Abstract

Whilst there has been previous work focused on the role of technologies in enhancing supply chain risk management and, through such an enhancement, increased competitive advantage, there is a research gap in terms of understanding the links between external institution pressures and internal adoption factors. We use institutional theory (IT) and the resource based view (RBV) of the firm to address this gap, developing a framework showing how a proactive technology-driven approach to supply chain risk management, combining both external with internal factors, can result in competitive advantage. We validate the framework through analysis of quantitative data collected via a survey of 218 firms in the manufacturing and logistics industry sectors in India. We specifically focus on the technologies of track-and-trace (T&T) and big data analytics (BDA). Our findings show that firms investing in T&T/BDA technologies can gain operational benefits in terms of uninterrupted information processing, reduced time disruptions and uninterrupted supply, which in turn gives them competitive advantage. We add further novelty to our study by demonstrating the moderating influences of organisational culture and flexibility on the relationship between the technological capabilities and the operational benefits.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The global COVID-19 pandemic, subjected organizations to risks that were beyond prediction and comprehension (Queiroz et al., 2020). The management of risks and disruptions, resilience, and contingency planning, like in the aftermath of the September 11 terrorist attacks and the 2008 financial crisis once again dominated the focus of supply chain scholarship. Supply chain risk management (SCRM) refers to the process by which businesses take strategic steps to identify, assess, and mitigate risks within their end-to-end supply chain (El Baz & Ruel, 2021). In addition to mitigating threats, which is one side of the risk coin, achieving SCRM (please refer to Appendix A for a full list of acronyms used in the paper) also provides a flip-side, which is to ensure a competitive advantage for the firm by providing a platform to make decisions that exploit opportunities (Narasimhan & Talluri, 2009).

There are diverse causes of supply chain disruptions. In some instances, the financial design of a supply chain can increase its risk of exposure to disruption. For example, a firm that seeks to take advantage of economies of scale in its inbound supply chain, by pursuing a single sourcing strategy concurrently, might suffer from an increased negative impact of supply-side disruptions i.e., supplier defaults (Wagner & Bode, 2008). SCRM’s role is to: “anticipate, identify, classify, and mitigate risks in supply chains. Understanding the intent and the source of disruption is critical for appropriate risk management” (DuHadway et al., 2019, p.179), with those firms with high SCRM capabilities able to operate with less threat exposure and enhanced resilience in the face of market and non-market disruptions.

To enhance their risk management capabilities organizations are turning their attention to the utilization of supply chain technologies (Belhadi et al., 2021). However, decisions to implement novel technologies are not easy to make, especially in highly unstable post pandemic-related conditions of polycrises,Footnote 1 which have heightened the wisdom of the high investments needed for new technology adoption (Jerome et al., 2021). This results in a dilemma for managers when it comes to justifying their SCRM-oriented technological investments (El Baz & Ruel, 2021).

SCRM practices are enhanced through increased visibility in the supply chain (Christopher & Lee, 2004; Nooraie & Mellat Parast, 2015) and modern technologies have been shown to enhance supply chain visibility (Barreto et al., 2017). We posit that a combination of new technologies, specifically Track-and-Trace (T&T) systems and Big Data Analytics (BDA), enhances visibility, eventually leading to proactive decision-making (Aloysius et al., 2018; Mishra et al., 2018; Wamba et al., 2018). T&T systems comprise technologies that help in collecting and sharing data across and beyond the supply chain, thereby increasing the ease with which data is shared. BDA works on the data collected by the T&T systems to arrive at insights that aid decision-making. Ivanov et al. (2019) classify technologies, such as Radio-Frequency Identification (RFID), sensors and Blockchain Technology (BCT) as advanced T&T technologies. RFID has been applied for its T&T capabilities in many scenarios, such as planning and scheduling for mass-customization production (Zhong et al., 2013), detecting counterfeits (Berman, 2008) and ensuring real-time monitoring and traceability (Zeimpekis et al., 2010).

BCT has also been applied to enhance traceability in supply chains by facilitating better information exchange (Agrawal et al., 2021). Thus, we argue that advanced T&T technologies enhance tracking in the supply chain by increasing the quality and quantity of information that is present, captured and shared in the supply chain, thereby increasing its visibility. When these advanced T&T technologies are supported by BDA, we posit there are subsequent increases in operational advantages. For example, it is possible to identify the roots of disruption (Ivanov et al., 2019), or to perform T&T to monitor safety and quality in pharmaceutical supply chains (Chircu et al., 2014). Or to ensure sustainability in operations through reduced carbon emission (Sundarakani et al., 2021). In summary, we propose that SCRM is enhanced through a combination of T&T and BDA technologies.

The current literature provides a lot of potential for research around the development of risk management through the application of technology in the supply chain. There are only a few theoretical studies concerning aspects of technology-driven SCRM in the current literature (van Hoek, 2020). A review study on the application of BCT to supply chains identified a lack of studies from a theoretical perspective and called for more rigorous conceptual and empirical contributions to deepen knowledge and understanding (Wang et al., 2019). Therefore, there is a need for more rigorous data-driven empirical research to advance SCRM knowledge and derive more in-depth insights (Ivanov et al., 2019). With studies that incorporate theoretical grounding, methodological diversity, and empirically supported work (Frizzo-Barker et al., 2020). There also exists a need for more in-depth analysis of the role of risk analytics in the supply chain. Moreover, there is a need for greater understanding of risks in a supply chain supported by T&T systems like RFID, sensors, and BCT (Ivanov & Dolgui, 2021). In Sect. 2 we specifically focus on the research contribution of our work to the field of technology-enabled SCRM.

With the unprecedented level of ongoing and rapidly changing supply chain disruption caused by the pandemic and post-pandemic conditions, there is a further need to identify and resolve heightened and new forms of “demand” and “supply-side” generated risks (Spieske & Birkel, 2021). The literature also suggests that the integration of advanced technologies in supply chains, in order to guard and protect against disruptions, is a topic worthy of further research (Belhadi et al., 2021). Also, a recent study has shown that studies of risk management during the pandemic have focused mainly on reactive models than proactive ones and have identified this as a major gap in existing literature (Rinaldi et al., 2022).

We respond to these various agendas for research in our study, firstly, through the following two research questions: RQ1: How do T&T-BDA systems support the organization to achieve competitive advantage through SCRM? RQ2: How can a T&T-BDA system be adopted by a firm and what are the critical external and internal factors that drive the adoption of such a system? In the past, there have been studies that suggest ways in which technologies, such as BDA, offer a competitive advantage (Schilke, 2014). We contribute to knowledge by considering how the relationship between T&T-BDA capabilities and competitive advantage are mediated by the capabilities of uninterrupted information processing, reduced time disruption and uninterrupted supply.

A final area of focus for our study relates to the concepts of culture and flexibility. Empirical studies on the role of new technologies in managing supply chains highlight two factors that moderate relationships, namely: organizational culture and organizational flexibility (Dubey et al., 2019a, 2019b, 2019c). These factors are important in ensuring an organization has the right culture to realize the benefits of SCRM-related technologies. It is also important to know quickly that the organization can undertake the necessary structural changes or rapid resource deployments to offset any disruptions. This gives rise to the third and final research question, which is: RQ3: What is the role played by organizational culture and organizational flexibility in building and realizing the benefits of an advanced T&T-BDA system?

Our paper is structured as follows. In the next section, we first articulate our research contribution. Then in Sect. 3 we present the two key theories underpinning this study underpinning our theoretical framework. In Sect. 4 we set out our research design, outlining our strategy for sampling managers working in SCM in the manufacturing and logistics sectors in India using a survey-based measurement instrument. We then in Sect. 5 present our data analysis and inferences, firstly addressing the issue of validity in our data and secondly, our partial least squares-structured equation model, demonstrating its high level of explanatory power. Next, in Sect. 6 we present our results and accompanying discussion, which leads to our theoretical contribution. We then highlight the managerial implications of our work and set out the limitations of our study and provide some future research directions. Lastly, we set out our conclusions in Sect. 7.

