Abstract

The impact of initiatives aimed at reducing time in untreated psychosis during early-stage schizophrenia will be unknown for many years. Thus, we simulate the effect of earlier treatment entry and better antipsychotic drug adherence on schizophrenia-related hospitalizations, receipt of disability benefits, competitive employment, and independent/family living over a ten-year horizon. We predict that earlier treatment entry reduces hospitalizations by 12.6–14.4% and benefit receipt by 7.0–8.5%, while increasing independent/family living by 41.5–46% and employment by 42–58%. We predict larger gains if a pro-adherence intervention is also used. Our findings suggest substantial benefits of timely and consistent early schizophrenia care.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Schizophrenia is a devastating mental illness that affects cognitive functioning and manifests through “positive” psychotic symptoms such as paranoid delusions, and “negative” symptoms such as apathy (Weinberger and Harrison 2011). It has a disproportionately large burden of disease partly due to its early age of onset, typically in early adulthood, and its chronic course and poor long-term outcomes (Whiteford et al. 2013). In the U.S., more than three in four persons with schizophrenia lack gainful employment and depend on income supports (Bilder and Mechanic 2003; Rosenheck et al. 2006) and among homeless persons, approximately one in five have a schizophrenia diagnosis (Folsom et al. 2005). Moreover, relapses with exacerbation of positive symptoms leading to hospitalization or incarceration remain a common occurrence (Ascher-Svanum et al. 2010). Consequently, the illness exacts high costs to society, estimated at $155.7 billion for the U.S. in 2013, with excess healthcare costs and costs associated with unemployment accounting for 24% and 38%, respectively, of the overall costs (Cloutier et al. 2016).

As a result of scientific advances, the ravages of this illness can be effectively treated. Antipsychotic drugs can control positive psychotic symptoms, and evidence-based psychosocial interventions such as supported employment, supported housing, and assertive community treatment, can improve employment and housing outcomes, reduce homelessness, and reduce hospitalizations (e.g., Kreyenbuhl et al. 2009). However, these potential improvements are often not realized. Key drivers of this research to practice gap include the limited use of interventions to address poor adherence to antipsychotic medication, and limited access to high-quality psychosocial treatments (e.g., Horvitz-Lennon et al. 2009, Kane et al. 2013).

Empirical research has shown an association between longer “duration of untreated psychosis” (DUP) during the first episode of psychosis, and short- and long-term clinical and functional outcomes (Boonstra et al. 2012; Marshall et al. 2005; Penttilä et al. 2014; Perkins et al. 2005). Because this association is unique to the early stage of the illness, this stage is considered to be a “critical period” of the illness (Birchwood et al. 1998; Crumlish et al. 2009). Although the evidence on this association is largely correlational, the consistency of the signal generated by a large body of research of varied methodology suggests that, for most individuals, the association is likely causal (Srihari 2018).

Emerging evidence suggests that “time in psychosis” accrued during the critical period after entering treatment may be as consequential for long-term outcomes as the pre-treatment DUP (Friis et al. 2016). In other words, the overall time in uncontrolled psychosis, i.e., the DUP accrued prior to treatment entry, and the time in psychosis accrued after accessing care due to ineffective treatment, may have significant prognostic implications. Thus, short- and long-term benefits associated with DUP reduction may extend to any intervention that reduces time in psychosis following entry into care, including pro-adherence interventions and continuous engagement in specialized programs.

The reasons for the extraordinary significance of untreated psychosis during the “critical period” have not been elucidated. An as yet unconfirmed hypotheses is that psychotic symptoms might have neurotoxic effects (Rund 2014). An alternative or complementary hypothesis is that emergence of psychosis in the late teens/early twenties disrupts individuals’ ability to make developmentally appropriate progress.

The evidence linking untreated psychosis and outcomes has generated strong interest as it provides the first indication that there is a role for secondary prevention in schizophrenia. The existence of this narrow window for timely and consistent treatment in early-stage schizophrenia suggests a “time is brain” treatment paradigm akin to the treatment approach that so radically improved the prognosis of ischemic stroke. This paradigm shift is particularly important in the U.S. context for two reasons. First, delays in access to care for patients with early schizophrenia are longer compared to other industrialized countries (Kotov et al. 2017). Secondly, long-acting injectable (LAI) antipsychotic formulations, a widely available pro-adherence intervention, are underused, as evidenced by the fact that LAI agents are prescribed to just one of every ten early-stage patients (Robinson et al. 2014).

