Abstract

South Africa has the largest share of people living with HIV in the world and this population is ageing. The social context in which people seek HIV care is often ignored. Apart from clinical interventions, socio-behavioural factors impact successful HIV care outcomes for older adults living with HIV. We use cross-sectional data linked with demographic household surveillance data, consisting of HIV positive adults aged above 40, to identify socio-behavioural predictors of a detectable viral load. Older adults were more likely to have a detectable viral load if they did not disclose their HIV positive status to close family members (aOR 2.56, 95% CI 1.89-3.46), resided in the poorest households (aOR 1.98, 95% CI 1.23-3.18), or were not taking medications other than ART (aOR 1.83, 95% CI 1.02-1.99) likely to have a detectable. Clinical interventions in HIV care must be supported by understanding the socio-behavioural barriers that occur outside the health facility. The importance of community health care workers in bridging this gap may offer more optimum outcomes for older adults ageing with HIV.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The population of people living with HIV (PLHIV) in South Africa is aging. In 2012, HIV prevalence among individuals aged 50 years and older was 7.6%, which doubled in 2022 and is estimated to be > 22% by the end of 2030 [1,2,3]. This trend in aging with HIV is driven in part by widespread access to antiretroviral therapy (ART) that has transformed HIV into a chronic disease. There is robust evidence that early ART initiation has important impacts on health, especially as people age [4,5,6,7]. The third UNAIDS 95-95-95 target of viral suppression also hinges upon successful HIV management. Sustained viral suppression and continuous retention in care help to improve the quality of life amongst PLHIV [8, 9].

There are several studies that have looked at socio-behavioural barriers to viral suppression among vulnerable groups [10,11,12,13]. However, there are limited studies to understand how older adults in rural South Africa fare in terms of viral suppression and the socio-behavioural barriers which may impact the achievement of viral suppression. Although older adults have higher rates of viral suppression compared to the younger age-groups in South Africa, rates are still below the UNAIDS targets of 95%, with women being more virally suppressed than men [1, 2, 14].

HIV prevalence for adults aged between 15 and 49 is higher in urban areas than rural areas [15, 16]. As people age, they may migrate to the rural areas [17], where structural and patient-level barriers to optimal HIV care may be different compared to those in the urban areas [18, 19]. The rural setting in sub-Saharan Africa is often associated with limited economic opportunities and a lack of a retirement cushion in old age, which can have implications for retention in care [20]. Previous studies have reported barriers to viral suppression including low wealth, internal stigma, distance from the health facility, low educational attainment, and lack of geographic mobility [13, 21]. Socio-behavioural attributes for PLHIV may help us to understand why some individuals are virally suppressed or not. Retention in HIV care has been shown to be more difficult in rural compared with urban residences [22]; and also in households with lower socio-economic status [23]. Health behaviours have also been found in other studies to impact HIV care, including smoking and diet [24]. Social and behavioural factors may play an important role in the way older PLHIV manage their HIV care [25, 26].

In this study, we examined socio-behavioural factors associated with viral suppression amongst older PLHIV in a rural area of north-eastern South Africa, to identify barriers to successful long-term HIV management.

Methods

Study Population and Data

We used cross-sectional data from the Health and Aging in Africa: A Longitudinal Study of an INDEPTH community in South Africa (HAALSI). This study is a population-based survey focusing on men and women aged 40 years and older. The survey collects information on aging including health, physical and cognitive function, cardiometabolic health, economic well-being and HIV. The study population was nested within the Agincourt Health and socio-demographic surveillance system (HDSS) located in the rural north-eastern part of South Africa in Mpumalanga. The primary data used for this analysis came from two sources: data from HAALSI Wave 1 collected in 2015 and linked data from the Agincourt HDSS census on individual and household characteristics.

In total 5059 participants were included in the HAALSI baseline survey, 93% of whom consented to dry blood spot (DBS) biomarker testing in baseline survey. The survey and biomarker data were collected during in-person interviews by trained local fieldworkers using Computer Assisted Personal Interviews. Fieldworkers collected blood via finger prick and prepared DBS to assess participants’ HIV status, presence of ART in the bloodstream and viral load. HIV screening and confirmatory enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA) were done using the Vironostika HIV 1/2 Ag/Ab MicroELISA System (BioMérieux, Marcy-l’Étoile, France) and the Roche CobasE411 Combi Ag, respectively [27]. The Viral Load Platform was Biomeriux NucliSens with a lower detection limit of < 100 copies by DBS. Our study was limited to participants who tested HIV positive and had a valid viral load measurement.