2 Research contribution

There is a growing body of recent work providing a theoretical foundation for our unit of analysis, which is the enhancement of supply chain risk management through the adoption of track and trace and big data analytics technologies. For instance, there is research looking at artificial intelligence-driven risk management for enhancing supply chain agility (Belhadi et al., 2021; Wong et al., 2022), the role of blockchain in enabling viable supply chain (vendor) management of inventory (Lotfi et al., 2022), effective supply chain risk management capabilities (Ghosh & Sar, 2022), the relationship between team skills and competencies, risk management and supply chain performance (Sahib et al., 2022), and the factors and strategies for organizational building information modelling (BIM) capabilities (Rajabi et al., 2022).

Although these works have a similar focus on technology contributing to risk management capabilities and competitive advantage, we uniquely position our work on testing the links between external institutional pressures and internal adoption factors. For instance, thee first part of our framework (left hand side of the diagram) specifically focuses on measuring the strength and significance of the relationships between three pressures identified in institutional theory: “coercive”, “normative” and “mimetic” and three types of firm resources identified in the RBV: “information technology infrastructure”, “managerial skills” and “technical expertise”.

We then go on to test the link between internal big data capabilities through the mediating factor of organizational flexibility on supply chain risk management (i.e., uninterrupted information processing, reduced time disruption and uninterrupted supply) and competitive advantage. As previously mentioned, this paper is therefore important as it is the first of its kind (to our knowledge) to focus not solely internally on organizational factors but also to combine external with internal factors as a driver of adoption. Also, we are unique in our work focusing on tracing the mediating effects of organizational resources and T and T and BDA capabilities on SCRM and competitive advantage.

3 Underpinning theories

3.1 Resource-based view (RBV)

RBV is built on the theory that firms possess various resources, and by using these resources, they can achieve a competitive advantage (Barney, 1991). It was the VRIO framework, which implies that valuable (V), rare (R), imitable (I) and the organization (O) of resources helps a firm achieve maximum potential (Akter et al., 2020). Resources can be classified either as tangible or intangible resources (Größler & Grübner, 2006). They differ from capabilities in that: “whilst resources refer to tangible and intangible assets, capabilities form a part of the firm’s resources, which are both non-transferable and also aid in improving the productivity of the resources employed” (Makadok, 1999, p. 935). Thus, RBV emphasizes that a firm’s productivity will depend on the firm’s capabilities to manage its unique resources (Morgan et al., 2009). There are two types of resources in terms of building BDA capabilities: tangible resources i.e. data, infrastructure, etc.; and intangible resources, i.e. human resources, managerial and technical skills (Gupta & George, 2016). Whilst these two types of resources are necessary, they are not sufficient to guarantee a competitive advantage (Gunasekaran et al., 2017). There is also a moderating role played by managers in applying their skills to support and build the quality and quantity of firm resources (Chadwick et al., 2015; Sirmon et al., 2007).

Harnessing the potential of new technology requires close collaboration between the business team and technical teams, which in turn needs to be driven by the firm’s senior management team (Barlette & Baillette, 2020). Hence, the technical expertise of managers is not critical; rather, in addition to allocating resources, top management must be actively involved in the establishment of favourable work procedures, organizational routines and decision-making protocols (Hermano & Martín-Cruz, 2016). Thus, in our study we consider three vital resources for driving the adoption of T&T-BDA capabilities of the firm: (1) the tangible resources, which include physical infrastructure, data, (2) managerial skills and (3) technical expertise.

3.2 Institutional theory (IT)

IT is built on the understanding that: “… firms operate within a social framework of norms, values, and taken-for-granted assumptions about what constitutes appropriate or acceptable economic behaviour” (Oliver, 1997). IT suggests that the behaviour of humans extends to social justification and social obligation rather than only economic optimization (Dimaggio, 1990). Hence, IT has two associated perspectives, namely: sociological and economic (Turkulainen et al., 2017). The economic perspective proposes that organizations try to mimic the environment they operate in by modelling themselves to the environment, with the ulterior motive of seeking profit. The sociological perspective suggests that organizations model themselves according to the environment, to gain legitimacy; acting desirably, properly, and appropriately, based on the context. The majority of previous studies related to the implementation of technology in operations management have primarily focussed on the sociological perspective (Chakuu et al., 2020; Hew et al., 2020).

When the sociological perspective is perceived as more important than the economic one, it can be said that the need for a firm to establish legitimacy is comparatively high. Legitimacy is established through the acceptance of the norms, rules and regulations of the operating environment, and subsequently embedding these in the decision-making process of the firm (Glover et al., 2014). Hence, the firm becomes like the other firms in the environment it operates in, giving rise to institutional isomorphism. This isomorphism can be divided into three types: coercive, normative and mimetic (DiMaggio & Powell, 1983). These types of isomorphism are further discussed in detail in Sect. 4.4.1 of our paper, in the context of their hypothesised relationships with the resources of IT infrastructure, managerial skills and technical expertise.

4 Theoretical model and hypotheses development

4.1 Advanced T&T-BDA capabilities

Whilst the key role of a T&T system is to ensure transparency and help in tracking, thus leading to greater visibility, the role of BDA is in drawing meaningful insights from huge amounts of data (Özemre & Kabadurmus, 2020). A study regarding the combination of RFID and GPS, as a novel T&T system, highlights the role this system plays in the routing and minimization of backlogs and missing cargo (He et al., 2009). RFID is a key technology in detecting and avoiding counterfeiting in a supply chain (Choi et al., 2015; Wazid et al., 2017). An innovative solution developed with the help of geo-fencing algorithms and RFID demonstrates how this system can monitor and manage deliveries in logistics with minimal human intervention (Oliveira et al., 2015). When it comes to inventory management, there is a past study showing how RFID helps strike the balance between pipeline stock and lateral transhipments to improve system performance and reduce costs (Yang et al., 2013). Hence, it can be seen that advanced T&T systems enhance shared data value and create a platform for risk mitigation by allowing for demand-oriented distribution flexibility (Doetzer & Pflaum, 2021).

A fairly recent study also highlights that firms using RFID for more than a year may start to explore more advanced T&T systems such as BCT (Choudhury et al., 2021). In an era of rapid growth, BCT, a novel technology that falls under the umbrella of T&T systems, is used on socially oriented crowdsourcing platforms, as it offers increased transparency, reliability and trustworthiness (Nguyen et al., 2021). Although the purpose of BCT remains the same, that is to enhance access to data, it addresses previous shortcomings of T & T systems, such as data manipulation and a single point of failure (Sunny et al., 2020). BCT has also started to actively revolutionize supply chains, observed through the application of smart contracts that address various manufacturing and supply chain problems. Furthermore, it is argued that future competition will not be between supply chains, but rather be between analytics algorithms embedded in the supply chain (Dolgui et al., 2020). When BCT is applied to a supply chain, traceability within it increases, and since a blockchain is secure and cannot be tampered with, it leads to increased transparency and reduced counterfeiting of goods and services (Wamba et al., 2020).

Whilst RFID is used to increase the tracking and visibility in a supply chain to control inventory pipelines (Holweg et al., 2005), it can improve information accuracy and management through real-time information (Sarac et al., 2010). It can also save labour costs and improve supply coordination (Lee & Özer, 2007) and provide a competitive advantage (Tajima, 2007). BCT enhances trust between the various stakeholders in the supply chain as it is tamper-proof and uniform across the entire supply chain (Kamble et al., 2020). This trust helps in the increased sharing of data between different stakeholders (Wang et al., 2021). All the T&T systems incorporated by a firm are predicated on the core principle of data being generated from the various stages and processes in the supply chain, which can then be used to improve tracking and visibility.

4.2 Supply chain risk management (SCRM)

Risk can be defined as: “the chance, in quantitative terms, of a defined hazard occurring. It, therefore, combines a probabilistic measure of the occurrence of the primary event(s) with a measure of the consequences of that/those event(s)” (Tang, 2006, p. 451). With the business environment being extremely dynamic, turbulent, and unpredictable, organizations must: “… consciously develop the agility to provide superior value as well as to manage disruption risks and ensure uninterrupted service to customers” (Braunscheidel & Suresh, 2009, p. 119).