High-level initiatives have sought to promote early intervention services that aim to reduce DUP and improve patient outcomes by facilitating access to evidence-based care for people with early schizophrenia and others experiencing a first episode of psychosis. For example, the National Institutes of Mental Health (NIMH) funded the 2008 the “Recovery After an Initial Schizophrenia Episode” (RAISE) initiative to evaluate the effectiveness of an early intervention program, the Coordinated Specialty Care (CSC) model (National Institute of Mental Health). CSC is a team-based program that provides antipsychotic medication treatment, assertive case management, cognitive-behavioral psychotherapy, supported employment and education, and family education and support (Heinssen et al. 2014). A RAISE-sponsored randomized controlled trial showed that patients treated in non-academic CSC programs remained in treatment longer, experienced greater improvement in quality of life and symptomatology, and experienced greater involvement in work and school than patients receiving routine care (Kane et al. 2016). Although CSC patients’ DUP was comparable to that of patients in routine care, quality of life and symptom outcomes were substantially better for those with shorter DUP, a finding that prompted authors to state that “reducing DUP from current levels of > 1 year to the recommended standard of < 3 months should be a major focus of applied research efforts” (Kane et al. 2016). The moderating effect of DUP was recently replicated by a study that evaluated the effect of early intervention on negative symptoms (Dama et al. 2019). Building on these encouraging findings, the NIMH continues to solicit grant proposals on early intervention services (Department of Health and Human Services 2017). In addition to its grant-making initiatives, NIMH was instrumental in an effort to educate legislators on the potential benefits of reducing DUP, which eventually led to a new policy aimed at expanding access to evidence-based care for people with early psychosis. Starting in FY 2014, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) at the Department of Health and Human Services has required states to set aside a growing portion of the Mental Health Block Grant (MHBG) funds for CSC-like models (“Guidance for revision of the FY2016–2017 block grant application for the new 10 percent set-aside,” 2016). An early assessment of the “MHBG set-aside” policy in 12 states showed that the states had embraced the policy and as a result, access to services had improved; however, the early stage of program implementation did not permit systematic assessment of patient outcomes (Horvitz-Lennon et al. 2015).

Since the long-term effects of policies that aim to reduce DUP will not be known for many years, policymakers would benefit from estimates of their potential benefits to justify funding commitments, especially given the current fiscal environment. In this study, we seek to provide estimates based on the best available evidence. We use a microsimulation model to predict the long-term benefits of interventions to reduce the time in psychosis during the early phase of the illness, with and without accompanying efforts to improve medication adherence.

Methods

Model and Data

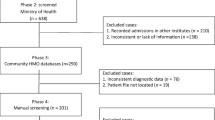

We use a microsimulation to model trajectories for 10,000 hypothetical patients over a ten-year period from onset of psychosis (for greater details on the model, see Horvitz-Lennon et al. 2018). The model consists of two components. The first is the critical period, which is divided into the time between onset of psychosis and treatment entry, i.e., the DUP, and a “Calibration Phase,” during which treatment starts and treatment decisions are varied. The second is the “Chronic Phase,” during which we predict long-term outcomes. Since the critical period is estimated to last 2–5 years following psychosis onset (Carpenter and Strauss 1991; Eaton et al. 1995), we selected a duration of 3 years. The simulated chronic phase lasts 7 years.

The model starts with the onset of a patient’s first psychotic episode. Patients access care after spending a randomly assigned and variable time in untreated psychosis, i.e., DUP. Immediately after entering care, patients receive antipsychotic treatment. Throughout the Calibration Phase, patients go through treatment cycles, during which they can experience treatment success if symptoms abate, i.e., treatment is effective, or treatment failure, if symptoms persist or return, which leads to accrual of time in psychosis. We use the term “Time in Uncontrolled Psychosis” to refer to the overall time in psychosis, which as above, is the sum of the DUP and the time in psychosis accrued after entering treatment. After the end of the critical period, we predict long-term outcomes over the seven-year chronic phase as a function of symptom severity at the end of the calibration phase expressed as Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS).