Ethical approvals for the study were granted from the University of the Witwatersrand Human Research Ethics Committee (ref. M141159), the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Office of Human Research Administration (ref. C13–1608–02) and the Mpumalanga Provincial Research and Ethics Committee. Data for HAALSI is available upon request through the Harvard Dataverse repository.

Study Variables

We defined viral suppression as a measure of ≤ 1000 copies/mL from DBS [28]. We obtained socio-demographic information including sex, marital status and age. From the HAALSI baseline survey, we also used self-reported disclosure of HIV status to close family members, self-reported use of herbal medication and self-reported medications usage. Self-reported disclosure of HIV status to family members was aggregated by combining questions on disclosure of status to siblings, spouse, parents or any other family members. The use of herbal medication was self-reported for several conditions including hypertension, diabetes, tuberculosis (TB), HIV, stroke and pain. We included self-reported current use of medications for TB, hypertension, diabetes, stroke, heart failure and chest pain to determine polypharmacy.

Household size, household access to government grants, socio-economic status and household road distance to the nearest health care facility were obtained from the linked Agincourt HDSS data. Socio-economic status (wealth index) was derived from a standard aggregation of construction materials of the main dwelling, type of toilet facilities, sources of water and energy, ownership of modern assets and livestock, employing the same methodology as implemented in the Demographic and Health Surveys [29, 30].

Analysis

Viral suppression was the main outcome variable. We used the chi-2 test to assess if there was an association between viral suppression and participants’ demographic and socio-behavioural characteristics. We additionally employed logistic regression to examine the strength of the relationships between viral suppression and demographic as well as socio-behavioural attributes. The contextual variables and the adapted conceptual framework to guide this study are shown in Supplementary Information Figure I [31]. We used STATA version 14.2 for this analysis.

A sensitivity analysis was conducted to assess whether the results were influenced by viral load cut-off point and restricting to participants who were aware of their HIV positive status (Supplementary Information Table I and II). We used a cut-off of 200 copies/mL. Knowledge of HIV positive status was determined by either self-reporting of being HIV positive or ART being detected in the blood at the time of the study.

Results

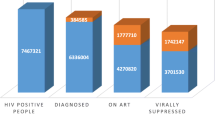

The prevalence of HIV was 23% (n = 1048). We obtained 1044 valid viral load values from the DBS results (Supplementary Information Figure II). Overall, 70% of the PLHIV had an undetectable viral load. The descriptive and bivariate analyses showing differences in viral suppression results and socio-behavioural characteristics are shown in Table 1. We found a significant association between viral suppression and various factors, including household size, socio-economic status, households receiving any state grant, household members’ awareness of an individual’s HIV status and polypharmacy. The odds of viral suppression were lowest in single-person households. Those with the lowest socio-economic status were less likely to achieve viral suppression than individuals in higher socio-economic groups. Failure to disclose HIV status to close family members was associated with a lower likelihood of viral suppression compared to those who had disclosed their status. Households not receiving any state grant were less likely to achieve viral suppression than those receiving one. Individuals solely on ART without additional medication were less likely to achieve viral suppression compared to those taking medication for at least one other condition besides HIV.

In the adjusted model for logistic regression, individuals in households with more than eight members had twice the odds of having a detectable viral load compared to those with a household size of between five and seven members (Table 2). Individuals living in households with the lowest socio-economic status had twice the odds of having a detectable viral load compared to those residing in households with higher socio-economic status. Respondents who reported that their close family members were unaware of their status had 2.6 times the odds of having a detectable viral load compared to those whose family members were aware of their HIV positive status. Disclosure to close family members had the strongest association in the adjusted model. Individuals solely taking ART without any additional medication had 43% higher odds of having a detectable viral load compared to those taking medication for at least one other condition besides HIV.

