Abstract

Low- and middle-income countries are facing a growing burden of noncommunicable diseases (NCDs). Providing HIV treatment may provide opportunities to increase access to NCD services in under-resourced environments. We conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis to evaluate whether use of antiretroviral therapy (ART) was associated with increased screening, diagnosis, treatment, and control of diabetes, hypertension, chronic kidney disease, or cardiovascular disease among people living with HIV in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA). A comprehensive search of electronic literature databases for studies published between 01 January 2011 and 31 December 2022 yielded 26 studies, describing 13,570 PLWH in SSA, 61% of whom were receiving ART. Random effects models were used to calculate summary odds ratios (ORs) of the risk of diagnosis by ART status and corresponding 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs), where appropriate. ART use was associated with a small but imprecise increase in the odds of diabetes diagnosis (OR 1.07; 95% CI 0.71, 1.60) and an increase in the odds of hypertension diagnosis (OR 2.10, 95% CI 1.42, 3.09). We found minimal data on the association between ART use and screening, treatment, or control of NCDs. Despite a potentially higher NCD risk among PLWH and regional efforts to integrate NCD and HIV care, evidence to support effective care integration models is lacking.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The prevalence of noncommunicable diseases (NCDs) is on the rise globally [1, 2]. In low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), the disease burden has already shifted from predominantly infectious diseases to predominantly NCDs [3, 4]. By 2030, NCDs are expected to account for nearly 46% of deaths in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), compared to 28% in 2008 [5,6,7]. In SSA, where there is already a heavy burden of HIV and other communicable diseases, this creates a challenging multimorbidity disease environment. Co-existence of HIV with one or more NCDs, such as type 2 diabetes mellitus (diabetes) or hypertension, increases the complexity of patients’ disease and care management profile, contributing to poorer health outcomes and increased health care costs for both the individual and the country [8,9,10].

People living with HIV (PLWH) may be at increased risk for NCDs. Antiretroviral therapy (ART) has resulted in a decrease in HIV infections and an increase in the lifespan of PLWH [11, 12]. However, chronic inflammation as a result of long-term HIV infection is associated with an increased risk of chronic conditions, including chronic kidney disease (CKD) and cardiovascular disease (CVD) [13, 14]. Moreover, emerging data have demonstrated substantial weight gain associated with newer ART regimens, such as integrase-strand-transfer-inhibitors [15,16,17]. As overweight and obesity are known risk factors for numerous NCDs, including hypertension, diabetes, and CVD [18, 19], this ART-associated weight gain could result in an increase of NCD rates in this population.

Though HIV infection and ART use may contribute to increases in NCD risk, the HIV care structure may provide a gateway to improve rates of detection and treatment of NCDs among PLWH. Routine NCD screening among healthy, asymptomatic adults in SSA is not common [20]. Traditionally, however, PLWH on ART have been required to present to a clinic monthly for the first 6 months after ART initiation and then at least every 3 or 6 months once stable in order to obtain their medications [21]. ART guidelines typically include collection of data on blood glucose and urine protein at treatment initiation as well as routine collection of data on weight and blood pressure [22,23,24]. This increased contact with the healthcare system could increase the likelihood of NCD diagnosis, treatment, and control among PLWH. The purpose of this report was to investigate whether reported use of ART was associated with increased screening, diagnosis, treatment, and/or control of four common NCDs – diabetes, hypertension, CKD, and CVD – among PLWH in SSA, a region with an estimated 28.7 million people prescribed ART and engaged in care [25].

Methods

Search Strategy and Selection Criteria

The protocol for this meta-analysis was registered with PROSPERO (CRD42021290283). To conduct the systematic review, we ran comprehensive searches on 3 electronic literature databases (PubMed, EMBASE, Web of Science) and 7 conference proceedings archives (Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections (CROI), International AIDS Society (IAS), International Diabetes Federation World Congress, American Diabetes Association, American Heart Association Scientific Sessions, Hypertension Scientific Sessions, Kidney Week). Articles and abstracts published between 01 January 2011 and 31 December 2022 that reported outcomes among non-pregnant adults ≥ 16 years of age with HIV in SSA were included for review. We further applied snowball sampling methods to articles selected for review [26].

Titles and abstracts of search results were imported into Covidence systematic review software [27] and screened independently by two reviewers (E.M.K and A.Z). A senior reviewer (A.T.B.) resolved any discrepancies. Titles and abstracts that contained potentially relevant information were identified and selected for full-text review. Articles or abstracts that reported on the prevalence of screening, diagnosis, or treatment by ART status of a least one disease of interest and did not meet any exclusion criteria (Supplemental Table 2), were selected for data extraction. Quality of studies was assessed using The Joanna Briggs Institute Critical Appraisal Tools for analytical cross-sectional studies [28]. Eight questions were used to evaluate the quality of each individual study, with the options of “yes”, “no”, “unclear”, or “not applicable”. We assigned values to the response options to obtain an overall quality score.