The early twenty-first century witnessed the growth of inter-organization networking, which further increased large companies’ exposure to risk, especially when these companies partnered with smaller organizations in their supply chain (Finch, 2004). Outsourced manufacturing, which was a practice to gain cost advantage and subsequently higher market share, came with increased vulnerabilities to uncertain economic cycles, changing consumer demands, and natural/man-made disasters (Tang, 2006). With the environment being increasingly challenging, as well as competitive, manufacturers are seeking ways to be more cost-effective, whilst maintaining their profitability. One strategy is to make their supply chains leaner, but this strategy is giving rise to supply chain vulnerabilities (Svensson, 2000). With the globalization of business, the complexity and competitiveness of supply chains, and the possibility of disruptions have increased (Hosseini & Ivanov, 2019; Liu & Nagurney, 2013). Therefore, there is a call for increased risk management in supply chains.

With the birth of Industry 4.0 and advanced technologies, studies have focused on understanding the impact of these digital technologies on SCRM (Ivanov et al., 2017; Niesen et al., 2016; Papadopoulos et al., 2017). Three kinds of risks are identified that require mitigation, with the help of an integrated T&T-BDA system, namely: (1) information disruption risk (IDR), (2) supply risk (SR), and (3) time risk (TR) (Ivanov et al., 2019). We return to these kinds of risks when developing our hypotheses in Sect. 4.4 below.

4.3 Competitive advantage (CA)

Although CA is defined and interpreted differently by various scholars, a recent study described CA as an: “above industry-average manifested exploitation of market opportunities and neutralization of competitive threats” (Sigalas, 2015, p. 2004). Firms obtain a sustained CA by implementing strategies that: “… exploit their internal strengths, through responding to environmental opportunities while neutralizing external threats and avoiding internal weakness”; with CA derived by creating and combining: “bundles of strategic resources or capabilities” (Barney, 1991, p. 99). The CA of an organization rests on distinctive processes and is shaped by the firm’s specific asset positions (Teece et al., 1997). It comes from possessing relevant capability differentials, in the form of intangible resources such as patents, reputation and know-how (Hall, 1992). Organizations need to make their business processes hard-to-imitate strategic capabilities, to differentiate themselves from their competitors in the eyes of the customer (Stalk et al., 1992). Superior firm performance, compared with competitors, is a key for CA (Schilke, 2014). Thus, to gain CA, firms need to ensure their combinations of resources are unique and hard to mimic, and, hence, used to drive superior performance of the firm.

4.4 Hypothesis development

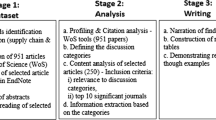

Prior studies in the literature show that SCRM needs to be implemented across all firms in a supply chain, to deliver maximum benefits. To achieve this level of integration, the sharing of data between the stakeholders is important. This sharing can be driven by T&T systems. Also, with the volume, variety, velocity and variability of the data that is present in an organisation, BDA can be used to offer critical insights (Sivarajah et al., 2017). In our study, we propose that a combination of these two technologies (T&T systems and BDA) supports SCRM. The theoretical model is shown in Fig. 1 and we elaborate on the elements of the framework and develop our hypotheses to test the various relationships between the different constructs.

4.4.1 Institutional pressures and firm’s resources

The first part of the framework focuses on the strength and significance of the relationships between the three pressures identified in institutional theory: coercive, normative, and mimetic and three types of firm resources identified in the RBV: information technology infrastructure (ITI), managerial skills (MS) and technical expertise (TS). Coercive pressure (CP) arises from the policies, laws, rules and regulations laid down by the government agency that operates in the same environment as the firm and they seek legal compliance (Bag et al., 2018). CP plays an important role when it comes to working with the data of individuals, as it dictates the rules regarding safe and fair usage. This comes from the ethical dilemma that exists between the benefits of data and the dark side of opaque algorithms that are run on data (Dwivedi et al., 2021). To address this dilemma, various governmental agencies have restrictions when it comes to the type and amount of data collected (Boyd & Crawford, 2012). Thus, CP plays a role when it comes to the adoption of new technologies. Intervention from the government, in the form of protection schemes and initiatives, is important for all technology projects (Bag et al., 2021). Thus, when a firm decides to adopt an innovation in its operations, it will try to evaluate the potential costs associated with the external forces against the benefits it offers (Liu et al., 2010). CP also has a positive impact on top management beliefs and participation, thereby impacting managerial skills (Shibin et al., 2020). Hence, we formulate the following hypotheses:

-

H1a: CP has a significant positive impact on the level of ITI of an organization.

-

H1b: CP has a significant positive impact on MS.

-

H1c: CP has a significant positive impact on TE.

Normative pressure (NP) is the influence that comes from other stakeholders in the supply chain, such as suppliers, customers, environmental agencies and society and its beliefs and values (Lutfi, 2020). With many managers and senior-level executives coming from a technology background, there may be pressure on the firm to adopt advanced technologies (Dubey et al., 2019a, 2019b, 2019c). Having a strong technology infrastructure is important for all the stakeholders in the supply chain to connect together (Telukdarie et al., 2018). A combination of a lack of infrastructure and a willingness of suppliers and customers to jointly share information will lead to NP on the firm. If this is not addressed, there may be a loss of relationship between the firm and its suppliers and customers. Also, in a supply chain, all the stakeholders of a firm would prefer to do business with a firm whose workforce is skilled (Bag et al., 2021). Thus, we can see that NP potentially influences resources positively, and hence, the following hypotheses are formulated:

-

H2a: NP has a significant positive impact on the level of ITI of an organization.

-

H2b: NP has a significant positive impact on MS.

-

H2c: NP has a significant positive impact on TE.

Mimetic pressure (MP) refers to the desire to look or behave like others by copying their behaviours and it occurs when competitor firms in the external environment are successful (Stanger et al., 2013). MP manifests when the firm does not have sufficient capacity or information to solve a problem and, hence, it looks at other firms in the same or similar environment that have already solved the problem and become successful (Krell et al., 2016). Firms can look at other competitors adopting novel technologies and the benefits they are realizing because of it. Activities in a competing firm can drive the focal firm to train its workforce in technological advancements and this training is important to realize the full benefits of the implemented technology (Bag et al., 2021; Dhamija & Bag, 2020). MP also influences the support of management when it comes to technological initiatives (Chaubey & Sahoo, 2021). Hence, we test the following hypotheses concerning MP:

-

H3a: MP has a significant positive impact on the level of ITI of an organization.

-

H3b: MP has a significant positive impact on MS.

-

H3c: MP has a significant positive impact on TE.

4.4.2 Firm’s resources and T&T-BDA capabilities (TTB)

In this part of the framework, we focus on the relationships between a firm’s ITI, MS and TE resources and its T&T-BDA capabilities, in the form of RFID/GPS/BCT, which we abbreviate TTB in the framework. The firm’s resource of ITI can be classified into two distinct components: technical ITI and human ITI (Byrd & Turner, 2000). We look at ITI from the technical point of view, which is, the hardware, software and networks possessed by the firm. A firm with good technological infrastructure, when coupled with good technical skills, will be able to manage its operations more efficiently (Wade & Hulland, 2004). The presence of an ITI helps create a higher-order capability of supply chain process integration (Rai et al., 2006) and it promotes higher organizational agility. The use of RFID and GPS is long-standing; thus firms have established infrastructure in place and ready for it. Although there are many potential benefits of BCT, its infrastructure is still in its infancy. Investments in ITI could lead to increased innovations in the organization (Rajan et al., 2020). The presence of a good BDA infrastructure is also required for “… decision-making, for the coordination, control and analysis of processes, and the visualization of information” (Rialti et al., 2019, p. 149). When developing BDA capabilities, it is posited that the presence of good infrastructure will help support the technology in place to improve firm performance (Wamba et al., 2017). Hence, we propose the following hypothesis:

-

H4a: ITI has a significant positive impact on TTB.