In the sensitivity analysis, when a lower viral suppression threshold was applied and when restricted to individuals who were aware of their HIV positive status, we found that PLHIV who were not using any herbal medication at the time of the study were significantly more likely to have a detectable viral load compared to those using herbal medication (Supplementary information Table I and II).

Discussion

The study helps us understand why the setting underlying HIV clinical care is important in improving health outcomes and attaining better quality of life among older PLHIV. We were interested in understanding how socio-behavioural characteristics were associated with lower viral suppression outcomes for older PLHIV within the rural context of South Africa. We found that being male, aged between 40 and 49 years, and failing to disclose HIV status to close family members, were associated with detectable viral load. Additionally, larger and poor households and those not taking medication for other comorbid conditions apart from HIV were more vulnerable to lower suppression rates.

Our study provides additional evidence of lower suppression rates for males than females [1, 14, 32, 33]. Women often interact with the health care system more than men. This may be partly because women have unique health needs, such as reproductive health, and are more likely to seek preventive care [34]. In the context of HIV, prevailing notions of masculinity may act as obstacles to men accessing health care facilities [35]. Our youngest age group of older adults in this study, those aged between 40 and 49 years, were at the highest risk of not being virally suppressed. It is likely they may have been newly infected and may have taken longer to transition into HIV care, especially for the men [2, 36, 37]. Conversely, it may be due to selection effects of mortality in the higher age groups, those that are older and virally unsuppressed may have died [7].

The most significant factor contributing to an unsuppressed viral load was the failure to disclose one’s HIV status to close family members. Similar to a study in rural Uganda, non-disclosure of HIV status to other household members may hinder viral suppression amongst those older PLHIV [18]. This is more likely linked to fear that close family members will reject them once they reveal their HIV positive status. Similar findings also highlight the association between HIV care and internalised stigma [38,39,40,41]. Internalised stigma has been found in other studies to be associated with depression and other mental health issues [42,43,44]. Disclosure to close family members may help in strengthening HIV care interventions through the provision of emotional and in some cases financial support within the household [45,46,47]. The HIV care and treatment programs should also consider approaches to HIV care that may help PLHIV towards addressing some of the fears that inhibit them from sharing their status to close family members.

The study found that poverty was a barrier to attaining viral suppression. Other studies have found this to be related to costs incurred by patients in accessing the health care facility [48]. However, in this study, they are likely due to other factors since health care services are mostly in proximity and there is free access to community clinics. The effect of poverty has been linked to food security and inadequate nutrition in other studies [49,50,51]. This effect may be exaggerated in larger, inter-generational households due to the difficulty in prioritizing of scarce resources within the household. Inter-generational households have existed since apartheid mainly due to labour migration from tribal homelands. Parents would leave their children with grandparents in their care while they worked in urban areas [52]. The impact of HIV morbidity and mortality has also increased the number of inter-generational households [53, 54], as well increased unemployment in South Africa [55, 56]. The increase in unemployment may particularly force an increase in inter-generational households due to greater dependency on older members of the households. This may also aggravate challenges to health care utilization among older adults due to the prioritisation of resources elsewhere within the household.

Polypharmacy shows extended benefits for viral suppression which is likely a reflection of HIV care utilization, particularly for comorbidities which are monitored within the standard health care protocol [57, 58]. In the rural South African context, where herbal medicines are commonly used, it was intriguing to discover that individuals who supplemented ART with herbal medication experienced better outcomes than those who did not use herbal medications. These findings are unique in the context of rural care-seeking behaviour among older PLHIV. In other contexts, herbal medications are often taken for enhancing immunity and managing opportunistic infections among PLHIV [59, 60]. On the other hand, some studies found no clinical improvement in some herbal interventions and clinicians discourage concomitant use of traditional medicines with ART due to unfavourable effects of the medication interactions [61, 62]. The difference observed could also be a result of health seeking behaviour amongst those that use herbal medication. It may need further study to identify whether this is an effect resulting from better health awareness or the clinical impact of herbal medication.

