Abstract

Drug use, mental distress, and other psychosocial factors threaten HIV care for youth living with HIV (YLWH). We aimed to identify syndemic psychosocial patterns among YLWH and examine how such patterns shape HIV outcomes. Using baseline data from 208 YLWH enrolled in an HIV treatment adherence intervention, we performed latent class analysis on dichotomized responses to 9 psychosocial indicators (enacted HIV stigma; clinical depression and anxiety; alcohol, marijuana, and illicit drug misuse; food and housing insecurity; legal history). We used multinomial logistic regression to assess latent class-demographic associations and the automatic Bolck-Croon-Hagenaars method to assess HIV outcomes by class. Mean age of participants was 21 years; two thirds identified as cis male, 60% were non-Hispanic Black, and half identified as gay. Three classes emerged: “Polydrug-Socioeconomic Syndemic” (n = 29; 13.9%), “Distress-Socioeconomic Syndemic” (n = 35, 17.1%), and “Syndemic-free” (n = 142, 69.0%). Older, unemployed non-students were overrepresented in the “Polydrug-Socioeconomic Syndemic” class. Missed/no HIV care appointments was significantly higher in the “Polydrug-Socioeconomic Syndemic” class (81.4%) relative to the “Syndemic-free” (32.8%) and “Distress-Socioeconomic Syndemic” (31.0%) classes. HIV treatment nonadherence was significantly higher in the “Polydrug-Socioeconomic Syndemic” class (88.5%) relative to the “Syndemic-free” class (59.4%) but not the “Distress-Socioeconomic Syndemic” class (70.8%). Lack of HIV viral load suppression was non-significantly higher in the “Polydrug-Socioeconomic Syndemic” class (29.7%) relative to the “Syndemic-free” (16.2%) and “Distress-Socioeconomic Syndemic” (15.4%) classes. Polydrug-using, socioeconomically vulnerable YLWH are at risk for adverse HIV outcomes, warranting tailored programming integrated into extant systems of HIV care.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

HIV continues to impact youth in the United States (US). According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), nearly 20% of new HIV diagnoses in 2021 occurred among individuals aged 13 to 24 years, and recent research indicates that most of these diagnoses occurred among youth of color [1, 2]. CDC data also demonstrate that youth living with HIV (YLWH) encounter difficulties across the HIV care continuum: 20% receive no HIV care, 45% are unretained in care, and 35% are virally unsuppressed [3]. Moreover, a recent systematic review and meta-analysis found that 47% of YLWH in North America were nonadherent to HIV treatment [4]. Supporting YLWH, especially racial/ethnic minority YLWH, is critical to their engagement in the HIV care continuum, their living well with HIV, and reducing HIV transmission to end the HIV epidemic in the US [5].

Psychosocial conditions may underlie observed HIV care continuum disparities experienced by YLWH [1, 6]. Specifically, substance misuse (e.g., alcohol, marijuana, illicit drugs) [7,8,9,10,11], mental health concerns (e.g., depression, anxiety) [7, 8, 12], enacted HIV stigma (e.g., from social network, healthcare providers) [13,14,15], poverty (e.g., food and housing insecurity) [10, 16,17,18,19], and criminal justice involvement (e.g., transitioning to or [re]establishing care following release from incarceration) [20, 21] have all been linked to poor retention in HIV care and nonadherence to HIV treatment (or elevated HIV viral load, indicative of nonadherence to HIV treatment). Youth who experience these conditions may be especially vulnerable to their impact because youth have yet to mature socially, emotionally, cognitively, or physically [22], and because youth may lack access to resources to mitigate the effects of these conditions [23].

Moreover, psychosocial conditions often co-occur, further exacerbating health outcomes. To describe such a scenario, Singer [24, 25] proposed the term syndemic, denoting “a set of closely interrelated, endemic and epidemic conditions,” an “interrelated complex of health and social crises,” and the “synergistic interaction of diseases and social conditions” that contribute to disproportionate disease burden [25, 26]. Additive and latent variable (e.g., latent class analysis [LCA]) approaches are often used to study syndemic health states. Additive approaches typically involve regressing an outcome on a syndemic index modeled continuously or categorically. For example, among YLWH, Kuhns and colleagues [27] showed a decreasing likelihood of HIV treatment adherence and HIV viral load suppression with an increasing number of co-occurring conditions. In various research with adults living with HIV, the likelihood of HIV care appointment attendance, HIV treatment adherence, and HIV viral load undetectability decreased as the number of co-occurring conditions increased [28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35].

LCA approaches involve identifying patterns of co-occurring conditions that reflect underlying subgroups, or classes, of people with similar profiles in a heterogeneous population [36, 37]. These approaches provide complementary but more nuanced findings than additive approaches. For example, Hotton et al. [38] identified two syndemic patterns (“higher adversity,” “lower adversity”) among trans women of color living with HIV. Participants in the “higher adversity” class, which featured legal history, housing instability, and other socioeconomic insecurities, were less likely to have recently utilized HIV care and less likely to be virally suppressed. Traynor et al. [39] identified three syndemic patterns (“lower barriers,” “higher barriers/history of abuse and intimate partner violence,” “higher barriers/history of discrimination, abuse, and intimate partner violence”) among substance-using people living with HIV (PLWH). Those in the “higher barriers” class that featured discrimination, abuse, and violence did not benefit from a patient navigation intervention to increase HIV care engagement and viral suppression, unlike participants in the other classes. Robinson et al. [40] identified four syndemic patterns (“moderate substance use/mental illness,” “high mental illness,” “moderate substance and mental illness/high familial conflict non-negotiation,” “high substance use/high mental illness”) among African-Americans living with HIV in Baltimore, Maryland. Participants in the “high substance use/high mental illness” class were the least likely to have achieved HIV viral suppression.

Whether defined by number or pattern, psychosocial syndemics exist among PLWH and shape HIV outcomes. However, there has been limited research examining syndemics among YLWH [e.g., 27]. We sought to fill this gap with the present study. Specifically, we aimed to identify classes of co-occurring psychosocial conditions among YLWH, determine demographic correlates of class membership, and assess the extent to which HIV care continuum outcomes varied across classes. Findings can inform future research on syndemics among YLWH, as well as inform intervention and programming efforts to identify YLWH with the greatest need for HIV care support and comprehensive wraparound services.