Exposure

The exposure of interest in this review was reported ART use (versus no reported ART use) among non-pregnant adults with HIV in SSA.

Outcomes

Outcomes of interest were:

-

(1)

self-reported screening or documentation of laboratory test for diabetes, hypertension, CKD, or cardiovascular disease;

-

(2)

self-reported or clinical diagnosis based on study criteria of diabetes, hypertension, CKD, or cardiovascular disease;

-

(3)

self-reported or clinical documentation of treatment for diabetes, hypertension, CKD, or cardiovascular disease;

-

(4)

reported control of diabetes or hypertension based on clinical or lab-defined criteria or reported management of CKD or cardiovascular disease.

Study specific definitions of NCD diagnosis are included in Table 1. If studies reported an outcome by multiple indicators, the method with the largest sample size was included in the meta-analysis. Study specific definitions of treatment, screening, or control of NCDs are included in Supplemental Table 3.

Data Extraction

We extracted publication year, country, study design, dates of observation, mean or median age of the cohort, total number of participants, the proportion of female participants, and the number of participants who reported ART use and no ART use as reported for each study. For outcomes of interest, we extracted, if reported, the total number of participants who were screened for, diagnosed with, treated for, or achieved control levels for NCDs of interest by ART status. If reported, we extracted effect estimates—adjusted when available, otherwise crude—and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) estimating the likelihood of disease diagnosis by ART status. If odds ratios were not reported, we calculated the crude odds ratios and 95% CIs of NCD diagnosis comparing PLWH with reported ART use to PLWH reporting no ART use.

Data Analysis

We performed meta-analyses with random effects models to estimate pooled odds ratios and 95% CIs for diabetes and hypertension diagnosis. Pooled estimates were not estimated for CKD due to the heterogeneity of diagnostic measures between studies nor for cardiovascular disease due to the limited number of studies available. We assessed the variation between studies using the I2 statistic [54]. An Egger linear regression test and funnel plot was used to assess for publication bias [55]. Statistical significance of departure from the Egger test null hypothesis of no bias was guided by an alpha level of 0.05.

Sensitivity Analyses

We conducted multiple sensitivity analyses. First, we stratified diabetes and hypertension summary estimates by age group (25–35, 35–45, 45+). Diabetes summary estimates were also stratified by diagnosis method. Additionally, to assess whether the implementation of the WHO Global NCD Action Plan in 2013 had an impact on screening and diagnosis of diabetes and hypertension, we conducted a sensitivity analysis excluding studies with enrollment periods prior to the Action Plan implementation in 2013.

All analyses were performed using STATA v. 15.

Results

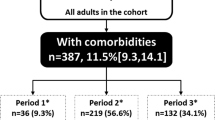

The database search yielded a total of 427 potentially relevant studies, of which 83 were duplicates. After screening 344 titles and abstracts, we excluded 303 studies, leaving 41 that met the criteria for full-text review (Fig. 1). Of the 41 articles reviewed, 26 reported on a relevant outcome by ART status for at least one NCD of interest and were included in the final analysis. Some studies reported on multiple diseases of interest and are thus included in the analysis multiple times, once for each relevant outcome. A total of 16 studies reported on diabetes, 18 on hypertension, 6 on CKD, and one on CVD (Table 1). The total population of PLWH in our study was 13,570 [n = 8318 (61%) with reported ART use and n = 5252 (39%) with no reported ART use]. Sample size ranged from 104 to 3170 participants. Enrollment of cohorts began as early as 2008 and continued until at least 2016. Eight studies did not report enrollment dates. While a number of longitudinal cohort studies were included in the review, the primary outcomes measured longitudinally were not the outcomes of interest for this review. Outcomes of interest for this review, rather, were reported in Table 1 of the study. As such, all data included in this review are a cross-sectional report of outcomes of interest by ART status. Similarly, ART use was not the primary exposure of interest in most studies included in this review, therefore detailed reporting on how ART status was assessed was not available in all studies. Of the studies that did report assessment of ART status, most relied upon self-report and/or medical records.