In rural areas of South Africa, strong family and community bonds exist, and reducing internalised stigma will not only encourage individuals to seek family support for HIV-related health issues but will also extend support to those around the community. The findings underscore the necessity for integrated strategies to address internalised stigma among older individuals living with HIV. Such approaches not only enhance family support but also mitigate the mental health burden associated with internalized stigma. This will provide a holistic approach to both clinical and socio-behavioral well-being of older PLHIV. Expanding HIV programs with social workers and community health care workers within the rural communities may assist in this effort.

Conclusion

While acknowledging its limitations, including the inability to establish causality from associations, this study sheds light on socio-behavioral barriers to HIV care frequently faced by older PLHIV. The research contributes to our comprehension of these socio-behavioral obstacles, which are crucial for achieving the UNAIDS 95-95-95 targets for viral suppression. These barriers are often overlooked in the clinical realm of HIV care. It is important to note that the study’s findings may not be broadly applicable to PLHIV in South Africa but may be a representation of rural South Africa. Collaborative efforts between community health care workers and practitioners are essential for strengthening initiatives aimed at enhancing HIV care outcomes and ensuring inclusivity. Integrating social and behavioral considerations into HIV care and treatment programs is imperative for reinforcing health policies. As the HIV population in South Africa continues to age due to improved access to ART, these findings provide valuable insights for guiding updates in future HIV care policies.

References

Human Sciences Research Council (HSRC). The Sixth South African National HIV Prevalence, incidence, Behaviour and Communication Survey, 2022: HIV Impact Assessment Summary Report. Cape Town 2023.https://hsrc.ac.za/special-projects/sabssm-survey-series/sabssmvi-media-pack-november-2023/ [2023/12/15].

Shisana O, Rehle T, Simbayi LC, Zuma K, Jooste S, Zungu N, Labadarios D, Onoya D. South African National HIV Prevalence, Incidence and Behaviour Survey Cape Town 2012.

Johnson L, Dorrington R. Thembisa version 4.6: A model for evaluating the impact of HIV/AIDS in South Africa 2023.

Pimentel GS, Ceccato MGB, Costa JO, Mendes JC, Bonolo PF, Silveira MR. Quality of life in individuals initiating antiretroviral therapy: a cohort study. Rev Saude Publica 2020;54.

Xie Y, Zhu J, Lan G, Ruan Y. Benefits of early ART initiation on mortality among people with HIV. Lancet HIV. 2022;9(6):e377.

Ford N, Migone C, Calmy A, Kerschberger B, Kanters S, Nsanzimana S, Mills EJ, Meintjes G, Vitoria M, Doherty M. Benefits and risks of rapid initiation of antiretroviral therapy. AIDS. 2018;32(1):17.

Payne CF, Houle B, Chinogurei C, Herl CR, Kabudula CW, Kobayashi LC, Salomon JA, Manne-Goehler J. Differences in healthy longevity by HIV status and viral load among older South African adults: an observational cohort modelling study. Lancet HIV. 2022;9(10):e709–16.

Cohen MS, Chen YQ, McCauley M, Gamble T, Hosseinipour MC, Kumarasamy N, Hakim JG, Kumwenda J, Grinsztejn B, Pilotto JH. Prevention of HIV-1 infection with early antiretroviral therapy. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(6):493–505.

Gill CJ, Griffith JL, Jacobson D, Skinner S, Gorbach SL, Wilson IBJJJAIDS. Relationship of HIV viral loads, CD4 counts, and HAART use to health-related quality of life. 2002;30(5):485–92.

Tomita A, Vandormael A, Bärnighausen T, Phillips A, Pillay D, De Oliveira T, Tanser F. Sociobehavioral and community predictors of unsuppressed HIV viral load: multilevel results from a hyperendemic rural South African population. J AIDS. 2019;33(3):559.

Woldesenbet SA, Kufa T, Barron P, Chirombo BC, Cheyip M, Ayalew K, Lombard C, Manda S, Diallo K, Pillay Y. Viral suppression and factors associated with failure to achieve viral suppression among pregnant women in South Africa. J AIDS. 2020;34(4):589.

Ntombela NP, Kharsany AB, Soogun A, Yende-Zuma N, Baxter C, Kohler H-P, McKinnon LR. Viral suppression among pregnant adolescents and women living with HIV in rural KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa: a cross sectional study to assess progress towards UNAIDS indicators and implications for HIV Epidemic Control. Reproductive Health. 2022;19(1):116.