Methods

Data Source, Participants, and Procedures

Data were drawn from a baseline assessment of YLWH enrolled in a randomized controlled trial of a web-based intervention called “YouTHrive,” which aimed to improve ART adherence and HIV treatment outcomes among YLWH in six urban areas in the US (Atlanta, Chicago, Houston, New York, Philadelphia, Tampa). Detailed methods have appeared elsewhere [41]. Briefly, enrollment began in August 2019 and ended in May 2022. Eligibility criteria included (a) being aged 15–24 years at enrollment, (b) living with HIV, (c) residing in one of the aforesaid six urban areas with availability to meet in-person for baseline and follow-up visits, (d) being currently prescribed antiretroviral therapy (ART; documented with prescription or pill bottle), (e) being English-speaking, (f) expecting to have continuous internet access and SMS messaging for the intervention period, (g) having an email address to use during the study period (or being willing to create one), (h) not being a member of an iTech Youth Advisory Board, and (i) not being enrolled in another ART adherence intervention research study. Pre-COVID, an additional eligibility criterion was required: that participants have either (a) a past-year detectable viral load test result while on ART for 3 or more months, (b) 1 or more missed HIV care appointments in the past 12 months, (c) no HIV care visit in the previous 6 months, or (d) < 90% ART adherence in the previous 4 weeks. This criterion was assessed through medical chart verification or self-report and applied to the one third of participants enrolled pre-COVID.

Eligible participants were recruited from HIV clinics or through community outreach efforts (e.g., targeted social media advertisements) and provided information on HIV treatment-related outcomes, mental health, HIV stigma, demographic characteristics, and other domains via a computer-assisted survey instrument. Participants received $50 for survey completion. This study is registered as a clinical trial (Clinical Trials # NCT03149757) and was approved by the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill Institutional Review Board (as the single institutional review board); parental consent was waived for participants aged 15–17 years.

Measures

Latent Class Indicators of Syndemic Factors

We used items developed by Earnshaw and colleagues to assess experiences of enacted HIV stigma [42, 43]. In response to the same prompt (“How often have people treated you this way in the past because of your HIV status?”), participants responded to 9 items (e.g., “Community/social workers have denied me services.”) on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 = Never to 5 = Very often. We calculated average scores and dichotomized them at 2 (set a priori) to separate those whose average score indicated often experiencing enacted stigma (> 2; i.e., somewhat often, often, very often; coded 1) from those whose average score did not indicate this (≤ 2, i.e., never or not often; coded 0).

Clinical depression and anxiety were assessed with the Patient Health Questionnaire-8 (PHQ-8) [44] and the Generalized Anxiety Disorder Assessment-7 (GAD-7) [45], respectively. Using one stem (“Over the past 2 weeks, how often have you been bothered by any of the following problems?”), PHQ-8 and GAD-7 items assessed the frequency of having experienced depressive (e.g., “Little interest in pleasure or doing things”) and anxiety symptoms (e.g., “Feeling nervous, anxious, or on edge”). Participants responded on a 4-point Likert scale for each, ranging from 0 = Not at all to 3 = Nearly every day. Items were summed on each scale to yield a composite score, with scores ≥ 10 indicative of a clinical level of the assessed mental health concern.

Alcohol misuse, marijuana misuse, and illicit drug misuse (cocaine, methamphetamines, inhalants, downers, hallucinogens, opioids) were assessed with the Alcohol, Smoking and Substance Involvement Screening Test [46]. For those endorsing ever having used a given substance, 6 items (e.g., “During the past three months, how often have you failed to do what was normally expected of you because of your use of [substance]?”) assessed use over the previous 3 months. Likert-scale response options for the first 4 items ranged from 0 = Never to 6 = Daily or almost daily (item-dependent; for some, the Daily or almost daily option was scored as 7 or 8). Response options to the final 2 items included 0 = No, never; 3 = Yes, but not in the past 3 months; and 6 = Yes, in the past 3 months. Items were summed to yield a compose score. Total scores of ≥ 11 on the alcohol items and ≥ 4 on all other items were indicative of misuse. We dichotomized based on these thresholds. As misuse of individual illicit drugs was low, we created a global illicit drug misuse variable: a score of 4 or higher on any of the aforementioned illicit drugs was considered illicit drug misuse.

Food insecurity was assessed with one item asking about the frequency participants or their family had to reduce meal sizes or skip meals due to inadequate food or money. Response options ranged from 1 = Almost every week to 4 = Did not have to skip or cut the size of meals. We dichotomized this item, coding any endorsement (1–3) as 1 and no endorsement (4) as 0. Unstable housing was assessed with several dichotomous items assessing whether participants had spent at least one night in a shelter, in a public place not intended for sleeping, on the street or anywhere outside, temporarily doubled up with a friend or family member, in a temporary housing program, or in a welfare or voucher hotel/motel. We created a binary variable based on these responses, with endorsement of any being coded 1 and non-endorsement of all coded 0. Legal involvement was assessed with two dichotomous items asking whether participants had ever been (a) arrested or (b) put in jail, prison, or juvenile detention. Endorsement of either item was coded 1; non-endorsement of both was coded 0.

Outcomes

We assessed HIV care engagement with two items: “In the last 12 months, how many scheduled appointments did you have?” and “In the last 12 months, how many of your scheduled appointments did you miss because you didn’t show or forgot?” Participants could write-in a numerical response for each. We created a continuous outcome for missed HIV care appointments (based on responses to the second item), and a binary outcome for any missed HIV care appointments or having none scheduled at all (i.e., those who responded 0 to the first item and > 0 to the second item). We assessed HIV treatment adherence with one item: “In the last 30 days, on how many days did you miss at least one dose of any of your HIV medicines?” Participants could write-in a numerical response. We used this raw response as a continuous outcome, and we used dichotomized responses (i.e., any response > 0 coded 1) as a binary outcome. We assessed viral load via biospecimen testing carried out at participating HIV clinics and created a dichotomous unsuppressed viral load variable (> 200 copies/mL).

Other Variables

Demographic variables included age in years (continuous and age group [21–24 years vs. 15–20 years]), gender identity (cis man, cis woman, gender-diverse), race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic Black, non-Hispanic other race, Hispanic), sexual identity (gay, bisexual or other non-gay identity, straight), education (enrolled in school or not), employment status (unemployed and non-student vs. employed and/or student), relationship status (partnered vs. single), and insurance status (uninsured vs. insured).

