (2019) UK becomes first major economy to pass net zero emissions law. GOV.UK https://www.gov.uk/government/news/uk-becomes-first-major-economy-to-pass-net-zero-emissions-law. Accessed 25 Jul 2020

UK Government (2020) Food Statistics in your pocket Summary. GOV.UK https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/food-statistics-pocketbook/food-statistics-in-your-pocket-summary. Accessed 1 Aug 2020

United States Environmental Protection Agency (2016) Aquaponics business plan user guide. United States Environmental Protection Agency https://www.epa.gov/land-revitalization/aquaponics-business-plan-user-guide. Accessed 22 Feb 2021

Van Woensel L, Archer G, Panades-Estruch L, et al. (2015) Ten technologies which could change our lives: potential impacts and policy implications : in-depth analysis. European Parliament Think Tank. https://www.europarl.europa.eu/thinktank/en/document.html?reference=EPRS_IDA(2017)598626. Accessed 22 Feb 2021

Villarroel (2018) Aquaponics map (COST FA1305). Google Maps. https://www.google.com/maps/d/u/0/viewer?ll=35.352940376586105%2C0.4574513507217137&z=4&mid=1bjUUbCtUfE_BCgaAf7AbmxyCpT0. Accessed 22 Feb 2021.

Villarroel M, Junge R, Komives T, König B, Plaza I, Bittsánszky A, Joly A (2016) Survey of aquaponics in Europe. Water 8:468. https://doi.org/10.3390/w8100468

Watten BJ, Busch RL (1984) Tropical production of tilapia (Sarotherodon aurea) and tomatoes (Lycopersicon esculentum) in a small-scale recirculating water system. Aquaculture 41:271–283. https://doi.org/10.1016/0044-8486(84)90290-4

Weller DL, Saylor L, Turkon P (2020) Total coliform and generic E. coli levels, and Salmonella presence in eight experimental aquaponics and hydroponics systems: a brief report highlighting exploratory data. Horticulturae 6:42. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae6030042

Zhao J, Dou X (2019) A study of British organic food market. 9th International Conference on Education and Social Science, Shenyang, China, 29-31 March 2019. https://webofproceedings.org/proceedings_series/proceeding/ICESS+2019.html#location. Accessed 22 Feb 2021

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed equally to the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics statement

This article does not contain any studies with animals performed by any of the authors.

Conflict of interest

Rosemary Crichton and Christopher Cammies have non-commercial relationships with Bioaqua Farm, an aquaponics company in the UK. Rosemary Crichton is Director of the not-for-profit Bristol Fish Project CIC. The authors declare that they have no further known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Additional information

Handling Editor: Gavin Burnell

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Cammies, C., Mytton, D. & Crichton, R. Exploring economic and legal barriers to commercial aquaponics in the EU through the lens of the UK and policy proposals to address them. Aquacult Int 29, 1245–1263 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10499-021-00690-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10499-021-00690-w