Managers are responsible for the integration of imported external knowledge with internal knowledge (Mitchell, 2006); with MS fulfilling an important role in the coordination, of multifaceted activities to adopt and use technology in a firm (Bharadwaj, 2000). Also, when big data managers and other functional managers develop good understanding and trust between them, it leads to the development of capabilities and skills, which may be difficult to imitate by other organizations (Dubey et al., 2019a, 2019b, 2019c). Further studies show the following: how MS helps drive the integration of technology with business processes (Ooi et al., 2018); how support from management helps in the successful implementation of Industry 4.0 (Sony & Naik, 2019); how management helps by framing policies and allocating resources to support the digitization process (Ghobakhloo, 2020); how managers play an important role in the initiation, experimentation, and implementation phases of RFID (Matta et al., 2012); and, finally, how managers have a key role to play in the adoption of BCT (Orji et al., 2020). Therefore, we propose the following hypothesis:

-

H4b: MS has a significant positive impact on TTB.

Technical Expertise (TE) refers to the knowledge and skills that a firm or a team possesses regarding the technicalities of a product or service, which is vital for the adoption of novel technologies in a firm (Lin & Lee, 2005). An example of TE is how to use information extracted from the TTB-BDA system to arrive at insights that could be beneficial to the firm (Dubey, et al., 2019a, 2019b, 2019c). Acquiring TE is important for technology planning and integration (Sumner, 2000). A lack of TE has emerged as a major barrier in many attempted adoptions of BCT (Kurpjuweit et al., 2021; Pólvora et al., 2020), RFID (Lau & Sirichoti, 2012; Ngai et al., 2008; Wamba et al., 2008) and BDA (Akter et al., 2016; Dremel et al., 2020). To add to this body of knowledge, we explore the relationship between TE and TTB through the following hypothesis:

-

H4c: TE has a significant positive impact on TTB.

4.4.3 T&T-BDA capabilities (TTB) and supply chain risk management (SCRM)

The next part of our framework explores the relationship between T&T-BDA capabilities and SCRM, where SCRM is made up of three constructs: undisrupted information processing (UIP), reduced time disruption (RTD) and undisrupted supply (US). T&T systems help in collecting data that is non-tampered and spread across various systems, such as sales, manufacturing, and logistics. BDA helps in integrating these different sources of data for further analysis and use (Ivanov et al., 2019). These technologies play an important part in helping manage the risks in a supply chain. We posit that a combination of these technologies can benefit a firm through each of the three elements of SCRM: UIP, RTD and US—as suggested by Durowoju et al. (2012). An information disruption risk occurs when there is a disruption in the flow of information between the stakeholders in the supply chain, thus putting the operations of the firm at stake. Such disruption can be caused by infrastructure complications, distorted information or information leaks (Truong Quang & Hara, 2018).

The value of information sharing between the members of a supply chain is often quite high (Lee et al., 2000) and various studies show that sharing data between various entities supports SCRM (Ho et al., 2015; Tang, 2006). This sharing of information can be further driven by the presence of technologies such as RFID and GPS, which can collect a greater amount of data with autonomous processes. However, this information sharing may be constricted due to data breaches (Ali et al., 2018). Therefore, to increase information sharing, along with ensuring security and transparency, BCT can help by increasing trust and information sharing capabilities amongst the supply chain members, by providing robust information sharing infrastructure (Saberi et al., 2019; Treiblmaier, 2018). Thus, the presence of a system with advanced T&T technology and BDA promotes UIP.

Time risk (TR) occurs due to a delay in supply activities, which can lead to risks related to information, operations, demand and SC performance (Truong Quang & Hara, 2018). Risks related to time lead to dissatisfaction amongst all the parties in a supply chain (Sambasivan & Soon, 2007). Delays in critical activities may lead to disputes amongst the parties (Aibinu & Jagboro, 2002). For instance, delayed payments will cause dissatisfaction with suppliers of the firm and deviations concerning lead time for procurement may lead to stock-out risks (Glock & Ries, 2013; Thomas & Tyworth, 2006). Such disruptions may lead to the firm not being able to cater to demand and, thus, losing market share. With an integrated system, which our framework presents, there can be a potential reduction in TR, due to better supply chain visibility, thus enabling real-time tracking of all activities during normal and deviated course of operations, thereby aiding the achievement of an RTD.

Supply risks (SR) occur when suppliers are not able to deliver the materials needed for the firm’s operations, which can arise due to causes such as: “… supplier bankruptcy, price fluctuations, unstable quality and quantity of inputs” (Truong Quang & Hara, 2018, p. 1369). Firms typically outsource activities which fall outside their core competencies, to gain cost advantage and this has led to a greater dependence on suppliers, thus increasing SR. This has a potentially significant negative impact on the firm, as they have less control over production and delivery processes (Silbermayr & Minner, 2014; Tsai, 2016). The implementation of RFID in a supply chain can lead to better vendor-managed inventories (Gunasekaran & Ngai, 2005). Whilst the implementation of BCT may reduce the number of the parties in the supply chain who are affected by disruptions (Lohmer et al., 2020) Finally, the implementation of BDA may help with supply chain risk analysis (Choi et al., 2018) and supplier evaluation (Shang et al., 2017). Thus, a combination of BDA and T&T will aid US for a firm.

Thus, based on the above arguments, we propose the following three hypotheses to link TTB and SCRM:

-

H5a: TTB has a significant positive impact on UIP.

-

H5b: TTB has a significant positive impact on RTD.

-

H5c: TTB has a significant positive impact on US.

4.4.4 Supply chain risk management (SCRM) and competitive advantage (CA)

Next, our framework presents proposed relationships between the constructs of SCRM and competitive advantage (CA). Organizations around the globe have understood that proper SCRM through: “a systematic management of potential incidences, e.g. supplier failures and unexpected demand changes” can lead to CA (Oehmen et al., 2009, p. 343). Appropriate risk management practices have been seen to reduce the uncertainties that exist during the early phases of the purchasing process, thereby offering a CA to the organization (Leopoulos & Kirytopoulos, 2004). A study by Rangel et al. (2015) highlighted the importance of classification of risks, including supply risk and information processing risk, into various categories, to gain a better understanding of how to handle them, to gain CA (Rangel et al., 2015). Proactive SCRM, in addition to offering cost advantage, offers CA as well (Kırılmaz & Erol, 2017). Thus, it is seen that the capability of firms to manage risks that arise in a supply chain leads to a firm gaining CA concerning the competitors (Singh & Singh, 2019). Hence, we derive the following hypotheses:

-

H6a: UIP has a significant positive impact on CA.

-

H6b: RTD has a significant positive impact on CA.

-

H6c: US has a significant positive impact on CA.

4.4.5 Moderating role of organizational culture (OC) and organizational flexibility (OF)

Drawing from prior literature, our framework proposes a moderating role for organisational culture (OC) and organizational flexibility (OF). OC is conceived as values, beliefs and norms which are shared by its members and which are reflected in organizational practices and goals (Hofstede et al., 1990; Khazanchi et al., 2007). OC plays an important role when it comes to the softer aspects of the organization and its employees, such as motivation, knowledge transfer, teamwork, attitudes and leadership (Marcoulides & Heck, 1993; Nam Nguyen & Mohamed, 2011; Yong & Pheng, 2008; Zu et al., 2010). OC also helps in shaping organizational strategies (Dubey et al., 2017) and it plays a major role in various organizational initiatives, such as the implementation of lean production (Hardcopf et al., 2021), driving innovation (Naranjo‐Valencia et al., 2011), effective knowledge management (Pérez López et al., 2004) and facilitating learning mechanisms (Martin & Matlay, 2003).

In terms of big data, whilst there may be a great deal of data present with a firm, there must be a mechanism and a culture embedded in the firm, to use this data to gain insights to drive value (Dutta & Bose, 2015). Such culture promotes the making of decisions based on data rather than on gut feeling (McAfee et al., 2012). It impacts the managers’ ability to process information and to rationalize and exercise discretion in their decision-making processes (Liu et al., 2010). OC is identified in prior studies as a major challenge to the adoption of big data, with calls for a shift or a change in OC, to realize the benefits of BDA (Frisk & Bannister, 2017; Shamim et al., 2019; Troilo et al., 2017). Hence, we propose the following hypotheses:

-

H7a: OC has a significant positive moderating effect on the path connecting ITI and TTB.