Statistical Analysis

We computed descriptive statistics for variables of interest and assessed missingness. We performed LCA on responses to the 9 syndemic factors. Models with 2–4 classes were considered, and different sets of starting values were used to assess model identification. We selected the best-fitting model using Akaike’s Information Criterion (AIC), sample size-adjusted Bayesian Information Criterion (SSA-BIC), integrated classification likelihood-BIC (ICL-BIC), adjusted Vuong-Lo-Mendell-Rubin likelihood ratio test (aVLMR-LRT), bootstrapped likelihood ratio test (BLRT), log-likelihood value, entropy statistic of class delineation, lowest average classification probability, lowest class prevalence, parsimony, and scientific interpretation [37, 47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55]. We used a full maximum likelihood estimator under the assumption data were missing at random to derive estimates based on all available data while also accounting for missingness [56, 57]. We examined standardized bivariate residuals of expected versus observed responses to indicator pairs to assess conditional independence, with plans to allow dependent items (z>|1.96|), if present, to correlate [58]. We considered indicator probabilities of < 0.30 as low, ≥ 0.30 < 0.70 as moderate, and ≥ 0.70 as high.

Covariate associations with class membership were examined via multinomial logistic regression using the automatic 3-step method to correct for potential classification error in latent class assignment [59, 60]. Coefficients were exponentiated to generate unadjusted odds ratios (OR); Wald tests, with statistical significance set at 0.05 and 95% confidence intervals (CI), were also calculated and examined. We used the automatic Bolck-Croon-Hagenaars (BCH) method – which independently estimates outcome prevalence or class mean while simultaneously estimating the measurement model [59] – to examine HIV outcomes across classes. We assessed class differences in outcomes with chi-square tests. Descriptive analyses and data preparation were conducted in Stata Version 15 (StatCorp, College Station, TX, USA). LCA and related procedures were conducted in Mplus Version 8.5 (Muthen & Muthen, Los Angeles, CA).

Results

Sample Characteristics

Out of 208 participants enrolled at baseline, 206 provided complete LCA indicator data and were included in the analysis. Mean age was 21 years, two thirds (n = 139) identified as a cisgender man, and 59.7% (n = 123) were non-Hispanic Black. Roughly half (n = 102) identified as gay, and 3 in 10 (n = 61) were partnered. Over half (n = 110) were in school, and of these, the majority (n = 78) reported currently receiving post-high school education. Almost 1 in 5 (n = 37) were unemployed non-students and were also uninsured (Table 1).

Of the 9 syndemic factors examined, marijuana misuse was the most endorsed (48.1%; n = 99), followed by food insecurity (27.7%; n = 57), legal involvement (26.2%; n = 54), clinical depression and anxiety (both 23.8%; n = 49), unstable housing and alcohol misuse (both 18.4%; n = 38), and illicit drug misuse and enacted stigma (both 11.7%; n = 24). More than three quarters (n = 157) of participants reported the presence of ≥ 1 syndemic factor, with 24.3% (n = 50) reporting 1 factor only, 19.4% (n = 40) reporting 2 factors, and 32.5% (n = 67) reporting ≥ 3.

More than a third (n = 72) of participants either missed or did not schedule any HIV care appointments in the past year. The average number of missed HIV care appointments for those who had scheduled any was 0.77 (SD = 1.4; range = 0–9); 5 participants reported they had not scheduled any appointments at all during the past year. Almost two thirds (n = 130) reported at least 1 day in the prior 30 in which they had missed at least 1 dose of HIV treatment. Average number of days of having missed ≥ 1 doses was 2.7 (SD = 4.6; range = 0–30). Biospecimen testing showed 16.0% (n = 33) had unsuppressed HIV viral load.

Latent Class Enumeration

The best log-likelihood was successfully replicated several times for each unconditional 2–4 class solution using numerous sets of increasingly high starting values, suggesting model identifiability for each solution. The AIC, SSA-BIC, and ICL-BIC decreased from the 2- to the 3-class model but increased from the 3- to the 4-class model, with an elbow depicted at 3 classes. The BLRT indicated that the 2-class model fit the data significantly better than the 1-class model (BLRT = 161.49, df = 10, p < 0.001) and that the 3-class model fit the data significantly better than the 2-class model (BLRT = 43.27, df = 10, p < 0.001), but that the 4-class model did not fit the data significantly better than the 3-class model (BLRT = 19.93, df = 10, p = 0.364). Similarly, the aVLMR-LRT indicated that the 2-class model fit the data significantly better than the 1-class model (aVLMR-LRT = 158.52, df = 10, p < 0.001) and that the 3-class model fit the data marginally better than the 2-class model (aVLMR-LRT = 42.47, df = 10, p = 0.062), but that the 4-class model did not fit the data significantly (or marginally) better than the 3-class model (aVLMR-LRT = 19.57, df = 10, p = 0.484). Entropy and average latent class probabilities exceeded 0.80 for the 3-class model, indicating good class separation, and lowest class prevalence (14.3%) exceeded the optimal threshold of 5 ~ 9%. Weighing this information, we selected the 3-class model (Table 2).

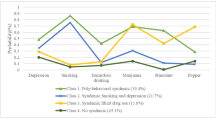

Class 1, “Polydrug-Socioeconomic Syndemic” (13.9%, n = 29), featured high probabilities of alcohol and marijuana misuse (0.71–0.97), moderate probabilities of illicit drug misuse, food and housing insecurity, and legal involvement (0.45–0.65), and low probabilities of other indicators (0.10–0.28). Class 2, “Distress-Socioeconomic Syndemic” (17.1%, n = 35), featured high probabilities of clinical depression and anxiety (0.95–0.96), moderate probabilities of enacted HIV stigma, marijuana misuse, food insecurity, and legal involvement (0.41–0.59), and low probabilities of other indicators (0.19–0.29). Class 3, “Syndemic-free” (69.0%, n = 142), featured a moderate probability of marijuana misuse (0.36) and low probabilities of other indicators (0.04–0.19; Fig. 1).