Diabetes

Of the 16 studies addressing diabetes, only one reported screening prevalence by ART status (Table 1). Results of this study showed a slight increase in the likelihood of diabetes screening for PLWH with reported ART use (49%) compared to PLWH with no reported ART use (42%). The odds of diabetes diagnosis comparing PLWH with reported ART use to PLWH with no reported ART use ranged from 0.32 to 32.93 (Fig. 2). Just over half of the studies showed increased odds of diabetes diagnosis among those with reported ART use. The pooled estimate of diabetes diagnosis showed that among PLWH reported ART use was associated with a 7% increase in the odds of being diagnosed with diabetes compared to no reported ART use (odds ratio (OR) 1.07; 95% CI 0.71, 1.60). The confidence interval for this estimate, however, was imprecise and consistent with up to a 29% decrease and 60% increase in odds of diabetes diagnosis. The I2 statistic for the pooled diabetes diagnosis estimate was 62.1% (p-value = 0.001). Only one study reported on diabetes treatment by ART status and showed a greater likelihood of treatment initiation among PLWH with reported ART use (55%) compared to PLWH with no reported ART use (44%) [21]. No study assessed diabetes control among those who were treated.

Hypertension

Of the 18 studies reporting on hypertension, only one study from South Africa reported on hypertension screening by ART status. Manne-Goehler et al. [21] showed a slightly higher likelihood of hypertension screening for PLWH with reported ART use (72%) compared to PLWH with no reported ART use (69%) (Table 1). Odds of hypertension diagnosis ranged from 0.63 to 10.04 (Fig. 3). All but three studies showed an increase in the odds of hypertension among PLWH with reported ART use compared to those without reported ART use. The pooled summary estimate showed a 110% increase in the odds of hypertension diagnosis among those with reported ART use compared to no reported ART use (OR 2.10; 95% CI 1.42, 3.09). The I2 statistic for the pooled hypertension diagnosis estimate was 87.4% (p-value = 0.000). Five of the 18 studies reported on treatment of hypertension by ART status (Table 1). The study with the largest sample size (N = 566) showed that PLWH with reported ART use were somewhat more likely to report use of anti-hypertensive medication than those with no reported ART use (58% vs. 49%). Results from the other four studies showed little difference between groups or had sample sizes too small to allow for meaningful comparisons. One study reported hypertension control by reported ART status and showed that PLWH with reported ART use were less likely to achieve hypertension control (29.7%) than PLWH with no reported ART use (42.9%) [39].

Chronic Kidney Disease

Six studies reported on CKD diagnosis by ART status. The odds of CKD diagnosis when comparing those with reported ART use to those with no reported ART use ranged from 0.23 to 2.7 (Table 1). The odds of CKD diagnosis was higher in studies using creatine clearance to diagnose CKD, compared to studies basing CKD diagnosis according to estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) (Table 1). No study reported on screening or management of CKD by ART status.

Cardiovascular Disease

One study from Kenya reported on CVD by ART status among PLWH. Achwoka et al. [37] showed a higher prevalence of CVD (hypertension, heart attack, or stroke) among PLWH on ART (93.9%) compared to not on ART (53.9%). However, most identified cases of cardiovascular disease in this study were associated with elevated blood pressure. No studies reported on screening, treatment or control of CVD.

Sensitivity Analyses

Age Impact

The odds of diabetes diagnosis associated with ART use is generally similar across age groups (Supplemental Fig. 1). In the age-stratified analysis of hypertension, the 35–45 age group showed higher odds of hypertension diagnosis among PLWH on ART versus PLWH not on ART [OR 2.32 (95% CI 1.72, 3.14)] compared to the 45 + age group [OR 0.88 (95% CI 0.73, 1.05)] (Supplemental Fig. 2). Only one study had a mean cohort age < 35 and reported an OR of 10.04 (95% CI2.25, 44. 71).

Diagnostic Test Impact

When stratified by diagnosis method, studies using a glucose test had higher odds of diabetes diagnosis (OR 1.51, 95% CI 0.77, 2.96) compared to studies using HbA1c (OR 0.56, 95% CI 0.26, 1.24) or self-report (OR 1.12, 95% CI 0.74, 1.70) (Supplemental Fig. 3).

WHO Global NCD Action Plan in 2013 Impact

Finally, among studies enrolling participants after the implementation of the WHO Global NCD Action Plan in 2013 [56], the pooled estimate of effect for diabetes diagnosis showed an 18% decrease in the odds of diagnosis among PLWH with reported ART use compared to PLWH without reported ART use (OR: 0.82; 95% CI: 0.47, 1.41) (Supplemental Fig. 4). The pooled estimate of effect for hypertension was slightly attenuated when estimated within this restricted study sample (OR: 1.80; 95% CI: 0.96, 3.41) (Supplemental Fig. 5). We note, however, that the effects of the WHO Global NCD Action Plan may not be immediate and therefore not captured within the timeframe of this review.