-

H7b: OC has a significant positive moderating effect on the path connecting MS and TTB.

-

H7c: OC has a significant positive moderating effect on the path connecting TE and TTB.

In competitive environments, firms must take decisions to adapt to change, and for every competitive-driven change, there must be an accompanying managerial capability and firm response (Volberda, 1996). This is known as OF, which is an imperative in increasingly complex and volatile environments (Schreyögg & Sydow, 2010).

In an SCM context, OF refers to the ability of the managers to reconfigure the supply chains in as fast and as efficient a manner as possible to adapt to changing demand and supply market conditions (Srinivasan & Swink, 2018). Flexible IT systems increase OF and hence provide a competitive advantage (Byrd & Turner, 2001). For example, the application of an enterprise resource planning (ERP) system can increase OF and the organisational efficiency of the firm (Newell et al., 2003). The presence of high OF is accompanied by a reduction in supply chain risks when there is information sharing in the supply chain (Rajaguru & Matanda, 2013); a presence that we posit is provided with the help of T&T technologies. Other studies corroborate the importance OF plays in achieving the benefits realised through the introduction of advanced technologies (Dubey et al.,; Liu et al., 2009). Thus, we suggest that capabilities offered through an integrated system of T&T technologies and BDA are more impactful in the presence of flexibility, which leads to our final set of hypotheses:

-

H8a: OF has a significant positive moderating effect on the path connecting TTB and UIP.

-

H8b: OF has a significant positive moderating effect on the path connecting TTB and RTD.

-

H8c: OF has a significant positive moderating effect on the path connecting TTB and US.

5 Research design

5.1 Sampling strategy and collection of data

The target audience for our survey-based measuring instrument were managers in their respective organizations who could evaluate and make decisions regarding technology implementation. The sampling strategy was to target only those managers who have implemented technology and participated in technological investment decision-making, so that they were fully aware of all the challenges and benefits. Our survey does not classify respondents based on the designation, as the titles given as designation vary greatly across organizations and are very organization-specific. Rather, the total years of experience with implementing or investing in technology were captured instead. We focused on managers working for firms in the manufacturing and logistics sectors in India, which are leading contributors to the country’s gross domestic product (GDP). With their marketspace becoming more competitive, it is imperative for firms belonging to these sectors to implement risk management strategies. A total of 397 firms from the sectors were chosen from across India, with a ceiling of 20 firms from any one single state in the country.

In stage one, to test the correctness and completeness of the survey, a pilot questionnaire was sent to 25 firms situated across three states in India. 23 firms responded during this initial stage. The questionnaire was reframed and verified by five academicians.

For the second stage, approximately 20 firms were chosen across 21 states in India. These firms were of varying sizes based on their business and turnover. The survey was conducted across various states in India since the political, economic, and cultural factors that influence organization behaviors vary from state to state. The respondents for this survey were contacted through professional networking sites. Survey was run by converting the questionnaire to an online form.

The final questionnaire was therefore sent to the remaining 372 firms and to the two firms which did not respond in the pilot stage. The data collection period for the second stage was four weeks. A reminder was sent out at the beginning of the second and the third week. By the end of the fourth week, a total of 218 usable responses were received, giving a response rate of 54.91%, which is an acceptable value for empirical studies of this nature. The profiles of all the respondents of the firms who participated in our survey are shown in Appendix B.

5.2 Instrument development

Our survey measuring instrument uses a five-point Likert scale. This scale has a rating from 1 to 5, where each rating signifies a degree of agreement towards a statement. The values in the scale are: 1 = “Strongly Disagree”; 2 = “Disagree”; 3 = “Neutral”; 4 = “Agree”; 5 = “Strongly Agree”. This scale has been widely used in many studies in the field of business management and operations management in the past (Al-Abdallah & Al-Salim, 2021; Asante et al., 2018; Joshi et al., 2019).

The validity and suitability of this type of scale have been proven by the vast amount of supporting literature using this scaling technique. The constructs used for our survey were obtained from a combination of past empirical and exploratory studies, shown in Appendix C. We used two control variables: (1) the industry the firm belongs to, and (2) the annual turnover of the firm (Donbesuur et al., 2020; Dubey et al., 2020; Srinivasan & Swink, 2018). These control variables provide information about the role they play in achieving competitive advantage through SCRM.

5.3 Response biases and endogeneity tests

A non-response bias occurs when the nature and quality of the responses of the early respondents vary significantly from that of the later respondents (Lambert & Harrington, 1990). It is important to test for this bias irrespective of the response rate (Dubey et al., 2015). We did this by splitting the timeframe into two halves, that is, the first two weeks as the initial phase, when there were 97 responses and the final two weeks as the second phase when there were 121 responses (Dubey & Ali, 2015; Dubey et al., 2016). To perform the non-response bias test, GNU PSPP was used. There were two tests performed. The first was the one-way ANOVA, to test for the homogeneity of variance (Bag et al., 2021). When the p-value is greater than 0.05 for all the constructs non-response bias is absent. The second test to confirm the above finding for all the variables was the standard t-test (Dubey et al., 2019a, 2019b, 2019c). All p values were greater than 0.05, thus confirming that non-response bias is not an issue.

Common Method Bias (CMB) occurs when respondents take part in surveys under the influence of factors such as social desirability, consistency motif and mood state (Podsakoff et al., 2003). In addition to the survey being designed in a way to reduce the effect of CMB, further statistical tests were conducted to study the effect of CMB on the data. The first test performed was Harman’s one-factor test (Wei et al., 2011). This was done by performing a confirmatory factor analysis of all the items on a single factor to examine the fit indices. This test showed that the single factor has a variance of 19.3%, which indicates an absence of CMB in our data. This test was run again using factor analysis in GNU PSPP, which showed the same cumulative variance percentage for the single factor. The next test carried out was the evaluation of full collinearity VIF, to check if the value is below 3.3 and, hence, to confirm the absence of CMB (Bag et al., 2021; Kock & Lynn, 2012). The hypothesized model showed an average full collinearity VIF of 1.576, which confirms the absence of CMB. Therefore, based on the above, we conclude there is an absence of CMB in our study.

Endogeneity refers to the situation where the exogenous and endogenous elements in a hypothesized model are wrongly specified (Guide & Ketokivi, 2015). Our study used the nonlinear bivariate causality direction ratio (NLBCDR) to test this, with the value of NLBDCR having to be greater than 0.7 for endogeneity to be absent. The hypothesized model of our study shows an NLBCDR value of 0.808, which implies that endogeneity is absent. Further model indices are shown in Appendix D.

6 Data analysis and inferences

We use Structural Equation Modelling (SEM) as the main tool to study the relationship between the entities. To perform the SEM, we used Warp PLS 7.0, a variance-based SEM, or the Partial Least Squares (PLS) method, to test the hypothesized relationships (Kock, 2019). PLS doesn’t need data that is normally distributed and hence traditional parametric-based techniques for significance tests are not required (Dubey et al., 2020). PLS uses the bootstrapping technique, where a large number of re-samples are drawn from the original sample, with replacement, to estimate the model parameters (Henseler et al., 2016). The flexibility of using non-normally distributed data and a comparatively high statistical power help in better and stronger theory-building studies, enabling predictions regarding critical success drivers (Hair et al., 2011, 2014).

Also, it has been shown that PLS-SEM is a promising tool to estimate a complex and hierarchical model, especially when the primary objective is prediction, and that PLS-SEM: “is a modest and realistic technique to establish rigor in complex modelling” (Akter et al., 2017, p. 1). Hence, PLS-SEM focuses on the interplay between prediction and theory testing (Hair et al., 2019). Our investigation focuses on predicting the relationship that T&T-BDA capabilities and competitive advantage have together, with SCRM playing a mediating role between them, and hence PLS-SEM is chosen as the modelling technique.