Correlates of Latent Class Membership

Increasing age was significantly associated with membership in the “Polydrug-Socioeconomic Syndemic” class relative to the “Syndemic-free” class (OR = 1.29, 95% CI = 1.05, 1.60). Compared to those who were employed and/or enrolled in school, unemployed non-students were significantly more likely to fall in the “Polydrug-Socioeconomic Syndemic” class relative to the “Syndemic-free” class (OR = 5.10, 95% CI = 1.63, 15.91). Compared to those aged 21–24 years and those without insurance, participants aged 15–20 years (OR = 0.18, 95% CI = 0.03, 1.09; p = 0.062) and with insurance (OR = 0.37, 95% CI = 0.12, 1.18; p = 0.094) were marginally less likely to fall into the “Polydrug-Socioeconomic Syndemic” class relative to the “Syndemic-free” class. Compared to those not in school, participants currently in school were marginally less likely to fall in the “Polydrug-Socioeconomic Syndemic” class (OR = 0.36, 95% CI = 0.11, 1.15; p = 0.085) and marginally more likely to fall in the “Distress-Socioeconomic Syndemic” class (OR = 2.47, 95% CI = 0.98, 6.24; p = 0.056) relative to the “Syndemic-free” class (Table 3).

Compared to those not enrolled in school, those enrolled in school were significantly more likely to fall in the “Distress-Socioeconomic Syndemic” class relative to the “Polydrug-Socioeconomic Syndemic” class (OR = 6.81, 95% CI = 1.63, 28.34). Compared to those aged 21–24 years, those aged 15–20 years were marginally more likely to fall in the “Distress-Socioeconomic Syndemic” class relative to the “Polydrug-Socioeconomic Syndemic” class (OR = 5.21, 95% CI = 0.73, 36.95; p = 0.099; not displayed).

HIV Care Outcomes by Latent Class

Having missed or had no HIV care appointments in the past year was most prevalent in the “Polydrug-Socioeconomic Syndemic” class (81.4%), which was significantly higher than that found in the “Distress-Socioeconomic Syndemic” (31.0%; χ2=10.49, df = 1, p = 0.001) and “Syndemic-free” classes (32.8%; χ2=13.62, df = 1, p < 0.001). Mean number of missed HIV care appointments in the past year was likewise highest in the “Polydrug-Socioeconomic Syndemic” class (1.27 missed appointments), which was significantly higher than that found in the “Syndemic-free” class (0.61 missed appointments; χ2=4.71, df = 1, p = 0.030) but not the “Distress-Socioeconomic Syndemic” class (1.00 missed appointments; χ2=0.34, df = 1, p = 0.562). Having missed any HIV treatment dose in the past month was most prevalent in the “Polydrug-Socioeconomic Syndemic” class (88.5%), which was significantly higher than that found in the “Syndemic-free” class (59.4%; χ2=8.32, df = 1, p = 0.004) but not the “Distress-Socioeconomic Syndemic” class (70.8%; χ2=2.00, df = 1, p = 0.158). There were no between-class differences with regard to mean number of days ≥ 1 HIV treatment doses were missed in the past month or with regard to unsuppressed HIV viral load prevalence. However, regarding the latter, prevalence was nearly twice as high in the “Polydrug-Socioeconomic Syndemic” class (29.7%) relative to the “Syndemic-free” (16.2%) and “Distress-Socioeconomic Syndemic” classes (15.4%; Fig. 2).

HIV care outcomes by latent class among YLWH in the US, 2019–2022 (N = 206)

YLWH: youth living with human immunodeficiency virus; US: United States

*Significantly higher than “Syndemic-free” (p < 0.001) and “Distress-Socioeconomic” (p < 0.01) classes; **significantly higher than “Syndemic-free” class (p < 0.01); ***significantly higher than “Syndemic-free” class (p < 0.05)

Discussion

We determined the extent to which psychosocial factors co-occurred to form latent syndemic classes among racially/ethnically diverse YLWH, identified correlates of latent class membership, and documented variation in HIV care continuum outcomes across classes. We found two syndemic classes (“Polydrug-Socioeconomic Syndemic,” “Distress-Socioeconomic Syndemic”), which featured numerous co-occurring psychosocial conditions, and one “Syndemic-free” class, which featured no co-occurrence. Prior research with adults living with HIV has documented two to five syndemic classes [38,39,40, 61,62,63], typically including one large syndemic-free class and multiple smaller syndemic classes [39, 40, 62, 63], reflecting our findings. Age, education, employment, and insurance status were associated with class membership to varying degrees, adding evidence to the existence of these classes as valid patterns of co-occurring psychosocial factors in this sample. HIV care engagement and treatment adherence significantly differed between classes, and unsuppressed viral load non-significantly differed.

Smallest in prevalence, the “Polydrug-Socioeconomic Syndemic” class depicted perhaps the most severe syndemic, featuring 6/9 co-occurring conditions: marijuana misuse, alcohol misuse, illicit drug misuse, legal involvement, and food and housing insecurity. Moreover, endorsement probabilities for all 6 conditions were the highest in this class compared to the other classes. Similar syndemic patterns have emerged among women with HIV in Canada and among Ryan White HIV/AIDS Program clients in Miami, Florida [61, 63]. Alcohol and marijuana misuse most strongly distinguished the “Polydrug-Socioeconomic Syndemic” from the “Distress-Socioeconomic Syndemic” class. Polydrug use has been commonly found in adolescent populations, often older adolescents [64], and we did find that older age was associated with “Polydrug-Socioeconomic Syndemic” class membership. That the “Polydrug-Socioeconomic Syndemic” class fared worse on all HIV care continuum outcomes is not surprising given its syndemic and reflects prior studies with adults in which classes featuring drug misuse and socioeconomic insecurity were most strongly linked to adverse HIV or other outcomes [38, 40, 61, 63].

The “Distress-Socioeconomic Syndemic” class also showed a severe syndemic, featuring 6/9 co-occurring conditions (clinical depression and anxiety, enacted HIV stigma, marijuana misuse, food insecurity, legal involvement). Of the 3 classes, endorsement probabilities for depression, anxiety, and stigma were highest in this class. Classes featuring mental distress have been previously identified among African-American adults living with HIV in Baltimore, Maryland [40], and classes featuring HIV stigma have been previously identified among women living with HIV in Canada [61]. Clinical depression and anxiety most strongly distinguished the “Distress-Socioeconomic Syndemic” class from the “Polydrug-Socioeconomic Syndemic” class. Both forms of mental distress disproportionately occur among YLWH [65] and were likely elevated during data collection (during the COVID-19 pandemic) due to youth’s being unable to attend school with peers [66]. Indeed, participants enrolled in school tended to fall into this class. Of course, mental distress could have been elevated for those not in school as well, secondary to isolation, socioeconomic difficulties, and other issues due to COVID-19 conditions [66].

