Abstract

The present work investigates the formation process and early stage evolution of turbulent swirling vortex rings, by using planar Particle Image Velocimetry (PIV) and Large Eddy Simulation (LES). Vortex rings are produced in a piston-nozzle arrangement with swirl generated by 3D-printed axial swirlers in experiments. Idealised solid-body rotation is applied in LES to evaluate the effect of nozzle exit velocity profile in experiments. The Reynolds number (Re) based on the nozzle diameter D and the slug velocity U0 in the nozzle is 20,000. The swirl number S generated ranges from 0 (zero-swirl vortex ring) and 1.1, covering the two critical swirl numbers previously identified in a swirling jet. Both PIV and LES results show that the formation number F decreases linearly as S increases, with the maximum F ≈ 2.6 at S = 0 (produced by the swirler with straight vanes) and minimum F = 1.9 at S = 1.1. The corresponding maximum attainable circulation in the nozzle axis parallel plane also diminishes with increasing S. Evolution of compact rings produced by a stroke ratio L/D = 1.5 reveals that circulation decay rate is largely proportional to S. The trajectory of the vortex core in the axial direction, hence the ring axial propagation velocity, decreases as S, while that in the radial direction and the radial propagation velocity, increase with S. An empirical scaling function is proposed to scale these variables.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Turbulent pulsatile injection (puff) [1] and continuous swirling injection (swirling jet) [2] are two ways of flow momentum delivery used in combustion applications to enhance fuel-oxidiser mixing. Individual pulsatile injection involves the formation of vortex-ring-like structure [3] with an isolated coherent bubble propagating downstream by its self-induced velocity while evolving and being dissipated [4]. If the pulse duration is over a particular time scale, the flow field is characterised by a starting jet behaviour with a significant wake left behind the bubble structure. For a swirling jet, when the swirling momentum exceeds a certain threshold, it is featured by a bluff-body wake-like recirculation zone at the jet exit and self-excited azimuthal vortex structures, which break down to processing helical vortex cores. These characteristics are determined by the relative swirling strength [5] and have been extensively applied in jet engine combustion processes. The combination of these two types of flow generates swirling puffs or swirling vortex rings. It is expected to exhibit features of both to some extent and hence further promote mixing enhancement [6]. Therefore, fundamental understanding of the primary non-reacting flow physics of the swirling vortex rings is desirable, which, however, is limited to the best of the authors’ knowledge.

From a fluid dynamic point of view, when pulsatile flow injection with zero swirl is from a momentum release through a nozzle or an orifice to the ambient, either driven by a pressure difference or a piston motion, a toroidal shaped vortex ring is formed at the nozzle exit by boundary layer roll-up from the inner surface of the nozzle or orifice [7]. Some irrotational material is also entrained from ambient according to Biot-Savart law [8, 9] to form an ellipsoidal vortex bubble. At small stroke ratios L/D ≪ 4, where L is the effective slug length and D the (equivalent) nozzle diameter, the bubble structure is of a compact and isolated type, with its propagation motion in the ambient flow similar to a moving ellipsoidal bluff body. Under the combined effect of vorticity decay and entrainment of ambient fluid material, the strength (or circulation) of the vortex ring diminishes and is eventually dissipated [4, 10]. As L/D increases, the vortex core and the bubble both grow by rolling up more boundary layer materials into the core and entraining more ambient fluids into the bubble, until a limit called ‘formation number’ (defined as the maximum stroke ratio with which a compact vortex ring can be formed) is reached. Beyond this limit, no more energy can be delivered to the ring structure and the excess boundary layer material is left in the wake [11], giving rise to a starting jet.

The ratio L/D determines the compactness of the ring structure and the mass transfer/scalar mixing (between the ring bubble and the ambient), which is rather insensitive to Reynolds number (Re) effect in a range [12]. For a compact structure (L/D < 4), the mass transport by vortex rings is directly relevant to the evolution of the ring circulation and the entrainment rate [8]. Gan and Nickels [13] conducted experiments at two Re based on circulation (ReΓ =Γ /ν ≈ 2 and 4 × 104, where ν was the kinematic viscosity of the working fluid) and found that the formation number hardly changed. The entrainment rate was well predicted by the similarity theory [4], which also well described the evolution of other important physical quantities, e.g. circulation and fluctuating velocity scales, even though the ring structure was often highly distorted [14]. For L/D ≫ 4, Ghaem-Maghami and Johari [15, 16] measured the velocity and the scalar concentration fields of puffs and demonstrated decreasing entrainment rate with increasing L/D. It thus suggests the optimal mixing to occur on structures produced by small L/D.

When swirl component is superimposed to the flow generated by L/D < 4, it becomes highly complex as demonstrated in a limited number of studies. Naitoh et al. [17] generated vortex rings at ReΓ = 1,600 and 2,300 by fluid injection from a physically rotating nozzle and investigated the influence of swirl on the behaviour of vortex rings. The swirl number, S, was controlled by adjusting the rotation rate of the nozzle and the maximum equivalent swirl number (3) achieved in their experiment was S = 1.5. They found that the amount of fluid discharged due to the so called ‘peeling off’ increased with S. Some scattered numerical studies [18,19,20] concentrated on the evolution of the three-dimensional vortex structures and the instability development mechanisms of the swirling vortex rings, where the swirl component was superimposed on the ‘already formed’ ring with ideal Gaussian core. Piston initialisation was also considered in [18], but the formation process was not investigated in a great detail. In numerical studies, idealised solid-body rotation type of swirl can easily be achieved. It will be shown in this work that swirl strength plays a critical role almost immediately as the ring is being formed. That is, above a threshold \(S\geqslant 0.41\) at our Re, vortex breakdown effect is observed within a very short time scale and the ring bubble characteristics renders the solid-body rotation at the nozzle exit physically not possible.

The vortex breakdown in a jet like flow (\(L/D\to \infty \)) has been studied extensively. When S increases and reaches a well-defined threshold which is independent of Re and D, vortex breakdown occurs [21, 22]. The existence of the self-excited processing vortex core in the form of co-winding or counter-winding helical/spiral vortices has been evidenced [5, 23,24,25,26]. In addition, the breakdown is accompanied by a self-inducted bluff-body wake-like central recirculation zone near the nozzle exit leading to swirl-stabalisation [27]. The experiments on reacting swirling flow also contribute significant knowledge to the effects of heat and flame on the characteristics of the breakdown [28, 29]. Passive control and active exciting modify strikingly the instability of the central recirculation zone and large-scale azimuthal modes which are influenced the fuel combustion [30,31,32]. In our experimental study, we will demonstrate that the breakdown is spontaneous upon ring initiation, hence also takes effect on rings of L/D ≪ 4.