6.1 Measurement model

Before running SEM on the hypothesized model, three validity and reliability checks were performed: composite reliability, convergent validity and discriminant validity (Kamble et al., 2019). To demonstrate composite reliability and convergent validity, the factor loadings need to have values greater than 0.5 and be within acceptable limits, the composite reliability of each construct must be greater than 0.7, and the average variance extracted (AVE) for each construct must be greater than 0.5 (Motammari et al., 2020). First, we checked the factor loadings, with the results shown in Table 1. It can be seen that the factor loading for two items, MS-2 and UIP-3, is less than 0.5. Hence, these items were dropped from further analysis, due to their low factor loadings. Post item removal, the values of Cronbach’s Alpha, composite reliability and AVE were obtained.

To demonstrate divergent validity, which is the extent to which the constructs in a study differ from each other, the square root of the AVE of the construct selected must be greater than the correlation between the selected constructs and all the other constructs under study (Bag et al., 2021; Kamble et al., 2019). The results of the discriminant validity test are shown in Table 2, which shows confirmation of divergent validity.

Thus, with the outputs from the above tests and the good model fit parameters, shown in Appendix C, we conclude that our model is reliable, free from biases and suitable for further analyses.

6.2 PLS-SEM results

The output of the SEM model is shown in Fig. 2 and an overview of the structural estimates of the hypotheses is shown in Table 3. We considered all the hypotheses yielding a p-value lesser than 0.1 as significant and, based on previous studies (Malhotra et al., 2008; Song et al., 2009), we divided the significant hypotheses into three groups, which are: p < 0.01 (***), p < 0.05 (**) and p < 0.1 (*). Hypotheses with a p-value greater than 0.01 are marked as ‘†’.

We further tested the explanatory power of the model. This is done using the R2 value for the constructs. A value of 0.67, 0.33 and 0.19 is considered substantial, moderate and weak respectively (Peng & Lai, 2012). Next, we examined the value of f2 using the Cohen f2 formula. A value greater than 0.35, 0.15 and 0.02 is considered as large, medium and small respectively (Cohen, 1992). Finally, we examined the value of Q2, which is a measure of a model’s prediction ability. A value greater than 0 implies that the model has predictive relevance (Peng & Lai, 2012). The results from these tests are given in Table 4.

With the help of Table 4, we see that the value of Q2 is greater than 0. Hence the model is deemed to have acceptable predictive relevance. We also see that the R2 values for the endogenous constructs have good explanatory power.

7 Results and discussions

The motivation for our study stems from research which highlights a rising need for theory-driven empirical studies investigating the impact of external pressure and internal application of novel technologies to enhance the SCRM capability of a firm. We have used the resource-based view (RBV) and institutional theory (IT) to ground our study and respond to this need. We have integrated IT with RBV to explain proactive technology-driven SCRM. The inferences made from the analysis of the survey data, through PLS-SEM, offer insights we discuss in this section. A summary of the hypothesis tests and their comparison with the expected relationship, based on the theories, is presented in Table 5.

Firstly, our analysis CP has a significant impact on the ITI of the organization, thus implying that governmental and regulatory agencies play an important role in the development of the technological infrastructure in an organization. This result is consistent with previous findings that CP plays a significant role in the adoption of BDA powered by artificial intelligence (Bag et al., 2021). Our findings do not support the relationship between CP and MS and CP and TE, which is similar to another study where CP was found not to influence human skills (Dubey et al., 2019a, 2019b, 2019c). This could be because the intangible resources required for TTB may not be sensitive to the policies, rules and regulations laid down by governmental agencies. The employees of the organization might be impacted by the stakeholders in the supply chain and the competitors to a greater extent due to increased interaction and higher accountability. The results also support the relationship between NP and MS and NP and TE, which is a similar finding to other studies (Bag et al., 2021; Dubey et al., 2019a, 2019b, 2019c). However, our findings also contradict these prior studies by not validating the relationship between NP and tangible resources. When it comes to the role of MP, our results offer similar findings to other studies by demonstrating a significant relationship between MP and ITI, MP and MS, and MP and TE (Chaubey & Sahoo, 2021; Liang et al., 2007).

Next, our analysis focuses on the resources that are possessed by an organization and the unique combinations which yield TTB. Our results show that the three resources, ITI, MS, and TE, have a significant role to play when it comes to building the TTB capabilities of the organization. This finding is in line with similar studies which support the role of tangible resources and workforce skills (Bag et al., 2021; Dubey et al., 2019a, 2019b, 2019c); the role of ITI in driving the adoption of BDA (Aboelmaged & Mouakket, 2020; Wamba et al., 2017); the role of MS in adopting T&T technologies (Matta et al., 2012; Orji et al., 2020); and the role of TE in the take up of new technologies (Saberi et al., 2019; Wamba et al., 2008).

We found a significant moderating effect of OC on the path between ITI and TTB but no significant moderating effect of OC on the paths between MS and TE and TTB. Therefore, our findings in this respect provide some confirmation of prior research i.e. the significant effect of OC on big data predictive analytics capability (Dubey et al., 2019a, 2019b, 2019c). The lack of a moderating effect in our study may have risen due to managerial skills, such as proactive risk management, human centrism and creativity, and technical expertise, being combined with the insights generated by TTB systems. Therefore, creating an organizational culture where decision-making is predominantly driven by data and information rather than gut feeling.

Our analysis then focused on the usage of TTB to evaluate if UIP, RTD and US could be established. We found that good TTB does relate to UIP, RTD and US, thereby suggesting it helps the organization with effective SCRM. These results are consistent with the findings and suggestions of Ivanov et al. (2019) about the impact of digital technology and Industry 4.0 on supply chain risk analytics. The adoption of BDA (Choi et al., 2018) and T&T technologies (Nishat Faisal et al., 2006) in SCRM has also been investigated in previous studies, with findings similar to those in our study. From our results, we infer that OF plays a key moderating role on the path between TTB and UIP, and TTB and US. Thus, the importance of organizational flexibility is illustrated; a finding which is consistent with other studies which focus on BDA driven by artificial intelligence to help with circular economy capabilities (Bag et al., 2021); the presence of organization flexibility to act on insights generated through supply chain analytics, which in turn lead to superior cost and delivery performance (Srinivasan & Swink, 2018); and the increase of organization flexibility for better SCRM (Rajaguru & Matanda, 2013).

Finally, our results offer further evidence that ensuring SCRM through UIP, RTD and US would lead to a competitive advantage (CA). This finding aligns itself with other studies, which demonstrate how an organization with strong SCRM practices can create a CA for itself (Kırılmaz & Erol, 2017; Kwak et al., 2018). Next, we discuss our contributions to theory and practice.

7.1 Theoretical contributions

An initial study of the existing literature showed that there is a lack of theoretical studies around external and internal factors influencing the development of SCRM. Furthermore, linking this to the benefits that technology-driven SCRM can bring. Also, there was a gap when it came to studies that were based on proactive models (Rinaldi et al., 2022). Whilst current literature speaks about the benefits that technology would bring to a supply chain and offered insights on how technology can drive proactive SCRM, there was no study which provided a grounded theoretical framework talking about how an organization could develop its competitive advantage by developing these capabilities. To address these gaps, our study contributes by drawing from IT and RBV to theorise on important external and internal factors significantly influencing the successful implementation of T&T-BDA-driven SCRM. In doing so we extend existing knowledge by identifying the importance of managerial skills to manage technology projects and to maximise benefits realisation. In addition, we confirm the body of evidence studying the effects of institutional forces on technological infrastructure and technical skills, particularly the works of Bag et al. (2021) and Dubey et al., (2019a, 2019b, 2019c).