Plymoth M, Sanders EJ, Van Der Elst EM, Medstrand P, Tesfaye F, Winqvist N, Balcha T, Björkman P. Socio-economic condition and lack of virological suppression among adults and adolescents receiving antiretroviral therapy in Ethiopia. PLoS ONE. 2020;15(12):e0244066.

Marinda E, Simbayi L, Zuma K, Zungu N, Moyo S, Kondlo L, Jooste S, Nadol P, Igumbor E, Dietrich C, Briggs-Hagen M. Towards achieving the 90-90-90 HIV targets: results from the South African 2017 national HIV survey. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1):1375. 2020/09/09.

Kleinschmidt I, Pettifor A, Morris N, MacPhail C, Rees H, editors. hygiene. Geographic distribution of human immunodeficiency virus in South Africa. The American journal of tropical medicine 2007;77(6):1163.

Gibbs A, Reddy T, Dunkle K, Jewkes R. HIV-Prevalence in South Africa by settlement type: a repeat population-based cross-sectional analysis of men and women. PLoS ONE. 2020;15(3):e0230105.

Zimmer Z, Dayton J. Older adults in sub-saharan Africa living with children and grandchildren. Popul Stud. 2005;59(3):295–312.

Bajunirwe F, Arts E, Tisch D, King C, Debanne S, Sethi A. Adherence and treatment response among HIV-1-infected adults receiving antiretroviral therapy in a rural government hospital in Southwestern Uganda. J Int Association Physicians AIDS Care. 2009;8(2):139–47.

Pellowski JA. Barriers to care for rural people living with HIV: a review of domestic research and health care models. J Association Nurses AIDS Care: JANAC Sep-Oct. 2013;24(5):422–37.

Du Toit A. Explaining the persistence of rural poverty in South Africa. Paper presented at: Report presented to the Expert Group Meeting on Eradicating Rural Poverty to Implement the2017.

Haider MR, Brown MJ, Harrison S, Yang X, Ingram L, Bhochhibhoya A, Hamilton A, Olatosi B, Li X. Sociodemographic factors affecting viral load suppression among people living with HIV in South Carolina. AIDS Care. 2021;33(3):290–8.

Banerjee S. Determinants of rural-urban differential in healthcare utilization among the elderly population in India. BMC Public Health. 2021;21(1):1–18.

Sheehan DM, Fennie KP, Mauck DE, Maddox LM, Lieb S, Trepka MJ. Retention in HIV Care and viral suppression: individual- and Neighborhood-Level predictors of Racial/Ethnic differences, Florida, 2015. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2017;31(4):167–75.

Althoff K, Palella F, Gebo K. Impact of smoking, hypertension, and cholesterol on myocardial infarction in HIV-infected adults (abstract 130). Paper presented at: Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections, Seattle, WA2017.

Becker N, Cordeiro LS, Poudel KC, Sibiya TE, Sayer AG, Sibeko LN. Individual, household, and community level barriers to ART adherence among women in rural Eswatini. PLoS ONE. 2020;15(4):e0231952.

Holtzman CW, Shea JA, Glanz K, Jacobs LM, Gross R, Hines J, Mounzer K, Samuel R, Metlay JP, Yehia BR. Mapping patient-identified barriers and facilitators to retention in HIV care and antiretroviral therapy adherence to Andersen’s behavioral model. AIDS Care. 2015;27(7):817–28.

Rohr JK, Xavier Gómez-Olivé F, Rosenberg M, Manne‐Goehler J, Geldsetzer P, Wagner RG, Houle B, Salomon JA, Kahn K, Tollman S. Performance of self‐reported HIV status in determining true HIV status among older adults in rural South Africa: a validation study. J Int AIDS Soc. 2017;20(1):21691.

National Department of Health South Africa. National Consolidated Guidelines for the prevention of mother-to-chid transmission of HIV (PMTCT) and the management of HIV in children, adolescents and adults. Pretoria: National Department of Health; 2015.

Kabudula CW, Houle B, Collinson MA, Kahn K, Tollman S, Clark S. Assessing changes in household socioeconomic status in rural South Africa, 2001–2013: a distributional analysis using household asset indicators. Soc Indic Res. 2017;133(3):1047–73.