The present experimental study focuses on the formation and the propagation properties of swirling vortex rings generated from a static axial swirler. The Re and L/D condition, combined with effect of swirler makes sure that the generated ring is fully turbulent [33]. The velocity fields in the cross-section plane near the nozzle exit and the longitudinal section through the centreline are measured using the planar particle image velocimetry (PIV). To explore the differences of the flow features induced by the initial inflow condition, large-eddy simulation (LES) with solid-body rotation enforced is also performed at the same S and Re conditions.

2 Experimental Setup

The experiment is performed in a glass water tank measuring 2,400 mm (length)×900 mm (width)×800 mm (depth), as shown in Fig. 1a–b. The flow is supplied from a pipe which is mounted to the centre of the end surface with an inner diameter D = 40 mm. The pipe extends into the tank for approximately 200 mm to eliminate end wall effects. The rings are generated by a piston driven by a stepper motor with a maximum stroke 600 mm used to produce the vortex rings. The piston speed is set at U0 = 500 mm/s with a constant acceleration and deceleration a = ± 25 m/s2, yielding a Reynolds number ReD = DU0/ν = 20,000.

Varying swirl strengths are created by a set of axial swirlers mounted near the exit of the pipe as shown in Fig. 1c. Each swirler has a hub diameter of 0.1D (which is minimum to maintain reasonable axisymmetry subjected to manufacture capability) and 12 vanes of maximum thickness 1 mm (to maintain rigidity) uniformly distributed in the azimuthal direction, resulting in a maximum blockage ratio of 18.3% in the nozzle cross-section plane. Each vane has an axial length of 0.5D and a trailing angle β at the half-radius location. The vane angle between the leading and trailing edges at the half-radius location βξ is designed semi-empirically according to

where ξ denotes the axial distance to the vane leading edge as shown in Fig. 1d. β is selected to be 0, 20, 30, 40, 50, 60 degree by trial and error to achieve the desired S. Note that instead of an open nozzle, β = 0o swirler with straight vanes is used to produce non-swirling flows, in order to facilitate direct comparison with other swirlers. The vane angles at other radial locations are set so that the intersections of the vanes and cross-section planes are always straight lines. Possible flow separation from the vane surface is not considered. A mixing section (nozzle mouth) with decreasing wall thickness is installed downstream of the swirler. Its length is set to be 0.125D to compromise the non-swirling fluid volume at the start of a slug (8% of the discharge volume) and the mixing of the flow behind the vanes to attenuate the vane effect. Also for this reason, the hub end surface is flush with the vanes at the leeward side, while a streamlined shape is made at the windward side to minimise inflow separation; see Fig. 1d. These components are 3D printed with a sufficiently smooth surface finish and attached together by threads to allow easy exchange.

The swirl number is defined as the ratio of the axial flux of swirling momentum to that of the axial momentum [27], in order to account for the non-solid-body rotation, i.e.

Here, the axial velocity at nozzle exit is selected as the piston velocity U0. U𝜃 is the (averaged) azimuthal velocity at the nozzle exit measured by PIV; see Section 4.1. R is the nozzle radius and r is the radial coordinate after the Cartesian coordinate (x, y, z) defined in Fig. 1a mapped to the cylindrical coordinate (x, r, 𝜃), viz \(r=\sqrt {y^{2}+z^{2}}\) and \(\theta =\arctan (z/y)\), with the origin at the nozzle centre on the swirler exit plane. Here \(\infty \) is used as the upper integration range in the swirling momentum term (the numerator) to count for the radial diffusion and entrainment effect. The constant 1.5 is employed to cast (2) equivalent to the one defined by Liang and Maxworthy [24], where the inflow fulfilled the solid-body rotation:

Here Ω denotes the rotation rate of the solid-body rotation. Definition of Eq. 3 is also used for the following LES simulation. S = 0 − 1.10 are achieved both in measurement and simulation in present study.

It must be emphasising that swirl can alternatively be generated by physically rotating the nozzle, as used by a number of researchers mentioned above [17, 24]. The advantage of this arrangement is that solid-body rotation can almost be achieved, but the disadvantage is the complexity of the rig set up hence the limitation in practical usage. In addition, due to the fluid viscous effect, it would be very difficult to isolate the rotating fluid inside the nozzle from the ambient at the nozzle exit and ensuring the latter remains undisturbed. While this effect perhaps is unimportant for a jet experiment, for small L/D in the current experiment, it would cause non-trivial contamination. Axial swirlers, used in jet engine combustion cambers, are much easier to implement. In such arrangement, the linear and swirl components can only be set on simultaneously and in a proportional way. The drawback is lacking of control. Use of tangential swirlers are also seen [34], which generally impose stronger swirl compared to the axial ones. However, it is also more difficult to implement. Use of 12 vanes is to achieve a satisfactory degree of homogeneity in the azimuthal direction while maintaining reasonable blockage ratio and manufacture difficulty. The turbulent boundary layer built on the surface of these vanes surface will also be rolled up to the ring volume. These additional vorticity will help homogenise the turbulence in the ring volume, enhance mixing and render it puff like.

The flow over the cross-sectional (y − z) plane at x ≈ 0.125D (5 mm) downstream the nozzle exit and on the longitudinal (x − z) plane at y = 0 are both measured using planar PIV as shown in Fig. 1a and b. The tank is seeded by 10-μ m silver-coated hollow glass spheres. Illumination was realised by a 532-nm Nd:YAG Laser with a lens system to produce a 4-mm-thick (to account for the higher axial momentum) and 1-mm-thick light sheets for the two measurement planes respectively. Two 12-bit CCD cameras with spatial resolution 1280 × 1024 pixels and maximum frequency of 4 image pairs per second are used as the imaging tool. The imaging system is synchronised with the piston motion. Multiple measurements with different time delays are conducted to ‘artificially’ increase the sample rate. The two cameras are placed side-by-side as shown in Fig. 1b to extend the field of view (FOV) while maintaining a good spatial resolution. PIV images are processed by Davis 7.0 with interrogation window size of 16 × 16 pixels and 50% overlap, yielding a measurement grid of about 1 mm × 1 mm spacing in both configuration.