This mental health burden is concerning given inadequate access to mental health resources for YLWH, especially for racial/ethnicity minority YLWH [65]. Mental distress will likely complicate – and be further exacerbated by – the transition to adult HIV care [67, 68]. HIV treatment nonadherence and missed HIV care appointments were non-significantly higher in the “Distress-Socioeconomic Syndemic” relative to the “Syndemic-free” class. Prior research has documented statistically significant negative associations between classes featuring mental distress and HIV viral suppression [40, 63], though samples used in these prior studies were larger than ours and comprised of adults rather than youth.

Socioeconomic vulnerabilities, particularly economic insecurity and legal involvement, were common in both syndemic classes. This is a reminder of the extent to which racial/ethnicity minorities (including youth) are disproportionately impacted by poverty and the justice system in the US [69, 70]. Such factors may present competing priorities, especially in conjunction with mental distress or substance use, that take precedence over and further complicate HIV care engagement, retention, and treatment adherence. Uninsured and unemployed nonstudent participants tended to fall into the “Polydrug-Socioeconomic Syndemic” class, reflecting how socioeconomic vulnerabilities were elevated for this group.

Notably, HIV outcomes were suboptimal for the “Syndemic-free” class as well. Though there was no evidence of a syndemic in this class, marijuana misuse was elevated. Whether this could account for suboptimal HIV care continuum outcomes in this class is unclear, though there is some evidence that marijuana use, especially recreational (vs. therapeutic), can affect adherence to HIV treatment [7, 71, 72]. Unmeasured syndemic factors, such as violence, childhood abuse, and mental health sequelae (e.g., posttraumatic stress), as well as structural, community, and interpersonal forms of racism, could have also played a role.

Limitations

Our findings should be considered in light of several limitations. Our cross-sectional data prevent the establishment of causality between our syndemic classes and HIV outcomes. Our sample was relatively small, urban, geographically diverse, and comprised of various racial, ethnic, sexual, and gender identities. Moreover, our sample was restricted to participants with access to technology (i.e., continuous internet access, email access, and SMS messaging for the intervention period), precluding participation by YLWH without such access and who may indeed be among the most marginalized and underserved. These issues may have affected the generalizability of our findings. We did not collect data on other potentially consequential psychosocial factors (e.g., racial/ethnic stigmas, violence) that may co-occur with the conditions we examined, which may have resulted in an incomplete picture of the challenges facing YLWH in our sample. Examination of other factors in addition to the ones we examined may reveal a number and composition of classes, and therefore distribution of HIV outcomes across classes, that differ from our findings. Finally, the majority of data collection occurred in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic, during which YLWH could have experienced elevated substance use, anxiety, and depression. Therefore, results should be replicated during non-pandemic times.

Research and Practice Implications

Given the dearth of research examining syndemic psychosocial patterns among YLWH, more studies with this population using similar analytic approaches are warranted. Such scholarship can help establish how common certain syndemic patterns are among YLWH. Additional research can also increase understanding on the interactive and potentially causal nature of commonly experienced psychosocial conditions among YLWH, such as the use of drugs or the experience of mental distress as responses to socioeconomic insecurities. Further research is needed to identify whether syndemic psychosocial conditions work in concert to shape HIV outcomes and require intervention approaches that target all conditions, or whether there are priority conditions that exert greater influence in shaping HIV outcomes and therefore merit narrower, more targeted interventions. Also, research to examine whether syndemic patterns are proxies for broader community, environmental, and structural disadvantage that shapes psychosocial syndemics would be helpful.

Addressing psychosocial syndemics necessitates tailored intervention and programming across multiple avenues. Improved, developmentally-tailored screening and treatment for substance misuse and mental distress are warranted, ideally integrated into extant systems of HIV care. However, community-/family-based interventions [73,74,75] may be important to implement or retain as alternatives due to medical mistrust and healthcare-related racism and discrimination. Novel approaches to treat substance use and mental distress could be incorporated as part of broader youth-/patient-centered HIV care models [76,77,78]. Youth-friendly technology-based treatment delivery modalities (e.g., video-conferencing/counseling, cellphone support), which have shown promise [79,80,81], could help address access and stigma-related barriers. Syndemic-focused, transdiagnostic treatment approaches may also be considered [82].

Connecting socioeconomically vulnerable youth to organizations that participate in programs like the Housing Opportunities for Persons with AIDS Program [83] and Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act’s Youth Activities Formula Grant Program or YouthBuild [84] can help youth access housing, education, vocational training, mentorship, and employment that prior legal involvement may otherwise hamper. Indeed, economic interventions can effectively support HIV care continuum progress [85]. In sum, increased focus on the social determinants of health to better serve YLWH is needed. Comprehensive, holistic interventions may show the greatest promise for improving the cascade of care for YLWH in the US.

Data Availability

De-identified data from this study are not available in a public archive but may be requested by emailing KJH.

Code Availability

Analytic code used to conduct the analyses in this study are not available in a public archive but may be requested by emailing JMW.

References

Allan-Blitz LT, Mena LA, Mayer KH. The ongoing HIV epidemic in American youth: challenges and opportunities. Mhealth 2021;7. https://doi.org/10.21037/mhealth-20-42.

CDC. HIV Surveillance Report. Diagnoses of HIV infection in the United States and dependent areas, 2021. Atlanta: 2023.

CDC. HIV Surveillance Supplemental Report: Monitoring selected national HIV prevention and care objectives by using HIV surveillance data - United States and 6 dependent areas. 2021. Atlanta: 2023.

Kim S-H, Gerver SM, Fidler S, Ward H. Adherence to antiretroviral therapy in adolescents living with HIV: systematic review and meta-analysis. AIDS 2014;28.

Office of Infectious Disease and HIV/AIDS Policy USD of H& HS (HHS). Ending the HIV epidemic: Plan for America: Overview 2020;2020. https://www.hiv.gov/federal-response/ending-the-hiv-epidemic/overview.

Zanoni BC, Mayer KH. The adolescent and young adult HIV cascade of care in the United States: exaggerated health disparities. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2014;28:128–35. https://doi.org/10.1089/apc.2013.0345.

Gross IM, Hosek S, Richards MH, Isabel Fernandez M. Predictors and profiles of antiretroviral therapy adherence among African American adolescents and young adult males living with HIV. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2016;30:324–38. https://doi.org/10.1089/apc.2015.0351.