Publication Bias

Egger’s test to assess for publication bias yielded non-significant results for diabetes (p-value: 0.18) and hypertension (p-value: 0.05). Funnel plots showed minimal evidence of asymmetry suggesting little to no publication bias (Supplemental Fig. 6).

Quality Assessment

The possible range of quality scores was −8 to 16, with a higher score indicating better study quality. The overall quality of studies was high, with scores ranging from 9 to 16, and a median score of 12. The overall quality of studies may be higher than what is reported here as our analysis did not use the primary exposure/outcome measures for all studies.

Discussion

This review summarizes available data on screening, diagnosis, treatment, and control of diabetes, hypertension, CKD, and CVD among PLWH on, vs. not on, ART in sub-Saharan Africa. There has been a push to address the growing burden of NCDs through bolstering of existing healthcare systems for over a decade. In 2011, the Joint United Nations Program on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) recommended an integrated care model leveraging HIV treatment programs to scale up services for NCDs [57]. In 2013, the World Health Organization (WHO) followed suit with a similar recommendation in the Global Action Plan for the Prevention and Control of NCDs for 2013–2020 [58]. Moreover, many countries in SSA, including South Africa, have set up model clinics with integrated services [59]. Given these global and localized efforts, we hypothesized that among PLWH, being on ART–and thus engaged in HIV care–would result in higher rates of screening, diagnosis, treatment, and control of NCDs compared to not being on ART. However, our search over a ten-year timespan and across multiple databases yielded only 26 studies reporting on NCD diagnosis rates among a population of PLWH by ART status, and even fewer reports on screening, treatment, and control. The lack of data inhibits our ability to evaluate the full cascade of NCD care among PLWH and suggests limited uptake of NCD services, even among those who are engaged in ART care.

We found only one study over the last decade, conducted in South Africa, that reported on the full cascade of diabetes care (i.e., diabetes screening, diagnosis, and treatment rates) among a population of HIV-infected adults by ART status. Manne-Goehler et al. [21] showed that among PLWH, those with reported ART use were slightly more likely to be screened, diagnosed, and on treatment for diabetes, providing initial support to the notion that being on treatment for HIV may increase the rate of detection, treatment, and control of diabetes. The outcome of diabetes diagnosis was the only one that was complete for all 16 studies. In our meta-analysis of the 16 studies, we found a null association (OR: 1.07) between reported ART use and diabetes diagnosis. Though the range of study findings was vast (ORs ranged from 0.32 to 33) and most estimates were imprecise, 8 of the 16 studies included in the analysis reported an increased odds of diabetes diagnosis associated with reported ART use among PLWH. Without adequate data on diabetes screening rates among PLWH, we are unable to discern whether the higher odds of diabetes diagnosis seen in some of these studies is a result of being engaged in care, a side effect of ART use leading to higher diabetes prevalence, or a combination of the two. It is reasonable to postulate, however, that more frequent contact with a healthcare system would result in higher rates of detection.

Our results showing increased odds of hypertension diagnosis among those with reported ART use may be due, in part, to ART-induced risk factors contributing to elevated blood pressure levels among PLWH [60, 61]. The ART care structure would seem to provide an ideal framework for treatment and monitoring of blood pressure levels in this higher-risk population [21]. Five studies reporting on hypertension treatment, however, showed very little difference in treatment rates by ART status, and the one study that reported on hypertension control among PLWH showed that those with reported ART use were less likely to achieve control. The lack of data on the full cascade of care inhibits our ability to truly understand the impact of HIV care programs on screening, diagnosis, treatment, and control of hypertension. However, the limited data in this review does suggest that HIV programs have not yet been successfully leveraged to improve hypertension prevention and control.

There is a well-established association between HIV and kidney disease [13, 62, 63]. Chronic inflammation as a result of HIV infection and high levels of toxicity due to long-term ART use can increase a person’s risk for acute kidney injury and CKD [13, 63, 64]. Consequently, we expected to see ample reports of kidney function monitoring efforts among PLWH and on ART. Yet, we found no studies in sub-Saharan African reporting on CKD screening rates, and very few reporting on CKD diagnosis rates, among PLWH and engaged in care. Given the established increase in risk, screening for CKD with creatinine clearance and urine dipsticks should be routinely conducted among PLWH, particularly among those on ART. The lack of data on CKD screening and diagnosis rates among PLWH in sub-Saharan Africa suggests a lack of monitoring in this population, despite a well-established care structure that would support frequent screening and early diagnosis of CKD.