3 Numerical Fundamentals

3.1 Governing equations

In the experiment, the flow in the y − z plane at the nozzle exit is not strictly axisymmetric due to the effect of the swirlers, nor is U𝜃 proportional to r as it would be in a solid-body rotation owing to the physical nature of the flow in our study. In order to assess the effect of the solid-body rotation, a complementary LES simulation is performed. The governing equations for the current problem are presented as

where ‘\(\sim \)’ denotes the filtered variables at the grid level, u is the instantaneous velocity field, and νsgs is the subgrid eddy viscosity when the Boussinesq eddy viscosity hypothesis is used. The fluid density is absorbed by pressure p.

The dynamic procedure proposed by Germano [35] and modified by Lilly [36] is used to determine the sub-grid eddy viscosity νsgs with the explicit filter imposed at the test level, as shown in the following equations:

Here, \(\hat {\varDelta }\) is the filter width at the test level, which is usually represented by twice the grid width Δ as \(\hat {\varDelta }=2\varDelta \). s is the strain-rate tensor. Because Cs varies drastically in space and time, local averaging is applied to both the numerator and denominator of Eq. 6 using the test filter to improve numerical stability. Hence, the sub-grid eddy viscosity is determined by

3.2 Computational setup

LES is performed at the same conditions of that in the experiment, i.e., S = 0,0.26,0.41, 0.60,0.87 and 1.1 (see Fig. 6b). The fluid issued from the nozzle with diameter D enters a cylindrical domain with diameter and length both of 28D (see Fig. 2a). The nozzle geometry is chosen to be the same as that in the experiment and its exit extends into the domain by 2D to eliminate the wall effects. A structured O-type base grid with 0.6 million cells is used here as shown in Fig. 2b, with a dynamic grid refinement scheme employed to increase the grid resolution where necessary. This is achieved by dividing each grid cell into eight smaller ones at each refinement level in regions specified based on the velocity gradients of the vortex ring and merging them back to a single one when the ring propagates away (Fig. 2c). This results in a maximum cell number of 5 million in total with 288 nodes in the azimuthal direction using two levels of grid refinement. Grid-convergence study using only one level of refinement at S = 1.1 shows that the grid resolution currently used is fine enough to capture the important features of the vortex ring propagation (see Fig. 13a).

The inflow boundary condition is critical to ensure the accuracy of LES simulation. In the present simulations, a mean field with uniformly distributed axial velocity U0 and linearly increased azimuthal velocity U𝜃 according to Eq. 3 is employed. Synthetic turbulence intensity of 10% is added to promote flow instabilities. The nozzle inner surface boundary layer is modelled by a gradually diminished axial velocity when r → R, equivalent to a boundary layer thickness ≈ 0.02D. The flow is discharged by an idealised top-hat velocity programme. The convective condition [37] is used on the outflow surface, with the convective velocity set to the instantaneous velocity in the previous iteration to mimic the natural outflow.

To aid entrainment of the ambient fluid into the vortex ring and improve the numerical stability, a small co-flow of Uco = 0.01U0 is imposed with zero turbulence intensity. Negative streamwise velocity at the outflow plane can then be eliminated [38, 39]. Furthermore, the no-slip and free-slip boundary conditions are applied at the nozzle wall and far field, respectively. Pressure is simply set to zero at the outflow plane and with zero gradients at all other boundaries. The simulation is performed using the open-source code OpenFOAM. To avoid the nonphysical fluctuations that result from the unbounded central differencing scheme in the simulation, a linear-upwind stabilised transport (LUST) scheme is used for the convection term of the momentum equation, which involves a hybrid central-upwind differencing with explicit gradient correction. The time step Δt is chosen to ensure that the maximum local CFL number is approximately 1.5.

4 Results and Discussion

4.1 Swirler properties

The velocity distribution in the vicinity of the nozzle exit is examined first by PIV measurements. We report the results in detail since they do not seem available in literature for similar designs. The results are benchmarked against jets at very long piston strokes. That is, S is quantified based on swirling jets, instead of short stroke rings. In total 50 realisations are sampled at this condition and measurements are taken at one time instant tU0/D = 6.5 in each realisation (piston starts at t = 0). It will be shown later that this time is large enough to exclude the leading ring entrainment effect.

The contours of the ensemble averaged azimuthal velocity U𝜃 and streamwise velocity Ux for β = 40o swirler are shown in Fig. 3a, b respectively. In (a), U𝜃 is normalised by a constant 〈U𝜃〉r, which is defined in Eq. 8. It is a demonstration of the azimuthal uniformity of U𝜃. Evidently, the effect of the swirler vanes can be seen at the measurement location. Toward nozzle wall, i.e. r > 0.4D, as U𝜃 intensity decreases, the degree of uniformity increase rapidly. In (b), the features of a broken down swirling jet is also evident by the two branches with a clear reverse flow region (Recirculation bubble 2) on the axis and the associated inner and outer shear layers. The formation of this recirculation bubble (also known as central recirculation zone) and its extent depend on the swirl strength [40]; the present studies (not shown in the figure) also show the formation of the large recirculation bubble at small swirling numbers due to the boundary effects of the vanes and hub. Recirculation bubble 1 is associated with the hub wake.

Ensemble averaged velocity distribution for β = 40o swirler, which has an intermediate angle among the tested swirlers. aU𝜃/〈U𝜃〉r measured at x = 0.125D; bUx/U0, where + ve filled contour levels are indicated by colourbar are denoted by the solid lines, while − ve contour lines [–0.05, 0.025, –0.0005] is denoted by the dashed lines. Only half of the measurement domain is shown attributing to symmetry

The mean profiles of Ux and U𝜃 in the y − z plane at x = 0.125D (as Fig. 3a) are displayed in Fig. 4a–b. Because of reasonable axisymmetry, U𝜃 is averaged in the 𝜃 direction and is presented in (b), where U𝜃 is normalised by a constant 〈U𝜃〉r defined as

As it can be seen at r = 0.6D, U𝜃 decreases to approximately zero.