Kolmodin Macdonell K, Jacques-Tiura AJ, Naar S, Isabella Fernandez M. Predictors of self-reported adherence to antiretroviral medication in a Multisite study of ethnic and racial minority HIV-Positive youth. J Pediatr Psychol. 2016;41:419–28. https://doi.org/10.1093/jpepsy/jsv097.

Kuchinad KE, Hutton HE, Monroe AK, Anderson G, Moore RD, Chander G. A qualitative study of barriers to and facilitators of optimal engagement in care among PLWH and substance use/misuse. BMC Res Notes. 2016;9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13104-016-2032-4.

Colasanti J, Stahl N, Farber EW, Del Rio C, Armstrong WS. An exploratory study to assess individual and structural level barriers associated with poor retention and re-engagement in care among persons living with HIV/AIDS. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2017;74(Suppl 2):S113–20. https://doi.org/10.1097/QAI.0000000000001242.

Gonzalez A, Barinas J, O’Cleirigh C. Substance use: impact on adherence and HIV medical treatment. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2011;8:223–34. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11904-011-0093-5.

Remien RH, Stirratt MJ, Nguyen N, Robbins RN, Pala AN, Mellins CA. Mental health and HIV/AIDS: the need for an integrated response. AIDS. 2019;33:1411–20. https://doi.org/10.1097/QAD.0000000000002227.

Katz IT, Ryu AE, Onuegbu AG, Psaros C, Weiser SD, Bangsberg DR, et al. Impact of HIV-related stigma on treatment adherence: systematic review and meta-synthesis. J Int AIDS Soc. 2013;16:18640. https://doi.org/10.7448/IAS.16.3.18640. [doi].

Geter A, Herron AR, Sutton MY. HIV-related stigma by healthcare providers in the United States: a systematic review. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2018;32:418–24. https://doi.org/10.1089/apc.2018.0114.

Geter A, Sutton MY, Hubbard McCree D. Social and structural determinants of HIV treatment and care among black women living with HIV infection: a systematic review: 2005–2016. AIDS Care - Psychological and Socio-Medical Aspects of AIDS/HIV. 2018;30:409–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540121.2018.1426827.

Aibibula W, Cox J, Hamelin AM, McLinden T, Klein MB, Brassard P. Association between food insecurity and HIV viral suppression: a systematic review and Meta-analysis. AIDS Behav. 2017;21:754–65. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-016-1605-5.

Filippone P, Serrano S, Campos S, Freeman R, Cluesman SR, Israel K, et al. Understanding why racial/ethnic inequities along the HIV care continuum persist in the United States: a qualitative exploration of systemic barriers from the perspectives of African American/Black and latino persons living with HIV. Int J Equity Health. 2023;22. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-023-01992-6.

Clemenzi-Allen A, Geng E, Christopoulos K, Hammer H, Buchbinder S, Havlir D, et al. Degree of housing instability shows independent dose-response with virologic suppression rates among people living with human immunodeficiency virus. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2018;5. https://doi.org/10.1093/ofid/ofy035.

Aidala AA, Lee G, Abramson DM, Messeri P, Siegler A. Housing need, housing assistance, and connection to HIV medical care. AIDS Behav. 2007;11. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-007-9276-x.

Haley DF, Golin CE, Farel CE, Wohl DA, Scheyett AM, Garrett JJ, et al. Multilevel challenges to engagement in HIV care after prison release: a theory-informed qualitative study comparing prisoners’ perspectives before and after community reentry. BMC Public Health. 2014;14. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-14-1253.

Iroh PA, Mayo H, Nijhawan AE. The HIV care cascade before, during, and after incarceration: a systematic review and data synthesis n.d. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.

Hazen E, Schlozman S, Beresin E. Adolescent psychological development: a review. Pediatr Rev. 2008;29:161–8. https://doi.org/10.1542/pir.29-5-161.

Chiaramonte D, Strzyzykowski T, Acevedo-Polakovich I, Miller RL, Boyer CB, Ellen JM. Ecological barriers to HIV service access among young men who have sex with men and high-risk young women from low-resourced urban communities. J HIV AIDS Soc Serv. 2018;17:313–33. https://doi.org/10.1080/15381501.2018.1502710.

Singer M. Poor; the perspective of critical medical anthropology. Pergamon. 1994;39. 0277–9536(93)EOO92-S.

Singer M, A dose of drugs, a touch of violence, a case of AIDS: conceptualizing the sava syndemic. Free Inq - Special Issue: Gangs Drugs Violence. 2000;28:13–24.

Singer M, Clair S. Syndemics and public health: reconceptualizing disease in bio-social context. Med Anthropol Q. 2003;17:423–41. https://doi.org/10.1525/maq.2003.17.4.423.

Kuhns LM, Hotton AL, Garofalo R, Muldoon AL, Jaffe K, Bouris A, et al. An index of multiple psychosocial, syndemic conditions is associated with antiretroviral medication adherence among HIV-positive youth. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2016;30:185–92. https://doi.org/10.1089/apc.2015.0328.

Sullivan KA, Messer LC, Quinlivan EB. Substance abuse, violence, and HIV/AIDS (SAVA) syndemic effects on viral suppression among HIV positive women of color. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2015;29:S42–8. https://doi.org/10.1089/apc.2014.0278.

Holloway IW, Beltran R, Shah SV, Cordero L, Garth G, Smith T et al. Structural Syndemics and Antiretroviral Medication Adherence Among Black Sexual Minority Men Living With HIV. 2021.

Harkness A, Bainter SA, O’Cleirigh C, Mendez NA, Mayer KH, Safren SA. Longitudinal effects of Syndemics on ART non-adherence among sexual minority men. AIDS Behav. 2018;22:2564–74. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-018-2180-8.

Mizuno Y, Purcell DW, Knowlton AR, Wilkinson JD, Gourevitch MN, Knight KR. Syndemic vulnerability, sexual and injection risk behaviors, and HIV Continuum of Care outcomes in HIV-Positive injection drug users. AIDS Behav. 2015;19:684–93. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-014-0890-0.

Friedman MR, Stall R, Silvestre AJ, Wei C, Shoptaw S, Herrick A, et al. Effects of syndemics on HIV viral load and medication adherence in the Multicentre AIDS cohort study. AIDS. 2015;29:1087–96. https://doi.org/10.1097/QAD.0000000000000657.