Rutstein SO, Johnson K. DHS comparative reports 6: the DHS wealth index. Maryland, USA: Calverton; 2004.

Solar O, Irwin A. A conceptual framework for action on the social determinants of health. Social Determinants of Health Discussion Paper 2 (Policy and Practice). Geneva: World Health Organization,; 2010.

Kipp W, Alibhai A, Saunders LD, Senthilselvan A, Kaler A, Konde-Lule J, Okech-Ojony J, Rubaale T. Gender differences in antiretroviral treatment outcomes of HIV patients in rural Uganda. AIDS Care. 2010;22(3):271–8.

Beer L, Mattson CL, Bradley H, Skarbinski J. Understanding cross-sectional racithnic, and gender disparities in antiretroviral use and viral suppression among HIV patients in the United States. J Med 2016;95(13).

Pinkhasov RM, Wong J, Kashanian J, Lee M, Samadi DB, Pinkhasov MM, Shabsigh R. Are men shortchanged on health? Perspective on health care utilization and health risk behavior in men and women in the United States. Int J Clin Pract. 2010;64(4):475–87.

Vanable PA, Carey MP, Blair DC, Littlewood RA. Impact of HIV-related stigma on health behaviors and psychological adjustment among HIV-positive men and women. AIDS Behav. 2006;10:473–82.

Cornell M, Myer L. Does the success of HIV treatment depend on gender? Future Microbiol. 2013;8(1):9–11.

Sempa JB, Kiragga AN, Castelnuovo B, Kamya MR, Manabe YC. Among patients with sustained viral suppression in a resource-limited setting, CD4 gains are continuous although gender-based differences occur. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(8):e73190.

Rice WS, Burnham K, Mugavero MJ, Raper JL, Atkins GC, Turan B. Association between internalized HIV-related stigma and HIV care visit adherence. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2017;76(5):482.

Kingori C, Reece M, Obeng S, Murray M, Shacham E, Dodge B, Akach E, Ngatia P, Ojakaa D, STDs. Impact of internalized stigma on HIV prevention behaviors among HIV-infected individuals seeking HIV care in Kenya. AIDS Patient Care. 2012;26(12):761–8.

Denison JA, Burke VM, Miti S, Nonyane BA, Frimpong C, Merrill KG, Abrams EA, Mwansa JK. Project YES! Youth Engaging for Success: a randomized controlled trial assessing the impact of a clinic-based peer mentoring program on viral suppression, adherence and internalized stigma among HIV-positive youth (15–24 years) in Ndola, Zambia. PLoS ONE. 2020;15(4):e0230703.

Esber A, Dear N, Reed D, Bahemana E, Owouth J, Maswai J, Kibuuka H, Iroezindu M, Crowell TA, Polyak CS. Temporal trends in self-reported HIV stigma and association with adherence and viral suppression in the African cohort study. AIDS Care. 2022;34(1):78–85.

MacLean JR, Wetherall K. The association between HIV-stigma and depressive symptoms among people living with HIV/AIDS: a systematic review of studies conducted in South Africa. Ournal Affect Disorders. 2021;287:125–37.

Zeng C, Li L, Hong YA, Zhang H, Babbitt AW, Liu C, Li L, Qiao J, Guo Y, Cai W. A structural equation model of perceived and internalized stigma, depression, and suicidal status among people living with HIV/AIDS. BMC Public Health. 2018;18:1–11.

Fekete EM, Williams SL, Skinta MD. Health. Internalised HIV-stigma, loneliness, depressive symptoms and sleep quality in people living with HIV. Psychol Health. 2018;33(3):398–415.

Ssali SN, Atuyambe L, Tumwine C, Segujja E, Nekesa N, Nannungi A, Ryan G, Wagner G. Reasons for Disclosure of HIV Status by People Living with HIV/AIDS and in HIV Care in Uganda: an exploratory study. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2010;24(10):675–81.