We found only one study reporting on CVD diagnosis among a population of PLWH by ART use. Achwoka et al. [37] showed a higher proportion of CVD among PLWH with reported ART use. However, the majority of cardiovascular events in this study population were related to elevated blood pressure which is more reflective of hypertension risk than CVD. Emerging data from high-income regions suggest that ART use contributes to an increased risk of CVD through alterations of lipid metabolism [14, 65]. The ART care structure provides a framework for critical monitoring of blood pressure and glucose levels, which would allow for early detection of risk factors of cardiovascular disease and mitigate progression and complications.

Our review should be interpreted in the context of its limitations. First, there is the possibility of incomplete retrieval or abstraction of data, or narrow search criteria resulting in missed studies. We did not obtain raw data from study investigators for pooled estimation and relied on simple proportions or estimates of association presented in their data. Diagnosis methods for both NCDs varied across studies, and many studies reporting hypertension diagnosis relied on self-report or medical record review, which could result in non-differential outcome misclassification and likely underestimate the true association. Although heterogeneity between studies was high, we used random effects models to account for variability both within and between studies [66, 67]. However, the results may still represent a weighted average of a biased sample. We saw potential publication bias with regards to hypertension, however, given previous research showing higher rates of hypertension among PLWH, this may be related to a causal association rather than reporting bias. Due to lack of data on NCD care among PLWH, we were unable to evaluate the full cascade of care, including screening, treatment initiation, and control.

Conclusion

The existing HIV care framework in SSA offers a promising setting to screen for NCDs among PLWH. A primary objective of the WHO’s 2013–2020 Global Action Plan was to not only strengthen existing health systems to address the burden of NCDs, but to also support high-quality research for the prevention and control of NCDs [58]. We conclude from this review, however, that evidence supporting that HIV care programs are successfully being leveraged to improve screening, diagnosis, treatment, and control of NCDs is lacking. Continued effort should be made to incorporate NCD services into HIV care programs in SSA. Furthermore, efforts to provide reporting on NCD screening, diagnosis, treatment, and control rates, would aid researchers, clinicians, and governments alike in understanding the true NCD risk among PLWH and the overall impact of care integration models.

References

“About Global NCDs|Division of Global Health Protection|. Global Health| CDC.” https://www.cdc.gov/globalhealth/healthprotection/ncd/global-ncd-overview.html. Accessed 16 Nov 2022.

“Noncommunicable diseases. now ‘top killers globally’ – UN health agency report | | 1UN News.” https://news.un.org/en/story/2022/09/1127211. Accessed 16 Nov 2022.

Miranda JJ, Kinra S, Casas JP, Davey Smith G, Ebrahim S. Non-communicable diseases in low- and middle-income countries: context, determinants and health policy. Trop Med Int Health. 2008;13(10):1225. https://doi.org/10.1111/J.1365-3156.2008.02116.X.

Kassa M, Grace J, Kassa M, Grace J. “The Global Burden and Perspectives on Non-Communicable Diseases (NCDs) and the Prevention, Data Availability and Systems Approach of NCDs in Low-resource Countries,” Public Health in Developing Countries - Challenges and Opportunities, Nov. 2019, https://doi.org/10.5772/INTECHOPEN.89516.

Kavishe B, et al. High prevalence of hypertension and of risk factors for non-communicable diseases (NCDs): a population based cross-sectional survey of NCDS and HIV infection in Northwestern Tanzania and Southern Uganda. BMC Med. 2015;13(1):1–21. https://doi.org/10.1186/S12916-015-0357-9/TABLES/7.

“Mortality and global health estimates”. https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/themes/mortality-and-global-health-estimates. Accessed 12 Sep 2022.

Dalal S, et al. Non-communicable diseases in sub-Saharan Africa: what we know now. Int J Epidemiol. 2011;40(4):885–901. https://doi.org/10.1093/IJE/DYR050.

Van Heerden A, Barnabas RV, Norris SA, Micklesfield LK, Van Rooyen H, Celum C. High prevalence of HIV and non-communicable disease (NCD) risk factors in rural KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. J Int AIDS Soc. 2017;20(2):e25012. https://doi.org/10.1002/JIA2.25012.

Fortin M, Dubois MF, Hudon C, Soubhi H, Almirall J. Multimorbidity and quality of life: a closer look. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2007;5:52. https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7525-5-52.

Booth HP, Prevost AT, Gulliford MC. Impact of body mass index on prevalence of multimorbidity in primary care: cohort study. Fam Pract. 2014;31(1):38. https://doi.org/10.1093/FAMPRA/CMT061.