A comprehensive literature review combined with expert input provided model parameters as well as empirical support for design assumptions. We reviewed studies published after 1985 in English or Spanish on three broad topics: DUP’s short- and long-term effects; the comparative adherence and relapse effects of LAI and oral agents in early schizophrenia; and for outcome estimation, the association between PANSS and short- and long-term outcomes (for inpatient utilization, we limited our review to U.S. studies published between 2000 and 2017). We selected studies based on their relevance and methodological quality.

Key model parameters are drug efficacy, derived from the Scandinavian TIPS study (Friis et al. 2010), which evaluated the effectiveness of an early detection intervention relative to usual care; drug adherence, derived from a well-designed trial in first-episode patients (Subotnik et al. 2015); and probability of relapse, also derived from the first-episode trial (Subotnik et al. 2015). Key calibration phase assumptions (and supporting literature) include: (1) efficacy of antipsychotic treatment declines with increasing time in psychosis (Sarpal et al. 2017, Svein Friis, personal communication); and (2) antipsychotic adherence is determined by whether the patient received oral vs. LAI treatment (e.g., Taylor and Ng 2013; Tiihonen et al. 2011). As a result of these assumptions, treatment effectiveness in each treatment cycle is estimated as the product of time-varying efficacy and treatment-dependent probability of adherence. Two other assumptions are (3) DUP is the only characteristic that varies among patients entering calibration phase, i.e., they are comparable with regard to sociodemographic and clinical characteristics also associated with long-term outcomes (see Friis et al. 2016) for key characteristics); and (4) since the objective of our study is to predict the long-term effects of treatment decisions made during the critical period of schizophrenia, we assume that the effect of chronic phase treatment is identical for all patients.

Our outcomes of interest are schizophrenia-related admissions over the entire 10-year model horizon (defined as hospitalizations per 1000 patient-years), and three chronic phase outcomes: competitive employment, and independent or family living at the end of the chronic phase, as well as receipt of disability benefits, i.e., Supplemental Security Income (SSI) or Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI), at the start of the chronic phase. Sources for parameter values were peer-reviewed studies identified in our literature review (Olfson et al. 2011; Rosenheck et al. 2017; Slade and Salkever 2001; Tsai et al. 2011).

The model was programmed in Microsoft Excel Visual Basic for Applications.

Analytic Approach

We simulate the effect of two calibration phase variables on patient outcomes. The first is the time in psychosis before entering treatment (i.e., DUP). For each patient, the time is drawn randomly from three DUP distributions, short, medium, and long, all of them realistic benchmarks as they were reported in previous studies. The “short” DUP distribution comes from a population enrolled in a randomized controlled trial conducted in an academic center in Groningen, Netherlands, that assessed a treatment approach (antipsychotic dose reduction versus routine maintenance treatment) (“Dutch RCT”) (Wunderink et al. 2013); the “medium” DUP distribution was reported by a meta-analysis of studies that included U.S. and non-U.S. populations treated in academic and non-academic centers (“Multinational cohorts”) (Boonstra et al. 2012); and the “long” DUP distribution was reported by a study of patients receiving care in U.S. community clinics (“U.S. community clinics”) (Addington et al. 2015) (Table 1).

The second calibration phase variable is the choice of antipsychotic treatment. Our baseline assumption is that patients only receive oral agents, which is consistent with the typical treatment of early schizophrenia in the U.S. (Robinson et al. 2014). We compare those predictions against those achieved when switching patients to an LAI agent after the second oral treatment failure.

We conducted one-way and probabilistic sensitivity analyses to test the outcome effects of several model parameters including DUP and other calibration phase parameters.

The sponsor reviewed an earlier draft of the manuscript and provided comments, but the authors had full control over study design, execution, analysis and presentation of the results. The study was reviewed and considered exempt by our institution’s IRB.

Results

Figure 1 displays the model predictions for outcomes under the baseline condition for each of the three DUP scenarios mentioned above: Dutch RCT (short), multinational cohort (medium), and U.S. community clinics (long). For the baseline prediction, patients are treated with orals drugs only.