Shato T, Nabunya P, Byansi W, Nwaozuru U, Okumu M, Mutumba M, Brathwaite R, Damulira C, Namuwonge F, Bahar OS. Family economic empowerment, Family Social Support, and sexual risk-taking behaviors among adolescents living with HIV in Uganda: the suubi + adherence study. J Adolesc Health. 2021;69(3):406–13.

Silva LMSd, Tavares JSC. The family’s role as a support network for people living with HIV/AIDS: a review of Brazilian research into the theme. Ciência Saúde Coletiva. 2015;20:1109–18.

McLaren ZM, Ardington C, Leibbrandt M. Distance decay and persistent health care disparities in South Africa. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14(1):1–9.

Chop E, Duggaraju A, Malley A, Burke V, Caldas S, Yeh PT, Narasimhan M, Amin A, Kennedy CE. Food insecurity, sexual risk behavior, and adherence to antiretroviral therapy among women living with HIV: a systematic review. Health Care Women Int. 2017;38(9):927–44.

Young S, Wheeler AC, McCoy SI, Weiser SD. A review of the role of food insecurity in adherence to care and treatment among adult and pediatric populations living with HIV and AIDS. AIDS Behav. 2014;18(5):505–15.

Poku RA, Owusu AY, Mullen PD, Markham C, McCurdy SA. Antiretroviral therapy maintenance among HIV-positive women in Ghana: the influence of poverty. AIDS Care. 2020;32(6):779–84.

Makiwane M. The changing patterns of intergenerational relations in South Africa. Paper presented at: Expert Group Meeting,Dialogue and Mutual Understanding across Generations, convened in observance of the International Year of Youth2010.

Ardington C, Case A, Islam M, Lam D, Leibbrandt M, Menendez A, Olgiati A. The impact of AIDS on intergenerational support in South Africa: evidence from the Cape Area Panel Study. Res Aging. 2010;32(1):97–121.

Merli MG, Palloni A. The HIV/AIDS epidemic, kin relations, living arrangements, and the African elderly in South Africa. Aging sub-Saharan Africa: Recommendations Furthering Res 2006:117–65.

Trading Economics. South Africa Unemployment Rate 2000–2020 Data. 2021; https://tradingeconomics.com/south-africa/unemployment-rate. Accessed 19/03/2021, 2021.

Magruder JR. Intergenerational networks, unemployment, and persistent inequality in South Africa. Am Economic Journal: Appl Econ. 2010;2(1):62–85.

Manne-Goehler J, Montana L, Gómez-Olivé FX, Rohr J, Harling G, Wagner RG, Wade A, Kabudula CW, Geldsetzer P, Kahn K. The ART advantage: healthcare utilization for diabetes and hypertension in rural South Africa. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2017;75(5):561.

National Department of Health SA. Adherence guidelines for HIV, TB and NCD’s. National Department of Health; 2016. https://www.nacosa.org.za/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/Integrated-Adherence-Guidelines-NDOH.pdf. [2022/04/15]. South Africa.

Monera TG, Maponga CC. Prevalence and patterns of Moringa oleifera use among HIV positive patients in Zimbabwe: a cross-sectional survey. J Public Health Afr 2012;3(1).

Popoola JO. Obembe OOJJoe. Local knowledge, use pattern and geographical distribution of Moringa oleifera Lam.(Moringaceae). Nigeria. 2013;150(2):682–91.

Monera-Penduka TG, Maponga CC, Wolfe AR, Wiesner L, Morse GD, Nhachi CF, editors. therapy. Effect of Moringa oleifera Lam. leaf powder on the pharmacokinetics of nevirapine in HIV-infected adults: a one sequence cross-over study. AIDS research 2017;14(1):1–7.

Awortwe C, J Bouic P, Masimirembwa M, Rosenkranz C. Inhibition of major drug metabolizing CYPs by common herbal medicines used by HIV/AIDS patients in Africa–implications for herb-drug interactions. Drug Metab Lett. 2013;7(2):83–95.

Funding

Open access funding provided by University of Cape Town.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

There are no relevant financial or non-financial competing interests to report.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chinogurei, C., Manne-Goehler, J., Kahn, K. et al. Socio-Behavioural Barriers to Viral Suppression in the Older Adult Population in Rural South Africa. AIDS Behav 28, 2307–2313 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-024-04328-9

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-024-04328-9