Joshi K, et al. Declining HIV incidence in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review and meta-analysis of empiric data. J Int AIDS Soc. 2021;24(10):e25818. https://doi.org/10.1002/JIA2.25818.

Vandormael A, Akullian A, Siedner M, de Oliveira T, Bärnighausen T, Tanser F. Declines in HIV incidence among men and women in a South African population-based cohort. Nat Commun. 2019;10(1):1–10. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-13473-y.

Yombi JC, et al. Antiretrovirals and the kidney in current clinical practice: Renal pharmacokinetics, alterations of renal function and renal toxicity. AIDS. 2014;28(5):621–32. https://doi.org/10.1097/QAD.0000000000000103.

Douglas PS, et al. Cardiovascular risk and health among people with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) eligible for primary prevention: insights from the REPRIEVE trial. Clin Infect Dis. 2021;73(11):2009–22. https://doi.org/10.1093/CID/CIAB552.

Sax PE, et al. Weight gain following initiation of antiretroviral therapy: risk factors in randomized comparative clinical trials. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;71(6):1379. https://doi.org/10.1093/CID/CIZ999.

Norwood J, et al. Weight gain in persons with HIV Switched from Efavirenz-based to Integrase Strand Transfer Inhibitor-based Regimens. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2017;76(5):527. https://doi.org/10.1097/QAI.0000000000001525.

Kileel EM, et al. Assessment of obesity and cardiometabolic status by integrase inhibitor use in reprieve: a propensity-weighted analysis of a multinational primary cardiovascular prevention cohort of people with human immunodeficiency virus. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1093/OFID/OFAB537.

Patel SA, et al. Obesity and its relation with diabetes and hypertension: a cross-sectional study across four low- and middle-income country regions. Glob Heart. 2016;11(1):71. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.GHEART.2016.01.003.

Zanella MT, Kohlmann O, Ribeiro AB. Treatment of obesity hypertension and diabetes syndrome. Hypertension. 2001;38(3 Pt 2):705–8. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.HYP.38.3.705.

Ciancio A, Kämpfen F, Kohler HP, Kohler IV. Health screening for emerging non-communicable disease burdens among the global poor: evidence from sub-Saharan Africa. J Health Econ. 2021;75:102388. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JHEALECO.2020.102388.

Manne-Goehler J, et al. The ART advantage: health care utilization for diabetes and hypertension in rural South Africa. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2017;75(5):561–7. https://doi.org/10.1097/QAI.0000000000001445.

Republic of Zambia Ministry of Health. “Zambia Consolidated Guidelines for Treatment and Prevention of HIV Infection.” https://www.moh.gov.zm/wp-content/uploads/filebase/Zambia-Consolidated-Guidelines-for-Treatment-and-Prevention-of-HIV-Infection-2020.pdf. Accessed 23 Jan 2023.

Department of Health of the Republic of South Africa. “2019 ART Clinical Guidelines for the Management of HIV in Adults, Pregnancy, Adolescents, Children, Infants and Neonates.” https://www.health.gov.za/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/2019-art-guideline.pdf. Accessed 23 Jan 2023.

Ministry of Health and Population of Malawi. “Clinical Management of HIV in Children and Adults.” https://differentiatedservicedelivery.org/wp-content/uploads/malawi-clinical-hiv-guidelines-2018-1.pdf. Accessed 23 Jan 2023.

UNAIDS. ”Latest global and regional statistics on the status of the AIDS epidemic”, 2022.

Sayers A. Tips and tricks in performing a systematic review. British J Gen Pract. 2007;57(542):759.

“Covidence - Better systematic review management.” https://www.covidence.org/. Accessed 13 Sep 2022.

“Critical Appraisal Tools | JBI. ” https://jbi.global/critical-appraisal-tools. Accessed 16 Nov 2022.

Dave JA, Lambert EV, Badri M, West S, Maartens G, Levitt NS. Effect of nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor-based antiretroviral therapy on dysglycemia and insulin sensitivity in south African HIV-infected patients. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2011. https://doi.org/10.1097/QAI.0b013e318221863f.

Sani M, Okeahialam B, Muhammad S. Cardiovascular disease risk factors among HIV-infected Nigerians receiving highly active antiretroviral therapy. Nigerian Med J. 2013;54(3):185. https://doi.org/10.4103/0300-1652.114591.

Peck RN, et al. Hypertension, kidney disease, HIV and antiretroviral therapy among Tanzanian adults: a cross-sectional study. BMC Med. 2014. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-014-0125-2.