On average over the 10-year model horizon, we predict 333 schizophrenia-related hospitalizations per 1000 patient-years, if patients enter treatment with the long DUP observed in U.S. community clinics. The prediction decreases to 291 and 285 events per 1000 patient-years, respectively, if patients enter treatment with the shorter DUPs observed in the multinational cohort and the Dutch RCT, corresponding to relative reductions of 12.6% and 14.4% (Panel A). The proportion of patients who receive disability benefits at the beginning of the chronic phase (Panel B) is estimated to decline from 71%, assuming the long DUP observed in U.S. community clinics, to 66% and 65% if the shorter DUPs observed in the multinational cohort and Dutch RCT were the norm, corresponding to relative reductions of 7.0% and 8.5%, respectively. While approximately two out of five patients (41%) are predicted to live independently or with family 10 years after onset of psychosis assuming the long DUP observed in U.S. community clinics, the proportion would be higher, around three out of five, if the shorter DUPs observed in the multinational cohorts (60%) and the Dutch RCT (58%) were the norm (Panel C). Only 12% of patients are predicted to be competitively employed after 10 years assuming the long DUP observed in U.S. community clinics, but the proportion would be higher, close to two in five, if the DUP observed in the multinational cohorts (17%) and the Dutch RCT (19%) were the norm (Panel D).

Table 2 displays the predicted incremental effects of an intervention to improve adherence to antipsychotic drugs (LAI treatment after the second oral treatment failure) relative to the baseline condition (oral treatment only), for each of the DUP scenarios described above.

Improving adherence once patients enter treatment augments the gains from earlier treatment entry, albeit to a different degree. The largest difference is predicted for probability of competitive employment, which increases by 6% if patients enter treatment with the long DUP prevailing in U.S. community clinics, and by 39% and 56% if they do with the shorter DUPs observed in the multinational cohorts and the Dutch RCT. The smallest incremental benefit is for probability of independent or family living, estimated at 24% (long DUP), 24% (medium DUP) and 27% (short DUP), respectively. In patients entering treatment as early as in the Dutch RCT, the pro-adherence intervention is predicted to prevent another 49 admissions over 1000 patient-years. However, only about half as many admissions (29/1000 patient-years) are prevented assuming the long DUP prevailing in U.S. community clinics. Relative reductions in the probability of receiving disability benefits range from 31% (long DUP) to 40% (short DUP).

Sensitivity analyses provided support for the soundness of our model. In particular, they underscored the significance of the DUP since longer DUPs reduce the time window during the critical period for effective treatment to have long-term impacts.

Discussion

Schizophrenia is a highly impairing mental illness often associated with severe social and occupational impairment, which along with frequent relapses, exact high costs largely borne by the healthcare and social services systems. Recognition in the U.S. of this high disability burden coupled with mounting evidence that the prognosis of the illness can be improved through secondary prevention efforts targeting the early phase of the illness have spurred significant research and policy initiatives. Our study provides preliminary evidence in need of empirical confirmation on the expected returns from these initiatives.

Our simulation results suggest that earlier treatment entry is associated with meaningful improvements in the likelihood of independent or family living, competitive employment, receipt of disability benefits, and psychiatric hospitalization. Our results also suggest that these gains can be augmented by improving adherence to antipsychotic drugs during the early stage of the illness. While not widely available, evidence-based interventions to accelerate treatment entry and improve antipsychotic adherence do exist—these include early intervention services such as CSC, and pro-adherence interventions such as LAI antipsychotics (Mihalopoulos et al. 2009; Stevens et al. 2016).

If our predictions related to transitioning from our “current state” predictions (long DUP, oral treatment only) to our “best case” predictions (short DUP, early use of LAI treatment) are borne out, patients’ quality of life should improve (Gaite et al. 2002; Norman et al. 2000), and healthcare and social service spending should decrease.

We acknowledge that the predicted gains accomplished through earlier access to treatment and better adherence in early-stage schizophrenia are smaller than those reported for interventions that are typically implemented in the chronic phase of the illness. For example, supported employment can increase the rate of employment by 18–55% points (Drake et al. 2016), and supported housing inclusive of intensive case management or assertive community treatment can increase the rate of stable housing by 31% points (Aubry et al. 2015). However, these interventions are typically implemented later in the course of the illness, when patients have had years of living with a devastating illness, and their effects tend to dissipate after the interventions end.