We make a unique contribution to the literature by explicitly highlighting the importance of managerial skills in addition to technical skills and technological infrastructure. So, intelligence, creativity, diplomacy and tact, administrative ability, persuasiveness and social skills are some of the key managerial skills of successful SCRM leaders (Carmeli & Tishler, 2006). We lend weight to the argument that human and administrative skills are more important than technical skills and citizenship behaviour (Tonidandel et al., 2012) and the argument that a manager must also be emotionally intelligent to achieve favourable outcomes (Carmeli, 2003). We also contribute to theory by identifying the influence of organizational culture and organization flexibility on successful technology adoption initiatives, by highlighting three conditions leading to proactive SCRM: uninterrupted information processing, reduced time disruption, and uninterrupted supply; and by showing that competitive advantage is a by-product of effective SCRM.

We extend our knowledge of IT in a SCRM context, by showing that two institutional forces, normative pressure, and mimetic pressure, have a significant effect on the managerial skills that are exhibited by the organization. This effect can arise from the need for managers and leaders to mimic competitors to build technological capabilities to solve problems that are beyond the organization’s reach (Krell et al., 2016). It can also arise from the need for organization’s leaders to ensure that they are on par with the other players in their supply chain and, therefore, can build stakeholder relationships. The importance of good managerial skills in technology implementation, shown in our study, supports previous literature. As such, we lend weight to the argument that a proper orchestration of resources is required to realize the benefits of new technology, and that the right managerial skills are required for collaboration between the business and technical teams in an organization (Barlette & Baillette, 2020; Chadwick et al., 2015).

Our study reiterates the importance of organizational flexibility in realizing full benefits from the adoption of novel technologies. Without this flexibility, an organisation will not be able to deploy additional resources as and when required (Srinivasan & Swink, 2018). Prior studies have shown that organizational flexibility is an important determinant of competitive advantage (Dubey et al., 2019a, 2019b, 2019c) and such flexibility is key to making timely changes to the existing supply chain to respond to external events (Srinivasan & Swink, 2018).

In summary, this study, which has been grounded on two theories and analysed empirically, has made significant contributions toward understanding how technology-driven SCRM can help firms develop a competitive advantage by improving the ability of their supply chains to handle risks.

7.2 Managerial implications

Our study offers useful insights for managers seeking to adopt T&T-BDA systems to manage their supply chain risks. Adopting a proactive technology-driven SCRM strategy requires managers to focus on two types of design: process and system. Process design involves modifying the existing processes, such as supplier evaluation, procurement, logistics process, etc. with a risk component. This may lead to additional costs, but studies have shown that the benefits outweigh the costs (Kırılmaz & Erol, 2017). System design involves designing the technological architecture in a way that solves the problem at hand; whilst, at the same time, matching the goals and vision of the organization. These designs should begin with a problem structuring approach, which will help decision-makers by providing a framework for solving their risk problems (Rosenhead, 1996). With the requirement for new processes and technologies, the design focus shifts to bridging the gap between workforce skills and training and the realization of the performance capacities of a new technological project. Therefore, there needs to be a human-centred approach to designing the adoption of new technologies and project introductions, to ensure than humans, through their skills and understanding, can benefit from machines designed to work with them. So that they are complementary to existing processes and work patterns, thereby enabling the firm to realize the entire operational benefits that are offered (Philips & Nikolopoulos, 2019).

Pressures from other stakeholders in the supply chain and a firm’s competitors influence managerial skills. These managerial skills, such as leadership, negotiation, personal organization, proactive approach to risk management, human centrism, design flair, emotional intelligence, creativity, and knowledge management, are of vital importance to fully realize the benefits of technology. All managers of the organization across various departments must come together to bundle all their skills into a separate resource. Unlike technological infrastructure and technical expertise, this bundle will be hard to imitate by other firms. This is because managerial skills and practices, including inter-departmental capabilities and competency building, are extremely specific to the organization and are developed over time. Managers can contribute by framing the policies required for the usage of data and they can help build a culture where data-driven insights are given considerable consideration.

The importance of technical skills is evident from various studies that have discussed, in detail, how technical expertise is the key to deriving benefits from technology. However, technology is on a rapid growth trajectory, which means the shelf-life of technologies is reducing. Thus there is a need for continuous training and upskilling on the technical front to ensure the right capabilities are in place. One way of doing this is by having more strategic collaborations with educational institutions, joint public–private initiatives (i.e. digital skills hubs, SME training and support) and through the development of innovative pedagogical approaches (Ra et al., 2019).

Our study shows how regulatory agencies, governing bodies, and competitors influence firms to improve and upgrade the technologies deployed. With provenance becoming an increasingly important topic (Kim & Laskowski, 2018) and regulations and laws revolving around the right usage of data being implemented to protect the privacy of individuals (Dwivedi et al., 2021) managers will need to quickly adapt to these practices to continue running a business successfully.

Organizational flexibility is critical for organizations to practically realize the benefits of technology. An organization which demonstrates flexibility eventually has improved performance. Organizational flexibility is even more important in volatile markets (Srinivasan & Swink, 2018). One of the ways managers can promote flexibility is through strategic contingency planning, where all the actors in the supply chain collaborate and prepare themselves for reactions to adverse events—which can be catalysed through technology (Hanna et al., 2010).

Mimetic pressures have played a critical role in building the technological resources in the firms surveyed, with firms building and upgrading their existing resources in response to the benefits they have seen their competitors realize. These benefits could eventually lead to the competitors having an advantage over them and other firms in the industry. Building capabilities by observing competitors can also reduce research and experimentation expenses, and reduce the risks of technology implementation not being a success (Nilashi et al., 2016). This can be particularly helpful in current uncertain times as it can help build viable solutions with minimum costs (Yang & Kang, 2020).

7.3 Limitations and future research directions

There is a range of factors influencing SCRM performance which makes cross-country comparisons problematic. Our study was conducted in India during a period when firms were recovering from the effect of the pandemic and global disruptions. The effect of such disruptions on supply chains, though high, varies in intensity across different countries. Some countries already had in-built national cultural resilience and mitigation plans in place, as they had experienced and lived through previous pandemics i.e. South Korea (Oh et al.,. 2018) and through major disasters i.e. Japan (Koshimura & Shuto, 2015). External factors such as varying geography, population demographics, and the different timing, duration, and stringency of governmental responses (to the pandemic) are difficult to control.

Therefore, whilst this study aims to provide generic insights into SCRM, care must be taken in applying our findings to other countries and economies. Although the type of industry does not seem to affect our hypothesized model, we did consider the maturity level of the supply chain. This provides an opportunity for potential extension of our study, where researchers can map SCRM practices according to the maturity of a supply chain. Also, our study does not consider the volatility of markets and its influence on short and long-run decision-making, which refers to the uncertainty driven by the market (Srinivasan & Swink, 2018). Theoretically grounded empirical studies are needed to explore the role of market volatility in shaping the practice of SCRM, perhaps through the application of contingency theory. Finally, future research could focus on the role of other innovative technologies, such as modern sensors for automatic data collection, coupled with their interactions with T&T systems and machine learning for either giving suggestions or making autonomous decisions. In-depth technological and scientific studies could analyse how each of the practices of SCRM, discussed in our study, are undertaken.

8 Conclusion

SCRM has become a topic of great interest once again in recent years due to the advancement of technology and the dramatic negative effects on supply chain performance caused by global disruptions and the so-called “polycrises”. SCRM is important in helping organisations to bounce back quickly after a disruption or series of ongoing demand and supply disruptions such as COVID-19. Furthermore, proactive SCRM, which is driven by novel technologies, helps supply chains mitigate, respond, and recover from disruptions. Our study provides empirical data that reveals the significant relationships between the antecedents of T&T/BDA capabilities i.e. information technology infrastructure, managerial skills, and technical skills and, in turn, their external drivers, taken from institutional theory, in the form of coercive, normative, and mimetic pressures.

We further show how technologically-driven SCRM yields operational benefits in the areas of uninterrupted information processing, reduced time disruptions and uninterrupted supply. Furthermore, we identify how these benefits, in turn, create a competitive advantage for the firm, by improving its resilience and responsiveness. Lastly, we demonstrate the influence of organisational culture and flexibility as moderators of relationships. By bringing all these different strands together in a unifying framework we provide organisations with evidence to help them in their investment decisions, by addressing whether technology investment, in such areas as Track-and-Trace (T&T) and Big Data Analytics (BDA) systems, enhances SCRM sufficiently to outweigh the costs of designing and adopting such technology. We also make a significant contribution to theory, by combining the resource-based view of the firm and institutional theory, to show how technology benefits can be implemented to aid SCRM.