Shey Nsagha D, et al. Risk factors of cardiovascular diseases in HIV/AIDS patients on HAART. Open AIDS J. 2015. https://doi.org/10.2174/1874613601509010051.

Osegbe D, Soriyan OO, Ogbenna AA, Okpara HC, Azinge EC. Risk factors and assessment for cardiovascular disease among HIV-positive patients attending a nigerian tertiary hospital. Pan African Med J. 2016. https://doi.org/10.11604/pamj.2016.23.206.7041.

Divala OH, et al. The burden of hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and cardiovascular risk factors among adult Malawians in HIV care: consequences for integrated services. BMC Public Health. 2016;16(1):1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-016-3916-x.

Kingery R, et al. Short-term and long-term cardiovascular risk, metabolic syndrome and HIV in Tanzania. Heart. 2016;102(15):1200–5. https://doi.org/10.1136/heartjnl-2015-309026.

Osoti A, et al. Metabolic syndrome among antiretroviral therapy-naive versus experienced HIV-infected patients without preexisting cardiometabolic disorders in western Kenya. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2018;32(6):215–22. https://doi.org/10.1089/apc.2018.0052.

Achwoka D, et al. Noncommunicable disease burden among HIV patients in care: a national retrospective longitudinal analysis of HIV-treatment outcomes in Kenya, 2003–2013. BMC Public Health. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-6716-2.

Manne-Goehler J, et al. Hypertension and diabetes control along the HIV care cascade in rural South Africa. J Int Aids Soc. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1002/jia2.25213/full.

Sarfo FS, et al. Burden of subclinical carotid atherosclerosis and vascular risk factors among people living with HIV in Ghana. J Neurol Sci. 2019;397:103–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jns.2018.12.026.

Jeremiah K, et al. Diabetes prevalence by HbA1c and oral glucose tolerance test among HIV-infected and uninfected Tanzanian adults. PLoS ONE. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0230723.

Sarfo FS, et al. Prevalence and incidence of pre-diabetes and diabetes mellitus among people living with HIV in Ghana: Evidence from the EVERLAST Study. HIV Med. 2021;22(4):231–43. https://doi.org/10.1111/hiv.13007.

Roozen GVT, et al. Electrocardiographic and echocardiographic abnormalities in urban African people living with HIV in South Africa. PLoS ONE. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0244742.

Msoka T, et al. Comparison of predicted cardiovascular risk profiles by different CVD risk-scoring algorithms between HIV-1-infected and uninfected adults: a cross-sectional study in Tanzania. HIV/AIDS—Res Palliative Care. 2021;13:605–15. https://doi.org/10.2147/HIV.S304982.

Ekali G, et al. Fasting blood glucose and insulin sensitivity are unaffected by HAART duration in Cameroonians receiving first-line antiretroviral treatment. Diabetes Metab. 2013;39(1):71–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diabet.2012.08.012.

Botha S, Fourie CMT, van Rooyen JM, Kruger A, Schutte AE. Cardiometabolic changes in treated versus never treated HIV-infected black south Africans: the PURE study. Heart Lung Circ. 2014;23(2):119–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hlc.2013.07.019.

Ogunmola J, Oladosu OY, Olamoyegun AM. Association of hypertension and obesity with HIV and antiretroviral therapy in a rural tertiary health center in Nigeria: a cross-sectional cohort study. Vasc Health Risk Manag. 2014;10:129–37. https://doi.org/10.2147/VHRM.S58449.

Ogunmola OJ, Oladosu YO, Olamoyegun MA. QTC interval prolongation in HIV-negative versus HIV-positive subjects with or without antiretroviral drugs. Ann Afr Med. 2015;14(4):169. https://doi.org/10.4103/1596-3519.152072.

Dimala CA, Atashili J, Mbuagbaw JC, Wilfred A, Monekosso GL. Prevalence of hypertension in HIV/AIDS patients on highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) compared with HAART-naïve patients at the Limbe Regional Hospital, Cameroon. PLoS ONE. 2016. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0148100.

Nduka CU, et al. A plausible causal link between antiretroviral therapy and increased blood pressure in a sub-Saharan African setting: a propensity score-matched analysis. Int J Cardiol. 2016;220:400–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijcard.2016.06.210.

Cailhol J, et al. Prevalence of chronic kidney disease among people living with HIV/AIDS in Burundi: a cross-sectional study. BMC Nephrol. 2011. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2369-12-40.

Sarfo FS, et al. High prevalence of renal dysfunction and association with risk of death amongst HIV-infected Ghanaians. J Infect. 2013;67(1):43–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jinf.2013.03.008.