Implications for Research

Although not all early intervention programs have been able to shorten DUP (Oliver et al. 2018), the goal of reducing DUP is attainable as demonstrated by successful programs (e.g., Melle et al. 2012). Over time, these programs coupled with efforts to improve antipsychotic adherence will generate sufficient numbers of treated individuals to enable empirical research of their long-term effects on clinical, functional, and economic outcomes.

Implications for Policy

Our findings offer support for current research and policy initiatives to reduce time in uncontrolled psychosis, including the previously mentioned NIMH’s funding opportunity and the “MHBG set-aside” policy, as well as Affordable Care Act-related insurance expansions (e.g., Beronio et al. 2014). Additional policy efforts include educational initiatives such as programs targeting non-specialist clinicians on the detection and management of early psychosis (e.g., Lester et al. 2009).

Quality improvement interventions such as academic detailing and audit & feed-back may be used to heighten attention to antipsychotic drug adherence in early schizophrenia and promote routine monitoring of adherence and greater use of evidence-based pro-adherence interventions. Greater use of LAI antipsychotics would require that providers have dedicated staff who can administer the injections. Payers could require ongoing measurement of antipsychotic drug adherence among beneficiaries with early-stage and chronic schizophrenia, for example, by using the relevant measure included in the core set of adult measures for Medicaid beneficiaries (Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services 2019).

Limitations

Our study has a number of limitations. This is a simulation study and as such, our findings are suggestive and in need of confirmatory empirical research. As any simulation study, we make several assumptions related to the structure and content of our model. Crucially, there is limited evidence on the effects of programs that aim to jointly reduce DUP and enhance antipsychotic drug adherence. However, we base all assumptions on empirical evidence augmented with expert opinion and our results are robust to different assumptions as demonstrated by our sensitivity analyses. Moreover, they are consistent with existing knowledge pertaining to early schizophrenia, namely, the critical importance of shortening time in psychosis, and better adherence outcomes for LAI agents relative to oral agents.

Conclusion

Our simulation findings provide policymakers with preliminary estimates of the potential gains in long-term outcomes from ongoing efforts aimed at facilitating access to early intervention services for people with schizophrenia. Our findings also point to the potential benefits of a deliberate focus on improving antipsychotic drug adherence. While these simulation results will need to be confirmed with direct empirical evidence, they provide an initial indication of the value of a “time is brain” treatment paradigm in early-stage schizophrenia.

References

Addington, J., Heinssen, R. K., Robinson, D. G., Schooler, N. R., Marcy, P., Brunette, M. F., et al. (2015). Duration of untreated psychosis in community treatment settings in the united states. Psychiatric Services,66(7), 753–756.

Ascher-Svanum, H., Zhu, B., Faries, D. E., Salkever, D., Slade, E. P., Peng, X., et al. (2010). The cost of relapse and the predictors of relapse in the treatment of schizophrenia. BMC psychiatry,10(1), 2.

Aubry, T., Nelson, G., & Tsemberis, S. (2015). Housing first for people with severe mental illness who are homeless: A review of the research and findings from the at home—chez soi demonstration project. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry,60(11), 467–474.

Beronio, K., Glied, S., & Frank, R. (2014). How the affordable care act and mental health parity and addiction equity act greatly expand coverage of behavioral health care. The Journal of Behavioral Health Services & Research,41(4), 410–428.

Bilder, S., & Mechanic, D. (2003). Navigating the disability process: Persons with mental disorders applying for and receiving disability benefits. The Milbank Quarterly,81(1), 75–106. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0009.00039.

Birchwood, M., Todd, P., & Jackson, C. (1998). Early intervention in psychosis. The critical period hypothesis. British Journal of Psychiatry,172(S33), 53–59.

Boonstra, N., Klaassen, R., Sytema, S., Marshall, M., De Haan, L., Wunderink, L., et al. (2012). Duration of untreated psychosis and negative symptoms—A systematic review and meta-analysis of individual patient data. Schizophrenia Research,142(1), 12–19.