Blashill AJ, Bedoya CA, Mayer KH, O’Cleirigh C, Pinkston MM, Remmert JE, et al. Psychosocial syndemics are Additively Associated with worse ART adherence in HIV-Infected individuals. AIDS Behav. 2015;19:981–6. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-014-0925-6.

Satyanarayana S, Rogers BG, Bainter SA, Christopoulos KA, Fredericksen RJ, Mathews WC, et al. Longitudinal associations of Syndemic conditions with antiretroviral therapy adherence and HIV viral suppression among HIV-Infected patients in primary care. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2021;35:220–30. https://doi.org/10.1089/apc.2021.0004.

Wawrzyniak AJ, Rodríguez AE, Falcon AE, Chakrabarti A, Parra A, Park J et al. Association of individual and systemic barriers to optimal medical care in people living with HIV/AIDS in Miami-Dade county. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr (1988) 2015;69:S63–72. https://doi.org/10.1097/QAI.0000000000000572.

Dalenberg CJ, Glaser D, Alhassoon OM. Statistical support for subtypes in posttraumatic stress disorder: the how and why of subtype analysis. Depress Anxiety. 2012;29:671–8. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.21926.

Nylund-Gibson K, Choi AY. Ten frequently asked questions about latent class analysis. Transl Issues Psychol Sci. 2018;4:440–61. https://doi.org/10.1037/tps0000176.

Hotton AL, Perloff J, Paul J, Parker C, Ducheny K, Holloway T, et al. Patterns of exposure to Socio-structural stressors and HIV Care Engagement among Transgender women of Color. AIDS Behav. 2020;24:3155–63. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-020-02874-6.

Traynor SM, Schmidt RD, Gooden LK, Matheson T, Haynes L, Rodriguez A, et al. Differential effects of Patient Navigation across latent profiles of barriers to care among people living with HIV and Comorbid conditions. J Clin Med. 2023;12. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12010114.

Robinson AC, Knowlton AR, Gielen AC, Gallo JJ. Substance use, mental illness, and familial conflict non-negotiation among HIV-positive African-Americans: latent class regression and a new syndemic framework. J Behav Med. 2016;39:1–12. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10865-015-9670-1.

Horvath KJ, MacLehose RF, Martinka A, DeWitt J, Hightow-Weidman L, Sullivan P, et al. Connecting youth and young adults to optimize antiretroviral therapy adherence (YouTHrive): protocol for a Randomized Controlled Trial. JMIR Res Protoc. 2019;8:e11502. https://doi.org/10.2196/11502.

Earnshaw VA, Chaudoir SR. From conceptualizing to measuring HIV stigma: a review of HIV stigma mechanism measures. AIDS Behav. 2009;13:1160–77. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-009-9593-3.

Earnshaw VA, Smith LR, Chaudoir SR, Amico KR, Copenhaver MM. HIV stigma mechanisms and well-being among PLWH: a test of the HIV stigma framework. AIDS Behav. 2013;17:1785–95. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-013-0437-9.

Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:606–13. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x.

Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JBW, Löwe B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1092–7. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092.

Group WHOAW. The Alcohol, smoking and substance involvement screening test (ASSIST): development, reliability and feasibility. Addiction. 2002;97:1183–94. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1360-0443.2002.00185.x.

Akaike H. Factor analysis and AIC. Psychometrika. 1987;52:317–32.

Bozdogan H. Model selection and Akaike’s information criterion (AIC): the general theory and its analytical extensions. Psychometrika. 1987;52:345–70.

Banfield J, Raftery A. Model-based Gaussian and non-gaussian clustering. Biometrics. 1993;49:803–21.

Lo Y, Mendell NR, Rubin DB. Testing the number of components in a normal mixture. Biometrika. 2001;88:767–78.

McLachlan G, Peel D. Finite mixture models. New York: Wiley; 2000.

Schwarz G. Estimating the dimension of a model. Annals Stat. 1978;6:461–4.

Sclove SL. Application of model-selection criteria to some problems in multivariate analysis. Psychometrika. 1987;52:333–43.

Wagenmakers E. A practical solution to the pervasive problems of p values. Psychon Bull Rev. 2007;14:779–804.

Wasserman L. Bayesian model selection and model averaging. Mathematical Psychology Symposium on Methods for Model Selection, Bloomington, IN: 1997, pp. 1–17.

Collins LM, Schafer JL, Kam CM. A comparison of inclusive and restrictive strategies in modern missing data procedures. Psychol Methods. 2001;6:330–51.

Schafer JL, Graham JW. Missing data: our view of the state of the art. Psychol Methods. 2002;7:147–77.

Magidson J, Vermunt J. Latent class models. In: Kaplan D, editor. The sage handbook of quantitative methodology for the social sciences. Thousan Oaks, CA: Sage; 2005. pp. 175–98.

Asparouhov T, Muthen B. Auxiliary variables in mixture modeling: using the BCH Method in MPlus to Estimate a Distal Outcome Model and an arbitrary secondary model. Mplus; 2021.

Vermunt JK. Latent class modeling with covariates: two Improved three-step approaches. Political Anal. 2010;18:450–69.

Shokoohi M, Bauer GR, Kaida A, Logie CH, Lacombe-Duncan A, Milloy MJ, et al. Patterns of social determinants of health associated with drug use among women living with HIV in Canada: a latent class analysis. Addiction. 2019;114:1214–24. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.14566.

Liu Y, Ramos SD, Hanna DB, Jones DL, Lazar JM, Kizer JR, et al. Psychosocial syndemic classes and longitudinal transition patterns among sexual minority men living with or without HIV in the Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study (MACS). AIDS Behav. 2023;27:4094–105. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-023-04123-y.

Dawit R, Trepka MJ, Gbadamosi SO, Fernandez SB, Caleb-Adepoju SO, Brock P, et al. Latent class analysis of Syndemic Factors Associated with sustained viral suppression among Ryan White HIV/AIDS Program clients in Miami, 2017. AIDS Behav. 2021;25:2252–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-020-03153-0.

Tomczyk S, Isensee B, Hanewinkel R. Latent classes of polysubstance use among adolescents-a systematic review. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2016;160:12–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.11.035.

Vreeman RC, McCoy BM, Lee S. Mental health challenges among adolescents living with HIV. J Int AIDS Soc. 2017;20. https://doi.org/10.7448/IAS.20.4.21497.