Che Awah Nforbugwe A, Acha Asongalem E, Bihnwi Nchotu R, Asangbeng Tanue E, Sevidzem Wirsiy F, Nguedia Assob JC. Prevalence of renal dysfunction and associated risk factors among HIV patients on ART at the Bamenda Regional Hospital, Cameroon. Int J STD AIDS. 2020;31(6):526–32. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956462420901985.

Sulaiman MM, et al. Comparative evaluation of prevalence, risk factors, and pathologic features of kidney disease in highly active antiretroviral therapy-naive and highly active antiretroviral therapy-experienced patients at a tertiary health facility in Maiduguri, Northeastern Nigeria. Saudi J Kidney Dis Transpl. 2022;33(1):72–9. https://doi.org/10.4103/1319-2442.367828.

DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986;7(3):177–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2.

Sterne JAC, et al. Recommendations for examining and interpreting funnel plot asymmetry in meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials. BMJ. 2011. https://doi.org/10.1136/BMJ.D4002.

World Health Organization, "Follow-up to the political declaration of the high-level meeting of the General Assembly on the Prevention and Control of Non-communicable Diseases”.

UNAIDS., “Chronic care of HIV and noncommunicable diseases: How to leverage the HIV experience.” https://www.unaids.org/en/resources/documents/2011/20110526_JC2145_Chronic_care_of_HIV. Accessed 23 Jan 2023.

WHO. Global actionplan for the prevention and control of noncommunicable diseases 2013–2020. Russia: WorldHealth Organization; 2013.

Lebina L, et al. Process evaluation of implementation fidelity of the integrated chronic disease management model in two districts, South Africa. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019;19(1):1–14. https://doi.org/10.1186/S12913-019-4785-7/FIGURES/4.

Angkurawaranon C, Nitsch D, Larke N, Rehman AM, Smeeth L, Addo J. Ecological study of HIV infection and hypertension in sub-Saharan Africa: is there a double burden of disease? PLoS ONE. 2016;11(11):e0166375. https://doi.org/10.1371/JOURNAL.PONE.0166375.

Nduka CU, Stranges S, Sarki AM, Kimani PK, Uthman OA. Evidence of increased blood pressure and hypertension risk among people living with HIV on antiretroviral therapy: a systematic review with meta-analysis. J Hum Hypertens. 2016;30(6):355–62. https://doi.org/10.1038/JHH.2015.97.

Naicker S, Rahmanian S, Kopp JB. HIV and chronic Kidney Disease. Clin Nephrol. 2015. https://doi.org/10.5414/CNP83S032.

Post F. Adverse events: ART and the kidney: alterations in renal function and renal toxicity. J Int AIDS Soc. 2014;17(4Suppl 3):19513. https://doi.org/10.7448/IAS.17.4.19513.

Jao J, Wyatt CM. Antiretroviral medications: adverse effects on the kidney. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 2010;17(1):72–82. https://doi.org/10.1053/J.ACKD.2009.07.009.

Ballocca F, et al. HIV infection and primary prevention of cardiovascular disease: lights and shadows in the HAART era. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2016;58(5):565–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.PCAD.2016.02.008.

Huedo-Medina TB, Sánchez-Meca J, Marín-Martínez F, Botella J. Assessing heterogeneity in meta-analysis: Q statistic or I 2 Index? Psychol Methods. 2006;11(2):193–206. https://doi.org/10.1037/1082-989X.11.2.193.

Borenstein M, Hedges LV, Higgins JPT, Rothstein HR. A basic introduction to fixed-effect and random-effects models for meta-analysis. Res Synth Methods. 2010;1(2):97–111. https://doi.org/10.1002/JRSM.12.

Acknowledgements

Emma M Kileel: conception and study design, acquisition of data, data analysis, interpretation of data, drafting of work, final approval. Amy Zheng: acquisition of data, interpretation of data, revision of work, final approval. Jacob Bor, Matthew P Fox, Nigel J Crowther, Jaya A George, Siyabonga Khoza, Sydney Rosen, Willem DF Venter, Frederick Raal, Patricia Hibberd: interpretation of data, revision of work, final approval. Alana T Brennan: conception and study design, data analysis, interpretation of data, drafting of work, revision of work, final approval.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

This work was supported by National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases 1K01DK116929-01A1 (ATB and EMK) and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation INV-031690 (SR). For the remaining authors none were declared.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kileel, E.M., Zheng, A., Bor, J. et al. Does Engagement in HIV Care Affect Screening, Diagnosis, and Control of Noncommunicable Diseases in Sub-Saharan Africa? A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. AIDS Behav 28, 591–608 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-023-04248-0

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-023-04248-0