Carpenter, W. T., Jr., & Strauss, J. S. (1991). The prediction of outcome in schizophrenia. IV: Eleven-year follow-up of the Washington IPSS Cohort. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease,179(9), 517–525.

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. (2019). Adult Health Care Quality Measures: Initial Core Set of Adult Health Care Quality Measures for Medicaid-Eligible Adults. Retrieved from Baltimore, MD https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid/quality-of-care/performance-measurement/adult-core-set/index.html.

Cloutier, M., Aigbogun, M. S., Guerin, A., Nitulescu, R., Ramanakumar, A. V., Kamat, S. A., et al. (2016). The economic burden of schizophrenia in the united states in 2013. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry,77(6), 764–771.

Crumlish, N., Whitty, P., Clarke, M., Browne, S., Kamali, M., Gervin, M., et al. (2009). Beyond the critical period: Longitudinal study of 8-year outcome in first-episode non-affective psychosis. The British Journal of Psychiatry,194(1), 18–24.

Dama, M., Shah, J., Norman, R., Iyer, S., Joober, R., Schmitz, N., et al. (2019). Short duration of untreated psychosis enhances negative symptom remission in extended early intervention service for psychosis. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. https://doi.org/10.1111/acps.13033.

Department of Health and Human Services. (2017). Initiation of a mental health family navigator model to promote early access, engagement and coordination of needed mental health services for children and adolescents (R01 clinical trial required). (PAR-18-428). Retrieved from https://grants.nih.gov/grants/guide/pa-files/PAR-18-428.html.

Drake, R. E., Bond, G. R., Goldman, H. H., Hogan, M. F., & Karakus, M. (2016). Individual placement and support services boost employment for people with serious mental illnesses, but funding is lacking. Health Affairs,35(6), 1098–1105.

Eaton, W. W., Thara, R., Federman, B., Melton, B., & Liang, K.-Y. (1995). Structure and course of positive and negative symptoms in schizophrenia. Archives of General Psychiatry,52(2), 127–134.

Folsom, D. P., Hawthorne, W., Lindamer, L., Gilmer, T., Bailey, A., Golshan, S., et al. (2005). Prevalence and risk factors for homelessness and utilization of mental health services among 10,340 patients with serious mental illness in a large public mental health system. American Journal of Psychiatry,162(2), 370–376.

Friis, S., Melle, I., Johannessen, J. O., Rossberg, J. I., Barder, H. E., Evensen, J. H., et al. (2016). Early predictors of ten-year course in first-episode psychosis. Psychiatric Services (Washington, D. C.),67(4), 438–443. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201400558.

Friis, S., Røssberg, J. I., Evensen, J., Haahr, U., Ten Velden, W. H., Joa, I., et al. (2010). Lessons learned from the TIPS project. Early intervention in psychiatry,4, 2.

Gaite, L., Vázquez-Barquero, J. L., Borra, C., Ballesteros, J., Schene, A., Welcher, B., et al. (2002). Quality of life in patients with schizophrenia in five european countries: The epsilon study. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica,105(4), 283–292.

Guidance for revision of the fy2016-2017 block grant application for the new 10 percent set-aside. (2016). Retrieved from https://www.samhsa.gov/sites/default/files/mhbg-5-percent-set-aside-guidance.pdf

Heinssen, R., Goldstein, A., & Azrin, S. (2014). Evidence-based treatments for first episode psychosis: Components of coordinated specialty care. National Institute of Mental Health.

Horvitz-Lennon, M., Breslau, J., Scharf, D., Doyle, M., Nanda, N., Kusuke, D., et al. (2015). Case study: Early assessment of the mental health block grant set-aside program for addressing first episode psychosis and other early serious mental illness. Retrieved from https://aspe.hhs.gov/system/files/pdf/205071/MHBGsetaside.pdf.

Horvitz-Lennon, M., Donohue, J. M., Domino, M. E., & Normand, S.-L. T. (2009). Improving quality and diffusing best practices: The case of schizophrenia. Health Affairs,28(3), 701–712.