Samji H, Wu J, Ladak A, Vossen C, Stewart E, Dove N, et al. Review: Mental health impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on children and youth – a systematic review. Child Adolesc Ment Health. 2022;27:173–89. https://doi.org/10.1111/camh.12501.

Gilliam PP, Ellen JM, Leonard L, Kinsman S, Jevitt CM, Straub DM. Transition of adolescents with HIV to Adult Care: characteristics and current practices of the Adolescent Trials Network for HIV/AIDS interventions. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2011;22:283–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jana.2010.04.003.

Wiener LS, Kohrt BA, Battles HB, Pao M. The HIV experience: Youth identified barriers for transitioning from pediatric to adult care. J Pediatr Psychol. 2011;36:141–54. https://doi.org/10.1093/jpepsy/jsp129.

Heard-Garris N, Boyd R, Kan K, Perez-Cardona L, Heard NJ, Johnson TJ. Structuring poverty: how racism shapes child poverty and child and adolescent health. Acad Pediatr. 2021;21:S108–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acap.2021.05.026.

Mallett CA. Disproportionate minority contact in juvenile justice: today’s, and yesterdays, problems. Criminal Justice Stud. 2018;31:230–48. https://doi.org/10.1080/1478601X.2018.1438276.

Jugl S, Okpeku A, Costales B, Morris EJ, Alipour-Haris G, Hincapie-Castillo JM, et al. A mapping literature review of Medical Cannabis Clinical outcomes and Quality of evidence in approved conditions in the USA from 2016 to 2019. Med Cannabis Cannabinoids. 2021;4:21–42. https://doi.org/10.1159/000515069.

Mannes ZL, Burrell LE, Ferguson EG, Zhou Z, Lu H, Somboonwit C, et al. The association of therapeutic versus recreational marijuana use and antiretroviral adherence among adults living with HIV in Florida. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2018;12:1363–72. https://doi.org/10.2147/PPA.S167826.

McKay MM, Chasse KT, Paikoff R, McKinney LD, Baptiste D, Coleman D, et al. Family-level impact of the CHAMP family program: a community collaborative effort to support urban families and reduce youth HIV risk exposure. Fam Process. 2004;43:79–93. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1545-5300.2004.04301007.x.

Bhana A, Mellins CA, Petersen I, Alicea S, Myeza N, Holst H, et al. The VUKA family program: piloting a family-based psychosocial intervention to promote health and mental health among HIV infected early adolescents in South Africa. AIDS Care - Psychol Socio-Medical Aspects AIDS/HIV. 2014;26:1–11. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540121.2013.806770.

Pardo G, Saisaengjan C, Gopalan P, Ananworanich J, Lakhonpon S, Nestadt DF, et al. Cultural Adaptation of an evidence-informed psychosocial intervention to address the needs of PHIV + youth in Thailand. Global Social Welf. 2017;4:209–18. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40609-017-0100-x.

Jaiswal J, Griffin-Tomas M, Singer SN, Lekas HM. Desire for patient-centered HIV Care among inconsistently engaged racial and ethnic minority people living with HIV. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2018;29:426–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jana.2018.01.001.

Byrd KK, Hardnett F, Clay PG, Delpino A, Hazen R, Shankle MD, et al. Retention in HIV Care among participants in the patient-centered HIV Care Model: a collaboration between community-based pharmacists and primary medical providers. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2019;33:58–66. https://doi.org/10.1089/apc.2018.0216.

Byrd KK, Hou JG, Bush T, Hazen R, Kirkham H, Delpino A, et al. Adherence and viral suppression among participants of the patient-centered human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) care model project: a collaboration between community-based pharmacists and HIV clinical providers. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;70:789–97. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciz276.

Saberi P, Mccuistian C, Agnew E, Wootton AR, Legnitto Packard DA, Dawson-Rose C, et al. Video-Counseling intervention to address HIV Care Engagement, Mental Health, and Substance Use challenges: a pilot randomized clinical trial for youth and young adults living with HIV. Telemed Rep. 2021;2:14–25. https://doi.org/10.1089/tmr.2020.0014.

Saberi P, Dawson Rose C, Wootton AR, Ming K, Legnitto D, Jeske M, et al. Use of technology for delivery of mental health and substance use services to youth living with HIV: a mixed-methods perspective. AIDS Care - Psychol Socio-Medical Aspects AIDS/HIV. 2020;32:931–9. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540121.2019.1622637.

Sayegh CS, MacDonell KK, Clark LF, Dowshen NL, Naar S, Olson-Kennedy J, et al. The impact of cell phone support on Psychosocial outcomes for Youth living with HIV Nonadherent to Antiretroviral Therapy. AIDS Behav. 2018;22:3357–62. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-018-2192-4.

Safren SA, Harkness A, Lee JS, Rogers BG, Mendez NA, Magidson JF, et al. Addressing Syndemics and Self-care in individuals with uncontrolled HIV: an Open Trial of a Transdiagnostic treatment. AIDS Behav. 2020;24:3264–78. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-020-02900-7.

Department of Housing and Urban Development. Housing Opportunities for Persons With AIDS. Https://Www.Hudexchange.Info/Programs/Hopwa/ 2024.

Department of Labor. Youth Programs and Services. Https://Www.Dol.Gov/Agencies/Eta/Youth 2024.

Bosma CB, Toromo JJ, Ayers MJ, Foster ED, McHenry MS, Enane LA. Effects of economic interventions on pediatric and adolescent HIV care outcomes: a systematic review. AIDS Care - Psychol Socio-Medical Aspects AIDS/HIV. 2024;36:1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540121.2023.2240071.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health Adolescent Medicine Trials Network for HIV/AIDS Interventions (ATN 138; MPI: Horvath & Amico) as part of the UNC/Emory Center for Innovative Technology (iTech; principal investigators: Dr Hightow-Weidman/Sullivan, 1U19HD089881). In addition, JMW received support from T32DA023356. The funders had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; or decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics Approval and Consent

This study is registered as a clinical trial (Clinical Trials # NCT03149757) and was approved by the institutional review board at the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill; parental consent was waived for participants aged 15–17 years.

Competing Interests

The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wiginton, J.M., Amico, K.R., Hightow-Weidman, L. et al. Syndemic Psychosocial Conditions among Youth Living with HIV: a Latent Class Analysis. AIDS Behav (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-024-04427-7

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-024-04427-7