Figure 4a presents the dependence of Ux on r. Both inner (r ≈ 0.15D) and outer (r ≈ 0.45) shear layers and the wake behind the hub (‘Recirculation bubble 1’ in Fig. 3b), reflected by Ux < 0, are clearly evident. Ux profiles from all the swirlers display similar shapes. As β increases, largest Ux moves toward smaller r. This effect weakens the outer shear layer, strengthens the inner one and shrinks the wake radius behind the hub. The trend appears monotonic until β = 50o, for the profile reflects a clear change at β = 60o.

Figure 4b examines the variation of U𝜃 and 〈U𝜃〉r. 〈U𝜃〉r exhibits almost linear trend with respect to the vane angle except β = 60o. The normalised U𝜃 profiles for β = 20o to 60o collapse very well. The step-like shape in \(0.07\lesssim r/D\lesssim 0.15\) is due to the effect of the hub wake. Together with (a), the similarity suggests that up to β = 40o, the flow follow the vane surface and is within a similarity regime at the nozzle exit. In contrast, when \(\beta \geqslant 50^{o}\), U𝜃 clearly deviates from the same behaviour with its value drop at small r, implying a fundamental change of the flow has occurred. These U𝜃 profiles are clearly non-solid-body rotation type, for which it would obey the linear relationship U𝜃(r) =Ωr. For \(\beta \leqslant 40^{o}\), this is owing to the fact that the measurement plane is very close the the swirler geometries, where the hub wake is strong. Flow mixing takes place very quickly, i.e. ∂U𝜃/∂r smoothes out quickly as the flow convects downstream. Our experiments with a longer mixing tube 1.5D (instead of 0.125D as shown in Fig. 1c) demonstrate much improved linear U𝜃 profiles against r. However, as discussed, longer mixing tube is not suitable for short L/D study.

Close examination of Ux along the central axis in Fig. 4c confirms the second recirculation bubble (Ux < 0, ‘Recirculation bubble 2’ in Fig. 3b) coexisting at moderate β further downstream, which is observed in many previous studies when the swirling jet breaks down [41, 42]. In consistent with these studies, as β increases, breakdown occurs earlier reflected by the recirculation bubble moving upstream with a stronger reverse flow peak. It also reduces the extent of the reverse flow behind the hub. At β = 60o, the two recirculation bubbles merge, which leads to a large U𝜃 peak in the r direction in (b). These features render the solid-body rotation type U𝜃 not physically possible.

The profiles displayed in Fig. 4 are not sensitive to Re, for \(Re\gtrsim 5000\); figure not shown. The dependence of the fluctuating axial and azimuthal velocities on r is shown in Fig. 5. The profiles of smaller β swirlers show good similarity. It suggests that ux, rms is insensitive to β but u𝜃, rms scales with the mean swirling strength. In (a), the two local ux, rms peaks at r ≈ 0.15D and 0.45D correspond to the inner and outer shear layers respectively. Similar to Fig. 4a, smaller β also pushes the inner shear layer closer to the centreline. Both profiles also display a general decreasing trend as r increases until the outer shear layer is reached. Swirlers of β = 20o and 60o are clearly off-trend; the former is most probably due to the larger uncertainty of PIV measurement when the in-plane flow velocity is much smaller than the laser-sheet-normal component and the later is in line with the findings in Fig. 4a–b.

Dependence of the fluctuating velocity ux, rms (streamwise component, a) and u𝜃, rms (azimuthal component, b) on r at x = 0.125D. u𝜃, rms is obtained from the (y − z) plane measurement and has been averaged in the 𝜃 direction; ux, rms is obtained from (x − z) plane measurement. In (b), β = 0o is not measured due to very small in-plane velocity rendering a large uncertainty

Using the U𝜃 profile in Fig. 4b, the steady state (jet) S associated with each swirler can be calculated by Eq. 2. Figure 6a shows its transient behaviour, denoted as Strn. Essentially it reflects the growth of a starting swirling jet. The dimensionless formation time tU0/D is corrected by accounting for the piston acceleration and the time taken due to the distance from the nozzle exit to the measured plane (0.125D), i.e.,

where a = 25 m/s2 is the piston acceleration. Evidently, Strn exhibits a linear growth over \(0.5\lesssim tU_{0}/D\lesssim 1\) and a clear overshooting at its maximum Strn ≈ 1.5S. The Strn patterns of all the swirlers agree very well, except β = 20o, due to the same reason as that for Fig. 5. The overshooting effect is attributed to the entrainment process governed by the induced velocity during formation, which can also be seen in non-swirl starting jet [43]. The near zero Strn for tU0/D < 0.5 is because of the non-swirling flow in the mixing section. By tU0/D ≈ 3.5, steady state is reached and the leading ring propagates away. The calculated S at steady state for all the swirlers are presented in Fig. 6b, displaying a clear increasing trend, almost linear with β. Hereafter, S is used to denote swirl strength.

Swirling number variation with formation time (a) and the steady swirling number of different nozzles (b) determined by PIV. The non-dimensional formation time is corrected by counting for the piston acceleration in the beginning and the time consumption due to the distance from the nozzle exit to the measured plane

Although the current study does not aim to focus on the coherent vortex structures, it has been well investigated in previous studies that the azimuthal mode m observable is primarily determined by S [24]. It is found that (at Re = 1,000) there exist two critical S: Scr1 = 0.6 and Scr2 = 0.88, dividing the S range into three sections. For \(0\leqslant S<S_{cr1}\), spiral waves are merely secondary instabilities; for Scr1 < S < Scr2, m = 2 or 3 co-exist but are less coherent; while for S > Scr2, a strong wave is stabilised at m = 1. Following the same definition of S in Eq. 2, the designed swirlers cover the entire S range and β = 60o swirler produces a jet with S > Scr2. It may explain the off-trend behaviour of this case in Figs. 4 and 5.

4.2 The formation process

The evolution of circulation in r − x (or x − z) plane, viz. Γ𝜃 is a useful quantity to describe the formation process of swirling rings. Γ𝜃 must be differentiated from the circulation in r − 𝜃 (or y − z) plane, viz. Γx, which is also non-zero because of swirl but is not our focus. Using Kelvin-Stokes theorem, Γ𝜃 can be calculated as

where l is the closed loop enclosing half of the flow domain Σ downstream the nozzle exit in r − x plane. For simplicity reason, we omit the subscript 𝜃 hereafter. Variables which are not of 𝜃 component will be otherwise indicated. Failure of energy delivery from the piston to the leading ring for L/D > F (where F is the formation number) leads to the pinch-off of the latter carrying limited energy (circulation) [11]. To find this limiting L/D, a long piston stroke L/D = 6 is applied in current experiments. Measurement is performed at an equivalent dimensionless time interval ΔtU0/D = 0.625. For each S case, 20 repeated measurements are conducted and then averaged.