Horvitz-Lennon, M., Predmore, Z. S., Orr, P., Hanson, M., Hillestad, R., Durkin, M., et al. (2018). Simulated long-term outcomes of early use of long-acting injectable antipsychotics in early schizophrenia. Early Intervention in Psychiatry,100, 1540. https://doi.org/10.1111/eip.12770.

Kane, J. M., Kishimoto, T., & Correll, C. U. (2013). Non-adherence to medication in patients with psychotic disorders: Epidemiology, contributing factors and management strategies. World Psychiatry,12(3), 216–226.

Kane, J. M., Robinson, D. G., Schooler, N. R., Mueser, K. T., Penn, D. L., Rosenheck, R. A., et al. (2016). Comprehensive versus usual community care for first-episode psychosis: 2-year outcomes from the nimh raise early treatment program. American Journal of Psychiatry,173(4), 362–372. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2015.15050632.

Kotov, R., Fochtmann, L., Li, K., Tanenberg-Karant, M., Constantino, E. A., Rubinstein, J., et al. (2017). Declining clinical course of psychotic disorders over the two decades following first hospitalization: Evidence from the suffolk county mental health project. American Journal of Psychiatry,174(11), 1064–1074.

Kreyenbuhl, J., Buchanan, R. W., Dickerson, F. B., & Dixon, L. B. (2009). The schizophrenia patient outcomes research team (port): Updated treatment recommendations 2009. Schizophrenia Bulletin,36(1), 94–103.

Lester, H., Birchwood, M., Freemantle, N., Michail, M., & Tait, L. (2009). Redirect: Cluster randomised controlled trial of GP training in first-episode psychosis. British Journal of General Practice,59(563), e183–e190.

Marshall, M., Lewis, S., Lockwood, A., Drake, R., Jones, P., & Croudace, T. (2005). Association between duration of untreated psychosis and outcome in cohorts of first-episode patients: A systematic review. Archives of General Psychiatry,62(9), 975–983.

Melle, I., Joa, I., Larsen, T. K., Haahr, U., Friis, S., Johannesen, J. O., et al. (2012). Shortening the duration of untreated psychosis: Experiences from the TIPS study. Early Intervention in Psychiatry,6, 5.

Mihalopoulos, C., Harris, M., Henry, L., Harrigan, S., & McGorry, P. (2009). Is early intervention in psychosis cost-effective over the long term? Schizophrenia Bulletin,35(5), 909–918. https://doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sbp054.

National Institute of Mental Health. Recovery after an initial schizophrenia episode (RAISE). Retrieved from https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/topics/schizophrenia/raise/index.shtml.

Norman, R. M., Malla, A. K., McLean, T., Voruganti, L. P. N., Cortese, L., McIntosh, E., et al. (2000). The relationship of symptoms and level of functioning in schizophrenia to general wellbeing and the quality of life scale. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica,102(4), 303–309.

Olfson, M., Ascher-Svanum, H., Faries, D. E., & Marcus, S. C. (2011). Predicting psychiatric hospital admission among adults with schizophrenia. Psychiatric Services (Washington, D. C.),62(10), 1138–1145. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.62.10.1138.

Oliver, D., Davies, C., Crossland, G., Lim, S., Gifford, G., McGuire, P., et al. (2018). Can we reduce the duration of untreated psychosis? A systematic review and meta-analysis of controlled interventional studies. Schizophrenia Bulletin,44(6), 1362–1372.

Penttilä, M., Jääskeläinen, E., Hirvonen, N., Isohanni, M., & Miettunen, J. (2014). Duration of untreated psychosis as predictor of long-term outcome in schizophrenia: Systematic review and meta-analysis. The British Journal of Psychiatry,205(2), 88–94.

Perkins, D. O., Gu, H., Boteva, K., & Lieberman, J. A. (2005). Relationship between duration of untreated psychosis and outcome in first-episode schizophrenia: A critical review and meta-analysis. American Journal of Psychiatry,162(10), 1785–1804.

Robinson, D. G., Schooler, N. R., John, M., Correll, C. U., Marcy, P., Addington, J., et al. (2014). Prescription practices in the treatment of first-episode schizophrenia spectrum disorders: Data from the national raise-etp study. American Journal of Psychiatry,172(3), 237–248. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2014.13101355.