Notes

Banker (2023) A polycrises occurs when concurrent shocks, deeply interconnected risks, and eroding resilience become intertwined (refer to: The World Economic Forum Warns Of Polycrises (forbes.com)).

References

Aboelmaged, M., & Mouakket, S. (2020). Influencing models and determinants in big data analytics research: A bibliometric analysis. Information Processing & Management. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ipm.2020.102234

Agrawal, T. K., Kumar, V., Pal, R., Wang, L., & Chen, Y. (2021). Blockchain-based framework for supply chain traceability: A case example of textile and clothing industry. Computers & Industrial Engineering. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cie.2021.107130

Aibinu, A., & Jagboro, G. (2002). The effects of construction delays on project delivery in Nigerian construction industry. International Journal of Project Management, 20(8), 593–599. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0263-7863(02)00028-5

Akter, S., FossoWamba, S., & Dewan, S. (2017). Why PLS-SEM is suitable for complex modelling? An empirical illustration in big data analytics quality. Production Planning & Control, 28(11–12), 1011–1021. https://doi.org/10.1080/09537287.2016.1267411s

Akter, S., Gunasekaran, A., Wamba, S. F., Babu, M. M., & Hani, U. (2020). Reshaping competitive advantages with analytics capabilities in service systems. Technological Forecasting and Social Change. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2020.120180

Akter, S., Wamba, S. F., Gunasekaran, A., Dubey, R., & Childe, S. J. (2016). How to improve firm performance using big data analytics capability and business strategy alignment? International Journal of Production Economics, 182, 113–131. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpe.2016.08.018

Al-Abdallah, G. M., & Al-Salim, M. I. (2021). Green product innovation and competitive advantage: An empirical study of chemical industrial plants in Jordanian qualified industrial zones. Benchmarking: an International Journal. https://doi.org/10.1108/BIJ-03-2020-0095

Ali, O., Shrestha, A., Soar, J., & Wamba, S. F. (2018). Cloud computing-enabled healthcare opportunities, issues, and applications: A systematic review. International Journal of Information Management, 43, 146–158. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2018.07.009

Aloysius, J. A., Hoehle, H., Goodarzi, S., & Venkatesh, V. (2018). Big data initiatives in retail environments: Linking service process perceptions to shopping outcomes. Annals of Operations Research, 270(1–2), 25–51. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10479-016-2276-3

AmooDurowoju, O., Kai Chan, H., & Wang, X. (2012). Entropy assessment of supply chain disruption. Journal of Manufacturing Technology Management, 23(8), 998–1014. https://doi.org/10.1108/17410381211276844

Asante, J., Kissi, E., & Badu, E. (2018). Factorial analysis of capacity-building needs of small- and medium-scale building contractors in developing countries. Benchmarking: an International Journal, 25(1), 357–372. https://doi.org/10.1108/BIJ-07-2016-0117

Bag, S., Gupta, S., & Telukdarie, A. (2018). Importance of innovation and flexibility in configuring supply network sustainability. Benchmarking: an International Journal, 25(9), 3951–3985. https://doi.org/10.1108/BIJ-06-2017-0132

Bag, S., Pretorius, J. H. C., Gupta, S., & Dwivedi, Y. K. (2021). Role of institutional pressures and resources in the adoption of big data analytics powered artificial intelligence, sustainable manufacturing practices and circular economy capabilities. Technological Forecasting and Social Change. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2020.120420

Banker, S. (2023). The world economic forum warns of polycrises (refer to: The World Economic Forum Warns of Polycrises (forbes.com)).

Barlette, Y., & Baillette, P. (2020). Big data analytics in turbulent contexts: Towards organizational change for enhanced agility. Production Planning & Control. https://doi.org/10.1080/09537287.2020.1810755

Barney, J. (1991). Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. Journal of Management, 17(1), 99–120. https://doi.org/10.1177/014920639101700108

Barreto, L., Amaral, A., & Pereira, T. (2017). Industry 4.0 implications in logistics: An overview. Procedia Manufacturing, 13, 1245–1252. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.promfg.2017.09.045

Belhadi, A., Kamble, S., Jabbour, C. J. C., Gunasekaran, A., Ndubisi, N. O., & Venkatesh, M. (2021). Manufacturing and service supply chain resilience to the COVID-19 outbreak: Lessons learned from the automobile and airline industries. Technological Forecasting and Social Change. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2020.120447

Berman, B. (2008). Strategies to detect and reduce counterfeiting activity. Business Horizons, 51(3), 191–199. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bushor.2008.01.002

Bharadwaj, A. S. (2000). A resource-based perspective on information technology capability and firm performance: An empirical investigation. MIS Quarterly, 24(1), 169. https://doi.org/10.2307/3250983

Boyd, D., & Crawford, K. (2012). Critical questions for big data. Information, Communication & Society, 15(5), 662–679. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2012.678878

Braunscheidel, M. J., & Suresh, N. C. (2009). The organizational antecedents of a firm’s supply chain agility for risk mitigation and response. Journal of Operations Management, 27(2), 119–140. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jom.2008.09.006

Byrd, T. A., & Turner, D. E. (2000). Measuring the flexibility of information technology infrastructure: Exploratory analysis of a construct. Journal of Management Information Systems, 17(1), 167–208. https://doi.org/10.1080/07421222.2000.11045632

Byrd, T. A., & Turner, D. E. (2001). An exploratory examination of the relationship between flexible IT infrastructure and competitive advantage. Information & Management, 39(1), 41–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0378-7206(01)00078-7

Carmeli, A. (2003). The relationship between emotional intelligence and work attitudes, behavior and outcomes. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 18(8), 788–813. https://doi.org/10.1108/02683940310511881

Carmeli, A., & Tishler, A. (2006). The relative importance of the top management team’s managerial skills. International Journal of Manpower, 27(1), 9–36. https://doi.org/10.1108/01437720610652817

Chadwick, C., Super, J. F., & Kwon, K. (2015). Resource orchestration in practice: CEO emphasis on SHRM, commitment-based HR systems, and firm performance. Strategic Management Journal, 36(3), 360–376. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.2217

Chakuu, S., Masi, D., & Godsell, J. (2020). Towards a framework on the factors conditioning the role of logistics service providers in the provision of inventory financing. International Journal of Operations and Production Management, 40(7–8), 1225–1241. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJOPM-06-2019-0502

Chaubey, A., & Sahoo, C. K. (2021). Assimilation of business intelligence: The effect of external pressures and top leaders commitment during pandemic crisis. International Journal of Information Management. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2021.102344

Chircu, A. M., Sultanow, E., & Chircu, F. C. (2014). Cloud computing for big data entrepreneurship in the supply chain: Using SAP HANA for pharmaceutical track-and-trace analytics. In 2014 IEEE world congress on services (pp. 450–451). IEEE. https://doi.org/10.1109/SERVICES.2014.84

Choi, S. H., Yang, B., Cheung, H. H., & Yang, Y. X. (2015). RFID tag data processing in manufacturing for track-and-trace anti-counterfeiting. Computers in Industry, 68, 148–161. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compind.2015.01.004

Choi, T.-M., Wallace, S. W., & Wang, Y. (2018). Big data analytics in operations management. Production and Operations Management, 27(10), 1868–1883. https://doi.org/10.1111/poms.12838

Choudhury, A., Behl, A., Sheorey, P. A., & Pal, A. (2021). Digital supply chain to unlock new agility: A TISM approach. Benchmarking: an International Journal. https://doi.org/10.1108/BIJ-08-2020-0461

Christopher, M., & Lee, H. (2004). Mitigating supply chain risk through improved confidence. International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management, 34(5), 388–396. https://doi.org/10.1108/09600030410545436

Cohen, J. (1992). Statistical power analysis. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 1(3), 98–101. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8721.ep10768783