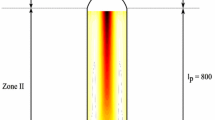

In order to evaluate the effect of swirl profile on the formation process, LES simulation is conducted with solid-body rotation enforced on the nozzle exit velocity profile, i.e. Eq. 3. One realisation for each S is simulated and Γ is calculated after performing an azimuthal average on the instantaneous flow field. A universal threshold ωD/U0 = 1 (≈ 3% of \(\omega _{\max \limits }\)) is applied to both PIV and LES results, to separate the pinched-off leading structure and the trailing jet. Unlike the flow generated by an empty nozzle (without straight vanes), incorporating a swirler results in complex boundary layer material washed from the vane surface to the ring structure and manifests significant ω of opposite sign. They interact with the ring core ω along the inner and the outer shear layer as shown in Fig. 7a. Area of ω > 0 represents the primary vortex core which is originated from the boundary layer along the nozzle inner wall, while ω < 0 is from the swirler, e.g. the high intensity area at r < 0.2D and x < 0.2D is attributed to the shear layer on the central hub surface. It is plausible that swirl motion does not generate negative vorticity since it is not seen in LES simulation (Fig. 7b). Given the fact that only the positive vorticity takes responsibility of the ring formation, area of ω < 0 in the PIV results is excluded in calculating Γ𝜃 using Eq. 10. However, it is expected that due to the vorticity cancellation, Γ decay of the leading ring in experiments will be faster than that in LES. The faster Γ decay diminishes the ring propagation velocity (known as celerity Ce), since \(Ce\sim \varGamma /(4\pi R_{b})\), taking a laminar thin-cored ring as approximation, where Rb is the ring radius. This explains that rings in LES propagate further downstream those in experiments at the same time.

Γ calculated from PIV and LES are presented in Fig. 8. The total Γ of the entire flow field exhibits a linear increment, not surprisingly, since the flux of the boundary layer from the nozzle inner surface is at a steady rate. For all S, the rate of Γ increment in PIV overtakes that in LES. This is owing to the overshoot of maximum Ux at the nozzle exit, compared to the idealised situation in LES; see Fig. 4. In addition, LES produces slightly higher initial circulation values than PIV due to PIV’s defect in capturing the vorticity field very close to the nozzle exit. The maximum \(\varGamma _{\max \limits }\) achieved are about 3.5DU0 and 3.0DU0 respectively. After that, as the slug stops and the total Γ drops rapidly due to strong turbulence interaction in the wake. However as S increases, \(\varGamma _{\max \limits }\) gradually decreases and the total Γ starts to loose its linearity during the slug. For instance for S = 0.6, \(\varGamma _{\max \limits }\) decreases to about 2.5DU0 with a clear change of total Γ increment rate at t ≈ 3D/U0. These are attributed to the stronger turbulence in both the leading ring and the wake as S increases and the flow field approaches to a swirling jet.

The leading vortex ring starts to pinch off and separate from its wake before the piston stops. The Γ of the leading ring is calculated when the separation is clear enough after the slug stops. As shown in Fig. 8, both PIV and LES display a near-linear Γ decay of the pinched-off ring, while the PIV results exhibit significantly higher rate than LES. The general decay behaviour is a result of turbulence at high Re and the higher decay rate in PIV is a direct consequence of the vorticity cancellation due to the effect of the swirlers, as shown in Fig. 7. In addition, as S increases, the decay rate is appreciably larger, much clearer in PIV results. Since the increased decay rate is also reflected in LES which has idealised solid-body rotation swirl, it can be concluded that swirl strength imposes a direct positive effect on the decay of the circulation. It will be shown in Section 4.3 that the ring radius Rb increases with S because of the centrifugal effect, which tends to stretch the vortex core in the 𝜃 direction. The Γ decays under the viscous effect (higher vorticity gradient causing faster vorticity peak decay). Such a decay is somewhat not clear in a previous experiment [17] probably due to an order of magnitude smaller Re.

It is important to note that Γ of the pinched-off ring does not decay strictly linearly, especially over a longer time. According to similarity theory [13], for a highly turbulent isolated vortex ring with S = 0,

However, for a short x range and under the influence of the wake vorticity, the Γ decay can be well approximated to be linear, as evidenced in Fig. 8. Probably coincidently, the decay of Γ for S > 0 cases also show a near-linear behaviour. For this reason, linear fit is utilised as an approximation. Γ decay will be further discussed in Section 4.3.

The formation number F is obtained from the abscissa of the intersection point of the fitted line and the total Γ, as shown in Fig. 8a. The ordinate of the intersection point represents the Γ of the ring at the moment of pinch off, which is the maximum Γ obtainable for a swirling ring, denoted as \(\varGamma _{\max \limits }^{R}\).

Dependence of F on S is shown in Fig. 9. It is noted that both measurement and simulation indicate F ≈ 2.6 at S = 0, appreciably lower than that found previously (F ≈ 4) [11]. It has been shown that F can be reduced by as much as 75% by manipulating the nozzle exit velocity profile [12]. At S = 0, it is plausible that in addition to the high Re deployed in present study, incorporating of the swirl component modifies vorticity distribution during formation. It will be further elaborated in Section 4.3. The decreasing F upon S is thus also a velocity profile effect. Evidenced in Fig. 9, \(\varGamma _{\max \limits }^{R}\) decreases almost in a linear manner as S, which is in line with a finding [17]. For both F and \(\varGamma _{\max \limits }^{R}\), the results between measurement and simulation agree fairly well. It suggests that the nozzle exit velocity profile has a minor effect on the formation process whether it is strictly solid-body rotation.

4.3 Early stage evolution

Figure 9 shows that the minimum F in the present study is marginally above 1.5. Therefore setting L/D = 1.5 ensures compact structures without wake behind for rings of all S. Recalling Fig. 6a, S is a function of formation time. At L/D = 1.5, S has not reached its steady state yet but has passed the maximum Strn. Since this is the nature of the flow generated by the swirlers, we shall continue with S (steady) as the denotation of the swirlers. The ensemble averaged ω fields using 50 realisations are presented in Fig. 10 and the azimuthally averaged ω from LES are presented in Fig. 11 for comparison.