Rosenheck, R. A., Estroff, S. E., Sint, K., Lin, H., Mueser, K. T., Robinson, D. G., et al. (2017). Incomes and outcomes: Social security disability benefits in first-episode psychosis. American Journal of Psychiatry,174(9), 886–894.

Rosenheck, R., Leslie, D., Keefe, R., McEvoy, J., Swartz, M., Perkins, D., et al. (2006). Barriers to employment for people with schizophrenia. American Journal of Psychiatry,163(3), 411–417. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.163.3.411.

Rund, B. (2014). Does active psychosis cause neurobiological pathology? A critical review of the neurotoxicity hypothesis. Psychological Medicine,44(08), 1577–1590.

Sarpal, D. K., Robinson, D. G., Fales, C., Lencz, T., Argyelan, M., Karlsgodt, K. H., et al. (2017). Relationship between duration of untreated psychosis and intrinsic corticostriatal connectivity in patients with early phase schizophrenia. Neuropsychopharmacology,42(11), 2214.

Slade, E., & Salkever, D. (2001). Symptom effects on employment in a structural model of mental illness and treatment: Analysis of patients with schizophrenia. Journal of Mental Health Policy and Economics,4(1), 25–34.

Srihari, V. H. (2018). Working toward changing the duration of untreated psychosis (DUP). Schizophrenia Research,193, 39–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2017.07.045.

Stevens, G. L., Dawson, G., & Zummo, J. (2016). Clinical benefits and impact of early use of long-acting injectable antipsychotics for schizophrenia. Early Intervention in Psychiatry,10(5), 365–377.

Subotnik, K. L., Casaus, L. R., Ventura, J., Luo, J. S., Hellemann, G. S., Gretchen-Doorly, D., et al. (2015). Long-acting injectable risperidone for relapse prevention and control of breakthrough symptoms after a recent first episode of schizophrenia. A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry,72(8), 822–829. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.0270.

Taylor, M., & Ng, K. Y. (2013). Should long-acting (depot) antipsychotics be used in early schizophrenia? A systematic review. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry,47(7), 624–630. https://doi.org/10.1177/0004867412470010.

Tiihonen, J., Haukka, J., Taylor, M., Haddad, P. M., Patel, M. X., & Korhonen, P. (2011). A nationwide cohort study of oral and depot antipsychotics after first hospitalization for schizophrenia. American Journal of Psychiatry,168(6), 603–609. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.10081224.

Tsai, J., Stroup, T. S., & Rosenheck, R. A. (2011). Housing arrangements among a national sample of adults with chronic schizophrenia living in the united states: A descriptive study. Journal of Community Psychology,39(1), 76–88. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcop.20418.

Weinberger, D. R., & Harrison, P. (2011). Schizophrenia (3rd ed.). Oxford: Wiley.

Whiteford, H. A., Degenhardt, L., Rehm, J., Baxter, A. J., Ferrari, A. J., Erskine, H. E., et al. (2013). Global burden of disease attributable to mental and substance use disorders: Findings from the global burden of disease study 2010. The Lancet,382(9904), 1575–1586.

Wunderink, L., Nieboer, R. M., Wiersma, D., Sytema, S., & Nienhuis, F. J. (2013). Recovery in remitted first-episode psychosis at 7 years of follow-up of an early dose reduction/discontinuation or maintenance treatment strategy: Long-term follow-up of a 2-year randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry,70(9), 913–920.

Funding

This study was funded by a contract to the RAND Corporation from Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC. The funding agreement ensured the authors’ independence in designing the study, interpreting the data, writing, and publishing the report.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

Drs. Durkin and El Khoury are stockholders of Johnson & Johnson, a pharmaceutical manufacturer. The other authors (MHL, ZP, PO, MH, RH, SM) declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Research Involving Human Participants and/or Animals

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Horvitz-Lennon, M., Predmore, Z., Orr, P. et al. The Predicted Long-Term Benefits of Ensuring Timely Treatment and Medication Adherence in Early Schizophrenia. Adm Policy Ment Health 47, 357–365 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-019-00990-7

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-019-00990-7