Azimuthally averaged ω distribution at tU0/D = 3 from LES, in moving frame of reference. a–f are the same S in Fig. 10

In both figures, streamlines are plotted as if the observer is moving at the same instantaneous velocity (Ce) as the ring structure. Ce is determined from the vortex core trajectories which will be explained later. Only the streamlines which bypass the ring core are plotted, i.e. fluid in the region marked by the red arrows is entrained into the core area, which is denoted here as entrainment region. Note the accuracy of the streamline shape is limited by the PIV spatial resolution. Figure 10a is the zero swirl vortex ring but generated by the swirler with straight vanes. Unlike Fig. 11a or vortex rings generated by a normal empty nozzle or orifice [14], where nearly closed ellipsoidal bubble is formed around the core and travels with it, straight vanes result in an open bubble. This is originated from the reverse flow behind the central hub of the swirler. At the leeward side of the bubble, the streamlines are closed. Small portions of negative vorticity are seen in both figures as marked by the red dashed lines. One of the reasons is the vane and hub effect in experiments which has been discussed in Fig. 7. Moreover, the rolling-up process of the vortex ring in swirling flows also induces the negative vorticity as can be observed in Fig. 11b–f even though the vanes and hub are absent. This vorticity decays as it interacts with the vortex core as the ring moves downstream and is fully dissipated by tU0/D = 6 (not shown in the figures). It appears that by this time, the effect of swirler and the rolling-up process are worn off, leaving only the compact vortex core, given L/D = 1.5.

Figure 10 also shows that as S increases, the size of the entrainment region enlarges. At S ≥ 0.41, the reverse flow caused by the swirling effect and the hub merge. Some streamlines near the centre therefore pass through the ring without being entrained to the core area. At the same time, the entrainment region enlarges significantly. This phenomenon is somewhat different in the LES results. In Fig. 11, no clear entrainment region is noticed, even when swirl becomes strong, nor does any streamline pass through the ring at centre, i.e. the bubble is always closed. It seems that generated by idealised solid-body-rotation in an ‘empty’ nozzle, the only effect of swirl is to shrink the bubble size at the centreline. It thus suggests that swirler generated rings have stronger entrainment and mixing effect with ambient fluid, although this should be further justified using the time-resolved PIV measurements as the streamlines are not the reflection of the fluid trajectory. The consequence is that the ring size (reflected by Rb) would increase more rapidly, which is evidenced in the behaviour of their trajectories.

Figure 12 shows the time evolution of Γ of the rings (L/D = 1.5, whilst in Fig. 8L/D = 6). The ω < 0 part is not considered as part of the coherent ring structure. A threshold ωD/U0 = 1 is also applied to exclude the weak vorticity that has not been rolled up into the ring. Both PIV and LES results are included, together with a benchmark PIV case of zero-swirl vortex ring produced by an ‘empty’ nozzle. It is evident that comparing the S = 0 cases, LES successfully captures the Γ decay rate (∂Γ/∂t) and within expectation, the absolute Γ value is marginally higher in LES results, owing to the higher spatial resolution. The swirler vanes introduce clear effect of accelerating Γ decay at early time (tU0/D < 6) by cancellation of opposite sensed vorticity and increasing the turbulence dissipation. By \(tU_{0}/D\gtrsim 6\), as the opposite sensed vorticity dissipated completely, ∂Γ/∂t approximately matches that without swirler.

Apparently, the circulation decay rate ∂Γ/∂t increases as S, for both PIV and LES. For the same S, ∂Γ/∂t is higher in PIV than in LES at early time \(tU_{0}/D\lesssim 6\), due to the swirlers. At larger time after the secondary vorticity is dissipated \(tU_{0}/D\gtrsim 10\), the decay rate becomes similar, i.e. the difference between Γ of LES and PIV at the same S is mainly attributed to the early time decay. Note that rings of S = 0.87 and 1.10 in experiment are completely dissipated at tU0/D ≈ 18 and 12, respectively.

Figure 13 presents the time evolution of the vortex core location in the axial (a) and radial (b) directions. The axial trajectory of the ring core at S = 1.10 on coarse grid (1-level refinement) is also plotted in Fig. 13a for the grid-convergence test, which indicates that the 2-level refinement is enough for the current LES simulation. The core location is determined by the |ω| weighted centroid based on 50% threshold [13]. Here, an empirical function is defined in order to collapse data both PIV and LES, both axial location X and radial location r. Inspired by the dependence of F on S in Fig. 8, after many trials, Eq. 12 appear to yield the best scaling effect.

This scaling is shown to work well for 0 < S < 1.1. S = 0 refers to zero-swirl vortex rings while S = 1.1 is larger than Scr2; see Fig. 6. Since the celerity can be inferred from X, viz. Ce = ∂X/∂t, Eq. 12 also works for Ce.

In Fig. 13a, the formation time tU0/D ≈ 6 seems to be a demarcation for the scaled axial trajectory X/(φ3D). For \(tU_{0}/D\lesssim 6\), X and hence Ce is strongly influenced by the secondary vorticity of both senses according to Biot-Savart law. Interestingly, there is no strong difference between LES and PIV results. Beyond this time, however, as only the vortex core remains (secondary vorticity blobs have all vanished, figure not shown), clear difference can be observed for the scaled Ce between PIV and LES (alse see Fig. 14a for the celerities at tU0/D > 8.5, which is calculated from the linear approximation of the ring core trajectory in the region), reflected by the distinctive slopes of the scaled X. In addition, the scaled Ce becomes approximately constant regardless of S. Cheng et al. [20] showed that the strong interaction of the secondary vortices with the primary ring core at Re = 800 with strong swirl, results in slowdown or even backward motion of the primary ring. The slowdown behaviour is clearly seen in PIV result after tU0/D = 6 (the decreased slope of X/(φ3D), while the backward motion is not observed in either PIV or LES result, up to the end of the field of investigation. This probably is because of the higher Re in the present study.

PIV result without the swirler (S = 0) is also present in (a), which agrees very well with LES data and serves as another validation of the LES simulation (so for the r data in b). The smaller Ce of S = 0 with straight vanes, i.e. slower increment of X on t, is a direct result of a higher Γ decay at early time as shown in Fig. 12.

A demarcation time can also be seen in (b) for the scaled radial trajectory rφ/D, which is at tU0/D ≈ 3. Beyond this time, split of PIV and LES data is displayed unequivocally for the data within the range 0 < S < 1.1. The PIV data also shows two rφ/D growth rates, separated at \(tU_{0}/D\approx 6\sim 7\). At later time, the scaled growth rates agree well for PIV and LES, indicating the ring propagation velocity in r direction, Cr, also scales with φ− 1 at large time. Over 3 < tU0/D < 7, PIV results show an obvious larger increment rate for rφ, which is not captured by LES. Comparing the three cases with S = 0, the larger r with vanes is consistent with their Ce in (a). The roughly constant celerity Cr at tU0/D > 8.5 computed by linear fitting of the trajectory in this region is also presented in Fig. 14b, showing good agreement between PIV and LES results, specially for low S numbers.

Combining these findings, it is possible to obtain the following empirical scaling relations for 0 < S < 1.1 and \(tU_{0}/D\gtrsim 6\), based on the empirical φ in Eq. 12, viz.

The relation in Eq. 13 is deduced from Fig. 13, which is directly extracted from the experimental and numerical flow fields and is applied to the part where the scaled X and r appeared approximately linear. According to theoretical formulation [3], celerity Ce of a thin-cored toroidal-shaped vortex ring with zero swirl, at steady state obeys \(Ce\sim {\Gamma }/R_{b}\). This suggests a decaying Ce because of diminishing Γ (Fig. 12) and slowly increasing Rb (Fig. 13b). The discrepancy to the observation could be explained as follows: the PIV results presented here are based on statistical analysis; the theoretical formulation is based on thin-cored vortex ring assumption, when S increases from zero, the vortex core (in 2D fiew) becomes significantly thick, especially at large time (figure not shown). This could completely invalidate the theoretical scaling. Other factors include high level of turbulence and the secondary opposite signed vorticity around the core region as it is shown in Figs. 10 and 11 which are absent in zero swirl vortex rings.

Instantaneous spatial flow structures of the swirling vortex ring, e.g. the shape of the vortex core, at large S and especially under the influence of the swirlers at high Re, deserve further study. According to a swirling jet study [24], S presently studied covers the two Scr characterising four dynamic regimes of a swirling jet; see Fig. 6. Whether the same regimes can be seen in compact ring generated by short L/D, i.e. whether the ring remains toroidal shape, is left to our future work.

5 Conclusion

In this work, the dependence of formation process and early stage evolution of vortex rings on swirl number S, at Re = 20,000 (based on nozzle diameter D), were investigated using both experimental measurement (planar-PIV) and numerical simulation (LES). In experiments, axial swirlers were used to generate swirl and S produced covers all the dynamic regimes and the two critical swirl number Scr1 and Scr2 identified in a continuous swirling jet at a lower Re [24]. Although it was found that solid-body rotation was not possible at the nozzle outlet for physical reasons, the dependence on S strength, good azimuthal velocity homogeneity and their profile similarity across different swirlers were achieved. In LES idealised solid-body rotation at the same S as in experiments were enforced in order to evaluate the effect of the velocity profile generated by swirlers.

Study of the formation process revealed that formation number F decreased with increasing S, approximately in a linear way, with the maximum F ≈ 2.6 for S = 0 (with straight vanes) and the minimum F ≈ 1.9 at S = 1.1. The lower F than that reported in literatures (F ≈ 4) [11] for zero-swirl ring was associated with the high Re and the swirling nozzle exit velocity profile, which leaded to interaction of the primary vortex core and the secondary vorticity. The maximum strength of the leading ring, quantified by the maximum circulation \(\varGamma _{\max \limits }^{R}\) in r − x (or x − z) plane, attainable at tU0/D = F, also diminished as S increased. The agreement of PIV and LES for both F and \(\varGamma _{\max \limits }^{R}\) suggested that the formation process, at least for the two variables concerned, was not sensitive to the detailed nozzle exit velocity profile.

The early stage evolution of compact swirling rings were also investigated. The compactness was ensured by using short stroke L = 1.5D, which was smaller than the minimum F in the current study. Due to the effects of the vanes, the entrainment region of the vortex ring enlarged accompanied by a central ‘reverse-through’ as S increased. Firstly, the overall circulation Γ decrease in time as expected and its decay rate was proportional to S. At tU0/D < 6, Γ decay rate was appreciably higher in experiments than in LES, owing to the vane effects. Beyond this time, nevertheless, the decay rate tended to be similar. Secondly, by introducing an empirical scaling function φ well worked for 0 < S < 1.1, it showed that the behaviour of the scaled ring trajectory in streamwise and spanwise direction, X/(φ3D) and rφ/D respectively, and therefore the propagation velocity in the two directions Ce and Cr, changed at tU0/D ≈ 6. In general, Ce decreased but Cr increased with S. At larger time, the value of Ce and Cr showed clear difference between PIV and LES results, which was believed to be the consequence of the Γ decay at early time.

References

Meng, X., de Jong, W., Kudra, T.: A state-of-the-art review of pulse combustion: principles, modeling, applications and R&D issues. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 55, 73–114 (2016)

Syred, N., Beer, J.M.: Combustion in swirling flows: A review. Combust. Flame 23(2), 143–201 (1974)

Shariff, K., Leonard, A.: Vortex rings. Ann. Rev. Fluid Mech. 24(1), 235–279 (1992)

Glezer, A., Coles, D.: An experimental study of a turbulent vortex ring. J. Fluid Mech. 211, 243–283 (1990)

Oberleithner, K., Sieber, M., Nayeri, C.N., Paschereit, C.O., Petz, C., Hege, H.-C., Noack, B.R., Wygnanski, I.: Three-dimensional coherent structures in a swirling jet undergoing vortex breakdown: Stability analysis and empirical mode construction. J. Fluid Mech. 679, 383–414 (2011)

Liao, Y.H., Hermanson, J.C.: Turbulent structure and dynamics of swirled, strongly pulsed jet diffusion flames. Combust. Sci. Technol. 185(11), 1602–1623 (2013)

Didden, N.: On the formation of vortex rings: Rolling-up and production of circulation. Zeitschrift für angewandte Mathematik und Physik ZAMP 30(1), 101–116 (1979)

Olcay, A.B., Krueger, P.S.: Measurement of ambient fluid entrainment during laminar vortex ring formation. Exp. Fluids 44(2), 235–247 (2008)

Auerbach, D.: Stirring properties of vortex rings. Phys. Fluids A: Fluid Dyn. 3 (5), 1351–1355 (1991)

Maxworthy, T.: Some experimental studies of vortex rings. J. Fluid Mech. 81 (3), 465–495 (1977)

Gharib, M., Rambod, E., Shariff, K.: A universal time scale for vortex ring formation. J. Fluid Mech. 360, 121–140 (1998)

Rosenfeld, M., Rambod, E., Gharib, M.: Circulation and formation number of laminar vortex rings. J. Fluid Mech. 376, 297–318 (1998)

Gan, L., Nickels, T.B.: An experimental study of turbulent vortex rings during their early development. J. Fluid Mech. 649, 467–496 (2010)

Gan, L., Nickels, T.B., Dawson, J.R.: An experimental study of a turbulent vortex ring: a three-dimensional representation. Exper. Fluids 51(6), 1493–1507 (2011)

Ghaem-Maghami, E., Johari, H.: Velocity field of isolated turbulent puffs. Phys. Fluids 22(11), 115105 (2010)

Ghaem-Maghami, E., Johari, H.: Concentration field measurements within isolated turbulent puffs. J. Fluids Eng. 129(2), 194–199 (2007)

Naitoh, T., Okura, N., Gotoh, T., Kato, Y.: On the evolution of vortex rings with swirl. Phys. Fluids 26(6), 95–149 (2014)

Gargan-Shingles, C., Rudman, M., Ryan, K.: The evolution of swirling axisymmetric vortex rings. Phys. Fluids 27(8), 087101 (2015)

Gargan-Shingles, C., Rudman, M., Ryan, K.: The linear stability of swirling vortex rings. Phys. Fluids 28(11), 23–47 (2016)

Cheng, M., Lou, J., Lim, T.T.: Vortex ring with swirl: A numerical study. Phys. Fluids 22(9), 097101 (2010)

Billant, P., Chomaz, J., Huerre, P.: Experimental study of vortex breakdown in swirling jets. J. Fluid Mech. 376, 183–219 (1998)

Umeh Chukwueloka, O.U., Rusak, Z., Gutmark, E., Villalva, R., Cha, J.D.: Experimental and computational study of nonreacting vortex breakdown in a swirl-stabilized combustor. AIAA J. 48, 2576–2585 (2010)

Loiseleux, T., Chomaz, J.: Breaking of rotational symmetry in a swirling jet experiment. Phys. Fluids 15(2), 511–523 (2003)

Liang, H., Maxworthy, T.: An experimental investigation of swirling jets. J. Fluid Mech. 525, 115–159 (2005)

Meliga, P., Gallaire, F., Chomaz, J.: A weakly nonlinear mechanism for mode selection in swirling jets. J. Fluid Mech. 699, 216–262 (2012)

Gallaire, F., Chomaz, J.: Mode selection in swirling jet experiments: A linear stability analysis. J. Fluid Mech. 494, 223–253 (2003)

Candel, S., Durox, D., Schuller, T., Bourgouin, J.B., Moeck, J.P.: Dynamics of swirling flames. Ann. Rev. Fluid Mech. 46, 147–173 (2014)

Konle, M., Sattelmayer, T.: Interaction of heat release and vortex breakdown during flame flashback driven by combustion induced vortex breakdown. Exp. Fluids 47(4-5), 627 (2009)

Umeh Chukwueloka, O.U., Rusak, Z., Gutmark, E.: Vortex breakdown in a swirl-stabilized combustor. J. Propuls. Power 28(5), 1037–1051 (2015)

Paschereit, C.O., Gutmark, E., Weisenstein, W.: Excitation of thermoacoustic instabilities by interaction of acoustics and unstable swirling flow. AIAA J. 38(6), 1025–1034 (2012)

O’Connor, J., Lieuwen, T.: Recirculation zone dynamics of a transversely excited swirl flow and flame. Phys. Fluids 24(7), 293–364 (2012)

Paschereit, C.O., Gutmark, E., Weisenstein, W.: Structure and control of thermoacoustic instabilities in a gas-turbine combustor. Combust. Sci. Technol. 138 (1-6), 213–232 (1998)

Glezer, A.: The formation of vortex rings. Phys. Fluids 31(12), 3532–3542 (1988)

Durox, D., Moeck, J.P., Bourgouin, J., Morenton, P., Viallon, M., Schuller, T., Candel, S.: Flame dynamics of a variable swirl number system and instability control. Combust. Flame 160(9), 1729–1742 (2013)

Germano, M., Piomelli, U., Moin, P., Cabot, W.H.: A dynamic subgrid-scale Eddy viscosity model. Phys. Fluids: Fluid Dyn. 3(7), 1760–1765 (1991)

Lilly, D.K.: A proposed modification of the germano subgrid-scale closure method. Phys. Fluids A: Fluid Dyn. 4(3), 633–635 (1992)

Akselvoll, K., Moin, P.: Large-eddy simulation of turbulent confined coannular jets. J. Fluid Mech. 315, 387–411 (1996)

Ghaisas, N.S., Shetty, D.A., Frankel, S.H.: Large eddy simulation of turbulent horizontal buoyant jets. J. Turbul. 16(8), 772–808 (2015)

He, C., Liu, Y., Yavuzkurt, S.: Large-eddy simulation of circular jet mixing: Lip-and inner-ribbed nozzles. Comput. Fluids 168, 245–264 (2018)

Choi, J.J., Rusak, Z., Kapila, A.K.: Numerical simulation of premixed chemical reactions with swirl. Combust. Theory Modell. 11(6), 863–887 (2007)

Beér, J. M., Chigier, N.A.: Combustion Aerodynamics. New York (1972)

Gupta, A.K., Lilley, D.G., Syred, N.: Swirl Flows, p 488. Abacus Press, Tunbridge (1984)

Gan, L.: An Experimental Study of Turbulent Vortex Rings Using Particle Image Velocimetry. University of Cambridge, PhD thesis (2010)

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge financial support for this study from UK EPSRC grant number EP/P004377/1. The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

He, C., Gan, L. & Liu, Y. The Formation and Evolution of Turbulent Swirling Vortex Rings Generated by Axial Swirlers. Flow Turbulence Combust 104, 795–816 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10494-019-00076-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10494-019-00076-2